1. Introduction

The integration of Virtual Reality (VR) technology in education has gained significant attention in recent years, as it offers a unique opportunity for learners to engage in immersive and interactive learning experiences [

1,

2]. However, for educators and instructional designers who are not experts in information technology, the process of selecting and implementing VR software can be daunting. This article aims to provide a non-technical guide for educators, instructional designers, and researchers who are interested in exploring the potential of VR in education but lack the technical expertise to navigate the complex landscape of VR software solutions.

The target audience for this article includes individuals who are responsible for designing and implementing educational programs, such as teachers, professors, instructional designers, and curriculum developers. These individuals often face the challenge of selecting the most suitable VR software solutions for their specific instructional needs, without having to delve into the technical details of the software.

The increasing popularity of VR in education is driven by its potential to enhance student engagement and motivation, as well as its ability to provide a more immersive and interactive learning experience [

3]. One of the key benefits of VR in education is its ability to provide a safe and controlled environment for learners to practice and develop social skills, such as communication, collaboration, and conflict resolution [

4,

5]. In the real world, it can be difficult for learners to find opportunities to practice such social skills, especially in situations that may be uncomfortable or intimidating. VR, on the other hand, allows learners to practice these skills in a virtual environment that is tailored to their needs and comfort level [

6].

To address the requirements of our target audience, we have conducted an extensive review of the literature on VR in education, as well as an analysis of the current market offerings of VR software solutions. Our research has identified several key players in the VR education market, including companies that offer a range of VR software solutions, from basic educational platforms to more advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI)-powered tools. We will provide a brief overview of these companies, highlighting selected key features, benefits, and limitations, as well as their potential applications in education.

Our goal is not to provide an exhaustive review of all VR software solutions available, but rather to offer a starting point for educators and researchers who are interested in exploring the potential of VR in education. By providing a concise and accessible overview of the current state of VR software solutions, we hope to facilitate the process of selecting and implementing VR software, and to encourage educators and researchers to explore the many benefits of VR in education.

In the following section, we will provide a theoretical overview of the utilization of VR technology in education, which will lead to the formulation of a research question. Subsequently, in the methodology section, we will describe the search for providers of VR software in education and the criteria used to select the providers. In the results section, we will present the results of the search for providers of VR software in education, including a comprehensive table of ten key players in the VR education market. This table will provide a concise and accessible summary of their key features. We will also offer additional information and examples to illustrate the potential of VR in education, including screenshots of VR software solutions.

2. Theoretical Background

VR refers to a computer-generated

, three-dimensional environment that enables users to engage with digital content in a highly interactive manner. The Cognitive Affective Model of Immersive Learning (CAMIL) by Makransky and Petersen [

7] identifies two key elements that are essential for learning in VR:

presence and

agency. Presence refers to the subjective experience of

“being there” in the virtual environment, which can enhance engagement and emotional investment in the learning process. Agency, on the other hand, describes the degree to which users perceive that they can influence the virtual world through their actions. When learners feel a strong sense of agency, they are more likely to engage in active learning processes, leading to improved comprehension and retention of knowledge. VR’s potential for learning is rooted in its ability to create immersive experiences that combine these elements. By fostering presence, learners experience a heightened sense of realism that can enhance their cognitive and emotional responses to educational content. Simultaneously, high levels of agency allow users to experiment, make decisions, and observe the consequences of their actions, which is particularly valuable in training scenarios that involve complex decision-making or procedural knowledge acquisition [

4,

8,

9].

VR technology enables the creation of learning experiences that would otherwise be inaccessible due to logistical, financial, or safety constraints, such as practicing social skills in realistic settings, which is especially advantageous for the development of those skills, where repeated practice in authentic environments is crucial [

10]. For example, research has shown that VR-based training in communication and leadership skills leads to measurable improvements in real-world interactions [

11,

12]. Similarly, VR has been used to train healthcare professionals in patient communication, enabling them to practice sensitive conversations in a risk-free environment [

13,

14]. Furthermore, a study by Seufert et al. [

15] found that VR-based training in classroom management skills, such as classroom organization and student behavior management, significantly improved student teachers' competency. Moreover, a study by Hassan et al. [

16] explored the use of AI-driven talking avatars in VR for investigative interviews of children, demonstrating the potential of VR to create realistic and interactive environments for sensitive conversations. These characteristics make VR a powerful tool for education, providing unique learning experiences that are otherwise difficult, too costly, or impractical to achieve through traditional instructional methods.

The technological landscape of VR systems is diverse and varies in complexity, ranging from high-end head-mounted displays (HMDs) to more accessible mobile VR solutions. High-end devices, such as

Meta Quest or

HTC Vive, provide full spatial tracking and realistic rendering, enabling users to move freely and interact naturally within the virtual space. These systems often require powerful computing hardware to run complex simulations, making them suitable for highly immersive experiences. In contrast, mobile VR solutions, such as

Google Cardboard, use smartphones as display and processing units, making them more affordable but significantly less immersive [

17,

18].

VR hardware is often categorized based on its level of immersion. Less-immersive VR systems, such as 360-degree videos and desktop VR applications, provide a limited sense of presence as users can observe the virtual environment but have restricted interaction capabilities [

19]. In contrast, high-immersive VR systems utilize advanced HMDs with real-time motion tracking and haptic feedback, allowing for a deeper sense of embodiment and interactivity [

20]. Research has demonstrated that high-immersion VR leads to greater learning gains by enhancing engagement and cognitive absorption [

7]. However, it also presents challenges such as increased cognitive load [

21], high costs and the need for specialized hardware [

22], which may limit its widespread adoption in educational settings.

Despite these challenges, VR's technological evolution continues to drive new educational applications. Studies have shown that immersive VR environments can significantly enhance the learning of procedural skills, such as surgical training [

23] or the training or automotive painting techniques [

24], as well as social skills, where authentic interaction scenarios are crucial for effective learning [

25].

Meanwhile, the application of VR in education spans various sectors, including vocational training, school education, and higher education. In vocational training, VR has been successfully implemented to enhance practical skill acquisition in fields such as medical training and industrial maintenance. Studies indicate that medical trainees who practice procedures in VR environments demonstrate improved accuracy and confidence in real-world applications [

26,

27]. Similarly, VR-based training programs in industrial settings allow learners to familiarize themselves with machinery and safety protocols without the risks associated with hands-on training [

28,

29]. In school education, VR is particularly valuable for teaching complex scientific concepts by enabling students to visualize and interact with abstract phenomena that would otherwise be difficult to grasp [

30,

31]. For example, research has shown that students who use VR to explore biological processes or physical simulations develop a deeper conceptual understanding compared to those using traditional instructional methods [

32]. Furthermore, VR technology can promote sustainable behavior and climate change awareness among young learners [

33]. In higher education, universities integrate VR into curricula to provide experiential learning opportunities. Virtual field trips, laboratory simulations, and interactive case studies allow students to engage with course material in ways that traditional classrooms cannot offer. The flexibility of VR-based learning environments also supports distance education by enabling remote students to participate in shared virtual spaces [

34].

Despite its potential, VR has not yet achieved widespread adoption in education [

22]. One major limitation is the lack of readily available and pedagogically sound VR software solutions. Many educators and institutions struggle to identify which VR applications effectively support their learning objectives. Furthermore, the rapid technological advancements in VR hardware have not always been matched by equally sophisticated educational software, leading to a gap between technological capability and practical usability in educational settings. This article seeks to address this issue by mapping existing commercial VR providers and their solutions for training social skills, with a particular focus on AI-driven conversational tools. By providing a structured overview of available software solutions, this study aims to support researchers and practitioners in selecting VR applications that align with their educational goals and instructional needs.

In summary, while the benefits and drawbacks of VR technology in educational settings have been well-documented in the research literature, researchers and practitioners in educational contexts who have determined that VR is the most appropriate tool for their specific learning environment still face a significant challenge. Without technical expertise in designing and developing their own VR environments using complex tools like Unity or Blender, they need suitable VR software that can be tailored to their specific instructional needs, learning objectives, and the needs of their learners. However, the market for VR technology is vast and complex, making it difficult to navigate. In this article, we therefore aim to address the following research question and provide researchers and practitioners with a first orientation guide.

