1. Introduction

Video surveillance systems are installed in public areas such as airports, railway and metro stations, malls, banks, and schools, as well as in key and high-traffic locations to ensure the safety of numerous people, infrastructure, and equipment, and to maintain the uninterrupted function of these facilities.

In public spaces like airports, one of the primary security risks is abandoned luggage, which can potentially threaten public safety and disrupt normal operations. Detecting unattended luggage in airports, or luggage suspected of having been left behind and potentially representing a security threat, is a challenging task, especially given that these spaces are often overcrowded, with large numbers of people entering, moving in different directions, and leaving while carrying, pulling, pushing, or standing next to various items of luggage.

Traditional surveillance methods rely on continuously monitoring airport buildings and surrounding areas through many surveillance cameras and heavily depend on human operators. These operators must maintain a high level of concentration to continuously monitor multiple screens to identify and raise alarms about potentially abandoned luggage. Due to fatigue and reduced alertness, the likelihood of oversight or poor judgment increases, necessitating large monitoring teams to ensure the area remains secure. Consequently, there is a growing demand and need for automated security surveillance systems.

Over the last decade, various approaches involving the automatic detection and localization of potentially abandoned luggage within a camera’s field of view have been actively researched. However, today’s object detection methods, such as the YOLO family, offer far more accurate real-time detection of objects of interest across diverse real-world scenes and application domains, thereby significantly enhancing security processes. Historically, luggage detection relied on traditional computer vision methods—like feature extraction and classifiers such as SVM—combined with background substruction and motion analysis. The effectiveness of these methods is considerably limited in dynamic environments, due to their sensitivity to changes in lighting, crowd density, viewing angles, and complex backgrounds.

In this work, popular architectures of deep convolutional neural networks for object detection such as YOLOv8 and YOLOv11 and DETR encoder-decoder transformer with a ResNet-50 deep convolutional backbone were used, and fine-tuned for domain shift on our custom dataset for detecting people and luggage in surveillance scenes. We compared their performance and all fine-tuned models significantly improved their performance in detecting people and luggage in surveillance scenes. Both the YOLOv8 and YOLOv11 fine-tuned models achieved excellent results on a demanding set consisting of only small and medium-sized objects in real time. The YOLOv11-l model, however, achieved significantly higher accuracy in detecting small objects than the YOLOv8 large-scale versions of the model, which is why we selected it as a component of the abandoned luggage detection system.

The primary contributions of this research are as follows:

Two custom datasets, Korzo and Düsseldorf, capturing diverse real-world scenarios in public spaces with annotation of people and luggage,

Fine-tuned Yolov8, YOLOv11 and DETR models for detecting people and luggage in surveillance camera footage,

Performance analysis of variants of the fine-tuned YOLOv8 and YOLov11 family of models on a demanding set of visual scenes consisting only of small and medium-sized objects,

A fine-tuned YOLOv11-l person and language detection model that achieves mAP precision of 71% in demanding surveillance camera scenarios, including medium object precision AP_medium of 94% and small object precison, AP_small of 69%

Abandoned luggage detection algorithm utilizing temporal and spatial analysis of object detection and tracking to conclude luggage ownership/responsibility and recognize abandonment luggage effectively.

The paper begins with a review of the field, followed by a description of the proposed system and defined algorithm for abandoned luggage detection in

Section 3. In

Section 4 key phases of development of abandoned luggage systems are presented followed by description of custom models fine-tuning in

Section 5., description of the custom datasets in

Section 6, and evaluation of results in

Section 7. Implementation of the proposed algorithm and different scenarios of abandoning luggage are discussed in

Section 8. Paper ends with a conclusion.

2. Related Work

The task of detecting abandoned luggage in video surveillance can be divided into two main phases: the first involves identifying both the luggage and its owner in a video frame, while the second assesses the likelihood that the luggage is truly abandoned based on the gathered information. Traditional approaches to luggage and owner detection frequently relied on background subtraction methods, which are straightforward to implement yet ill-suited for complex scenes with numerous moving objects [

1]. One of the earlier approaches utilized a Markov Chain Monte Carlo model with Bayesian networks for luggage detection [

2]. Although effective under controlled conditions, this method was limited in adapting to more complex and dynamic scenarios. The analysis of background changes over time was applied in [

3] to detect stationary objects, a technically interesting approach but extremely sensitive to variations in lighting and camera vibrations, leading to a high false-positive rate. In [

4], foreground segmentation was used to identify stationary objects and generate candidates for abandoned luggage, thereby reducing false positives. Nevertheless, it was not sufficiently robust in real-world dynamic environments.

More advanced approaches have integrated traditional methods with convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which are adapted to a broad range of computer vision tasks such as classification, object detection, and image segmentation [

2]. In [

5], a hybrid approach was introduced, combining background subtraction for detecting static objects with a CNN for identifying abandoned luggage. This method achieved significant performance in controlled environments, reducing detection errors and improving accuracy. However, the computational requirements of such solutions remain a challenge in real-world applications.

Modern approaches rely on deep CNNs that are well-suited for a wide range of computer vision tasks [

2], and in this context are used for detection or tracking in images or videos captured by surveillance cameras. Briefly, detectors can be categorized into one-stage and two-stage. In one-stage models such as YOLO (You Only Look Once), the entire detection process (localization and classification) takes place in a single pass through the network [

2]. In contrast, two-stage approaches (e.g., the Faster R-CNN) first generate regional proposals and then perform classification and coordinate regression, which leads to higher computational demands and longer processing times [

6]. Due to the real-time inference capabilities and relatively high detection accuracy in complex and dynamic scenarios, YOLO-based models (e.g., YOLOv5 and YOLOv8) are increasingly employed in security systems [

4,

7,

8,

9,

10]. A summary of relevant research is given in

Table 1.

Also, it should be noted that surveillance scenes typically feature numerous small objects that occupy only a few pixels in each image. This characteristic presents two main challenges such as difficulty in distinguishing small objects from background noise and increased susceptibility to occlusion, so that the justified requirements for the model implemented in the surveillance system are real-time performance capabilities and proficiency in detecting small and medium-sized objects. These features are essential for effective surveillance, ensuring that the system can accurately identify and track objects of interest, even when they are small or partially obscured, while maintaining the speed necessary for real-time monitoring and responses. But, as noted in [

14], many CNN models still struggle with this very problem since during down-sampling CNN-based architecture loses critical spatial details. However, it was showed that Faster R-CNN was the top-performing architecture for small object detection, and YOLO was the second-best option [

14] but with significant speed advantage that makes the YOLO model far more suitable for real-time applications, such as surveillance systems, where rapid detection is critical. For this reason, in our experiments we also selected the best YOLO models that achieve excellent performance in real time with an emphasis on the detection of small objects.

3. Proposed Luggage Detection System

The proposed abandoned baggage detection system uses video footage collected from CCTV cameras at the airport, a customized deep CNN model for real-time automatic detection of people and baggage in surveillance camera images, and the defined algorithm for recognizing abandoned baggage and raising an alarm to a security team.

The assumption is that some people may have one or more pieces of luggage, while others may be without luggage. Also, luggage does not move around the airport building on its own, either being pulled or carried by a person or being transported by a person on a vehicle or train. Therefore, it is possible that someone could have brought the luggage to a location, and if they left the luggage there unattended, the luggage is considered abandoned.

Prior to developing the algorithm for recognizing abandoned luggage it is necessary to define rules that determine when and under what conditions luggage is considered abandoned and a potential security threat.

-

A.

Definition of Abandoned Luggage

For luggage to be classified as abandoned in the proposed system, two criteria must be met:

-

1.

The luggage must be unattended—all individuals who were within a predefined radius around the luggage at the time of its initial detection must have moved out of that radius.

-

2.

The luggage must remain in the same location for a specified period.

When both conditions are satisfied, i.e., the luggage is left unattended outside a predefined radius and has remained stationary for a certain time greater than the duration set in the system, then the system marks the luggage as abandoned. These conditions are set to include all possible cases that may exist between people, the owner of the luggage, and the luggage, and to reduce the number of false positive detections.

For instance, if a person is waiting in a queue with luggage placed in a certain spot for some time while remaining nearby, the luggage is presumed to be supervised, linked to that individual, and therefore neither abandoned nor identified as suspicious.

It is also possible for an entire group to move together, with some or all members carrying their own luggage (

Figure 1.). If one or several members of the group leaves while leaving their luggage behind with the others, the luggage is still considered under the group’s supervision. Consequently, such a scenario would not be flagged as suspicious.

-

B.

