1. Introduction

Hearing related disease is a significant cause of disability and morbidity across the globe, as recognized in the World Health Organization (WHO)’s World Report on Hearing [

1]. The prevalence of hearing loss continues to rise, and 2.5 billion people are expected to be living with some degree of hearing loss by 2050 [

1]. However, half of all hearing loss is preventable through various public health measures, and among children, 60% of hearing loss is due to preventable causes [

2]. Infection, specifically, is a preventable cause of hearing loss that varies widely in incidence depending on region. The WHO estimates that 98.7 million people have hearing loss that was caused by suppurative otitis media [

1]. Unfortunately, the burden of acute otitis media (AOM) and chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) disproportionally affects Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) compared to High Income countries (HIC) where the sequelae remain rare [

3]. This places the greatest burden on the health systems least equipped to address these challenges.

Malawi, a country in southeastern Africa, is one such low-income nation that struggles with preventable hearing loss. There is limited existing data regarding the extent of hearing loss and chronic ear disease in Malawi. A study conducted by Mulwafu found that 11.5% of children aged 4 to 6 had bilateral hearing loss and in children with hearing loss, only 30% were enrolled in school [

4]. Hunt et al. in 2017 similarly found that 12.5% of children had bilateral hearing loss, and that almost ¼ of children aged 4 to 6 had hearing loss in at least 1 ear [

5]. A recent study by Mtamo et al. found that 68% of patients presenting to an audiology clinic had a pathology consistent with conductive hearing loss [

6]. While these studies were limited by sample size and a full description of the hearing loss, they point to a significant degree of hearing pathology in a country with limited ability to provide extensive hearing health services.

In resource limited settings, prevention and early detection can be critical to prevent severe disease. Understanding what a population knows and thinks about hearing health can be critical to identifying fillable knowledge gaps. Indeed, a study conducted among Malawian school teachers regarding hearing health awareness showed a significant improvement in basic knowledge about ears and hearing health following an educational intervention [

7]. However, there is no information assessing the broader population’s understanding of their hearing health. A better understanding of state of hearing health awareness and the use of traditional therapies among the Malawian population can provide for development of meaningful education campaigns that prevent a significant burden of preventable disease, morbidity, and mortality. Additionally, this model may have implications for improving hearing health care in resource-limited settings worldwide.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design: A retrospective review of data collected from patients treated during a hearing health outreach conducted in May 2024 as a collaboration between the African Bible College (ABC) audiology program, Entheos (an American audiology cooperative), Hearing The Call (non-profit), Kismet: Empowering Health Access (non-profit), ENT clinicians from the Kasungu District Hospital, and an outreach team from the University of South Florida (USF) was conducted. The outreach clinic took place over three days at three separate sites in the Kasungu district of Malawi. In the months leading up to the outreach, the ABC team advertised the dates and locations to the local population in coordination with the local Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) clinicians at the Kasungu District Hospital. The clinic was set up in multiple stations that offered a variety of services including otoscopic examinations, wax removal, otoacoustic emission screening, tympanometry, field hearing testing, custom hearing aid molding, hearing aid fitting, and ENT examinations as needed based on clinical presentation of the patient.

As part of the ABC team’s effort to improve the quality of outreach, patients with evidence of infection (purulence, drainage, wet perforations, evidence of fungal infection, or any other evidence of acute or chronic otitis media or otitis externa) were invited to provide additional details with regard to their hearing health. The patient or responsible guardian were asked a series of five open ended questions related to hearing health and ear infections with the goal of assessing the patient’s understanding of what causes ear infections, what treatments are available, and if the available treatments are effective. Patients were additionally asked a series of ten ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions adapted from a WHO survey designed to assess hearing health knowledge [

7,

8]. Note that all questions were asked in the patient’s native language, Chichewe, and all recorded answers were back translated to English by author E.C., a native speaker of both languages. This data was collected for quality improvement for clinical outreach and used by the clinic to improve care. This data set was subsequently reviewed for this publication.

While the study was conducted as a quality improvement project, USF Institutional Review Board (IRB) exemption was obtained for this data review under the IRB number STUDY007654: ABC HCTC Hearing Health Education. Additionally, the USF IRB waived the requirement for consent for this data review.

