1. Introduction

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are frequent conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, characterized by recurring or chronic symptoms and that are not justified by structural or organic anomalies [1]. The so-called “functional symptoms” include abdominal pain and bloating, diarrhea, constipation, postprandial fullness, nausea, and vomit [2]. The most frequently encountered FGIDs are Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), functional bloating, functional constipation, functional diarrhea, and unspecified functional bowel disorder [2,3]. An epidemiological study conducted by Rome Foundation in 2021 estimates that around 40% of the global population suffers from FGID, with a prevalence of women presenting at least one FGID (49%) compared to men (37%) [4].

FGID are also defined as complex bi-directional disorders of the “Gut-Brain interaction”[5], as it has been demonstrated that visceral hypersensitivity, gastrointestinal motility anomaly, and psychological disturbances contribute to the pathogenesis. This bidirectional communication between the brain and the intestine is mediated by hormones, neurotransmitters, and bacterial metabolites [6]. It is not clear whether the psychological disturbances cause FGID or vice-versa, and independent epidemiological studies suggest that 50% of FGID cases starts with a psychological discomfort, followed by gastrointestinal disorders, while in the other 50% of the cases, the gastrointestinal symptoms appear earlier compared to the psychological disturbances [2].

IBS, which is characterized by abdominal pain, bloating, and changes in bowel habits that lack a known structural or anatomic explanation [7]. IBS, commonly attributed to gut-brain axis disfunction, is encountered in 9-23% of global population [7]. Women have a major probability compared to men to develop this syndrome, and the onset of symptoms may be related to age [8]. IBS etiology is not completely clear [9]. The potentially involved factors are genetic predisposition, altered intestinal motility due to altered serotonin blood concentrations, visceral hypersensitivity, psychological discomforts, enteric infection, intestinal dysbiosis, food intolerances, especially gluten, and altered intestinal permeability. IBS can be distinguished in four sub-types: IBS with constipation (IBS-C), IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with mixed symptoms (IBS-M), and IBS unsubtyped, without symptoms linked to stool consistency (IBS-U) [3,10]. About 1/3 of the patients with IBS presents the subtype IBS-C [9].

Functional abdominal bloating is another common FGID, and, by definition, it is a sensation of trapped gas at abdominal level that manifests as abdominal pressure, fullness sensation, and, in some patients, associated with objective abdominal distension [11]. Such conditions often coexist; however, some patients present only one of them [12]. Functional abdominal bloating is very common, and its prevalence varies between 16 and 31% with women generally presenting higher rates of bloating compared to men [12,13]. The prevalence of bloating in patients affected by FGID reaches 76% and many of them consider it the predominant and most annoying symptom [14]. It is thought that the physiopathology of abdominal bloating is associated with an excess of intestinal gas, which is due to either an increased gas production compared to the normal elimination mechanisms or to an alteration of the elimination mechanisms [11].

The unclear pathogenesis and the variability of the symptoms of IBS and of the FGID in general, make it challenging to achieve effective symptom control and satisfactory outcomes for patients. A standard therapy does not exist, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches can be considered, often tailored to the patient’s specific clinical history and symptom profile [15,16]. Pharmacological therapies typically aim to reduce pain and address specific symptoms, such as diarrhea or constipation, depending on the subtype of IBS. Commonly recommended medications include antispasmodic drugs for pain relief, Linaclotide for constipation-predominant IBS, osmotic laxatives, Rifaximin for bloating and gas, and Loperamide for diarrhea-predominant IBS-D [17]. Non-pharmacological therapies also play a significant role in IBS and FGID management. These can include psychological interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction, as stress and anxiety are known to exacerbate IBS symptoms. Additionally, physical activity and relaxation techniques, like yoga and meditation, may support symptom relief and improve over well-being [18]. A particularly effective non-pharmacological approach for many patients is dietary modification, especially a diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols commonly known as a low-FODMAP diet [19]. This diet reduces intake of certain carbohydrate that are poorly absorbed in the intestine and can lead to gas production, bloating, pain and other symptoms. A low-FODMAP diet is generally implemented in phases, beginning with an elimination phase to identify trigger foods, followed by a gradual reintroduction of foods to assess individual tolerance. While highly beneficial for many, this diet should ideally be conducted under the supervision of dietitian to ensure nutritional adequacy and to tailor the approach to individual needs [20].

Non-pharmacological therapies include diet intervention, medicinal herbs, probiotic, and digestive enzymes usage [21]. Recent research highlights the correlation between gut microbiota dysbiosis and IBS pathogenesis [22]. On this basis, several studies have demonstrated the potential contribution of probiotics as intervention method [23].

Supplementation with digestive enzymes can be another valid adjuvant therapy in several disorders of the of gastrointestinal tract such as in the cases of functional dyspepsia or IBS. Widely used in clinical practice, for patients with lactose intolerance, is the supplementation with lactase (or Beta-galactosidase), an enzyme that breaks down the disaccharide into the monosaccharides, glucose and galactose [24]. It has been studied also the potential role of enzyme α-galactosidase for the improvement of symptoms of IBS. This enzyme, produced by Aspergillus niger, digests some oligosaccharides, such as fructans and galactans at the small intestine level, avoiding that they reach the large intestine and become fermentation substrate of the bacteria inhabiting this tract [25]. Through this mechanism of action, α-galactosidase is possibly a valid therapy to reduce abdominal bloating in patients with IBS, however further studies are necessary to define the efficacy of such enzyme as therapy for patients with IBS [26].

