Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

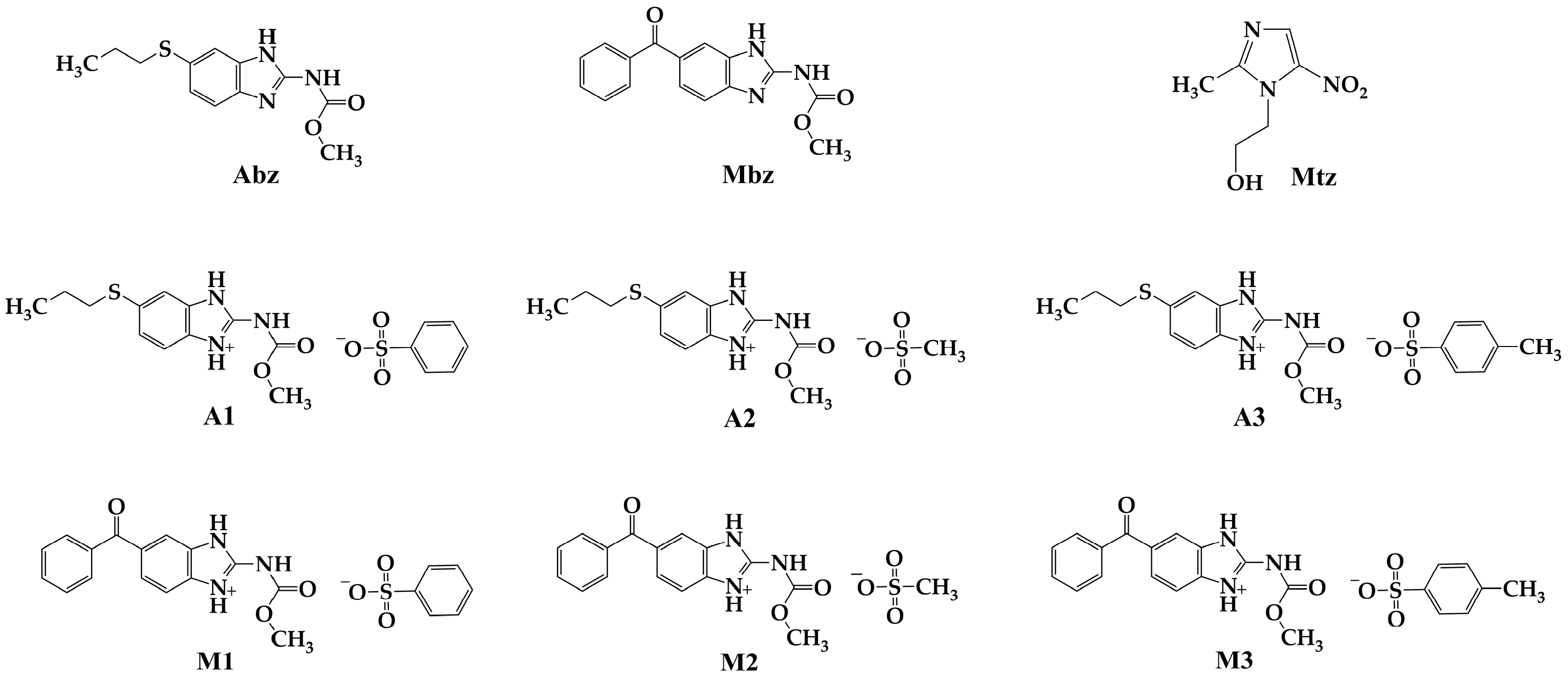

2.1. General Procedure to Prepare Abz and Mbz Sulfonic Salts

2.1.1. Reagents and Solvents

2.1.2. Equipment and Conditions for Chemical Characterization

2.1.3. General Method for Salts Preparation

2.1.4. Chemical Characterization of Salt A1 (Albendazole Besylate)

2.1.5. Chemical Characterization of Salt A2 (Albendazole Mesylate)

2.1.6. Chemical Characterization of Salt A3 (Albendazole Tosylate)

2.1.7. Chemical Characterization of Salt M1 (Mebendazole Besylate)

2.1.8. Chemical Characterization of Salt M2 (Mebendazole Mesylate)

2.1.9. Chemical Characterization of Salt M3 (Mebendazole Tosylate)

2.2. In Vitro Antiprotozoal Activity Assays

2.2.1. Stock Solutions

2.2.2. Trophozoite Culture Conditions

2.2.3. In Vitro Antiparasitic Activity Tests

2.3. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assays

2.3.1. Cell Line Culture Conditions