System and Algorithm for Abandoned Luggage detection

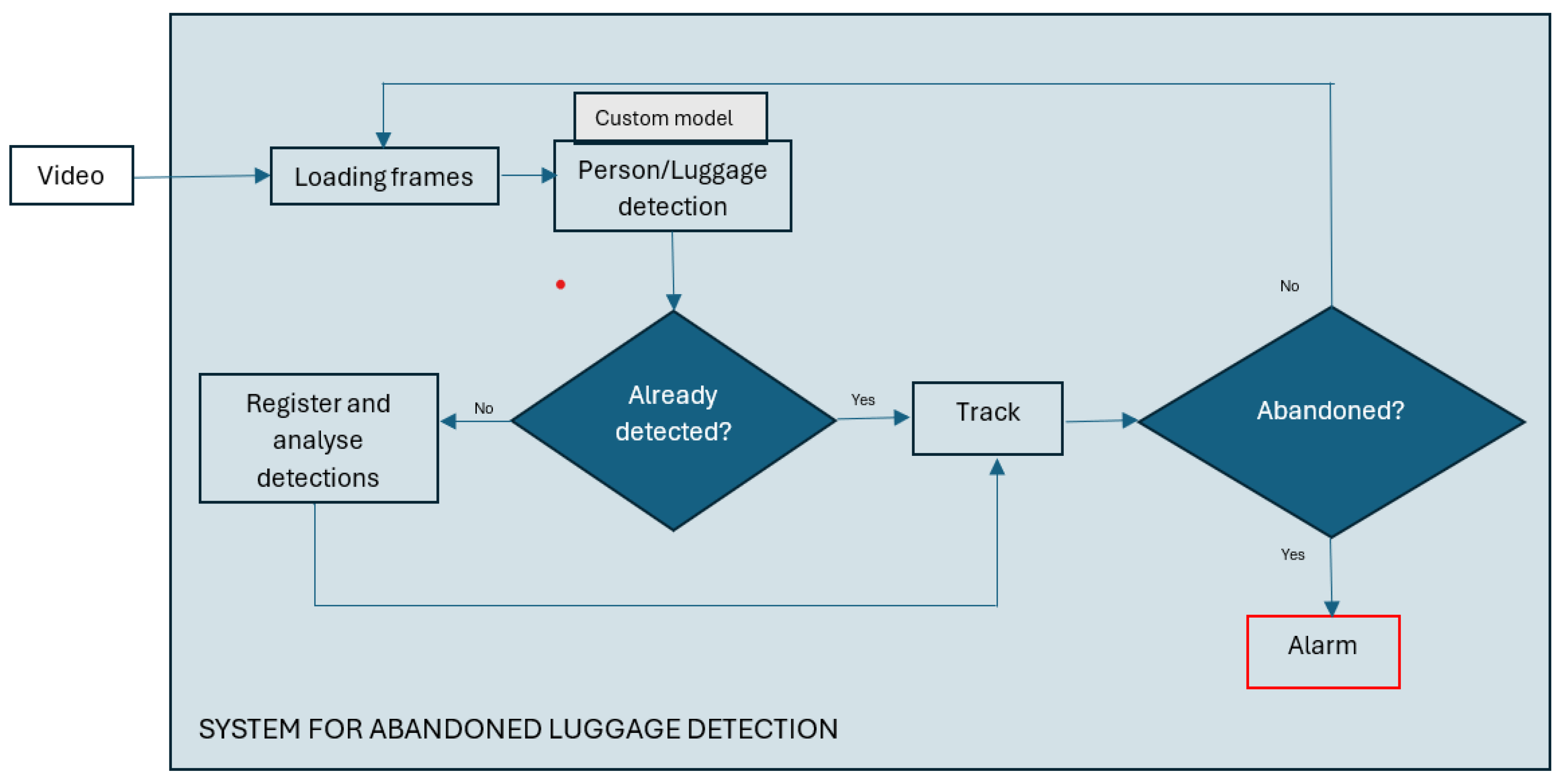

The system components for abandoned luggage detection are shown in

Figure 2.The system loads video stream from a surveillance camera and then takes frames from the video every 0.25 s in order not to lose useful information from the footage and to speed up image analysis. Each extracted image is the input to a customized object detector that detects all people and luggage in the input image that is in the camera’s field of view. For tracking detected objects across frames, we use YOLOv11’s default multi-object tracking algorithm, ByteTrack. ByteTrack works by associating detections frame by frame, keeping high-confidence detections while also considering low-confidence ones to improve tracking stability. This approach ensures better object identity persistence and reduces tracking errors in complex environments, enabling robust monitoring of luggage movement and ownership status [

11] . It is crucial for the detection model to accurately identify people and luggage in real time with a high response rate, ensuring that no potentially suspicious objects go undetected.

The system then uses an algorithm to identify abandoned luggage based on an analysis of the spatial and temporal dynamics of the luggage and identifying situations in which the luggage has been left unattended. The first processing step involves the initial detection of people and luggage, assigning each detected object a unique ID. A limit has been set that the size of objects to be detected and tracked should be greater than 20 pixels because very distant objects that occupy only a few pixels cannot be successfully detected in the image, and it is assumed that they will be better visible on another camera that is closer to them. This limit is specific to the system and can be adjusted according to the parameters of each system, considering the limitations of the detector.

Then, the system checks which people are within a defined radius of the luggage and maps that luggage to one or more people nearby. For each subsequent frame, the system checks whether the persons initially detected near the luggage are still within its radius, meaning whether the luggage remains under their supervision.

Pseudocode of algorithm is:

INITIALIZATION:

- Load tracking model

- Define parameters:

- Threshold time (T_threshold)

- Ownership radius (R_own)

-Movement Threshold (M_treshold)

START CAMERA FEED:

WHILE True: # Continuous video processing loop

- Capture frame from the camera

- Detect and track objects using fine-tuned model

- Extract tracked objects (ID, class, bounding box)

- Register detected objects

IDENTIFY PERSON-LUGGAGE INTERACTIONS:

- For each detected luggage:

- Check if a tracked person is within R_own

- If a person is found:

- Associate the luggage with them

- If no person is found:

- Start the abandonment timer

DETECT ABANDONED LUGGAGE:

- If luggage is unassociated for more than T_threshold:

- Mark it as abandoned

- Trigger an alert (e.g., visual warning, alarm)

-Log alarm data

The system continuously monitors the location of the luggage and the IDs of the people to whom it is mapped, as well as other people entering the surveillance radius. If the luggage is in the same place for longer than the set limit, and all associated persons leave that radius, the system classifies the luggage as abandoned. Baggage is considered under supervision if there is at least one person in whose ownership it is near it. In addition, to reduce the number of false detections, the system compares coordinates from multiple consecutive frames to filter out minor camera movements or vibrations and ignores luggage that is in motion, as it is assumed to be towed by the owner or transported by vehicle or automated conveyor belt.

-

C.

Key Algorithm Parameters

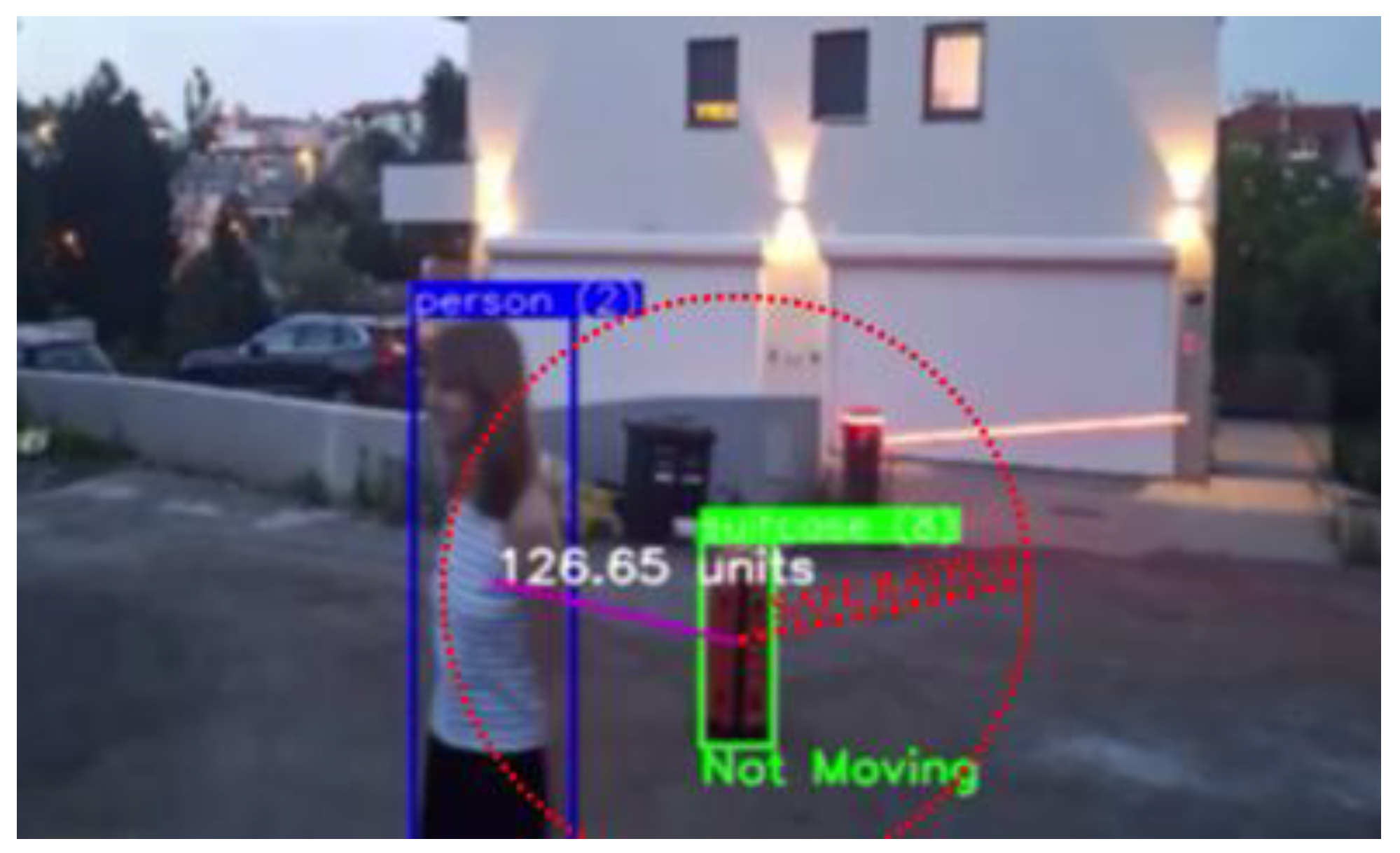

The key parameters in the algorithm for detecting abandoned luggage include the movement threshold, the radius of association (i.e., the distance between a person and the luggage) (

