Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

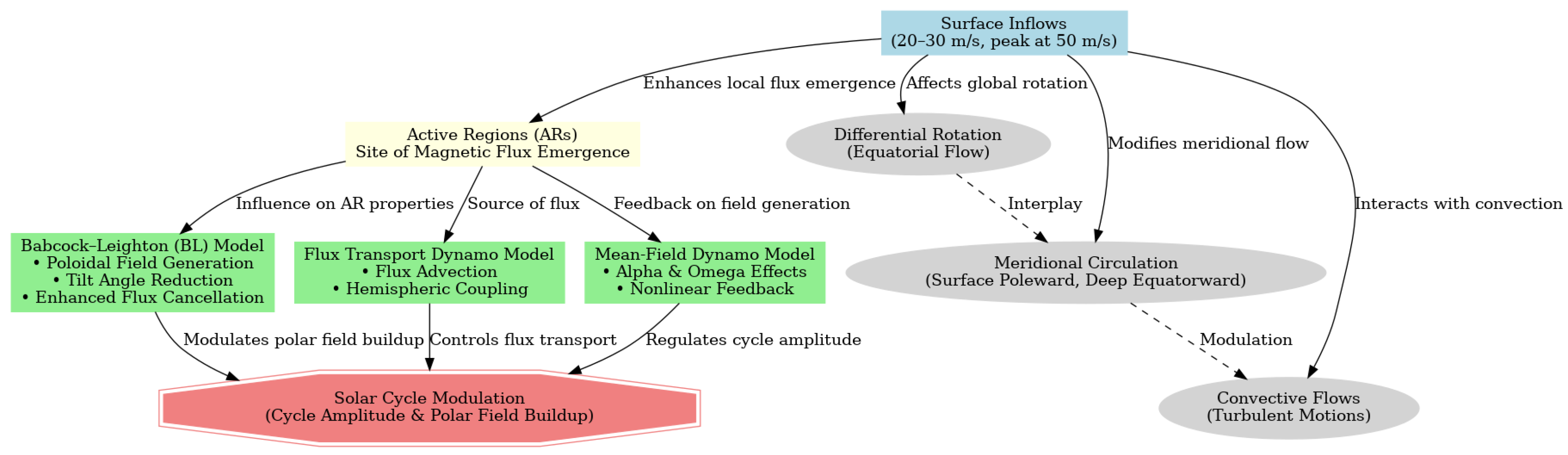

- Babcock-Leighton (BL) Dynamo Modelswhich explain the solar cycle through the generation of the poloidal magnetic field near the solar surface and the toroidal field in the solar interior. The coupling of these fields introduces a memory effect, allowing for short-term predictions of solar activity, [16]. Generating a poloidal field from the toroidal field is considered a nonlinear process, [17]; the nonlinear mechanisms included in the models are tilt quenching, latitude quenching and surface inflows (see Figure 3 in [18]. The accuracy of these models can be affected by turbulent pumping, which degrades the memory of the dynamo, limiting long-term predictions. Additionally, the depth variation of equatorward flow and strong turbulent diffusivity pose challenges, [19]. The recent development of the model was described in [18].

- Flux Transport Dynamo Models focus on the transport of magnetic flux by large-scale flows, such as differential rotation and meridional circulation. They are particularly useful for explaining the cyclic nature of solar magnetic activity, [20]. The emergence and growth of the flux transport dynamo model of the sunspot cycle were described in [21]. Recent advancements include three-dimensional non-kinematic simulations, which incorporate the emergence of BMRs and their tilt angles, influenced by the Coriolis force, [22]. These models of flux transport dynamo and meridional circulation in the Sun and stars were reviewed by [23].

- Mean-Field Dynamo Models use mean-field electrodynamics to describe the generation of magnetic fields through the -effect (helical turbulence) and -effect (differential rotation). They can reproduce irregularities in solar cycles, including grand minima [24]. Incorporating additional turbulent induction effects, such as the effect, can improve the agreement with observed solar cycle periods and magnetic field concentrations at low latitudes [25]. These models and how inflows influence the dynamo processes are summarized in Figure 1.

