Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Balancing tourism seasonality remains a significant challenge in the management of tourist attractions. Despite existing research on the impact of seasonality from the perspectives of tourist intention cognition and spatial theory, gaps still exist in the relevant literature. This study examines 16 5A-level scenic spots in China with peak-season, flat-season, and off-season, utilizing 8,385 tourist reviews from Ctrip.com as data. The LDA topic model is employed to analyze Tourism destination image (TDI) under seasonality of destination, and the spatial levels (SL) model is combined to analyze the spatial hierarchy of these images. The findings reveal an association between TDI and the SL under seasonality of destination. For instance, peak-season TDI themes (e.g., 'viewing the scenery') exhibit a support level of 0.789, while off-season themes (e.g., 'relaxed itinerary') reach 0.682, reflecting tourists’ prioritization of functional versus psychological dimensions across seasons. The proposed TDI-SL correlation theory bridges supply-side spatial resource allocation with tourists’ perceptual dynamics, offering a novel framework to rebalance seasonal demand-supply gaps through strategic spatial planning and image recalibration. Practically, this framework guides destination managers to design season-specific strategies, such as optimizing crowd management in peak seasons or promoting immersive experiences in off-seasons.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data Sources and Research Methods

3.1. Selection of the Study Population

3.2. Data Sources and Processing

3.3. Research Methodology

4. Research Findings

4.1. TDI in Tourist Attractions

4.2. TDI in "Cognitive-Affective" Space

4.3. The Association Between TDI and SL

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Seasonality has a significant impact on tourists’ behavioral intentions. Through the analysis of 16 5A-level scenic spots with typical seasonal characteristics, this study clarifies that seasonality has a significant impact on tourists’ behavioral intentions. During the peak season, the support levels of themes such as "viewing the scenery" and "landscape comparison" are the highest, indicating that the main purpose of tourists in the peak season is to appreciate the natural scenery, while also paying attention to the uniqueness and visual impact of the landscape. In the flat season, "price discounts" and "travel routes" become the most concerned factors for tourists, who tend to choose relatively cheaper travel products and pay attention to the rationality and convenience of travel routes to improve travel efficiency. In the off-season, the support levels of "relaxed itinerary" and "spatial experience" are the highest, with tourists focusing more on the comfort of travel, hoping to avoid crowds and enjoy a relaxed and leisurely travel time, and experiencing the spacious spatial layout of the scenic spots.

- (2)