Quantitative Analysis

Patient charts were reviewed for demographic information including gender, age, education level, occupation, mode of transportation and travel time to the clinic. Additional information was collected regarding presence of hearing loss (unilateral vs bilateral), ear pain, ringing in ears, risk factors for hearing loss, status of hearing device wear, and presence of drainage or perforation during otoscopic inspection at the outreach clinic. Pure tone audiometry results were also reviewed.

Basic descriptive statistics were used to characterize the data and define means. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.2.3 for Mac, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA,

www.graphpad.com (April 21st, 2024).

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis of the open-ended responses was performed by reviewing the patients answers individually and discussing key themes that emerged, as a group. The three major themes used were “Knowledge of Causes and Treatments for Ear Infections”, “Knowledge of Prevention and Impact on Livelihood”, and “Treatment Action”. Answers were then coded manually for inclusion in these three thematic area and subthemes were identified within each area. Patient’s responses were further coded and tabulated as to their certainty regarding their understanding of a particular theme and whether they took action for their infection.

Traditional Healing Methods

Traditional healing methods are common in these communities and so specific attention was paid to assessing which methods were utilized by individuals. The different preparations used by individuals were reviewed and local traditional herbalists were then queried to better understand the home remedies. Information regarding the herb, the part used, means of usage and whether it was thought to be useful by the herbalist was recorded.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

A total of 52 individuals were identified as completing the additional questions regarding hearing health. The mean age of individuals was 30.2 (SD=18.7). Of those participants, 27 (51.9%) identified as male, 24 (46.2%) identified as female, and 1 (1.9%) individual did not record a response. The majority of participants completed their education at the primary level (51.9%) and reported working as a farmer (38.4%). To attend the clinic, an almost equal number of individuals reported taking the bus (26.9%) or riding a bike (25%). It was found that the most common mode of transportation was walking, with 18 individuals (34.6%), and the least common mode of transportation was travelling via car/motorcycle, with only 7 individuals (13.5%). Most individuals had to travel between 1 to 2 hours (40.4%) or 1 to 30 minutes (38.5%) to attend the clinic (

Table 1).

Information regarding several otologic variables was ascertained from participants. Over half of participants reported ear pain (55.8%) and hearing loss (61.5%) bilaterally. Unilateral ear pain, in either the right or left ear, was only reported by 5 individuals (9.6%) respectively, and hearing loss was only reported by 6 individuals (11.5%) and 4 individuals (7.7%) respectively. Despite about 80% of participants reporting either unilateral or bilateral hearing loss, only 5 individuals had previously (5.8%) or currently (3.8%) worn a hearing device. There are several risk factors for hearing loss, including noise exposures, family history and disease incidence. Within this cohort, malaria was the risk factor most reported by individuals (71.2%), followed by family history (30.8%), noise exposure (17.3%), and HIV (11.5%). As part of the outreach, participants underwent otoscopic inspection. Of the 52 participants, ear drainage was reported in 44.2% unilaterally and 25% bilaterally. Whereas perforation was reported in 26.9% unilaterally and 46.1% bilaterally (

