Submitted:

01 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Variables

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

3.4. Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HBM | Health Belief Model |

| MLE | Maximum Likelihood Estimation |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease of 2019 |

Appendix A

| Variable | Before | After | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std.Dev. | |

| Health facility visit | 0.3242 | 0.4682 | 0.3415 | 0.4743 |

| COVID-19 respiratory and general symptoms knowledge | 1.8309 | 1.3659 | 1.8969 | 1.3519 |

| Age | 37.7387 | 13.1062 | 38.0872 | 12.8127 |

| Age squared | 1595.9390 | 1130.4550 | 1614.715 | 1104.909 |

| Female | 0.1185 | 0.3232 | 0.1000 | 0.3001 |

| Rich state | 0.6978 | 0.4593 | 0.6354 | 0.4814 |

| High school or more | 0.3031 | 0.4597 | 0.2836 | 0.4509 |

| No school | 0.1424 | 0.3495 | 0.1600 | 0.3667 |

| Household size | 6.4523 | 3.2521 | 6.2882 | 2.8031 |

| Government transfer | 0.5911 | 0.4917 | 0.6000 | 0.4900 |

| Household consumption expenditure | ₹10070.54 | ₹10896.31 | ₹10,471.34 | ₹11,465.25 |

| Inter_HS> | 3.8581 | 4.0011 | 3.8431 | 3.8214 |

| Inter_Fem&CovidRespGen | 0.1764 | 0.6803 | 0.1615 | 0.6455 |

| Inter_Age&HighSch | 10.4247 | 17.2461 | 9.8236 | 17.0400 |

References

- Filip, R. , Gheorghita Puscaselu, R., Anchidin-Norocel, L., Dimian, M., & Savage, W. K. (2022). Global Challenges to Public Health Care Systems during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of Pandemic Measures and Problems. In Journal of Personalized Medicine (Vol. 12, Issue 8). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Ali, J. , Singh, S., & Khan, W. Health awareness of rural households towards COVID-19 pandemic in India: Evidence from Rural Impact Survey of the World Bank. Journal of Public Affairs 2022, e2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. , Feng, S., Wong, I. O. L., Ip, D. K. M., Cowling, B. J., & Lau, E. H. Y. A population-based study on healthcare-seeking behaviour of persons with symptoms of respiratory and gastrointestinal-related infections in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splinter, M. J. , Velek, P., Kieboom, B. C. T., Ikram, M. A., de Schepper, E., Ikram, M. K., & Licher, S. Healthcare avoidance during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and all-cause mortality: a longitudinal community-based study. British Journal of General Practice 2023, BJGP.2023.0637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. L. , Liao, S. L., Huang, H. L., Tsai, P. J., Huang, H. H., Lu, C. Y., & Ho, W. S. Impact of post-COVID-19 changes in outpatient chronic patients’ healthcare-seeking behaviors on medical utilization and health outcomes. Health Economics Review 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, M. S. , Peprah, P., Morgan, A. K., & Agyemang-Duah, W. Staying in or out? COVID-19-induced healthcare utilization avoidance and associated socio-demographic factors in rural India. BMC Public Health 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujolar, G. Oliver-Anglès, A., Vargas, I., & Vázquez, M. L. (2022). Changes in Access to Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. In International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (Vol. 19). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Bastani, P. , Mohammadpour, M., Samadbeik, M., Bastani, M., Rossi-Fedele, G., & Balasubramanian, M. Factors influencing access and utilization of health services among older people during the COVID − 19 pandemic: a scoping review. Archives of Public Health 2021, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. , Xu, Z., Wei, X., Fu, Y., Zhu, Z., Wang, Q., Wang, Q., Liu, Q., Guo, J., Hao, Y., & Yang, L. Analysis of health service utilization and influencing factors due to COVID-19 in Beijing: a large cross-sectional survey. Health Research Policy and Systems 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, Z. , Lotfi, F., Bayati, M., & Kavosi, Z. The effect of Covid-19 pandemic on healthcare utilization in public vs private centers in Iran: a multiple group interrupted time-series analysis. BMC Health Services Research 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K. K. C. , Walline, J. H., Chan, E. Y. Y., Huang, Z., Lo, E. S. K., Yeoh, E. K., & Graham, C. A. Health Service Utilization in Hong Kong During the COVID-19 Pandemic – A Cross-sectional Public Survey. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 2022, 11, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splinter, M. J. , Velek, P., Kamran Ikram, M., Kieboom, B. C. T., Peeters, R. P., Bindels, P. J. E., Arfan Ikram, M., Wolters, F. J., Leening, M. J. G., de Schepper, E. I. T., & Licher, S. Prevalence and determinants of healthcare avoidance during the COVID-19 pandemic: A population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS Medicine 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P. , Leite, A., Esteves, S., Gama, A., Laires, P. A., Moniz, M., Pedro, A. R., Santos, C. M., Goes, A. R., Nunes, C., & Dias, S. Factors associated with the patient’s decision to avoid healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahakyan, S. , Muradyan, D., Giloyan, A., & Harutyunyan, T. Factors associated with delay or avoidance of medical care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Armenia: results from a nationwide survey. BMC Health Services Research 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeisler, M. É. , Marynak, K., Clarke, K. E. N., Salah, Z., Shakya, I., Thierry, J. M., Ali, N., McMillan, H., Wiley, J. F., Weaver, M. D., Czeisler, C. A., Rajaratnam, S. M. W., & Howard, M. E. Delay or Avoidance of Medical Care Because of COVID-19–Related Concerns — United States, June 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2020, 69, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M. I. , Freeman, J., Chadwick, V., & Martiniuk, A. Healthcare Avoidance before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Australian Youth: A Longitudinal Study. Healthcare (Switzerland) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnetz, B. B. , Goetz, C., vanSchagen, J., Baer, W., Smith, S., & Arnetz, J. E. Patient-reported factors associated with avoidance of in-person care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a national survey. PLoS ONE 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L. , Li, C., & Du, H. Predictors of Medical Care Delay or Avoidance Among Chinese Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Patient Preference and Adherence 2023, 17, 3067–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. , & You, M. Avoidance of healthcare utilization in south korea during the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S. , Soares, P., Gama, A., Pedro, A. R., Moniz, M., Laires, P., Goes, A. R., Nunes, C., & Dias, S. Association between perception of COVID-19 risk, confidence in health services and avoidance of emergency department visits: results from a community-based survey in Portugal. BMJ Open 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolić, Š. , Fabijančić, M., & Blaževski, N. How did fear of COVID-19 affect access to healthcare in Central and Eastern Europe? Findings from populations aged 50 or older after the outbreak. Eastern European Economics 2023, 61, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, L. M. , Batterham, P. J., Gulliver, A., Morse, A., Calear, A. L., McCallum, S., Banfield, M., Shou, Y., Newman, E., & Dawel, A. The Factors Associated With Telehealth Use and Avoidance During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. , Tang, Y., Cui, Y., Guan, H., Cui, X., Liu, Y., Liu, Y., Kang, Z., Wu, Q., Hao, Y., & Liu, C. Delay in seeking health care from community residents during a time with low prevalence of COVID-19: A cross-sectional national survey in China. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pung, P. (2021, June 4). FMC Raises COVID-19 Awareness in Rural India. Https://Www.Fmc.Com/En/Articles/Fmc-Raises-Covid-19-Awareness-Rural-India?Form=MG0AV3.

