2.2. Treuhaft’s Model

To examine the sensitivity of an interferometric SAR response to the physical characteristics of forest stands, [

9,

10] employ a coherent scattering model for tree canopies. The scattering phase center of the pixel, determined by InSAR, is characterized through the concept of an equivalent scatterer representing a collective of scatterers inside a pixel, which corresponds to the vegetative components of arboreal structures. A first-order scattering model applied to fractal-generated tree structures is integrated with a newly established equivalency relation between InSAR and the correlation coefficient of forest stands, determined numerically, to develop the model. The wavelength, slant range, baseline distance between antennas, antenna orientation, and the height of the scattering phase center above a reference line all influence the phase of the interferogram. Moreover, the requisite statistics for height estimation utilizing InSAR can be acquired by comprehending the frequency correlation characteristics of radar backscatter. The height estimation of a distributed target is unaffected by baseline distance and relies solely on the comparable frequency decorrelation bandwidth. [

8,

9,

10] elucidates the methodology for evaluating extinction, physical height, and the height of the scattering phase center of a closed, homogeneous, semi-infinite canopy through the characteristics measured via InSAR.

To assess biomass, leaf area index, and vegetation type, it is essential to evaluate both the topographic attributes of the plant and its characteristics in relation to vertical height above the ground. This is referred to as vertical structure. While polarimetry mostly responds to the shape and alignment of plant scatterers, radar interferometry predominantly reacts to the spatial arrangement of vegetation. Consequently, polarimetric interferometry, which involves interferometry across all possible polarization channels at each end of the baseline, is far more sensitive to the arrangement of oriented objects in a vegetated landscape than either polarimetry or interferometry used independently. This intricate cross-correlation is articulated through three physical models for vegetation parameters in [

1,

2,

8,

9]: (1) a randomly oriented volume; (2) a randomly oriented volume with ground return; and (3) an oriented volume. It is concluded that parameter estimation using less constrained and more realistic models will be feasible with fully polarimetric interferometry. Consequently, vertical-structure parameters obtained from polarimetric interferometry may exhibit more accuracy than those estimated from the combination of zero-baseline polarimetry and interferometry.

