Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

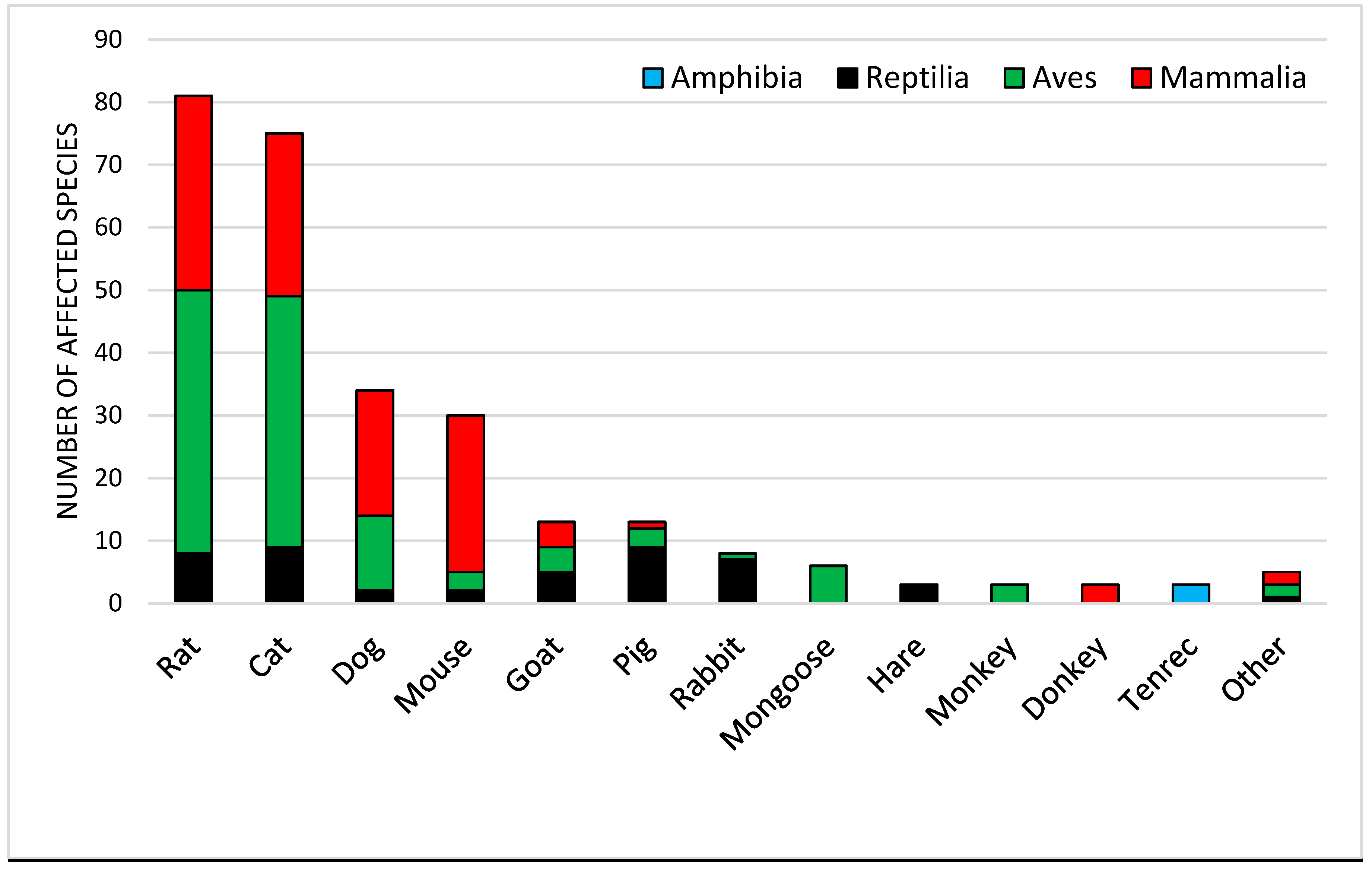

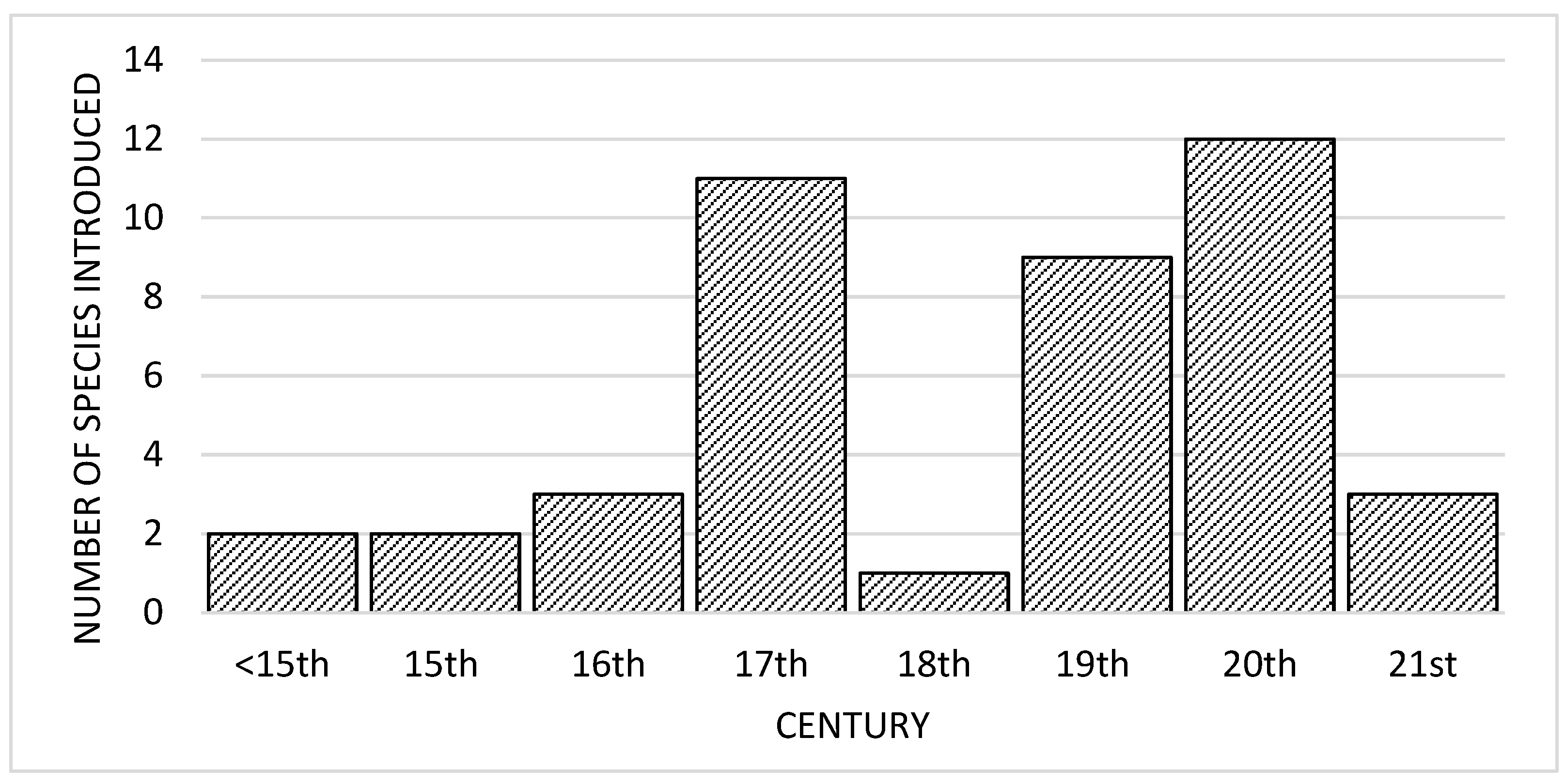

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

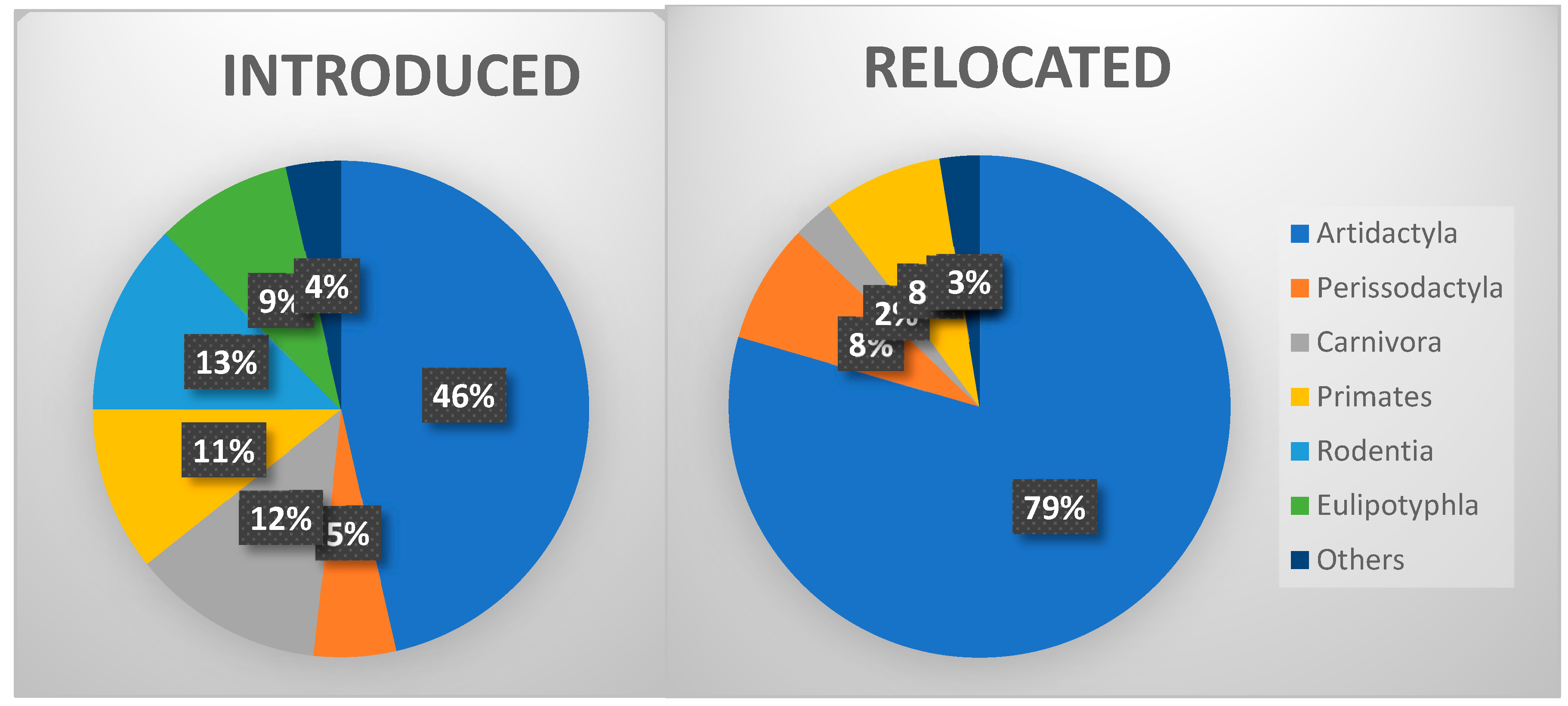

3. The Introduced Species

3.1. Feral/Domestic Species

3.1.1. Feral Cat Felis Catus

3.1.2. Feral Dog Canis familiaris

3.1.3. Feral Donkey Equus asinus

3.1.4. Feral Horse Equus ferus caballus

3.1.5. Wild Boar/Feral Pig Sus scrofa

3.1.6. Feral Goats Capra hircus

3.1.7. Other Feral Mammals

| Scientific species name | Common species name | Family | Original range | Distribution in Africa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenrec edacudaatus | Common Tenrec | Tenrecidae | Madagascar and Comoros | Mauritius <1970; Reunion, <1882; Aldabra Atoll |