This research question will be addressed in the following section, where we will present the results of our search on the current state of VR software solutions in education and provide recommendations for researchers and practitioners.

3. Methods

For our project, which focuses on enhancing the counseling competencies of German education science students in a virtual consulting room, we sought suitable VR software that would enable an authentic counseling experience. In the following methodological description, we outline the implementation of our market analysis.

Our exploratory search, conducted from April to October 2024, followed a four-phase snowball approach. The initial phase involved a literature review using

Google Scholar with the keywords

"Virtual Reality" AND

"multi-user" AND

"soft skills." This yielded numerous studies on social skill acquisition through VR, with a primary focus on the technical implementation of VR solutions. Exclusion criteria required that the solution be based on HMDs, offer a highly realistic virtual environment in terms of surroundings and avatars, and support communication scenarios for social competency development. Given the demonstrated advantages of high-immersive VR, such as increased engagement, cognitive absorption, and enhanced learning outcomes [

7,

20], only solutions leveraging advanced HMD technology were considered to ensure an optimal level of immersion for effective training.

Our

Google Scholar search identified, for example, a review article by Dhieb and Durado from 2024 [

35] on VR content creation for training purposes, which systematically examines various virtual soft skills training providers. These platforms offer interactive, immersive 360° computer-generated simulations to facilitate skills acquisition. Among the commercial VR providers mentioned were

Talespin and

PIXO VR. Similarly, Stiefelbauer et al. [

36] explored the potential of SocialVR in educational contexts, including virtual university campuses, 360° videos, and rhetorical training in VR. In SocialVR environments, multiple users can simultaneously interact within a virtual 3D space using an HDM. In most SocialVR platforms, users can create and modify their own avatars before engaging with others in the virtual space [

37]. For the virtual campus, Stiefelbauer and colleagues utilized

Mozilla Hubs, as it allows user registration without requiring personal data and supports both web browser and HMD access. Additionally, key criteria for selecting this platform included its capacity to accommodate at least 60 concurrent users and the ability to create custom virtual rooms. Their research also involved comparative testing of platforms such as

AltspaceVR,

EngageVR,

MeetingVR, and

Virbela [

36]. Zdunek and Bachmann [

38] developed a VR soft skills training program using the design software

iClone. Therefore, they created multiple training scenarios where learners assumed the role of a consultant interacting with a virtual counterpart, an NPC following a pre-scripted dialogue. NPC stands for Non-Player Character and refers to avatars in digital games that operate autonomously, controlled by a computer or AI rather than by a human player [

39].

Supplementing the literature review, we engaged directly with three researchers who already successfully used VR to acquire social skills in scientific studies [

36,

38,

40] to gain insights into their research projects and gather experiential knowledge regarding various VR providers. These discussions followed a structured checklist designed to collect detailed information on the VR applications they utilized. Key inquiries included identifying the developer of the application, determining whether a commercial provider was involved, and assessing the availability of the VR application as an Open Educational Resource (OER).

To complement the literature review, a targeted Google search was conducted to identify additional relevant providers. Search terms such as "Virtual Reality Training Provider" and "Virtual Reality Provider Social Skills Training" were employed. This process led to the identification of further providers, including PIXO VR, WondaVR, and Mursion. A detailed examination of their websites was followed by scheduled meetings to explore their applications and, where possible, test demo versions. These discussions were structured according to a predefined script, beginning with an outline of our specific requirements and expectations regarding a VR solution. The companies were then invited to present their software and demonstrate its potential suitability for our use case in the field of consulting. A standardized questionnaire was subsequently used to address key technical and functional aspects, including:

Is the software a VR or SocialVR solution?

Is it available for both HMD and desktop?

Is it possible to modify training scenarios or create new ones?

Does it include an authoring tool?

Does speech recognition work in German?

Is the speech output available in German?

Are avatars pre-scripted NPCs or AI-controlled NPCs?

What are the estimated costs?

Applications deemed promising were tested through demo versions, evaluating key criteria relevant to educational research, such as:

realism of the virtual environment

authenticity of interactions with virtual counterparts

functionality of speech recognition

complexity of creating or modifying training scenarios, particularly regarding programming or technical expertise requirements

Both Google Scholar and Google searches were further expanded through direct exchanges with providers. Discussions with individual companies often led to additional recommendations based on our specified criteria. For instance, PIXO VR suggested further exploration of Talespin and Bodyswaps.

Following this four-phase research process, we identified ten VR providers suitable for social skills development. The solutions differed in technical requirements, content offerings, and the degree of customization. The comparative analysis presented in this article synthesizes these findings, providing an overview based on ten key criteria. These criteria encompass technical feasibility (HMD or desktop VR), the availability and modifiability of avatars, the provided content and its adaptability, as well as communication within the simulation, specifically whether it occurs via an NPC or AI and how speech recognition functions. The results of our market analysis are presented in the following chapter, structured in two tables and complemented by additional informational materials.

4. Results

The following section presents two tables with providers and corresponding analysis criteria, covering technical requirements, avatar customization, training content, material adaptability, and communication features within the application. Based on our market analysis (outlined in the methodology section), we identified ten relevant providers: (1)

Bodyswaps, (2)

EngageVR, (3)

Mursion, (4)

PIXOVR, (5)

Polycular, (6)

Talespin, (7)

3spin, (8)

Virbela, (9)

VRChat, and (10)

WondaVR.

Table 1 focuses on technical prerequisites and communication aspects, while

Table 2 addresses content-related factors such as avatars and training materials. Each criterion is analyzed in detail, highlighting clear distinctions and providing selected examples from the software solutions. Comparisons between the providers are then presented based on these criteria, supplemented with images sourced from the respective providers´ websites or demo versions.

4.1. Software

The criterion

Software (see

Table 1) specifies whether the application is a VR or a SocialVR environment. With reference to social scenarios, the distinguishing factor between SocialVR and VR is the following: While SocialVR environments allows multiple users to interact and communicate with each other in real time, VR environments only enable social communication with a pre-programmed or AI-driven NPCs.

