Submitted:

26 February 2025

Posted:

28 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

As the discussions on sixth generation (6G) wireless networks progress at a rapid pace, various approaches have emerged over the last years regarding new architectural concepts that can support the 6G vision. Therefore, the goal of this work is to highlight the most important technological efforts in relation to the definition of a 6G architectural concept. To this end, the primary challenges are firstly described, which can be viewed as the driving forces for the 6G architectural standardization. Afterwards, novel technological approaches are discussed to support the 6G concept, such as the introduction of artificial intelligence and machine learning for resource optimization and threat mitigation, cell-free deployments and novel physical layer techniques to leverage high data rates, open access protocols for flexible resource integration, security and privacy protection in the 6G era, as well as the digital twin concept. Finally, recent research efforts are analyzed with emphasis on the combination of the aforementioned aspects towards a unified 6G architectural approach. To this end, limitations and open issues are highlighted as well.

Keywords:

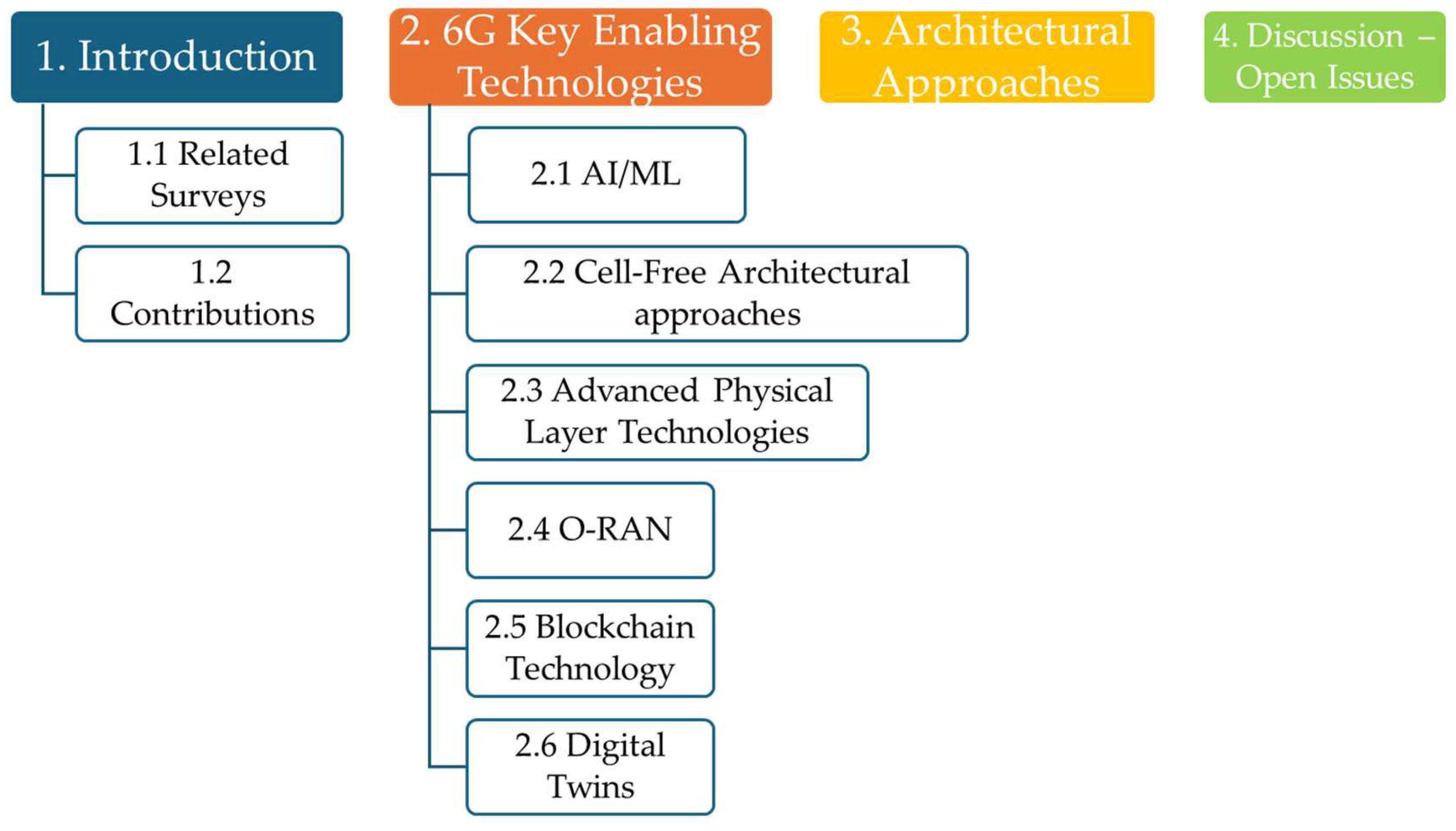

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Surveys

1.2. Contributions

- Integration of various technologies and key factors towards 6G architectural design.

- Discussion on the current trends of 6G architectural design, based on the presented works. To this end, the most important driving factors are also highlighted.

- Identification of limitations that should also be considered in the design and deployment of 6G networks.