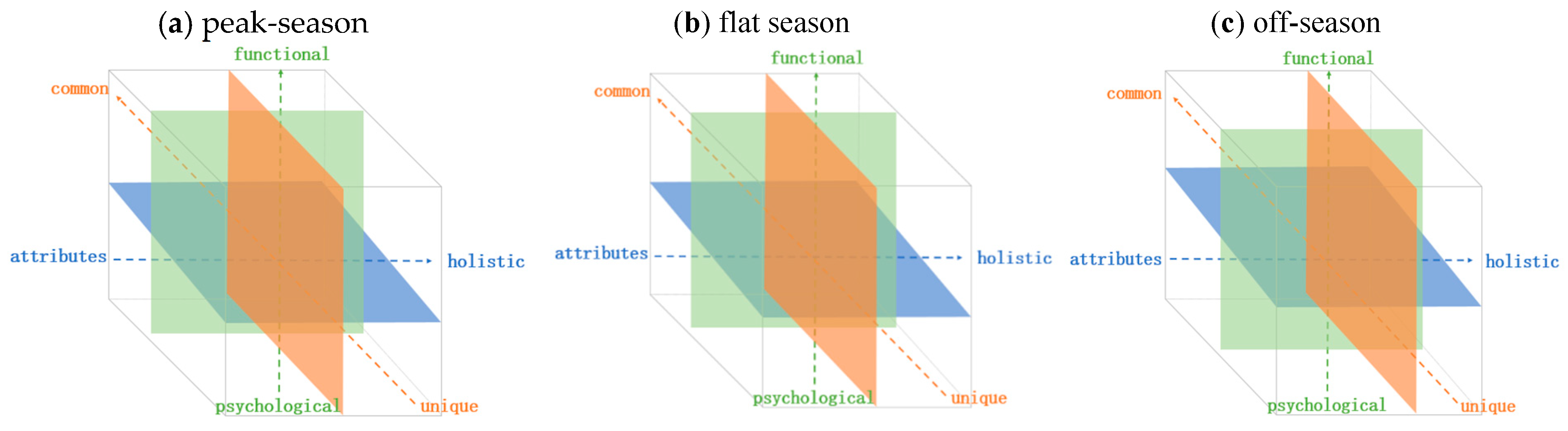

- The correlation between TDI and "cognitive-affective" space. Under the "cognitive-affective" image framework, tourists’ behavioral intentions have three major characteristics. First, the intention themes are relatively concentrated in the functional and unique dimensions. In the peak season, attention is paid to landscape colors, historical legends, etc.; in the flat season, attention is paid to travel experience, characteristic houses, etc.; in the off-season, attention is paid to natural landscapes, cultural relics, etc., indicating that the formation of tourists’ travel images pays more attention to tangible and characteristic elements. Second, there is little difference in the theme distribution between the feature-whole dimensions. In the process of forming TDI, tourists not only pay attention to the current characteristic elements involved but also control the overall situation of the scenic spot, thereby building the overall image of the scenic spot. There is an inverse effect between the image themes in the functional and psychological dimensions. The distribution of themes in the functional dimension shows peak season > flat season > off-season, while the distribution of themes in the psychological dimension shows peak season < flat season < off-season. This is due to the tight resources and crowding during the peak season, which focuses tourists’ attention on tangible elements.

- (3)

