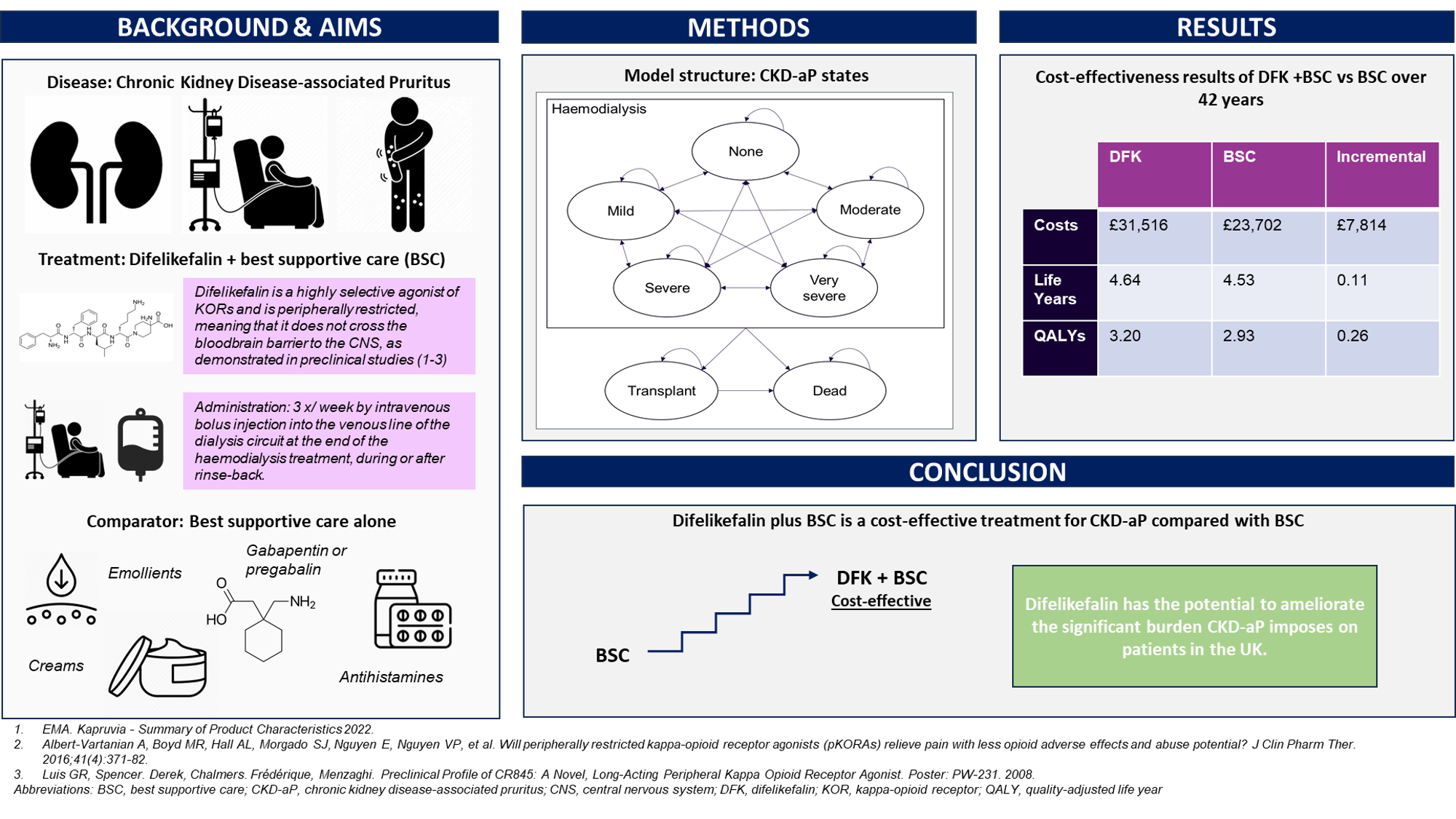

1. Introduction

Disease background: Chronic kidney disease-associated pruritus

CKD-associated pruritus (CKD-aP) is a significant comorbidity that occurs commonly in CKD patients, [

1]. Compared to CKD patients without pruritus, CKD-aP patients have increased rates of diabetes, sleep disturbance, and depression; are more likely to be hospitalised for infections; and have an increased risk of mortality [1-5]. The severity of pruritus, as well as its location on the body, can vary over time in individual patients. In its most severe forms, CKD-aP can lead to a patient being completely restless during both the day and night, significantly reducing their health-related quality of life (HRQoL); this is particularly true when it appears as part of a symptom cluster with other CKD comorbidities [4, 6]. It is thought that by treating one symptom, other symptoms experienced by people with CKD-aP such as emotional and psychological distress, may have the potential to also be alleviated [

4].

An estimated 47% of CKD patients on haemodialysis (HD) in the UK experience moderate-to-severe CKD-aP [5, 7]. Treating clinicians often underestimate the prevalence of pruritus in their patients. One recent study of CKD-aP patients in 21 countries found that 17% of those who were ‘always’ or ‘nearly always’ bothered by pruritus had not reported their symptoms to a healthcare professional [

1].

Despite the clear burden of CKD-aP, the disease has a lack of evidence-based treatments. Difelikefalin is the first and only approved drug for this condition currently. Best supportive care (BSC) may include creams and emollients, and off-label use of antihistamines, gabapentin and pregabalin. However, these therapies are supported by limited and low-grade clinical evidence and are prescribed heterogeneously.