| Suncus madagascariensis | Madagascan Pygmy Shrew | Soricidae | Madagascar | Socotra, >1967 |

| Suncus etruscus | Etruscan Shrew | Soricidae | Southern Palearctic | Socotra, <1967 |

| Suncus murinus | Asian House Shrew | Soricidae | SE Asia | E Afr. Coast, Madagascar<1960, well-est.; Comoros, Mauritius, Reunion, est.??; Zanzibar, Pemba <1950SA: Dyer Is. 1912; Aldabra Atoll |

| Eulemur mongoz | Mongoose Lemur | Lemuridae | Madagascar | Comoros, 1665; in 2000: 45 ind./km2, 2008: 10 ind./km2, 2019: 23 ind./km2 (L. J. Ormsby) |

| Cercopithecus aethiops | Green Monkey | Cercopithecidae | Africa | Cape Verde, 1960’s |

| Cercopithecus mona | Mona Monkey | Cercopithecidae | Africa | São Tome e Principe, 1700-1800 |

| Erythrocebus patas | Patas Monkey | Cercopithecidae | Africa | SA: KZN; 2000-2020; crop pest |

| Macaca irus | Long-tailed Macaque | Cercopithecidae | SE Asia | Mauritius Is. 1602; very invasive |

| Macaca fascicularis | Crab-eating Macaque | Cercopithecidae | SE Asia | Mauritius 1602; SA: W Cape |

| Ovis aries musiomn | Muflon | Bovidae | Palearctic | SA |

| Ammotragus lervia | Barbary Sheep | Bovidae | N Africa | SA: Tsolwana Game Reserve (E Cape, early 1980’s), N Cape, F St. Total popul.: c. 1000 ind. in 2015 (S.Brody) |

| Capra hircus | Feral Domestic Goat | Bovidae | Iran | SA: 1650, escape; Nam (Damaral., Namal.); Assumption Is., <1897, 1895: 300-400 exx., 1916: only few, c. 1940 extinct; Prince Edward Is.; Aldabra, 1878, est., <1968 extinct; Mauritius, 1512, 1950: c. 100, <1982 extinct; São Tome e Principe, 16th cen. |

| Hemitragus jemlahicus | Himalayan Tah | Bovidae | Himalayas; S Tibet, Nepal, India | SA 1930: Table Mts. (ornamental; 600 exx. 1974; 100 exx. 1981; 2000: 50-60 exx. eradicated), Cape Peninsula, Golden Gate, Free State. Vulnerable in India; but easy to keep in Zoos, reproduce efficiently |

| Boselaphus tragocamelus | Nilgai | Bovidae | India | SA: E. Cape, Free State |

| Addax nasomaculatus | Addax | Bovidae | N Africa | SA: FE, EC. |

| Bison bison | American Bison | Bovidae | N. America | SA: Ratelfontein near Richmond, Karoo,; 1990’s + |

| Bubalus bubalis | Asian Water Buffalo | Bovidae | SE Asia | Namibia |

| Bos frontalis | Gaur | Bovidae | SE Asia | SA |

| Antilope cervicapra | Indian Blackbuck | Bovidae | India | SA: EC (escapee), 1985? |

| Rusa unicolor | Malayan Sambar | Cervidae | SE Asia | SA 1880 (hunting): EC; Mauritius: 1639 by Dutch |

| Rusa timorensis | Sunda Sambar | Cervidae | Indonesia | SA: EC c.1890; Reunion |

| Cervus dama | Fallow Deer | Cervidae | S Palearctic | SA 1869 (escapee): WC, EC, G, KZN, FS; Madagascar, 1932, extinct before 1974; Angola, Uganda |

| Cervus axis | Axis Deer | Cervidae | SE Asia | SA: EC<1985; FS; crop and forest pest |

| Cervus nippon | Sika Deer | Cervidae | Japan, China, Taiwan | SA: Groot Schuur, 1897, 1937: 20 exx.; EC, FS, Limp.; Madagascar, 1932, now extinct ; forest pest |

| Cervus elaphus | Wapiti | Cervidae | North America | Fernando Poo Isl. 1 (Gulf of Guinea), 1954, established? SA: FS near Clocolan, 1895, 1930’s: 50 exx., Vereeniging (Transvaal), 1975; escapee |

| Cervus elaphus | Red Deer | Cervidae | Eurasia | SA: E Cape, Free State; escapee |

| Cervus timorensis | Rusa | Cervidae | SE Asia: Indonesia | Comoro Is., 1970; Madagascar, 1928, 1950’s widespread, 1990’s extinct; Mauritius, 1639, 1980’s: c. 3000 exx. |

| Cervus unicolor | Samba | Cervidae | SE Asia | SA: Groot Schuur, 1897, 1930’s: c. 50 exx.; 1990’s in a few enclosers in WC |

| Axis porcinus | Hog Deer | Cervidae | India | SA---; escapee |

| Elaphurus davidianus | Père David’s dee | Cervidae | China | SA: EC |

| Sus scrofa | Feral Domestic Pig | Suidae | Europe | SA 1926: W Cape, Zim, Tan. Ug, S Sud., Gabon, SE Chad; São Tome e Principe, 16th cen.; Mauritius 1606, Reunion 1629, Rodrigues c. 1792 |

| Potamochaerus porcus | Warthog | Suidae | Africa | Madagascar, <1962; Mayotte (Comoros), <1982 |

| Tayassus sp. | Peccari | Tayassuidae | South America | Gabon: Wonga-Wongue Pres. Res., <1986 |

| Camelus dromedarius | Dromedary Camel, feral | Camelidae | Asia | Socotra |

| Equus asinus | Feral Donkey | Equidae | C. Asia | SA: 1650, escape; Namib Desert and Ovamboland; Socotra; São Tome e Principe, 16th cen. |

| Equus ferus caballus | Feral Horse | Equidae | C. Asia | SA: 1650, escape; Gabon: W.P. Game Res.<1986; established?; São Tome e Principe, 16th cen. |

| Equus africanus | African Wild Ass, feral | Equidae | Africa | Socotra |

| Canis familiaris | Feral Dog | Canidae | Europe | Cape of Good Hope, <1970; São Tome e Principe, 16th cen.; Madagascar, c.1000 BP |

| Felis catus | Feral Domestic Cat | Felidae | Europe | SA: 1650, escape; Marion 1949 to control rats (1977: 3409 exx.), Mauritius c.1685, Reunion c.1685, Rodrigues c.1745, Seychelles; São Tome e Principe, 16th cen.; Mairon Isl. 1949 (+1991) |

| Civettictis civetta | African Civet | Viverridae | Africa | São Tome e Principe, 19th cen.? |

| Viverricula indica | Small Indian Civet | Viverridae | SE Asia | Socotra, <1608; Zanzibar and Pemba,<1950; Madagascar <1950 |

| Urva auropunctatus | Small Indian Mongoose | Herpestidae | SE Asia | Tanzania: Mafia, Zanzibar, Pemba, <1950; Mauritius<1985 (to control rats in sugar cane plantation) |

| Herpestes edwardsi | Grey Mongoose | Herpestidae | SE Asia | Mauritius, 1899 to control rats |

| Mustela nivalis | Weasel | Mustelidae | Europe | São Tome e Principe, 19th cen.? |

| Oryctolagus cuniculus | European Rabbit | Leporidae | Europe | Robben Is.: 1652 (escapee of domestic ex.); many islands around S. Africa and Madag. 1860, now+; Cape Verde c.1450, abundant, 1990’s+; Mauritius 1810, abundant, totally eradicated in 1987; Seychelles, 1980’s but not established; Aldabra Atoll |

| Lepus nigricollis | Black-naped Hare | Leporidae | India, Pakistan | Mauritius, late 19th cen., 1975: 650-1500 exx., 1982: 2450-2900 exx.; Cousin Is. (Seychelles): 1920’s, 1971: 120-170 exx.; Madagascar; Reunion |

| Mus musculus | House Mouse | Muridae | Middle East | SA: c.800, stowaway; 1500’s: Namibia, Zimbabwe, Kenya, DRC, Nigeria, Benin, Niger, Senegal, Mauritius, Marion, 1800’s; São Tome e Principe, 16th cen. |

| Rattus norvegicus | Brown Rat | Muridae | Far East | SA, 1650, stowaway; Mauritius 1735, Reunion 1735, Rodrigues <1874 |

| Rattus rattus | House Rat | Muridae | SE Asia | SA: c. 800, stowaway; Madagascar, c.300 BC; SA; Mad, Tan, Moz, Et, Benin, Niger, Mauritius <1598, Reunion 1672, Rodrigues <1691, Mayotte, Comoros; São Tome e Principe, 16th cen. |

| Rattus tanezumi | Asian House Rats | Muridae | SE Asia | Widespread in SA and Eswatini c. 2005 |

| Sciurus carolinensis | Grey Squirrel | Sciuridae | USA, Canada | Cape Town area: 1890‘s, 1920’s populated whole Cape Penis; Paarl: 1945; Ceres 1957; Swellendam: 1968 |

| Myocastor coypus | Coypu | Echymyidae | S. America | Hanynki (140 km N of Nairobi), c. 1940; Lake Naivasha: 1965; Lake Ol Bolossat, 1970; Tanz.; Zambia |

| Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris | Capybara | Caviidae | S. America | SA, c. 2020 |