Figure 3.), and the duration the luggage remains stationary. These parameters are defined in advance based on the system configuration but can be adjusted to the specific characteristics of the environment and technical recording conditions to improve the accuracy of abandoned luggage detection.

The movement threshold specifies the minimum displacement, measured in pixels, that luggage must undergo to be considered in motion. This effectively prevents false detections caused by noise or camera vibrations, while still reliably identifying actual movement. In practice, the luggage coordinates are stored for several previous frames, and if the difference in position exceeds the predefined threshold, the system concludes that the luggage is moving.

In this system, a luggage ownership radius of 40px is suggested (height of average person detection), but this is a measure that can be adjusted for each system depending on the camera feed as size of objects vary depending on the distance. In this system, the time that is set for the luggage to be unattended is 10s, but this is also flexible and should be adjusted according to the system requirements.

Camera placement, angle, and distance from the scene also affect how the radius of association is determined, since perspective and a distant camera angle limit the level of detail, making detected objects appear smaller and closer to each other compared to close-up footage. Consequently, this parameter must be adapted to real-world conditions to reduce false alarms and enhance the overall accuracy of the system. For example, in crowded spaces, a smaller radius of association can help avoid unnecessary links between luggage and random passersby. Conversely, a larger radius may be suitable for less crowded areas, where people typically stand further apart than in congested settings where they are forced closer together.

4. Development of Abandoned Luggage System

The development of the proposed system for detecting abandoned luggage comprises three key phases.

The first phase involves collecting and labeling images from real-world surveillance camera environments, thereby creating customized datasets for transfer learning across various public-space scenarios. The collected images are manually labeled to precisely identify objects such as luggage, persons, and other relevant objects, ensuring a reliable foundation for training the model.

The second phase centers on selecting an appropriate model architecture and training the object detection model—namely, fine-tuning it for detecting people and luggage captured by surveillance cameras, based on these customized datasets. It is essential that the model achieves high accuracy in detecting people and luggage, remains robust enough to perform well across diverse settings and under varying recording conditions and is capable of real-time inference.

The third phase encompasses defining and implementing the algorithm for recognizing abandoned luggage.

5. Model for People and Luggage Detection

In the context of abandoned luggage detection, it is crucial to achieve high precision and recall while operating in real time. Over the past several years, YOLO-family detectors have excelled in these areas, but the performance of visual transformers is also improving and achieving comparable results in the area of object detection.

-

A.

YOLOv8 and YOLOv11 families

The YOLO architecture is based on a CNN that divides the input image into a grid of cells, with each cell simultaneously predicting bounding box coordinates, a confidence score, and object classes [

7]. YOLO is a single-stage object detection method and has been in development since 2016, with two models being developed annually. One of the latest versions is YOLOv11 [

16], and due to its excellent performance, YOLOv8 [

17] is still very popular today. YOLOv8 was designed by the original YOLO team with a focus on improving the performance of real-time detection of complex objects of varying sizes. YOLOv8 introduces a new dynamic prediction scheme that adjusts the number of model predictions according to image complexity resulting in reduced inference time and computing requirements. YOLOv8 includes several new optimizations, such as improved loss functions and better regulation, and a new pyramidal network architecture feature that improves detection accuracy on small objects without compromising detection accuracy on larger objects. YOLOv11, is developed in 2024, using the Ultralytics Python package, and achieves higher accuracy with fewer parameters through innovations in model design and optimization techniques. Architectural innovations of the model, include the introduction of C3k2 (Cross Stage Partial with kernel size 2) block, SPPF (Spatial Pyramid Pooling—Fast) and C2PSA (Convolutional block with Parallel Spatial Attention) components, which contribute to the improvement of feature extraction [

16].

Both YOLOv8 and YOLOv11 families of models come in different versions that are a tradeoff between computational complexity and model performance, starting from computationally lighter models (e.g., YOLOv8 Nano) to those with 20 times as many parameters (e.g., YOLOv8XL).

In recent years, the goal of YOLO model development has been to extract and process features as efficiently as possible, while maintaining high accuracy [

16,

17]. The design of the YOLOv11 model has resulted in higher average precision (mAP) on datasets such as COCO, so that, for example, with 20% fewer parameters it achieves even slightly better results than YOLOv8m. That is, with the same number of parameters as YOLOv8m it achieves 3% higher average precision., which roughly corresponds to the results achieved by the largest YOLOv8x model. A comparison of different versions of the YOLOv8 and YOLOv11 models is given in

Table 2. All models are pretrained on the COCO dataset and more complex version of models of each family achieve higher accuracy but require more powerful computational resources [

2].

The results that the YOLOv8 and YOLO11 models achieve on the COCO validation set potentially make them an excellent choice for our real-time detection scenario on surveillance camera footage and allow for efficient implementation on resource-constrained devices, without compromising accuracy.

We tested all versions of YOLOv8 and v11 models for inference speed on our computer (

Table 2). The slowest are the x models with a processing speed of about 36 ms, which is approximately 28 frames per second, so they can be considered too slow or borderline acceptable for surveillance systems. All remaining YOLO models achieve inference speeds of less than 24 ms, which is approximately 42 frames per second. Since the human eye is considered to perceive motion as smooth at about 24 frames per second, 42 frames or more is definitely an appropriate speed for surveillance systems.

-

B.

DETR ResNet-50

The DEtection TRansformer (DETR) [

12] with ResNet-50 backbone is a transformer-based object detection model developed by Facebook AI. It has 41 million parameters and is pretrained on the COCO dataset. DETR replaces traditional object detection components with an end-to-end set prediction approach. It utilizes a bipartite matching loss for direct object detection without post-processing. The model efficiently captures long-range dependencies and contextual relationships in images which makes it potentially interesting for our detection task.

Table 2 shows that DETR model has the similar number of parameters as the YOLOv11x model or YOLOv8l, but achieves 8% less accuracy, and also requires 93.6 ms per frame for inference, which is 10 FPS, making it unsuitable for real-time inference.

We also considered the model’s robustness considering the need for domain shift [

2], a situation where the distribution of the training data differs from that of the real-world environment. In our case, our models were trained on the COCO dataset but are intended for airport scenes recorded by surveillance cameras from a bird’s-eye view. To mitigate the effects of domain shift and varying recording conditions, and to adapt the model to the target domain, we employed transfer learning, which simplifies the transition from one image type to another while reducing both training time and the need for a large volume of manually annotated samples [

2,

3,

10].

Considering previous experiences with tuning the YOLOv8 model for images captured from a bird’s eye view [

18] as well as the performance that the models achieve in real time, we selected the YOLOv8m and YOLOv11m models for further testing on domain shift of object detection in surveillance camera images.

6. Custom Dataset of Public Places

To adapt the detection model to the specific conditions and surveillance camera perspectives within airport buildings, two custom datasets were created, sourced from two primary locations: Rijeka’s Korzo, Croatia and Düsseldorf Airport, Germany.

-

A.

CCTV-Korzo Dataset

This dataset contains images of outdoor scenes captured by a surveillance camera on Rijeka’s Korzo, the city’s main promenade, featuring people in motion (

Figure 4.). The CCTV-Korzo dataset comprises

60 images. These images were annotated such that there are

559 person detections and only

50 luggage detections. Images were an average size of 942x526 pixels and resized to 640x640 pixels. Augmentation processes were made such as: horizontal flipping, saturation shifts between -25% and +25%, exposure adjustments between -10% and +10%, and adding noise up to 0.1% of pixels, with augmentation the dataset was expanded to

150 images.

Although the CCTV-Korzo dataset has a relatively small number of luggage images (around 8% of the total detections), it is valuable because it contains perspectives that closely resemble footage from surveillance cameras in public spaces.

-

B.

