1. Introduction

An organization consists of individuals working together, and its success depends on the collective efforts of both leaders and employees, as well as the overall productivity of the workforce (Santos et al., 2022). To thrive and grow, organizations must continuously adapt, evolve, and respond to internal and external changes. This requires the ability to innovate, transform information into knowledge, solve problems, and create value (Ribeiro, 2008). In this context, the modern industrial landscape increasingly recognizes the significance of human capital, prompting organizations to rethink their approaches to people management. Employees are no longer viewed solely as resources responsible for delivering products and services; rather, they are seen as fundamental to an organization’s capacity to provide high-quality services and maintain continuous development (Santos et al., 2022).

To remain competitive and sustainable in today’s dynamic economic environment, organizations must foster creativity and innovation while also considering how employees perceive leadership (Adams et al., 2018). People are central to organizational success (Wright et al., 2001), playing a crucial role in knowledge dissemination, business outcomes, and decision-making processes at both operational and strategic levels (Marguerita, 2022). Job satisfaction, which reflects individuals’ attitudes toward their work, is shaped by physiological, psychological, and environmental factors. Ensuring employee satisfaction and engagement is essential for maximizing performance and achieving business objectives (Alwali & Alwali, 2022). Consequently, organizations are adopting new leadership and management strategies to navigate complex decision-making scenarios, often characterized by information overload, competing priorities, and time constraints (Santos, 2022). Traditional hierarchical models, where decisions are made at the top and communicated downward, are increasingly inadequate in addressing the challenges of a rapidly changing business environment (Nassou & Bennani, 2023).

Managers should enable their employees to actively participate in decision-making processes within the organization, as this can lead to effective motivation, enhanced performance, and positive outcomes for all stakeholders (Gallo et al., 2019). Leadership is considered a fundamental force that drives an organization and plays a critical role in fostering an innovative culture, where employees are key contributors to producing innovative results. This culture is widely recognized as a vital factor for success (Adams et al., 2018). The effectiveness of leadership is determined not only by the leaders’ traits, skills, or attitudes and their understanding of tasks and objectives, but also by the overall characteristics of the organization itself (Losada-Vazquez, 2022).

Effective organizational management requires vision, strong communication skills, and the ability to motivate people. As a result, the characteristics of leaders have a significant impact on both the daily functioning and long-term development of an organization (Piwowar-Sulej & Iqbal, 2023). Ensuring that a company has leaders with the necessary qualifications, training, and strategic vision to drive organizational success is a challenge that all companies face (Gibson et al., 2006). Leaders play an essential role in the operation of an organization. To facilitate efficient functioning, they must perform critical tasks such as setting objectives, motivating their teams, engaging in decision-making, and providing feedback (Bass & Bass, 2009; Zhang et al., 2023). By creating a collaborative environment, leaders can inspire effective performance, allowing employees to engage with creativity and dedication (Alwali & Alwali, 2022). Leadership, therefore, has long been a topic of interest for scholars, practitioners, and professionals, especially in relation to organizational commitment and work (Santos et al., 2022).

The flow of information in an organization, particularly from the bottom up, is shaped by the perspectives of individuals from diverse fields and backgrounds, who increasingly play an important role in leadership decision-making (Wang et al., 2022; Adana et al., 2023). Bottom-up initiatives, where insights and information flow from lower levels to management, enhance organizational flexibility and adaptability (Yukl, 2009). However, successful information sharing relies on trust, transparency, and strong connections between decentralized managers and senior leadership (Vaz et al., 2021). Decentralized managers occupy central positions within organizational structures (Harding et al., 2014), and have increasingly become business partners, influencing decision-making processes with greater accuracy and insight, thus contributing to the organization’s success.

Decision-making is a key process within organizations. Managers at all levels are responsible for making decisions based on the information they receive, which is influenced by the organizational structure and the behavior of individuals and groups within it. In a global economy, making potentially biased decisions due to the sheer volume of information, simultaneous choices, pressure, or other constraints can have significant societal implications (Milkman et al., 2009).

In organizational structures, decentralization refers to the extent to which decision-making authority is delegated to lower levels. In situations of disruption or crisis, decentralization can impact the speed of action. However, the effectiveness of such actions is not automatic and depends on the quality of decisions, which is closely linked to the skills of lower-level employees (Adana et al., 2023). The concept of decentralized governance is complex both theoretically and practically (Anthony, 2023). During the 1980s, decentralized managers were often viewed negatively and considered “obsolete” due to the trend toward reducing hierarchical structures, a development that never fully materialized (Dopson & Stewart, 1990). Conversely, Schilit and Locke (1982) highlighted the value of the upward influence of decentralized managers. Centralized decision-making no longer aligns with the dynamic nature of today’s business environment, where companies must rapidly adapt to cope with disruption (Adana et al., 2023).

Decentralized managers are increasingly seen as individuals with both the power and capacity to act (Feldman & Pentland, 2003; Adana et al., 2023). One major challenge they face is the ability to manage multiple functions effectively at once (Bryant & Stensaker, 2011). According to Ström et al. (2023), a high level of trust facilitates decentralized management practices, as trust is a crucial element in decentralized decision-making.

Research on decision-making has expanded to focus on both top and decentralized managers, whose behavior significantly affects organizational success (Harding et al., 2014; Wooldridge et al., 2008). Typically, decentralized managers can have more influence on their subordinates compared to top managers, due to their proximity to the workforce (Sol & Anderson, 2016). These managers are also more likely to identify new opportunities within the organization, which they use to drive new initiatives (Raes et al., 2011). Top managers, on the other hand, may be too removed from day-to-day operations to recognize emerging opportunities or threats. Adana et al. (2023) suggest that future studies could focus on case studies and interviews to examine the internal and external factors affecting an organization’s decentralization level. Additionally, literature on leadership by decentralized managers remains limited, a gap this study seeks to address by exploring the leadership styles of these managers.

At the start of the 20th century, as scientific theories of management emerged, the study of leadership also gained prominence due to its critical role in organizational success (Bento & Ribeiro, 2013). Drawing from behaviorist and contingency theories, as well as various leadership styles, this research seeks to understand how both top and decentralized managers exercise leadership over their subordinates and the factors influencing their leadership practices. The following research questions were formulated:

RQ 1: What key characteristics do decentralized managers perceive in the leadership style of top managers?

RQ 2: According to Likert’s model, how do decentralized managers and top managers perceive their respective leadership styles?

RQ 3: Based on Burns’ model and the theoretical framework, how do decentralized managers and top managers practice leadership?

The next section presents a literature review, followed by a description of the methodology in

Section 3. In

Section 4, the results are analyzed and discussed, and

Section 5 concludes with final thoughts and contributions.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Leadership Concept

Leadership is defined as the process of influencing and guiding others towards the achievement of shared goals or a common vision (Teixeira, 2005; Northouse, 2021). The concept of leadership itself began to emerge in the early 19th century and has since become increasingly critical in today’s era of intense competition, shortened product life cycles, and globalization (Gibson et al., 2006).

