Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Ecological Health Disparity Analysis of County Level Data

3. Results and Discussion

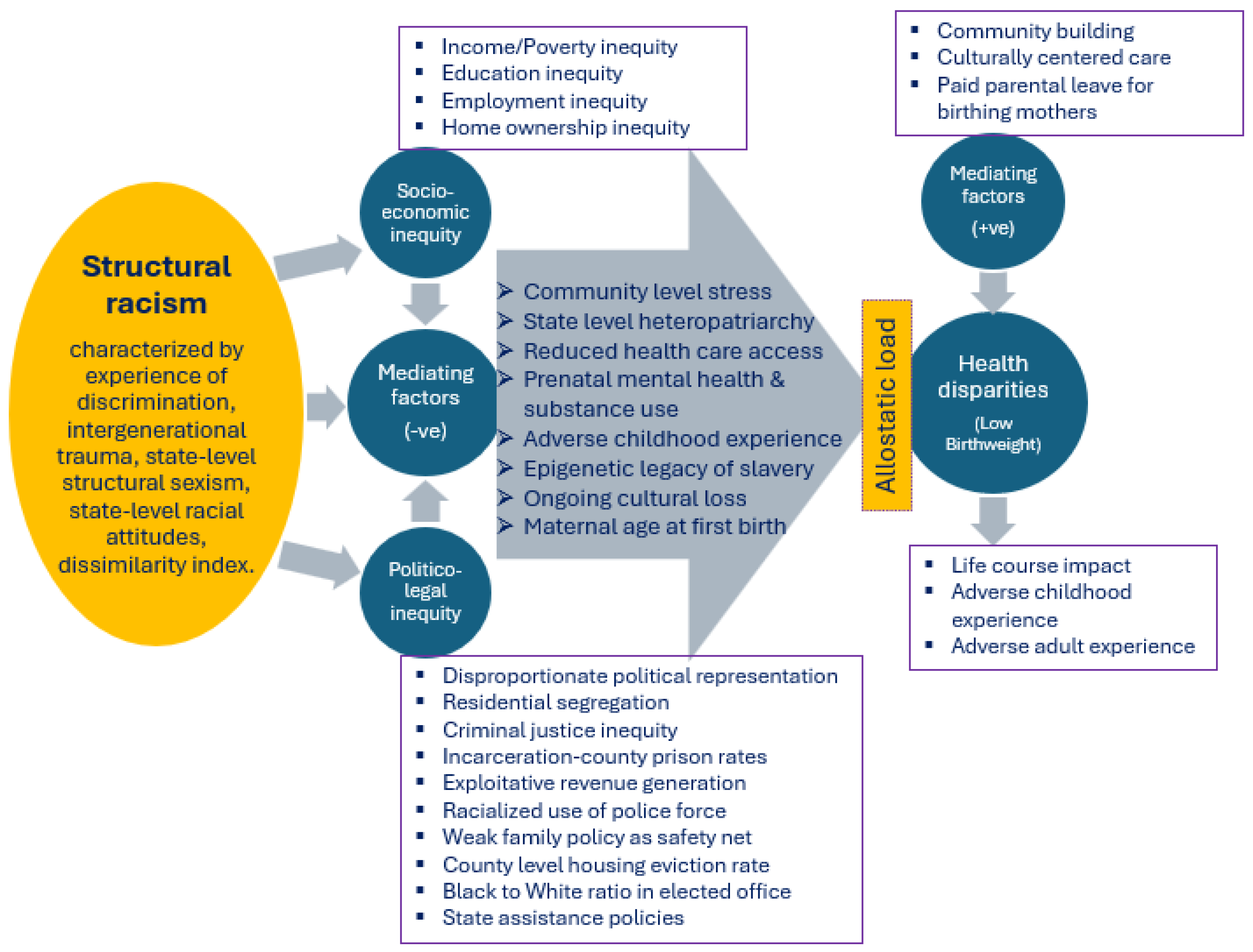

3.1. Literature Review for Contextual Background of Low Birthweight as Pathway for Structural Racism

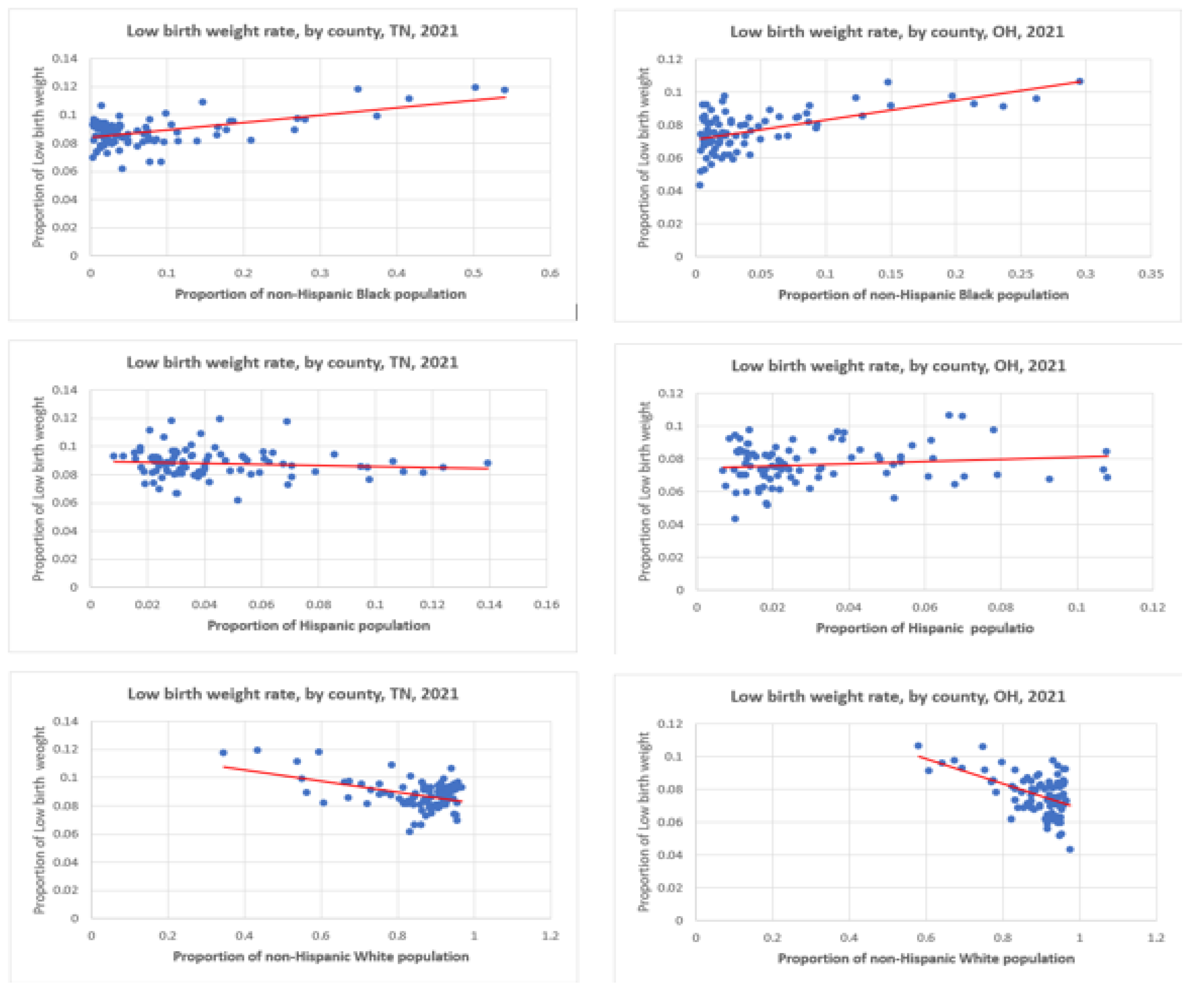

3.2. Ecological Case-Study of Two US Counties

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whitehead, M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv. 1992, 22, 429–445. [CrossRef]

- US CDC. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report United States, 2011. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA.