CCTV-Düsseldorf Dataset

The CCTV-Düsseldorf dataset includes images captured indoors at different times of day and under various lighting conditions (

Figure 5.). It consists of

178 images with an average size of 1692x614 pixels. These images have been annotated to include a total of

2,117 person detections and

830 luggage detections. Images were resized to 640x640 and augmentation processes such as horizontal flipping, rotation between -13° and +13°, hue shifts between -21° and +21°, and exposure adjustments between -5% and +5% were applied, and the dataset was expanded to 300 images. This dataset has proven to be significantly more suitable for luggage detection from a surveillance camera perspective. A milder augmentation strategy was chosen because the dataset already contains a diverse range of indoor scenes and a higher number of luggage detections, thereby reducing the need for additional variations that might compromise data quality.

7. Evaluation of Fine-Tuned Person and Luggage Detection Models

The original versions of the YOLOv8m, YOLOv11m and DETR(Resnet-50) models were fine-tuned on the prepared datasets CCTV-Korzo (K), CCTV-Düsseldorf (D), and a combined CCTV-Korzo+Düsseldorf (KD) set, and then all models were tested on the test set collected at Dusseldorf Airport that none of the models had seen these videos before.

We also compared the results with the original versions of the models to determine how much the training of the models helped in domain adaptation and performance improvement.

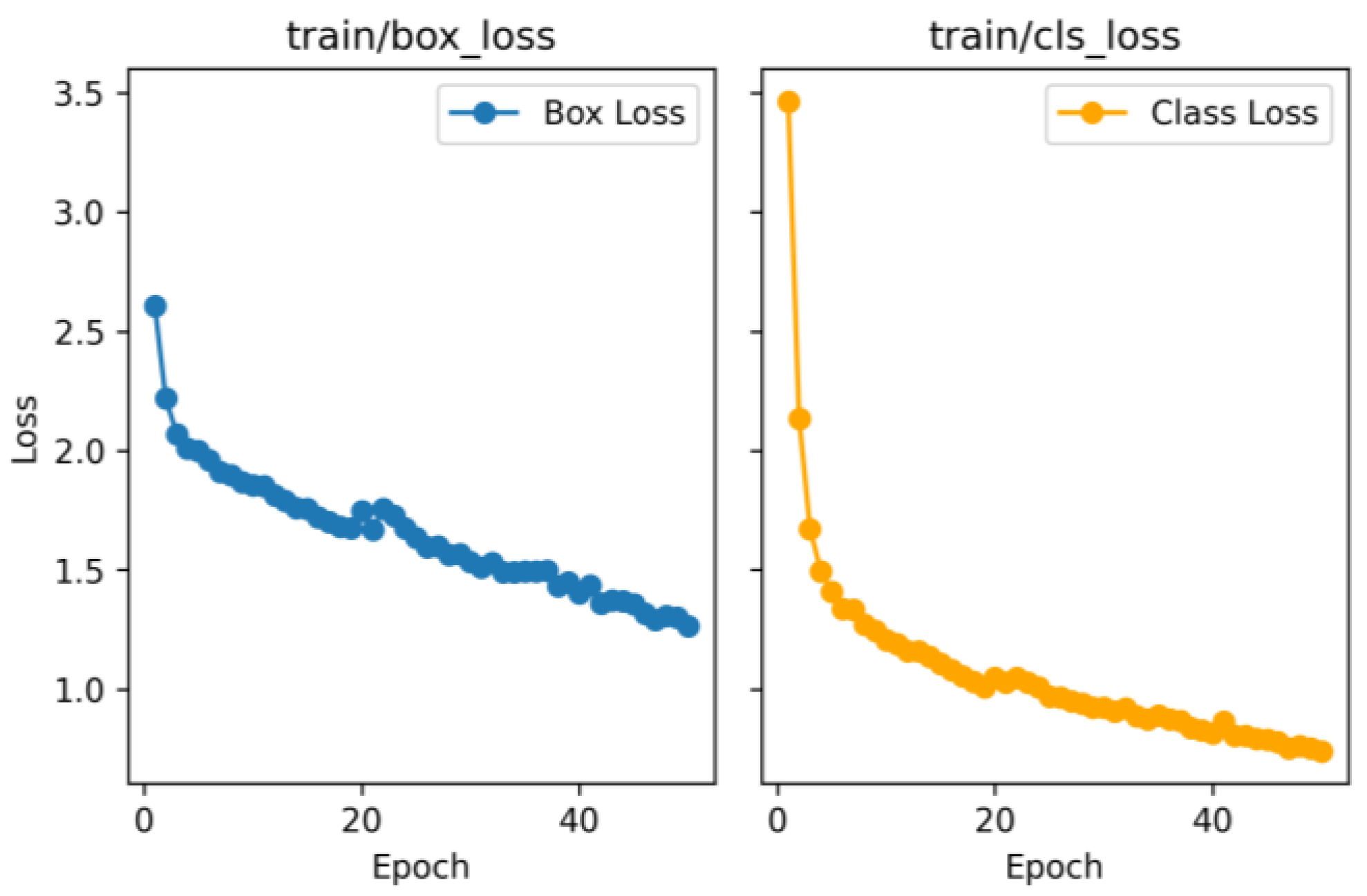

For all models we used standard configuration and trained then for two classes (person and luggage), with a composite loss and the

SiLU activation function, a batch size of 16, and a

momentum of 0.937. Each model was trained for up to 50 epochs or until the loss ceased to decrease (

Figure 6.).

-

A.

Evaluation metrics

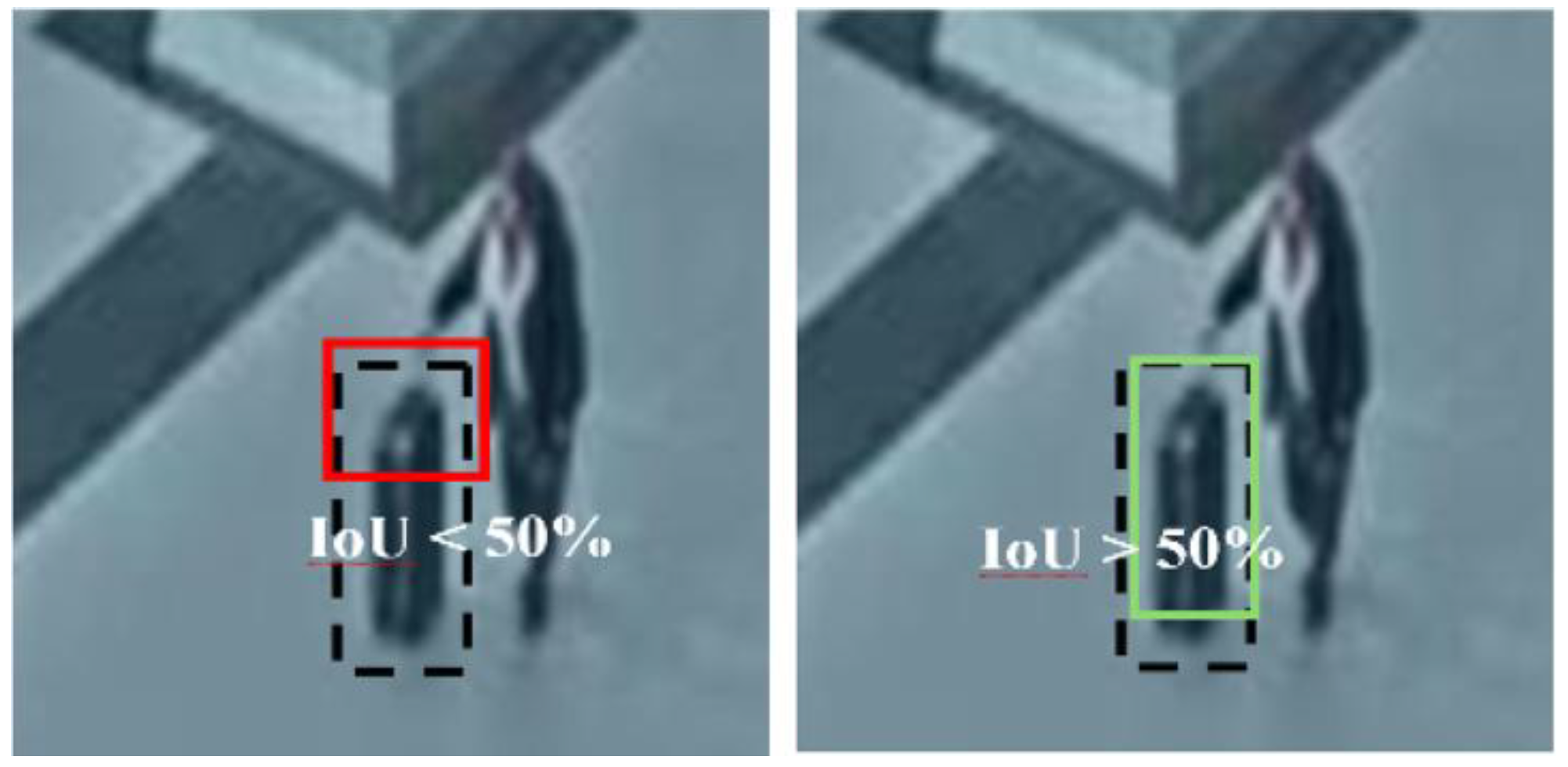

Quantitative evaluation of the model’s performance was carried out using standard metrics with a

minimum confidence threshold of 50%, namely precision, recall, and mean Average Precision (mAP) [

13].Precision and recall evaluate the quality of the model: precision is the ratio of correct predictions to the total number of predictions, measuring the model’s ability to identify only relevant cases; recall is the ratio of true positives to all possible positives in the dataset, measuring the model’s ability to find all relevant instances.