3.2. Ungulates Introduced for Ranching and Hunting

3.2.1. Fallow Deer Cervus dama

3.2.2. Red Deer Cervus elaphus elaphus/Wapiti C. e. canadensis

3.2.3. Sambar Deer Rusa unicolor

3.2.4. Himalayan Tahr Hemitragus jemlahicus

3.2.4. Other Species

3.3. Leporids

3.3.1. European Rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus

3.3.2. Black-Footed Hare Lepus nigricollis

3.4. Rodents

3.4.1. House Mouse Mus musculus

3.4.2. Black Rat (House Rat) Rattus rattus

3.4.3. Brown Rat Rattus norvegicus

3.4.4. Grey Squirrel Sciurus carolinensis

3.4.5. Asian House Rat Rattus tanezumi

3.4.6. Coypu Myocaster coypus

3.4. Carnivores

3.5. Primates

3.6. Insectivores

3.7. General Characteristics of the Mammal Introductions in Sub-Saharan Africa

4. Relocated Mammal Species in Sub-Saharan Africa

5. Impacts of Introduced Mammals on the Vertebrate Biodiversity

| Taxa | Ex | En | O | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | n | n | % | |

| PISCES | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.1 |

| Sooglossidae | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.0 |

| AMPHIBIA | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2.1 |

| REPTILIA | 10 | 9 | 4 | 23 | 16.0 |

| Bolyeriidae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Typhlopidae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Scincidae | 4 | 3 | 4 | 11 | 7.6 |

| Gekkonidae | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2.1 |

| Phyllodactylidae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Testudinidae | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 4.2 |

| AVES | 37 | 31 | 21 | 89 | 61.8 |

| Aepyornithidae | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.1 |

| Phaethontidae | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Sulidae | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Hydrobatidae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Procellariidae | 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 6.3 |

| Phalacrocoracidae | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2.1 |

| Diomedeidae | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 3.5 |

| Laridae | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2.1 |

| Spheniscidae | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Anatidae | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.1 |

| Threskiornithidae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Ardeidae | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Pelecanidae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Rallidae | 7 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 5.6 |

| Columbidae | 8 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 6.3 |

| Psittaculidae | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 3.5 |

| Strigidae | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 3.5 |

| Falconidae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Accipitridae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Hirundinidae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Monarchidae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Muscicapidae | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Campephagidae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Zosteropidae | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2.1 |

| Acrocephalidae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Ploceidae | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2.1 |

| Sturnidae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Nectariniidae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Pycnonotidae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Cisticolidae | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Passeridae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Emberizidae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Fringillidae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.7 |

| MAMMALIA | 18 | 5 | 6 | 29 | 20.1 |

| Nesomyidae | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 3.5 |

| Lemuridae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Indrididae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Archeolemuridae | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.1 |

| Megaladapidae | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.1 |

| Palaeopropithecidae | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3.5 |

| Daubentonidae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Eupleridae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Felidae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Equidae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Hipopotamidae | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.1 |

| Bovidae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Total # species | 65 | 45 | 31 | 144 | 100.0 |

| Places | Reptilia | Aves | Mammalia | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ex | En | O | Ex | En | O | Ex | En | O | Ex | En | O | |

| AFRICA: continent | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Ethiopia/Eritrea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Southern Africa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| South Africa | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| AFRICA: islands | 9 | 10 | 2 | 42 | 29 | 24 | 16 | 4 | 5 | 68 | 43 | 32 |

| Cape Verde | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Gulf of Guinea islands | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Marion Isl. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 |

| Madagascar | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 4 | 5 | 20 | 5 | 5 |

| Mauritius | 3 | 9 | 0 | 11 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 16 | 2 |

| Reunion | 2 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 1 | 2 |

| Rodrigues | 2 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| Other Mascarenes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Comoros | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Seychelles | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Socotra | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Total | 10 | 11 | 2 | 42 | 30 | 24 | 19 | 5 | 6 | 71 | 46 | 33 |

6. Impact of Alien Mammals in Islands

6.1. Cape Verde

6.2. São Tomé e Principe and Other Islands in the Gulf of Guinea

6.3. Madagascar

6.4. Mascarenes

6.5. Comoros

6.6. Seychelles

6.7. Socotra

6.8. Prince Edward Islands

References

- Alho, M.; Granadeiro, J.P.; Rando, J.C.; Geraldes, P.; Catry, P. Characterization of an extinct seabird colony on the island of Santa Luzia (Cabo Verde) and its potential for future recolonizations. J. Orn. 2022, 163, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANMH (American Museum of Natural History). Amphibian Species of the World 6.2, an Online Reference. https://amphibiansoftheworld.amnh.org/. Accessed on 03.03.2025.

- Angel, A.; Wanless, R.M.; Cooper, J. Review of impacts of the introduced house mouse on islands in the Southern Ocean: are mice equivalent to rats? Biol. Invas. 2009, 11, 1743–1754. [Google Scholar]

- Alpers, D.L.; van Vuuren, B.J.; Arctander, P.; Robinson, T.J. Population genetics of the roan antelope (Hippotragus equinus) with suggestions for conservation. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, I.A.E. 1985. The spread of commensal species of Rattus to oceanic islands and their effect on island avifaunas. In: Moors PJ (ed) Conservation of island birds. ICBP Technical Publication no.3, Cambridge, 1985.

- Ballari, S.A.; Anderson, C.B.; Valenzuela, A.E. Understanding trends in biological invasions by introduced mammals in southern South America: A review of research and management. Mam. Rev., 2016, 46, 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos, A.D.; Nair, D.; Taylor, P.J.; et al. Genetic monitoring detects an overlooked cryptic species and reveals the diversity and distribution of three invasive Rattus congeners in South Africa. BMCGenet 2011, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, M.N.; Bloomer, J.P.; Van Aarde, R.J.; Erasmus, B.H.; Van Rensburg, P.J.J.; Skinner, J.D.; et al. A review of the successful eradication of feral cats from sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Southern Indian Ocean. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 2002, 32, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bigalke, R.C., & Pepler, D. Mammals introduced to the mediterranean region of South Africa. Biogeography of Mediterranean Invasions, 1991, 285-292.

- BirdLife International. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016, 1643. [CrossRef]

- BirdLife International (2018). IUCN Red List of Threatened,. [CrossRef]

- Blench, R. The history and spread of donkeys in Africa. Donkeys, people and development. A resource book of the Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA). ACP-EU Technical Center for Agriculture and Rural Cooperation, Wageningen, 2004.

- Bloomer, J.P.; Bester, M.N. Control of feral cats on sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Indian Ocean. Biol. Conserv. 1992, 60, 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Bocage, J.V.B. Contribution a la faune des quatre isles du Golfe du Guinee. 2. lie de Prince. J. Acad. Sci. Lisboa 1904, 7, 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bocage, J.V.B. Contribution a la faune des quatre isles du Golfe du Guinee. 4. Be de Sao Tome. J. Acad. Sci. Lisboa, 1904, 7, 65–96.

- Bonnington, C.; Gaston, K.J.; Evans, K.L. Fearing the feline: domestic cats reduce avian fecundity through trait-mediated indirect effects that increase nest predation by other species. J. appl. Ecol. 2013, 50, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomer, M. Translocation of 7 Mammal Species to Rubondo Island National Park in Tanzania. Frankfurt Zoological Society Tanzania Wildlife Conservation Project ; Arusha (Tan.), 1988.

- Brooke, R.K.; Lloyd, P.H.; de Villiers, A.L. Alien and translocated terrestrial vertebrates in South Africa. In: Macdonald IAW, Kruger FJ, Ferrar AA (eds) The ecology and management of biological invasions in Southern Africa. Oxford University Press, Cape Town, pp 63–74, 1986.

- Brown, C.J.; Macdonald, I.A.W.; Brown, S.E. (eds) Invasive Alien Organisms in South West Africa/Narnibia. S. A. Natn. Sci. Progr. Rep. 1985, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, D.J.; North, S.G.; Dulloo, M.E.; Thorsen, M. The impact of rabbit and goat eradication on the ecology of Round Island, Mauritius. In Veitch, C.R.; Clout, M.N. (eds.), Turning the Tide: The Eradication of Invasive Species. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, Cambridge, UK, pp. 53–63, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, K.; Donlan, C.J. Feral goat eradications on islands. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 1362–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Castley, J.G.; Boshoff, A.F.; Kerley, G.I.H. Compromising South Africa's natural biodiversity-inappropriate herbivore introductions. S. Afr. J. Sci., 2001, 97, 344–348. [Google Scholar]

- Cheke, A.S. Extinct birds of the Mascarenes and Seychelles–a review of the causes of extinction in the light of an important new publication on extinct birds. Phelsuma, 2013, 21, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cheke, A.S.; Hume, J.P. Lost land of the dodo: an ecological history of Mauritius, Réunion & Rodrigues. A&C Black, 2008.

- Clements, J.F.; Schulenberg, T.S.; Iliff, M.J.; Roberson, D.; Fredericks, T.A.; et al. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world, 2018. www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/ Accessed on 01.03.2015.

- Cole, N. 2021. Madatyphlops cariei. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.K.; Brooke, R.K. Past and present distribution of the feral European rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus, on southern African offshore islands. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 1982, 12, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Courchamp, F.; Chapuis, J.L.; Pascal, M. 2003. Mammal invaders on islands: impact, control and control impact. Biol. Rev. 2003, 78, 347–383. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, R.J.M.; Dyer, B.M. Wildlife of Robben Island. Bright continent guide 1. Avian Demography Unit, Cape Town, 2000.

- Crawford, A.B.; Serventy, D.L. The birds of Marion Island, South Indian Ocean. Emu-Austral Ornithology 1952, 52, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, B.E. A refined chronology of prehistoric Madagascar and the demise of the megafauna. Quarter. Sci. Rev. 2010, 29, 2591–2603. [Google Scholar]

- Cuzin, F.; Randi, E. Sus scrofa Wild Boar. In: Kingdon, J.; Hoffmann, M. (eds.). Mammals of Africa. Vol. 6, p. 28-29.

- Damme, K.V.; Banfield, L. Past and present human impacts on the biodiversity of Socotra Island (Yemen): implications for future conservation. Zool. Middle East 2011, 54, 31–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.J.; Jordaan, M.; Karsten, M.; et al. Experience and lessons from alien and invasive animal control projects in South Africa. In: van Wilgen, B.W.; Measey, J.; Richardson, D.M. et al (eds.) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 625–660, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Deacon, J. Human settlement in South Africa and archaeological evidence for alien plants and animals. In: Macdonald, I.A.W.; Kruger, F.J.; Ferrar, A.A. (eds.) The ecology and management of biological invasions in southern Africa. Oxford University Press, Cape Town, pp 3–19, 1986.

