Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

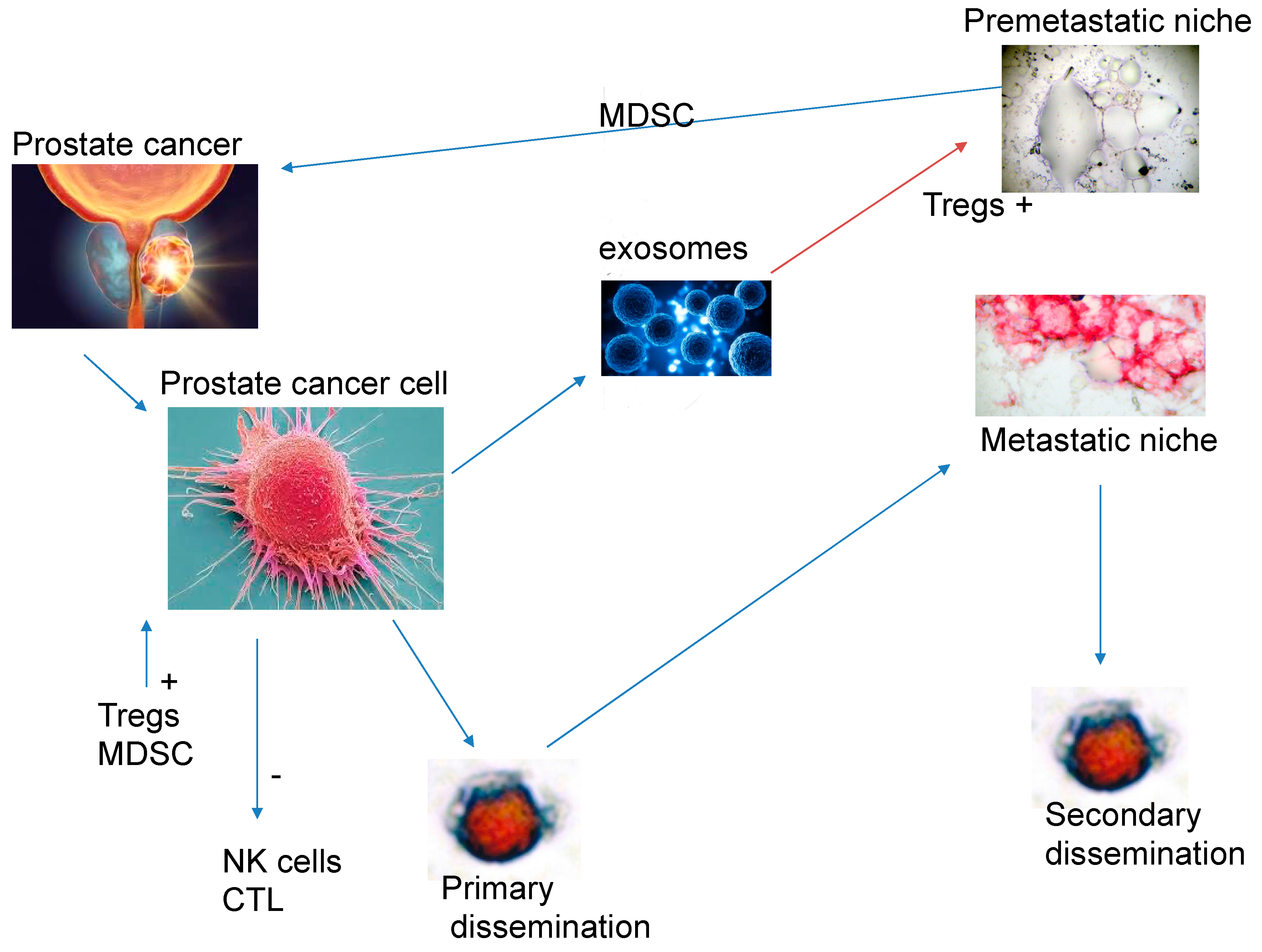

Modulation of the Immune System by the Primary Tumour

The Role of Immunotherapy and Immunomodulation

Bispecific Antibodies That Target Costimulatory Recpetors of T-Cells

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-Cell Therapy

PMSA Linked Radionuclides

Androgen Deprevation Therapy

Should Immunotherapy Be Used as Frontline Treatment for Biochemical Relapse? Are We Not Seeing the Woods for the Trees?