Difelikefalin and KALM trials

Difelikefalin (Kapruvia ®) is an agonist of kappa-opioid receptors (KORs). Opioid receptors play a role in regulating itch signals; KORs specifically are known to reduce itch. As such, by activating KORs on peripheral sensory neurons and immune cells, difelikefalin can help to reduce pruritus and the associated inflammation. Difelikefalin is peripherally restricted, meaning its effect is limited to KORs outside the brain or spinal cord [8-10].

The pivotal studies, KALM-1 and KALM-2 (NCT03422653, NCT03636269), represent the largest clinical development programme assessing a treatment for CKD-aP worldwide [11, 12]. These trials were multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of difelikefalin treatment at a dose of 0.5 mcg/kg for reducing itch intensity in patients with moderate-to-severe CKD-aP. Difelikefalin was administered after each HD session (3 times a week). Each trial included a double-blind phase and an open-label extension (OLE) phase.

Following assessments and the publication of guidance from the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) on 17 May 2023 and the Scottish Medicines Consortium on 12 February 2024, difelikefalin is now recommended as a treatment option for moderate-to-severe CKD-aP throughout the UK [13, 14].

Aims

Cost-effectiveness analysis is a key component in the effective and equitable allocation of healthcare resources. This study aimed to describe the conceptualisation and parameterisation of a de novo cost-utility model investigating the cost-effectiveness of difelikefalin plus BSC versus BSC alone when treating moderate-to-severe CKD-aP in patients receiving in-centre haemodialysis (ICHD), from the perspective of the UK NHS.

2. Materials and Methods

Patient population

The target patient population for cost-effectiveness analysis was adult patients receiving chronic ICHD in the UK NHS, and experiencing moderate, severe, or very severe CKD-aP based on the definitions reported by Lai et al., 2017 [

15]. This population is aligned with the licensed indication for difelikefalin, and is henceforth referred to as ‘moderate-to-severe’.