- De Villiers, M.S.; Mecenero, S.; Sherley, R.B.; Heinze, E.; Kieser, J.; Leshoro, T.M. , et al. Introduced European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) and domestic cats (Felis catus) on Robben Island: Population trends and management recommendations. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res., 2010, 40, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, K.; Lopes, E.P.; Vasconcelos, R. . Cabo Verde giant gecko: how many units for conservation? Amphibia-Reptilia 2021, 42, 503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Dilley, B.J.; Schoombie, S.; Schoombie, J.; Ryan, P.G. ‘Scalping’of albatross fledglings by introduced mice spreads rapidly at Marion Island. Antarctic Sci. 2016, 28, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dobigny, G.; Poirier, P.; Hima, K.; Cabaret, O.; Gauthier, P.; Tatard, C.; Costa, J.M.; Bretagne, S. Molecular survey of rodent-borne Trypanosoma in Niger with special emphasis on T. lewisi imported by invasive black rats. Acta Tropica 2011, 117, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dobigny, G.; Dalecky, A. Native and Invasive Small Mammals in Urban Habitats along the Commercial Axis Connecting Benin and Niger, West Africa. Diversity 2019, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.S.; Dickman, C.R.; Glen, A.S.; Newsome, T.M.; Nimmo, D.G.; Ritchie, E.G.; et al. The global impacts of domestic dogs on threatened vertebrates. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 210, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J. Introduced mammals in São Tomé and Príncipe: possible threats to biodiversity. Biodiv. Conserv. 1994, 3, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faith, J.T. 2014. Late Pleistocene and Holocene mammal extinctions on continental Africa. Earth-Science Rev. 2014, 128, 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Feiler, A. Uber die Saiigetiere der Insel São Tome. Zool. Abh. Mus. Tierk. Dresden 1984, 40, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Feiler, A. Die Saugetiere der Inseln im Golf von Guinea und ihre Beziehungen zur Saugetierfauna der westafrikanischen Festlandes. Zool. Abh. Mus. Tierk. Dresden 1988, 44, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Feiler, A.; Haft, J.; Widmann, P. Beobachtungen und Untersuchungen an Saugetieren der Insel São Tome (Golf von Guinea) (Mammalia). Faun. Abh. Mus. Tierkd. Dresden 1993, 19, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, E.; Gascoigne, A. Conservation of pteridophytes in São Tomé e Príncipe (Gulf of Guinea). Biodiv. Conserv. 2001, 10, 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, B.M.; Veitch, C.R. The cats of Herekopare Island, New Zealand; their history, ecology and affects on birdlife. New Zeal. J. Zool., 1985, 12, 319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Frade, F. Aves e mammiferos das Ilhas de Sao Tome e do Principe - notas de sistematica e de proteccao a fauna. Conferencia International dos Africanistes Occidendais, Lisboa 1958, 4, 137–50. [Google Scholar]

- Freeland, W.J. Large herbivorous mammals: exotic species in northern Australia. J. Biogeogr.

- Genovesi, P.; Bacher, S.; Kobelt, M.; Pascal, M.; Scalera, R. Alien mammals of Europe. Handbook of alien species in Europe.

- Ghestemme, T.; Salamolard, M. L'échenilleur de La Réunion, Coracina newtoni, espèce endémique en danger. Ostrich 2007, 78, 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Gippoliti, S.; Robovský, J.; Angelici, F.M. Taxonomy and Translocations of African Mammals: A Plea for a Cautionary Approach. Conservation 2021, 1, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, L.R.; Rasoazanabary, E. Demise of the Bet Hedgers: A Case Study of Human Impacts on Past and Present Lemurs of Madagascar. In Sodikoff; G.M (eds.). The Anthropology of Extinction: Essays on Culture and Species Death. Indiana University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, S.M. Rattus on Madagascar and the Dilemma of Protecting the Endemic Rodent Fauna. Conserv. Biol. 1995, 9, 450–453. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, S.M. The New Natural History of Madagascar. Princeton University Press, 2022.

- Greyling, T. Factors affecting possible management strategies for the Namib feral horses (. Ph.D. Thesis, ). North-West University, Pochefstroom, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Greve, M.; von der Meden, C.E.O.; Janion-Scheepers, C. Biological invasions in South Africa’s offshore sub-Antarctic territories. In: van Wilgen, B.W.; Measey, J.; Richardson, D.M. et al (eds.) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp. 205–226, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Goldbeck, G. ; Greyling; Swilling, R. Wild horses in the Namib Desert: An Equine Biography. Windhoek, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Burney, D.A. Subfossil Lemurs of Madagascar. In: Werdelin, L.; Sanders, W.J (eds.). Cenozoic Mammals of Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L. Subfossil Lemurs. In: Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar, 1247. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Burney, D.A. Subfossil lemurs of Madagascar. Cenozoic Mammals of Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, S.M. 1995. Rattus on Madagascar and the Dilemma of Protecting the Endemic Rodent Fauna. Conserv. Biol. 1995, 9, 450–453. [Google Scholar]

- Graaff, G. The Rodents of Southern Africa: Notes on Their Identification, Distribution, Ecology, and Taxonomy. Butterworths, Durban, 1981.

- Groom, M.J.; Meffe, G.K.; Carroll, C.R. Principals of Conservation Biology. 3rd ed. Sunderland (MA, U.S.A.), Sinauer Associates, 2006.

- Hagern, B.L.; Kumschick, S. The relevance of using various scoring schemes revealed by an impact assessment of feral mammals. NeoBiota 2018, 38, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansford, J.P.; Turvey, S.T. (2018-09-26). Unexpected diversity within the extinct elephant birds (Aves: Aepyornithidae) and a new identity for the world's largest bird. Roy. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 181295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happold, D.C.D. Sciurus carolinensis Grey Squirrel. In: Happold, D.C.D. (ed.) Mammals of Africa. Vol. 3, p. 92-93, 2013.

- Happold, D.C.D. Rattus norvegicus Brown Rat. In: Happold, D.C.D. (ed.) Mammals of Africa. Vol. 3, p. 540-541, 2013.

- Happold, D.C.D. Rattus rattus Black Rat. In: Happold, D.C.D. (ed.) Mammals of Africa. Vol. 3, p. 541-543, 2013.

- Happold, D.C.D. Myocaster coypus Coypu. In: Happold, D.C.D. (ed.) Mammals of Africa. Vol. 3, p. 691-692, 2013.

- Happold, D.C.D. Oryctolagus cuniculus European Rabbit. In: Happold, D.C.D. (ed.) Mammals of Africa. Vol. 3, p. 708-710.

- Havemann, C.P.; Retief, T.A.; Tosh, C.A.; de Bruyn, P.J.N. Roan antelope Hippotragus equinus in Africa: a review of abundance, threats and ecology. Mammal Rev. 2016, 46, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, H.E.; Dunn, A.M.S. Mongooses, Their Natural History and Behaviour, Oliver & Boyd, 42s. Published online by Cambridge University Press, 1967.

- Hixon, S.W.; Douglass, K.G.; Godfrey, L.R.; Eccles, L.; Crowley, B.E.; Rakotozafy, L.M.A.; Clark, G.; Haberle, S.; Anderson, A.; Wright, H.T.; Kennett, D.J. Ecological Consequences of a Millennium of Introduced Dogs on Madagascar. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 689559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockey, P.A.R.; Dean, W.R.J.; Ryan, P.G. (Eds.) . Roberts– Birds of Southern Africa, 7th edn. The Trustees of the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town, 2005.

- Hoffmann, K.L.; Wood, A.K.; Mccarthy, P.H.; Griffiths, K.A.; Evans, D.L.; Gill, R.W. Sonographic observations of the peripheral vasculature of the equine thoracic limb. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 1999, 28, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hughes, J.; Macdonald, D.W. A review of the interactions between free-roaming domestic dogs and wildlife. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 157, 341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Hugulay, M.; Gascoigne, A.; De Deus, D.; De Lima, R.F. Notes on the breeding ecology and conservation of the Critically Endangered Dwarf Olive Ibis. Bul. ABC. 2014, 21, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, J.P. Extinct Birds. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017.

- Huntley, B.J. Marion Island: Birds, Cats, Mice and Men. In Strategic Opportunism: What Works in Africa: Twelve Fundamentals for Conservation Success (p. 21-37). Cham, Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023.

- IUNC. 100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species. Global Invasive Species Database, /: https, 2025.

- Jassat, W.; Naicker, N.; Naidoo, S.; Mathee, A. Rodent control in urban communities in Johannesburg, South Africa: From research to action. Int.J. Envir.Health Res. 2013, 23, 474–483. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.G.W.; Ryan, P.G. Evidence of mouse attacks on albatross chicks on sub-Antarctic Marion Island. Antarctic Sci., 2010, 22, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, H.P.; Tershy, B.R.; Zavaleta, E.S.; Croll, D.A.; Keitt, B.S. , Finkelstein, M. E.; Howald, G.R. Severity of the effects of invasive rats on seabirds: A global review. Conservation Biology 2008, 22, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julius, R.S.; Schwan, E.V.; Chimimba, C.T. Helminth composition and prevalence of indigenous and invasive synanthropic murid rodents in urban areas of Gauteng Province, South Africa. J. Helminthol. 2018, 92, 445–454. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D.B. Review of negative effects of introduced rodents on small mammals on islands. Biol Invas. 2009, 11, 1611–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefena, E.; Dessie, T. The Kundido feral horses: Fugitives of the Abyssinian domestic horses. Vol. 25. Ethiopian Society of Animal Production (ESAP), 2011.

- Kehlmaier, C.; Graciá, E.; Ali, J.R.; Campbell, P.D.; Chapman, S.D.; Deepak, V.; Ihlow, F.; Jalil, N.-E.; Pierre-Huyet, L.; Samonds, K.E.; Vences, M.; Fritz, U. Ancient DNA elucidates the lost world of western Indian Ocean giant tortoises and reveals a new extinct species from Madagascar. Science Advances 2023, 9, eabq2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerley, G.; Boshoff, A. The introduction of alien mammals into the broader Western and Northern Cape Provinces of South Africa. Centre for African Conservation Ecology Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, 2015.

- Kimura, B.; Marshall, F.B.; Chen, S.; Rosenbom, S.; Moehlman, P.D.; Tuross, N.; et al. Ancient DNA from Nubian and Somali wild ass provides insights into donkey ancestry and domestication. Proc. Roy. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2011, 278, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, D.A.; Racey, P.A. Effects of the introduced black-naped hare Lepus nigricollis nigricollis on the vegetation of Cousin Island, Seychelles and possible implications for avifauna. Biol. Conser. 1992, 61, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikoti, I.A.; Mushi, R.F. Rubondo Island National Park: Overlooked World’s Largest Tropical Lake Island Protected Area in Tanzania. E. Afr. J. Envir. Nat. Res. 2025, 8, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B. Conservation geographies in Sub-Saharan Africa: The politics of national parks, community conservation and peace parks. Geography Compass 2010, 4, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komdeur, J. 1996. Breeding of the Seychelles Magpie Robin Copsychus sechellarum and implications for its conservation. Ibis 1996, 138, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. 2025. In perep.

- Kruger J, Parrini F, Koen J et al. A conservation assessment of Hippotragus equinus. In: Child, M.F.; Roxburgh, L.; Do Linh San, E.; Raimondo, D.; Davies-Mostert, H.T. (eds.). The Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho. South African National Biodiversity Institute and Endangered Wildlife Trust, Pretoria, 2016.