Future Developments and the Use of Immunotherapy in Patients with Prostate Cancer

References

- Sridaran, D.; Bradshaw, E.; DeSelm, C.; Pachynski, R.; Mahajan, K.; Mahajan, N.P. Prostate cancer immunotherapy: Improving clinical outcomes with a multi-pronged approach. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel RI, Miller KD, JemalA, 2018 Cancer Statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68: 7-30.

- Nelson, P.S. Molecular States Underlying Androgen Receptor Activation: A Framework for Therapeutics Targeting Androgen Signaling in Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 644–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, M.C.; Li, J.; Klink, J.C.; Kattan, M.W.; Klein, E.A.; Stephenson, A.J. Optimal Definition of Biochemical Recurrence After Radical Prostatectomy Depends on Pathologic Risk Factors: Identifying Candidates for Early Salvage Therapy. Eur. Urol. 2013, 66, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, M.; Hanks, G.; Thames, H.; Schellhammer, P.; Shipley, W.U.; Sokol, G.H.; Sandler, H. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: Recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006, 65, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.G.; Croce, C.M.; Fischer, R.; Monne, M.; Vihko, P.; Mulholland, S.G.; Gomella, L.G. Detection of hematogenous micrometastasis in patients with prostate cancer. 1992, 52, 6110–6112.

- Murray NP, Reyes E, Orellana N, Fuentealba, C., Jacob, O. Head to head of the Chun Nomogram, percentago free PSA and primary circulating postate cells to predict thew presence of prostate cancer at repeat biopsy. APJACPn2016; 17: 2559-2563.

- Chang YS, di Tomaso E, McDonald DM, Jone R, Jasin RK, Munn LL. Mosaic blood vessels in tumors: Frequency of cancer cells in contact with flowing blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 14608-14613.

- Fidler, I.J. Metastasis: Quantitative Analysis of Distribution and Fate of Tumor Emboli Labeled With 125I-5-Iodo-2′ -deoxyuridine23. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1970, 45, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song H, Weinstein HNW, Allegakoen P, Wadsworth II MH, Xie J, Yang H,Castro EA, Lu L, Stohr BA, Feny FY,et al. Single-cell analysis of human. Primary prostate cancer reveals the heterogeneity of tumor-associated epithlial cell states. Nat Commun 2022; 13: 141.

- Paget, S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Lancet 1889, 133, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fildler IJ, Poste, G. The “seed And soli” hypothesis revisited. Lancet Oncol 2008; 9; 8.

- Luo, W. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma ecology theory: Cancer as multidimensional spatiotemporal “unity of ecology and evolution” pathological ecosystem. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1607–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Song, E. The theory of tumour ecosystem. Cancer Commun 2022; 42: 587-608.

- Adorno Febles VR, Hao Y, Ahsan A, Wu J, Qian Y, Zhong H,Loeb S, Makova AV, Lepor, A., Wysock J et al. Single-cell analysis of localized prostate cancer patients links high Gleason score with an immunosuppressive profile Prostate 2023; 83: 840-849.

- Vidotto, T.; Saggioro, F.P.; Jamaspishvili, T.; Chesca, D.L.; de Albuquerque, C.G.P.; Reis, R.B.; Graham, C.H.; Berman, D.M.; Siemens, D.R.; Squire, J.A.; et al. PTEN-deficient prostate cancer is associated with an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment mediated by increased expression of IDO1 and infiltrating FoxP3+ T regulatory cells. Prostate 2019, 79, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenzer, M.; Keß, P.; Nientiedt, C.; Endris, V.; Kippenberger, M.; Leichsenring, J.; Stögbauer, F.; Haimes, J.; Mishkin, S.; Kudlow, B.; et al. The BRCA2 mutation status shapes the immune phenotype of prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2019, 68, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eble, J.A.; Niland, S. The extracellular matrix in tumor progression and metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2019, 36, 171–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross JS, Kaur, P.Sheehan CE, Fisher HA, Kaufman RA Jr, Kallakury BV. Prognostic significance of metalloproteinase 2 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 expression in prostate cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2003, 16, 198–205.