Finally, another proposed non-pharmacological therapy includes the usage of medicinal plants, traditionally used and still under investigation for the prevention and treatment of many diseases. One of these is Melissa officinalis Lamiaceae (Melissa officinalis L.), which is known as medicinal plant for ca. 2000 years and its leaves contains several compounds that confer health benefits to the organism [27]. Among these there are flavonoids (quercitrin, rhamnocitrin, luteolin) and polyphenolic compounds (rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, and protocatechuic acid) that exert an antioxidant activity [28].

In this context, we presented a first pilot study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a die-tary supplement containing probiotics, Melissa officinalis extract, and digestive enzymes in reducing bloating and abdominal distension in individuals with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional abdominal bloating.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The design was a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled monocentric intervention study. Enrolled patients were volunteers suffering from IBS or functional abdominal bloating. The recruitment site was the Gastroenterology and Nutrition clinic of the Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico di Milano and the involved center was the Center for the Prevention and Diagnosis of Celiac Disease.

Given the aims and pilot nature of this study, the sample size was determined empirically based on a review of the available literature concerning the condition and the study product. Forty participants will be recruited (20 participants per treatment group).

The enrollment period was four months, between July and November 2023, and included 31 adult patients, which were randomized into two groups: 16 subjects were administered with Psyllogel Gonfiore (Giuliani SpA, Milan, Italy) (active product), while 15 subjects were administered with a placebo.

The evaluation of inclusion or exclusion criteria was performed during an outpatient visit with gastroenterologist or nutrition biologists. The main inclusion criteria were having an age between 18-65 years and suffering from IBS or functional bloating according to the Rome IV questionnaire criteria [5]. The main exclusion criteria were pregnancy or breastfeeding, subjects assuming other dietary supplements or pharmacological therapies for abdominal bloating.

The enrolled subjects followed two visits, a baseline visit (T0), where the enrolled patients signed an informed consent, and their clinical history was taken with the aim of collecting data about other pathology or concomitant pharmacological therapies. In addition, demographics and common variable data were collected and registered on Case Report Form (CRF). Randomization was assigned and the product was given to the subject. Moreover, during the visit subjects were asked to fill in the VAS, SF-36 and SCL-90 questionnaires, for the investigation of gastrointestinal symptomatology, quality of life and mental health, respectively. After 20 days of treatment with the supplement or the placebo, the final visit (T1) was performed. During this visit, all the precedent explained procedures were repeated with the aim of collecting data of the patient after the treatment period. All study participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico di Milano. Trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier: GIU-PSY-0322.

2.2. Product in Use

The active supplement is a 3g product containing: Bifidobacterium lactis SD5219 (BL-04) (1*109 CFU), Lactobacillus acidophilus SD5221 (NCFM) (1*109 CFU), dry extract of Melissa Officinalis L. (4% rosmarinic acid), lactase, α-galactosidase. The product should be assumed before the main meal, dissolved in 75 mL of water. The placebo did not include the probiotic strains, enzymes and botanical extract but included additional microcrystalline cellulose and was otherwise identical to the test capsules.

2.3. Questionnaires

A validated Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) [29], was used to evaluate the satisfaction level of the patient regarding his general health state, and to the severity of the specific gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, postprandial fullness, early feeling of satiety, gastric burn, stool consistency) and the general wellbeing perception. The patient is asked to indicate the severity of the symptoms on a 10 cm line, which endpoints are 0 (no symptom) and 10 (maximum severity). A variation greater than or equal to 3 cm between pre (T0) and post-intervention (T1) will be considered significant, according to Salerno Guideline [30].

The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) is designed for clinical practice and for research [31]. It consists of 36 multiple choices questions, to each answer a score is assigned. The questions aim at investigating how much the physical and metal healthy states influence the daily activity and the emotions.

The Symptom CheckList-90 questionnaire (SCL-90) aim is to examine mental health, and it is the most used questionnaire in the clinical field [32]. Ninety multiple choices questions, with a score zero to four, that look into the psychological sphere (obsessive-compulsive behavior, anxiety, depression, fear, sleeping disorders, interpersonal sensitivity).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Collected data of the populations object of this study were analyzed with the statistics software SAS (SAS, version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

“Chi-square test” was used to compare the subjects that reported a positive variation in the VAS Scale, in the two treatment groups, while “Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test” was utilized to analyze the variation of values on the VAS 0-10 cm scale, relative to the gastrointestinal and the non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms in the two treatment groups. The variations of the total score values relative to the SF36 and SCL-90 questionnaires of the two groups were compared with “Student’s t-test”.

For the tolerability analysis, all the patients treated with at least one dose of the product. Adverse events were registered with MedDRA 5.1 (System Organ Class/SOC e Preferred Term/PT) code. Adverse events and number of subjects with adverse events were resumed in frequency tables for the two treatment groups.

Statistical significance of the results was declared considering a first type error (α-error) equal to 0,05, two tails.

3. Results

3.1. Subjects’ Demographics

In this study 31 subjects were enrolled; among these subjects, 29 concluded the trial, while two of them were excluded because they did not participate in the final visit. Through randomization, the subjects were divided into two groups, 15 subjects were given the active product, while 14 subjects were given the placebo. The 79,3% of the patients were women (n=23) and only the 20,7% were men (n=6), and their age ranged from 24 to 64 years. As shown in

Table 1, the active group was composed by 73,3% of women and 26,7% of men. The placebo group was instead composed by 85,7% of women and 14,3% of men.