- PHAC. Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada. 2018. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/science-research/key-health-inequalities-canada-national-portrait-executive-summary/key_health_inequalities_full_report-eng.pdf.

- Rasali, D.; Kao, D.; Fong, D.; Qiyam, L. Priority Health Equity Indicators for British Columbia: Preventable and Treatable Premature Mortality. BC Center for Disease Control, Provincial Health Services Authority, Vancouver, B.C. 2019.

- Rasali, D.; Li, C.; Mak, S.; Rose, C.; Janjua, N.; Patrick, D. Correlations of COVID-19 incidence with neighborhood demographic factors in BC. Annals of Epidemiology 2021, 61, 17. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.H.; Homan, P.A. Frontiers in measuring structural racism and its health effects. Health Serv Res. 2022, 57, 443–447. [CrossRef]

- GBD US Health Disparities Collaborators. Life expectancy by county, race, and ethnicity in the USA, 2000 19: A systematic analysis of health disparities. The Lancet, 2022, 400, 25–38. [CrossRef]

- Gee, G.C.; Ford, C.L. Structural racism and health inequities. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 2011, 8, 115–132. [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N. Discrimination and Health Inequities. Int. J. Health Services 2014, 44, 643–710.

- Bailey, Z.D.; Krieger, N.; Ag nor, M.; Graves, J.; Linos, N.; Bassett, M.T. Structural Racism and Health Inequities in the USA: Evidence and Interventions. The Lancet 2017, 389, 1453–1463. [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, J.A.; Akinyemi, A.A.; Holman, E.A. Parental Preconception Adversity and Offspring Health in African Americans: A Systematic Review of Intergenerational Studies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2023, 24, 1677–1692. [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Lawrence, J.A.; Davis, B.A. Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research. Annual Review of Public Health 2019, 40, 105–125. [CrossRef]

- Rasali, D.P.; Woodruff, B.M.; Alzyoud, F.A.; Kiel, D.; Schaffzin, K.T.; Osei, W.D.; Ford, C.L.; Johnson, S. Cross-Disciplinary Rapid Scoping Review of Structural Racial and Caste Discrimination Associated with Population Health Disparities in the 21st Century. Societies 2024, 14, 186. [CrossRef]

- Global Nutrition Target Collaborators. Global, regional, and national progress towards the 2030 global nutrition targets and forecasts to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025 Dec 21;404, 2543-2583. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Adams, N.; Huang, D.; Glymour, M.M.; Allen, A.M.; Nguyen, Q.C. The Association Between State-Level Racial Attitudes Assessed From Twitter Data and Adverse Birth Outcomes: Observational Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill, 2020, 6, e17103. [CrossRef]

- Chegwin, V.; Teitler, J.; Muchomba, F.M.; Reichman, N.E. Racialized police use of force and birth outcomes. Social Science & Medicine 2023, 321, 115767. [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, J.; Robinson, D.E. State Policies, Racial Disparities, and Income Support: A Way to Address Infant Outcomes and the Persistent Black-White Gap? J Health Politics, Policy & Law 2022, 47, No. 2, April. [CrossRef]

- Patchen, L.; McCullers, A.; Beach, C.; Browning, M.; Porter, S.; Danielson, A.; Asegieme, E.; Richardson, S.R.; Jost, A.; Jensen, C.S.; Ahmed, N. Safe Babies, Safe Moms: A Multifaceted, Trauma Informed Care Initiative. Maternal & Child Health J. 2023, Nov. [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, K.K.; Kapila, P.; Umerani, A.; Hossain, A.; Salah, M.A.; Singisetti, V.; Carter, S.; Boulet, S.I. Political representation and perinatal outcomes to Black, White, and Hispanic people in Georgia: A cross-sectional study. Annals Epid. 2023, 87, 38–44. [CrossRef]

