1. Introduction

1.1. Urban Regeneration and Their Challenges in Historic Center Areas

Cities constantly evolve, reshaping their built environments in response to economic, social, and political shifts. Urban regeneration, particularly in historic districts or urban central areas, presents a dual challenge: balancing heritage conservation with the need for adaptive reuse. Many cities worldwide have grappled with these complexities, as historic neighborhoods undergo redevelopment, often facing contestation from residents, preservationists, and policymakers (Tiesdell, Oc, & Heath, 1996; Smith, 2006).

Lisbon, like other European capitals, has undertaken ambitious regeneration projects, with Sant’Ana Hill emerging as a focal point of urban transformation. Historically home to some of the city's most significant hospitals, Sant’Ana Hill is now at the center of a redevelopment plan following the decommissioning of these healthcare facilities. Spanning 16 hectares—a larger area than Lisbon’s iconic Baixa Pombalina—the site’s transition raises questions about land use, governance, and public participation in shaping the city's future.

The significance of Sant’Ana Hill extends beyond its architectural heritage; it represents a social and economic lifeline for the communities that have developed around its institutions. The question of how to repurpose these urban voids—whether for housing, commerce, cultural spaces, or tourism—has sparked a highly politicized debate. The current study investigates this process, exploring the contested nature of urban regeneration and the role of participatory planning in reducing uncertainty and fostering sustainable urban development.

1.2. Urban Regeneration, Participation, and the Politics of Redevelopment

Urban regeneration has been the focus of extensive scholarly inquiry within urban planning, architecture, geography, and political science. From debates on neoliberal urbanism to discussions around heritage conservation, the literature underscores the inherently political and contested nature of urban redevelopment. It’s useful thus provide a synthesis of key theoretical perspectives and empirical findings, leading to an examination of how public participation and heritage preservation shape—and are shaped by—urban transformation processes.

1.2.1. Urban Regeneration Perspectives

Conceptual foundations and neoliberal urbanism

Urban regeneration is broadly understood as a deliberate effort to transform degraded, underutilized, or functionally obsolete areas, often through large-scale policy interventions (Roberts & Sykes, 2000; Smith, 2006). Traditionally, this has involved state-led strategies. However, the influence of neoliberal urbanism has progressively shifted the emphasis toward market-driven approaches, privatization, and the commodification of urban space (Harvey, 1989). Critics argue that neoliberal urban policies frequently prioritize economic returns over social equity, thereby exacerbating socio-economic inequalities and displacing marginalized communities (Lees, 2008). This displacement is further fueled by the commodification of housing, which transforms homes into speculative assets, intensifying insecurities for low-income residents (Khalatbari, 2024; Kayıkcı & AYDIN, 2023; Leitner et al., 2022).

Under neoliberalism, market mechanisms play a decisive role. Public-private partnerships (PPPs), urban mega-projects, and deregulation are championed as pathways to efficient development, but they often produce touristification, unaffordable housing and facilitate gentrification (Khalatbari, 2024; Kayıkcı & AYDIN, 2023). The logic of accumulation by dispossession (Ibrahim et al., 2024; Leitner et al., 2022) further illustrates how vulnerable groups lose land, housing, and livelihoods to pave the way for commercial ventures—particularly evident in Global South cities where informal settlements and formal regeneration agendas collide. Moreover, environmental gentrification—where ecological enhancements in degraded areas catalyze real estate speculation—exemplifies how even well-intentioned “green” projects can marginalize the very communities they aim to benefit (Krings & Schusler, 2020; Apostolopoulou, 2023).

Gentrification and its drivers

Gentrification stands out as one of the most visible consequences of this kind of regeneration, entailing the systematic displacement of low-income and marginalized populations (Leitner et al., 2022; Knight & Gharipour, 2016). These processes result not only from housing market pressures but also from broader economic and political forces that undermine marginalized groups’ ability to remain in urban centers. Case studies from Ankara and Jakarta show how urban transformation projects, ostensibly targeting “economic revitalization,” often amplify spatial and social inequalities by creating new “collapsed areas” (Kayıkcı & AYDIN, 2023; Leitner et al., 2022). Furthermore, racial and ethnic dynamics interweave with neoliberal redevelopment, as illustrated in Chester, Pennsylvania, where color-blind ideologies have masked and legitimized exclusionary policies (Mele, 2013).

Public-Private Partnerships and state involvement

With the ascendance of neoliberal governance, public-private partnerships (PPPs) have become a mainstay of urban regeneration. While promoted as innovative solutions to state resource constraints, PPPs have also been criticized for aligning public policy with market imperatives at the expense of public interest. In Israel and China, state-led regeneration programs designed to attract private investment often trigger predatory practices, fostering conflict among state, market, and community actors (Geva & Rosen, 2022; Li et al., 2016). The financialization of regeneration further embeds market logic, as land value capture and planning gain become principal funding mechanisms. Though potentially creative, these models can exacerbate inequalities by depending on market forces to drive development (Thompson & Hepburn, 2022; Vento, 2017). In response, certain experiments with community equity shareholding suggest alternatives that recognize residents’ rights to profit-sharing and genuine decision-making, indicating a possible path toward more equitable regeneration (Bezdek, 2009).

Shifts in State Power and social equity

The neoliberal turn has also reshaped the role of the state, diminishing welfare-oriented frameworks in favor of market-based governance. This transformation affects the distribution of public services and influences who benefits from, or is burdened by, urban redevelopment. Privatization of public amenities, land deregulation, and entrepreneurial governance have often deepened urban inequalities (Baffoe, 2023; Vento, 2017). Yet, case studies like the regeneration of Crumlin Road Gaol and Girdwood Park in Belfast show that state intervention can balance economic growth with social cohesion if designed with inclusive objectives in mind (Muir, 2014). Decentralization and empowering local governments are, moreover, presented as key strategies to democratize planning processes (Li et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2021). The varied outcomes of these interventions underscore the interplay between macro-level forces—such as global capital flows—and local political agency, which can steer projects toward either deeper inequality or greater inclusion.

