1. Introduction

The energy performance of buildings is critical in addressing global energy consumption and mitigating climate change impacts. Buildings, encompassing a variety of typologies such as residential, commercial, and institutional structures, account for a substantial portion of energy use worldwide, with estimates suggesting they contribute nearly 40% of total energy consumption and approximately one-third of greenhouse gas emissions (San José et al., 2020). As climate change exacerbates, the operational energy demands of these buildings are increasingly influenced by rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and changing precipitation patterns. This necessitates a comprehensive understanding of how different building types respond to future climate scenarios, particularly those defined by the Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) 4.5 and 8.5, which represent moderate and high greenhouse gas emissions scenarios, respectively (Jubb et al., 2013; Österreicher & Seerig, 2024).

The diversity in building typologies significantly affects their energy performance and resilience to climate change. For instance, residential buildings, which include single-family homes and multi-family apartments, exhibit varying energy demands based on their design, materials, and occupancy patterns (Cody et al., 2018). Studies have shown that lightweight steel residential buildings, for example, have distinct operational energy consumption profiles that are sensitive to climatic variations (Santos et al., 2011). Similarly, commercial buildings, which encompass office spaces, retail establishments, and educational facilities, face unique challenges in energy management due to their operational schedules and occupancy behaviors (Azar & Menassa, 2012). The integration of advanced energy modeling techniques is essential for accurately predicting the energy performance of these diverse building types under future climate scenarios (Huang & Gurney, 2016).The integration of advanced energy modeling techniques is essential for accurately predicting the energy performance of these diverse building types under future climate scenarios (Dirks et al., 2015).

As climate change continues to pose challenges to building energy performance, it is imperative to employ simulation-based approaches that account for the unique characteristics of different building types across various U.S. climate zones. By utilizing RCP scenarios to model future energy demands, this study aims to provide valuable insights into the long-term implications of climate change on the energy performance of office buildings, while also considering the broader context of diverse building typologies. This research conducted a simulation-based analysis of office building energy performance under RCP scenarios, which reveals significant regional variations in energy demand driven by climate change.

2. Literature Review

Climate change has emerged as a critical factor influencing the energy performance of buildings. Rising global temperatures, shifting weather patterns, and increased occurrences of extreme climate events necessitate adaptive strategies in building design and energy management (Alhindawi & Jimenez-Bescos, 2020; Apostolopoulou et al., 2023; Behrens et al., 2017; Chidiac et al., 2022). The assessment of climate change impacts on energy demand has become an essential aspect of sustainable urban development and energy policy (Meinshausen et al., 2011; Riahi et al., 2011). As the built environment accounts for a significant proportion of global energy consumption, understanding the vulnerabilities of buildings to climate-induced stressors is imperative (Santamouris & Vasilakopoulou, 2021).

2.1. Impact of Climate Change on Building Energy Demand

Several studies have analyzed the effects of climate change on buildings' heating and cooling demands. Increasing ambient temperatures have led to higher cooling energy consumption, while heating demand has shown a declining trend in many regions (Bell et al., 2022; Berardi & Jafarpur, 2020; Chow & Levermore, 2010; Ortiz et al., 2018). Studies such as those by (Baba & Ge, 2018, 2019)and Xiaoxu et al. (2022) have emphasized how regional variations in climate scenarios influence energy consumption patterns across different building typologies Spinoni et al. (2018)discussed changes in heating and cooling degree-days across Europe, while San José et al. (2020) investigated high-resolution climate scenarios in Madrid. Beyond direct energy demand shifts, climate change also exacerbates urban heat island (UHI) effects, further increasing cooling loads in metropolitan areas (Ortiz et al., 2018). Additional studies by Geissler et al. (2018)and San José et al. (2018) have assessed the impact of prolonged heatwaves on residential and commercial energy usage, revealing the growing necessity for climate-resilient urban planning. The effects of climate change are particularly pronounced in regions with extreme temperature variations, where HVAC systems must operate at higher capacities to maintain indoor comfort (Khourchid et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2017).

2.2. Energy Efficiency Strategies and Mitigation Measures

Energy efficiency interventions have been widely studied as potential mitigation strategies to address climate-induced energy challenges. Altan (2010) assessed the role of energy efficiency measures in UK higher education institutions, whereas Santos et al. (2011) investigated lightweight steel residential buildings' response to changing climate conditions. Various studies have proposed design modifications such as improved shading devices (Lopez-Cabeza et al., 2020), night ventilation strategies (Xiaoxu et al., 2022), and passive cooling techniques (Österreicher & Seerig, 2024). Karmann et al. (2017) analyzed thermal comfort in buildings using radiant versus all-air systems, while Khourchid et al. (2022) reviewed building cooling requirements under climate change scenarios.

Building envelope improvements have also been a major area of research, with studies focusing on insulation materials, reflective coatings, and dynamic facades to regulate indoor temperature variations (Niknia & Rashed-Ali, 2024; Udendhran et al., 2023). The integration of renewable energy sources such as solar photovoltaics and geothermal systems has been emphasized by researchers as a crucial step in reducing dependency on fossil fuel-based energy (Huang & Gurney, 2016; Jenkins et al., 2015). Smart grids and demand response mechanisms have been explored to enhance energy flexibility and efficiency (Leslie et al., 2012; Nimlyat et al., 2014).

2.3. Simulation and Predictive Models

Building performance simulations play a crucial role in predicting the impact of climate change on energy consumption. Duan et al. (2025) conducted a systematic review of challenges associated with thermal building performance simulations under future climate scenarios. Tools such as Energy Plus and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models have been widely used to simulate occupant-driven energy variations (Azar & Menassa, 2012; Leslie et al., 2012; Niknia & Rashed-Ali, 2024). Studies by Dirks et al. (2015) and Kneifel et al. (2015) emphasize the need for regional calibration of simulation models to improve predictive accuracy. Huang and Gurney (2016) discussed the impact of spatiotemporal scales on building energy modeling, while Wang et al. (2017) evaluated predictive climate models for office buildings.

Machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) have been increasingly incorporated into simulation studies to enhance predictive capabilities (Udendhran et al., 2023). AI-driven models have demonstrated greater accuracy in forecasting energy demand fluctuations based on climate variables, occupancy behaviors, and urban heat effects (Ma & Zeng, 2022). These advancements highlight the potential for data-driven energy optimization strategies that integrate real-time environmental data into building management systems (San José et al., 2020).

2.4. Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite significant advancements in understanding climate change’s impact on buildings, several challenges remain. The uncertainty of future climate projections, variability in occupant behavior, and regional disparities in climate adaptation strategies necessitate further (Cody et al., 2018; Elnagar et al., 2023; Huang & Gurney, 2016). Additionally, integrating smart energy consumption control mechanisms using machine learning and IoT (Udendhran et al., 2023) offers promising avenues for optimizing energy efficiency. Geissler et al. (2018) discussed the transition towards energy efficiency policies, while Yau and Hasbi (2013) analyzed climate change impacts on commercial buildings in tropical regions. A key concern is the balance between energy efficiency and occupant comfort, particularly in retrofitting older buildings with modern climate adaptation technologies (Meinshausen et al., 2011; Riahi et al., 2011). Future studies should explore innovative materials with adaptive thermal properties, such as phase-change materials (PCMs), to mitigate climate-related energy impacts (Santamouris & Vasilakopoulou, 2021). Expanding research on low-energy building standards and net-zero energy building (NZEB) frameworks will also be crucial in meeting long-term sustainability goals (Leslie et al., 2012; Santos et al., 2011). As climate change continues to reshape global energy landscapes, buildings must be designed to withstand these transformations. Research has shown that strategic interventions in design, technology, and policy can significantly mitigate the adverse effects of climate change on energy demand (Ma & Zeng, 2022; Santamouris & Vasilakopoulou, 2021). Future studies should focus on refining predictive models, incorporating adaptive energy solutions, and implementing region-specific climate-responsive strategies to enhance building resilience. Integrating advanced AI systems, renewable energy adoption, and regulatory frameworks will be essential in future-proofing the built environment against climate uncertainties.