Leadership may sometimes be perceived as a “gift,” where certain individuals naturally attract others in an almost inexplicable way (Bergamini, 1994). Gallo et al. (2019, p.91) define leadership as “a dynamic process of affecting people, where one person influences, for a certain period of time, under specific organizational conditions, other team members to participate, at their own discretion, in achieving the team’s goals.” Leadership can be either formal, when leaders are appointed to positions, or informal, when it arises organically. Leaders must demonstrate their capabilities in ever-changing environments that demand flexibility and the ability to adapt quickly (Ribeiro, 2008).

Innovation, which is fueled by creativity, is a critical organizational goal. However, innovation can only flourish if there is strong and effective leadership. Organizational leadership must empower employees by granting autonomy for innovative efforts while fostering an environment that values and rewards their contributions (Adams et al., 2018). Some organizational values that promote innovation include strategy, structure, support mechanisms, and behaviors that encourage communication (Adams et al., 2018). Leadership has garnered increasing attention due to its direct impact on outcomes (Santos, 2022).

An effective leader must balance individual, group, and organizational objectives. Some theorists suggest that effective leadership depends on inherent traits and behaviors, while others argue that it requires a specific leadership style for every situation (Gibson et al., 2006). The leader is the individual who guides and coordinates the group’s tasks (Fiedler, 1964; Chan, 2019).

Leadership is not merely an outcome but a continuous process of improvement. Leaders need to understand the context in which they operate and recognize development opportunities. They must be knowledgeable about their field and aware of the degree of development within it. Additionally, they must understand their team—both from a formal and informal perspective—acknowledging that every individual has distinct perceptions, expectations, needs, and learning styles. With this diversity, the leader must gather this information to exercise leadership effectively (Ribeiro, 2008).

The leadership profile is related to the professional and academic qualifications needed to hold a particular position within an organization. While specific leadership profiles can be identified, it is difficult to pinpoint a general leadership profile. Leadership styles can be categorized according to the behavior patterns leaders exhibit when managing and influencing employees (Ricardo, 2013). Various environmental, behavioral, and personal factors can influence these styles. Leaders are expected to demonstrate ethical leadership through their actions, decisions, and daily behaviors, creating an ethical organizational culture that fosters positive outcomes (Toor & Ofori, 2009). Leadership is a managerial function that focuses on building relationships, motivating employees, and enhancing performance to achieve organizational success (Alwali & Alwali, 2022).

In today’s increasingly technologically demanding global landscape, organizations must develop information systems tailored to their specific needs through their leadership. This allows organizations to manage valuable real-time information, impacting decision-making processes and shaping the future of the organization. Information must be current, accurate, accessible, appropriate, flexible, verifiable, and quantifiable (Reis, 2018). Under the new leadership paradigm, leaders exert influence not merely because of their position but because of their commitment to creating an organization that others genuinely want to be a part of.

2.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Leadership

Leaders often exhibit a specific leadership style as they motivate and inspire their followers. Leadership style, therefore, refers to how a leader chooses to interact with and guide their followers (Northouse, 2021).

To understand leadership, it is essential to grasp the dynamics that establish the roles of leaders and subordinates within a group (Dolores & Martins, 2016). Over time, several theoretical approaches have emerged to explain leadership, including trait theory, behavioral theory, and contingency theory.

Until the 1940s, researchers adhered to trait theory, which posited that leaders possessed inherent qualities that set them apart from others. These studies focused on identifying specific physical, mental, and personality characteristics that distinguished leaders, with the goal of developing methods to measure these traits and select potential leaders (Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1991; Chiavenato, 2004; Gibson et al., 2006; Bento & Ribeiro, 2013). However, due to the challenges in measuring these traits, researchers shifted focus between 1940 and 1960 to behavioral theory. This theory examined leadership by observing the behaviors of leaders in action, aiming to identify the behaviors associated with effective leadership (Fernandes, 2003; Gibson et al., 2006).

At the universities of Ohio and Michigan, studies were conducted in the field of behavioral theory. Both schools aimed to distinguish effective leaders from ineffective ones by analyzing specific behaviors (Reis, 2018). The research at Ohio University identified two key leadership behaviors: a people-oriented consideration dimension and a task-oriented initiating structure dimension (Reis, 2018; Stogdill, 1963). The consideration dimension reflects behaviors that prioritize the human aspects of leadership, addressing the social and emotional needs of subordinates while fostering a positive work environment. In contrast, the initiating structure dimension emphasizes tasks, such as planning, providing direction, and enforcing deadlines, ensuring that subordinates adhere to rules and performance standards, and clarifying procedures and goals (Teixeira, 2005). These two dimensions are considered independent, meaning a leader may prioritize one dimension and vary in their focus on the other (Fernandes, 2003). However, Bilhim (2001) found that leaders who excel in both dimensions tend to achieve higher levels of fulfillment and satisfaction from their subordinates than those who focus on one dimension.

Although the Ohio school’s theory challenged the traditional view that leadership should be exclusively focused on either people or tasks, it faced criticism for being limited to only two dimensions. This limitation makes it difficult to generate comprehensive insights and places heavy reliance on responses from questionnaires (Gibson et al., 2006).

In Michigan’s studies, the same behavioral dimensions were examined as in Ohio’s studies, aiming to identify the most effective leadership style (Likert, 1979). However, unlike Ohio, Michigan’s study suggested that the dimensions influence one another, meaning that leaders could prioritize one dimension at a time, but not both simultaneously. In other words, a leader who is more focused on people tends to be less focused on tasks, and vice versa (Fernandes, 2003). Regarding people orientation, leaders show greater interest in individuals, acknowledging their personal needs and fostering interpersonal relationships. In task orientation, leaders concentrate on productivity, viewing employees as means to achieve organizational goals, with an emphasis on technical aspects (Bilhim, 1996).

Based on the findings from Michigan’s study, it is evident that people-oriented leadership is generally more valued. This style is linked to more productive workgroups and higher employee satisfaction, whereas task-oriented leadership tends to result in lower productivity and greater employee dissatisfaction (Bilhim, 1996).