Social and spatial implications

Ultimately, the literature demonstrates that urban regeneration has mixed impacts on social equity. Policies can exacerbate spatial inequalities and residential segregation, especially in cities with entrenched social, racial or ethnic divisions (Uitermark & Hochstenbach, 2023; Knight & Gharipour, 2016). Environmental gentrification, a subset of these broader processes, manifests when ecological or sustainability initiatives displace low-income populations (Krings & Schusler, 2020; Apostolopoulou, 2023). Nevertheless, some authors propose inclusive planning approaches—incorporating participatory decision-making, social impact assessments, and tenant protections—to offset the adverse outcomes of neoliberal regeneration (Baffoe, 2023; Bezdek, 2009). These calls for equity resonate strongly with critical urban studies, which stress the ethical imperative to safeguard vulnerable communities’ rights to remain in place.

A final layer of complexity in debates on urban regeneration involves heritage preservation. Historic city centers such as those in Barcelona, London, and Paris have witnessed heritage-led regeneration programs designed to adapt historic structures for new cultural or commercial uses (Evans, 2005). These strategies reflect a growing appreciation for the cultural and historical dimensions of urban landscapes; they aim to revitalize neighborhoods while safeguarding local identity and architectural legacy (Pendlebury, 2009). Nonetheless, critics argue that heritage-led initiatives can slip into “museumification” (Zukin, 1995), whereby culturally significant sites become sanitized, tourist-oriented zones disconnected from the needs and values of resident communities. This tension underscores a broader dilemma: how to preserve historical authenticity without contributing to gentrification, commercialization, or the exclusion of local populations.

1.2.2. Public Participation in Urban Planning

Amid mounting critiques of exclusionary urban regeneration, there is growing recognition of the importance of citizen engagement. The field has long referenced Arnstein’s “Ladder of Citizen Participation” (1969), a conceptual touchstone illustrating varying degrees of public influence in planning decisions. Empirical evidence reinforces that inclusive planning processes tend to yield more sustainable outcomes, diminish conflicts, and strengthen local ownership over redevelopment efforts (Innes & Booher, 2004). Yet, in many global cities, participation remains limited or tokenistic, with decisions often consolidated by political and economic elites (Legacy, 2017). In a certain way, this was also the problem that brought us to this study.

Reflecting global pressures, communities worldwide are mobilizing to demand more equitable city-making practices. Urban activism—from Seoul to Cincinnati—asserts a collective “right to the city,” spotlighting how grassroots movements can counteract displacement and advocate inclusive growth (Jung, 2024; Addie, 2009). Community-based equity initiatives, like inclusionary zoning and tenant protection, arise as direct responses to the failures of neoliberal regeneration (Khalatbari, 2024; Bezdek, 2009). These initiatives not only seek to mitigate displacement but also to reframe urban planning around principles of social justice and collaboration. The rise of social justice movements (Krings & Schusler, 2020; Addie, 2009) further demonstrates how public contestation can disrupt dominant narratives that treat urban land primarily as a commodity.

It makes sense to highlight here that there are cases where processes of public involvement and even the design of governance models capable of facilitating and consensualising these transformation dynamics have been conceived. Experiences in cities facing gentrification tensions, such as Berlin or Barcelona, where neighbourhood councils, public-private partnerships and grassroots movements have tried to balance the interests of old and new residents (Eizaguirre Anglada, 2022; Novy & Colomb, 2013).

1.2.3. Heritage Preservation and Adaptive Reuse

A final layer of complexity in debates on urban regeneration involves heritage preservation. Historic city centers such as those in Barcelona, London, and Paris have witnessed heritage-led regeneration programs designed to adapt historic structures for new cultural or commercial uses (Evans, 2005). These strategies reflect a growing appreciation for the cultural, touristic and historical dimensions of urban landscapes; they aim to revitalize neighborhoods while safeguarding local identity and architectural legacy (Pendlebury, 2009). Nonetheless, critics argue that heritage-led initiatives can slip into “museumification” (Zukin, 1995), whereby culturally significant sites become sanitized, tourist-oriented zones disconnected from the needs and values of resident communities. This tension underscores a broader dilemma: how to preserve historical authenticity without contributing to gentrification, touristifcation and the exclusion of local populations.

1.2.4. The Case of Lisbon

This case study is particularly relevant as Portugal, and especially the city of Lisbon, has been facing significant challenges in meeting the housing demands of residents who wish to live in the city.

