1. Introduction

Electricity has become a part and parcel of modern life, being ubiquitously employed both in industry and for household use. At that, alternating current (AC)-based equipment is used most widely [

1]. The main advantage of AC consists in the simple transformability of AC voltage [

1]. This allows one to easily build high-voltage AC lines and circuits, making the AC electric-power transmission preferable owing to its cost efficiency [

1]. Accordingly, electric AC transformers represent key components of AC lines and equipment. In Europe, the commercial AC frequency is 50 Hz, pertaining to low frequency range [

2]. In the USA, 60 Hz commercial frequency is employed. The operation of AC equipment, including AC transformers, is known to be accompanied by the induction of electromagnetic fields of respective frequency (low-frequency electromagnetic fields, LFFs). Low-frequency magnetic and electromagnetic fields are known to influence the physicochemical properties and functioning of enzymes [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The typical “meeting point” of the AC equipment and the enzymes is a bioreactor with motor-driven stirring device [

8,

9]. Of course, this is just the most demonstrative case, since the most common situation is the action of LFF on the AC equipment operator, and the processes in the human body are known to be regulated by enzymes [

10]. The action of magnetic (and, hence, electromagnetic [

1]) fields on an enzyme can well lead to a change in its spatial structure [

11,

12], and, accordingly, to the pathological state of the body [

13]. Accordingly, the impact of external electromagnetic fields is one of the most important factors, whose effect on enzymes’ properties attracts attention of the modern science: impact of such fields on the body and, in particular, on enzymes was analyzed in many works [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Of course, the exact effect of an external field on an enzyme depends on the type of the enzyme and the parameters of the field [

4,

11], and the variety of important enzymes is quite wide [

10]. The evident effects of external fields, including LFFs, on enzymes [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] are thus forcing researchers to perform in-deep studies of these phenomena.

In the literature, particular attention is paid to the effects of electromagnetic fields on horseradish peroxidase (HRP) enzyme [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

12], which has found numerous practical applications in both biotechnology and healthcare [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. The functional properties of HRP were shown to change significantly under the action of electromagnetic fields [

23], including LFFs [

2,

3,

5]. Owing to the sensitivity of the adsorption/aggregation properties of HRP to the impacts of electromagnetic fields [

6,

7,

28,

29,

30], this enzyme can be used as an electromagnetic radiation sensor [

6,

7,

30]. In this connection, the sensitivity of methods employed for the detection of changes in the enzyme properties becomes a key point [

28,

29].

In studies of enzymes, various spectroscopy-based methods are commonly employed [

11,

12,

31,

32]. These methods are, however, only helpful when the enzyme under study contains a chromophoric group (for instance, in case of cytochromes P450), or when changes in the enzyme’s spatial structure [

11,

12] or functional activity [

2,

3,

11,

29] are significant. At the same time, the changes in the enzyme’s properties are often quite subtle — though still important with regard to its functionality [

29]. Such changes are barely distinguishable [

11] or completely indistinguishable [

28] by spectroscopic methods. If this is the case, atomic force microscopy (AFM) is quite helpful [

6,

7,

28,

29,

30]. AFM enables visualization of single enzyme molecules, thus allowing the scientists to reveal even subtle changes in the enzyme properties [

6,

7,

28,

29]. Parallel use of AFM and spectroscopic methods is also a good practice [

28,

29,

30].

In the work presented, the effect of incubation of HRP solution near 50 Hz AC equipment on the enzyme’s physicochemical properties of the enzyme has been studied. It has been observed that the incubation of the enzyme above the coil of a loaded autotransformer connected to a laboratory benchtop centrifuge leads to the enhancement of HRP adsorption onto mica; this enhancement is accompanied by the enzyme disaggregation and a slight increase in its activity. Furthermore, the incubation near the switched-off transformer has been found to cause even more significant enzyme disaggregation, while the increase in activity was almost the same as in the case of the loaded transformer. Since 50 Hz AC energized equipment is ubiquitously used in both research laboratories and industry, the results obtained in our experiments are quite important for the correct design of experimental procedures and industrial processes involving enzymes.