2.3.2. Cytotoxicity Assays

2.3.3. Selectivity Index (SI)

3. Results

3.1. In Vitro Antiparasitic Activity

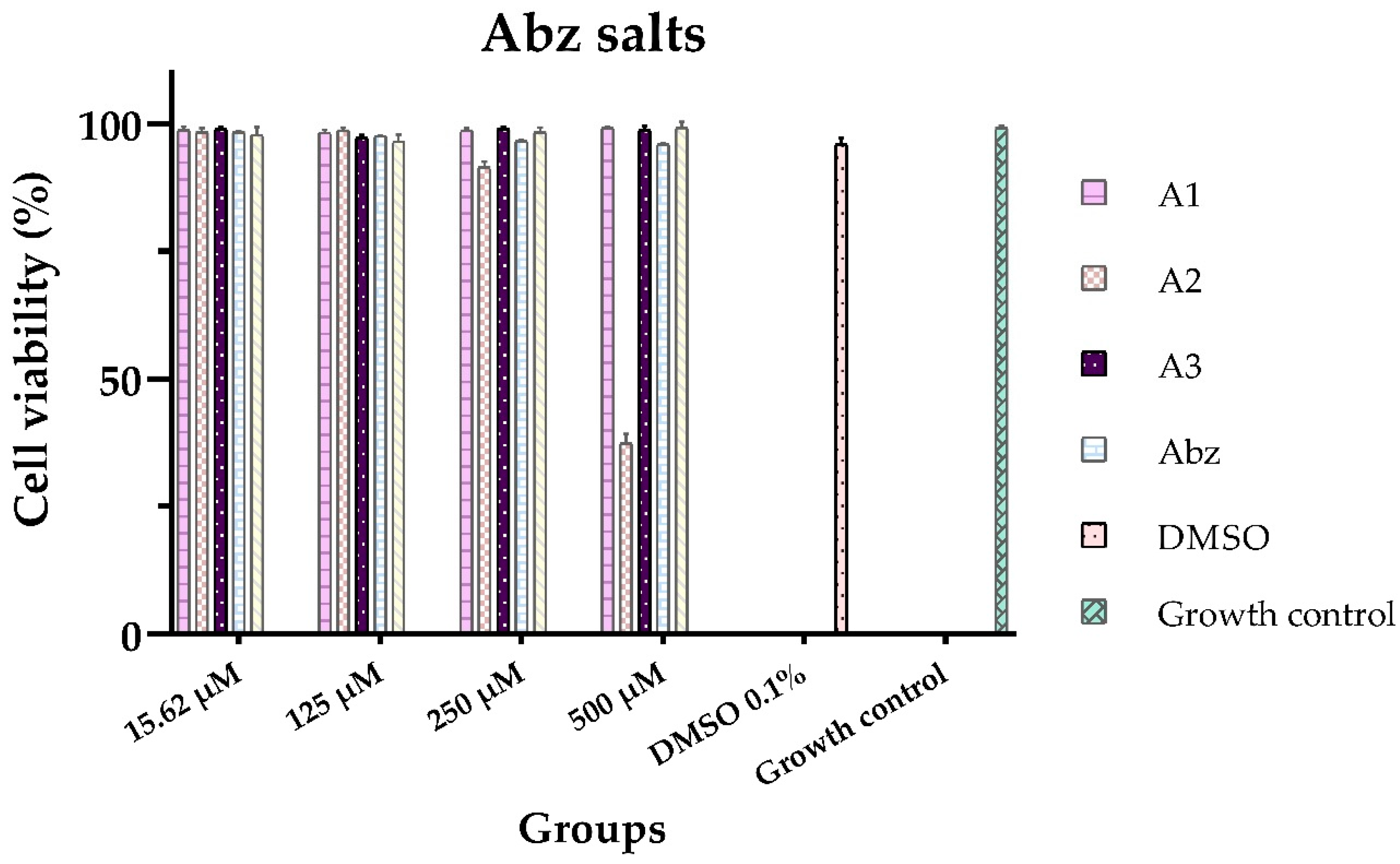

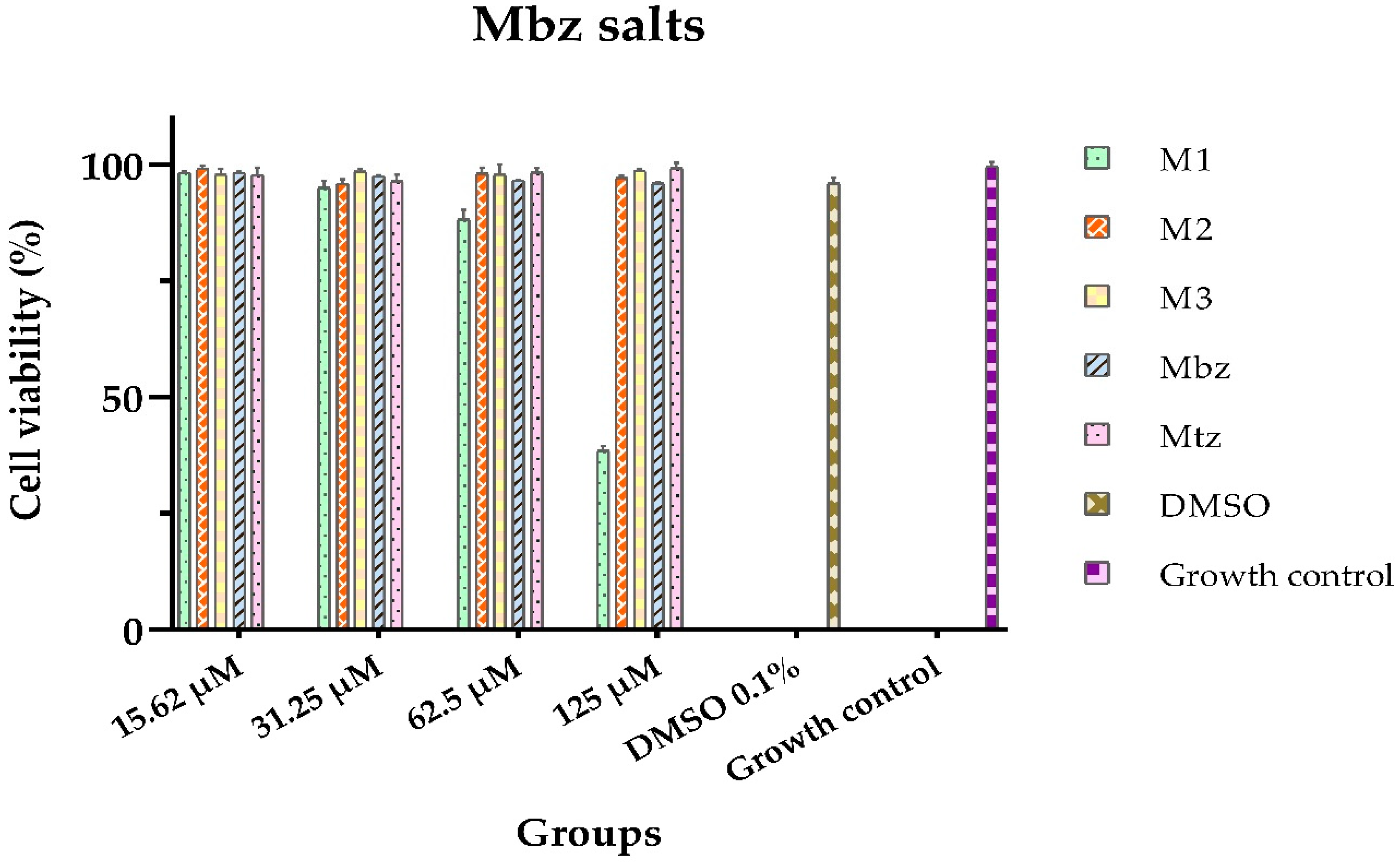

3.2. In Vitro Cytotoxicity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABZ | Albendazole |

| API | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient |

| CC50 | Cytotoxic Concentration 50% |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| IC50 | Inhibitory Concentration 50% |

| MBZ | Mebendazole |

| MTZ | Metronidazole |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| OTC | Over the counter |

| PXRD | Powder X-ray Diffraction |

| SI | Selectivity Index |

| %CV | Cell Viability percentage |

References

- Flores-Carrillo, P.; Velázquez-López, J.M.; Aguayo-Ortiz, R.; Hernández-Campos, A.; Trejo-Soto, P.J.; Yépez-Mulia, L.; Castillo, R. Synthesis, antiprotozoal activity, and chemoinformatic analysis of 