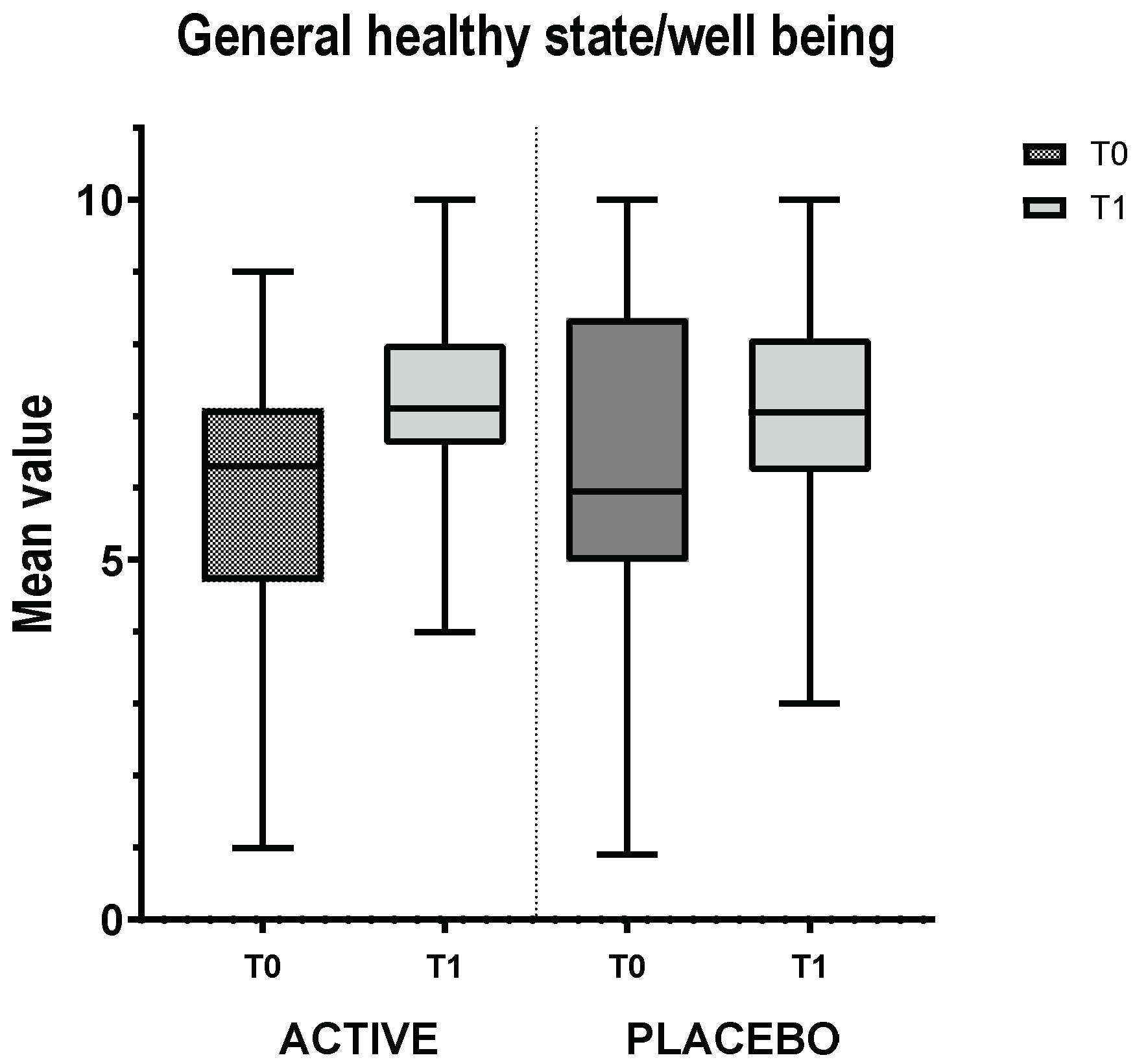

3.2. Global VAS

Subjects participating in the trial had to complete the global VAS scale, relative to the general satisfaction on the health state/wellbeing. The scale (in cm) goes from 0 to 10, where 0 means completely unsatisfied and 10 completely satisfied.

Table 2 resumes the results relative to the evaluation, through VAS, of general wellbeing at time 0 and time 1. The mean variation from final to basal visit, in the group treated with the active product showed an improvement of 1.51 cm (SD=2.49); while in the group treated with the placebo, there was a decrease of -0.58 cm (SD=3.14). While the p-value was slightly above the conventional threshold (p =<0.05), the observed effect size was clinically meaningful, suggesting a potential benefit of the ACTIVE group. (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test: p=0.052).

In particular, the treatment (ACTIVE) resulted in a significant improvement, with 26.83% improvement in general healthy state/well being compared to the control group (-8.40%).

Figure 1.

General healthy state/well-being VAS. The bar chart shows the mean value and the standard deviation of the VAS for the active group and the placebo group at T0 (basal visit) and T1 (final visit). In addition, it is shown the variation from T0 to T1 of the mean values.

Figure 1.

General healthy state/well-being VAS. The bar chart shows the mean value and the standard deviation of the VAS for the active group and the placebo group at T0 (basal visit) and T1 (final visit). In addition, it is shown the variation from T0 to T1 of the mean values.

