1. Introduction

BK channels are K

+-selective, voltage- and Ca

2+-dependent channels that regulate fundamental cellular functions [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Their role in controlling vascular tone is well-established. Their unitary K

+ conductance (~250pS), an order of magnitude larger than that of typical voltage-gated K

+ channels, renders BK channels powerful regulators of the cell membrane potential and it is not surprising that serious human diseases have been associated with BK channel malfunction, including epilepsy and paroxysmal movement disorder [

49,

50].

While intracellular Ca

2+ is typically recognized the main regulator of BK channels, numerous other small signaling molecules, including Mg

2+, H

+, Ba

2+, NO, CO, heme/hemin, and nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids are capable of potently modulating the channel open probability [

1,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

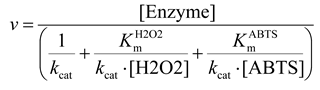

12]. The ligand-dependent gating of the BK channel is mediated by the gating ring (GR) apparatus a large torus-shaped structure formed by the assembly of the C-termini of four BK channel α subunits

(Figure 1 A and B) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Recent data have revealed a new role for the BK channel as a sensor of intracellular free hemin, the oxidized form of heme [Fe(II) protoporphyrin-IX]. Hemin [Fe(III) protoporphyrin-IX] facilitates the activation of BK channels at hyperpolarized potentials. However, it decreases the probability of channel opening at depolarized potentials [

18,

19,

20]. Heme is an important cell signaling molecule and influences the activity of other ion channels such as Kv1.4 [

51], KATP [

22], epithelial sodium channel [

23], and ether à go-go (hEAG1, Kv10.1) [

21] and Kv3.4 [

40], but the physiological significance of heme-dependent modulation of ion channel activity remains unknown.

Several mechanisms have been proposed regarding the modulation of BK channel activity by heme. Heme may be involved in BK-dependent physiological processes such as oxygen sensing [

52], which is related to the sensitivity of heme to a biologically signaling molecule such as CO [

53,

54]. Inhibition of BK channels by heme may also play a regulatory or compensatory role during vascular events such as stroke hemorrhage [

18,

19]. Future studies based on native BK channels will provide insights into the physiological role of heme regulatory function.

The BK channel ring is heme sensitive at the prosthetic group sitat site

612CKACH616 [

20,

54,

55], which is compatible with the conserved heme-binding motif CXXCH among the cytochrome c protein family [

24]. The heme-binding site lies a ~120-residue linker connecting two of the Ca

2+-sensing modules, RCK1 and RCK2 domains (

Figure 1 A and B), which has so far evaded atomic-level resolution in BK structure studies due to its unordered structure (

Figure 1C). In this work, we provide evidence that the BK channel heme-binding region shares a remarkable similarity with hemoprotein cytochrome c family proteins, one of the most extensively studied proteins. The mitochondrial cytochrome c is one of the first to be crystallized, primarily known for its role in the respiratory chain in mitochondria. Aside from its well-recognized role in electron shuttling, cytochrome c also performs a catalytically, peroxidase activity [

25]. Cytochrome c as well as other heme-bound peroxidases, can convert H

2O

2 into water in the presence of an electron donor. Based on this view, we have tested that the BK channel is more than the ligand-binding domain of the BK ion channel, but can also perform enzymatic functions under its heme-bearing cytochrome c-like domain. We hypothesized that, through their peroxidase activity, BK channels may perform multifunctional roles in cells.

2. Results

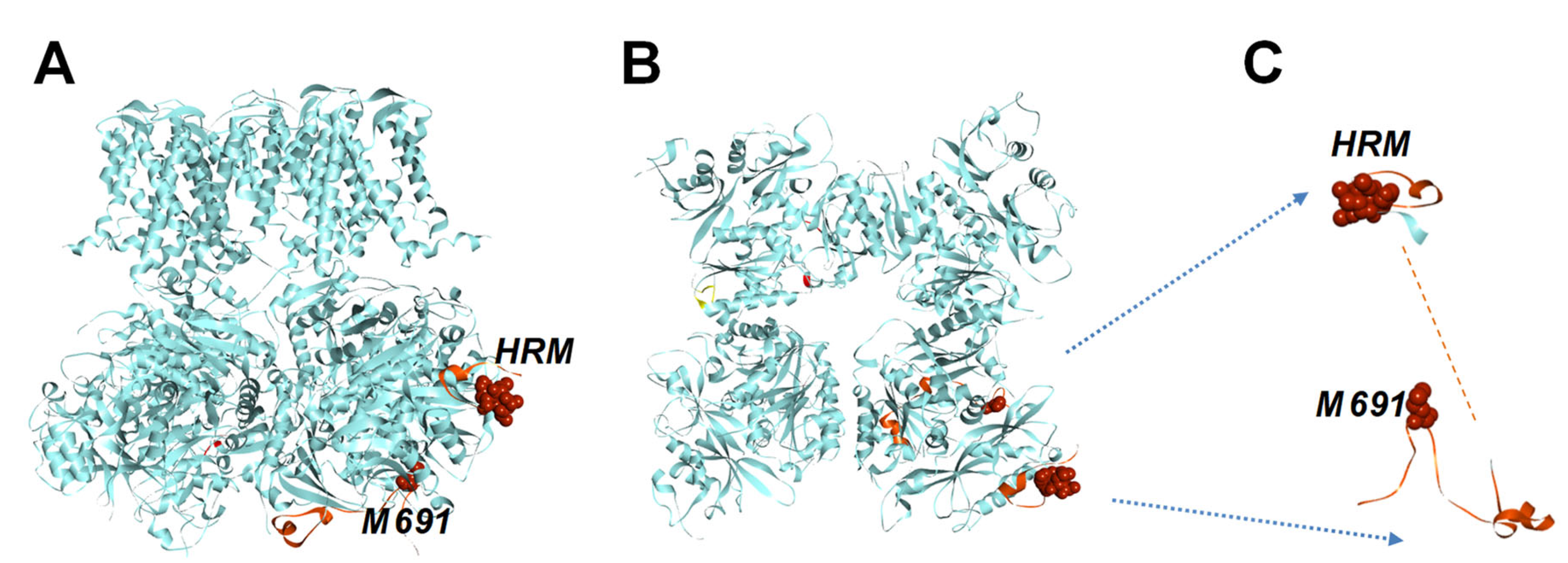

2.1. The Human BK Channel Structure Comprises a Cytochrome c-like Feature Within the Gating Ring

The linker region is between RCK1-RCK2 domains comprising

612CKACH616, compatible with the conserved heme-binding motif CXXCH among the cytochrome c protein family [