Bodyswaps,

PIXOVR,

Polycular,

Talespin,

3spin and

WondaVR are focused on VR applications, whereas

EngageVR,

Mursion,

VRChat, and

Virbela are categorized as SocialVR applications. However,

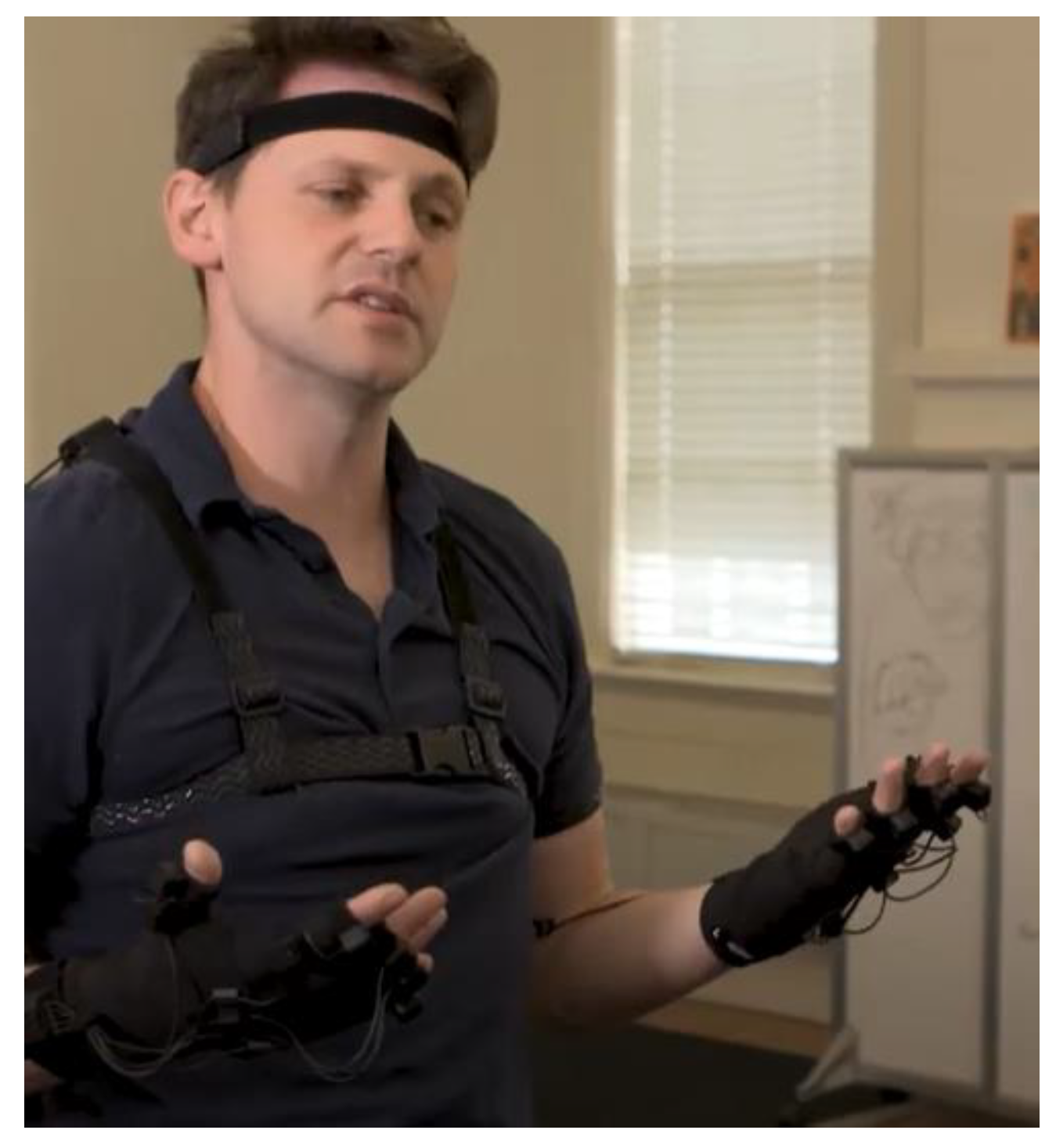

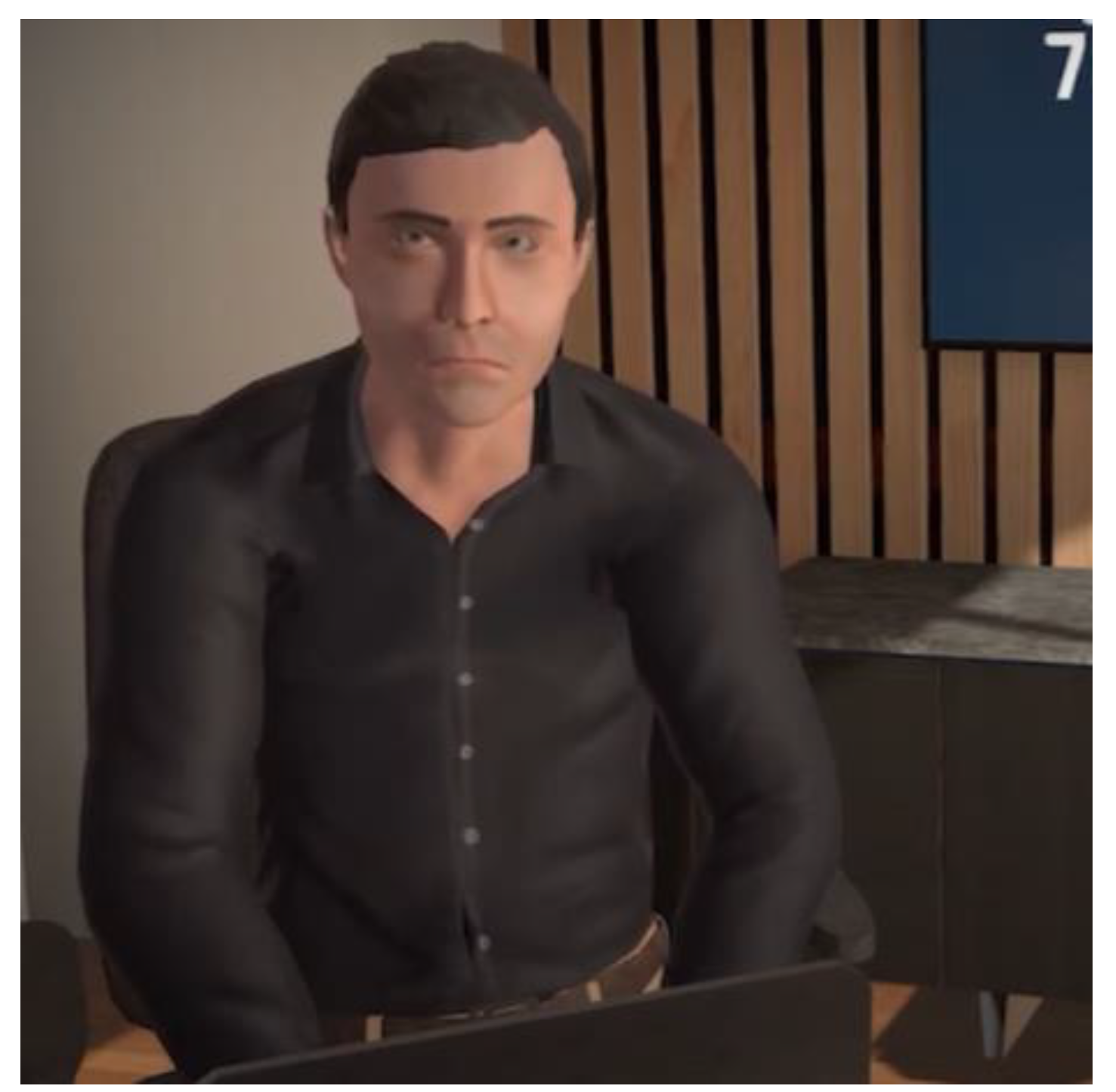

Mursion (see

Figure 1) represents a distinct software model, as it involves actors who control the avatars through haptic gloves during training sessions. These actors, briefed on the specific use case, can operate multiple avatars simultaneously, providing authentic simulation experience.

4.2. Technology

The criterion

technology refers to the types of technical devices. In

Table 1, a binary distinction is made between HMD and desktop VR. The classification as

