1. Introduction

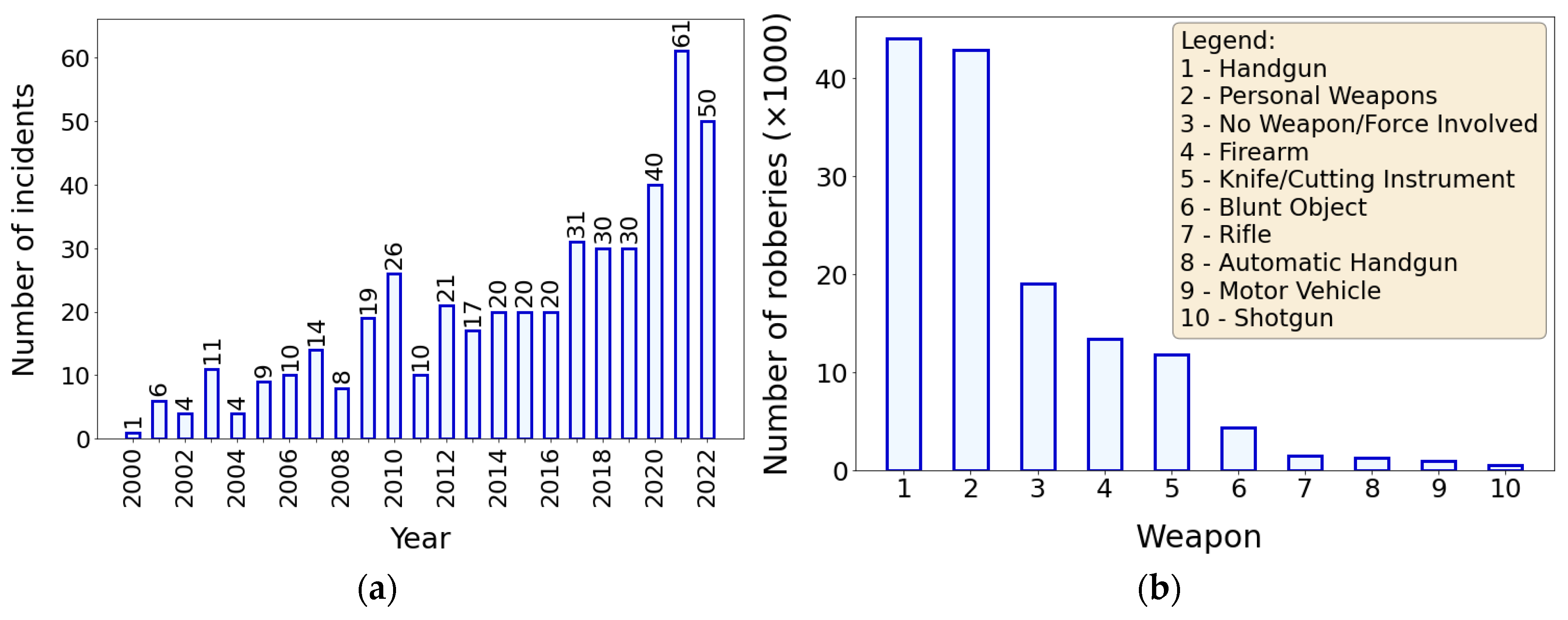

In recent years, the problem of a growing number of incidents of violation of public security has become apparent. This is very well expressed by a statistic posted on the Statista website, showing the number of incidents involving active shooters in the United States between 2000 and 2022 (

Figure 1a). It should be noted that such incidents have also occurred with other types of items (e.g., knives, machetes, baseball bats). Considering the type of weapon used in the aforementioned acts of violence, various types of firearms (guns, rifles, shotguns) dominate here, but knives and various types of cutting tools (e.g., machetes) are also present.

Figure 1b shows the number robberies in the United States in 2022, by weapon used.

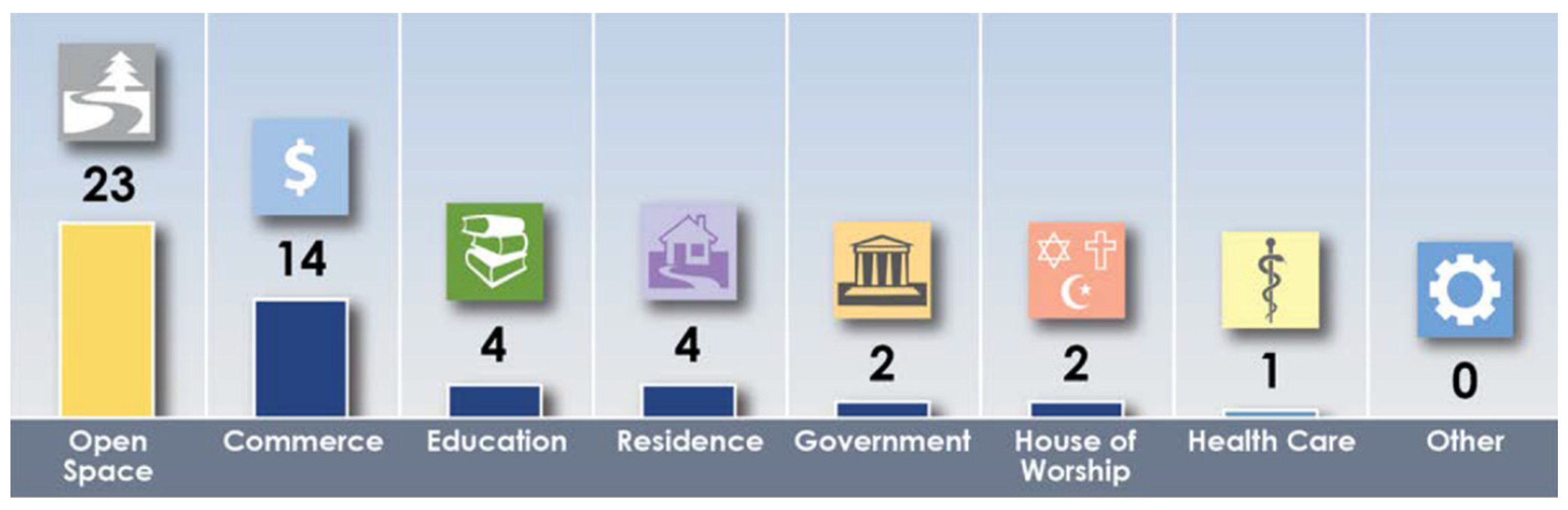

In a report titled

A Study of Active Shooter Incidents in the United States Between 2000 and 2013, the FBI identified 7 locations where the public is most vulnerable to security incidents [

1]. These locations include: open space, commercial areas, educational environments, residences, government properties, houses of worship, health care facilities.

Figure 2 shows the number of active shooter incidents that occurred at the mentioned locations in the United States in 2022. The summary in

Figure 2 does not include incidents involving other types of weapons, which also occurred. A potential opportunity to prevent acts of violence is provided by intelligent vision systems using surveillance cameras installed in public places. The images acquired by these cameras can be analysed for dangerous objects brought in by people. If such items are detected, the appropriate services (police, facility security, etc.) can be notified early enough. In this way, the chance can be increased to prevent a potential act of violence. Most public-use facilities (schools, train stations, stores, etc.) already use functioning monitoring systems, so the simplest and cheapest solution would be to integrate into these systems machine learning models trained to detect dangerous items in people. Great opportunities are offered here by deep convolutional neural networks, which are successfully used to detect various types of objects.

Among other applications, deep networks are used to automatically identify dangerous objects from X-ray images during airport security checks. Gao et al. proposed their own convolutional neural network model based on oversampling for detecting from an unbalanced dataset such objects as explosives, ammunition, guns and other weapons, sharp tools, pyrotechnics and others [

3]. In contrast, Andriyanov used a modified version of the YOLOv5 network to detect ammunition, grenades and firearms in passengers’ main baggage and carry-on luggage [

4]. In the proposed solution, the initial detection is carried out by the YOLO model, and the results obtained are subjected to final classification by the VGG-19 network. A number of models have also been developed for use in monitoring systems for public places. Gawade et al. used a convolutional neural network to build a system designed to detect knives, small arms and long weapons. The accuracy of the built model was 85% [

5]. The convolutional neural network ensemble was also applied by Haribharathi et al. [

6]. It has achieved better results than single neural networks during automatic weapon detection. In addition to convolutional neural networks, YOLO and Faster R-CNNs are often used. Kambhatla et al. conducted a study on automatic detection of pistol, knife, revolver and rifle using YOLOv5 and Faster R-CNN networks [

7]. In contrast, Jain et al. used SSD and Faster R-CNN networks for automatic gun detection [

8]. Some authors propose their own original algorithms. One example is the PELSF-DCNN algorithm for detecting guns, knives and grenades [

9]. According to the authors, the accuracy of their method is 97.5% and exceeds that of other algorithms. A novel system for automatic detection of handguns in video footage for surveillance and control purposes is also presented in [

10]. The best results there were obtained for a model based on Faster R-CNN trained on its own database. The authors report that in 27 out of 30 scenes, the model successfully activates the alarm after five consecutive positive signals with an interval of less than 0.2 seconds. In contrast, Jang et al. proposed autonomous detection of dangerous situations in CCTV scenes using a deep learning model with relational inference [

11]. The authors defined a baseball bat, a knife, a gun and a rifle as dangerous objects. The proposed method detects the objects and, based on relational inference, determines the degree of danger of the situations recorded by the cameras. Research on detecting dangerous objects is also being undertaken to protect critical infrastructure. Azarov et al. analysed existing real-time machine learning algorithms and selected the optimal algorithm for protecting people and critical infrastructure in large-scale hybrid warfare [

12].