Additional metrics specific to object detection include mAP@0.5 [

13]. The mAP@0.5 metric measures detection accuracy at a 50% overlap threshold between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth box (Intersection over Union, IoU). For detecting abandoned luggage in our scenario, pinpoint bounding-box accuracy is not strictly necessary, making the

50% IoU (

Figure 7.) accuracy threshold the most relevant.

-

B.

Quantitative results and discussion

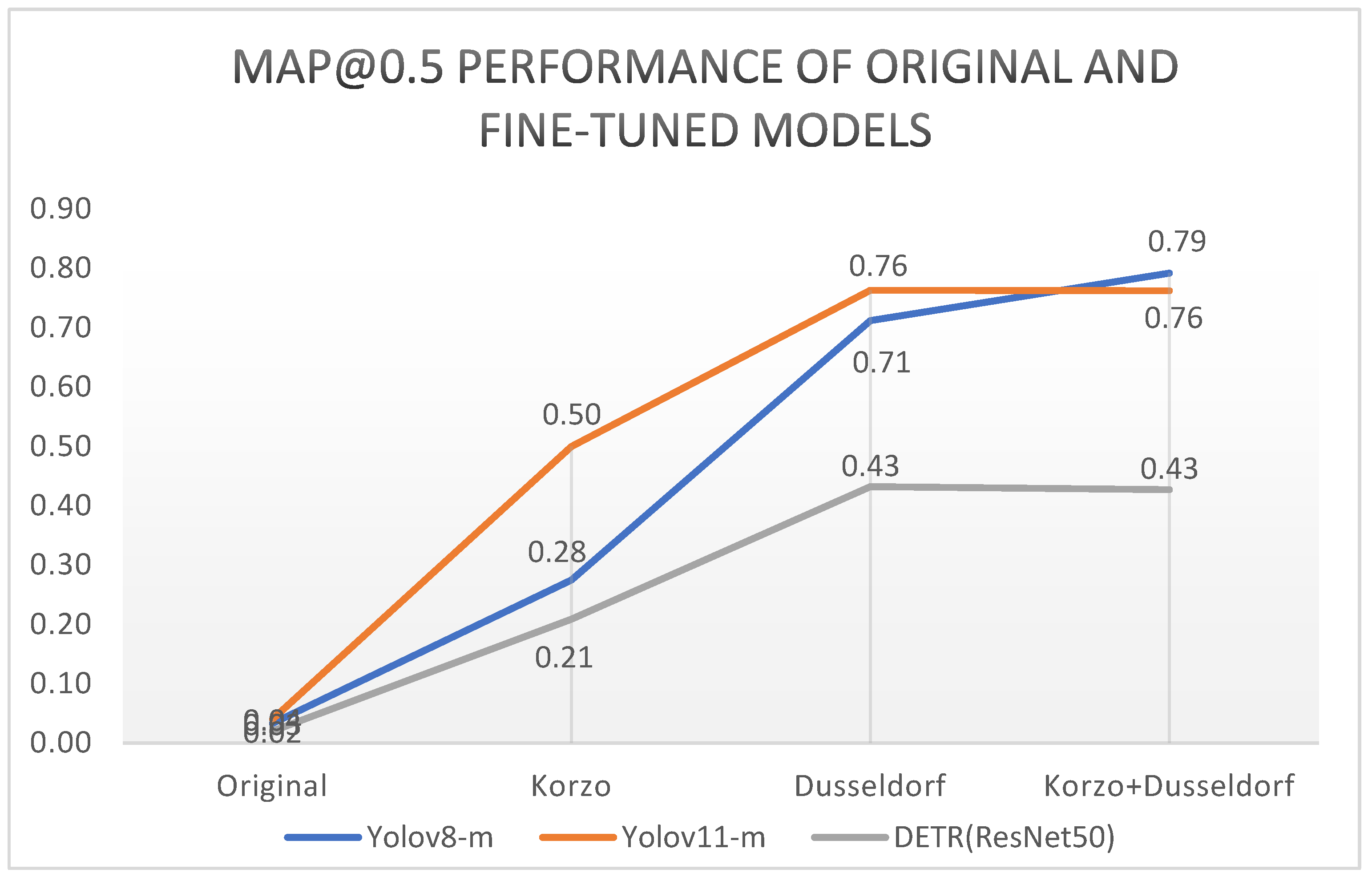

The model results with respect to mAP@0.5 precision are shown in

Figure 8. The graphs show that the original results for all models improved significantly after fine-tuning on the adjusted datasets. For instance, YOLOv8m model trained on CCTV-Korzo+Dusslerdoff achieves an

mAP@0.5 of 79.18%, whereas the baseline model manages only

3.34%. Both YOLO models achieve the best results on the combined Korzo + Düsseldorf set, even 5% better than on the Düsseldorf set, while the DEIT model achieves equal cuts on both sets. It is interesting to note that the Korzo + Düsseldorf set is an extension of the Düsseldorf set, with the images of surveillance cameras on the Korzo city promenade, which shows that the inclusion of images taken from a similar perspective from another domain had a positive effect on improving the performance of the models. Interestingly, both YOLO models fine-tuned on the Korzo + Düsseldorf set achieve significantly, even 30% better results than the fine-tuned DETR model. The significantly worse results of the DETR transformer than the YOLO models are probably due to small objects in the images that the model failed to detect, since previous studies have shown that transformers often struggle with detecting small objects due to their global attention mechanism, as they can dilute fine-grained details [

12].

Models YOLOv8 and YOLOv11 fine-tuned on the Korzo + Düsseldorf set (labeled as YOLOv8(KD) and YOLOv11(KD)) achieve very good detection results, so on the same set we fine-tuned all versions of the model to be able to choose the one that gives the best performance in real time.

Table 3 compares the performance of YOLOv8(KD) and YOLOv11(KD) model variants across different sizes (nano, small, medium, and large) using three key metrics: Precision, Recall, and mAP@50. The results were achieved on the validation set during model training and show the performance achieved in the best epoch of model learning.

All versions of both models achieve very good results ranging from 0.69 to 0.77 for mAP precision, i.e., precision from 71% achieved by the smallest version of the YOLOv8(KD) model to 79% achieved by the YOLOv8(KD)-m version. Recall ranges from 68% for the YOLOv8(KD)-n model to the highest of 81% achieved by the YOLOv11(KD)-l model. The performance between the model variants in the YOLOv8(KD) and YOLOv11(KD) families is mostly similar or with a small difference of around +/- 2%. A more noticeable difference between the performance between the YOLOv8(KD) and YOLOv11(KD) family model versions of 7% and 4%, respectively, can be observed only in the larger model versions.

Overall, the difference in performance between YOLOv8(KD) and YOLOv11(KD) is relatively small. YOLOv11(KD) appears to have a slight advantage in recall, especially in the larger variants, YOLOv11(KD)-m and YOLOv11(KD)-l, while YOLOv8(KD) has better precision in these model variants. The choice between the two will depend on the specific requirements of the application, and in our case of child-left luggage, it is more critical that the model achieves higher recall in order to detect as many potentially suspicious objects as possible to and to provide our abandoned luggage detection algorithm with the highest quality input data.

-

C.

Quantitative results related to Object Size and discussion

Given the similar properties and performance of the YOLOv8(KD) and YOLOv11(KD) m i l models, we tested their performance with respect to the size of the objects on the Düsseldorf testing dataset. Since in our case we are dealing with surveillance camera footage, we mainly have medium-sized objects and a large number of small objects in the scenes, so the important information for model selection, in addition to real-time performance, is how the model performs in detecting medium-sized and small objects. For this purpose, we tested large variants of fine-tuned models of the YOLOv8 and v11 family with regard to the COCO detection evaluation metric.

The CCTV-Korzo+Düsseldorf dataset included no large objects, resulting in an AP_large score of -1.0, primarily due to security camera setups covering wide areas, causing objects to appear smaller and further away. In total, the dataset contained 8450 labeled objects, of which 5111 small objects and 3379 medium objects, aligning with the absence of large objects.

Per the COCO standard, object sizes are categorized as follows:

Small objects: Area < 322 pixels.

Medium objects: 322 ≤ Area < 962 pixels.

Large objects: Area ≥ 962 pixels.

Examples of small objects in our CCTV-Korzo+Düsseldorf dataset are compact bags, backpacks, or people who are further away from the surveillance camera as shown in

Figure 9, and medium-sized objects are shown in

Figure 10. Detection of small objects is challenging for models due to insufficient spatial and semantic information at deeper network feature layers, which are crucial for accurate detection.