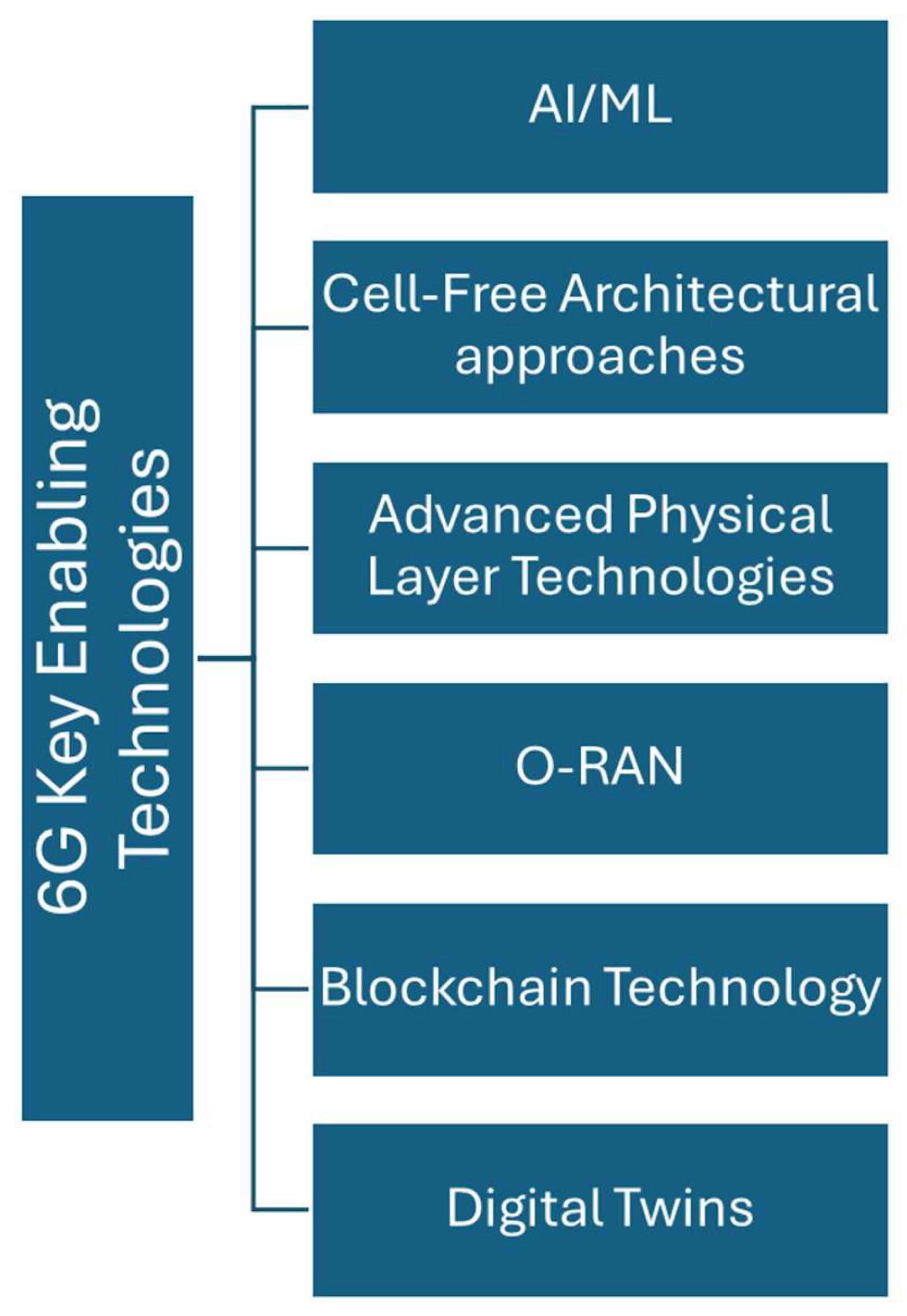

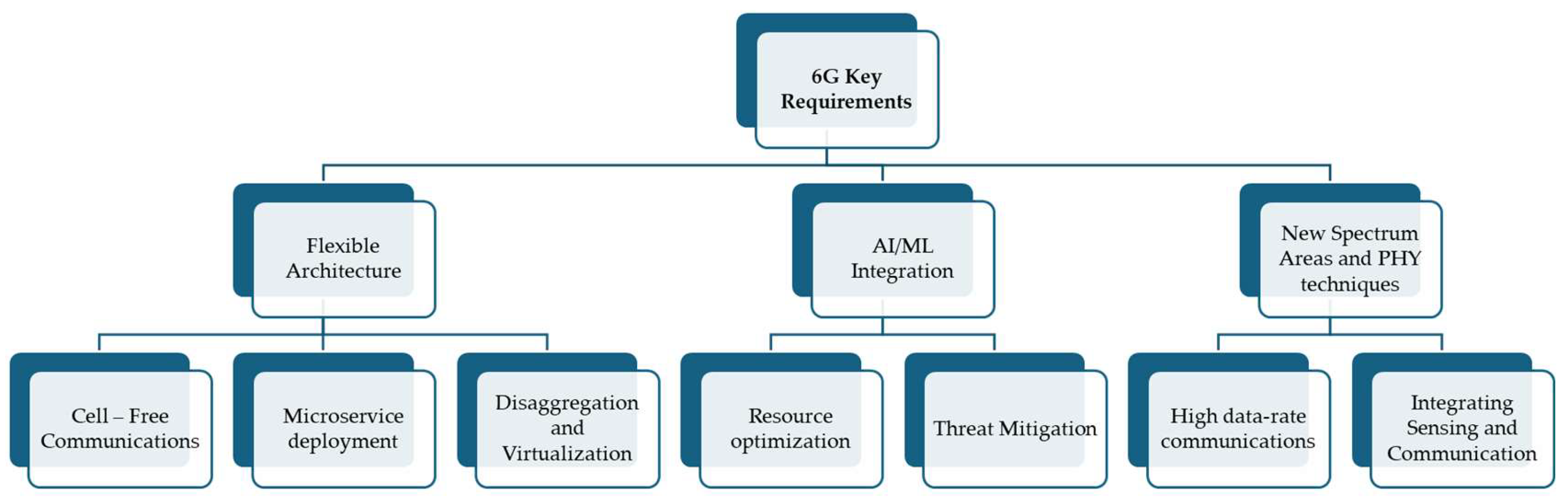

2. 6G Key Enabling Technologies

2.1. AI/ML

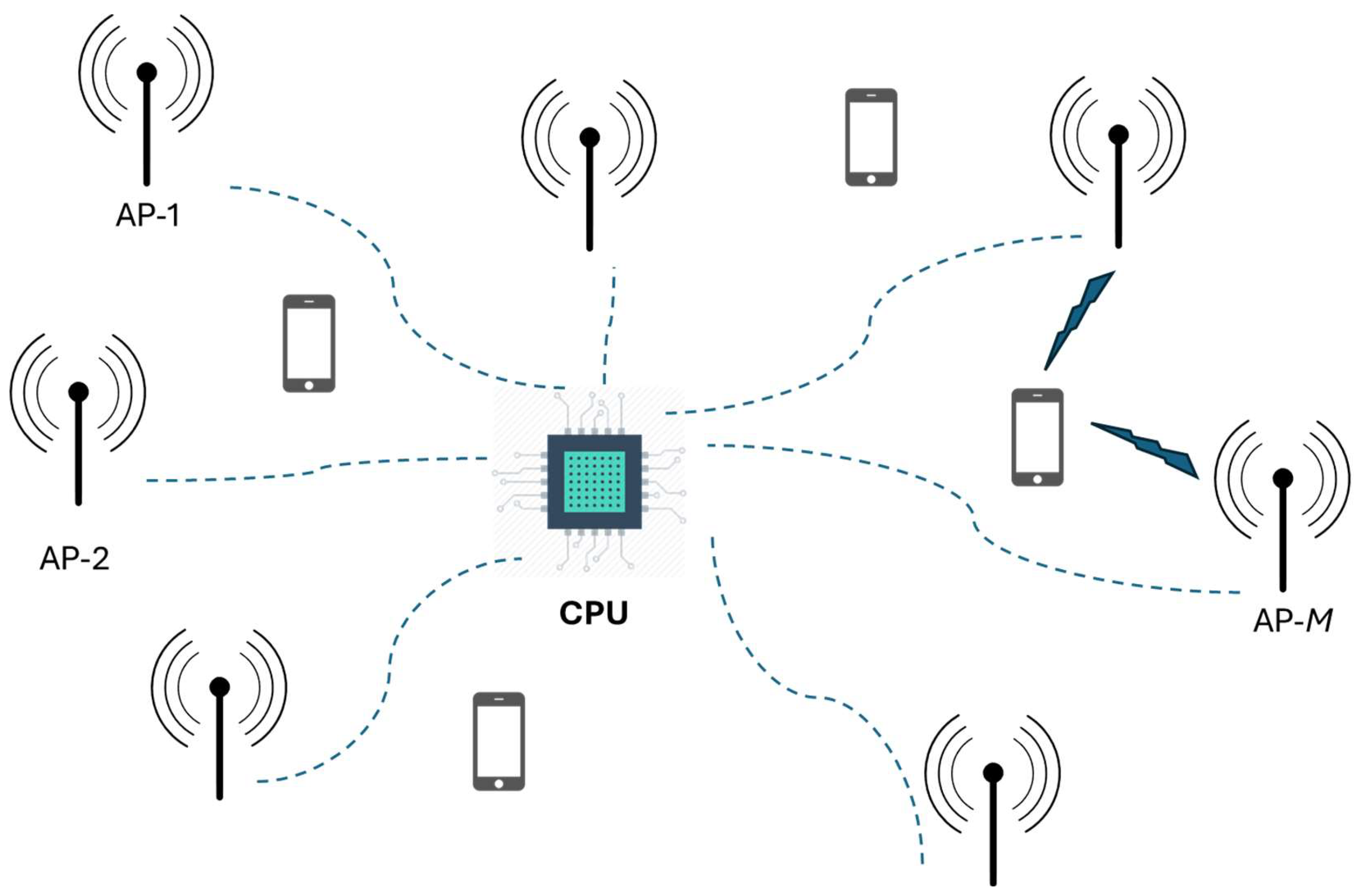

2.2. Cell-Free Architectural approaches

2.3. Advanced Physical Layer Technologies

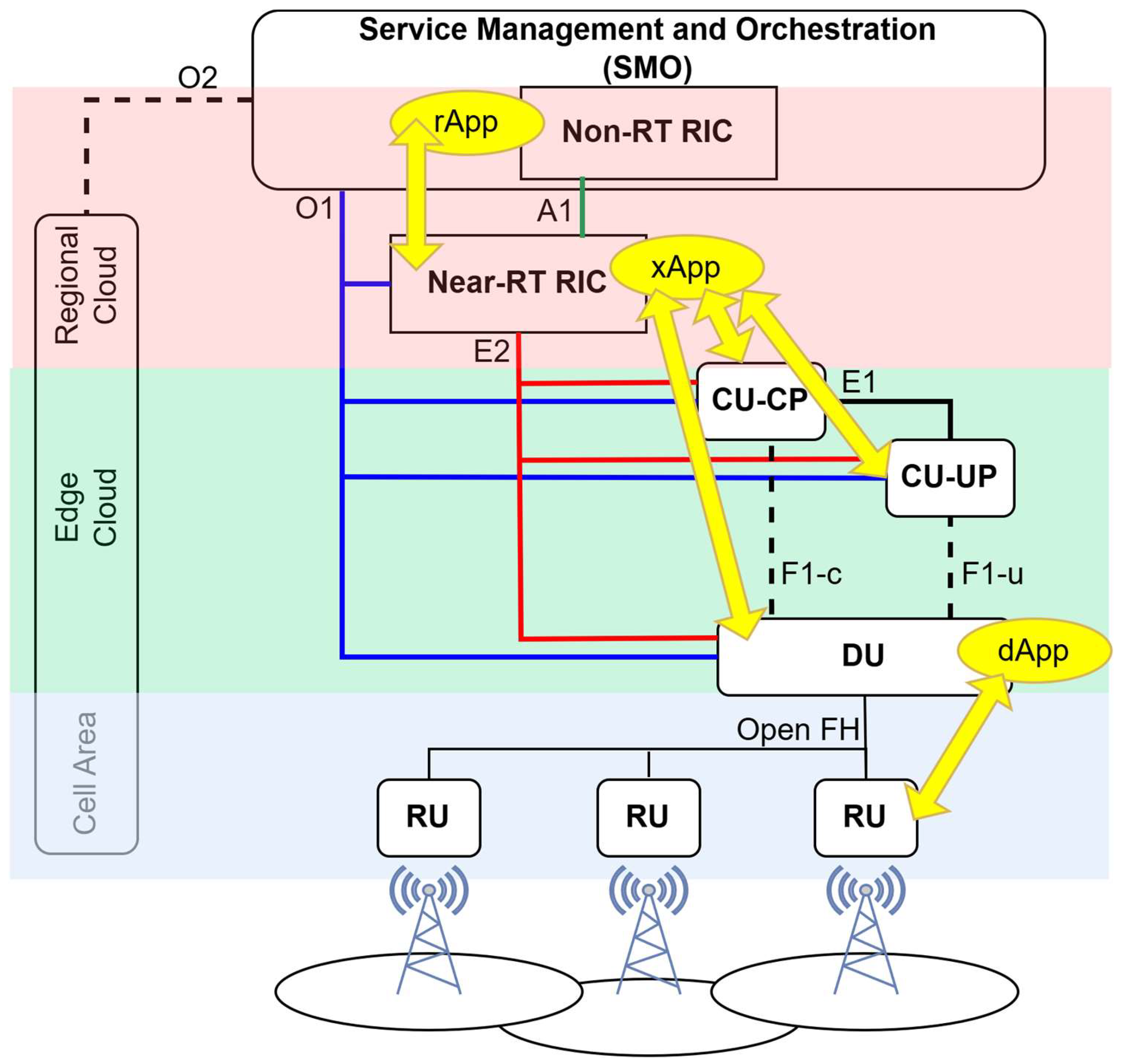