3. Methodology

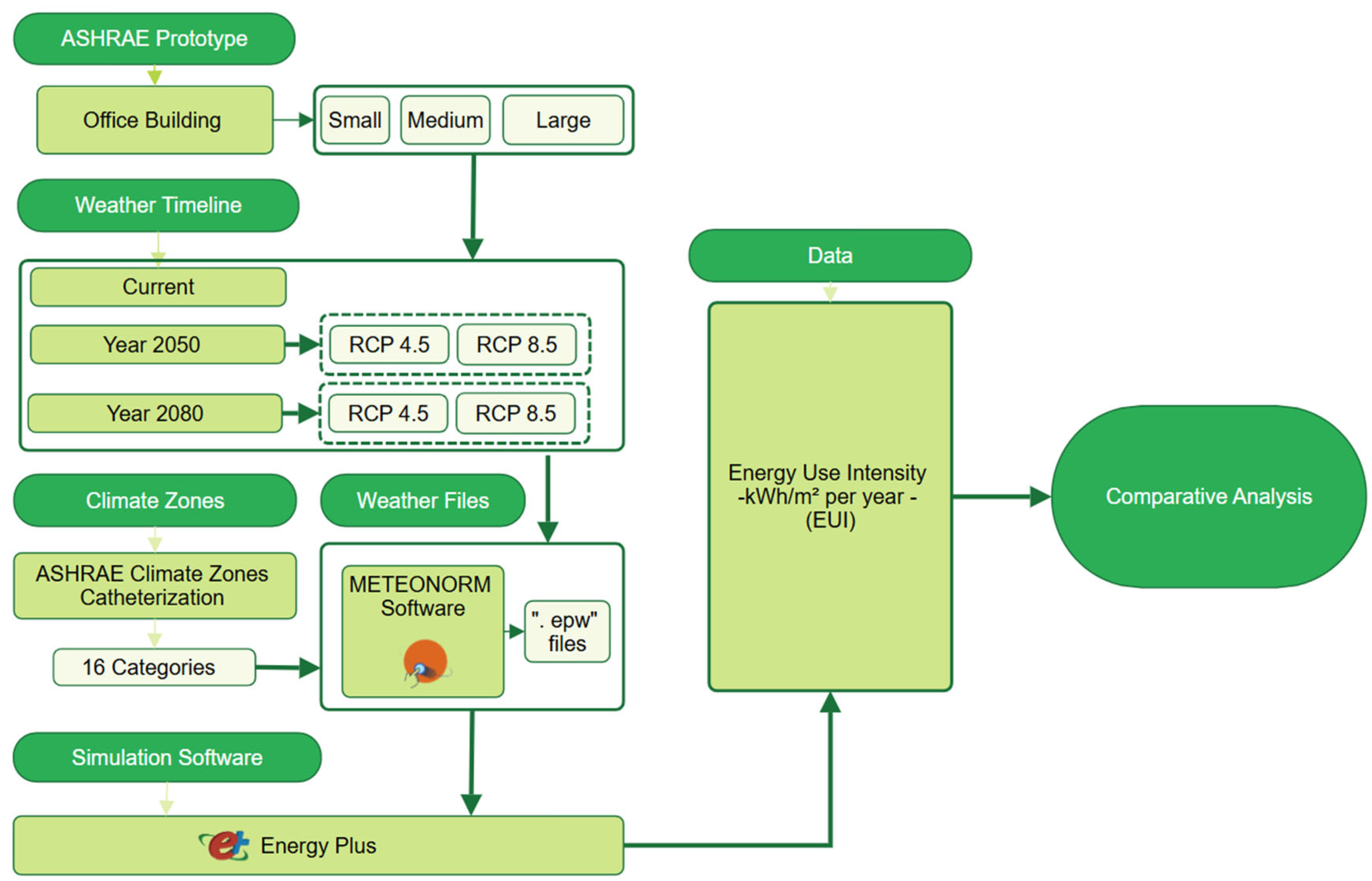

This study aims to evaluate the impact of future climate conditions on the energy performance of office buildings across different climate zones, and the building energy simulations are the accurate way to predict the future. The analysis begins with selecting ASHRAE prototype office buildings, categorized into three sizes: small, medium, and large (DOE, 2020) (

Table 1). These prototypes serve as representative models for energy performance assessment. Climate conditions are analyzed across three time periods—current, 2050, and 2080—considering two future climate scenarios based on Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP): RCP 4.5, which represents a moderate emissions scenario, and RCP 8.5, which assumes a high-emissions future (Jubb et al., 2013).

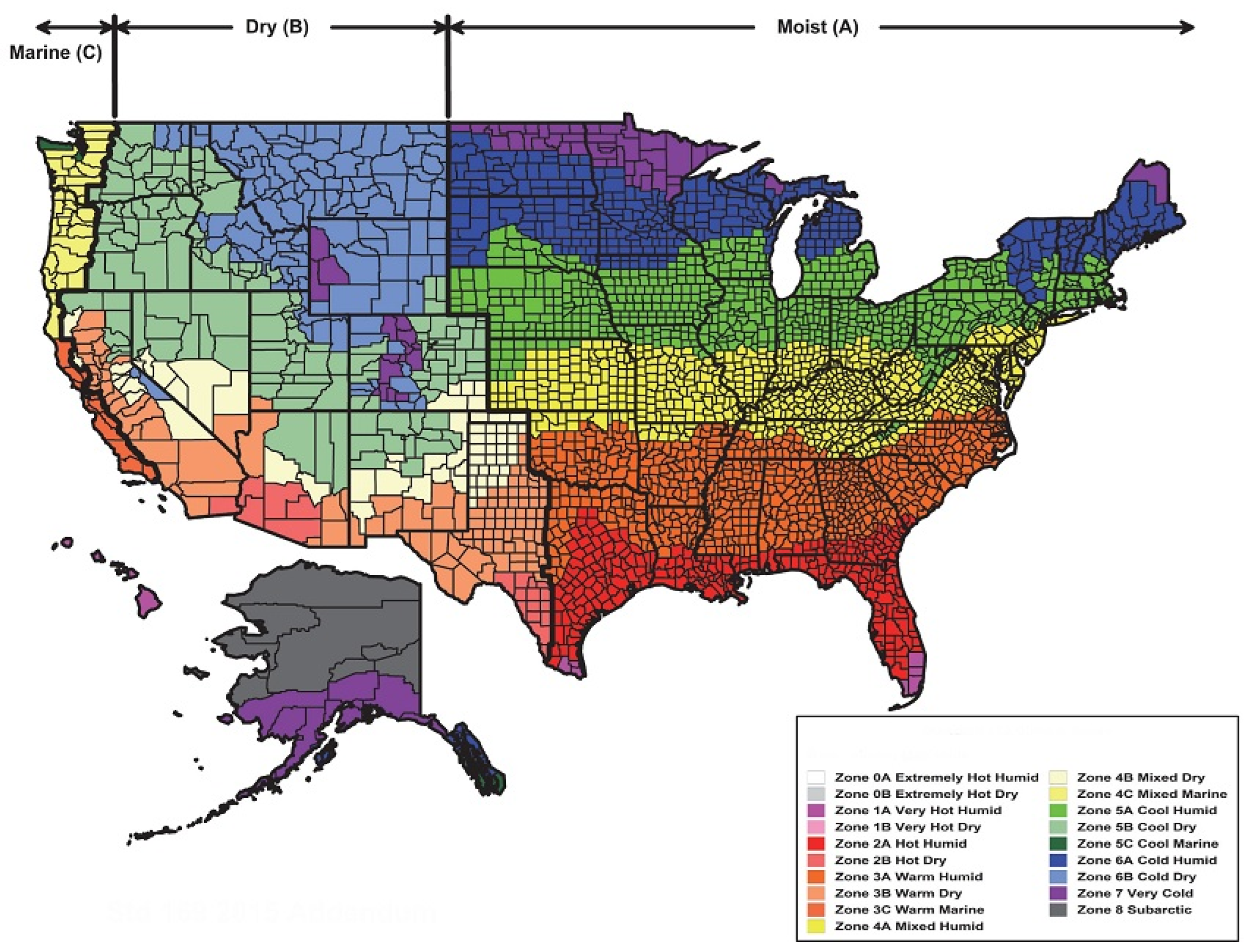

Figure 1 shows geographical variations, climate zones are classified following the ASHRAE climate categorization, covering 16 different zones (Athalye et al., 2017) . Weather data for each zone is generated using METEONORM software (Meteotest, 2023), producing (.epw) weather files necessary for energy simulations. METEONORM is a widely recognized tool that integrates measured climate data with stochastic weather generation techniques, ensuring accurate and representative future climate projections. It is extensively used in building performance research, renewable energy studies, and climate impact assessments.

The Energy Plus simulation software is then used to assess the energy performance of office buildings under different climate scenarios. Energy Plus is a validated, industry-standard building energy modeling tool developed by the U.S. Department of Energy. It provides highly detailed energy simulations by considering heat transfer, HVAC system performance, and occupant behavior, making it a reliable choice for evaluating the impact of climate change on building energy demand. The key outputs of these simulations include Energy Use Intensity (EUI). EUI is a critical performance metric that represents the total energy consumption of a building per unit of floor area, typically expressed in kWh/m² per year (PortfolioManager, 2024). It provides a standardized measure to compare energy efficiency across different buildings and climate conditions. Finally, a comparative analysis is conducted to evaluate variations in energy consumption patterns across different building sizes, climate zones, and periods. This analysis helps identify potential challenges in maintaining energy efficiency and thermal comfort in office buildings as climate conditions evolve. By utilizing validated tools such as METEONORM and Energy Plus, the study ensures robust and reliable results, contributing to the broader understanding of climate change impacts on the built environment (

Figure 2).

4. Overview of Simulations and Baseline EUI

This research draws on Energy Plus simulations of three ASHRAE office prototypes—small, medium, and large—across 16 diverse climate zones in the United States. By capturing distinct climate characteristics, from hot-humid Florida to cold northern regions in Minnesota, the simulations offer a detailed picture of how energy use intensity (EUI) may evolve under future climate scenarios. Baseline EUI values were first established under present conditions, reflecting each climate zone’s typical heating and cooling demands. Generally, current EUI levels tend to be highest for larger office buildings, due to their extensive floor areas and longer operational hours. However, medium-sized offices can sometimes approach similar consumption per square-foot because of higher occupant densities and equipment loads. Small offices typically post the lowest total EUI, yet local climate conditions cause notable variations. In regions with severe winters, heating dominates overall energy use, while in warm or humid climates, cooling can represent the largest fraction of consumption. These baseline results set the stage for understanding how different office types might respond to changes in temperature and humidity as projected by RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios for 2050 and 2080.

