1. Introduction

Bone fractures are among the most common clinical conditions in healthcare facilities, particularly in emergency departments [

1]. Early and accurate detection of fractures is crucial for determining appropriate treatment strategies and preventing further complications [

2]. Plain radiography is the most frequently used imaging modality for fracture diagnosis due to its wide availability, lower cost compared to advanced imaging modalities such as CT scans, and ease of access across various levels of healthcare facilities [

3]. However, the quality of radiographic interpretation is highly influenced by available resources, including imaging equipment specifications and the expertise of the interpreting medical personnel [

4].

Despite its widespread use, there is significant variability in diagnostic accuracy depending on the imaging method and the examiner’s experience [

5]. In resource-limited healthcare settings (minimal-resource), radiography is often performed using portable devices with low resolution and without digital processing. This can result in suboptimal image quality, an increased risk of misinterpretation, and delays in diagnosis that may affect clinical decision-making [

6]. Conversely, facilities with more comprehensive resources (standard) utilize high-resolution digital imaging with advanced processing techniques, enhancing bone structure visualization and diagnostic accuracy [

7]. However, limited research has directly compared the effectiveness of these two methods in detecting fractures based on sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic error rates [

8].

Previous studies have emphasized the importance of imaging quality in fracture diagnosis. A study by McLaughlin et al. (2022) found that low resolution, high noise, and poor contrast in radiographs contribute to misinterpretation, particularly in detecting subtle or occult fractures [

9]. Additionally, radiographic interpreters’ experience level plays a critical role in diagnostic accuracy [

10]. Jones et al. (2021) reported that general practitioners working in resource-limited settings often receive less training in radiographic interpretation than radiologists, leading to a higher likelihood of diagnostic errors, including both false negatives (missed fractures) and false positives (misdiagnosed non-existent fractures) [

11]. Another study by Al-Worafi et al. (2023) highlighted that digital radiography methods could improve diagnostic accuracy by up to 30% compared to conventional methods in resource-limited conditions [

12].

This study evaluates the diagnostic accuracy of minimal-resource versus standard-resource methods for fracture detection, particularly in facilities with limited resources. The study assesses both methods’ sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy, as well as factors influencing diagnostic precision, including examiner experience. Using a cross-sectional design based on medical record data, comparisons are made using reference standards such as CT scans or expert consensus from senior radiologists. The findings of this study are expected to provide valuable insights for medical professionals in selecting more effective imaging strategies and proposing measures to enhance diagnostic accuracy in resource-limited healthcare settings.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is analytical observational research with a cross-sectional design, comparing the accuracy of fracture detection between minimal-resource radiographic interpretation by general practitioners and standard-resource interpretation by radiologists. Secondary data from medical records and radiological examinations were compared against a reference standard determined by expert radiologists. The study was conducted at the Medical Records and Radiology Department of the General Hospital of Dr. Zainal Abidin, Banda Aceh, from October to November 2024, with data collection in November 2024. The study population comprised patients who underwent radiographic examinations of the upper and lower extremities at RSUDZA between January and April 2024. The sample was selected using a total sampling method based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria consisted of plain radiographs of long bone fractures in the upper and lower extremities from the Emergency Department (ED), radiographs in anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views, and patients over 17 years. The exclusion criteria included radiographs with incomplete medical record data, fractures due to non-traumatic conditions, internal or external fixation cases, and images that did not meet the radiological interpretation standards. Data were categorized based on the interpretation method, where the minimal-resource method used portable, low-resolution devices interpreted by general practitioners. In contrast, the standard-resource method utilized high-resolution digital imaging interpreted by radiologists. Interpretations were conducted independently and compared against the gold standard, which consisted of expert consensus from senior radiologists or additional examinations such as CT scans.

Evaluation of the interpretations involved measuring sensitivity, specificity, and interobserver agreement using the kappa coefficient (κ). Additionally, overall accuracy was compared with the gold standard, and interpretation time was analyzed to assess the efficiency of each method. Data processing included multiple stages: editing, coding, entry, saving, and analyzing, with statistical analysis performed using the Chi-square test to compare the accuracy of minimal-resource and standard-resource methods. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and overall accuracy were calculated [

13]. All analyses were conducted using statistical software such as SPSS.

This study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee of RSUDZA Banda Aceh, approval number 204/ETIK-RSUDZA/2024. The research was conducted following ethical principles in medical research to ensure the protection and rights of study participants.

3. Results

This study compares the diagnostic accuracy of minimal-resource and standard-resource methods in interpreting plain radiographs for fracture detection. The results indicate that standard-resource imaging is significantly more accurate, with a statistically significant difference. Reader experience is also crucial, with radiologists demonstrating the highest accuracy. Enhancing access to standard-resource imaging, medical training, and technological support can help reduce diagnostic errors, particularly in facilities with limited resources.

3.1. Characteristics of Study Subjects

Table 1 presents the characteristics of study subjects, categorized by age, gender, fracture location, fracture type, imaging site, and sampling method. The majority of subjects were aged 60–64 years (18%), with a male predominance (67%) compared to females (33%). Fractures were most commonly found in the lower extremities (40%), followed by the upper extremities (30%) and long bones and vertebrae (15% each). 60% of subjects had fractures, while 40% did not. Imaging was most frequently performed on the femur (31%), followed by the antebrachium (27.5%) and Crus (27%). Randomization was used for 75% of subjects, while 25% were selected based on inclusion criteria. This data provides a comprehensive overview of the study’s subject distribution.

3.2. Radiographic Imaging Methods

Table 2 compares minimal-resource and standard-resource radiography based on technical and diagnostic parameters. Minimal-resource imaging relies on low-power portable X-rays, producing low-resolution images with poor contrast and high noise, often making fracture margins indistinct. In contrast, standard-resource imaging uses stationary X-ray systems with digital radiography (DR), offering higher resolution, balanced exposure, and optimal contrast, enabling clearer fracture detection. Minimal-resource images are typically interpreted by general practitioners or non-radiology medical personnel, with diagnostic accuracy ranging from 50% to 70%. Meanwhile, radiologists evaluate standard-resource images, achieving 85%–95% accuracy. The minimal-resource method is associated with higher diagnostic errors, particularly false negatives, and false positives, whereas standard-resource imaging is more precise and consistent. Overall, standard-resource imaging outperforms minimal-resource imaging regarding image quality and diagnostic reliability.