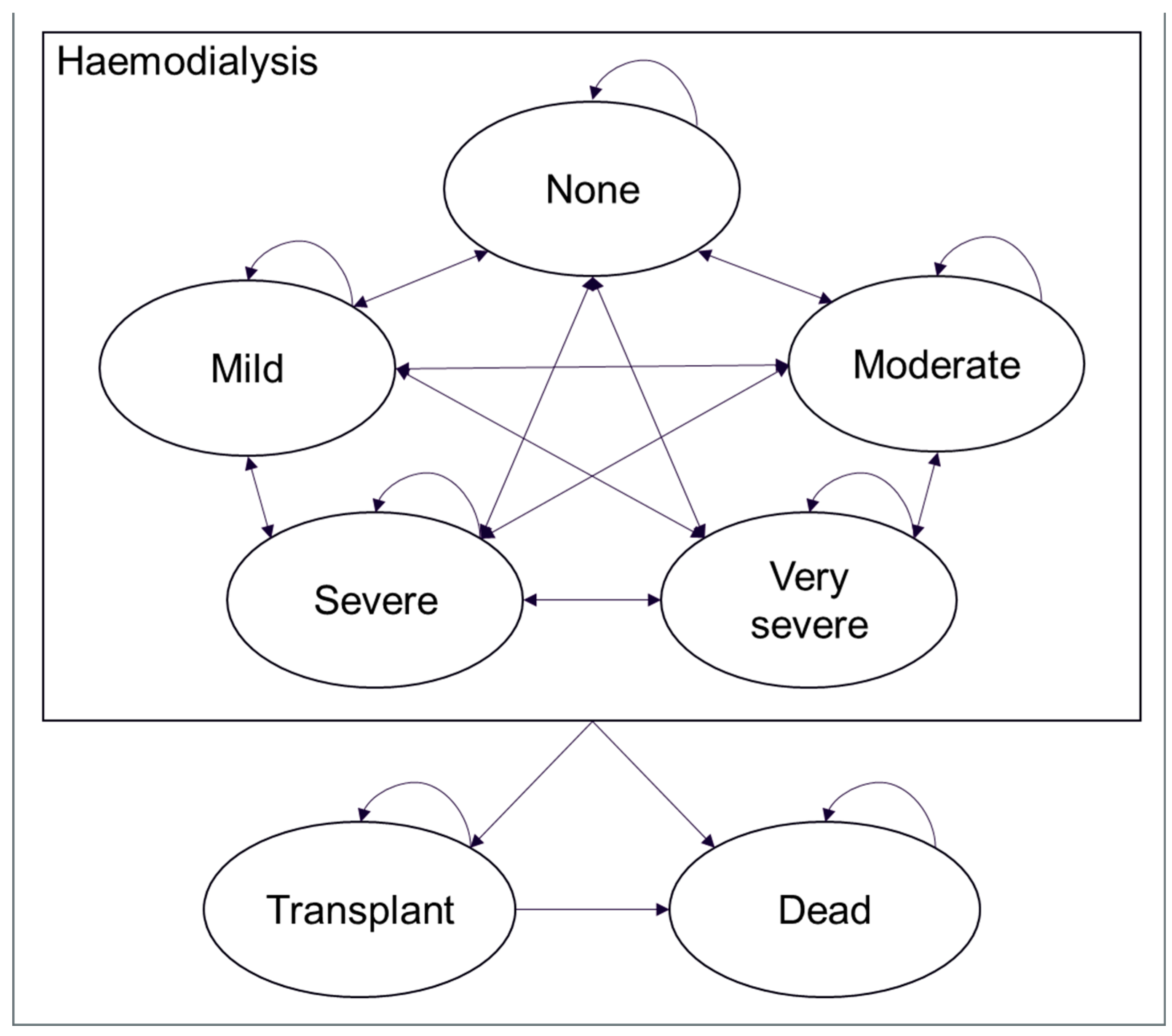

Model structure

A Markov model was developed including a set of disease states to represent the population of interest over time, with patients allowed to reside in only one of these disease states at any point. The model also defines the ways in which patients transition between the disease states and the probabilities of these transitions occurring during each time period.

The model incorporated five core health states defined by level of pruritus severity: none, mild, moderate, severe, and very severe, as defined by Lai et al., 2017 [

15] based on scores from the 5-D Itch scale (categorised as follows: ≤ 8 for none, 9-11 for mild pruritus, 12-17 for moderate pruritus, 18-21 for severe pruritus and ≥ 22 for very severe pruritus). Patients could only enter the model in the moderate, severe, or very severe health states; they could subsequently transition to ‘mild’ or ‘none’ as a result of treatment. From each state, they could also transition to transplant or death

. Because renal failure is associated with CKD-aP, renal transplants were considered a definitive treatment for CKD-aP [

16].

Figure 1 illustrates the model structure and the possible transitions between health states at each cycle.

The model reflected UK clinical practice for CKD-aP at the time it was developed. It included an initial ‘run-in’ period reflecting short-term treatment decisions and patients’ immediate response to this treatment based on the results of KALM-1 and KALM-2, followed by long-term extrapolation based on the OLE phases of the trials. Patients responding to treatment with difelikefalin in the first 12 weeks could remain on treatment until transplant or death, and non-responders were assumed to discontinue difelikefalin and remain on BSC alone. Following the initial ‘run-in’ period of three 4-week cycles, the model used 52-week cycles over a lifetime time horizon. Costs and benefits were discounted at a rate of 3.5% per annum, in line with the NICE methods guide [

17].

Efficacy

The model estimated treatment efficacy using anonymised and pooled patient-level data from KALM-1 and KALM-2.

The main efficacy driver in the model was total 5-D Itch scale score, a questionnaire assessing five dimensions of itch which has been validated in patients with chronic pruritus, including those on HD, and is sensitive to changes in pruritus over time. This, alongside WI-NRS, and Skindex-10, was one of three measures used to assess itch severity and itch-related HRQoL in the KALM-1 and KALM-2 trials. It was selected for use based on the results of a separate primary data collection study [

18] which developed an algorithm mapping WI-NRS and the 5-D Itch scale to EQ-5D-3L. In this analysis, mapping models including 5-D Itch performed better in terms of model fit and predictions than models including a single WI-NRS measure.

In the base case, per-cycle probabilities of losing or gaining health states estimated using the mean change from baseline in total 5-D Itch scale scores, stratified by CKD-aP severity at baseline, were used to derive transition matrices. This approach aligns with the endpoints of KALM-1 and KALM-2, in which changes in itch were measured from baseline to the end of week 12.

Clinical opinion was sought on the natural progression of CKD-aP, specifically, the expected mean change in itch score during the extrapolation period of the model for patients receiving placebo and difelikefalin, in the form of a modified Delphi panel with eight advisors from England and later on in an advisory board with four advisors from Scotland [

19]. The advisors expected the placebo effect would wane over time, in line with the natural progression of CKD-aP, and that difelikefalin would show no treatment waning effect. Additionally, a review of atopic dermatitis NICE technology appraisals was conducted to provide estimates on the long-term benefit of BSC treatments for pruritus; all three appraisals identified had used the same scenario, in which all clinical benefit for patients receiving BSC was lost by the end of year 5.

As such, a waning effect was applied independently to each of the five core health states for the BSC treatment arm, which more conservatively assumed that patients returned to their baseline health state distribution by year 10.

Mortality and transplant rates

The NICE guideline for renal replacement therapy (RRT) and conservative management, NG107, presents estimates for annual probabilities of death and transplant for people on HD, up to 10 years after their first dialysis session; all subsequent years are assumed to have identical probabilities of death as year 10. This is done as part of a cost-effectiveness analysis comparing hemodiafiltration (HDF) to high flux HD [

20]. The probabilities are based on an analysis of data from the UK Renal Registry (UKRR) from a cohort of UK adults who started RRT through HD between 2005 and 2014, Annual mortality rates of patients on HD from 2015 and 2019 were similar to those presented by the UKRR, indicating their analysis is still generalisable to present-day HD populations. The base case of this model therefore used the methods presented in NG107 to derive mortality and transplant rates. Please see

Table 6B in ‘supplementary materials’ for further information.

Patients who received a transplant were assumed to follow rates of age-adjusted all-cause mortality found in UK life tables. The probability of age-dependent mortality was estimated based on the distribution of males and females in the KALM clinical trials.