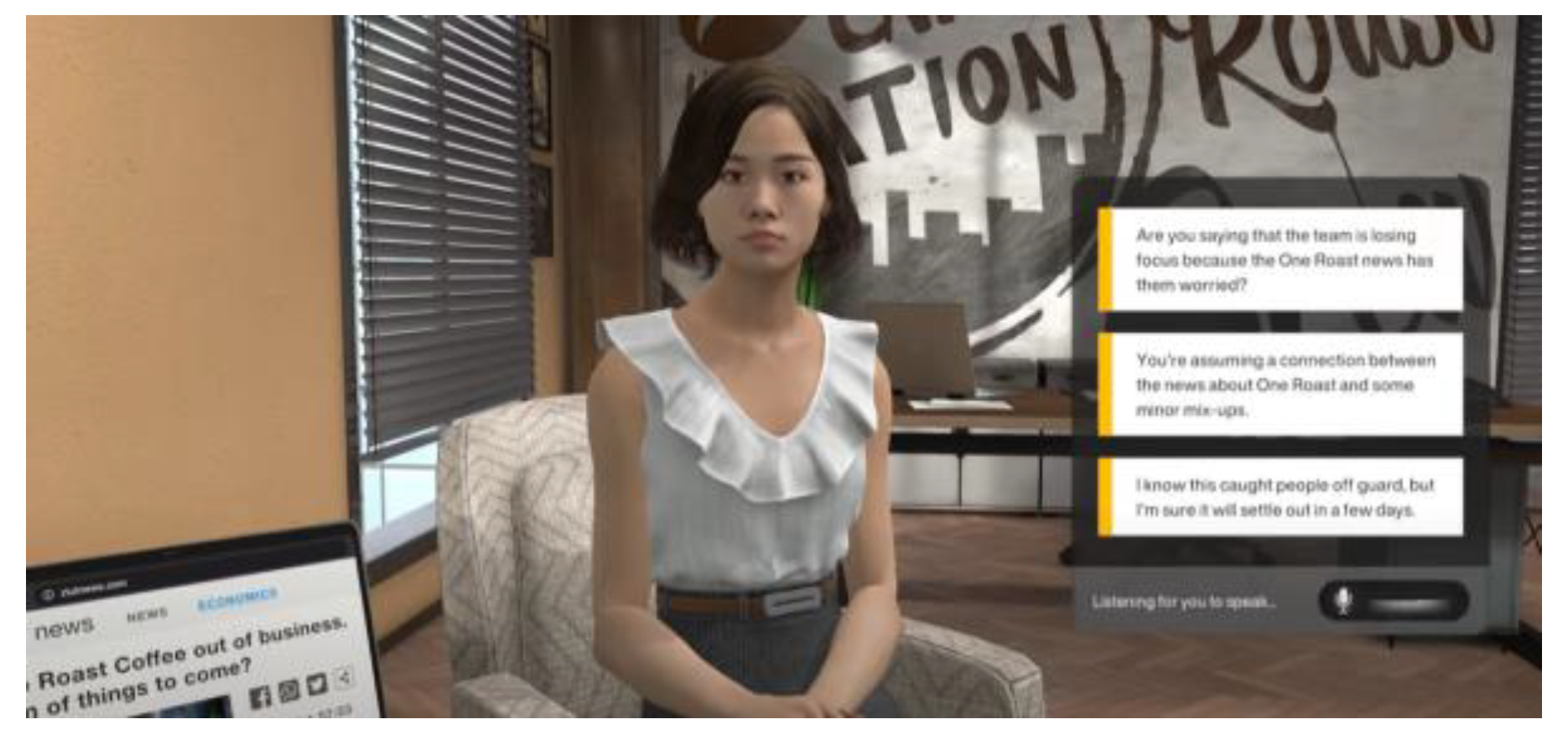

desktop indicates that the software can be accessed via a laptop or computer screen, as well as on mobile devices such as tablets. Most applications are compatible with both HMD and desktop. Only two providers restrict their software to a single platform:

Mursion to desktop (see

Figure 2) and

Polycular to HMD. However, in the case of

Polycular, this limitation applies exclusively to its

Virtual Skills Lab and not to other applications, such as virtual escape games (see also

Section 4.8 Exemplary Content Elements).

4.3. Communication

During our analysis, the following question arose: How does communication with an interlocutor function within the VR environment? The criterion communication seeks to answer that question by differentiating between three types of interaction: (1) scripted communication with an NPC, (2) AI-driven communication with an NPC, and (3) communication with a real person. Scripted communication means that the dialogue between the learner and the NPC within the software is pre-programmed so that the NPC replies according to a predefined pattern. The learner must either follow scripted options or provide free answers based on speech recognition. In contrast, free and open-ended dialogues between learners and interlocutors are possible if the conversation partner is either an AI-driven NPC or a real person.

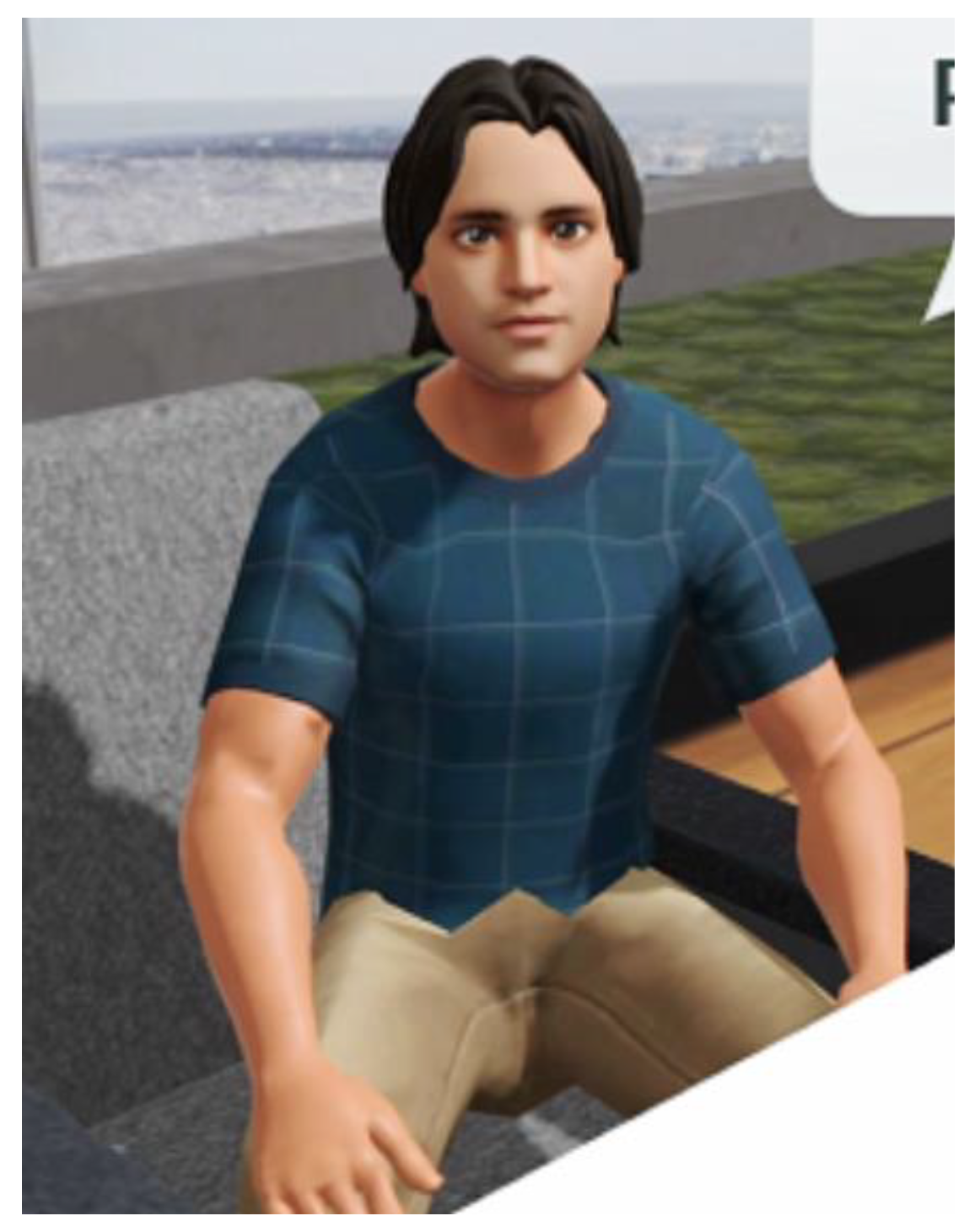

For example, in the

Talespin application (see

Figure 3), the learner´s communication with an NPC takes place within the framework of a pre-established script. The dialogue follows a path determined by researchers and/or practitioners in advance. Within this dialogue path, various responses to the NPC´s statements can be provided, which the learner must follow closely. Depending on the response, a predefined reaction is triggered (see also Section 4.9

Authoring Tool).

