Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

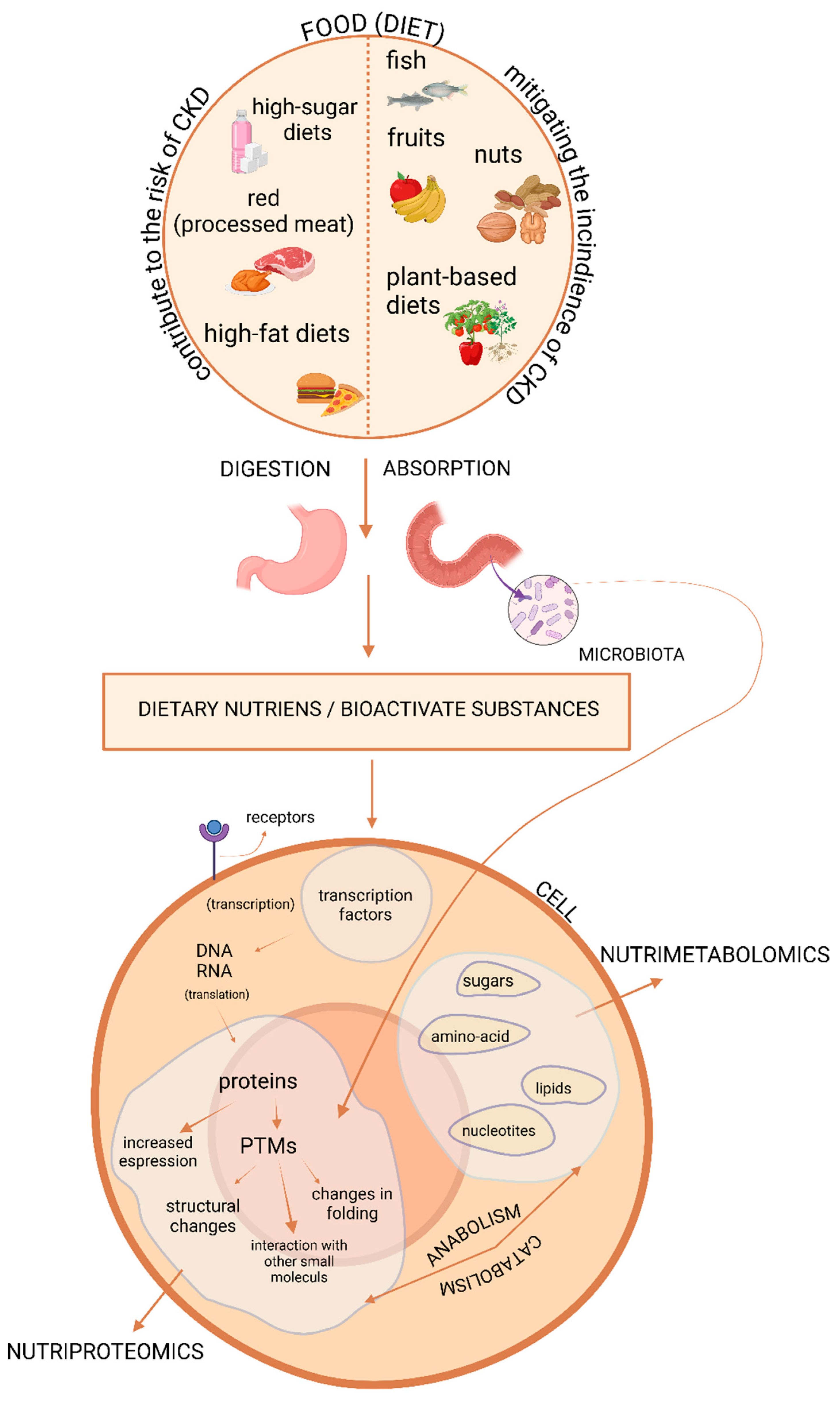

Diet is a well-known, modifiable factor that can either promote renal health or accelerate the onset and progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Advances in multiomics, particularly proteomics and metabolomics, have significantly enhanced our understanding of the molecular mechanisms linking diet to CKD risk. Proteomics offers a comprehensive analysis of protein expression, structure, and interactions, shedding light on how nutritional factors regulate cellular processes and signaling pathways. Meanwhile, metabolomics provides a detailed profile of low-molecular-weight compounds, encompassing both endogenous metabolites and diet-derived molecules, offering valuable insights into the systemic metabolic states that influence kidney function. This review explores the potential of proteomic and metabolomic analysis in identifying molecular signatures identified in human and animal biological samples, such as blood plasma, urine, and, in kidney tissues. These signatures are associated with the intake of specific foods and food groups, as well as overall dietary patterns, which may either contribute to or mitigate the risk of diet-related CKD. By elucidating these complex relationships, such research holds promise for advancing precision nutrition strategies aimed at preserving kidney health.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Molecular Signatures Associated with the Intake of Protein-Rich Foods and Their Connection to CKD