24]. The heme-binding site lies a ~120-residue linker connecting two of the Ca

2+ sensing modules, RCK1 and RCK2 domains (

Figure 1 A and B), which has so far evaded atomic-level resolution in BK structure studies (

Figure 1C). To test the hypothesis that the BK gating ring comprises a cytochrome c-like structure, we performed sequence alignment of the C-terminal portion of the RCK1 domain and the downstream RCK1-RCK2 linker (

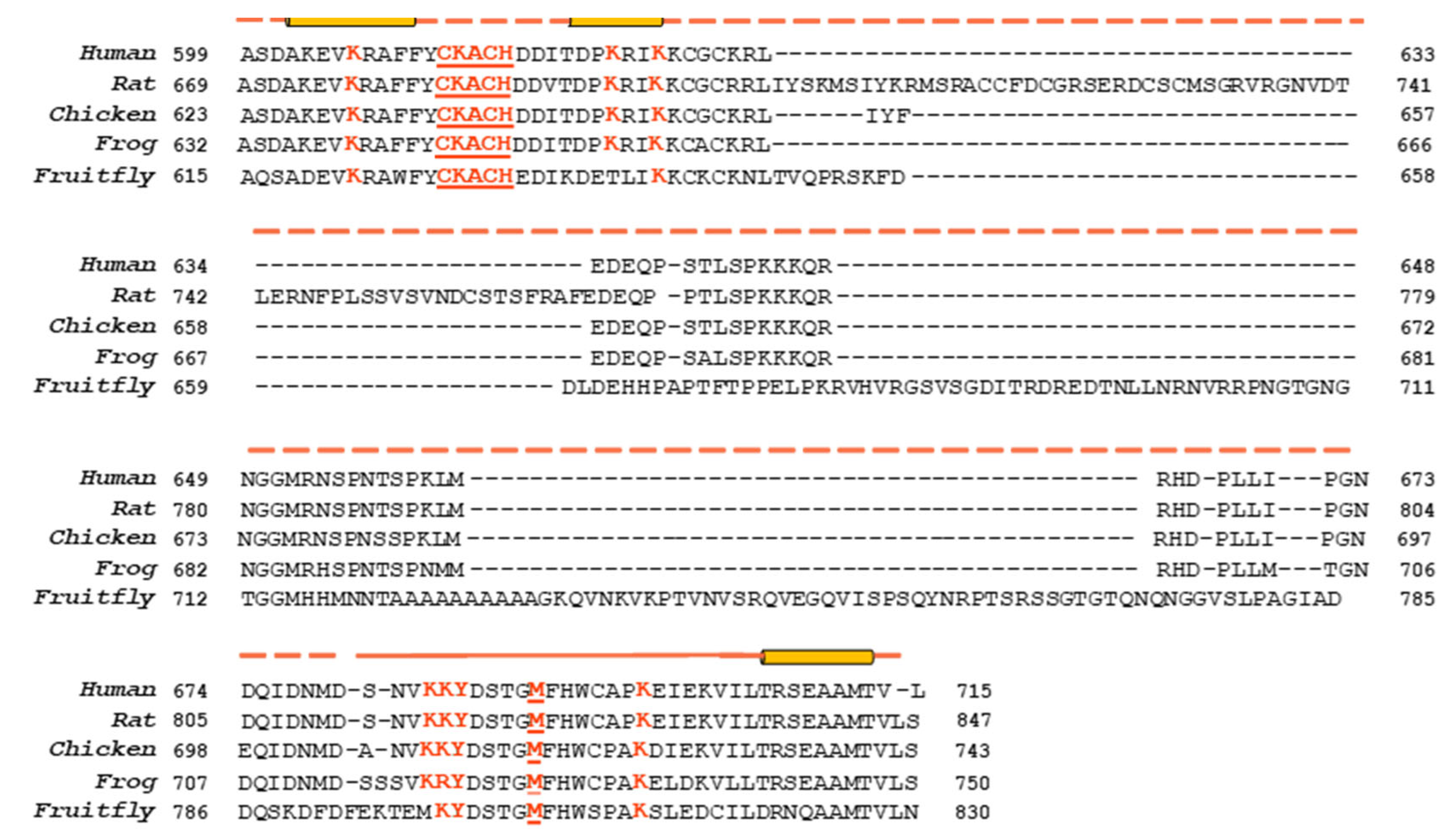

599ASD...TVL716), with human mitochondrial cytochrome C (

hCytC, PBD #1J3S). We found that, in addition to the heme-regulated motif HRM (

14CSQCH18), key structural elements of human mitochondrial CytC are conserved in this region of the human BK channel(

612CKACH616) (

Figure 2A): firstly, the portion of the BK region resolved in the available atomic structures shares secondary structure elements (N- and C-terminal α helices with CytC family proteins; secondly, CytC positively-charged residues critical for Apaf-1 and cardiolipin interaction align with BK residues K606, K623, R648, K684, K685 and K698; moreover, CytC Methionine residues at position at 80, the second axial ligand to the heme iron atom aligns with BK channel M691 [

25]. Cytochromes c is among the most studied proteins. The three-dimensional structure of mitochondrial cytochrome c was solved in 1970 [

24] (

Figure 2B).

Cytochrome c binds to heme through two thioether bonds involving the sulfhydryl groups of two cysteine residues, specifically

C14 and H18. These cysteine residues can form a reversible thiol/disulfide redox switch that regulates the affinity of the BK C-terminal domain for heme. The heme iron ion is always axially coordinated by a H616. Cytochrome c proteins are found throughout all organisms and belong to the cytochrome c-fold superfamily. These cytochrome c-fold proteins share common features: they are predominantly composed of alpha-helices and exhibit structural similarities despite having poorly conserved primary sequences. However, the heme coordination motif and the methionine (Met) residues are conserved among them. We investigated the structure-based sequence alignment of the human BK channel C-terminus (BK, PDB #6V3G) with several members of the cytochrome c family: human mitochondrial cytochrome c (hCytC, PBD #1J3S), yeast iso-1-cytochrome c (yCytC, PDB #1YFC), and the cytochrome c domain of nitrite reductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (nCytC, PDB #1NIR) (

Figure 2C). Additionally, we performed sequence analyses of cytochrome c domains from different proteins (

Figure 3).

This evidence suggests that the linker region may adopt a cytochrome c-like structure (known as the cytochrome c fold) within the C-terminal region of the BK channel, potentially stabilized by the presence of heme as a ligand. The RCK1-RCK2 linker region shows poor conservation across BK channels from different organisms, displaying variations in both length and amino acid composition compared to other regions of the BK channel. Notably, a primary sequence alignment of the region between the RCK1 and RCK2 domains reveals that crucial residues found in cytochrome c proteins—such as the HRM motif and the putative heme-coordinating methionine residue—along with functionally important positively charged residues, are highly conserved in this area (see

Figure 4).