Performance of the fine-tuned YOLOv8(KD) and YOLOv11(KD) models in their medium (m) and large (l) versions, with a particular focus on their ability to detect small and medium-sized objects is shown in

Table 4.

Obtained results show that YOLOv11(KD) outperforms YOLOv8(KD) in the medium and large versions. Specifically, YOLOv11(KD)-l has the highest mAP@0.5 of 71%, followed by YOLOv11(KD)-m with 70%, while YOLOv8(KD)-l and YOLOv8(KD)-m have 3% lower values. Also, the YOLOv11(KD) models show superior performance in detecting small objects with the highest AP_small of 69% of YOLOv11(KD)-l, followed by YOLOv11(KD)-m with 67%, while the YOLOv8(KD) models lag behind by 4%. All models perform well in detecting medium-sized objects, but both versions of YOLOv11(KD) at 94% still slightly outperform the other AP_medium results. YOLOv8(KD)-m has the second-best performance of 92.5%. A negative AP_large metric for all models indicates that there were no large objects in the dataset. Overall, YOLOv11(KD) and YOLOv8(KD) models show good performance but YOLOv11(KD)-l still has superior performance in small object detection which makes it potentially more suitable for surveillance applications where small object detection is crucial.

-

D.

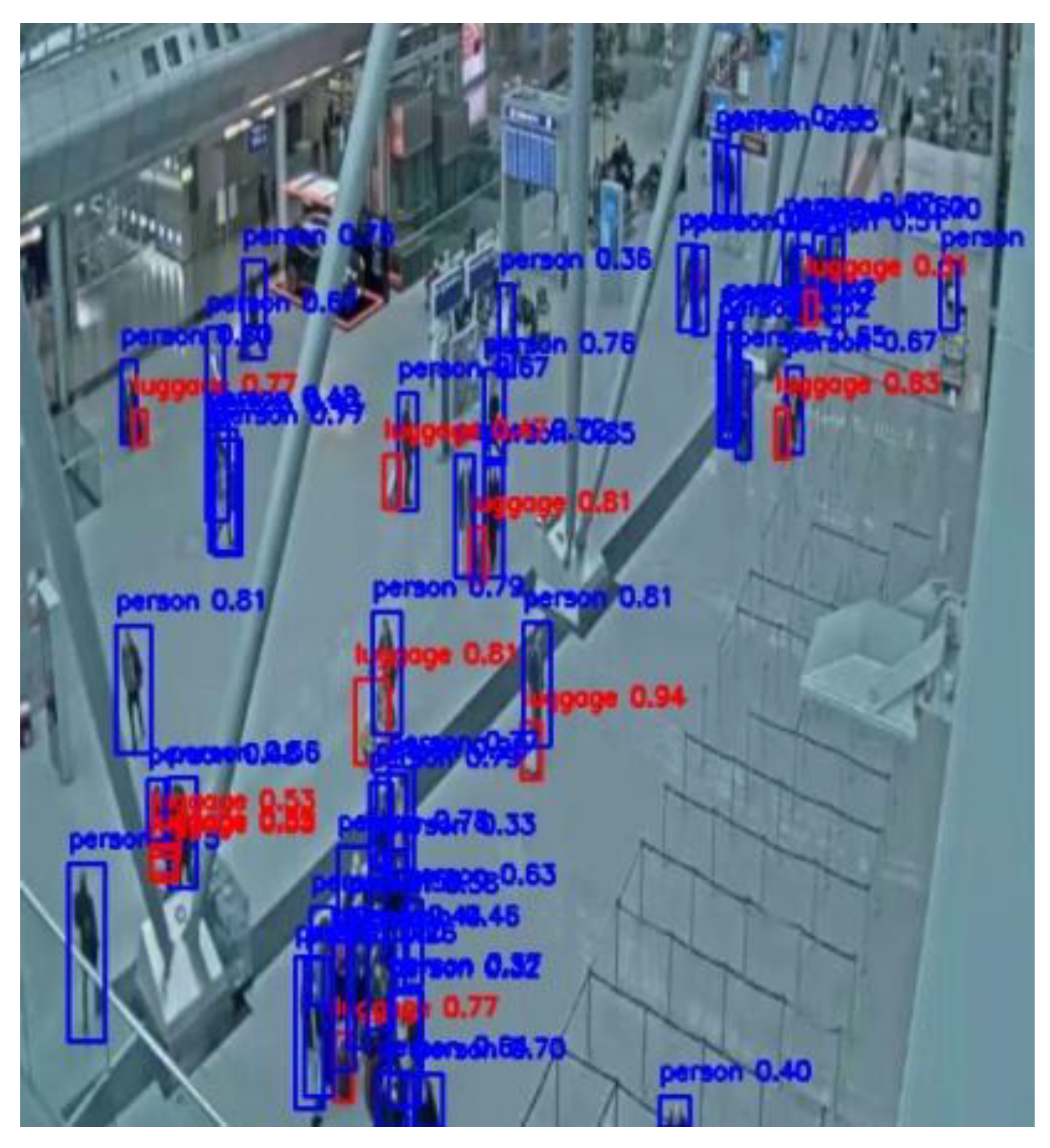

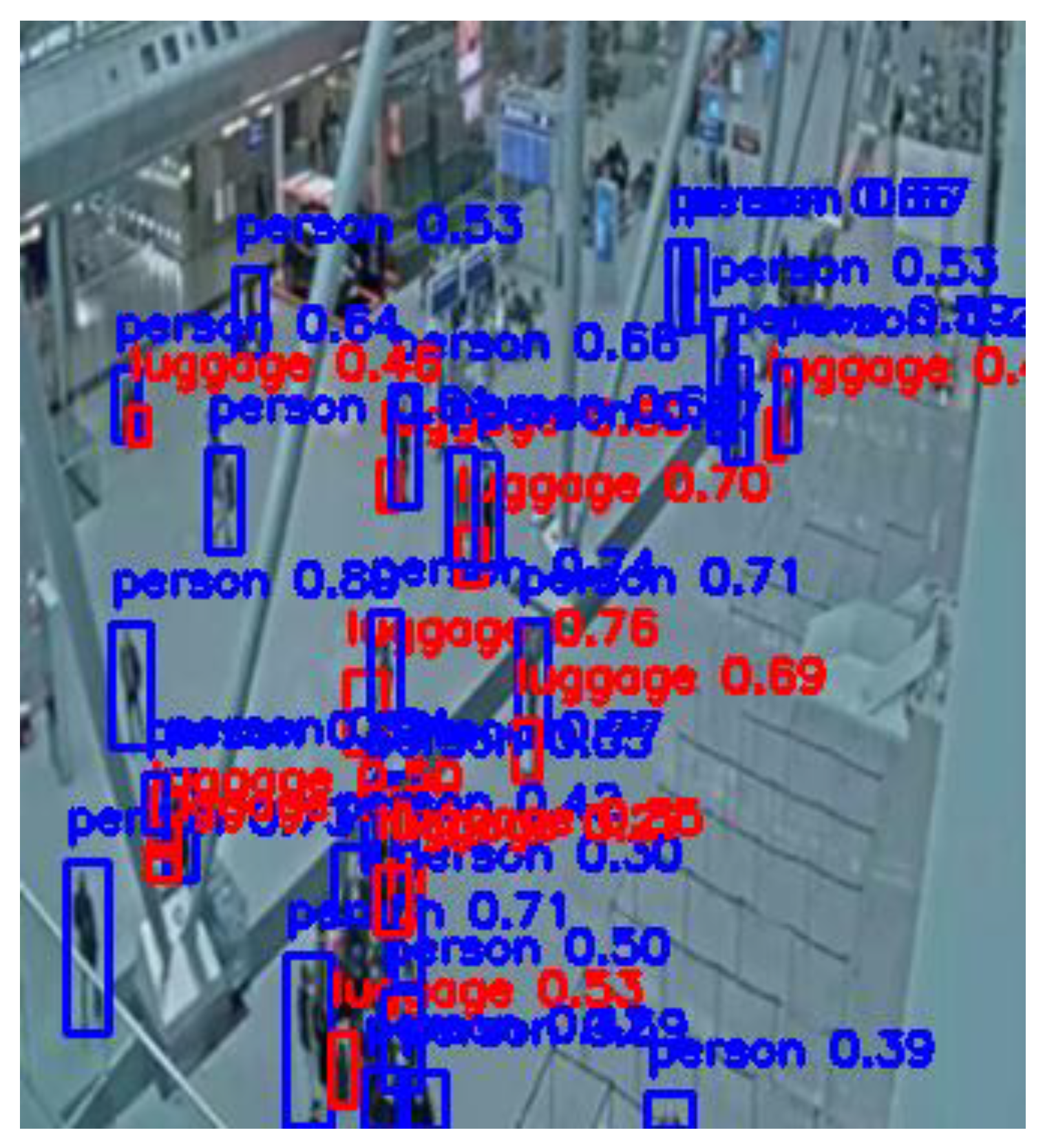

Qualitative Comparison

Below are examples of detections of the basic YOLOv8 and YOLOv11 models and their fine-tuned versions. Baseline models of both versions fail to detect either people or luggage (

Figure 11,

Figure 13), clearly highlighting its limitations in real-world surveillance scenarios. In contrast, after the models have been fine-tuned on the CCTV-Korzo+Dusslerdoff set, they successfully detect both people and luggage (

Figure 12,

Figure 14). This difference highlights the importance of fine-tuning the model for specific application domains, especially for the task of person and baggage detection in order to effectively assist surveillance operators in protecting areas and enabling timely intervention against potential security risks.