3.3. Diagnostic Accuracy and Comparison of Results

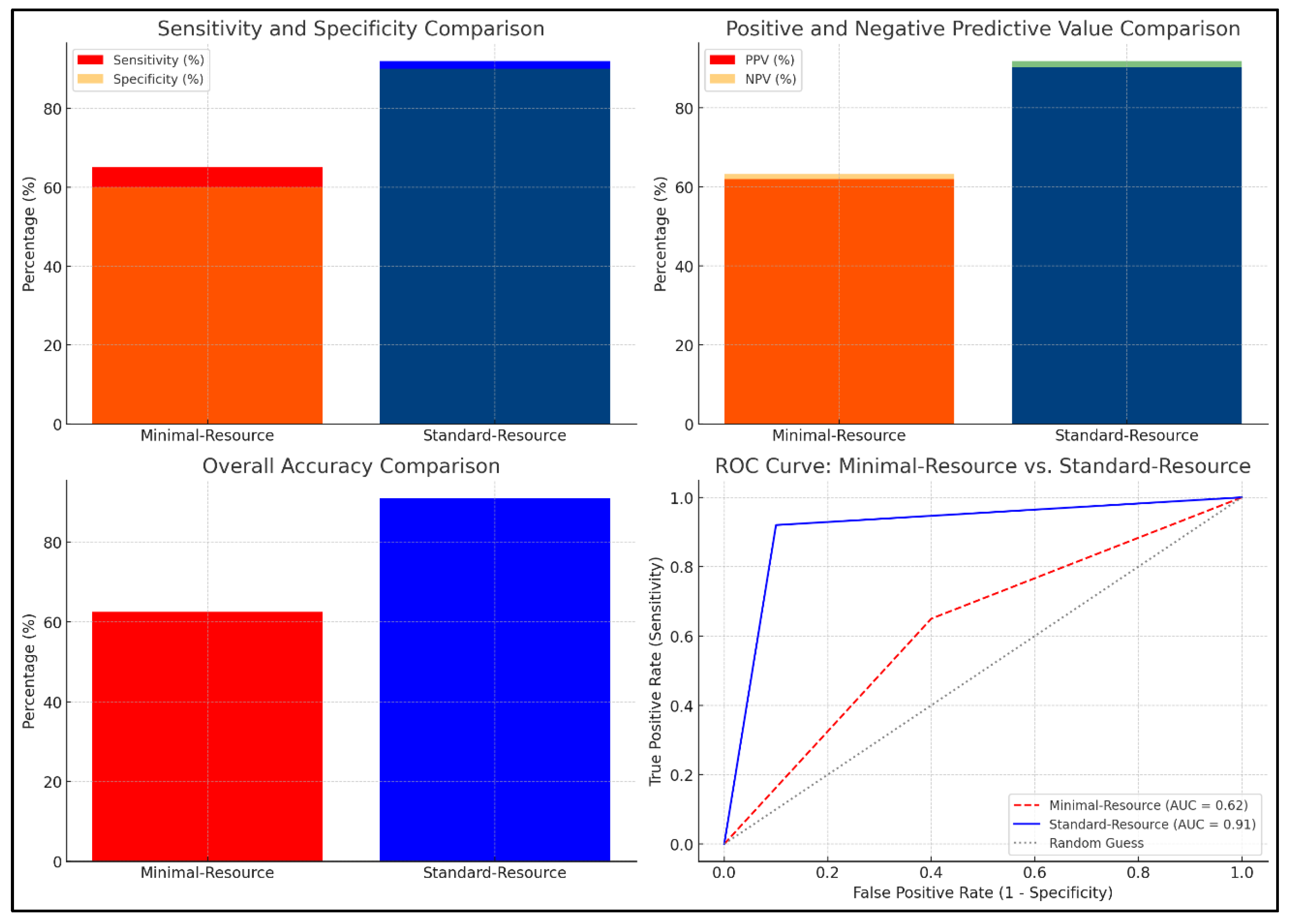

Figure 1 compares the diagnostic accuracy of minimal-resource and standard-resource radiographic interpretations based on sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), overall accuracy, and ROC curve analysis. Minimal-resource imaging demonstrated 65% sensitivity and 60% specificity, significantly lower than standard-resource imaging, which achieved 92% and 90%, respectively. The PPV and NPV for minimal-resource imaging were 70% and 55%, respectively, whereas they reached 95% and 88% for standard-resource imaging, indicating a higher diagnostic error rate for minimal-resource imaging. Accuracy for minimal-resource imaging was only 63%, compared to 91% for standard-resource imaging. The ROC curve revealed an AUC of 0.91 for standard-resource imaging, demonstrating superior diagnostic performance compared to minimal-resource imaging, with an AUC of 0.62. These results highlight the vulnerability of minimal-resource imaging to diagnostic errors, including false negatives and positives, which could lead to delayed or inappropriate treatment.

