Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- compares CO₂, PM2.5 and SO₂ emissions in CACs countries,

- assesses the impact of economic structure on pollution levels,

- examines current strategies for reducing emissions and provides recommendations for adapting them to regional conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methodology

- the heterogeneity of data across countries in the region, which requires a comprehensive approach to their analysis; the dynamic nature of emissions, which must be assessed over time (1990–2024);

- the relationship between economic structure and pollution levels, which requires the use of econometric indicators;

- international commitments of CACs to reduce emissions, which makes a comparative analysis of strategies and policies necessary.

- Scientometric analysis of publications. It will be study of publications devoted to the problem of air pollution.

-

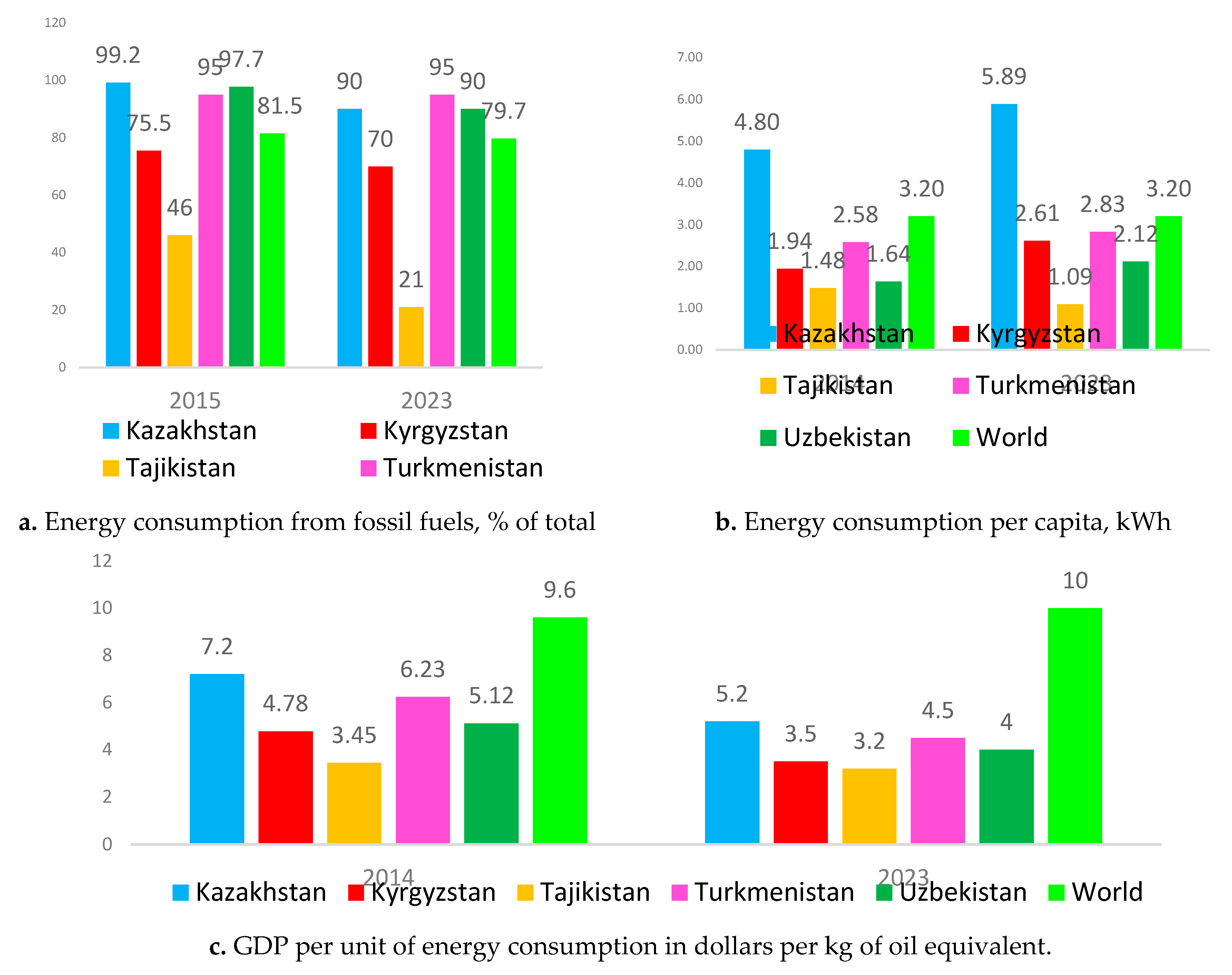

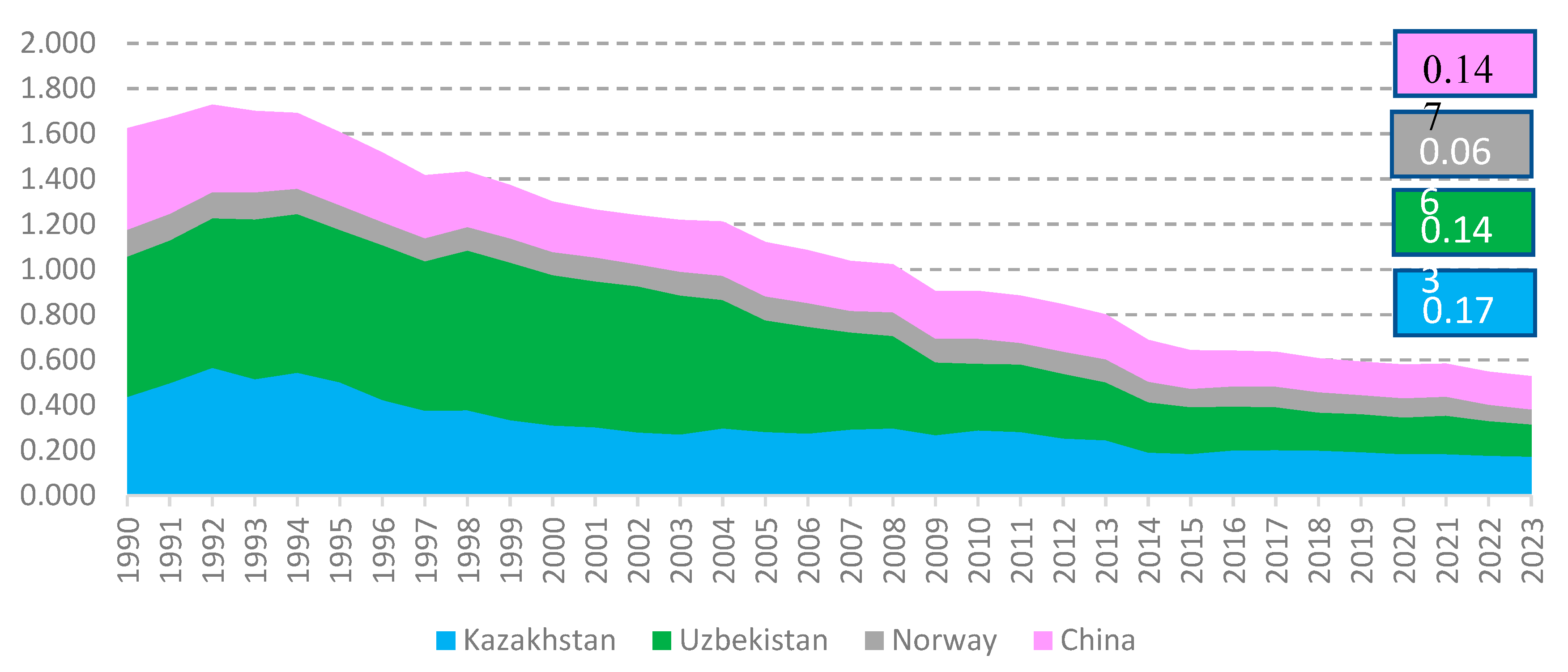

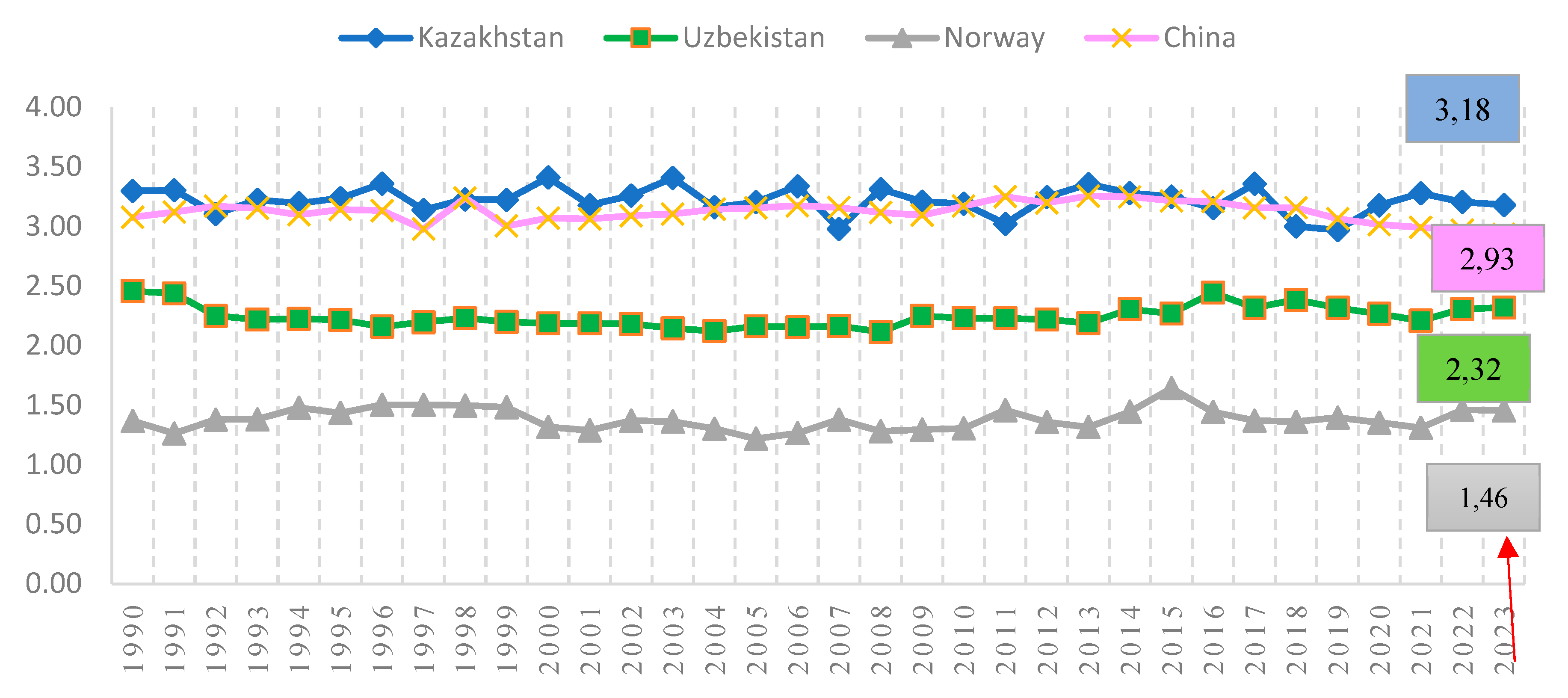

Identification of the Central Asia economy sectors features. It will be identify answer to the question: What economic sectors and factors have the most significant impact on air quality? To assess the relationship between the economic structure of countries and the level of pollution, methods of descriptive statistics, correlation analysis and regression modeling are used. Then it is necessary to estimate problems and challenges. To evaluate the energy efficiency of the CACs economies, indicators such as:

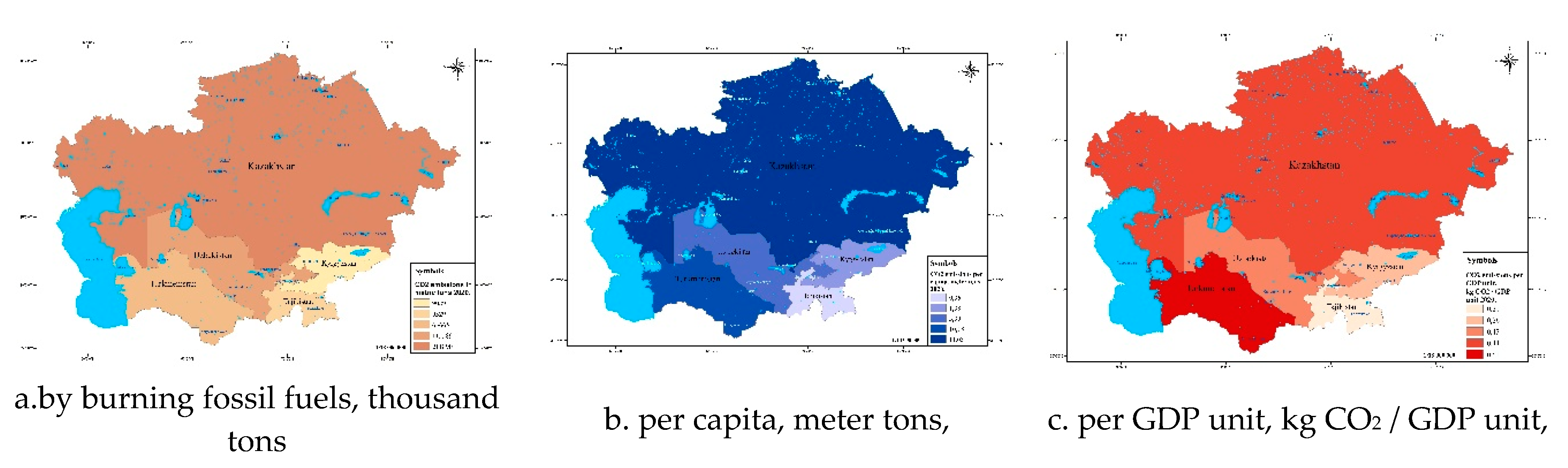

- a.

- Energy Intensity of CACs for the period 1990-2022;

- b.