One of the challenges in object detection is the detector’s ability to distinguish small objects during hand manipulation. Pérez-Hernández et al. proposed improving the accuracy and reliability of detecting such objects using a two-level technique [

13]. The first level selects proposals for regions of interest, and the second level uses One-Versus-All or One-Versus-One binary classification. The authors created their own dataset (gun, knife, smartphone, banknote, purse, payment card) and focused on detecting weapons that can be confused by the detector with other objects. Another problem is the detection of metal weapons in video footage. This is difficult because the reflection of light from the surface of such objects results in a blurring of their shapes in the image. As a result, it may be impossible to detect the objects. Castillo et al. developed an automatic model for detecting cold steel weapons in video images using convolutional neural networks [

14]. The robustness of this model to illumination conditions was enhanced using so-called brightness-controlled preprocessing (DaCoLT) involving dimming and changing the contrast of the images during the learning and testing stages. The authors of an interesting paper in the field of dangerous object detection are Yadav et al. [

15]. They made a systematic review of datasets and traditional and deep learning methods that are used for weapon detection. The authors highlighted the problem of identifying the specific type of firearm used in an attack (so-called intra-class detection). The paper also compares the strengths and weaknesses of existing algorithms using classical and deep machine learning methods used to detect different types of weapons.

Most of the available results in the area of object detection relate to datasets containing different categories of objects that are not strictly focused on the problem of detecting dangerous objects. In addition, the results presented are overestimated because a significant portion of the images in the collections used to build and test the models represent the objects themselves to be detected. They are not in the hand of any person, are large enough and perfectly visible. Consequently, the detector has little problem detecting such objects correctly and the reported detection precision is high. Such an approach misses the purpose of the research, which is to detect objects in the hands of people (potential attackers). Such objects are usually smaller, partially obscured and less visible, making them more challenging for the detector.

Against this background, our research stands out because it provides an insight into the construction of an object detector using a more specialised data set, which increases the trustworthiness and significance of the results obtained. We prepared the dataset in such a way that it contains items that are most often applied in acts of violence and violation of public safety, these are: baseball bat, gun, knife, machete and rifle. So, we can say that we have built and used a dataset dedicated to the task of detecting potentially dangerous objects. It is also important that objects are presented with different quality, namely: clearly visible, partially obscured, small (longer viewing distance), blurred (worse sharpness) and poorly lit. As a result, the dataset better reflects real-world conditions and the results obtained are more trustworthiness. The dataset we have prepared is publicly available to a wide range of researchers who are potentially interested in using it in own research. An additional contribution of our work is to show the possibility of using the popular Faster R-CNN architecture to detect dangerous objects by public place monitoring systems. The conducted experiments have shown that this kind of detector is characterized by low hardware requirements and high accuracy, which allows it to be recommended for the same or similar applications as those included in the subject of our research.

Section 2 briefly describes the Faster R-CNN used and characterises the object detection quality measures used and how the dataset was prepared.

Section 3 contains the results of the training and evaluation processes.

Section 4 evaluates the results obtained and compares them with the results of other authors. It also describes the effects of testing the best model using a webcam. The entire work ends with a summary and conclusions in

Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

The purpose of the research the results of which are presented in this paper was to build a model suitable for use in monitoring systems for public places. The objects monitored by such systems are usually people who move relatively slowly within the observed area. Therefore, the frequently used operating speed of such systems, amounting to several FPS, is quite sufficient. Taking this into account, the basic requirement for the model was high accuracy in detecting objects, especially small objects. The assumption made in the study was that the model would detect a specific set of potentially dangerous objects, such as baseball bat, gun, knife, machete, rifle. Comparing the size of these objects with the size of the monitored scene, there is no doubt that they are small objects, occupying a negligible portion of the image frame. Taking into account the requirements formulated earlier, the Faster R-CNN was chosen. This was due to the fact that, on the one hand, this type of network copes well with the detection of small objects, and on the other hand, it allows to achieve a processing speed of several dozen FPS, which is sufficient for use in monitoring systems.

2.1. Faster R-CNN

The genesis of the Faster R-CNN is related to the development of the R-CNN by R. Girshick et al. [

16]. This network offered higher accuracy compared to previous traditional object detection methods, but its main drawback was its low speed. For each image, the R-CNN generated approximately 2000 region proposals of various sizes, which were then subjected to feature extraction using a convolutional network [

17,

18,

19]. In 2015, R. Girshick proposed to improve the R-CNN and introduced a new network called Fast R-CNN [

20]. Instead of extracting features independently for each ROI, this type of network aggregated them in a single analysis of the entire image. In other words, the ROIs belonging to the same image shared computation and working memory. The Fast R-CNN detector proved to be more accurate and faster than previous solutions, but it still relied on the traditional method of generating 2000 region proposals (Selective Search method), which was a time-consuming process [

21].

The problem of the temporal efficiency of the Fast R-CNN was the reason for the development of a new detector called Faster R-CNN by S. Ren et al. [

22] It improved the detection speed of Fast R-CNN by replacing the previously used Selective Search method with a convolutional network known as a Region Proposal Network (RPN).

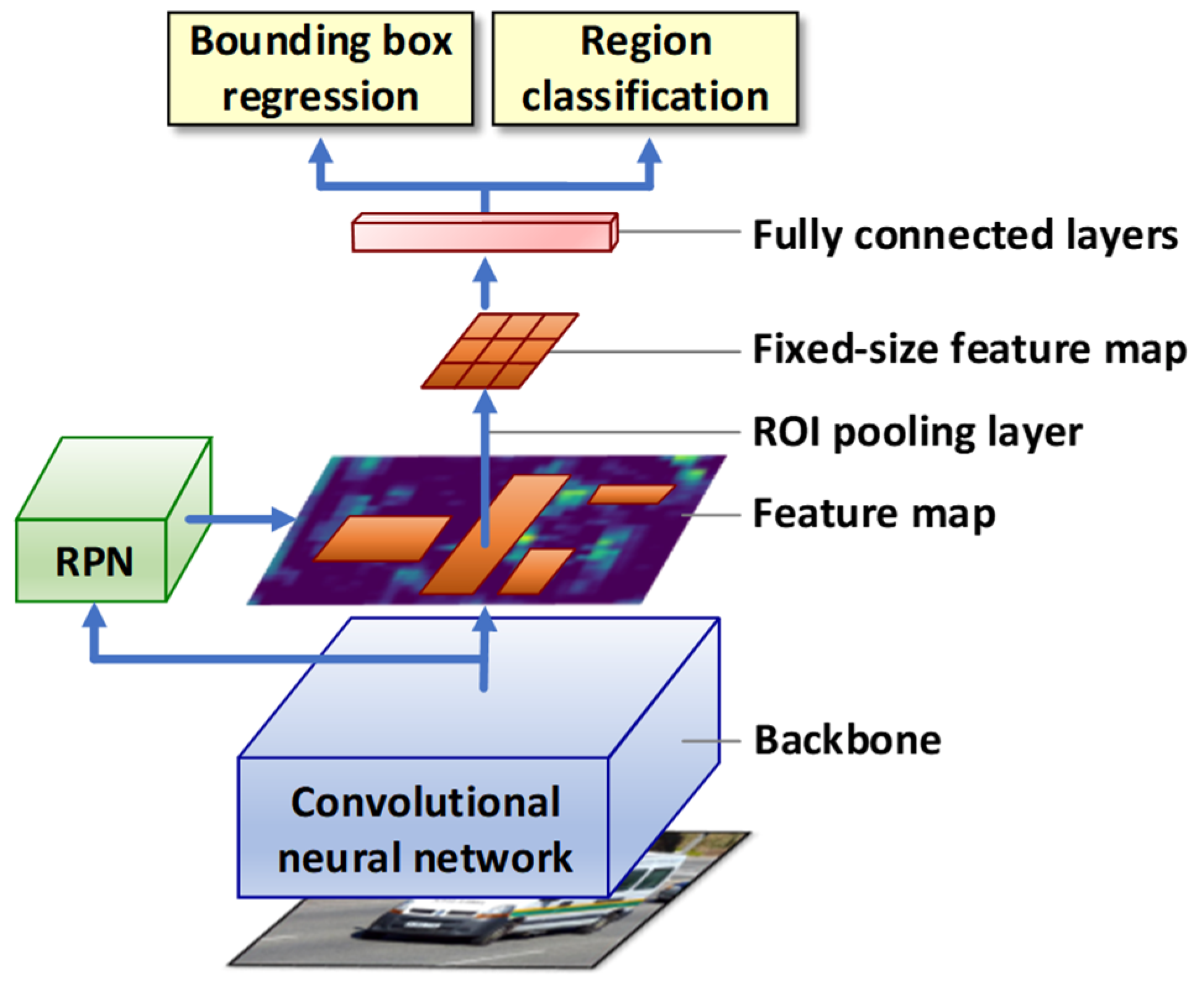

Figure 3 shows the architecture of the Faster R-CNN detector, and its operation can be described as follows:

A convolutional neural network takes an input image and generates a map of image features on its output.