- Kurdila, J. The introduction of exotic species into the United States: there goes the neighborhood. BC Envtl. Aff. L. Rev., 1988, 16, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Le Corre, M.; Danckwerts, D.K.; Ringler, D.; Bastien, M.; Orlowski, S.; Morey-Rubio, C.; Pinaud, D.; Micol, T. Seabird recovery and vegetation dynamics after Norway Rat eradication at Tromelin Island, western Indian Ocean. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 185, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, J.J.; Foxcroft, L.C.; Herbst, M.; MacFadyen, S. Genetic analysis shows low levels of hybridization between African wildcats (Felis silvestris lybica) and domestic cats (F. s. catus)in South Africa. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, Naturalized Animals: the Ecology of Successfully Introduced Species. Poyser Natural History, London, 1994.

- Lewis, J.S.; Matthew, L.; Farnsworth, C.L.; Burdett, D.M.; Theobald, M.G.; Miller, R.S. Biotic and abiotic factors predicting the global distribution and population density of an invasive large mammal. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 44152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, J. Occurrence of the introduced black rat (Rattus rattus) and its potential effects on endemic rodents in southeastern Madagascar. Unpubl. academic thesis. Univ. Helsinki. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Llobet, T.; Velikov, I.; Sogorb, L.; Peacock, F.; Jutglar, F.; Mascarell, A.; Blanca, M.; Rodríguez-Osorio, J. Allthe. Mammals of the World. Lynx Nature Books, Barcelona, 2023.

- Long, J.L. Introduced mammals of the world: their history, distribution and influence. CSIRO publishing, 2003.

- Lucek, K.; Lemoine, M. First record of freshwater fish on the Cape Verdean archipelago s. African Zoology, 47.

- Macpherson, C.N.L.; Karstad, L.; Stevenson, P.; Arundel, J.H. Hydatid disease in the Turkana District of Kenya. 3. The significance of wild animals in the transmission of Echinococcus granulosus, with particular reference to Turkana and Masailand in Kenya. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1983, 77, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, J.A.; Barone, R.; Hernández-Acosta, C.N.; López-Jurado, L.F. La muerte anunciada de dos gigantes macaronésicos: el gran escinco caboverdiano, Chioninia coctei (Duméril & Bibron, 1839) y el lagarto de Salmor, Gallotia simonyi (Steindachner, 1889). Bol. Asoc. Herpetol. Esp. 2020, 31, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Matthee, C.A.; Robinson, T.J. Mitochondrial DNA population structure of roan and sable antelope: implications for the translocation and conservation of the species. Molecular Ecology 1999, 8, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Measey, J.; Hui, C.; Somers, M.J. Terrestrial vertebrate invasions in South Africa. Biological Invasions in South Africa, v: In, 2020; 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, L.; Kshirsagar, A.R.; Rafaliarison, R.R.; Rajaonarivelo, T.; Farris, Z.J.; Randriana, Z.; Valenta, K. Wildlife predation by dogs in Madagascar. Biotropica 2022, 54, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P. Settling Madagascar: When Did People First Colonize the World's Largest Island? J. Isl. Coast. Archaeol. 2020, 15, 576–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militão, T.; Dinis, H.A.; Zango, L.; Calabuig, P.; Stefan, L.M.; González-Solís, J. Population size, breeding biology and on-land threats of Cape Verde petrel (Pterodroma feae) in Fogo Island, Cape Verde. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljutin, A.; Lehtonen, J.T. Probability of competition between introduced and native rodents in Madagascar: An estimation based on morphological traits Est. J. Ecol. 2008, 57, 2–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midtgaard, R. RepFocus – A Survey of the Reptiles of the World, 2025. www.repfocus.dk. Accessed on 03.03. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Louis, E.E.; Richardson, M.; Schwitzer, C.; et al. Lemurs of Madagascar. Conservation International, 3rd ed., 2010.

- Monadjem, A.; Taylor, P.J.; Denys, C.; Cotterill, F.P.D. Rodents of sub-Saharan Africa: a biogeographic and taxonomic synthesis. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Moolman, H.J.; Cowling, R.M. The impact of elephant and goat grazing on the endemic flora of South African succulent thicket. Biol Conserv. 1994, 68, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, H.; Bourne, A. Minimum population size and potential impact of feral and semi-feral donkeys and horses in an arid rangeland. Afr. Zool., 2018, 53, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaffar, S.B.; Benjamin, D.; Gubiani, R.E. The impact of fox and feral cat predation on the population viability of the threatened, endemic Socotra cormorant on Siniya Island, United Arab Emirates. Marine Orn. 2013, 41, 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Mwenya, E.; Keib, G. History and utilisation of donkeys in Namibia. Donkeys, People and Development: a Resource Book for Eastern and Southern Africa, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nameer, P.O.; Smith, A.T. Lepus nigricollis. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, D.C.; Ryan, P.G.; Crawford, R.J.; Cooper, J.; Huyser, O.A. Population trends of albatrosses and petrels at sub-Antarctic Marion Island. Polar Biology 2002, 25, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, R.M. Walker’s Mammals of the World. T. 1. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999, s. 1024–1025.

- Owadally, A.W. Some forest pests [animal and plant] and diseases [fungal and bacterial] in Mauritius. Revue Agricole et Sucriere de l'Ile Maurice (Mauritius).

- Peet, N.B.; Atkinson, P.W. The biodiversity and conservation of the birds of São Tomé and Príncipe. Biodiv. Conserv., 1994, 3, 851–867. [Google Scholar]

- Picker, M.D.; Griffiths, C.L. Alien and invasive animals: A South African perspective. Penguin Random House South Africa, Cape Town, 2011.

- Picker, M.D.; Griffiths, C.L. Alien animals in South Africa-composition, introduction history, origins and distribution patterns. Bothalia-African Biodiv. Conserv, 47. [CrossRef]

- Potgieter. L.; Douwes, E., Ed.; Gaertner, M. et al. Biological invasions in South Africa’s urban ecosystems: patterns, processes, impacts and management. In: van Wilgen, B.W.; Measey, J.; Richardson, D.M. et al (eds.) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 273–310, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodin, A.G.J.; Pritchard, P.C.H.; van Dijk, P.P.; Saumure, R.A.; Buhlmann, K.A.; Iverson, J.B.; Mittermeier, R.A. (Eds.) . Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation Project of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. Chelonian Research Monographs, 5, 2015.

- Rodríguez, P.J. Exotic species introductions into South America: an underestimated threat? Biodiv. Conserv. 2001, 10, 1983–1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rocamora, G.; Henriette, E. Invasive Alien Species in Seychelles: why and how to eliminate them. Identification and management of priority species. Collection Inventaires et Biodiversité. Biotope Éditions, Mèze; Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, 2015. 384.

- Russell, J.C.; Cole, N.C.; Zuël, N. Gérard Rocamora Introduced mammals on Western Indian Ocean islands. Global Ecol. Conserv. 2016, 6, 132–144. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.C.; Towns, D.R.; Clout, M.N. Review of rat invasion biology: implications for island biosecurity. Science for Conservation 286, Department of Conservation, Wellington, 2018.

- Ryan, P. Alein and islands. Quest 2015, 11, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, E.S. How Cabo Verde is becoming a safe haven for seabirds. BirdLife Intern. https://www.birdlife.org/news/2020/11/05/how-cabo-verde-is-becoming-a-safe-haven-for-seabirds/ Accessed: 17.02.2025.

- Sanchez, M. Phelsuma borbonica. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2021: E. T17429273A17430906, 2021.

- Sanchez, M.; Caceres, S. Plan national d’actions en faveur des Geckos verts de La Réunion Phelsuma borbonica et Phelsuma inexpectata. Nature Océan Indien/Office Français de la Biodiversité, pour la Direction de l’Environnement, de l’Aménagement et du Logement de La Réunion,.

- Saraf, S. Preserving the perishing endangered natural biodiversity of Socotra Island. Open, J. Ecol. 2021, 11, 148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, M. Leiolopisma ceciliae. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semedo, G.; Paiva, V.H.; Militão, T.; Rodrigues, I.; Dinis, H.A.; Pereira, J.; Matos, D.; Ceia, F.R.; Almeida, N.M.; Geraldes, P.; Saldanha, S.; Barbosa, N.; Hernández-Montero, M.; Fernandes, C.; González-Sólis, J.; Ramos, J.A. Distribution, abundance, and on-land threats to Cabo Verde seabirds. Bird Conservation International 2020. doi.org/10.1017/S0959270920000428.

- Shackelton, A. Diversity and Taxonomy of Malagasy Pygmy Hippopotamuses. MS thesis. Northern Illinois University, 2021.

- Shivambu, N.; Shivambu, T.C.; Downs, C.T. Assessing the potential impacts of non-native small mammals in the South African pet trade. NeoBiota 2020, 60, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivambu, N.; Shivambu, T.C.; Downs, C.T. Non-native small mammal species in the South African pet trade. Mgmt. Biol. Inv. 2021, 12, 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skead, C.J.; Boshoff, A.; Kerley, G.I.H.; Lloyd, P. Introduced (non-indigenous) species: a growing threat to biodiversity. In: Skead CJ, Boshoff A, GIH K, Lloyd P (eds) Historical incidence of the larger land mammals in the broader Northern and Western Cape. Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Centre for African Conservation Ecology, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, 2011.

- Smithers, R.H.N. The mammals of the southern African subregion. University of Pretoria, Pretoria, 1983.

- Spear, D.; Chown, S.L. Taxonomic homogenization in ungulates: patterns and mechanisms at local and global scales. J. Biog. 2008, 35, 1962–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, D.; Chown, S.L. The extent and impacts of ungulate translocations: South Africa in a global context. Biol Conserv. [CrossRef]

- Spear, D.; Chown, S.L. Non-indigenous ungulates as a threat to biodiversity. J. Zool, 1: 279. [CrossRef]

- Sow, A.; Duplantier, J.M. Sharing space between native and invasive small mammals: Study of commensal communities in Senegal. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, D.W. Prehistoric extinctions of Pacific island birds: biodiversity meets zooarchaeology. Science, 1995, 267, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sufiyan, A. Kundudo feral horse: Trends, status and threats and implication for conservation. Global J. Zool., 2022, 7, 009–013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, R.W.; Tattersall, I. A Preliminary Study of the Crab-eating Macaque Macaca fascicularis in Mauritius, Mauritius Inst. Bul. 1980, 9, 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, R.W.; Tattersall, I. Distribution, Abundance, and Putative Ecological Strategy of Macaca fascicularis on the Island of Mauritius, Southwestern Indian Ocean, Folia Primatol. 1986, 46, 28–43. 46.

