Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Patients and Samples

2.2. Histopathologic Evaluation

2.3. Tissue Microarray Construction

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

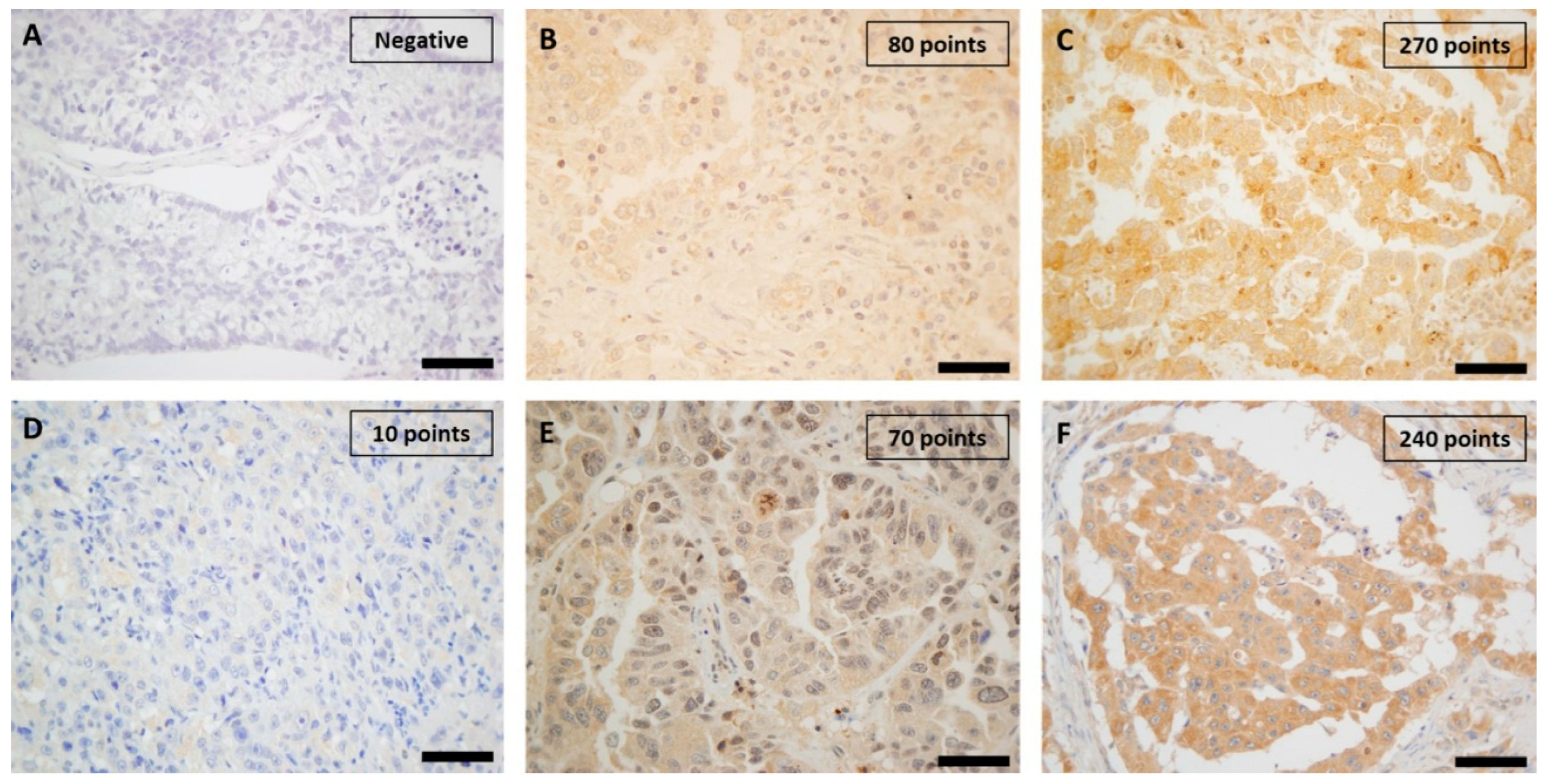

2.5. Immunohistochemistry Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinicopathological Features of Cases

3.2. Immunohistochemical Study of Proteins

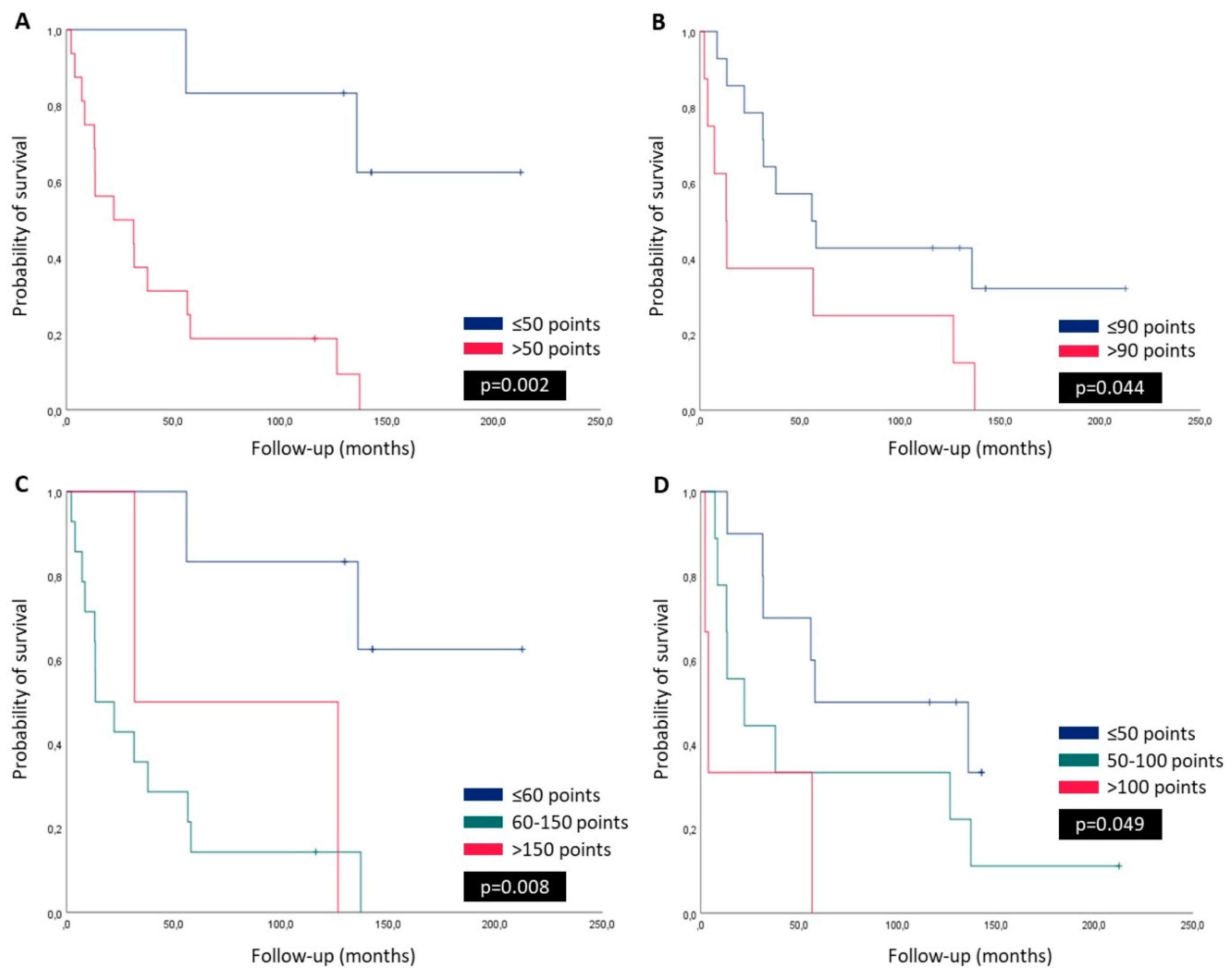

3.3. Survival Curves, Univariate and Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Authors' contributions

Ethical Approval and Consent to participate

Human Ethics

Consent for publication

Availability of supporting data

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal, A., et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021; 71 (3):209-249. [CrossRef]

- Polanco D, Pinilla L, Gracia-Lavedan E, Mas A, Bertran S, Fierro, G., et al. Prognostic value of symptoms at lung cancer diagnosis: a three-year observational study. J Thorac Dis 2021; 13 (3):1485-1494. [CrossRef]

- Luo G, Zhang Y, Rumgay H, Morgan E, Langselius O, Vignat, J., et al. Estimated worldwide variation and trends in incidence of lung cancer by histological subtype in 2022 and over time: a population-based study. Lancet Respir Med 2025. [CrossRef]

- Myers DJ, Wallen JM. Lung Adenocarcinoma. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL)2025.