The feature map is passed to the input of the RPN attached to the final convolutional backbone layer. The RPN acts as an attention mechanism for Fast R-CNNs. It tells you which region to look out for in relation to the potential presence of the object.

The feature map is then passed to the ROI pooling layer to generate a new map with a fixed size.

At the end of the process, the fully connected layers perform a region classification and a regression of the bounding box position.

Figure 3.

Faster R-CNN [

22].

Figure 3.

Faster R-CNN [

22].

The RPN takes input from a pre-trained convolutional network (e.g., VGG-16) and outputs multiple region proposals and predicted class labels for each of them. Region proposals are bounding boxes based on predefined shapes that are designed to speed up the region proposal operation. In addition, a binary prediction is used, indicating the presence of an object in a given region (the so-called objectness of the proposed region) or its absence. Both networks (RPN and backbone) are trained alternately, which allows you to tune parameters for both tasks at the same time. The introduction of the RPN has significantly reduced the number of regions proposed for further processing. This number was no longer equal to 2000, as in the case of Fast R-CNN, but was several hundred, depending on the complexity of the input images. This directly reduced training and prediction times and enabled the Faster R-CNN detector to be used in near real time.

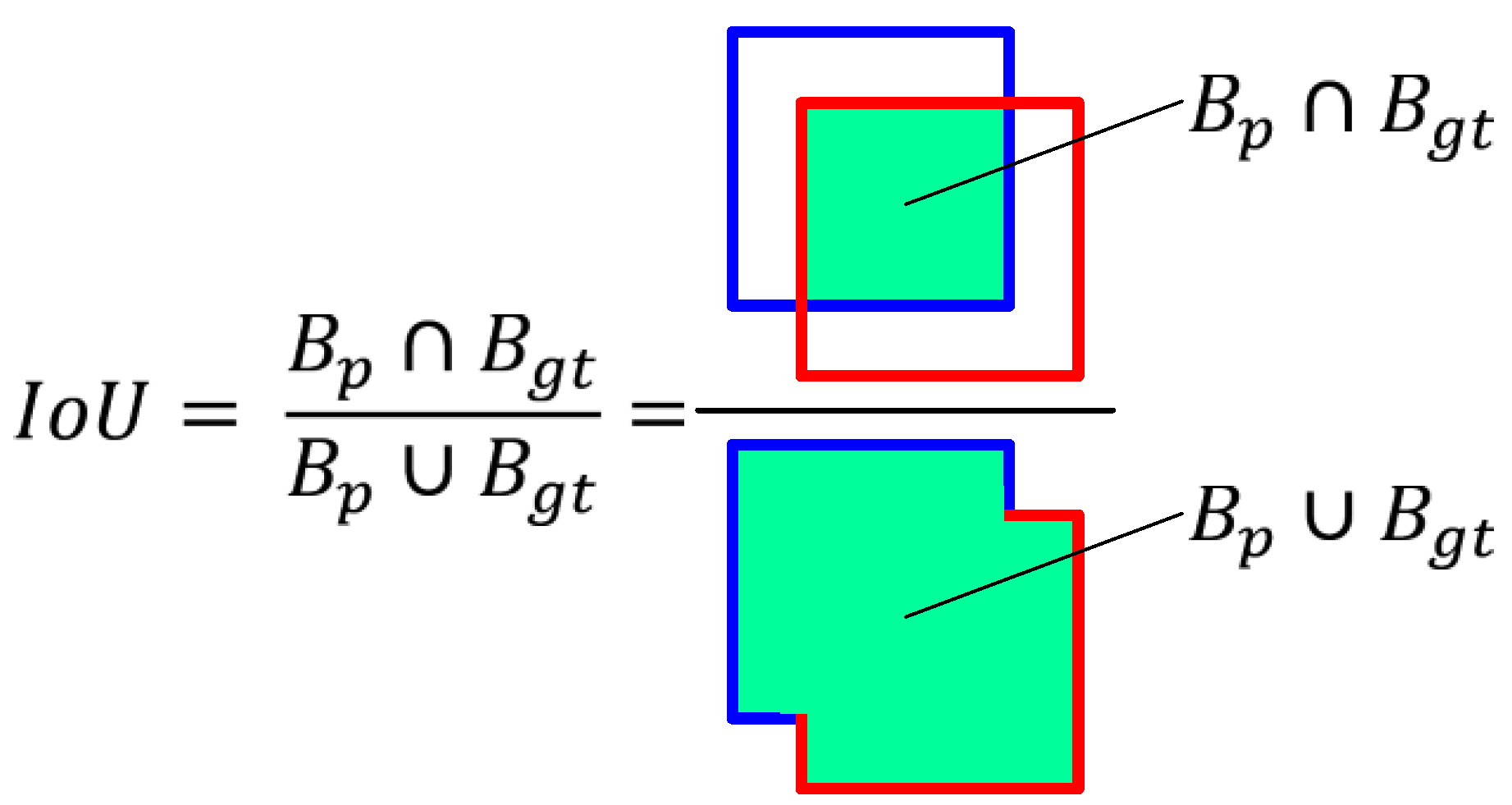

2.2. Assessing the Quality of Object Detectors

Most indexes for assessing the quality of object detection are based on two key concepts, these are prediction confidence and Intersection over Union (IoU). Prediction confidence is a probability estimated by a classifier that a predicted bounding box contains an object. IoU, on the other hand, is a measure based on the Jaccard index that evaluates the overlap between two bounding boxes—the predicted (

Bp) and the ground-truth (

Bgt). With IoU, it is possible to determine whether the detection is correct or not. The measure is the area of overlap between the predicted and ground-truth frames divided by the area corresponding to the sum of the two frames (

Figure 4).

Prediction confidence and IoU are used as criteria for determining whether object detection is true positive or false positive. Based on these, the following detection results can be determined:

True Positive (TP). A detection is considered true positive when it meets three conditions:

the prediction confidence is greater than the accepted detection threshold (e.g., 0.5);

the predicted class is the same as the class corresponding to the ground-truth box;

the predicted bounding box has an IoU value greater than the detection threshold.

Depending on the metric, the detection threshold is usually set to 50%, 75% or 95%.

False Positive (FP). This is a false detection and occurs when either of the last two conditions is not met.

False Negative (FN). This situation occurs when the prediction confidence is lower than the detection threshold (no ground-truth box detected).

True Negative (TN). This result is not used. During object detection, there are many possible bounding boxes that should not be detected in the image. So, a TN value would mean all possible bounding boxes that were not correctly detected (there are a lot of them in the image).

The detection results allow calculating the values of 2 key quality measures, which are precision and sensitivity.

Precision is an ability of the model to detect only correct objects. It is a ratio of the number of true positive (correct) predictions to the number of all predictions (1):

Recall determines the model’s ability to detect all valid objects (all ground-truth boxes). It is a ratio of the number of true positive (correct) predictions to the number of all ground-truth boxes (2):

Precision-recall curve. One way to evaluate the performance of an object detector is to change the level of detection confidence and plot a precision-recall curve for each class of objects. An object detector of a certain class is considered good if its precision remains high as the recall increases. This means that if the detection confidence threshold changes, the precision and recall will still remain high. Put a little differently, a good object detector detects only the right objects (no false-positive predictions means high precision) and detects all ground-truth boxes (no false-negative predictions means high recall).

Average precision. Precision-recall curves often have a zigzag course, running up and down and intersecting each other. Consequently, comparing curves belonging to different detectors on a single graph becomes a difficult task. Therefore, it is helpful to have an average precision (AP), which is calculated by averaging the precision values corresponding to sensitivities varying between 0 and 1. The average precision is calculated separately for each class. There are 2 approaches to calculating average precision. The first involves interpolating 11 equally spaced points. The second approach, introduced in the 2010 PASCAL VOC competition, involves interpolating all data points. The average precision is calculated for a specific IoU threshold, such as 0.5, 0.75, etc.

The 11-point interpolation approximates the precision-recall curve by averaging the precision for a set of 11 equally spaced recall levels [0, 0.1, 0.2, ..., 1] (3):

where the interpolated precision

at a specific recall level

r is defined as the maximum precision occurring for the recall level

(4):

In the second method, instead of interpolation based on 11 equally spaced points, interpolation for all points is used (6):

where

are the recall levels (in ascending order) at which the precision is interpolated.

Mean AP. Average precision covers only one class, while object detection mostly involves multiple classes. Therefore, mean average precision (mAP) is used for all K classes (6):

Inference time. Inference time is a time it takes for a trained model to make a prediction of new, previously unknown data on a single image. When detecting objects in video sequences, in addition to inference time, a second parameter is often used, namely the frame rate per second (FPS). This parameter indicates the frequency at which inference is performed for successive frames of the video stream. The choice of object detection model depends on the specific requirements of the application. Some of them favour accuracy over speed (as in our research), while others prefer faster processing, especially in real-time applications. Consequently, researchers and developers often use FPS as a critical factor when deciding which model to implement for a particular use case. Be aware that the FPS value depends on the inference time, but also on the duration of additional operations, such as image capture, pre-processing, post-processing, displaying the results on the screen, etc... The values of inference time and FPS depend on the architecture of the model and the hardware/software platform on which the model was run.