The evolutionary conservation of cytochrome c elements in the linker region of large-conductance potassium (BK) channels suggests that these elements play a crucial role in the physiological functioning of the channel. It is important to note that, while cytochrome c domains have been identified in other proteins, this study is the first to demonstrate cytochrome c-like features within an ion channel.

The Slo family of K+ channels includes three known members that are gated by voltage and modulated differently: Slo-1 is regulated by Ca2+, Slo-2 is modulated by Cl- and Ca2+, and Slo-3 is influenced by pH. A primary sequence alignment among the Slo family channels reveals that Slo-2 channels do not contain a conserved CXXCH motif. In contrast, the HRM CXXCH motif is present in Slo-1 (612CKACH616) and Slo-3 (612CKSNH616), and methionine residues are also conserved across these channels.

2.2. The Human BK Channel Confers Peroxidase Activity

Cytochrome c, one of the most intensively studied multifunctional proteins, and one of the first to be crystallized, is primarily known for its role in the respiratory chain [

24].

Cytochrome c is found in various proteins and serves as an essential component in the electron transport chain, functioning as both an entry and exit point for electrons during the enzyme's catalytic cycle. Its primary role is to act as an electron carrier, transferring electrons from complex III to complex IV within the mitochondrial respiratory chain. The iron atom in the heme group alternates between two oxidation states—oxidized (Fe3+) and reduced (Fe2+)—as it facilitates the transport of electrons towards oxygen.

Recent studies on cell apoptosis have underscored the critical role of cytochrome c in programmed cell death. When an apoptotic signal is received, cytochrome c is released from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm. In the cytosol, it binds to APAF-1, which activates pro-caspase 9 and triggers an enzymatic cascade culminating in cell death. The release of cytochrome c and its involvement in apoptosis are regulated by multiple mechanisms closely tied to its catalytic and peroxidase activities. [

32,

33,

34].

We hypothesize that the human BK channel has peroxidase activity attributed to the RCK1-RCK2 linker region, which is proposed to function similarly to a cytochrome c-like domain (see

Figure 1-3). We investigate the peroxidase activity of both the C-terminal domain (Gating Ring) of the human BK channel and the full BK channel itself.

2.3. Peroxidase Activity of the Human BK Channel C-Terminal Domain

To investigate enzymatic activity, we expressed and purified the wild-type (WT), C615S/H616R, and M691A mutants of the human BK C-terminal domain (Figure S3). This domain self-assembles in solution into a physiologically relevant tetrameric structure known as the gating ring. The mutations in the heme-coordinated site did not appear to affect the overall secondary structure of the gating ring, as indicated by the Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy analysis of these channel proteins (Figure S3B and

Table 1).

A suitable electron donor is 2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonate) (ABTS), which can be used as a spectrophotometric reporter of peroxidase activity. The radical produced upon the oxidation of ABTS (ABTS+•) has maximal absorbance at ~415 nm, whereas the reduced form of ABTS absorbs maximally at ~340 nm. Thus, the time course of ABTS oxidation is ideal for the detection of peroxidase activity and the quantification of its reaction kinetics.

To spectroscopically probe for the enzymatic activity of the purified gating ring, we used the chromophore ABTS as the oxidizable substrate by H2O2 (see Material and Methods).

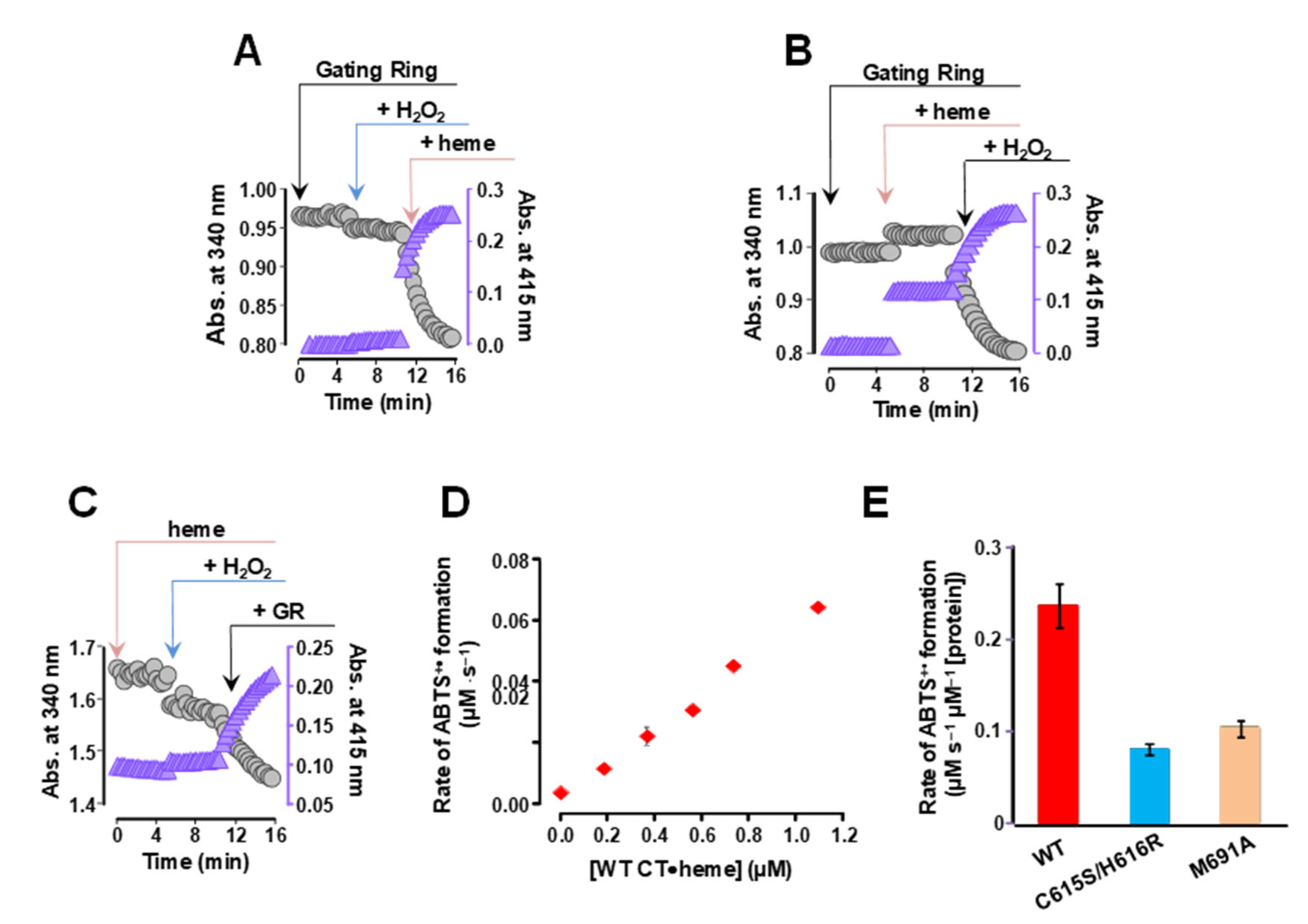

The time course for the oxidation of ABTS in the gating ring/heme complex reaction mixture is illustrated in

Figure 5A-C. These experiments demonstrate that the BK channel intracellular gating ring exhibits catalytic properties; specifically, peroxidase activity. Both the gating ring protein and the heme prosthetic group are required for the peroxidase activity observed in this assay (

Figure 5A-C).