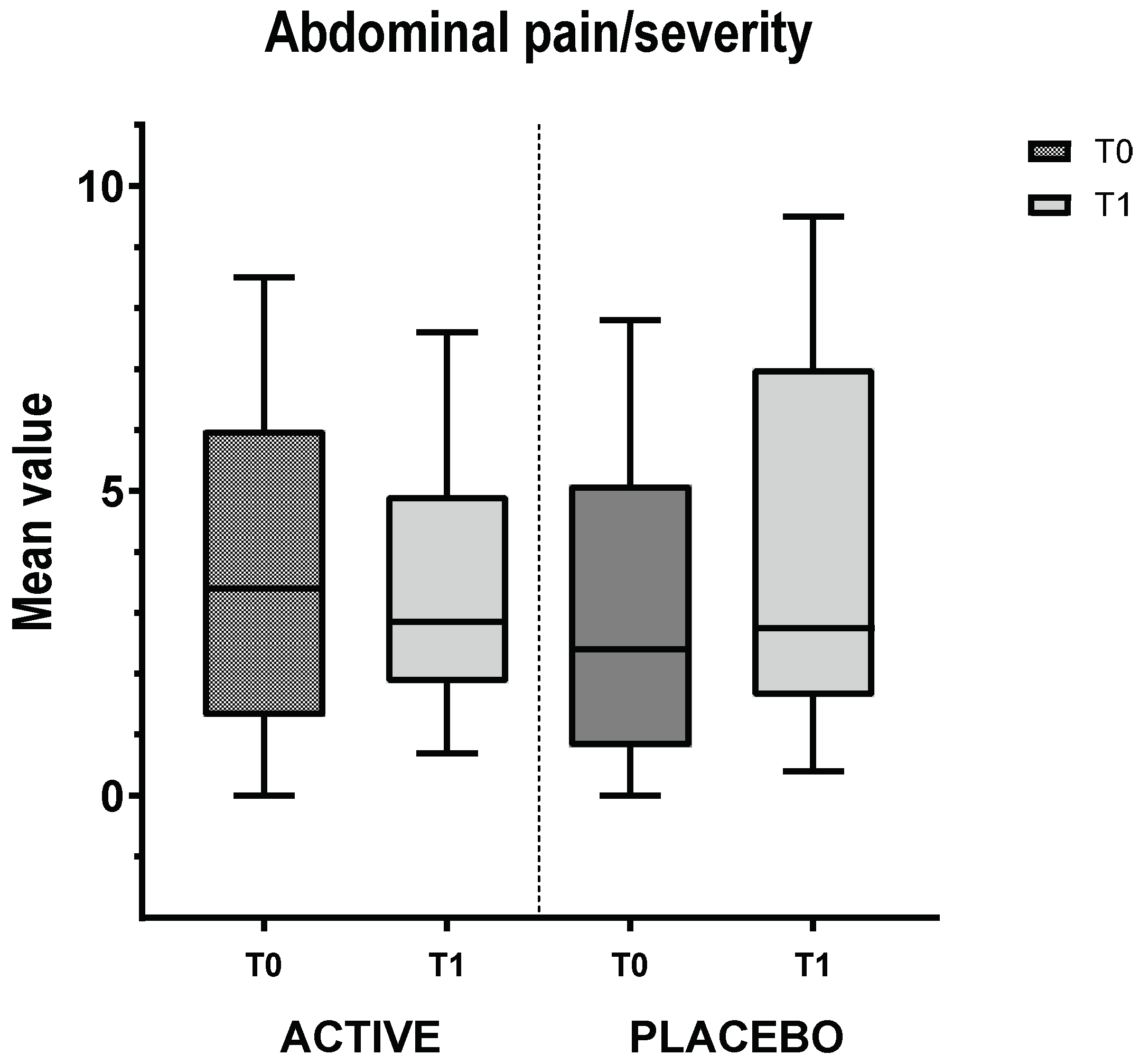

3.3. IBS Group VAS

In addition to general VAS, the enrolled subjects have filled in VAS relative to the symptoms related to IBS. Only the abdominal pain and severity of abdominal bloating were considered relevant according to the aim of the present study and dietary supplement functional rationale. The results are summed up in Figure 2. Even though the statistical analysis performed on the VAS variation (T0 vs T1) in abdominal pain (

Figure 2a) and severity of abdominal bloating (

Figure 2b), did not show any significant differences between the two treatment groups (Wilcoxon Rank-Sums test: p=0.345 and p=0.390, respectively), a clinically evident trend towards a reduction in abdominal pain group (-20.07% of reduction vs +16.69% in placebo group) and severity of abdominal bloating (-28.95% of reduction vs -21.86% in placebo group) suggests a potential therapeutic benefit for the active group.