Sukul et al., 2021 [

5] used a Cox regression to compare all-cause mortality rates for CKD-aP patients with pruritus to patients who did not report pruritus. Their results showed CKD-aP to be an independent predictor of patient mortality. The base case analysis of this model uses the hazard ratios found in their analysis – 1.24, 1.02, and 1.11, respectively, for patients extremely, very much, and moderately bothered by pruritus – to apply an increased mortality risk for the very severe, severe, and moderate CKD-aP population [

5].

Health-related quality of life

Health state utilities for the five core health states were informed by the SHAREHD trial, a UK randomised study in patients receiving ICHD [

21]. Lee et al., 2005, a study of HRQoL in patients with kidney failure with transplants compared to those without transplants, was used to inform utility values for kidney transplant [

22]. The scores derived for each health state are displayed in

Table 1.

Healthcare costs and health-related quality of life

Difelikefalin is administered following HD treatment using an intravenous bolus injection, at a recommended dose of 0.5 micrograms/kg dry body weight [

10]. Vials are used only once; as such, the model rounded the number of vials required to account for unused fill volume.

The model used UKKR data on the number of ICHD sessions undertaken by CKD-aP patients to derive an estimate of the number of dialysis sessions per patient per week. Because the UKKR estimates only showed the number of patients undertaking ICHD less than three times per week, three times per week exactly, and more than three times per week, it was assumed that who had less than three sessions per week had two, and those who had more than three sessions per week of four. This gave a weighted frequency of 2.96 dialysis sessions per patient per week. The annual cost of difelikefalin was therefore estimated at £4,915.02 (at £31.90/vial).

Data on background CKD-aP treatment collected in the previously mentioned utility mapping study was used to estimate the average annual cost of BSC, with unit costs, dose, and pack size sourced from BNF [18, 23]. Because the mapping study merged the severe and very severe populations (owing to the small numbers in each group), the base case analysis set the resource use for these two populations to be equal.

The weighted treatment cost for BSC was included in total treatment costs in the difelikefalin arm. The total weighted treatment cost for BSC for ‘moderate’ CKD-aP was found to be lower than that of the ‘mild’ and ‘none’ populations, something which was attributed to lower use of antidepressants in the moderate CKD-aP population. However, because difelikefalin is added to BSC, weighted total treatment costs for moderate CKD-aP were assumed equal to the weighted total treatment costs for mild CKD-aP.

Table 2 provides a summary of the total weighted treatment costs for each health state.

Annual health state costs comprised visits in primary care, hospitalisations, 3-monthly in-person patient reviews with a consultant nephrologist, transplant and post-transplant costs. The base case did not include the cost of dialysis, as the corresponding adjustment in the risk of mortality led to an indirect increase in survival for the difelikefalin treatment arm. Appropriate unit costs were sourced from the National Cost Collection and Personal Social Services Research Unit [24, 25].

In KALM-1 and KALM-2, ≥65% of adverse events (AEs) were mild or moderate in severity [

12]. Because a systematic literature review failed to identify relevant or appropriate costs for these AEs, the base case analysis assumed all AEs to be costed as a single GP appointment (£33.19; PSSRU 2021).

3. Results

Base case analysis

Table 3 summarises the cost-effectiveness results of difelikefalin plus BSC versus BSC alone for the treatment of adults with moderate-to-severe CKD-aP over a lifetime model horizon (42 years). Difelikefalin was estimated to be cost-effective at a willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of £30,000/QALY at a cost of £31.90/vial.

Compared with BSC alone, treatment with difelikefalin plus BSC was associated with an increased life expectancy (0.11 years per person), and an improved