We investigated the dependence of ABTS oxidation on the concentration of BK gating ring protein complexed with heme ([CT●heme]), which was determined by the slope of the first 60 s of the reaction. As shown in

Figure 5D, the initial rate of ABTS

+• formation linearly correlated with [CT●heme] up to 1.14 μM. We have also evaluated the role of heme-coordinating sites, the HRM (

612CKACH616) in the peroxidase activity of the gating ring and also the full BK channel, comparing the activities of the WT with and C615S/H616R and M691A gating ring mutants, respectively. We found that these mutations reduced the peroxidase activity of the gating ring, (

Figure 5E). This result demonstrates that the peroxidase activity of the BK channels gating ring requires an intact heme-binding site.

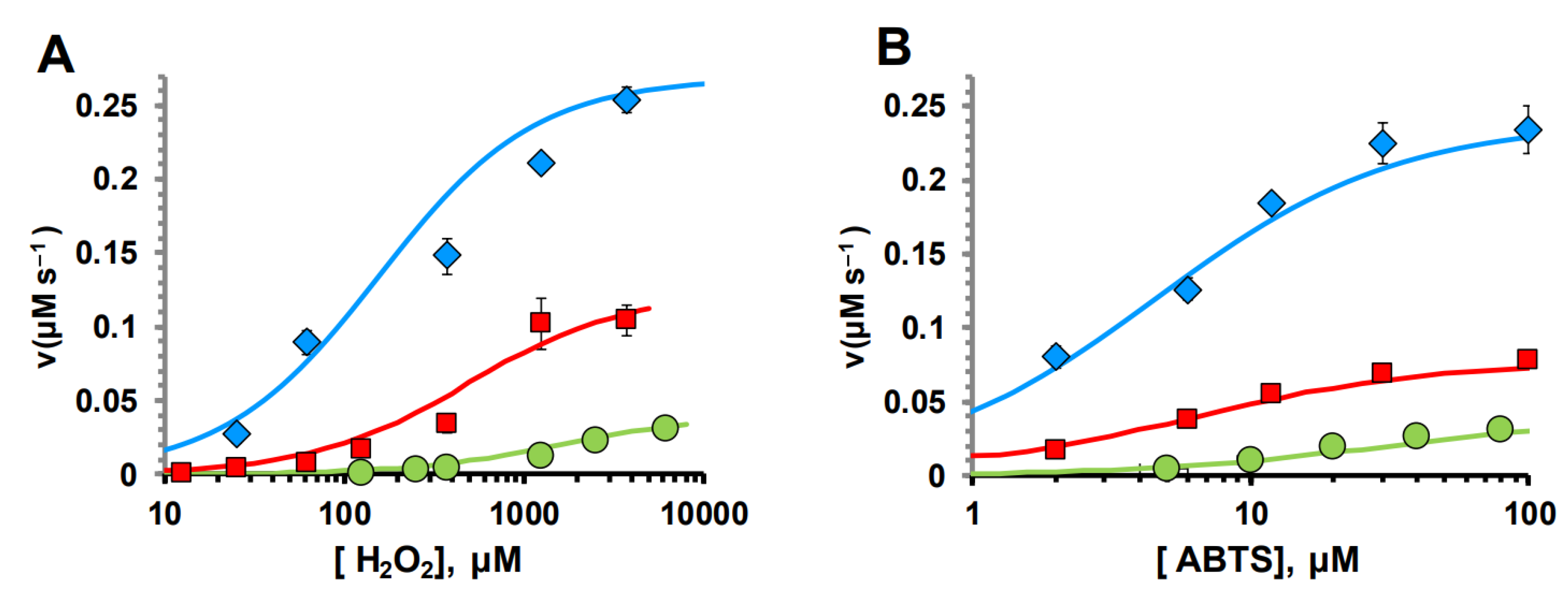

To address the mechanism of the enzymatic degradation of H2O2 by the gating ring we compared the kinetic parameters of human mitochondrial cytochrome C (hCytC) and the BK gating ring activity using a two-substrate Michaelis-Menten kinetic model (Figure 6, Table 2). Although the intrinsic catalytic rates (kcat) of the gating ring and hCytC are very similar, the human BK channel C-terminal exhibits higher apparent affinity for H2O2 and ABTS substrates than human cytochrome c: ~11-fold higher for H2O2 and ~8-fold higher for ABTS.

Figure 6.

The BK gating ring peroxidase activity is augmented by STREX insertion. (A) Peroxidase reaction kinetic parameters of CytC (green circles), GR (red squares) and GR-STREX (cyan diamonds) were determined by varying [H2O2] while ABTS was used at a fixed concentration (50 μM) and (B) vice versa (varying [ABTS] while [H2O2]=0.7mM) in the presence of 2 µM. The data for each protein were fit simultaneously using a two-substrate Michaelis-Menten kinetic model. Parameters are shown in Table 2.

Figure 6.

The BK gating ring peroxidase activity is augmented by STREX insertion. (A) Peroxidase reaction kinetic parameters of CytC (green circles), GR (red squares) and GR-STREX (cyan diamonds) were determined by varying [H2O2] while ABTS was used at a fixed concentration (50 μM) and (B) vice versa (varying [ABTS] while [H2O2]=0.7mM) in the presence of 2 µM. The data for each protein were fit simultaneously using a two-substrate Michaelis-Menten kinetic model. Parameters are shown in Table 2.