2.4. O-RAN

2.4. Blockchain technology

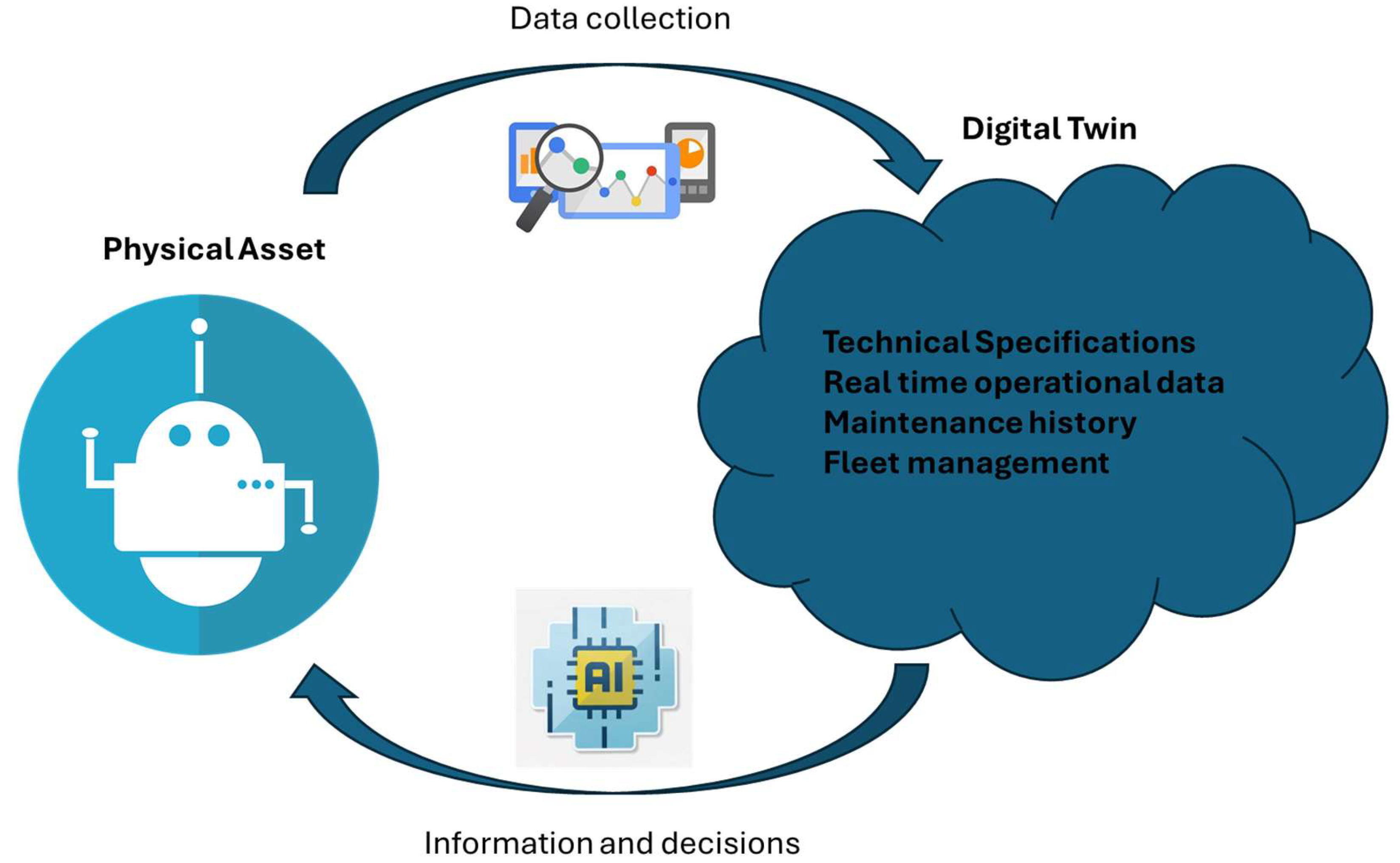

3.5. Digital Twins

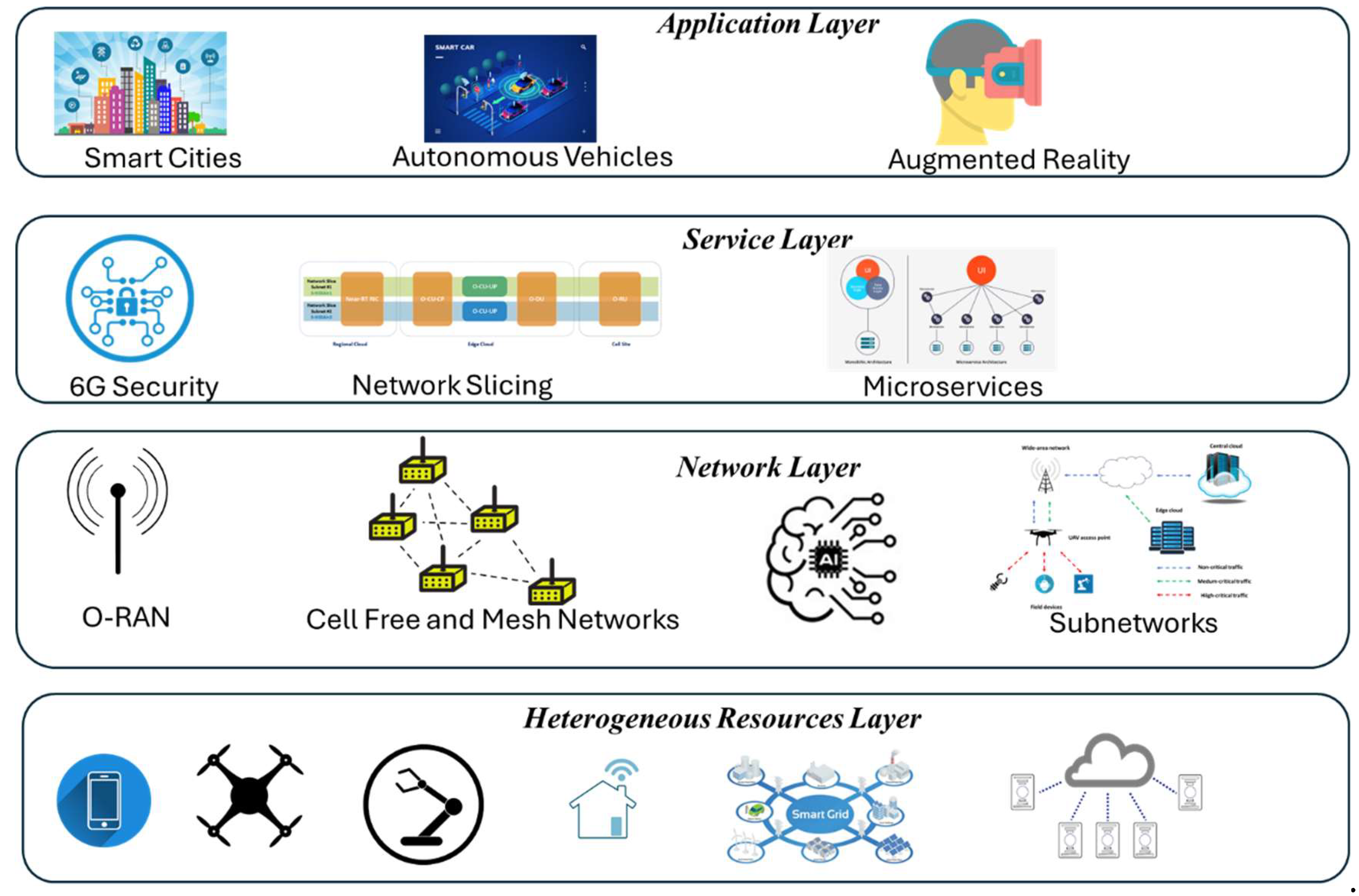

3. Architectural approaches

4. Discussion – Open Issues

- Deployment capabilities and costs throughout large geographical areas. To this end, the support of ultra-high data rates with minimum latency necessitates dense deployments that may increase the cost of 6G infrastructures.

- In the same context, the 6G approach should be also adopted by lightweight devices that will have the capability to run light versions of the 6G architecture.