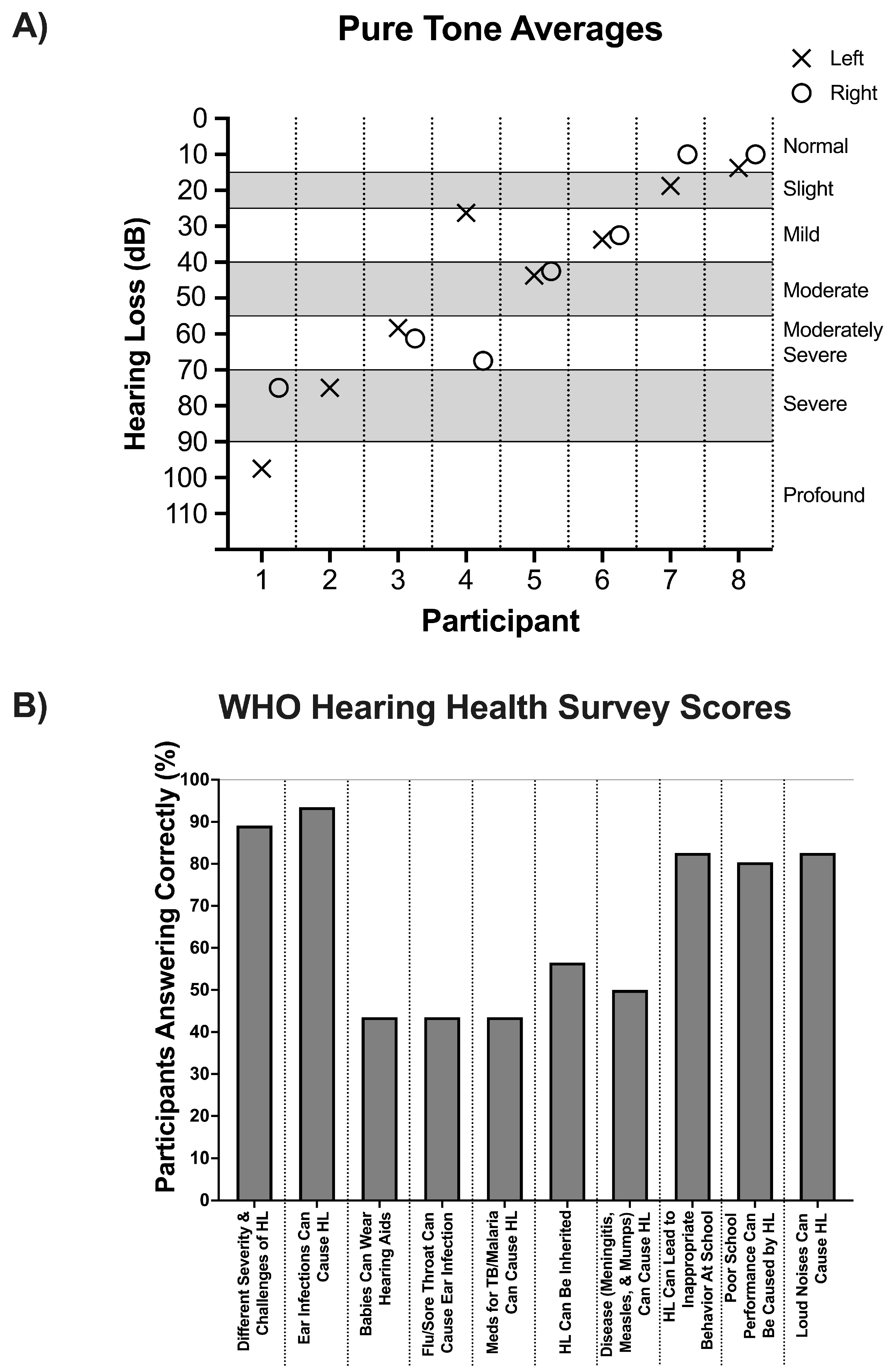

Table 1). For the eight individuals who also underwent pure tone audiometry, five out of eight had moderate hearing loss or worse and two had severe to profound hearing loss (

Figure 1a).

3.2. Hearing Health Knowledge Analysis: Quantitative Assessment

A total of 46 individuals completed a hearing health knowledge survey containing 10 “yes” or “no” questions adopted from a WHO survey as a part of their participation in the outreach clinic. Notably, several questions were answered incorrectly more frequently than others (

Figure 1b). While there was a general high level of knowledge of certain topics related to hearing health, including that it can be of different severities and challenges (89.1%) and that hearing loss can lead to issues at school, only 43.5% of individuals correctly answered the questions evaluating knowledge regarding a baby’s ability to wear a hearing aid, whether the flu or a sore throat could cause ear infections, and whether TB and/or malaria medications could cause hearing loss. Moreover, only 50% of individuals correctly acknowledged that diseases such as meningitis, measles, and mumps could cause hearing loss, and only 56.5% of individuals correctly acknowledged that hearing loss could be inherited.