- Blumenshine, P.; Egerter, S.; Barclay, C.J.; Cubbin, C.; Braveman, P.A. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2010, 39, 263–272. [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman-Bunyoli, A.M.; Cheyney, M.; Monroe, S.M.; Wiggins, N.; Vedam, S. Preterm and low birthweight birth in the United States: Black midwives speak of causality, prevention, and healing. Birth 2022, 49, 526–539. [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.A.; Arcaya, M.C.; Williams, D.R.; Krieger, N. The impact of county-level fees & fines as exploitative revenue generation on US birth outcomes 2011 2015. Health & Place 2023, 80, 102990. [CrossRef]

- Mehra, R.; Boyd, L.M.; Ickovics, J.R. Racial residential segregation and adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. & Med. 2017, 191, 237e250. [CrossRef]

- Chantarat, T.; Van Riper, D.C.; Hardeman, R.R. Multidimensional structural racism predicts birth outcomes for Black and White Minnesotans. Health Serv. Res. 2022a, 57, 448-457. [CrossRef]

- Chantarat, T.; Mentzer, K.M.; Van Riper, D.C.; Hardeman, R.R. Where are the labor markets?: Examining the association between structural racism in labor markets and infant birth weight. Health & Place 2022b, 74, 102742. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.E.; Mendola, P.; Liu, D.; Grantz, K.L. Joint Effects of Structural Racism and Income Inequality on Small-for-Gestational-Age Birth. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 1681–1688. [CrossRef]

- Sonderlund, A.L.; Williams, N.L.; Charifson, M.; Ortiz, R.; Sealy-Jefferson, S.; De Leon, E.; Schoenthaler, A. Structural racism and health: Assessing the mediating role of community mental distress and health care access in the association between mass incarceration and adverse birth outcomes. SSM - Population Health 2023, 24, 101529. [CrossRef]

- Everett, B.G.; Limburg, A.; Homan, P.; Philbin, M.M. Structural Heteropatriarchy and Birth Outcomes in the United States. Demography 2022, 59, 89–110. [CrossRef]

- Chambers, B.D.; Erausquin, J.T.; Tanner, A.E.; Nichols, T.R.; Brown-Jeffy, S. Testing the Association Between Traditional and Novel Indicators of County-Level Structural Racism and Birth Outcomes among Black and White Women. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 2018, 5, 966–977. [CrossRef]

- Nagle, A.; Samari, G. State-level structural sexism and cesarean sections in the United States. Soc Sci. 2021, 289, 114406. [CrossRef]

- Mersky, J.P.; Jeffers, N.K.; Lee, C.P.; Shlafer, R.J.; Jackson, D.B.; G mez, A. Linking Adverse Experiences to Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes: A Life Course Analysis of Racial and Ethnic Disparities Among Low? Income Women. J Racial & Ethnic Health Disparities 2023, June. [CrossRef]

- Christian, L.M.; Koenig, J.; Williams, D.P.; Kapuku, G.; Thayer, J.F. Impaired vasodilation in pregnant African Americans: Preliminary evidence of potential antecedents and consequences. Psychophysiology 2012, 58, e13699. [CrossRef]

- Karasek, D.; Raifman, S.; Dow, W.H.; Hamad, R.; Goodman, J.M. Evaluating the Effect of San Francisco s Paid Parental Leave Ordinance on Birth Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11962. [CrossRef]

- Jasthi, D.L.; Nagle-Yang, D.; Frank, S.; Masotya, M.; Huth-Bocks, A. Associations Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Prenatal Mental Health and Substance Use Among Urban, Low? Income Women. Community Mental Health Journal 2012, 58, 595–605. [CrossRef]

- Geronimus, A.T.; Bound, J.; Hughes, L. Trend Toward Older Maternal Age Contributed To Growing Racial Inequity In Very-Low-Birthweight Infants In: The US. Health Aff (Millwood), 2023, 42, 674–682. [CrossRef]

- Harville, E.W.; Wallace, M.E.; Theall, K.P. Eviction as a social determinant of pregnancy health: County-level eviction rates and adverse birth outcomes in the United States. Wiley-Health Soc Care Community 2022, 30, e5579–e5587. [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S.; Stellar, E. Stress and the individual. Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch Intern Med. 1993, 153, 2093–3101. [CrossRef]