- Ha SY, Choi SJ, Cho JH, Choi HJ, Lee, J., Jung, K., et al. Lung cancer in never-smoker Asian females is driven by oncogenic mutations, most often involving EGFR. Oncotarget 2015; 6 (7):5465-5474. [CrossRef]

- Sumiyoshi K, Yatsushige H, Shigeta K, Aizawa Y, Fujino A, Ishijima, N., et al. Survival prognostic factors in nonsmall cell lung cancer patients with simultaneous brain metastases and poor performance status at initial presentation. Heliyon 2024; 10 (18):e38128. [CrossRef]

- Waqar SN, Samson PP, Robinson CG, Bradley J, Devarakonda S, Du L, et al. Non-small-cell Lung Cancer With Brain Metastasis at Presentation. Clin Lung Cancer 2018; 19 (4):e373-e379. [CrossRef]

- Yen CT, Wu WJ, Chen YT, Chang WC, Yang SH, Shen SY, et al. Surgical resection of brain metastases prolongs overall survival in non-small-cell lung cancer. Am J Cancer Res 2021; 11 (12):6160-6172.

- Li, Y., Yan, B., He, S. Advances and challenges in the treatment of lung cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 2023; 169:115891.

- Sperduto PW, Mesko S, Li J, Cagney D, Aizer, A., Lin NU, et al. Survival in Patients With Brain Metastases: Summary Report on the Updated Diagnosis-Specific Graded Prognostic Assessment and Definition of the Eligibility Quotient. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38 (32):3773-3784. [CrossRef]

- Myall NJ, Yu H, Soltys SG, Wakelee HA, Pollom, E. Management of brain metastases in lung cancer: evolving roles for radiation and systemic treatment in the era of targeted and immune therapies. Neurooncol Adv 2021; 3 (Suppl 5):v52-v62. [CrossRef]

- Martini M, De Santis MC, Braccini L, Gulluni F, Hirsch, E. PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and cancer: an updated review. Ann Med 2014; 46 (6):372-383. [CrossRef]

- Yu JS, Cui, W. Proliferation, survival and metabolism: the role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling in pluripotency and cell fate determination. Development 2016; 143 (17):3050-3060. [CrossRef]

- Sanaei MJ, Razi S, Pourbagheri-Sigaroodi A, Bashash, D. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in lung cancer; oncogenic alterations, therapeutic opportunities, challenges, and a glance at the application of nanoparticles. Transl Oncol 2022; 18:101364. [CrossRef]

- Glaviano A, Foo ASC, Lam HY, Yap KCH, Jacot, W., Jones RH, et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol Cancer 2023; 22 (1):138. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L., Wei, J., Liu, P. Attacking the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway for targeted therapeutic treatment in human cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 2022; 85:69-94. [CrossRef]

- Chourasia AH, Boland ML, Macleod KF. Mitophagy and cancer. Cancer & metabolism 2015; 3:4.

- Drake LE, Springer MZ, Poole LP, Kim CJ, Macleod KF. Expanding perspectives on the significance of mitophagy in cancer. Seminars in cancer biology 2017; 47:110-124. [CrossRef]

- Gladkova C, Maslen SL, Skehel JM, Komander, D. Mechanism of parkin activation by PINK1. Nature 2018; 559 (7714):410-414. [CrossRef]

- Gan ZY, Callegari S, Cobbold SA, Cotton TR, Mlodzianoski MJ, Schubert AF, et al. Activation mechanism of PINK1. Nature 2022; 602 (7896):328-335.

- Bernardini JP, Lazarou, M., Dewson, G. Parkin and mitophagy in cancer. Oncogene 2017; 36 (10):1315-1327.

- Celis-Pinto JC, Fernández-Velasco AA, Corte-Torres MD, Santos-Juanes J, Blanco-Agudín N, Piña Batista KM, et al. PINK1 Immunoexpression Predicts Survival in Patients Undergoing Hepatic Resection for Colorectal Liver Metastases. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24 (7). [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi DP, Praharaj PP, Bhol CS, Mahapatra KK, Patra, S., Behera BP, et al. The emerging, multifaceted role of mitophagy in cancer and cancer therapeutics. Semin Cancer Biol 2020; 66:45-58. [CrossRef]