- Courchamp, F.; Chapuis, J.-L.; Pascal, M. Mammal Invaders on Islands: Impact, Control, and Control Impact, Biol. Rev. 2002, 78, 347–383. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P.J. , Arntzen, L., Hayter, M., Iles, M., Frean, J., & Belmain, S. Understanding and managing sanitary risks due to rodent zoonoses in an African city: beyond the Boston Model. Integrative Zool. 2008, 3, 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tennent, J.; Downs, C.T. Abundance and home ranges of feral cats in an urban conservancy where there is supplemental feeding: a case study from South Africa. Afr. Zool., 2008, 43, 218–229. [Google Scholar]

- Toomes, A.; García-Díaz, P.; Wittmann, T.A.; Virtue, J.; Cassey, P. New aliens in Australia: 18 years of vertebrate interceptions. Wildlife Res., 2019, 47, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towns, D.R.; Atkinson, I.A.E.; Daugherty, C.H. Have the harmful effects of introduced rats on islands been exaggerated? Biol. Invas. 2006, 8, 863–891. [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, A.M.; Chown, S.L. Antagonistic effects of biological invasion and temperature change on body size of island ectotherms. Divers.Distrib. 2014, 20, 202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.K.; Olson, K.A.; Reading, R.P.; Amgalanbaatar, S.; Berger, J. Is wildlife going to the dogs? Impacts of feral and free-roaming dogs on wildlife populations. BioScience 2011, 61, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- van Helden, L.; van Helden, P.D.; Meiring, C. Pathogens of vertebrate animals as invasive species: Insights from South Africa. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM et al (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 247–272, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, A.M.; Dalton, D.L.; Kotzé, A.; Grobler, J.P.; Mokgokong, P.S.; Kropff, A.S.; Jansen van Vuuren, B. Assessing introgressive hybridization in roan antelope (Hippotragus equinus): Lessons from South Africa. Plos one 2019, 14, e0213961. [Google Scholar]

- van Wilgen, B.W.; Measey, J.; Richardson, D.M.; et al. (Eds.) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 273–310, 2020. [CrossRef]

- van Wilgen, B.W.; Wilson, J.R. (Eds.) . The status of biological invasions and their management in South Africa in 2017. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Kirstenbosch and DST-NRF Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biology, Stellenbosch, 2018.

- van Wilgen, B.W.; Zengeya,T. A.; Richardson, D.M. A review of the impacts of biological invasions in South Africa. Biol. Invas. 2022, 24, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waker, S. 2001. Introducing a “New Species”: the South African Himalayan Tahr. Zoos Print 2001, 16, 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wandeler, A.I.; Matter, H.C.; Kappeler, A.; Budde, A. The ecology of dogs and canine rabies: a selective review. Revue sci. techn., 1993, 12, 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, B.P.; Cooper, J. Introduction, present status and control of alien species at the Prince Edward Islands, Sub-Antarctic, 1986.

- Williams, A.J.; Siegfried, W.R.; Burger, A.E.; Berruti, A. The Prince Edward Islands: a sanctuary for seabirds in the Southern Ocean. Biological Conservation, 1979, 15, 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, L.; Wallace, G.E. Impacts of feral and free-ranging cats on bird species of conservation concern. Other Publications in Wildlife Management.

- World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1996). "Leiolopisma mauritiana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 3277. [CrossRef]

| Species scientific name | Species common name | Family | Original range | Translocated to |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kobus ellipsiprymnus ellipsiprymnus | Waterbuck | Bovidae | South Africa | Nam., Senegal |

| Kobus vardonii | Puku | Bovidae | South Africa | South Africa |

| Kobus leche | Lechwe | Bovidae | South Africa | South Africa |

| Syncerus caffer | African Savanna Buffalo | Bovidae | Africa | South Africa, Namibia |

| Aepyceros melampus petersi | Black-faced Impala | Bovidae | Namibia, Angola | Angola, Namibia |

| Antidorcas marsupialis | Springbok | Bovidae | South Africa | South Africa, Namibia |

| Redunca arundineum | Common Reedbuck | Bovidae | South Africa | Namibia |

| Redunca fulvorufula | Mountain Reedbuck | Bovidae | South Africa | Namibia |

| Pelea capreolus | Grey rhebok | Bovidae | South Africa | South Africa |

| Oryx dammah | Scimitar-horned Oryx | Bovidae | N Africa | South Africa |

| Oryx gazella gazella | Southern Oryx | Bovidae | South Africa | Senegal |

| Tragelaphus derbianus | Derby’s Eland | Bovidae | C and W Africa | South Africa |

| Tragelaphus euryceros | Bongo | Bovidae | Central Africa | South Africa |

| Tragelaphus imberbis | Lesser Kudu | Bovidae | NE Africa | South Africa |

| Tragelaphus scriptus | Greater Kudu | Bovidae | South Africa | South Africa; Tanzania: Rubondo (240 km2), Lake Victoria island |

| Tragelaphus angasi | Nyala | Bovidae | South Africa | Botswana, Namibia, Angola |

| Tragelaphus spekii | Sitatunga | Bovidae | Southern Africa | South Africa; Tanzania: Rubondo (240 km2), Lake Victoria island |

| Taurotragus oryx oryx | Common Eland | Bovidae | Southern Africa | Senegal |

| Cephalophus natalensis | Natal Duiker | Bovidae | South Africa | South Africa |

| Neotragus moschatus | Suni | Bovidae | South Africa | South Africa, Tanzania: Rubondo (240 km2), Lake Victoria island |

| Madoqua kirkii | Kirk’s Dik-dik | Bovidae | E Africa | South Africa |

| Capra ibex | Nubian Ibex | Bovidae | NE Africa | Namibia |

| Hippotragus niger | Sable Antelope | Bovidae | Botswana, Namibia, Angola | South Africa |

| Hippotragus equinus koba | Roan Antelope | Bovidae | West Africa | South Africa; Tanzania: Rubondo (240 km2), Lake Victoria island |

| Damaliscus pygargus dorcas | Bontebok | Bovidae | South Africa | South Africa |

| Damaliscus pygargus phillipsi | Blesbok | Bovidae | NE South Africa | SW South Africa, Botswana, Moz., Namibia, Zimbabwe, Angola |

| Beatragus hunteri | Hirola | Bovidae | SE Kenya | W Kenya (Tsavo) |

| Oreotragus oreotragus | Klipspringer | Bovidae | South Africa | South Africa |

| Connochaetes gnou | Black Wildebeest | Bovidae | Africa | Namibia |

| Connochaetes taurinus | Blue Wildebeest | Bovidae | Africa | Gabon: WW P.R., <1986, now?? |

| Giraffa camelopardalis | Giraffa | Giraffidae | South Africa | South Africa; Tanzania: Rubondo (240 km2), Lake Victoria island |

| Equus zebra hartmannae | Hartmann’s Mountain Zebra | Equidae | Namibia | South Africa: Western cape, Eastern Cape |

| Diceros bicornis michaeli | Black Rhinoceros | Rhinocerotidae | Kenya | South Africa; Tanzania: Rubondo (240 km2), Lake Victoria island |

| Ceratotherium simum simum | White Rhinoceros | Rhinocerotidae | South Africa, Kenya | Uganda, Kenya, Zambia |

| Loxodonta africana | African Elephant | Loxodontidae | Africa | Tanzania: Rubondo (240 km2), Lake Victoria island |

| Panthera leo melanochaita | African Lion | Felidae | South Africa | Rwanda |

| Colobus abyssinicus | Angola Pied Colobus | Cercopithecidae | Central Africa | Tanzania: Rubondo (240 km2), Lake Victoria island |

| Cercopithecus aethiops | Vervet Monkey | Cercopithecidae | Africa | Tanzania: Rubondo (240 km2), Lake Victoria island |

| Pan troglodytes | Chimpanzee | Hominidae | Cental Africa | Tanzania: Rubondo (240 km2), Lake Victoria island |

| Species scientific name | Common scientific name | Family | RDB status | Effects | Place | Alien mammals | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMPHIBIA | |||||||

| Sooglossus thomasetti | Thomasset's Seychelles Frog | Sooglossidae | E, CR | P** | Seychelles | Tenrecus ecaudatus | Lever 1994 |

| Sooglossus sechellensis | Seychelles Frog | Sooglossidae | E, EN | P** | Seychelles | Tenrecus ecaudatus | Lever 1994 |

| Sechellophryne gardinieri | Gardiner's Seychelles Frog | Sooglossidae | E. EX | P** | Seychelles | Tenrecus ecaudatus | Lever 1994 |

| REPTILIA | |||||||

| Casarea dussumieri | Round Island keel-scaled Boa | Bolyeriidae | E, EX 1975 | H*** | Mauritius: Round Island | Goat, rabbit, hare | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Madatyphlops cariei | Hoffstetter's worm snake | Typhlopidae | E, EX c.1800 | P*** | Mauritius | Cat, dog, other intr. carnivores | Cole 2021 |

| Chioninia coctei | Cape Verde Giant Skink | Scincidae | E, EX:1996 | P** | Cape Verde | (Dog, cat) | Mateo et al. 2020 |

| Gongylomophus bojeri | Bojer’s Skink | Scincidae | E, CR | H** | Mauritius: Round Island | Suncus murinus (goat, rabbit) | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Gongylomorphus fontenayi | Orange-tailed Skink | Scincidae | E, EN | P, H ** | Mauritius: Gunner’s Quoin | Rat, hare, rabbit | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Leiolopisma ceciliae | Reunion Giant Skink | Scincidae | E, EX c.1700 | P** | Reunion | Rats (intr.1670) | Sanchez et al. 2020 |

| Leiolopisma mauritiana | Mauritian Giant Skink | Scincidae | E, EX? | P** | Mauritius | Rats? | WCMC 1996 |

| Leiolopisma telfairii | Telfair’s Skink | Scincidae | E, VU | H* | Mauritius: Round Is., G. Quoin | Goat and rabbit | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Phelsuma gigas | Rodrigues giant day gecko | Scincidae | E, EX 1842 | P*** | Rodrigues, Frigate Is. | Brown Rat | WCMC 1996 |

| Trachylepis comorensis | Comorian Skink | Scincidae | E, LC | P*** | Comoros, Moz., Madagascar | Rats | Animalia.bio.comoros |

| Trachylepis socotrana | Socotra Skink | Scincidae | E, LC | P* | Socotra | Cat, Rat, Mouse | Animalia.bio.socotra |

| Nactus durrelli | Durrell’s Night gecko | Gekkonidae | E, VU | H** | Mauritius: Round Island | Goat, rabbit | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Nactus coindemirensis | Lesser Night Gecko | Gekkonidae | E, VU | P, H ** | Mauritius: Gunner’s quoin | Rat, hare, rabbit | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Phelsuma guentheri | Günther’s Gecko | Gekkonidae | E, EN | H** | Mauritius: Round Is., Il. Aigrettes | Goat, rabbit | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Tarentola gigas | Cape Verde Giant Gecko | Phyllodactyli-dae | E, EN | P*** | Cape Verde | Cats, rat, mouse | Delgado et al. 2021 |