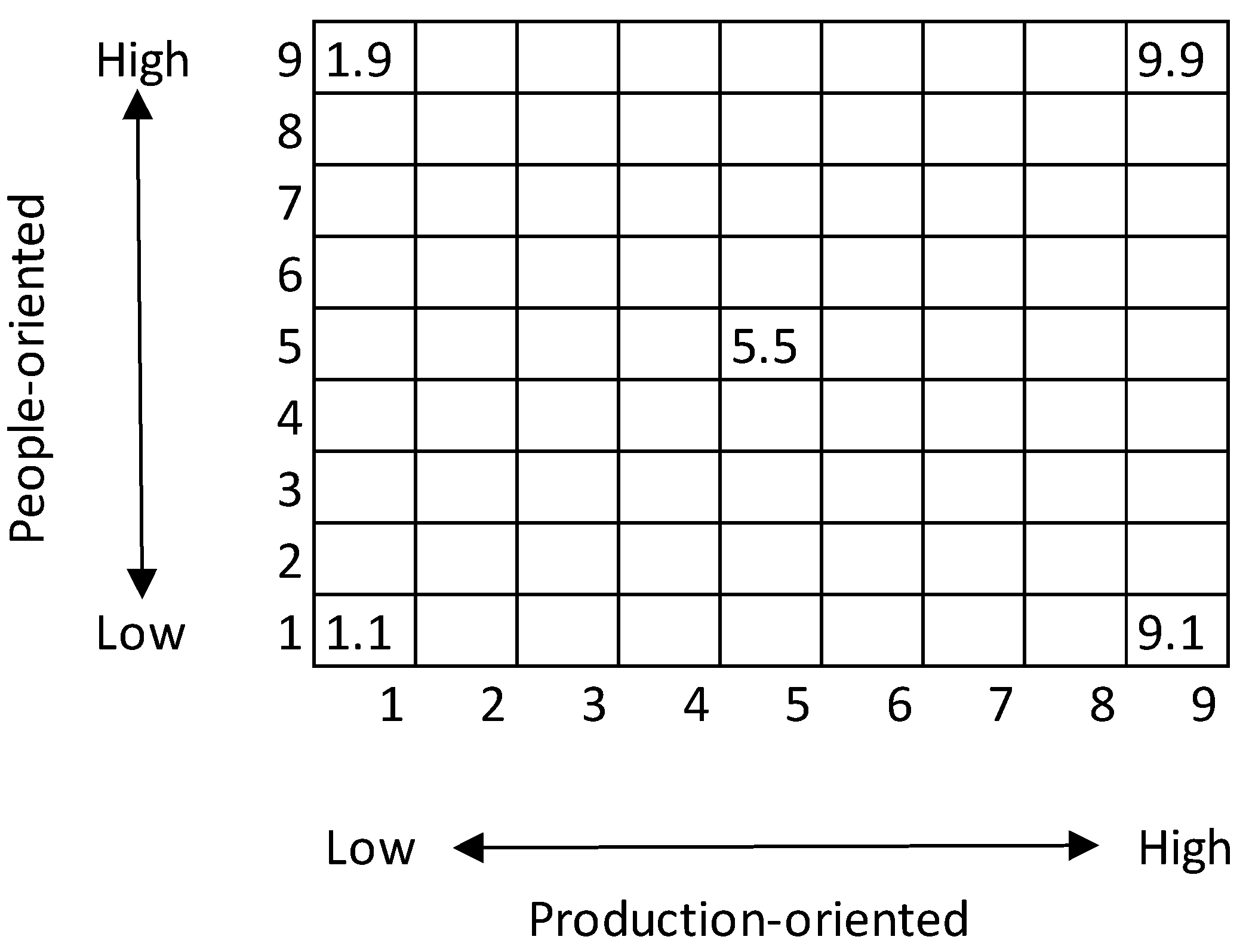

The studies from Ohio and Michigan contributed to the development of Blake and Mouton’s model (Blake & Mouton, 1987), which integrates the focus on production and people. This model illustrates that these two orientations are complementary aspects of leadership. The leadership grid consists of two axes: the horizontal axis represents production orientation, and the vertical axis represents people orientation. Each axis is divided into nine gradations, where 1 signifies the lowest level of guidance from the manager, and 9 represents the highest level. This framework results in five distinct behavioral leadership styles, as shown in

Figure 1.

In the impoverished style (1.1), the leader exhibits minimal orientation towards both people and tasks. This type of leader typically only does the bare minimum necessary to stay in the organization, adopting a passive attitude. The laissez-faire style (1.9) features a leader with minimal task orientation but maximum people orientation, focusing on fostering good relationships within the team and among subordinates. The autocratic style (9.1) reveals a leader who is highly production-oriented and minimally people-oriented. The manager emphasizes maximizing productivity through the use of power and authority. The team style (9.9) is considered the ideal, although it is difficult to achieve. In this style, the leader demonstrates a strong focus on both people and tasks. The leader concentrates on objectives, striving for high-quality and high-quantity results through participation, involvement, commitment, and conflict resolution, while maintaining trust, respect, and open communication (Blake & Mouton, 1987). The intermediate style (5.5) represents a leader who maintains a balanced orientation towards both people and production.

Due to dissatisfaction with the rigidity and limited application of this model, researchers turned their attention to contingency approaches. From the 1960s to the 1980s, studies were developed emphasizing the importance of contextual factors, suggesting that these are more significant than personal traits or behaviors in determining effective leadership (Ferreira et al., 2011). Fred Fiedler is recognized as the founder of contingency theory, which highlights the relationship between leadership effectiveness and situational circumstances (Fiedler, 1981). In 1958, Fiedler introduced contingency theory, proposing that leadership effectiveness depends on the control over the situation and the leader’s style (Rego, 1997; Shala et al., 2021). In essence, different situations require different leadership practices (Reis, 2018), and according to this theory, there is no ideal leadership style, only the most effective style for a given situation (Bilhim, 1996). Contingency theory has been rapidly embraced by industry as a management philosophy (Jablin, 1986), with applications in organizational settings (Shala et al., 2021). It calls for adjustments between uncertain environmental conditions (technological, social, sustainability, etc.) and organizational dynamics, such as decision-making processes (Adana et al., 2023).

The core assumption of contingency theory is that there is no single organizational structure that is universally applicable (Islam & Hu, 2012). Despite extensive research in this field, it is unlikely that a single contingency model can be developed with general settings that apply to all organizations. Therefore, contingency must be viewed in a more dynamic context (Otley, 2016).

Contingency theory posits that there is no single best way to manage an organization. A leader must identify which leadership style is best suited to achieving organizational objectives in each specific situation (Shala et al., 2021). The theory also suggests that there are various internal and external constraints affecting an organization’s ideal structure, such as its size, dependency, technology, culture, leadership style, and how it adapts to changes in strategy (Bilhim, 1996; Chenhall, 2006; Islam & Hu, 2012).

According to Fiedler, three main variables determine whether a situation is favorable or unfavorable to the leader (Bilhim, 1996; Ferreira et al., 2011; Rego, 1997; Shala et al., 2021; Teixeira, 2005; Vroom & Jago, 2007): the relationships between the leader and subordinates, which reflect the level of trust, belief, and respect subordinates have for the leader; the task structure, which refers to the characteristics of the work to be performed; and positional power, which is inherent to the leader’s position. Leaders who are task-oriented tend to be successful in both favorable and unfavorable situations. In contrast, relationship-oriented leaders succeed in intermediate situations, where the circumstances are neither highly favorable nor unfavorable (Bilhim, 1996; S. Teixeira, 2005). Gibson et al. (2006) suggest that, according to Fiedler, it is not possible for a leader to simultaneously focus on tasks and people. When a leader engages in behaviors that align with their personality, they feel more comfortable and confident in their role. As a result, the core of effective leadership lies in the combination of a leader’s style and personality with the specific situation in which they operate.