- Biswas, P. (2020, July 1). Knowledge gap on Covid-19 exists in rural communities: UoH study - Times of India. Https://Timesofindia.Indiatimes.Com/Education/News/Knowledge-Gap-on-Covid-19-Exists-in-Rural-Communities-Uoh-Study/Articleshow/76731518.Cms?Form=MG0AV3.

- Passi, R. , Kaur, M., Lakshmi, P. V. M., Cheng, C., Hawkins, M., & Osborne, R. H. Health literacy strengths and challenges among residents of a resource-poor village in rural India: Epidemiological and cluster analyses. PLOS Global Public Health 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Player, J. (2019, December). Healthcare Access in Rural Communities in India - Ballard Brief. Https://Ballardbrief.Byu.Edu/Issue-Briefs/Healthcare-Access-in-Rural-Communities-in-India?Form=MG0AV3.

- Murakami, K. , Kuriyama, S., & Hashimoto, H. General health literacy, COVID-19-related health literacy, and protective behaviors: evidence from a population-based study in Japan. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, P. , Megnin-Viggars, O., & Rubin, G. J. (2021). What Factors Influence Symptom Reporting and Access to Healthcare During an Emerging Infectious Disease Outbreak? A Rapid Review of the Evidence. In Health Security (Vol. 19, pp. 353–363). Mary Ann Liebert Inc. [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I. M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Education & Behavior 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C. L. , Jensen, J. D., Scherr, C. L., Brown, N. R., Christy, K., & Weaver, J. The Health Belief Model as an Explanatory Framework in Communication Research: Exploring Parallel, Serial, and Moderated Mediation. Health Communication 2015, 30, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyemang-Duah, W. , & Rosenberg, M. W. Healthcare utilization among informal caregivers of older adults in the Ashanti region of Ghana: a study based on the health belief model. Archives of Public Health 2023, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalaseh, L. , Fayoumi, H., & Khalil, B. The Health Belief Model in predicting healthcare workers’ intention for influenza vaccine uptake in Jordan. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7372–7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L. P. , Alias, H., Wong, P. F., Lee, H. Y., & AbuBakar, S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics 2020, 16, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luquis, R. R. , & Kensinger, W. S. Applying the Health Belief Model to assess prevention services among young adults. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education 2019, 57, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S. , Schulz, P. J., & Kang, H. Perceived COVID-19 susceptibility and preventive behaviors: moderating effects of social support in Italy and South Korea. BMC Public Health 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeDonno, M. A. , Longo, J., Levy, X., & Morris, J. D. Perceived Susceptibility and Severity of COVID-19 on Prevention Practices, Early in the Pandemic in the State of Florida. Journal of Community Health 2022, 47, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buehler, A. , Malone, M., & Majerus-Wegerhoff, M. (2006). Patterns of responses to symptoms in rural residents: The Symptom-Action-Time-Line process. In Springer Publishing Company. ASME.

- Janz, N. K. , & Becker, M. H. The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Health Education & Behavior 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. (2024, June 13). About COVID-19. Https://Www.Cdc.Gov/Covid/about/Index.Html.

- Watson, S. & Benisek, A. (2024, October 29). GI Symptoms and Coronavirus (COVID-19). Https://Www.Webmd.Com/Covid/Covid19-Digestive-Symptoms?Form=MG0AV3.

- Mlynaryk, N. (2022, June 16). COVID-19 on the Brain: Neurological Symptoms Persist in Majority of Long-Haulers. Https://Health.Ucsd.Edu/News/Press-Releases/2022-06-15-Covid-19-on-the-Brain-Neurological-Symptoms-Persist-in-Majority-of-Long-Haulers/?Form=mg0av3.

- Mayo Clinic. (2024, November 27). COVID-19, cold, allergies and the flu: What are the differences? Https://Www.Mayoclinic.Org/Diseases-Conditions/Coronavirus/in-Depth/Covid-19-Cold-Flu-and-Allergies-Differences/Art-20503981?Form=MG0AV3.