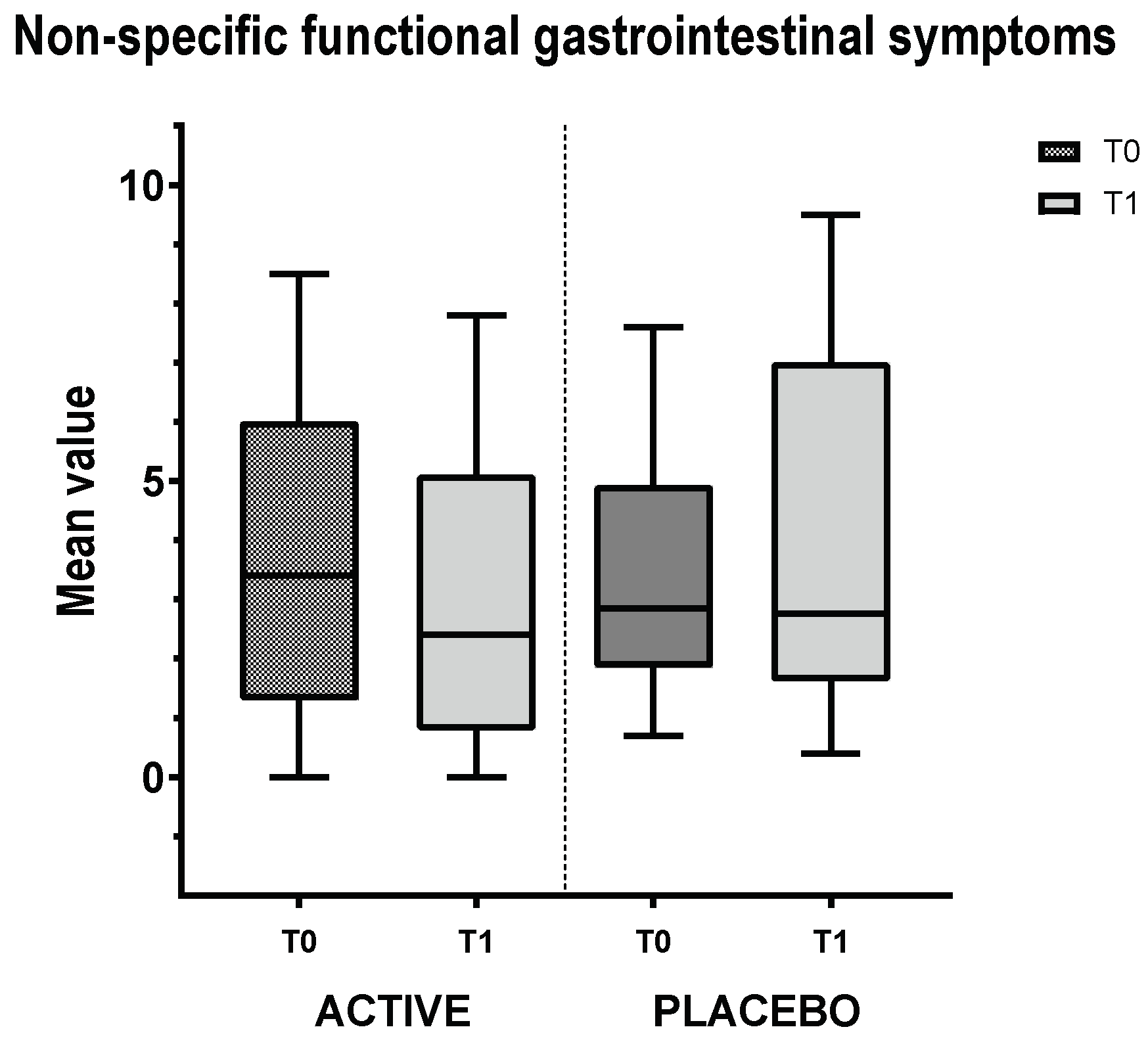

3.5. Non-Specific Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms Group VAS

In this VAS, patients had to consider their prevalent gastrointestinal symptom and indicate the severity from 0 to 10 (in cm). The graph (Figure 3) reveals that in both cases there was an improvement in the prevalent symptom, without any statistically significant difference between the two groups (-2.17 ± 3.20 vs -1.71 ± 1.57; Wilcoxon Rank-Sums test: p=0.863). Therefore, the treatment resulted in a higher tendency to improvement in patient-reported outcomes compared to the placebo group (30.61% vs 23.30%, respectively).

3.6. SF-36 Questionnaire

The SF-36 questionnaire serves to investigate the quality of life of the subjects before and after the treatment with the product. The mean variation of the total score of final compared to baseline visit resulted to be limited in both groups, 1.67 ± 3.66 for the active group and -0.14 ± 7.04 for the placebo group (

Table 3), without any statistically significant difference. The subcategories of the questionnaire investigated physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health or emotional issues, pain, general health status and general health status compared to the previous year. Also in these latter cases, no significancy was found in the statistical analysis (data not shown).

3.7. SCL-90 Questionnaire

The mental health of the subjects involved in this study was evaluated through the SCL-90 questionnaire. Table 4 reports the data relative to the total score, which decreased in both groups of the study, but without significancy.

The subcategories of the questionnaire regarded: somatization, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensibility, depression, anxiety, hostility, paranoid ideation, psychoticism, and sleep disturbances. Also in these specific cases, no statistically significant differences were found between variation from placebo to active group (data not shown).

4. Discussion

IBS and functional abdominal bloating are among the most common functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID), in fact, it is estimated that 9-30% of the global population suffers from these disorders [7,12]. Very often IBS and abdominal bloating are diagnosed by exclusion, since clinical investigations exclude the presence of structural or organic alterations, that justify the symptoms. Abdominal pain and bloating, diarrhea, constipation, postprandial fullness, nausea, and vomit are among the common symptoms of FGIDs; they can be from moderate to severe and have a great impact on the quality of life of the patient [2].

There seems to be an association between disturbances at psychological level and FGIDs. Recent research has deeply investigated the Gut-Brain axis and related disorders [33,34]. It has been demonstrated that signals and metabolites coming from the intestine can influence cerebral activity, while the input coming from the nervous system to the intestine can modulate several functions such as motility, sensibility, permeability of the intestine, but also the immune system functions and microbiota composition [35]. In this view, it is not totally clear whether psychological disorders cause FGIDs or vice versa, but we can speculate that the disorders can originate from both starting points.