3.3. Hearing Health Knowledge Analysis: Qualitative Assessment

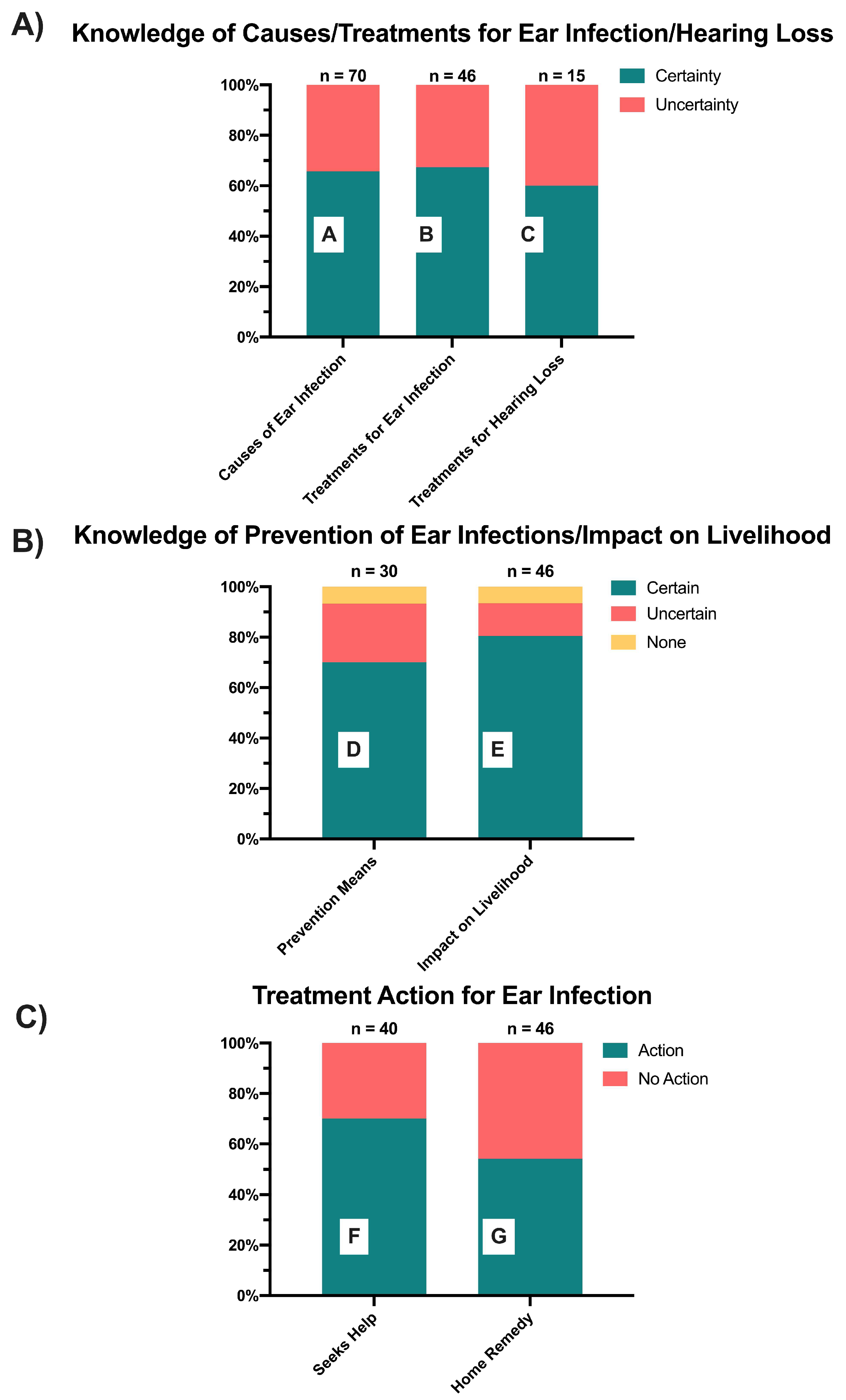

Participants completed a quality improvement interview containing five open-ended questions related to hearing health and ear infection to assess their understanding of ear infection root causes, treatment availability, and effectiveness. Thematic analysis on participant responses revealed three key themes: “Knowledge of Causes and Treatments for Ear Infections”, “Knowledge of Prevention and Impact on Livelihood”, and “Treatment Action”. These overarching themes were broken down into several subthemes and responses were coded according to the legends in

Figure 2. Many participants provided responses that exhibited overlapping themes. However, each mention of a subtheme was counted as a separate instance, with the sample size of subtheme instances denoted over the corresponding subtheme bar graph.