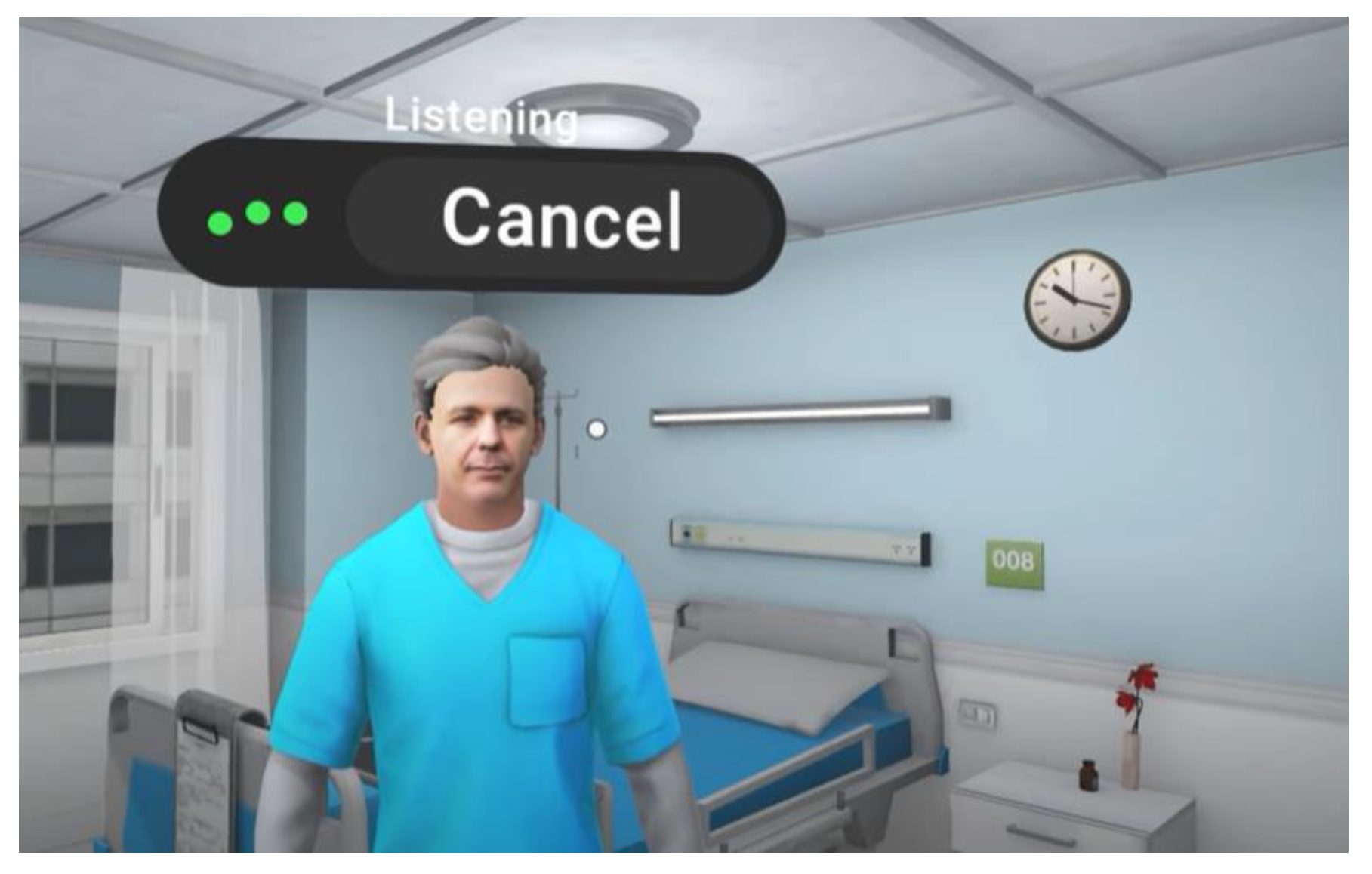

Applications such as

Bodyswaps (see

Figure 4) extend beyond the selection predefined response patterns, as seen in

Talespin. In these systems, learners engage with a preprogrammed NPC but can communicate more freely through AI-powered speech recognition. A further enhancement in NPC interaction occurs when the NPC is fully controlled by AI, as exemplified by

EngageVR (see

Figure 5).

Although EngageVR is primarily a SocialVR environment, their clients can design custom learning scenarios. In contrast to NPC dialogues, SocialVR applications enable interaction with one or more real individuals. VRChat, another SocialVR platform, facilitates interaction and communication between users across various digital environments, offering a more flexible and open form of communication compared to the other aforementioned approaches.

Table 1 reveals that many providers offer a combination of different communication styles. 60% of the software providers incorporate AI-powered communication options. Only two out of ten providers focus on scripted dialogues with an NPC. It is worth noting that, due to the rapid development of AI, this may change quickly depending on the provider.

4.4. Language of Communication

An important factor for VR social skill training is the language in which the training scenarios are available (see

Table 1). This criterion describes whether English, German, or other languages are supported for conducting various VR scenarios. VR platforms offered by British or American companies without SocialVR functionality tend to have more limited language availability. For instance,

Bodyswaps,

PIXOVR, and

Talespin provide numerous training scenarios available in English. Language customization is, according to the respective providers during sales discussions, possible for an additional fee. However, it remains unclear to what extent speech recognition and NPC speech output can be adjusted to user´s language. In contrast, if a provider, such as

WondaVR, utilizes AI in its VR application instead of pre-programmed NPCs, working with a backend Large Language Model, the range of available languages is significantly expanded. It should be noted that SocialVR applications, like

Virbela, have the advantage that no predefined language is required, as communication occurs between two or more real individuals.

4.5. Avatar

The section on

avatar (see

Table 2) describes, on the one hand, to what extent the avatars depicted in the VR application appear photorealistic or cartoonish. Photorealistic avatars are characterized by proportional body parts and a realistic depiction of the face and clothing. In contrast, cartoonish avatars may appear disproportionate in terms of physical stature and may look inauthentic due to features such as oversized eyes. On the other hand, this criterion also addresses whether the available avatars have a human or animal-like appearance. 60% of the providers, including

Polycular and

PIXOVR (see

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), offer photorealistic characters, while the remaining 40% use cartoonish figures, which can vary significantly in terms of their level of detail.

While

Virbela (see

Figure 8) features highly cartoonish characters, the figures from

3spin (see

Figure 9) or

WondaVR (see

Figure 10) seem to fall between the boundaries of cartoonish and photorealistic. Regardless of the avatar style offered by the provider, all software solutions provide the option to use human-like characters. Additionally,

VRChat allows users to utilize animal-like characters as well.

4.6. Avatar Creation

The criterion of

avatar creation examines in greater detail whether and to what extent an application allows users to create or modify avatars (see

Table 2). Three levels are distinguished: (1) not available, (2) selection of predefined avatars, and (3) modification of individual features. It is important to note that avatar creation is considered available only if it is integrated within the application itself, without requiring modifications or making an additional effort to implement it in the software.

While

Bodyswaps and

Mursion do not offer avatar creation, five providers, including

Polycular and

Talespin, provide a limited selection of predefined characters. In

Polycular, users can apply basic adjustments, such as selecting the gender of their counterpart. In contrast,

Talespin offers a more diverse range of options allowing users to choose not only between male and female characters but also to differentiate them by age, skin tone, and clothing style (see

Figure 11).

EngageVR,

Virbela and

WondaVR offer avatar creation, allowing users to modify more individual features. In

Virbela, users can only personalize their own character, whereas

EngageVR and

WondaVR also enable the creation of virtual counterparts. Consequently, the customization options vary significantly depending on the provider. In

Virbela, users have extensive customization options for their avatars. The avatar creation process is structured into five adjustable categories: (1) body, (2) hair, (3) face, (4) clothing, and (5) accessories (see

Figure 12). Within the

body category, users can modify both height and weight, as well as specific attributes such as hip width, chest size, abdominal shape, and muscle definition. Additionally, skin tone can be finely adjusted using a coordinate system, where the Y-axis ranges from cooler to warmer tones and the X-axis from darker to lighter shades. For

hair, users can choose from various hairstyles and colors. Facial hair can be added or removed, and eyebrows as well as eyelashes can be customized. The

face section allows for the selection of different head shapes, eye shapes and colors, nose structures, lip and mouth styles, ear shapes, and makeup options. Further refinements can be made using coordinate-based adjustment systems. Additionally, users are able to define the avatar´s apparent age.

Clothing customization follows a three-step process. Users can select from a variety of tops, pants or skirts, and shoes, with further options to modify individual garment colors. The available styles range from casual and sporty to formal and elegant. Finally, in the

accessories section, users can equip their avatar with various items, including hats, glasses, earrings, scarves, and belts, providing additional personalization options.