- Although ML models are a key innovation approach in 5G/6G networks, many times improved model performance is accompanied by increased model complexity. In this context, a key innovation over the last years is the concept of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI), a field that is concerned with the development of new methods that explain and interpret ML models [75,76]. The main focus is on the reasoning behind the decisions or predictions made by the AI algorithms, to make them more understandable and transparent. Therefore, XAI assists in making ML models lead to decisions that are not based on irrelevant or otherwise unfair criteria.

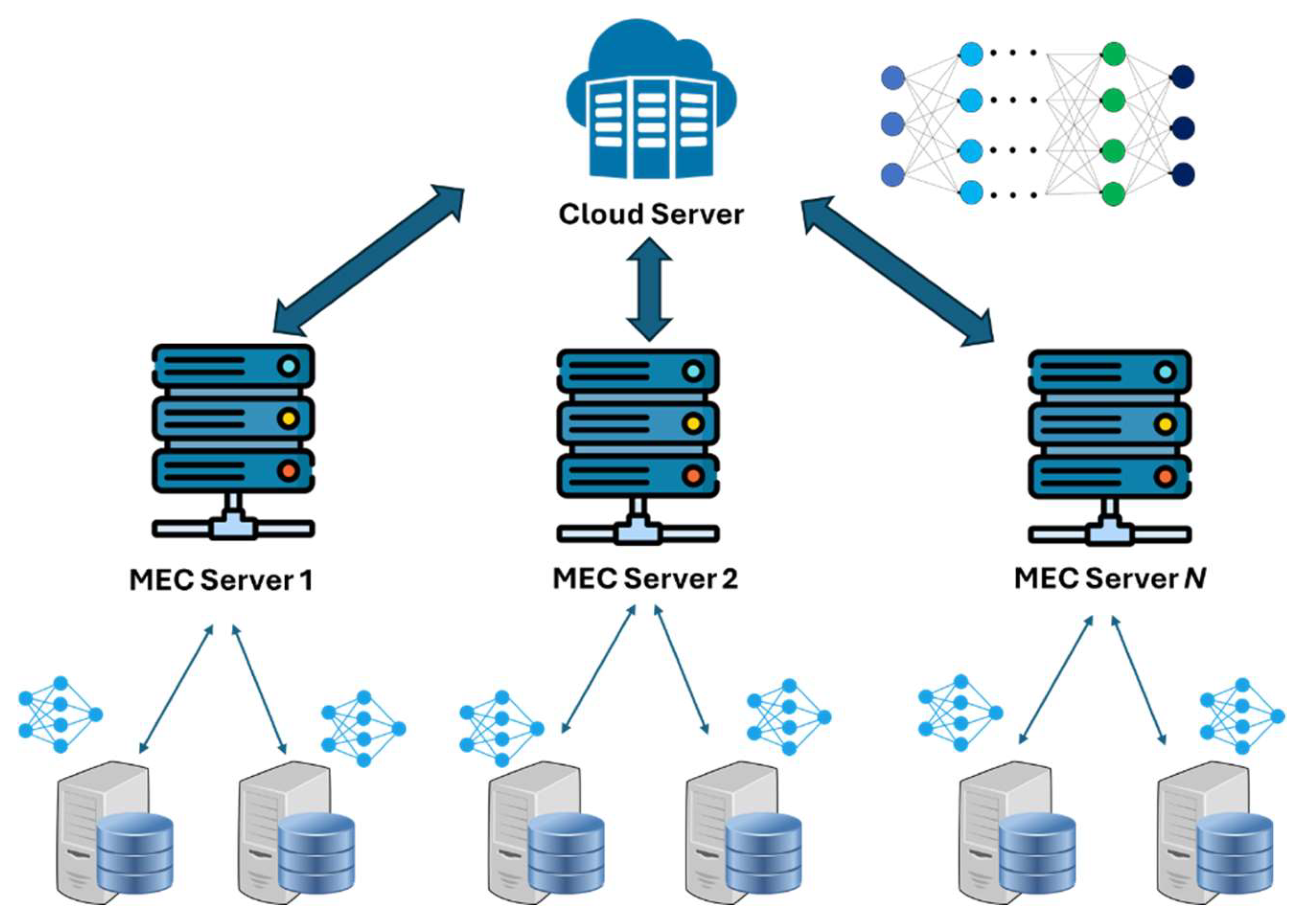

- Integration of various cutting-edge technologies. As discussed thoroughly in this article, a key concept in 6G networks will be the integration of various technologies, both in the physical and network layer. Hence, a challenging issue would be to limit overall complexity and signaling burden. For example, since 6G networks involve the collection of a vast amount of data, appropriate processing algorithms are required that can effectively manage this volume. Moreover, as also stated in this article, security by design is a prerequisite for all 6G deployments. In this new landscape, lightweight IoT devices do not have high storage or processing capabilities. In addition, as also stated in this article, data collection on single servers might result in a single point of failure. Therefore, over the last years decentralized approaches for data collection, storage and processing have been studied, such as IoT-edge-cloud architectures. To this end, MEC servers are deployed near the IoT devices that have the capability to store and process complex data and tasks. Hence, IoT devices offload certain tasks to the MEC servers. In parallel, MEC servers can offload additional tasks to cloud servers, especially in cases where huge amounts of data volumes are processed [77].

- Coexistence with previous generations of networks. As also anticipated in the 5G era, the full transition to a new generation of networks will gradually take place. Until then, coexistence with well-established protocols is of utmost importance. In this case, one solution that has been proposed is the one in [69], where nested networks are formulated. In this context, small 6G cells can be deployed in areas with increased traffic distribution, that can communicate with large 5G cells. However, there are not many works in literature that on one hand deal with the coexistence of 5G/6G and associated issues (e.g., handover and mobility management, resource allocation, etc.) and on the other hand with interference mitigation mechanisms. To this end, the work in [78] presents an interference analysis for the coexistence of terrestrial networks with satellite services. In this work, extensive simulations have been carried out regarding cellular coexistence with low earth orbit (LEO) satellites in the 47.2-50.2 GHz band.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3GPP | Third Generation Partnership Project |

| 5G | Fifth Generation |

| 6G | Sixth Generation |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AP | Access Point |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| BS | Base Station |

| CGC | City Gateway Cloud |

| CN | Core Network |

| CU | Centralized Unit |

| CP | Control Plane |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| CRAN | Cloud RAN |

| D2D | Device to Device |

| DAS | Distributed Antenna System |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DLT | Distributed Ledger Technology |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| eMBB | Enhanced Mobile Broadband |

| FH | Front Haul |

| FL | Federated Learning |

| FSO | Free Space Optical |

| IBI | Intent Based Interface |

| IBN | Intent-Based Networking |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IRS | Intelligent Reflecting Surface |

| ISAC | Integrated Sensing and Communication |

| JSAC | Joint Sensing and Communication |

| LEO | Low Earth Orbit |

| M2M | Machine to Machine |

| MEC | Multi-access Edge Computing |

| MIMO | Multiple Input Multiple Output |

| mMIMO | Massive MIMO |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| mMTC | Massive Machine Type Communications |