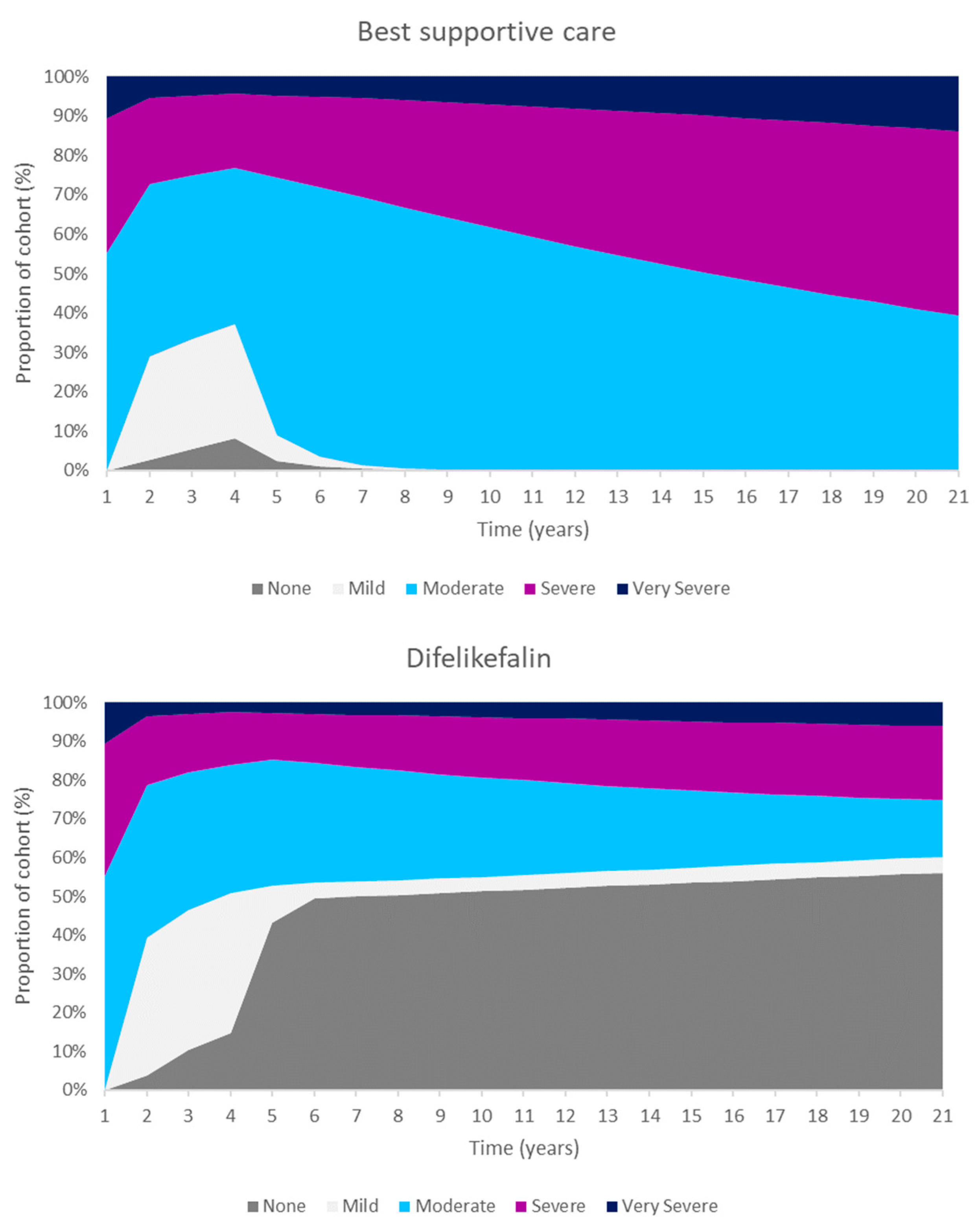

Modelled patients treated with difelikefalin were estimated to have a reduced severity of CKD-aP. Consequently, difelikefalin and BSC was associated with increased life expectancy (0.11 years per person) and improved HRQoL compared with BSC alone, which translated to increased quality adjusted life years (QALYs, 0.26 per person) gained compared with BSC alone. Improved patient outcomes were achieved at an incremental cost of £7,814 per person.

These QALYs were driven by an increased number of people in the less severe CKD-aP states. The Markov traces in

Figure 2 display the distribution of patients across health states for difelikefalin and BSC. Difelikefalin was associated with reduced pruritus severity, which subsequently improved HRQoL and reduce the risk fof mortality; this led to reductions in healthcare resource use and the use of concomitant medications.