2. Materials and Methods

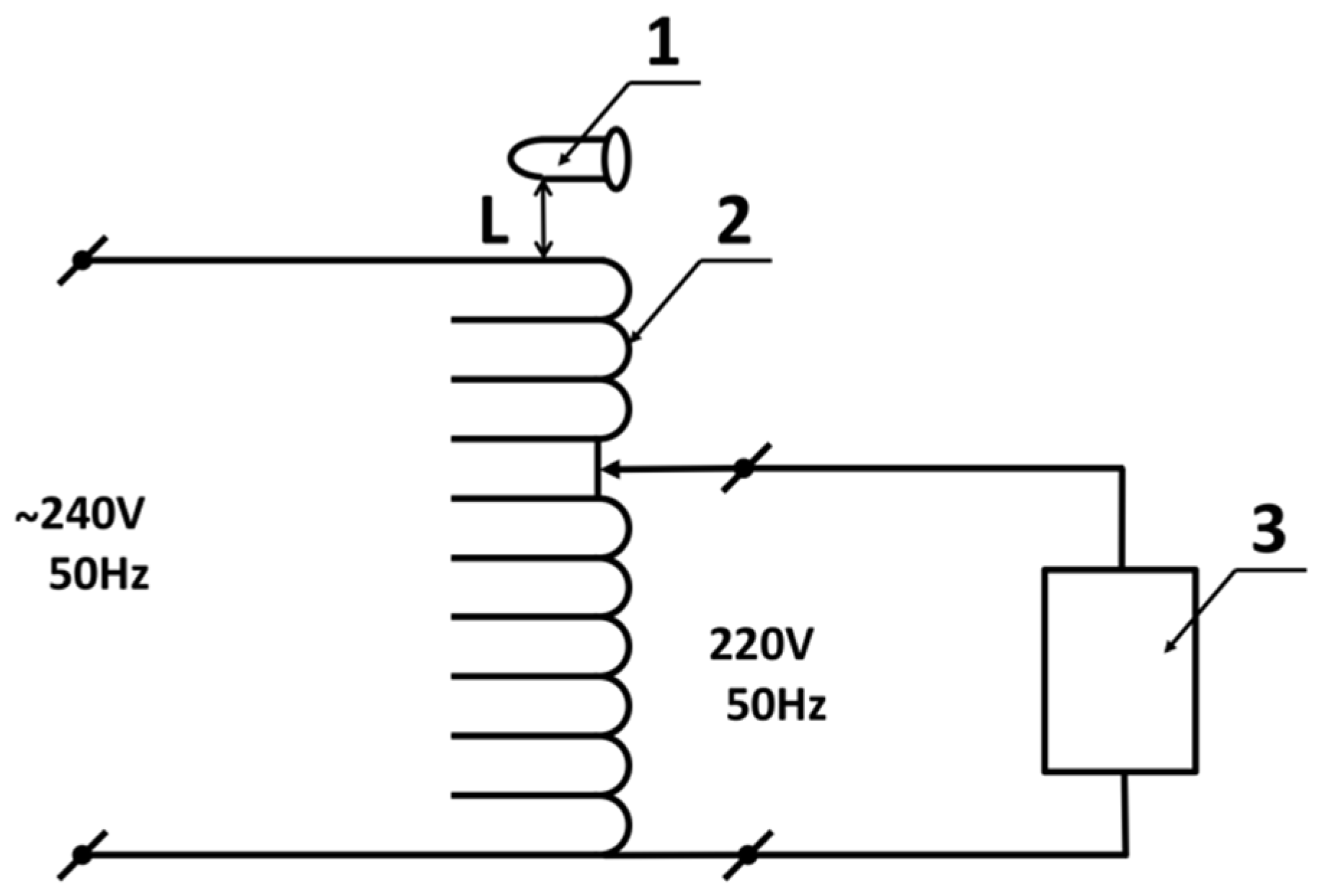

In order to find out how the incubation near the AC-based equipment affects the HRP enzyme, the setup drawn in

Figure 1 was employed. The setup included a standard LATR-1 laboratory regulating autotransformer (Russia) and an Eppendorf 5810 R laboratory centrifuge (Eppendorf, Germany).

At the first step of experiment, the autotransformer was loaded in the following way. The transformer’s input was connected to 240 V, 50 Hz mains power supply. The output voltage was set to 220 V (

Figure 1), and the centrifuge was connected to the transformer output. Then, the centrifuge was switched on, and operated at 3000 rpm.

After that, a test tube with 1 mL of 0.1 µM HRP solution in 2 mM Dulbecco’s modified phosphate buffered saline (the working sample) was placed above the top of the transformer’s coil at a distance of 0.06 m. At the same time, the control sample was kept at much larger (10 m) distance from the experimental setup.

The incubation time of the working sample above the loaded transformer upon the centrifuge operation was 30 minutes. After the incubation, both the working and the control enzyme samples were transferred to AFM analysis (in order to study the enzyme’s adsorption properties) and to spectrophotometric analysis (in order to determine the enzymatic activity).

At the second step of our experiment, after 30 minutes of centrifuge operation, the centrifuge was stopped, switched off, and disconnected from the autotransformer. The latter was disconnected from the mains power supply. Five minutes later, another (untreated) working enzyme sample was placed in the same position above the transformer’s coil, and incubated there for 30 minutes. After this incubation, this sample was also subjected to AFM and spectrophotometric analysis.

The parallel AFM and spectrophotometry analysis of the enzyme samples was performed as described in our previous papers — for instance, in [

28,

29,

30]. In brief, this analysis consisted in the following procedures.

AFM analysis was performed by direct surface adsorption method [

33]. A 800 µL volume of each sample, in which 7 mm×15 mm sheets of bare mica (AFM substrates; SPI, USA) was incubated for 10 min, was analyzed. The mica substrates incubated in either of the sample studied were then scanned in semi-contact mode in air with a Titanium atomic force microscope (NT-MDT, Zelenograd, Russia; the microscope pertains to the equipment of the “Human Proteome” Core Facility of the Institute of Biomedical Chemistry, supported by Ministry of Education and Science of Russian Federation, Agreement 14.621.21.0017, unique project ID: RFMEFI62117X0017). The microscope was equipped with NSG10 cantilevers (TipsNano, Zelenograd, Russia). For each substrate, at least sixteen scans (2 µm×2 µm in size) were obtained in different areas of the substrate. Then, objects visualized in the so-obtained AFM images were counted with a specialized software custom-developed in IBMC. Based on the number of objects calculated on each AFM substrate (that is, for each enzyme sample studied), distributions of the relative number of objects with height

ρ(h) (density functions) and absolute number of AFM-visualized particles

N400 (normalized per 400 μm

2) were obtained and plotted vs. the height of the AFM-visualized objects [

34].

Spectrophotometry measurements were performed based on the well-established technique developed by Sanders et al. [

35]. The absorbance of solution containing 1 nM of HRP enzyme, 0.3 mM azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate) (ABTS) and 2.5 mM H

2O

2 in phosphate-citrate buffer (pH 5.0) [

35,

36] was monitored at 405 nm for 300 seconds in a 1-cm-long quartz cell with an Agilent 8453 spectrophotometer (Agilent Deutschland GmbH, Waldbronn, Gremany) [

28,

29,

30,

31]. For each sample, at least three independent measurements were performed. The results obtained were processed as described in [

37], and presented in the form of absorbance vs. time (

A405(t)) kinetic curves.

3. Results

3.1. AFM Analysis of HRP Adsorption and Aggregation Behaviour

In order to reveal possible changes in the adsorption properties of HRP under experimental conditions, when the enzyme solution was located near the transformer in the on and off modes, control experiments were simultaneously carried out to study the aggregation state of HRP. For this purpose, HRP enzyme solution was placed in test tubes, according to the Materials and Methods section, away from the experimental setup at a distance of 10 m (control experiments), near the working transformer, and near the transformer after it was turned off (working experiments).