4.7. Contentlibrary

The criterion

Contentlibrary assesses whether the respective providers offer existing so-called

off-the-shelf content from which clients can select their training materials. Initially, a dichotomous distinction is made between availability and non-availability. In a subsequent step, exemplary content from selected providers is presented to give researchers and practitioners an initial overview of potential training scenarios (see

Table 2).

70% of providers offer a

Contentlibrary. Only

Virbela,

VRChat, and

WondaVR do not. Particularly in the cases of

Virbela and

WondaVR, the primary focus is on the creation of customized VR content (see 4.8).

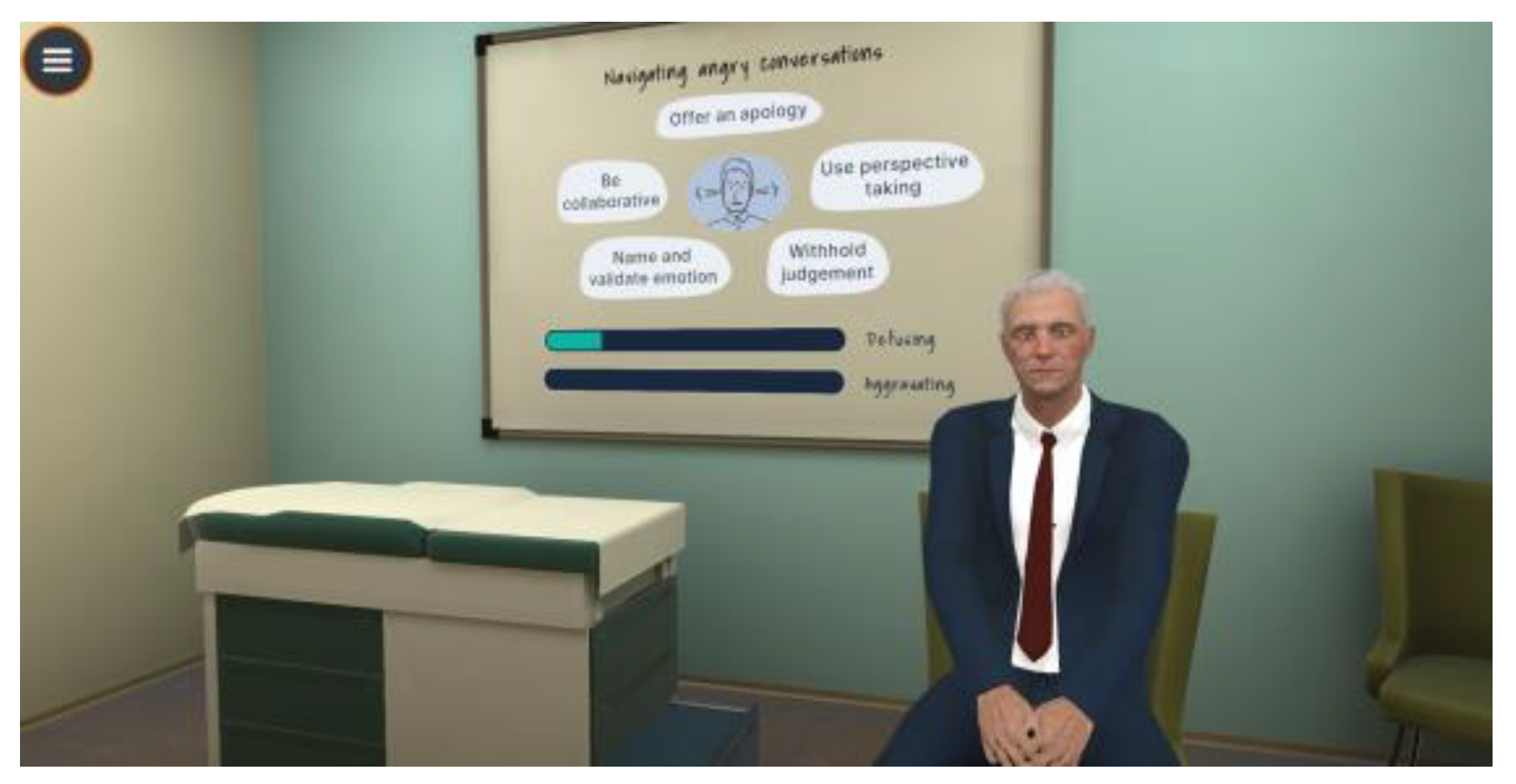

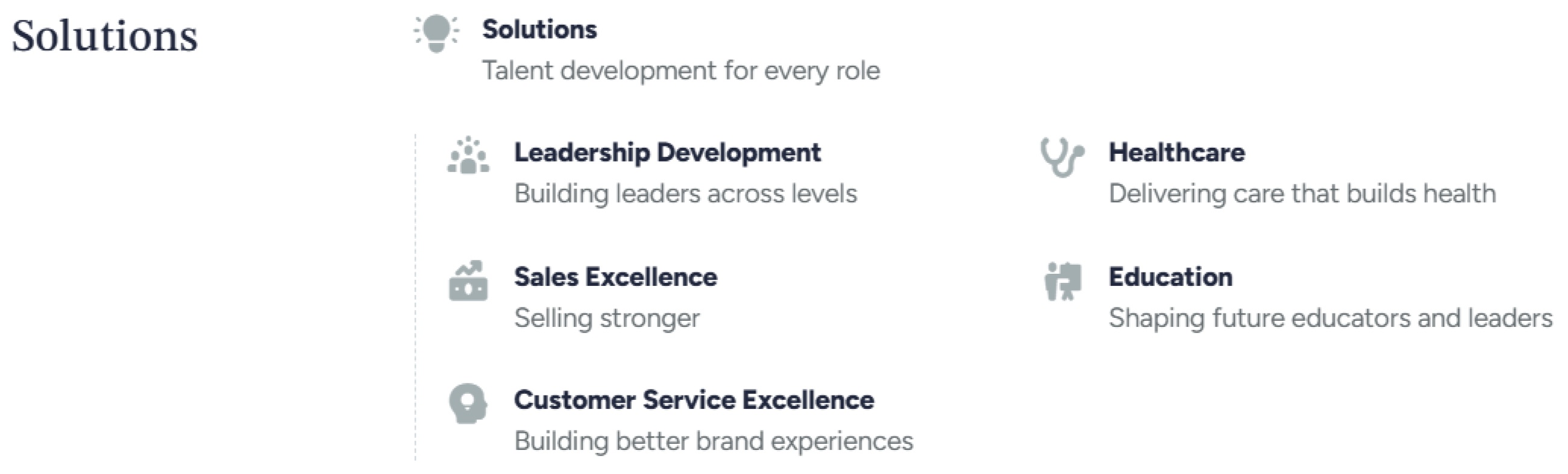

Mursion, for instance, provides VR trainings programs in

Leadership Development, Sales Excellence, and

Customer Service Excellence (see

Figure 13). The

Leadership Development program aims to teach individuals how to provide effective feedback and confidently adapt to various situations. Training participants are expected to develop the ability to connect with their teams to achieve better results. The

Sales Excellence training, in turn, offers users practical recommendations on sales techniques, coaching, and customer orientation. The

Customer Service Excellence module supports users in acquiring conflict resolution strategies and practicing empathetic communication.

Similarly,

3spin offers courses focused on enabling learners to conduct goal-oriented customer interactions. For example,

3spin provides a course on handling customer complaints, where participants learn to resolve customer issues competently. Additionally, the course

Understanding Costumer Needs teaches users to accurately identify customer needs and respond to them effectively. Moreover, through the VR training

Managing Stressful Situations, learners can develop strategies to find efficient solutions in high-pressure scenarios (see

Figure 14).