2.4. STREX Significantly Augmented CTD Peroxidase Activity

BK channels exhibit rich splice variation in tissues. One of the best-characterized alternative splice variants includes the stress-axis-regulated exon (STREX). Currents in inside-out patches pulled with STREX activated at voltages -20 mV negative to those with zero [

56,

57]. The inclusion of STREX results in a leftward shift in the conductance voltage curve with a Vh at 10 µM -22.33 ± 0.30 mV, compared with zero, which shows 20.5 ± 1.44 mV [

58]. The insertion of STREX also alters properties, such as BK channel properties, such as BK channel modulation by phosphorylation [

36] and palmitoylation [

37]. As STREX (

58aa) is inserted in the RCK1-RCK2 linker

(Figure S3), it could alter the functional activities of the BK CTD. Indeed, the inclusion of STREX significantly augmented CTD peroxidase activity. Assuming the same heme-binding properties, the peroxidase

kcat value was increased by ~2-fold, while the apparent substrate affinity was increased by ~3-fold for both H

2O

2 and ABTS.

2.5. The Full Human BK Channel Exhibits Peroxidase Activity

To evaluate the peroxidase activity of the full BK channel in a HEK293 cells lysates, we assessed peroxidase activity using the Amplex Red assay, which measures the resorufin fluorescence in the result oxidation of Amplex Red. Amplex Red reagent is a colorless substrate that reacts with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to produce highly fluorescent resorufin (emission maxima around 580 nm) in the presence of the peroxidase. Peroxidase activity assay performed in HEK293 cell lysates. HEK293 cells were transfected to yellow fluorescent protein with (YFP) or YFP was fused to the C-terminus of WT or C615S/H161R mutant human BK channel constructs (Figure S4). YFP fluorescence signal fused to the BK channel proteins allows to quantify of the expression level with the emission peak 527 nm, at excitation 500 nm. To determine the concentrations of expressed YFP, as well as YFP fused to the BK WT and BK C615S/H616R proteins in HEK lysates, we utilized the fluorescence emission intensity of YFP at 527 nm (with an excitation wavelength of 500 nm). After measuring the total protein concentration in the HEK cell lysates, we used the emission intensity at 527 nm to standardize for the equal amount of expressed YFP, YFP fused to BK WT, and BK C615S/H616R proteins in the Amplex Red assay.

The intensity of resorufin fluorescence formed in the in BK-transfected cells lysates were compared to that in cells expressing YFP alone and cells transfected with a BK HRM mutant with impaired heme-binding ability (C615S/H616R). This experiment revealed a high resorufin fluorescence intensity in BK channel-expressed cells compared to cells expressing only YFP (

Figure 7A). This data demonstrated that the full BK channel able to produce formation resorufin due to its peroxidase activity. We found that the C615S/H616R mutations reduced the fluorescence intensity of resorufin, indicating that heme-coordinating sites are critical for the peroxidase activity of the BK channel (

Figure 7B).

3. Discussion

3.1. Cytochrome-c-like Structure Within BK Channel Gating Ring

Heme serves as a novel regulator of various physiological processes and is essential for living organisms [

38,

39]. Recent studies have revealed that heme modulates the activity of ion channels [

3,

9,

21,

22,

24]. However, the molecular mechanisms behind heme-dependent regulatory control in ion channels remain unclear. The interaction sites where ion channels bind with heme are not well characterized and may vary across different ion channels. Currently, there is no evidence that heme binds directly to ion channels, and the specific heme-binding sites on ion channel proteins have not been identified. Attempts to obtain a co-crystal structure of heme-bound ion channel proteins have been unsuccessful [

59].

In this study, we are addressing to molecular basis heme-dependent regulation activity of the BK channel. We found that the heme coordinated region of the human BK channel located within the ~120 residues linker connecting two modules, RCK1 and RCK2 domains share similarities with cytochrome c family proteins

(Figure 2C). Like cytochrome c fold proteins, the structure of N- and C-terminals of this region are α helices, and in addition to the HRM (

CXXCH), M691 also are conserved, which is aligns with second axial ligand to the heme iron Met residues of cytochrome c family proteins. Cytochrome c achieves several diverse roles in cells. Its involvement in electron-transfer reactions between III and IV complexes, happening via transient protein-protein interfaces, is dependent on electron tunneling and conformational dynamic [

41]. This performance is driven by the cyt c’s hexa-coordinate structure with His18 and Met80 as the two axial ligands [

34]. In contrast, another critical role of cytochrome c in early apoptosis requires the of the disruption Met80-heme iron bond, which results in the partial unfolding of the protein, and increasing peroxidase activity of the protein [

34,

42]

To gain more insight into the structure of the RCK1-RCK2 linker region we more detailed compared its primary sequences with the sequences of this region (

Figure 2A). This analysis revealed that critical functional important positively-charged residues (K7, K22, K25. K39, K72 K73, and K86) for Apaf-1 and cardiolipin interaction align well with BK residues K606, K627, K630, K643 R631, K684, K685 and K698 (

Figure 1A).

We hypothesized that the linker region between RCK1 and RCK2 may form a structure similar to cytochrome c in the presence of heme, with HMR and M691 serving as axial ligands for the heme iron.

The following experiments are designed to test this hypothesis and to understand the role of the cytochrome c-like structure in the functioning of the BK channel. We focused on the peroxidase activity of the BK channel, as this is an important functional property of cytochrome c. To pharmacologically eliminate the ion-conducting properties of the channels and concentrate our investigation on the enzymatic activity of the gating ring, we supplemented the cell medium with 1 µM of a highly selective and potent BK channel blocker, which has an effective Kd of approximately 10 nM [

60]. This approach ensured that the BK channel conductance was fully blocked while leaving the native ionic conductance unaffected. The strong blockade of the BK channel indicates that the observed peroxidase activity is mediated by its non-conducting properties.

We have demonstrated that the linker region between RCK1-RCK2 domains equips the full BK channel with peroxidase functionality (

Figure 4-6). We tested the contribution of the HRM and M691 residue for heme coordination by this catalytic activity of the gating ring, as well as the full channel (

Figure 6). The mutations H616R and C615S in HRM and M691A mutations reduced enzymatic performance of the channel. These results reinforce the view that a cytochrome-c-like structure that associates heme via the HRM and a second axial ligand (Met-691) is an integral part of BK channels. These results suggest that the inhibitory effect of heme on the BK channel gating is mediated by heme binding to the HRM [

20], as well as to M691.

We observed an interesting appositive effect when the STREX variant was inserted into the linker region (

Figure 6). The stress-regulated exon (STREX) of the BK channel is the most extensively studied splice variant and is highly conserved among vertebrates. This cysteine-rich region leads to significant changes in the BK channel's characteristics, including slower deactivation and a notable leftward shift in the voltage required for half-maximal activation [

58,

61]. The STREX insert interacts with multiple signaling pathways, making it sensitive to inhibition by acute hypoxia and oxidation. This functionality relies on the highly conserved cysteine residues found in the Cys-Ser-Cys (CSC) motif [

62].

