Submitted:

04 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

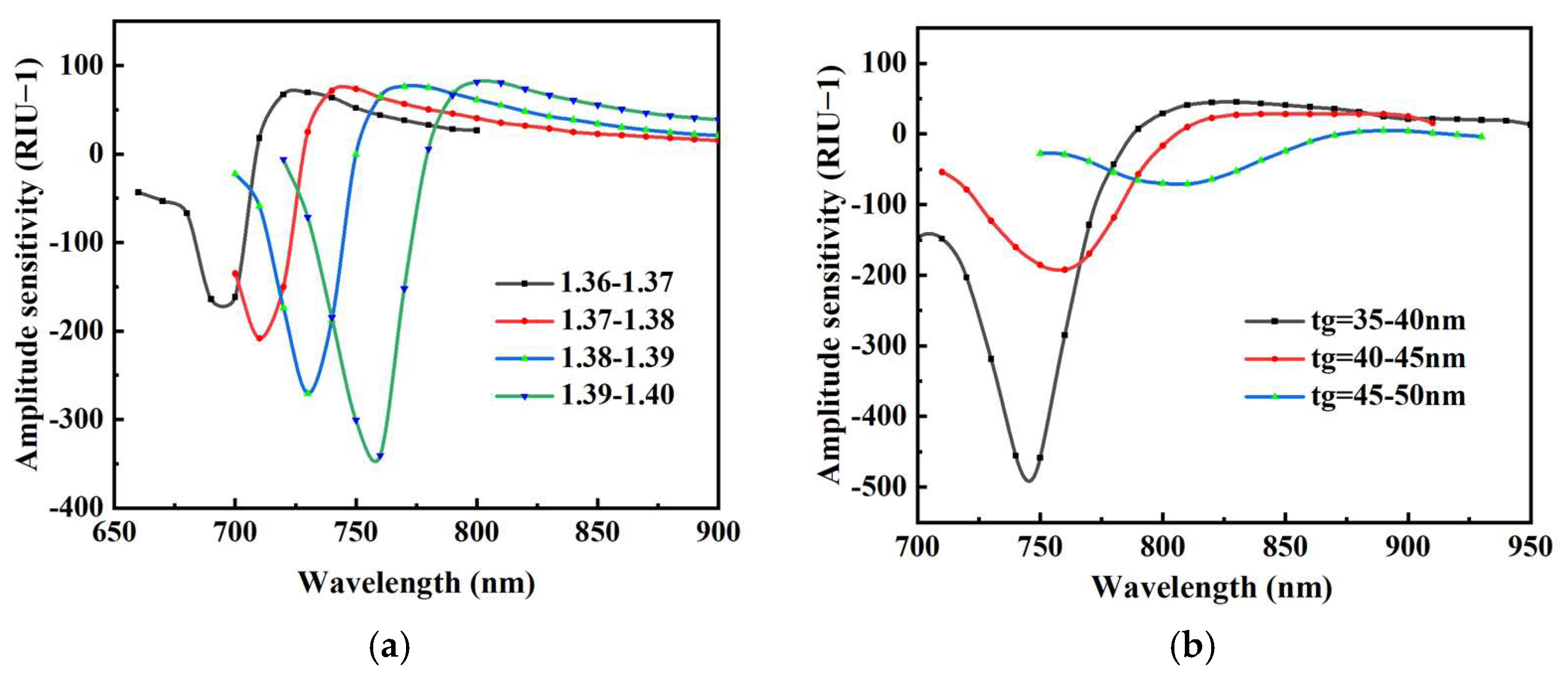

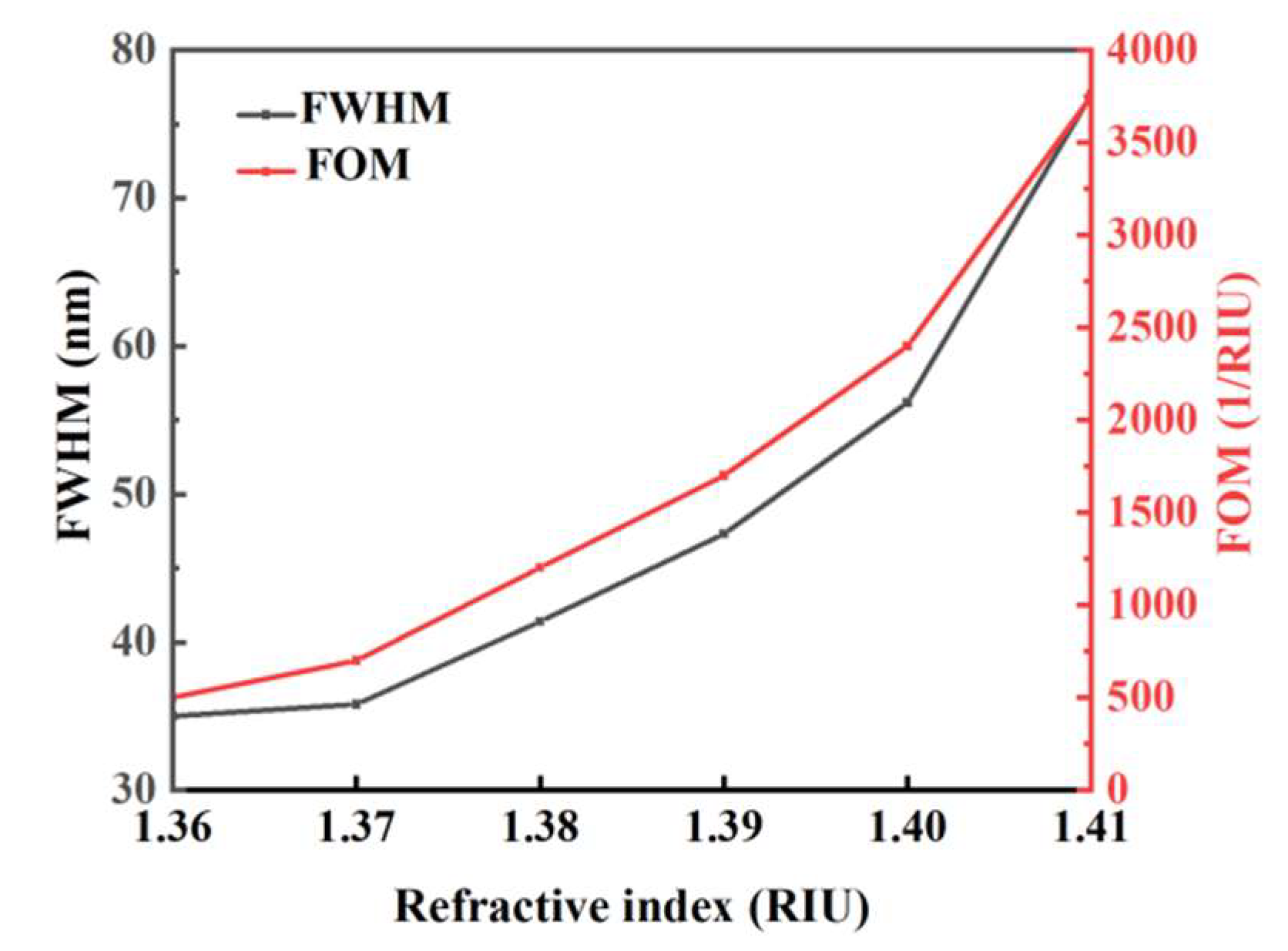

A symmetric three-core photonic crystal fiber optic sensor based on a gold film is presented, aiming to accurately measure the refractive index and evaluate its sensing characteristics. This sensor adopts the design of covering a gold film on a photonic crystal fiber, in which the fiber contains air holes of three different diameters. The performance of the sensor was analyzed by numerical simulation through the full vector finite element method. The results show that the sensor performance can be significantly affected by adjusting the diameter of the air holes and the thickness of the gold film. The sensor performs particularly well when the refractive index (RI) of the substance to be measured is in the range of 1.36 to 1.41, especially when the RI is 1.41. It has a maximum limiting loss value of 75 dB cm-1, a maximum amplitude sensitivity of 421 nm RIU-1, and a finest resolution of 6.67 × 10-6 RIU.These characteristics are essential for scientific research and industrial use where a high degree of accuracy is sought. This study not only provides a novel perspective on the design of three-core photonic crystal fibers, but also lays a solid foundation for the future development and optimization of fiber optic sensor technology. This innovation using gold films may inspire the development of more high-performance sensors and further expand the application areas of photonic crystal fiber technology. As the performance of sensors continues to improve, the prospects for commercialization of related technologies will become brighter. High-performance sensors are expected to be widely used in emerging industries such as smart manufacturing, automated monitoring systems and the Internet of Things, giving a strong boost to the development of these fields. The use of gold films demonstrates the possibility of applying new materials in fiber-optic sensors, and other types of metals or composites may be explored in the future to achieve even higher performance enhancements. With the advancement of sensor technology, they will be more widely used in a number of fields, contributing to the technological innovation and growth of related industries.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

