Submitted:

01 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

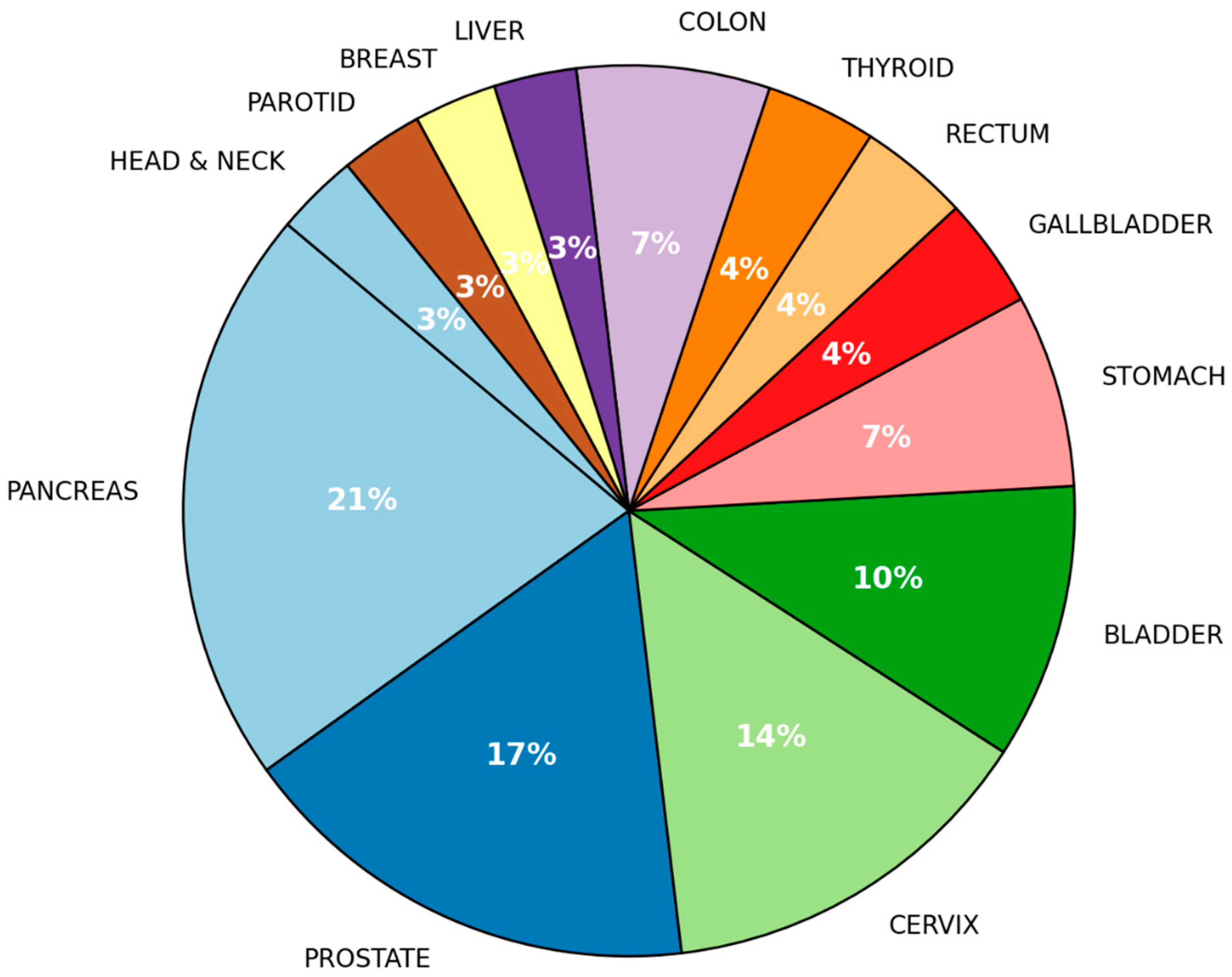

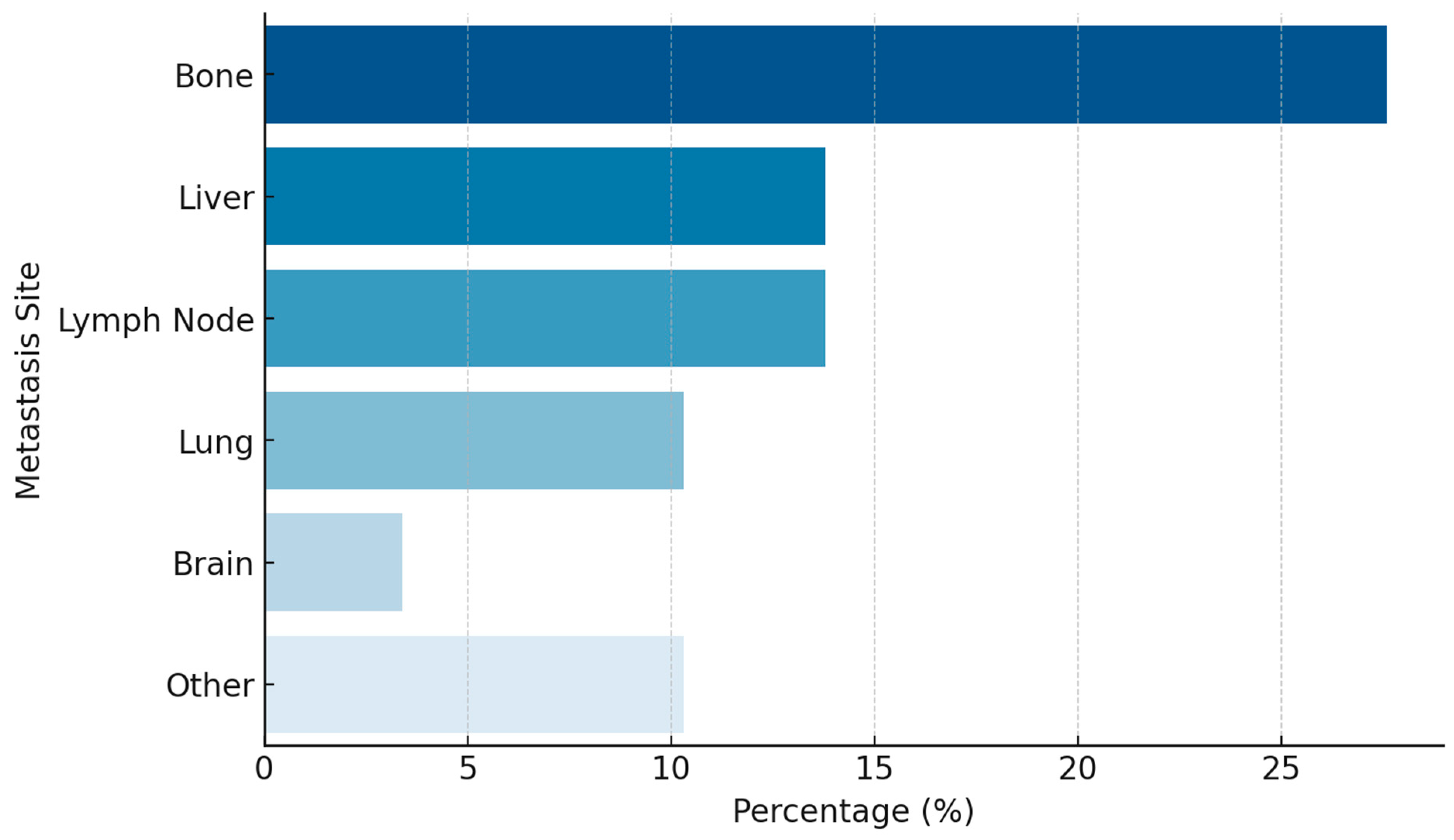

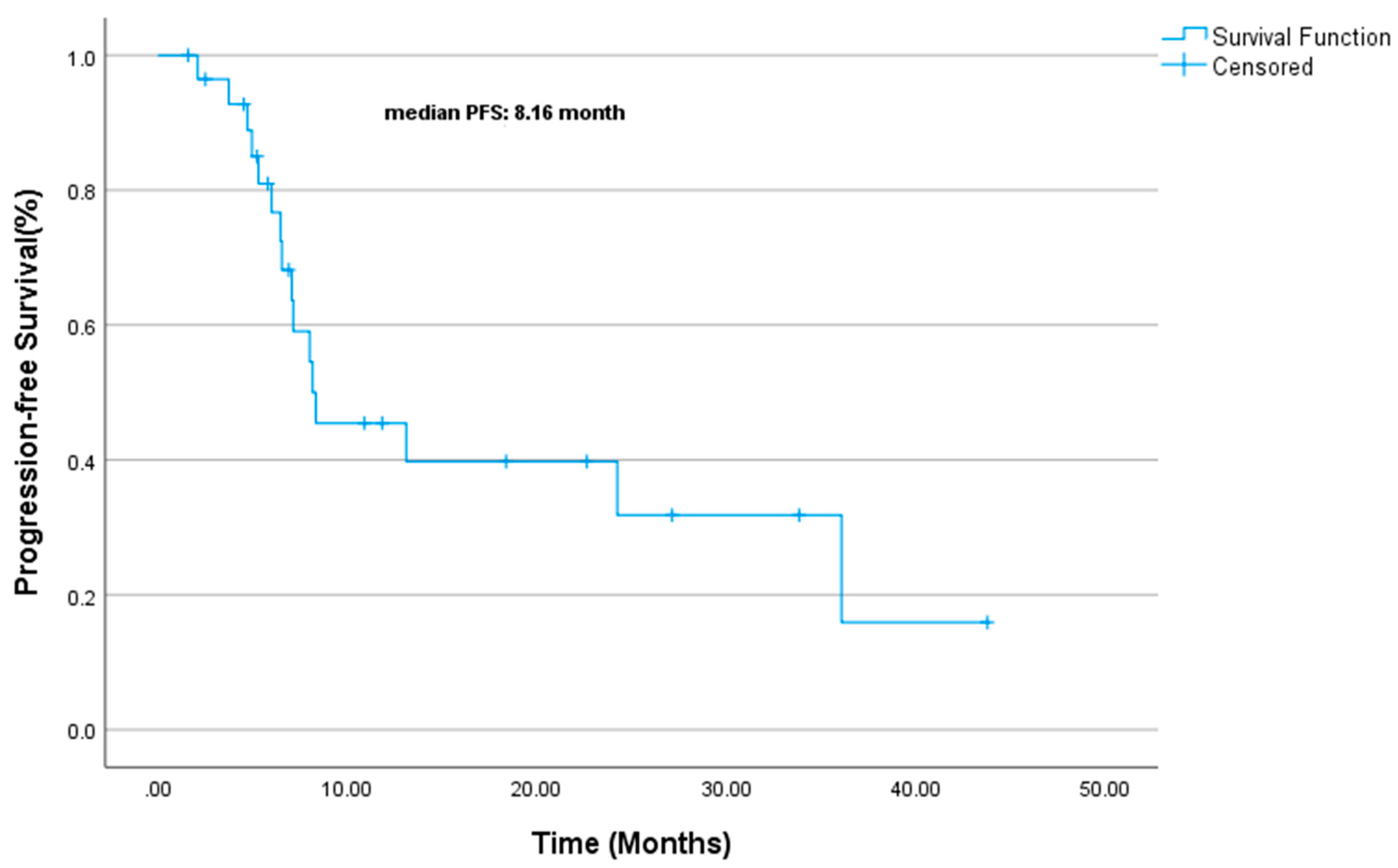

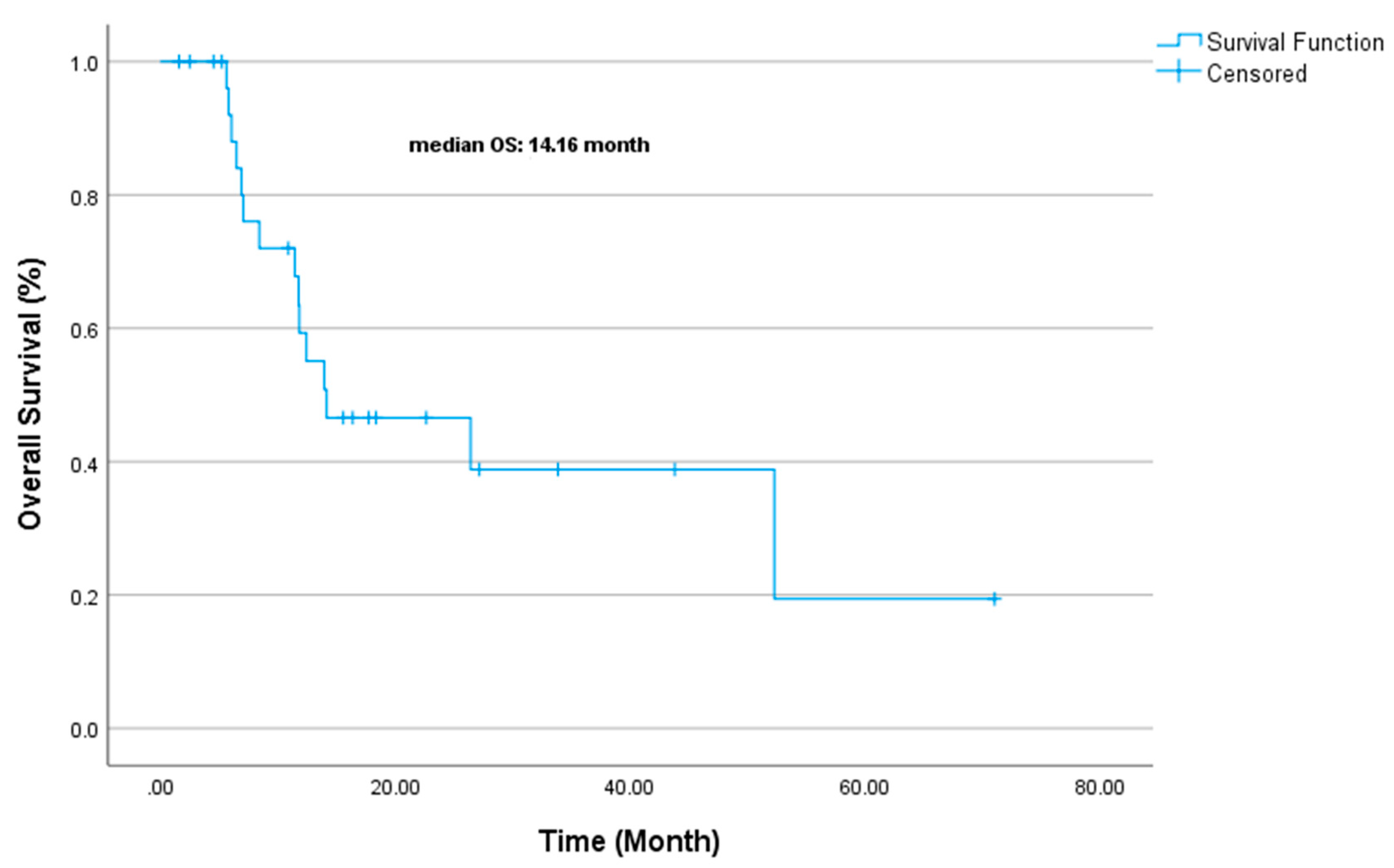

3. Results

4. Discussion

- SCLC-like EP-NECs, frequently harboring TP53 and RB1 mutations, may benefit from DNA repair-targeted therapies.

- Non-neuroendocrine cancer-like EP-NECs, with frequent KRAS and BRAF mutations, could be targeted with BRAF and MEK inhibitors.

- Tumor-agnostic EP-NECs, characterized by epigenetic alterations, might respond to EZH2 inhibitors[33].

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shia, J.; Tang, L.H.; Weiser, M.R.; Brenner, B.; Adsay, N.V.; Stelow, E.B.; Saltz, L.B.; Qin, J.; Landmann, R.; Leonard, G.D. Is nonsmall cell type high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the tubular gastrointestinal tract a distinct disease entity? The American journal of surgical pathology 2008, 32, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qubaiah, O.; Devesa, S.S.; Platz, C.E.; Huycke, M.M.; Dores, G.M. Small intestinal cancer: a population-based study of incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1992 to 2006. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention 2010, 19, 1908–1918. [Google Scholar]