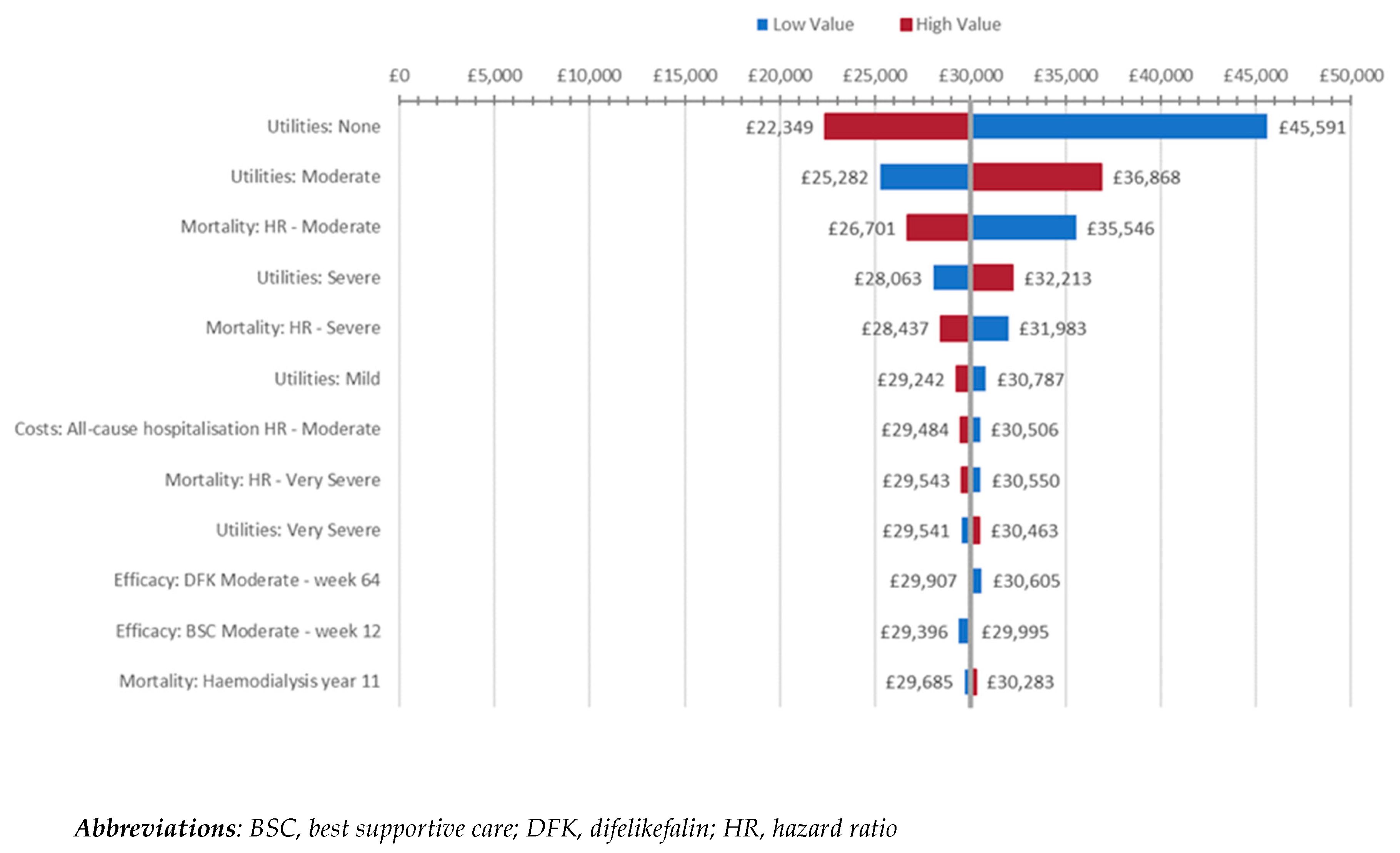

Two sets of analyses were performed to explore the effect of varying individual model inputs on the uncertainty of the model, beginning with deterministic sensitivity analyses (DSAs). Figure 3 presents the most influential model parameters according to these DSAs.

Changes in health state utility values, particularly that of the ‘none’ CKD-aP severity health state, were found to be the factor to which the cost-effectiveness of difelikefalin plus BSC was most sensitive.

Figure 3.

Tornado plot of DSA (impact ≥£1,000/QALY).

Figure 3.

Tornado plot of DSA (impact ≥£1,000/QALY).

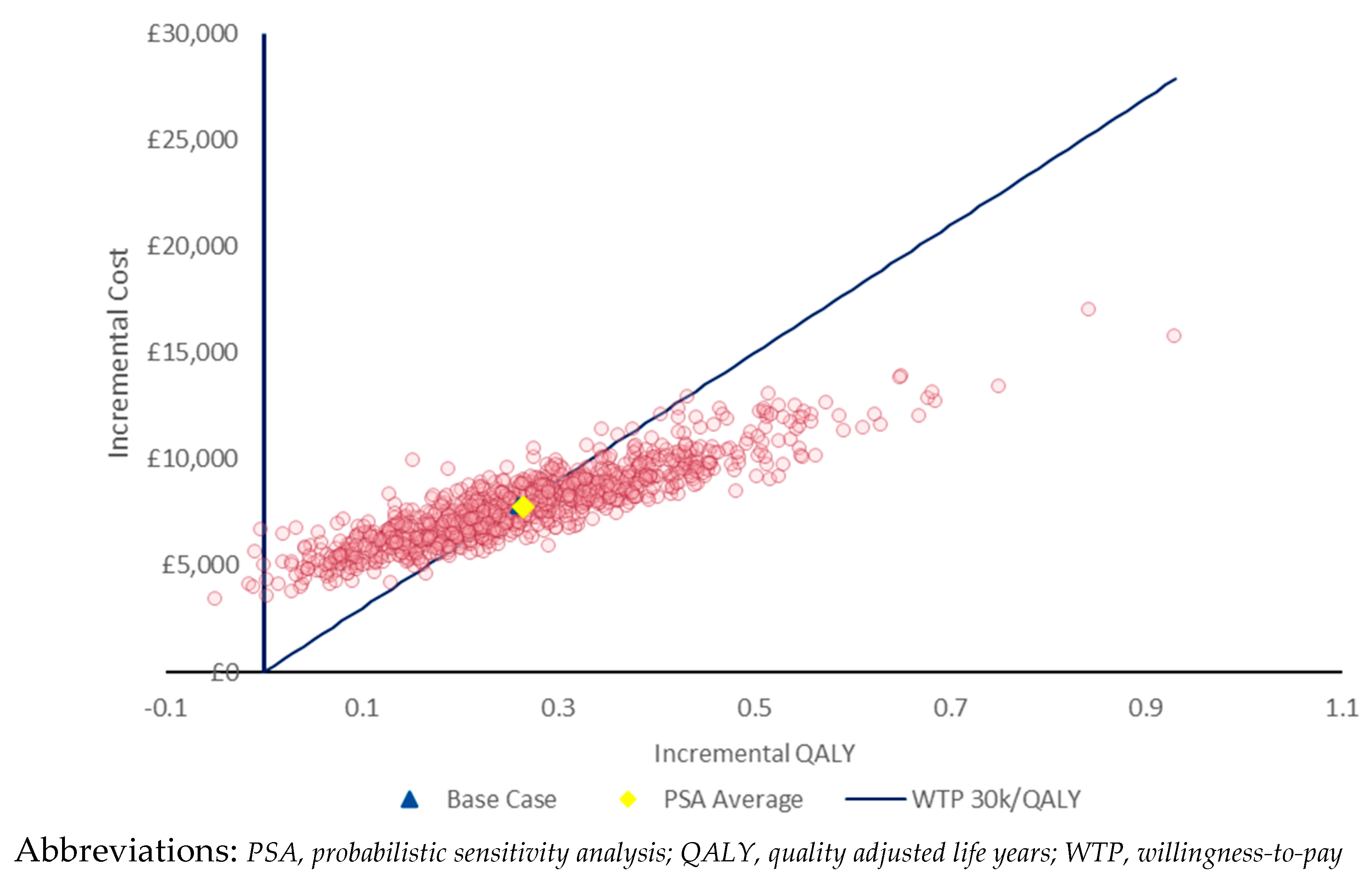

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was also performed; results for 1,000 iterations are presented in