- Gilliland, M. J. , Phillips, M. M., Raczynski, J. M., Smith, D. E., Cornell, C. E., & Bittner, V. (1999). Health-Care-Seeking Behaviors. In Handbook of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (pp. 95–121). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y. , Li, W., Li, S., Chen, L., An, J., & Lu, S. Enhancing healthcare utilization and reducing preventable hospitalizations: exploring the healthcare-seeking propensity of patients with non-communicable diseases in Rural China. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. , & Leventhal, H. (2008). Symptom perception and health care-seeking behavior. In Handbook of clinical health psychology: Volume 2. Disorders of behavior and health. (pp. 299–328). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B. , de Maria, M., Barbaranelli, C., Matarese, M., Ausili, D., Stromberg, A., Vellone, E., & Jaarsma, T. Symptom Recognition as a Mediator in the Self-Care of Chronic Illness. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, C. (2025, February 21). Top 10 richest states in India by GDSP and GDP per capita, as of 2024. Https://Indianexpress.Com/Article/Trending/Top-10-Listing/Top-10-Richest-States-in-India-by-Gdsp-and-Gdp-per-Capita-as-of-2024-9601172/.

- Lal, S. , Nguyen, T. X. T., Sulemana, A. S., Khan, M. S. R., & Kadoya, Y. Time Discounting and Hand-Sanitization Behavior: Evidence from Japan. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. S. R. , Nguyen, T. X. T., Lal, S., Watanapongvanich, S., & Kadoya, Y. Hesitancy towards the Third Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine among the Younger Generation in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. X. T. , Lal, S., Abdul-Salam, S., Khan, M. S. R., & Kadoya, Y. Financial Literacy, Financial Education, and Cancer Screening Behavior: Evidence from Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulemana, A. S. , Lal, S., Nguyen, T. X. T., Khan, M. S. R., & Kadoya, Y. Pandemic Fatigue in Japan: Factors Affecting the Declining COVID-19 Preventive Measures. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, S. , Nguyen, T. X. T., Sulemana, A. S., Khan, M. S. R., & Kadoya, Y. Does financial literacy influence preventive health check-up behavior in Japan? a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, I. J. Tutorial on maximum likelihood estimation. Journal of Mathematical Psychology 2003, 47, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K. An Introduction to Maximum Likelihood Estimation and Information Geometry. Interdisciplinary Information Sciences 2011, 17, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I. M. The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior. Health Education & Behavior 1977, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of India. (2020a). PM to launch High Throughput COVID. Https://Www.Pib.Gov.in/Newsite/PrintRelease.Aspx?Relid=210269&form=MG0AV3.

- WHO. (2020, August 16). How India scaled up its laboratory testing capacity for COVID19. Https://Www.Who.Int/India/News/Feature-Stories/Detail/How-India-Scaled-up-Its-Laboratory-Testing-Capacity-for-Covid19?Form=MG0AV3.

- Government of India. (2020b, July 27). PM launches High Throughput COVID testing facilities at Kolkata, Mumbai and Noida. Https://Pib.Gov.in/PressReleasePage.Aspx?PRID=1641550&form=MG0AV3.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2024, July 26). Government of India has taken several initiatives through ‘Whole of Government’ approach during the COVID. Https://Pib.Gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.Aspx?PRID=2037420&form=MG0AV3.

- Rangarajan, R. (2021, July 15). Addressing the gap in diagnostic services in rural India - ET HealthWorld. Https://Health.Economictimes.Indiatimes.Com/News/Diagnostics/Addressing-the-Gap-in-Diagnostic-Services-in-Rural-India/84420975?Form=MG0AV3.

- Sharma, A. (2021, May 16). Focus on awareness, increase testing and more: Centre’s guidelines on COVID management in rural, peri-urban areas. Https://English.Jagran.Com/India/Focus-on-Awareness-Increase-Testing-and-More-Centres-Guidelines-on-Covid-Management-in-Rural-Periurban-Areas-10026754?Form=MG0AV3.

- Kordi, F. , Lakeh, N. M., Pouralizadeh, M., & Maroufizadeh, S. Knowledge and behaviors of prevention of COVID-19 and the related factors in the rural population referred to the health centers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, S. J. , Reddy, M. M., Suryanarayana, R., Bhattacharyya, A., & T Kamath, P. B. Awareness, practices, and myths related to coronavirus disease-19 among rural people in Kolar District, South India: A community-based mixed-methods study. Journal of Education and Health Promotion 2022, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha, R. (2021, May 10). Ground report: How Covid-19 has affected India’s rural areas. Https://Www.Indiatoday.in/Magazine/Cover-Story/Story/20210510-Ground-Report-How-Covid-19-Has-Affected-India-s-Rural-Areas-1796993-2021-05-01.

- Behl, A. (2021, May 13). Lack of awareness, poor enforcement of curbs in rural areas leading to more deaths, allege residents. Https://Www.Hindustantimes.Com/Cities/Gurugram-News/Lack-of-Awareness-Poor-Enforcement-of-Curbs-in-Rural-Areas-Leading-to-More-Deaths-Allege-Residents-101620927291536.Html.

- Joshi, B. N. , Bhavya M K, Prusty, R. K., Tandon, D., Kabra, R., Allagh, K. P., & Khan, S. Knowledge, perception and practices adapted during COVID-19: A qualitative study in a district in Maharashtra, India. The Journal of Community Health Management 2024, 11, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, K. , Dhatrak, A., Shyam Sundar, R. N., & Suresh, S. B. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of rural population towards COVID-19 appropriate behaviour in pandemic situation: a cross-sectional study in central India. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health 2022, 9, 4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. , Chakraborty, A., Biswas, R., Baur, B., & Banerjee, R. How effective are health awareness campaigns in India among young citizens? National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I. P. , Chaudhry, M., Sharma, D., & Kaiti, R. Mobile health intervention for promotion of eye health literacy. PLOS Global Public Health 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, R. B. , Endalamaw, A., Erku, D., Wolka, E., Nigatu, F., Zewdie, A., & Assefa, Y. Preparedness, impacts, and responses of public health emergencies towards health security: qualitative synthesis of evidence. Archives of Public Health 2023, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, C. , de Andrade Moral, R., & Power, J. M. Modelling the Non-linear Associations between Age and Health: Implications for Care. Age and Ageing 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moret, L. , Nguyen, J. M., Volteau, C., Falissard, B., Lombrail, P., & Gasquet, I. Evidence of a non-linear influence of patient age on satisfaction with hospital care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2007, 19, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudoy, J. , & Leis, H. (2020). Females are Discontent but Darn Proactive About Their Health and Healthcare. Https://Www.Oliverwyman.Com/Our-Expertise/Perspectives/Health/2019/Mar/Females-Are-Unhappy-but-Darn-Proactive-about-Their-Health-and-He.Html.

