Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

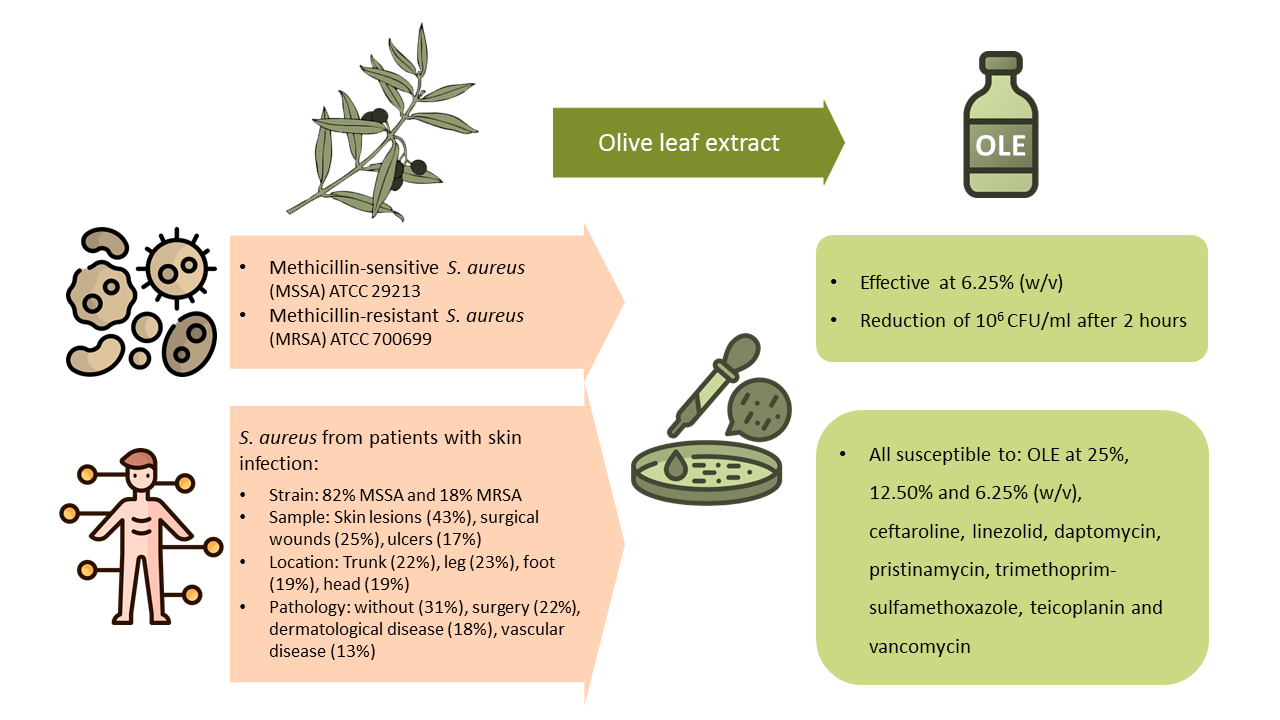

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

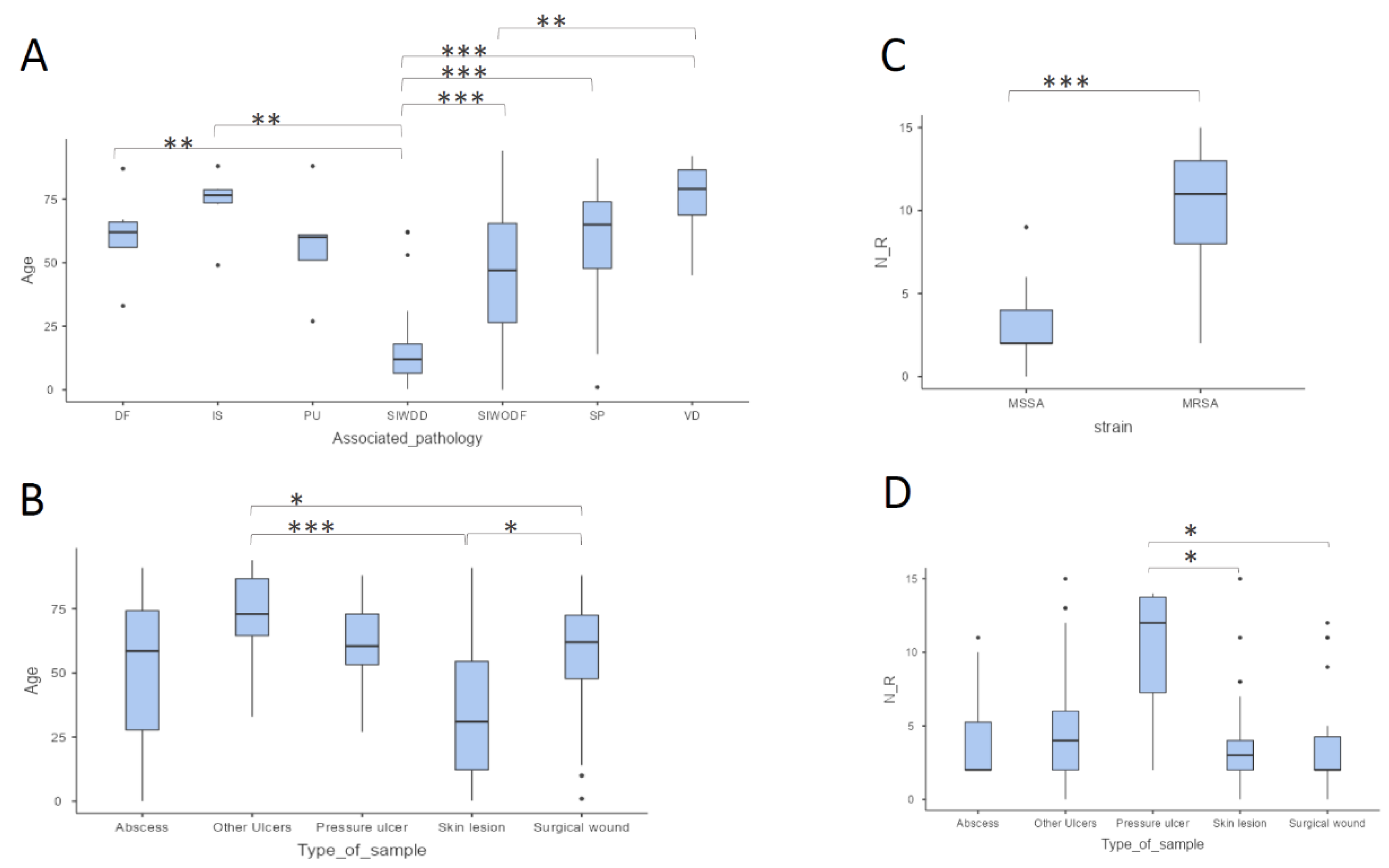

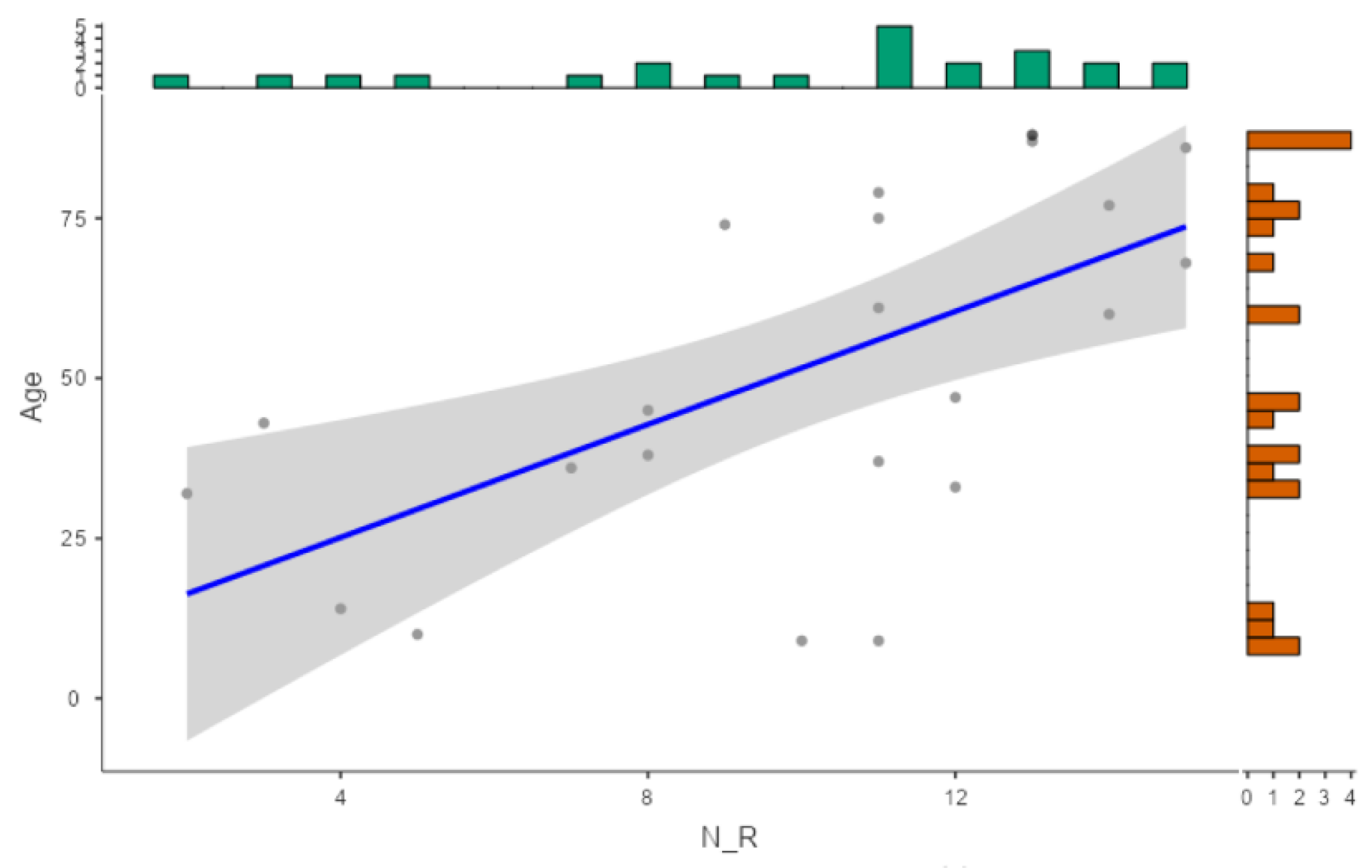

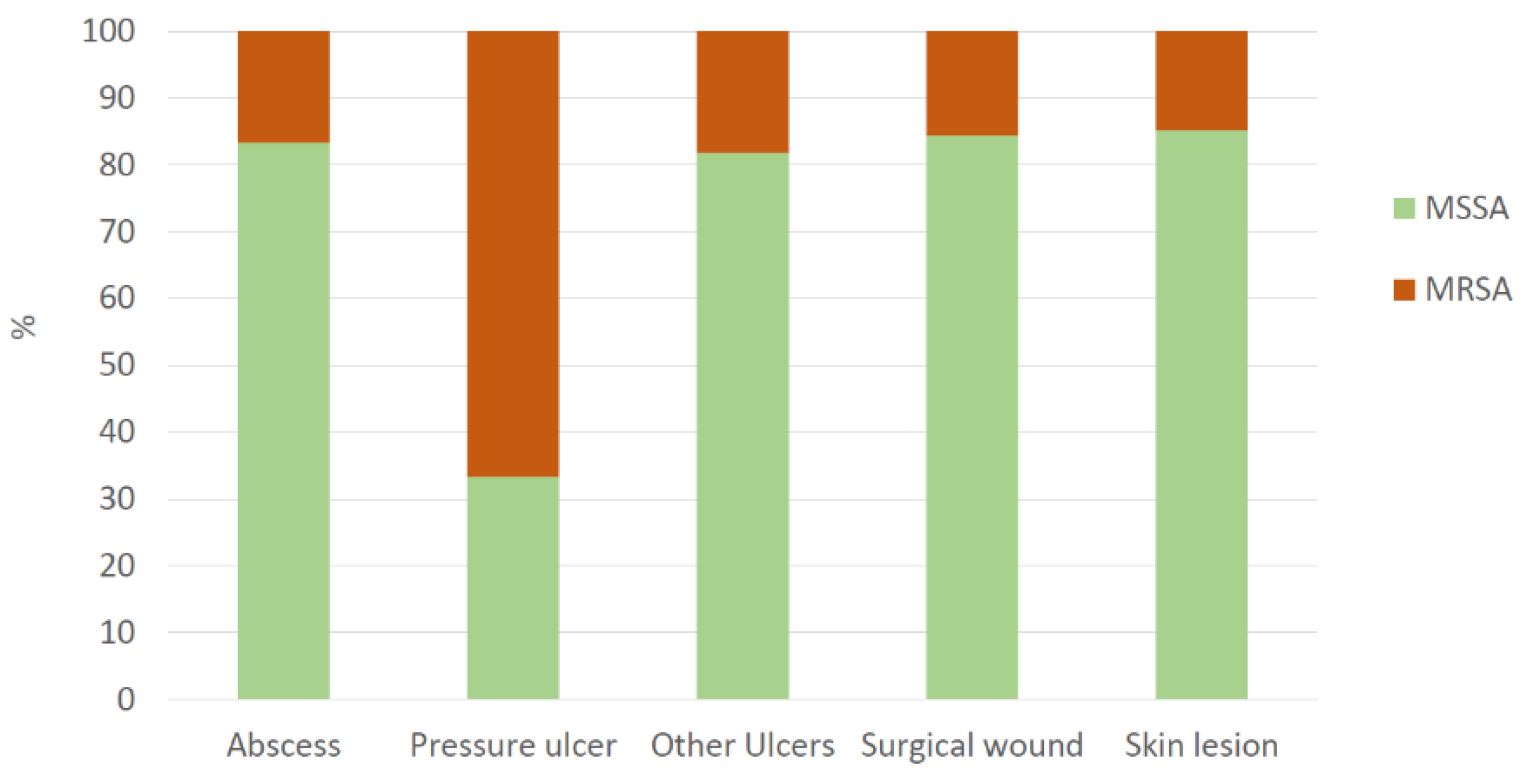

2.1. Epidemiological Description of Clinical Samples

2.2. Antibiotic Resistance Patterns

2.2.1. Susceptibility Tests on ATCC (American Type Culture Collection) Samples

2.2.2. Susceptibility Tests on ATCC Samples

2.2.3. Antibiotic Families and Efficacy

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. OLE Extraction

4.2. OLE phenolic Profile

4.3. Bacteria

4.3.1. Reference S. aureus Strains

4.3.2. S. aureus Strains from Clinical Samples

4.4. OLE Bacterial Susceptibility Test on Agar Plate

4.5. Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

4.6. Lethal Curve

4.7. Antibiotic Susceptibility

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSTIs | Skin and soft tissue infections |

| MSSA | Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| OLE | Olive leaf extract |

| MBC | Minimum bactericidal concentration |

| CFU | Colony-forming units |

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| UVB | Ultraviolet B |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| DF | Diabetic foot |

| IS | Immunosuppression |