2-(methylthio)-1H-benzimidazole-5-carboxamide derivatives: Identification of new selective giardicidal and trichomonicidal compounds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 137, 211-220. [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, A.; Müller, N.; Müller, J. Comparative Pathobiology of the Intestinal Protozoan Parasites Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium parvum. Pathogens 2019, 8, 116. [CrossRef]

- Leitsch, D. Drug susceptibility testing in microaerophilic parasites: Cysteine strongly affects the effectivities of metronidazole and auranofin, a novel and promising antimicrobial. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2017, 7, 321-327.

- Daneman, N.; Cheng, Y.; Gomes, T.; Guan, J.; Mamdani, M. M.; Saxena, F. E.; Juurlink, D. N. Metronidazole-associated Neurologic Events: A Nested Case-control Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021, 72, 2095–2100.

- Löfmark, S.; Edlund, C.; Nord, C. E. Metronidazole is still the drug of choice for treatment of anaerobic infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2010, 50, 16–23. [CrossRef]

- Gonzales ,M.L.M.; Dans, L.F.; Sio-Aguilar, J. Antiamoebic drugs for treating amoebic colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1, CD006085. [CrossRef]

- Wongstitwilairoong, B.; Anothaisintawee, T.; Ruamsap, N.; Lertsethtakarn, P.; Kietsiri, P.; Oransathid, W.; Oransathid, W.; Gonwong, S.; Silapong, S.; Suksawad, U.; et al. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infections, Genotypes, and Drug Susceptibility of Giardia lamblia among Preschool and School-Aged Children: A Cross-Sectional Study in Thailand. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 394. [CrossRef]

- Farbey, M.D.; Reynoldson, J.A.; Thompson, R.C. In vitro drug susceptibility of 29 isolates of Giardia duodenalis from humans as assessed by an adhesion assay. Int J Parasitol. 1995, 25, 593–9.