| mmWave | Millimeter Wave |

| MS | Mobile Station |

| NF | Network Function |

| NFV | Network Function Virtualization |

| NN | Neural Network |

| NOMA | Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access |

| O-RAN | Open Radio Access Network |

| PQC | Post Quantum Cryptography |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| RAN | Radio Access Network |

| RIC | RAN Intelligent Controller |

| RIS | Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RU | Radio Unit |

| RUPA | Recursive User Plane Architecture |

| SBA | Service Based Architecture |

| SDN | Software Defined Networking |

| SMO | Service Management and Orchestration |

| SSC | Smart Sustainable City |

| THz | Terahertz |

| UDN | Ultra Dense Networks |

| URLLC | Ultra Reliable Low Latency Communications |

| UP | User Plane |

| VANET | Vehicular Ad Hoc Network |

| V2X | Vehicle to Everything |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Popovski, P.; Trillingsgaard, K. F.; Simeone, O.; Durisi, G. 5G Wireless Network Slicing for eMBB, URLLC, and mMTC: A Communication-Theoretic View. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 55765–55779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B. S.; Jangsher, S.; Ahmed, A.; Al-Dweik, A. URLLC and eMBB in 5G Industrial IoT: A Survey. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2022, 3, 1134–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, U.; Ali, M.F.; Rajkumar, S.; Jayakody, D.N.K. Sensing and Secure NOMA-Assisted mMTC Wireless Networks. Electronics 2023, 12, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, J.; Chung, H.; Hong, J.; Seo, H.; Choi, J.; Kim, S. Millimeter-Wave Communications: Recent Developments and Challenges of Hardware and Beam Management Algorithms. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2021, 59, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. M. Massive MIMO for Massive Industrial Internet of Things Networks: Operation, Performance, and Challenges. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive Communications and Networking 2024, 10, 2119–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundokun, R.O.; Awotunde, J.B.; Imoize, A.L.; Li, C.-T.; Abdulahi, A.T.; Adelodun, A.B.; Sur, S.N.; Lee, C.-C. Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access Enabled Mobile Edge Computing in 6G Communications: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adoga, H.U.; Pezaros, D.P. Network Function Virtualization and Service Function Chaining Frameworks: A Comprehensive Review of Requirements, Objectives, Implementations, and Open Research Challenges. Future Internet 2022, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Shah, N.; Amin, R.; Alshamrani, S.S.; Alotaibi, A.; Raza, S.M. Software-Defined Networking: Categories, Analysis, and Future Directions. Sensors 2022, 22, 5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieba, M.; Natkaniec, M.; Borylo, P. Cloud-Enabled Deployment of 5G Core Network with Analytics Features. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoynov, V.; Poulkov, V.; Valkova-Jarvis, Z.; Iliev, G.; Koleva, P. Ultra-Dense Networks: Taxonomy and Key Performance Indicators. Symmetry 2023, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, M.; Valenzuela, E.; Rodríguez, B.; Nolazco-Flores, J.A.; Del-Valle-Soto, C. Utilization of 5G Technologies in IoT Applications: Current Limitations by Interference and Network Optimization Difficulties—A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkagkas, G.; Vergados, D.J.; Michalas, A.; Dossis, M. The Advantage of the 5G Network for Enhancing the Internet of Things and the Evolution of the 6G Network. Sensors 2024, 24, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordani, M.; Polese, M.; Mezzavilla, M.; Rangan, S.; Zorzi, M. Toward 6G Networks: Use Cases and Technologies. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2020, 58, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiky, M.N.A.; Rahman, M.E.; Uzzal, M.S.; Kabir, H.M.D. A Comprehensive Exploration of 6G Wireless Communication Technologies. Computers 2025, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, S.; Anand, S.; Buchke, S.; Agnihotri, K. A Review of Recent Developments in 6G Communications Systems. Eng. Proc. 2023, 59, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dala Pegorara Souto, V.; Dester, P.S.; Soares Pereira Facina, M.; Gomes Silva, D.; de Figueiredo, F.A.P.; Rodrigues de Lima Tejerina, G.; Silveira Santos Filho, J.C.; Silveira Ferreira, J.; Mendes, L.L.; Souza, R.D.; et al. Emerging MIMO Technologies for 6G Networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, G.; Zheng, G.; I, C. -L.; You, X.; Hanzo, L. Open-Source Multi-Access Edge Computing for 6G: Opportunities and Challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 158426–158439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leivadeas, A.; Falkner, M. A Survey on Intent-Based Networking. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; et al. Service-oriented Architecture Evolution towards 6G Networks. IEEE Conference on Standards for Communications and Networking, 2023; -14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfanian, J.; Lister, D.; Zhao, Q.; Wikström, G.; Chen, Y. 6G Vision & Analysis of Potential Use Cases. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 61, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkonis, P. K; Lavdas, S.; Vardoulias, G.; Trakadas, P.; Sarakis, L.; Papadopoulos, K. System Level Performance Assessment of Large-Scale Cell-Free Massive MIMO Orientations with Cooperative Beamforming. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 92073–92086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub Khan, A.; et al. ORAN-B5G: A Next-Generation Open Radio Access Network Architecture with Machine Learning for Beyond 5G in Industrial 5.0. IEEE Transactions on Green Communications and Networking 2024, 8, 1026–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corici, M.-I.; et al. Organic 6G Networks: Vision, Requirements, and Research Approaches. IEEE Access, 7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehelwala, J.; Siriwardhana, Y.; Hewa, T.; Liyanage, M.; Ylianttila, M. Decentralized Learning for 6G Security: Open Issues and Future Directions. Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscinelli, E.; Shinde, S.S.; Tarchi, D. Overview of Distributed Machine Learning Techniques for 6G Networks. Algorithms 2022, 15, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomikos, N.; Xylouris, G.; Patsourakis, G.; Nikolakakis, V.; Giannopoulos, A.; Mandilaris, C.; Gkonis, P.; Skianis, C.; Trakadas, P. A Distributed Trustable Framework for AI-Aided Anomaly Detection. Electronics 2025, 14, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.F.; Kadhim, D.J. Towards 6G Technology: Insights into Resource Management for Cloud RAN Deployment. IoT 2024, 5, 409–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, I.; Kotlarz, P.; Dorożyński, J.; Mikołajewski, D. Sixth-Generation (6G) Networks for Improved Machine-to-Machine (M2M) Communication in Industry 4.0. Electronics 2024, 13, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; et al. Terahertz Communications and Sensing for 6G and Beyond: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chataut, R.; Nankya, M.; Akl, R. 6G Networks and the AI Revolution—Exploring Technologies, Applications, and Emerging Challenges. Sensors 2024, 24, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. A Survey on Intelligence-Endogenous Network: Architecture and Technologies for Future 6G. Intelligent and Converged Networks 2024, 5, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos, A.; Spantideas, S.; Kapsalis, N.; Karkazis, P.; Trakadas, P. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Energy-Efficient Multi-Channel Transmissions in 5G Cognitive HetNets: Centralized, Decentralized and Transfer Learning Based Solutions. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 129358–129374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeogun, R.; Berardinelli, G. Multi-Agent Dynamic Resource Allocation in 6G in-X Subnetworks with Limited Sensing Information. Sensors 2022, 22, 5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberti, F.; Berardi, D.; Martini, B. Federated Learning in Dynamic and Heterogeneous Environments: Advantages, Performances, and Privacy Problems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, J.; Castanheira, D.; Silva, A.; Dinis, R.; Gameiro, A. A Review on Cell-Free Massive MIMO Systems. Electronics 2023, 12, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsiokas, I. A.; Gkonis, P. K.; Kaklamani, D. I.; Venieris, I. S. A DL-Enabled Relay Node Placement and Selection Framework in Multicellular Networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 65153–65169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhad, A.; Pyun, J.-Y. Terahertz Meets AI: The State of the Art. Sensors 2023, 23, 5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannopoulos, A.; et al. , Supporting Intelligence in Disaggregated Open Radio Access Networks: Architectural Principles, AI/ML Workflow, and Use Cases. IEEE Access, 3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAN AI/ML Workflow Description and Requirements Version—01.01, O-RAN Alliance, Alfter, Germany, 2020.