- Blazquez R, Wlochowitz D, Wolff A, Seitz S, Wachter A, Perera-Bel J, et al. PI3K: A master regulator of brain metastasis-promoting macrophages/microglia. Glia 2018; 66 (11):2438-2455. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Xiang A, Lin X, Guo, J., Liu, J., Hu, S., et al. Mitophagy: insights into its signaling molecules, biological functions, and therapeutic potential in breast cancer. Cell Death Discov 2024; 10 (1):457. [CrossRef]

- Zheng F, Zhong J, Chen K, Shi Y, Wang F, Wang S, et al. PINK1-PTEN axis promotes metastasis and chemoresistance in ovarian cancer via non-canonical pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2023; 42 (1):295. [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri S, Golbourn B, Huang X, Remke M, Younger S, Cairns RA, et al. PINK1 Is a Negative Regulator of Growth and the Warburg Effect in Glioblastoma. Cancer Res 2016; 76 (16):4708-4719. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Xu X, Huang H, Li L, Chen, J., Ding Y, et al. Pink1 promotes cell proliferation and affects glycolysis in breast cancer. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2022; 247 (12):985-995. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Wu W, Jiang S, Yu S, Yan, Y., Wang, K., et al. Pan-Cancer Analysis of the Mitophagy-Related Protein PINK1 as a Biomarker for the Immunological and Prognostic Role. Front Oncol 2020; 10:569887. [CrossRef]

- Heavey S, O'Byrne KJ, Gately, K. Strategies for co-targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in NSCLC. Cancer Treat Rev 2014; 40 (3):445-456. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 2022; 12 (1):31-46. [CrossRef]

- Tambo Y, Sone T, Nishi K, Shibata K, Kita T, Araya T, et al. Five-year efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab as first-line treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer with PD-L1 tumor proportion score ≥50 %: A multicenter observational study. Lung Cancer 2025; 201:108422. [CrossRef]

- Rudin CM, Awad MM, Navarro A, Gottfried M, Peters, S., Csőszi, T., et al. Pembrolizumab or Placebo Plus Etoposide and Platinum as First-Line Therapy for Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III KEYNOTE-604 Study. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38 (21):2369-2379. [CrossRef]

- Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 372 (21):2018-2028.

- Board WHOCoTE. Thoracic Tumours. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2021.

- Camacho-Urkaray E, Santos-Juanes J, Gutierrez-Corres FB, Garcia B, Quiros LM, Guerra-Merino, I., et al. Establishing cut-off points with clinical relevance for bcl-2, cyclin D1, p16, p21, p27, p53, Sox11 and WT1 expression in glioblastoma - a short report. Cellular oncology (Dordrecht) 2018; 41 (2):213-221. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Vega I, Santos-Juanes J, Camacho-Urkaray E, Lorente-Gea L, Garcia B, Gutierrez-Corres FB, et al. Miki (Mitotic Kinetics Regulator) Immunoexpression in Normal Liver, Cirrhotic Areas and Hepatocellular Carcinomas: a Preliminary Study with Clinical Relevance. Pathology oncology research : POR 2020; 26 (1):167-173. [CrossRef]

- Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Eberhardt WE, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11 (1):39-51. [CrossRef]

- He S, Li H, Cao M, Sun D, Yang, F., Yan, X., et al. Survival of 7,311 lung cancer patients by pathological stage and histological classification: a multicenter hospital-based study in China. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2022; 11 (8):1591-1605. [CrossRef]

- Kim MH, Kim SH, Lee MK, Eom JS. Recent Advances in Adjuvant Therapy for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2024; 87 (1):31-39. [CrossRef]

- Martin B, Paesmans M, Mascaux C, Berghmans T, Lothaire, P., Meert AP, et al. Ki-67 expression and patients survival in lung cancer: systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2004; 91 (12):2018-2025. [CrossRef]

- Moghbeli, M. PI3K/AKT pathway as a pivotal regulator of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung tumor cells. Cancer Cell Int 2024; 24 (1):165. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Wen X, Ren Y, Fan Z, Zhang, J., He, G., et al. Targeting PI3K family with small-molecule inhibitors in cancer therapy: current clinical status and future directions. Mol Cancer 2024; 23 (1):164. [CrossRef]

- Brastianos PK, Carter SL, Santagata S, Cahill DP, Taylor-Weiner, A., Jones RT, et al. Genomic Characterization of Brain Metastases Reveals Branched Evolution and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Cancer Discov 2015; 5 (11):1164-1177. [CrossRef]