| Sample type | Study design | Type of analysis/ Analysis platform | Major findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | A prospective cohort study of 3 726 middle aged Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities participants without CKD at baseline. Study examined the impact of six protein-rich foods (fish, nuts, legumes, red and processed meat, eggs, and poultry) on serum metabolites over 1 year. Associations were analyzed using multivariable linear regression and meta-analyzed with fixed- effects models, adjusting for key demographic and lifestyle factors. |

Untargeted metabolomic analysis/ GC-MS LC-MS |

Thirty significant associations were found between protein-rich foods and serum metabolites (fish, n = 8; nuts, n = 5; legumes, n = 0; red and processed meat, n = 5; eggs, n = 3; and poultry, n = 9). Metabolites improved the discrimination of high protein intake beyond covariates. Fish consumption was positively linked to 1-docosahexaenoylglycerophosphocholine (22:6n3), which was inversely associated with incident CKD. |

Bernard et al. [23] |

| Plasma | A prospective cohort study of 484 Chronic Kidney Disease in Children participants. Linear regression examined associations between dietary intake of total, animal, and plant protein, as well as chicken, dairy, nuts and beans, red and processed meat, fish, and eggs. Cox models assessed the link between protein-related metabolites and CKD progression, adjusting for demographic and clinical covariates. | Untargeted metabolomic analysis/ LC-MS |

Sixty metabolites were linked to dietary protein intake, with ten also associated with CKD progression (animal protein: 1, dairy: 7, red and processed meat: 2, nuts and beans: 1). These included amino acids, lipids, nucleotides, and other compounds. Notably, GPE (P-16:0/18:1), linked to red and processed meat, was associated with an 88% higher CKD risk, while 3- ureidopropionate showed a 48% lower risk. | Ren et al. [32] |

| Serum | A randomized clinical trial examined dietary protein restriction in CKD patients (age 18-70). Participants with moderate CKD (n = 585) followed either a moderate– or low-protein diet, while those with severe CKD (n = 255) followed a low- or very-low diet. Multivariable linear regression was used to analyzed differences in log-transformed metabolite levels based on randomly assigned dietary protein intervention groups. | Untargeted metabolomic analysis/ RP-UHPLC/MS |

130 metabolites differed significantly between participants on a low-protein vs moderate-protein diet, and 32 metabolites between those on a very-low-protein diet vs low-protein diet. 11 metabolites were consistently associated with protein intake across both studies: 3-methylhistidine, N-acetyl-3-methylhistidine, xanthurenate, isovalerylcarnitine, creatine, kynurenate, 1-(1-enyl-palmitoyl)-2-arachidonoyl-GPE (P-16:0/20:4), 1-(1-enyl-stearoyl)-2-arachidonoyl-GPE (P-18:0/20:4), 1-(1-enyl-palmitoyl)-2-arachidonoyl-GPC (P-16:0/20:4), sulfate, and γ-glutamylalanine. | Rebholz et al. [33] |

| Kidney tissue | A study on mice with adenine-induced chronic kidney disease divided into three groups (n = 10 per group): (1) control group - fed a standard diet, (2) model group - fed a diet containing 0.2% adenine; and (3) sheep milk group - fed a diet with 0.2% adenine supplemented with 1.25 ml of sheep milk fed for four weeks |

Proteomic analysis/ SDS-PAGE and LC-MS/MS Non-targeted metabolomic analysis/ LC-MS/MS |

Proteomic analysis revealed decresed expression of fibrosis-associated proteins, including VCAM1 and collagen, suggesting a role in slowing CKD progression. Metabolomic profiling showed decresed TMAO levels, a biomarker of kidney damage. Integrated data confirmed the downregulation of the JAK1/STAT3/HIF-1α signaling pathway, contributing to the delay in renal injury. |