2.3. Preparing the Dataset

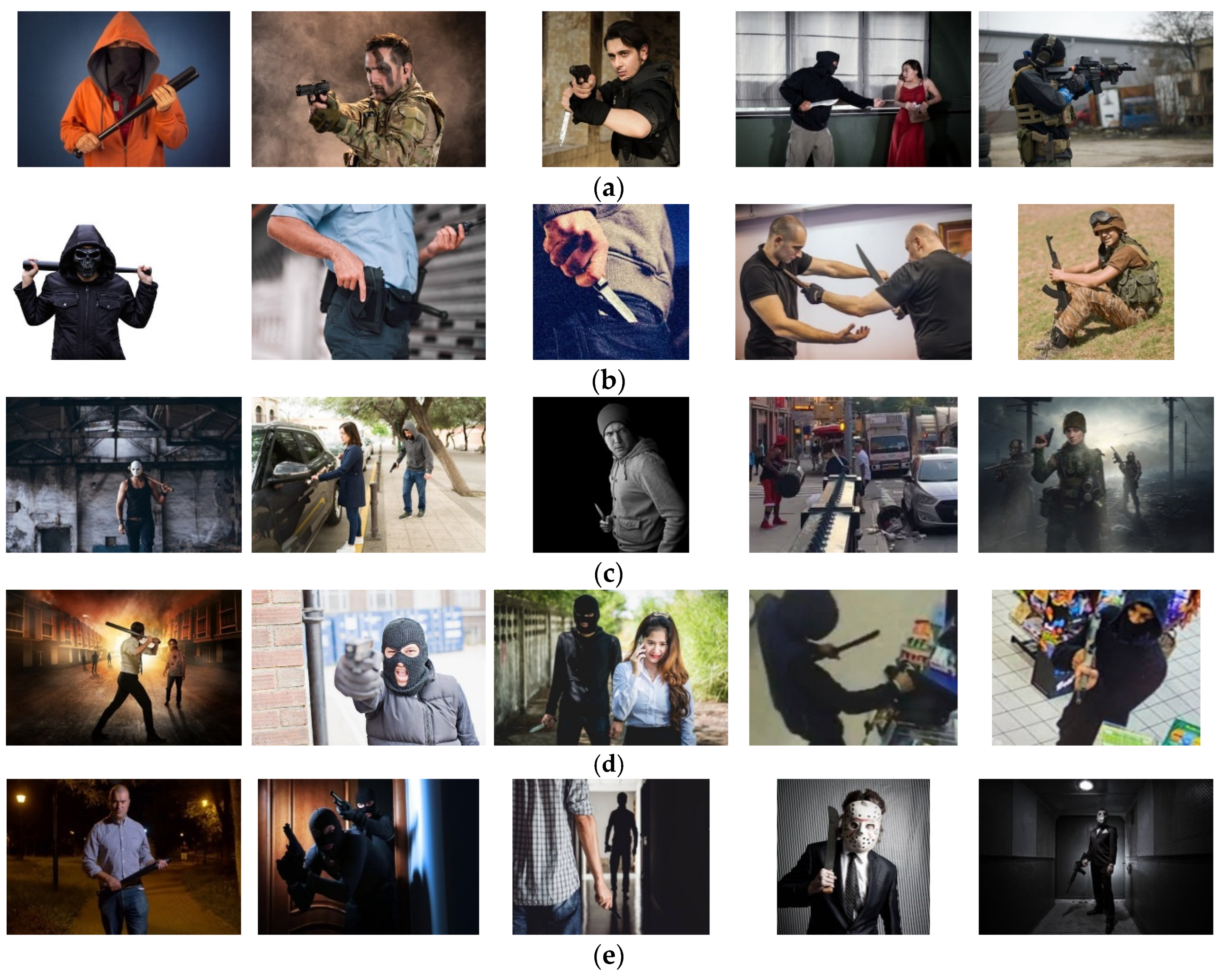

The dataset used did not come from a single, well-defined repository. It was prepared specifically for the research conducted. In order to gather it, a search was made through a number of sources available on the Internet, offering free access to the collected resources. An important issue during the search for images was that they should cover different situations and different conditions of image acquisition by surveillance cameras installed in public places. Accordingly, the following categories of images can be distinguished in the collected dataset (

Figure 5): objects clearly visible, objects partially covered, small objects, poor objects sharpness, and poor objects illumination. During the image search, care was taken to ensure that the collected dataset was balanced, that is, that a similar number of classes of detected objects (baseball bat, gun, knife, machete, rifle) was maintained.

As part of the image’s preparation for the study, they were scaled (and cropped where necessary) so that the smaller side was no shorter than 600 pixels and the larger one was no longer than 1,000 pixels. This operation was conditioned by the requirements of the Faster R-CNN. The next stage of data preparation was image labelling. This activity consisted of marking the detected objects on the images using bounding boxes. Label Studio was used for this purpose [

23]. The image annotations were saved in the Pacal VOC format, according to which the description about each image is included in the corresponding XML file.

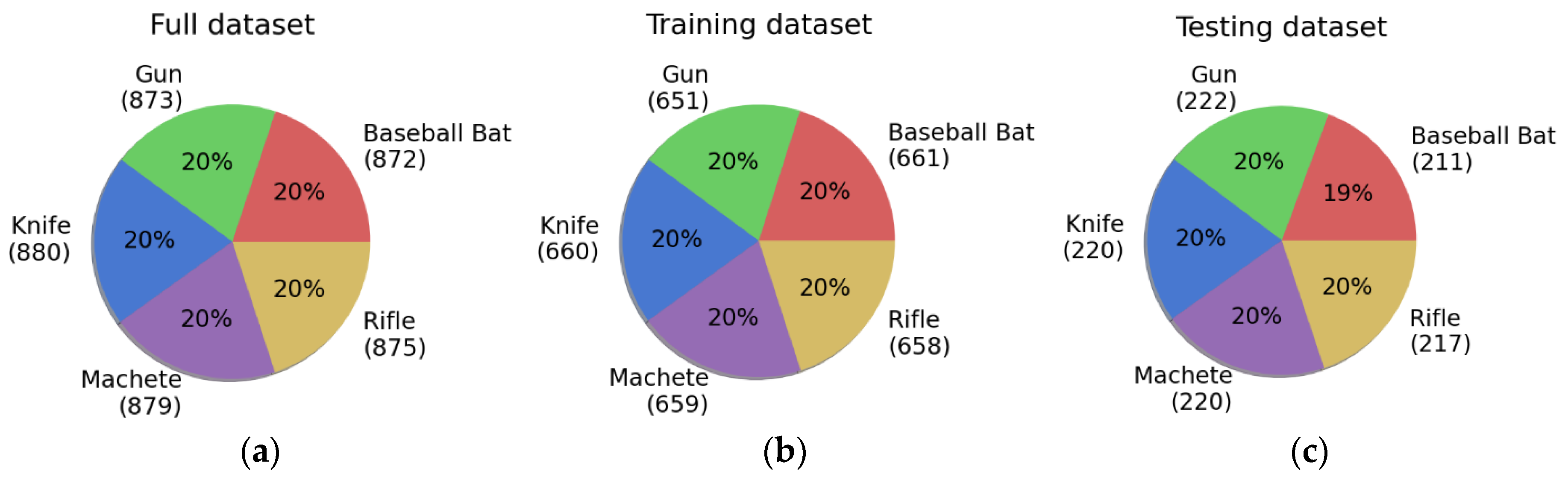

The full dataset contained 4,000 images. This set was randomly divided into training set (75% of the full set) and test set (25% of the full set). As a result, the training set contained 3,000 images, and the test set—1,000.

Figure 6 details the number of detected objects in each of the aforementioned sets.