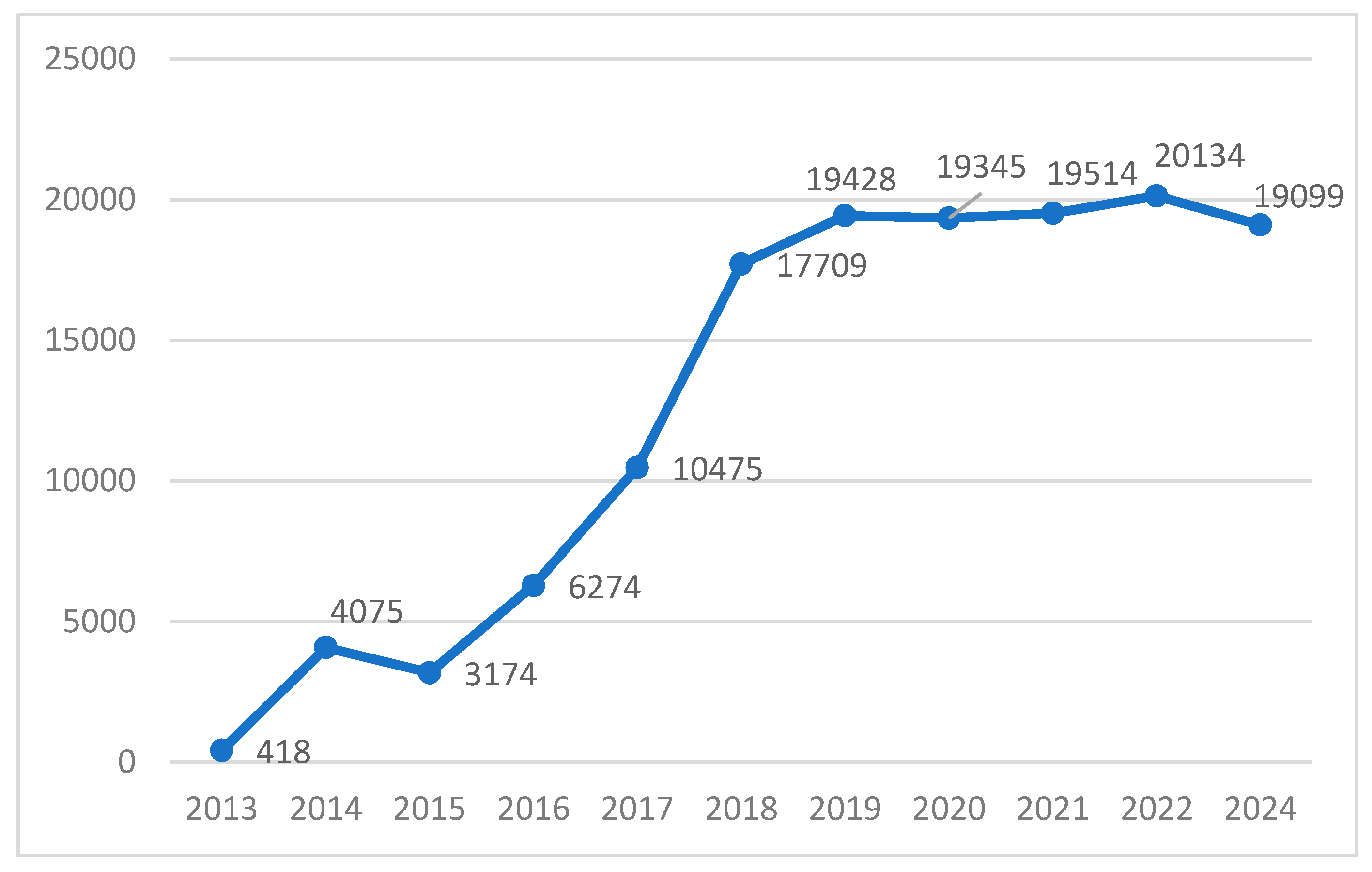

It is important to highlight that Lisbon has been continuously losing population since the 1980s, revealing, among other issues, a persistent difficulty in retaining its residents and attracting new ones. It was only in the last census decade that this negative demographic trend stabilized (cf.

Figure 1).

At the heart of this issue lies the housing supply in terms of quality, availability, and affordability. While in the past, much of the housing stock was in poor condition, leading many residents to seek homes in suburban areas, today’s challenge stems from a different dynamic. Urban regeneration has indeed taken place, but it has been largely driven by tourism-related developments (such as hotels and short-term rentals (cf.

Figure 2)) and high-end residential projects, with prices that are prohibitive for large segments of the population.

On the demand side, access to housing has become increasingly difficult, primarily due to high property prices and rental costs, which effectively exclude both the middle class and more vulnerable communities.

As a result, a climate of heightened tension has emerged between the pressing demand for more affordable housing and, on the other hand, the relentless growth of tourism-oriented and high-end real estate investments.

Thus, Lisbon has been undergoing a rapid transformation, fueled by tourism, foreign investment, and real estate speculation (Mendes, 2017). While projects like the Parque das Nações (Expo 98) and Marvila’s creative hub illustrate successful regeneration cases, other projects—such as the eviction of traditional communities in Alfama—highlight the social consequences of speculative urbanism (Gonçalves, 2022; Seixas & Guterres, 2020). Sant’Ana Hill (cf.

Figure 3) presents a unique case study within this broader trend, given its institutional legacy, central location, and highly contested redevelopment plans.

This case study also has the advantage of confronting a set of dynamics that have historically had a bad relationship in the neoliberal city, such as urban voids, participatory planning and fragile governance.

1.3. Research Gaps and Research Objectives

Over the past few decades, a considerable amount of research has emerged on urban regeneration and the significance of public participation in shaping revitalized cityscapes. Yet, Sant’Ana Hill—a historic district marked by former hospitals and convents—has remained notably absent from these discussions. While scholarly works on Lisbon’s regeneration frequently address residential neighborhoods, they tend to overlook what we might call “institutional urban voids,” or large public complexes whose original functions have lapsed, leaving behind vast, underutilized structures. This lack of attention to institutional spaces is more than a simple oversight: it conceals the critical ways in which these once-pivotal sites can dictate the future social and spatial configuration of surrounding communities.

Another major gap within the literature concerns the governance and decision-making processes that drive, and sometimes hinder, successful urban regeneration. Although a handful of studies hint at the complexity of political negotiations and institutional frictions underlying redevelopment initiatives, the specific nature of these negotiations—especially regarding privatization of public land—remains underexamined. Understanding how different actors, from municipal authorities to real-estate developers, navigate conflicts and converge on decisions is crucial for explaining redevelopment outcomes, yet such analysis is scarce when it comes to Sant’Ana Hill. The absence of a nuanced perspective on policymaking and governance means that we have only a partial view of how power, resources, and interests align to shape urban change.