- Trudel, D.; Fradet, Y.; Meyer, F.; Harel, F.; Têtu, B. Significance of MMP-2 expression in prostate cancer: An immunohistochemical study. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 8511–8515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nissinen, L., Kahari VM. MMPs in inflammation. Biochem Biophys Acta 2014; 1840: 2571-2580.

- Lee BK, Kim MJ, Jang HS, Lee HR, Ahn KM, Lee JH, Choung PH, Kim MJ et al. High concentrations of MMP-2 and MMP-9 reduce NK mediated cytotoxicity against oral squamous cell carcinoma line. In Vivo 2008; 22: 593-598.

- Kahlert C, Kalluri R Exosomes in tumor microenvironment influence cancer progression and metastasis. J Mol Med 2013; 91: 431-437.

- Hoshino, A.; Costa-Silva, B.; Shen, T.-L.; Rodrigues, G.; Hashimoto, A.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; Kohsaka, S.; Di Giannatale, A.; Ceder, S.; et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 2015, 527, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syn, N.; Wang, L.; Sethi, G.; Thiery, J.-P.; Goh, B.-C. Exosome-Mediated Metastasis: From Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition to Escape from Immunosurveillance. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 37, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, X.; Poliakov, A.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Z.-B.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Z.; Shah, S.V.; Wang, G.-J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by tumor exosomes. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 124, 2621–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, S.M.; Zhang, F.; Ding, C.; Montoya-Durango, D.E.; Hu, X.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, F.; Fox, M.; Zhang, H.-G.; et al. Tumor-derived exosomes drive immunosuppressive macrophages in a pre-metastatic niche through glycolytic dominant metabolic reprogramming. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 2040–2058.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieckowski, E.U.; Visus, C.; Szajnik, M.; Szczepanski, M.J.; Storkus, W.J.; Whiteside, T.L. Tumor-Derived Microvesicles Promote Regulatory T Cell Expansion and Induce Apoptosis in Tumor-Reactive Activated CD8+ T Lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 3720–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiro F, Muller L, Funk S, Jackson EK, Battastini AM, Whiteside TL. Phenotypic and functional characteristics of CD39 high human regulatory B-cells (Breg) Oncoimmunology 2016; 5:e1082703.

- Schuler, P.J.; Saze, Z.; Hong, C.-S.; Muller, L.; Gillespie, D.G.; Cheng, D.; Harasymczuk, M.; Mandapathil, M.; Lang, S.; Jackson, E.K.; et al. Human CD4+CD39+ regulatory T cells produce adenosine upon co-expression of surface CD73 or contact with CD73+ exosomes or CD73+ cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014, 177, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Poliakov, A.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Z.-B.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Z.; Shah, S.V.; Wang, G.-J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by tumor exosomes. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 124, 2621–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D.A.; Bakouny, Z.; Hirsch, L.; Flippot, R.; Van Allen, E.M.; Wu, C.J.; Choueiri, T.K. Beyond conventional immune-checkpoint inhibition—Novel immunotherapies for renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhea LP, Mendez-Marti S, Kim D, Aragon-Ching JB. Role of immunotherapy in bladder cancer. Cancer Treat Res Commun 2021;26: 100296.