5. Conclusions

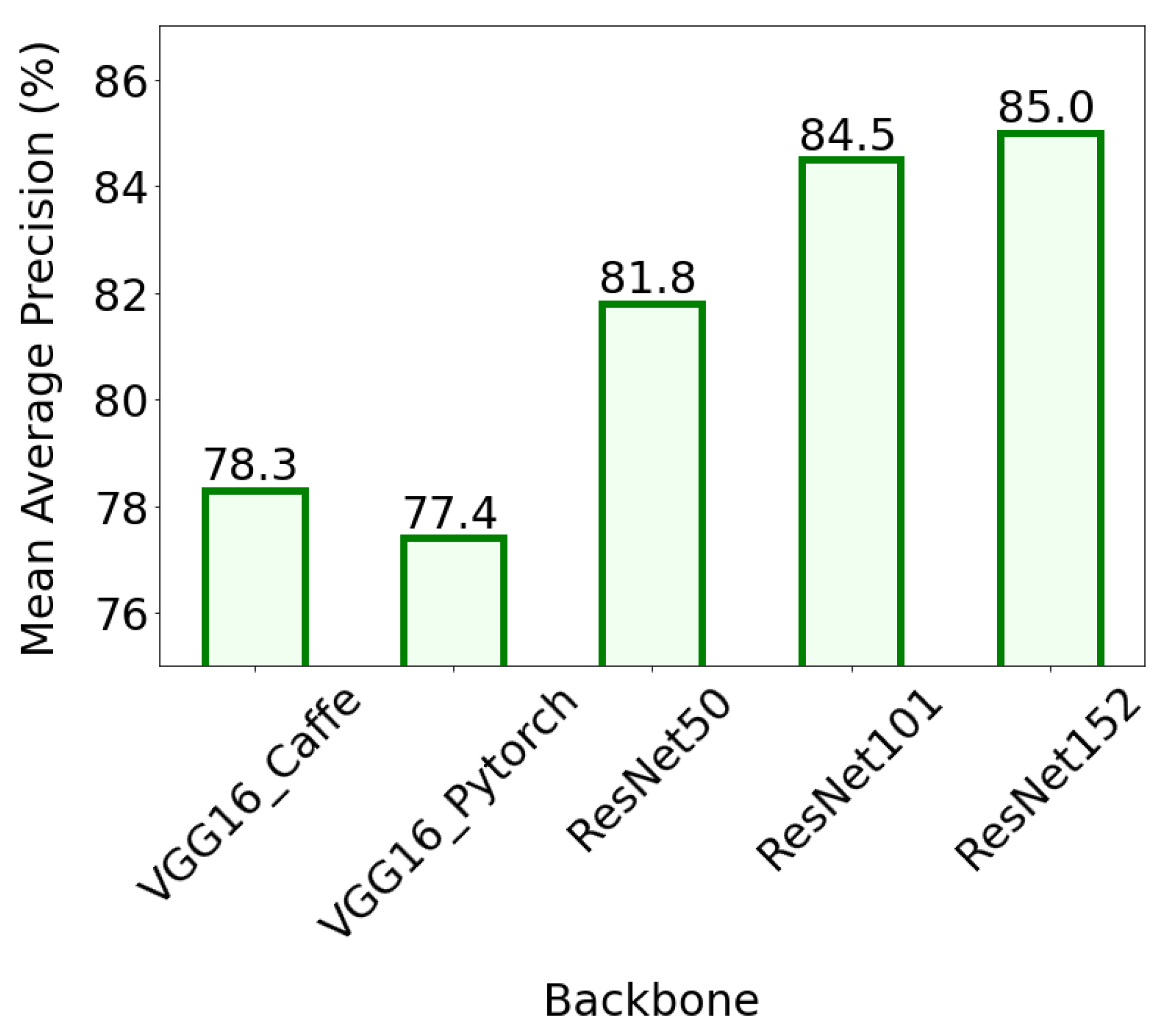

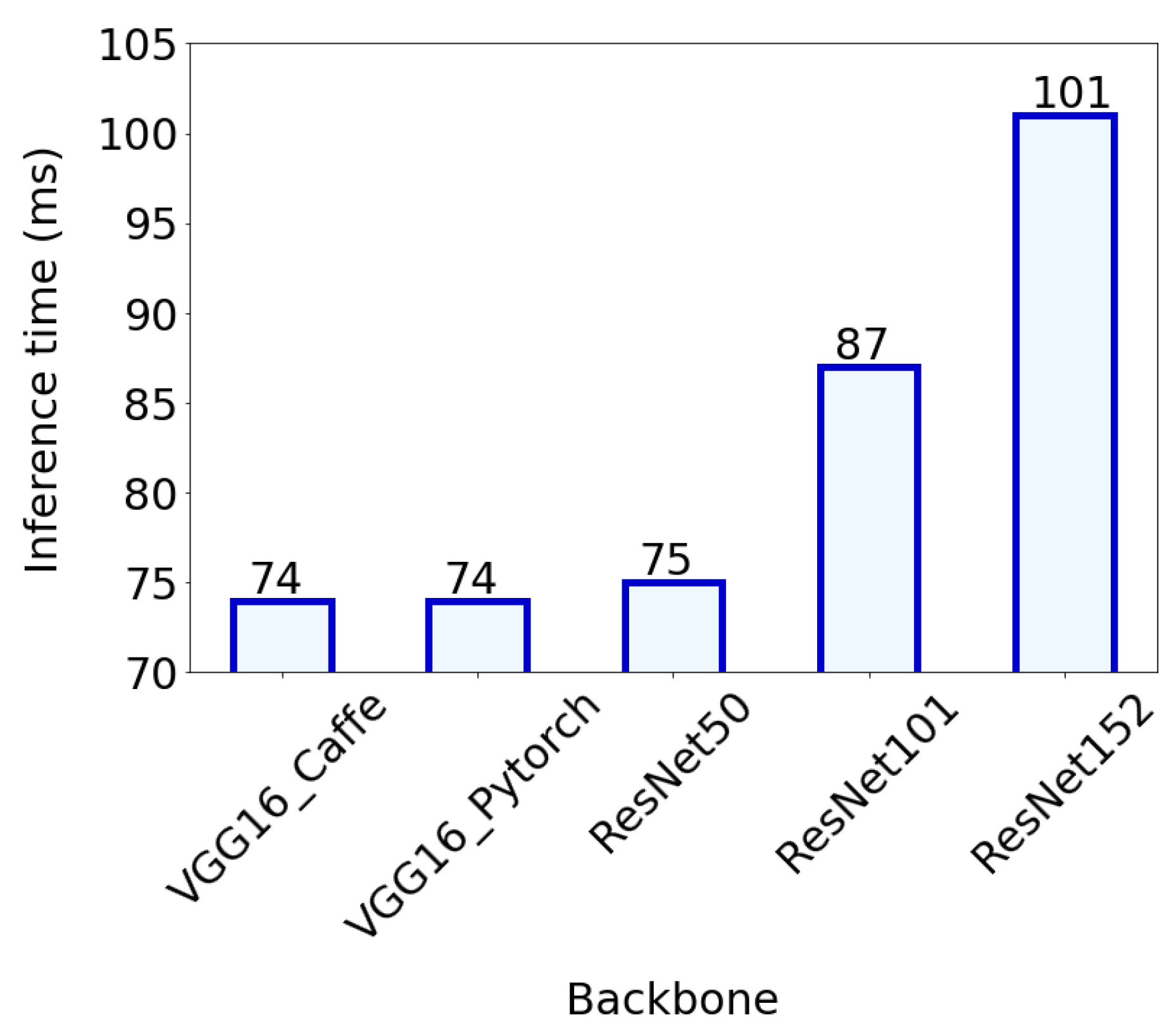

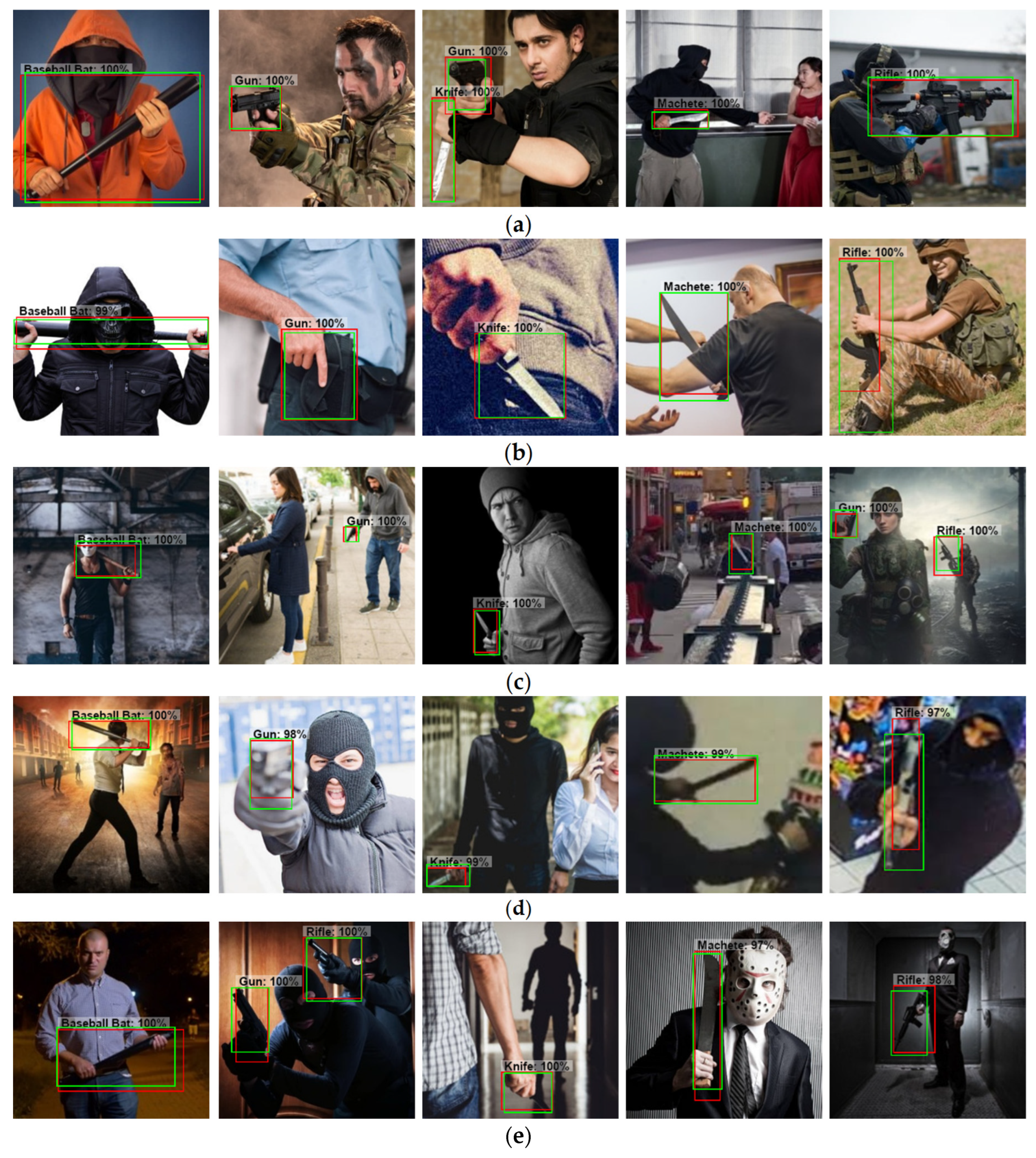

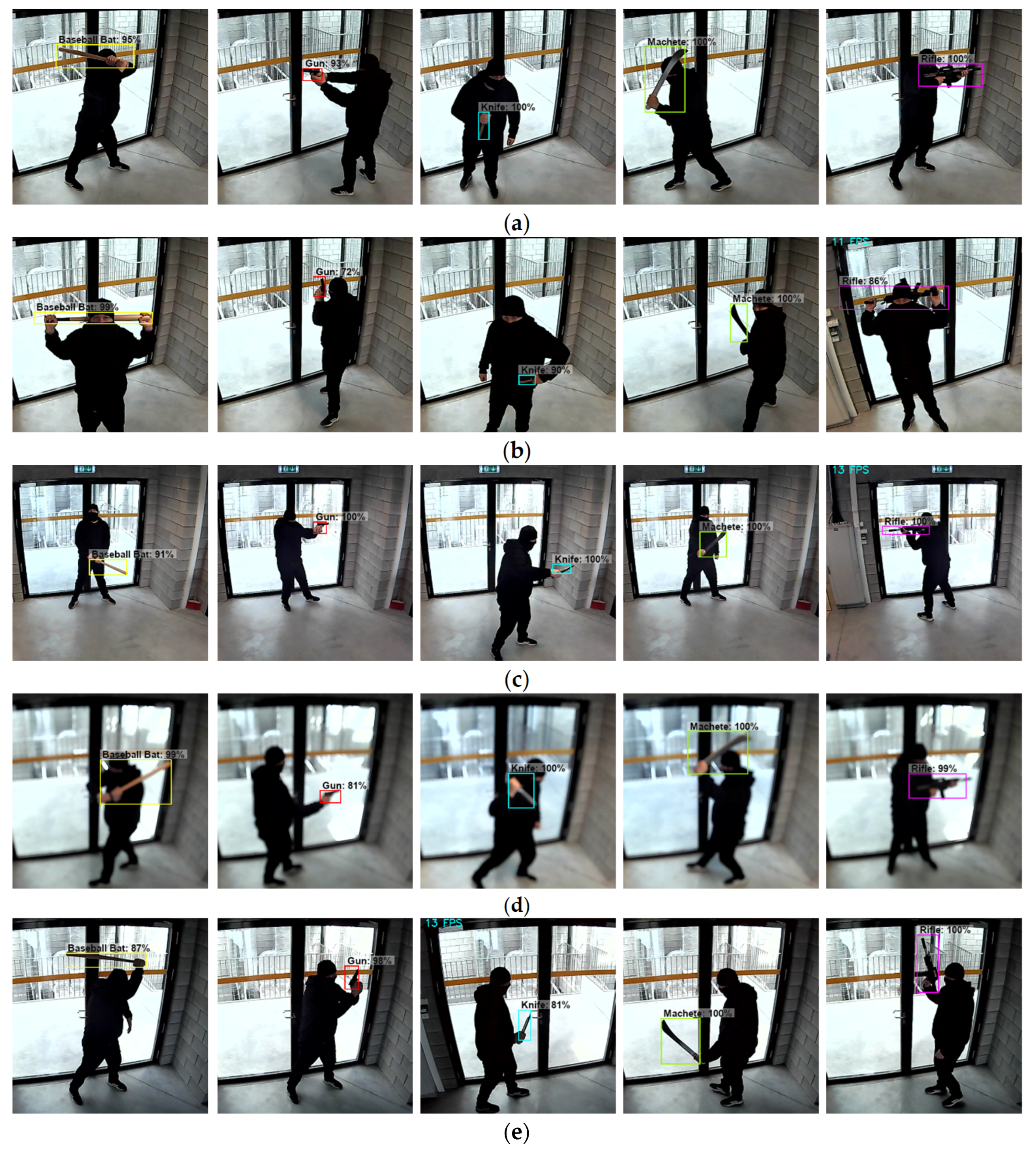

As a result of the study, 5 models were built, of which the most effective one, based on the ResNet152 backbone, achieved a mAP value of 85%. This is a very good result, if we take into account the specifics of the dataset used. It consisted (in similar proportions) of images in which the detected objects were: clearly visible, partially obscured, small, indistinct (partially blurred) and faintly visible (dark). This structure of the collection was a factor in increasing the difficulty of the object detection task. The evaluation conducted on the test set and the prediction of new images using an ordinary webcam showed that the ResNet152 model performs very well in detecting objects, regardless of the quality of the input image. Also, the processing speed of video frames is satisfactory. In the computer system used in the experiments, the value of the mentioned parameter was 11-13 FPS, which gives the possibility of practical application of the proposed solution. The obtained results entitle to recommend the Faster R-CNN with the ResNet152 backbone network for use in public monitoring systems, whose task is to detect specific objects (e.g., potentially dangerous objects) brought by people to the premises of various facilities. The research used a specific set of these objects (baseball bat, gun, knife, machete, rifle), but according to the goal set for the monitoring system, this set can be expanded or modified accordingly.