Alongside these institutional considerations, there is a limited scholarly focus on the role of public contestation and citizen mobilization in influencing Lisbon’s redevelopment projects. Gentrification research has indeed highlighted patterns of displacement and resident resistance. However, few studies have delved into the ways in which public pressure—be it through organized protest, civic advocacy, or direct engagement with planning bodies—can successfully reorient or halt proposed urban transformations, particularly in cases involving public land. By missing this dimension of community-led activism, researchers risk underestimating how collective action can recalibrate governance structures, inject accountability, and shift redevelopment trajectories (Gonçalves, 2022).

It is against this backdrop that the present study aims contribute to fill these gaps. By directing its analytical lens toward the governance frameworks, policy instruments, and forms of public participation that underpin the redevelopment of Sant’Ana Hill, this research seeks not only to illuminate the specificities of one urban space but also to contribute to broader discussions of institutional urban voids, contested land privatization, and the potent forces of grassroots mobilization.

Based on all the reflection made in the previous sections, this research has the following research objectives: i. Analyze the urban transformation of Sant’Ana Hill, examining how institutional, economic, and political factors shape its redevelopment; ii. Investigate the role of public participation in influencing planning decisions and shaping the project’s direction; iii. Evaluate the impact of governance structures on urban planning uncertainty and contested decision-making; iv. Draw lessons for future urban regeneration projects involving heritage sites in central urban areas and large-scale institutional transformations.

1.4. Methodological Notes

To address these objectives, a qualitative case study approach was adopted, integrating multiple data sources, in particular:

Urban Planning Documents: Analysis of key planning frameworks, including the Plano Urbano da Colina de Sant’Ana (PUCS, 2013), the Documento Estratégico de Intervenção (DEICS, 2014), and the Programa Ação Territorial (PATCS, 2016).

Interviews with Key Stakeholders: Semi-structured interviews with urban planners, architects, policymakers, and community representatives.

Media and Public Discourse Analysis: Examination of newspaper articles, public hearings, and political debates on Sant’Ana Hill’s future.

Field Observations: Fieldtrips to assess physical transformations, ongoing projects, and community interactions.

This multi-method approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of the contested urban regeneration process in Sant’Ana Hill, shedding light on the broader implications for urban policy and governance in Lisbon.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design and Approach

This study adopts a qualitative case study approach to analyze the contested urban regeneration of Sant’Ana Hill in Lisbon. Case studies are widely used in urban studies to explore complex social, political, and spatial processes within a specific context (Yin, 2018). Given the multi-layered nature of urban regeneration, this research employs triangulation, combining multiple data sources to construct a holistic understanding of the planning, governance, and participatory dimensions of Sant’Ana Hill’s transformation.

The study follows a retrospective-prospective analysis, integrating Historical and policy analysis (reviewing past and current planning frameworks); Stakeholder perspectives (through interviews and public discourse analysis); Spatial and social observations (assessing the site and its transformation). However, this work is above all exploratory and aims to interpret governance structures, contestation dynamics, and planning implications rather than test a predefined hypothesis.

2.2. Data Collection Methods

To respond to the complexity of the data sources and the methodology itself four key methods were used to gather data:

Documentary and Policy Analysis

Urban regeneration processes are largely shaped by policy frameworks, strategic plans, and legal instruments. This study reviewed key urban planning documents governing Sant’Ana Hill’s redevelopment, including:

Plano Urbano da Colina de Sant’Ana (PUCS, 2013) – defining land use changes and redevelopment strategy.

Documento Estratégico de Intervenção da Colina de Sant’Ana (DEICS, 2014) – refining intervention priorities and participatory frameworks.

Programa Ação Territorial da Colina de Sant’Ana (PATCS, 2016) – defining phased implementation of urban interventions.

Plano Diretor Municipal de Lisboa (PDML, 2012) – outlining broader zoning and development regulations.

Additional legal and municipal reports on heritage conservation, land privatization, and hospital closures were analyzed to understand the legal basis and constraints of redevelopment.

This analysis focused on Land use transformations (what functions were proposed for the former hospitals?); Participatory mechanisms (how was public input integrated into planning decisions?); Policy contradictions (were there inconsistencies between different planning instruments?)

Semi-Structured Interviews with Key Stakeholders

To understand the governance and public contestation process, 12 semi-structured interviews were conducted between December 2023 and January 2024 with Urban planners and architects involved in Sant’Ana Hill’s redevelopment, Municipal officials from the Lisbon City Council’s urban planning department, Representatives of heritage and cultural organizations (ICOMOS-Portugal, Chamber of Architects) and Community activists and neighborhood representatives engaged in public debates.

The interview guide was organized in several main topics: Decision-making processes (Who were the key actors shaping Sant’Ana’s redevelopment?); Public participation (Were residents and advocacy groups effectively involved?); Challenges and conflicts (What were the main sources of contestation?).

Interviews were transcribed and coded thematically, ensuring that diverse perspectives were systematically analyzed.

Media and Public Discourse Analysis

The role of public perception and media coverage in shaping urban transformation was assessed through:

Newspaper articles (2013-2023) from major Portuguese outlets (Público, Expresso, Diário de Notícias) covering Sant’Ana Hill’s redevelopment.

Public debate transcripts from the Debate Temático sobre a Colina de Sant’Ana (DTCS, 2013-2014).

Statements from advocacy groups, petitions, and protest materials from citizen movements opposing the regeneration plans.

The analysis provided some insights into three central dimensions of the contested redevelopment of Sant’Ana Hill. First, it revealed how public discourse framed the urban transformation project, highlighting the narratives, language, and imaginaries employed to present the proposed changes to this historic area. Second, it exposed the complexity of the conflicting narratives that emerged throughout the process, identifying the main arguments both in favor of and against the regeneration plans. Finally, it documented how policymakers navigated these tensions, analyzing their responses to increasing public contestation and illustrating the evolution of institutional positions as the debate intensified.