Figure 4. The results of the PSA were consistent with the deterministic results, with incremental per-patient QALYs and costs being 0.26 and £7,805 respectively. Difelikefalin was found to have a 48% probability of being cost-effective at a WTP threshold of £30,000/QALY.

4. Discussion

The aim of this publication is to assess the cost-effectiveness of difelikefalin in addition to BSC versus BSC alone for adults with moderate-to-severe CKD-aP receiving ICHD from a UK payer perspective.

CKD-aP imposes a significant burden on patients' HRQoL and to healthcare systems. CKD-aP, characterised by systemic pruritus, contributes to a myriad of complications, including poor sleep quality, depression, and increased mortality rates. Despite efforts to understand its pathophysiology and develop effective treatments, CKD-aP remains largely underdiagnosed and undertreated. With a lack of robust treatment recommendations and limited approved drugs, patients often rely on off-label interventions and BSC, leading to a high unmet need in this population. Addressing this issue requires greater awareness, research, and access to innovative therapies to alleviate the burden of CKD-aP on patients undergoing haemodialysis.

Moderate-to-severe CKD-aP is associated with a high unmet need, which treatment with difeliekfalin is likely to address. In KALM-1 and KALM-2, difelikefalin was shown to result in statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in both itch severity and itch-related HRQoL compared to placebo over 12 weeks of treatment (5-D Itch scale: 52.1% vs 42.3%; p = 0.01). This improvement was maintained in patients who continued difelikefalin treatment during the OLE period, and emerged in patients who switched to difelikefalin from placebo.

To determine the cost-effectiveness of DFK with BSC versus BSC alone, a Markov model comprising of five health states (from mild to very severe pruritus) was developed. Health state utility values were based on published estimates from the SHAREHD trial. Various UK sources were used to identify costs, and additional model inputs were sourced from published NICE guidance in CKD and atopic dermatitis.

DSA and PSA were used to test the effect of varying model inputs and assumptions on the uncertainty of the model, with both finding the base case cost-effectiveness results to be robust. The use of alternative utility scores derived from analysis of SHAREHD improved the cost-effectiveness of difelikefalin; difelikefalin was also more cost-effective in patients with severe or very severe itch at baseline.

5. Conclusions

In this analysis, difelikefalin was estimated to be a cost-effective treatment for moderate-to-severe CKD-aP at a WTP threshold of £30,000/QALY for costs up to £31.90 per vial. Difelikefalin has the potential to ameliorate the significant burden CKD-aP imposes on both patients and the healthcare system in the UK.

Author Contributions

C.C and I.T facilitated the model build and publication write-up; T.S and G.B provided reviews on the model build; K.M provided clinical opinions as part of a modified Delphi panel with eight UK nephrologists that took place in 2022, testing various modelling assumptions ahead of NICE review. K.M, T.S and G.B critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Funding

This publication has been initiated and funded by Vifor Pharma UK Ltd.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by CSL Vifor. Oliver Darlington, Head of Health Economics and Evidence Synthesis at Initiate Consultancy, was involved in the development of the cost-effectiveness model for difelikefalin and the drafting of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

T.S, G.B are employed by CSL Vifor who funded the project. K.M was provided an honorarium for previous Delphi work but had no financial input for critical assessment of the manuscript. C.C and I.T’s work facilitating the model build and publication write-up was funded by Vifor Pharma UK Ltd.

Appendix A

Table 4A provides a summary of total per-patient disaggregated costs in the base case. Costs were calculated by the cost per year in each health state multiplied by the time spent in that health state.

Table 4A.

Base case disaggregated costs

Table 4A.

Base case disaggregated costs

| |

Difelikefalin + BSC |

BSC |

Incremental |

| Treatment costs (£31.90) |

£7,818 |

£138 |

£7,680 |

| Adverse events |

£17 |

£37 |

-£20 |

| Management costs |

£23,681 |

£23,528 |

£153 |

| None |

£4,585 |

£123 |

£4,463 |

| Mild |

£788 |

£441 |

£347 |

| Moderate |

£3,038 |

£6,246 |

-£3,209 |

| Severe |

£1,552 |

£2,783 |

-£1,231 |

| Very severe |

£384 |

£674 |

-£290 |

| Transplant |

£13,334 |

£13,261 |

£73 |

|

Abbreviations: BSC, best supportive care

|

Table 5A provides the a summary of the QALYs and LYs associated with difelikefalin plus BSC and BSC alone in the base case.

Table 5A.

Base case disaggregated quality adjusted life year and life years

Table 5A.