- RAN Near-Real-Time RAN Intelligent Controller Architecture & E2 General Aspects and Principles—V1.01, O-RAN Working Group 3, Alfter, Germany, 2020.

- Pajooh, H.H.; Demidenko, S.; Aslam, S.; Harris, M. Blockchain and 6G-Enabled IoT. Inventions 2022, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Guo, J.; Gao, N.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, S.; Li, X. A Survey of Blockchain and Artificial Intelligence for 6G Wireless Communications. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Xu, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; You, X. Wireless Network Digital Twin for 6G: Generative AI as a Key Enabler. IEEE Wireless Communications 2024, 31, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Xie, W.; Liu, L.; Hong, T.; Zhou, F. UAV Digital Twin Based Wireless Channel Modeling for 6G Green IoT. Drones 2023, 7, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardinelli, G.; Mogensen, P.; Adeogun, R.O. 6G subnetworks for Life-Critical Communication. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd 6G Wireless Summit (6G SUMMIT), Levi, Finland, 17–20 March 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Shan, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Hung, K.; Wu, Y.; Quek, T. Q. S. A Distributed Microservice-Aware Paradigm for 6G: Challenges, Principles, and Research Opportunities. IEEE Network 2024, 38, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corici, M.; Troudt, E.; Magedanz, T. An Organic 6G Core Network Architecture. ICIN, 2022; -7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granelli, F.; Qaisi, M.; Kapsalis, P.; Gkonis, P.; Nomikos, N.; Zacarias, I.; Jukan, A.; Trakadas, P. AI/ML-Assisted Threat Detection and Mitigation in 6G Networks with Digital Twins: The HORSE Approach. IEEE 29th International Workshop on Computer Aided Modeling and Design of Communication Links and Networks (CAMAD) 2024, Athens, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Tripi, G.; Iacobelli, A.; Rinieri, L.; Prandini, M. Security and Trust in the 6G Era: Risks and Mitigations. Electronics 2024, 13, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwakeel, A.M.; Alnaim, A.K. Network Slicing in 6G: A Strategic Framework for IoT in Smart Cities. Sensors 2024, 24, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Q.; Chen, P. 6G Cell-Free Network Architecture. IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electronic Technology, Communication and Information, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, P.; et al. , Towards 6G Communications: Architecture, Challenges, and Future Directions. 12th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT) 2021, India, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese, M.; et al. Empowering the 6G Cellular Architecture with Open RAN. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2024, 42, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Sun, W.; Xu, H. A Native Intelligent and Security 6G Network Architecture. IEEE/CIC International Conference on Communications in China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X. D.; et al. 6G Architecture Design: from Overall, Logical and Networking Perspective. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 61, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzarri, A.; Mazzenga, F. 6G Use Cases and Scenarios: A Comparison Analysis Between ITU and Other Initiatives. Future Internet 2024, 16, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, C.; He, J.; Shi, N.; Zhang, T.; Pan, X. 6G Network Architecture Based on Digital Twin: Modeling, Evaluation, and Optimization. IEEE Network 2024, 38, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Antón, S.; Grasa, E.; Perelló, J.; Cárdenas, A. 6G-RUPA: A Flexible, Scalable, and Energy-Efficient User Plane Architecture for Next-Generation Mobile Networks. Computers 2024, 13, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Wu, J.; Tong, W.; Zhu, P.; Chen, Y. 6G Network Architecture Vision. Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, M.; et al. 6G Architectural Trends and Enablers. IEEE 4th 5G World Forum (5GWF) 2021, Canada, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Hu, Z.; Lin, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Chen, J. Architecture for Self-Evolution of 6G Core Network Based on Intelligent Decision Making. Electronics 2023, 12, 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Luo, J.; Su, X. The Framework of 6G Self-Evolving Networks and the Decision-Making Scheme for Massive IoT. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, V.; Viswanathan, H.; Flinck, H.; Hoffmann, M.; Räisänen, V.; Hätönen, K. 6G Architecture to Connect the Worlds. IEEE Access, 1735; -20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; et al. A Secure and Resilient 6G Architecture Vision of the German Flagship Project 6G-ANNA. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 102643–102660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Pottoo, S.N.; Armghan, A.; Aliqab, K.; Alsharari, M.; Abd El-Mottaleb, S.A. 6G Network Architecture Using FSO-PDM/PV-OCDMA System with Weather Performance Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M. A.; et al. Toward an Open, Intelligent, and End-to-End Architectural Framework for Network Slicing in 6G Communication Systems. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2023, 4, 1615–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Kim, G.; Shim, S.; Jang, S.; Song, J.; Lee, B. Key Technologies for 6G-Enabled Smart Sustainable City. Electronics 2024, 13, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Popli, R.; Singh, S.; Chhabra, G.; Saini, G.S.; Singh, M.; Sandhu, A.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, R. The Role of 6G Technologies in Advancing Smart City Applications: Opportunities and Challenges. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Nadir, R.M.; Rustam, F.; Hur, S.; Park, Y.; Ashraf, I. Nested Bee Hive: A Conceptual Multilayer Architecture for 6G in Futuristic Sustainable Smart Cities. Sensors 2022, 22, 5950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgul, O. U.; et al. Discussion on 6G Architecture Evolution: Challenges and Emerging Technology Trends. Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi, P.; Contreras-Murillo, L. M.; Menéndez, D. R.; Giardina, P.; De la Oliva, A. 6G Architecture for Enabling Predictable, Reliable and Deterministic Networks: the PREDICT6G Case. IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serôdio, C.; Cunha, J.; Candela, G.; Rodriguez, S.; Sousa, X.R.; Branco, F. The 6G Ecosystem as Support for IoE and Private Networks: Vision, Requirements, and Challenges. Future Internet 2023, 15, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Network Data Analytics Services; Release 15, Standard ETSI TS 129 520, 3GPP, 2019.