Field Observations

Fieldtrips to Sant’Ana Hill were conducted to assess current land use and built environment conditions (hospital deactivation, ongoing construction, informal reuse); public space accessibility (are former hospital sites open, fenced, or repurposed?); signs of contestation (graffiti, posters, community-led interventions).

2.3. Data Analysis and Interpretation

The analysis of the collected data followed a thematic approach, integrating multiple methods to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the transformation of Sant’Ana Hill. First, a content analysis of policy documents was conducted to identify inconsistencies in land use policies and governance frameworks, shedding light on areas of misalignment and regulatory ambiguity. In parallel, thematic coding was applied to interviews and public discourse, allowing for the identification of key themes such as governance challenges, contestation, and heritage concerns. Additionally, a comparative analysis of media narratives traced shifts in public perception over time, revealing how discourse surrounding the redevelopment evolved. Finally, spatial analysis, based on field observations, mapped the progress of redevelopment and documented informal community adaptations in response to ongoing changes. This multi-method triangulation not only enhanced the reliability of the findings but also provided a deeper and more nuanced interpretation of the contested transformation of Sant’Ana Hill.

2.4. Limitations and Challenges

A final note is necessary to acknowledge some methodological challenges encountered, which are important to clarify. One of the main obstacles was access to decision-makers. While municipal officials were willing to participate, private developers and investors declined interviews, limiting insights into the economic drivers of regeneration. Additionally, inconsistencies in policy documents posed another challenge, as regulatory frameworks evolved over time, requiring careful cross-referencing across multiple sources. The analysis of media narratives also presented difficulties, as news coverage often reflected editorial biases aligned with different interest groups, influencing the portrayal of the redevelopment process. Furthermore, restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic led to adjustments in the research strategy, with planned in-person engagements with local communities shifting to virtual formats, thereby reducing direct interaction.

Despite all these challenges, the diversity of data sources and the triangulation of methods enhanced the robustness and validity of the findings, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of Sant’Ana Hill’s contested transformation.

3. Results

It's now time to systematise the results of policy analysis, interviews, media discourse and field observations, highlighting the main tensions and contradictions that have shaped the regeneration of Sant'Ana Hill (cf.

Figure 4). The process revealed inconsistencies in urban policies, strong civic opposition, contradictory views on built heritage and persistent governance challenges.

3.1. Urban Planning Framework and Policy Inconsistencies

The transformation of Sant’Ana Hill has unfolded under a multitude of overlapping plans and guidelines, which frequently conflict or lack coherence. The Plano Urbano da Colina de Sant’Ana (PUCS, 2013) first introduced a mixed-use approach, emphasizing hotels, residential space, and cultural facilities. Not long after, the Documento Estratégico de Intervenção da Colina de Sant’Ana (DEICS, 2014) responded to growing public discontent by proposing a more balanced vision, with an explicit focus on heritage preservation. Subsequently, the Programa Ação Territorial da Colina de Sant’Ana (PATCS, 2016) outlined a phased redevelopment strategy; however, slow and inconsistent implementation has undermined its impact.

A key source of confusion stems from the Plano Diretor Municipal de Lisboa (PDML, 2012), which classified hospital sites as “spaces to be consolidated” while subsequent policies designated them for mixed commercial and residential uses. Over time, this shift in land-use priorities from heritage conservation toward real estate development heightened preservationist concerns. Although several planning documents exist, they lack a unifying strategy, making it difficult to coordinate efforts across agencies and stakeholders. The absence of a coherent urban strategy and frequent policy shifts have generated persistent uncertainty and delays in the regeneration process.

3.2. Public Contestation and the Role of Citizen Mobilization

Sant’Ana Hill’s redevelopment has been marked by strong community engagement and, at times, intense public opposition. In 2013–2014, the Lisbon City Council launched the Debate Temático sobre a Colina de Sant’Ana (DTCS), which attracted over 500 participants voicing concerns about displacement, reduced public space, and the loss of centrally located healthcare facilities. However, the debate was non-binding, meaning residents’ and advocacy groups’ inputs were not formally integrated into the final planning decisions. Organizations such as ICOMOS-Portugal and the Chamber of Architects also raised alarms about insufficient heritage safeguards.

Beyond official avenues, citizen-led protests and media campaigns gained traction, particularly in response to demolition plans affecting historically significant hospital buildings. Major newspapers like Público and Expresso often framed these developments as the privatization of public assets, thus amplifying widespread apprehension. Although public pressure did prompt some revisions to planning proposals, citizen engagement largely remained symbolic rather than shaping the fundamental decisions around land use or redevelopment timelines. While public mobilization forced certain changes to planning documents, citizen involvement had limited power to influence core decision-making processes, illustrating the largely symbolic nature of official participation channels.

3.3. Heritage Preservation vs. Real Estate Pressures

One of the most prominent tensions in Sant’Ana Hill’s regeneration is the clash between heritage conservation and economic development. The area contains several architecturally and historically significant sites, such as the Hospital de São José (originating in a 17th-century Jesuit College), the Hospital Miguel Bombarda (noted for its unique circular psychiatric ward), and the Hospital do Desterro (formerly a monastery). Despite their cultural value, these structures face an uncertain future.

Real estate pressures have intensified following government decisions to sell large portions of these hospital sites to the real estate company ESTAMO, effectively transferring ownership from public to private hands. Initial proposals included converting the properties into luxury hotels, high-end apartments, and commercial venues—raising fears of both gentrification and “touristification.” Although some protective measures were introduced, demolition permits were nonetheless granted for select buildings, prompting public backlash and further fueling civic skepticism regarding the sincerity of heritage-preservation efforts. Heritage safeguards have remained secondary to real estate interests, with uneven protection measures across the former hospital sites and ongoing concerns about the commodification of culturally significant buildings.