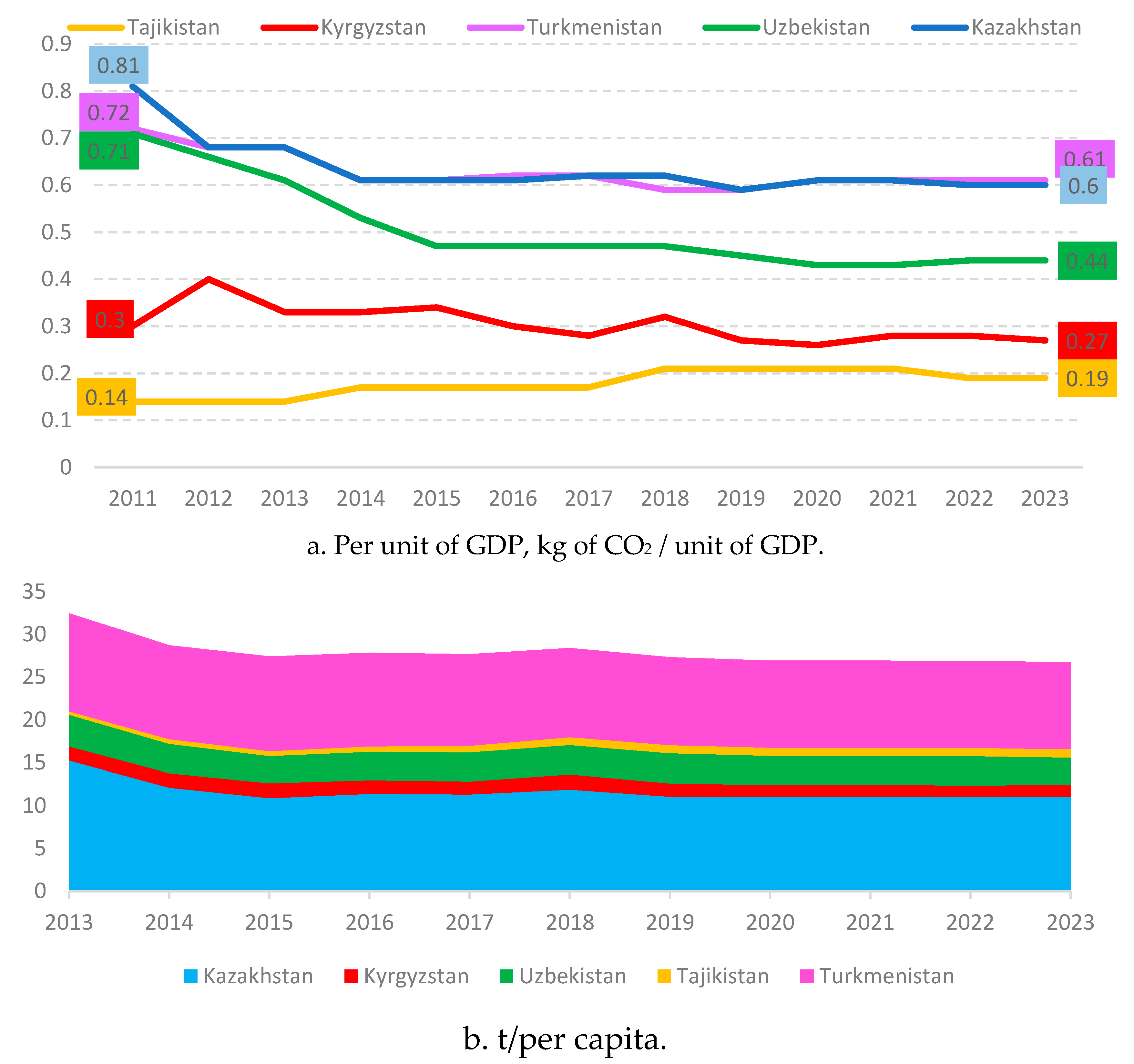

- Specific CO2 Emissions per capita;

- c.

- Specific CO2 Emissions per GDP;

- d.

- GDP per unit of energy consumption, quoted in dollars per kilogram of oil equivalent were used.

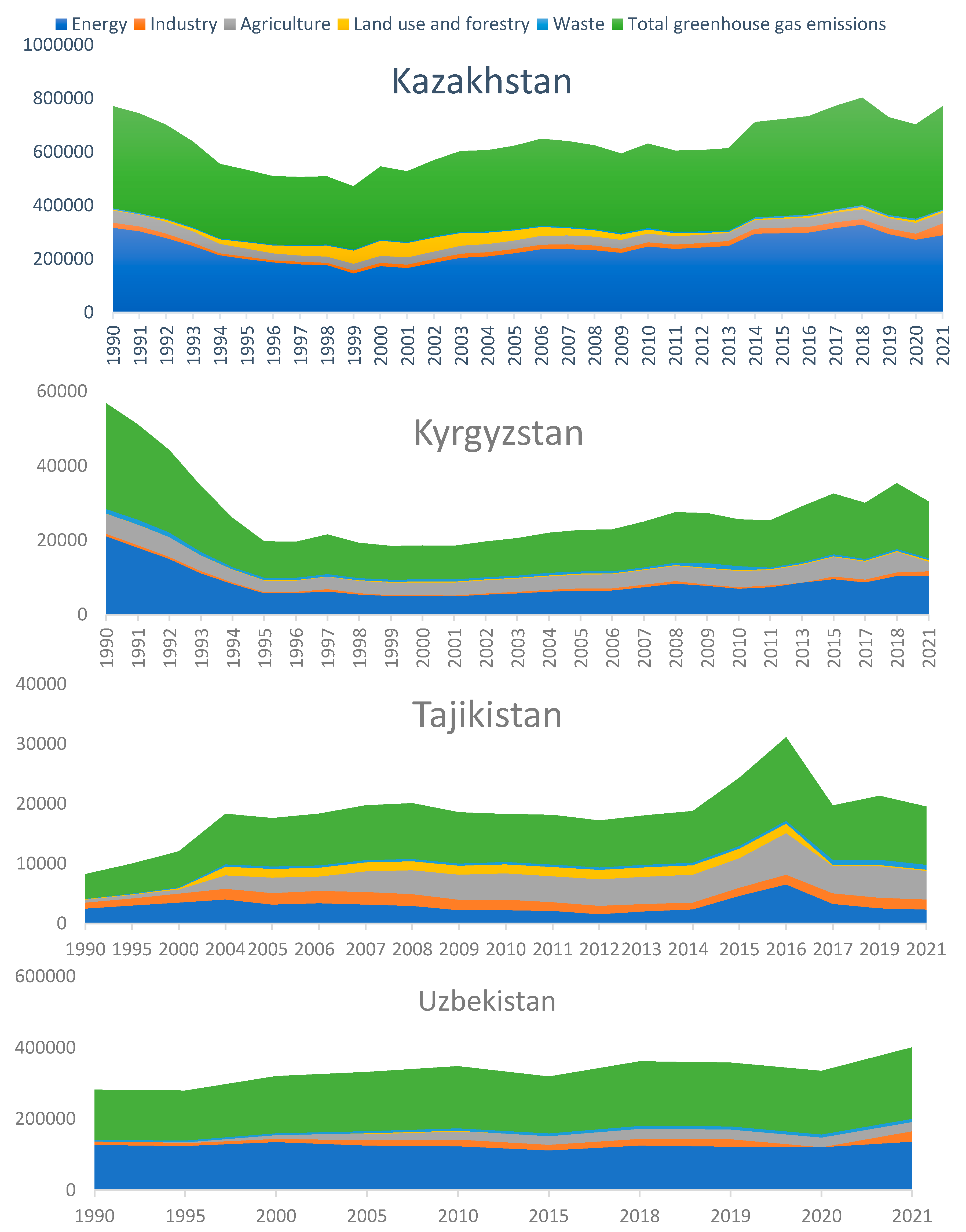

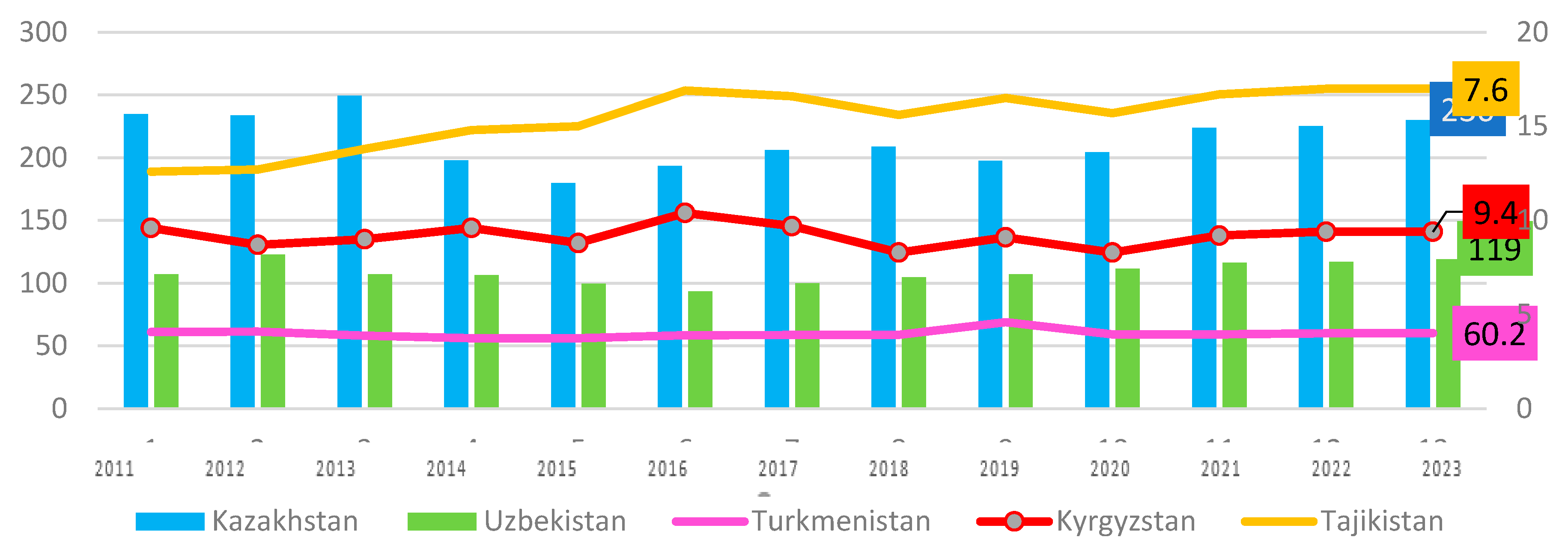

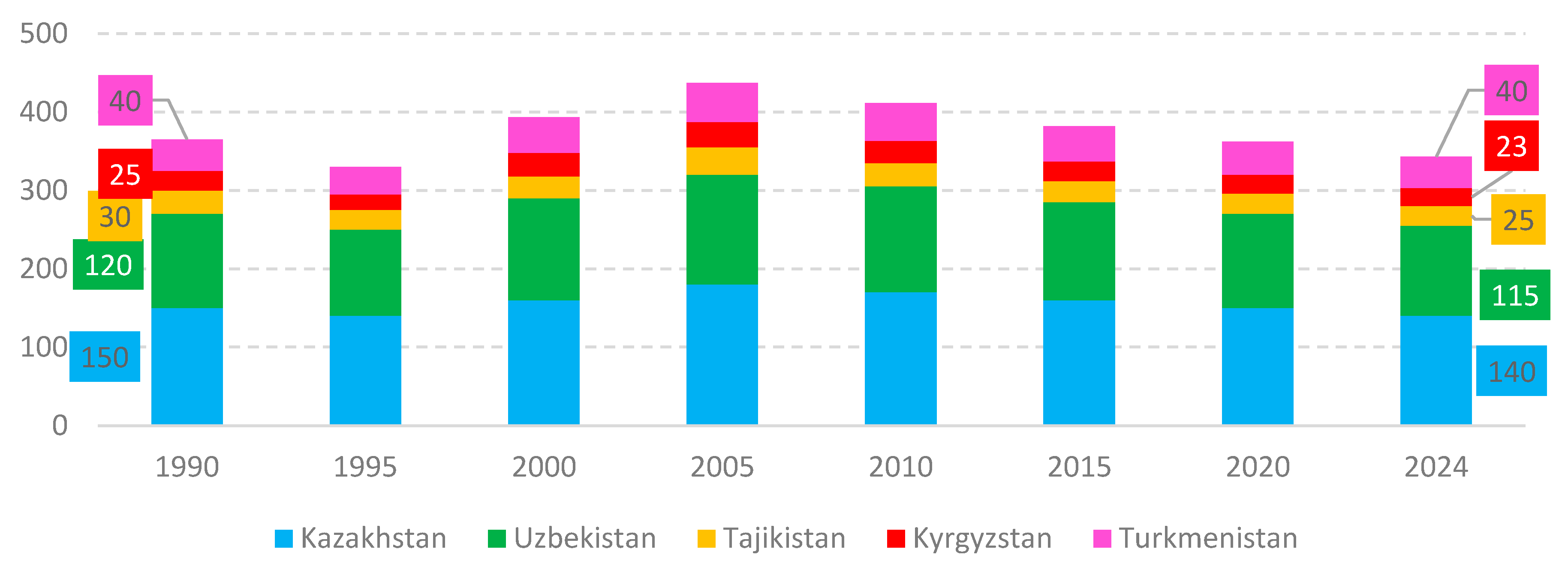

- Assessment of the ecological-climatic changes impact on air quality of the region. To study the pollution dynamics, a statistical analysis of time series (1990–2024) of CO₂, PM2.5 and SO₂ emissions is carried out. To achieve this goal indicators such as:

- Econometric modeling in the R program was used to identify relationships between CO2 emissions from fuel combustion and the factors that determine it, taking into account the specifics of country development:

- Strategies in Central Asia for implementing measures to reduce air pollution. Development of Recommendations for improvement. To provide a comparative analysis of emission reduction strategies, the environmental strategies of the CACs are examined in comparison with successful cases from other regions, including EU policies (ETS, European Green Deal), the Chinese air pollution strategy and the US experience in emission regulation.