4.1. Small Office Prototype Results

4.1.1. Changes by 2050

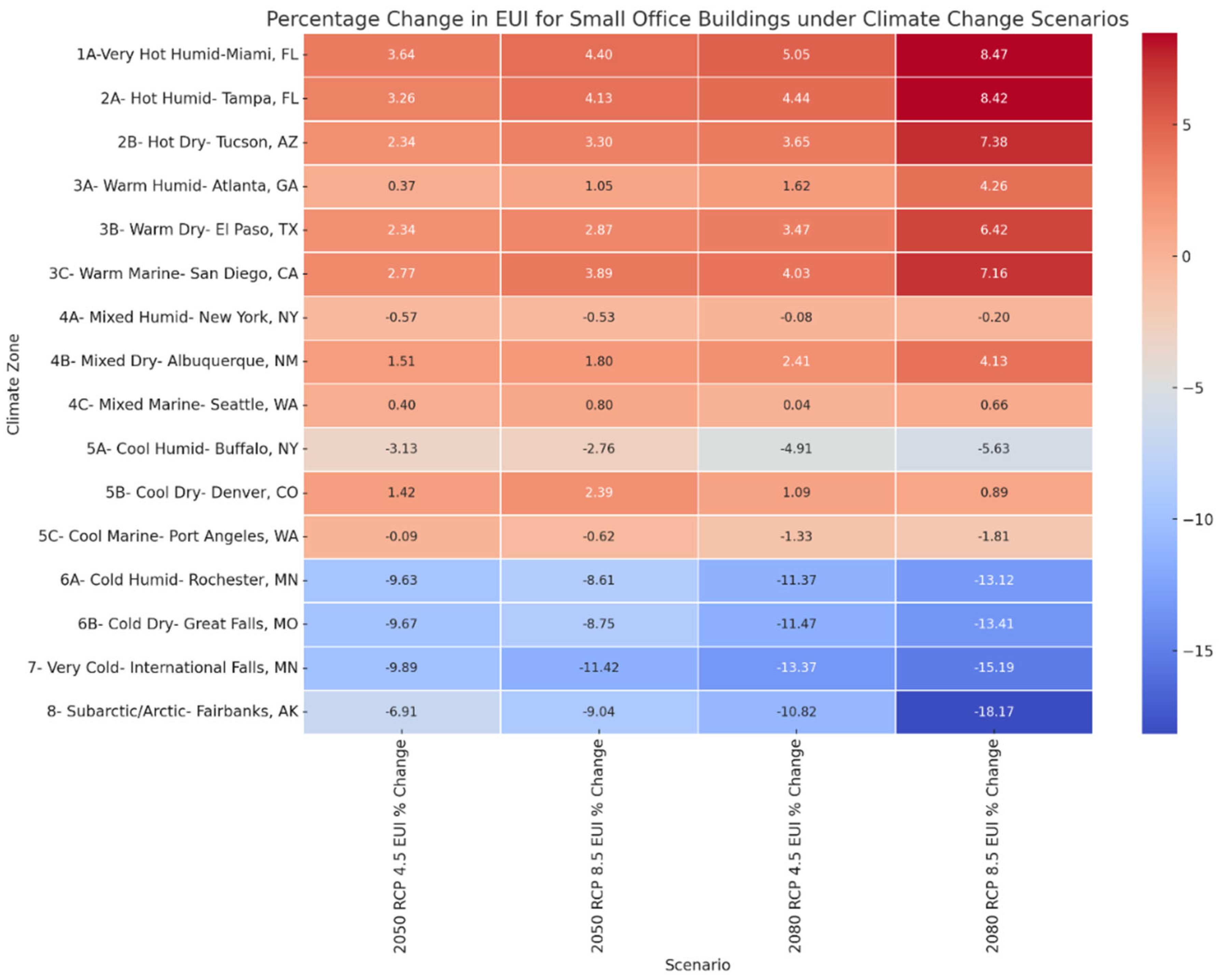

In looking toward 2050, small office buildings show relatively moderate shifts in energy use across the 16 climate zones. Under the RCP 4.5 scenario—considered a middle-range climate pathway—many regions that already experience warm summers, such as cities in the southeastern United States (e.g., Miami), see a gentle rise in overall EUI (typically 2–8%). This increase stems from more frequent or intense cooling requirements, as even modest temperature rises can push cooling equipment to run longer or start earlier in the year.

Table 2.

Small Office Building Energy Use Intensity Result. Source (Author 2025).

Table 2.

Small Office Building Energy Use Intensity Result. Source (Author 2025).

| CLIMATE ZONE |

CURRENT |

2050 |

2080 |

| RCP 4.5 EUI(kBtu/f2) |

RCP 8.5 EUI(kBtu/f2) |

RCP 4.5 EUI(kBtu/f2) |

RCP 8.5 EUI(kBtu/f2) |

| 1A-Very Hot Humid-Miami, FL |

27.5 |

28.5 |

28.71 |

28.89 |

29.83 |

| 2A- Hot Humid- Tampa, FL |

26.38 |

27.24 |

27.47 |

27.55 |

28.6 |

| 2B- Hot Dry- Tucson, AZ |

26.03 |

26.64 |

26.89 |

26.98 |

27.95 |

| 3A- Warm Humid- Atlanta, GA |

24.65 |

24.74 |

24.91 |

25.05 |

25.7 |

| 3B- Warm Dry- El Paso, TX |

24.78 |

25.36 |

25.49 |

25.64 |

26.37 |

| 3C- Warm Marine- San Diego, CA |

22.35 |

22.97 |

23.22 |

23.25 |

23.95 |

| 4A- Mixed Humid- New York, NY |

24.66 |

24.52 |

24.53 |

24.64 |

24.61 |

| 4B- Mixed Dry- Albuquerque, NM |

24.44 |

24.81 |

24.88 |

25.03 |

25.45 |

| 4C- Mixed Marine- Seattle, WA |

22.64 |

22.73 |

22.82 |

22.65 |

22.79 |

| 5A- Cool Humid- Buffalo, NY |

26.48 |

25.65 |

25.75 |

25.18 |

24.99 |

| 5B- Cool Dry- Denver, CO |

24.72 |

25.07 |

25.31 |

24.99 |

24.94 |

| 5C- Cool Marine- Port Angeles, WA |

22.61 |

22.59 |

22.47 |

22.31 |

22.2 |

| 6A- Cold Humid- Rochester, MN |

31.48 |

28.45 |

28.77 |

27.9 |

27.35 |

| 6B- Cold Dry- Great Falls, MT |

31.55 |

28.5 |

28.79 |

27.93 |

27.32 |

| 7- Very Cold- International Falls, MN |

34.77 |

31.33 |

30.8 |

30.12 |

29.49 |

| 8- Subarctic/Arctic- Fairbanks, AK |

42.81 |

39.85 |

38.94 |

38.18 |

35.03 |

Interestingly, in cold northern zones like Minneapolis or Buffalo, the slight reduction in wintertime heating load often offsets any extra summertime cooling, resulting in net EUI changes that hover around -1% to -4%. In climate zones with comparatively mild temperatures (e.g., parts of the Pacific Northwest), baseline cooling and heating demands are already balanced, so future changes remain modest—often under ±2%. These smaller offices thus exhibit a balancing act, where reductions in another (heating) partially compensate gains in one end-use (cooling). Under the higher-emissions RCP 8.5 scenario for 2050, the patterns remain similar but tend to be more pronounced. Hotter climates may see EUI jump by 5–12%, while cold regions often land between a slight decrease (around -2%) and a small increase (around +3%). In many temperate locations, overall changes remain near-neutral as heating reductions and cooling increases largely counterbalance each other. Overall, the 2050 projections suggest that small offices are sensitive to warm climates, but the exact magnitude of the shift depends strongly on each zone’s baseline weather profile (