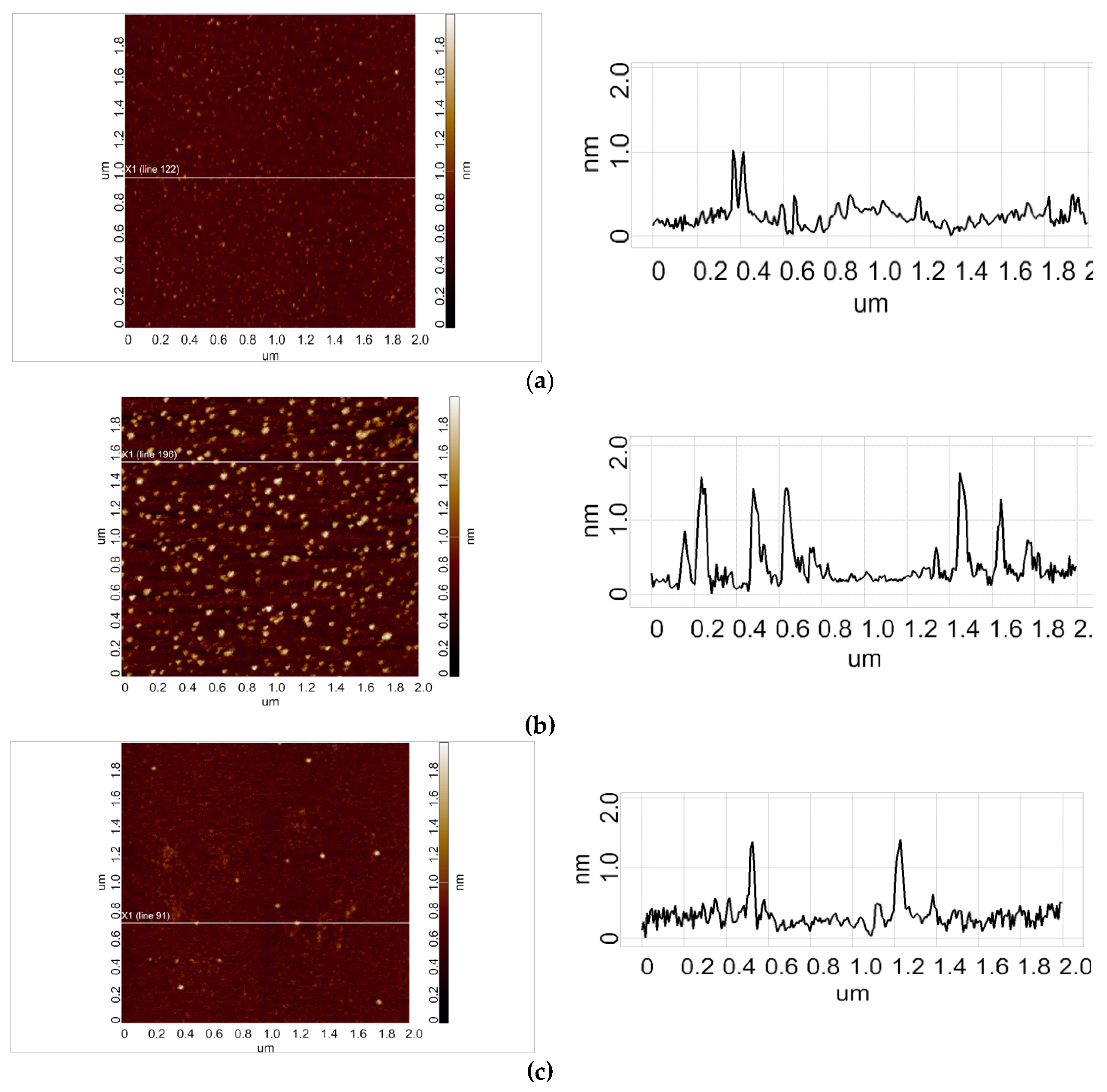

Figure 2 displays typical AFM images of HRP adsorbed on mica substrate after its incubation in either of the working samples (

Figure 2a,b), or in the control sample (

Figure 2c).

AFM images shown in

Figure 2a–c indicate that under our experimental conditions, HRP adsorbs onto mica in the form of compact objects, whose heights reach 2 nm. Further analysis was performed in order to exactly determine the effect of incubation of the enzyme near 50 Hz AC equipment on its adsorption behaviour.

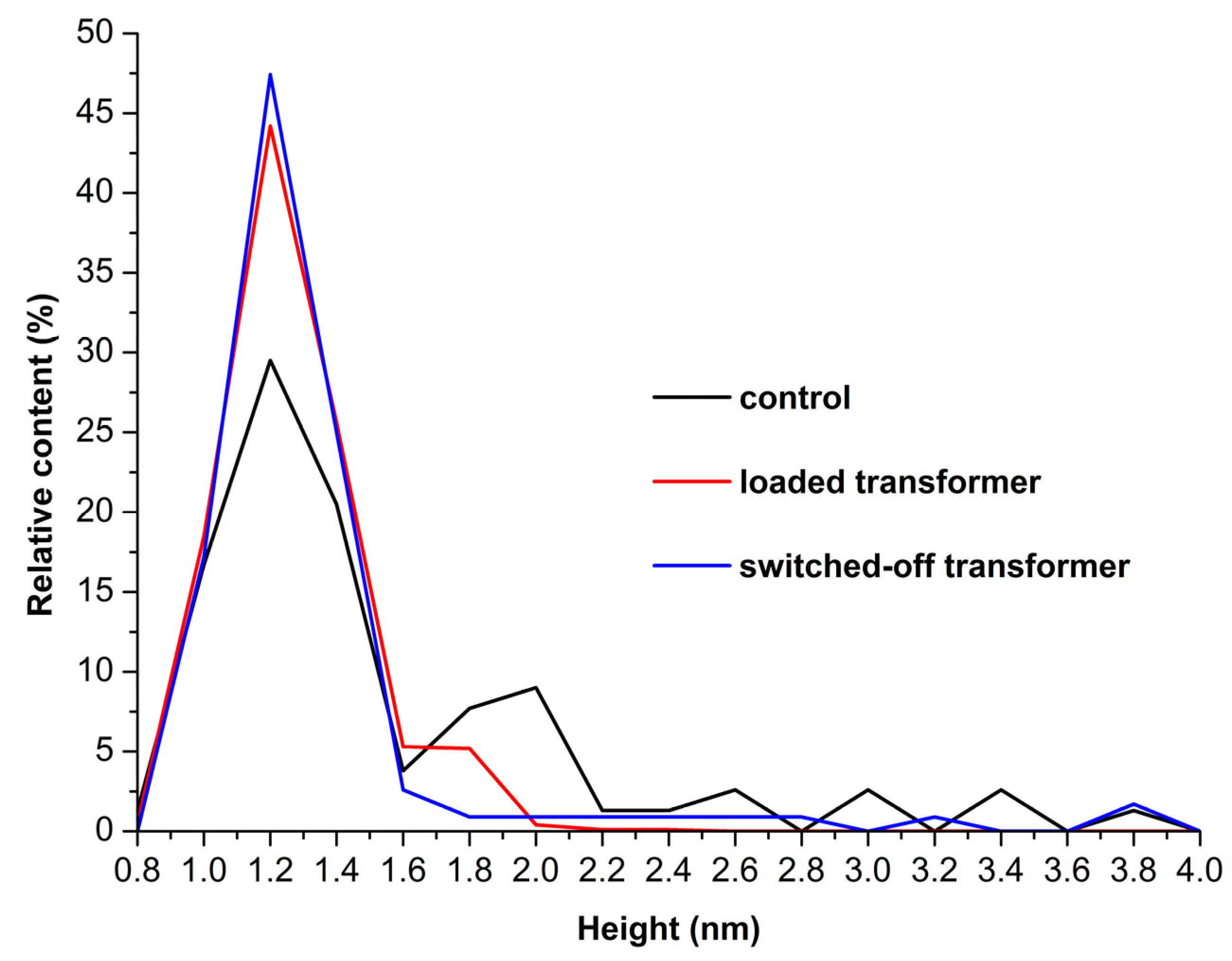

Figure 3 shows

ρ(h) plots obtained for the enzyme samples studied.