2. Background

3. Current Understanding and Open Questions

- Uncertainty in the Role of Inflows: The impact of large-scale inflows around active regions on the global magnetic field and the solar cycle is still debated. While observational evidence suggests that these flows influence flux transport, their precise role in modulating solar activity remains unclear.

- Observational Limitations: Helioseismology provides essential insights into the Sun’s internal dynamics, but its spatial and temporal resolution constraints limit our ability to resolve fine-scale features crucial for dynamo modelling. Additionally, direct observations of subsurface flows and deep-seated magnetic fields remain a major challenge.

- Modelling Complexities: Different dynamo models—including Babcock-Leighton, flux transport, and mean-field approaches—offer varied interpretations of solar cycle evolution. However, integrating multi-scale processes, such as turbulence, differential rotation, and meridional circulation, into a unified framework remains an open challenge.

- Cycle Predictability: Despite improvements in dynamo models and data assimilation techniques, predicting solar cycles remains an imperfect science. Discrepancies between different forecasting methods and observed cycle variability highlight gaps in our understanding of long-term solar activity [56].

- Advancing Helioseismic Observations: Higher-resolution helioseismic techniques and next-generation space missions will provide more detailed measurements of subsurface flows, improving constraints on dynamo models.

- Data-Driven Dynamo Modelling: The integration of observational data with advanced computational models, including machine learning approaches, can refine predictions of solar cycles and magnetic field evolution.

- Enhanced Global and Local Dynamo Simulations: Future models must incorporate small-scale turbulent processes, improved boundary conditions, and multi-layer interactions to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the solar magnetic cycle.

- Interdisciplinary Approaches: Insights from stellar magnetism, geodynamo studies, and plasma physics could offer new perspectives on solar dynamo mechanisms.

- Long-Term Solar Activity Studies: Expanding databases with historical solar cycle reconstructions and comparisons with stellar analogs may improve our understanding of extreme solar events and long-term cycle variations.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR | Active Regions |

| BL | Babcock-Leighton |

| BMR | Bipolar Magnetic Region |

| CME | Coronal Mass Ejection |

| SDO | Solar Dynamics Observatory |

| HMI | Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager |

References

- Jiang, J.; Cao, J. Predicting solar surface large-scale magnetic field of Cycle 24. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 2018, 176, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, S.; Fournier, A.; Pinheiro, K.J.; Aubert, J. A mean-field Babcock-Leighton solar dynamo model with long-term variability. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 2014, 86, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Q.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Z.F. Sunspot tilt angles revisited: Dependence on the solar cycle strength. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2021, 653, A27. [Google Scholar]

- Gizon, L.; Duvall, T.; Larsen, R. Probing surface flows and magnetic activity with time-distance helioseismology. In Proceedings of the Symposium-International Astronomical Union; Cambridge University Press, 2001; Volume 203, pp. 189–191. [Google Scholar]

- González Hernández, I.; Kholikov, S.; Hill, F.; Howe, R.; Komm, R. Subsurface meridional circulation in the active belts. Solar Physics 2008, 252, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Cameron, R.H.; Schmitt, D.; Schuessler, M. The solar magnetic field since 1700-I. Characteristics of sunspot group emergence and reconstruction of the butterfly diagram. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2011, 528, A82. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, R.; Schüssler, M. Are the strengths of solar cycles determined by converging flows towards the activity belts? Astronomy & Astrophysics 2012, 548, A57. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Işik, E.; Cameron, R.; Schmitt, D.; Schüssler, M. The effect of activity-related meridional flow modulation on the strength of the solar polar magnetic field. ApJ 2010, 717, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizon, L. Helioseismology of time-varying flows through the solar cycle. Solar Physics 2004, 224, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R.; Schüssler, M. Changes of the solar meridional velocity profile during cycle 23 explained by flows toward the activity belts. The Astrophysical Journal 2010, 720, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Belda, D.; Cameron, R.H. Inflows towards active regions and the modulation of the solar cycle: A parameter study. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2017, 597, A21. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, M.; Lemerle, A.; Charbonneau, P. Impact of nonlinear surface inflows into activity belts on the solar dynamo. Journal of Space Weather and Space Climate 2020, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschling, N.; Schunker, H.; Birch, A.; Löptien, B.; Gizon, L. Evolution of solar surface inflows around emerging active regions. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2021, 652, A148. [Google Scholar]