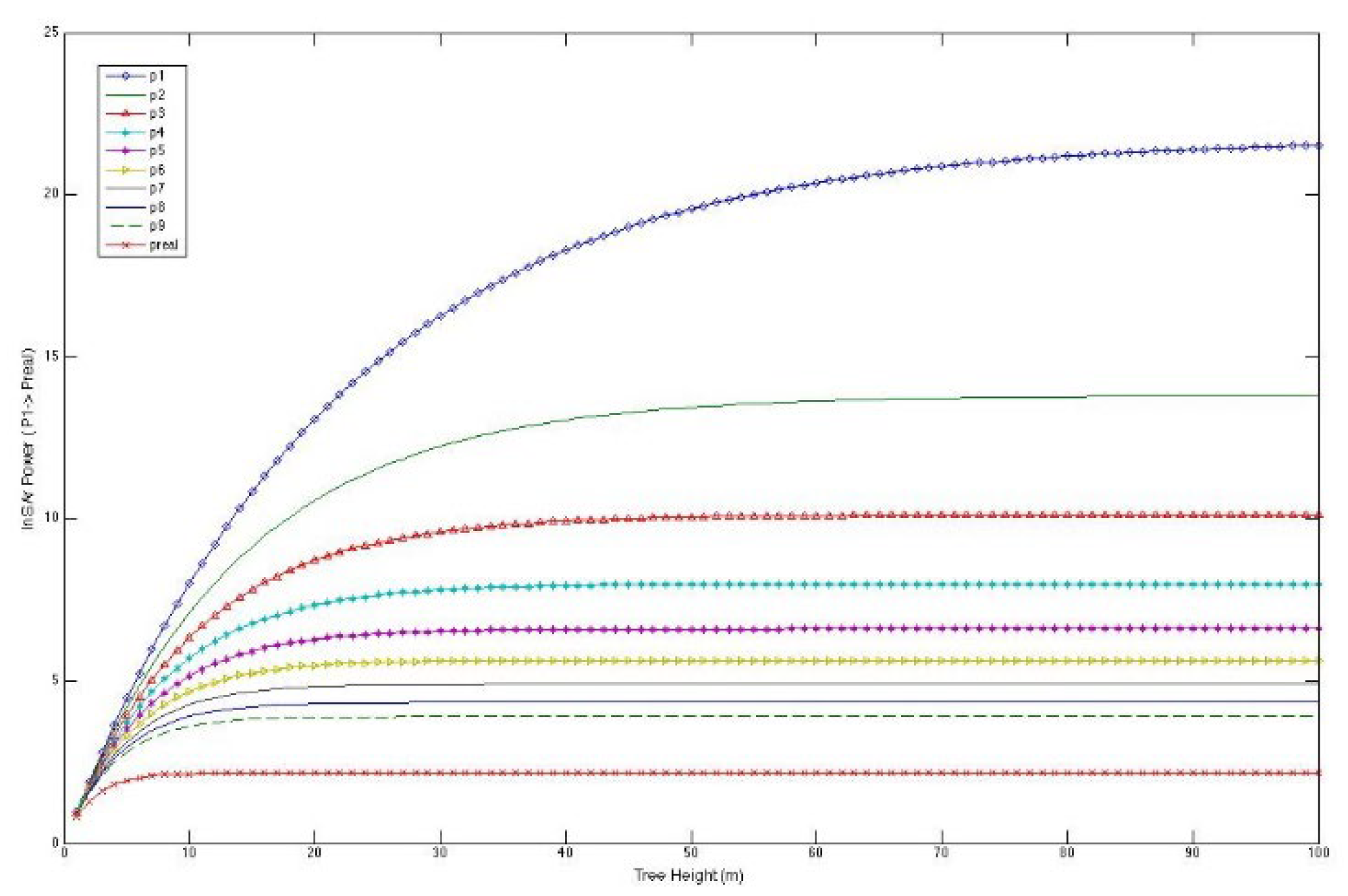

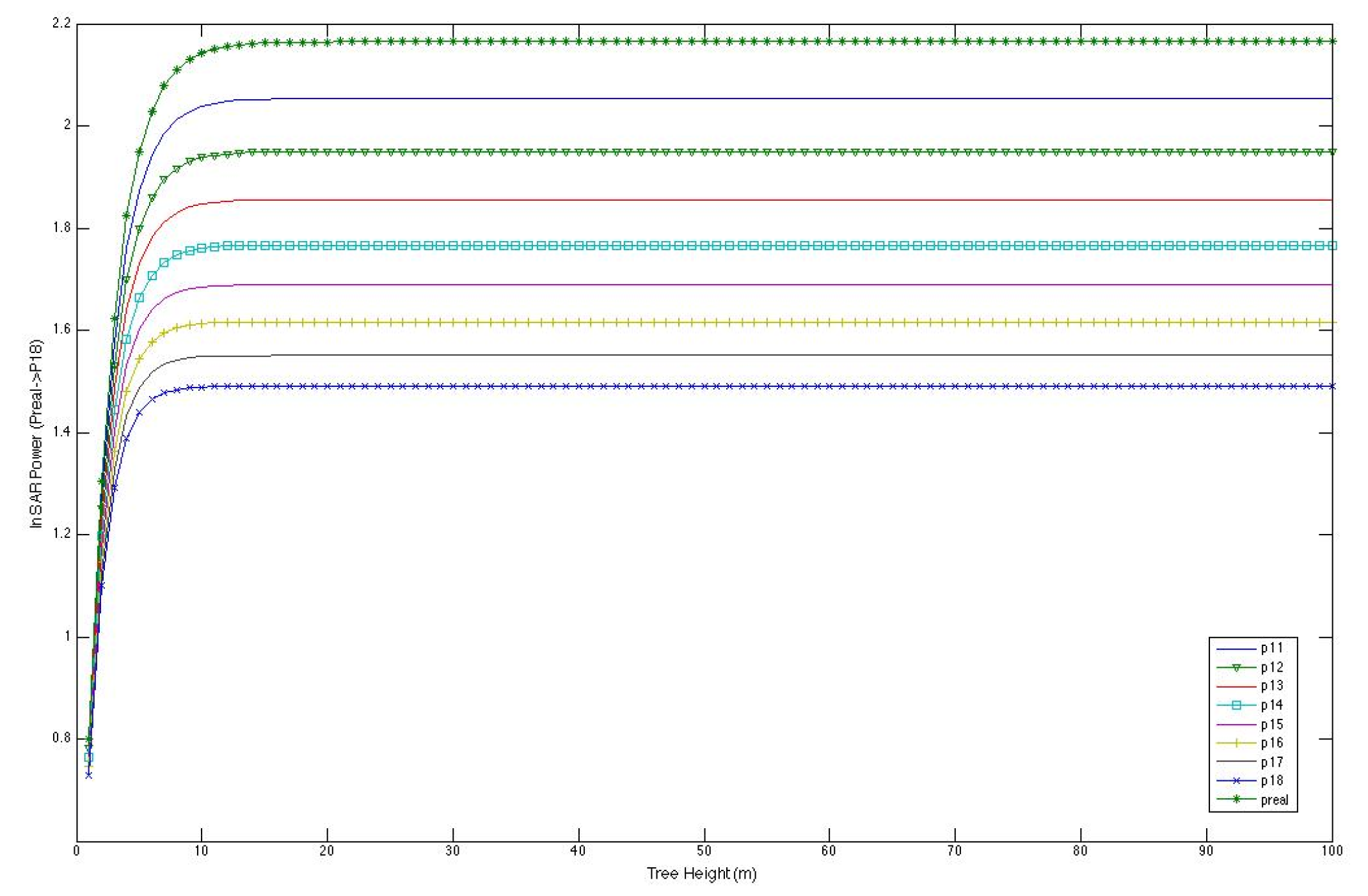

The primary characteristics of a forest random medium are biomass and vertical structure. This study [

8,

9] employs a uniform, random-volume model of the forest medium to assess the sensitivity of power and interferometric synthetic aperture radar to tree height and vegetation density, considering extinction along with speckle and thermal noise. Calculations indicate that radar power exhibits more resilience to structural and biomass interference than InSAR coherence and phase.