- Fares J, Ulasov I, Timashev, P., Lesniak MS. Emerging principles of brain immunology and immune checkpoint blockade in brain metastases. Brain 2021; 144 (4):1046-1066. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Gu J, Chen J, Ni J, Hung, J., Wang, Z., et al. High expression of PINK1 promotes proliferation and chemoresistance of NSCLC. Oncol Rep 2017; 37 (4):2137-2146. [CrossRef]

- Fu D, Hu Z, Xu X, Dai X, Liu, Z. Key signal transduction pathways and crosstalk in cancer: Biological and therapeutic opportunities. Transl Oncol 2022; 26:101510. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Luan S, Fan X, Wang J, Huang J, Gao X, et al. The emerging multifaceted role of PINK1 in cancer biology. Cancer Sci 2022; 113 (12):4037-4047. [CrossRef]

- Zeng S, Gan HX, Xu JX, Liu JY. Metformin improves survival in lung cancer patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. Med Clin (Barc) 2019; 152 (8):291-297.

- Zhang B, Leung PC, Cho WC, Wong CK, Wang, D. Targeting PI3K signaling in Lung Cancer: advances, challenges and therapeutic opportunities. J Transl Med 2025; 23 (1):184. [CrossRef]

| Total | Stage IV | Stage I-III | P valor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 22 | 15 (68.2%) | 7 (31.8%) | - |

| Age (years) | 58.7 ± 8.7 | 60.7 ± 5.4 | 54.4 ± 12.7 | 0.113 |

|

Gender -male -female |

11 (50%) 11 (50%) |

8 (53.3%) 7 (46.7%) |

3(42.9%) 4 (57.1%) |

0.975 |

|

Status -alive -dead |

5 (22.7%) 17 (77.3%) |

2 (13.3%) 13 (86.7%) |

3 (42.9%) 4 (57.1%) |

0.321 |

|

Primary tumor location -Superior lobes -Other sites |

12 (54.5%) 10 (45.5%) |

9 (60%) 6 (40%) |

3 (42.9%) 4 (57.1%) |

0.361 |

|

Brain metastases location -Fronto-temporal lobes -Other sites |

17 (77.3%) 5 (22.7%) |

11 (73.3%) 4 (26.7%) |

6 (85.7%) 1 (14.3%) |

0.348 |

| Tumor size in primary tumor (cm) | 3.5 ± 1.4 | 3.6 ± 1.4 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 0.449 |