2.2. Object of Study: CACs

2.3. Data Sources

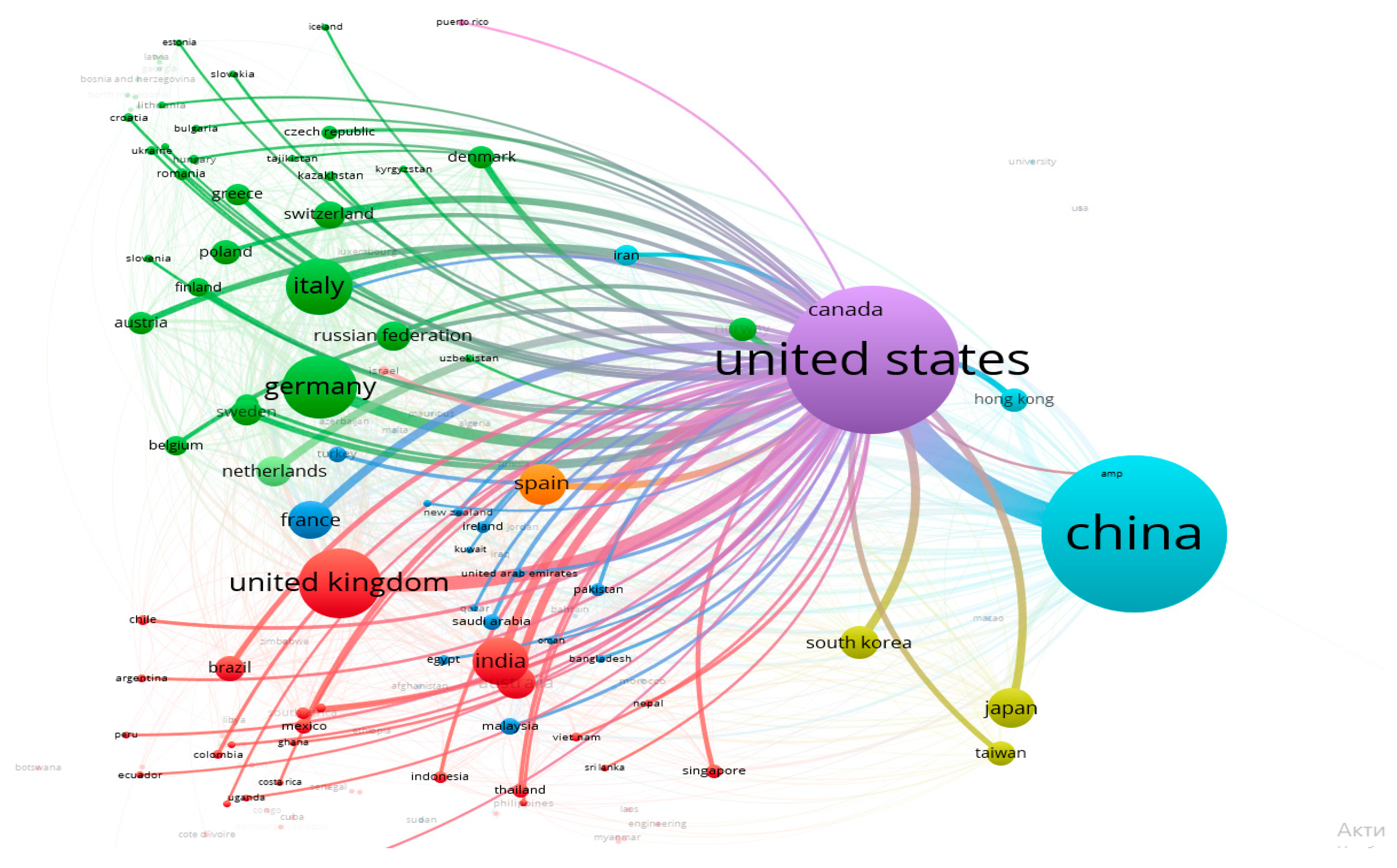

- Scientometric analysis of publications from Scopus and Web&Science databases was carried out using VoSViewer: by keywords, by country, by author [27].

- Identification of the Central Asia economy sectors features was carried out using environmental indicators, economic and energy indicators that make it possible to understand the relationship between economic activity and the level of atmospheric pollution [17,23,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Data regarding energy, fuel consumption and air emissions are gathered and systematized by national statistical offices, energy departments and environmental protection agencies. The work used information from National Statistics Bureau of the CACs, however, it should be noted that they are systematized mainly in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Thus, only in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) enshrined in laws available for review [29,35]. The following are used as key indicators:

- Assessment of the ecological-climatic changes impact on air quality of the region: It was used the National Communications and the Biennial Reports of the CACs to the UNFCCC [36,37,38,39,40]. The use of GHG inventory data in the analysis of atmospheric emissions in Central Asia is justified, because they are based on international standardized methodologies Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Guidelines 2006, mainly Tier 1, (Tier 2 Method: for waste, agriculture sectors) which allows for the comparison of analogous data, the assessment of emissions and their sources [41]. CH4 emissions mainly occur in agricultural production were obtained from GHG inventory data, supplemented by data from the Bureau of National Statistics and the TheGlobalEconomy.com [28,35,42]. The lack of data on other pollutants from industry, transport, and energy that are not related to GHGs, such as PM2,5, was filled in from relevant sources [29,30,31,32,33,34].

- The average CO2 emission factor, also known as the carbon factor is determined by calculating the ratio of CO2 emissions to primary energy consumption. It shows the amount of CO2 emitted per unit of energy, such as per kilowatt hour (kWh) or per tons of fuel burned. This indicator is vital for evaluating the effects of various energy sources on climate change. The data is presented at https://yearbook.enerdata.net/ [32].

- The ratio of specific CO₂ emissions from fuel combustion to GDP is expressed in kilograms of CO₂ per unit of GDP and serves as a significant measure for assessing the carbon intensity of an economy. The data is presented at UNECE, Data Portal https://w3.unece.org/SDG/ru/Indicator?id=28 [38].

- Strategies in Central Asia for implementing measures to reduce air pollution. Development of Recommendations for improvement.

3. Results

3.1. Scientometric Analysis of Publications

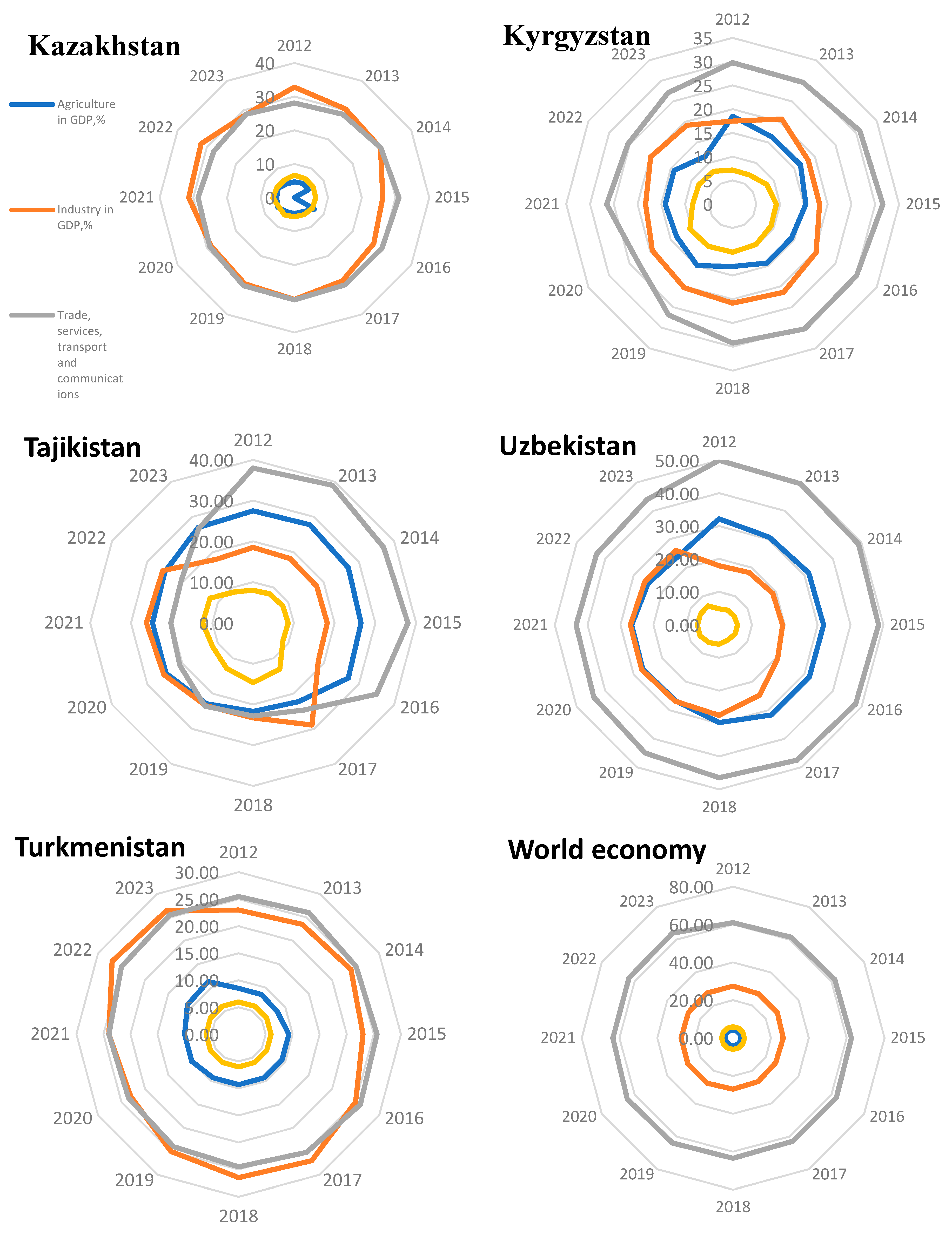

3.2. Identification of the Central Asia Economy Sectors Features

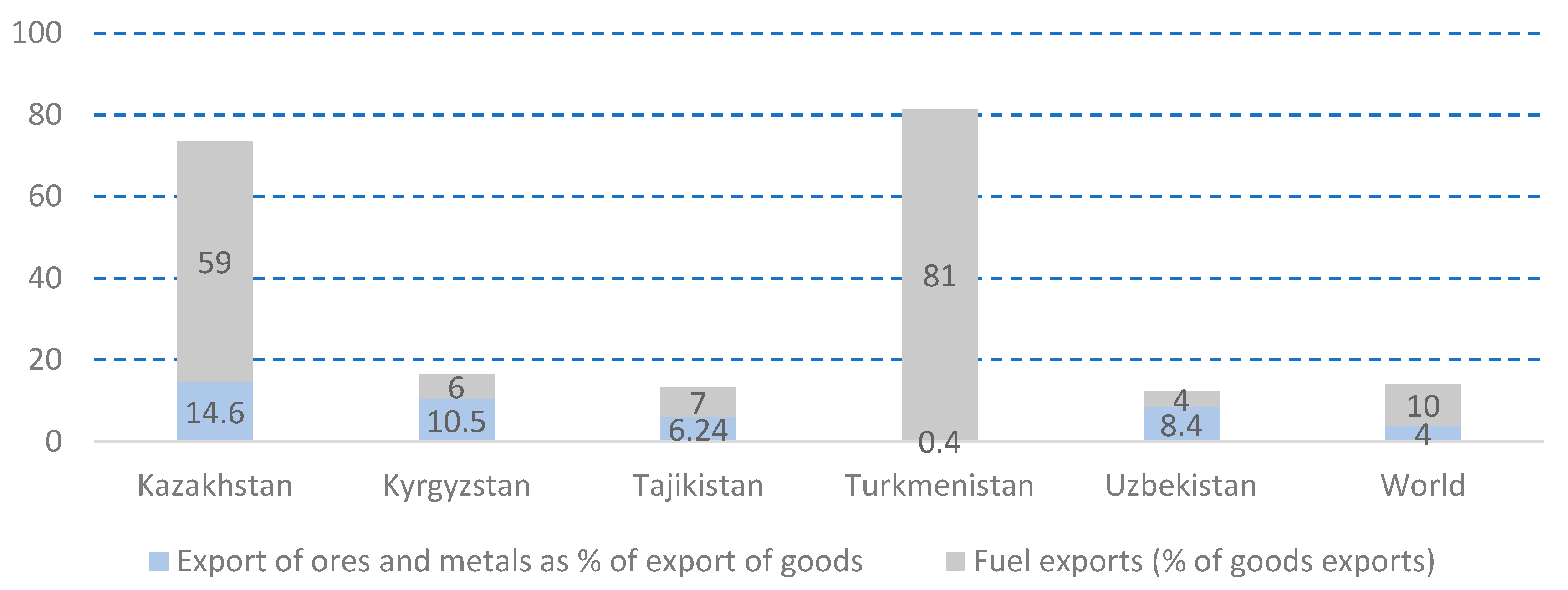

3.2.1. A Comparative Assessment of Key Fuel and Energy Resources

- -

- population growth (in 2023, the population growth rate in the region ranged from 1.3% to 2.1%, compared to the global average of 0.9%);

- -

- rising urbanization (urbanization rates in the region ranged from 38% to 58% in 2023, compared to the global average of 57%);

- -

- an increase in housing construction (for example, between 1990 and 2019, Kyrgyzstan’s housing stock increased by 30 million m²);

- -

- infrastructure development (in 2023, the share of services in Kazakhstan’s GDP reached 55.97%, aligning closely with the global average of 54.52%) [34].