- Lemée, V.; Zaharia, I.; Nevez, G.; Rabodonirina, M.; Brasseur, P.; Ballet, J. J.; Favennec, L. Metronidazole and albendazole susceptibility of 11 clinical isolates of Giardia duodenalis from France. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000, 46, 819-821. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, D.; Sehgal, R.; Chawla, Y.; Mahajan, R.C.; Malla, N. In vitro activity of antiamoebic drugs against clinical isolates of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2004, 3, 27. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Banerjee, T.; Shukla, S. K.; Upadhyay, S.; Verma, A. Creep in nitroimidazole inhibitory concentration among the Entamoeba histolytic isolates causing amoebic liver abscess and screening of andrographolide as a repurposing drug. Sci Rep. 2023,13, 12192. [CrossRef]

- Alves, M. S. D.; das Neves, R. N.; Sena-Lopes, Â.; Domingues, M.; Casaril, A. M.; Segatto, N. V.; Nogueira, T. C. M.; de Souza, M. V. N.; Savegnago, L.; Seixas, F. K.; Collares, T.; Borsuk, S. Antiparasitic activity of furanyl N-acylhydrazone derivatives against Trichomonas vaginalis: in vitro and in silico analyses. Parasit Vectors. 2020, 13,1, 59. [CrossRef]

- Mabaso, N.; Abbai, N. Distribution of genotypes in relation to metronidazole susceptibility patterns in Trichomonas vaginalis isolated from South African pregnant women. Parasitol Res, 2021, 120, 2233–2241. [CrossRef]

- Mørch, K.; Hanevik, K.; Robertson, L. J.; Strand, E. A.; Langeland, N. Treatment-ladder and genetic characterisation of parasites in refractory giardiasis after an outbreak in Norway. J Infect. 2008, 56, 268–273. [CrossRef]

- Speich, B.; Marti, H.; Ame, S.M.; Ali, S.M.; Bogoch, I.I.; Utzinger, J.; Albonico, M.; Keiser, J. Prevalence of intestinal protozoa infection among school-aged children on Pemba Island, Tanzania, and effect of single-dose albendazole, nitazoxanide and albendazole-nitazoxanide. Parasit Vectors, 2013, 4, 6-3. [CrossRef]

- Leitsch, D. Drug Resistance in the Microaerophilic Parasite Giardia lamblia. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2015, 2, 128-135. [CrossRef]

- Yereli, K.; Balcioğlu, I. C.; Ertan, P.; Limoncu, E.; Onağ, A. Albendazole as an alternative therapeutic agent for childhood giardiasis in Turkey. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004, 10, 527–529. [CrossRef]

- Anichina, K.; Mavrova, A.; Vuchev, D. Benzimidazoles Containing Piperazine Skeleton at C-2 Position as Promising Tubulin Modulators with Anthelmintic and Antineoplastic Activity. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1518. [CrossRef]

- Juliano, C.; Monaco, G.; Bandiera, P., Tedde, G., Cappuccinelli, P. Action of anticytoskeletal compounds on in vitro cytopathic effect, phagocytosis, and adhesiveness of Trichomonas vaginalis. Genitourin Med. 1987, 63, 256–263. [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, S.K.; Gordon, V.R.; McLaughlin, G.L.; Edlind, T.D. Antiprotozoal activities of benzimidazoles and correlations with beta-tubulin sequence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994, 38, 2086-2090. [CrossRef]

- Benchimol, M.; Gadelha, A. P.; De Souza, W. Ultrastructural Alterations of the Human Pathogen Giardia intestinalis after Drug Treatment. Pathogens, 2023,12, 810. [CrossRef]

- Bártíková, H.; Vokřál, I.; Skálová, L.; Lamka, J.; Szotáková, B. Metabolismo oxidativo in vitro de xenobióticos en la duela de lanceta (Dicrocoelium dendriticum) y los efectos del albendazol y el sulfóxido de albendazol ex vivo. Xenobiotica, 2010, 4, 593–601. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Espinosa, R.; Argüello-García, R.; Saavedra, E.; Ortega-Pierres, G. Albendazole induces oxidative stress and DNA damage in the parasitic protozoan Giardia duodenalis. Front Microbiol. 2015, 6, 800. [CrossRef]