- NeuroLaunch editorial team. (2024, September 22). Health-Seeking Behavior: Factors Influencing Healthcare Decisions and Outcomes. Https://Neurolaunch.Com/Health-Seeking-Behavior/?Form=MG0AV3.

- Pinchoff, J. , Santhya, K. G., White, C., Rampal, S., Acharya, R., & Ngo, T. D. Gender specific differences in COVID-19 knowledge, behavior and health effects among adolescents and young adults in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, India. PLoS ONE 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenham, C. (2020, September 30). The gendered impact of the Covid-19 crisis and post-crisis period | Think Tank | European Parliament. Https://Www.Europarl.Europa.Eu/Thinktank/En/Document/IPOL_STU(2020)658227.

- Rakotosamimanana, S. , Mangahasimbola, R. T., Ratovoson, R., & Randremanana, R. V. Determinants of COVID-19-related knowledge and disrupted habits during epidemic waves among women of childbearing age in urban and rural areas of the Malagasy Middle East. BMC Public Health 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S. , Edison, S., & Sofia, A. (2024, May). New Data: Moms Prioritize Household Healthcare Over Their Own. Https://Www.Pymnts.Com/Study_posts/New-Data-Moms-Prioritize-Household-Healthcare-over-Their-Own/?Form=MG0AV3.

- Selvaraj, S. , Karan, A. K., Mao, W., Hasan, H., Bharali, I., Kumar, P., Ogbuoji, O., & Chaudhuri, C. Did the poor gain from India’s health policy interventions? Evidence from benefit-incidence analysis, 2004–2018. International Journal for Equity in Health 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, N. , & Rahut, D. B. Inpatient Healthcare Financing Strategies: Evidence from India. European Journal of Development Research 2021, 33, 1729–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. & Gupta, S. (2012, July 2). Health Infrastructure in India: Critical Analysis of Policy Gaps in the Indian Healthcare Delivery. Https://Www.Vifindia.Org/Occasionalpaper/2012/Health-Infrastructure-in-India-Critical-Analysis-of-Policy-Gaps-in-the-Indian-Healthcare-Delivery.

- Rani, M. , & Siwach, M. Financial Literacy in India: A Review of Literature. Economic and Regional Studies / Studia Ekonomiczne i Regionalne 2023, 16, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, R. , & Singh, R. (2018). Analyzing Factors Affecting Financial Literacy and Its Impact on Investment Behavior Among Adults in India. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Aashima,; Sharma, R. Inequality and disparities in health insurance enrolment in India. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health 2023, 1, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehury, R. K. , Ahmad, I., Behera, M. R., Samal, J., Manchana, V., Mohammed, J., Dehury, P., Behera, D., Desouza, N. V. e., & Dondapati, A. Assessment of out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures on essential medicines for acute and chronic illness: a comparative study across regional and socioeconomic groups in India. BMC Public Health 2025, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Hans India. (2024, December 10). The Influence of Government Policies on Healthcare Financing in India: A Focus on Ayushman Bharat. Https://Www.Thehansindia.Com/Life-Style/Health/the-Influence-of-Government-Policies-on-Healthcare-Financing-in-India-a-Focus-on-Ayushman-Bharat-928656?Form=MG0AV3.

- Sahoo, N. (2023). An Examination of India’s Federal System and its Impact on Healthcare. [CrossRef]

- de Foo, C. , Verma, M., Tan, S. Y., Hamer, J., van der Mark, N., Pholpark, A., Hanvoravongchai, P., Cheh, P. L. J., Marthias, T., Mahendradhata, Y., Putri, L. P., Hafidz, F., Giang, K. B., Khuc, T. H. H., van Minh, H., Wu, S., Caamal-Olvera, C. G., Orive, G., Wang, H., … Legido-Quigley, H. Health financing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic and implications for universal health care: a case study of 15 countries. The Lancet Global Health 2023, 11, e1964–e1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. , & Huang, L. Assessing the impact of public transfer payments on the vulnerability of rural households to healthcare poverty in China. BMC Health Services Research 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, V. , & Raghupathi, W. The influence of education on health: An empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995-2015. Archives of Public Health 2020, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormacq, C. , van den Broucke, S., & Wosinski, J. Does health literacy mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and health disparities? Integrative review. Health Promotion International 2019, 34, E1–E17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aikens NL, Barbarin O. Socioeconomic Differences in Reading Trajectories: The Contribution of Family, Neighborhood, and School Contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2008, 100, 235–51.

- Von Wagner, C. , Knight, K., Steptoe, A., & Wardle, J. Functional health literacy and health-promoting behaviour in a national sample of British adults. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2007, 61, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Focus (Aim) | Method (Design, Sample Size) | Methodology | Country | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnetz, B. B. et al. (2022) | Identify patient-reported factors associated with avoidance of in-person care during COVID-19 | Nationwide online survey, Recruitment via Research Match and Facebook, N = 3840 | Multivariable logistic regression analysis | USA | Avoidance is positively associated with younger age, inability to afford care, greater stress related to COVID, frequent discussions, negative healthcare experience, poor safety awareness, and low communication effectiveness |

| Bastani, P. et al. (2021) | Explore factors affecting healthcare access and utilization for older people during COVID-19 | Scoping review, Systematic search of PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Embase, N = 50 articles | Thematic analysis | USA and India | Positive association between access/utilization and literacy, education, aging attitudes, service availability, policies, and social determinants |

| Czeisler, M. É. et al. (2020) | Investigate delay or avoidance of medical care due to COVID-19 concerns | Cross-sectional survey, online (web-based survey), N = 4,975 | Multivariable Poisson regression | USA | Avoidance is higher in younger adults, unpaid caregivers, individuals with underlying medical conditions, and people of black origin, covered health insurance status |