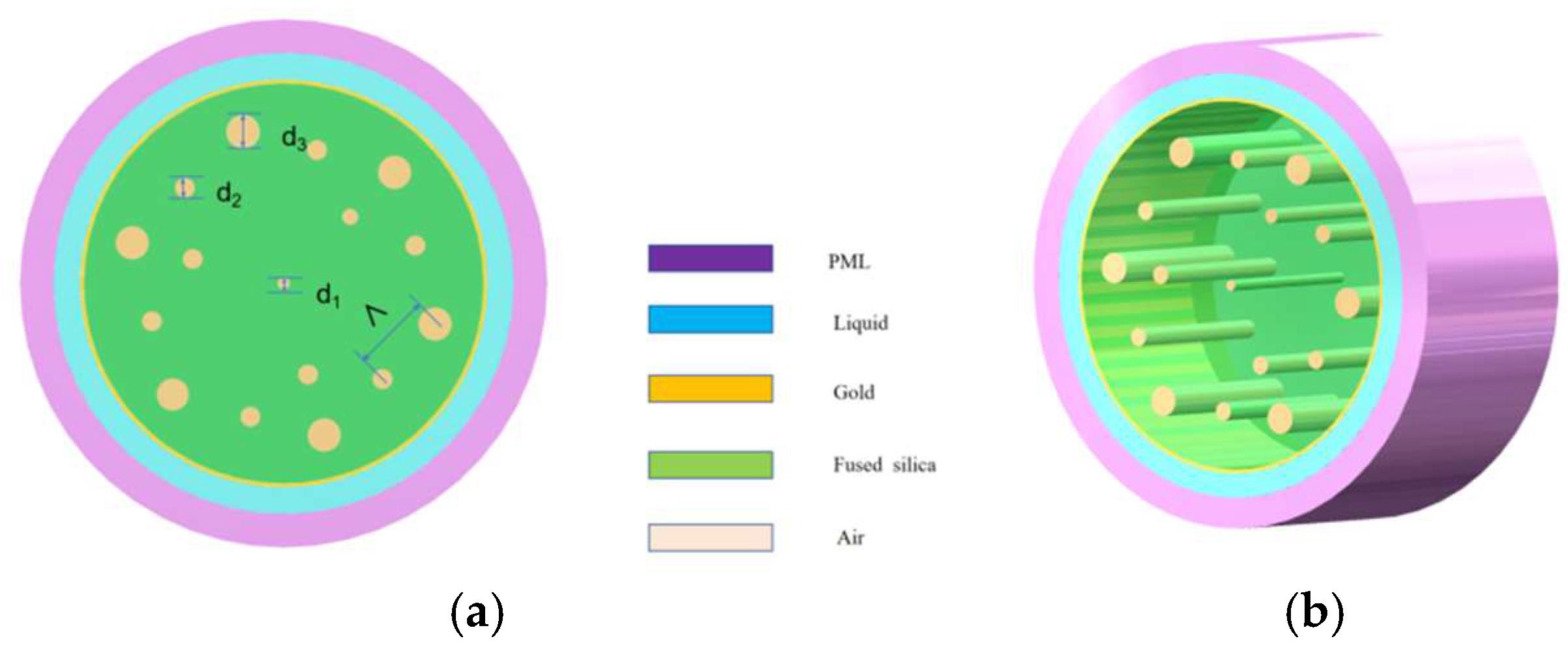

2. Structural Design and Theoretical Model

2.1. Internal Structure Overview

2.2. Material Selection and Theoretical Basis

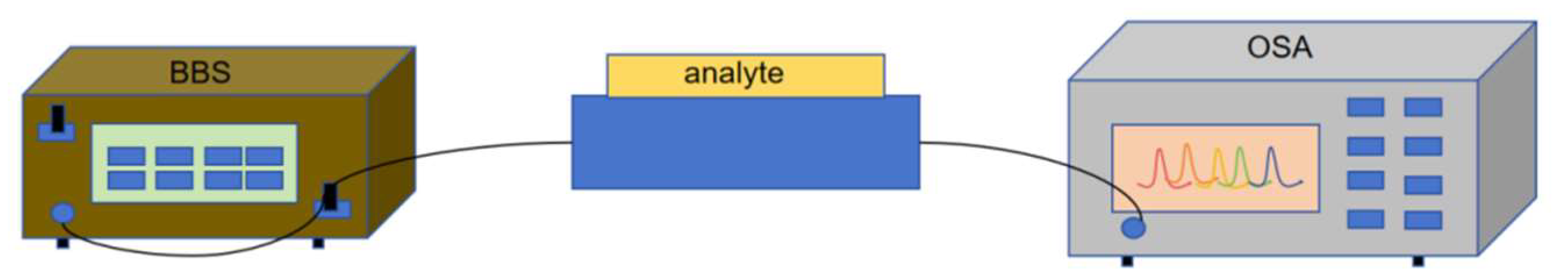

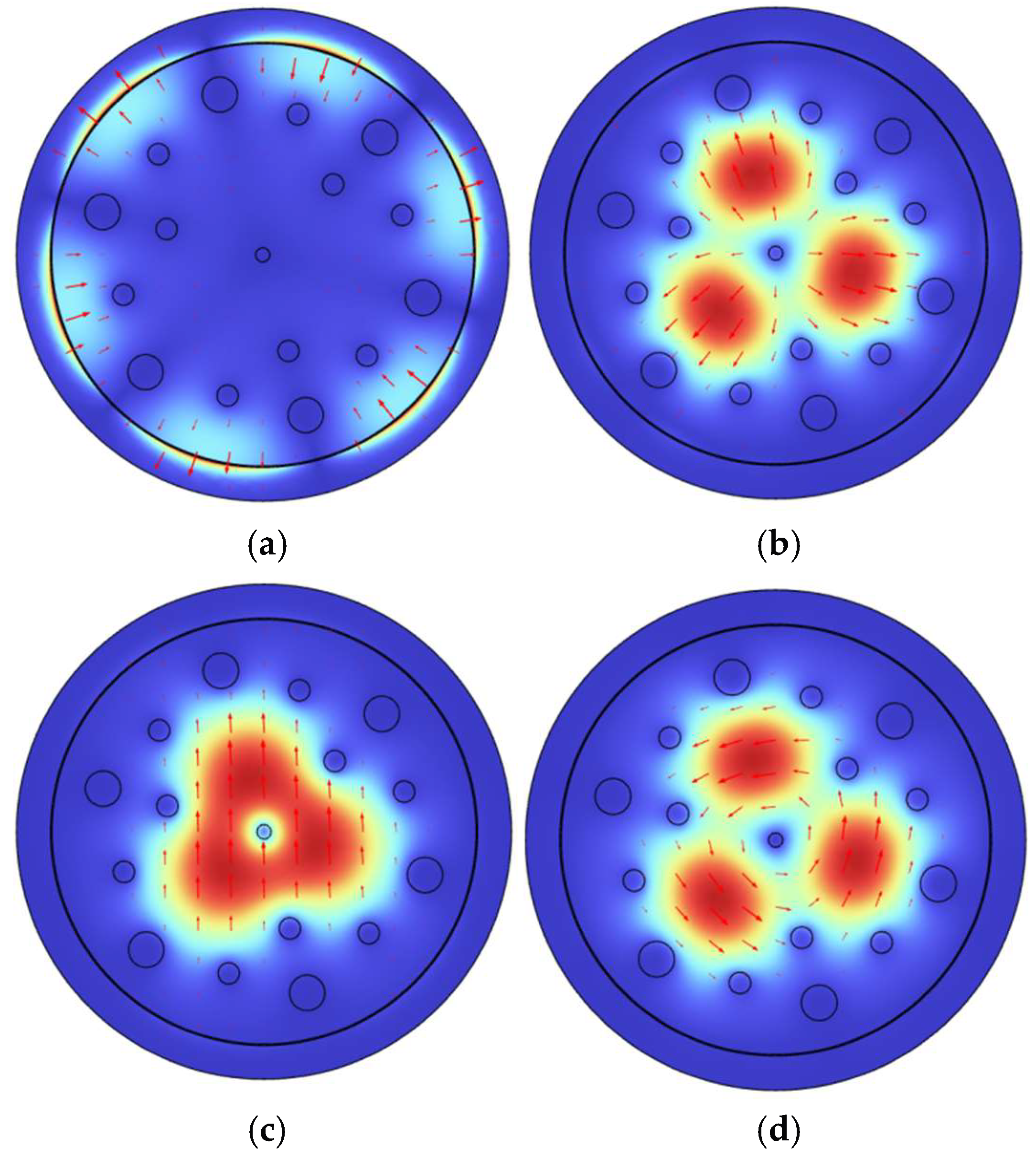