- Walenkamp, A.M.; Sonke, G.S.; Sleijfer, D.T. Clinical and therapeutic aspects of extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. Cancer treatment reviews 2009, 35, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strosberg, J.R.; Coppola, D.; Klimstra, D.S.; Phan, A.T.; Kulke, M.H.; Wiseman, G.A.; Kvols, L.K. The NANETS consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of poorly differentiated (high-grade) extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas. Pancreas 2010, 39, 799–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.C.; Hassan, M.; Phan, A.; Dagohoy, C.; Leary, C.; Mares, J.E.; Abdalla, E.K.; Fleming, J.B.; Vauthey, J.-N.; Rashid, A. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology 2008, 26, 3063–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Sorbye, H.; Baudin, E.; Raymond, E.; Wiedenmann, B.; Niederle, B.; Sedlackova, E.; Toumpanakis, C.; Anlauf, M.; Cwikla, J. ENETS consensus guidelines for high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and neuroendocrine carcinomas. Neuroendocrinology 2016, 103, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, M.G.; Frizziero, M.; Jacobs, T.; Lamarca, A.; Hubner, R.A.; Valle, J.W.; Amir, E. Second-line treatment in patients with advanced extra-pulmonary poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Therapeutic advances in medical oncology 2020, 12, 1758835920915299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantuejoul, S.; Fernandez-Cuesta, L.; Damiola, F.; Girard, N.; McLeer, A. New molecular classification of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and small cell lung carcinoma with potential therapeutic impacts. Translational lung cancer research 2020, 9, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, T.; Tougeron, D.; Baudin, E.; Le Malicot, K.; Lecomte, T.; Malka, D.; et al. Poorly differentiated gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas: are they really heterogeneous? Insights from the FFCD-GTE national cohort. European Journal of Cancer 2017, 79, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, W.D.; Brambilla, E.; Burke, A.P.; Marx, A.; Nicholson, A.G. Introduction to the 2015 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the lung, pleura, thymus, and heart. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2015, 10, 1240–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Edge, S.B.; Greene, F.L.; Byrd, D.R.; Brookland, R.K.; Washington, M.K.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Compton, C.C.; Hess, K.R.; Sullivan, D.C. AJCC cancer staging manual; Springer, 2017; Vol. 1024. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). European journal of cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moertel, C.G.; Kvols, L.K.; O'Connell, M.J.; Rubin, J. Treatment of neuroendocrine carcinomas with combined etoposide and cisplatin. Evidence of major therapeutic activity in the anaplastic variants of these neoplasms. Cancer 1991, 68, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terashima, T.; Morizane, C.; Hiraoka, N.; Tsuda, H.; Tamura, T.; Shimada, Y.; Kaneko, S.; Kushima, R.; Ueno, H.; Kondo, S. Comparison of chemotherapeutic treatment outcomes of advanced extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas and advanced small-cell lung carcinoma. Neuroendocrinology 2012, 96, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heetfeld, M.; Chougnet, C.N.; Olsen, I.H.; Rinke, A.; Borbath, I.; Crespo, G.; Barriuso, J.; Pavel, M.; O'Toole, D.; Walter, T. Characteristics and treatment of patients with G3 gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocrine-related cancer 2015, 22, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Machida, N.; Morizane, C.; Kasuga, A.; Takahashi, H.; Sudo, K.; Nishina, T.; Tobimatsu, K.; Ishido, K.; Furuse, J. Multicenter retrospective analysis of systemic chemotherapy for advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma of the digestive system. Cancer science 2014, 105, 1176–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yachida, S.; Totoki, Y.; Noë, M.; Nakatani, Y.; Horie, M.; Kawasaki, K.; Nakamura, H.; Saito-Adachi, M.; Suzuki, M.; Takai, E. Comprehensive genomic profiling of neuroendocrine carcinomas of the gastrointestinal system. Cancer discovery 2022, 12, 692–711. [Google Scholar]