Within the theme of “Knowledge of Causes and Treatments for Ear Infections”, three subthemes emerged: “Causes of Ear Infections”, “Treatments for Ear Infections”, and “Treatments for Hearing Loss” (

Figure 2a). Responses were coded according to whether they indicated participant certainty or uncertainty regarding knowledge pertaining to each subtheme. For the subtheme “Causes of Ear Infections”, a coding of certainty illustrates the participant was certain about their cause or other causes of infection, whereas uncertain illustrates uncertainty of their cause or other causes of infection. For the subthemes “Treatment of Ear Infection” and “Treatment of Hearing Loss”, a coding of certainty illustrates the participant was certain about possible treatments regardless of whether they deemed it effective or not, whereas uncertain illustrates uncertainty of any forms of treatment. Across all three subthemes, over 60% of responses for each subtheme indicated certainty regarding knowledge of causes of ear infections, and treatment of ear infections and hearing loss. Examples of these responses are found in

Table 2 in rows A, B, and C of individual responses pertaining to causes and treatments.

Within the “Knowledge of Prevention and Impact” theme, the subtheme of “Prevention Means”, and “Impact on Livelihood” emerged (

Figure 2b). Responses were coded according to whether the individual indicated that they believed a means of prevention or potential impact existed, and whether they indicated certainty or uncertainty regarding knowledge pertaining to each subtheme. Only 6.7% and 6.5% of interview responses indicated that individuals believed that there was no possible means of prevention and no impact on livelihood due to ear infection, respectively. Most responses indicated a certainty regarding the knowledge of prevention means (70%) and ear infection impact on livelihood (80.5%). Rows D and E in

Table 2 illustrate examples of patient responses on the effects on livelihood or prevention means.

“Treatment Action” was the third major theme identified and during further analysis the subthemes of “Seeking Help” and “Home Remedies” emerged (

Figure 2c). Responses were coded for each subtheme according to if they indicated the individual took some sort of action, whether it was seeking help or home remedies, or they did not take action to address infection. Amongst the responses that aligned with the subtheme of “Seeking Help”, 70% indicated that individuals sought some form of outside assistance for their ear infections. Exemplified by the quotes in row F of

Table 3, these outside sources included traditional healers and clinicians, with only 30% of responses indicating they sought no outside help. Amongst the responses that aligned with the subtheme of “Home Remedies”, an almost equal instance of responses occurred indicating either action or no action, with 54.3% of responses within that subtheme indicating action with home remedies and 45.7% indicating no action with home remedies. As outlined in row G of

Table 2, these home remedies included using herbs, cloth, matchsticks, chicken feather, urine, and soot.

3.4. Traditional Remedies

Participants identified 11 herbs utilized as home remedies to treat CSOM, which included madzi a anyezi (onion water), mathulisa, cham’mwamba (moringa), nthethanyerere, masamba a nandolo (pea leaves), madzi a mtengo wa nthochi (banana stem water), aloe vera, masamba a tomato (tomato leaves), chamba (marijuana), and likhodza (

Table 3). In addition to these herbs, some also reported using salt, soot (mwaye or mwawi), urine, and methylated spirit. The herbs were used topically, rather than via systemic/oral ingestion. Of the herbs used by participants, only onion water and aloe vera were confirmed via interview with local herbalists to be recommended as effective for treating CSOM, due to their antimicrobial and antifungal properties. The remainder of the remedies were considered ototoxic by the herbalist.

Interviews conducted with two local herbalists revealed additional recommended herbal treatments for CSOM, including onion water, aloe vera, neem oil, and water from mustard leaves. Of these recommended treatments, only 2 were used by individuals attending the outreach clinic (onion water and aloe vera), whereas 9 of the herbs referenced by clinic participants were not recommended by the local herbalists. Route of use varied between the herbalists, with some recommending only topical use while others recommended topical use and ingestion. All herbalists recommended consultation with a traditional healer for these remedies to ensure correct dosage, proper preparation, and selection of the herb. All noted that the lack of consultation was likely to result in worsened disease and affected hearing.