Figure 1.

Number of active shooter incidents in the United States from 2000 to 2022 (

a) and number of robberies in the United States in 2022, by weapon used (

b). Source:

https://www.statista.com.

Figure 1.

Number of active shooter incidents in the United States from 2000 to 2022 (

a) and number of robberies in the United States in 2022, by weapon used (

b). Source:

https://www.statista.com.

Figure 2.

Number of robberies in the United States in 2022, by location category [

2].

Figure 2.

Number of robberies in the United States in 2022, by location category [

2].

Figure 4.

Illustration of IoU parameter for predicted box Bp (blue) and ground-truth box Bgt (red).

Figure 4.

Illustration of IoU parameter for predicted box Bp (blue) and ground-truth box Bgt (red).

Figure 5.

Example images showing the presentation quality of objects subject to detection: (a) objects clearly visible; (b) objects partially covered; (c) small objects; (d) poor objects sharpness; (e) poor objects illumination.

Figure 5.

Example images showing the presentation quality of objects subject to detection: (a) objects clearly visible; (b) objects partially covered; (c) small objects; (d) poor objects sharpness; (e) poor objects illumination.

Figure 6.

The number of detected objects in the full (a), training (b) and test (c) datasets.

Figure 6.

The number of detected objects in the full (a), training (b) and test (c) datasets.

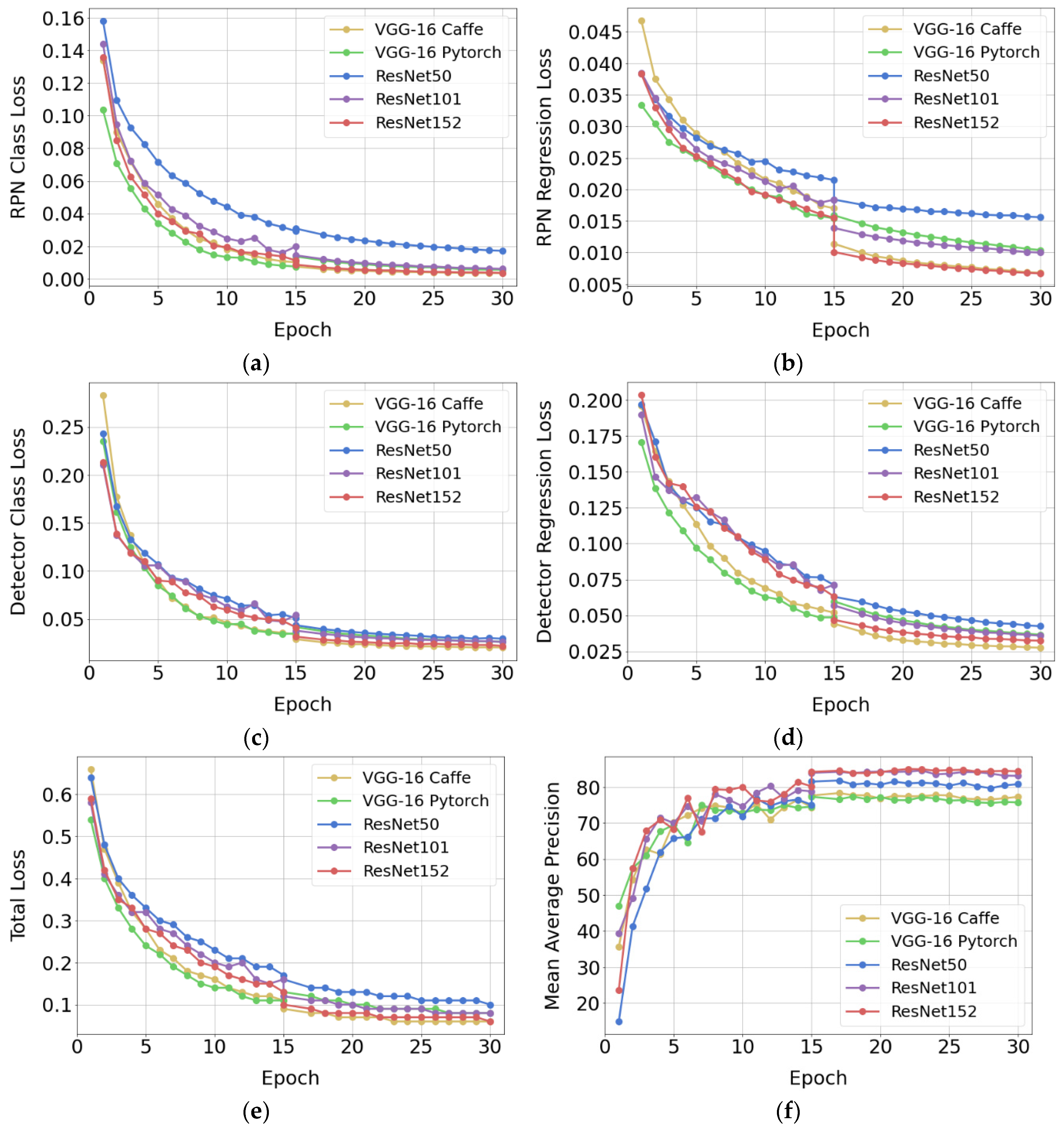

Figure 7.