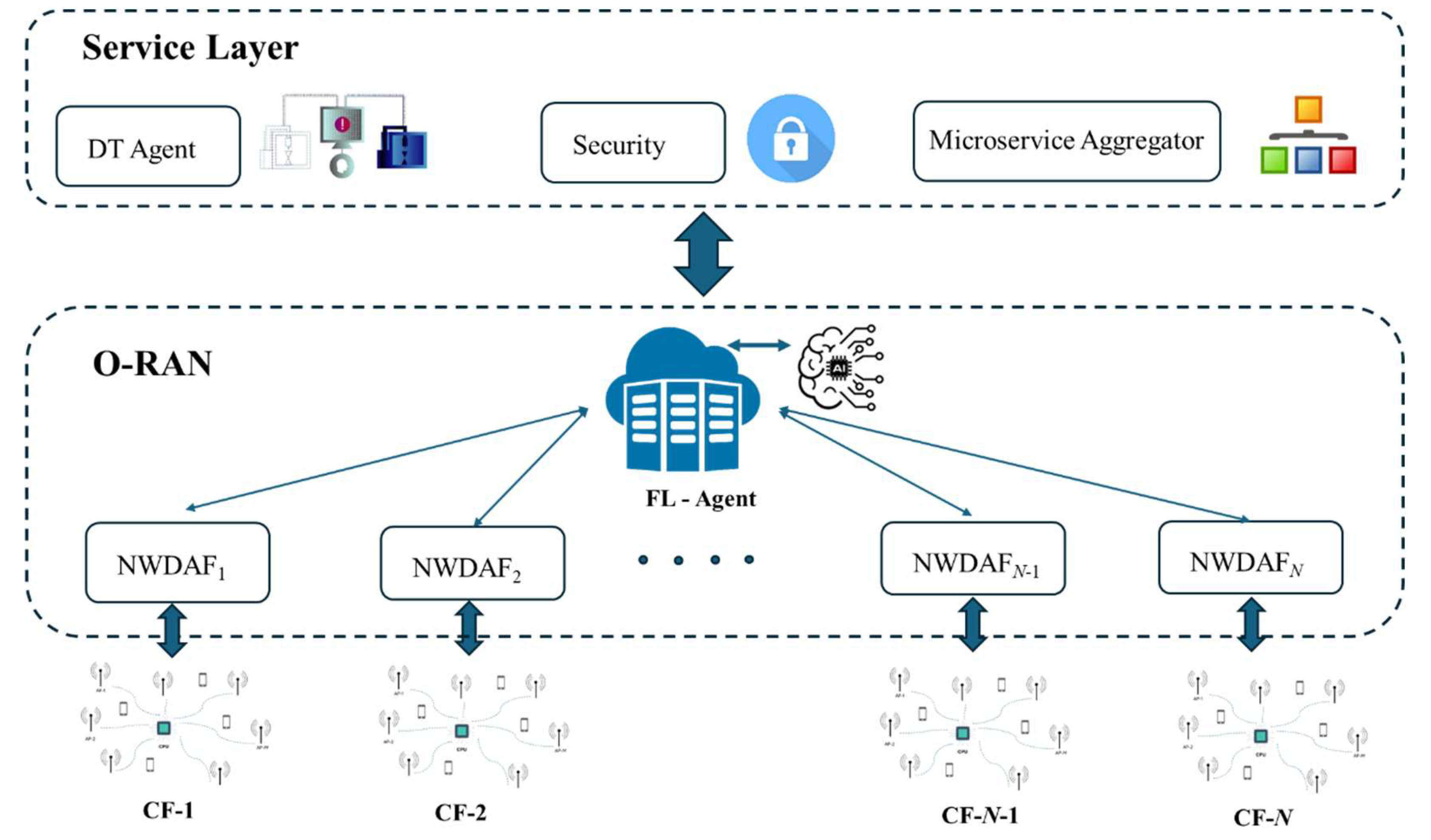

- Gkonis, P. K.; et al. Leveraging Network Data Analytics Function and Machine Learning for Data Collection, Resource Optimization, Security and Privacy in 6G Networks. IEEE Access, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardatos, P.; Papastefanopoulos, V.; Kotsiantis, S. Explainable AI: A Review of Machine Learning Interpretability Methods. Entropy 2021, 23, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamida, S.U.; Chowdhury, M.J.M.; Chakraborty, N.R.; Biswas, K.; Sami, S.K. Exploring the Landscape of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): A Systematic Review of Techniques and Applications. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2024, 8, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkonis, P.; Giannopoulos, A.; Trakadas, P.; Masip-Bruin, X.; D’Andria, F. A Survey on IoT-Edge-Cloud Continuum Systems: Status, Challenges, Use Cases, and Open Issues. Future Internet 2023, 15, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Β.; Vu, M. Interference Analysis for Coexistence of Terrestrial Networks With Satellite Services. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2024, 23, 3146–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Related Work | Year | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| [27] | 2024 | CRAN |

| [28] | 2024 | M2M Communications in the 6G era |

| [29] | 2024 | Joint Sensing and Communication in the 6G era |

| [30] | 2024 | Key enabling technologies for 6G Networks - Potentials of AI/ML |

| [31] | 2024 | AI-enabled 6G networks |

| Our work | - | Current trends in the architectural design of 6G Networks |

| Related Work | Main Concept | 6G Key Enabling Technologies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI/ML | Digital Twins | Open interfaces | Network Slicing | Cell free approaches | ||

| [47] | Organic 6G networks | √ | ||||

| [48] | Threat prediction and mitigation | √ | √ | |||

| [50] | Network Slicing | √ | ||||

| [51] | Cell Free Networks | √ | ||||

| [52] | 6G Vision | √ | ||||

| [53] | Open RAN | √ | √ | |||

| [54] | Multi-layered architecture | √ | √ | √ | ||

| [55] | 6G multi-layer vision | √ | √ | |||

| [57] | 6G architectural design based on DTs | √ | ||||

| [58] | Flexible layered architecture | √ | √ | |||

| [59] | Basic 6G trends | √ | √ | |||

| [61] | Self-evolving 6G networks | √ | ||||

| [62] | Deep reinforcement learning in 6G networks | √ | ||||

| [63] | Building blocks for 6G | √ | √ | |||

| [64] | 6G project ANNA | √ | √ | |||

| [66] | Slicing concept in 6G | √ | √ | √ | ||

| [67] | 6G for smart cities | √ | ||||

| [68] | 6G for smart cities | √ | ||||

| [69] | 6G for smart cities | √ | ||||

| [70] | Current 6G trends | √ | √ | |||

| [71] | 6G - PREDICT | √ | √ | |||

| [72] | Advanced 6G use cases | √ | √ | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).