4. Discussion

This is the first review that has sought to directly assess the level of hearing awareness among patients specifically with chronic ear disease who received care on a hearing outreach. The extent of ear disease noted among this cohort is certainly remarkable with 61.5% reporting bilateral hearing loss but with only 3.8% currently using a hearing device. The otoscopic results indicate the extent of the clinical burden of ear disease with almost half of individuals noted to have bilateral perforations (46%) and similarly almost half (44%) with at least a unilateral draining ear. While this is a subset of individuals referred for further evaluation amongst a larger hearing screening effort and thus some enrichment for pathology is expected, this is still a significant burden of undertreated disease. This is in keeping with findings of individuals treated at the ABC clinic in Lilongwe, Malawi where 83% of patients presented with outer or middle ear pathology and then 68% of patients presented with pathologies that are often associated with conductive hearing loss consistent with middle and outer ear pathologies [

6]. The limitations of access to hearing health care was borne out in the 40% of individuals who traveled 1-2 hours in order to seek care at the outreach. Additionally, nearly two thirds of patients traveled via walking or bicycle, further indicating the barriers to accessing hearing health care.

With regard to the hearing health awareness of the individuals interviewed, most individuals (93.5%) felt that hearing loss had an effect on livelihood and that there was prevention (93.3%). However, results from the hearing health knowledge survey illustrated that knowledge gaps exist, specifically regarding a baby’s ability to wear hearing aids, the ability for flu and/or sore throat to cause ear infection, and the ability for TB and/or malaria medications to cause hearing loss (56.5%). These findings are consistent with a previous study conducted in Malawi, where 76%, 44%, and 41% of individuals also incorrectly answered those hearing health knowledge questions, respectively.

7 Especially among a population with high rates of a history of malaria (a remarkable 71% in this cohort), limitations in knowledge surrounding the effect on hearing loss can be devastating. Additionally, the lack of knowledge of the connection between other infectious presentations and ear infections is especially worrisome as lack of attention to these illnesses especially in children might start an individual on the tract of lifelong otologic disease [

9].

A study conducted in rural south India similarly found that 50% of the population showed deficits in knowledge with respect to otitis media risk factors and a Nigerian study reported that the knowledge of risk factors for otitis media varied by socioeconomic status, thus highlighting the need to tie healthcare education with economic development programs [

10,

11]. Additionally, a study conducted in the Netherlands found an increased risk of CSOM (OR 14.1) among children of parents of low education level [

12]. These findings coupled with this study’s findings suggests that targeted educational interventions may serve as an effective lost-cost opportunity to improve individual knowledge regarding hearing, which in turn could ultimately improve early identification, intervention, and outcomes.

Additional studies in several countries with high levels of AOM and CSOM have begun to identify other possible hearing health knowledge trends, but more data is needed to accurately assess current understanding of hearing health and existing treatment practices in the developing world. For example, a study in rural South Africa found that only 14% of participants were aware the audiology profession existed, and only 5% had previously seen an audiologist [

13]. While the individuals seen on our outreach had faced limitations in access to care, 70% of patients had sought care for their infection. This is higher than expected as typically a leaking ear is considered so normal that it is often dismissed, and no care pursued [

10,

14]. Srikanth et al. (2009) found that earaches in rural south India were treated with home remedies by 67.2% of caregivers and were no treatment was sought by 26.4% of caregivers [

10]. Access to care for ear related disease is very limited in the Malawian setting. As of 2017, there were only two Ear Nose and Throat (ENT) surgeons and three audiologists to serve a population of approximately 17.2 million [

15]. The number of trained audiologists has increased since 2021 when the African Bible College graduated the first ten audiologists trained in Malawi with a Bachelor of Science in Audiology. However, there remain limitations in job opportunities and thus retainment of these trainees.

To the authors’ knowledge, the current study is the first to specifically collect data regarding the traditional remedies for otitis media utilized by patients and evaluate their use with local traditional healers. The additional information gathered from the interviews with herbalists adds insight into the recommendations patients are receiving, as they seek out medical advice from different settings. Notably, many of the treatments being used by patients were not recommended by the traditional healers, whose recommendations were based on the belief that the herbs chosen for CSOM had specific natural antimicrobial and/or antifungal properties. While there is no data to support the antimicrobial properties of these specific agents, there has been an interest in non-antibiotic, antimicrobial options for treatment of CSOM. For example, a study conducted in Cape Town, South Africa in 2012 found the use of boric acid to be an equally effective alternative to quinolone drops, which is current best practice, but much more expensive than the boric acid alternative [

16]. Additionally, they found that Quadriderm cream was effective in 85% of patients failing first-line therapy and that none of the treatments utilized were noted to be otototoxic [

16]. Van Straten et al. conducted a subsequent study in 2020 that examined the utility of antiseptic agents compared to standard quinolone drops against common organisms of CSOM in vitro. They found that boric acid powder and 5% povidone iodine showed promising results, with 3.25% aluminum acetate producing excellent activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

17]. Acetic acid is another commonly used antimicrobial in CSOM although the data available is mixed on utility, which is likely due to wide variance in disease presentation and adherence [

17,

18,

19].