| Farrer, L. M. et al. (2023) | Examine factors associated with telehealth use and avoidance | Longitudinal survey, online (Email), N = 706 | Logistic regression | Australia | The acceptance of telehealth was higher for those who had used it before, telehealth reduces health care, avoidance was associated with younger age, speaking a language other than or in addition to English, having a current medical diagnosis, and lower levels of acceptability of telehealth. |

| Huang, W. L. et al. (2024) | Impact of post-COVID-19 changes on chronic patients' healthcare-seeking behavior | Cross-sectional in person survey, N = 9,058 | Repeated Measures ANOVA and Generalized Estimating Equation | Taiwan | Chronic patients with irregular outpatient visits had 5.85 fewer annual outpatient visits. Older age, female gender, lower socioeconomic status, and more severe pre-existing conditions were statistically significant factors contributing to reduced outpatient visits and poorer health outcomes.Limited access to healthcare facilities and telemedicine services, and less adherence to medical advice were significant predictors of reduced outpatient visits and poorer health outcomes |

| Hung, K. K. C. et al. (2022) | Analyze self-reported health service utilization in Hong Kong during COVID-19 | Cross-sectional telephone survey, Online, N = 765 | Binary logistic regression analyses | Hong Kong | The factors associated with avoiding medical consultation included being female, married, completing higher education, and those who reported a “large/very large” impact of COVID-19 on their mental health |

| Islam, M. I. et al. (2022) | Examine factors affecting healthcare avoidance among Australian youth pre- and during COVID-19 | Longitudinal in-person survey, N = 1,110 | Bivariate analyses and multiple logistic regression models | Australia | The factors most strongly associated with the avoidance of healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic were the gender of female gender, an ongoing medical condition, and moderately high psychological distress |

| Kang, L. et al. (2023) | Identify predictors of medical care delay or avoidance in Chinese adults | Cross-sectional survey, N = 4,369 | Logistic regression | China | Older adults and adults with chronic diseases were less likely to delay or avoid medical care during the pandemic, individuals who had completed more than three years of care.College, employed adults, and current smokers in rural areas showed a higher likelihood of delaying or avoiding medical care |

| Lee, M. & You, M. (2021) | Examine the influence of socio-demographic and health-related factors on the avoidance of healthcare utilization | Cross-sectional survey, Online, N = 1,000 | Logit regression | South Korea | Sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, income level, and residential area) were related to healthcare avoidance. Among the investigated influencing factors, residential areas highly affected by COVID-19 (i.e., Daegu/Gyeoungbuk region) had the most significant effect on healthcare avoidance |

| Lopes, S. et al. (2022) | To examine the association between the perception of COVID-19 risk, confidence in health services and avoidance of emergency department (ED) visits | Community-based cross sectional online survey, N = 987 | Logistic regression models | Portugal | The odds of avoiding ED were higher for participants who did not have confidence in the response of the health service to conditions outsideCOVID-19 and lower for those who perceived a low risk of being infected in a health provider. Self-reported worse health status increased odds of ED avoidance |

| Oduro, M. S. et al. (2023) | COVID-19-induced healthcare utilization avoidance in rural India | Cross-sectional survey, N = 2,000 | Multivariable Binary Logistic Regression Model via Multiple Imputation | India | Residents of Bihar State are more likely to avoid healthcare during COVID-19 compared to those in Andhra Pradesh. Additionally, individuals with education beyond high school, those using government healthcare facilities, and agricultural daily wage laborers also have higher odds of avoiding healthcare during the pandemic. |

| Pujolar, G. et al. (2022) | The objective is to synthesize the available knowledge on access to health care for non-COVID-19 conditions and to identify knowledge gaps. | Scoping review, Systematic search, N = 53 articles | Scoping review of the literature and PRISMA guide | Various | The most frequent access barrier described for non-COVID-19 conditions related to services was a lack of resources, while barriers related to the population were predisposing (fear of contagion, stigma, or anticipating barriers) and enabling characteristics (worset socioeconomic status and an increase in technological barriers). |

| Rezaei, Z. et al. (2023) | Effect of COVID-19 on healthcare utilization in Iran’s public vs private centers | Time series, Health records data, N = 2,700,000 | Multiple Group Interrupted Time Series Analysis | Iran | The study found that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly decreased healthcare utilization in Iran, with public healthcare centers experiencing a more substantial decline than private centers. |

| Sahakyan, S. et al. (2024) | Assess the prevalence of and risk factors associated with the avoidance or delay of medical care | Cross sectional telephone survey, N = 3,483 | Logistic regression analysis | Armenia | Overall, younger age, being female, higher monthly expenditures, higher perceived threat, and not being vaccinated were associated with avoidance or delay in medical care. |

| Smolić, Š. et al. (2023) | Impact of COVID-19 fear on forgoing healthcare access in Central/Eastern Europe (50+ age) | Cross-national panel survey using telephone interviews, N = 13,033 | Multivariate logistic regression | Central/Eastern Europe | The results suggested that women, younger older adults, more educated individuals, those in poorer health, and those with more chronic health conditions were more likely to avoid healthcare |

| Soares, P. et al. (2021) | Identify factors associated with a patient’s decision to avoid and/or delay healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. | Community based survey, Various Online platforms, N = 2,000 | Poisson regression | Portugal | Healthcare avoidance was more common among women, those with low confidence in the response of the healthcare system, individuals who lost income, experienced negative emotions due to distancing measures, completed the questionnaire before mid-June 2021, and perceived worse health, inadequate government measures, unclear information, and higher risks of COVID-19 infection and complications. |

| Splinter, M. J. et al. (2021) | Prevalence and determinants of healthcare avoidance during COVID-19 from patient perspective | Cross-sectional population-based in-person survey, N = 4.656 | Logistic regression | Netherlands | The determinants related to avoidance were older, female sex, low educational level (primary education versus higher vocational/university), poor self-appreciated health, unemployment, smoking, concern about contracting COVID-19, symptoms of depression and anxiety |