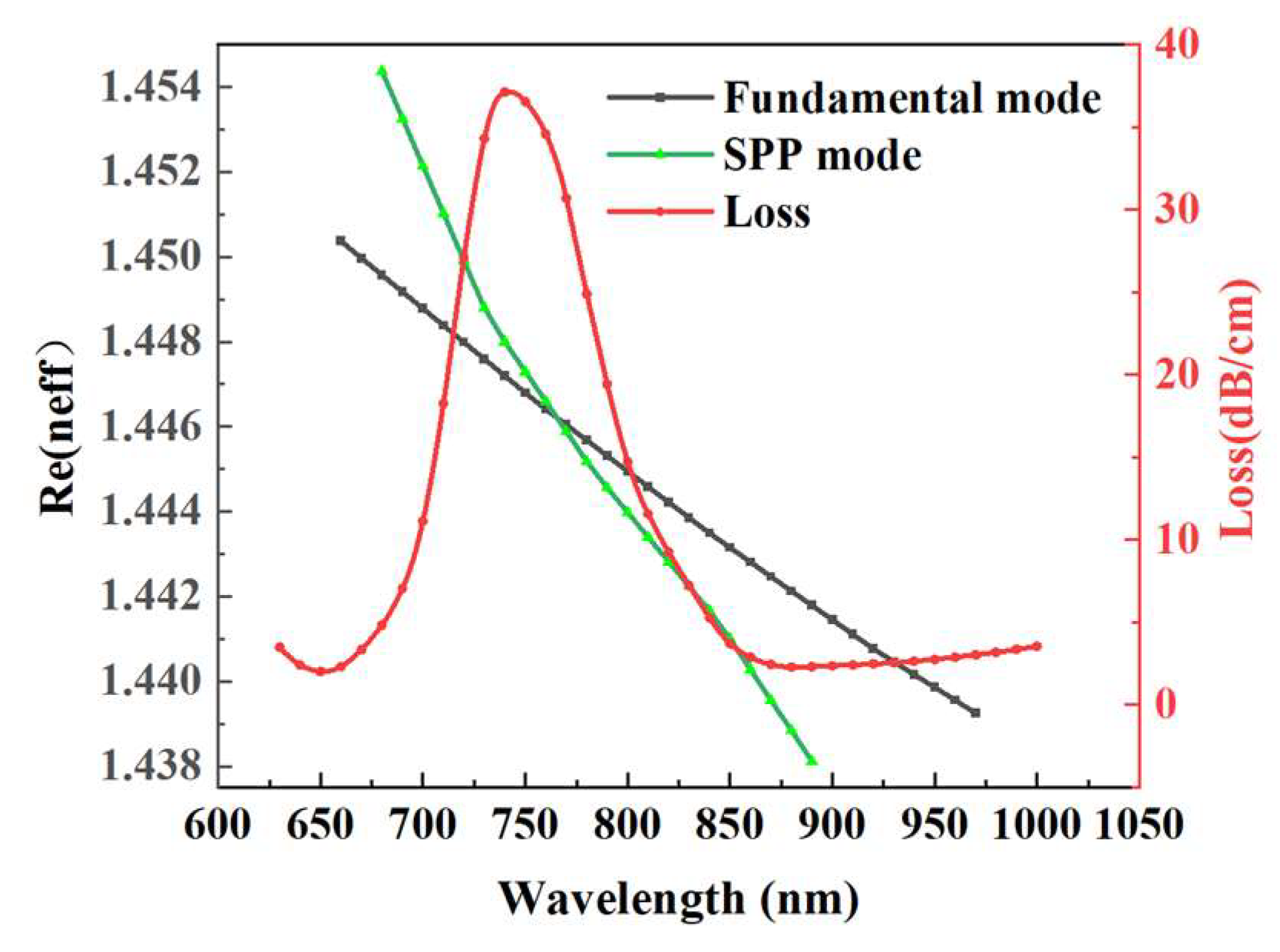

3. Simulation Results and Discussion

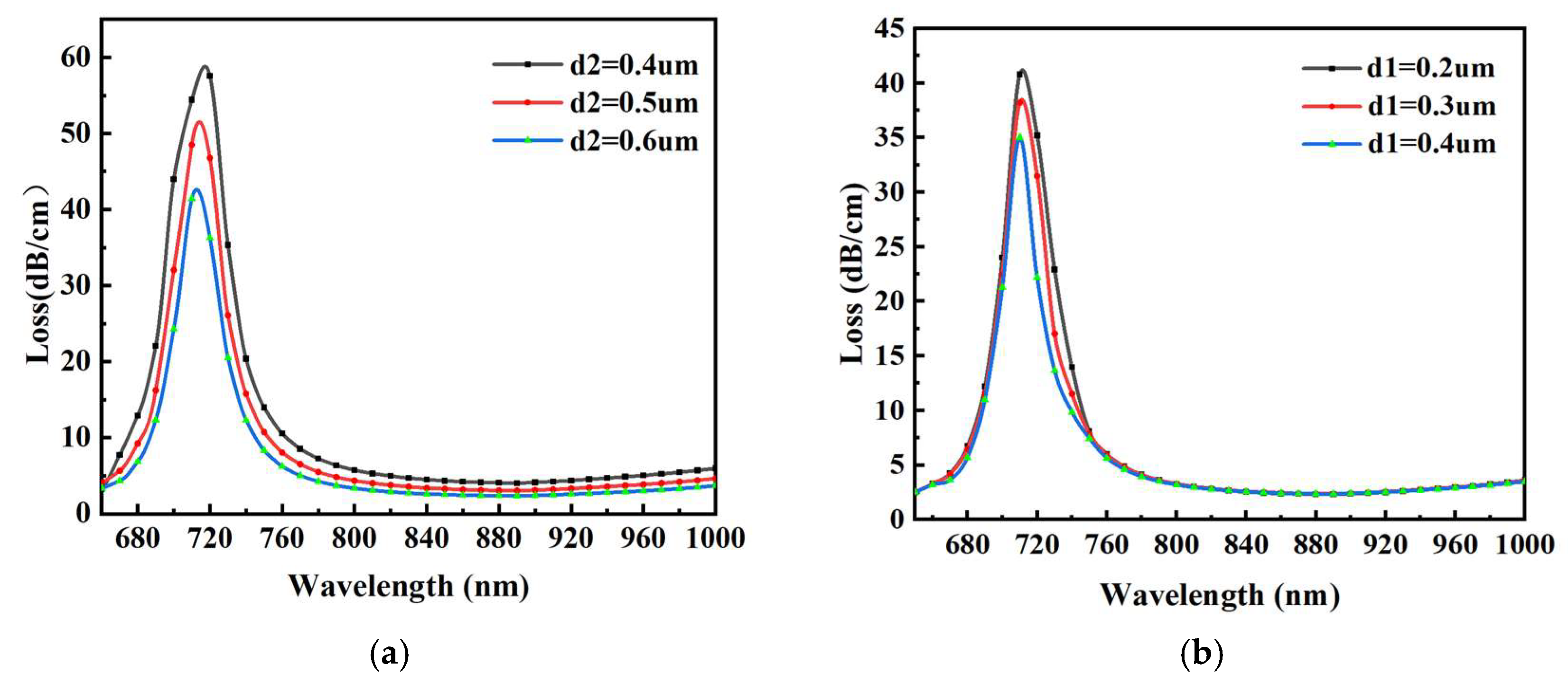

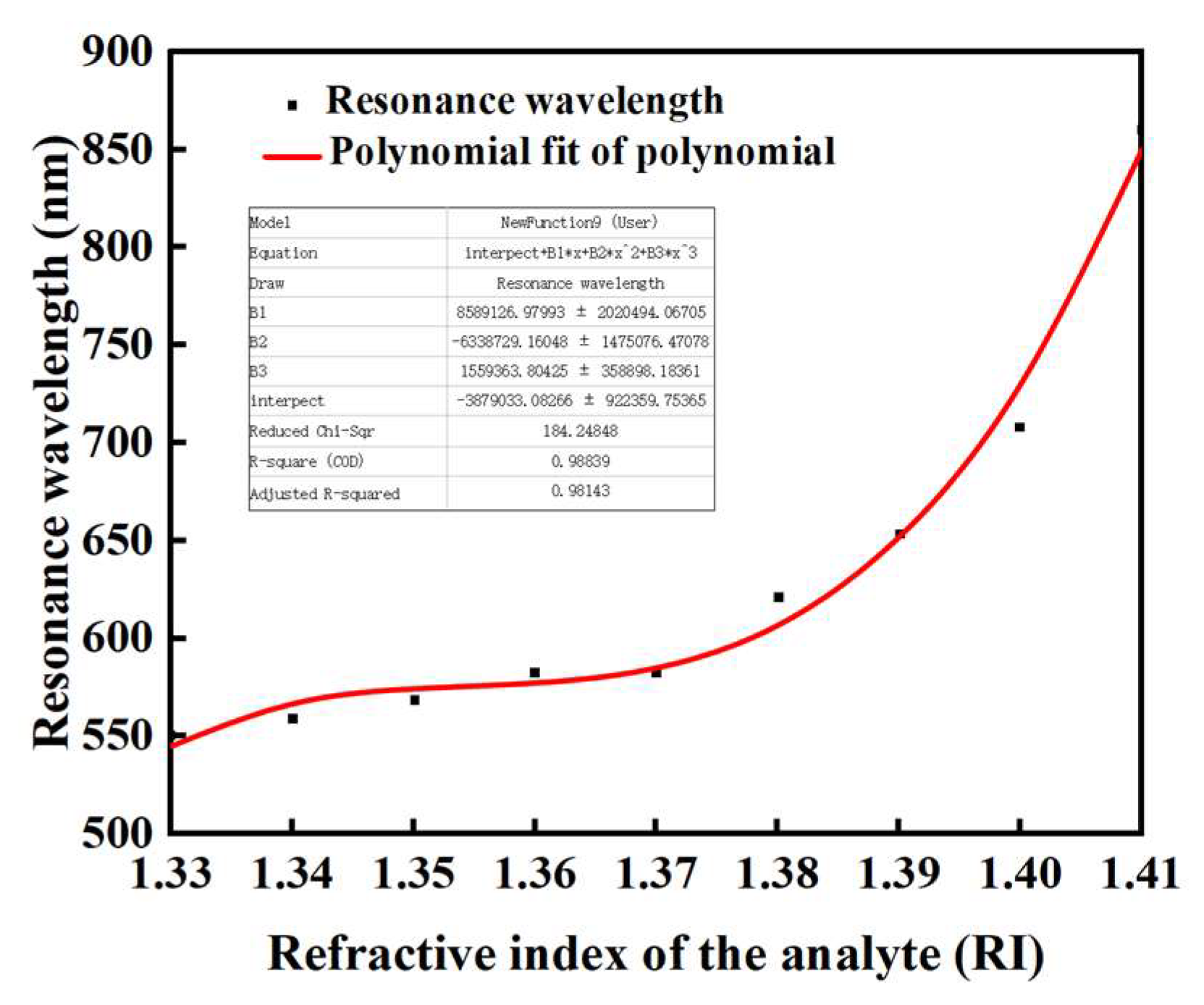

3.1. Structural Optimization

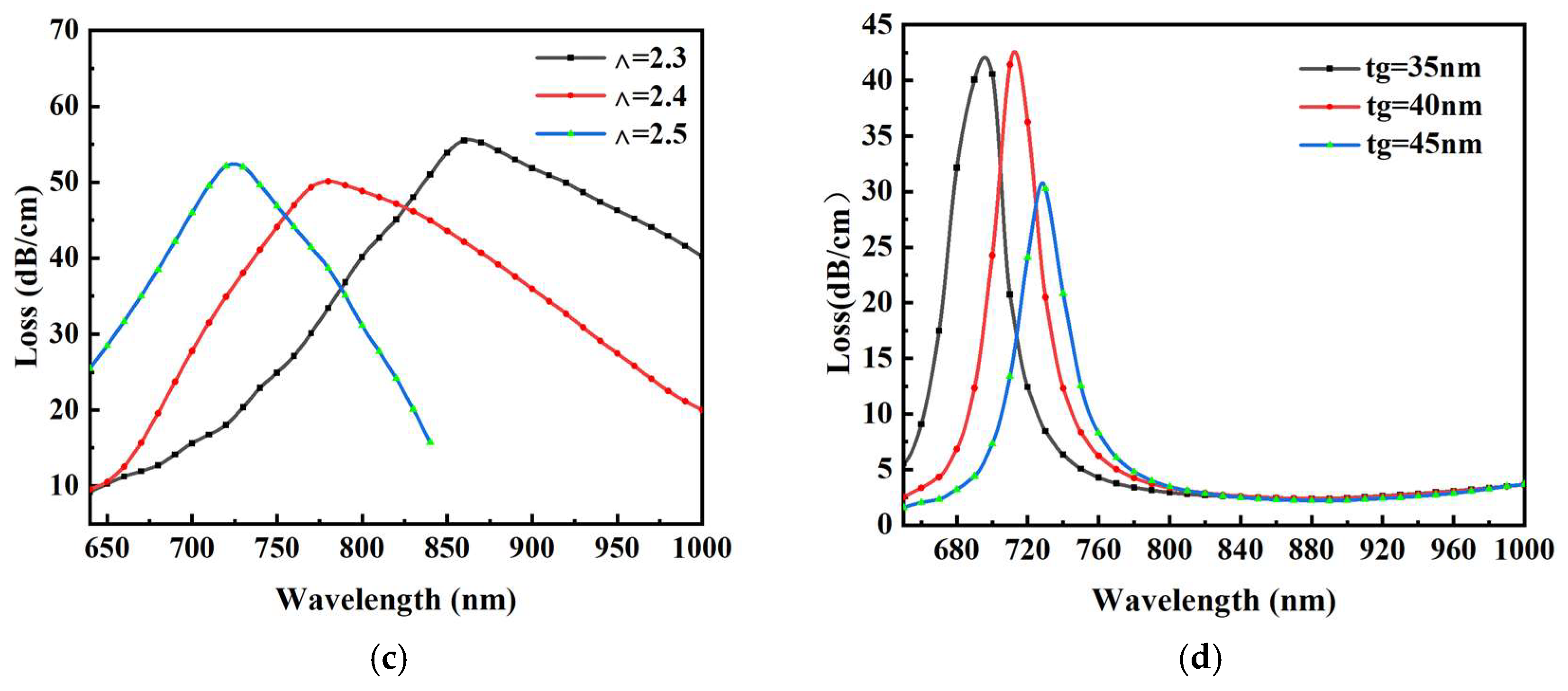