Network training results: (a) RPN Class Loss; (b) RPN Regression Loss; (c) Detector Class Loss; (d) Detector Regression Loss; (e) Total Loss; (f) Mean Average Precision.

Figure 7.

Network training results: (a) RPN Class Loss; (b) RPN Regression Loss; (c) Detector Class Loss; (d) Detector Regression Loss; (e) Total Loss; (f) Mean Average Precision.

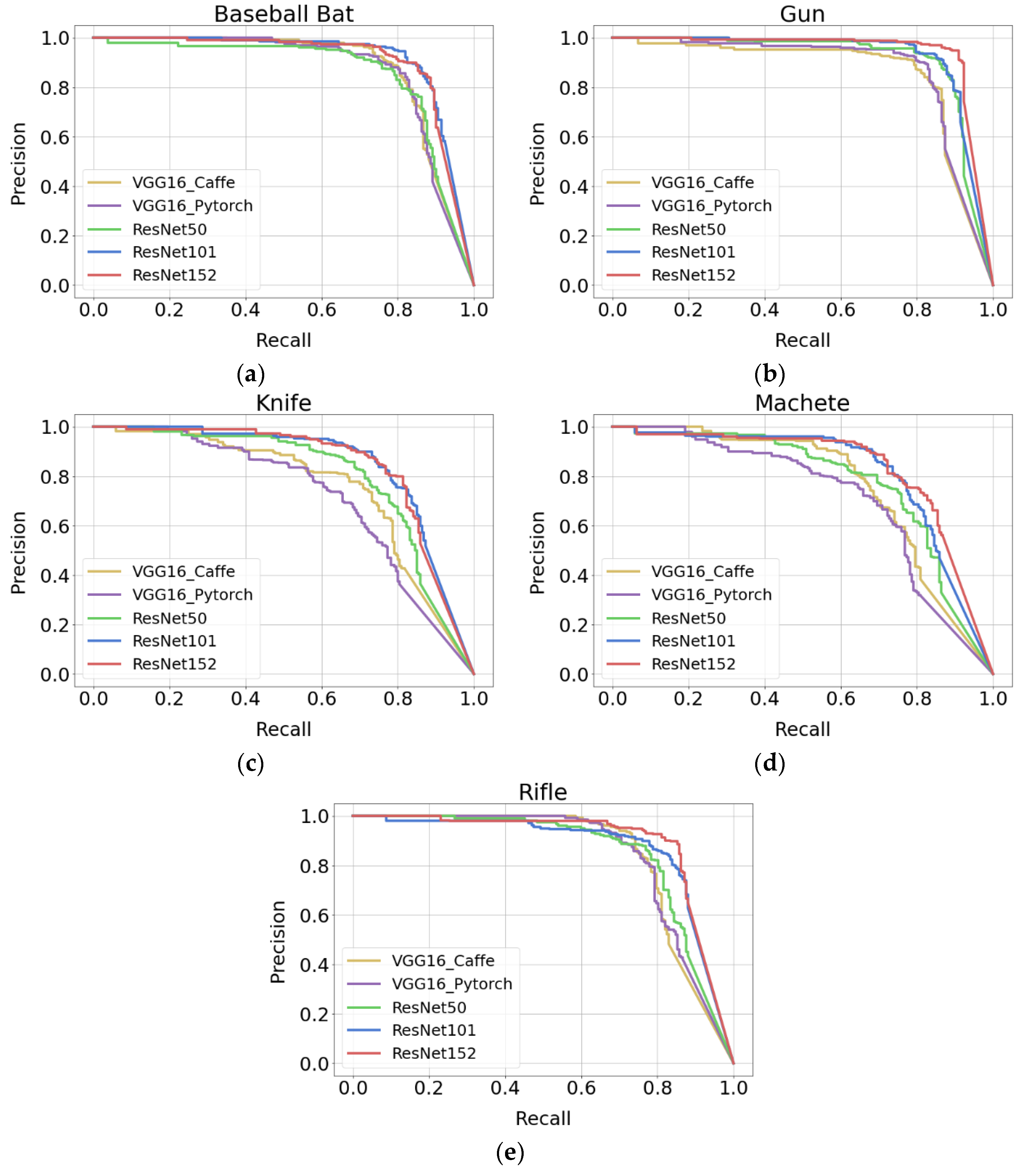

Figure 8.

Precision-recall plots for each category of detected objects: (a) baseball bat; (b) gun; (c) knife; (d) machete; (e) rifle.

Figure 8.

Precision-recall plots for each category of detected objects: (a) baseball bat; (b) gun; (c) knife; (d) machete; (e) rifle.

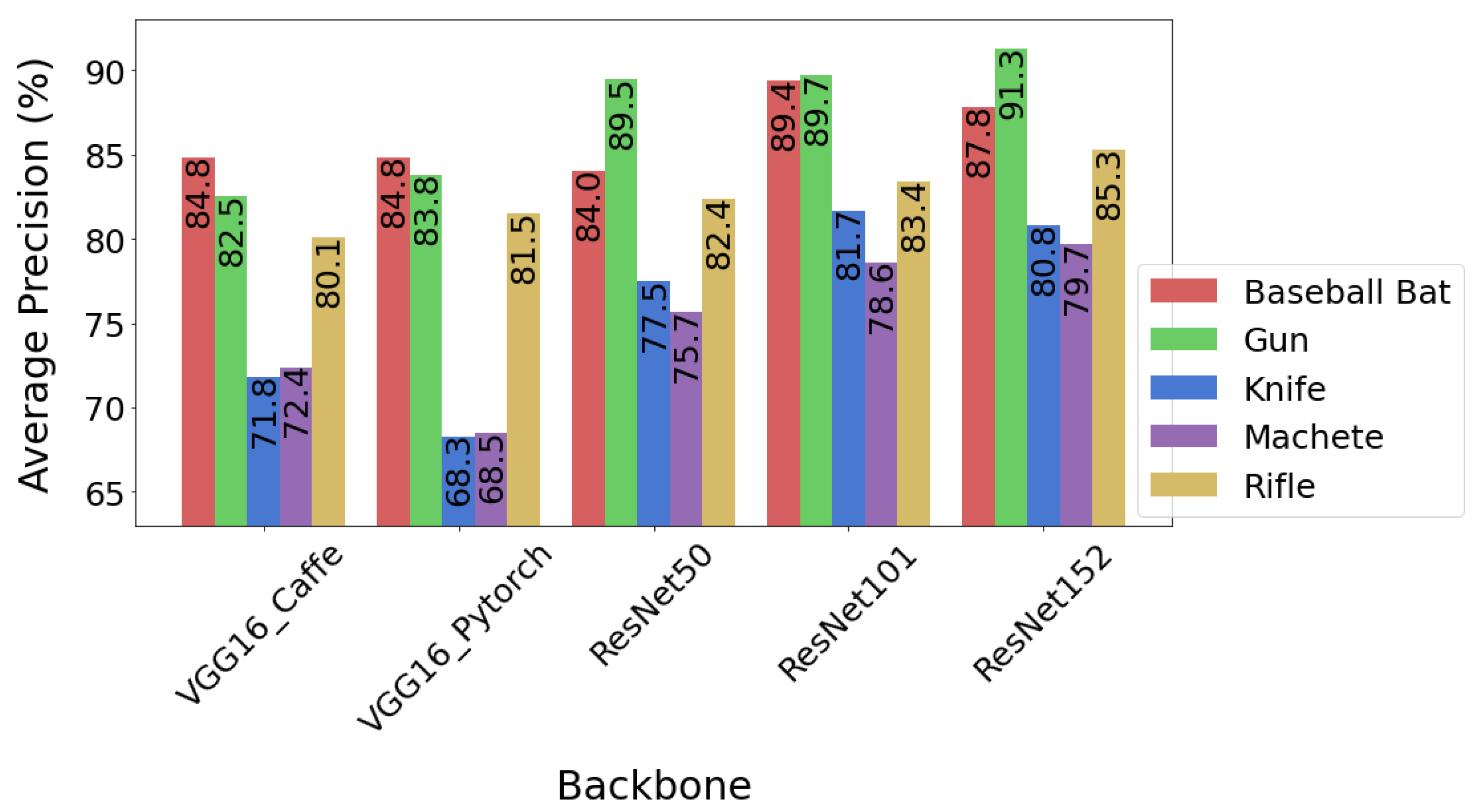

Figure 9.