| Psammobates geometricus | Geometric Tortoise | Testudinidae | E, CR | P* | SA: W. Cape | Feral pig, cat | Measey et al. 2020 |

| Aldabrachelys abrupta | Abrupt giant tortoise | Testudinidae | E, EX 1230-1315 | P* | Madagascar | Feral pig, cat | Kehlmaier et al. 2023 |

| Aldabrachelys gigantea daudinii | Daudin's giant tortoise | Testudinidae | E, EX c.1850 | P* | Seychelles: Mahe | Feral pig, cat | Rhodin et al. 2015 |

| Cylindraspis indica | Réunion giant tortoise | Testudinidae | E, EX c.1840 | P* | Reunion | Feral pig, cat | Rhodin et al. 2015 |

| Cylindraspis inept | Mauritius Giant Tortoise | Testudinidae | E, EX 1844 | P* | Mauritius | Feral pig, cat | Rhodin et al. 2015 |

| AVES | |||||||

| Hirundo atrocaerulea | Blue Swallow | Hirundinidae | E, EN | H* | SA: Mpumalanga | Feral Horse | Measey et al. 2020 |

| Terpsiphone corvina | Seychelles Black Parad. Flycatcher | Monarchidae | E, VU | P* | Seychelles: La Digue | Cat, rat | Rocamora and Henriette (2015) |

| Copsychus sechellarum | Seychelles Magpie Robin | Muscicapidae | E, EN | P* | Seychelles: Aride Denis, Frégate, | Cat, rat | Rocamora and Henriette (2015) |

| Humboldia flavirostris | Humbolt’s Flycatcher | Muscicapidae | E, VU | P, C* | Comoros | Black Rat, Com. Myna? | Animalia.bio.comoros |

| Coracina newtoni | Réunion Cuckooshrike | Campepha-gidae | E, CR | P, H* | Reunion | Rat, cat, (deer) | Ghestemme and Salamolard (2007) |

| Zosterops modestus | Seychelles White-eye | Zosteropidae | E, VU | P* | Seychelles | Cat, rat | Rocamora and Henriette (2015) |

| Zosterops chloronothos | Mauritius Olive White-eye | Zosteropidae | E, CR | P* | Mauritius: Ile aux Aigrettes | Rat, cat, mongoose | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Zosterops semiflavus | Marianne white-eye | Zosteropidae | E, EX 1892 | P** | Seychelles: Marianne Isl. | Blak rat | Hume 2017 |

| Acrocephalus seychellensis | Seychelles Warbler | Acrocephalidae | E, NT | P* | Seychelles | Cat, rat | Rocamora and Henriette (2015) |

| Nesillas aldabrana | Aldabra Brush Warbler | Acrocepha-lidae | E, EX 1994 | P, H ** | Seychelles: Aldabra | Rat, cat, goat | BL Int. 2016 |

| Foudia sechellarum | Seychelles Fody | Ploceidae | E, NT | P* | Seychelles: Denis | Cat, rat | Rocamora and Henriette (2015) |

| Foudia rubra | Mauritius Fody | Ploceidae | E, EN | P** | Mauritius: Ile aux Aigrettes | Rat, cat, mongoose | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Foudia delloni | Reunion Fody | Ploceidae | E, EX 1675-1680 | P* | Reunion | Rats | Cheke 2013 |

| Onychognathus frater | Socotra Starling | Sturnidae | E, LC | P* | Socotra | Cat | Animalia.bio.socotra |

| Necropsar rodericanus | Rodrigues Starling | Sturnidae | E, EX 1726 | P* | Rodrigues | Rat | Cheke 2013 |

| Fregilupus varius | Hoopoe Starling | Sturnidae | E, EX 1837 | P, H* | Reunion | Rat, cat, goat? | BL Int. 2016 |

| Chalcomitra balfouri | Socotra Sunbird | Nectariniidae | E, LC | P* | Socotra | Cat | Animalia.bio.socotra |

| Hypsipetes cowlesi | Rodrigues Bulbul | Pycnonotidae | E, EX+? | P* | Rodrigues | Rat? | Cheke 2013 |

| Cisticola haesitatus | Socotra Cisticola | Cisticolidae | E, LC | P* | Socotra | Cat | Animalia.bio.socotra |

| Incana incana | Socotra Warbler | Cisticolidae | E, LC | P* | Socotra | Cat | Animalia.bio.socotra |

| Passer insularis | Socotra Sparrow | Passeridae | E, LC | P* | Socotra | Cat | Animalia.bio.socotra |

| Rhynchostruthus socotranus | Socotra Golden-winged Grosbeak | Fringillidae | E, LC | P* | Socotra | Cat | Animalia.bio.socotra |

| Emberiza socotrana | Socotra Bunting | Emberizidae | E, VU | P** | Socotra | Cat, Rat, Indian Small Civet | Animalia.bio.socotra |

| Phaethon aethereus | Red-billed Tropicbird | Phaethonti-dae | LC | P** | Cape Verde | Cat, dog, rat, mouse | Sanchez 2020; Semedo et al. 2020 |

| Phaethon lepturus | White-tailed Tropicbird | Phaethonti-dae | LC | P* | Seychelles: Ile du Nord | Rat | Rocamora and Henriette (2015) |

| Sula dactylatra | Masked Booby | Sulidae | LC | P* | Seychelles: Grande Ile | Rat | Rocamora and Henriette (2015) |

| Sula leucogaster | Brown Booby | Sulidae | LC | P** | Tromelin Island | Cat, dog, rat, mouse | Semedo et al. 2020 |

| Papasula abbottii | Abbott’s Booby | Sulidae | EN | P** | Mascarenes, +c.1670 | (Monkey) | Cheke 2013 |

| Hydrobates jabejabe | Cape Verde Storm-petrel | Hydrobatidae | E, NT | P** | Cape Verde | Cat, dog, rat, mouse | Sanchez 2020; Semedo et al. 2020 |

| Pelagodroma marina | White-faced Storm-petrel | Procellariidae | LC | P** | Cape Verde | Cat, dog, rat, mouse | Sanchez 2020; Semedo et al. 2020 |

| Calonectris edwardsii | Cape Verde Shearwater | Procellariidae | E, NT | P** | Cape Verde | Cat, dog, rat, mouse | Sanchez 2020; Semedo et al. 2020 |

| Bulweria bulwerii | Bulwer’s Petrel | Procellariidae | LC | P** | Cape Verde | Cat, dog, rat, mouse | Sanchez 2020; Semedo et al. 2020 |

| Pterodroma feae | Cape Verde Petrel | Procellariidae | E, NT | P** | Cape Verde | Cat, dog, rat, mouse | Sanchez 2020; Semedo et al. 2020 |

| Puffinus lherminieri boydi | Boyd's Shearwater | Procellariidae | E, LC | P** | Cape Verde | Cat, dog, rat, mouse | Sanchez 2020; Semedo et al. 2020 |

| Fregata magnificens | Magnificent Frigatebird | Procellariidae | LC | P** | Cape Verde | Cat, dog, rat, mouse | Sanchez 2020; Semedo et al. 2020 |

| Ardenna pacifica | Wedged-tailed Shearwater | Procellariidae | LC | P* | Seychelles | Rat | Rocamora and Henriette (2015) |

| Ardenna pacifica | Wedged-tailed Shearwater | Procellariidae | LC | H* | Mauritius: Round Island | Goat, rabbit | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Pseudobulwaria aterrima | Mascarene Black Petrel | Procellariidae | E, CR | P* | Rodrigues | Cat? | Cheke 2013 |

| Leucocarbo melanogenis | Crozet Shag | Phalacrocoracidae | NE, CR | P** | Marion Islands | Mouse, cat | Bester et al. 2002; Dilley et al. 2016 |

| Phalacrocorax africanus | African Reed Cormorant | Phalacrocoracidae | LC | P* | Mascarenes, +1710 | Rat, feral cat, pigs | Cheke 2013 |

| Phalacrocorax nigrogularis | Socotra Cormorant | Phalacrocoracidae | E, VU | P* | Socotra | Cat | Muzaffat & Benjamin 2013 |

| Diomedea exulans | Wandering Albatross | Diomedeidae | VU | P** | Marion Islands | Mouse, cat | Bester et al. 2002; Dilley et al. 2016 |

| Thalassarche chrysostoma | Grey-headed Albatross | Diomedeidae | NE | P** | Marion Islands | Mouse, cat | Bester et al. 2002; Dilley et al. 2016 |

| Thalassarche carteri | Indian Yellow-nosed Albatross | Diomedeidae | EN | P** | Marion Islands | Mouse, cat | Bester et al. 2002; Dilley et al. 2016 |

| Phoebetria fusca | Sooty Albatross | Diomedeidae | NE, EN | P** | Marion Islands | Mouse, cat | Bester et al. 2002; Dilley et al. 2016 |

| Phoebetria palpebrata | Light-mantled Albatross | Diomedeidae | NT | P** | Marion Islands | Mouse, cat | Ryan 2015; Dilley et al. 2016 |

| Gygis alba | White Tern | Laridae | LC | P** | Tromelin Is. | Rat | Le Corre et al. (2015) |

| Larus dominicanus | Kelp Gull | Laridae | LC | P* | Marion Islands | Mouse, cat | Bester et al. 2002; Dilley et al. 2016 |

| Stercorarius antarcticus | Brown Skua | Laridae | LC | P* | Marion Islands | Mouse, cat | Bester et al. 2002; Dilley et al. 2016 |

| Aptenodytes patagonicus | King Penguin | Spheniscidae | LC | P* | Marion Islands | Mouse, cat | Bester et al. 2002; Dilley et al. 2016 |

| Eudyptes chrysolophus | Macaroni Penguin | Spheniscidae | LC | P* | Marion Islands | Mouse, cat | Bester et al. 2002; Dilley et al. 2016 |

| Alopochen mauritiana | Mauritius Sheldgoose | Anatidae | E, EX c.1695 | P* | Mauritius | Rat, feral cat, pig | Cheke 2013 |

| Alopochen kervazori | Reunion Sheldgoose | Anatidae | E, EX c.1700 | P** | Reunion | Rat, feral cat, pig | Cheke 2013 |

| Anas theodori | Mascarene Teal | Anatidae | E, EX c.1700 | P** | Mauritius | Rat, feral cat, pig | Cheke 2013 |

| Threskiornis solitarius | Reunion Ibis | Threskiorni-thidae | E, EX 1761 | P** | Reunion | Rat, feral cat, pig | Cheke 2013 |

| Bostrychia bocagei | São Tomé Ibis | Threskiorni-thidae | E, CR | P* | São Tomé Is. | Cat, Least Weasel, rat | Hugulay et al. 2014 |

| Nycticorax mauritianus | Mauritius Night Heron | Ardeidae | E, EX 1693 | P** | Reunion | Rat, feral cat, pig | Cheke 2013 |