- Guidi, J.; Lucente, M.; Sonino, N.; Fava, G.A. Allostatic Load and Its Impact on Health: A Systematic Review. Psychother. Psychosom. 2021, 90, 11–27. [CrossRef]

| Author(s) (Year of Publication) |

Indicator(s) of Structural Racism as Mediating Factors of Impact on Low Birthweight | Extract from the Relevant Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Chantarat et al. (2022a) |

|

|

| Chantarat et al. (2022b) |

|

|

| Wallace et al. (2015) |

|

|

| Sonderlund et al. (2023) |

|

|

| Everett et al. (2022) |

|

|

| Chambers et al. (2018) |

|

|

| Mehra et al., (2017) |

|

|

| Chegwin et al, (2023) |

|

|

| Nagle and Samari (2019) |

|

|

| Pearlman and Robinson (2022) |

|

|

| Nguyen et al. (2020) |

|

|

| Patchen et al. (2023) |

|

|

| Mersky et al. (2023) |

|

|

| Stanhope et al. (2023) |

|

|

| Bridgeman-Bunyoli et al. (2022) |

|

|

| Christian et al. (2021) |

|

|

| Davis et al. (2023) |

|

|

| Karasek et a. (2022) |

|

|

| Jasthi et al. (2022) |

|

|

| Geronimus et al. (2023) |

|

|

| Harville et al. (2022) |

|

|

| Socio-demographic and Health Data | US States | |

|---|---|---|

| Ohio (n = 88) | Tennessee (n = 95) | |

| State total population | 11,780,017 | 6,975,218 |

| % non-Hispanic Black | 12.82 | 16.61 |

| % Hispanic | 4.32 | 6.11 |

| % Asian | 2.66 | 2.02 |

| % non-Hispanic White | 77.67 | 73.08 |

| Poor or Fair Health, % | 14.50 | 15.70 |

| Low Birthweight, % births | 8.56 | 9.13 |

| Teen Births, per 1000 live births | 20.90 | 27.17 |

| Life Expectancy, years | 76.52 | 75.33 |

| Diabetes Prevalence, % | 10.90 | 12.50 |

| Air Pollution Particulate Matter (PM2.5) | 8.9 | 7.6 |

| Severe Housing Problems, % | 13.06 | 13.43 |

| Tennessee | Ohio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P-value | (n) | R | P-value | (n) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.557 ** | 0 | 95 | 0.584 ** | 0 | 88 |

| Hispanic | -0.102 | 0.326 | 95 | 0.127 | 0.239 | 88 |

| Non-Hispanic White | -0.459 ** | 0 | 95 | -0.512 ** | 0 | 88 |

| High School Completion | -0.202 * | 0.05 | 95 | 0.116 | 0.283 | 88 |

| High School Graduation | -0.203 | 0.054 | 90 | -0.401 ** | 0 | 88 |

| School Segregation | 0.249 * | 0.018 | 90 | 0.485 ** | 0 | 87 |

| Income Inequality | 0.263 * | 0.01 | 95 | 0.594 ** | 0 | 88 |

| Median Household Income | -0.294 ** | 0.004 | 95 | -0.391 ** | 0 | 88 |

| Children in Poverty | 0.379 ** | 0 | 95 | 0.600 ** | 0 | 88 |

| Unemployment | 0.559 ** | 0 | 95 | 0.539 ** | 0 | 88 |

| Homeownership | -0.404 ** | 0 | 95 | -0.548 ** | 0 | 88 |

| Severe Housing Problems | 0.473 ** | 0 | 95 | 0.526 ** | 0 | 88 |

| Life Expectancy | -0.348 ** | 0.001 | 95 | -0.549 ** | 0 | 88 |

| Frequent Physical Distress | 0.329 ** | 0.001 | 95 | 0.260 * | 0.015 | 88 |

| Diabetes Prevalence | 0.620 ** | 0 | 95 | 0.529 ** | 0 | 88 |

| HIV Prevalence | 0.398 ** | 0 | 91 | 0.528 ** | 0 | 86 |

| Food Insecurity | 0.339 ** | 0.001 | 95 | 0.528 ** | 0 | 88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).