- Bansal, D.; Reimers, M.A.; Knoche, E.M.; Pachynski, R.K. Immunotherapy and Immunotherapy Combinations in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movassaghi, M.; Chung, R.; Anderson, C.B.; Stein, M.; Saenger, Y.; Faiena, I. Overcoming Immune Resistance in Prostate Cancer: Challenges and Advances. Cancers 2021, 13, 4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galon, J.; Bruni, D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, S.; Subudhi, S.K.; Aparicio, A.; Ge, Z.; Guan, B.; Miura, Y.; Sharma, P. Differences in Tumor Microenvironment Dictate T Helper Lineage Polarization and Response to Immune Checkpoint Therapy. Cell 2019, 179, 1177–1190.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Campos, F.; Gajate, P.; Romero-Laorden, N.; Zafra-Martín, J.; Juan, M.; Polo, S.H.; Moreno, A.C.; Couñago, F. Immunotherapy in Advanced Prostate Cancer: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantoff, P.W.; Higano, C.S.; Shore, N.D.; Berger, E.R.; Small, E.J.; Penson, D.F.; Redfern, C.H.; Ferrari, A.C.; Dreicer, R.; Sims, R.B.; et al. Sipuleucel-T Immunotherapy for Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in prostate cancer version 1:2023. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx (accessed on November 2024).

- McNeel DG, Bander NH,, Beer TM, Drake CG, Fang L, Harrelson S, Kanttoff PV, Mdan RA, Oh WK et al. The Society for Immunotherapy for the treatment of prostate carcinoma. J Immunother cancer 2016; 4: 92.

- Cookson, M.S.; Roth, B.J.; Dahm, P.; Engstrom, C.; Freedland, S.J.; Hussain, M.; Lin, D.W.; Lowrance, W.T.; Murad, M.H.; Oh, W.K.; et al. Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: AUA Guideline. J. Urol. 2013, 190, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Loblaw, D.A.; Oliver, T.K.; Carducci, M.; Chen, R.C.; Frame, J.N.; Garrels, K.; Hotte, S.; Kattan, M.W.; Raghavan, D.; et al. Systemic Therapy in Men With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Cancer Care Ontario Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 3436–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker C, Gillessen S, Heidenreich A, Horwich A: ESMO Guidelines Committee. Cancer of the prostate : ESMO guidelines clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and followup. Ann Oncol 2015; 26 (suppl 5): v69-v77.

- Schellhammer, P.F.; Chodak, G.; Whitmore, J.B.; Sims, R.; Frohlich, M.W.; Kantoff, P.W. Lower Baseline Prostate-specific Antigen Is Associated With a Greater Overall Survival Benefit From Sipuleucel-T in the Immunotherapy for Prostate Adenocarcinoma Treatment (IMPACT) Trial. Urology 2013, 81, 1297–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R.B. Development of sipuleucel-T: Autologous cellular immunotherapy for the treatment of metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer. Vaccine 2011, 30, 4394–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart FP, Dela Rosa C, Sheikh NA, McNeel DG, Frohlich MW, Urdal DL et al. Correlation between product parameters and overall survival in three trials of sipuleuce-T, an autologous active cancer chemotherapy for the treatment of prostate cancert. J Clin Oncol 2010: 28: (15s) abstract 4552.

- Fong, L.; Carroll, P.; Weinberg, V.; Chan, S.; Lewis, J.; Corman, J.; Amling, C.L.; Stephenson, R.A.; Simko, J.; Sheikh, N.A.; et al. Activated Lymphocyte Recruitment Into the Tumor Microenvironment Following Preoperative Sipuleucel-T for Localized Prostate Cancer. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galon, J.; Bruni, D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, S.; Subudhi, S.K.; Aparicio, A.; Ge, Z.; Guan, B.; Miura, Y.; Sharma, P. Differences in Tumor Microenvironment Dictate T Helper Lineage Polarization and Response to Immune Checkpoint Therapy. Cell 2019, 179, 1177–1190.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosser C,J, Hirasawa Y, Acaba JD, Tamura DJ, Pal SK, Huang J, Scholz MC, Dorffet TB. Phase 1b study assessing different sequencing regimens of atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1)and spipuleucin T (Sip-T) ikn patients who have asympotomatic or minimally symptomatic metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38: e17564.