4.8. Authoringtool

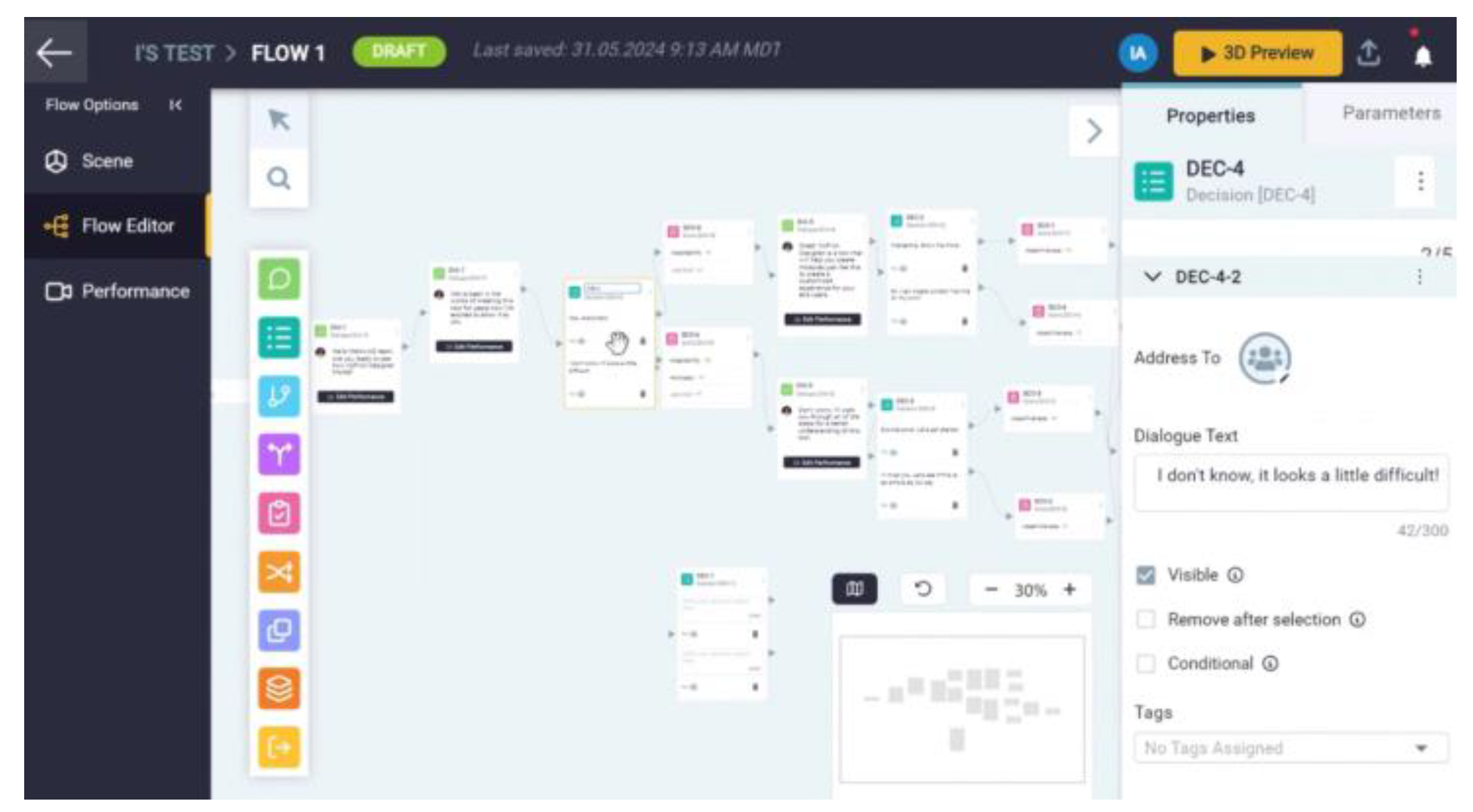

The final criterion we have identified is the availability of an

Authoringtool. In this context, an authoringtool refers to a feature integrated within the software that enables clients to independently modify existing VR content or create entirely new VR scenarios. A central aspect of our definition of an authoringtool is that researchers and practitioners should not require programming or design expertise to develop and customize content. In

VRChat, for example, it is possible to create content using

Unity and subsequently upload it to the software. In contrast, providers such as

Polycular and

Mursion, develop the desired VR scenarios themselves, without granting users the ability to modify the content independently. According to our definition, these three providers therefore do not have their own authoringtool.

Talespin serves as an example of how an integrated authoringtool can be designed. With this tool, clients can customize both the virtual environment and the avatars within it by selecting from various templates. Simple modifications, such as adjusting the seating position of avatars, are also possible. Beyond visual customization, clients can fully adapt their training scenarios to match their specific topics and instructional goals. It is also possible to create own dialogue paths. Within these paths, the dialogue between the NPC and the learner can be individually adjusted using response and reaction fields. It is important to note that the dialogue itself is not AI-driven but follows the predefined dialogue path. In addition to the design of training conversations, users can modify and adjust the facial expressions and gestures of virtual avatars, without requiring programming skills (see

Figure 15).

Similarly, WondaVR enables clients to personalize environments and avatars using templates and avatar creation tools. However, unlike Talespin, WondaVR allows for significantly more flexible and individualized training scenarios due to its AI-driven dialogue system.

In summary, seven of of ten providers offer an authoringtool. The degree of customization varies, ranging from simple modifications of the environment and dialogue to more complex adaptations and AI-driven scenarios (see

Table 2).

5. Discussion

The current state of VR in education is a rapidly evolving field, with new technologies and applications emerging regularly. Our article provides a snapshot of the current market landscape of VR providers in education, more precisely for the training in social skills. Therefore, we took a closer look at the providers based on ten key features. Our findings suggest that the market is characterized by a diverse range of providers, each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

One of the most striking aspects of our results is the even distribution of VR and SocialVR environments among the providers. This suggests that there are practical case studies for both, and that the choice between them will depend on the specific needs of the clients.

The analysis of technical requirements and communication features reveals that most providers offer a combination of different communication styles, including scripted dialogues, AI-powered communication, and interaction with real individuals. This suggests that the field is rapidly evolving, and that providers are continually adapting to new technologies and user needs.

Our results also highlight the importance of language customization in VR social skill training. While some providers offer limited language availability, others utilize AI-driven dialogue systems that can support a wide range of languages. This suggests that language customization is a critical factor in the development of effective VR training platforms.

The examination of avatar creation and customization reveals that most providers offer some level of customization, although the extent of customization varies widely. This proposes that avatar creation is an important aspect of VR social skill training, and that providers should prioritize the development of customizable avatars.

Finally, the results of our analysis highlight the importance of content libraries and authoring tools. While some providers offer extensive content libraries, others focus on the creation of industry-specific VR content. This suggests that the development of effective VR training platforms requires a balance between the provision of pre-existing content and the ability to create customized content.

However, it is essential to acknowledge the limitations of our article. Our focus on specific technologies and scenarios may not be representative of the broader VR market. Furthermore, our article does not contain a systematic review of the relevant literature, nor can we make realistic predictions beyond the year 2024.

The increasing use of AI in VR applications is a notable trend, with many providers already incorporating AI-powered tools into their platforms. Although AI-driven dialogues with NPCs are not yet available from every provider, AI functionalities are already being integrated to evaluate training sessions and provide users with feedback. It is likely that AI will become an even more integral part of VR in education soon, enabling more personalized and adaptive learning experiences.