On the

ρ(h) curve obtained for the control enzyme sample (

Figure 3, black curve), two maxima at

hmax1 = 1.2 ± 0.2 nm, and at

hmax2 = 2.0 nm ± 0.2 nm can be clearly distinguished. Given that the molecular weight of HRP is between 40 and 44 kDa [

38,

39] and based on our previously reported observations [

28,

29],

hmax1=1.2 nm corresponds to the monomeric state of the enzyme, while

hmax2=2 nm corresponds to its oligomeric state.

Analysis of ρ(h) plots obtained for the working sample of the enzyme, which was incubated near the loaded autotransformer, also exhibits a bimodal character with two maxima observed at hmax1=1.2 ± 0.2 nm, and hmax2=1.8 ± 0.2 nm, respectively. At the same time, the ratio of peak intensities ρ(hmax2)/ρ(hmax1) decreased approximately twofold — as compared with that obtained for the control sample. Both facts — this decrease in ρ(hmax2)/ρ(hmax1) ratio observed for the working sample, and the shift of hmax2 by ~0.3 nm to the left — clearly indicate a disaggregation of the enzyme after its half-hour-long incubation near the loaded 50 Hz AC transformer. At that, the mica-adsorbed HRP represented a mixture of its monomeric and aggregated forms in the both cases described.

At the same time, the results obtained upon the analysis of the working sample incubated near the switched-off transformer were very interesting. Namely, the ρ(h) plot, obtained for this sample, was quite different from the ones discussed above. Namely, it was described by a unimodal distribution function with a maximum at a height of hmax1 = 1.2 ± 0.2 nm, being devoid of the second maximum. That is, the half-hour-long incubation of the sample near the unloaded, switched-off 50 Hz AC transformer led to predominant adsorption of the monomeric form of the enzyme.

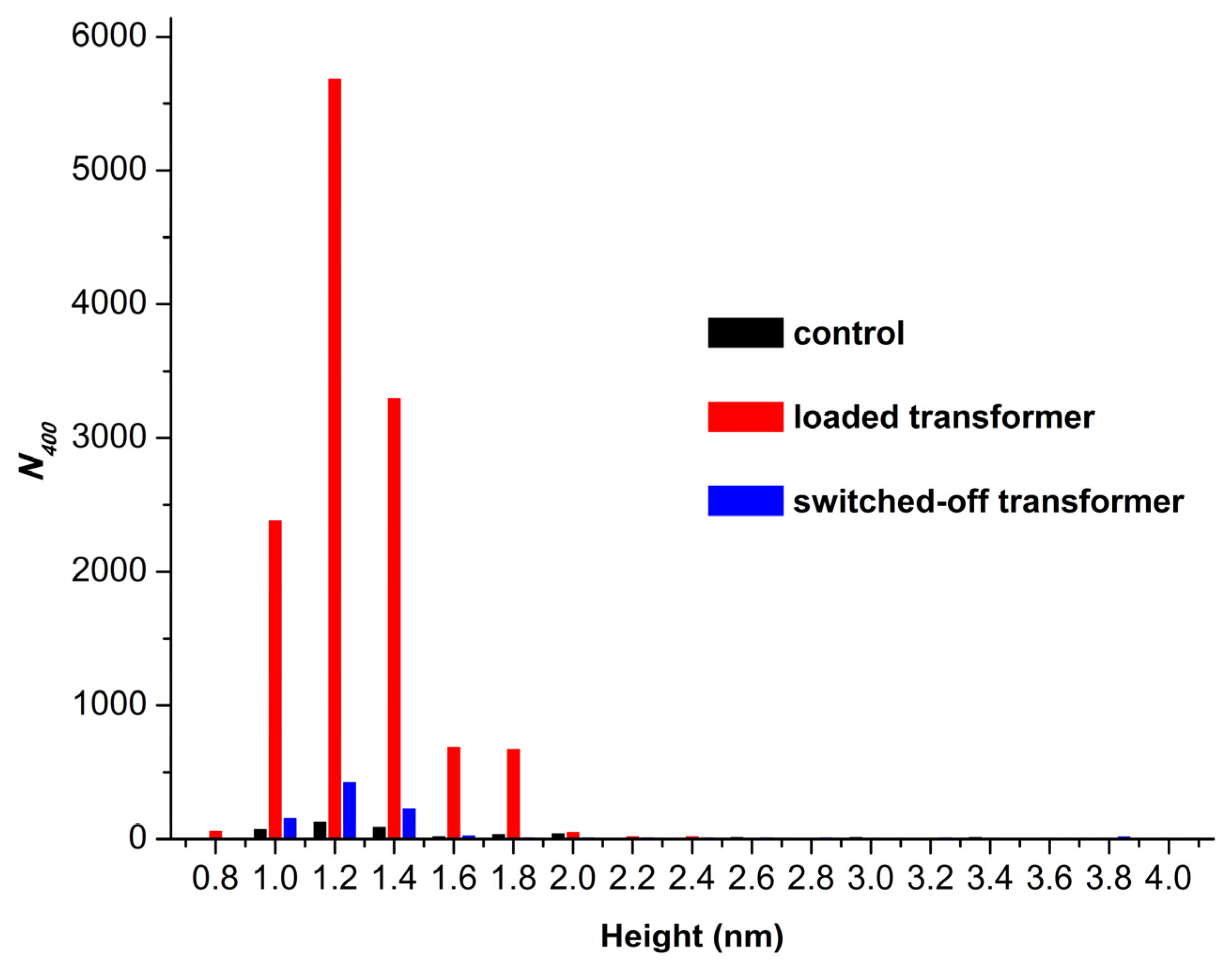

In addition, the absolute number of HRP particles, adsorbed on mica in our experiments, was considered.

Figure 4 displays histograms of absolute number of AFM-visualized particles, normalized per 400 µm

2, vs. height, obtained for the control and the working samples.

The histograms shown in

Figure 4 indicate that only 435 particles per 400 µm

2 adsorbed from the control enzyme sample. At the same time, from the working sample incubated near the loaded transformer, the number of adsorbed particles increased by two orders of magnitude to 12,858 objects per 400 μm

2. And when the enzyme solution was incubated near the switched-off transformer, the number of visualized objects was similar to that observed for the control sample, amounting to 895 particles per 400 µm

2.