| Splinter, M. J. et al. (2024) | To determine the association between healthcare avoidance during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and all-cause mortality. | Longitudinal community-based in-person survey, N = 5,656 | Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression | Netherlands | Those who avoided health care reported more often symptoms of depression and anxiety and more often rated their health as poor to fair |

| Wang, Z. et al. (2023) | Investigate delay in healthcare-seeking during low COVID-19 prevalence | Cross-sectional national survey, Online, N = 1,317 | Logistic regression | China | Fear of infection, middle age, lower levels of perceived controllability of COVID-19, living with chronic conditions, pregnancy or co-habiting with a pregnant woman, access to internet-based medical care, and higher risk level in the region were significant predictors of the delay in seeking health care |

| Zhang, J. et al. (2024) | Examine health service utilization and COVID-19 in Beijing | Cross-sectional survey, Online, N = 53,924 | Multivariate Tobit regression | China | Factors affecting health service utilization include being female, older than 60 years, non-healthcare workers, rich self-rated income level, having underlying disease, living alone, depressive symptoms and healthy lifestyle habits, as well as longer infection duration, higher infection numbers and severe symptoms. |

| Item | Obs | Sign | Item-test Correlation | Item-rest Correlation | Average Interitem Covariance | Alpha if Item Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | 1950 | + | 0.7265 | 0.5237 | 0.0071069 | 0.4873 |

| Cough | 1950 | + | 0.7471 | 0.5678 | 0.0069213 | 0.4736 |

| Tired | 1950 | + | 0.4190 | 0.2637 | 0.0113556 | 0.5724 |

| Breath | 1950 | + | 0.5874 | 0.3443 | 0.0092194 | 0.5528 |

| Pain | 1950 | + | 0.4737 | 0.2701 | 0.0106615 | 0.5697 |

| Appetite | 1950 | + | 0.2982 | 0.2055 | 0.0125156 | 0.5868 |

| Throat | 1950 | + | 0.4409 | 0.2335 | 0.0110594 | 0.5793 |

| Diarrhea | 1950 | + | 0.0937 | 0.0436 | 0.013396 | 0.6011 |

| Nausea | 1950 | + | 0.1108 | 0.0618 | 0.0133638 | 0.6004 |

| Congestion | 1950 | + | 0.2900 | 0.0965 | 0.0126046 | 0.6070 |

| Smell | 1950 | + | 0.1104 | 0.0331 | 0.013386 | 0.6029 |

| Other | 1950 | + | 0.1162 | 0.0034 | 0.0130539 | 0.5997 |

| Test scale | 0.0112255 | 0.5963 |

| Variable | KMO |

|---|---|

| Fever | 0.6541 |

| Cough | 0.6347 |

| Tired | 0.7104 |

| Difficulty breathing | 0.7748 |

| Muscle pain/body aches | 0.7909 |

| Loss of appetite | 0.6791 |

| Sore throat | 0.8270 |

| Diarrhea | 0.5378 |

| Nausea | 0.5055 |

| Nasal and throat congestion | 0.5922 |

| Loss of smell and taste | 0.4515 |

| Other | 0.5331 |

| Overall | 0.6790 |

|

| Dependent variable | |

|---|---|

| Health facility visit | Binary variable: 1 indicates that the respondents visited health facilities in the last three months, and 0 otherwise |