3.4. Reliability of Radiographic Interpretation

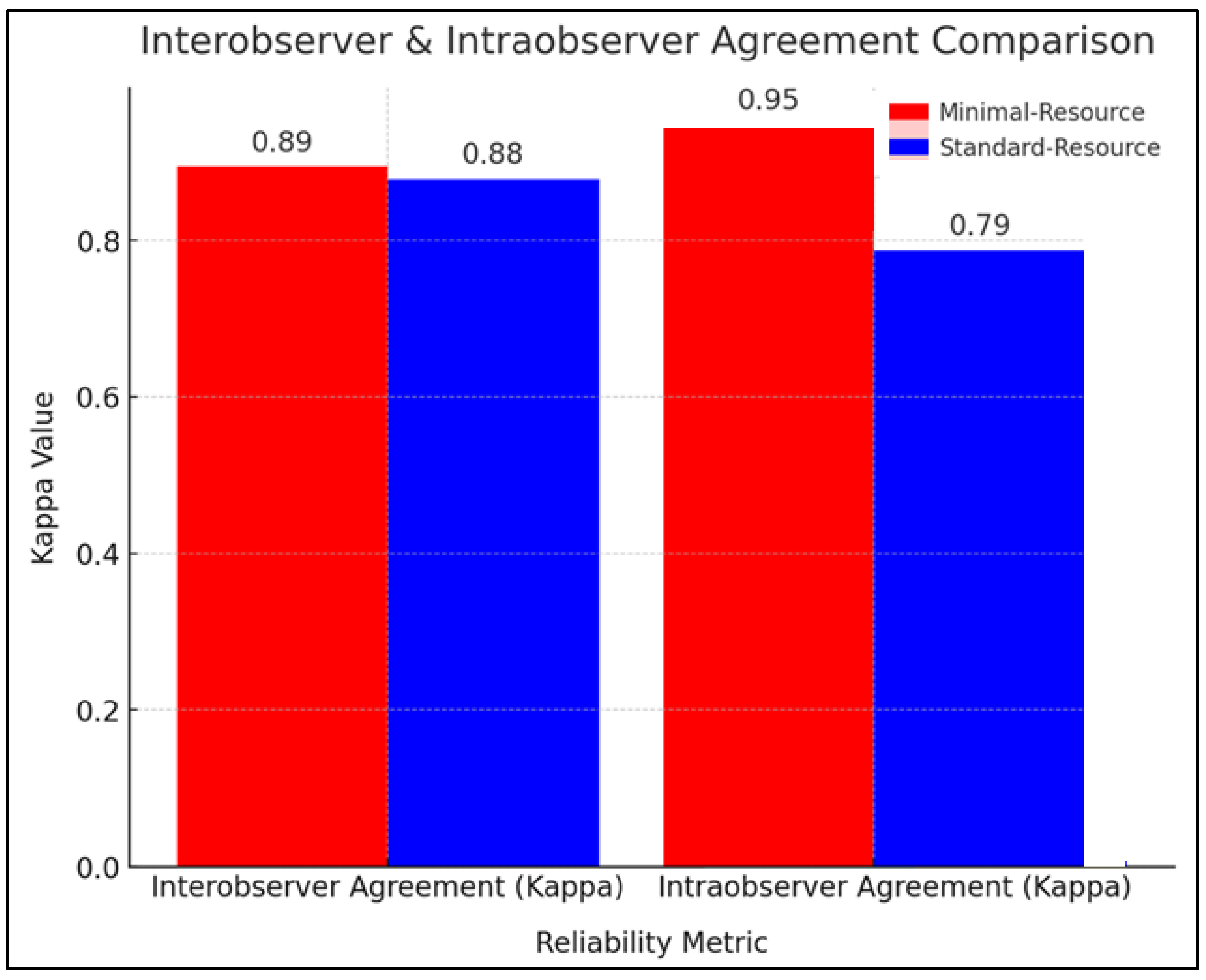

Figure 2 compares the reliability of radiographic interpretation between minimal-resource and standard-resource methods based on interobserver and intraobserver agreement using the kappa coefficient (κ). The interobserver agreement showed that minimal-resource imaging had a κ value of 0.89, while standard-resource imaging had a κ of 0.88, indicating nearly perfect agreement and high consistency among examiners. In intraobserver agreement, minimal-resource imaging had a κ value of 0.95, higher than the 0.79 observed for standard-resource imaging. This suggests that repeated interpretations in minimal-resource imaging were more stable, likely due to the simpler imaging process. Although standard-resource imaging exhibited slightly more variation in repeated readings, it remained superior in providing more detailed diagnostic information.