- Buchter, V.; Priotti, J.; Leonardi, D.; Lamas, M. C.; Keiser, J. Preparation, Physicochemical Characterization and In Vitro and In Vivo Activity Against Heligmosomoides polygyrus of Novel Oral Formulations of Albendazole and Mebendazole. J Pharm Sci. 2020, 109, 1819–1826. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhiyuan, Z.; Ding, C.; Shufeng, X.; Zhe, Xu. “The Use of Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes to Increase the Solubility and Pharmacokinetic Profile of Albendazole”. Molecules, 2023, 28, 21: 7295. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Chen, M.; Yan, Y.; Chen, D.; Xie, S. Nanocrystal Suspensions for Enhancing the Oral Absorption of Albendazole. Nanomaterials. 2022,12, 3032. [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, N.; Sadr, S.; Santucciu, C.; Rahdar, A.; Masala, G.; Borji, H. Evaluation of the In-Vitro Effects of Albendazole, Mebendazole, and Praziquantel Nanocapsules against Protoscolices of Hydatid Cyst. Pathogens, 2024, 13, 790. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Kawakami, K.; Fukiage, M.; Oikawa, M.; Nishida, Y.; Matsuda, M.; Fujita, T. Relevance of Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation of Supersaturated Solution in Oral Absorption of Albendazole from Amorphous Solid Dispersions. Pharmaceutics, 2020,13, 220. [CrossRef]

- Fateh, R.; Norouzi, R.; Mirzaei, E.; Nissapatron, V.; Nawaz, M.; Khalifeh-Gholi, M.; Hamta, A.; Adnani Sadati, S. J.; Siyadatpanah, A.; Fattahi Bafghi, A. In vitro evaluation of albendazole nanocrystals against Echinococcus granulosus protoscolices. Ann Parasitol. 2021, 67, 203–212. [CrossRef]

- Castro Alpízar, J.A.; Vargas Monge, R.; Madrigal Redondo, G.; Pacheco Molina, J.A. Development of novel microstructured lipid carriers for dissolution rate enhancement of albendazole. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2020, 12, 173–178.

- Eriksen, J.B.; Christensen, S.B.; Bauer-Brandl, A.; Brandl, M. Dissolution/permeation of albendazole in the presence of cyclodextrin and bile salts: A mechanistic in-vitro study into factors governing oral bioavailability. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 111, 1667–1673.

- Pacheco, P.A.; Rodrigues, L.N.C.; Ferreira, J.F.S.; Gomes, A.C.P.; Veríssimo, C.J.; Louvandini, H.; Costa, R.L.D.; Katiki, L.M. Inclusion complex and nanoclusters of cyclodextrin to increase the solubility and efficacy of albendazole. Parasitol. Res. 2018,117, 705–712.

- Meena, A.K.; Sharma, K.; Kandaswamy, M.; Rajagopal, S.; Mullangi, R. Formulation development of an albendazole self-emulsifying drug delivery system (SEDDS) with enhanced systemic exposure. Acta Pharm. 2012, 62, 563–580.

- Bolla, G.; Nangia, A. Novel pharmaceutical salts of albendazole. Cryst Eng Comm. 2018, 20, 6394- 6405.

- Elder, D. P.; Delaney, E.; Teasdale, A.; Eyley, S.; Reif, V. D.; Jacq, K.; Facchine, K. L.; Oestrich, R. S.; Sandra, P.; David, F. The utility of sulfonate salts in drug development. J Pharm Sci., 2010, 99, 2948–2961. [CrossRef]

- Thackaberry, E. A. Non-clinical toxicological considerations for pharmaceutical salt selection. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012, 8, 1419–1433. [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, R.K.; Kanfer, I.; Walker, R.B. Generic substitution: The use of medicinal products containing different salts and implications for safety and efficacy. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2006, 28, 1–6.