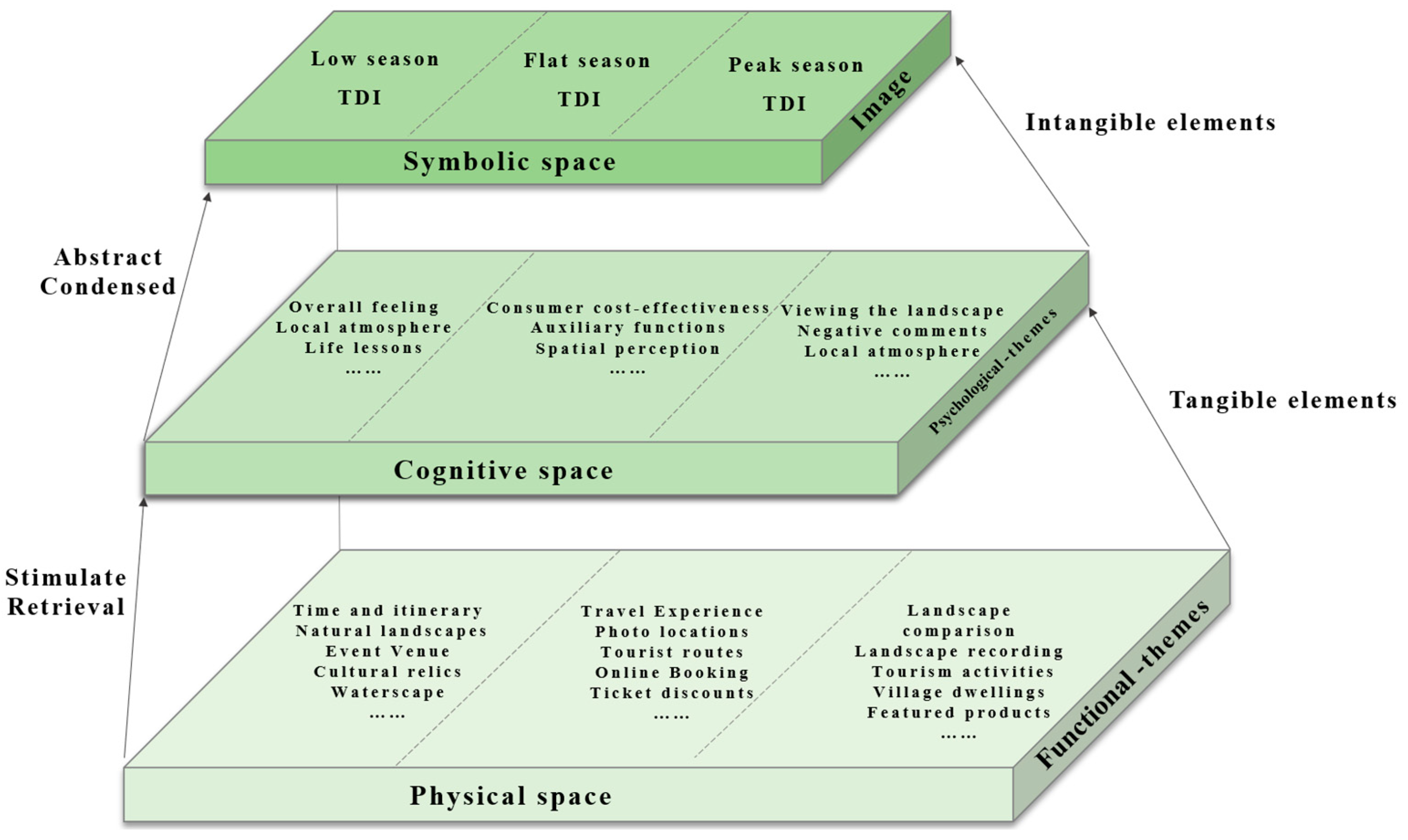

- The correlation between TDI and SL. The spatial system of scenic spot images can be divided into physical space, cognitive space, and symbolic space, among which the "functional-psychological" dimension in the three-dimensional continuum corresponds to the image themes in the physical and cognitive spaces in the spatial hierarchy. By stimulating and abstracting the elements in the tangible physical-functional level and the intangible cognitive-spatial level, TDI in the symbolic space can be constituted, thereby achieving the three-dimensional expression of the scenic spot image. From the perspective of SL, tourists’ behavioral intentions have different performances in physical and cognitive spaces. In physical space, the proportion of TDI is the highest in the peak season and the lowest in the off-season. In the cognitive space, the proportion of TDI is the highest in the off-season and the lowest in the peak season.

5.2. Insights

- (1)

- The elements of management and promotion for peak, flat, and off-season travelers can be subdivided and strengthened. During the peak season, due to the pressure of destination reception, emphasis can be placed on strengthening the thematic content of the following three aspects: tourism landscape, local characteristics, and special performance. During the off-season, as the main theme of tourists’ perception is consumption value for money, the promotion and management content of the tourism landscape, spatiotemporal activities, local characteristics, and tourism services can be added based on focusing on promoting tourism booking and preferential consumption. The off-season is a period of restoration, and it is still vital to pay attention to how the tourism landscape shapes the perception of tourist destinations and to consider management strategies that will support thematic content, including spatiotemporal activities.

- (2)

- Tourism attractions can focus on tangible and unique thematic elements for promotion and marketing. In the peak season, tourists are more concerned about landscape colors and scenic records when they visit; these can take the form of photo-taking and internet attractions as elements by which to further expand the tail wave effect based on other additional attractions. In the flat season, tourists are more concerned about travel experiences and travel routes, etc.; thus, tourist attractions can promote special routes and travel activities in the form of booking. off-season travelers are more concerned with thematic images, such as natural landscapes and humanistic monuments, and tourist attractions can give full play to their off-season advantages by reinforcing local ambience such as relaxation, self-healing, and cultural inculcation based on the natural environment and local ordinary life, with the goal being to satisfy visitors’ demands for attention.