Summarizing the results of our AFM experiments, we can conclude that half-hour-long incubation of HRP solution near loaded 50 Hz AC transformer promoted a disaggregation of the enzyme, accompanied by a great enhancement in its adsorption. At that, the incubation near the switched-off transformed resulted in a more considerable disaggregation of the enzyme, while its adsorption increased much less significantly.

3.2. Spectrophotometric Estimation of Enzymatic Activity

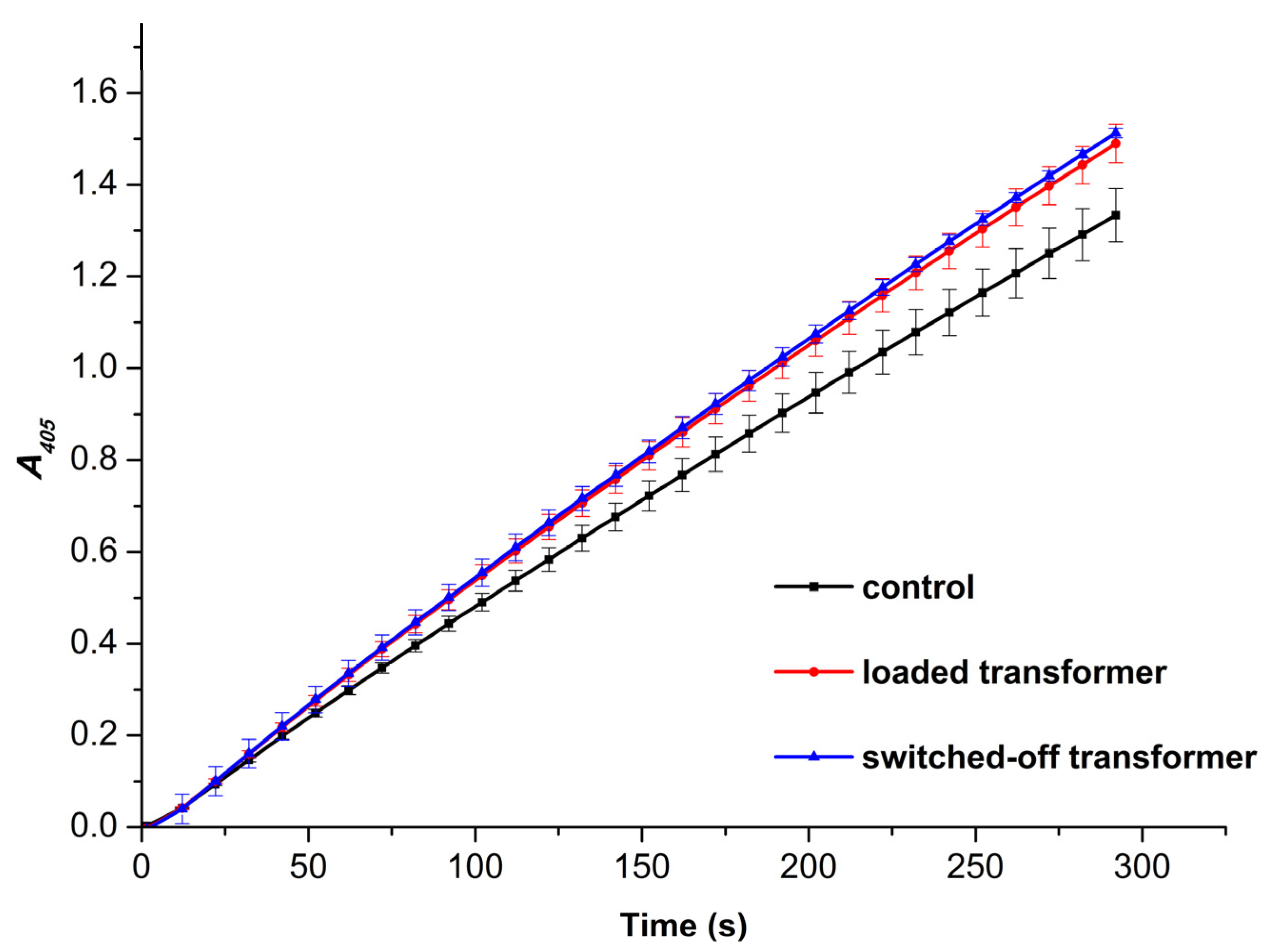

In parallel, the influence of incubation of HRP near a 50 Hz equipment on its enzymatic activity against ABTS was determined by spectrophotometry, as is briefly described in the Materials and Methods.

Figure 5 displays typical

A405(t) kinetic curves obtained for the control and the working samples studied by AFM.

The

A405(t) kinetic curves shown in

Figure 5 clearly indicate an increase in enzymatic activity of HRP against its substrate ABTS after the incubation of the enzyme solution above the transformer. It is quite interesting to note that there is no difference in the activity between the two working samples. That is, the incubation of the enzyme near either the loaded or the switched-off transformer led to the same increase in its activity. Namely, the enzymatic activity of HRP in the control sample amounted to 74.48±3.24 units/(mL enzyme). At that, the activity of the enzyme increased to 83.20±2.35 units/(mL enzyme) and 84.48±0.56 units/(mL enzyme) after the half-hour-long incubation near the loaded and switched-off transformer, respectively. In other words, the incubation of the enzyme near the loaded or the switched-off transformer resulted in a 12% and 13% increase in its activity, respectively.

4. Discussion

In this work, we have investigated how the incubation near 50 Hz AC energized equipment influences physicochemical properties of HRP enzyme. In our experiments, we have revealed that the half-hour-long incubation of 0.1 µM HRP solution at a 6 cm distance from the loaded transformer leads to a disaggregation of the enzyme. This disaggregation has been accompanied by both the enhancement in the number of adsorbed enzyme particles and a 12% increase in its activity against ABTS substrate. But there is another important phenomenon to be emphasized — namely, nearly complete disaggregation of the adsorbed enzyme (

Figure 3, blue curve vs. black curve) accompanied by 13% increase in activity (

Figure 5, blue curve vs. black curve).