In Bilhim’s (2001) study, it was observed that as an organization grows, its formalization increases, and greater centralization of decision-making occurs. However, it is also important to adapt leadership styles to suit the organization’s needs. Leaders can be either task-motivated or relationship-motivated. Task-motivated leaders focus on achieving goals, while relationship-motivated leaders prioritize developing close interpersonal connections (Shala et al., 2021).

Contingency theory asserts that leaders are not effective in all situations (Shala et al., 2021), and there is no one-size-fits-all leadership model. Instead, leadership effectiveness is influenced by the specific circumstances in which leaders find themselves, requiring adjustments to the reality of each situation (Ricardo, 2013; Santos et al., 2022). A leader’s effectiveness is therefore determined by how well their leadership style is suited to the particular context (Santos et al., 2022). Boned and Bagur (2006) argue that, according to contingency theory, there is no universal control system applicable to all organizations; rather, the appropriateness of leadership practices depends on the specific context an organization faces. These authors reviewed several studies based on this theory and concluded that, despite the diversity of the research, the results were inconsistent, contradictory, and lacked empirical clarity. In essence, contingency theory emphasizes adaptation to various situations, suggesting that no one leadership style is inherently superior. Instead, leadership styles may be shaped by factors such as the leader-follower relationship, task structure, and the power held by the leader (Ricardo, 2013; Santos, 2022).

Contingency theory offers several key advantages based on empirical studies, such as the research by Peters et al. (1985), who concluded that this theory provides a valid and reliable approach. However, despite its support in many studies, contingency theory has also faced criticism. Shala et al. (2021) outline both the strengths and weaknesses of the theory. After examining Fiedler’s contingency model and similar studies, they assert that the theory is applicable in organizational environments (Shala et al., 2021). Researchers like Adana et al. (2023) and Alphun et al. (2023) have used contingency theory as a framework in their investigations into decentralization and decision-making.

2.3. Likert’s Model of Leadership

Leadership styles can be categorized in various ways (Gallo et al., 2019). Teixeira (2005) identifies four distinct leadership styles: autocratic, participative, democratic, and laissez-faire. Additionally, Ricardo (2013) suggests that there is no single ideal style, as the effectiveness of each style depends on the specific context. According to Ferreira et al. (2011), Rensis Likert conducted a study to examine the relationship between leadership effectiveness and the position of the manager, exploring four leadership styles across a continuum. This study led to the development of the Likert Leadership Continuum model, which is presented in

Table 1.

The autocratic style, the first leadership approach, is marked by a lack of trust in subordinates, centralized decision-making, limited interaction, and low motivation (Ferreira et al., 2011). In this style, leaders exercise full control over decisions and expect strict adherence from their followers, with little to no input from them (Northouse, 2021).

In contrast, the laissez-faire style is characterized by strong trust in subordinates, allowing them to participate in decision-making, with high interaction and autonomy (Ferreira et al., 2011). Laissez-faire leaders provide minimal guidance or supervision, giving followers significant freedom in decision-making and task completion. While this can foster creativity and innovation, it also carries the risk of insufficient support, guidance, and feedback from the leader (Northouse, 2021).

The intermediate styles, numbered 2 and 3, combine characteristics of both autocratic and participative approaches. Likert suggests that organizations that shift from styles 1 and 2 to styles 3 and 4 tend to see improved effectiveness, with increased productivity and higher levels of personal satisfaction (Ferreira et al., 2011).

Leadership styles can be adapted based on the team’s size, age, motivation, and the specific situation at hand (Bento & Ribeiro, 2013). According to Northouse (2021), the democratic or participative leadership style involves the leader engaging the team in decision-making, fostering open communication, and striving for consensus. Leaders who adopt this style value team members’ ideas and actively encourage their participation in setting goals and strategies, emphasizing collaboration and team involvement.

Zhang et al. (2023) point out that research often overlooks the varying interpretations and reactions of individuals when exposed to passive leadership, particularly from laissez-faire leaders. These leaders can have both positive and negative effects on subordinate performance, depending on the subordinates’ goal orientation. Furthermore, any general leadership style—whether autocratic, participative, democratic, or laissez-faire—can intersect with transformational and transactional leadership approaches.

Effective leadership focuses on what the leader does rather than their inherent traits, with the leader’s actions or behavior often being more significant than their profile (Ricardo, 2013). Choosing a leader with the appropriate leadership style is crucial for organizational success (Fey et al., 2001).

2.4. Burns’ Model of Leadership: Transformational and Transactional

The concept of transformational leadership was introduced by Burns (1978) to describe the ideal relationship between political leaders and their followers (Gui et al., 2022). Transactional leadership, on the other hand, focuses on the exchange process between leaders and followers (Northouse, 2021). According to Burns, leaders tend to adopt one of two contrasting behaviors: transformational leadership or transactional leadership (Rego, 1997). While transactional leadership is more focused on exchanges between the leader and followers, transformational leadership is a broader concept that emphasizes change and development. Bass (1985) expanded on transformational leadership, highlighting it as the leader’s ability to push employees to perform beyond normal expectations (Gui et al., 2022).

However, Bass et al. (2003) argue that transformational and transactional leadership should not be seen as opposite ends of a single continuum, as they are distinct concepts. The best leaders, according to these authors, are those who can blend both transformational and transactional qualities (Rego & Cunha, 2004). In some cases, transformational leaders may also display transactional behaviors (Dönmez & Toker, 2017).

Transformational leaders are known for creating a positive and supportive environment that encourages collaboration, creativity, and a strong sense of purpose. These leaders focus on fostering inclusivity within their teams. In contrast, transactional leaders define specific goals and performance standards, offering clear guidelines about what is expected from followers (Northouse, 2021).

Burns (1978) views transactional leadership as more than just an exchange relationship, while transformational leadership is focused on bringing about change. Yet, despite Bass et al. (2003) building on Burns’ framework, they assert that the two styles are separate, with the most effective leaders integrating both approaches (Rego & Cunha, 2004). Rego (1997) emphasizes that transformational leaders excel in initiating and driving change, while transactional leaders are better suited for stable, incremental changes in less dynamic environments. In transactional leadership, leaders reward subordinates for meeting objectives or impose punishments for failing to do so. This style relies on extrinsic motivations, with the leader addressing the needs of subordinates in exchange for task completion (Ricardo, 2013).

Bass et al. (2003) and Howell and Hall-Merenda (1999) propose two key processes for motivating followers in transactional leadership: contingent rewards, where leaders clearly communicate the expected performance and the corresponding rewards, and active management by exception, where leaders monitor subordinates closely for deviations and errors, imposing penalties when necessary.

Studies highlighted by Gibson et al. (2006) show that contingent rewards can lead to increased performance and satisfaction, as subordinates are motivated by the possibility of receiving rewards. However, there can be confusion if leaders misinterpret what subordinates want or when they want it, which may limit the effectiveness of transactional leadership. In contrast, transformational leaders motivate their followers to exceed initial expectations and achieve intrinsic rewards, fostering commitment to organizational goals and encouraging selfless efforts for the greater good of the organization (Bass, 1990; Rego & Cunha, 2004; Reis, 2018).

