Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

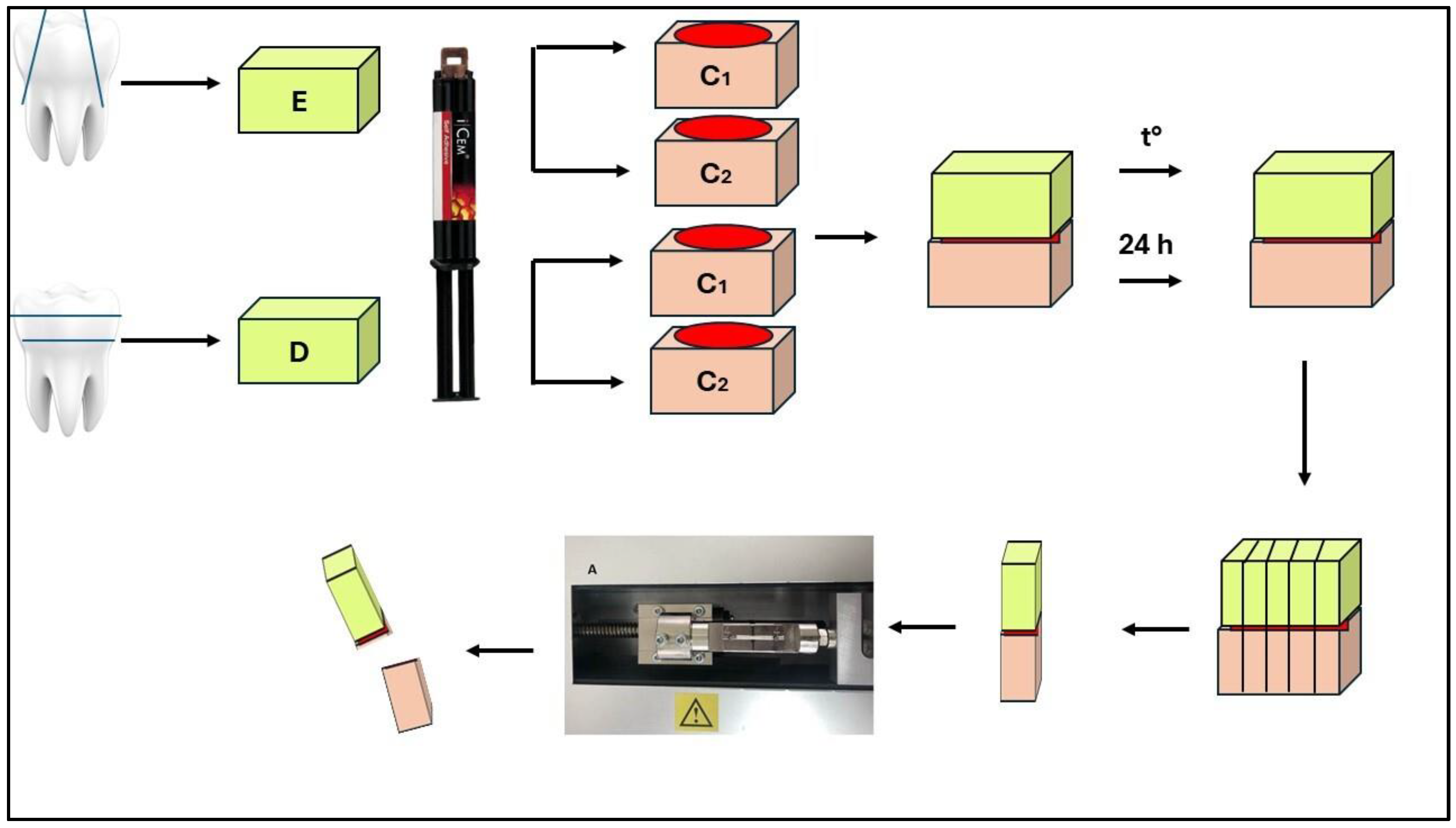

2.1. Fabrication of Composite Samples

2.2. Preparation of Enamel Specimens

2.3. Preparation of Dentin Specimens

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Thermal fatigue of the material leads to decreased micro-tensile bond strength values for all materials tested.