3.4. Governance Challenges and Political Repercussions

The contested and drawn-out nature of Sant’Ana Hill’s redevelopment has generated broader governance debates and political fallout. Decision-making authority is fragmented between the Lisbon City Council, the Ministry of Health, the real estate public company (ESTAMO), and private developers, resulting in slow approvals, frequent policy reversals, and heightened investment risks. Such bureaucratic delays have only deepened the sense of uncertainty among stakeholders.

Politically, the backlash against hospital privatization on Sant’Ana Hill tapped into wider anxieties about Lisbon’s real estate policies. Opposition parties seized this issue to criticize the government for favoring commercial and tourist-oriented projects over social housing and public services. By 2023, multiple proposed developments remained on hold, reflecting growing distrust among residents and reinforcing perceptions that urban regeneration in Lisbon chiefly serves private interests rather than the broader public good.

Governance inefficiencies and public distrust have stalled redevelopment, revealing the challenges of balancing private-sector investments with transparent and equitable urban planning in Lisbon.

3.5. Final Remarks on the Process

Thus, Sant’Ana Hill’s redevelopment process illuminates a complex interplay of policy fragmentation, intense public engagement, heritage-versus-real-estate debates, and political contention. Despite periodic attempts to reconcile preservationist and economic aims, the absence of a unified strategy and sustained community participation has consistently slowed progress. As such, the case of Sant’Ana Hill underscores the broader need for integrated governance structures, socially attuned urban policies, and genuine public collaboration in shaping the future of historic city spaces.

4. Discussion

Urban regeneration is a complex and contested process shaped by multiple, often conflicting, interests. The transformation of Sant’Ana Hill illustrates the tensions between economic development, heritage preservation, and public participation, revealing broader governance challenges in urban planning. The findings from this study suggest that urban transformation is neither linear nor purely technocratic; rather, it is a negotiated process influenced by power dynamics, institutional fragmentation, and the agency of different stakeholders.

The case of Sant’Ana Hill aligns with international research that highlights the contradictions inherent in urban regeneration projects. While planning frameworks often articulate an integrated vision for redevelopment, the reality is that these visions are subject to modifications, delays, and competing political and economic pressures. As observed in cities like London, Barcelona, and Porto, large-scale regeneration projects frequently shift from publicly driven goals to private-sector priorities, particularly when market forces play a dominant role in shaping the final outcome. In Sant’Ana Hill, the initial planning frameworks emphasized a balance between heritage preservation, social uses, and private investment, yet the eventual trajectory of redevelopment has been marked by an overwhelming prioritization of real estate commercialization, leading to significant public opposition.

The findings also highlight the limitations of public participation in urban planning. While formal mechanisms for civic engagement, such as the Debate Temático sobre a Colina de Sant’Ana (DTCS), were implemented, these participatory processes remained largely symbolic rather than substantive. Citizen concerns were acknowledged but had little impact on the final decision-making process, reflecting the wider phenomenon of tokenistic participation in urban governance. This aligns with Arnstein’s (1969) framework, which distinguishes between genuine citizen empowerment and consultation processes that merely legitimize pre-determined outcomes. Similar trends have been observed in other European cities, such as Berlin’s Media spree redevelopment (Scharenberg & Bader, 2009), where public protests delayed but did not fundamentally alter commercial-driven urban transformation. The case of Sant’Ana Hill illustrates that participatory planning, when not meaningfully integrated into governance structures, does little to reduce public distrust or mitigate conflicts over urban space.

A critical dimension of the Sant’Ana Hill redevelopment is the tension between heritage preservation and real estate pressures. While historic hospital buildings such as São José, Miguel Bombarda, and Desterro hold significant architectural and cultural value, their future remains uncertain due to conflicting urban policies and speculative real estate investment. The privatization of former hospital sites to developers such as ESTAMO underscores a broader trend in which public assets are transferred to market-driven redevelopment projects without a clear framework for safeguarding cultural heritage. This mirrors international cases where heritage-led regeneration has been either successfully integrated or largely undermined. For instance, in Paris, the redevelopment of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul Hospital was framed within a sustainable, mixed-use model, ensuring the adaptive reuse of historical buildings (Appendino et al., 2021). In contrast, in Venice, unchecked commercialization has led to the depopulation and excessive touristification of historic districts, raising concerns about loss of local identity and heritage degradation. The trajectory of Sant’Ana Hill leans more toward the latter scenario, where economic interests appear to override heritage conservation and community-based uses.

Another key challenge in Sant’Ana Hill’s regeneration was the fragmentation of governance structures, which has resulted in delays, policy reversals, and growing public skepticism. The decision-making process has been marked by a lack of coordination between different institutional actors, including the Lisbon City Council, the Ministry of Health, and private developers. This institutional misalignment has led to inconsistent zoning regulations, shifting land-use priorities, and a prolonged lack of clarity over the redevelopment timeline. Similar governance failures have been observed in Madrid’s Canalejas Complex (Mount, 2020), where land-use changes and political contestation delayed regeneration efforts and increased public distrust in urban planning authorities. The case of Sant’Ana Hill underscores the need for stronger institutional coordination, long-term planning consistency, and transparent decision-making processes to prevent uncertainty and ensure that urban transformations align with public interest rather than short-term economic gains.