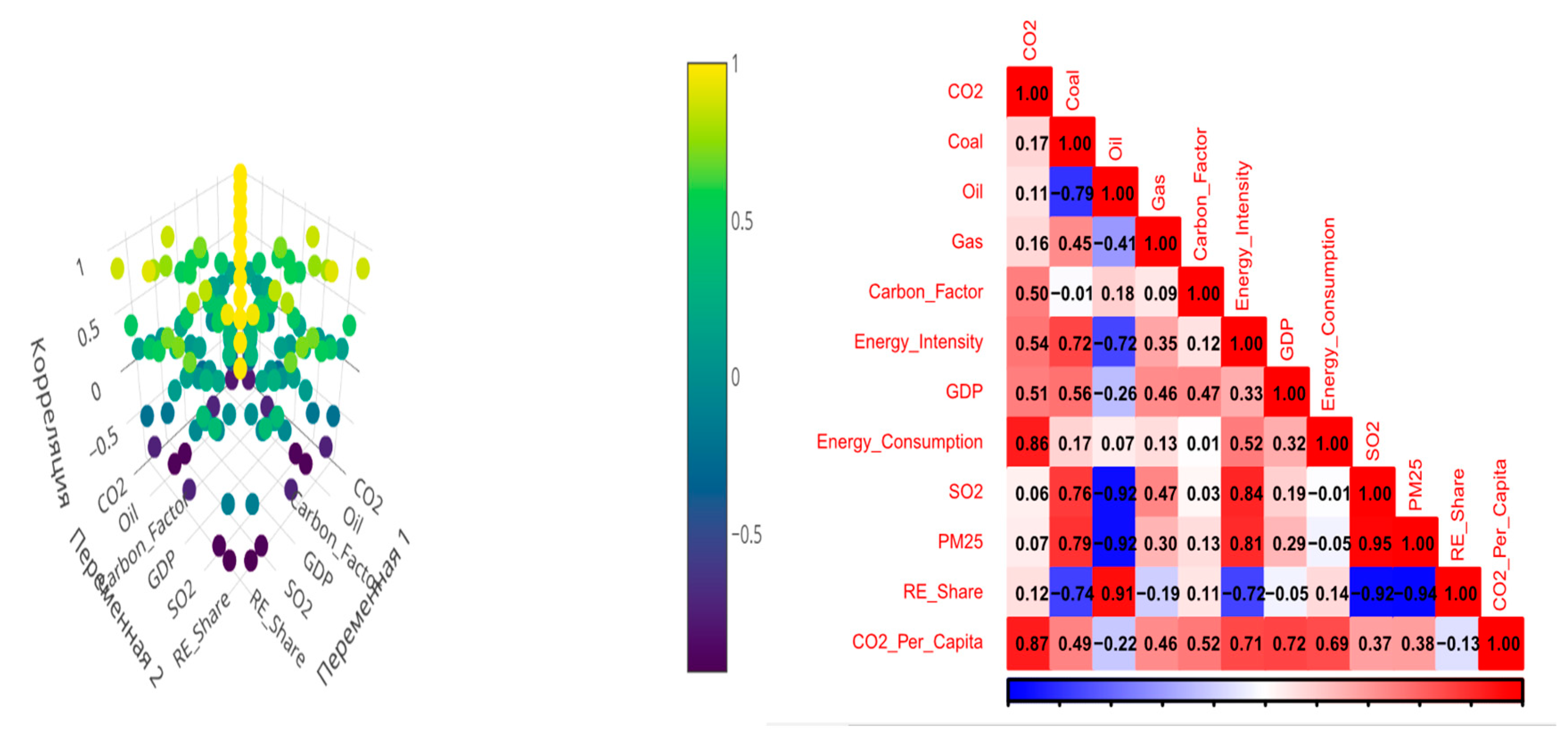

3.2.2. The Relationship Between the Economic Structure of Countries and the Level of Pollution

3.3. Assessment of the Impact of Ecological-Climatic Changes on the Regional Air Quality

3.3.1. Comparative Analysis of National GHG Emission Reduction Strategies

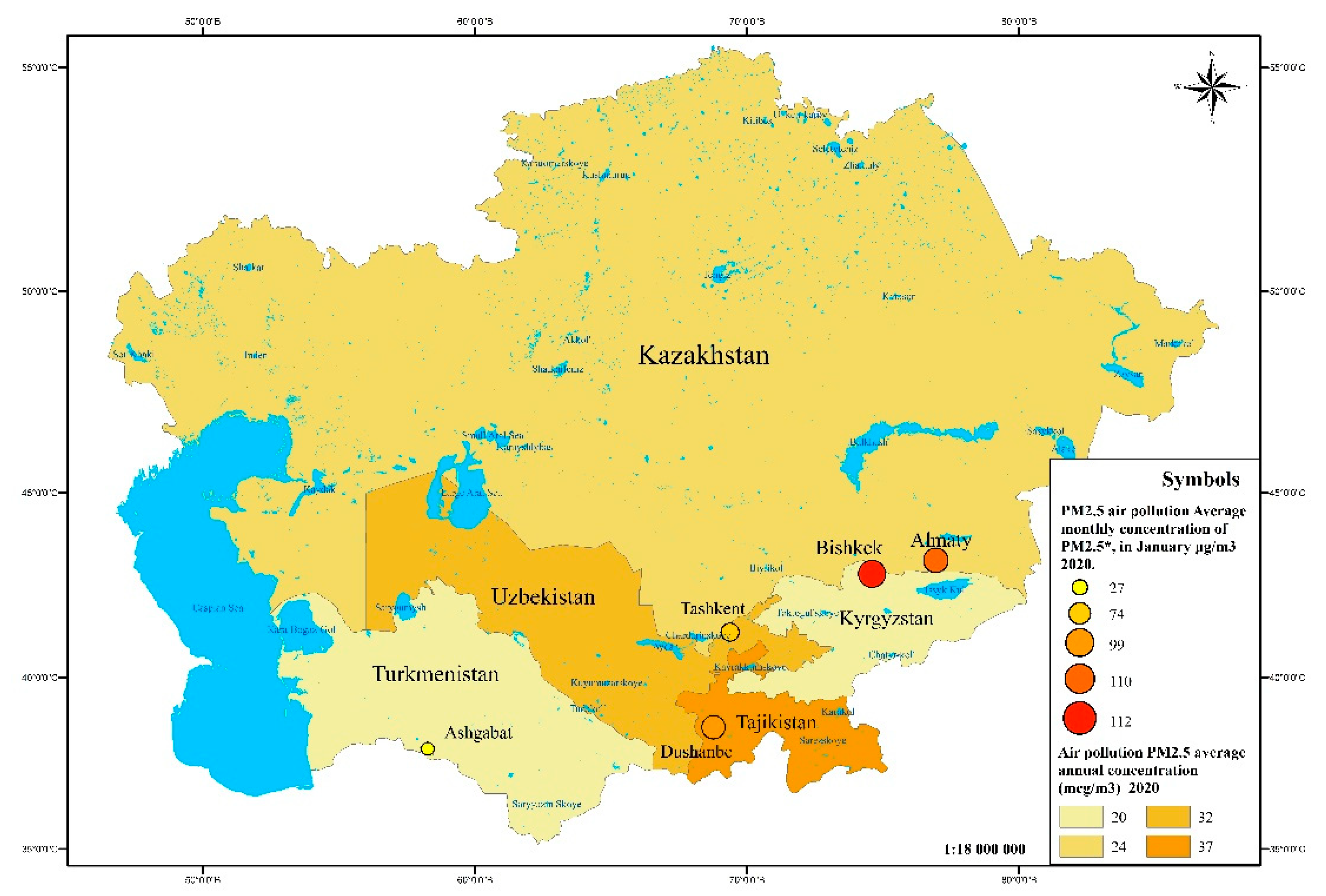

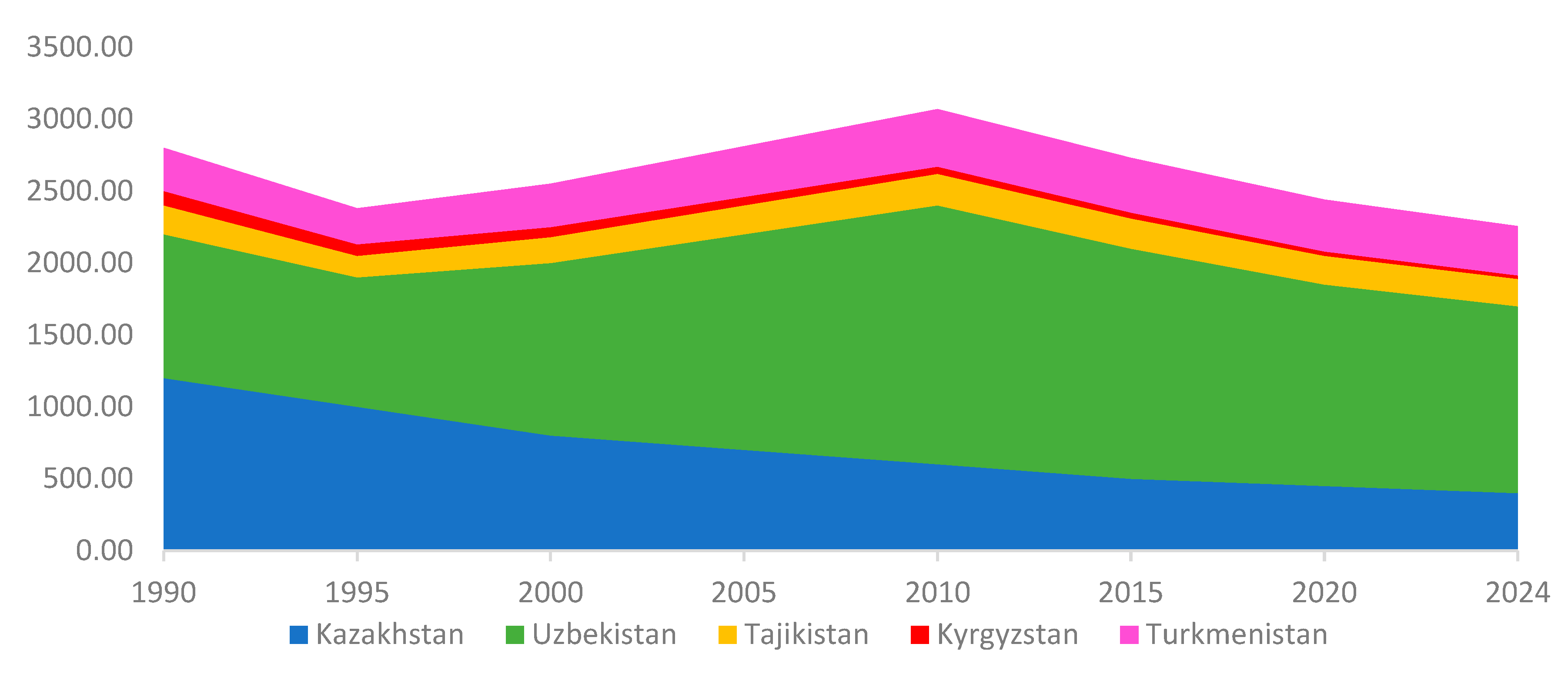

3.3.2. Study of the Dynamics of Fossil CO₂, PM2.5 and SO₂ Emissions in Central Asian Countries

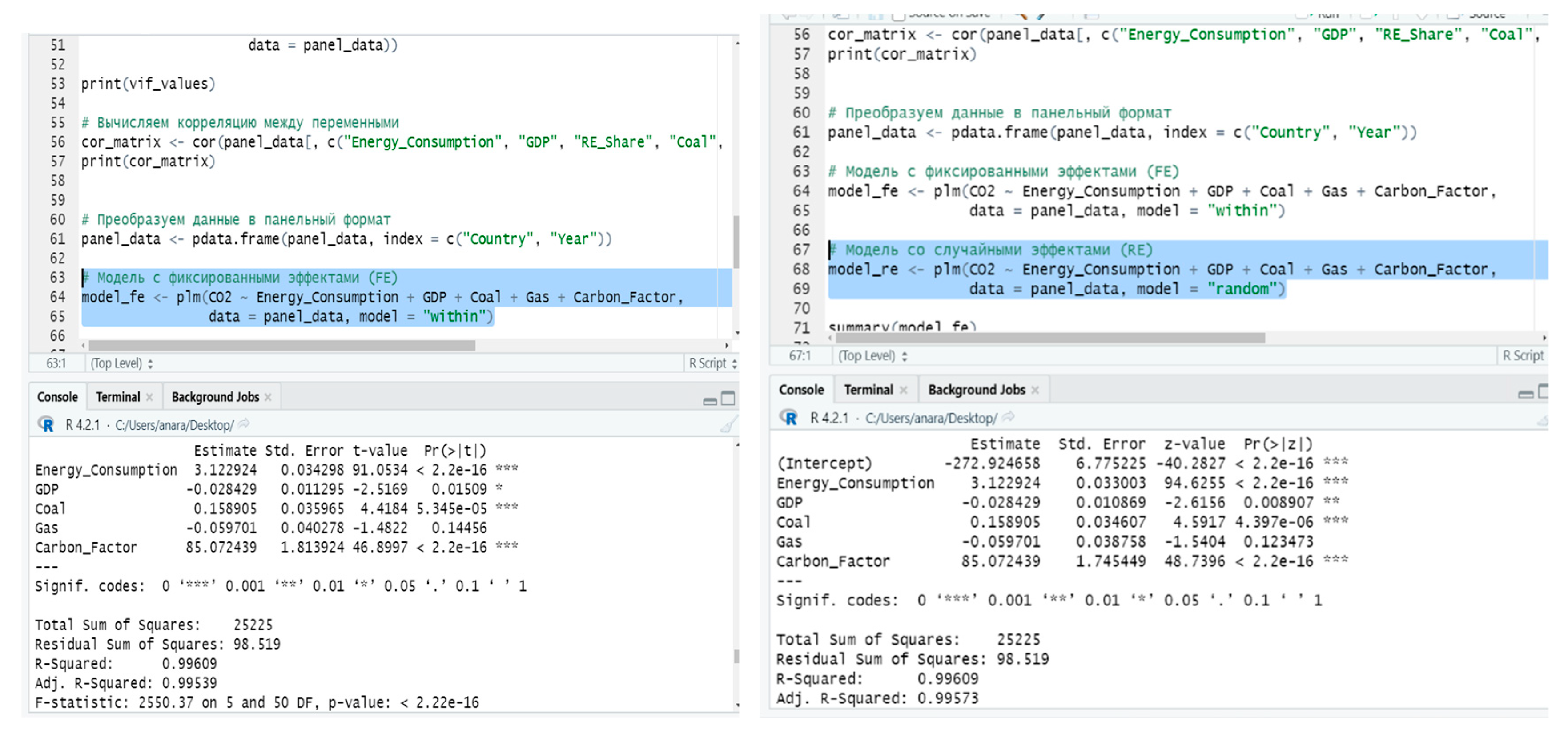

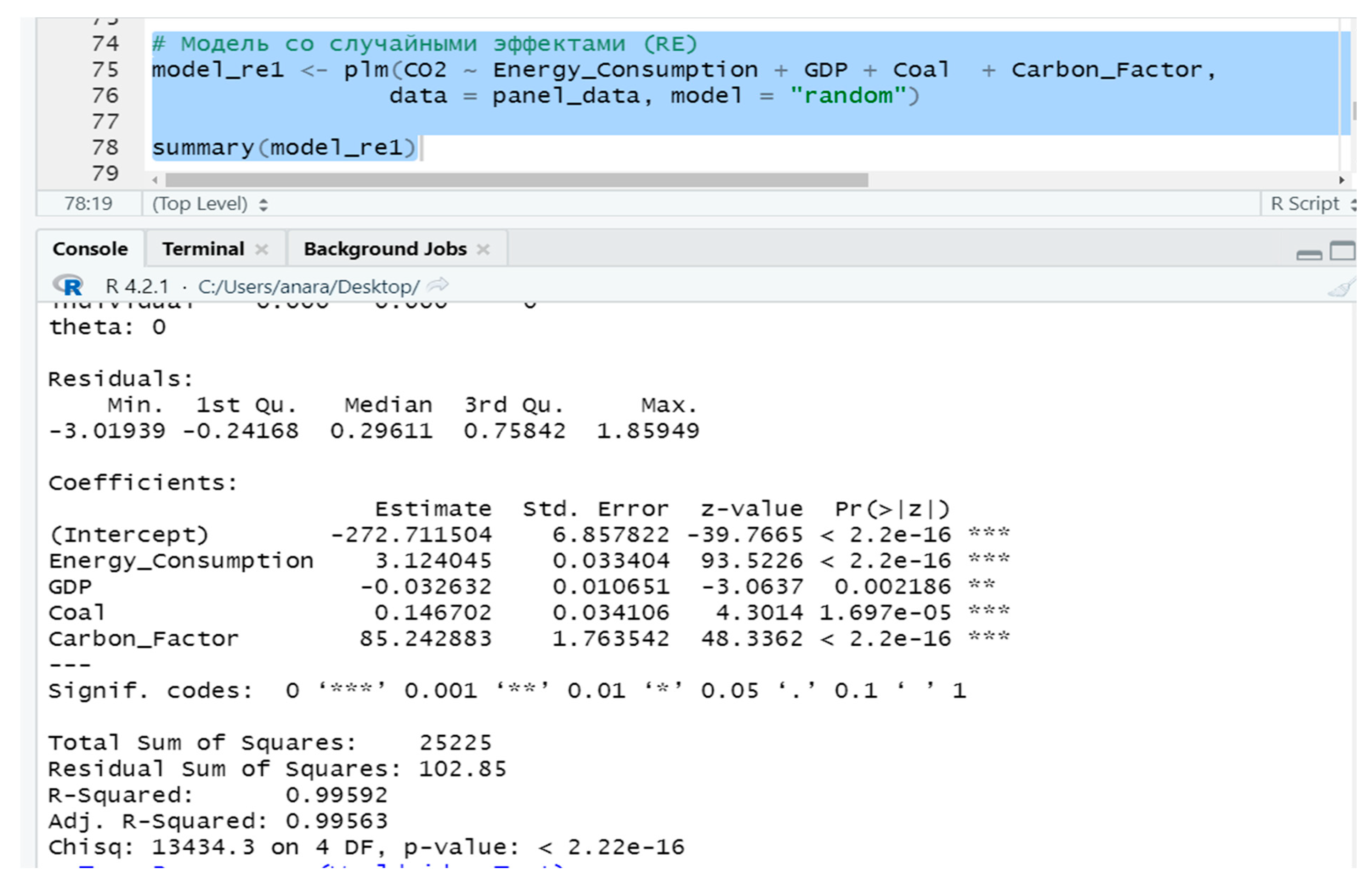

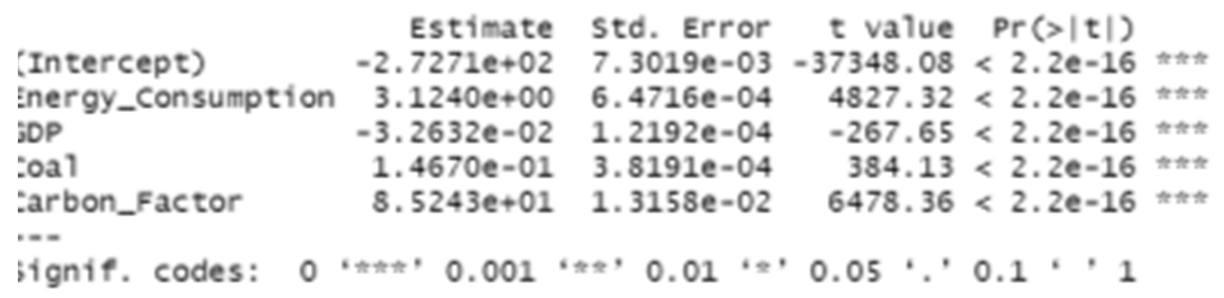

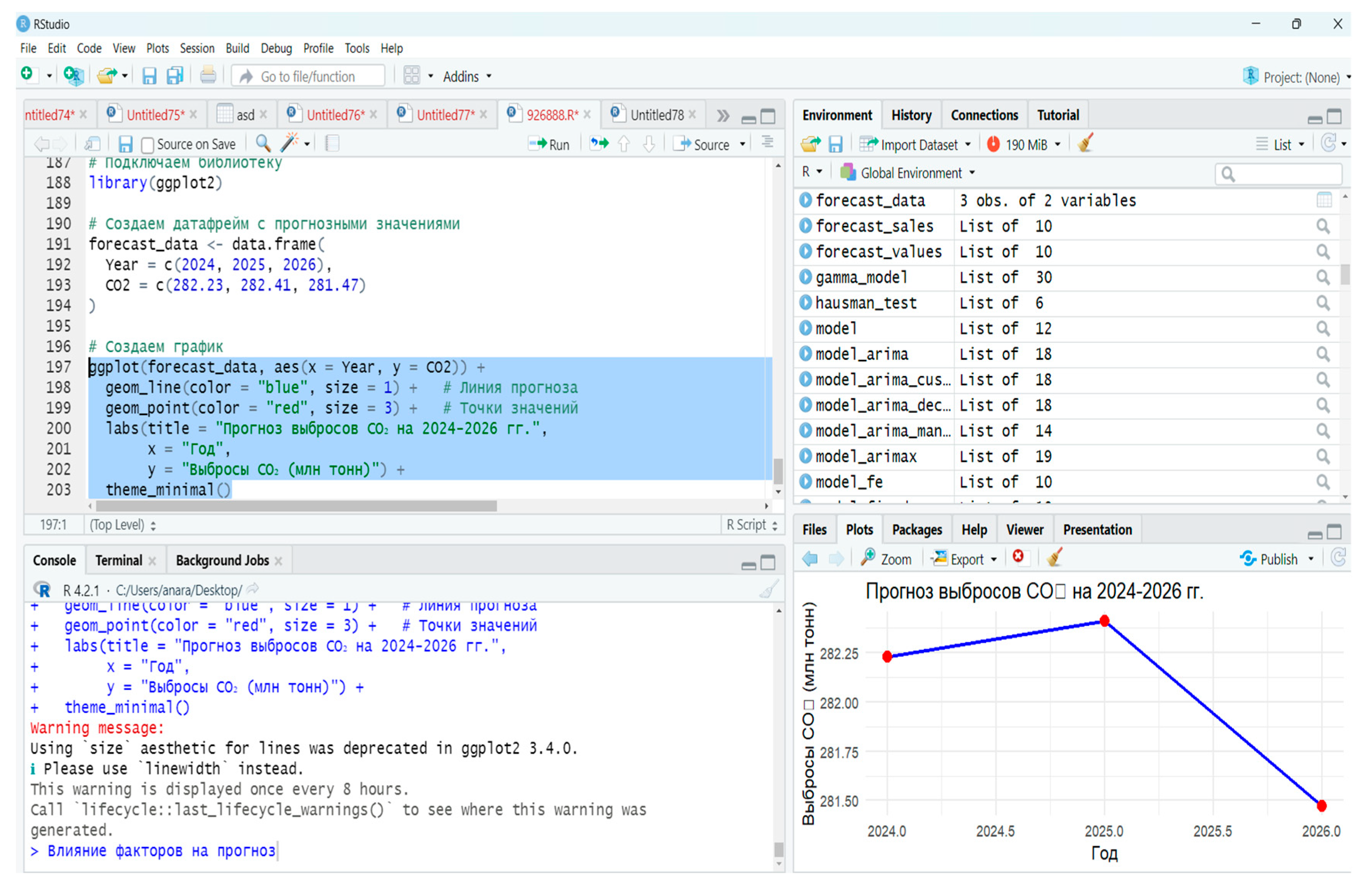

3.4. Econometric Modeling in the R Program

| Variables | |||

| y1 | CO2 emissions from fuel combustion, Mt | x6 | GDP, billion USD |

| x1 | coal consumption, Mt | x7 | Energy consumption, Mtoe |

| x2 | Oil product consumption, Mt | x8 | SO2 emissons,kt |

| x3 | natural gas consumption, Mt | x9 | PM2,5 emission, kt |

| x4 | global carbon factor, tCO2/toe | x10 | share of RES, % |

| x5 | energy intensity, koe/$15p | x11 | CO2 emissions per capita, t /person |

| Model |