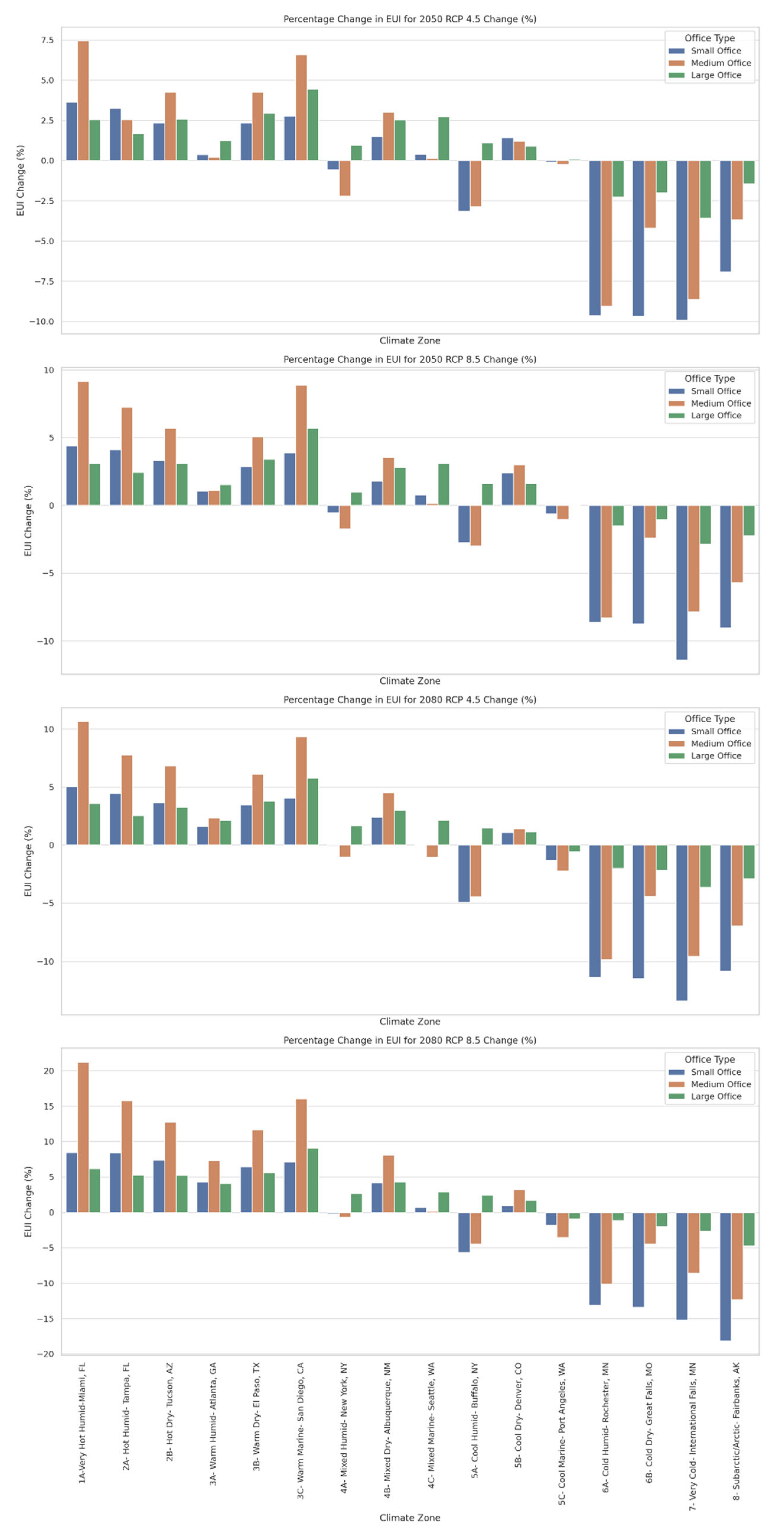

Figure 3).

4.1.2. Changes by 2080

By 2080, small offices under RCP 4.5 show a continued expansion of these trends. For example, hot-humid regions—Florida or coastal Texas—start to exhibit more noticeable spikes, sometimes surpassing a 10% increase in EUI relative to the current baseline. Meanwhile, previously cold areas might see slightly bigger savings on heating, though new or expanded cooling needs can partly offset those gains. The net effect is that northern locations may range from modestly reduced EUI to near baseline levels (within about ±5%). Under RCP 8.5 in 2080, the difference is more dramatic. Many hot climate zones see EUI climb by at least 15%, fueled by pronounced cooling requirements in longer, more intense heat waves. Though benefiting from milder winters, even parts of the northern United States start encountering enough extra summer cooling to end up with near-stable or slightly increased overall EUIs. A handful of coastal or marine climates remain relatively insulated from extreme swings, showing EUI changes of perhaps ±3%. Despite variations, it is clear that small office buildings in hot climates bear the brunt of climate-induced energy demand increases over the next several decades (

Figure 3).

4.2. Medium Office Prototype Results

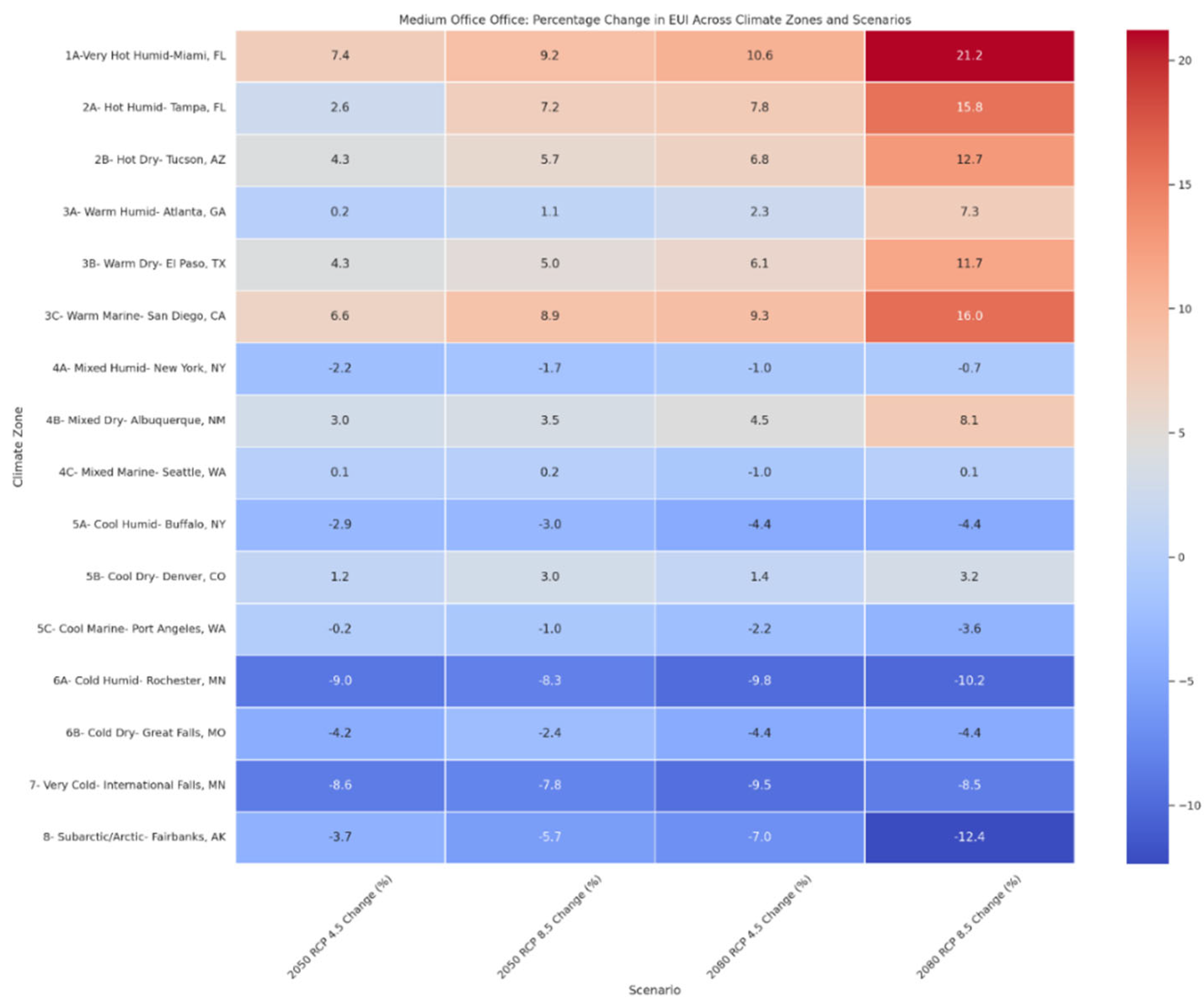

4.2.1. Changes by 2050

Medium-sized offices broadly follow similar patterns, though the magnitude of change is often more noticeable, both absolute and in percentage terms. Under RCP 4.5 in 2050, buildings in very warm climates typically register EUI increases of 3–9%, underscoring the stronger cooling demands for these somewhat larger structures. Meanwhile, cold regions could see a decrease in heating, sometimes bringing net results in the range of -3% to +2%. Cities with moderate or marine climates exhibit relatively minor changes. However, the bigger occupant loads and internal gains in medium offices can still amplify the effect of slight outdoor temperature shifts (

Table 3).

Under RCP 8.5 by 2050, the pattern of increased cooling demand intensifies, particularly in locations like Texas, Arizona, or Florida. Some places may see EUI growth creep above 10%, indicating sustained or peak cooling loads during summer months. Yet in certain parts of the Midwest or Northeast, the net changes can still be limited or near neutral, as milder winters bring heating savings that partially balance out higher summer cooling (

Figure 4).

4.2.2. Changes by 2080

Moving forward to 2080, RCP 4.5 shows a continued but moderate upward pull in EUI within hot climates, often landing in the 8–12% range compared to current conditions. Zones already accustomed to cold winters record reductions in heating energy, although they may also contend with enough added cooling to temper these gains, resulting in net changes of around -4% to +4%. Marine climates once again tend to remain near baseline values, with fewer temperature extremes. Under the higher RCP 8.5 projections for 2080, medium offices in consistently hot conditions can climb above a 15% boost in EUI, highlighting the strain of more intense or extended cooling seasons. Northern locations see meaningful declines in heating needs, but these are not always sufficient to counterbalance new summer cooling loads. As such, while medium-sized offices often display the largest percentage changes among the three prototype sizes, the specific outcome in each city largely depends on whether climate extremes are more winter- or summer-oriented (

Figure 5).