8. Different Scenarios for Testing Abandoned Luggage Detection System

Detecting abandoned luggage in a real-world environment involves addressing different scenarios that reflect different human behaviors and interactions in public spaces. In the following, we elaborate and analyze the potential scenarios that we consider in this research to test the proposed system based on our fine-tuned YOLOv11(KD)-l model for detecting and tracking people and luggage. Each scenario presents specific challenges, so the parameters need to be adaptable, and the abandoned luggage detection algorithm must be robust.

-

A.

Single Person Abandoning Luggage

The simplest scenario involves a single person entering the monitored area with one or more pieces of luggage and subsequently leaving the area, leaving the luggage unattended. The system must accurately associate the person with their luggage, track their movements, and confirm that the individual has exited the predefined radius while the luggage remains stationary for a specified duration (

Figure 15). Our system works without any problems in this test scenario.

-

B.

Group of People with Luggage

In this scenario, a group enters the monitored area, potentially with multiple pieces of luggage. Some members of the group may leave the area while others remain, maintaining supervision over the luggage. Importantly, the system must distinguish between separate individuals or groups simply passing by each other and cohesive groups, such as families who share luggage. Misidentifying these relationships can lead to false abandonment alarms. To address this, the system employs ID-based tracking to associate each piece of luggage with the correct individual(s), allowing for accurate mapping of luggage ownership within dynamic group interactions. After initial detection and tracking, an algorithm continuously evaluates positional relationships and assigned IDs to update group memberships and maintain consistent ownership links.

Our system is designed for these situations and does not raise false alarms when ownership is transferred from an individual to a cohesive group.

-

C.

Restroom break

A common real-world scenario occurs when multiple individuals share a single piece of luggage, but take turns leaving the immediate area, such as using the restroom. For example, two travelers arrive with a single suitcase and Person #1 briefly goes to the restroom while Person #2 stays with the luggage and then switches, Person #2 goes to the restroom while Person #1 guards the luggage. The system detects the event that the original “owner” has left the safe baggage detection radius, but if another member of the group was within the set radius, the baggage is never marked as unattended.

This scenario highlights the importance of robust modeling of group ownership and flexibly associating baggage with owners. Our system allows for the transfer of ownership from Person #1 to Person #2 (and vice versa), thereby preventing false alarms resulting from consecutive, short-term abandonments of the baggage. Our solution involves the introduction of a proximity-based timer, whereby an individual who remains near a piece of baggage for a sufficient period is dynamically remapped as its active owner. Additionally, each time the baggage begins to move—such as being lifted or rolled—the system can transfer ownership to the person physically handling it, thereby reducing false alarms associated with short, consecutive departures.

-

D.

Shaking and Video Disruptions

Shaking and video disruptions, often caused by unstable camera setups or environmental factors (e.g., intense vibrations during airplane takeoff), create blurred frames, motion distortions, and inconsistencies in object trajectories, reducing the reliability of standard detection and association algorithms. To counteract these effects, our system applies an averaging mechanism over a variable number of recent frames (determined by camera specifications and environmental conditions), combined with tailored movement thresholds, ensuring transient vibrations and brief motion anomalies are sufficiently smoothed out to prevent false detections or missed associations.

-

E.

Crowded Environments

Crowded settings, such as airport terminals or public plazas, introduce significant challenges for abandoned luggage detection. Large numbers of people and objects move through the scene, frequently overlapping and covering each other. This results in luggage sometimes being partially or completely hidden from the camera’s view, complicating continuous tracking and luggage association with the owner. In addition, multiple similar-looking items may be present, creating ambiguity when trying to maintain the identity of each piece of luggage (

Figure 16.).

Detecting abandoned luggage in densely populated areas is inherently challenging and often impractical, as occlusions and constant motion make it nearly impossible to reliably identify stationary objects.

Therefore, the crowded scenarios are usually not specific to the tasks of detecting abandoned luggage, although they are crucial for increasing public safety in large traffic hubs, so we analyzed them as well. Also, today’s detectors, including our system, have problems detecting people and luggage in these cases, especially problems with changing the identity of the luggage owner due to temporary obscuration from the camera and occlusions, which also affects the problem of determining the belongings of the luggage.

To address these challenges, our system uses adaptive parameters such as luggage ownership radius, movement threshold, and inactivity duration, however, small objects and the problem of interruptions in person and luggage tracking due to occlusion and overlap are obstacles that cannot currently be successfully overcome.

9. Discussion

The assumptions and adjustable parameters incorporated into our algorithm demonstrated sufficient flexibility to enable the detection of abandoned luggage across diverse real-world scenarios. Despite these strengths, the system exhibits notable limitations in densely crowded environments, primarily due to the constraints of the object detector. Challenges arise when detecting small objects positioned far from the camera, as well as in instances of object overlapping, occlusion, or high crowd density. These limitations are not unique to our system; even human annotators frequently encounter difficulties in such conditions, occasionally overlooking partially occluded objects and thereby producing incomplete ground truth annotations. This can result in scenarios where correctly detected objects are misclassified as false positives due to incomplete labeling.

Earlier research, [

1,

2,

4] demonstrated higher detection accuracy, but this success can be attributed to the simpler conditions under which their systems were evaluated. These studies predominantly focused on detecting single, isolated abandoned objects in controlled or less dynamic environments, where the absence of complex crowd interactions and occlusions facilitated better performance. Although our system has not yet reached the detection accuracy observed in such controlled conditions, it leverages advancements in modern object detection frameworks to address more challenging, real-world environments in real time.

Further improvements are necessary to enhance the system’s performance in crowded settings. Potential solutions include the integration of multi-camera surveillance systems to provide broader scene coverage, the development of advanced occlusion-handling algorithms, and the implementation of robust re-identification techniques to track luggage owners even amidst dense pedestrian traffic and frequent occlusions. Addressing these challenges is crucial for advancing abandoned luggage detection systems and ensuring reliable performance in dynamic, real-world scenarios.

10. Conclusions

This paper presented a prototype system for abandoned luggage detection that can shorten the response time of surveillance teams to suspicious situations, thereby reducing the need for manual monitoring and contributing to a higher level of safety in public spaces. The research aimed to develop a model that automatically recognizes abandoned luggage in surveillance footage is, detects situations where luggage has been left unattended and alerts the appropriate services.

For this purpose, data was collected from surveillance cameras in public places such as the city promenade and the airport to form a sets of surveillance scenes for training and testing the model. The deep convolutional models YOLOv8, YOLOv11 and transformer DETR(ResNet-50) mode were selected for detection, since have achieved good detection results on the COCO data set and were subsequently fine-tuned on our custom set. All original models had extremely low initial results, however, they showed significant improvement after fine-tuning, e.g., the YOLOv8-m model from only 3% mAP@0.5 rose to 79%, and the YOLOv11-m model behaved similarly. The DETR model failed to adjust to the same extent on our custom set and was significantly slower so we dropped it as a solution.

Additionally, considering that surveillance scenes abound with objects that are small or medium in size according to the COCO evaluation metric, we additionally fine-tuned all the variants of those YOLOv8 and YOLOv11 model families. It was shown that their fine-tuned larger variants, m and l, show excellent performance in detecting medium objects with a mAP accuracy of 94%, while the YOLOv11-l model is still the best in detecting small objects and reaches 69%.

The experiment showed that by adapting the model to the dataset, it provides significantly better results that are crucial for further analysis and use in the proposed algorithm for automatic detection of abandoned luggage. Our algorithm is defined so that it classifies detected luggage as abandoned if it is stationary more than a defined threshold and if it is out of reach of all owners within a defined radius. Different scenarios of abandoned luggage in different environments were analyzed, including city streets, promenades and airports, and the model was tested on footage of different scenarios in order to more accurately assess its performance and limitations in different security contexts.

The study confirmed that the fine-tuned YOLOv11-l model can be effectively adapted to a specific dataset and successfully employed for detecting abandoned objects in real-world conditions. Future work will focus on analyzing various scenarios of luggage abandonment and optimizing the algorithm parameters, particularly regarding different recording conditions, to further tailor the system to high-risk situations.

References

- [1] S. M. J. O. D. M. J. Luna E, “Abandoned Object Detection in Video-Surveillance: Survey and Comparison,” Intelligent Sensors, pp. 18(12), 4290, 2018.

- [2] K. &. Q. P. &. G.-P. D. Smith, “Detecting Abandoned Luggage Items in a Public Space,” IEEE Performance Evaluation of Tracking and Surveillance Workshop (PETS), 2006.