In this connection, we should emphasize that exposure of HRP to electromagnetic or magnetic fields of either low (typically below 100 Hz [

2,

4,

5]) or radio [

23] frequency often causes a change in its enzymatic activity. The effect of these fields on the enzyme depends on the experimental conditions — namely, on the enzyme solution acidity [

2], the enzyme exposure time [

2,

5,

23], and the field parameters. The combination of these factors determines whether the enzymatic activity will be enhanced or suppressed by the field. In our case, half-hour-long exposure of 0.1 µM HRP solution in Dulbecco’s modified phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) resulted in 12-13% increase in the enzymatic activity against ABTS. Similar (by 5.33 to 13.73%) enhancement of HRP activity against guaiacol was reported by Yao et al. [

23] after 2.5 to 4.5-minute-long radio frequency heating of 0.1 mg/mL HRP solution to 50°C. At that, these authors observed a deactivation of the enzyme upon heating to higher (70°C and 90°C) temperatures, which was achieved by increasing the heating time [

23]. Wasak et al. [

2] reported that treatment of HRP in rotating magnetic field at pH 4.5 enhances its enzymatic activity at 1 Hz and 20 Hz field frequency, while at other frequencies studied (2 to 50 Hz, except 20 Hz), the enzymatic activity of HRP was suppressed. Caliga et al. [

4] and Portaccio et al. [5`] also reported a suppressing effect of 50 Hz electromagnetic field on HRP activity.

All the changes in adsorption, aggregation and catalytic properties of HRP under the influence of 50 Hz electromagnetic field can be explained by the re-distribution of the hydration shells of enzyme particles. Indeed, changes in enzyme hydration are known to be the cause of alterations in the enzymatic activity [

40,

41,

42]. Furthermore, there is no surprise that the disaggregation of the enzyme is accompanied by the increase in its catalytic activity: the enzyme aggregation is commonly ascribed to the loss of activity [

43,

44,

45], and we have observed the reverse process. The changes in the enzyme hydration also influence both the enzyme-enzyme [

46] and enzyme-(AFM substrate surface) [

47] interactions by changing the balance between electrostatic, van der Waals and hydration repulsion interactions [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. This is how we explain the phenomena observed in our experiments.

Once again, in this work, we have discovered that the properties of the enzyme are affected not only by the electromagnetic fields emitted by energized equipment (such as electric motors and loaded transformers), but even after the exposure of the enzyme to switched-off 50-Hz AC equipment. That is, the incubation near the 50 Hz AC equipment has been found to affect on both the adsorption/aggregation and the catalytic properties of the enzyme. In the situation with the loaded autotransformer, the increase in enzyme adsorption onto mica surface could be explained by the effect of 50 Hz electromagnetic field, which could cause a change in the enzyme hydration, leading to an increase in the adsorption properties of the enzyme to the mica surface. But when the autotransformer was switched off and disconnected from the mains power supply, incubation above the transformer’s coil resulted in even more significant decrease in the degree of enzyme aggregation was observed. Bunkin et al. [

53] ascribed the post-effect of low-frequency radiation in the aqueous medium to the formation of nanobubble clusters. This process was observed during electromagnetic excitation of the aqueous medium by an external electromagnetic field. Such a bubble formation was confirmed in other papers [

54,

55,

56].

5. Conclusions

Herein, by using atomic force microscopy (AFM) and spectrophotometry analysis performed in parallel, we have investigated how the incubation near 50 Hz AC equipment influences the physicochemical properties of horseradish peroxidase (HRP). We have found that half-hour-long incubation of the enzyme 6 cm above the coil of a loaded autotransformer promotes a disaggregation of HRP on mica with simultaneous enhancement of the number of mica-adsorbed enzyme particles by two orders of magnitude — as compared with the control sample. Density function plots obtained for both the control and the working sample of the enzyme incubated near the loaded autotransformer, have exhibited a bimodal character with two maxima. For the control sample, the maxima have been observed at hmax1 = 1.2 ± 0.2 nm, and at hmax2 = 2.0 nm ± 0.2 nm, while for the working sample the maxima have been observed at hmax1=1.2 ± 0.2 nm, and hmax2=1.8 ± 0.2 nm, respectively. At the same time, the ratio of peak intensities ρ(hmax2)/ρ(hmax1) decreased approximately twofold — as compared with that obtained for the control sample. Both the decrease in ρ(hmax2)/ρ(hmax1) ratio, and the shift of hmax2 by ~0.3 nm to the left observed for the working sample, clearly indicate a disaggregation of the enzyme after its half-hour-long incubation near the loaded 50 Hz AC autotransformer.

Most interestingly, the incubation of HRP above the switched-off transformer for the same period of time has been found to cause even more significant disaggregation of the enzyme! Namely, the density function plot obtained for this sample exhibited a unimodal character with a maximum at a height of hmax1 = 1.2 ± 0.2 nm, being devoid of the second maximum. The effect on the amount of mica-adsorbed enzyme particles was much less significant in the latter case. But at the same time, a 12 to 13% increase in the enzymatic activity of HRP has been observed in the both cases. Thus, the half-hour-long incubation of the enzyme near the autotransformer has had a clearly distinguishable long-term effect on both the adsorption. We hope that the effects reported in our manuscript will emphasize the importance of consideration of the influence of low-frequency electromagnetic fields on enzymes in the design of laboratory and industrial equipment intended for operation with enzyme systems. We believe that our results reported will be interesting to scientists studying enzyme systems, and to engineers developing the laboratory and industrial equipment, which is intended for operation with enzymes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yuri D. Ivanov and Vadim Yu. Tatur; Data curation, Angelina V. Vinogradova, Ekaterina D. Nevedrova, Nina D. Ivanova, and Ivan D. Shumov; Formal analysis, Ivan D. Shumov, Oleg N. Afonin, and Alexey N. Evdokimov; Investigation, Yuri D. Ivanov, Ivan D. Shumov, Alexander N. Ableev and Vadim S. Ziborov; Methodology, Yuri D. Ivanov and Vadim Yu. Tatur; Project administration, Yuri D. Ivanov; Resources, Vadim Yu. Tatur, Andrei A. Lukyanitsa and Vadim S. Ziborov; Software, Andrei A. Lukyanitsa; Supervision, Yuri D. Ivanov; Validation, Vadim S. Ziborov; Visualization, Ivan D. Shumov, Andrey F. Kozlov, and Ekaterina D. Nevedrova; Writing—original draft, Ivan D. Shumov, Angelina V. Vinogradova and Yuri D. Ivanov; Writing—review & editing, Yuri D. Ivanov.

Funding

The study was performed within the framework of the Program for Basic Research in the Russian Federation for a long-term period (2021–2030) (No. 122030100168-2).

Data Availability Statement

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Y.D.I.

Acknowledgments

The AFM measurements were performed employing a Titanium multimode atomic force microscope, which pertains to “Avogadro” large-scale research facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Claussnitzer, H.H. Einführung in die Elektrotechnik. 8. Auflage. VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin, 1982.