Available scientific literature shows that several possibilities exist to treat the FGID, with diet being a key factor in the management of the syndrome [36].

Nevertheless, non-dietetic interventions can also be useful for helping the resolution of such disorders or for allaying the symptoms. Among these, probiotic usage is a promising strategy. These are defined by FAO and WHO as “live micro-organisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”. A dysbiotic condition is often encountered in patients with FGID [37] and the microbiota of patients with IBS shows a decrease in the Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium genera [38,39]. Several studies have demonstrated that supplementation with probiotics belonging to Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus genera, administered for up to eight weeks, improve IBS symptoms and the quality of life of the patients [40,41]. Although further research is needed to understand their mechanisms of actions in IBS, probiotics are widely recognized for their multi-level actions [42]. They can decrease visceral hypersensitivity, reduce mucosal inflammation, improve bloating sensation, and restore intestinal barrier integrity at tight junction level [43]. Additionally, probiotics contribute by competitively excluding pathogens, producing active, beneficial molecules, and regulating immune response [44].

Digestive enzyme supplementation can also be an adjuvant therapy in several disorders involving an alteration of digestive functions [45], but research on their specific usage in IBS suffering patients is scarce. Moreover, the usage of medicinal plants can help improve the symptoms associated to FGID too, as they act at the intestinal motility level, on abdominal bloating and on digestive functions thank to their natural bioactive components. It is widely known that lemon balm has mild sedative and carminative, spasmolytic effects and in traditional medicine, it is used also for lower abdominal disorders and nervous gastric complaints [27]. Vejdani et al. 2006 [46] have shown that Melissa officinalis, together with other medical plants, improves symptoms associated with IBS, especially severity of pain and abdominal bloating. However, the evidences that lemon balm is effective for IBS symptoms relief are limited.

In this study, 31 subjects suffering from IBS or functional abdominal bloating were enrolled in a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study with the product Psyllogel Gonfiore, a commercially available food supplement containing probiotics, lactase, α-galactosidase and Melissa officinalis L. extract. Twenty-nine subjects concluded the study, among which 23 were women and only six were men, reflecting the prevalence of FGID in women, as reported in literature. Through randomization, 15 patients were given the food supplement, while the remaining 14 patients were given the placebo.

The main objective of this pilot study was to evaluate the efficacy of the product through the global VAS evaluation of the degree of satisfaction and on the general wellbeing. Partecipants in the active group experienced a 26.83% increase in satisfaction compared to a -8.40% decrease in the placebo group. The statistical difference between the two groups narrowly issed significance (p-value = 0.052), this likely due to the limited number of subjects enrolled but, most important, to the multifactorial nature of IBS, a condition influenced by a complex interplay of physiological, psychological, and lifestyle factors. While Psyllogel Gonfiore clearly improved symptoms, achieving complete symptom resolution often requires a multimodal approach, including complementary strategies such as following an appropriate dietary regimen, like a low-FODMAP diet, and addressing factors like stress management and regular physical activity.

Despite these considerations, the findings of this pilot study highlight the efficacy of Psyllogel Gonfiore in improving key IBS symptoms, particularly general wellbeing and postprandial fullness, positioning it as a valuable option for managing this complex condition and suggesting the need of larger studies employing a multidisciplinary approach that considers the multifactorial nature of the condition.

Secondarily, the study aimed at investigating, through VAS, how gastrointestinal symptomatology could vary after the consumption of the active food supplement. The presence of digestive enzymes such as lactase and α-galactosidase likely enhances digestive efficiency, alleviating symptoms like postprandial fullness and gastric discomfort, ,typical symptoms of functional dyspepsia (criteri di Roma IV). This targeted gastric action provides rapid relief, particularly for immediate postprandial complaints, explaining the positive perception of symptom improvement reported by participants.

Abdominal pain and abdominal bloating had an improvement in the active group (-20.07% and -28.95%, resepctively), while they got worse in the group treated with placebo (+16.69% and -21.86%, respectively). Despite the improvements of these symptoms, the difference was not statistically significant, this could be due to the fact that the severity of abdominal pain was already quite low at the initial visit (3.82 for the active group and 3.34 in the placebo group) therefore the range of action was limited. Therefore, data suggested a positive tendency for the active group to reduce the severity of abdominal pain.

As regards, abdominal bloating it has to be considered that the digestive enzymes had an effect only at gastric level and not at the intestine level. This symptom may be probably better mitigated with a longer treatment period, in fact usually abdominal bloating has not a quick resolution time and a longer treatment period would allow a better colonization of the intestinal tract by the probiotic bacteria. Positive results on pain and bloating were obtained by administration of probiotics in IBS patients [47]. Clinical practice has shown that the treatment period can be prolonged to two months [41], instead of the 20 days of the study. Also as regards non-specific functional gastrointestinal symptoms, the treatment resulted in a higher tendency to improvement in patient-reported outcomes compared to the placebo group (30.61% vs 23.30%, respectively).

Since IBS and functional abdominal bloating have both an impact on life quality and mental wellbeing, among the secondary objectives of this study, there was also the evaluation of these factors. It has been observed through the SF-36 questionnaire that quality of life of the group treated with the active product improved by 1.67 points, while in the placebo group limited variation were observed. SCL-90 questionnaire on mental wellbeing revealed that in both groups there was an improvement, even if the statistical analysis did not show any significancy.