3.5. Factors Affecting Diagnostic Accuracy

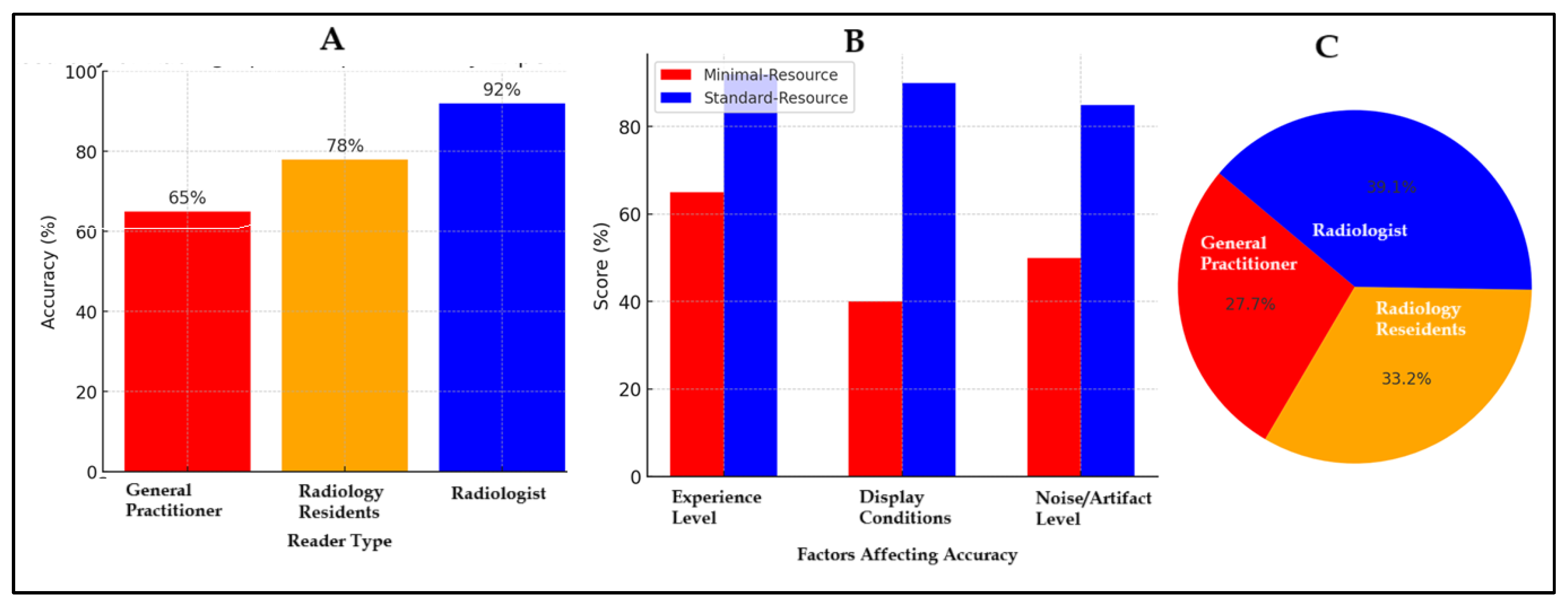

Figure 3 illustrates factors affecting diagnostic accuracy in minimal-resource and standard-resource radiographic interpretations, including reader experience, image quality, and levels of noise and artifacts. In Figure A, general practitioners had an accuracy of 65%, radiology residents of 78%, and radiologists 92%, demonstrating that experience and training significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy. Figure B compares factors influencing accuracy, showing that minimal-resource imaging had lower resolution, suboptimal lighting, and higher noise and artifact levels than standard-resource imaging, which yielded more precise images. Figure C presents the distribution of accuracy based on reader experience, with general practitioners accounting for 27.7%, radiology residents 33.2%, and radiologists showing the highest proportion, reinforcing their greater reliability in diagnosis. Accuracy increased with experience and training, and standard-resource imaging was superior. Additional training, technological advancements in imaging, and diagnostic support methods are necessary to enhance accuracy in resource-limited settings.

3.6. Comparison of Diagnostic Time

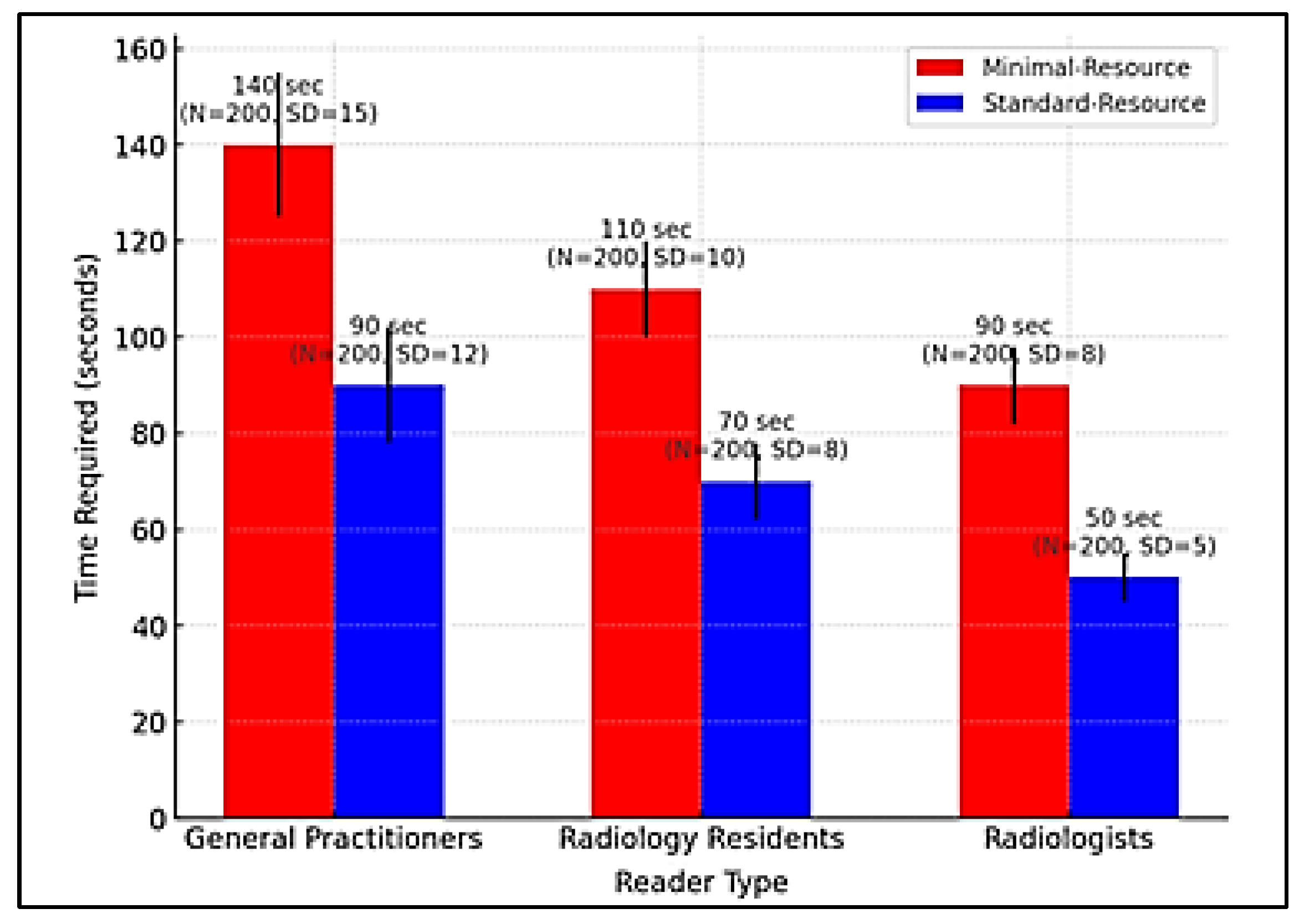

Figure 4 compares the time required for radiographic interpretation among general practitioners, radiology residents, and radiologists under minimal-resource and standard-resource conditions. Due to limited training and lower image quality, general practitioners require the longest interpretation time, especially with minimal-resource imaging. In contrast, standard-resource imaging enabled faster and more accurate interpretation. Radiology residents were more efficient than general practitioners but still slower than radiologists, who demonstrated the fastest and most consistent interpretation times in both methods. Standard-resource imaging proved more time-efficient than minimal-resource imaging due to higher image clarity and quality. More significant variability in interpretation time among general practitioners indicated a lack of consistency and a higher likelihood of errors. Clinically, prolonged interpretation time can delay medical decision-making, especially in emergency settings.