| PU | Pressure ulcer |

| SIWDD | Skin infection with dermatological disease |

| SIWODF | Skin infection without dermatological factors |

| SP | Surgical procedure |

| VD | Vascular disease |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| CBA | Columbia blood agar |

| MALDI-TOF | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight |

| MHA | Müller-Hinton agar |

| CAMHB | Cation Adjusted Müller-Hinton Broth |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| UPLC-MS/MS | Ultra-Performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry system |

References

- Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Sharara, F.; Mestrovic, T.; Gray, A.P.; Davis Weaver, N.; Wool, E.E.; Han, C.; Gershberg Hayoon, A.; et al. Global Mortality Associated with 33 Bacterial Pathogens in 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2022, 400, 2221–2248. [CrossRef]

- Gehrke, A.-K.E.; Giai, C.; Gómez, M.I. Staphylococcus Aureus Adaptation to the Skin in Health and Persistent/Recurrent Infections. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1520. [CrossRef]

- Schachner, L.A.; Andriessen, A.; Gonzalez, M.E.; Lal, K.; Hebert, A.A.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Lio, P. A Consensus on Staphylococcus Aureus Exacerbated Atopic Dermatitis and the Need for a Novel Treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2024, 23, 825–832. [CrossRef]

- Tomi, N.S.; Kränke, B.; Aberer, E. Staphylococcal Toxins in Patients with Psoriasis, Atopic Dermatitis, and Erythroderma, and in Healthy Control Subjects. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2005, 53, 67–72. [CrossRef]

- Linz, M.S.; Mattappallil, A.; Finkel, D.; Parker, D. Clinical Impact of Staphylococcus Aureus Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 557. [CrossRef]

- Ki, V.; Rotstein, C. Bacterial Skin and Soft Tissue Infections in Adults: A Review of Their Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Treatment and Site Of Care. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology 2008, 19, 173–184. [CrossRef]

- Frazee, B.W.; Lynn, J.; Charlebois, E.D.; Lambert, L.; Lowery, D.; Perdreau-Remington, F. High Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus in Emergency Department Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2005, 45, 311–320. [CrossRef]

- King, M.D.; Humphrey, B.J.; Wang, Y.F.; Kourbatova, E.V.; Ray, S.M.; Blumberg, H.M. Emergence of Community-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus USA 300 Clone as the Predominant Cause of Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections. Ann Intern Med 2006, 144, 309–317.