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first pilot study that investigates the effects of a simultaneous administration of probiotics, digestive enzymes and botanical extracts on patients suffering functional gastrointestinal disorders. Here we show that the supplement Psyllogel gonfiore could be a promising therapy in the treatment of the symptoms related to IBS and functional abdominal bloating, since there was a global improvement of general healthy state, abdominal pain and bloating; therefore, here we demonstrate that a non-dietetic and non-pharmacological intervention could be valid help in the therapies for functional gastro-intestinal disorders. For almost all the symptoms, a general improvement was observed, even if not with statistical significance, but a tendency to a clinical improvement was reported for all endpoints analyzed. As already mentioned, this could be due to the sample dimension but especially to the multifactorial nature of the IBS condition which requires a more complex approach also including diet intervention and psychological support. In addition, extending the treatment duration to two months, may allow an efficient colonization of the intestine by the probiotics and their beneficial effects could be observed also in the lower gastro-intestinal tract.

Author Contributions

D.P., L.R., L.E. conceptualized the study. A.S. and L.R. contributed to methodology. V.L., A.F., D.P. and G.M. worked on the formal analysis. R.M. carried out the investigation. G.M. and D.P. wrote the original draft. B.R., R.M., A.C., D.P. and F.R. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by GIULIANI SPA.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

G.M. and D.P. are employed by Giuliani S.p.A., F.R. serves as a consultant for Giuliani S.p.A.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFR |

Case Report Form |

| FGID |

Functional Gastrointestinal disorder |

| IBS |

Irritable Bowel Syndrome |

| IBS-C |

IBS with constipation |

| IBS-D |

IBS with diarrhea |

| IBS-M |

IBS with mixed symptoms |

| IBS-U |

IBS unsubtyped |

| SCL-90 |

Symptom Checklist-90 |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SF-36 |

Short Form Healthy Survey |

| VAS |

Visual Analogue Scale |

References

- Alonso-Bermejo C, Barrio J, Fernández B, García-Ochoa E, Santos A, Herreros M, Pérez C. Functional gastrointestinal disorders frequency by Rome IV criteria. Anales de Pediatría (English Edition). 2022;96(5):441–7.

- Black CJ, Drossman DA, Talley NJ, Ruddy J, Ford AC. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: advances in understanding and management. The Lancet. 2020;396(10263):1664–74.

- Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1480–91.

- Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, Ghoshal UC, Simren M, Tack J, Whitehead WE, Dumitrascu DL, Fang X, Fukudo S, Kellow J, Okeke E, Quigley EMM, Schmulson M, Whorwell P, Archampong T, Adibi P, Andresen V, Benninga MA, Bonaz B, Bor S, Fernandez LB, Choi SC, Corazziari ES, Francisconi C, Hani A, Lazebnik L, Lee YY, Mulak A, Rahman MM, Santos J, Setshedi M, Syam AF, Vanner S, Wong RK, Lopez-Colombo A, Costa V, Dickman R, Kanazawa M, Keshteli AH, Khatun R, Maleki I, Poitras P, Pratap N, Stefanyuk O, Thomson S, Zeevenhooven J, Palsson OS. Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(1):99-114.e3.

- Drossman DA, Hasler WL. Rome IV—Functional GI Disorders: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1257–61.

- Kasarello K, Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska A, Czarzasta K. Communication of gut microbiota and brain via immune and neuroendocrine signaling. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1118529.

- Radovanovic-Dinic B, Tesic-Rajkovic S, Grgov S, Petrovic G, Zivkovic V. Irritable bowel syndrome - from etiopathogenesis to therapy. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2018;162(1):1–9.

- Saha L. Irritable bowel syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and evidence-based medicine. WJG. 2014;20(22):6759–73.

- Shang X, E FF, Guo KL, Li YF, Zhao HL, Wang Y, Chen N, Nian T, Yang CQ, Yang KH, Li XX. Effectiveness and Safety of Probiotics for Patients with Constipation-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 10 Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients. 2022;14(12):2482.

- Camilleri M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325(9):865–77.

- Serra J. Management of bloating. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2022;34(3):e14333.

- Lacy BE, Cangemi D, Vazquez-Roque M. Management of Chronic Abdominal Distension and Bloating. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2021;19(2):219-231.e1.

- Jiang X, G R Locke III, Choung RS, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, Talley NJ. Prevalence and risk factors for abdominal bloating and visible distention: A population-based study. Gut. 2008;57(6):756.

- Chang L, Lee OY, Naliboff B, Schmulson M, Mayer EA. Sensation of bloating and visible abdominal distension in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(12):3341–7.

- Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015;313(9):949–58.

- Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1393-1407.e5.

- Chang L, Lembo A, Sultan S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(5):1149-1172.e2.

- Eriksson EM, Andrén KI, Kurlberg GK, Eriksson HT. Aspects of the non-pharmacological treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. WJG. 2015;21(40):11439–49.

- Halland M, Saito YA. Irritable bowel syndrome: new and emerging treatments. BMJ. 2015;350:h1622.

- Jent S, Bez NS, Haddad J, Catalano L, Egger KS, Raia M, Tedde GS, Rogler G. The efficacy and real-world effectiveness of a diet low in fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides and polyols in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Nutrition. 2024;43(6):1551–62.

- Galica AN, Galica R, Dumitrașcu DL. Diet, fibers, and probiotics for irritable bowel syndrome. JMedLife. 2022;15(2):174–9.