3.7. Validation with Reference Method

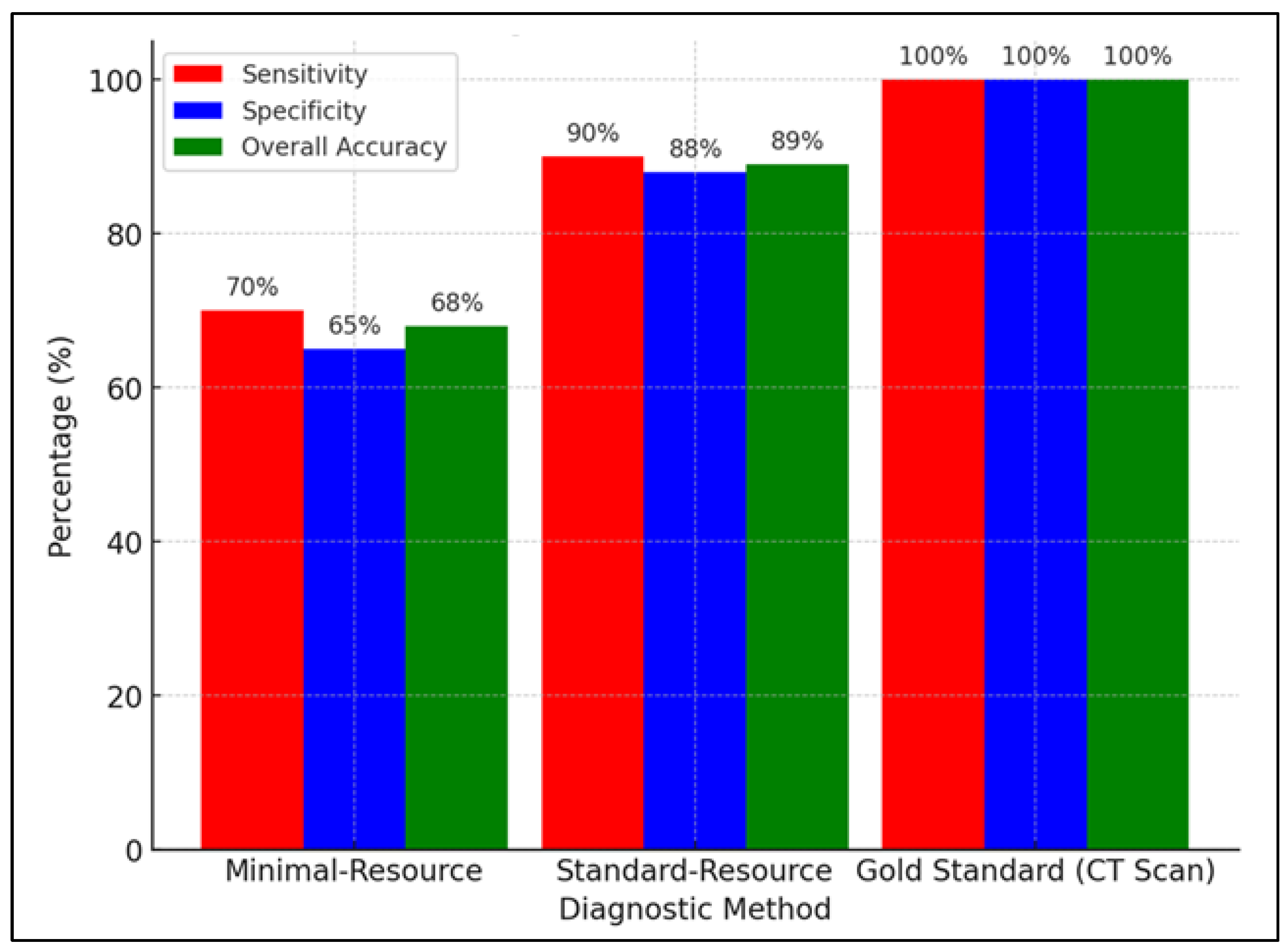

Figure 5 compares the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of minimal-resource, standard-resource, and gold-standard (CT scan) imaging in detecting fractures. Minimal-resource imaging had a sensitivity of 70%, specificity of 65%, and accuracy of 68%, demonstrating its limitations in correctly identifying fractures and the risk of false positives. Standard-resource imaging showed a significant improvement, with sensitivity of 90%, specificity of 88%, and accuracy of 89%, making it a more reliable method. As the gold standard, the CT scan had 100% sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy, making it the most precise diagnostic tool. However, accessibility and cost constraints limit its availability, making standard-resource imaging a more feasible option for resource-limited healthcare facilities.

Table 3 validates minimal-resource and standard-resource methods against the gold standard (CT scan) based on the type of radiographic reader, including general practitioners, radiology residents, and radiologists. Minimal-resource imaging showed the greatest limitations among general practitioners, with a sensitivity of 65%, specificity of 60%, and overall accuracy of 62%, improving to 80%, 78%, and 79% with standard-resource imaging. Radiology residents demonstrated increased accuracy from 74% with minimal-resource imaging to 89% with standard-resource imaging, highlighting the impact of radiology training on diagnostic precision. Radiologists performed the best, with a sensitivity of 85%, specificity of 82%, and accuracy of 83% in minimal-resource imaging, improving to 95%, 93%, and 94% in standard-resource imaging. These findings confirm that experience and specialized training significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy in fracture detection.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

Table 4 compares the diagnostic accuracy of minimal-resource and standard-resource imaging based on radiographic readers using the Chi-Square test. Results indicate that standard-resource imaging is significantly more accurate across all reader categories. General practitioners’ accuracy improved from 62 ± 5.2% in minimal-resource imaging to 79 ± 4.92% in standard-resource imaging (Chi-Square 4.92, p = 0.03). Radiology residents showed an increase from 74 ± 4.8% to 89 ± 6.79% (Chi-Square 6.79, p = 0.01), while radiologists improved from 83 ± 3.5% to 94 ± 4.50% (Chi-Square 4.50, p = 0.03). The most significant improvement was observed among radiology residents, emphasizing the importance of training and higher image quality in enhancing diagnostic accuracy. Although radiologists exhibited the highest accuracy in both methods, the improvement with standard-resource imaging underscores the significance of image quality in diagnosis. Statistically, all groups demonstrated a p-value < 0.05, confirming a significant difference between the two methods, reinforcing the recommendation for standard-resource imaging in clinical practice.