Wei et al. [35] |

3. Molecular Signatures Associated with the Intake of High-Fat Diets and Their Connection to CKD

| Sample type | Study design | Type of analysis/ Analysis platform | Major findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

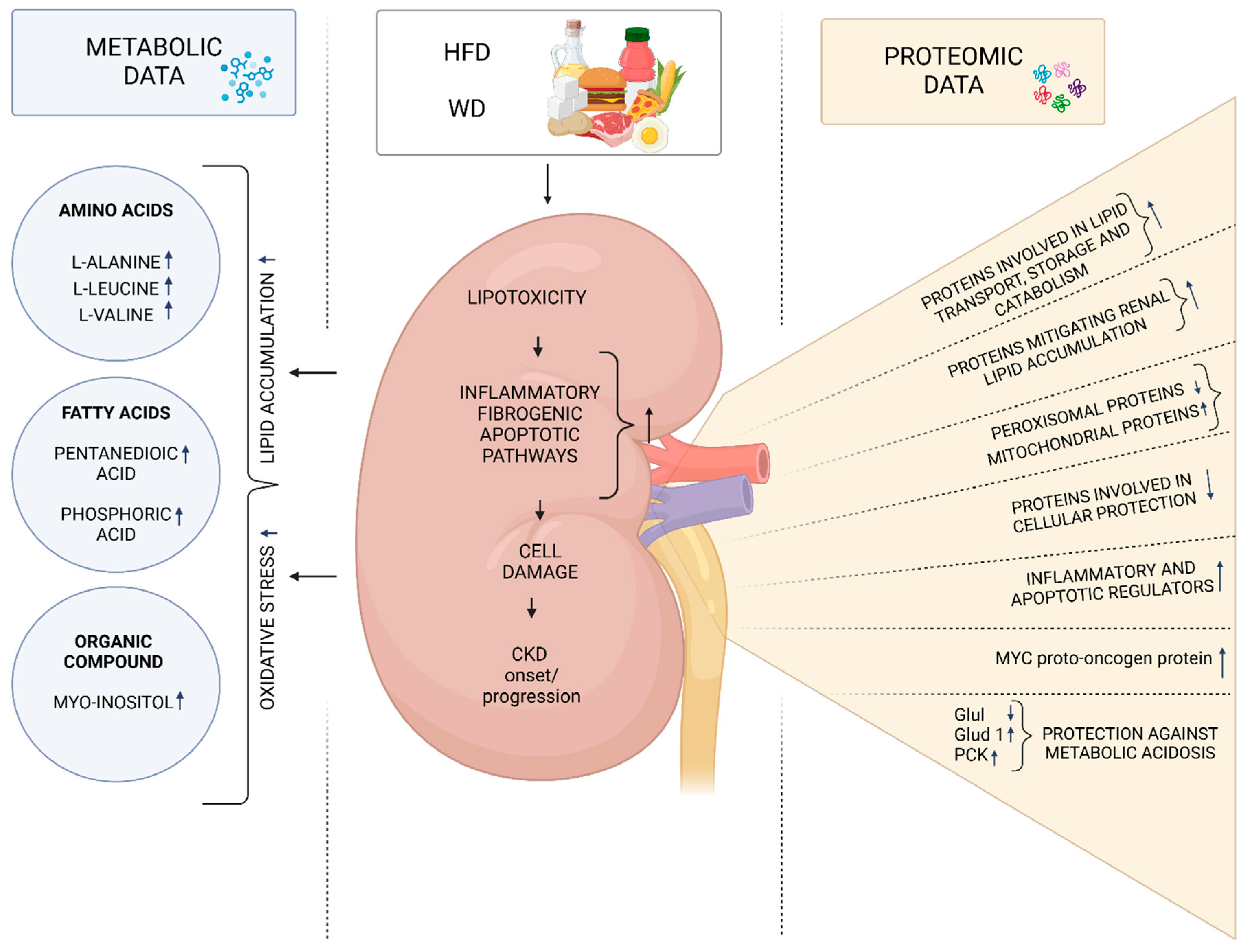

| Kidney tissue | A study on 6-week-old male C57BL/6N mice divided into two groups (n = 7 per group): (1) control group - fed a normal chow diet (10% fat), (2) HFD group - fed a high-fat-diet (60% fat) for fourteen weeks. |