STREX is positioned within the linker region adjacent to the HRM. Further investigation is needed to determine how STREX may enhance peroxidase activity and whether the CSC motif plays a role in this process. One potential explanation is that the inclusion of STREX could influence the conformation of the disordered region between RCK1 and RCK2. Additional research may provide more insights into the physiological relevance of the peroxidase activity of the BK channel.

3.2. The Novel Multifunctional Module Within BK Channels

Our data obtained based on bioinformatics and biochemical approaches indicate that the linker region between RCK- RCK2 domains of the BK channel-forming α subunit includes cytochrome c family-like structural elements. These findings proposed that heme binding may be from cytochrome c fold inside the BK channel (

Figure 2B). This region is largely unresolved in reported crystal structures due to its unordered structure [

13,

14,

15,

17]. This part of the channel consists of only a few secondary structure elements, α helices (

Figure 2C). The heme-driven formation of compact cytochrome c fold structure will be associated with a considerably disorder-to-order conformational transition upon heme binding. These structural rearrangements within the gating ring may lie under the structural basis of the heme-dependent modulation activity of the BK channels. Finding a novel heme-sensitive site in the extracellular space of mitoBK suggests that heme may affect BK channel activity through multiple mechanisms [

18].

Beyond that, this region appears responsible for heme-driven regulation of BK channel activity, and may also provide novel performances underlying important physiological functions of these exceptional ion channel proteins, due to similar activities as the “extreme multifunctional” protein cytochrome c [

32].

During the past decade, a fascinating body of experimental investigations has provided evidence that voltage-gated ion channels may do, more than their well-described function in regulating electrical excitability, such as participating in intracellular signaling pathways, in cell behavior. BK channel has been recently shown to play a protective function against ischemia-reperfusion injury both in vitro and in animal models, although the exact mechanism of this protection remains unknown [

43,

44]. It was demonstrated that in the absence of BK, post-anoxic reactive oxygen species production was elevated in mouse cardiomyocyte mitochondria [

45]. While the contribution of the mitochondrial BK channel conductance to this effect is unknown, their ability to break down H

2O

2 may play a part in the protective mechanism of ischemic pre-conditioning.

Here, we report that the human BK channel possesses peroxidase activity as a function of the cytochrome c domain, reinforcing the view that ion channels are more than ion-conducting structures. Notably, since all Amplex Red assay experiments were conducted with performed BK channels (using 1 μM paxillin) [

60], the results emphasize that the peroxidase activity of the BK channel does not rely on its ion-conducting properties. Furthermore, these findings closely replicate the data from our biochemical experiments, which h demonstrate a reduction in peroxidase activity in the gate ring containing the C615S/H616R mutations (

Figure 5). To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of enzymatic activity exhibited by BK channels, and one of the few generally demonstrated in ion channels. Although the full understanding of the physiological functions and implications of this enzymatic activity will require extensive future investigations,

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Expression and Purification of BK-Terminal Proteins

The intracellular C-terminal domain (CTD) (

322IIE…ALK1005) WT, HRM (C615S/H616R) and M691A mutant, as well as CTD including STREX CTD constituent RCK1 (

322IIE...HDP667) and RCK2 (

665HDP…ALK1005) domains, were expressed and purified from

E. coli cells as described previously [

8,

46,

47]. Protein concentrations were estimated using Micro Lowry, Peterson’s Modification (Sigma-Aldrich).

The far-UV spectra of purified whole GR, and its mutant proteins were recorded between 190 and 260 nm by using a quartz cell of 0.1 cm path length. Spectra were collected as an average of 7-9 scans. Secondary structure fractions were calculated using the SMP56 or CLSTR reference set of the CDPro software package [

47,

48]. NRMSD (normalized root mean-square deviation) was used as the measure the goodness of fit to the experimental spectrum.

4.2. ABTS Assay

The peroxidase activity of the WT and mutant human BK channel gating ring was investigated using a colorimetric assay with 2,2’-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate) (ABTS) as an electron donor. Reduced ABTS has a characteristic peak at 340 nm; when the peroxidase-catalyzed reduction of H2O2 to water is coupled to the oxidation of ABTS, an absorbance peak at 415 nm is formed. The reaction mixture (100 μl quartz cuvette) included 20-50 μM ABTS, 10-500 μM H2O2 and 0.1-2 μM BK C-terminus (WT or mutants) complexed with 0.4-8 μM heme. Peroxidase activity was assayed in experiments with a heme concentration of 2 μM

Michaelis-Menten catalytic kinetic parameters were estimated at varying concentrations of substrates (ABTS or H

2O

2) using a two-substraThte Michaelis-Menten kinetic model:

in which

v is the initial rate;

kcat is the intrinsic catalytic activity;

Km

H2O2 and

Km

ABTS are the equilibrium binding constants for H

2O

2 and ABTS, respectively; [Enzyme] is the enzyme concentration, i.e., CytC or the BK CT/heme complex.

4.3. Peroxidase Activity Assay in Cell Lysates

HEK293 cells (ATCC: CRL-1573, kind gifts from Dr. Liqia Toro (UCLA) were transfected with YFP or YFP was fused to the C-terminus of WT or C615S/H161R mutant BK channel constructs using lipofectamine 2000). Cells were grown in the presence of the specific BK channel blocker 1 μM paxilline (PAX). After 72h collected cells were lysed in buffer (50 mM Tris HCI, 2 mM EDTA, pH7.4) in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 1 mM PMFS using sonication (5-10 s) and then centrifuged at 3000g for 5 minutes to clarify the lysates. The expression level of channel proteins was evaluated using the fluorescence intensity of the YFP signal (λext 500 nm/λem 527 nm). Protein concentration was measured using the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Peroxidase activity in the cell lysates was determined using the Amplex Red assay. The assay solution contained 50-100 µg protein samples, 5µM Amplex Red, and various concentrations of H2O2 in 200 µl lysis buffer, and fluorescence of the resorufin, oxidation product of Amplex Red, was detected at emission 580 nm (λext 540nm).