- (3)

- Destination managers could implement dynamic pricing tiers (e.g., higher peak-season fees to curb overcrowding) and develop off-season wellness programs (e.g., meditation retreats in Nalati Scenic Area) to balance demand. Peak Season: Improve visitor flow and enhance service quality through digital queue management and crowd monitoring.For example, adopt Japan’s digital queue systems (e.g., Kyoto’s temple reservation app) to manage crowds.Flat Season: Bundle tickets with local experiences, akin to Hainan’s summer ’cultural immersion’ packages.Off-Season: Promote alternative tourism products (e.g., wellness retreats, educational tourism, or digital nomad-friendly facilities.Promote ’digital nomad’ initiatives, as seen in Bali’s co-working retreats during low seasons.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vergori A S .Patterns of seasonality and tourism demand forecasting. Tourism Economics, 2017, 23(1):135481661665641.

- Steiger R , Posch E , Tappeiner G ,et al. Seasonality matters: simulating the impacts of climate change on winter tourism demand. Current Issues in Tourism, 2022, 26:2777 - 2793.

- Choe Y , Kim H , Joun H J . Differences in Tourist Behaviors across the Seasons: The Case of Northern Indiana[J]. Sustainability, 2019, 11.

- Boto-Garcia, D.; Perez, L. The effect of high-speed rail connectivity and accessibility on tourism seasonality. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 107, 103546. [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Joy, A. Tourism destination image (TDI) perception of a Canadian regional winescape: A free-text macro approach. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2017, 42, 367–379. [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.; Saura, I. Destination Image: Towards a Conceptual Framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 56–78.

- Descroix L , Mathys N .Processes, spatio-temporal factors and measurements of current erosion in the French Southern Alps: A review.Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 2003, 28(9):993-1011.

- Portz, L.C.; Pérez Torres, Y.S.; Manzolli, R.P. Coast Change: Understanding Sensitivity to Beach Loss for Coastal Tourism in the Colombian Caribbean. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13903. [CrossRef]

- Ahas, R.; Aasa, A.; Mark, U.; Pae, T.; Kull, A. Seasonal tourism spaces in Estonia: Case study with mobile positioning data. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 898–910. [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 97–116. [CrossRef]

- Goulding, Philip, J, et al. Seasonal Trading and Lifestyle Motivation: Experiences of Small Tourism Businesses in Scotland.[J]. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 2004.

- Martin, J.M.M., Fernandez, J.A.S., & Martin, J.A.R. Comprehensive evaluation of the tourism seasonality using a synthetic DP2 indicator. Tourism Geographics, 2019,21, 284–305. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Liu, Y., Li, G., & Wen, L. Tourism demand nowcasting using a LASSO-MIDAS model. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management,2021,33, 1922–1949.

- Duro, J.A.; Turrion-Prats, J. Tourism seasonality worldwide. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 38–53. [CrossRef]

- Sastre, M.A.G.; Hormaeche, M.A.; Villar, M.T. Are regional political decisions the key element in reducing seasonal variation in tourism? The case of the Balearic Islands. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 1207–1219. [CrossRef]

- Turrion-Prats, J.; Duro, J.A. Tourist seasonality in Catalonia: The relevance of demand factors. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 846–853.

- Vergori, A.S. Forecasting tourism demand: The role of seasonality. Tour. Econ. 2012, 18, 915–930. [CrossRef]

- Coshall, J.; Charlesworth, R.; Page, S.J. Seasonality of Overseas Tourism Demand in Scotland: A Regional Analysis. Reg. Stud. 2015, 49, 1603–1620. [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Qu, H.L. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [CrossRef]

- Cuccia, T.; Rizzo, I. Tourism seasonality in cultural destinations: Empirical evidence from Sicily. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 589–595. [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of Tourists’ Loyalty to Mauritius: The Role and Influence of Destination Image, Place Attachment, Personal Involvement and Satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356.