- Dentin bonds better to conventional laboratory composites.

- Enamel bonds are better than composite blocks for milling.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El-Askary, F.; Hassanein, A.; Aboalazm, E.; Al-Haj Husain, N.; Özcan, M. A Comparison of Microtensile Bond Strength, Film Thickness, and Microhardness of Photo-Polymerized Luting Composites. Materials 2022, 15, 3050. [CrossRef]

- Haruyama, A.; Muramatsu, T.; Kameyama, A. The Effect of Silane Treatment of a Resin-Based Composite on Its Microtensile Bond Strength to a Ceramic Restorative Material. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9178. [CrossRef]

- Cassin, A.M.; Pearson, G.J. Microleakage studies comparing a one-visit indirect composite inlay system and a direct composite restorative technique. J Oral Rehabil 1992 May; 19(3):265–270. [CrossRef]

- De Andrade, O.S.; de Goes, M.F.; Montes, M.A. Marginal adaptation and microtensile bond strength of composite indirect restorations bonded to dentin treated with adhesive and low-viscosity composite. Dent Mater 2007 Mar; 23(3):279–287.

- Kwon, H.J.; Ferrance, J.; Kang, K.; Dhont, J.; Lee, I.B. Spatio-temporal analysis of shrinkage vectors during photo-polymerization of composite. Dent Mater 2013; 29(12):1236-1243. [CrossRef]

- Boaro, L.C.; Goncalves, F.; Guimares, T.C.; Ferracane, J.L.; Pfeifer, C.S.; Braga, R.P. Sorption, solubility, shrinkage and mechanical properties of low-shrinkage commercial resin composites. Dent Mater 2013; 29(4):398-404.

- Lauvahutanon, S.; Takahashi, H.; Shiozawa, M.; Iwasiki, N.; Asahawa, Y.; Oki, M.; Finger, W.; Arksornnukit, M. Mechanical properties of composite resin blocks for CAD/CAM. Dent Mater 2014; 33(5): 705-710. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.F.; Migonney, V.; Ruse, N.D.; Sadoun, M. Resin composite blocks via high-pressure high-temperature polymerization.Dent Mater 2012; 28:529-534. [CrossRef]

- Mandikos, M.N.; McGivney, G.P.; Davis, E.; Bush, P.J; Carter, J.M. A comparison of the wear resistance and hardness of indirect composite resins. J Prost Dent 2001; 85(4):386-395. [CrossRef]

- Dikici, B.; Türke¸s Ba¸saran, E.; Can, E. Does the Type of Resin Luting Material Affect the Bonding of CAD/CAM Materials to Dentin? Dent. J. 2025, 13, 41.

- Miyazaki, T.; Hotta, Y.; Kunii, J.; Kuriyama, S.; Tamaki, Y. A review of dental CAD/CAM: current status and future perspectives from 20 years of experience. Dent Mater 2009; 28:44-56. [CrossRef]

- Boitile, P.; Mawusii, B.; Tapie, L.; Fromentin, O. A systematic review of CAD/CAM fit restoration evaluations. J Оral Rehabil 2014; 41:853-874. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, R. Materials for chairside CAD/CAM-produced restorations. J Am Dent Assoc 2006; 137:14S-21S. [CrossRef]

- ParadigmTM MZ100 Block: Technical Product Profile. St. Paul, MN: 3M ESPE; 2000. [CrossRef]

- Awada, A.; Nathanson, D. Mechanical properties of resin-ceramic CAD/CAM restorative materials. J Prosthet Dent 2015; 114: 587–593.

- Antoniou, I.; Mourouzis, P.; Dionysopoulos, D.; Pandoleon, P.; Tolidis, K. Influence of Immediate Dentin Sealing on Bond Strength of Resin-Based CAD/CAM Restoratives to Dentin: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 267. [CrossRef]

- Bellan, M.C.; Cunha, P.F.J.S.D.; Tavares, J.G.; Spohr, A.M.; Mota, E.G. Microtensile bond strength of CAD/CAM materials to dentin under different adhesive strategies. Braz Oral Res. 2017; 18(31): e109. [CrossRef]

- Kaptan, A.; Bektaş, O.; Eren, D.; Doğan, D. Influence of different surface sreatments to Self-adhesive resin cement to CAD-CAM materials bonding. ODOVTOS Int J Dental Sc 2023;25-1:22-32.