| Independent variables | |

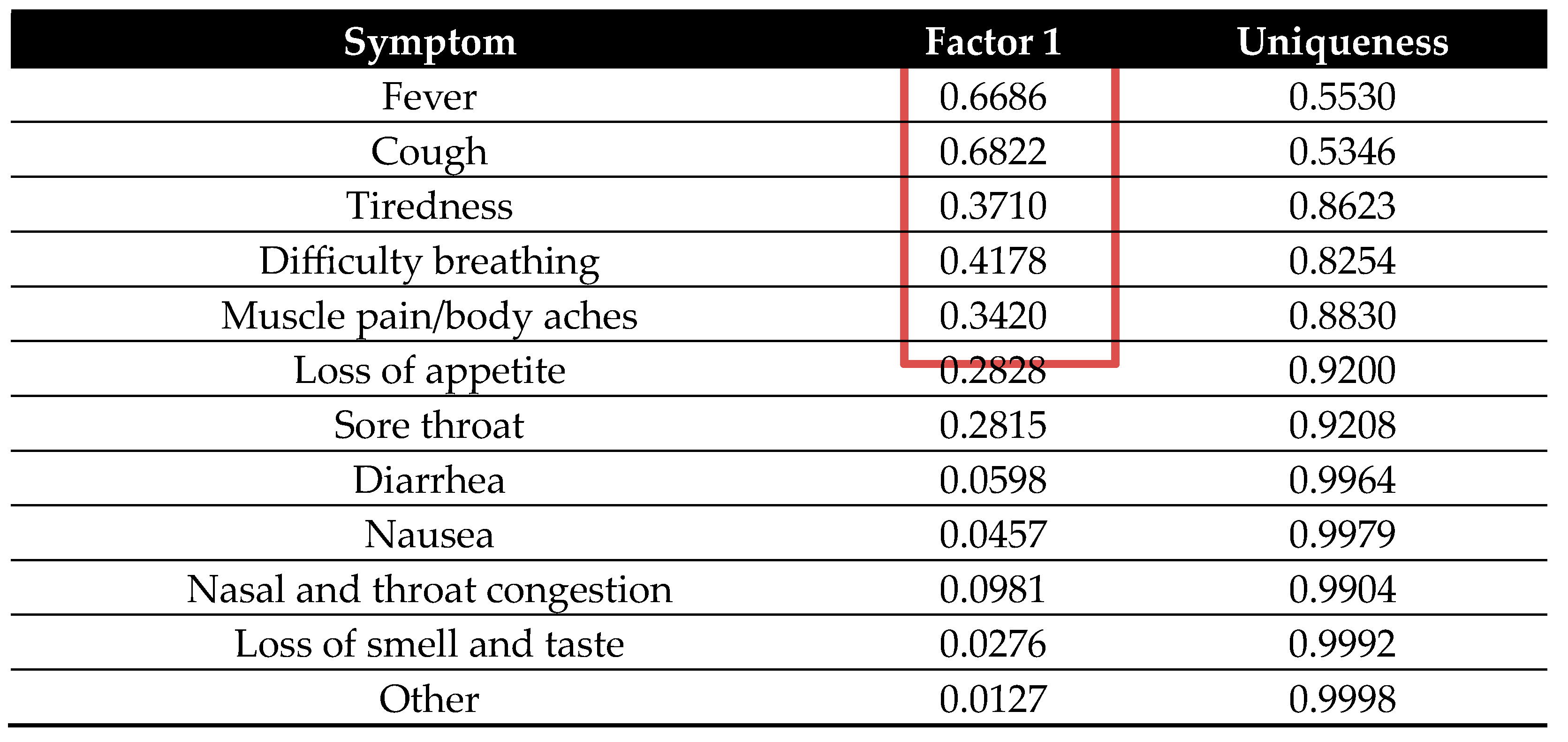

| COVID-19 respiratory and general symptoms knowledge | A composite score (0-5) indicating knowledge of key COVID-19 symptoms: fever, cough, difficulty breathing, muscle pain, and tiredness. Each symptom is coded as binary (1 = aware, 0 = not aware) |

| Age | Continuous variable: age of the respondents |

| Age squared | Continuous variable: Square of each age |

| Female | Binary variable: Equal to 1 if the respondents are females, 0 otherwise |

| No school | Binary variable: Equal to 1 if the respondents did not attend school, 0 otherwise |

| High school or more | Binary variable: Equal to 1 if the respondent attended a high school or more, 0 otherwise |

| Rich state | Binary variable: Equal to 1 if the respondent is from the states of Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan or Uttar Pradesh, 0 otherwise[1]. |

| Household size | Continuous variable: Total number of people living in a household |

| Government transfer | Binary variable: Equal to 1 if the respondent received money in their bank account from the government as part of the relief fund, 0 otherwise |

| Household consumption expenditure | Continuous variable: Respondents’ own consumption expenditure measured in rupees |

| Inter_HS> | Interaction term of household size and government transfer |

| Inter_Fem&CovidRespGen | Interaction term of female and COVID-19 respiratory and general symptoms knowledge |

| Inter_Age&HighSch | Interaction term of age and high school or more |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||

| Health facility visit | 0.3415 | 0.4743 | 0 | 1 |

| Main independent variable | ||||

| COVID-19 respiratory and general symptoms knowledge | 1.8969 | 1.3519 | 0 | 5 |

| Other control variables | ||||

| Age | 38.0872 | 12.8127 | 18 | 91 |

| Age squared | 1614.715 | 1104.909 | 324 | 8281 |

| Female | 0.1000 | 0.3001 | 0 | 1 |

| Rich state | 0.6354 | 0.4814 | 0 | 1 |

| High school or more | 0.2836 | 0.4509 | 0 | 1 |

| No school | 0.1600 | 0.3667 | 0 | 1 |

| Household size | 6.2882 | 2.8031 | 1 | 25 |

| Government transfer | 0.6000 | 0.4900 | 0 | 1 |

| Household consumption expenditure | ₹10,471.34 | ₹11,465.25 | ₹300 | ₹150,000 |

| Inter_HS> | 3.8431 | 3.8214 | 0 | 25 |

| Inter_Fem&CovidRespGen | 0.1615 | 0.6455 | 0 | 5 |

| Inter_Age&HighSch | 9.8236 | 17.0400 | 0 | 82 |

| Observations | 1950 | |||

| Health facility visit | Age groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60+ | Total | |

| 0 | 357 | 386 | 289 | 151 | 101 | 1,284 |

| % | 64.44 | 67.36 | 67.68 | 66.52 | 59.76 | 65.85 |

| 1 | 197 | 187 | 138 | 76 | 68 | 666 |

| % | 35.56 | 32.64 | 32.32 | 33.48 | 40.24 | 34.15 |

| Total | 554 | 573 | 427 | 227 | 169 | 1,950 |

| % | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| F-statistics | 1.13 | |||||

| Health facility visit | Rich states | No school | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Total | |

| 0 | 500 | 784 | 1064 | 220 | 1284 |

| % | 70.32 | 63.28 | 64.96 | 70.51 | 65.85 |

| 1 | 211 | 455 | 574 | 92 | 666 |

| % | 29.68 | 36.72 | 35.04 | 29.49 | 34.15 |

| Total | 711 | 1239 | 1638 | 312 | 1950 |

| % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mean Difference | t-value = -3.1648** | t-value = 1.8973* | |||

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Health facility visit | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| (2) COVID-19 symptoms knowledge | 0.044 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (3) Age | 0.013 | -0.008 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (4) Female | 0.019 | -0.069 | -0.098 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (5) Rich state | 0.072 | 0.059 | 0.193 | -0.216 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (6) High school or more | 0.008 | 0.268 | -0.169 | -0.073 | -0.029 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (7) No school | -0.043 | -0.214 | 0.169 | 0.176 | 0.040 | -0.275 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (8) Household size | 0.038 | 0.035 | -0.040 | -0.062 | -0.043 | 0.011 | -0.031 | 1.000 | |||||

| (9) Government transfer | 0.023 | 0.018 | -0.028 | -0.028 | 0.040 | -0.058 | -0.003 | 0.051 | 1.000 | ||||

| (10) Household consumption expenditure | 0.072 | 0.103 | 0.043 | -0.059 | 0.081 | 0.106 | -0.057 | 0.159 | -0.057 | 1.000 | |||

| (11) Inter_HS> | 0.051 | 0.034 | -0.029 | -0.053 | 0.009 | -0.040 | -0.026 | 0.486 | 0.821 | 0.013 | 1.000 | ||

| (12) Inter_Fem&CovidRespG | 0.002 | 0.156 | -0.103 | 0.751 | -0.159 | -0.013 | 0.053 | -0.027 | -0.010 | -0.022 | -0.020 | 1.000 | |

| (13) Inter_Age&HighSch | 0.014 | 0.254 | 0.058 | -0.087 | -0.009 | 0.917 | -0.252 | -0.007 | -0.092 | 0.113 | -0.071 | -0.035 | 1.000 |