- Koenig-Lewis, N.; Bischoff, E.E. Developing Effective Strategies for Tackling Seasonality in the Tourism Industry. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2010, 7, 395–413. [CrossRef]

- Egger, R.; Yu, J. Identifying hidden semantic structures in Instagram data: A topic modelling comparison. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 1234–1246. [CrossRef]

- Merkert, R.; Webber, T. How to manage seasonality in service industries—The case of price and seat factor management in airlines. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 72, 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.D. Image As a Factor in Tourism Development. Tour. Recreat. Res. 1982, 7, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Gatti, E.T.J.; Brownlee, M.T.J.; Bricker, K.S. Winter recreationists’ perspectives on seasonal differences in the outdoor recreation setting. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour.-Res. Plan. Manag. 2022, 37, 100366. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Lu, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Liang, D.; Dong; Yang, Z. Temporal Characteristics of Tourist Flows to Ancient Villages—A Case Study of Two World Cultural Heritages Xidi Village and Hongcun Village. Geogr. Sci. 2004, 24, 250–256.

- Huang, S.; Hsu, C.H.C. Effects of Travel Motivation, Past Experience, Perceived Constraint and Attitude on Revisit Intention. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 29–44.

- Baloglu, S.; Mccleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Hsu, C.H.C. Effects of Travel Motivation, Past Experience, Perceived Constraint and Attitude on Revisit Intention. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 29–44.

- Li, Y.; Z. Y. He, Li, Y.P.; Huang, T.; Liu, Z.Y. Keep it real: Assessing destination image congruence and its impact on tourist experience evaluations. Tour. Manag. 2023, 97, 104736. [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.A.; Sparks, B. Predicting Wine Tourism Intention: Destination Image and Self-congruity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 443–460. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Lu, W.; Liang, C.; Wang, B. Intelligence in Tourism Management: A Hybrid FOA-BP Method on Daily Tourism Demand Forecasting with Web Search Data. Mathematics 2019, 7, 531. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Hsu, C.H.C. Effects of Travel Motivation, Past Experience, Perceived Constraint and Attitude on Revisit Intention. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 29–44.

- Saito, H.; Romao, J. Seasonality and regional productivity in the Spanish accommodation sector. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 180–188. [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.Y.; Luo, J.M. Topic modelling for wildlife tourism online reviews: Analysis of quality factors. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. R., & Scott, N. Network dynamics of tourism development in South Korea. Current Issues in Tourism, 2018,21(8), 1239-1259.

- Gale, C.N. Space and Spaces. Geogr. Ann. 1986, 68, 1–12.

- Guerra-Medina, D.; Rodríguez, G. Spatiotemporal Variability of Extreme Wave Storms in a Beach Tourism Destination Area. Geosciences 2021, 11, 237. [CrossRef]

- Echtner, C.M. The meaning and measurement of destination image. journal of tourism studies. J. Tour. Stud. 2003, 14, 37–48.

- Connell, J.; Page, S.J.; Meyer, D. Visitor attractions and events: Responding to seasonality. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 283–298. [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.S.; Hassani, H.; Heravi, S.; Huang, X. Forecasting tourism demand with denoised neural networks. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 134–154. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhu, H. On the Representation and Non-representation Dimensions of the Production of Social and Cultural Geographical Knowledge. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2020, 40, 1039–1049.

- Szubert, M.; Warcholik, W.; Zemla, M. Destination Familiarity and Perceived Attractiveness of Four Polish Tourism Cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 128. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Park, S. A cross-cultural anatomy of destination image: An application of mixed-methods of UGC and survey. Tour. Manag. 2023, 98, 104746. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Wen, L. Tourism demand nowcasting using a LASSO-MIDAS model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1922–1949. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.J.; Long, Y. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Residents Tourism Demand for Typical Scenic Spots in Hunan Province Based on Network Attention. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 37, 201–208.