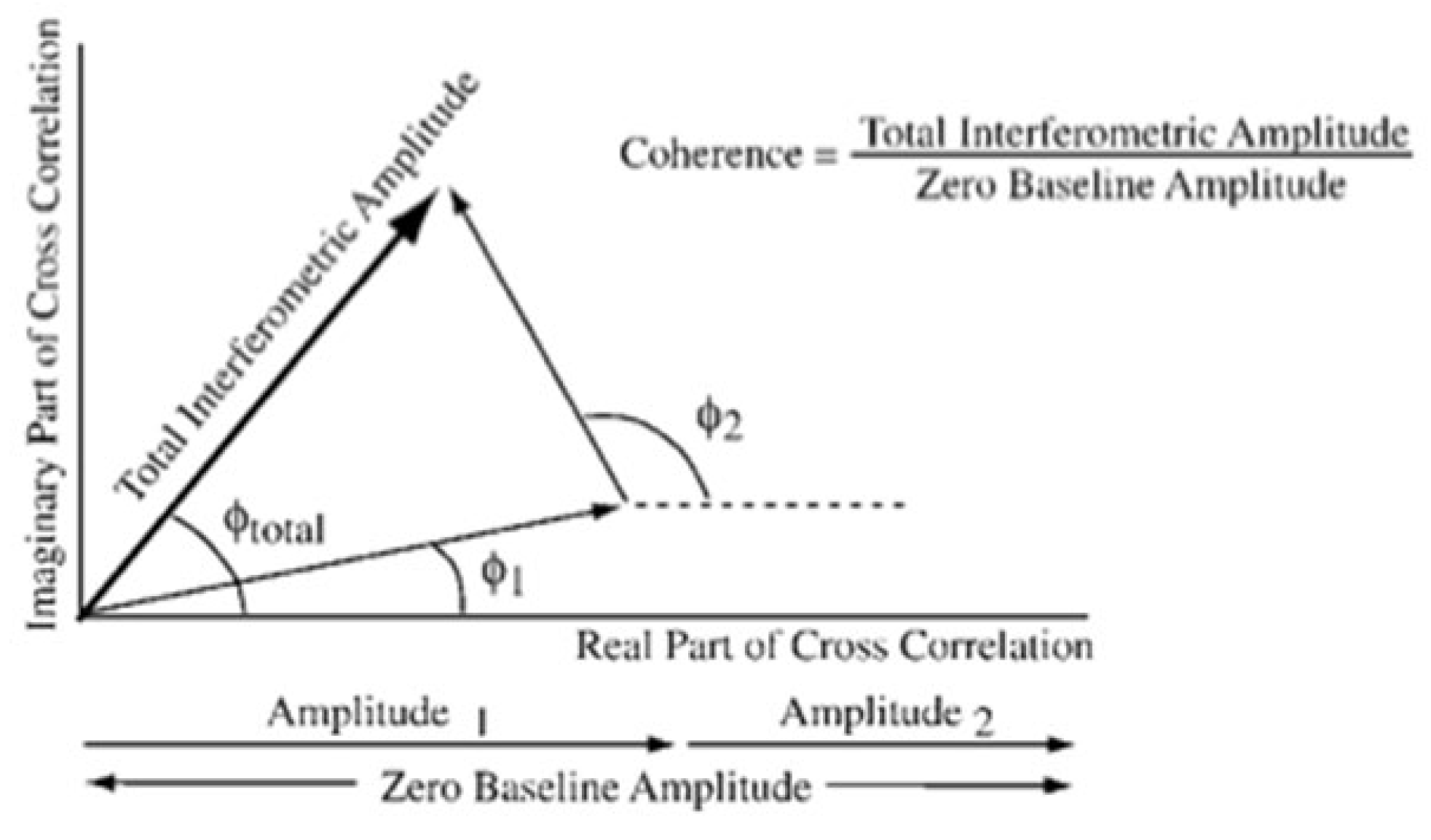

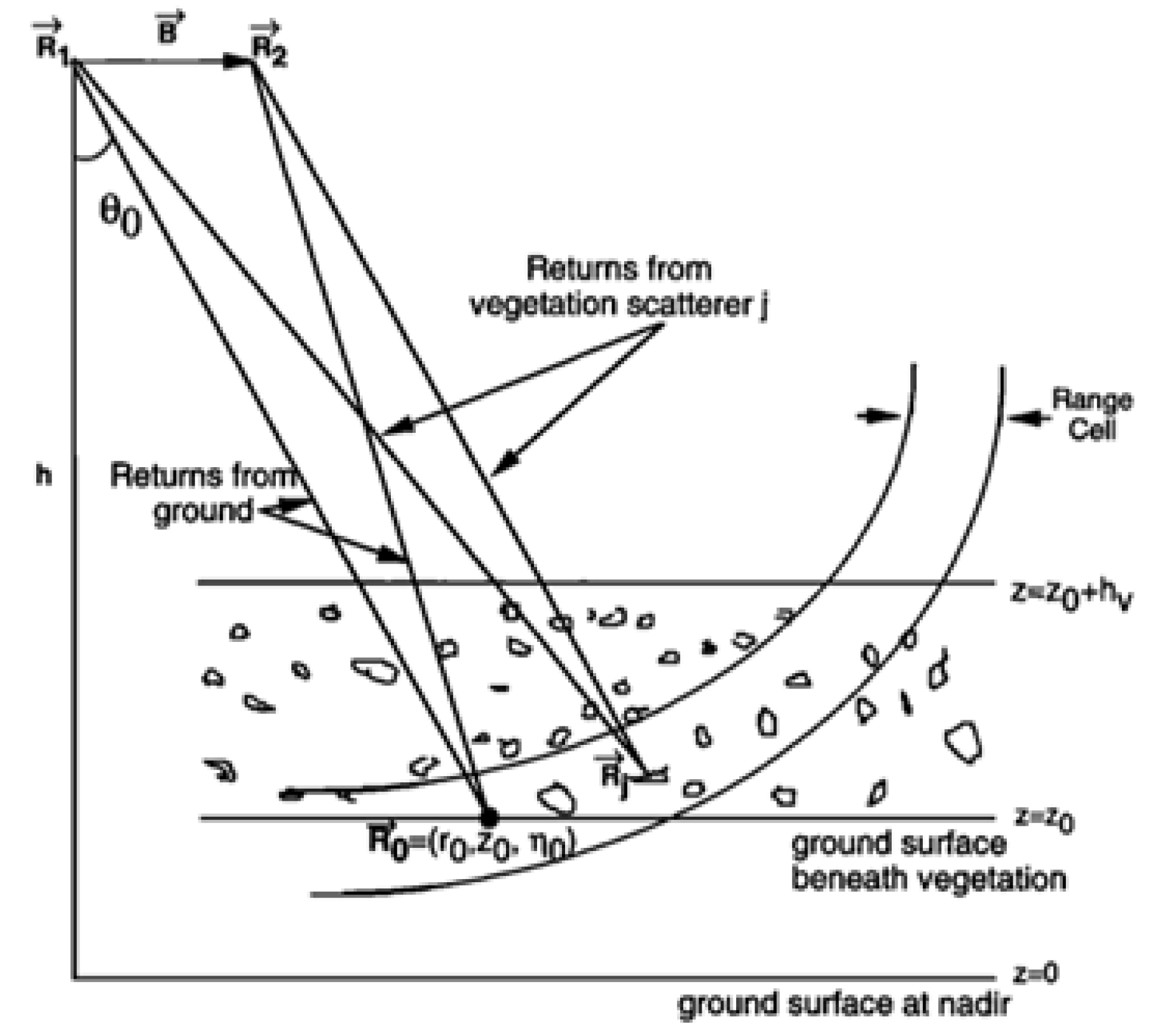

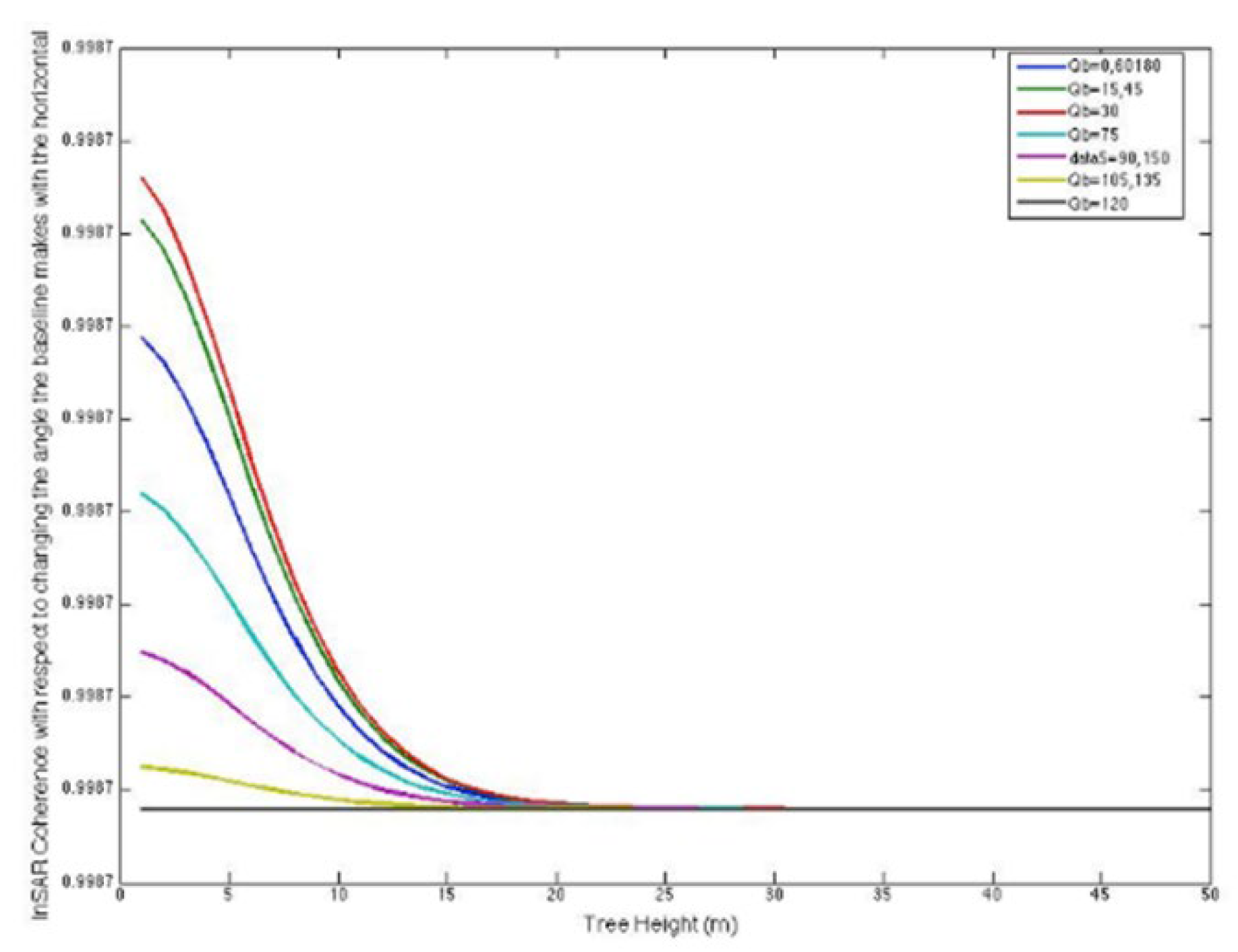

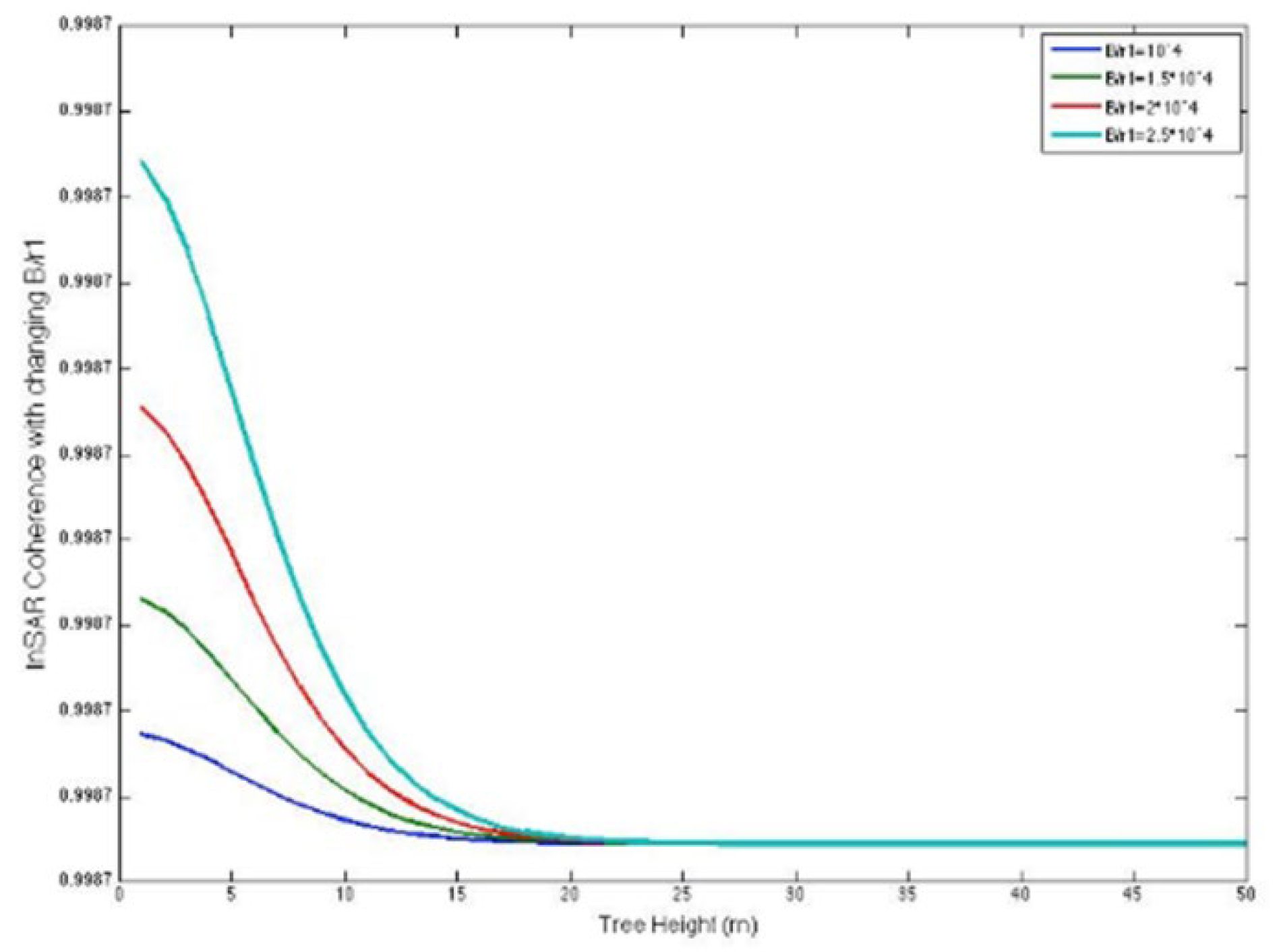

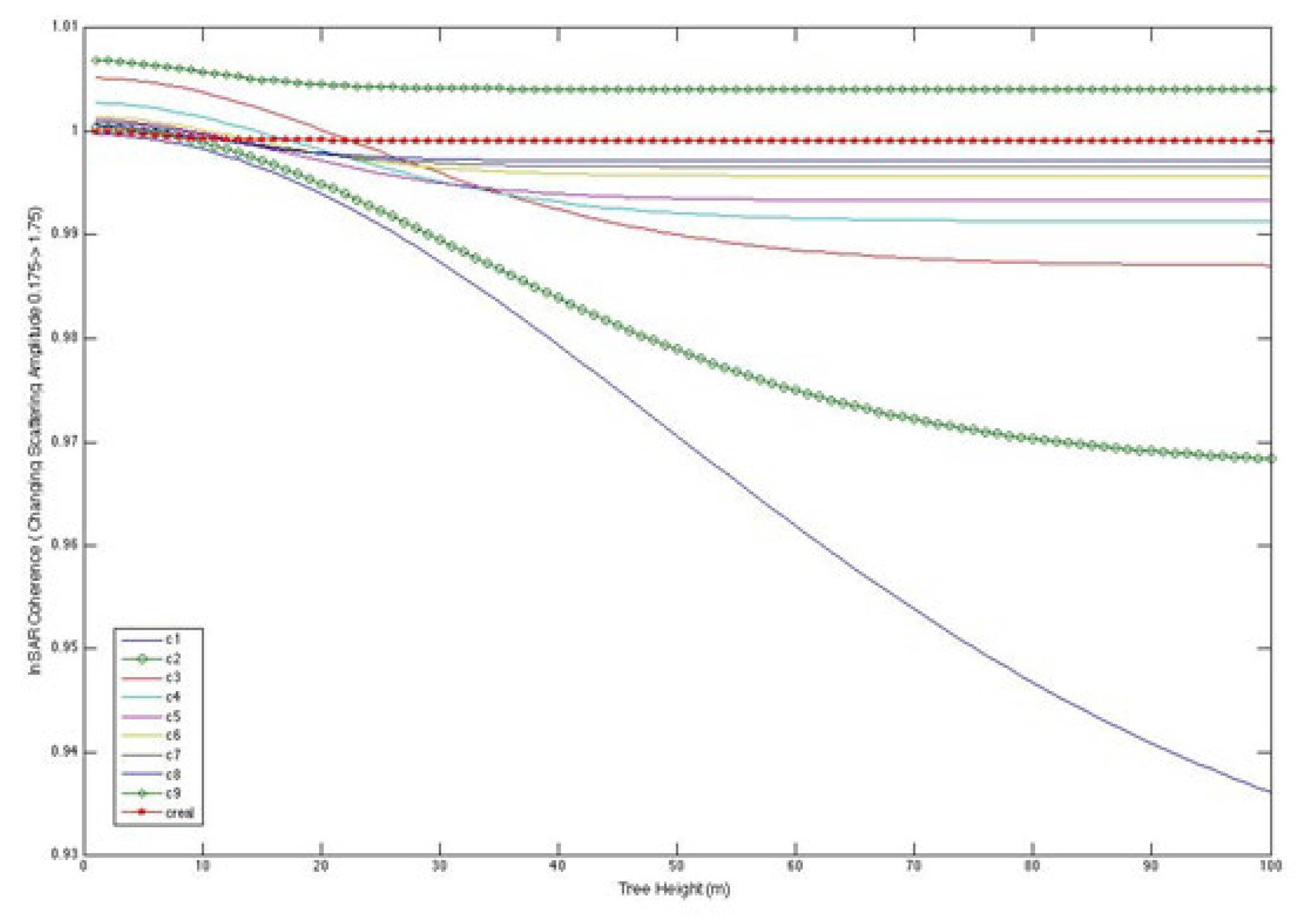

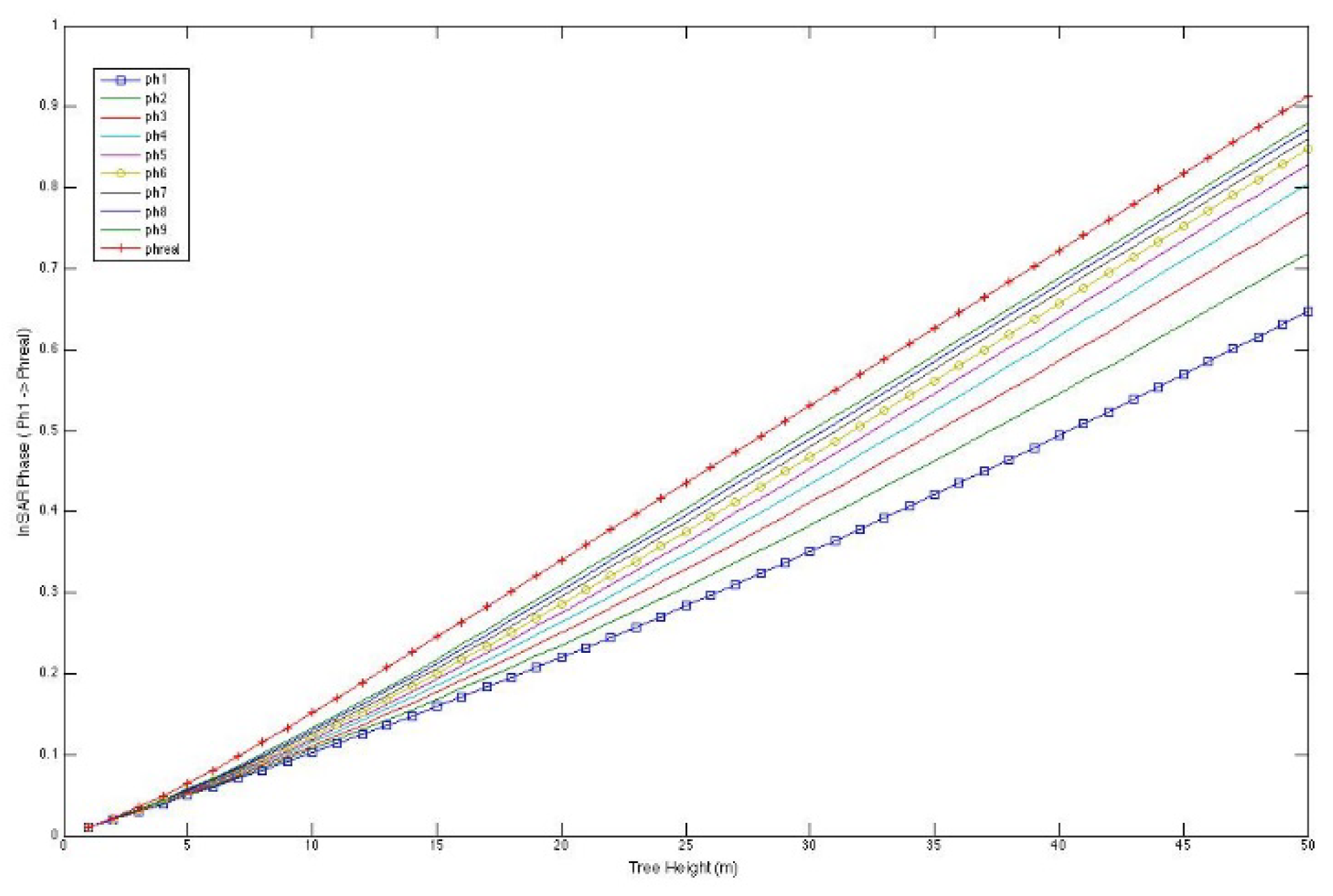

Figure 1 demonstrates that InSAR-based methodologies for structure and biomass assessment surpass SAR power in scenarios of elevated biomass and dense vegetation [

1,

2,

8,

9]. As tree height increases, InSAR coherence diminishes and attains a saturation threshold beyond 40 meters. The InSAR phase continues to increase without attaining saturation. The lengths of the vectors representing each vegetation element are proportional to the vegetation density to accommodate for attenuation at every height. If vegetation elements are distributed vertically, the overall interferometric amplitude is inferior to the zero baseline, and the coherence is below 1. The extreme vegetation components constitute the comprehensive interferometric phase. The interferometric phase elevates while the interferometric coherence diminishes as canopy heights grow. The biomass is directly proportional to the x-axis according to the fundamental model’s assumptions.