Fixed effects model (FE) model_fe <- plm(CO2 ~ Energy_Consumption + GDP + Coal + Gas + Carbon_Factor, data = panel_data, model = “within”) |

Random effects model (RE) model_re<- plm(CO2 ~ Energy_Consumption + GDP + Coal + Gas + Carbon_Factor, data = panel_data, model = “random”) |

| Description |

Coefficients: Estimate Std. Error t-value Pr(>|t|) Energy_Consumption 3.122924 0.034298 91.0534 < 2.2e-16 *** GDP -0.028429 0.011295 -2.5169 0.01509 * Coal 0.158905 0.035965 4.4184 5.345e-05 *** Gas -0.059701 0.040278 -1.4822 0.14456 Carbon_Factor 85.072439 1.813924 46.8997 < 2.2e-16 *** Total Sum of Squares: 25225 Residual Sum of Squares: 98.519 R-Squared: 0.99609 Adj. R-Squared: 0.99539 F-statistic: 2550.37 on 5 and 50 DF, p-value: < 2.22e-16 |

Coefficients: Estimate Std. Error z-value Pr(>|z|) (Intercept) -272.924658 6.775225 -40.2827 < 2.2e-16 *** Energy_Consumption:3.122924 0.033003 94.6255 < 2.2e-16 *** GDP:-0.028429 0.010869 -2.6156 0.008907 ** Coal: 0.158905 0.034607 4.5917 4.397e-06 *** Gas: -0.059701 0.038758 -1.5404 0.123473 Carbon_Factor:85.072439 1.745449 48.7396 < 2.2e-16 *** Total Sum of Squares: 25225 Residual Sum of Squares: 98.519 R-Squared: 0.99609 Adj. R-Squared: 0.99573 Chisq: 13772 on 5 DF, p-value: < 2.22e-16 |