- Napolitano M, Fasulo E, Ungaro F, Massimino L, Sinagra E, Danese S, Mandarino FV. Gut Dysbiosis in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Narrative Review on Correlation with Disease Subtypes and Novel Therapeutic Implications. Microorganisms. 2023;11(10):2369.

- Zhang T, Zhang C, Zhang J, Sun F, Duan L. Efficacy of Probiotics for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022.

- Catanzaro R, Sciuto M, Marotta F. Lactose intolerance: An update on its pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Nutrition Research. 2021;89:23–34.

- Böhn L, Törnblom H, Van Oudenhove L, Simrén M, Störsrud S. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover pilot study: Acute effects of the enzyme α-galactosidase on gastrointestinal symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(7):e14094.

- de Vrese M, Laue C, Offick B, Soeth E, Repenning F, Thoß A, Schrezenmeir J. A combination of acid lactase from Aspergillus oryzae and yogurt bacteria improves lactose digestion in lactose maldigesters synergistically: A randomized, controlled, double-blind cross-over trial. Clin Nutr. 2015;34(3):394–9.

- Zam W, Quispe C, Sharifi-Rad J, López MD, Schoebitz M, Martorell M, Sharopov F, Fokou PVT, Mishra AP, Chandran D, Kumar M, Chen JT, Pezzani R. An Updated Review on The Properties of Melissa officinalis L.: Not Exclusively Anti-anxiety. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2022;14(2):16.

- Miraj S, Rafieian-Kopaei, Kiani S. Melissa officinalis L: A Review Study With an Antioxidant Prospective. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2017;22(3):385–94.

- Roncoroni L, Bascuñán KA, Doneda L, et al. Correction: Roncoroni, L. et al. A Low FODMAP Gluten-Free Diet Improves Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders and Overall Mental Health of Celiac Disease Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1023. Nutrients. 2019;11(3):566.

- Catassi, C.; Elli, L.; Bonaz, B.; Bouma, G.; Carroccio, A.; Castillejo, G.; Cellier, C.; Cristofori, F.; de Magistris, L.; Dolinsek, J.; et al. Diagnosis of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS): The Salerno Experts’ Criteria. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4966–4977.

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83.

- Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH. Dimensions of outpatient neurotic pathology: Comparison of a clinical versus an empirical assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1970;34(2):164–71.

- Mayer EA, Nance K, Chen S. The Gut-Brain Axis. Annu Rev Med. 2022;73:439–53.

- Wang Q, Yang Q, Liu X. The microbiota–gut–brain axis and neurodevelopmental disorders. Protein & Cell. 2023;14(10):762–75.

- Satish Kumar L, Pugalenthi LS, Ahmad M, Reddy S, Barkhane Z, Elmadi J. Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Review of Their Therapeutic Role. Cureus. 2022;14(4):e24240.

- Cozma-Petruţ A, Loghin F, Miere D, Dumitraşcu DL. Diet in irritable bowel syndrome: What to recommend, not what to forbid to patients! WJG. 2017;23(21):3771.

- Zhuang X, Xiong L, Li L, Li M, Chen M. Alterations of gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J of Gastro and Hepatol. 2017;32(1):28–38.

- Kerckhoffs AP, Samsom M, Rest MEVD, Vogel JD, Knol J, Ben-Amor K, Akkermans LM. Lower Bifidobacteria counts in both duodenal mucosa-associated and fecal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients. WJG. 2009;15(23):2887.

- Malinen E, Rinttilä T, Kajander K, Mättö J, Kassinen A, Krogius L, Saarela M, Korpela R, Palva A. Analysis of the fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy controls with real-time PCR. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(2):373–82.

- O’Mahony L, McCarthy J, Kelly P, Hurley G, Luo F, Chen K, O’Sullivan GC, Kiely B, Collins JK, Shanahan F, Quigley EMM. Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: Symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(3):541–51.

- Ringel-Kulka T, Palsson OS, Maier D, Carroll I, Galanko JA, Leyer G, Ringel Y. Probiotic Bacteria Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07 Versus Placebo for the Symptoms of Bloating in Patients With Functional Bowel Disorders: A Double-blind Study. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2011;45(6):518–25.

- Quigley EMM. Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: The Science and the Evidence. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2015;49:S60.

- Hyland NP, Quigley EM, Brint E. Microbiota-host interactions in irritable bowel syndrome: Epithelial barrier, immune regulation and brain-gut interactions. WJG. 2014;20(27):8859.

- Latif A, Shehzad A, Niazi S, Zahid A, Ashraf W, Iqbal MW, Rehman A, Riaz T, Aadil RM, Khan IM, Özogul F, Rocha JM, Esatbeyoglu T, Korma SA. Probiotics: mechanism of action, health benefits and their application in food industries. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1216674.

- Ianiro G, Pecere S, Giorgio V, Gasbarrini A, Cammarota G. Digestive Enzyme Supplementation in Gastrointestinal Diseases. CDM. 14 2016;17(2):187–93.

- Vejdani R, Shalmani HRM, Mir-Fattahi M, Sajed-Nia F, Abdollahi M, Zali MR, Alizadeh AHM, Bahari A, Amin G. The Efficacy of an Herbal Medicine, Carmint, on the Relief of Abdominal Pain and Bloating in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Pilot Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51(8):1501–7.

- Konstantis G, Efstathiou S, Pourzitaki C, Kitsikidou E, Germanidis G, Chourdakis M. Efficacy and safety of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials using ROME IV criteria. Clin Nutr. 2023; 42(5):800–9.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).