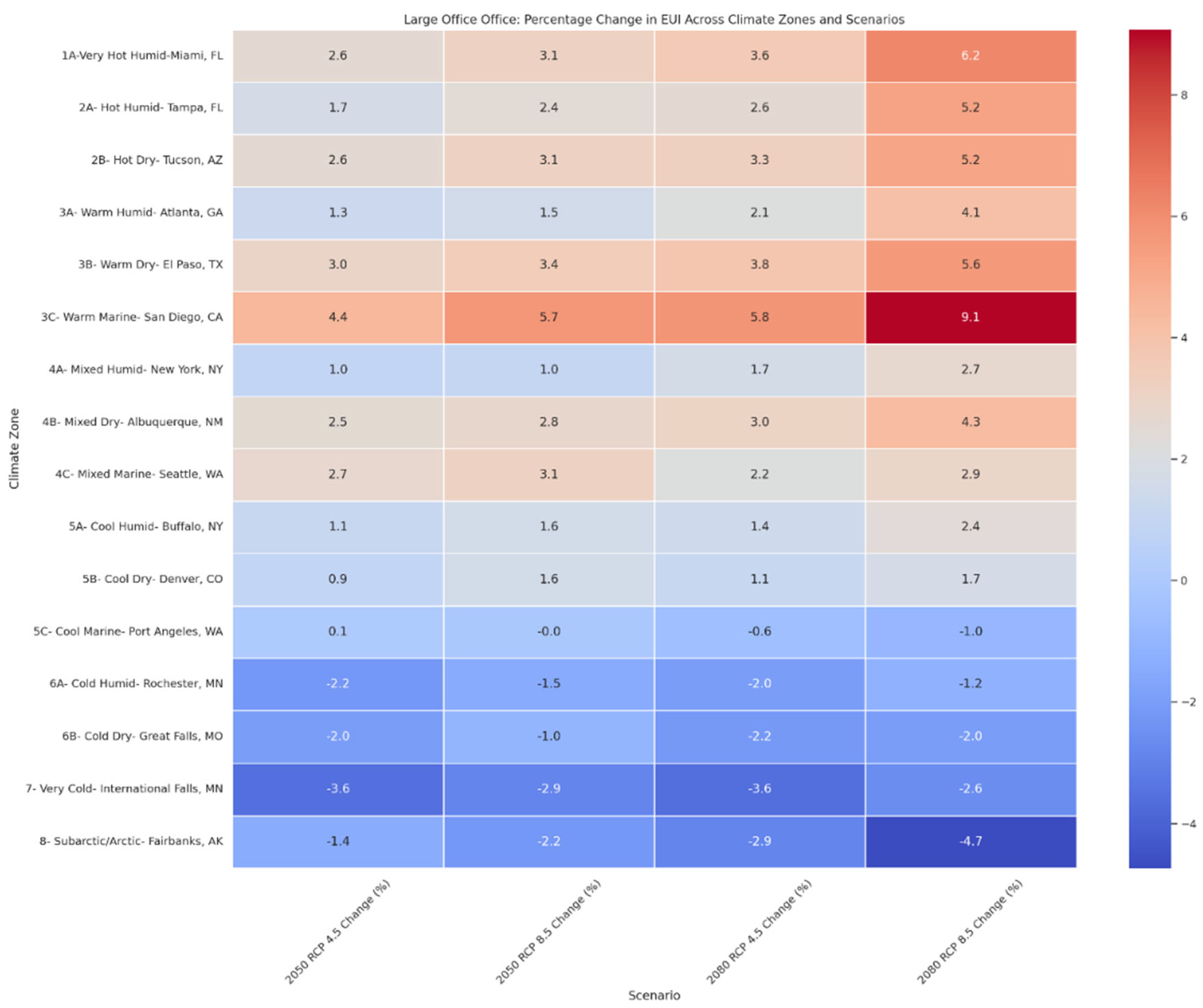

4.3. Large Office Prototype Results

4.3.1. Changes by 2050

Large offices, known for advanced HVAC systems and significant internal equipment loads, present a slightly different picture. In 2050 under RCP 4.5, most hot-humid locations register EUI increases around 2–7%, which may be lower on a percentage basis compared to medium offices. However, in absolute terms, large offices can consume noticeably more energy overall because of their bigger footprint. Colder areas often see net decreases of about -1% to -5% due to cuts in heating demands, though the addition of warmer summers contributes to some variability. In moderate zones, large offices can remain close to current EUI values (within ±2%), suggesting that strong internal loads and efficient centralized systems buffer some of the outdoor climatic changes. Under RCP 8.5 for 2050, large offices in warm climates typically see a somewhat greater jump, often up to 10% above baseline. Winter-driven climates may experience net EUI reductions in the range of -2% to -6%, once again reflecting the shifting balance between heating and cooling. Where summers are becoming substantially warmer, the required cooling can noticeably blunt the wintertime energy savings (

Table 4).

4.3.1. Changes by 2080

By 2080 under RCP 4.5, large offices in the hottest parts of the country often experience EUI increases of 8–12%, in line with a more demanding cooling season. Meanwhile, places with cold winters stand to reduce heating by a further margin, sometimes generating total EUIs about 3–6% below current levels. Marine or coastal climates remain close to present-day EUI figures, sometimes deviating by less than 3%. Under RCP 8.5, hotter and more humid regions frequently push large office EUIs into a 12–15% increase by 2080. While winter demand continues to drop in cold locations, the need for extra summer cooling can narrow the net savings. In many instances, large offices show slightly less extreme percentage changes than medium-sized offices, but because of their size, the absolute rise in energy consumption can still be considerable (

Figure 5).

4.4. Cross-Comparison by Climate Zone

Comparing how climates respond across all office prototypes yields a consistent pattern. Places already experiencing high summer temperatures—such as Florida, Texas, and parts of the Southwest—tend to show the greatest proportional or absolute EUI gains. Colder northern states often enjoy net heating reductions, though any air conditioning surge can limit the extent of these savings. Some coastal or marine climates (e.g., Seattle, San Francisco) keep overall changes modest, typically remaining within 2–4% of baseline levels, even under more aggressive climate projections. Not surprisingly, RCP 8.5 scenarios reveal larger impacts than RCP 4.5, particularly by 2080, when warming patterns become increasingly established. Although the scale differs among building sizes, the direction of the trends remains the same: warmer climates face intensifying cooling demands. At the same time, colder regions see diminishing heating needs, with some balancing effects in temperate areas.

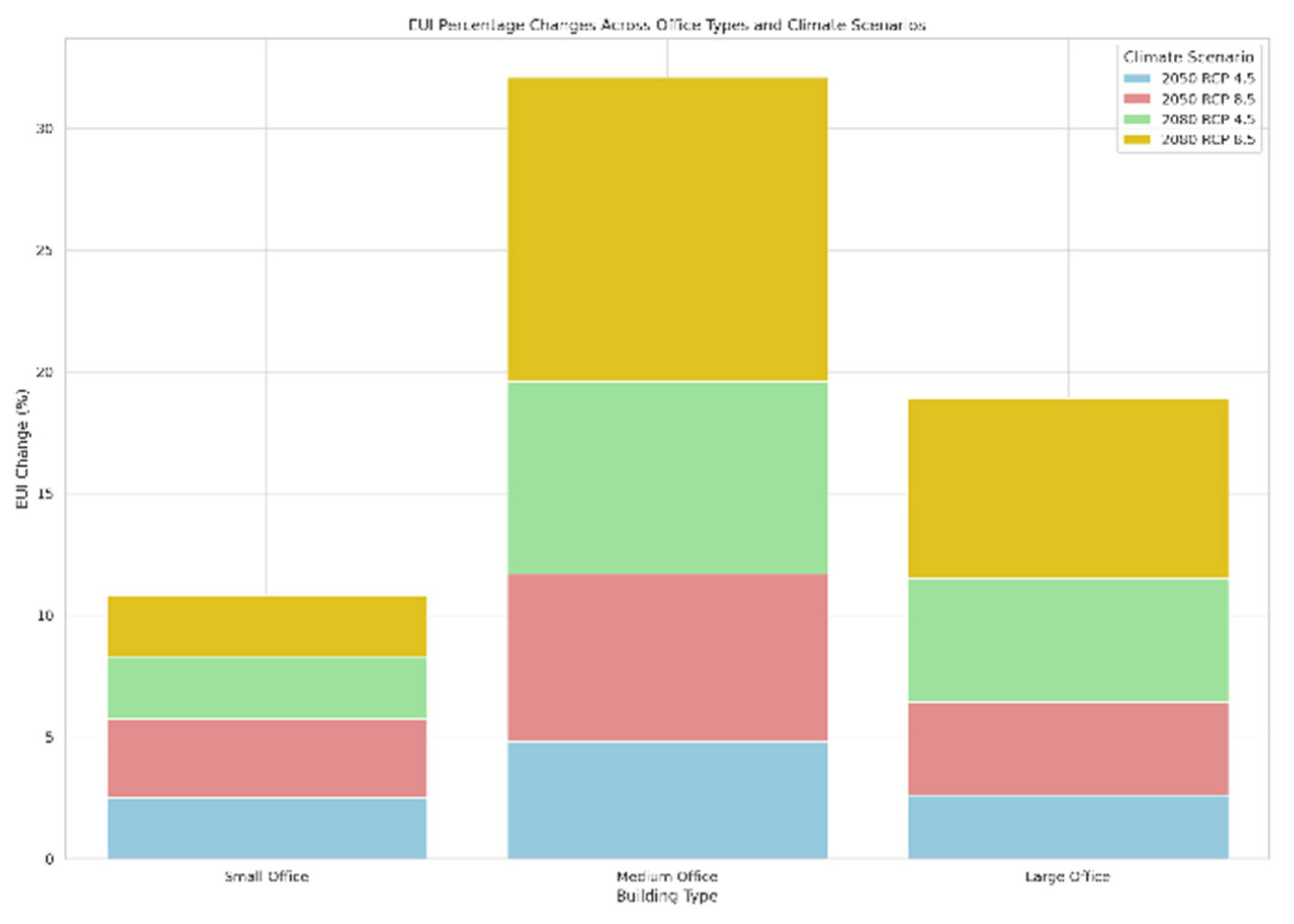

4.5. Comparative Analysis Among Office Types

A key factor in comparing the three office prototypes—small, medium, and large—is the magnitude of change they experience. Small offices typically exhibit moderate percentage increases in hot climates and mild decreases in traditionally cold regions. Their smaller footprint, however, can magnify temperature-driven swings in energy demand, especially in cold areas, although the overall changes remain relatively contained. Medium offices often show the most dramatic percentage increases in warm zones, likely due to higher occupant densities and greater internal loads. Large offices, by contrast, tend to benefit from centralized and sometimes more efficient HVAC systems. As a result, their percentage increases in EUI can appear lower than those in medium offices. Still, the total energy consumption of large buildings is high enough that even small percentage changes translate into significant absolute impacts.