Transformational leaders often adjust goals, direction, and mission to address practical needs, making substantial changes in the organization’s mission, operations, and human resource management. Charisma is one of the key traits of transformational leaders, although they also need strong evaluation, communication, and interpersonal skills. They must be able to articulate their vision clearly and be sensitive to the challenges faced by their subordinates. Transformational leaders inspire their followers to prioritize organizational goals over personal ones, demonstrating respect and concern for their followers’ well-being and development (Schwepker & Good, 2010). These leaders aim to develop future leaders within their teams (Tucker & Russell, 2004). Given the effectiveness of this leadership style, organizations should recognize the presence of transformational leaders as a valuable asset (Rego & Cunha, 2004). A study by Singer (1985) found that managers preferred working with transformational leaders over transactional ones.

Transformational leaders motivate their followers to perform effectively by fostering an environment of collaboration and teamwork, enabling subordinates to work creatively and diligently. They shape the vision, inspire commitment to it, and cultivate an atmosphere conducive to innovation (Alwali & Alwali, 2022).

Transfor<mational leadership plays a crucial role in navigating the challenges organizations face, such as market uncertainty, rapid technological changes, and complex competition. It is essential for organizations because it can enhance performance at all levels (Bass, 1990). Judge and Piccolo (2004) found that transformational leadership has been more influential in recent decades than transactional leadership. Therefore, organizations across all sectors require transformational leaders (Tucker & Russell, 2004).

Bass et al. (2003) identified four key behaviors intrinsic to transformational leaders: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Despite years of research, no universally accepted model for leadership has emerged. Leaders are sought after for their ability to maintain and improve their teams within organizations. Studies continue to explore how these responsibilities can best be fulfilled. However, organizations led by transformational leaders tend to be more effective than those led by transactional leaders (Bass, 1990). Both transactional and transformational styles can align with general leadership approaches, such as autocratic, participative, democratic, and laissez-faire styles (Ricardo, 2013). Among these, transformational leadership aligns most closely with the modern leadership paradigm due to its unique characteristics.

Rego (1997) asserts that transformational leaders are better suited for initiating change, while transactional leaders excel in environments that require slow evolution and stability. In transactional leadership, leaders reward subordinates who meet objectives or punish them if they fail. This approach involves providing rewards in exchange for subordinates’ compliance. It also includes mechanisms for maintaining standards, minimizing errors, and rewarding or punishing based on performance (Dönmez & Toker, 2017). Extrinsic motivations often drive the achievement of goals in transactional leadership (Ricardo, 2013). Transformational leaders, on the other hand, resemble benevolent parents, intrinsically motivating their followers through challenges, empowerment, autonomy, guidance, and shared information. Transactional leaders motivate by offering external rewards, monitoring, and implementing control mechanisms (Dönmez & Toker, 2017).

Bass et al. (2003) and Howell and Hall-Merenda (1999) describe two motivational processes employed by leaders: contingent rewards, where leaders define expectations and specify rewards for meeting performance goals, and active management by exception, where leaders set performance standards, monitor subordinates for deviations, and punish non-compliance.

Research by Gibson et al. (2006) indicates that contingent rewards increase performance and satisfaction, as subordinates believe achieving goals will lead to desired rewards. However, confusion may arise if leaders misinterpret subordinates’ desires or the timing of rewards, leading to minimal transactional impact on leader-subordinate relationships.

In transformational leadership, leaders motivate their followers to exceed set goals and achieve intrinsic rewards. These leaders encourage subordinates to prioritize organizational goals over personal interests (Bass, 1990; Rego & Cunha, 2004; Noeverman, 2007; Adams et al., 2018). The motivations here are intrinsic, focusing on professional development (Ricardo, 2013). The relationship between transformational leaders and their followers is based on qualitative aspects and interpersonal connections (Noeverman, 2007). Transformational leadership is often associated with sustainability, making it particularly relevant when addressing long-term challenges (Losada-Vazquez, 2022).

Transformational leaders typically adjust goals, direction, and mission to meet practical needs, making significant changes to the organization’s mission, practices, and human resource management. Charisma is a defining trait of transformational leaders, though they also require skills in assessment, communication, and sensitivity to others. They must articulate their vision clearly and be mindful of subordinates’ technical difficulties. Transformational leaders can persuade subordinates to focus on organizational objectives rather than personal goals, demonstrating respect and concern for their followers’ feelings and development (Schwepker & Good, 2010). These leaders aim to cultivate leadership qualities in their subordinates (Tucker & Russell, 2004).

In transactional leadership, leaders focus on the quantitative evaluation of performance and deviations from set objectives. They reward or punish subordinates based on their performance (Noeverman, 2007). Transactional leadership is more task-oriented, depending on employee commitment (Adams et al., 2018). Some studies suggest that transformational leadership drives organizational learning capabilities, innovation, and social impact (Losada-Vazquez, 2022). In Sliwka et al. (2024), transformational leadership was found to be the most common style, although transactional leadership also exists.

Given the dynamic relationship between transformational leadership, job satisfaction, and job performance, job satisfaction may mediate the connection between transformational leadership and job performance (Alwali & Alwali, 2022). The effectiveness of transformational leadership makes the presence of transformational leaders an economic asset (Rego & Cunha, 2004). Singer (1985) found that managers prefer working with transformational leaders over transactional leaders.

Given the challenges organizations face, transformational leadership is increasingly crucial for improving organizational performance. It motivates employees to realize their full potential and contribute effectively to organizational goals (Nawaz et al., 2024). According to Judge and Piccolo (2004), transformational leadership has been more influential in recent decades compared to transactional leadership. Every organization needs transformational leaders (Tucker & Russell, 2004). Toor and Ofori (2009) found a positive correlation between ethical leadership and transformational leadership, and between transformational leadership and organizational culture, employee satisfaction, and leader effectiveness. However, ethical leadership showed no relationship with transactional leadership and a negative correlation with laissez-faire leadership.

Laissez-faire leadership, often viewed as the least effective, involves reduced leadership responsibilities, allowing subordinates to take on more decision-making authority (Bass & Bass, 2009). Although some recent studies have suggested that laissez-faire leadership can have a modest positive effect on outcomes, Zhang et al. (2023) explored its impact more comprehensively, showing differing perspectives on the style’s effectiveness.

Silva et al. (2023) found that transformational leadership promotes positive behavioral outcomes in managers, such as satisfaction, effectiveness, and extra effort, while laissez-faire leadership produces negative effects. Transactional leadership had a neutral impact on effectiveness. Overall, transformational leadership yields the best behavioral results. Transformational leaders inspire employees, build trust, encourage innovation, and drive transformation to improve productivity and performance (Nawaz et al., 2024).

Bass et al. (2003) define four key behaviors of transformational leaders: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Despite extensive study, no universally agreed-upon leadership model has emerged. According to Gallo et al. (2019), no single leadership style is universally ideal. However, organizations highly value leaders who meet their responsibilities to maintain and enhance their teams. Studies continue to explore how to best achieve these objectives. Organizations with transformational leaders are more effective than those led by transactional leaders (Bass, 1990). Of the two leadership styles, transformational leadership is more aligned with the modern leadership paradigm.