- Marshall, C.H.; Fu, W.; Wang, H.; Park, J.C.; DeWeese, T.L.; Tran, P.T.; Song, D.Y.; King, S.; Afful, M.; Hurrelbrink, J.; et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Sipuleucel-T with or without Radium-223 in Men with Bone-metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, T.L.; Weiner, G.J. Uses of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in vaccine development. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2000, 7, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joniau, S.; Abrahamsson, P.-A.; Bellmunt, J.; Figdor, C.; Hamdy, F.; Verhagen, P.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Wirth, M.; Van Poppel, H.; Osanto, S. Current Vaccination Strategies for Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2012, 61, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, S.; Hans, B.; Goel, S.; Bashorun, H.O.; Dovey, Z.; Tewari, A. Immunotherapy in prostate cancer: Current state and future perspectives. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulley, J.L.; Borre, M.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Ng, S.; Agarwal, N.; Parker, C.C.; Pook, D.W.; Rathenborg, P.; Flaig, T.W.; Carles, J.; et al. Phase III Trial of PROSTVAC in Asymptomatic or Minimally Symptomatic Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlen, P.M.; Gulley, J.L.; Parker, C.; Skarupa, L.; Pazdur, M.; Panicali, D.; Beetham, P.; Tsang, K.Y.; Grosenbach, D.W.; Feldman, J.; et al. A randomized phase II study of concurrent docetaxel plus vaccine versus vaccine alone in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granier C, Badoual C, De Guillebon E, Blanc C,, Roussel H,S, Colin E, Saldmann A, Gey A, Oudard S, Tartour E,. Mechanisms of action and use of checkpoint inhibitors in cancer. ESMO open 2017; 2: e000213.

- Huang J, Wang L, Cong Z, Amoozgar Z, Kiner E, Xing D, Orsulic S, Matulonis U,Goldberg MS. The PARP1 inhibitor BMN 673 exhibits immunoregulatory effects in BRCA-1 -/- murine model of ovarian cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015; 463: 551-556.

- Farhangnia, P.; Ghomi, S.M.; Akbarpour, M.; Delbandi, A.-A. Bispecific antibodies targeting CTLA-4: Game-changer troopers in cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1155778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacsson V, Antonarkis ES. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway inhibitors in advanced prostate cancer. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2018; 11: 475-486.

- Xu Y, Song G,Xie S, Jiang W, Chen X, Chu M, Hu X,Wang ZW. The roles of PD-1/PD-L1 in the prognosis and immunotherapy of prostate cancer. Mol Ther 2021; 29: 1958-1969.

- Leng, C.; Li, Y.; Qin, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, X.; Cui, Y.; Sun, H.; Wang, Z.; Hua, X.; Yu, Y.; et al. Relationship between expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and the antitumor effects of CD8+ T cells. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 35, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmaninejad A, Valilou SF, Shabgah AG, Aslani S, Alimandani M, Pasdar A, Sahebkar, A. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: Basic biology and role in cancer immunotherapy. J Cell Phsiol 2019; 234: 16824-16837.

- Lotfinejad, P.; Kazemi, T.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Shanehbandi, D.; Niaragh, F.J.; Safaei, S.; Asadi, M.; Baradaran, B. PD-1/PD-L1 axis importance and tumor microenvironment immune cells. Life Sci. 2020, 259, 118297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Dai, Z.; Wu, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, W.-J.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, Q. Regulatory mechanisms of immune checkpoints PD-L1 and CTLA-4 in cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon ED, Drake CG, Scher HI, Fizazi K, Bossi A, Van der Eeertwegh AJ, Krainer M, Houede N, Santos R, Mahammedi, H. Ipilimumab versus placebo after radiotherapy in patitents with metastastic castration-resistant prostate cancer that had progressed after docetaxol chemotherapy (CA184-03): A multicentre randomized double blind phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 700-712.