Considering these findings, there are important policy lessons for urban regeneration projects of this scale. First, participatory planning mechanisms must be institutionalized and binding, ensuring that citizen input directly shapes redevelopment strategies rather than serving as a retrospective consultation tool. This requires a shift from reactive engagement to co-governance, where civil society actors are actively involved throughout the entire urban planning process. Second, urban policy frameworks should establish clear and stable land-use regulations that prevent speculative rezoning and provide greater predictability for both investors and local communities. Third, heritage-led development models should prioritize adaptive reuse strategies, ensuring that historic sites are repurposed for public and social uses rather than being commodified solely for high-end real estate. Finally, institutional governance must be streamlined to avoid bureaucratic inefficiencies and conflicting policy priorities, particularly when large-scale urban transformations involve multiple stakeholders.

In sum, the contested regeneration of Sant’Ana Hill reveals fundamental tensions in urban policy, governance, and public participation. The findings from this study highlight that the long-term success of urban regeneration depends not only on economic viability but also on the ability to integrate inclusive governance models, transparent decision-making, and sustainable heritage management practices. As Lisbon continues to undergo rapid urban transformation and suffering one of the most acute housing crises in OECD countries, the lessons from Sant’Ana Hill’s case provide valuable insights for ensuring that future regeneration projects prioritize social equity, cultural preservation, and democratic planning processes.

5. Conclusion

The contested regeneration of Sant’Ana Hill in Lisbon serves as a critical case study in urban transformation, highlighting the complex interplay between governance structures, public participation, and heritage preservation. As this study has demonstrated, the redevelopment of the former Health Hill has been shaped by policy inconsistencies, limited citizen engagement, real estate pressures, and governance fragmentation, ultimately generating significant public resistance and uncertainty.

One of the key findings of this research is that urban planning is inherently a negotiated process, often caught between competing visions of development. In the case of Sant’Ana Hill, initial urban plans emphasized a balanced approach integrating heritage, social infrastructure, and economic revitalization. However, over time, the prioritization of commercial real estate development over public-oriented land uses has led to widespread opposition from both civil society groups and urban researchers. This pattern aligns with broader international experiences in urban regeneration, where heritage-led policies frequently come into tension with market-driven redevelopment strategies.

Another important takeaway from this study is the role of public participation in shaping urban transformation. While formal participatory mechanisms, such as the Debate Temático sobre a Colina de Sant’Ana (DTCS, 2013-2014), were implemented, they remained largely symbolic rather than substantive. The findings support existing research on urban governance, which suggests that tokenistic public consultation processes often fail to build trust or meaningfully influence planning outcomes. This raises the need for more inclusive and binding participatory frameworks, ensuring that citizen engagement is not merely a procedural requirement but a core component of urban policymaking.

The conclusions also underscore the need for clear and consistent governance mechanisms in large-scale urban regeneration projects. The case of Sant’Ana Hill has been characterized by institutional fragmentation, with conflicting priorities between the Lisbon City Council, the Ministry of Health, and private developers. This lack of coordination has resulted in delays, policy reversals, and a growing perception of opacity in decision-making. Similar governance failures have been documented in other European cities undergoing rapid urban transformation, reinforcing the necessity for long-term planning consistency, transparent regulatory frameworks, and cross-institutional collaboration.

From a policy perspective, the case of Sant’Ana Hill provides several important lessons. Future urban regeneration efforts must prioritize heritage-led development models that integrate adaptive reuse, public space preservation, and cultural sustainability. At the same time, urban policies should establish mechanisms to prevent speculative rezoning and uncontrolled privatization of public assets, ensuring that economic development does not come at the expense of social equity and historical preservation. Moreover, governance structures must be reformed to streamline decision-making, reduce bureaucratic inefficiencies, and enhance democratic accountability in urban transformations.

Beyond its immediate implications for Lisbon’s urban policy, this study contributes to broader academic discussions on urban voids, contested redevelopment, and participatory governance. As cities worldwide confront the challenges of repurposing underutilized institutional spaces, the findings from Sant’Ana Hill offer valuable insights into how urban transformations can be made more equitable, transparent, and sustainable. Future research could expand on this case by conducting comparative analyses with similar contested regeneration projects, examining longitudinal impacts of urban redevelopment, and exploring alternative governance models that successfully integrate public participation and heritage conservation.

Finally, the case of Sant’Ana Hill illustrates the fundamental tensions that define contemporary urban regeneration efforts. As Lisbon continues to evolve, the ability to balance economic imperatives with social and cultural sustainability will determine whether the city’s future transformations serve as models of inclusive and participatory urban planning or cautionary tales of speculative redevelopment. The lessons drawn from this research emphasize that successful urban regeneration must be driven not only by financial viability but also by a commitment to democratic governance, heritage protection, and long-term social inclusivity.

References

- Addie, J. P. D. (2009). Constructing neoliberal urban democracy in the American inner-city. Local Economy, 24(6-7), 536-554. [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, E. (2023). Navigating neoliberal natures in an era of infrastructure expansion and uneven urban development. Journal of Regional Research, (55), 113-126. [CrossRef]

- Appendino, F., Roux, C., Saadé, M., & Peuportier, B. (2021). Towards Circular Economy Implementation in Urban Projects: Practices and Assessment Tools 1. In Transformative Planning(pp. 177-194). Routledge.

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 35(4), 216-224.

- Baffoe, G. (2023). Neoliberal urban development and the polarization of urban governance. Cities, 143, 104570. [CrossRef]

- Bezdek, B. (2016). Putting community equity in community development: Resident equity participation in urban redevelopment. In Affordable housing and public-private partnerships (pp. 93-128). Routledge.

- Colomb, C. (2017). Participatory governance and urban sustainability: The case of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul Hospital in Paris. Urban Studies, 54(10), 2208-2230.

- Eizaguirre Anglada, S. (2022). Cultural commons as a key for bottom-linked policies. A look at the support for public and community partnerships in Barcelona. On the Waterfront. The International on-line Magazine on Waterfronts, Public Art, Urban Design and Civil Particiapation, 2022, vol. 64, num. 12, p. 3-39.