In the face of the 21st-century challenges, organizations must focus on stabilizing individuals, developing organizational skills, boosting productivity, and maintaining sustainable competitive advantages (Reis, 2018). Transformational leaders motivate and inspire employees to exceed expectations (Nawaz et al., 2024), and the leadership challenge lies in training future leaders who instill confidence, drive results, and shape the organizational environment. In today’s technologically demanding world, organizations must develop tailored information systems to support decision-making and influence their future trajectory. Information should be current, accurate, accessible, and flexible (Reis, 2018). In this new leadership paradigm, leaders influence not only because of their position but because they are committed to creating an organization others wish to belong to.

4. Analysis and Discussion of the Results

To achieve the stated objectives, we identified the leadership styles employed by both decentralized and top managers, and examined these in relation to the theoretical framework.

4.1. Leadership Perception Regarding the Top Manager

Understanding leadership requires considering multiple organizational levels, a point often overlooked in leadership studies (Hannah & Lester, 2009). To address Research Question 1 (RQ1) – What are the main characteristics that decentralized managers perceive in the leadership style of the top manager? – at the start of each interview, both the top and decentralized managers were asked to rate five key leadership traits on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 was very poor and 5 was excellent: 1) Presence, support, leadership, and assistance from the director; 2) Feedback to employees; 3) Recognition of others’ work; 4) Problem and error-solving; 5) Characteristics of the line manager. This was designed to assess whether the perceptions of the two groups of managers regarding the top manager’s leadership style aligned.

Decentralized managers viewed the top manager as a caring and approachable person who offers support, instills trust, respects others, and welcomes differing opinions. The top manager also recognized having these qualities. Furthermore, both groups agreed that the top manager regularly provides individual and collective feedback. Decentralized managers noted that the top manager praises and recognizes their contributions, sharing appreciation with the team, which was also confirmed by the top manager. Additionally, decentralized managers perceived the top manager as open-minded, willing to ask for help, listen, share ideas, take responsibility for mistakes, and seek consensus with the team, a view supported by the top manager himself. Lastly, they described the top manager as not being arrogant, stubborn, or authoritarian, but rather “good” in terms of motivation, security, confidence, decisiveness, work capacity, leadership, presence, concern, persistence, determination, and dedication. The top manager’s self-assessment was similar.

These findings suggest a strong alignment between the top and decentralized managers regarding the top manager’s key leadership traits. This is consistent with Raes et al. (2011), who argued that poor relationships between these groups could lead to divergence in perceptions, actions, and strategic direction. Our study also supports Adams et al. (2018), which emphasizes that ongoing support and feedback between organizational levels enables leaders to exert individualized influence, helping subordinates exceed their current performance levels. Additionally, including senior leaders in communication and collective leadership training enhances organizational learning and social impact (Losada-Vazquez, 2022).

In summary, the results indicate that decentralized managers perceive the top manager’s leadership as one characterized by open communication, mutual support, regular feedback, and a positive, collaborative attitude. This alignment fosters a strong connection between the two managerial levels, ensuring consistency in objectives and strategies.

4.2. Leadership Perception Regarding the Top Manager

To address Research Question 2 (RQ2) – How do decentralized managers and the top manager perceive their leadership styles, based on Likert’s model? – the interviewees were asked questions related to Likert’s continuous model of leadership. These questions were posed at the beginning of each interview to evaluate how the managers perceived their leadership style across the following characteristics: leader-subordinate relationship, decision-making, motivation system, and communication.

To explore the leader-subordinate relationship, the interviewees were asked about their rapport with their subordinates. All responses highlighted trust as a central element of their relationships. Trust facilitates more decentralized management practices and plays a crucial role in decentralized decision-making (Ström et al., 2023). Therefore, in terms of the leader-subordinate relationship, most decentralized managers identified with Style 3 of Likert’s model.

Next, we investigated the decision-making process. Most responses emphasized decision delegation and decentralization as key strategies. This suggests that, in terms of decision-making, most decentralized managers also identified with Style 3.

Regarding the motivation system, the interviewees were asked how motivation was managed within their teams. Rewards and accountability were consistently highlighted as key elements. As a result, in terms of motivation systems, most decentralized managers viewed themselves as adopting a laissez-faire style.

Communication within teams was also examined. Interviewees were asked to assess how they communicated with their subordinates. Most respondents emphasized open communication as essential for effective leadership, though boss-subordinate interaction was also noted.

In summary, the findings indicate that, based on their self-assessments, the decentralized managers emphasized the following aspects of their leadership style: trust between managers and subordinates, decision-making based on delegation, rewards and accountability, and open communication. These managers placed themselves between Style 3 and laissez-faire in Likert’s model. Decentralized organizations often achieve higher management performance because sharing responsibilities and empowering decision-makers can lead to more focused and effective management (Nassou & Bennani, 2023).

4.3. Transactional Leadership and Transformational Leadership

To address Research Question 3 (RQ3) – How do decentralized managers and the top manager practice leadership, based on Burns’ model and the theoretical framework? – it is crucial to understand the system of rewards and motivations in place. All interviewees, including the top manager, emphasized that they do not offer rewards in exchange for obedience. Instead, the reward is seen as a gesture of appreciation for commitment and focus on objectives, without any emphasis on obedience. The goal is not to ensure "obedience" but rather to enable subordinates to understand and autonomously execute the defined objectives while maintaining critical thinking. Furthermore, the interviewees argued that there is no need for rewards tied to obedience, as their relationship with subordinates is not transactional. Mutual respect is seen as eliminating the necessity for obedience-based rewards, and it is crucial for employees to feel free to be authentic while maintaining a professional balance. Both the top manager and the decentralized managers strongly reject the idea of obedience as a key component of leadership.

It is also important to assess whether the decentralized managers and the top manager impose punishments when subordinates act against their interests or guidelines (Ricardo, 2013). All interviewees affirmed that they do not engage in such actions. If a rule violation occurs, a formal disciplinary process is initiated. Decentralized managers do not directly punish subordinates but may start a disciplinary process when necessary. Although the term "punishment" is considered too harsh, it is emphasized that employees must understand internal rules and the potential consequences of non-compliance, as this is standard practice within the organization. Guidelines should be communicated to employees, and any necessary disciplinary actions must follow a formal process, potentially leading to dismissal in extreme cases. Therefore, neither the decentralized managers nor the top manager engage in transactional leadership.

Based on the responses, it is clear that decentralized managers do not reward or punish their subordinates for failing to meet objectives (Ricardo, 2013), and therefore do not practice transactional leadership. To assess whether decentralized managers display transformational leadership, they were asked if they can motivate and influence subordinates to pursue the organization’s common goals, and how they achieve this. The interviewees generally stated that they motivate and influence their subordinates through regular meetings, expressions of gratitude, and continuous feedback. Some managers emphasized the importance of showing employees how their work contributes to the organization’s success, personally acknowledging good performance, especially when objectives are met or exceeded. Others conduct weekly meetings to share tasks and reinforce the importance of the company’s goals. They recognize the significance of staying informed about the company’s priorities, enabling them to communicate these effectively to their teams.