Climate sensitivity across different regions reveals similar trends. In hot-humid or hot-dry environments, all three office sizes see notable increases in cooling demands, but medium and large prototypes generally require a more pronounced capacity shift than their baseline. In cold northern areas, there is typically a substantial drop in heating energy use, producing net EUI savings that can be mitigated, to varying degrees, by additional cooling requirements during ever-warming summers. Meanwhile, with moderate year-round temperatures, marine or coastal climates tend to show smaller overall fluctuations in EUI for any office type. Combining these factors, medium-sized offices emerge as the most reactive in percentage changes, large offices risk the highest absolute increases, and small offices generally fall between the two, with outcomes heavily influenced by local climate characteristics (

Figure 6).

5. Discussion

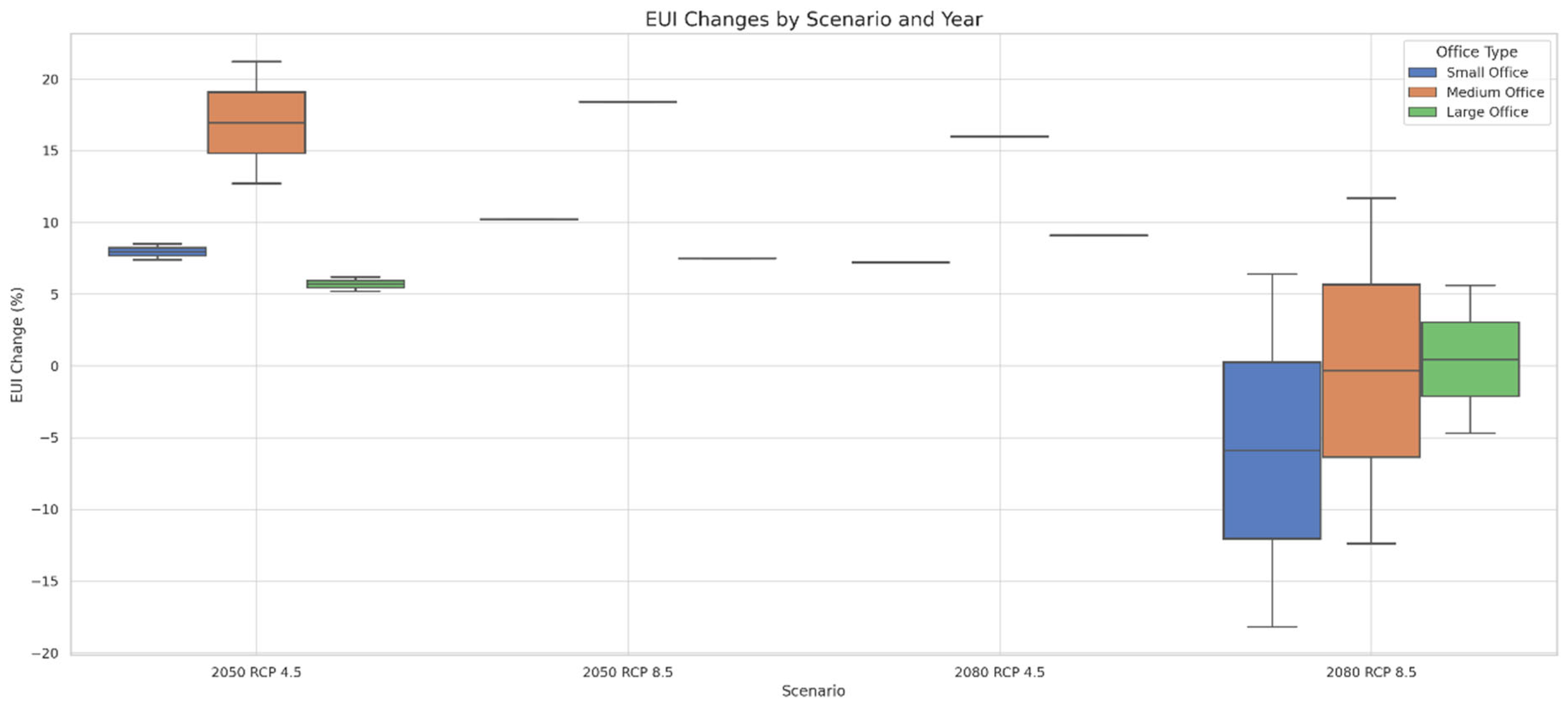

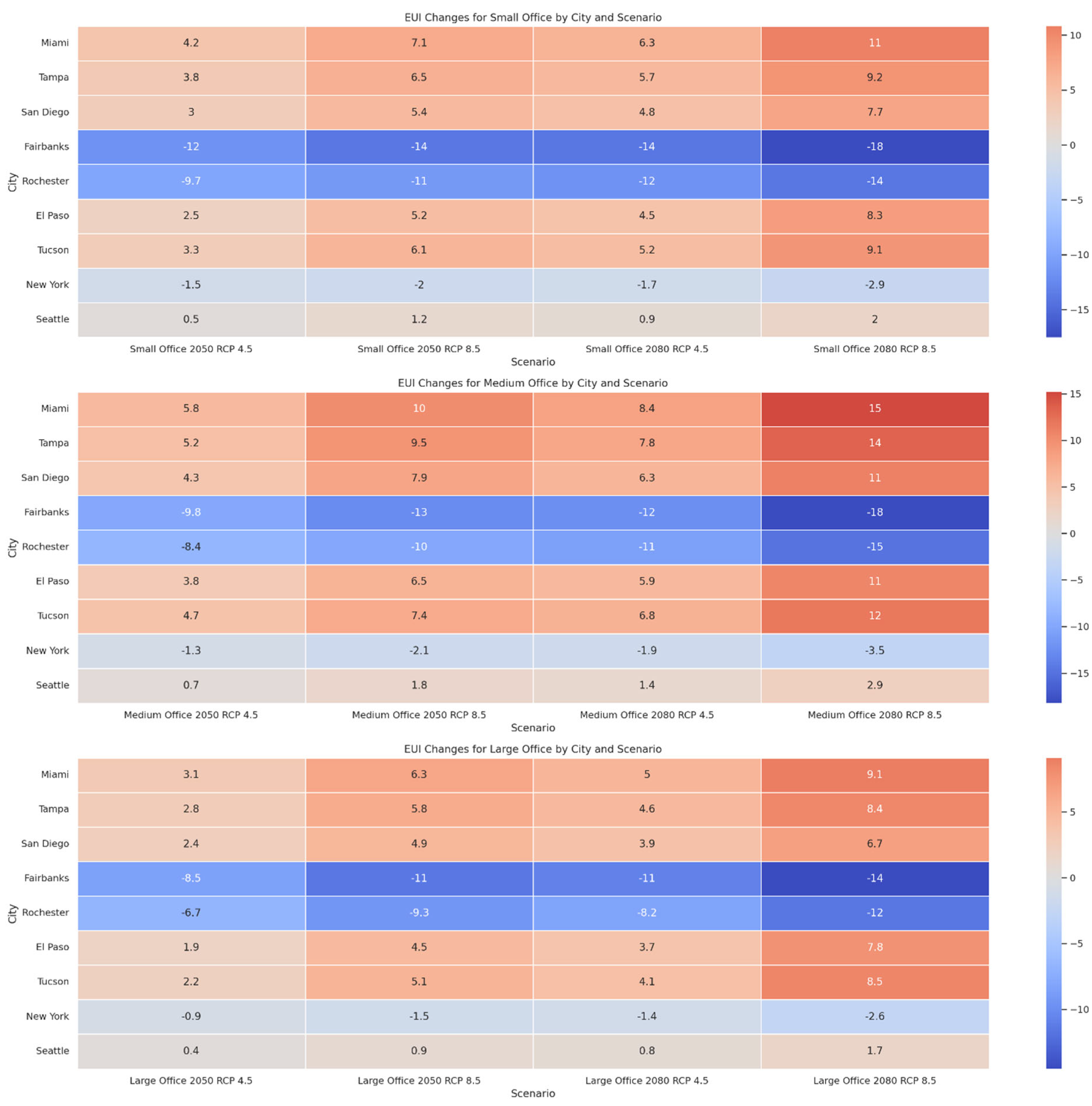

Considering energy usage intensity (EUI) for small, medium, and large office buildings under prospective climate scenarios demonstrates considerable disparities among building types, climate zones, and emission trajectories. The results highlight the intricate link between climatic circumstances and building energy efficiency, revealing significant inequality between the RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios. This analysis examines the findings concerning the three principal research inquiries: (1) how climate change scenarios influence energy consumption across various climatic zones, (2) which office type is most significantly affected, and (3) which climate zones are most influenced for each office type.

Climate change forecasts under RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 illustrate the impact of future warming on energy consumption trends in office buildings. In all construction categories, the tendency is evident: warmer areas encounter rising cooling energy requirements, whilst colder places see decreases owing to milder winters. The average Energy Use Intensity (EUI) for small office buildings exhibits a marginal decrease in RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios between 2050 and 2080. This decline signifies an equilibrium between increasing cooling requirements and diminishing heating demands. Nonetheless, geographical disparities are significant. Miami, FL, anticipates the most significant increase, with an 8.5% jump by 2080 under RCP 8.5, attributed to heightened cooling demands. Comparable gains are noted in Tampa, FL (8.4%) and San Diego, CA (7.2%). In contrast, northern areas like Fairbanks, AK, have significant declines, achieving -18.2% by 2080 under RCP 8.5, along with International Falls, MN (-15.2%) and Great Falls, MT (-13.4%). These decreases align with the findings of Isaac and Van Vuuren (2009), who emphasized that cold locations benefit from warmer winters due to decreased heating energy requirements.