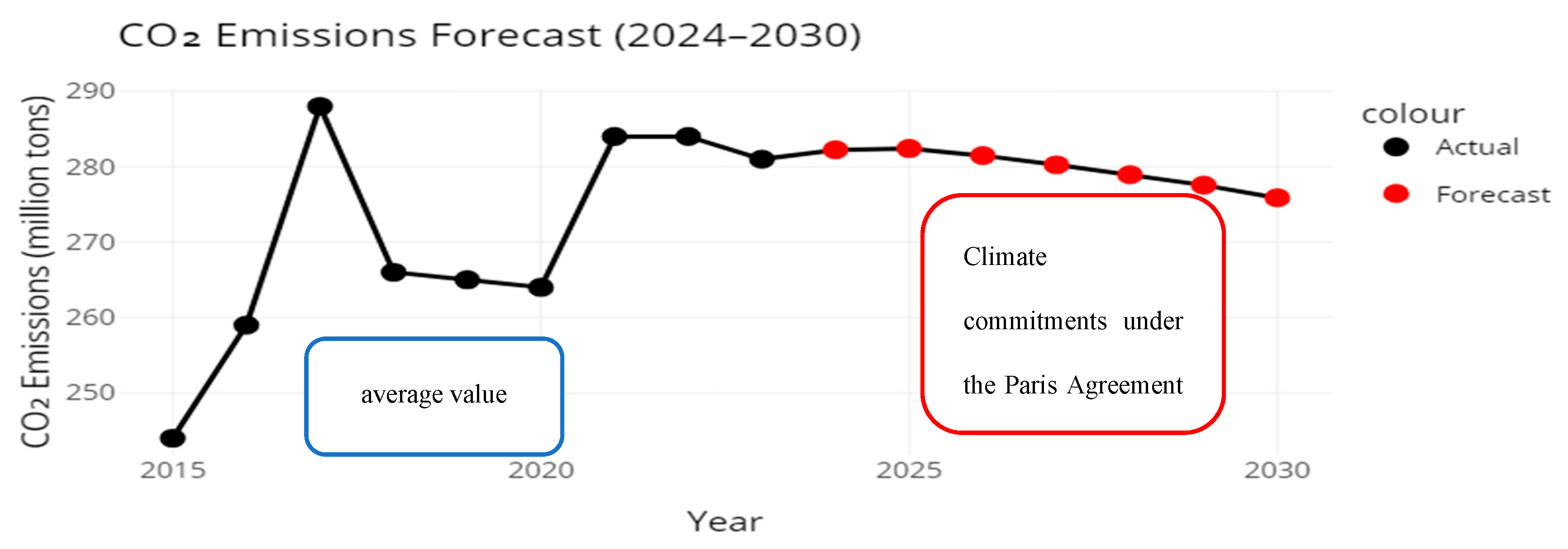

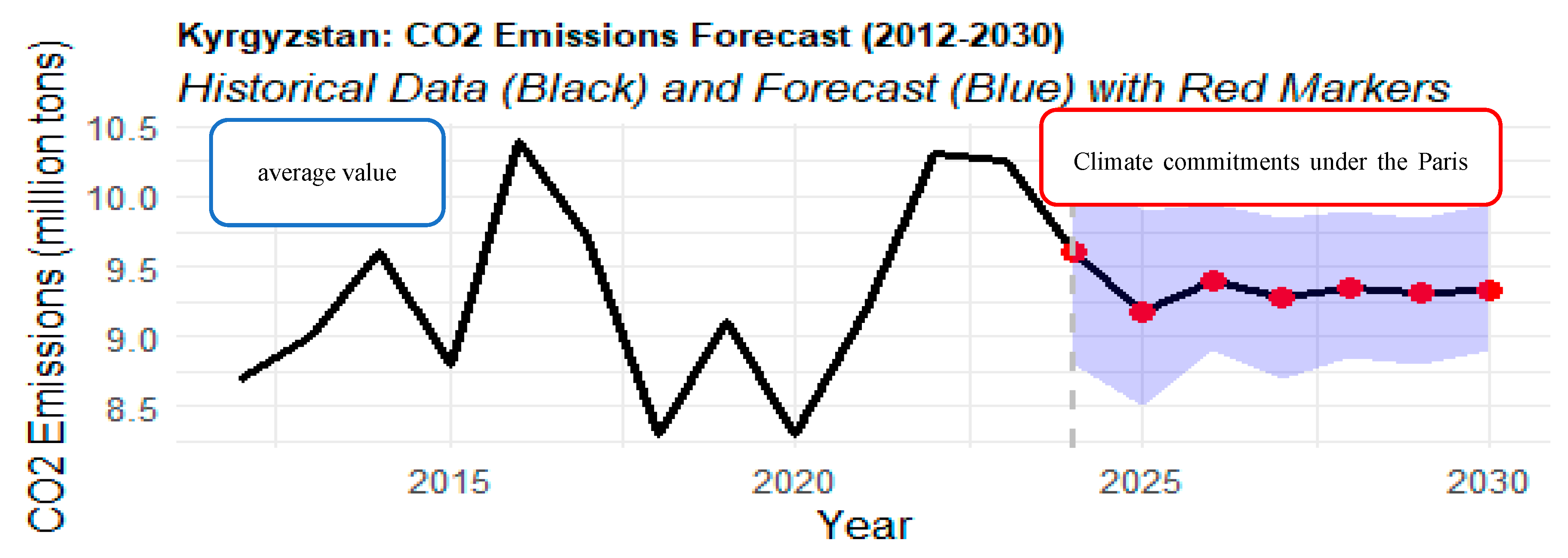

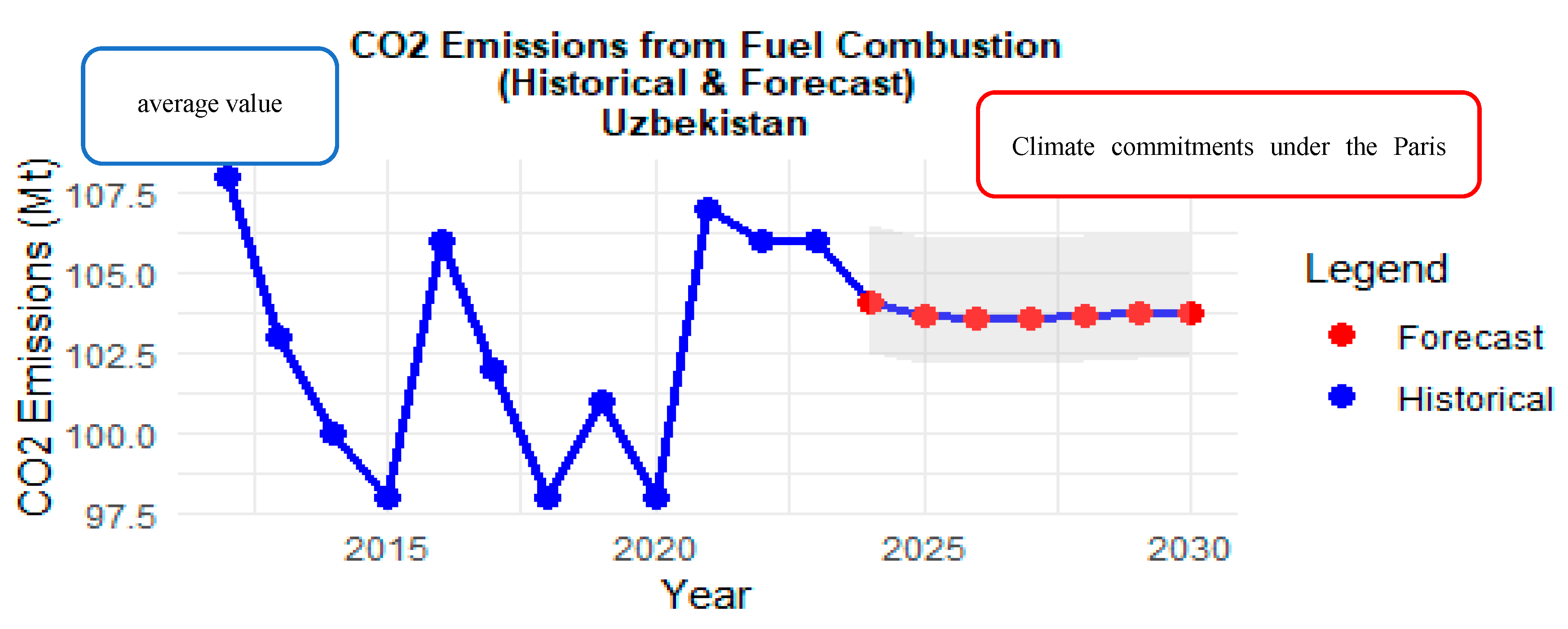

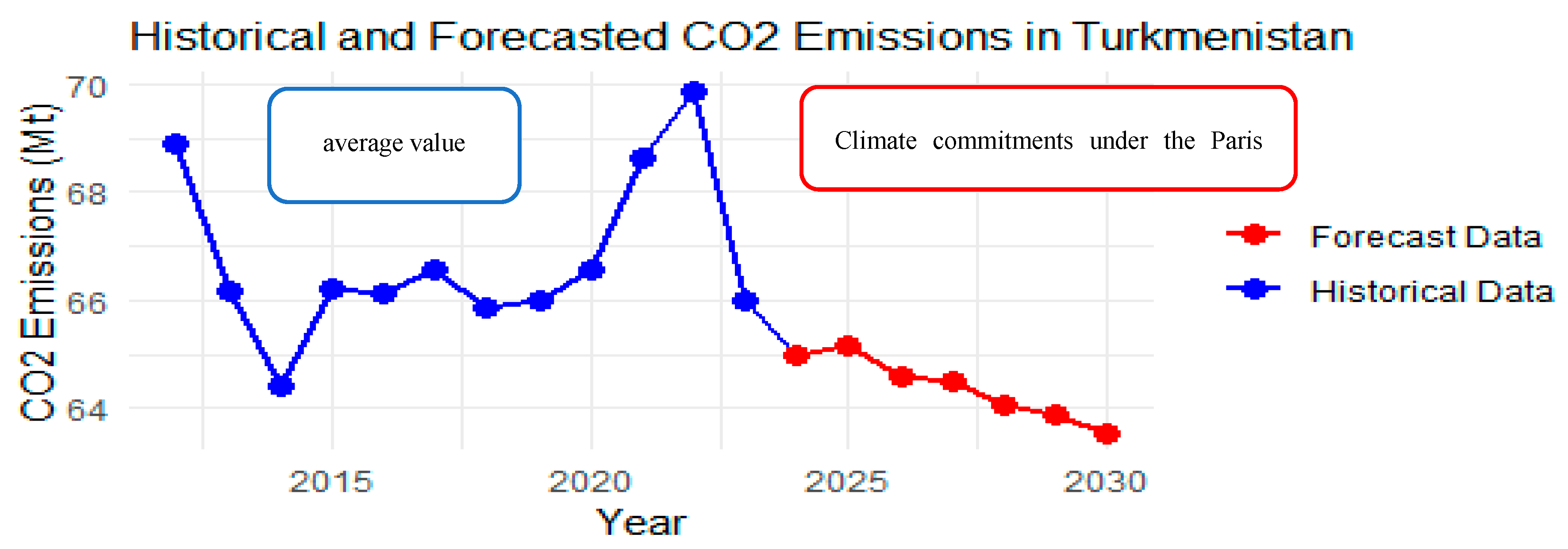

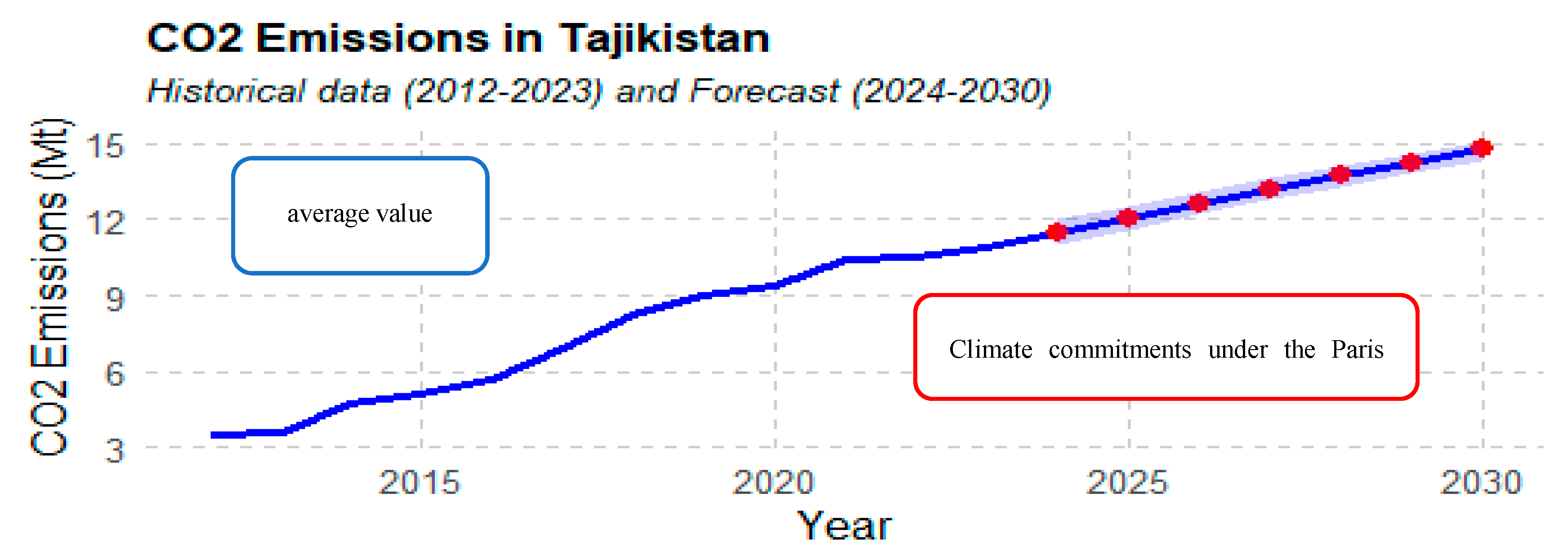

3.5. CO₂ Emissions Forecast for 2024-2030 by Country

3.5. Strategies in Central Asia for Implementing Measures to Reduce Air Pollution

| Factors/Conditions | Expected results | Risks | Sustainable Development Goals: Indicators |

| Population and economic growth | increase atmospheric emissions and place excessive pressure on key natural resources and ecosystems | drying up of the Aral Sea, water shortages, droughts, extreme heat, unstable precipitation patterns, dust storms | SDG3: Good Health and Well Being; SDG2: Zero Hunger; SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth; SDG10: Reduced Inequality; SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities SDG 13: Climate Action |

| Decarbonization of the economy | national low-carbon development strategies, strengthening regional cooperation mechanisms to identify measures for adaptation to climate change, priorities for the most effective allocation of investments, development of a joint environmental protection program for sustainable development in Central Asia. | Financial burden on the budget of countries; social risks associated with job losses, difficulties in adaptation and implementation of new technologies | SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy; SDG5: Gender Equality; SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth; SDG9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure; SDG11: Sustainable Cities and Communities; SDG12: Responsible Consumption and Production; SDG 13: Climate Change Adaptation. |

| Formation of a green strategy | investments in low-carbon technologies, replacement of coal with gas fuel at thermal power plants, “green” projects, including RES, energy-efficient and resource-efficient technologies, modernization of the water and energy complex, land reclamation projects, combating desertification and reforestation, creating a modern transport and logistics system, “transition” to sustainable transport, efficient waste management | significant investment in sustainable technologies and infrastructure will be required; social, technological and political risks | SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy; SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth; SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities; SDG12: Responsible Consumption and Production; SDG 13: Climate Change SDG 15: Life on Land |

| Implementation of international air quality standards, control systems and the best available technologies | Use of NetZero, water and waste management, Air Quality Control System, implementation of Air Quality Standards, energy strategy for Sustainability | Rising energy costs | SDG 3: Good Health and Well Being; SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure; SDG11: Sustainable Cityes and Communities; SDG12: Responsible Consumption and Production; |

| Environmental Aspects Registers (EnvAR) electronic registers of environmental aspects | Documentation and Analysis; Automatic tracking: waste, emissions, spills, energy consumption; Documentation and Analysis; Regulatory Compliance, Support for Environmental Management System; Transparency and Accountability |

Additional costs | SDG3: Good Health and Well Being; SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth; SDG11: Sustainable Cities and Communities; SDG12: Responsible Consumption and Production; SDG 13: Climate Change |

- Introducing United data metric

- Data standardization: development of common standards for collecting and analyzing air quality data, which will ensure comparability of data between countries. First of all, countries in the region need to move from declarative environmental regulation to strict, scientifically based standards governing emissions of CO₂, PM 2.5, SO₂ and other pollutants;

- Improved monitoring: the introduction of modern technologies for monitoring pollutants, which will allow for more accurate assessment of pollution levels and the adoption of measures to prevent them. This requires the creation of independent emission control agencies, the introduction of a mandatory air quality monitoring system based on modern technologies, including remote measurements and automated databases.