- Emmerson, J.L.; Gibson, W.R.; Anderson, R.C. Acute toxicity of propoxyphene salts. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1971, 19, 445–451.

- Duque-Montaño, B. E.; Gómez-Caro, L. C.; Sanchez-Sanchez, M.; Monge, A.; Hernández-Baltazar, E.; Rivera, G.; Torres-Angeles, O. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of new ethyl and methyl quinoxaline-7-carboxylate 1,4-di-N-oxide against Entamoeba histolytic. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013, 21, 4550-4558. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ochoa, B.; Martínez-Rosas, V.; Morales-Luna, L.; Calderón-Jaimes, E.; Rocha-Ramírez, L.M.; Ortega-Cuellar, D.; Rufino-González, Y.; González-Valdez, A.; Arreguin-Espinosa, R.; Enríquez-Flores, S.; et al. Pyridyl Methylsulfinyl Benzimidazole Derivatives as Promising Agents against Giardia lamblia and Trichomonas vaginalis. Molecules, 2022, 27, 8902. [CrossRef]

- Carapina da Silva, C.; Silveira P.R.; Nascimento das Neves, R.; Dié Alves, M.S.; Sena-Lopes, A.; Moura, S., Borsuk, S.; Pereira de Pereira, C.M. Antiparasitic activity of synthetic curcumin monocarbonyl analogues against Trichomonas vaginalis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 367- 377. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, V. I. G. Actividad anti-Giardia in vitro de los compuestos de Foeniculum vulgare y Citrus aurantifolia. Master’s Thesis, Autonomous University of Nuevo León, 2015.

- Quispe, A.; Zavala, D.; Rojas, J.; Posso, M.; Vaisberg, A. Efecto citotóxico selectivo in vitro de Muricin H (Acetogenina de Annona muricata) en cultivos celulares de cáncer de pulmón. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2006, 23, 265-269.

- Ortiz, L.J.C.; Balderrabano, L. A. Importancia de las sales orgánicas en la industria farmacéutica. Rev Mex Cienc Farm. 2017, 48, 18- 42.

- Silva, D.; Lopes, M.V.C.; Petrovski, Ž.; Santos, M.M.; Santos, J.P.; Yamada-Ogatta, S.F.; Bispo, M.L.F.; de Souza, M.V.N.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Lourenço, M.C.S.; et al. Novel Organic Salts Based on Mefloquine: Synthesis, Solubility, Permeability, and In Vitro Activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Molecules 2022, 27, 5167. [CrossRef]

- Madeira, D.; Alves, C.; Silva, J.; Florindo, C.; Costa, A.; Petrovski, Ž.; Marrucho, I.M.; Pedrosa, R.; Santos, M.M.; Branco, L.C. Fluoroquinolone-Based Organic Salts and Ionic Liquids as Highly Bioavailable Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobials. Proceedings 2021, 78, 3. [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, R.; Santarém, N.; Santos, A.F.M.; Jacinto, M.L.; Cordeiro-da-Silva, A.; Prudêncio, C.; Noronha, J.P.; Branco, L.C.; Petrovski, Ž. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Amphotericin B Formulations Based on Organic Salts and Ionic Liquids against Leishmania infantum. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1841. [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, R.; Silva, D.; Dias, A.R.; Dias, V.; Santos, M.M.; Pinheiro, L.; Prudêncio, C.; Noronha, J.P.; Petrovski, Ž.; Branco, L.C. Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity of Ionic Liquids and Organic Salts Based on Penicillin G and Amoxicillin hydrolysate Derivatives against Resistant Bacteria. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 221. [CrossRef]

- Mesallati, H.; Umerska, A.; Paluch, K.J.; Tajber, L. Amorphous Polymeric Drug Salts as Ionic Solid Dispersion Forms of Ciprofloxacin. Mol. Pharm. 2017, 14, 2209–2223.