- Govindan, R.; Aggarwal, C.; Antonia, S.J.; Davies, M.; Dubinett, S.M.; Ferris, A.; Forde, P.M.; Garon, E.B.; Goldberg, S.B.; Hassan, R.; et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immunotherapy for the treatment of lung cancer and mesothelioma. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2022, 10, e003956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, M.G.; Scoazec, J.-Y.; Walter, T. Extrapulmonary poorly differentiated NECs, including molecular and immune aspects. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2020, 27, R219–R238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, L.M.; Altman, D.G.; Sauerbrei, W.; Taube, S.E.; Gion, M.; Clark, G.M. REporting recommendations for tumor MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK). Breast cancer research and treatment 2006, 100, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- de M Rêgo, J.F.; de Medeiros, R.S.S.; Braghiroli, M.I.; Galvão, B.; Neto, J.E.B.; Munhoz, R.R.; Guerra, J.; Nonogaki, S.; Kimura, L.; Pfiffer, T.E. Expression of ERCC1, Bcl-2, Lin28a, and Ki-67 as biomarkers of response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with high-grade extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas or small cell lung cancer. ecancermedicalscience 2017, 11, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesinghaus, M.; Konukiewitz, B.; Keller, G.; Kloor, M.; Steiger, K.; Reiche, M.; Penzel, R.; Endris, V.; Arsenic, R.; Hermann, G. Colorectal mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinomas and neuroendocrine carcinomas are genetically closely related to colorectal adenocarcinomas. Modern Pathology 2017, 30, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frizziero, M.; Kilgour, E.; Simpson, K.L.; Rothwell, D.G.; Moore, D.A.; Frese, K.K.; Galvin, M.; Lamarca, A.; Hubner, R.A.; Valle, J.W. Expanding therapeutic opportunities for extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research 2022, 28, 1999–2019. [Google Scholar]

- Celik, E.; Samanci, N.S.; Derin, S.; Bedir, S.; Degerli, E.; Oruc, K.; Oztas, N.S.; Alkan, G.; Senyigit, A.; Turna, H. A single center’s experience of the extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas. Northern Clinics of Istanbul 2022, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weaver, J.M.J.; Hubner, R.A.; Valle, J.W.; McNamara, M.G. Selection of Chemotherapy in Advanced Poorly Differentiated Extra-Pulmonary Neuroendocrine Carcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlader, N.; Noone, A.; Krapcho, M.; Garshell, J.; Miller, D.; Altekruse, S. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www. seer. cancer. gov) SEER* Stat Database: Incidence-SEER 18 Regs Research Data+ Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2015 Sub (2000-2013)<Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment>-Linke. 2015. Rita population adjustment¿ e Linke 2015.

- Sorbye, H.; Welin, S.; Langer, S.W.; Vestermark, L.W.; Holt, N.; Osterlund, P.; Dueland, S.; Hofsli, E.; Guren, M.; Ohrling, K. Predictive and prognostic factors for treatment and survival in 305 patients with advanced gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma (WHO G3): the NORDIC NEC study. Annals of oncology 2013, 24, 152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Machida, N.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kasuga, A.; Takahashi, H.; Sudo, K.; Nishina, T.; Tobimatsu, K.; Ishido, K.; Furuse, J.; Boku, N. Multicenter retrospective analysis of systemic chemotherapy for advanced poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the digestive system. American Society of Clinical Oncology: 2012.

- Bernick, P.; Klimstra, D.; Shia, J.; Minsky, B.; Saltz, L.; Shi, W.; Thaler, H.; Guillem, J.; Paty, P.; Cohen, A. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Diseases of the colon & rectum 2004, 47, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.D.; Reidy, D.L.; Goodman, K.A.; Shia, J.; Nash, G.M. A retrospective review of 126 high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2014, 21, 2956–2962. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, H.; Aotake, T.; Horiuchi, T.; Chiba, Y.; Imamura, Y.; Tanaka, K. Small cell carcinoma of the gallbladder: a case report and review of 53 cases in the literature. Hepato-gastroenterology 2001, 48, 1588–1593. [Google Scholar]

- Strosberg, J.R.; Cheema, A.; Weber, J.; Han, G.; Coppola, D.; Kvols, L.K. Prognostic validity of a novel American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Classification for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2011, 29, 3044–3049. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Capdevila, J.; Crespo-Herrero, G.; Díaz-Pérez, J.; Del Prado, M.M.; Orduña, V.A.; Sevilla-García, I.; Villabona-Artero, C.; Beguiristain-Gómez, A.; Llanos-Muñoz, M. Incidence, patterns of care and prognostic factors for outcome of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs): results from the National Cancer Registry of Spain (RGETNE). Annals of oncology 2010, 21, 1794–1803. [Google Scholar]