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| High school or more | 9.21 | 0.108520 |

| Inter_Age&HighSch | 9.02 | 0.110889 |

| Inter_HS> | 7.84 | 0.127562 |

| Government transfer | 6.03 | 0.165956 |

| Female | 2.63 | 0.380815 |

| Household size | 2.61 | 0.383621 |

| Inter_Fem&CovidRespGen | 2.57 | 0.389641 |

| Age | 1.57 | 0.638345 |

| COVID-19 respiratory and general symptoms knowledge | 1.23 | 0.814225 |

| No school | 1.18 | 0.846097 |

| Rich state | 1.11 | 0.904194 |

| Household consumption expenditure | 1.06 | 0.942358 |

| Mean VIF | 3.84 | |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: Probability of visiting a health facility | |||

| COVID-19 respiratory and general symptoms knowledge | 0.0421* | 0.0555** | 0.0418* |

| (0.0215) | (0.0235) | (0.0240) | |

| Age | -0.0169 | -0.0233* | |

| (0.0125) | (0.0132) | ||

| Age squared | 0.0002 | 0.0003* | |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | ||

| Female | 0.2786* | 0.4357*** | |

| (0.1516) | (0.1567) | ||

| Inter_Fem&CovidRespGen | -0.1079 | -0.1238* | |

| (0.0716) | (0.0724) | ||

| Inter_Age&HighSch | -0.0000 | 0.0044 | |

| (0.0018) | (0.0052) | ||

| Rich state | 0.2279*** | ||

| (0.0651) | |||

| High school or more | -0.2091 | ||

| (0.2002) | |||

| No school | -0.1710* | ||

| (0.0887) | |||

| Household size | -0.0088 | ||

| (0.0172) | |||

| Government transfer | -0.1843 | ||

| (0.1477) | |||

| Household consumption expenditure | 0.0000** | ||

| (0.0000) | |||

| Inter_HS> | 0.0407* | ||

| (0.0217) | |||

| Constant | -0.4888*** | -0.2307 | -0.2209 |

| (0.0506) | (0.2556) | (0.2966) | |

| Observations | 1,950 | 1,950 | 1,950 |

| Log likelihood | -1250 | -1247 | -1231 |

| Chi2 statistics | 3.835 | 9.890 | 41.99 |

| p-value | 0.0502 | 0.129 | 6.56e-05 |

| Robust standard errors in parentheses | |||

| *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 | |||

| Variables | dy/dx | dy/dx | dy/dx |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Dependent variable: Probability of visiting a health facility | |||

| COVID-19 respiratory and general symptoms knowledge | 0.015** | 0.020** | 0.015* |

| (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.009) | |

| Age | -0.006 | -0.008* | |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | ||

| Age squared | 0.000 | 0.000* | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| Female | 0.102* | 0.157** | |

| (0.055) | (0.056) | ||

| Inter_Fem&CovidRespGen | -0.039 | -0.045* | |

| (0.026) | (0.026) | ||

| Inter_Age&HighSch | -0.000 | 0.002 | |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | ||

| Rich state | 0.082*** | ||

| (0.023) | |||

| High school or more | -0.075 | ||

| (0.072) | |||

| No school | -0.062* | ||

| (0.032) | |||

| Household size | -0.003 | ||

| (0.006) | |||

| Government transfer | -0.066 | ||

| (0.053) | |||

| Household consumption expenditure | 0.000** | ||

| (0.000) | |||

| Inter_HS> | 0.015* | ||

| (0.008) | |||

| Observations | 1,950 | 1,950 | 1,950 |

| Robust standard errors in parentheses | |||

| *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 | |||

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: Probability of visiting a health facility | |||

| COVID-19 respiratory and general symptoms knowledge | 0.0419** | 0.0540*** | 0.0382* |

| (0.0182) | (0.0198) | (0.0204) | |

| Age | -0.0170 | -0.0234* | |

| (0.0125) | (0.0133) | ||

| Age squared | 0.0002 | 0.0003* | |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | ||

| Female | 0.2911* | 0.4354*** | |

| (0.1522) | (0.1568) | ||

| Inter_Fem&CovidRespGen | -0.1137 | -0.1247* | |

| (0.0719) | (0.0723) | ||

| Inter_Age&HighSch | -0.0002 | 0.0045 | |

| (0.0018) | (0.0052) | ||

| Rich state | 0.2218*** | ||

| (0.0656) | |||

| High school or more | -0.2158 | ||

| (0.2003) | |||

| No school | -0.1651* | ||

| (0.0897) | |||

| Household size | -0.0083 | ||

| (0.0171) | |||

| Government transfer | -0.1813 | ||

| (0.1480) | |||

| Household consumption expenditure | 0.0000** | ||

| (0.0000) | |||

| Inter_HS> | 0.0404* | ||

| (0.0216) | |||

| Constant | -0.5043*** | -0.2466 | -0.2244 |

| (0.0510) | (0.2558) | (0.2949) | |

| Observations | 1,950 | 1,950 | 1,950 |

| Log likelihood | -1249 | -1246 | -1231 |

| Chi2 statistics | 5.332 | 11.71 | 41.47 |

| p-value | 0.0209 | 0.0687 | 7.99e-05 |

| Standard errors in parentheses | |||

| *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 | |||

1 These four states were grouped as 1 because they are classified among the top 10 states with the highest GDP per capita in the country [48] . |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).