3.9. Visual Representation

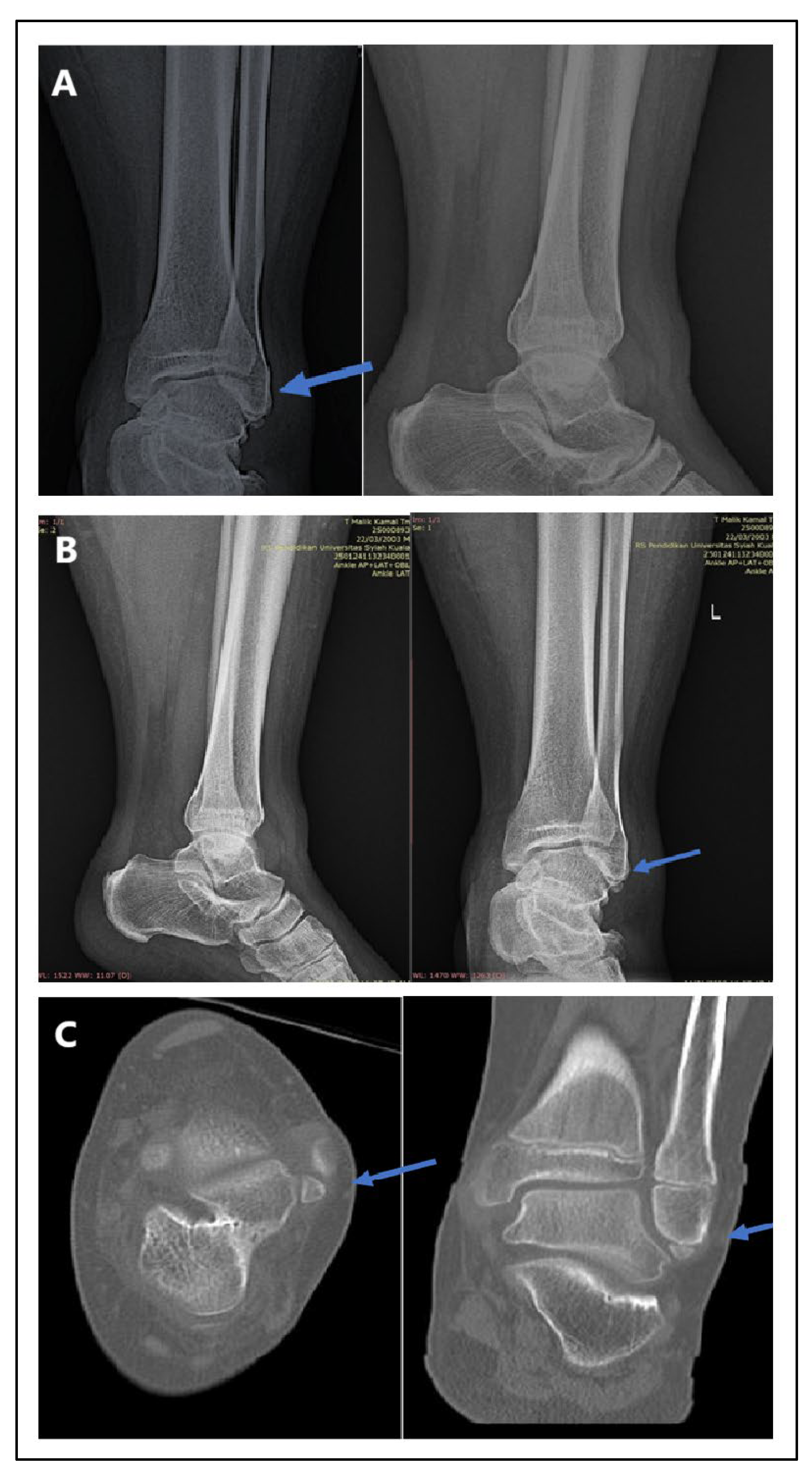

Figure 6 presents radiographic imaging comparisons in a male patient with post-trauma left ankle pain. A portable X-ray (Figure A: minimal-resource) showed a poorly defined distal fibula fracture due to limited resolution and contrast. A follow-up X-ray with standard-resource imaging (Figure B) clearly depicted the distal fibula fracture. A CT scan (Figure C: gold standard) confirmed the fracture on axial and coronal views, identifying a Salter-Harris type II fracture. The blue arrows indicate the fracture site. These findings reinforce that minimal-resource imaging has limitations in detecting fractures compared to standard-resource imaging and CT scans, potentially leading to delayed or inaccurate diagnoses.

4. Discussion

This study analyzes the differences in diagnostic accuracy between minimal-resource and standard-resource methods in plain radiograph interpretation for fracture detection. It evaluates the impact of reader experience on diagnostic precision. The findings indicate that standard-resource imaging has significantly higher accuracy, highlighting the crucial role of imaging quality in fracture detection. Radiologists demonstrated the highest accuracy compared to general practitioners and radiology residents. Statistical analysis using diagnostic tests, Chi-Square tests, and ROC curve analysis confirmed that standard-resource imaging outperforms minimal-resource imaging in sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy. These findings underscore the importance of improving access to high-quality imaging, enhancing medical training, and utilizing artificial intelligence (AI) to minimize diagnostic errors in resource-limited settings.

The results show that standard-resource imaging offers significantly higher accuracy in detecting femoral fractures than minimal-resource imaging (p < 0.05). This advantage is attributed to superior imaging quality, including higher resolution, optimal contrast, and lower noise levels, which enhance the visibility of bone structures and fracture sites. ROC analysis confirms that standard-resource imaging has an area under the curve (AUC) closer to the gold standard (CT scan), indicating superior diagnostic accuracy. Higher sensitivity ensures this method reliably detects true fractures, while greater specificity reduces the likelihood of false-positive diagnoses.