- Papadopoulos, K.; Pahinis, K.; Saltidou, K.; Dionysopoulos, D.; Tsitrou, E. Evaluation of the Surface Characteristics of Dental CAD/CAM Materials after Different Surface Treatments. Materials (Basel). 2020 Feb 22;13(4):981. [CrossRef]

- Manso, A.P.; Carvalho, R.M. Dental Cements for Luting and Bonding Restorations: Self-Adhesive Resin Cements. Dent Clin North Am. 2017 Oct; 61(4): 821–834.

- Wu, C.-Y.; Nakamura, K.; Miyashita-Kobayashi, A.; Haruyama, A.; Yokoi, Y.; Kuroiwa, A.; Yoshinari, N.; Kameyama, A. The Effect of Additional Silane Pre-Treatment on the Microtensile Bond Strength of Resin-Based Composite Post-andCore Build-Up Material. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6637. [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.M.; Alhalabi, F.; Alshehri, A.; Salem, M.A.; Robaian, A.; Alghannam, S.; Alayad, A.S.; Almutairi, B.; Alrahlah, A. Silane-Containing Universal Adhesives Influence Resin-Ceramic Microtensile Bond Strength. Coatings 2023, 13, 477. [CrossRef]

- Bracher, L.; Ozcan, M. Adhesion of resin composite to enamel and dentin: a methodological assessment. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2018;32:258–271. [CrossRef]

- Chin, A.; Ikeda, M.; Takagaki, T.; Nikaido, T.; Sadr, A.; Shimada, Y.; Tagami, J. Effects of Immediate and Delayed Cementations for CAD/CAM Resin Block after Alumina Air Abrasion on Adhesion to Newly Developed Resin Cement. Materials 2021, 14, 7058. [CrossRef]

- Gerdzhikov, I.; Uzunov, T.; Radeva, E. Evaluation of Microtensile Bond Strength of Luting Cements to Zirconia Ceramics. Wulfenia.2021, 28(12):2-11.

- Sano, H.; Chowdhury, A.F.M.A.; Saikaew, P.; Matsumoto, M.; Hoshika, S.; Yamauti, M. The microtensile bond strength test: Its historical background and application to bond testing. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2020 Dec;56(1):24-31. [CrossRef]

- Van Meerbeek, B.; Peumans, M.; Poitevin, A.; Mine, A.; Van Ende, A.; Neves, A.; De Munck, J. Relationship between bond-strength tests and clinical outcomes. Dent Mater. 2010 Feb;26(2):e100-21. [CrossRef]

- Griffith, A.A. The phenomena of rupture and flow in solids. Philos Trans R Soc London, Ser A. 1920;221:168–198.

- Armstrong, S.; Breschi, L.; Özcan, M.; Pfefferkorn, F.; Ferrari, M.; Van Meerbeek, B. Academy of Dental Materials guidance on in vitro testing of dental composite bonding effectiveness to dentin/enamel using micro-tensile bond strength (μTBS) approach. Dent Mater. 2017 Feb;33(2):133-143. [CrossRef]

- Gailani, H.F.A.; Benavides-Reyes, C.; Bolaños-Carmona, M.V.; Rosel-Gallardo, E.; González-Villafranca, P.; González-López, S. Effect of Two Immediate Dentin Sealing Approaches on Bond Strength of Lava™ CAD/CAM Indirect Restoration. Materials. 2021 Mar 26;14(7):1629.

- Magdy, N.; Rabah, A. Evaluation of micro-tensile bond strength of indirect resin composite inlay to dentin. Int J Health Sci Res. 2017; 7(5):105-115.

- Betamar, N.; Cardew, G.; van Noort, R. Influence of specimen designs on the microtensile bond strength to dentin. J Adhes Dent. 2007;9:159–168.