Proteomic analysis/ nanoHPLC MS/MS | The HF diet up-regulated renal proteins involved in lipid transport, storage and localization. The HF diet altered lipid metabolism from peroxisomes to mitochondria by down-regulating peroxisomal proteins and key components of the PPAR pathway. Increased expression of HMGCS2, CPT2, FABP4, ACAA2, ACOT2, CPT1A and ALDH2, while BDH1 and ACADL were down-regulated. |

Dozio et al. [46] |

| Kidney tissue | A study on 10-week-old male Swiss-Webster mice divided into four groups (n = 6 per group): (1) STD group - fed a standard diet, (2) SFA group – fed a diet rich in saturated fatty acids (3) HR group – fed a HFD diet rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids with a linoleic to α-linolenic acid ratio of 14:1 (4) LR group - fed a HFD diet rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids with a linoleic to α-linolenic acid ratio of 5:1 for three months. | Proteomic analysis/ 2-DE MALDI-TOF MS |

SFA diet affected 11 proteins: 7 up-regulated (PRDX6, PRDX1, PPIA, LDHD, ACOT2, HIBADH, ALDH6A1) and 4 down-regulated (HSPD1, Apo-E, IDH1, ATP5F1B). In the HR group, 7 proteins were altered: 4 down-regulated (HSPA5, PRDX6, ATP5F1B, ALDH6A1), and 3 up-regulated (PPIA, AKR1A1, IDH2). The LR diet altered 12 proteins: 9 up-regulated (PRDX1, P4HB, AKR1A1, ENO1, ETHE1, IDH1, ETFA, ALDH6A1, HAAO) and 3 down-regulated (IDH1, ATP5F1B). |

Wypych et al. [47] |

| Kidney tissue | A study on 5-week-old male C57BL/6J mice divided into four groups: (1) control – standard chow diet (2) WD group – high-fat (42% kcal), high saturated fatty acids (>60% total), and high sucrose (34%) diet for 8 weeks, (3) control + AA – standard chow with aristolochic acid (AA) every three days for 3 weeks, (4) WD + AA – WD diet with AA every three days for 3 weeks. | Proteomic analysis/ TMT-labeled peptides were analyzed on an Orbitrap Eclipse Tribrid Mass Spectrometer |

Approximately 1,000 proteins were differentially expressed in the kidneys of AA-treated mice on a WD compared to controls. WD exacerbated AA-induced down-regulation of carbon metabolism pathways, including glycolysis, pyruvate, TCA, and fatty acid metabolism, indicating impaired kidney energy homeostasis. This group also showed increased immune-related proteins, suggesting kidney inflammation. The WD diet alone altered 19 proteins compared to controls, with 12 expressed in the proximal tubules. Up-regulated proteins: Arg2, Ces1d, Glud1, Pck1, Ugt2b37, Vill, down-regulated proteins: Acmsd, Acsm3, Car3, Glul, Hsd11b1, Phgdh. |

Oe et al. [49] |

| Kidney tissue, serum | A study on 8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice divided into three groups (n = 7 per group): (1) control group – fed a standard diet, (2) HGD group - fed high glucose diet (75.9% carbohydrate, 14.7% protein and 9.4% fat), (3) HFD group – fed a high fat diet (25% carbohydrate, 15% protein and 60% fat) | Untargeted metabolomic analysis/ GC-MS |

The HFD diet affected 28 metabolites (AA, FA derivatives and others), with 9 increased and 1 decresed in serum, and 6 in the kidney. These metabolites are involved in many metabolic pathways related to energy, amino acid and lipid metabolism. | Xie et al. [50] |

| Serum, liver, muscle tissue |

A study on male Sprague-Dawley rats. Rats underwent 5/6 nephrectomy for CKD induction or sham surgery. After two weeks, rats were fed a standard chow diet (SCD) or a high-fat diet (HFD) for 16 weeks to produce rat models for CKD-induced insulin resistance or HFD. | Untargeted metabolomic analysis/ UPLC-MS/OPLS-DA |

A total of 101 metabolites in serum, 59 in liver, and 41 in muscle were associated with CKD-induced IR, while 58 in serum, 38 in liver, and 17 in muscle were linked to HFD-induced IR. CKD affected tryptophan and arginine metabolism, whereas HFD impaired lipid and purine metabolism. | Xu et al. [51] |