Medium-sized office buildings have heightened susceptibility to climate change. By 2080, under the RCP 8.5 scenario, the Energy Use Intensity (EUI) escalates markedly, averaging 12.5%, with Miami, FL, exhibiting the most substantial increase at 21.2%, succeeded by San Diego, CA (16.0%) and Tucson, AZ (12.7%). The significant increase in these areas indicates the prevalence of cooling energy in warm settings. Colder areas, including Fairbanks, AK (-12.4%), Rochester, MN (-10.2%), and International Falls, MN (-8.5%), exhibit significant decreases, suggesting that future heating requirements will persist in diminishing.

Large office buildings exhibit minor fluctuations compared to small and medium-sized offices. By 2080, under RCP 8.5, the average Energy Use Intensity (EUI) increase is projected to be 7.4%, with San Diego, CA (9.1%), Miami, FL (6.2%), and El Paso, TX (5.6%) exhibiting the most pronounced increases. The durability of large office buildings is due to their sophisticated HVAC systems, thermal mass, and effective building envelopes. Simultaneously, cold-climate cities such as Fairbanks, AK (-4.7%), International Falls, MN (-2.6%), and Rochester (-1.2%) persist in observing moderate reductions in Energy Use Intensity (EUI).

The box plot study (

Figure 7) corroborates this conclusion by depicting EUI variations among RCP scenarios and years. In 2080, under RCP 8.5, medium office buildings in Miami, San Diego, and Tucson exhibit the most substantial increases, whereas Fairbanks and other frigid regions see continuous decreases. This image substantiates the conclusion that the intensity of climate change in high-emission scenarios escalates energy requirements in the warm areas, mainly for medium-sized office buildings. Considering energy usage intensity (EUI) for small, medium, and large office buildings under prospective climate scenarios indicates substantial discrepancies among building categories, climatic regions, and emission trajectories. The results highlight the intricate link between climatic circumstances and building energy efficiency, revealing significant disparities between the RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios.

Among the three types of office buildings, medium-sized ones are the most affected by prospective climate change scenarios. By 2080, under RCP 8.5, the average Energy Use Intensity (EUI) for medium-sized offices is projected to increase by 12.5%, while large offices will experience a 7.4% increase, and tiny offices would see a minor drop of 2.5%. This increased sensitivity is due to the design features of medium office buildings, which often exhibit greater internal heat gains and bigger conditioned areas than small offices but lack the thermal mass and sophisticated systems seen in large office buildings. To assess the impact across cities, the heatmaps (

Figure 8) indicate that Miami, FL (21.2%), San Diego, CA (16.0%), and Tucson, AZ (12.7%) demonstrate the most significant increases in EUI for midsize offices under RCP 8.5 by 2080. Conversely, Fairbanks, AK (-18.2%), Rochester, MN (-14.8%), and International Falls, MN (-12.4%) exhibit the most significant declines, indicating diminished energy demands as winters grow milder (

Figure 9).

The ANOVA results additionally corroborate the notion of sensitivity to building type. Despite the statistical test yielding a p-value of 0.506, which suggests that the variations in EUI changes among building types lack statistical significance at the 95% confidence level, the absolute EUI changes demonstrate considerable variances. Medium office buildings consistently exhibit the most significant percentage increases in hot and humid conditions, whereas small and big office buildings display higher resistance. This indicates that although the statistical variation among building types may be minimal, the practical ramifications for energy consumption and operational expenses are substantial. The influence of climatic change on EUI differs markedly among climate zones. Hot and humid regions, specifically Climate Zones 1A and 2A, constantly have elevated Energy Use Intensity (EUI), whereas cold and subarctic regions, namely Climate Zones 7 and 8, benefit from diminished heating demands.

Summary of Discussion

The projected impact of climate change on the Energy Use Intensity of small office buildings reveals significant variations across different climate zones and future scenarios. On average, EUI is expected to decrease slightly in 2050 and 2080 under the RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios. Specifically, by 2050, the average EUI is projected to decline by approximately 2.03% under RCP 4.5 and 1.85% under RCP 8.5 compared to current levels. By 2080, these reductions are anticipated to be around 2.64% and 2.58% for RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5, respectively (Figure 10). These modest reductions can be attributed to the complex interplay between decreased heating demands and increased cooling requirements as global temperatures rise. In warmer climates, the reduction in heating energy use often outweighs the increase in cooling energy consumption, leading to a net decrease in total energy use. This phenomenon has been observed in previous studies, such as the work by Wang and Chen (2014) which demonstrated that while cooling energy consumption is expected to rise due to global warming, the overall energy use may decline in certain regions because of more significant reductions in heating demands.

However, this average trend does not capture the variability observed across different climate zones. Among all climate zones, the highest increase in EUI is observed in Miami, FL (Climate Zone 1A), a very hot and humid region. Under the RCP 8.5 scenario 2080, the EUI rises by approximately 8.47% compared to the current state, reaching 29.83 kBtu/ft². This increase is primarily driven by the escalating cooling demands required to maintain indoor comfort as temperatures continue to rise. Similar trends, though slightly less pronounced, are seen in the 2050 projections, where the same climate zone experiences a 4.4% increase in EUI under RCP 8.5 and 3.6% under RCP 4.5. These findings align with previous studies indicating that hot-humid climates will experience intensified cooling loads under future warming conditions (Choi et al., 2012; Santamouris et al., 2017).

Conversely, the most significant reduction in EUI is observed in Fairbanks, AK (Climate Zone 8), a subarctic region. By 2080, under the RCP 8.5 scenario, the EUI is projected to decrease by 18.17%, dropping to 35.03 kBtu/ft². This reduction can be attributed to the diminishing heating requirements as winters become milder, a trend also noted in research by Crawley (2008), who highlighted the potential for substantial energy savings in cold climates under future warming scenarios. Similarly, International Falls, MN (Climate Zone 7), known for its very cold climate, experiences significant EUI reductions, with a 15.18% decrease under RCP 8.5 by 2080. The 2050 projections show a comparable trend, with reductions of 9.89% under RCP 4.5 and 11.42% under RCP 8.5. These findings further underscore the regional disparities in climate change impacts, where colder regions benefit from reduced heating demands while hotter regions face increased cooling burdens (Isaac & Van Vuuren, 2009).

The results highlight the need for climate-responsive building designs tailored to specific regions. In hot-humid zones like Miami, prioritizing advanced cooling strategies and high-performance building envelopes will be essential to mitigate rising energy demands. Thus, optimizing heating systems for milder winters can further enhance energy efficiency in colder regions like Fairbanks and International Falls. As the climate continues to evolve, understanding these region-specific impacts will be crucial for developing resilient and sustainable building practices (Attia et al., 2012).

6. Conclusions

The Energy Use Intensity (EUI) analysis underscores the profound impact of climate change on building energy consumption across different office types and climate zones. The findings highlight the growing disparity between warming and cooling energy demands, with hot-humid regions facing escalating cooling requirements, while colder areas benefit from reduced heating demands. Among the three office building types, medium-sized office buildings emerge as the most vulnerable category, exhibiting the highest EUI increases under high-emission scenarios, particularly in warm climates such as Miami, San Diego, and Tucson. This heightened sensitivity is attributed to their larger conditioned areas and internal heat gains compared to small offices. Yet, they lack the thermal mass and advanced HVAC systems that contribute to the resilience of large office buildings.

This research illustrates the effects of climate change on office buildings, providing crucial insights into regional energy consumption trends. Cities with hot and humid climates, including Miami, Tampa, and Tucson, exhibit the most significant rises in EUI under projected climatic scenarios, especially for medium office buildings. Large office buildings, while still affected by climate change, demonstrate more stable energy consumption trends due to their more sophisticated mechanical systems and enhanced insulation properties. Conversely, small office buildings exhibit relatively moderate changes in EUI, with some cases experiencing slight declines as reduced heating demands offset the increase in cooling requirements.

This increased vulnerability underscores the pressing need for more sustainable design methodologies integrating passive measures to diminish cooling loads and improve energy efficiency. Passive design strategies, including optimum building orientation, sophisticated shading systems, natural ventilation, and high-performance building envelopes, can substantially reduce the energy demands associated with rising temperatures. Additionally, advancements in energy-efficient HVAC systems, thermal insulation technologies, and smart building automation can further enhance building resilience against extreme climatic conditions.

Furthermore, the findings underscore the imperative for revised building regulations and standards, particularly in climate-sensitive areas, to ensure that forthcoming construction and retrofitting procedures conform to climate resilience objectives. Given their heightened vulnerability to climate change, medium-sized office buildings require particular attention in regulatory updates. Implementing stricter energy efficiency codes, enhanced cooling strategies, and thermal performance standards for medium-sized office buildings in hot and humid climates will be crucial to mitigating future energy demands. Large office buildings, while more resilient, can also benefit from regulations promoting renewable energy integration and smart energy management systems. Small office buildings, experiencing relatively minor variations, may require targeted strategies focusing on cost-effective retrofitting measures to enhance overall efficiency.

As climate change escalates, it is essential to integrate resilience into architectural and regulatory frameworks to safeguard energy systems and urban infrastructure. Future designs must prioritize energy efficiency and climate adaptation strategies, leveraging technological innovations such as adaptive facades, renewable energy integration, and predictive energy modeling. Given these projected shifts, adapting building design to climate-compatible solutions becomes imperative. Policymakers and stakeholders must take proactive measures to ensure that future office buildings remain energy-efficient and sustainable despite the uncertainties of climate change. Collaboration between government agencies, industry leaders, and researchers will be essential in developing policies that promote resilient and adaptable building practices, ultimately ensuring a sustainable future for office buildings in an increasingly dynamic climate landscape.