- [3] S. S. a. R. T. Ionescu, “Real-Time Deep Learning Method for Abandoned Luggage Detection in Video,” in 6th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Rome, Italy, 2018.

- [4] T. &. S. P. &. S. K. &. C. W. Santad, “Application of YOLO Deep Learning Model for Real Time Abandoned Baggage Detection,” in IEEE 7th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics, Nara, Japan, 2018.

- [5] J. L. H. &. C. L. Chang, “Localized Detection of Abandoned Luggage,” EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing, 2010.

- [6] X. Z. S. R. a. J. S. K. He, “Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks,” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence , vol. VOL. 39, no. NO. 6, 2017.

- [7] Ultralytics, “Ultralytics Documentation,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://docs.ultralytics.com/. [Accessed Jan 2025].

- [8] S. D. R. G. A. F. Joseph Redmon, “You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1506.02640, 2016.

- [9] G. J. e. al., “ YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 implementation documentation,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. [Accessed 11 2024].

- [10] S. J. P. a. Q. Yang, “A Survey on Transfer Learning,” IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, pp. 1345-1359, 2010.

- [11] P. S. Y. J. D. Y. F. W. Z. Y. P. L. W. L. X. W. Yifu Zhang, “Bytetrack: Multi-object tracking by associating every detection box,” in European Conference on Computer Vision , Cham, Switzerland, 2021.

- [12] N. M. F. S. G. U. N. K. A. &. Z. S. Carion, “End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers.,” in European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, United Kingdom, 2020.

- [13] S. L. N. a. E. A. B. d. S. R. Padilla, “A Survey on Performance Metrics for Object-Detection Algorithms,” in International Conference on Systems, Signals and Image Processing (IWSSIP), Niteroi, Brazil, 2020.

- [14] L. Q. H. Q. J. S. a. J. J. S. Liu, “A survey and performance evaluation of deep learning methods for small object detection,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 172, no. 114602, 2021.

- [15] N. A. A. A. a. B. A. A. -R. A.-G. A. M. Qasim, “Abandoned Object Detection and Classification Using Deep Embedded Vision,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 35539-35551, 2024.

- [16] R. Khanam, M. Hussain: YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements, 2024, arXiv:2410.17725, [Accessed 01.2025].

- [17] G. Jocher and A. Chaurasia and J. Qiu, Ultralytics YOLOv8, 2023. https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolov8/#yolov8-usage-examples [Accessed 01.2025].

- [18] S. Sambolek and M. Ivasic-Kos, “Automatic Person Detection in Search and Rescue Operations Using Deep CNN Detectors,” in IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 37905-37922, 2021. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Group detection.

Figure 1.

Group detection.

Figure 2.

System for abandoned luggage detection.

Figure 2.

System for abandoned luggage detection.

Figure 3.

Person inside safe radius.

Figure 3.

Person inside safe radius.

Figure 4.

Labeled image from CCTV—Korzo dataset.

Figure 4.

Labeled image from CCTV—Korzo dataset.

Figure 5.

Labeled image from CCTV- Düsseldorf dataset.

Figure 5.

Labeled image from CCTV- Düsseldorf dataset.

Figure 6.

Box loss and class loss during model training.

Figure 6.

Box loss and class loss during model training.

Figure 7.

Intersection over Union.

Figure 7.

Intersection over Union.

Figure 8.

Performance comparison of original models and models fine-tuned on different sets K, D, KD in terms of mAP@0.5 on Düsseldorf test dataset.

Figure 8.

Performance comparison of original models and models fine-tuned on different sets K, D, KD in terms of mAP@0.5 on Düsseldorf test dataset.

Figure 9.

Small size object detected with Yolov8(KD)-m;.

Figure 9.

Small size object detected with Yolov8(KD)-m;.

Figure 10.

Medium size object detected with Yolov8(KD)-m.

Figure 10.

Medium size object detected with Yolov8(KD)-m.

Figure 11.

YOLOv8-m baseline model.

Figure 11.

YOLOv8-m baseline model.

Figure 12.

YOLOv8(KD)-m fine-tuned model.

Figure 12.

YOLOv8(KD)-m fine-tuned model.

Figure 13.

YOLOv11-m baseline model.

Figure 13.

YOLOv11-m baseline model.

Figure 14.

YOLOv11(KD)-m fine-tuned model.

Figure 14.

YOLOv11(KD)-m fine-tuned model.

Figure 15.

Single person abandoned luggage.

Figure 15.

Single person abandoned luggage.

Table 1.

Comparison of Different Approaches for Abandoned Luggage Detection.

Table 1.

Comparison of Different Approaches for Abandoned Luggage Detection.

| Approach |

Ref. |

Main Features |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| Background Subtraction Methods (traditional) |

[1,3,4] |

- Static/moving parts of the image - Foreground segmentation |

- Simple to implement - Low computational requirements |

- Sensitive to crowded scenes - Low accuracy |

| MCMC and SVM |

[2,3] |

- Bayesian networks - Classification (SVM) |

- Tracks short displacements well |

- Sensitive to variations |

| Hybrid Approaches (CNN + Background Subtraction) |

[1,5,15] |

- Combination of background subtraction and CNN |

- Improved accuracy -Fewer false positives |

- Limited to sudden changes |

| YOLO |

[4,7,8,9,10] |

- Single-pass detection -Transfer learning |

- High accuracy even in crowded scenes -Easily adaptable |

- GPU-intensive during training |

Table 2.

Comparison of YOLOv8, YOLOv11 and DETR(ResNet50) original models.

Table 2.

Comparison of YOLOv8, YOLOv11 and DETR(ResNet50) original models.

| Model |

YOLOv8 |

YOLOv11 |

| Version |

Number of parameters (M) |

Model size (MB) |

Inference time (ms) * |

mAPval

(0.50:0.95)

|

Number of parameters (M) |

Model size (MB) |

Inference time (ms) * |

mAPval

(0.50:0.95)

|

| Nano—n |

3.2 |

8.9 |

11.04 |

37.3 |

2.6 |

9.9 |

10.90 |

39.5 |

| Small—s |

11.0 |

30.6 |

9.86 |

44.9 |

9.4 |

35.8 |

10.85 |

47 |

| Medium—m |

25.0 |

68.9 |

16.71 |

50.2 |

20.1 |

76.7 |

16.75 |

51.5 |

| Large—l |

40.0 |

113.3 |

23.98 |

52.9 |

25.3 |

96.5 |

20.39 |

53.4 |

| XL—x |

68.0 |

189.0 |

36.48 |

53.9 |

56.9 |

217.1 |

36.30 |

54.7 |

| |

DETR |

|

| ResNet-50 |

41.0 |

156.4 |

93.6 |

45.9 |

|

Table 3.

Compartive results between YOLOv8(KD) and YOLOv11(KD) family models.

Table 3.

Compartive results between YOLOv8(KD) and YOLOv11(KD) family models.

| Metric |

YOLOv8(KD) |

YOLOv11(KD) |

Difference |

| |

NANO version |

| Precision |

0,71 |

0,73 |

0,03 |

| Recall |

0,68 |

0,70 |

0,02 |

| mAP@50 |

0,69 |

0,71 |

0,02 |

| |

Small version |

| Precision |

0,75 |

0,75 |

0,00 |

| Recall |

0,76 |

0,73 |

-0,03 |

| mAP@50 |

0,76 |

0,75 |

-0,01 |

| |

Medium version |

| Precision |

0,79 |

0,72 |

-0,07 |

| Recall |

0,76 |

0,80 |

0,04 |

| mAP@50 |

0,77 |

0,76 |

-0,01 |

| |

Large version |

| Precision |

0,76 |

0,73 |

-0,02 |

| Recall |

0,77 |

0,81 |

0,04 |

| mAP@50 |

0,76 |

0,76 |

0,00 |

| |

Best Results |

| Precision |

0,79 |

0,75 |

-0,05 |

| Recall |

0,77 |

0,81 |

0,04 |

| mAP@50 |

0,77 |

0,76 |

-0,01 |

Table 4.

COCO detection evaluation metric related to object size for fine-tuned models YOLOv8(KD)-m, YOLOv8(KD)-l,YOLOv11(KD)-m YOLOv11(KD)-l tested on Düsseldorf test set.

Table 4.

COCO detection evaluation metric related to object size for fine-tuned models YOLOv8(KD)-m, YOLOv8(KD)-l,YOLOv11(KD)-m YOLOv11(KD)-l tested on Düsseldorf test set.

| Model |

YOLOv8(KD)-m |

YOLOv8(KD)-l |

YOLOv11(KD)-m |

YOLOv11(KD)-l |

| Metric |

Value |

Value |

Value |

Value |

| mAP@0.5 |

0.6766 |

0.6787 |

0.7004 |

0.7153 |

| AP_small |

0.6397 |

0.6450 |

0.6673 |

0.6904 |

| AP_medium |

0.9240 |

0.8831 |

0.9390 |

0.9376 |

| AP_large |

-1,000 |

-10,000 |

-10,000 |

-10,000 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).