The managers believe that employee motivation is reinforced through responsibility and the recognition of their contributions. Each employee is motivated to pursue goals, with a clear understanding of their role in achieving them. Therefore, both decentralized managers and the top manager clearly practice transformational leadership, motivating subordinates to achieve the organization’s objectives rather than relying on rewards or punishments for obedience.

This suggests that both the decentralized managers and the top manager engage in transformational leadership, as they motivate subordinates to meet established goals without relying on transactional methods. This is aligned with the view that transformational leadership is driven by motivation rather than reward or punishment for obedience. According to Judge and Piccolo (2004), transformational leadership has become one of the most influential leadership models in recent years, surpassing other theories. In our study, this influence is clear, as all decentralized managers are recognized as practicing transformational leadership. Transformational leaders are often seen as key drivers of innovation capacity. This leadership style is considered highly effective in promoting innovation, as it stimulates employees’ intellectual engagement, encourages openness, and fosters discussions and experimentation with new ideas to enhance process innovation (Gui et al., 2022). The results support Bass et al. (2003), who argued that transactional and transformational leadership are distinct concepts. Organization X thrives due to its transformational leadership. Bass (1990) further stated that organizations led by transactional leaders are less effective than those with transformational leaders, who inspire commitment and foster an environment conducive to innovation (Alwali & Alwali, 2022). Transformational leaders motivate employees to continuously seek new knowledge and improve the organization’s capacity for innovation (Gui et al., 2022). The study by Alwali and Alwali (2022) shows that job satisfaction mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and job performance.

Both transformational and transactional leadership can fulfill one of the fundamental principles of management control: integrating a system of rewards and sanctions (Jordan et al., 2015). The sanctions system may include reminders or, in extreme cases, formal disciplinary action, while the rewards system does not necessarily involve monetary incentives. Non-monetary rewards are widely implemented within Organization X.

4.4. Behaviour and Contingency Theories

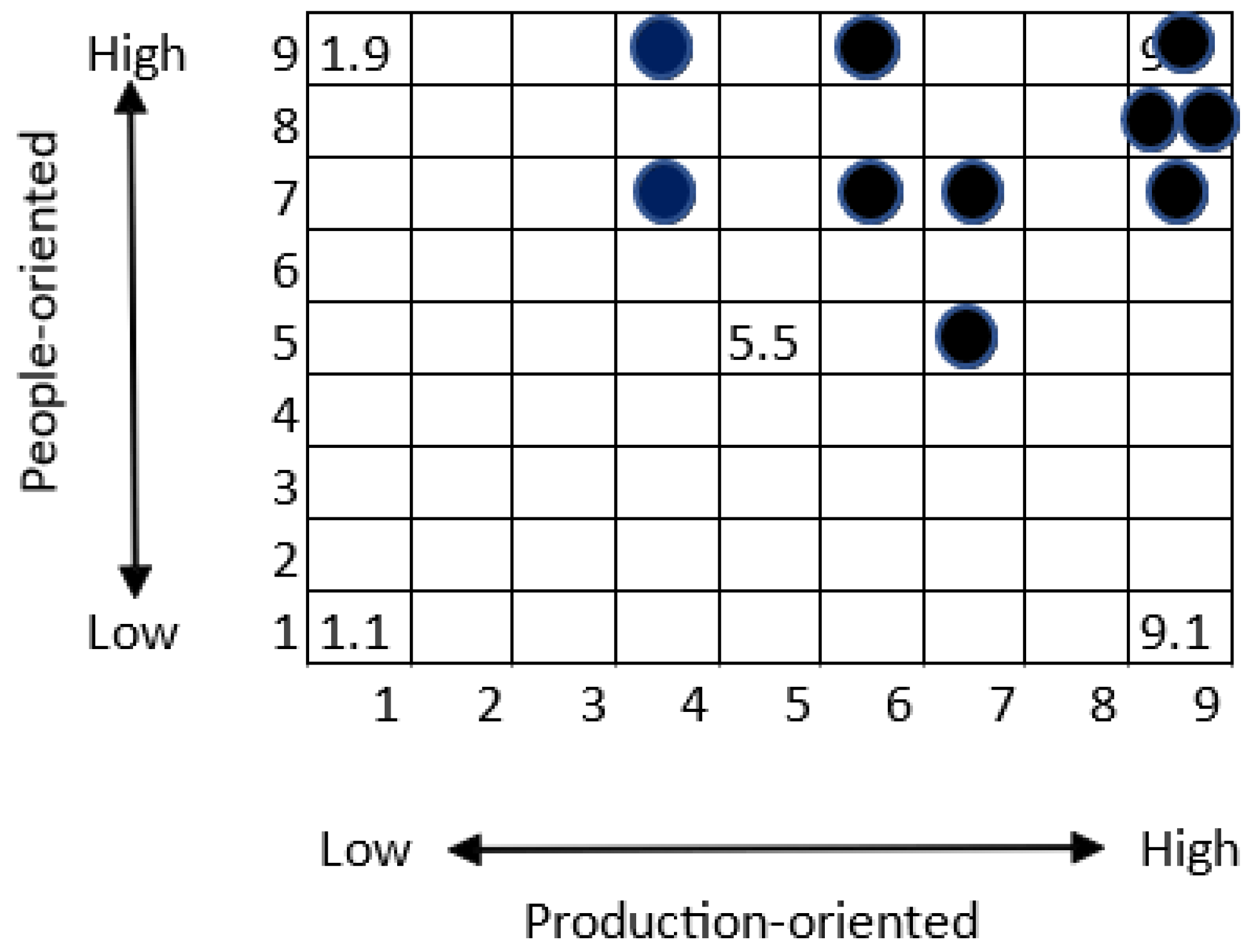

Both decentralized managers and the top manager were asked to assess their position on Blake and Mouton’s leadership grid. The outcomes are shown in

Figure 2.

It is evident that decentralized managers are predominantly positioned in the upper-right quadrant. Most of the decentralized managers, as well as the top manager, align between the intermediate style (5.5) and the team style (9.9) on Blake and Mouton’s grid. Some managers indicate that their focus on people versus tasks shifts depending on the situation. Effective leadership requires flexibility, as sometimes prioritizing people and other times focusing on tasks is necessary to balance organizational objectives with team well-being (Shala et al., 2021). Although many managers emphasize the importance of people-centric leadership, they also acknowledge the need to maintain a task-oriented approach. Some leaders take a blended approach, considering people and tasks equally important. This balance helps avoid disengagement and contributes to organizational goals by ensuring employees feel valued (Santos et al., 2022).

The Blake and Mouton model is practical in its application. It offers relevant insights with a favorable cost-benefit ratio, making it an appropriate complement to our case study. Despite its limitation of being a behavioral leadership theory, which overlooks situational factors that can affect leadership effectiveness, we addressed this gap by incorporating contingency theory. Leaders can be motivated by either fulfilling tasks or fostering interpersonal relationships (Shala et al., 2021).