- De Munck, J.; Mine, A.; Poitevin, A.; Van Ende, A.; Cardoso, M.V.; Van Landuyt, K.L.; Peumans, M.; Van Meerbeek B. Meta-analytical review of parameters involved in dentin bonding. J Dent Res. 2012 Apr;91(4):351-7. [CrossRef]

- Goracci, C.; Cury, A.H.; Cantoro, A.; Papacchini, F.; Tay, F.R.; Ferrari, M. Microtensile bond strength and interfacial properties of self-etching and self-adhesive resin cements used to lute composite onlays under different seating forces. J Adhes Dent. 2006 Oct;8(5):327-35.

- De Angelis, F.; Minnoni, A.; Vitalone, L.M.; Carluccio, F.; Vadini, M.; Paolantonio, M.; D'Arcangelo, C. Bond strength evaluation of three self-adhesive luting systems used for cementing composite and porcelain. Oper Dent. 2011 Nov-Dec;36(6):626-34.

- Meredith, N.; Sherriff, M.; Setchell, D.J.; Swanson, S.A. Measurement of the microhardness and young's modulus of human enamel and dentine using an indentation technique. Arch Oral Biol. 1996;41:539–545. [CrossRef]

- De Munck, J.; Vargas, M.; Van Landuyt, K.; Hikita, K.; Lambrechts, P.; Van Meerbeek, B. Bonding of an auto-adhesive luting material to enamel and dentin. Dent Mater. 2004 Dec;20(10):963-71.

- Gamal, R.; Gomaa, Y.; Abdellatif, M. Microtensile bond strength and scanning electron microscopic evaluation of zirconia bonded to dentin using two self-adhesive resin cements; effect of airborne abrasion and aging. Fut Dent J 2017; 3(2):55-60. [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, S.S.; Cesar, P.F.; Swain, M.V. Direct comparison of the bond strength results of the different test methods: a critical literature review. Dent Mater. 2010;26:78–93. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.V.; Escribano, N.; Baracco, B.; Romero, M.; Ceballos, L. Effect of indirect composite treatment micro effect of indirect composite treatment microtensile bond strength of self-adhesive resin cements. J Clin Exp Dent 2015.

- Roperto, R.; Akkus, A.; Akkus, O.; Lang, L.; Sousa-Neto, M.D.; Teich, S.; Porto. T.S. Effect of different adhesive strategies on microtensile bond strength of computer aided design/computer aided manufacturing blocks bonded to dentin. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2016;13(2):117-123. [CrossRef]

- Türkmen, C.; Durkan, M.; Öksüz, M. Shear Bond Strength of Indirect Composites Luted with Three New Self-Adhesive Resin Cements to Dentin. J Adh 2009;85(12):919-931. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.F.; Ramos, C.M.; Francisconi, P.A.; Borges, A.F. The shear bond strength of self-adhesive resin cements to dentin and enamel: An in vitro study. J Prosthet Dent. 2015;113:220–7.

- Berkman, M.; Tuncer, S.; Tekçe, N.; Karabay, F.; Demirci, M. Microtensile bond strength between self-adhesive resin cements and resin based ceramic CAD/CAM block. Int. J Dental Sc 2020;23(1): 116-125. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, F.L.; Colucci, V.; Palma-Dibb, R.G.; Corona, S.A. Assessment of in vitro methods used to promote adhesive interface degradation: a critical review. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2007;19:340–354. [CrossRef]

- Abo-Hamar S.E.; Hiller, K.A.; Jung, H.; Federlin, M.; Friedl, K.H.; Schmalz, G. Bond strength of a new universal self-adhesive resin luting cement to dentin and enamel.Clin Oral Invest. 2005;9:161–167. [CrossRef]

| Group | Initial Mean ± SD (MPa) |

Agining Mean ± SD (MPa) |

Group | Initial Mean ± SD (MPa) |

Agining Mean ± SD (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/E | 12.22±2.12A, a | 8.53±1.93B, a | S/D | 18.65±3.98A, a | 16.96±3.66A, a |

| C/E | 14.58±3.37A, a | 10.60±2.17B, a | C/D | 12.08±2.53A, b | 6.17±1.28B, b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).