Given real resource limitations, an improved understanding of the various antimicrobial properties of readily available natural agents has the opportunity to improve access to care for patients. Additionally, improved education surrounding the safety profile of various home remedies is critical to prevent accidental ototoxic events.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. There is a selection bias as patients had self-presented to a hearing health outreach and thus were likely to have current or prior experience with ear infections and hearing health. As such, these patients may not be representative of the broader population of Malawi. Furthermore, the ability to obtain the additional quality improvement data occurred on a rolling basis within the larger outreach setting and thus not all patients with otitis were interviewed. However, given the random nature of inclusion based on availability, should limit this bias. Finally, the quality improvement questions were initially conceptualized in English but majority of patients primarily spoke Chichewa and there was occasional need for rephrasing or prompting which may have introduced some variance in response.

5. Conclusions

Assessing a patient’s understanding of their disease process is critical to treatment. An understanding of a community’s beliefs and practices allows for targeted interventions to be developed and implemented to improve early detection and treatment of disease. Here we identified specific gaps in knowledge about the cause, impact, and treatment of otitis media in a patient population with a heavy burden of this disease. Notably, many of these patients had attempted home remedies, which both our clinical staff and the herbalist interviewed for this manuscript felt were of limited utility and of potential harm to patients. However, given the benefit of effective, non-antibiotic treatment for otitis media, additional evaluation of these options in the context of evaluating therapies like boric acid and acetic acid are valuable.

Best care can be achieved by aligning patient needs and understanding with the best available evidence, but this relies on their underlying understanding of their disease and the availability of treatment, as well as a therapeutic alliance with their healthcare provider. While this study was conducted in a rural setting in Malawi, we believe this is a generalizable statement of potential benefit in a wide range of contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Audiometry Results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Enittah Chikuse, Derek Jacobs, Angella Banda, Julia Toman, Jenna Vallario and J. Zachary Porterfield; Data curation, Enittah Chikuse, Derek Jacobs, Angella Banda, Julia Toman, Jenna Vallario, Danielle Curtis and J. Zachary Porterfield; Formal analysis, Enittah Chikuse, Derek Jacobs, Angella Banda, Julia Toman, Jenna Vallario, Danielle Curtis and J. Zachary Porterfield; Investigation, Enittah Chikuse, Derek Jacobs, Angella Banda, Julia Toman, Jenna Vallario and J. Zachary Porterfield; Methodology, Enittah Chikuse, Derek Jacobs, Angella Banda, Julia Toman, Jenna Vallario and J. Zachary Porterfield; Project administration, Julia Toman, Jenna Vallario and J. Zachary Porterfield; Resources, Julia Toman, Jenna Vallario and J. Zachary Porterfield; Supervision, Julia Toman, Jenna Vallario and J. Zachary Porterfield; Visualization, Danielle Curtis and J. Zachary Porterfield; Writing – original draft, Enittah Chikuse, Derek Jacobs, Angella Banda, Julia Toman, Jenna Vallario, Danielle Curtis and J. Zachary Porterfield; Writing – review & editing, Enittah Chikuse, Derek Jacobs, Angella Banda, Julia Toman, Jenna Vallario, Danielle Curtis and J. Zachary Porterfield.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was deemed exempt from Institutional Review Board review at the University of South Florida (STUDY007654, 09/20/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the data collection being QA/QI by nature. The Institution Review Board determined that due to the number of records to review and the retrospective nature of this review, it would be unreasonable to prospectively obtain consent for each record, thus a waiver of informed consent was approved.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to subject privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank the African Bible College Hearing Clinic, Entheos, Hearing the Call, and Kismet: Empowering Health Access for their invaluable collaboration on this project and for providing the support and clinical expertise for the outreach program. We would also like to extend our sincere thanks to Benjamin Chisale with Nthambi Natural Health and Alex Banda of Tree of Life Herbal Clinic for their expertise in traditional herbal treatments and their contributions to evaluating the therapies that were used in these patients. We discussed authorship with them, but they have elected for an acknowledgment. Irrespective, this would not be possible without their contributions.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OM |