- Beer, T.M.; Logothetis, C.; Sharma, P.; Bossi, A.; McHenry, B.; Fairchild, J.P.; Gagnier, P.; Chin, K.M.; Cuillerot, J.-M.; Fizazi, K.; et al. CA184-095: A randomized, double-blind, phase III trial to compare the efficacy of ipilimumab versus placebo in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients (pts) with metastatic chemotherapy-naive castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, TPS4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K.; Drake, C.G.; Beer, T.M.; Kwon, E.D.; Scher, H.I.; Gerritsen, W.R.; Bossi, A.; Eertwegh, A.J.v.D.; Krainer, M.; Houede, N.; et al. Final Analysis of the Ipilimumab Versus Placebo Following Radiotherapy Phase III Trial in Postdocetaxel Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Identifies an Excess of Long-term Survivors. Eur. Urol. 2020, 78, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, W.; Dong, B.; Xin, Z.; Ji, Y.; Su, R.; Shen, K.; Pan, J.; Wang, Q.; Xue, W. Docetaxel remodels prostate cancer immune microenvironment and enhances checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Theranostics 2022, 12, 4965–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, M.; Zhang, L.; Subudhi, S.; Chen, B.; Marquez, J.; Liu, E.V.; Allaire, K.; Cheung, A.; Ng, S.; Nguyen, C.; et al. Pre-existing immune status associated with response to combination of sipuleucel-T and ipilimumab in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalin SL. Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman SA, Atkins MB el at. Safety, activity and immune correlates of Anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Eng J Med 2012; 366: 2443-2454.

- Fakhrejehani F, Madan RA, Dahut WL, Karzai F, Cordes LM, Schlom J, Liow E, Bennett C, ZhengT, Yu J et al. Avelumab in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 159.

- Hoimes CJ, Graff JN, Tagawa ST, Hwang C, Kilari D, Ten Tije AJ, Omlin AU, McDermott RS, Vaishampayan UN, Elliot T et al. KEYNOTE-199 cohort (C) Phase II study of pembrolizumam (pembro) plus enzalutamide (enzo) for enzo resistante metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. J Cin Oncol 2020; 38: 5543.

- Antonarakis E, Piulats J, Gross-Goupil M, Goh J, Vaishampayan U, De Wit R, Alanko T, FukasawanS, Tabata T, Feyerabend S Pembrolizumab monotherapy for treatment-refractory for docetaxol-pretreated metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. Updated analyses with 4 years of follow-up from cohorts 1-3 of the KEYNOTE-199 study. Ann Oncol 2021; 32: S651-S652.

- Graff JN, Liang LW, Kim, J., Stenzel, A. Keynote-641: A phase 3 study of pembrolizumumab plus enzalutamide for metastatic asgration resisitant prostate cancer: Futr Oncol 2021; 17: 3107-3026.

- Powles T, Yuen KC, Gillessen S, Kadel EE 3rd; Rathkopf D, Matsubara N, Drake CG, Fizazi K, Piulats JM, Wysocki PJ et al. Atezolizumaba with enzautamide versus enzautamide alone in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. A randomized phase 3 trial. Nat Med 2022; 28: 144-153.

- Blanco B, Dominguez-Alonso C, Alvarez -Vallina, L. Bispecific immunomodulatory antibodies for cancer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2021; 27: 5457-5464).

- Heuls AM, Coupet TA, Sentman CL: Bispecific T-cell engagers for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Cell Biol 2015; 93: 290-296).

- Zhou, S.-J.; Wei, J.; Su, S.; Chen, F.-J.; Qiu, Y.-D.; Liu, B.-R. Strategies for Bispecific Single Chain Antibody in Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Cancer 2017, 8, 3689–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar M, Pravin J, Rodriques L, Uhlenbroich S, Everett KL, Wollerton F, Morrow M, Tuna M, Brevis, N. CD137/OX40 bispecfic antibody induces potent antitumor activity that is dependent on target coengagement. Cancer Immunol Res 2020; 8: 781-793.

- Lee SC, MA JS, Kim SC, Laborda E, Choi SH, Hampton EN, Yun H, NunezV, Muldong MT, Wu CN. A PMSA targeted bispecific antidody for prostate cancer driven by a small-moecular targeting ligand, Sci Adv 2021; 7: eab8193.