- Wasak, A.; Drozd, R.; Jankowiak, D.; Rakoczy, R. The influence of rotating magnetic field on bio-catalytic dye degradation using the horseradish peroxidase. Biochem. Eng. J. 2019, 147, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasak, A.; Drozd, R.; Jankowiak, D.; Rakoczy, R. Rotating magnetic field as tool for enhancing enzymes properties - laccase case study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caliga, R.; Maniu, C.L.; Mihăşan, M. ELF-EMF exposure decreases the peroxidase catalytic efficiency in vitro. Open Life Sci. 2016, 11, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portaccio, M.; De Luca, P.; Durante, D.; Rossi, S.; Bencivenga, U.; Canciglia, P.; Lepore, M.; Mattei, A.; De Maio, A.; Mita, D.G. In vitro studies of the influence of ELF electromagnetic fields on the activity of soluble and insoluble peroxidase. Bioelectromagnetics: Journal of the Bioelectromagnetics Society, The Society for Physical Regulation in Biology and Medicine, The European Bioelectromagnetics Association 2003, 24, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Sun, F.; Xu, B.; Gu, N. The quasi-one-dimensional assembly of horseradish peroxidase molecules in presence of the alternating magnetic field. Coll. Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2010, 360, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, H.; Jin, Y.; Wang, M.; Gu, N. Magnetically enhanced dielectrophoretic assembly of horseradish peroxidase molecules: Chaining and molecular monolayers. Chem. Phys. Chem. 2008, 9, 1847–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrkar, H.; Ebrahimi, S.; Zamani, M. A review of bioreactor technology used for enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulosic materials. Cellulose 2018, 25, 6279–6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Ramirez, N.; Volke-Sepulveda, T.; Gaime-Perraud, I.; Saucedo-Castañeda, G.; Favela-Torres, E. Effect of stirring on growth and cellulolytic enzymes production by Trichoderma harzianum in a novel bench-scale solid-state fermentation bioreactor. Bioresource Technol. 2018, 265, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, D.E. Biochemistry, the Chemical Reactions of Living Cells, 1st ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, UK, 1977.

- Emamdadi, N.; Gholizadeh, M.; Housaindokht, M.R. Investigation of static magnetic field effect on horseradish peroxidase enzyme activity and stability in enzymatic oxidation process. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 170, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, E.; Magazù, S. Electromagnetic Fields Effects on the Secondary Structure of Lysozyme and Bioprotective Effectiveness of Trehalose. Adv. Phys. Chem. 2012, 970369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, B.M.; McAnena, P.F.; Abd Elwahab, S.M.; Fasoula, A.; Duchesne, L.; Cano, J.D.G.; Glynn, C.; O’Connell, A.M.; Ennis, R.; Lowery, A.J.; et al. Microwave imaging in breast cancer–results from the first-in-human clinical investigation of the wavelia system. Acad. Radiol. 2022, 29 (Suppl. S1), S211–S222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vojisavljevic, V.; Pirogova, E.; Cosic, I. Influence of Electromagnetic Radiation on Enzyme Kinetics. 2007 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Lyon, France, 2007, pp. 5021–5024. [CrossRef]

- Jumaat, H.; Ping, K.H.; Abd Rahman, N.H.; Yon, H.; Redzwan, F.N.M.; Awang, R.A. A compact modified wideband antenna with CBCPW, stubline and notch-staircase for breast cancer microwave imaging application. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2021, 129, 153492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozhaev, V.V.; Heremans, K.; Frank, J.; Masson, P.; Balny, C. High Pressure Effects on Protein Structure and Function. PROTEINS. Struct. Funct. Genet. 1996, 24, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karam, S.A.S.; O’Loughlin, D.; Oliveira, B.L.; O’Halloran, M.; Asl, B.M. Weighted delay-and-sum beamformer for breast cancer detection using microwave imaging. Measurement 2021, 177, 109283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warille, A.A.; Altun, G.; Elamin, A.A.; Kaplan, A.A.; Mohamed, H.; Yurt, K.K.; Elhaj, A.E. Skeptical approaches concerning the effect of exposure to electromagnetic fields on brain hormones and enzyme activities. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2017, 5, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinoviev, S.V.; Evdokimov, A.N.; Sakharov, K.Y.; Turkin, V.A.; Aleshko, A.I.; Ivanov, A.V. Determination of therapeutic value of ultra-wideband pulsed electromagnetic microwave radiation on models of experimental oncology. Meditsinskaya Fiz. Med. Phys. 2015, 3, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, P.K. Enzymes: Principles and biotechnological applications. Essays Biochem. 2015, 59, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Hori, M.; Shizawa, N.; Nakayama, H.; Shinmyo, A.; Yoshida, K. High-efficiency secretory production of peroxidase C1a using vesicular transport engineering in transgenic tobacco. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2006, 102, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krainer, F.W.; Glieder, A. An updated view on horseradish peroxidases: Recombinant production and biotechnological applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 1611–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Pang, H.; Wang, Y.; Fu, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. The effect of radio frequency heating on the inactivation and structure of horseradish peroxidase. Food Chem. 2023, 398, 133875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoglu, G.; Arıca, M.Y. Enzymatic removal of phenol and p-chlorophenol in enzyme reactor: Horseradish peroxidase immobilized on magnetic beads. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 156, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanavicius, A.; Kausaite-Minkstimiene, A.; Morkvenaite-Vilkonciene, I.; Genys, P.; Mikhailova, R.; Semashko, T.; Voronovic, J.; Ramanaviciene, A. Biofuel cell based on glucose oxidase from Penicillium funiculosum 46.1 and horseradish peroxidase. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 264, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Tannia, D.C.; Kwon, Y. Glucose biofuel cells using bienzyme catalysts including glucose oxidase, horseradish peroxidase and terephthalaldehyde crosslinker. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreau, C.; Nedellec, Y.; Ondel, O.; Buret, F.; Cosnier, S.; Le Goff, A.; Holzinger, M. Glucose oxidase bioanodes for glucose conversion and H2O2 production for horseradish peroxidase biocathodes in a flow through glucose biofuel cell design. J. Power Sources 2018, 392, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, Y.D.; Pleshakova, T.O.; Shumov, I.D.; Kozlov, A.F.; Ivanova, I.A.; Valueva, A.A.; Tatur, V.Y.; Smelov, M.V.; Ivanova, N.D.; Ziborov, V.S. AFM imaging of protein aggregation in studying the impact of knotted electromagnetic field on a peroxidase. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, Y.D.; Tatur, V.Y.; Pleshakova, T.O.; Shumov, I.D.; Kozlov, A.F.; Valueva, A.A.; Ivanova, I.A.; Ershova, M.O.; Ivanova, N.D.; Repnikov, V.V.; et al. Effect of Spherical Elements of Biosensors and Bioreactors on the Physicochemical Properties of a Peroxidase Protein. Polymers 2021, 13, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, Y.D.; Shumov, I.D.; Kozlov, A.F.; Valueva, A.A.; Ershova, M.O.; Ivanova, I.A.; Ableev, A.N.; Tatur, V.Y.; Lukyanitsa, A.A.; Ivanova, N.D.; et al. Atomic Force Microscopy Study of the Long-Term Effect of the Glycerol Flow, Stopped in a Coiled Heat Exchanger, on Horseradish Peroxidase. Micromachines 2024, 15, Accepted for publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.F. Guide to cytochromes P450: Structure and function. CRC Press, 1996.