Base case disaggregated quality adjusted life year and life years

| |

Difelikefalin + BSC |

BSC |

Incremental |

| Life years (total) |

4.64 |

4.53 |

0.11 |

| None |

1.23 |

0.03 |

1.20 |

| Mild |

0.21 |

0.12 |

0.09 |

| Moderate |

0.78 |

1.61 |

-0.82 |

| Severe |

0.38 |

0.68 |

-0.30 |

| Very severe |

0.09 |

0.16 |

-0.07 |

| Transplant |

1.95 |

1.94 |

0.01 |

| QALYs (total) |

3.20 |

2.93 |

0.26 |

| None |

0.92 |

0.02 |

0.89 |

| Mild |

0.15 |

0.09 |

0.07 |

| Moderate |

0.46 |

0.95 |

-0.49 |

| Severe |

0.23 |

0.41 |

-0.18 |

| Very severe |

0.05 |

0.09 |

-0.04 |

| Transplant |

1.39 |

1.38 |

0.01 |

|

Abbreviations: BSC, best supportive care; QALY, quality adjusted life year

|

Mortality and transplant rates in the base case were modelled using the methods presented in NG107 [

20]. The resulting probabilities are summarised below in

Table 6A.

Table 6A.

Probability of death and transplant each year post initiation of HD used in model

Table 6A.

Probability of death and transplant each year post initiation of HD used in model

| Year |

Probability of death |

Probability of transplant |

| 1 |

0.187 |

0.039 |

| 2 |

0.140 |

0.050 |

| 3 |

0.144 |

0.058 |

| 4 |

0.156 |

0.060 |

| 5 |

0.166 |

0.058 |

| 6 |

0.170 |

0.051 |

| 7 |

0.188 |

0.049 |

| 8 |

0.201 |

0.030 |

| 9 |

0.187 |

0.030 |

| 10 |

0.200 |

0.017 |

| 11+ |

0.200 |

0.000 |

References

- Sukul, N. , et al., Pruritus in Hemodialysis Patients: Longitudinal Associations With Clinical and Patient-Reported Outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis, 2023, 82, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Titapiccolo, J.I. , et al., Chronic kidney disease-associated pruritus (CKD-aP) is associated with worse quality of life and increased healthcare utilization among dialysis patients. Qual Life Res, 2023, 32, 2939–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watnick, S. , Peritoneal dialysis challenges and solutions for continuous quality improvement. Perit Dial Int, 2023, 43, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes, C.K.D.W.G. , KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int, 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar]

- Sukul, N. , et al., Self-reported Pruritus and Clinical, Dialysis-Related, and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Hemodialysis Patients. Kidney medicine, 2021, 3(1).

- Mettang, T. and A.E. Kremer, Uremic pruritus. Kidney international, 2015, 87(4).

- Rayner, H.C. , et al., International Comparisons of Prevalence, Awareness, and Treatment of Pruritus in People on Hemodialysis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN, 2017. 12(12).

- Albert-Vartanian, A. , et al., Will peripherally restricted kappa-opioid receptor agonists (pKORAs) relieve pain with less opioid adverse effects and abuse potential? J Clin Pharm Ther, 2016, 41, 371–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, G.R. , Spencer. Derek, Chalmers. Frédérique, Menzaghi, Preclinical Profile of CR845: A Novel, Long-Acting Peripheral Kappa Opioid Receptor Agonist. Poster: PW-231, 2008.

- EMA, Kapruvia - Summary of Product Characteristics 2024.

- Topf, J. , et al., Efficacy of Difelikefalin for the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Pruritus in Hemodialysis Patients: Pooled Analysis of KALM-1 and KALM-2 Phase 3 Studies. Kidney medicine, 2022, 4, 100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbane, S. , et al., Safety and Tolerability of Difelikefalin for the Treatment of Moderate-to-Severe Pruritus in Hemodialysis Patients: Pooled Analysis From the Phase 3 Clinical Trial Program. Kidney Medicine, 2022.

- Consortium, S.M. , Medicine: difelikefalin (brand name: Kapruvia®). 2024.

- NICE, 2023.

- Lai, J.W. , et al., Transformation of 5-D itch scale and numerical rating scale in chronic hemodialysis patients. BMC nephrology, 2017. 18(1).

- Millington, G.W.M. , et al., British Association of Dermatologists' guidelines for the investigation and management of generalized pruritus in adults without an underlying dermatosis, 2018. The British journal of dermatology, 2018. 178(1).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Technology appraisal guidance: Dapagliflozin for treating chronic kidney disease 2022.

- Hernández-Alava, M.S., Alessandro; Fotheringham, James, Developing EQ-5D-3L mapping models in patients on haemodialysis: Comparisons across different pruritus patient reported outcome measures. . Data on file, 2021.

- Vifor, C. , Modified Delphi on the management of CKD-aP in the UK. Data on file, 2022.

- NICE, RRT and conservative management - Cost-effectiveness analysis: HDF versus high flux HD, in Economic Analysis Report 2018.

- Soro, P.T.M. , A METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH TO ASSESS THE ECONOMIC VALUE OF DIFELIKEFALIN TO TREAT CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE ASSOCIATED PRURITUS (CKD-aP). Poster presented at Virtual ISPOR Europe 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.J. , et al., Characterisation and comparison of health-related quality of life for patients with renal failure. Current medical research and opinion, 2005. 21(11).

- NICE, British National Formulary (BNF).

- England, N. , National Cost Collection for the NHS. 2021/2022.

- Unit, P.S.S.R. , 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).