- Chiu D, Tavara R, Haber L, Aina OH, Vazzana K, Ram P, Danton M, Finney J, Jalal S, Krueger P A PMSA targeting CD3 bisoecific antibody induces antitumor responses that are enhanced by 4-1BB costimulation. Cancer Immunol Res 2020; 8: 595-608.

- Deegan P, Thomas O, Noal-Stevaux, O., Li, S. Wahl J, Bogner P, Aeffner F, Friedrich, M., Liao MZ, Mattes, K. The PSMA targeting half-life extended BiTE therapy AMG 160 has potent antitumoral activity in pre-clincal models of metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2021; 27: 2928-2937.

- Miyahira, A.K.; Soule, H.R. The 27th Annual Prostate Cancer Foundation Scientific Retreat Report. Prostate 2021, 81, 1107–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Soper, B.; Shopland, L. Cytokine release syndrome and cancer immunotherapies—Historical challenges and promising futures. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1190379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T., Zhu, L., Chen, J. Current advances and challenges in CAR-T therapy for solid tumors. Tumor associated antigens and the tumor microenvironment, Exp Hematol Oncol 2023; 12: 14.

- George P, Dasyam N, Giunti G, Mester B, Bauer E, Andrews B, Perera T, Ostapowicz T, Frampton, C., Li, P.,. Third generation anti CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cells incorporating a TRL2 domain for relapsed or refactory B-cel lymphoma: A phase I clinical trial protocol (ENABLE) BMJ Open 2020; 10: e034629.

- Roselli E, Boucher JC, Li G, Kotani H, Spitler K, Reid K, Cervantes EV, Bulliard Y, Tu N, Lee SB. 4-1BB and otimized CD28 costimulation enhances function of human mono-spefic and bi-specific thrd-generation CAR T cells. J Immunother Cancer 2021; 9: e003354.

- Ramos, C.A.; Rouce, R.; Robertson, C.S.; Reyna, A.; Narala, N.; Vyas, G.; Mehta, B.; Zhang, H.; Dakhova, O.; Carrum, G.; et al. In Vivo Fate and Activity of Second- versus Third-Generation CD19-Specific CAR-T Cells in B Cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 2727–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloss, C.C.; Lee, J.; Zhang, A.; Chen, F.; Melenhorst, J.J.; Lacey, S.F.; Maus, M.V.; Fraietta, J.A.; Zhao, Y.; June, C.H. Dominant-Negative TGF-β Receptor Enhances PSMA-Targeted Human CAR T Cell Proliferation And Augments Prostate Cancer Eradication. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 1855–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frieling JS, Tordesilla L, Bustos XE, Ramello MC, Bishop RT, Cianne JE, Snedal SA, Li T, Lo CH, de la Iglesia, J. gamma-delta enriched CAR-T therapy for bone metastastic castrate resistant prostate cancer. Sci Adv 2023; ): eadf0108.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, Q.; Wang, F.; Zhang, C.; Xu, C.; Gu, A.; Zhong, W.H.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, X. Co-expression IL-15 receptor alpha with IL-15 reduces toxicity via limiting IL-15 systemic exposure during CAR-T immunotherapy. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorff TB, Blanchard S, Martirosyan H, Adkins L, Dhapola G, Moriarty A, Wagner JR, Chaudhry A, D} Apuzzo M, Kuhn, P. Phase 1 study of PSCA-targetted CAR T cell therapy for metastatic Castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) J Clin Oncol 2022; 40: 91.