- Marabelle, A.; Le, D.T.; Ascierto, P.A.; Di Giacomo, A.M.; De Jesus-Acosta, A.; Delord, J.-P.; Geva, R.; Gottfried, M.; Penel, N.; Hansen, A.R. Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch repair–deficient cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2020, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frizziero, M.; Kilgour, E.; Simpson, K.L.; Rothwell, D.G.; Moore, D.A.; Frese, K.K.; Galvin, M.; Lamarca, A.; Hubner, R.A.; Valle, J.W.; et al. Expanding Therapeutic Opportunities for Extrapulmonary Neuroendocrine Carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research 2022, 28, 1999–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median Age (Range) | 60.14 (29-82) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0 | 82.8 |

| 1 | 10.3 |

| 2 | 6.9 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 48.3 |

| Male | 51.7 |

| Smoking | |

| Yes | 31.0 |

| No | 69.0 |

| Stage at first diagnosis | |

| Localized | 10.3 |

| Locoregional | 34.5 |

| Metastatic | 55.2 |

| Ki-67 | |

| >80 | 75.0 |

| 60–80 | 25.0 |

| Surgery | |

| Yes | 31.0 |

| No | 69.0 |

| Curative RT | |

| Yes | 39.3 |

| No | 58.6 |

| Concurrent CRT | |

| Yes | 25.0 |

| No | 75.0 |

| Liver-Directed Therapy | |

| Yes | 6.9 |

| No | 93.1 |

| 1st Line Chemotherapy | |

| Cisplatin+Etoposide | 51.7 |

| Carboplatin+Etoposide | 48.3 |

| 2nd Line Chemotherapy | |

| Cisplatin+Etoposide | 6.9 |

| Irinotecan | 17.2 |

| Paclitaxel | 3.4 |

| CAPOX | 3.4 |

| 3rd Line Therapy | |

| Chemotherapy | 34.5 |

| Immunotherapy | 10.3 |

| CAPOX: Oxaliplatin plus capecitabine RT: Radiotherapy CRT: Chemoradiotherapy ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status | |

| Therapy Line | N (%) |

|---|---|

| 1st Line | |

| Complete Response (CR) | 12 (42.9%) |

| Partial Response (PR) | 11 (39.3%) |

| Progressive Disease (PD) | 5 (17.9%) |

| Objective Response Rate (ORR) | %82.1 |

| 2nd Line | |

| Partial Response (PR) | 3 (10.3%) |

| Stable Disease (SD) | 1 (3.4%) |

| Progressive Disease (PD) | 7 (24.1%) |

| 3rd Line | |

| Partial Response (PR) | 0(0%) |

| Stable Disease (SD) | 2 (6.9%) |

| Progressive Disease (PD) | 3 (10.3%) |

| Immunotherapy | |

| Partial Response (PR) | 0(0%) |

| Stable Disease (SD) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Progressive Disease (PD) | 2 (66.6%) |

| Variable | PFS Duration (Median, Months) | Univariate p-Value | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | Multivariate p-Value |

| Gender | 0.747 | - | - | |

| Male | 8.3 mo. | |||

| Female | 8 mo. | |||

| Stage | 0.442 | - | - | |

| Local | 24.2 mo. | |||

| Locoregional | 8.1 mo. | |||

| Metastatic | 8 mo. | |||

| ECOG-PS | 0.005 | 1.452 (0.537–3.926) | 0.463 | |

| ECOG PS-0 | 8.1 mo. | |||

| ECOG PS-1 | 8.3 mo. | |||

| ECOG PS-2 | 2.1 mo. | |||

| Smoking Status | 0.539 | - | - | |

| Non-smoker | 8.1 mo. | |||

| Smoker | 7.1 mo. | |||

| Surgical History | 0.02 | 7.291 (1.212–43.862) | 0.03 | |

| No Surgery | 8 mo. | |||

| Surgery | NR | |||

| Concurrent CRT | 0.847 | - | - | |

| No Concurrent CRT | 8.3 mo. | |||

| Concurrent CRT | 8.1 mo. | |||

| First-line CT (Cis-Eto vs Carbo-Eto) | 0.182 | - | - | |

| Cis-Eto: | 13.1 mo. | |||

| Carbo-Eto | 7.1 mo. | |||

| Ki-67 | 0.032 | NE | 0.0 | |

| Ki67<80 | 36 mo. | |||

| Ki-67 ≥ 80: 8 mo. | 8 mo. | |||

| CT: Chemotherapy RT: Radiotherapy CRT: Chemoradiotherapy Cis-Eto: Cisplatin etoposide Carbo-Eto: Carboplatin Etoposide ECOG-PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status NR: Not Reached NE: Not Estimable | ||||