- The introduction of a digital reporting system and the integration of emission data into national and regional platforms will increase the transparency of environmental regulation and reduce corruption risks.

- 2.

- Changing the structure of national economies

- Investment in RES: increasing the share of RES: hydropower, solar and wind energy, which will help reduce dependence on fossil fuels and reduce carbon emissions. Countries can work with international financial institutions, such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, to obtain funding for RES projects. These organizations can offer both financial support and technical assistance. Also China’s involvement in solar and wind energy development could be an important factor in increasing the share of RES in the region. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have set goals to significantly increase the share of RES [24,25,39]. Other CACs may also develop national strategies to increase the share of RES;

- Adopting of Best Available Technologies: stimulating the transition to technologies that require less energy to produce and operate;

- It is necessary to modernize the existing coal infrastructure by introducing carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) technologies;

- Development of legislative initiatives: adoption of laws and regulations aimed at supporting clean technologies and reducing air pollution from stationary emission sources. For example, it is necessary to create and implement legislation that supports the use of RES, including tax incentives for investors, subsidies for solar and wind installations, and guarantees for the purchase of electricity from RES.

- Mitigation of the effects of climate change and adaptation to it. Key aspects include the development of highly accurate models for predicting climate risks and assessing the impact of emissions on the environment and public health.

- Combating desertification;

- Environmental protection in general, and in particular, protection of atmospheric air;

- Rational use of water and energy resources. Implementation of joint energy projects. The creation of joint projects, including RES projects between Central Asian countries can facilitate the exchange of experience and technologies. For example, joint research and development in the field of RES can lead to more efficient solutions adapted to local conditions;

- A combination of policy incentives and international cooperation is needed to significantly increase the share of RES in Central Asia. This includes the creation of a favorable legislative framework, targeted programs, and active interaction with international partners to attract investment and technology.

4. Discussion

- -

- the lack of a comprehensive analysis of CO₂, PM2.5 and SO₂ emissions in relation to the economic structure of the region

- -

- insufficient study of the impact of the sectoral structure of the economy on the level of emissions,

- -

- the lack of a comparative analysis of the effectiveness of national strategies to reduce pollution

- -

- regional differences in the level of air pollution.

- CACs are implementing measures to enhance air quality and decrease pollution. However, the imperfection of environmental taxation, limited financial resources, and the lack of effective systemic monitoring and control of air quality that meets modern international requirements and standards lead to the fact that there are no tangible changes in practice yet; the share of CO2 emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels per capita and per unit of GDP is one of the highest in the world. Assessing the impact of these factors will help identify additional opportunities to address the raised issues; however, the range of these questions falls within the realm of other scientific knowledge and requires detailed research. A quantitative assessment of the impact of these factors will allow us to identify additional opportunities for solving the problems raised, but the range of issues relates to the sphere of other scientific knowledge and requires detailed research.

- It has been established that there is no coordinated water and energy policy, transport and logistics system that would allow for the optimization of resource management, provision of regulation and implementation of strategic planning in the management of atmospheric air quality both within a single country and at the regional level. The study of these problems could resolve issues of interstate and country management and regulation aimed at the sustainable development of CACs.

- The key mechanisms for reducing atmospheric emissions are the transformation of the region’s economies in the context of regional development, interstate cooperation. It is need to significantly increase investments for the modernization of the water and energy complex based on low-carbon technologies and projects, including RES, combating desertification and forest restoration, the formation of sustainable transport and logistics system. It is important to harmonize regional legislation of the CACs with the best world practices in matters of air protection, to implement the environmental norms, standards, to create the modern information database of pollutants using GIS technologies. Regional integration should be considered as a necessary condition for achieving the SDGs. It guarantees the security of water, energy and food of CACs, as well as successfully solving common environmental problems, including air pollution.

- Further research into pollutant emissions and their impact on the environment in Central Asia could cover several key areas. An in-depth analysis of the spatio-temporal dynamics of CO₂, PM2.5 and SO₂ emissions is needed using high-precision modeling methods taking into account spatio-temporal changes and the influence of economic factors. It is important to develop models that assess the effectiveness of pollution reduction mechanisms such as carbon taxation and incentives for renewable energy sources. A promising area is forecasting the consequences of climate change on air quality and the regional economy. Research into the impact of pollution on human health and ecosystems is also needed to help develop evidence-based strategies for reducing emissions and promoting sustainable development in Central Asia.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A.

Appendix B. Supplementary Data

Appendix С

Appendix D

| periods | Prediction Kyrgyzstan | Prediction Uzbekistan | Prediction Turkmenistan | Prediction Tadjikistan |

| 2024 | 9.59675 | 104.114 | 64.9670 | 11.4958 |

| 2025 | 9.17165 | 103.640 | 65.1498 | 12.0735 |

| 2026 | 9.40098 | 103.560 | 64.5644 | 12.6359 |

| 2027 | 9.27727 | 103.588 | 64.4725 | 13.1826 |

| 2028 | 9.34401 | 103.647 | 64.0636 | 13.7135 |

| 2029 | 9.30800 | 103.715 | 63.8584 | 14.2287 |

| 2030 | 9.32742 | 103.785 | 63.5223 | 14.7282 |

References

- Asrar,G., Lucas,P.L., van Vuurenet, D.P., Pereira, L.,Vervoort,J., Bhargava,R. (2019). Chapter 19: Outlooks in GEO-6. UN Environment (Ed) In: Global environment outlook - GEO-6: Healthy Planet Healthy People. pp.463-469.Cambridge University Press: Cambridge,United Kingdom. ISBN 9781108707664. [CrossRef]

- Bobylev, S.N., Solovyeva, S.V., Astapkovich, M. (2022). Air quality as a priority issue for the new economy. The World of the New Economy,16(2),76-88. [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, J.& Hoen, H. W. (2013). Institutional Reform in Central Asia: Politico-economic Challenges. Routledge: London and New York, 285p. ISBN 978-0-415-60200-6.

- Tokaev,K.K.(2024).Renessans Tsentral’noy Azii: Na puti k ustojchivomu razvitiju i protsvetaniju. Central Asian [Renaissance: Towards Sustainable Development and Prosperity].https://www.zakon.kz/politika/6444287 (in Russian).

- Hejfets, B. A. &Chernova, V. Ju. (2024). Novyj vzglyad na strategiju economicheskoj integratsii Rossii so stranami Tsentral’noj Azii v sovremennyh geopoliticheckih realiyah mirovoj ekonomiki. [A new look at the strategy of economic integration of Russia with the countries of Central Asia in the modern geopolitical realities of the world economy]. Rossiya i sovremennyj mir.,1(122), 7-24. [CrossRef]

- Ziyadullaev,N.S. (2022).Geo-Economic Priorities of Region-Building in Central Asia. Russian Foreign Econ. J, 4, 86-102. [CrossRef]

- Adambekova, A. , Kozhagulov, S., Quadrado, J. C., Salnikov, V., Polyakova, S., Tazhibayeva, T., Ulman, A. (2024). Reduction of Atmosphere Pollution as Basis of a Regional Circular Economy: Evidence from Kazakhstan. [ Preprint]. Preprints org. [CrossRef]

- Sabyrbekov, R. , Overland, I., Vakulchuk, R(Eds). (2023).Introduction to Climate Change in Central Asia. In Climate Change in Central Asia: Decarbonization, Energy Transition and Climate Policy (pp. 1-11).Springer: Cham/ Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-031-29830-1. [CrossRef]

- Tursumbayeva, M. , Muratuly, A.,Baimatova, N., Karaca, F.,Kerimray, A. (2023).Cities of Central Asia: New Hotspots of Air Pollution in the World.Atmos. Environ, 309, 119901. [CrossRef]

- Bespalyy,S.,& Petrenko,A. (2024).Analysis of public transport in Central Asian cities in comparison with leading cities in Southeast Asia and Europe: the search for sustainable urban solutions. E3S Web of Conferences 535, 04011 -. [CrossRef]

- Assanov, D.; Kerimray, A.; Batkeyev, B.; Kapsalyamova, Z. (2021). The effects of COVID-19- related driving restrictions on air quality in an industrial city. Aerosol Air Qual. Res., 21 (9), 200663. [CrossRef]

- Amaratunga, D., Anzellini, V., Guadagno, L.;,Hagen, J. S,, Komac, B., Krausmann, E., ... & Wood, M. (2023). Regional Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction2023: Europe and Central Asia. United Nations office for disaster risk reduction, Geneva, https://www.undrr.org/report/rar-2023-europe-and-central-asia.

- Lioubimtseva, E. , & Henebry, G. M. (2009). Climate and environmental change in arid Central Asia: Impacts, vulnerability, and adaptations. J. Arid Environ, 73(11), 963-977. [CrossRef]

- Salnikov, V., Turulina, G., Polyakova, S., Petrova, Y. & Skakova, A. (2015). Climate change in Kazakhstan during the past 70 years. Quaternary Int., 358, 77-82. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. , Chen, X., Kurban, A., Van de Voorde, T., De Maeyer, P., & Zhang, C. (2021). Coupled SSPs-RCPs scenarios to project the future dynamic variations of water-soil-carbon-biodiversity services in Central Asia. Ecol. Indic., 129, 107936. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. , Chen, Y., Li, Z., Fang, G., Wang, F., & Liu, H. (2020).The impact of climate change and human activities on the Aral Sea Basin over the past 50 years. Atmos. Res., 245, 105125. [CrossRef]

- Eurasian Development Bank(2023). Vinokurov, E. Eurasian Development Bank(2023). Vinokurov, E.,Ahunbaev, A.,Usmanov, N.,Sarsembekov, T. Regulirovanie vodno-energeticheskogo kompleksa Tsentral’noj Azii [Regulation of the water energy complex of Central Asia]. Doklady i rabochie dokumenty.22/4.Almaty, Moscow: Eurasian Development Bank.https://eabr.org/analytics/special-reports/regulirovanie-vodno-energeticheskogo-kompleksa-tsentralnoy-azii.

- Reyer, C. P. , Otto, I. M., Adams, S., Albrecht, T., Baarsch, F., Cartsburg, M., Coumou, D., Eden, A., Ludi, E., Marcus, R., Mengel, M., Mosello, B., Robinson, A., Schleussner, C.F., Serdeczny, O., & Stagl, J. (2017). Climate change impacts in Central Asia and their implications for development. Reg. Environ. Change. [CrossRef]

- Tursunova, A. Tursunova, A., Medeu, A., Alimkulov, S., Saparova, A., & Baspakova, G. (2022).Water resources of Kazakhstan in conditions of uncertainty. J. Water Land Dev., 54, 138-149. [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization.(2024). CLIMA, T., & Te, W.(Eds). State of the Climate in Asia2023. Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization. ISBN 978-92-63-11350-4.

- Mehta, K. , Ehrenwirth, M., Trinkl, C., Zörner, W., & Greenough, R. (2021). The energy situation in Central Asia: A comprehensive energy review focusing on rural areas. Energies. [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P., O’Sullivan,M., Jones, M.W.,Andrew, R.M.,Gregor, L., Hauck, J., Le Quéré, C., Luijkx, et al. (2022).Global Carbon Budget 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 14 (11),4811-4900. 11). [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.(2019). Sustainable Infrastructure for Low-Carbon Development in Central Asia and the Caucasus: Hotspot Analysis and Needs Assessment, Green Finance and Investment. OECD Publishing. ISBN 978-92-64-64520-2. [CrossRef]

- Adilet.zan.kz. (2023). The Strategy on Achieving Carbon Neutrality by 2060. https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/U2300000121 (accessed 20.01. 2025).

- Adilet.zan.kz. (2013). Concept on Transition towards Green Economy by2050.URL https://www.greenkaz.org/ images/for_news/pdf/npa/koncepciya-po- perehodu.pdf (accessed 20. 01.2025).

- Beisenova, R. , Kuanyshevich, B. Z., Turlybekova, G., Yelikbayev, B., Kakabayev, A. A., Shamshedenova, S. & Nugmanov, A. (2023). Assessment of Atmospheric Air Quality in the Region of Central Kazakhstan and Astana. Atmosphere. [CrossRef]

- Gingras,Y.(2016). Bibliometrics and Research Evaluation: Uses and Abuses. The MIT Press. ISBN electronic:9780262337656. [CrossRef]

- World Bank.(n.d.).TheGlobalEconomy.com: Global economy, world economy. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com.

- United Nations Environmental Programme.(2021). Regulating Air Quality: The First Global Assessment of Air Pollution Legislation. UNEP. Publishing Services Section. UNON. ISBN: 978-92-807-3872-8 https://www.unep.org.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. (n.d.). Data Portal https://w3.unece.org/SDG/ru/Indicator?id=28.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. (2019). A1–Vybrosy zagryaznyayushih veshestv v atmosphernyj vozduh. UNECE, 16aya Sessiya Sovmestnoj Tselevoj gruppy po ekologicheskim pokazatelyam i ststistike, Geneva, 28-29 oktyabrya 2019 [16th Session of the Joint Task Force on Environmental Indicators and Statistics]. UNECE. Geneva, 28-29 October 2019. https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/stats/documents/ece/ces/ge.33/2019/mtg4/5_3_RU_Ind_A1_A2_Air.pdf.

- Enerdata. (2024).World Energy&Climate Statictics-Yearbook2024. https://yearbook.enerdata.net/.

- World Bank Group. (n.d.). World Bank Data.World Bank.https://data.worldbank.org.

- US.Energy Information Administration.(n.d.).The Global Econony.The Gobal Economy.https://www.theglobaleconomy.com.

- Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (2025).https://stat.gov.kz/ (accessed 20.01.2025).