- Pennisi, M.; Jain, T.; Santomasso, B.D.; Mead, E.; Wudhikarn, K.; Silverberg, M.L.; Batlevi, Y.; Shouval, R.; Devlin, S.M.; Batlevi, C.; et al. Comparing CAR T-cell toxicity grading systems: Application of the ASTCT grading system and implications for management. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milowsky, M.I.; Nanus, D.M.; Kostakoglu, L.; Vallabhajosula, S.; Goldsmith, S.J.; Bander, N.H. Phase I Trial of Yttrium-90—Labeled Anti—Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Monoclonal Antibody J591 for Androgen-Independent Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 2522–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman MS, Violet J, Hicks RJ, Ferdinandus J, Thang SP, Akhust T, Iravani A, Kong G, Ravi Kumar A, Murphy DG et al. [177Lu]-PSMA-617 radionuclide treatment in patients metastatic resistant prosateancer (luPSMA trial); a single centre, single arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19: 825-833.

- Niaz MJ, Batra JS, Walsh RD, Ramirez-Font MK, Vallabhaajosulo S, Jhanwar YS, Molina AM, Nanus DM, Osborne JR, Bando NH et al., Pilot study of hyperfractionated dosing of lutetium-177-labelled anti.prostate specific membrane antigen momoclonal antibody J591 (1777Lu-J5911 for metastatic castration reistnat prostate cancer. Oncologist 2020; 25; 477-e895.

- Vlachostergios PJ, Niaz MJ, Skafida M, Mossallaie SA, Thomas C, Christos PJ, Osborne JR, Molina AM, Nanus DM, Bander NH, Tagawa ST. Imaging expression of prostate specific membrane antigen and response to PMSA targeted beta-emitting radionuclie therapies in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. Prostate 2021; 81: 279-285.

- Hofman MS, Emmett L, Vilet J, Iravani A, Joshua AM, Goh JC, Pattison DA, Tan TH, Kirkwood ID, Ng s et al. TheraP: A randomized phase 2 trial of 177 Lu-PMSA-617 theranostics vs cabazitaxel in progressive castration resistnante prostate cancer, (Clinical trial protocol ANZUP 1603) BJU Int 2019; 124 Suppl1: 5-13.

- US Food and Drug ASministration(FDA). FDA approves Pluvicto for metastatic castratin resistant prostate cancer. News release march 23, 2022, accessed december 2024 https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information.approved-drugs/fda-approves-pluvicto-metastatic-castration-resistant-prostate-cancer.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Pluvicto: EPAR-medicine overview. European public assessment report December 21 Accessed December 2024.

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/overview/pluvict0-par-medicine-overview_en.pdf.

- Arbuznikova, D.; Eder, M.; Grosu, A.-L.; Meyer, P.T.; Gratzke, C.; Zamboglou, C.; Eder, A.-C. Towards Improving the Efficacy of PSMA-Targeting Radionuclide Therapy for Late-Stage Prostate Cancer—Combination Strategies. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 25, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studies on prostatic cancer I. The effect of castration, of estrogen and of androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. 1941. 2002; 168: 9-12.

- Desai, K.; McManus, J.M.; Sharifi, N. Hormonal therapyfor prostate cancer. Endocr. Reiews 42, 354–373.

- Pantel, K.; Alix-Panabières, C. Bone marrow as a reservoir for disseminated tumor cells: A special source for liquid biopsy in cancer patients. BoneKEy Rep. 2014, 3, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun GY, Jing H, Wang SL, Song YW, Jun, J., Fang H et al. Trastuzumab provides a comparable prognosis in patients with HER-2 positve breast cancer to those with HER-2 negative breast cancer: Post hoc analyses of a randomised controlled trial of post mastectomy hypofractionated radiotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10, 605750.

- Wu XQ, Ge, YP, Gong XL, Liu, Y., Bai CM. Advances in the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor2 positive gastric cancer. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao2022; 44: 899-905.

- Murray, N.P.; Aedo, S.; Fuentealba, C.; Reyes, E.; Salazar, A.; Lopez, M.A.; Minzer, S.; Orrego, S.; Guzman, E. Subtypes of minimal residual disease, association with Gleason score, risk and time to biochemical failure in pT2 prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy. ecancermedicalscience 2019, 13, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubenik, J.; Simová, J. Minimal residual disease as the target for immunotherapy and gene therapy of cancer (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2005, 14, 1377–1380. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).