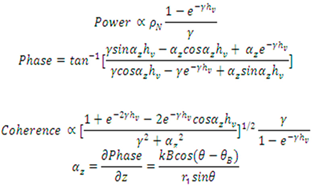

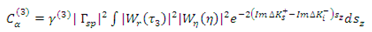

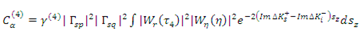

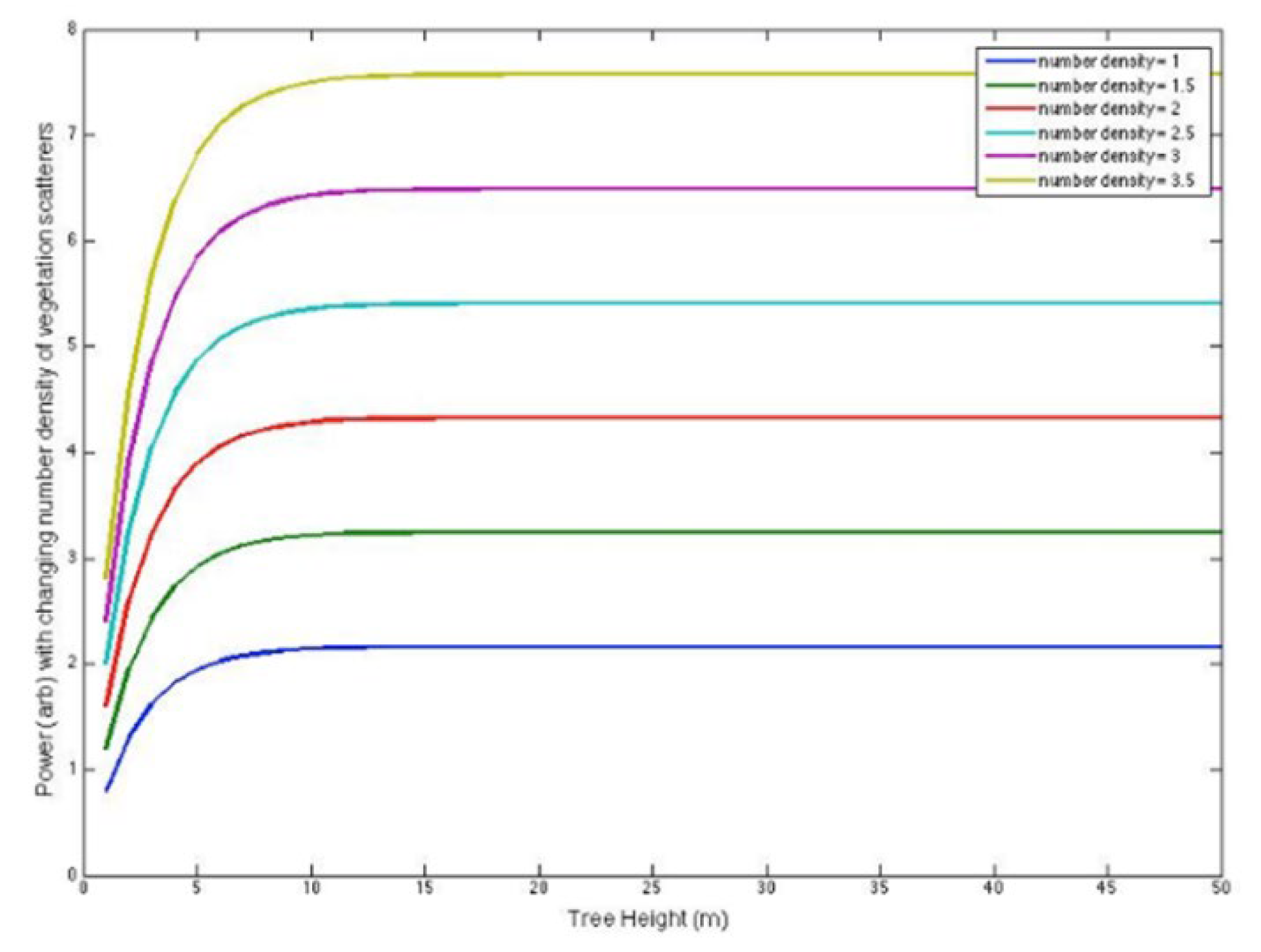

Power, phase, and coherence are found to be proportional to the terms in (1) [

3].

where α_z denotes the partial derivative of the interferometric phase with respect to altitude above the ground surface. To maintain simplicity, variations in absorption are neglected for a constant canopy height of 30 m, positing that alterations in ρN (vegetation scatterer number density) are the sole contributors to extinction variations, rather than fluctuations in Im (absorption). Assuming constant absorption, the extinction coefficient is considered proportional to biomass and solely reflects variations in density.