|

Survival (months) -OS |

68.1 ± 62.4 |

50.0 ± 52.5 |

106.9 ± 68.0 |

0.031 |

|

Adjuvant therapy -No -RT and/or CT -RT and CT |

3 (13.6%) 14 (63.7%) 5 (22.7%) |

0 12 (80%) 3 (20%) |

3 (42.8%) 2 (28.6%) 2 (28.6%) |

0.014 |

|

Grade in primary tumor -Well -Moderate -Poor |

7(31.8%) 8(36.4%) 7 (31.8%) |

4 (26.7%) 6 (40%) 5 (33.3%) |

3 (42.8%) 2 (28.6%) 2 (28.6%) |

0.741 |

|

Grade in brain metastasis -Well -Moderate -Poor |

3 (13.6%) 1 (4.6%) 18 (81.8%) |

2 (13.3%) 0 13 (86.7%) |

1 (14.3%) 1 (14.3%) 5 (71.4%) |

0.447 |

|

Necrosis in primary tumor -No -<25% -25%/50% -50%/75% ->75% |

4 (18.2%) 7 (31.8%) 7 (31.8%) 3 (13.6%) 1 (4.6%) |

6 (40%) 3(20%) 4 (26.6%) 1 (6.7%) 1 (6.7%) |

3 (42.8%) 2 (28.6%) 1 (14.3%) 1 (14.3%) 0 |

0.294 |

|

Necrosis in brain metastasis -No -<25% -25%/50% -50%/75% ->75% |

11 (50%) 5 (22.7%) 4 (18.2%) 0 2(9.1%) |

6 (40%) 3 (20%) 4 (26.6%) 0 2 (13.4%) |

5 (71.4%) 2 (28.6%) 0 0 0 |

0.420 |

|

Mitotic activity (per 10 HPF) -Primary tumor -Brain metastases |

18.0 ± 18.4 20.7 ± 16.5 |

22.8 ± 19.8 23.0 ± 18.6 |

7.7 ± 9.5 15.7 ± 10.2 |

0.343 0.026 0.285 |

|

PI3K (H-Score): -Primary tumor -Brain metastases |

96.8 ± 57.9 43.5 ± 62.3 |

113.3 ± 56.3 54.3 ± 70.2 |

61.4 ± 47.1 18.3 ± 28.6 |

0.003 0.043 0.319 |

|

PINK1 (H-Score): -Primary tumor -Brain metastases |

76.8 ± 40.0 77.5 ± 44.8 |

79.3 ± 39.9 75.7 ± 45.4 |

71.4 ± 43.0 81.7 ± 47.5 |

0.793 0.677 0.412 |

|

PDL1 (positive >1% tumor): -Primary tumor -Brain metastases |

9 (40.9%) 8 (36.4) |

7(46.7%) 8(53.3) |

2 (28.6%) 0 |

0.985 0.307 0.035 |

| Age | Tumor size | OS | Mitosis primary tumor | Mitosis brain metastases | PI3K primary tumor | PI3K brain metastases | PIKN1 primary tumor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size | r=-0.117 p=0.665 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| OS | r=-0.590 p=0.016 | r=-0.109 p=0.687 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mitosis primary tumor | r=-0.351 p=0.183 | r=0.673 p=0.004 | r=-0.032 p=0.908 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mitosis brain metastases | r=-0.486 p=0.056 | r=0.173 p=0.521 | r=0.193 p=0.474 | r=0.594 p=0.015 | - | - | - | - |

| PI3Kprimary tumor | r=0.402 p=0.122 | r=0.041 p=0.880 | r=-0.468 p=0.068 | r=0.179 p=0.508 | r=-0.009 p=0.975 | - | - | - |

| PI3Kbrain metastases | r=0.013 p=0.963 | r=-0.180 p=0.505 | r=-0.289 p=0.277 | r=0.107 p=0.692 | r=0.246 p=0.358 | r=0.556 p=0.025 | - | - |

| PINK1 primary tumor | r=0.180 p=0.505 | r=0.223 p=0.406 | r=-0.385 p=0.140 | r=0.410 p=0.115 | r=0.145 p=0.593 | r=0.372 p=0.156 | r=0.023 p=0.934 | - |

| PINK1brain metastases | r=0.149 p=0.582 | r=0.135 p=0.617 | r=-0.185 p=0.492 | r=-0.284 p=0.287 | r=-0.134 p=0.620 | r=0.117 p=0.667 | r=0.247 p=0.356 | r=0.045 p=0.869 |

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age, years | 1.074 | 1.014-1.138 | 0.015 | |||

| Age, years (≤55 vs. >55) | 7.014 | 1.485-33.139 | 0.014 | 2.502 | 0.302-20.750 | 0.395 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 2.009 | 0.758-5.326 | 0.161 | |||

| Primary tumor location (superior lobes vs. others) | 0.653 | 0.226-1.889 | 0.431 | |||

| Brain metastases location (frontotemporal lobes vs. others) | 1.243 | 0.460-3.361 | 0.668 | |||

| Tumour size (≤3cm vs. >3cm) | 1.552 | 0.585-4.116 | 0.377 | |||

| Stage (IV vs. others) | 2.902 | 0.923-9.128 | 0.068 | 4.896 | 0.890-26.941 | 0.065 |

| Adjuvant therapy (yes vs. no) | 1.161 | 0.538-2.505 | 0.704 | |||

| Mitotic activity primary tumor (≤15 vs. >15) | 0.716 | 0.270-1.901 | 0.502 | |||

| Mitotic activity brain metastases (≤15 vs. >15) | 0.795 | 0.287-2.202 | 0.660 | |||

| PI3K primary tumor | 1.008 | 1.000-1.015 | 0.038 | |||

| PI3K primary tumor; score (≤50 vs. >50) | 7.791 | 1.718-36.432 | 0.008 | 0.864 | 0,058-12.786 | 0.915 |

| PI3K primary tumor; score (<60 vs. 60-150 vs. >150) | 2.295 | 1.135-4.638 | 0.021 | |||

| PINK1 primary tumor | 1.013 | 1.000-1.026 | 0.042 | |||

| PINK1 primary tumor; score (≤90 vs. >90) | 2.589 | 0.992-6.759 | 0.052 | |||

| PINK1 primary tumor; score (<50 vs. 50-100 vs. >100) | 2.236 | 1.109-4.508 | 0.025 | 4.328 | 1.264-14.814 | 0.020 |

| PDL1 primary tumor; score (negative vs. positive) | 2,497 | 0.947-6.585 | 0.064 | 3.210 | 0.768-13.408 | 0.110 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).