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Antimicrobial Resistance in the EU-EEA (EARS-Net) Annual Epidemiological Report for 2021; ECDC: Stockholm, 2022; p. 20;.

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. IDR 2019, Volume 12, 3903–3910. [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, M.A.; Khan, A.; Hanif, M.; Farooq, U.; Perveen, S. Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology of Olea Europaea (Olive). Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2015, 2015, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Vique, C.; Navarro-Alarcón, M.; Rodríguez Martínez, C.; Fonollá-Joya, J. Efecto hipotensor de un extracto de componentes bioactivos de hojas de olivo: estudio clínico preliminar. Nutrición Hospitalaria 2015, 242–249. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.A.; Norhayati, M.N.; Mohamad, N. Olive Leaf Extract Effect on Cardiometabolic Profile among Adults with Prehypertension and Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11173. [CrossRef]

- Lins, P.G.; Marina Piccoli Pugine, S.; Scatolini, A.M.; De Melo, M.P. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Olive Leaf Extract (Olea Europaea L.) and Its Protective Effect on Oxidative Damage in Human Erythrocytes. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00805. [CrossRef]

- Wainstein, J.; Ganz, T.; Boaz, M.; Bar Dayan, Y.; Dolev, E.; Kerem, Z.; Madar, Z. Olive Leaf Extract as a Hypoglycemic Agent in Both Human Diabetic Subjects and in Rats. Journal of Medicinal Food 2012, 15, 605–610. [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, C.D.; Bond, D.R.; Jankowski, H.; Weidenhofer, J.; Stathopoulos, C.E.; Roach, P.D.; Scarlett, C.J. The Olive Biophenols Oleuropein and Hydroxytyrosol Selectively Reduce Proliferation, Influence the Cell Cycle, and Induce Apoptosis in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. IJMS 2018, 19, 1937. [CrossRef]

- Karygianni, L.; Cecere, M.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; Argyropoulou, A.; Hellwig, E.; Aligiannis, N.; Wittmer, A.; Al-Ahmad, A. High-Level Antimicrobial Efficacy of Representative Mediterranean Natural Plant Extracts against Oral Microorganisms. BioMed Research International 2014, 2014, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Markin, D.; Duek, L.; Berdicevsky, I. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Olive Leaves. Antimikrobielle Wirksamkeit von Olivenblättern in Vitro. Mycoses 2003, 46, 132–136. [CrossRef]

- Sudjana, A.N.; D’Orazio, C.; Ryan, V.; Rasool, N.; Ng, J.; Islam, N.; Riley, T.V.; Hammer, K.A. Antimicrobial Activity of Commercial Olea Europaea (Olive) Leaf Extract. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2009, 33, 461–463. [CrossRef]

- Zorić, N.; Kopjar, N.; Bobnjarić, I.; Horvat, I.; Tomić, S.; Kosalec, I. Antifungal Activity of Oleuropein against Candida Albicans—The In Vitro Study. Molecules 2016, 21, 1631. [CrossRef]

- Borjan, D.; Leitgeb, M.; Knez, Ž.; Hrnčič, M.K. Microbiological and Antioxidant Activity of Phenolic Compounds in Olive Leaf Extract. Molecules 2020, 25, 5946. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.P.; Ferreira, I.C.; Marcelino, F.; Valentão, P.; Andrade, P.B.; Seabra, R.; Estevinho, L.; Bento, A.; Pereira, J.A. Phenolic Compounds and Antimicrobial Activity of Olive (Olea Europaea L. Cv. Cobrançosa) Leaves. Molecules 2007, 12, 1153–1162. [CrossRef]

- Ayana, B.; Turhan, K.N. Use of Antimicrobial Methylcellulose Films to Control Staphylococcus Aureus during Storage of Kasar Cheese. Packag Technol Sci 2009, 22, 461–469. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.M.; Rabii, N.S.; Garbaj, A.M.; Abolghait, S.K. Antibacterial Effect of Olive (Olea Europaea L.) Leaves Extract in Raw Peeled Undeveined Shrimp (Penaeus Semisulcatus). International Journal of Veterinary Science and Medicine 2014, 2, 53–56. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; McKeever, L.C.; Malik, N.S.A. Assessment of the Antimicrobial Activity of Olive Leaf Extract Against Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Melguizo-Rodríguez, L.; González-Acedo, A.; Illescas-Montes, R.; García-Recio, E.; Ramos-Torrecillas, J.; Costela-Ruiz, V.J.; García-Martínez, O. Biological Effects of the Olive Tree and Its Derivatives on the Skin. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 11410–11424. [CrossRef]

- Torrecillas-Baena, B.; Camacho-Cardenosa, M.; Carmona-Luque, M.D.; Dorado, G.; Berenguer-Pérez, M.; Quesada-Gómez, J.M.; Gálvez-Moreno, M.Á.; Casado-Díaz, A. Comparative Study of the Efficacy of EHO-85, a Hydrogel Containing Olive Tree (Olea Europaea) Leaf Extract, in Skin Wound Healing. IJMS 2023, 24, 13328. [CrossRef]

- Sumiyoshi, M.; Kimura, Y. Effects of Olive Leaf Extract and Its Main Component Oleuroepin on Acute Ultraviolet B Irradiation-induced Skin Changes in C57BL/6J Mice. Phytotherapy Research 2010, 24, 995–1003. [CrossRef]

- Mehraein, F.; Sarbishegi, M.; Aslani, A. Evaluation of Effect of Oleuropein on Skin Wound Healing in Aged Male Balb/c Mice. Cell Journal 2014, 16, 25–30.