| Nicticorax megacephalus | Rodrigues Night Heron | Ardeidae | E, EX 1726 | P** | Rodrigues | Rat, feral cat | Cheke 2013 |

| Pelecanus rufescens | Pink-backed Pelican | Pelecanidae | LC | P* | Madagascar +1960’s | Ras, cat? | Goodman 2022 |

| Aphanopteryx bonasia | Mauritius Reed Rail | Rallidae | E, EX c.1695 | P* | Mauritius | Monkey, pig, rat | Cheke 2013 |

| Dryolimnas augusi | Reunion Rail | Rallidae | E, EX 1675-1705 | P* | Reunion | Rat, feral cat, pig | Cheke 2013 |

| Dryolimnas cuveri abboti | Assumption White-thr. Rail | Rallidae | E, EX 1908 | P** | Seychelles: Assumption Isl. | Rats | Hume 2017 |

| Erythromachus leguati | Rodrigues Rail | Rallidae | E, EX c.1726 | P* | Rodrigues | Rat, feral cat, pig | Cheke 2013 |

| Porphyrio caerulescens | Reunion Blue Gallinule | Rallidae | E, EX c.1720 | P* | Reunion | Cat, rat | Cheke 2013 |

| Porphyrio sp. | Seychelles Swamphen | Rallidae | E, EX c.1730 | P* | Reunion | Cat | Hume 2017 |

| Fulica newtoni | Mascarene Coot | Rallidae | E, EX 1693 | P* | Mauritius, Reunion | Rat, pig, cat | Cheke 2013 |

| Raphus cucullatus | Dodo | Columbidae | E, EX 1640’s | P, H* | Mauritius | Black Rat, pig, goat | Cheke 2013 |

| Peziphaps solitarius | Rodrigue’s Solitaire | Columbidae | E, EX c.1770 | P* | Mascarenes | Cats | Cheke 2013 |

| Columba thiriouxi | Mauritius Wood Pigeon | Columbidae | E, EX | P* | Mauritius | Black Rat | Cheke 2013 |

| Nesoenas duboisi | Reunion Pink Pigeon | Columbidae | E, EX c.1700 | P** | Rodrigues | Cat | Cheke 2013 |

| Nesoenas rodericana | Rodrigues Turtle Dove | Columbidae | E, EX 1726-1761 | P** | Rodrigues | Rat, cat | Cheke 2013 |

| Nesoenas cicur | Mauritius Turtle Dove | Columbidae | E, EX c.1730 | P** | Mauritius | Rat, cat | Cheke 2013 |

| Nesoenas mayeri | Pink Pigeon | Columbidae | E, VU | P** | Mauritius: Ile aux Aigrettes | Rat, cat, mongoose | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Alectroenas nitidissima | Mauritius Blue Pigeon | Columbidae | E, EX 1826 | P* | Mauritius | Cats? | Cheke 2013 |

| Alectroenas payandeei | Rodrigues Blue Pigeon | Columbidae | E, EX <1691 | P* | Rodrigues | Rats? | Cheke 2013 |

| Mascarinus mascarinus | Mascarene Parrot | Psittaculidae | E, EX 1784 | P** | Reunion | Rats, cat | Cheke 2013 |

| Necropsittacus rodericanus | Rodrigues Parrot | Psittaculidae | E, EX c.1770 | P** | Rodrigues | Rat, cat | Cheke 2013 |

| Lophopsittacus mauritianus | Broad-billed Parrot | Psittaculidae | E, EX 1670’s? | P* | Mauritius | Monkey, rat | Cheke 2013 |

| Psittacula echo | Echo Parakeet | Psittaculidae | E, VU | P** | Mauritius: Mauritius | Rat, cat, mongoose | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Psittacula exsul | Newton’s Parakeet | Psittaculidae | E, EX 1875 | P** | Rodrigues | Rat, cat, mongoose? | Hume 2017 |

| Otus suazieri | Mauritius Scops Owl | Strigidae | E, EX 1837 | P* | Mauritius | Rat | Cheke 2013 |

| Otus grucheti | Reunion Scops Owl | Strigidae | E, EX 1700’s | P* | Reunion | Cat and rat | Cheke 2013 |

| Otus murivorus | Rodrigues Scops Owl | Strigidae | E, EX 1726-1761 | P* | Rodrigues | Rat | Cheke 2013 |

| Otus pauliani | Grande Comore Scops Owl | Strigidae | E, EN | P** | Comoros | Rat | Birdlife Datazone |

| Otus moheliensis | Moheli Scops Owl | Strigidae | E, EN | P* | Comoros | Black Rat? | Animalia.bio.comoros |

| Falco punctatus | Mauritius Kestrel | Falconidae | E, EN | P** | Mauritius: Mauritius | Rat, cat, mongoose | Cheke and Hume (2008) |

| Circus maillardi | Reunion Harrier | Accipitridae | E, EN | P* | Reunion, Mauritus+1606 | Rat, cat, mongoose? | Goodman 2022 |

| Aepyornis maximus | Elephant Bird | Aepyorni-thidae | E, EX 1100-700 BP | P* | Madagascar | Dog | Hansford & Turvey 2018 |

| Aepyornis hildebrandti | Hildebrand’s Elephant Bird | Aepyorni-thidae | E, EX 1040-1380 AD | P* | Madagascar | Dog | Hansford & Turvey 2018 |

| Mullerornis modestus | Elephant Bird | Aepyorni-thidae | E, EX 680-880 AD | P* | Madagascar | Dog | Hansford & Turvey 2018 |

| MAMMALIA | |||||||

| Gymnuromys robertsi | Voalavoanala | Nesomyidae | E, LC | C* | Madagascar | Black Rat? | Lehtonen 2013Goodman 1995 |

| Nesomys audeberti | White-bellied Nesomys | Nesomyidae | E, LC | C* | Madagascar | Black Rat? | Miljutin & Lehtonen 2008 |

| Nesomys rufus | Island Mouse | Nesomyidae | E, LC | C* | Madagascar | Black Rat? | Miljutin & Lehtonen 2008 |

| Eliurus tanala | Tanala Tufted-tailed Rat | Nesomyidae | E, LC | C* | Madagascar | Black Rat? | Miljutin & Lehtonen 2008 |

| Eliurub webbi | Webbie’s Tufted-tailed Rat | Nesomyidae | E, LC | C* | Madagascar | Black Rat? | Miljutin & Lehtonen 2008 |

| Pachylemur insignis | Giant Lemur | Lemuridae | E, EX c.1500 | P* | Madagascar | Dog | Godfrey & Jungers 2003 |

| Eulemur fulvus | Common Brow Lemur | Lemuridae | E, VU | P* | MadagascarMayotte (introd.) | Dog | Hixon et al. 2021 |

| Propithecus verreauxi | Verreaux’s Sifaka | Indridae | E, CR | P* | Madagascar | Dog | Hixon et al. 2021 |

| Archaeolemur majori | Baboon Lemur | Archaeolemuridae | E, EX 1100-700 BP | P* | Madagascar | Dog | Hixon et al. 2021 |

| Archeolemur edwardsi | Monkey Lemur | Archaeolemuridae | E, EX, 500 BP | P* | Madagascar | Dog) | Godfrey et al. 2009 |

| Hadropithecus stenognathus | Monkey Lemur | Archaeolemuridae | E, EX 444–772 | P, H** | Madagascar | Feral cattle, pig and dog | Godfrey et al. 2009 |

| Megaladapsis madagascariens. | Koala Lemur | Megaladapidae | E, EX 500-600BP | P* | Madagascar | Dog? | Godfrey et al. 2009 |

| Megaladapsis grandidieri | Koala Lemur | Megaladapidae | E, EX 500-600 BP | P* | Madagascar | Dog? | Godfrey et al. 2009 |

| Megaladapsis edwardsi | Koala Lemur | Megaladapidae | E, EX 500-600 BP | P* | Madagascar | Dog? | Godfrey et al. 2009 |

| Palaeopropithecus ingens | Sloth Lemur | Palaeopropi-thecidae | E, EX 1100-700 BP | P* | Madagascar | Dog | Hixon et al. 2021 |

| Mesopropithecus pithecoides | Sloth Lemur | Palaeopropi-thecidae | E, EX 570-679 CE | P* | Madagascar | Dog | Godfrey et al. 2009 |

| Mesopropithecusglobiceps | Sloth Lemur | Palaeopropi-thecidae | E, EX 570-679 CE | P* | Madagascar | Dog | Godfrey et al. 2009 |

| Mesopropithecusdolichobrachion | Sloth Lemur | Palaeopropi-thecidae | E, EX 570-679 CE | P* | Madagascar | Dog | Godfrey et al. 2009 |

| Babakotia radofilai | Sloth Lemur | Palaeopropi-thecidae | E, EX c.1000 BC | P* | Madagascar | Dog | Hixon et al. 2021 |

| Daubentonia robusta | Giant Aye-aye | Daubentonidae | E, EX 900-1150 CE | P* | Madagascar | Dog) | Crowley 2010 |

| Daubentonia madagascarensis | Aye-aye | Daubentoniidae | E, EN | P* | Madagascar | Black Rat? | Goodman 1995 |

| Cryptoprocta ferax | Fossa | Eupleridae | E, VU | P, C* | Madagascar | Dog | Hixon et al. 2021 |

| Felis silvestris lybica | African Wild Cat | Felidae | LC | P* | Namibia, Botswana, SA | Feral Cat | Measey et al. 2020 |

| Equus zebra | Mountain Zebra | Equidae | VU | H* | SA, N Cape; Namibia | Feral Donkey | Measey et al. 2020 |

| Equus quagga quagga | Quagga | Equidae | EX, c.1878 | G* | SA, Cape, Free State | Feral donkey? | Nowak 1999 |

| Equus africanus africanus | Nubian wild ass | Equidae | EX | G** | Ethiopia/Eritrea: Nubian Desert | Feral Donkey | Kimura et al. 2011 |

| Hippopotamus laloumena | Malagasy Hippo | Hippopotami-dae | E, EX 1670-1950 AD | P, H* | Madagascar | Dog, feral goat | Crowley et al. 1996; Shackelton 2021 |

| Hippopotamus lemerlei | Lemerle's Dwarf Hippopotamus | Hippopotami-dae | E, EX 670-836 AD | P, H* | Madagascar | Dog, feral goat? | Crowley et al. 1996; Shackelton 2021 |

| Hippopotamus madagascarie-nsis | Madagascar Dwarf Hippopotamus | Hippopotami-dae | E, EX 687-880 CE | P, H* | Madagascar | Dog, feral goat? | Crowley et al. 1996; Shackelton 2021 |

| Hippotragus leucophaeus | Bluebuck | Bovidae | EX c.1800 | H* | South Africa: Western Cape | Feral goat, deer | Faith 2014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).