In conclusion, our article aims to provide a starting point for researchers and practitioners. By offering a concise and accessible overview of the current state of VR providers in education, we hope to facilitate the process of selecting and implementing VR software, and to encourage to explore the many benefits of VR in education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Dominik Evangelou and Miriam Mulders; methodology, Dominik Evangelou and Miriam Mulders; formal analysis, Dominik Evangelou; investigation, Dominik Evangelou and Bünyamin Sekerci; writing: original draft preparation, Dominik Evangelou and Miriam Mulders; writing: review and editing, Dominik Evangelou, Miriam Mulders and Bünyamin Sekerci; visualization, Dominik Evangelou and Bünyamin Sekerci; project administration, Miriam Mulders. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Stiftung Innovation in der Hochschullehre (project name: VR-Hybrid, grant number: FR-124/2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hamilton, D.; McKechnie, J.; Edgerton, E.; Wilson, C. Immersive virtual reality as a pedagogical tool in education: a systematic literature review of quantitative learning outcomes and experimental design. Journal of Computers in Education 2020, 8, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, S.; Luxton-Reilly, A.; Wuensche, B.; Plimmer, B. A systematic review of Virtual Reality in education. Themes in Science & Technology Education 2017, 10, 85–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. M.; Rhiu, I.; Yun, M. H. A Systematic Review of a Virtual Reality System from the Perspective of User Experience. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 2019, 36, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M. C.; Gutworth, M. B. A meta-analysis of virtual reality training programs for social skill development. Computers & Education 2019, 144, 103707. [Google Scholar]

- Gillies, M.; Pan, X. Virtual reality for social skills training. VR/AR in Higher Education Conference; 2018; pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Dubiel, A.; Kamińska, D.; Zwoliński, G.; Ramić-Brkić, B.; Agostini, D.; Zancanaro, M. Virtual reality for the training of soft skills for professional education: trends and opportunities. Interactive Learning Environments 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makransky, G.; Petersen, G. B. The Cognitive Affective Model of Immersive Learning (CAMIL): a Theoretical Research-Based Model of Learning in Immersive Virtual Reality. Educational Psychology Review 2021, 33, 937–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulders, M.; Buchner, J.; Kerres, M. Virtual Reality in Vocational Training: A Study Demonstrating the Potential of a VR-based Vehicle Painting Simulator for Skills Acquisition in Apprenticeship Training. Technology, Knowledge and Learning 2022, 29, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mast, M. S.; Kleinlogel, E. P.; Tur, B.; Bachmann, M. The future of interpersonal skills development: Immersive virtual reality training with virtual humans. Human Resource Development Quarterly 2018, 29, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, N. J.; Schmidt, M. Usage Considerations of 3D Collaborative Virtual Learning Environments to Promote Development and Transfer of Knowledge and Skills for Individuals with Autism. Technology, Knowledge and Learning 2018, 25, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Gheisari, M. Using virtual reality to facilitate communication in the AEC domain: a systematic review. Construction Innovation 2020, 20, 509–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcañiz, M.; Parra, E.; Giglioli, I. A. C. Virtual Reality as an Emerging Methodology for Leadership Assessment and Training. Front Psychol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lok, B.; Ferdig, R. E.; Raij, A.; Johnson, K.; Dickerson, R.; Coutts, J.; Stevens, A.; Lind, D. S. Applying virtual reality in medical communication education: current findings and potential teaching and learning benefits of immersive virtual patients. Virtual Reality 2006, 10, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracq, M. S.; Michinov, E.; Jannin, P. Virtual Reality Simulation in Nontechnical Skills Training for Healthcare Professionals. A Systematic Review. Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare 2019, 14, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seufert, C.; Oberdörfer, S.; Roth, A.; Grafe, S.; Lugrin, J. L.; Latoschik, M. E. Classroom management competency enhancement for student teachers using a fuly immersive virtual classroom. Computers & Education 2021, 179, 104410. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S. Z.; Salehi, P.; Røed, R. K.; Halvorsen, P.; Baugerud, G. A.; Johnson, M. S.; Lison, P.; Riegler, M.; Lamb, M. E.; Griwodz, C.; Sabet, S.S. Towards an AI-driven talking avatar in virtual reality for investigative interviews of children. In GameSys’ 22 Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Games Systems; 2022; 1, pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rendevski, N.; Trajcevska, D.; Dimovski, M.; Veljanovski, K.; Popov, A.; Emini, N.; Veljanovski, D. PC VR vs Standalone VR Fully-Immersive Applications: History, Technical Aspects and Performance. 2022 57th International Scientific Conference on Information, Communication and Energy Systems and Technologies (ICEST), Ohrid North Macedonia, 16-18 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, P.; Kumar, R.; Tuteja, J.; Gupta, N. Systematic Review Of Virtual Reality & Its Challenges. 2021 Third International Conference on Intelligent Communication Technologies and Virtual Mobile Networks (ICICV), Tirunelveli India, 4-6 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, M.; Sanchez-Vives, M. V. Enhancing Our Lives with Immersive Virtual Reality. Front Robot. AI 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radianti, J.; Majchrzak, T. A.; Fromm, J.; Wohlgenannt, I. A Systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: Design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda. Computers & Education 2020, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, A.; Albus, P.; Seufert, T. Learning in Virtual Reality: Bridging the Motivation Gap by Adding Annotations. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqaddem, N. Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality in Education. Myth or Reality? International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET) 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, X.; Jiang, H.; Ding, Y. The effectiveness of virtual reality-based technology on anatomy teaching: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Medical Education 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulders, M. Vocational Training in Virtual Reality: A Case Study Using the 4C/ID Model. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S.; Ang, E.; Ng, E. D.; Yap, J.; Lau, L. S. T.; Chui, C. K. Communication skills training using virtual reality: A descriptive qualitative study. Nurse Education Today 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler-Schwartz, A.; Yilmaz, R.; Mirchi, N.; Bissonnette, V.; Ledwos, N.; Siyar, S.; Azarnoush, H.; Karlik, Bekir.; Maestro, R. D. Machine Learning Identification of Surgical and Operative Factors Associated With Surgical Expertise in Virtual Reality Simulation. Medical Education 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, R. J.; Cury, J.; Oliveira, L. C. N.; Srougi, M. Establishing the minimal number of virtual reality simulator training sessions necessary to develop basic laparoscopic skills competence: evaluation of the learning curve. International braz j urol 2013, 39, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- <b>28., </b>Amin.; Widiaty, I.; Yulia, C.; Abdullah, A. G. Amin.; Widiaty, I.; Yulia, C.; Abdullah, A. G. The Application of Virtual Reality (VR) in Vocational Education A Systematic Review. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 2022, 651, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Thomann, H.; Zimmermann, J.; Deutscher, V. How effective is immersive VR for vocational education? Analyzing knowledge gains and motivational effects. Computers & Education 2024, 220. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Taranilla, R.; Tirado-Olivares, S.; Cózar-Gutiérrez, R.; González-Calero, J. A. Effects of virtual reality on learning outcomes in K-6 education: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review 2022, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellas, N.; Dengel, A.; Christopoulos, A. A Scoping Review of Immersive Virtual Reality in STEM Education. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies 2020, 13, 748–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parong, J.; Mayer, R. E. Cognitive and affective processes for learning science in immersive virtual reality. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 2020, 37, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulders, M.; Träg, K. H.; Kirner, L. Go green: evaluating an XR application on biodiversity in German secondary school classrooms. Instructional Science 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, C. P.; Rathner, J. A.; Fong, A. Y.; Sevigny, C. P. Virtual Reality in Higher Education. International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education 2019, 27, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhieb, O.; Durado, A. Creating VR Content for Training Purposes. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science 2024, 8, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiefelbauer, C.; Ghoneim, A.; Oberhuemer, P.; Vettori, O. Verschränkte Lernwelten: physisch, virtuell, seamless. Zeitschrift für Hochschulentwicklung 2023, 18, 159–179. [Google Scholar]

- McVeigh-Schultz, J.; Segura, E. M.; Merrill, N.; Isbister, K. What’s It Mean to “Be Social” in VR? Mapping the Social VR Design Ecology. In 2018 DIS´18 Companion: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Conference Companion Publication on Designing Interactive Systems, Hong Kong China, 9-13 June 2018; pp. 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Zdunek, A.; Bachmann, M. Wie wirkt Virtual Reality? impuls: Magazin des Departements Soziale Arbeit 2023, 2, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Warpefelt, H. The Non-Player Character: Exploring the believability of NPC presentation and hehavior. Doctoral thesis, Stockholm University, Stockholm, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Neundlinger, K.; Frankus, E.; Häufler, I.; Layer-Wagner, T.; Kriglstein, S.; Schrank, B. »Virtual Skills Lab« - Transdisziplinäres Forschen zur Vermittlung sozialer Kompetenzen im digitalen Wandel; transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).