- Archakov, A.I.; Bachmanova, G.I. Cytochrome P450 and Active Oxygen; Taylor & Francis: New York, Philadelphia, 1990.

- Kiselyova, O.I.; Yaminsky, I.; Ivanov, Y.D.; Kanaeva, I.P.; Kuznetsov, V.Y.; Archakov, A.I. AFM study of membrane proteins, cytochrome P450 2B4, and NADPH–Cytochrome P450 reductase and their complex formation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 371, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleshakova, T.O.; Kaysheva, A.L.; Shumov, I.D.; Ziborov, V.S.; Bayzyanova, J.M.; Konev, V.A.; Uchaikin, V.F.; Archakov, A.I.; Ivanov, Y.D. Detection of hepatitis C virus core protein in serum using aptamer-functionalized AFM chips. Micromachines 2019, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, S.A.; Bray, R.C.; Smith, A.T. pH-dependent properties of a mutant horseradish peroxidase isoenzyme C in which Arg38 has been replaced with lysine. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994, 224, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozd, M.; Pietrzak, M.; Parzuchowski, P.G.; Malinowska, E. Pitfalls and capabilities of various hydrogen donors in evaluation of peroxidase-like activity of gold nanoparticles. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 8505–8513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, Y.D.; Tatur, V.Y.; Shumov, I.D.; Kozlov, A.F.; Valueva, A.A.; Ivanova, I.A.; Ershova, M.O.; Ivanova, N.D.; Stepanov, I.N.; Lukyanitsa, A.A.; et al. The Effect of a Dodecahedron-Shaped Structure on the Properties of an Enzyme. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, P.F.; Rennke, H.G.; Cotran, R.S. Influence of molecular charge upon the endocytosis and intracellular fate of peroxidase activity in cultured arterial endothelium. J. Cell Sci. 1981, 49, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welinder, K.G. Amino acid sequence studies of horseradish peroxidase. amino and carboxyl termini, cyanogen bromide and tryptic fragments, the complete sequence, and some structural characteristics of horseradish peroxidase C. Eur. J. Biochem. 1979, 96, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laage, D.; Elsaesser, T.; Hynes, J.T. Water Dynamics in the Hydration Shells of Biomolecules. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10694–10725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, A.C.; Laage, D. Water Dynamics in Protein Hydration Shells: The Molecular Origins of the Dynamical Perturbation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 7715–7729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.K.; Rakshit, S.; Mitra, R.K.; Pal, S.K. Role of hydration on the functionality of a proteolytic enzyme α-chymotrypsin under crowded environment. Biochimie 2011, 93, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bowman, J.; Tu, S.; Nykypanchuk, D.; Kuksenok, O.; Minko, S. Polyethylene glycol Crowder’s effect on enzyme aggregation, thermal stability, and residual catalytic activity. Langmuir 2021, 37, 8474–8485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, F.D.; Schroeder, K.; Jonas, K. Protein aggregation in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombie, S.; Gaunand, A.; Lindet, B. Lysozyme inactivation and aggregation in stirred-reactor. J. Mol. Catalysis B: Enzymatic 2001, 11, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitagliano, L.; Berisio, R.; De Simone, A. Role of Hydration in Collagen Recognition by Bacterial Adhesins. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaufils, C.; Man, H.-M.; de Poulpiquet, A.; Mazurenko, I.; Lojou, E. From Enzyme Stability to Enzymatic Bioelectrode Stabilization Processes. Catalysts 2021, 11, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, P.A.; Bera, B.; van den Berg, J.; Visser, I.; Kleijn, J.M.; Boom, R.M.; Schroën, C.G.P.H. Electrode Surface Potential-Driven Protein Adsorption and Desorption through Modulation of Electrostatic, van der Waals, and Hydration Interactions. Langmuir 2021, 37, 6549–6555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trefalt, G.; Szilagyi, I.; Borkovec, M. Poisson–Boltzmann description of interaction forces and aggregation rates involving charged colloidal particles in asymmetric electrolytes. J. Coll. Interface Sci. 2013, 406, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duinhoven, S.; Poort, R.; van der Voet, G.; Agterof, W.G.M.; Norde, W.; Lyklema, J. Driving forces of enzyme adsorption at solid-liquid interfaces. J. Coll. Interface Sci. 1995, 170, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, C.M.; Lenhoff, A.M. Electrostatic and van der Waals Contributions to Protein Adsorption: Computation of Equilibrium Constants. Langmuir 1993, 9, 962–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, C.M.; Lenhoff, A.M. Electrostatic and van der Waals Contributions to Protein Adsorption: Comparison of Theory and Experiment. Langmuir 1995, 11, 3500–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunkin, N.F.; Bolotskova, P.N.; Bondarchuk, E.V.; Gryaznov, V.G.; Gudkov, S.V.; Kozlov, V.A.; Okuneva, M.A.; Ovchinnikov, O.V.; Smoliy, O.P.; Turkanov, I.F. Long-Term Effect of Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Irradiation in Water and Isotonic Aqueous Solutions as Studied by Photoluminescence from Polymer Membrane. Polymers 2021, 13, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, S.O.; Shkirin, A.V.; Ninham, B.W.; Sychev, A.A.; Babenko, V.A.; Penkov, N.V.; Kryuchkov, N.P.; Bunkin, N.F. Ionspecific and thermal effects in the stabilization of the gas nanobubble phase in bulk aqueous electrolyte solutions. Langmuir 2016, 32, 11245–11255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunkin, N.F.; Shkirin, A.V.; Suyazov, N.V.; Babenko, V.A.; Sychev, A.A.; Penkov, N.V.; Belosludtsev, K.N.; Gudkov, S.V. Formation and dynamics of ion-stabilized gas nanobubbles in the bulk of aqueous NaCl solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunkin, N.F.; Bunkin, F.V. Bubston structure of water and electrolyte aqueous solutions. Physics-Uspekhi, 2016, 59, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).