- Komm, R.; Howard, R.; Harvey, J. Meridional flow of small photospheric magnetic features. Solar Physics 1993, 147, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, D.H.; Rightmire, L. Variations in the Sun’s meridional flow over a solar cycle. Science 2010, 327, 1350–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandy, D.; Karak, B.B. Forecasting the solar activity cycle: new insights. Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union 2012, 8, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeates, A.R.; Cheung, M.C.; Jiang, J.; Petrovay, K.; Wang, Y.M. Surface flux transport on the Sun. Space Science Reviews 2023, 219, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karak, B.B. Recent Developments in the Babcock–Leighton Solar Dynamo Theory. Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union 2023, 19, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. What drives the solar magnetic cycle? Chin Sci Bull 2016, 61, 2973–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhuri, A.R. The origin of the solar magnetic cycle. Pramana 2011, 77, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhuri, A.R. The emergence and growth of the flux transport dynamo model of the sunspot cycle. Reviews of Modern Plasma Physics 2023, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekki, Y.; Cameron, R.H. Three-dimensional non-kinematic simulation of the post-emergence evolution of bipolar magnetic regions and the Babcock-Leighton dynamo of the Sun. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2023, 670, A101. [Google Scholar]

- Hazra, G.; Nandy, D.; Kitchatinov, L.; Choudhuri, A.R. Mean field models of flux transport dynamo and meridional circulation in the Sun and stars. Space Science Reviews 2023, 219, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchatinov, L. The solar dynamo: Inferences from observations and modeling. Geomagnetism and Aeronomy 2014, 54, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipin, V. V. .; Seehafer, N.. Stellar dynamos with Ω×J effect. A&A 2009, 493, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados-Hernández, N.; Vargas-Domínguez, S. Analysis of magnetic polarities in active regions for the prediction of solar flares. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 2020, 44, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, H.; Tripathi, D. Chapter 7: Active Region Diagnostics. In Physics of the sun and its atmosphere; Physics of the Sun and Its Atmosphere, World Scientific, 2008; pp. 127–150.

- Vlahos, L. Solar and Stellar Active Regions A Cosmic Laboratory for the study of Complexity. In Proceedings of the Chaos in Astronomy: Conference 2007; Springer Science & Business Media, 2009; p. 423. [Google Scholar]