- Evans, G. (2005). Measure for measure: Evaluating the evidence of culture’s contribution to regeneration. Urban Studies, 42(5-6), 959-983.

- Ferreira, A., Silva, C., & Mendes, L. (2021). Between urban regeneration and gentrification: The case of Porto’s Ribeira district. European Planning Studies, 29(3), 435-455.

- Geva, Y., & Rosen, G. (2023). In search of social equity in entrepreneurialism: The case of Israel’s municipal regeneration agencies. European Urban and Regional Studies, 30(1), 36-49. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J. (2022). The Battles around Urban Governance and Active Citizenship: The Case of the Movement for the Caracol da Penha Garden. Sustainability, 14(17), 10915.

- González, S. (2019). Madrid’s Canalejas Complex: The politics of real estate-led urban transformation. City, 23(4-5), 618-637.

- Harvey, D. (1989). The condition of postmodernity: An enquiry into the origins of cultural change. Blackwell.

- Healey, P. (2007). Urban complexity and spatial strategies: Towards a relational planning for our times. Routledge.

- Holm, A. (2010). Berlin’s Mediaspree: Gentrification and resistance in the creative city. City, 14(1-2), 170-180.

- Ibrahim, A. S., Abubakari, M., Cobbinah, P. B., & Kuuire, V. (2024). Accumulation by dispossession and the truism of urban regeneration. Journal of Planning Literature, 39(4), 548-562. [CrossRef]

- Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (2004). Reframing public participation: Strategies for the 21st century. Planning Theory & Practice, 5(4), 419-436.

- Janoschka, M., Sequera, J., & Salinas, L. (2014). Gentrification in Spain and Latin America—a critical dialogue. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1234-1265.

- Jung, C. (2024). Jung, C. (2024). Neoliberal urban redevelopment and its discontents: rising urban activism in Seoul. In Handbook on Urban Social Movements (pp. 330-343). Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Kayıkcı, H., & AYDIN, Y. (2023). Urban Transformation and Gentrification from the Perspective of Different Stakeholders: The Case of Ankara, Yenimahalle Mehmet Akif Ersoy Neighborhood. TSBS Bildiriler Dergisi. [CrossRef]

- Khalatbari, A. (2024). A Critique of Neoliberal Urbanization and its Downsides on Housing Policies. Preprints: . [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. M., & Gharipour, M. (2016). Urban displacement and low-income communities: The case of the American city from the late twentieth century. ArchNet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research, 10(2), 6. [CrossRef]

- Krings, A., & Schusler, T. M. (2020). Equity in sustainable development: Community responses to environmental gentrification. International Journal of Social Welfare, 29(4), 321-334. [CrossRef]

- Lees, L. (2008). Gentrification and social mixing: Towards an inclusive urban renaissance? Urban Studies, 45(12), 2449-2470.

- Legacy, C. (2017). Is there a crisis of participatory planning? Planning Theory, 16(4), 425-442.

- Leitner, H., Sheppard, E., & Colven, E. (2022). Market-induced displacement and its afterlives: Lived experiences of loss and resilience. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 112(3), 753-762. [CrossRef]

- Mele, C. (2013). Neoliberalism, race and the redefining of urban redevelopment. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(2), 598-617. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L. (2017). Gentrification and touristification in Lisbon: The global context of local urban change. Urban Research & Practice, 10(1), 1-14.

- Mount, I. (2020). A bid for Madrid; European property/Parts of the city had become faded but now some of its glories have been given new life as luxury residences. By Ian Mount. The Financial Times, 3-3.

- Muir, J. (2014). Neoliberalising a divided society? The regeneration of Crumlin Road Gaol and Girdwood Park, North Belfast. Local Economy, 29(1-2), 52-64. [CrossRef]

- Novy, J., & Colomb, C. (2013). Struggling for the right to the (creative) city in Berlin and Hamburg: New urban social movements, new ‘spaces of hope’?. International Journal of urban and regional research, 37(5), 1816-1838.

- Pendlebury, J. (2009). Conservation in the age of consensus. Routledge.

- Roberts, P., & Sykes, H. (2000). Urban regeneration: A handbook. SAGE Publications.

- Russo, A. P. (2002). The “vicious circle” of tourism development in heritage cities. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 165-182.

- Scharenberg, A., & Bader, I. (2009). Berlin’s waterfront site struggle. City, 13(2-3), 325-335.

- Seixas, J., & Guterres, H. (2020). The social and spatial effects of tourism-led urban transformation in Lisbon. Urban Studies, 57(9), 1832-1851.

- Smith, N. (2006). The new urban frontier: Gentrification and the revanchist city. Routledge.

- Tallon, A. (2013). Urban regeneration in the UK. Routledge.

- Tarazona Vento, A. (2017). Mega-project meltdown: Post-politics, neoliberal urban regeneration and Valencia’s fiscal crisis. Urban Studies, 54(1), 68-84. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M., & Hepburn, P. (2022). Self-financing regeneration? Capturing land value through institutional innovations in public housing stock transfer, planning gain and financialisation. Town Planning Review, 93(3), 251-274. [CrossRef]

- Tiesdell, S., Oc, T., & Heath, T. (1996). Revitalizing historic urban quarters. Architectural Press.

- Uitermark, J., Hochstenbach, C., & Groot, J. (2024). Neoliberalization and urban redevelopment: The impact of public policy on multiple dimensions of spatial inequality. Urban Geography, 45(4), 541-564. [CrossRef]

- Wong, S. W., Chen, X., Tang, B. S., & Liu, J. (2024). Neoliberal state intervention and the power of community in urban regeneration: An empirical study of three village redevelopment projects in Guangzhou, China. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 44(2), 619-631. [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. SAGE Publications.

- Zukin, S. (1995). The cultures of cities. Blackwell.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).