- Elnahas, R.A.; Elwakil, B.H.; Elshewemi, S.S.; Olama, Z.A. Egyptian Olea Europaea Leaves Bioactive Extract: Antibacterial and Wound Healing Activity in Normal and Diabetic Rats. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2021, 11, 427–434. [CrossRef]

- Zamanifard, M.; Nasiri, M.; Yarahmadi, F.; Zonoori, S.; Razani, O.; Salajegheh, Z.; Imanipour, M.; Mohammadi, S.M.; Jomehzadeh, N.; Asadi, M. Healing of Diabetic Foot Ulcer with Topical and Oral Administrations of Herbal Products: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. International Wound Journal 2024, 21, e14760. [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi Rad, F.; Changaee, F.; Toulabi, T.; Yari, F.; Rashidipour, M.; Mohammadi, R.; Yarahmadi, S.; Almasian, M. The Efficacy of Combined Olive Leaf and Curcumin Extract on Healing Human Papillomavirus: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2023, 2023, 2001770. [CrossRef]

- Toulabi, T.; Delfan, B.; Rashidipour, M.; Yarahmadi, S.; Ravanshad, F.; Javanbakht, A.; Almasian, M. The Efficacy of Olive Leaf Extract on Healing Herpes Simplex Virus Labialis: A Randomized Double-Blind Study. EXPLORE 2022, 18, 287–292. [CrossRef]

- Hiramatsu, K.; Ito, T.; Tsubakishita, S.; Sasaki, T.; Takeuchi, F.; Morimoto, Y.; Katayama, Y.; Matsuo, M.; Kuwahara-Arai, K.; Hishinuma, T.; et al. Genomic Basis for Methicillin Resistance in Staphylococcus Aureus. Infect Chemother 2013, 45, 117. [CrossRef]

- Laurent, F. Fitness and Competitive Growth Advantage of New Gentamicin-Susceptible MRSA Clones Spreading in French Hospitals. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2001, 47, 277–283. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.E.; Deventer, A.T.; Johnston, P.R.; Lowe, P.T.; Boraston, A.B.; Hobbs, J.K. Staphylococcus Aureus COL: An Atypical Model Strain of MRSA That Exhibits Slow Growth and Antibiotic Tolerance 2024.

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Jia, Q.; LaMacchia, V.; O’Donoghue, K.; Huang, Z. A Systems Biology Approach to Investigate the Antimicrobial Activity of Oleuropein. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 2016, 43, 1705–1717. [CrossRef]

- Silvan, J.M.; Guerrero-Hurtado, E.; Gutierrez-Docio, A.; Prodanov, M.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.J. Olive Leaf as a Source of Antibacterial Compounds Active against Antibiotic-Resistant Strains of Campylobacter Jejuni and Campylobacter Coli. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 26. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.; Yoon, Y.; Choi, K.-H. Antimicrobial Action of Oleanolic Acid on Listeria Monocytogenes, Enterococcus Faecium, and Enterococcus Faecalis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118800. [CrossRef]

- Carraro, L.; Fasolato, L.; Montemurro, F.; Martino, M.E.; Balzan, S.; Servili, M.; Novelli, E.; Cardazzo, B. Polyphenols from Olive Mill Waste Affect Biofilm Formation and Motility in Escherichia Coli K-12. Microbial Biotechnology 2014, 7, 265–275. [CrossRef]

- Lim, A.; Subhan, N.; Jazayeri, J.A.; John, G.; Vanniasinkam, T.; Obied, H.K. Plant Phenols as Antibiotic Boosters: In Vitro Interaction of Olive Leaf Phenols with Ampicillin. Phytotherapy Research 2016, 30, 503–509. [CrossRef]

- Cela, E.M.; Urquiza, D.; Gómez, M.I.; Gonzalez, C.D. New Weapons to Fight against Staphylococcus Aureus Skin Infections. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1477. [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.; Qadir, A. Frequency and Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern of Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (CA-MRSA) in Uncomplicated Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2022, 32, 1398–1403. [CrossRef]

- Manzur, A.; Gavalda, L.; Ruiz De Gopegui, E.; Mariscal, D.; Dominguez, M.A.; Perez, J.L.; Segura, F.; Pujol, M. Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus and Factors Associated with Colonization among Residents in Community Long-Term-Care Facilities in Spain. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2008, 14, 867–872. [CrossRef]

- Tognetti, L.; Martinelli, C.; Berti, S.; Hercogova, J.; Lotti, T.; Leoncini, F.; Moretti, S. Bacterial Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: Review of the Epidemiology, Microbiology, Aetiopathogenesis and Treatment: A Collaboration between Dermatologists and Infectivologists. Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012, 26, 931–941. [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A.; Kest, H.; Sood, M.; Steussy, B.; Thieman, C.; Gupta, S. Biofilm Producing Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Infections in Humans: Clinical Implications and Management. Pathogens 2024, 13, 76. [CrossRef]

- Porras-Luque, J.I. Antimicrobianos tópicos en Dermatología. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas 2007, 98, 29–39. [CrossRef]

- Zabielinski, M.; McLeod, M.P.; Aber, C.; Izakovic, J.; Schachner, L.A. Trends and Antibiotic Susceptibility Patterns of Methicillin-Resistant and Methicillin-Sensitive Staphylococcus Aureus in an Outpatient Dermatology Facility. JAMA Dermatol 2013, 149, 427. [CrossRef]

- Zhanel, G.G.; Adam, H.J.; Baxter, M.; Lagace-Wiens, P.R.S.; Karlowsky, J.A. In Vitro Activity and Resistance Rates of Topical Antimicrobials Fusidic Acid, Mupirocin and Ozenoxacin against Skin and Soft Tissue Infection Pathogens Obtained across Canada (CANWARD 2007–18). Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2021, 76, 1808–1814. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Beamonte, R.; Barranquero, C.; Gascón, S.; Mariño, J.; Arnal, C.; Estopañán, G.; Rodriguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Surra, J.C.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Odriozola-Serrano, I.; et al. Effect of Virgin Olive Oil as Spreadable Preparation on Atherosclerosis Compared to Dairy Butter in Apoe-Deficient Mice. J Physiol Biochem 2024, 80, 671–683. [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Test; Approved Standards- Twelfth Edition; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 950 West Valley Road, Suite 2500, Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087 USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-56238-985-7.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard - Ninth Edition; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 950 West Valley Road, Suite 2500, Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-56238-783-9.