Otitis Media |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| AOM |

Acute Otitis Media |

| LMICs |

Low and Middle Income Countries |

| HIC |

High Income Countries |

| ABC |

African Bible College |

| ENT |

Ears, Nose, and Throat |

| HIV |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| TB |

Tuberculosis |

| CSOM |

Chronic Supprative Otitis Media |

References

- Chadha S, Kamenov K, Cieza A. The world report on hearing, 2021. Bull World Health Organ. Apr 1 2021;99(4):242-242A. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Deafness and hearing loss. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Monasta L, Ronfani L, Marchetti F, et al. Burden of disease caused by otitis media: systematic review and global estimates. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36226. [CrossRef]

- Mulwafu W, Tataryn M, Polack S, Viste A, Goplen FK, Kuper H. Children with hearing impairment in Malawi, a cohort study. Bull World Health Organ. Oct 1 2019;97(10):654-662. [CrossRef]

- Hunt L, Mulwafu W, Knott V, et al. Prevalence of paediatric chronic suppurative otitis media and hearing impairment in rural Malawi: A cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0188950. [CrossRef]

- Mtamo R, Vallario J, Kumar A, Casanova J, Toman J. Assessment of Outer and Middle Ear Pathologies in Lilongwe, Malawi. Audiol Res. May 30 2024;14(3):493-504. [CrossRef]

- Kapalamula G, Gordie K, Khomera M, Porterfield JZ, Toman J, Vallario J. Hearing Health Awareness and the Need for Educational Outreach Amongst Teachers in Malawi. Audiol Res. Apr 12 2023;13(2):271-284. [CrossRef]

- Di Berardino F, Forti S, Iacona E, Orlandi GP, Ambrosetti U, Cesarani A. Public awareness of ear and hearing management as measured using a specific questionnaire. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. Feb 2013;270(2):449-53. [CrossRef]

- Li MG, Hotez PJ, Vrabec JT, Donovan DT. Is chronic suppurative otitis media a neglected tropical disease? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. Mar 2015;9(3):e0003485. [CrossRef]

- Srikanth S, Isaac R, Rebekah G, Rupa V. Knowledge, attitudes and practices with respect to risk factors for otitis media in a rural South Indian community. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. Oct 2009;73(10):1394-8. [CrossRef]

- Adeyemo A. Knowledge of caregivers on the risk factors of otitis media. Indian Journal of Otology. 2012;18(4):184. [CrossRef]

- van der Veen EL, Schilder AG, van Heerbeek N, Verhoeff M, Zielhuis GA, Rovers MM. Predictors of chronic suppurative otitis media in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Oct 2006;132(10):1115-8. [CrossRef]

- Joubert K, Sebothoma B, Kgare KS. Public awareness of audiology, hearing and hearing health in the Limpopo Province, South Africa. S Afr J Commun Disord. Sep 28 2017;64(1):e1-e9. [CrossRef]

- Acuin J. Chronic suppurative otitis media: Burden of Illness and Management Options 2004. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42941 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Bright T, Mulwafu W, Thindwa R, Zuurmond M, Polack S. Reasons for low uptake of referrals to ear and hearing services for children in Malawi. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0188703. [CrossRef]

- Loock JW. A randomised controlled trial of active chronic otitis media comparing courses of eardrops versus one-off topical treatments suitable for primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare settings. Clin Otolaryngol. Aug 2012;37(4):261-70. [CrossRef]

- van Straten AF, Blokland R, Loock JW, Whitelaw A. Potential Ototopical Antiseptics for the Treatment of Active Chronic Otitis Media: An In Vitro Evaluation. Otol Neurotol. Sep 2020;41(8):e1060-e1065. [CrossRef]

- Gupta C, Agrawal A, Gargav ND. Role of Acetic Acid Irrigation in Medical Management of Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media: A Comparative Study. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Sep 2015;67(3):314-8. [CrossRef]

- Head K, Chong LY, Bhutta MF, et al. Antibiotics versus topical antiseptics for chronic suppurative otitis media. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Jan 6 2020;1(1):CD013056. C. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).