- United Nations Development Programme.(2022).The 8th National Communication and the 5th Biennial Report of the Republic of Kazakhstan to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change https://www.undp.org/kazakhstan/publications/8th-national-communication-and-5th-biennial-report-republic-kazakhstan-un-framework-convention-climate-change.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.(2017).The 3rd National Communication of the Kyrgyz Republic under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/NC3_Kyrgyzstan_English_24Jan2017.pdf.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.(2022). The 4th National Communication of the Republic of Tajikistan to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/4NC_TJK_ru_0.pdf.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.(2016).The 3rd National Communication of the Republic of Uzbekistan under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/TNC_Uzbekistan_under_UNFCCC_rus.pdf.

- Ministry of Foring Affairs of Turkmenistan.(2019).National Strategy Turkmenistan on Climate Change, 2019. https://www.mfa.gov.tm/index.php/en/news/1615.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2006). 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories.Chapter 1, Part 1. Introduction to the Guidelines.p.16.https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.(2006). 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Chapter 4 LULUCF Agriculture, forestry and other land use. p.101. https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/(in Russian).

- Mazilov,S.I., Rajkova,S.V., Gusev,Ju.S., Pozdnyakova,M.V., Komleva,N.E., Miktrov,A.N. (2023). Vliyanie polljutantov atmosphernogo vozduha na zdorov’e naseleniya: naukometrichesrij analiz zarubehznyh angloyazychnyh publikatsij 2017-2022 gg. [The influence of atmospheric air pollutants on the health of the population: scientometric analysis of foreign English-language publications from 2017-2022]. Meditsina truda I ecologiya cheloveka. 4,63-81. [CrossRef]

- Han, Q., Luo, G., Li, C., Shakir, A., Wu, M. & Saidov, A. (2016). Simulated grazing effects on carbon emission in Central Asia. Agric. For. Meteorol., 216, 203-214. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, S. M. , Manousakas, M., Diapouli, E., Kertesz, Z., Samek, L., Hristova, E., ... & IAEA European Region Study GROUP.(2020). Ambient particulate matter source apportionment using receptor modelling in European and Central Asia urban areas. Environ. Pollution, 266, 115199. [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank Institute.(2014). Connecting Central Asia with Economic Centers. (124pp.) Asian Development Bank Institute. Tokyo, Japan..ISBN 978-4-89974-050-8 (PDF).

- Ness, J. E., Garvin Heath, & Ravi,V. (2022). An Overview of Policies Influencing Air Pollution from the Electricity Sector in Central Asia. (NREL/TP-7A40-81861).National Renewable Energy Laboratory.. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy23osti/81861.pdf.

- Min, J. ,Yan, G., Abed, A. M., Elattar, S., Khadimallah, M. A., Jan, A., & Ali, H. E.(2022). The effect of carbon dioxide emissions on the building energy efficiency. Fuel. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Krigsvoll, G., Johansen, F., Liu, Y., & Zhang, X. Carbon emission of global construction sector.(2018) Renew. sustain. energy rev., 81, 1906-1916. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.(2021). Ekologicheskie pokazateli i osnovannye na nih otsenochnye dokladyVostochnaya Evropa,Kavkaz i Tsentral’naya Aziya. [Environmental indicators and assessment reports based on them Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia]. (ECE/CEP/140). UN.ISBN978-92-1-416026-7.https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-12/ECE-CEP-140.

- Isiksal, A.Z. (2023).The role of natural resources in financial expansion: evidence from Central Asia. Financ Innov., 9. [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. (2023).Regional’naya strategiya po adaptatsii k izmeneniju klimata v Tsentral’noj Azii. [Regional Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change in Central Asia]. (p.25). https://greencentralasia.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Strategy_rus-2.pdf. (in Russin).

- Esekina, А. S.,TokpaevZ.R., Cherednichenko, A. V., Kasenov, A. A., Ermahanova, E.M., Kasenova, D. A., ... & Shorman, A. T.(2023). Analiz dinamiki natsional’nyh vybrosov i pogloshenij parnikovyh gazov v Kazakhstane za 2012-2021 gg. [Analysis of the dynamics of national emissions and absorption of greenhouse gases in Kazakhstan for 2012-2021].Hydrometeorology and ecology,3, 6–23. [CrossRef]

- Van‘t Wout, T., Celikyilmaz, G., & Arguello, C. (2021).Policy analysis of Nationally Determined Contributions in the Europe and Central Asia region: 2021. (pp.137).Food & Agriculture Organization.ISBN978.92.5.135360.8.

- Nguyen, A. T. (2019). The relationship between economic growth, energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions: evidence from Central Asia. Eur. J. Bus. Econ.,12(24), 1- 15. [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M. , Guizzardi, D., Muntean, M., Schaaf, E., Solazzo, E., Monforti-Ferrario, F., Olivier, J.G.J., Vignati, E. (2020).Fossil CO2 emissions of all world countries - 2020 report. (EUR 30358 EN). Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978-92-76-21515-8.

- World Bank. (n.d.).Upravlenie kachestvom vozduha v Respublike Tajikistan (Russian). [Air quality management in the Republic of Tajikistan]. Washington, D.C.: WorldBankGroup. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099081723150529416/P18001408270f40e80b900006bd7a098720.

- Mukhtarov, R. , Ibragimova, O. P., Omarova, A., Tursumbayeva, M., Tursun, K., Muratuly, A., ... & Baimatova, N. (2023). An episode-based assessment for the adverse effects of air mass trajectories on PM2. 5 levels in Astana and Almaty, Kazakhstan. Urban Climate. 49, 101541. [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, S., Anhäuser, A., Farrow, A., Thieriot, H., Kumar, A., & Myllyvirta, L. Global SO2 emission hotspot database. Delhi: Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air & Greenpeace India. October 2020. 48pp. https://energyandcleanair.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/SO2report1.pdf.

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2023, November 20). Emissions Gap Report 2023: Broken record – Temperatures hit new highs, yet world fails to cut emissions (again). https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2023.

- Eurasian Development Bank.(2023). Vinokurov, E. Eurasian Development Bank.(2023). Vinokurov, E., Conrad,A.,Zaboev, A.,Klochkova, E., Malakhov, A., Pereboev, V. Global Green Agenda in the Eurasian Region. Eurasian Region on the Global Green Agenda. (Reports and Working Papers 23/2). Almaty: Eurasian Development Bank, 2023.SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4456821.

- International Energy Agency (2021).Cross-Border Electricity Trading for Tajikistan: A Roadmap. (IEA Publications). https://www.iea.org/reports/cross-border-electricity-trading-for-tajikistan-a-roadmap.

- Zheng, B., Tong, D., Li, M., Liu, F., Hong, C., Geng, G., Li, H., Li, X., Peng, L., Qi, J., Yan, L., Zhang, Y., Zhao, H., Zheng, Y., He, K., Zhang, Q. (2018). Trends in China’s anthropogenic emissions since 2010 as the consequence of clean air actions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 14095-14111. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Lu, X., Du, P., Zheng, H., Dong, Z., Yin, Z., ... & Hao, J. (2023).The increasing role of synergistic effects in Carbon Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement, and its Associated Health benefits in China. Engineering, 20, 103-111. [CrossRef]

- Mukhamediev,R.I., Mustakayev,R., Yakunin,K., Kiseleva,S., Gopejenko,V. (2019).Multi-Criteria Spatial Decision Making Supportsystem for Renewable Energy Development in Kazakhstan, in IEEE Access., 7, 122275-122288. [CrossRef]

- Faizi, A. , Ak, M. Z., Shahzad, M. R., Yüksel, S., & Toffanin, R. (2024). Environmental Impacts of Natural Resources, Renewable Energy, Technological Innovation, and Globalization: Evidence from the Organization of Turkic States. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. , Liu, L.,Gao, J. (2020). Adapting to climate change: gaps and strategies for Central Asia. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2023). Emissions Gap Report 2023: Broken Record – Temperatures hit new highs, yet world fails to cut emissions (again). (UNEP, DEW/2589/NA). Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environment Programme. ISBN: 978-92-807-4098-1. [CrossRef]

- United Nations.(2014). The Vienna Programme of Action for the Landlocked Developing Countries for the decade 2014-2024. United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, Second UN Conference on Landlocked Developing Countries, Vienna–November 2014. https://www.un.org/.

- International Energy Agency.(2021). Net Zero by 2050. A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector. (Special Report)..https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050.

- Zhao, C., Liu, B., Wang, J., Xue, R., Shan, Y., Cui, C., ... & Dong, K. (2023). Emission accounting and drivers in CACs. Environ. Sci. Pollution Res., 30(46), 102894-102909. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Krigsvoll, G., Johansen, F., Liu, Y., & Zhang, X. (2018). Carbon emission of global construction sector. Renew. sustain. energy rev., 81, 1906-1916. [CrossRef]

- European Commission.(2020). Determining the environmental impacts of conventional and alternatively fuelled vehicles through LCA. Final Report for the European Commission, DG Climate Action. (Contract Ref. 34027703/2018/782375/ETU/CLIMA.C.4). https://climate.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020.09/2020_study_main_report_en.pdf.

- International Transport Forum.(2023). ITF Transport Outlook 2023. (216pp.) Published by OECD/ITF. [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, P. Kahn Ribeiro, P. Newman, S. Dhar, O.E. Diemuodeke, T. Kajinom D.S. Lee, S.B, Nugroho; X. Ou, A. Hammer Strømman, J.(2022). Whitehead. 2022: Transport. In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- Kachestvo vozduha v czentralnoj azii pora bit trevogu.(2020,September1) [Air quality in Central Asia needs to be sounded the alarm]. https://livingasia.online/2020/09/01/.(in Russin).

- Salnikov,V.,Polyakova,S.,Ullman,A.,Kauazov,A.,Tursumbayeva,M.,Kisebayev,D.,Miskiv,D.,Beldeubayev,E.,MusralinovaG., Kozhagulov,S. (2024).Monitoring kachestva atmosphernogo vozduha Zapadno-Kazakhstanskogo regiona:printsypy, metody,podhody. [Monitoring the quality of atmospheric air in the West Kazakhstan region: principles, methods, approaches]. Hydrometeorology and Ecology. [CrossRef]

- Hughes,G.(Ed.). (2017). Central Asia Waste Management outlook. Zoï Environment Network: UNEP,Nairobi, Kenya, pp.100. ISBN: 978-92-807-3666-3.

- Yang, W. , Wang, J., Zhang, K.,Hao, Y. (2023). A novel air pollution forecasting, health effects, and economic cost assessment system for environmental management: From a new perspective of the district-level. J. Clean. Prod. [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 |

| Variable | Evaluation of the coefficient | Standard error | t-statistics | p-value | Significance |

| Intercept (Constant) | -272.71 | 0.0073 | -37348.08 | < 2.2e-16 | *** (very significant) |

| Energy_Consumption | 3.124 | 0.0006 | 4827.32 | < 2.2e-16 | *** (very significant) |

| GDP | -0.0326 | 0.00012 | -267.65 | < 2.2e-16 | *** (very significant) |

| Coal Consumption | 0.1467 | 0.00038 | 384.13 | < 2.2e-16 | *** (very significant) |

| Carbon_Factor | 85.243 | 0.0131 | 6478.36 | < 2.2e-16 | *** (very significant) |

| Indicator | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | Kazakhstan (2023) |

| Energy_Consumption | 1.50% | 1.20% | 1.00% | 0.80% | 0.70% | 0.50% | 0.30% | 88.0 |

| GDP | 3.00% | 3.20% | 3.50% | 3.30% | 3.10% | 3.00% | 2.80% | 262.4 |

| Coal Consumption | -1.00% | -1.50% | -2.00% | -2.50% | -3.00% | -3.50% | -4.00% | 74.0 |

| Carbon_Factor | -0.50% | -1.00% | -1.20% | -1.50% | -1.80% | -2.00% | -2.50% | 3.23 |

| Гoд | Энергoпoт-ребление | ВВП | Пoтребление угля | Углерoдoемкoсть | Расчет прoгнoзных выбрoсoв CO₂, млн.т |

| 2024 | 88.0×1.015= 89.32 | 262.4×1.03= 270.272 | 74.0×0.99= 73.267 | 3.23×0.995=3.214 | −272.71+(3.124×89.32)−(0.0326×270.272)+ (0.1467×73.267)+(85.243×3.214)= 282.23 |

| 2025 | 89.32×1.012=90.392 | 270.272×1.032=278.921 | 73.26×0.985=72.177 | 3.214×0.99=3.182 | −272.71+(3.124×90.392)−(0.0326×278.921)+(0.1467×72.177)+(85.243×3.182)= 282.41 |

| 2026 | 90.392×1.01=91.296 | 278.921×1.035=288.683 | 72.17×0.98= 70.737 | 3.182×0.988=3.144 | −272.71+(3.124×91.296)−(0.0326×288.683)+(0.1467×70.73)+(85.243×3.144)= 281.47 |

| 2027 | 91.30 × 1.008 = 92.03 | 288.68 × 1.033 = 298.23 | 70.73 × 0.975 = 68.94 | 3.144 × 0.985 =3.097 | −272.71+(3.124×92.03)−(0.0326×298.23)+(0.1467× 68.94)+(85.243×3.097)=280.25 |

| 2028 | 92.03 × 1.007 = 92.68 | 298.23 × 1.031 = 307.48 | 68.94 × 0.97 = 66.87 | 3.097 × 0.982 =3.048 | −272.71+(3.124×92.68)−(0.0326×307.48)+(0.1467× 66.87)+(85.243×3.048)=278.93 |

| 2029 | 92.68 × 1.005 = 93.14 | 307.48 × 1.030 = 316.70 | 66.87 × 0.965 = 64.50 | 3.048 × 0.980 =2.987 | −272.71+(3.124×93.14)−(0.0326×316.7)+(0.1467× 64.5)+(85.243×2.987)=277.55 |

| 2030 | 93.14 × 1.003 = 93.42 | 316.70 × 1.028 = 325.59 | 64.50 × 0.96 = 61.92 | 2.987 × 0.975 =2.913 | −272.71+(3.124×93.42)−(0.0326×325.59)+(0.1467× 61.92)+(85.243×2.913)=275.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).