- Martin, J.M.M.; Fernandez, J.A.S.; Martin, J.A.R. Comprehensive evaluation of the tourism seasonality using a synthetic DP2 indicator. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 21, 284–305. [CrossRef]

- Connell, J., Page, S.J., & Meyer, D. Visitor attractions and events: Responding to seasonality. Tourism Management, 2015,46, 283–298. [CrossRef]

- Shang Z , Luo J .Topic modelling for wildlife tourism online reviews: analysis of quality factors.Current Issues in Tourism, 2023, 26:2317 - 2331.

- Lee, J.S., & Park, S. A cross-cultural anatomy of destination image: An application of mixed-methods of UGC and survey. Tourism Management, 2023,98, 104746. [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Xiong, Y. Contrastive Analysis at Home and Abroad on the Evolution of Hot Topics in the Field of Data Mining Based on LDA Model. Inf. Sci. 2021, 39, 174–185.

- Mattos J B , Moreira Cruz M J , Carlos F D P F ,et al.Natural and anthropic processes controlling groundwater hydrogeochemistry in a tourist destination in northeastern Brazil.Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2018, 190(7):395.

- Bezugly, V., KostaschukІ., Kisil, R., Yavorska, V., & Buyanovska, L. World Heritage: features, composition, and tourist significance. Journal of Geology, Geography and Geoecology, 2024,33, 440-452.

- Taecharungroj, V.; Mathayomchan, B. Analysing TripAdvisor reviews of tourist attractions in Phuket, Thailand. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 550–568. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.P.; Wu, B.H.; Wang, Y. Tourism destination image based on tourism user generated content on internet. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 125–137. [CrossRef]

- Tan, C., & Xiong, Y. Contrastive Analysis at Home and Abroad on the Evolution of Hot Topics in the Field of Data Mining Based on LDA Model. Information Science,2021, 39, 174–185.

- Zhang, K., Chen, Y., & Lin, Z.B. Mapping destination images and behavioral patterns from user-generated photos: A computer vision approach. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 2020,25, 1199–1214. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.B. Mapping destination images and behavioral patterns from user-generated photos: A computer vision approach. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 1199–1214.

- Zhang, X.H.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.A.; Xu, Z.Y.; Huang, Z.F. Hierarchical Fusion Process of Destination Image Formation: Targeting on Urban Tourism Destination. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11805. [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Medina, D., & Rodríguez, G. Spatiotemporal Variability of Extreme Wave Storms in a Beach Tourism Destination Area. Geosciences, 2021,11, 237. [CrossRef]

- Suwandana.Escherichia Coli and Biophysicochemical Relationships of Seawater and Water Pollution Index in the Jakarta Bay.American Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2011, 7(3):183-194.

- Szubert, M., Warcholik, W., & Zemla, M. Destination Familiarity and Perceived Attractiveness of Four Polish Tourism Cities. Sustainability, 2022,14, 128. [CrossRef]

- Duro, J.A., & Turrion-Prats, J. Tourism seasonality worldwide. Tourism Management Perspectives, 2019,31, 38–53.

| Scenic Areas | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Scenic Areas | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chengde Summer Palace Scenic Area | 6.39 | 5.74 | 6.8 | Yannanfei Tea Field Scenic Area | 3.66 | 4.35 | 4.36 |

| Jinshi Beach Scenic Area | 5.19 | 6.05 | 4.88 | Nanshan Daxiaodongtian Tourism Area | 4.79 | 5.14 | 9.01 |

| Jiangwan Scenic Area, Wuyuan | 4.07 | 12.27 | 5.5 | Jiuzhaigou Tourist Attractions | 8.17 | 7.15 | 8.18 |

| Dajue Mountain Scenic Area | 4.14 | 5.11 | 3.9 | Golden Silk Gorge Scenic Area | 3.95 | 6.11 | 6.54 |