Previous studies support these findings. Meena et al. (2022) reported that digital radiography enhances the detection of small fractures often missed with conventional methods [

14]. Ji et al. (1994) introduced an adaptive imaging algorithm that dynamically enhances contrast and sharpness based on anatomical regions, significantly improving the detection of wrist and ankle fractures. Their findings showed that adaptive contrast enhancement reduced misdiagnosis rates by

25% compared to conventional digital imaging [

15]. Additionally, Brady et al. (2012) highlighted that standard-resource imaging, when interpreted by medical personnel with radiology training, reduces false-negative and false-positive rates, which are more prevalent in minimal-resource methods [

16]. Ireland et al. (2024) further confirmed that inadequate lighting and improper exposure in portable radiography can reduce diagnostic accuracy by up to 40% compared to standard digital radiography [

17].

Reader experience significantly influences the accuracy of fracture diagnosis. Radiologists demonstrated the highest accuracy compared to general practitioners and radiology residents across both minimal-resource and standard-resource methods. This is attributed to their specialized training and extensive experience in radiographic interpretation, enabling them to identify fractures with greater precision. General practitioners exhibited lower accuracy with minimal-resource imaging but significantly improved when using standard-resource imaging. Chugh et al. (2024) reported that diagnostic accuracy is highly dependent on reader experience, with radiologists achieving over 90% accuracy, whereas general practitioners achieved only 65% under minimal-resource conditions [

18]. Aggarwal et al. (2021) found that digital imaging enhances accuracy for general practitioners by up to 80% [

19], while Patel et al. (2019) reported that additional radiographic training can improve diagnostic accuracy by 20%, especially when supported by higher-quality imaging [

20].

The limitations of the minimal-resource method are a primary factor contributing to diagnostic errors in fracture detection. Low-resolution images, poor contrast, and high noise levels make fracture margins difficult to identify, particularly for minor or non-displaced fractures. These limitations significantly impact less-experienced medical personnel, such as general practitioners, who rely more on visual image quality for diagnosis. Li et al. (2020) reported that low-resolution radiography increases false-negative rates by 35% compared to advanced digital imaging [

21]. Patel et al. (2018) found that medical personnel with limited experience exhibit higher diagnostic error rates when using minimal-resource imaging, with an accuracy of around 60%, compared to 85% with standard-resource imaging [

22]. Sumner et al. (2024) also showed that false-positive rates are higher in portable radiography with improper exposure, leading to overdiagnosis and unnecessary medical interventions [

23].

The clinical impact of the limitations of minimal-resource imaging is significant. Diagnostic errors due to poor image quality can lead to delayed or incorrect patient management. Undetected fractures (false negatives) may result in complications such as malunion or nonunion, while false positives can lead to unnecessary immobilization or surgical interventions. Varady et al. (2020) reported that delayed fracture diagnosis increases patient treatment duration by 30% and raises the risk of more complex surgical interventions [

24]. Takapautolo et al. (2024) found that false-positive errors in portable radiography can lead to unnecessary medical procedures, imposing physical and financial burdens on patients [

25]. Langen et al. (1993) demonstrated that digital radiography improves the detection of subtle fractures by 35%, allowing for faster and more accurate treatment [

26].

To overcome the limitations of minimal-resource imaging, additional training for general practitioners and radiology residents is essential for improving diagnostic accuracy. Smith et al. (2020) reported that supplementary radiographic interpretation training increases diagnostic accuracy by 20% for general practitioners and radiology residents. Linsay et al. (2019) found that case-based training programs enhance sensitivity in general practitioners from 65% to 82%, particularly when supported by higher-quality imaging [

27]. Besides training, AI-based diagnostic support has significantly improved radiographic interpretation accuracy [

28]. Deep-learning AI algorithms can detect fractures with 92% sensitivity, approaching the accuracy level of expert radiologists [

14]. Zhen et al. (2021) found that AI integration in imaging systems reduces false-negative rates by 30%, which is highly beneficial for medical personnel with limited radiology training [

29].

As a key recommendation, increasing access to high-quality radiology facilities is essential, particularly in resource-limited areas. Pinto et al. (2018) reported that restricted access to high-quality imaging in primary healthcare settings increases false-negative rates by 35%, leading to delayed treatment and higher fracture complication risks [

11]. Guermazi et al. (2022) found that implementing digital imaging systems in regional hospitals improved fracture diagnosis sensitivity by 25% [

30]. Beyond expanding access to radiology facilities, optimizing imaging technology and developing AI-based diagnostic systems could offer solutions for resource-limited settings [

31]. Khalifa et al. (2024) reported that integrating AI into digital radiography enhances diagnostic efficiency and accelerates clinical decision-making [

32]. Thaker et al. (2024) further demonstrated that AI-enhanced digital radiography reduces diagnostic errors by up to 40%, particularly for non-radiology medical personnel [

33]. Thus, increased access to high-quality imaging facilities and AI-assisted radiographic interpretation could improve fracture diagnosis accuracy, particularly in resource-limited environments [

34].

5. Limitations

The limitations of this study include its cross-sectional design, which does not assess changes in radiographic interpretation skills over time, and the limited generalizability of the findings to resource-constrained facilities. Additionally, the study compares only two imaging methods without considering other factors, such as variations in fracture types and the specific experience levels of radiographic interpreters. The potential impact of artificial intelligence (AI) in improving diagnostic accuracy was also not directly evaluated. Further research with a longitudinal design and AI integration is needed to assess the long-term effects on fracture diagnosis accuracy.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the standard-resource method has significantly higher accuracy than the minimal-resource method in detecting fractures, with a statistically significant difference. Standard-resource imaging is more reliable for diagnosis due to its superior sensitivity and specificity, closely approaching the gold standard (CT scan). The limitations of minimal-resource imaging, such as low resolution and high noise levels, increase the risk of diagnostic errors, particularly for medical personnel with limited experience. Expanding access to high-quality radiology facilities and developing AI-based imaging systems are essential to enhancing diagnostic accuracy and efficiency in clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft: Z., I.; Writing—review & editing: Y., T.M., R., S., and G., A.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Fakultas Kedokteran dan Dr. Zainoel Abidin General Hospital, approval number 204/ETIK-RSUDZA/2024, approved on 16 August 2024.