Author Contributions

T Y: Conceptualization, Data curation, supervision, writing –original draft, F. Q. Data curation, Formal Analysis, Software, A. A. Data curation, Resources, Software. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Olcese Riccardo for his incredible support for the research of this manuscript. We would also like to thank former members of Olsese's laboratory Dr. Antonios Pantazis and Dr. Nicoletta Savalli for their colossal contribution in the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hoshi, T.; Pantazis, A.; Olcese, R. Transduction of Voltage and Ca2+Signals by Slo1 BK Channels. Physiology 2013, 28, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J. BK Channel Gating Mechanisms: Progresses Toward a Better Understanding of Variants Linked Neurological Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeverría, F.; Gonzalez-Sanabria, N.; Alvarado-Sanchez, R.; Fernández, M.; Castillo, K.; Latorre, R. Large conductance voltage-and calcium-activated K+ (BK) channel in health and disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1373507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancho, M.; Kyle, B.D. The Large-Conductance, Calcium-Activated Potassium Channel: A Big Key Regulator of Cell Physiology. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusifov, T.; Savalli, N.; Pantazis, A.; Heinemann, S.H.; Hoshi, T.; Olcese, R. Carbon Monoxide May Regulate BK slo1 Channel Activity by Partially Disrupting Heme Coordination. Biophys. J. 2017, 112, 112a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusifov, T.; Javaherian, A.; Gandhi, C.; Olcese, R. Calcium-Dependent Operation of the Human BK Channel Gating Ring Apparatus. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 581a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusifov, T. , Javaherian, AD., Heinemann, SH., Hoshi T., Olcese R. The human BK Channel Gating Ring is a PIP2 Sensor. The human BK Channel Gating Ring is a PIP2 Sensor. Am. Soc. Anesthesiol. Annu. Meet. Pap. ( 2012. [CrossRef]

- Javaherian, A.D.; Yusifov, T.; Pantazis, A.; Franklin, S.; Gandhi, C.S.; Olcese, R. Metal-driven Operation of the Human Large-conductance Voltage- and Ca2+-dependent Potassium Channel (BK) Gating Ring Apparatus. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 20701–20709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazis, A.; Olcese, R. . Biophysics of BK Channel Gating. Int Rev Neurobiol.

- Hou, S.; Heinemann, S.H.; Hoshi, T. Modulation of BKCaChannel Gating by Endogenous Signaling Molecules. Physiology 2009, 24, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, J.; Kalenik, B.; Wrzosek, A.; Szewczyk, A. Redox Regulation of Mitochondrial Potassium Channels Activity. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, T. & S.H. Heinemann. Modulation of BK Channels by Small Endogenous Molecules and Pharmaceutical Channel Openers. (2016). International Review of Neurobiology. [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; MacKinnon, R.; States, U. Molecular structures of the human Slo1 K+ channel in complex with β4. eLife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hite, R.K.; Tao, X.; MacKinnon, R. Structural basis for gating the high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Nature 2016, 541, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Leonetti, M.D.; Hsiung, Y.; MacKinnon, R. Open structure of the Ca2+ gating ring in the high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Nature 2011, 481, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Hite, R.K.; MacKinnon, R. Cryo-EM structure of the open high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Nature 2016, 541, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng Yuan, Manuel D Leonetti, Alexander R Pico, Yichun Hsiung, R. M. Structure of the Human BK Channel Ca2+-Activation Apparatus at 3.0 Å Resolution. Science (80-. ). 182–186 (2010).

- Walewska, A.; Szewczyk, A.; Koprowski, P. External Hemin as an Inhibitor of Mitochondrial Large-Conductance Calcium-Activated Potassium Channel Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horrigan, F.T.; Heinemann, S.H.; Hoshi, T. Heme Regulates Allosteric Activation of the Slo1 BK Channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 2005, 126, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.D.; Xu, R.; Reynolds, M.F.; Garcia, M.L.; Heinemann, S.H.; Hoshi, T. Haem can bind to and inhibit mammalian calcium-dependent Slo1 BK channels. Nature 2003, 425, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, N.; Yang, K.; Coburger, I.; Bernert, A.; Swain, S.M.; Gessner, G.; Kappl, R.; Kühl, T.; Imhof, D.; Hoshi, T.; et al. Intracellular hemin is a potent inhibitor of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv10.1. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.J.; Kapetanaki, S.M.; Chernova, T.; Jamieson, A.G.; Dorlet, P.; Santolini, J.; Moody, P.C.E.; Mitcheson, J.S.; Davies, N.W.; Schmid, R.; et al. A heme-binding domain controls regulation of ATP-dependent potassium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 3785–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Publicover, S.; Gu, Y. An oxygen-sensitive mechanism in regulation of epithelial sodium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 2957–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertini, I. &, Gabriele Cavallaro, A. R. Cytochrome c: occurrence and functions. J Biol Chem. 15194–15200 (2006).

- Kagan, V. E.; et al. Cytochrome c/cardiolipin relations in mitochondria: a kiss of death. Cytochrome c/cardiolipin relations mitochondria a kiss death 1439–1453 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Morgan, J.T.; Ragsdale, S.W. Identification of a Thiol/Disulfide Redox Switch in the Human BK Channel That Controls Its Affinity for Heme and CO. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 20117–20127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence Salkoff, Alice Butler, Gonzalo Ferreira, C. S. & A. W. High-conductance potassium channels of the SLO family. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, C. A.; et al. Cytochrome c nitrite reductase from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans ATCC 27774. The relevance of the two calcium sites in the structure of the catalytic subunit (NrfA). J. Biol. Chem. 1746. [Google Scholar]

- Oubrie, A. , Rozeboom, H. J., Kalk, K. H., Huizinga, E. G. & Dijkstra, B. W. Crystal structure of quinohemoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase from Comamonas testosteroni: Structural basis for substrate oxidation and electron transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3727–3732 (2002).

- Ow, Y.-L.P.; Green, D.R.; Hao, Z.; Mak, T.W. Cytochrome c: functions beyond respiration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, H.B.B.; Elmer-Dixon, M.M.; Rogan, J.T.; Ross, J.B.A.; Bowler, B.E. The Human Cytochrome c Domain-Swapped Dimer Facilitates Tight Regulation of Intrinsic Apoptosis. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 2055–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santucci, R.; Sinibaldi, F.; Cozza, P.; Polticelli, F.; Fiorucci, L. Cytochrome c: An extreme multifunctional protein with a key role in cell fate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 136, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascenzi, P.; Polticelli, F.; Marino, M.; Santucci, R.; Coletta, M. Cardiolipin drives cytochrome c proapoptotic and antiapoptotic actions. IUBMB Life 2011, 63, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belikova, N.A.; Jiang, J.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Zhao, Q.; Epperly, M.W.; Greenberger, J.; Kagan, V.E. Cardiolipin-Specific Peroxidase Reactions of Cytochrome c in Mitochondria During Irradiation-Induced Apoptosis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2007, 69, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, R.; Castillo, K.; Carrasquel-Ursulaez, W.; Sepulveda, R.V.; Gonzalez-Nilo, F.; Gonzalez, C.; Alvarez, O. Molecular Determinants of BK Channel Functional Diversity and Functioning. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 39–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Coghill, L.S.; McClafferty, H.; MacDonald, S.H.-F.; Antoni, F.A.; Ruth, P.; Knaus, H.-G.; Shipston, M.J. Distinct stoichiometry of BK Ca channel tetramer phosphorylation specifies channel activation and inhibition by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004, 101, 11897–11902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipston, M.J. Ion Channel Regulation by Protein Palmitoylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 8709–8716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeudall, S.; Upchurch, C.M.; Leitinger, N. The clinical relevance of heme detoxification by the macrophage heme oxygenase system. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1379967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, Y. A new world of heme function. Pfl?gers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2020, 472, 547–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburger, I.; Yang, K.; Bernert, A.; Wiesel, E.; Sahoo, N.; Swain, S.M.; Hoshi, T.; Schönherr, R.; Heinemann, S.H. Impact of intracellular hemin on N-type inactivation of voltage-gated K+ channels. Pfl?gers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2020, 472, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.A.; Crane, B.R. Effects of interface mutations on association modes and electron-transfer rates between proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005, 102, 15465–15470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraheni, A.D.; Ren, C.; Matsumoto, Y.; Nagao, S.; Yamanaka, M.; Hirota, S. Oxidative modification of methionine80 in cytochrome c by reaction with peroxides. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 182, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N. H.; et al. Inhibition of BKCa negatively alters cardiovascular function. Physiol. Rep. 6, 1–11 (2018).