Directions for Future Research

Future studies could incorporate more granular occupant data to refine these insights further, exploring how daily and seasonal occupancy fluctuations shape real-time cooling and heating loads. Hourly or sub-hourly simulations might uncover the severity of peak critical for grid stability and for sizing equipment like chillers and thermal energy storage. Linking building energy models to electrical grid models would also help stakeholders understand how escalating peak cooling demands might stress local power infrastructure and create resilience challenges. Moreover, expanded research on adaptation strategies—such as shading retrofits, dynamic glazing systems, or on-site renewable integration—would help quantify cost-benefit trade-offs under rising cooling loads. Investigating other building types beyond offices (e.g., retail, healthcare, education) could present a more holistic picture of the commercial sector’s vulnerability to climate change and sharpen state and national energy policy recommendations.

References

- Alhindawi, I.; Jimenez-Bescos, C. Assessing the Performance Gap of Climate Change on Buildings Design Analytical Stages Using Future Weather Projections. Sci. J. Riga Tech. Univ. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2020, 24, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altan, H. Energy efficiency interventions in UK higher education institutions. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7722–7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, A.; Jimenez-Bescos, C.; Cavazzi, S.; Boyd, D. Impact of Climate Change on the Heating Demand of Buildings. A District Level Approach. Sci. J. Riga Tech. Univ. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2023, 27, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athalye, R., Halverson, M., Rosenberg, M., Liu, B., Zhang, J., Hart, R., Mendon, V., Goel, S., Chen, Y., & Xie, Y. (2017). Energy Savings Analysis: ANSI/ASHRAE/IES Standard 90.1-2016.

- Attia, S.; Evrard, A.; Gratia, E. Development of benchmark models for the Egyptian residential buildings sector. Appl. Energy 2012, 94, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, E., & Menassa, C. (2012). Sensitivity of energy simulation models to occupancy related parameters in commercial buildings. Construction Research Congress 2012: Construction Challenges in a Flat World. C.

- Baba, F.M.; Ge, H. Effect of climate change on the annual energy consumption of a single family house in British Columbia. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 251, 03018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, F.M.; Ge, H. Effect of climate change on the energy performance and thermal comfort of high-rise residential buildings in cold climates. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 282, 02066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, P.; van Vliet, M.T.H.; Nanninga, T.; Walsh, B.; Rodrigues, J.F.D. Climate change and the vulnerability of electricity generation to water stress in the European Union. Nat. Energy 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, N.; Bilbao, J.; Kay, M.; Sproul, A. Future climate scenarios and their impact on heating, ventilation and air-conditioning system design and performance for commercial buildings for 2050. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, U.; Jafarpur, P. Assessing the impact of climate change on building heating and cooling energy demand in Canada. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidiac, S.E.; Yao, L.; Liu, P. Climate Change Effects on Heating and Cooling Demands of Buildings in Canada. CivilEng 2022, 3, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-H.; Loftness, V.; Aziz, A. Post-occupancy evaluation of 20 office buildings as basis for future IEQ standards and guidelines. Energy Build. 2012, 46, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, D.H.; Levermore, G.J. The effects of future climate change on heating and cooling demands in office buildings in the UK. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2010, 31, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cody, B.; Loeschnig, W.; Eberl, A. Operating energy demand of various residential building typologies in different European climates. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2018, 7, 226–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, J.A.; Gorrissen, W.J.; Hathaway, J.H.; Skorski, D.C.; Scott, M.J.; Pulsipher, T.C.; Huang, M.; Liu, Y.; Rice, J.S. Impacts of climate change on energy consumption and peak demand in buildings: A detailed regional approach. Energy 2015, 79, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOE, U. S. (2020). DOE Reference Commercial Buildings Report; Prototype Building Model Package. U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved April from ttps://www.energycodes.gov/development/commercial/prototype_models.

- Duan, Z.; de Wilde, P.; Attia, S.; Zuo, J. Challenges in predicting the impact of climate change on thermal building performance through simulation: A systematic review. Appl. Energy 2025, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnagar, E.; Gendebien, S.; Georges, E.; Berardi, U.; Doutreloup, S.; Lemort, V. Framework to assess climate change impact on heating and cooling energy demands in building stock: A case study of Belgium in 2050 and 2100. Energy Build. 2023, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissler, S.; Österreicher, D.; Macharm, E. Transition towards Energy Efficiency: Developing the Nigerian Building Energy Efficiency Code. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Gurney, K.R. The variation of climate change impact on building energy consumption to building type and spatiotemporal scale. Energy 2016, 111, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, M. , & Van Vuuren, D. P. ( 37(2), 507–521.

- Jenkins, D.P.; Patidar, S.; Simpson, S.A. Quantifying Change in Buildings in a Future Climate and Their Effect on Energy Systems. Buildings 2015, 5, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubb, I., Canadell, P., & Dix, M. (2013). Representative concentration pathways (RCPs). Australian Government, Department of the Environment.

- Karmann, C.; Schiavon, S.; Bauman, F. Thermal comfort in buildings using radiant vs. all-air systems: A critical literature review. Build. Environ. 2017, 111, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khourchid, A.M.; Ajjur, S.B.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Building Cooling Requirements under Climate Change Scenarios: Impact, Mitigation Strategies, and Future Directions. Buildings 2022, 12, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneifel, J., Kneifel, J., & O'Rear, E. (2015). Benefits and costs of energy standard adoption for new residential buildings: National summary. US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology.

- Leslie, P.; Pearce, J.M.; Harrap, R.; Daniel, S. The application of smartphone technology to economic and environmental analysis of building energy conservation strategies. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2012, 31, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Cabeza, V. P., Galán-Marín, C., & Rivera-Gómezs, C. (2020). Thermodynamic performance enhancement of courtyards using a shading device. Proceedings.

- Ma, L., & Zeng, Z. (2022). A Survey of the Influence of Air Distribution on Indoor Environment and Building Energy Efficiency. Journal of Physics: Conference Series.

- Meinshausen, M.; Smith, S.J.; Calvin, K.; Daniel, J.S.; Kainuma, M.L.; Lamarque, J.F.; Matsumoto, K.; Montzka, S.A.; Raper, S.C.; Riahi, K.; et al. The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions from 1765 to 2300. Clim. Chang. 2011, 109, 213–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meteotest. (2023). Meteonorm Software. Retrieved September from https://meteonorm.com/en/.

- Niknia, S.; Rashed-Ali, H. Analyzing energy consumption due to occupant interaction with manual and automatic window blinds in multiple climates. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimlyat, P., Dassah, E., & Allu, E. (2014). Computer Simulations In Buildings: Implications For Building Energy Performance.

- Ortiz, L.; E González, J.; Lin, W. Climate change impacts on peak building cooling energy demand in a coastal megacity. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 094008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- sterreicher, D.; Seerig, A. Buildings in Hot Climate Zones—Quantification of Energy and CO2 Reduction Potential for Different Architecture and Building Services Measures. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PortfolioManager. (2024). U.S. Energy Use Intensity by Property Type. US Energy Use Intensity by Property Type. https://portfoliomanager.energystar.gov/pdf/reference/US%20National%20Median%20Table.pdf.

- Riahi, K.; Rao, S.; Krey, V..; Cho, C.; Chirkov, V.; Fischer, G.; Kindermann, G.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rafaj, P. RCP 8.5—A scenario of comparatively high greenhouse gas emissions. Climatic change. 2011, 109, 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- San José, R., Pérez, J. L., & Gonzalez-Barras, R. M. (2020). High spatial resolution climate scenarios to analyze Madrid building energy demand.

- José, R.S.; Pérez, J.L.; Pérez, L.; Barras, R.M.G. Climate Change Impacts on Energy Demand of Madrid Buildings. J. Clean Energy Technol. 2018, 6, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Ding, L.; Fiorito, F.; Oldfield, P.; Osmond, P.; Paolini, R.; Prasad, D.; Synnefa, A. Passive and active cooling for the outdoor built environment – Analysis and assessment of the cooling potential of mitigation technologies using performance data from 220 large scale projects. Sol. Energy 2017, 154, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Vasilakopoulou, K. Present and future energy consumption of buildings: Challenges and opportunities towards decarbonisation. e-Prime-Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy 2021, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.; Gervásio, H.; da Silva, L.S.; Lopes, A.G. Influence of climate change on the energy efficiency of light-weight steel residential buildings. Civ. Eng. Environ. Syst. 2011, 28, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinoni, J.; Vogt, J.V.; Barbosa, P.; Dosio, A.; McCormick, N.; Bigano, A.; Füssel, H. Changes of heating and cooling degree-days in Europe from 1981 to 2100. Int. J. Clim. 2017, 38, E191–E208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udendhran, R., Sasikala, R., Nishanthi, R., & Vasanthi, J. (2023). Smart Energy Consumption Control in Commercial Buildings Using Machine Learning and IOT. E3S Web of Conferences.

- Wang, H.; Chen, Q. Impact of climate change heating and cooling energy use in buildings in the United States. Energy Build. 2014, 82, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Brown, H. Prediction of the impacts of climate change on energy consumption for a medium-size office building with two climate models. Energy Build. 2017, 157, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoxu, L., Kailiang, H., Guohui, F., Danyang, J., Dan, L., & Jiawei, L. (2022). Analysis on night ventilation effect of buildings with different energy consumption levels in Shenyang. E3S Web of Conferences.

- Yau, Y.; Hasbi, S. A review of climate change impacts on commercial buildings and their technical services in the tropics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 18, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).