- Mesallati, H.; Umerska, A.; Tajber, L. Fluoroquinolone Amorphous Polymeric Salts and Dispersions for Veterinary Uses. Pharmaceutics. 2019, 11, 268. [CrossRef]

- Angeles, R.G.M. Evaluación del efecto de los compuestos benzimidazolicos, CMC- 12, CMC- 19 y CMC- 20, sobre los niveles de transcripción de proteínas del metabolismo energético y del citoesqueleto de Giardia duodenalis. PhD. Thesis. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico city, 2014. https://ru.dgb.unam.mx/bitstream/20.500.14330/TES01000708272/3/0708272.pdf.

- Espinosa, C. M.; Martínez P. A. The plasma membrane of Entamoeba histolytica: structure and dynamics. Biology of the cell. 1991, 72, 189-200.

- Ibáñez, E.A.; Gómez, B.A. Trichomonas vaginalis: The versatility of a tenacious parasite. An Real Acad Farm. 2017, 83, 1, 10-47.

- Saal, C. and Becker, A. Pharmaceutical salts: A summary on doses of salt formers from the Orange Book. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017, 49, 4, 614-623. [CrossRef]

- Florindo, C.; Costa, A.; Matos, C.; Nunes, S.L.; Matias, A.N.; Duarte, C.M.M.; Rebelo, L.P.N.; Branco, L.C.; Marrucho, I.M. Novel organic salts based on fluoroquinolone drugs: Synthesis, bioavailability and toxicological profiles. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 469, 179–189.

- Camacho, M. D. R., Phillipson, J. D., Croft, S. L., Solis, P. N., Marshall, S. J., Ghazanfar, S. Screening of plant extracts for antiprotozoal and cytotoxic activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 89, 185–191.

| Antiparasitic activity | |||

| Compound |

E. histolytica IC50 [µM] |

G. lamblia IC50 [µM] |

T. vaginalis IC50 [µM] |

| A1 | N. E.4 | 138.02 ± 1.41 | N. E.4 |

| A2 | 37.95 ± 0.72 | 78.05 ± 0.43 | 125.53 ± 1.80 |

| A3 | 39.93 ± 0.81 | 51.31 ± 1.23 | N. E.4 |

| M1 | 128.05 ± 2.69 | N. E.4 | 24.17 ± 0.15 |

| M2 | 57.72 ± 0.70 | 79.62 ± 0.99 | 49.86 ± 0.80 |

| M3 | 44.34 ± 0.45 | 77.98 ± 0.70 | 62.59 ± 1.44 |

| Abz1 | 73.51 ± 1.09 | 270.66 ± 1.89 | 211.71 ± 2.18 |

| Mbz2 | 59.81 ± 1.18 | 262.74 ± 2.49 | 36.59 ± 0.69 |

| Mtz3 | 16.08 ± 0.69 | 97.63 ± 1.43 | 16.16 ± 0.66 |

| Cytotoxic activity | |

| Salt | CC50 (µM) |

| A1 | > 500 |

| A2 | 435.46 ± 2.17 |

| A3 | > 500 |

| M1 | 104.04 ± 3.85 |

| M2 | > 500 |

| M3 | > 500 |

| Abz | > 500 |

| Mbz | > 500 |

| Mtz | > 500 |

| Selectivity Index | |||

| Salt | E. histolytica | G. lamblia | T. vaginalis |

| A1 | N. E.1 | 3.62 | N. E.1 |

| A2 | 11.47 | 5.57 | 3.46 |

| A3 | 12.52 | 9.74 | N. E.1 |

| M1 | 0.81 | N. E.1 | 4.30 |

| M2 | 8.66 | 6.27 | 10.02 |

| M3 | 11.27 | 6.41 | 7.98 |

| Abz | 6.80 | 1.84 | 2.36 |

| Mbz | 8.35 | 1.90 | 13.66 |

| Mtz | 31.09 | 5.12 | 30.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).