| Liu Gong Island Scenic Area | 4.08 | 4.56 | 10.89 | Qinghai Lake Scenic Area | 6.64 | 6.26 | 5.22 |

| Yellow River Mouth Ecotourism Area | 4.41 | 6.01 | 13.77 | Kanas Scenic Area | 4.23 | 5.21 | 8.64 |

| Longtan Grand Canyon Scenic Area | 3.97 | 4.12 | 4.05 | Nalati Scenic Area | 4.46 | 4.98 | 4.22 |

| Enshi Grand Canyon Scenic Area | 3.62 | 5.38 | 6.5 | Bayinbruck Scenic Area | 4.92 | 3.67 | 10.76 |

| Peak season | flat season | off-season Season | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Words | Degree of Support | Example of a Feature Word | Key Words | Degree of Support | Example of a Feature Word | Key Words | Degree of Support | Example of a Feature Word |

| Viewing the landscape | 0.789 | Line crowded |

Price discount | 0.373 | Ticket | journey easy | 0.682 | Few people |

| Photo, | Convenient | Relaxed | ||||||

| Landscape comparison | 0.056 | Check-in | Tourist route | 0.347 | Spatial perception | 0.104 | ||

| Preferential | Downhill | |||||||

| Featured products | 0.039 | Snowdrop | Tourist routes | 0.124 | Doorway | Spatial perception | 0.067 | Located |

| Yurt | Direct access | Northeast | ||||||

| Landscape colors | 0.035 | Blue | Travel methods | 0.028 | Self-drive | Waterscape | 0.055 | Kanas Lake |

| Cyan | Walks | Waterfalls | ||||||

| Historical legends | 0.016 | The water monster | Travel experience | 0.023 | Rafting | Natural landscapes | 0.026 | Grassland |

| Qianlong | Fun | Snowy mountains | ||||||

| Tourism activities | 0.015 | Crabbing | Wonders and scenes | 0.019 | Wonders stonescape | Event venue | 0.017 | Ranch |

| by boat | Riding | |||||||

| Cautions | 0.008 | ID card | Seasonal perception | 0.017 | Winter | Local atmosphere | 0.01 | Cozy |

| Sun protection | Cold | Unpretentious | ||||||

| Featured pavilion | 0.008 | Wax museum | Characteristic building | 0.012 | Build | Evaluation recommendations | 0.007 | Fun |

| Art gallery | Anhui style | Pick up tickets | ||||||

| Local atmosphere | 0.007 | Aesthetic | Photo locations | 0.011 | Photography | Cultural relics | 0.006 | Ancient villages |

| Atmosphere | Tianshan Mountains | Cultural heritage | ||||||

| Village dwellings | 0.006 | Log cabin | Security guarantee | 0.011 | Askari | Weather and climate | 0.005 | Sunny |

| Yurt | protection | Winter day | ||||||

| Landscape recording | 0.005 | Photo | Auxiliary functions | 0.008 | For the benefit of the nation and the people | Physical and mental state | 0.005 | Pleasant |

| Sunset | Science | High altitude reaction | ||||||

| Transport issues | 0.005 | Sicken | Spatial perception | 0.008 | Northwest | Environmental perception | 0.005 | Mist |

| Contested roads | World | Savor carefully | ||||||

| Specialty diet | 0.004 | Lamb | Specialty diet | 0.008 | Sample tea | Entertainment | 0.004 | Bonfire |

| Barley | Beef and lamb | Rollercoaster | ||||||

| Negative comments | 0.003 | Unbearable disproportionate | Online booking | 0.008 | Ctrip | Overall feeling | 0.002 | The sky is high and the sea is wide |

| Booking | The whole piece | |||||||

| Physical and mental state | 0.003 | High-altitude reaction | Landscape colors | 0.005 | Blue water | Life lessons | 0.002 | No worries |

| Fatigue | Golden color | Perception | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).