3. Molecular Signatures Associated with the Intake of Pre-, Pro-, and Synbiotics and Their Connection to CKD

| Sample type | Study design | Type of analysis/ Analysis platform | Major findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cecal contents | A study on 10-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 9 per group) induced CKD with a diet containing 0.7% adenine for 2 weeks, followed by a three-week intervention with either digestible starch (amylopectin) – CKD-DS group - or indigestible starch (HAMRS2) – CKD-RS group. Both isocaloric diets contained 14.5% protein, 66.9% carbohydrate, and 18.6% fat. | Proteomic analysis/ TMT - Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer iBAQ HPLC |

A total of 9,386 unique proteins were identified, with 5,834 quantified. In CKD-RS vs. CKD-DS rats, 125 proteins with reduced expression (enzymes, proteins associated with humoral immune response, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (thioredoxin, S100-A6) while 54 increased (enzymes, immunoglobulins, annexins, ion channel proteins, sodium pump proteins). |

Zybailov et al. [60] |

| Plasma, urine |

A nonrandomized, open-label, 3-phase crossover study with repeated measures. Of 17 eligible subjects, 13 completed treatment. Phases included pretreatment (weeks 1-8), p-inulin treatment (weeks 9-20, 8g p-inulin twice daily), and post-treatment (weeks 21-28). | Untargeted metabolomics analysis/ GC-MS |