- Zaffar, A.; Abbas, S.; Ansari, M.R.K. A Study of Largest Active Region AR12192 of 24th Solar Cycle Using Fractal Dimensions and Mathematical Morphology. Solar System Research 2020, 54, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, K.; Cañedo, V.; Cabezas, D.; Buleje, Y. Sunspot characteristics of active regions NOAA 2268 and NOAA 2305. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing, 2018; Volume 1143, p. 012007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Hao, Q.; Chen, P. Statistical Analyses of Solar Prominences and Active Region Features in 304 Å Filtergrams Detected via Deep Learning. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2024, 272, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan-mei, C.; Si-qing, L.; Li-qin, S. Automatic Recognition of Solar Active Regions Based on Real-time SDO/HMI Full-disk Magnetograms. Chinese Astronomy and Astrophysics 2021, 45, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lin, G.; Deng, Y. A real-time prediction system for solar weather based on magnetic nonpotentiality (I). In Proceedings of the Software and Cyberinfrastructure for Astronomy IV; SPIE, 2016; Volume 9913, pp. 1410–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Guesmi, B.; Daghrir, J.; Moloney, D.; Ortega, C.U.; Furano, G.; Mandorlo, G.; Hervas-Martin, E.; Espinosa-Aranda, J.L. EoFNets: EyeonFlare Networks to predict solar flare using Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN). In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT); IEEE, 2024; pp. 1120–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Chumak, O.; Zhang, H.Q. Integrated characteristics of the radial magnetic field in solar active regions during quiet and flare-productive phases of their evolution. Astronomy reports 2005, 49, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teweldebirhan, K.; Miesch, M.; Gibson, S. Inflows Towards Bipolar Magnetic Active Regions and Their Nonlinear Impact on a Three-Dimensional Babcock–Leighton Solar Dynamo Model. Solar Physics 2024, 299, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R.; Jiang, J.; Schmitt, D.; Schüssler, M. Surface flux transport modeling for solar cycles 15–21: effects of cycle-dependent tilt angles of sunspot groups. The Astrophysical Journal 2010, 719, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talafha, M.H.; Petrovay, K.; Opitz, A. Effect of Nonlinear Surface Inflows into Activity Belts on Solar Cycle Modulation. Solar Physics In press. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, R.; Jiang, J.; Schüssler, M.; Gizon, L. Physical causes of solar cycle amplitude variability. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2014, 119, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlburt, N.; DeRosa, M. On the stability of active regions and sunspots. The Astrophysical Journal 2008, 684, L123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, D.; Miesch, M.; Guerrero, G.; Charbonneau, P. Meridional circulation dynamics in a cyclic convective dynamo. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2017, 607, A120. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, S.S.; Sun, X.; Zhao, J. Removal of active region inflows reveals a weak solar cycle scale trend in the near-surface meridional flow. The Astrophysical Journal 2023, 950, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Verma, M.; Denker, C.; Zhao, J.; Wang, H. Study of Global Photospheric and Chromospheric Flows Using Local Correlation Tracking and Machine Learning Methods I: Methodology and Uncertainty Estimates. Solar Physics 2023, 298, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, S.; Cameron, R.; Gizon, L. A Babcock-Leighton dynamo model of the Sun incorporating toroidal flux loss and the helioseismically inferred meridional flow. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2023, 680, A42. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhuri, A.R. The meridional circulation of the Sun: Observations, theory and connections with the solar dynamo. Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy 2021, 64, 239601. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra-Kraev, U.; Thompson, M.; Woodard, M. Meridional flow measurements with statistical waveform analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of SOHO 18/GONG 2006/HELAS I, Beyond the spherical Sun, 2006, Vol. 624.

- Pipin, V.; Kosovichev, A. The mean-field solar dynamo with a double cell meridional circulation pattern. The Astrophysical Journal 2013, 776, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, S.; Nandy, D. A proposed paradigm for solar cycle dynamics mediated via turbulent pumping of magnetic flux in Babcock–Leighton-type solar dynamos. The Astrophysical Journal 2016, 832, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, G.; Dal Pino, E.d.G. Turbulent magnetic pumping in a Babcock-Leighton solar dynamo model. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2008, 485, 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Jouve, L.; Nandy, D. A 3D kinematic Babcock Leighton solar dynamo model sustained by dynamic magnetic buoyancy and flux transport processes. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2019, 623, A54. [Google Scholar]

- Roudier, T.; Švanda, M.; Malherbe, J.; Ballot, J.; Korda, D.; Frank, Z. Photospheric downflows observed with SDO/HMI, HINODE, and an MHD simulation. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2021, 647, A178. [Google Scholar]

- Kupka, F.; Robinson, F. On the effects of coherent structures on higher order moments in models of solar and stellar surface convection. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2007, 374, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, G. An Argument in Favor of Magnetic Polarity Reversals Due to Heat Flux Variations in Fully Convective Stars and Planets. The Astrophysical Journal 2022, 938, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, E. A mechanism for the dependence of sunspot group tilt angles on cycle strength. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2015, 813, L13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaki, H.; Hotta, H. Detection of solar internal flows with numerical simulation and machine learning. Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan 2024, 76, L33–L38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovay, K. Predicting Solar Cycles with a Parametric Time Series Model. Universe 2024, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).