- Eucast: S, I and R Definitions Available online: https://www.eucast.org/newsiandr (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- The Jamovi Project 2022.

| MSSA N (%) | MRSA N (%) | Overall samples N (%) | Age (median (P25-P75)) |

Quantity of antibiotic resistances (median (P25-P75)) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 103 (81.7) | 23 (18.3) | 126 | 56.0 (27.5-73.8) | 3.0 (2.0-5.0) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Men | 63 (61.2) | 11 (47.8) | 74 (58.7) | 59.5 (25.3-72.8) | 3.5 (2.0-5.0) |

| Women | 40 (38.8) | 12 (52.2) | 52 (41.3) | 50.0 (28.5-74.8) | 3.0 (2.0-5.0) |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 0-18 | 22 (21.4) | 4 (17.4) | 26 (20.6) | 8.0 (5.0-12.8) | 3.5 (2.0-4.0) |

| 19-65 | 44 (42.7) | 10 (43.5) | 54 (42.9) | 50.0 (36.3-58.8) | 3.5 (2.0-5.0) |

| >65 | 37 (35.9) | 9 (39.1) | 46 (36.5) | 78.5 (72.3-85.3) | 2.0 (2.0-4.75) |

| Number of antibiotic resistances | |||||

| 0-5 | 97 (94.2) | 4 (17.4) | 101 (80.2) | 56.0 (20.0-72.0) | 2.0 (2.0-4.0) |

| 6-10 | 6 (5.8) | 5 (21.7) | 11 (8.7) | 45.0 (35.0-59.0) | 7.0 (6.0-8.5) |

| 11-15 | 0 (0) | 14 (60.9) | 14 (11.1) | 71.5 (50.3-84.3) | 12.5 (11.0-13.8) |

| Type of sample | |||||

| Abscess | 10 (9.7) | 2 (8.7) | 12 (9.5) | 58.5 (27.8-74.3) | 2.0 (2.0-5.25) |

| Pressure ulcer | 2 (1.9) | 4 (17.4) | 6 (4.8) | 60.5 (53.3-73.0) | 12.0 (7.25-13.8) |

| Other Ulcers | 18 (17.5) | 4 (17.4) | 22 (17.5) | 73.0 (64.5-86.8) | 4.0 (2.0-6.0) |

| Surgical wound | 27 (26.2) | 5 (21.7) | 32 (25.4) | 62.0 (47.8-72.5) | 2.0 (2.0-4.25) |

| Skin lesion | 46 (44.7) | 8 (34.8) | 54 (42.9) | 31.0 (12.3-54.5) | 3.0 (2.0-4.0) |

| Location | |||||

| Generalized (all body) | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.6) | 3.5 (3.25-3.75) | 4.5 (4.25-4.75) |

| Arm | 8 (7.8) | 2 (8.7) | 10 (7.9) | 59.0 (40.3-69.5) | 3.50 (2.0-5.0) |

| Hand | 3 (2.9) | 2 (8.7 | 5 (4.0) | 50.0 (22.0-68.0) | 5.0 (4.0-5.0) |

| Head | 21 (20.4) | 3 (13.0) | 24 (19.0) | 50.5 (18.8-73.3) | 4.0 (2.0-4.0) |

| Trunk | 21 (20.4) | 7 (30.4) | 28 (22.2) | 58.0 (30.0-68.0) | 2.5 (2.0-6.25) |

| Leg | 26 (25.2) | 3 (13.0) | 29 (23.0) | 64.0 (24.0-82.0) | 2.0 (2.0-4.0) |

| Foot | 20 (19.4) | 4 (17.4) | 24 (19.0) | 62.5 (50.0-80.5) | 3.0 (2.0-6.0) |

| Toenail | 2 (1.9) | 2 (8.7) | 4 (3.2) | 34.0 (28.0-39.5) | 2.0 (1.5-3.25) |

| Associated pathology | |||||

| Diabetic foot | 7 (6.8) | 2 (8.7) | 9 (7.1) | 62.0 (56.0-66.0) | 4.0 (2.0-6.0) |

| Immunosuppression | 4 (3.9) | 2 (8.7) | 6 (4.8) | 76.5 (73.5-78.8) | 3.5 (2.25-9.25) |

| Immobilization (Pressure ulcer) | 2 (1.9) | 3 (13.0) | 5 (4.0) | 60.0 (51.0-61.0) | 11 (6.0-13.0) |

| Skin infection w/o dermatological factors | 31 (30.1) | 8 (34.8) | 39 (31.0) | 47.0 (26.5-65.5) | 2.0 (2.0 -4.0) |

| Skin infection with dermatological disease | 22 (21.4) | 1 (4.3) | 23 (18.3) | 12.0 (6.50-18.0) | 4.0 (2.0-4.0) |

| Surgical procedure | 25 (24.3) | 3 (13.0) | 28 (22.2) | 65.0 (47.8-74.0) | 2.0 (2.0-4.0) |

| Vascular disease | 12 (11.7) | 4 (17.4) | 16 (12.7) | 79.0 (68.8-86.5) | 4 (2.75-6.5) |