Regarding motivation, decentralized managers differ in their focus, with some finding motivation in interpersonal relationships and others in task completion. Some report being motivated by both. For certain managers, personal relationships are vital, fostering trust and a cooperative work environment that enhances task completion. Others prioritize task efficiency and see relationships as secondary, though still significant for team success (McMahon & Perritt, 1973; Shala et al., 2021). These findings support Shala et al.’s (2021) view that task-oriented leaders aim for goal achievement, while relationship-oriented leaders focus on fostering close interpersonal connections. Santos et al. (2022) identify the task-oriented leadership style as dominant. However, tasks are often assigned based on communication with employees and feedback before making decisions, allowing employees to participate in organizational decision-making.

However, this perspective contradicts Gibson et al.’s (2006) assertion that a leader cannot be both task- and people-oriented simultaneously. Interviewees’ responses indicate a more nuanced reality, aligning with Shala et al.’s (2021) conclusion that some managers are motivated by both factors. The main motivational drivers for decentralized managers include personal relationships (trust and rapport), task motivation (completing tasks), or both.

Contingency theory also emphasizes the leader’s ability to adapt to situational variables, such as whether the environment is favorable or unfavorable (Bilhim, 1996; Ferreira et al., 2011; Rego, 1997; Shala et al., 2021; Teixeira, 2005; Vroom & Jago, 2007). Managers generally report a work environment characterized by respect, trust, and open communication, with room for sharing opinions and collaborative problem-solving, fostering a healthy and cooperative atmosphere (Shala et al., 2021).

When evaluating the relationship between decentralized managers, the top manager, and their subordinates, all interviewees describe a positive, respectful, and communicative environment conducive to sharing and trust (Shala et al., 2021). Regarding task structure, four interviewees consider it "Important," while six regard it as "Very Important." This indicates that decentralized managers maintain control and influence over the tasks, suggesting they are structured (Bilhim, 1996; Shala et al., 2021).

The final factor is power and authority. When asked about the authority to reward or punish subordinates, interviewees confirm they have the autonomy to reward subordinates through positive reinforcement, such as praise and support in decision-making. Punishment, however, is rare and typically avoided, being applied only after a formal process to ensure fairness (Gibson et al., 2006). In general, personal relationships are seen as a key motivator, while task orientation is essential for meeting organizational goals. The integration of these factors is crucial for effective leadership, with situational adaptability being central to decentralized management (Santos et al., 2022; Shala et al., 2021).

All decentralized managers affirm they have the autonomy to reward subordinates, but punishment does not apply. This suggests strong power and authority within the organization, as managers have the authority to hire, promote, or influence salary decisions. These findings align with the top manager’s view that they listen to subordinates regarding promotions or role changes. These results support the work of Tucker and Russell (2004), which highlights that transformational leaders use their power to inspire trust and lead by example.

In conclusion, the findings align with contingency theory, suggesting that leaders wield greater influence when they maintain a strong relationship with subordinates, structure roles clearly, and possess significant authority (Bilhim, 1996; Shala et al., 2021). This conclusion supports the results for transformational leadership, as both decentralized and top managers possess considerable influence over their subordinates. The use of contingency theory in this study reflects Jablin’s (1986) argument that it is the most applicable leadership theory across various organizational contexts. Contingency theory enables the integration of different theoretical approaches to address diverse leadership scenarios (Reis, 2018). By expanding on Hannah and Lester’s (2009) observation that leadership should be considered beyond a single level, we have addressed this gap by focusing on the influence of decentralized managers, as emphasized by Bukh and Svanholt (2020). Decentralized managers are increasingly recognized as powerful agents capable of independent action (Feldman & Pentland, 2003). According to contingency theory, there is no ideal leadership style. Leaders must determine the most effective approach based on the situation (Santos et al., 2022).

5. Concluding Remarks and Contributions

Managers have the ability to guide their subordinates and influence them to reach organizational goals. This study aims to explore how top and decentralized managers exercise their leadership, considering behavioral and contingency theories, along with different leadership styles. The research focuses on understanding the characteristics that influence their leadership. A detailed single case study was conducted in a large industrial organization, which included semi-structured interviews with top and decentralized managers, documentary analysis, and direct observation.

The findings suggest that there is alignment between the top manager’s leadership and the perceptions of decentralized managers. These managers perceive the top manager’s leadership as one characterized by open communication, information sharing, mutual support, regular feedback, and other positive traits. As a result, decentralized managers are closely connected to the top manager, with aligned objectives and strategies. Regarding the second research question, managers assessed themselves as falling between a style three and laissez-faire leadership approach.

The study indicates that both top and decentralized managers exhibit transformational leadership, with strong emphasis on both production and people. Decentralized managers play a significant role by alerting their hierarchical superiors to organizational issues through their meetings. Identifying problems becomes easier because the entire organization is aware of the objectives. When any issue deviates from those objectives, decentralized managers can quickly spot these discrepancies and inform the top manager. These insights align with the behavioral and contingency theories. In this study, both decentralized and top managers demonstrate a high focus on both production and people. Motivational factors for them may include personal relationships, task motivation, or a combination of both. However, as suggested by contingency theory, leaders may not always be effective in every situation.

In summary, our research suggests that decentralized managers can influence decision-making if their leadership styles align with transformational leadership, balancing both production and people. As Tjahjono and Rahayu (2024) emphasize, transformational leadership is both a contemporary and future-oriented style. It will remain highly relevant, attracting further research for sustaining organizational success, especially in environments characterized by rapid external changes. Leaders must adapt to these changing circumstances, such as managing human resources amidst globalization and competitive markets, which require swift decision-making to meet organizational visions and missions.

Our study also suggests that the decentralized managers of Organization X enjoy considerable autonomy in handling most situations, seeking the top manager’s guidance only for critical issues. The topic of leadership will remain a subject of interest due to its perceived importance for organizational success across various sectors. As Nassou and Bennani (2023) point out, understanding organizational structures and their influence on management performance continues to be a pertinent area for research.

This research contributes to advancing theoretical and practical knowledge of leadership, particularly decentralized leadership, and its role in organizational decision-making based on diverse theoretical frameworks. The findings could provide valuable insights for managers seeking to enhance organizational efficiency, especially in large companies with complex structures. Studies examining structures that impact society are crucial for understanding the influence of decentralized managers on organizational performance and employee productivity, particularly in terms of fostering innovation and creativity. For organizations, assessing whether decentralized managers’ leadership plays a key role in their success can be critical.

This study has certain limitations. It is based on a single case study in a specific context— a large industrial organization. Thus, the findings should be generalized only within a theoretical framework. Future research could extend this case study to other large organizations, both in Portugal and internationally, for comparative analysis. Additionally, the study did not explore social, cultural, environmental, political, or gender-related factors, which may affect the results. Further research could assess how leadership operates at lower levels within organizations.

Moreover, this research solely focused on leadership practices by decentralized managers and the top manager. Future studies may expand the scope by incorporating other factors influencing leadership, such as sustainable development goals, inclusion, innovation, artificial intelligence, or emotional intelligence.