Urinary levels of carbohydrate metabolites, including raffinose, 1-kestose and beta-gentiobiosis, increased. During p-inulin supplementation, urine levels of beta-sitosterol and 4-methylcatechol increased, with 4-methylcatechol inversely correlated with p-cresol. | Sohn et al. [61] |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Onopiuk, A.; Tokarzewicz, A.; Gorodkiewicz, E. Cystatin C: a kidney function biomarker. Advan. Clin. Chem. 2015, 68, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogobuiro, I.; Tuma, F. Physiology. Renal. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van Beusecum, J.; Inscho, E.W. Regulation of renal function and blood pressure control by P2 purinoceptors in the kidney. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 2015, 21, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahay, M.; Kalra, S.; Bandgar, T. Renal endocrinology: The new frontier. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 16, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro, C.; Giannese, D.; Panichi, V.; Cupisti, A. Mediterranean dietary pattern adjusted for CKD patients: the MedRen diet. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Caulfield, L.E.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Steffen, L.M.; Grams, M.E.; Coresh, J.; Rebholz, C.M. Plant-based diets and incident CKD and kidney function. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, D.; Vellanki, K.; Kramer, H. The Western diet and chronic kidney disease. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2015, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, D.E.; Peruchetti, D.B.; Souza, M.C.; das Graças Henriques, M.G.; Pinheiro, A.A.S.; Caruso-Neves, C. A high salt diet induces tubular damage associated with a pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic response in a hypertension-independent manner. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis 2020, 1866, 165907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Mo, H.; Zhuo, H.; Yu, C.; Liu, Y. High fat diet induces kidney injury via stimulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Front. Med 2022, 9, 851618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Westing, A.C.; Küpers, L.K.; Geleijnse, J.M. Diet and kidney function: a literature review. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2020, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Chauveau, P.; Carrero, J.J. Risks and benefits of different dietary patterns in CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis 2023, 81, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Lopez, O.; Martinez, J.A.; Milagro, F.I. Holistic integration of omics tools for precision nutrition in health and disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.E.; Song, R.J.; Xu, X.; Gerszten, R.E.; Ngo, D.; Clish, C.B.; Corlin, L.; Ma, J.; Xanthakis, V.; Jacques, P.F. Proteomic and metabolomic correlates of healthy dietary patterns: the Framingham Heart Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, R.F.; Rhee, E.P. Proteomics and metabolomics in kidney disease, including insights into etiology, treatment, and prevention. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amrani, S.; Al-Jabri, Z.; Al-Zaabi, A.; Alshekaili, J.; Al-Khabori, M. Proteomics: Concepts and applications in human medicine. World J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, D.; Winkelmann, I.; Johnson, I.T.; Mariman, E.; Wenzel, U.; Daniel, H. Proteomics in nutrition research: principles, technologies and applications. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 94, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Michalak, M.; Agellon, L.B. Importance of nutrients and nutrient metabolism on human health. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2018, 91, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh, V.; Hettiarachchy, N.S. Nutriproteomics: A promising tool to link diet and diseases in nutritional research. BBA-Proteins Proteomics 2012, 1824, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Zhong, H.; Cheng, L.; Li, L.-P.; Zhang, D.-K. Post-translational protein lactylation modification in health and diseases: a double-edged sword. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobel, L.; Cao, Y.G.; Fenn, K.; Glickman, J.N.; Garrett, W.S. Diet posttranslationally modifies the mouse gut microbial proteome to modulate renal function. Science 2020, 369, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turi, K.N.; Romick-Rosendale, L.; Ryckman, K.K.; Hartert, T.V. A review of metabolomics approaches and their application in identifying causal pathways of childhood asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Hu, F.B. Use of metabolomics in improving assessment of dietary intake. Clin. Chem. 2018, 64, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, L.; Chen, J.; Kim, H.; Wong, K.E.; Steffen, L.M.; Yu, B.; Boerwinkle, E.; Levey, A.S.; Grams, M.E.; Rhee, E.P. Serum Metabolomic Markers of Protein-Rich Foods and Incident CKD: Results From the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Kidney Med. 2024, 6, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotea, I.; Sirbu, C.; Plotuna, A.-M.; Tîrziu, E.; Badea, C.; Berbecea, A.; Dragomirescu, M.; Radulov, I. Integrating (nutri-) metabolomics into the one health tendency—the key for personalized medicine advancement. Metabolites 2023, 13, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, G.-J.; Rhee, C.M.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Joshi, S. The effects of high-protein diets on kidney health and longevity. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 1667–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marckmann, P.; Osther, P.; Pedersen, A.N.; Jespersen, B. High-protein diets and renal health. . J. Ren. Nutr. 2015, 25, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juraschek, S.P.; Appel, L.J.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Miller Iii, E.R. Effect of a high-protein diet on kidney function in healthy adults: results from the OmniHeart trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2013, 61, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sällström, J.; Carlström, M.; Olerud, J.; Fredholm, B.B.; Kouzmine, M.; Sandler, S.; Persson, A.E.G. High-protein-induced glomerular hyperfiltration is independent of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism and nitric oxide synthases. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 299, R1263–R1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, A.; Zhao, Y.; Chu, L.; Yang, Y.; Jin, Z. A review on animal and plant proteins in regulating diabetic kidney disease: Mechanism of action and future perspectives. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 119, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrazaga, I.; Micard, V.; Gueugneau, M.; Walrand, S. The role of the anabolic properties of plant-versus animal-based protein sources in supporting muscle mass maintenance: a critical review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, P.; Gavela, E.; Vizcaíno, B.; Huarte, E.; Carrero, J.J. Optimizing diet to slow CKD progression. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 654250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Chen, J.; Abraham, A.G.; Xu, Y.; Siewe, A.; Warady, B.A.; Kimmel, P.L.; Vasan, R.S.; Rhee, E.P.; Furth, S.L. Plasma metabolomics of dietary intake of protein-rich foods and kidney disease progression in children. J. Ren. Nutr. 2024, 34, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebholz, C.M.; Zheng, Z.; Grams, M.E.; Appel, L.J.; Sarnak, M.J.; Inker, L.A.; Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J. Serum metabolites associated with dietary protein intake: results from the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flis, Z.; Molik, E. Importance of bioactive substances in sheep’s milk in human health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Jiang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Yuan, H.; An, X. Multi-omics analysis of kidney tissue metabolome and proteome reveals the protective effect of sheep milk against adenine-induced chronic kidney disease in mice. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 7046–7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zeng, L.; Zheng, C.; Song, B.; Li, F.; Kong, X.; Xu, K. Inflammatory links between high fat diets and diseases. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Fuster, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines: a link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. J. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoelson, S.E.; Herrero, L.; Naaz, A. Obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2169–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancheva, S.; Jelenik, T.; Alvarez-Hernandez, E.; Roden, M. Interorgan metabolic crosstalk in human insulin resistance. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1371–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, X.Z.; Varghese, Z.; Moorhead, J.F. An update on the lipid nephrotoxicity hypothesis. Nature Reviews Nephrology 2009, 5, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Agati, V.D.; Chagnac, A.; De Vries, A.P.; Levi, M.; Porrini, E.; Herman-Edelstein, M.; Praga, M. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: clinical and pathologic characteristics and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, A.P.J.; Ruggenenti, P.; Ruan, X.Z.; Praga, M.; Cruzado, J.M.; Bajema, I.M.; D D'Agati, V.; Lamb, H.J.; Barlovic, D.P.; Hojs, R. Fatty kidney: emerging role of ectopic lipid in obesity-related renal disease. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aguila, M.B.; Mandarim-de-Lacerda, C.A. Effects of chronic high fat diets on renal function and cortical structure in rats. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2003, 55, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Agborbesong, E.; Li, X. The role of mitochondria in acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease and its therapeutic potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ge, X.; Li, X.; He, J.; Wei, X.; Du, J.; Sun, J.; Li, X.; Xun, Z.; Liu, W. High-fat diet promotes renal injury by inducing oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozio, E.; Maffioli, E.; Vianello, E.; Nonnis, S.; Grassi Scalvini, F.; Spatola, L.; Roccabianca, P.; Tedeschi, G.; Corsi Romanelli, M.M. A wide-proteome analysis to identify molecular pathways involved in kidney response to high-fat diet in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, A.; Ożgo, M.; Bernaciak, M.; Herosimczyk, A.; Barszcz, M.; Gawin, K.; Ciechanowicz, A.K.; Kucia, M.; Pierzchała, M.; Poławska, E. Effect of feeding high fat diets differing in fatty acid composition on oxidative stress markers and protein expression profiles in mouse kidney. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2024, 33, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oe, Y.; Kim, Y.C.; Kanoo, S.; Goodluck, H.A.; Lopez, N.; Diedrich, J.; Pinto, A.M.; Evensen, K.G.; Currais, A.J.M.; Maher, P. Western diet exacerbates a murine model of Balkan nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2025, 328, F15–F28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Xue, X.; Zhao, S.; Geng, C.; Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Gan, Y.; Li, H. The impact of high-glucose or high-fat diets on the metabolomic profiling of mice. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1171806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X. Metabonomic profiling reveals difference in altered metabolic pathways between chronic kidney disease and high-fat-induced insulin resistance in rats. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2018, 43, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davani-Davari, D.; Negahdaripour, M.; Karimzadeh, I.; Seifan, M.; Mohkam, M.; Masoumi, S.J.; Berenjian, A.; Ghasemi, Y. Prebiotics: definition, types, sources, mechanisms, and clinical applications. Foods 2019, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutkins, R.W.; Krumbeck, J.A.; Bindels, L.B.; Cani, P.D.; Fahey Jr, G.; Goh, Y.J.; Hamaker, B.; Martens, E.C.; Mills, D.A.; Rastal, R.A. Prebiotics: why definitions matter. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, K.R.; Naik, S.R.; Vakil, B.V. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics-a review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 7577–7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzi, S.; Haghighatdoost, F. The effects of prebiotic, probiotic, and synbiotic supplementation on blood parameters of renal function: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Nutrition 2018, 51, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Klein, K.; Johnson, D.W.; Campbell, K.L. Pre-, pro-, and synbiotics: do they have a role in reducing uremic toxins? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nephrol. 2012, 2012, 673631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; Xin, W.; Xiong, J.C.; Yao, M.Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, J.H. The Intestinal Microbiota and Metabolites in the Gut-Kidney-Heart Axis of Chronic Kidney Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.J.; Guo, J.; Wang, Q.H.; Wang, L.S.; Wang, Y.H.; Zhang, F.; Huang, W.J.; Zhang, W.T.; Liu, W.J.; Wang, Y.X. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics for the improvement of metabolic profiles in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzi, S.; Mohd-Yusof, B.-N.; Majid, H.-A.; Ismail, A.; Kamaruddin, N.-A. Effect of microbial cell preparation on renal profile and liver function among type 2 diabetics: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zybailov, B.L.; Glazko, G.V.; Rahmatallah, Y.; Andreyev, D.S.; McElroy, T.; Karaduta, O.; Byrum, S.D.; Orr, L.; Tackett, A.J.; Mackintosh, S.G. Metaproteomics reveals potential mechanisms by which dietary resistant starch supplementation attenuates chronic kidney disease progression in rats. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0199274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, M.B.; Gao, B.; Kendrick, C.; Srivastava, A.; Isakova, T.; Gassman, J.J.; Fried, L.F.; Wolf, M.; Cheung, A.K.; Raphael, K.L. Targeting Gut Microbiome With Prebiotic in Patients With CKD: The TarGut-CKD Study. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 9, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).