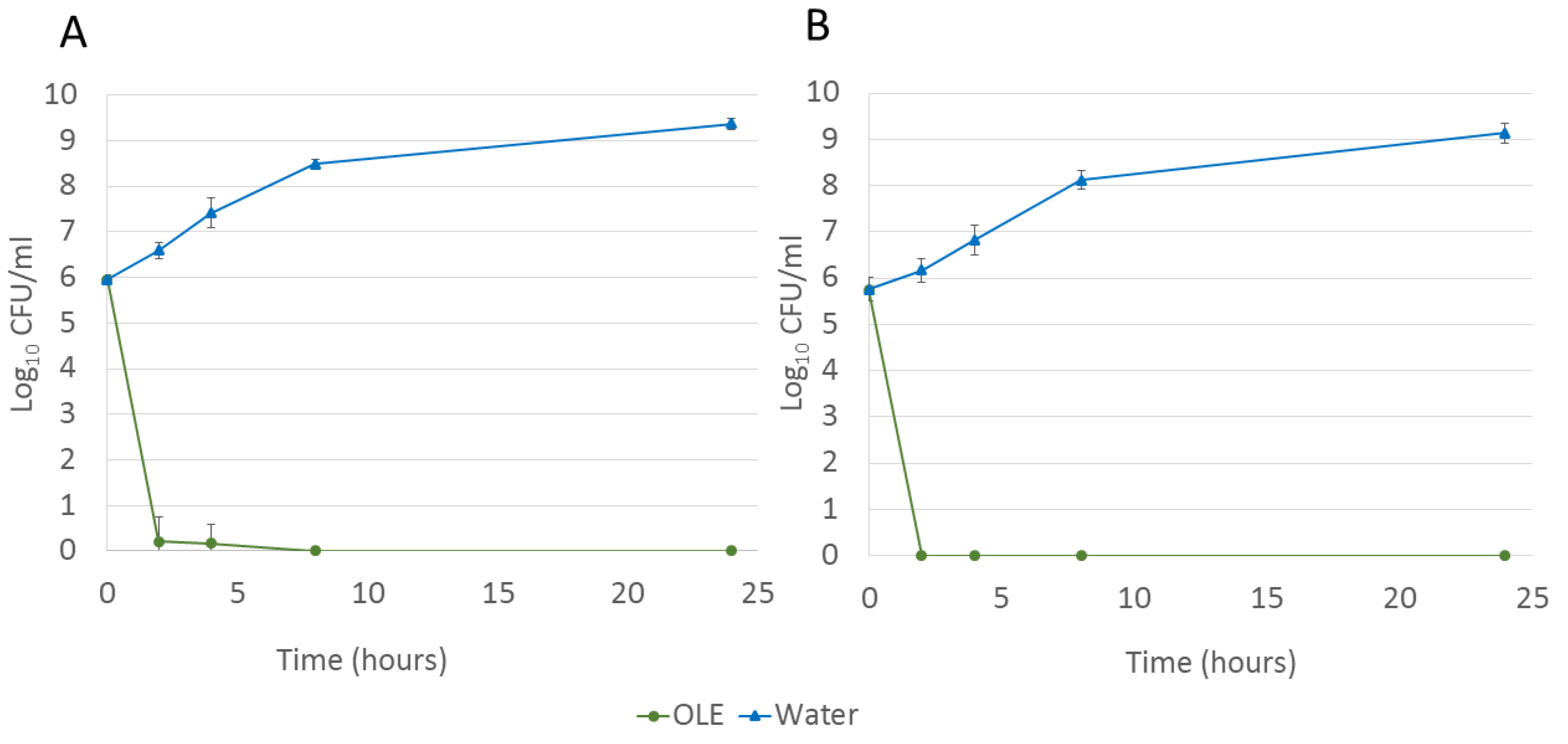

| MSSA | MRSA | |||

| Control | OLE | Control | OLE | |

| 0 (hours) | 5.95 ± 0.11 | 5.95 ± 0.11 | 5.76 ± 0.25 | 5.76 ± 0.25 |

| 2 (hours) | 6.60 ± 0.18 | 0.22 ± 0.53 | 6.17 ± 0.26 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 4 (hours) | 7.42 ± 0.33 | 0.17 ± 0.41 | 6.83 ± 0.33 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 8 (hours) | 8.49 ± 0.10 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 8.12 ± 0.20 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 24 (hours) | 9.37 ± 0.13 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 9.14 ± 0.22 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