- Szteyn, K. & Singh, H. Bkca channels as targets for cardioprotection. Antioxidants 9, 1–16 (2020).

- Soltysinska, E.; Bentzen, B.H.; Barthmes, M.; Hattel, H.; Thrush, A.B.; Harper, M.-E.; Qvortrup, K.; Larsen, F.J.; Schiffer, T.A.; Losa-Reyna, J.; et al. KCNMA1 Encoded Cardiac BK Channels Afford Protection against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e103402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusifov, T.; Savalli, N.; Gandhi, C.S.; Ottolia, M.; Olcese, R. The RCK2 domain of the human BK Ca channel is a calcium sensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusifov, T.; Javaherian, A.D.; Pantazis, A.; Gandhi, C.S.; Olcese, R. The RCK1 domain of the human BKCa channel transduces Ca2+ binding into structural rearrangements. J. Gen. Physiol. 2010, 136, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreerama, N. & Woody, R. W. Computation and Analysis of Protein Circular Dichroism Spectra. Methods Enzymol.

- Meredith, A.L. BK Channelopathies andKCNMA1-Linked Disease Models. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2024, 86, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusifov, T.; Qudretova, F.; Aliyeva, A. Role of Bioelectrical Signaling Networks in Tumor Growth. Am. J. Biomed. Life Sci. 2024, 12, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, N.; Goradia, N.; Ohlenschläger, O.; Schönherr, R.; Friedrich, M.; Plass, W.; Kappl, R.; Hoshi, T.; Heinemann, S.H. Heme impairs the ball-and-chain inactivation of potassium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, E4036–E4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.E.J.; Wootton, P.; Mason, H.S.; Bould, J.; Iles, D.E.; Riccardi, D.; Peers, C.; Kemp, P.J. Hemoxygenase-2 Is an Oxygen Sensor for a Calcium-Sensitive Potassium Channel. Science 2004, 306, 2093–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusifov, T.; Savalli, N.; Pantazis, A.; Heinemann, S.H.; Hoshi, T.; Olcese, R. Carbon Monoxide May Regulate BK slo1 Channel Activity by Partially Disrupting Heme Coordination. Biophys. J. 2017, 112, 112a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggar, J.H.; Li, A.; Parfenova, H.; Liu, J.; Umstot, E.S.; Dopico, A.M.; Leffler, C.W. Heme Is a Carbon Monoxide Receptor for Large-Conductance Ca 2+ -Activated K + Channels. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Morgan, J.T.; Ragsdale, S.W. Identification of a Thiol/Disulfide Redox Switch in the Human BK Channel That Controls Its Affinity for Heme and CO. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 20117–20127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, J.; Wasson, J.; Salkoff, L.; Permutt, M.A. Cloning of human pancreatic islet large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (hSlo) cDNAs: evidence for high levels of expression in pancreatic islets and identification of a flanking genetic marker. Diabetologia 1996, 39, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Nelson, C.; Salkoff, L.; Lingle, C.J. A Cysteine-rich Domain Defined by a Novel Exon in aSlo Variant in Rat Adrenal Chromaffin Cells and PC12 Cells. 1997, 272, 11710–11717. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; McCobb, D.P. Control of Alternative Splicing of Potassium Channels by Stress Hormones. Science 1998, 280, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, M.J.; Cresser-Brown, J.; Thomas, M.; Portolano, N.; Basran, J.; Freeman, S.L.; Kwon, H.; Bottrill, A.R.; Llansola-Portoles, M.J.; Pascal, A.A.; et al. Discovery of a heme-binding domain in a neuronal voltage-gated potassium channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 13277–13286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lingle, C.J. Paxilline inhibits BK channels by an almost exclusively closed-channel block mechanism. J. Gen. Physiol. 2014, 144, 415–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipston, M. J. , & Tian, L. (2016). Posttranscriptional and Posttranslational Regulation of BKChannels. ( 128, 91–126. [CrossRef]

- McCartney, C.E.; McClafferty, H.; Huibant, J.-M.; Rowan, E.G.; Shipston, M.J.; Rowe, I.C.M. A cysteine-rich motif confers hypoxia sensitivity to mammalian large conductance voltage- and Ca-activated K (BK) channel α-subunits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005, 102, 17870–17876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, W.-Y. , Shiu, J.-H., Tsai, Y.-H., Chuang, W.-J (2003) Solution Structure of Reduced Recombinant Human Cytochrome c. [CrossRef]

- Baistrocchi, P.; Banci, L.; Bertini, I.; Turano, P.; Bren, K.L.; Gray, H.B. Three-Dimensional Solution Structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Reduced Iso-1-cytochrome c. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 13788–13796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurizzo, D.; Silvestrini, M.-C.; Mathieu, M.; Cutruzzolà, F.; Bourgeois, D.; Fülöp, V.; Hajdu, J.; Brunori, M.; Tegoni, M.; Cambillau, C. N-terminal arm exchange is observed in the 2.15 Å crystal structure of oxidized nitrite reductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Structure 1997, 5, 1157–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oubrie, A.; Rozeboom, H.J.; Kalk, K.H.; Huizinga, E.G.; Dijkstra, B.W. Crystal Structure of Quinohemoprotein Alcohol Dehydrogenase from Comamonas testosteroni. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 3727–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, A.; Kim, J.-K.; Miyahara, I.; Devreese, B.; Vandenberghe, I.; Hacisalihoglu, A.; Okajima, T.; Kuroda, S.; Adachi, O.; Duine, J.A.; et al. Crystal Structure of Quinohemoprotein Amine Dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas putida. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 2830–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).