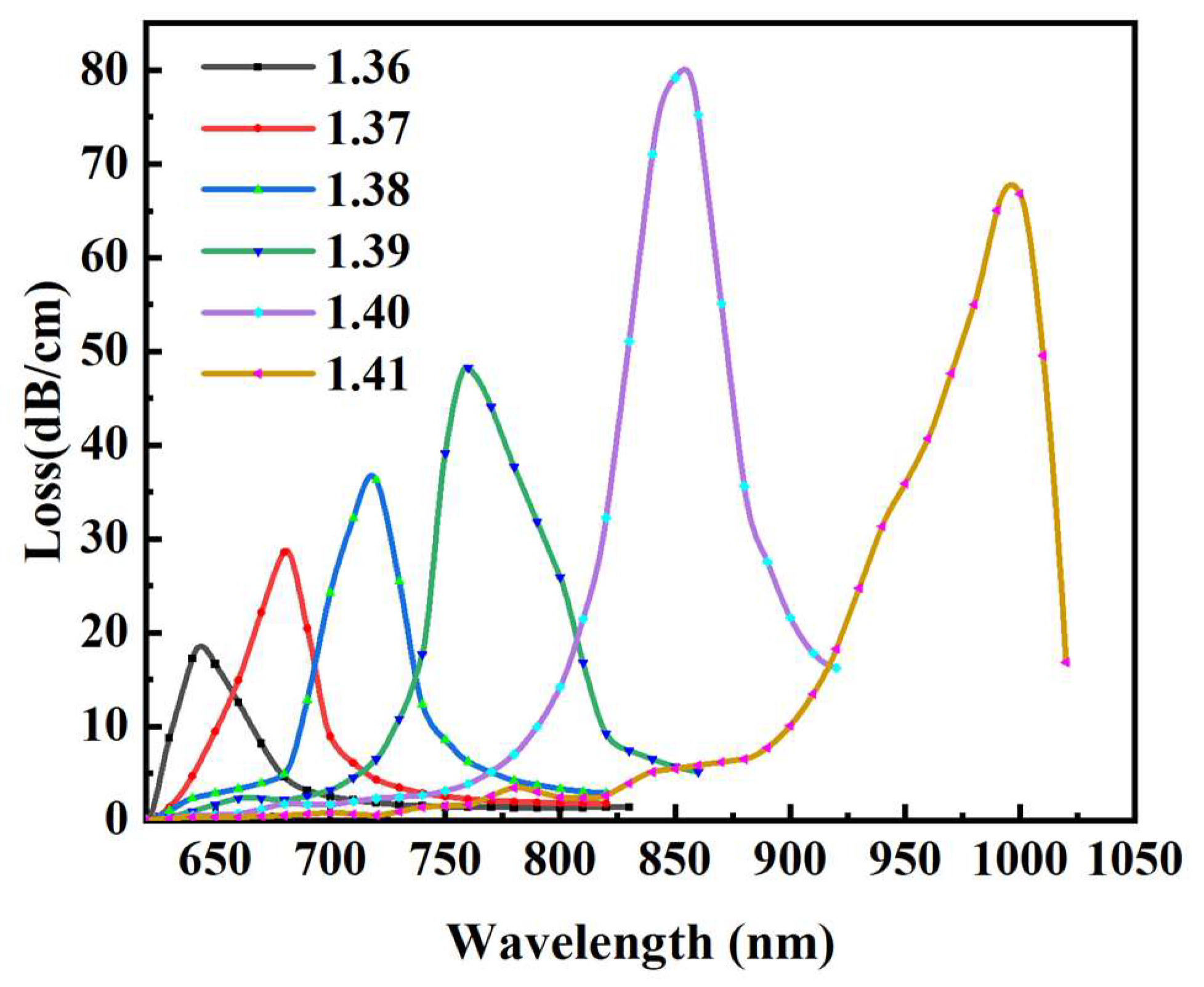

3.2. Device Performance Analysis

4. Conclusion

Funding

References

- Youpeng Y ,Yafei Q ,Xinyu L , et al.High-sensitivity three-core photonicic crystal fiber sensor based on surface plasmon resonance with gold film coatings[J].Japanese Journal of Applied Physics,2021,60(12). [CrossRef]

- Tong K ,Wang F ,Wang M , et al.Three-core photonicic crystal fiber surface plasmon resonance sensor[J].Optical Fiber Technology,2018,46306-310. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Z ,Caner C ,Chuanyang H , et al.Wide refractive index detection range sensors based on D-shape photonicic crystal fiber with a nanoscale gold wire[J].Optik,2023,292. [CrossRef]