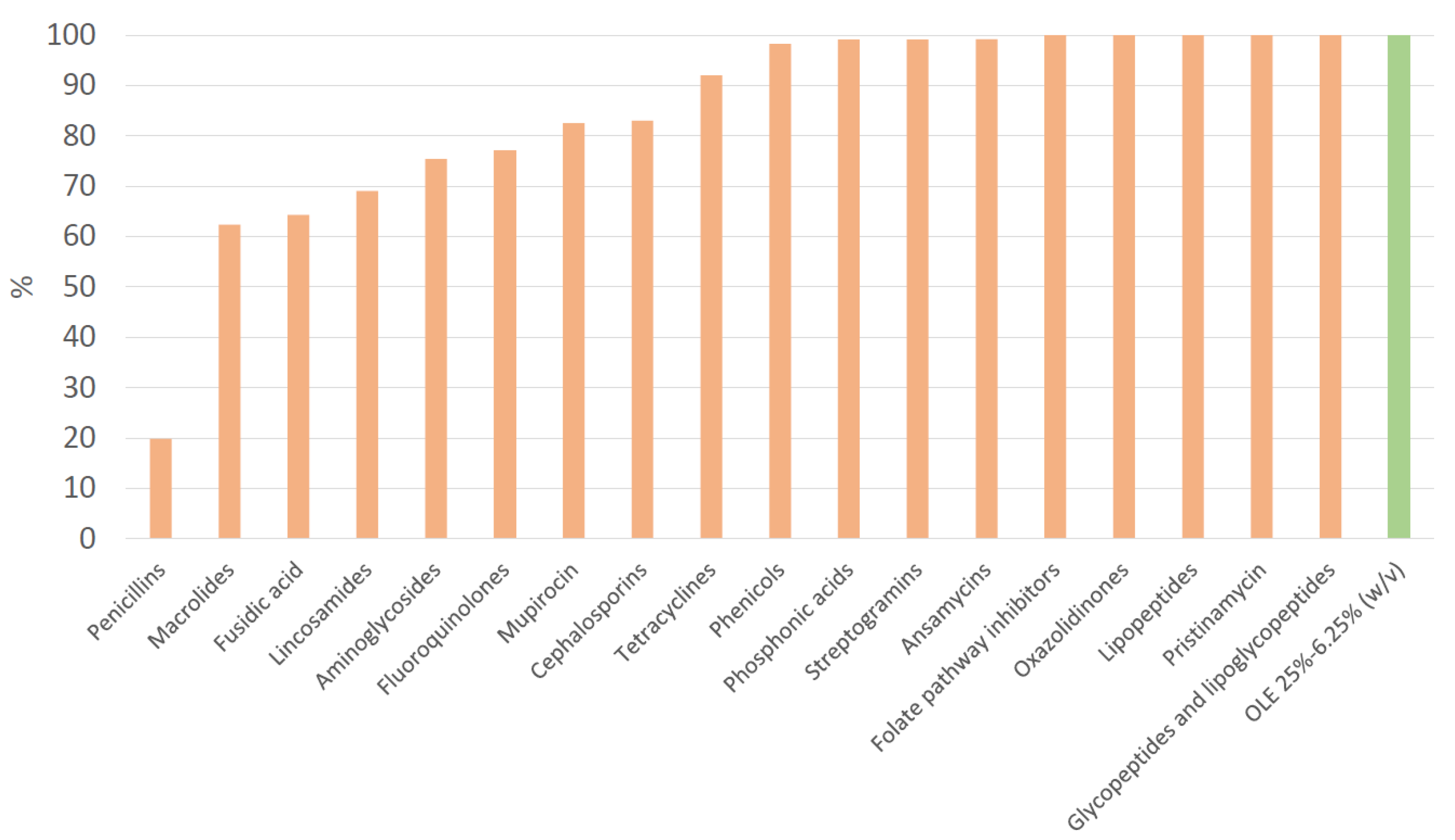

| Antibiotic class | Antibiotic | Overall N | Resistant N (%) | MSSA N (%) | MRSA N (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fucidane | Fusidic acid | 28 | 10 (35.7) | 4 (22.2) | 6 (60.0) | |

| Aminoglycosides | 126 | 31 (24.6) | 17 (16.5) | 14 (60.9) | <0.001 | |

| Amikacin | 119 | 16 (13.4) | 3 (3.0) | 13 (68.4) | <0.001 | |

| Gentamicin | 126 | 13 (10.3) | 5 (4.9) | 8 (34.8) | <0.001 | |

| Tobramycin | 119 | 29 (24.4) | 17 (17.0) | 12 (63.2) | <0.001 | |

| Penicillins | 126 | 101 (80.2) | 78 (75.7) | 23 (100.0) | 0.008 | |

| Ampicillin | 119 | 97 (81.5) | 78 (78.0) | 19 (100) | 0.024 | |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 119 | 19 (16.0) | 0 (0) | 19 (100) | <0.001 | |

| Oxacillin | 126 | 23 (18.3) | 0 (0) | 23 (100) | <0.001 | |

| Penicillin | 119 | 97 (81.5) | 78 (78) | 19 (100) | 0.024 | |

| Cephalosporins | 119 | 19 (16.0) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (100.0) | <0.001 | |

| Cefdinir | 119 | 19 (16.0) | 0 (0) | 19 (100) | <0.001 | |

| Ceftaroline* | 119 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Fluoroquinolones | 126 | 29 (23.0) | 12 (11.7) | 17 (73.9) | <0.001 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 126 | 28 (22.2) | 11 (10.7) | 17 (73.9) | <0.001 | |

| Levofloxacin | 119 | 24 (20.2) | 9 (9.0) | 15 (78.9) | <0.001 | |

| Moxifloxacin | 22 | 22 (100.0) | 7 (100) | 15 (100) | ||

| Lincosamides | Clindamycin | 126 | 39 (31.0) | 28 (27.2) | 11 (47.8) | |

| Macrolides | Erythromycin | 125 | 47 (37.6) | 31 (30.1) | 16 (72.7) | <0.001 |

| Streptogramins | Quinupristin-dalfopristin | 119 | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) | 0.021 |

| Oxazolidinones | Linezolid* | 126 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Tetracyclines | 126 | 10 (7.9) | 6 (5.8) | 4 (17.4) | ||

| Minocycline | 118 | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) | 0.022 | |

| Tetracycline | 126 | 10 (7.9) | 6 (5.8) | 4 (17.4) | ||

| Phenicols | Chloramphenicol | 119 | 2 (1.7) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Lipopeptides | Daptomycin* | 119 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Phosphonic acids | Fosfomycin | 118 | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) | 0.022 |

| Mupirocin | 126 | 22 (17.5) | 13 (12.6) | 9 (39.1) | 0.002 | |

| Pristinamycin* | 119 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Ansamycins | Rifampicin | 126 | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) | 0.034 |

| Folate pathway inhibitors | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole* | 126 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Glycopeptides and lipoglycopeptides | Teicoplanin* | 119 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Vancomycin* | 119 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Olive leaf extract | OLE 25%* | 126 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| OLE 12.5%* | 126 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| OLE 6.25%* | 126 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| OLE 3.125% | 126 | 119 (94.5) | 99 (96.1) | 20 (87.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).