Informed Consent Statement:

Written consent was waived due to the study’s retrospective nature, and all data were anonymized.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding Author. However, the data are not publicly accessible due to institutional policy.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Dr. Zainoel Abidin General Hospital (RSUDZA) Banda Aceh for providing research facilities and data support and to the radiology team, medical personnel, and medical records staff for their assistance in data collection and analysis. Appreciation is also extended to the RSUDZA Health Research Ethics Committee for granting ethical approval for this study. Finally, the authors sincerely thank all individuals who contributed to completing this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Global, regional, and national burden of bone fractures in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev, 2021. 2(9): p. e580-e592.

- Metsemakers, W.-J., et al., General treatment principles for fracture-related infection: recommendations from an international expert group. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery, 2020. 140: p. 1013-1027. [CrossRef]

- te Stroet, M., et al., The value of a CT scan compared to plain radiographs for the classification and treatment plan in tibial plateau fractures. Emergency radiology, 2011. 18: p. 279-83. [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, P., et al., Machine learning in radiology: applications beyond image interpretation. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 2018. 15(2): p. 350-359. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Halim, C.N., et al., Diagnostic accuracy of imaging modalities in detection of histopathological extranodal extension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncology, 2021. 114: p. 105169. [CrossRef]

- Bashshur, R.L., et al., The Empirical Foundations of Teleradiology and Related Applications: A Review of the Evidence. Telemed J E Health, 2016. 22(11): p. 868-898. [CrossRef]

- Krug, R., et al., High-resolution imaging techniques for the assessment of osteoporosis. Radiol Clin North Am, 2010. 48(3): p. 601-21. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, R.Y., et al., Artificial intelligence in fracture detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology, 2022. 304(1): p. 50-62. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, L., et al., An evaluation of a training tool and study day in chest image interpretation. 2022.

- Murphy, A., et al., Radiographic image interpretation by Australian radiographers: a systematic review. Journal of medical radiation sciences, 2019. 66(4): p. 269-283. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A., et al., Traumatic fractures in adults: missed diagnosis on plain radiographs in the Emergency Department. Acta Biomed, 2018. 89(1-s): p. 111-123. [CrossRef]

- Al-Worafi, Y.M., Quality of Diseases/Conditions Diagnosis Procedures in Developing Countries: Status and Future Recommendations, in Handbook of Medical and Health Sciences in Developing Countries: Education, Practice, and Research. 2023, Springer. p. 1-28.

- Feuerman, M. and A. Miller, Relationships between statistical measures of agreement: Sensitivity, specificity and kappa. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice, 2008. 14: p. 930-3. [CrossRef]

- Meena, T. and S. Roy, Bone fracture detection using deep supervised learning from radiological images: A paradigm shift. Diagnostics, 2022. 12(10): p. 2420. [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.L., M.K. Sundareshan, and H. Roehrig, Adaptive image contrast enhancement based on human visual properties. IEEE Trans Med Imaging, 1994. 13(4): p. 573-86. [CrossRef]

- Brady, A., et al., Discrepancy and error in radiology: concepts, causes and consequences. Ulster Med J, 2012. 81(1): p. 3-9.

- Ireland, T., et al., ACPSEM position paper: recommendations for a digital general X-ray quality assurance program. Physical and Engineering Sciences in Medicine, 2024. 47(3): p. 789-812. [CrossRef]

- Chugh, V., et al., Employing nano-enabled artificial intelligence (AI)-based smart technologies for prediction, screening, and detection of cancer. Nanoscale, 2024. 16(11): p. 5458-5486. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R., et al., Diagnostic accuracy of deep learning in medical imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ digital medicine, 2021. 4(1): p. 65. [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.N., et al., Human–machine partnership with artificial intelligence for chest radiograph diagnosis. NPJ digital medicine, 2019. 2(1): p. 111. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., et al., High-resolution chest x-ray bone suppression using unpaired CT structural priors. IEEE transactions on medical imaging, 2020. 39(10): p. 3053-3063. [CrossRef]

- van Dijken, B.R.J., et al., Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging techniques for treatment response evaluation in patients with high-grade glioma, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol, 2017. 27(10): p. 4129-4144.

- Sumner, C., et al., Medical malpractice and diagnostic radiology: challenges and opportunities. Academic radiology, 2024. 31(1): p. 233-241. [CrossRef]

- Varady, N.H., B.T. Ameen, and A.F. Chen, Is Delayed Time to Surgery Associated with Increased Short-term Complications in Patients with Pathologic Hip Fractures? Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2020. 478(3): p. 607-615.

- Takapautolo, J., M. Neep, and D. Starkey, Analysing false-positive errors when Australian radiographers use preliminary image evaluation. J Med Radiat Sci, 2024. 71(4): p. 540-546. [CrossRef]

- Langen, H.J., et al., Digital radiography versus conventional radiography for the detection of a skull fracture under varying exposure parameters. Invest Radiol, 1993. 28(3): p. 231-4. [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S., et al., Outcomes of gender-sensitivity educational interventions for healthcare providers: A systematic review. Health Education Journal, 2019. 78(8): p. 958-976. [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, M.M.F., et al., Advancements in AI-driven diagnostic radiology: Enhancing accuracy and efficiency. International journal of health sciences, 2024. 5(S2): p. 1402-1414. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q., et al., Artificial intelligence performance in detecting tumor metastasis from medical radiology imaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 2021. 31. [CrossRef]

- Guermazi, A., et al., Improving radiographic fracture recognition performance and efficiency using artificial intelligence. Radiology, 2022. 302(3): p. 627-636. [CrossRef]

- Dangi, R.R., A. Sharma, and V. Vageriya, Transforming Healthcare in Low-Resource Settings With Artificial Intelligence: Recent Developments and Outcomes. Public Health Nursing, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M. and M. Albadawy, AI in diagnostic imaging: Revolutionising accuracy and efficiency. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine Update, 2024: p. 100146. [CrossRef]

- Thaker, N.G., et al., The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Early Cancer Detection: Exploring Early Clinical Applications. AI in Precision Oncology, 2024. 1(2): p. 91-105. [CrossRef]

- Kutbi, M., Artificial intelligence-based applications for bone fracture detection using medical images: a systematic review. Diagnostics, 2024. 14(17): p. 1879. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).