| Variable | OS Duration (Median, Months) | Univariate p-Value | Multivariate Exp(B) | Multivariate p-Value |

| Gender | 0.451 | - | - | |

| Male | 11.8 mo. | |||

| Female | 26.4 mo. | |||

| Stage | 0.520 | - | - | |

| Local | 52.2 mo. | |||

| Locoregional | 12.4 mo. | |||

| Metastatic | 11.8 mo. | |||

| ECOG-PS | 0.448 | 1.106 | 0.825 | |

| ECOG PS-0 | 13.9 mo. | |||

| ECOG PS-1 | NR | |||

| ECOG PS-2 | 6.5 mo. | |||

| Smoking Status | 0.418 | - | - | |

| Non-smoker | 26.4 mo. | |||

| Smoker | 11.7 mo. | |||

| Surgical History | 0.385 | 1.324 | 0.705 | |

| No Surgery | 11.8 mo. | |||

| Surgery | 26.4 mo. | |||

| Concurrent CRT | 0.581 | - | - | |

| No Concurrent CRT | 14.1 mo. | |||

| Concurrent CRT | 14.1 mo. | |||

| First-line CT (Cis-Eto vs Carbo-Eto) | 0.180 | 0.508 | 0.331 | |

| Cis-Eto: | 26.4 mo. | |||

| Carbo-Eto | 11.7 mo. | |||

| Ki-67 | 0.959 | 1.405 | 0.645 | |

| Ki67<80 | 26.4 mo. | |||

| Ki-67 ≥ 80: 8 mo. | 11.8 mo. | |||

| CT: Chemotherapy RT: Radiotherapy CRT: Chemoradiotherapy Cis-Eto: Cisplatin etoposide Carbo-Eto: Carboplatin Etoposide ECOG-PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status NR: Not Reached NE: Not Estimable | ||||

| Reference | No. of Patients | Cohort | Primary Site | Median PFS (months) | Median OS (months) | 2-Year Survival (%) | 3-Year Survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yao 2008[5] | 2027 | All NEC (Including Lung) | Mixed | - | 5 (4.5-5.5) | - | - |

| SEER Program 2013[24] | 1389 | GEP-NEC | GEP | - | 5 (4.7-5.4) | 11 | 8 |

| Sorbye 2013[25] | 252 | GEP-NEC (Chemotherapy Treated) | GEP | - | 11 (9.4-12.6) | 14 | 9.5 |

| Sorbye 2013[25] | 53 | GEP-NEC (No Treatment) | GEP | - | 1 (0.3-1.8) | - | - |

| Machida 2012[26] | 258 | GEP-NEC (Chemotherapy Treated) | GEP | - | 11.5 | - | - |

| Bernick 2004[27] | 38 | Colorectal Small Cell NEC | Colon & Rectum | - | 10.5 (6.7-19) | 26 | 13 |

| Smith 2013[28] | 126 | Colorectal NEC | Colon & Rectum | - | 13 | 5 | - |

| Fujii 2001[29] | 53 | Gallbladder, Small Cell NEC (Chemotherapy Treated) | Gallbladder | - | 8 | 0 | - |

| Strosberg 2011[30] | 32 | Pancreatic NEC | Pancreas | - | 21 | - | - |

| Garcia-Carbonero 2010[31] | 85 | GEP-NEC | GEP | - | 1.7 | - | - |

| Celik et al. (2022)[22] | 47 | EP-NEC (Chemotherapy Treated) | Stomach (27.6%), Unknown Primary (23.4%), Pancreas (10.6%) | 5.83 (4.46-7.20) | 13.6 (9.01-18.18) | - | - |

| NEC, Neuroendocrin carcinoma CI, confidence interval GEP-NEC, gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).