- Jiao ,Shengxi,Li , et al.Research on three-core photonicic crystal fiber plasmonic sensor based on surface plasmon resonance with three V-groove microfluidic channel[J].Optical Review,2022,29(2):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Yuwei Q ,Jinhui Y ,Shi Q , et al.A novel photonicic crystal fiber refractive index sensor with ultra wide detection range based on surface plasmon resonance effect[J].Optik,2022,262. [CrossRef]

- Yanan W ,Guangyu J ,Zijian Y , et al.Trapezium-shaped groove photonicic crystal fiber plasmon sensor for low refractive index detection[J].Sensing and Bio-Sensing Research,2021,34. [CrossRef]

- Xin Y ,Taotao H ,Tonglei C , et al.Refractive index and temperature sensors of V-cut photonicic crystal fibers based on surface plasmon resonance[J].Optik,2022,269. [CrossRef]

- Jiao L ,Zhong N ,Zhao X , et al.Recent advances in fiber-optic evanescent wave sensors for monitoring organic and inorganic pollutants in water[J].Trends in Analytical Chemistry,2020,127(prepublish).

- Hemant K ,Raj K ,Umang R , et al.Al-doped ZnO based long range optical fibre sensor for efficient low refractive index detection[J].Optical and Quantum Electronics,2023,55(7). [CrossRef]

- Tian J ,Xu C ,Cui S , et al.A photonicic Crystal Fiber-Based Biosensor with Quasi-D-shaped Layout and ITO-Graphene Combination[J].Plasmonics,2021,16(5):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Yang X ,Yi Y ,Lu W , et al.D-shaped photonicic crystal fiber based on surface plasmon resonance for low refractive index applications[J].Optical Materials,2024,153115612-. [CrossRef]

- Ghahramani S ,Barvestani J ,Meshginqalam B .Design and analysis of surface plasmon resonance based photonicic crystal fiber sensor employing gold nanowires[J].Optik,2022,260. [CrossRef]

- Shafkat A ,Rashed Z N A ,El-Hageen M H , et al.The Effects of Adding Different Adhesive Layers with a Microstructure Fiber Sensor Based on Surface Plasmon Resonance: A Numerical Study[J].Plasmonics,2021,16(3):1-14. [CrossRef]

- Khan H M A ,Riazul S I ,Hriteshwar T , et al.A highly sensitive quadruple D-shaped open channel photonicic crystal fiber plasmonic sensor: A comparative study on materials effect[J].Results in Physics,2021,23. [CrossRef]

- Paul K A ,Habib S M ,Hai H N , et al.An air-core photonicic crystal fiber based plasmonic sensor for highre fractive index sensing[J].Optics Communications,2020,464125556-125556. [CrossRef]

- Hao C ,Zihao C ,Hua Y , et al.Multi-mode surface plasmon resonance absorber based on dart-type single-layer graphene.[J].RSC advances,2022,12(13):7821-7829. [CrossRef]

- Fu Y ,Liu M ,Shum P , et al.An ultrahighly sensitive photonicic crystal fiber based surface plasm resonance sensor[J].Optik,2020,212(prepublish):164649-164649.

- Samiha N ,Faiyaz M H B ,Sanjida S , et al.Hybrid lattice shaped dual polarized highly sensitive surface plasmon resonance based refractive index sensor[J].Optical and Quantum Electronics,2022,54(5). [CrossRef]

- Rakibul M I ,Islam M M K ,Rahbar R A , et al. Trigonal cluster-based ultra-sensitive surface plasmon resonance sensor for multipurpose sensing[J].Sensing and Bio-Sensing Research,2022,(prepublish):100477-.

- Honggang P ,Nan C ,Ailing Z , et al.High sensitivity photonicic crystal fiber surface plasmon resonance sensor based on indium tin oxide[J].Optical and Quantum Electronics,2023,55(8). [CrossRef]

- P. Bing et al., “Analysis of dual-channel simultaneous detection of photonic crystal fiber sensors,” Plasmonics, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 1071–1076, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Ramola, A. Marwaha, and S. Singh, “Design and investigation of a dedicated PCF SPR biosensor for CANCER exposure employing external sensing,” Applied Physics A, vol. 127, no. 9, p. 643, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- U. Ramani et al., “Study of highly sensitivity metal wires assisted photonic crystal fiber based refractive index sensor,” Optical and Quantum Electronics, vol. 52, no. 521, pp. 1-13, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jing W ,Yongxiang H ,Lizao G , et al.Optofluidic refractive index sensor with microtube-coupled suspended core fiber[J/OL].Optoelectronics Letters,1-6[2024-12-30].http://122.51.45.239:8085/kcms/detail/12.1370.TN.20241203.1514.014.html.

| Ref | RI range (RIU) |

Max. AS (RIU-1) |

Max. WS (nm/RIU) |

FOM (RIU-1) |

| [4] | 1.33-1.37 | 160 | 11400 | 250 |

| [21] | 1.33-1.40 | 371 | 11600 | |

| [22] | 1.36-1.401 | 13,240 | 14285.71 | 21.61 |

| [23] | 1.31-1.36 | 597 | 7300 | |

| [24] | 1.33-1.70 | 239.6 | 846.2 | 155.2 |

| This work | 1.36-1.41 | 421 | 15000 | 3750.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).