Average precision of the object detection for individual backbone networks. The average precision was measured for an IoU threshold of 0.5.

Figure 9.

Average precision of the object detection for individual backbone networks. The average precision was measured for an IoU threshold of 0.5.

Figure 10.

Mean average precision for individual backbone networks.

Figure 10.

Mean average precision for individual backbone networks.

Figure 11.

Inference time averaged over 1000 test images.

Figure 11.

Inference time averaged over 1000 test images.

Figure 12.

Example results of detecting objects presented with different quality: (a) objects clearly visible; (b) objects partially covered; (c) small objects; (d) poor objects sharpness; (e) poor objects illumination. Ground-truth bounding boxes are drawn in green and prediction results are marked in red. The images have been cropped so that it is easier to compare the location of ground-truth and predicted bounding boxes.

Figure 12.

Example results of detecting objects presented with different quality: (a) objects clearly visible; (b) objects partially covered; (c) small objects; (d) poor objects sharpness; (e) poor objects illumination. Ground-truth bounding boxes are drawn in green and prediction results are marked in red. The images have been cropped so that it is easier to compare the location of ground-truth and predicted bounding boxes.

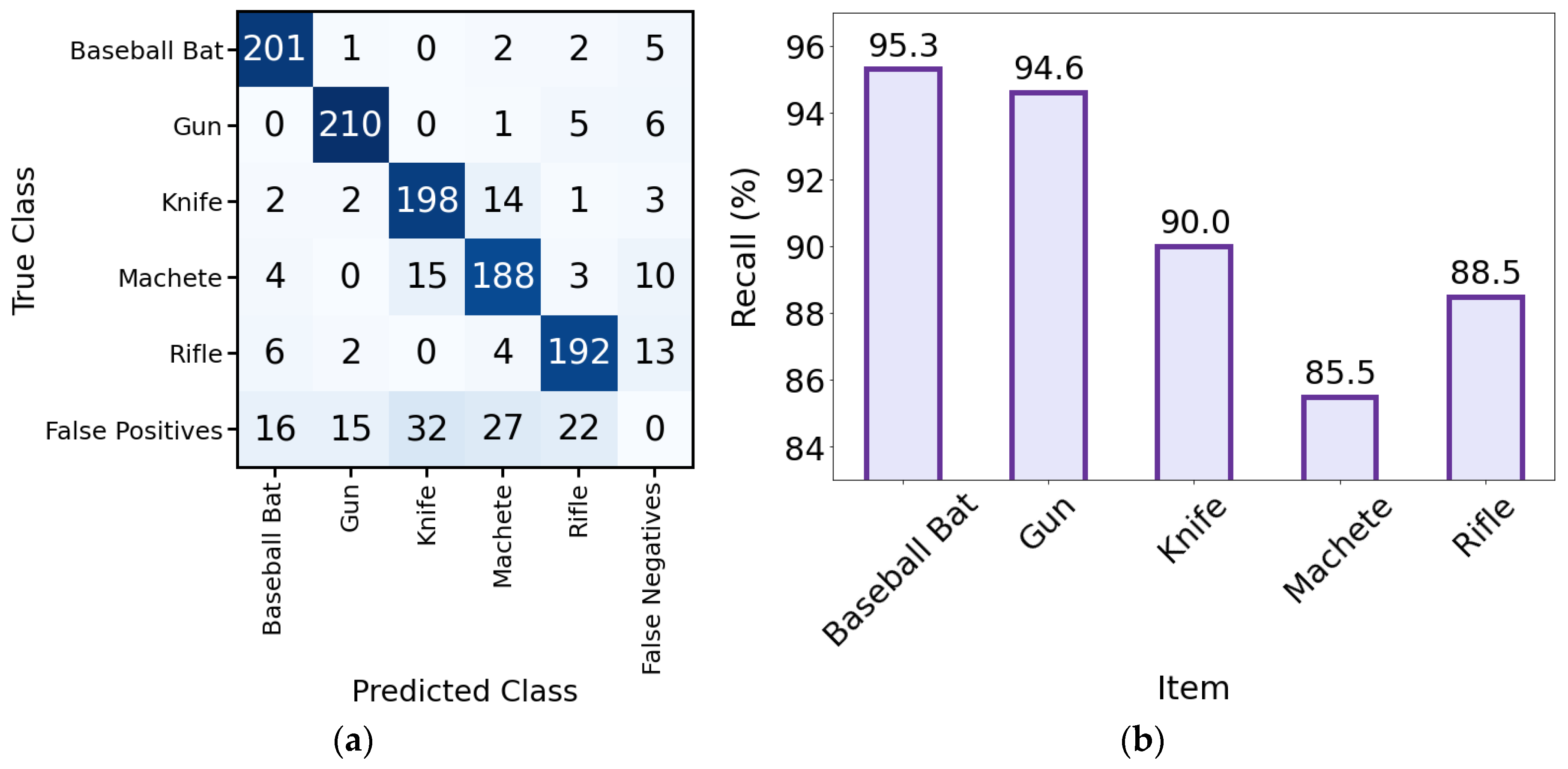

Figure 13.

Evaluation results of the model with the ResNet152 backbone: (a) confusion matrix; (b) recall of the model for individual items.

Figure 13.

Evaluation results of the model with the ResNet152 backbone: (a) confusion matrix; (b) recall of the model for individual items.

Figure 14.

Selected image frames recorded during detection of dangerous items in people entering the room: (a) objects clearly visible; (b) objects partially covered; (c) small objects; (d) poor objects sharpness; (e) poor objects illumination. For cases (a), (b), (d) and (e) the camera distance and installation height were 2.5 m. For case (c) the camera distance was increased to 5 m. The original image frame size was 800×600 pixels. In order to better present the detected objects, they were cropped to 600×600 pixels.

Figure 14.

Selected image frames recorded during detection of dangerous items in people entering the room: (a) objects clearly visible; (b) objects partially covered; (c) small objects; (d) poor objects sharpness; (e) poor objects illumination. For cases (a), (b), (d) and (e) the camera distance and installation height were 2.5 m. For case (c) the camera distance was increased to 5 m. The original image frame size was 800×600 pixels. In order to better present the detected objects, they were cropped to 600×600 pixels.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter values used during the models training process.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter values used during the models training process.

| Name |

Value |

| Epochs |

30 |

| RPN mini-batch |

256 |

| Proposal batch |

128 |

| Object IoU threshold |

0.5 |

| Background IoU threshold |

0.3 |

| Dropout |

0.0 |

| Loss function |

multi-task loss function 1

|

| Optimizer |

stochastic gradient descent (SGD) |

| Learning rate |

10-3 (epochs 1-15), 10-4 (epochs 16-30) |

| Momentum |

0.9 |

| Weight-decay |

5×10-4

|

| Epsilon |

10-7

|

| Augmentation |

– |

Table 2.

Total training time.

Table 2.

Total training time.

| VGG-16 Caffe |

VGG-16 Pytorch |

ResNet50 |

ResNet101 |

ResNet152 |

| 3h 43m 10s |

4h 10m 39s |

3h 42m 9s |

4h 17m 10s |

6h 25m 13s |

Table 3.

Results of similar studies using Faster R-CNN. A standard IoU threshold of 0.50 was used for all measures.

Table 3.

Results of similar studies using Faster R-CNN. A standard IoU threshold of 0.50 was used for all measures.

| No. in Refs. |

Backbone |

mAP0.5 (%) |

AP0.5 (%) |

mAR0.5 (%) |

AR0.5 (%) |

| Own results |

ResNet152 |

85.0

(baseball bat, gun, knife, machete, rifle) |

87.8 (baseball bat)

91.3 (gun)

80.8 (knife)

79.7 (machete)

85.3 (rifle) |

90.6

(baseball bat, gun, knife, machete, rifle) |

95.3 (baseball bat)

94.6 (gun)

90.0 (knife)

85.5 (machete)

88.5 (rifle) |

| [6] |

CNN |

– |

84.7 (gun) |

– |

86.9 (gun) |

| [8] |

CNN |

84.6 (gun, rifle) |

– |

– |

– |

| [10] |

VGG-16 |

– |

84.2 (gun) |

– |

100 (gun) |

| [24] |

|

80.5

(axe, gun, knife, rifle, sword) |

96.6 (gun)

55.8 (knife)

100 (rifle) |

65.8

(axe, gun, knife, rifle, sword) |

61 (gun)

52 (knife)

96 (rifle) |

| [25] |

VGG-16 |

79.8

(gun, rifle) |

80.2 (gun)

79.4 (rifle) |

– |

– |

| [26] |

Inception-ResNetV2 |

– |

79.3 (gun) |

– |

68.6 (gun) |

| [27] |

ResNet50 |

– |

88.12 (gun) |

– |

100 (gun) |

| [28] |

Inception-ResNetV2 |

– |

86.4 (gun) |

– |

89.25 (gun) |

| [29] |

SqueezeNet |

– |

85.4 (gun) |

– |

– |

| GoogleNet |

– |

46.7 (knife) |

– |

– |