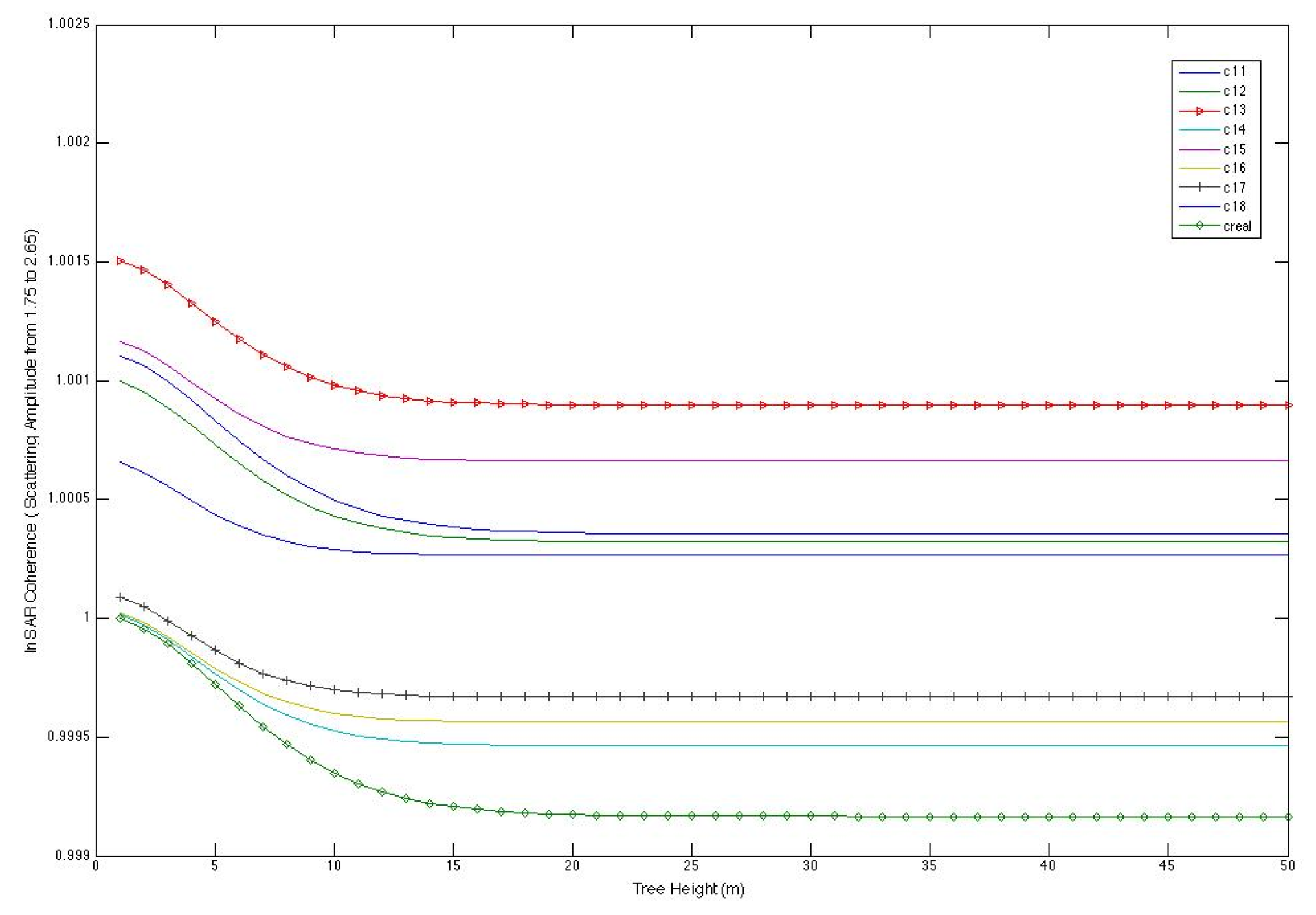

The augmentation of power is associated with the elevation of the trees. As the signal is increasingly influenced by elevated canopy heights and a diminished portion of the forest’s vertical expanse contributes, the InSAR coherence correspondingly rises with extinction. The augmentation in InSAR phase is additionally attributed to contributions from higher altitudes [

1,

3]. It is reasonable to anticipate that biomass will increase with heightened vegetation density or height. A comparison of the unique coherence behavior in

Figure 2 with efforts to develop novel biomass patterns is advised. Instead of representing biomass through raw coherence and phase measurements, the figures emphasize the advantage of deriving structural aspects from the interferometric data. Even at minimal extinctions, InSAR surpasses power in detecting height variations. Furthermore, it is posited that, with the exception of the lowest biomasses, the majority of biomass values at L- and C-band frequencies exhibit greater sensitivity than power. If the primary distinction between stands is density, then extinctions diminish at lower frequencies, such as P-band, which may enhance radar power for the assessment of low biomass, low-density standards.

InSAR observations demonstrate superior sensitivity to height fluctuations compared to power. The non-uniqueness of signatures in data formats and the associated challenges of inversion impact both power and InSAR observations similarly. Generally, structure exhibits more sensitivity to InSAR measurements than power. The model examined in this work indicates that tree height and the extinction coefficient cannot be uniquely ascertained from a solitary InSAR measurement of coherence and phase. Nevertheless, the literature contains examples that illustrate the distinctive capability to ascertain tree height, extinction, and many structural profile features through the integration of multi-baseline, multi-polarization, or multi-frequency InSAR. The modeling process encompasses the simulation of electromagnetic scattering and radar processing that produce InSAR observations, the identification of vegetation and topographic parameters for estimation, the assessment of parameter errors relative to InSAR instrumental performance, and the demonstration of parameter estimation using InSAR data, followed by a comparison with ground truth. Three metrics were assessed: the SAR backscattered power, the cross-correlation phase, and the cross-correlation amplitude. To characterize the vegetation and surface topography, the following parameters were identified: the elevation of the underlying ground surface, the depth of the vegetation layer, the vegetation extinction coefficient (power loss per unit length), and a parameter representing the product of the average backscattering amplitude and scatterer number density.

Figure 2 illustrates the two antennas employed in the InSAR technology, wherein transmitted microwave radiation is reflected from the Earth’s surface and received by these antennas. These antennas represent the termini of an interferometric baseline, shown as B in the picture. B is equivalent to the positional difference between receivers 2 and 1, R

2 - R

1. For the sake of simplicity, both the baseline and the ground surface are assumed to be horizontal. Two receivers and one transmitter are applicable for usage aboard aircraft. The observed vegetation area extends from z=0, representing the ground surface height, to z

0+h

v, where h

v denotes the depth of the vegetation layer. The intricate relationship of the fields obtained at the extremities of the baseline is the primary form of interferometric data. Equating the arguments of the range resolution functions yields the final expression for the cross-correlation.

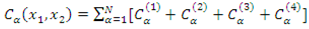

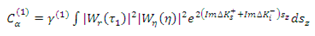

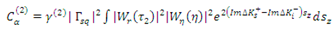

can be re-written as;

In (4), the weight function Wη is included, where η is the azimuthal angle measured in the horizontal plane. The Wη function results from the process of synthesizing the aperture.”

The range resolution function Wr is given by:

where the transmitted pulse, with Fourier transform G(ω), is centered at time t=0, and ω0 is the center frequency of the transmitted signal. W

r is symmetric about its maximum, which occurs when its argument is zero.

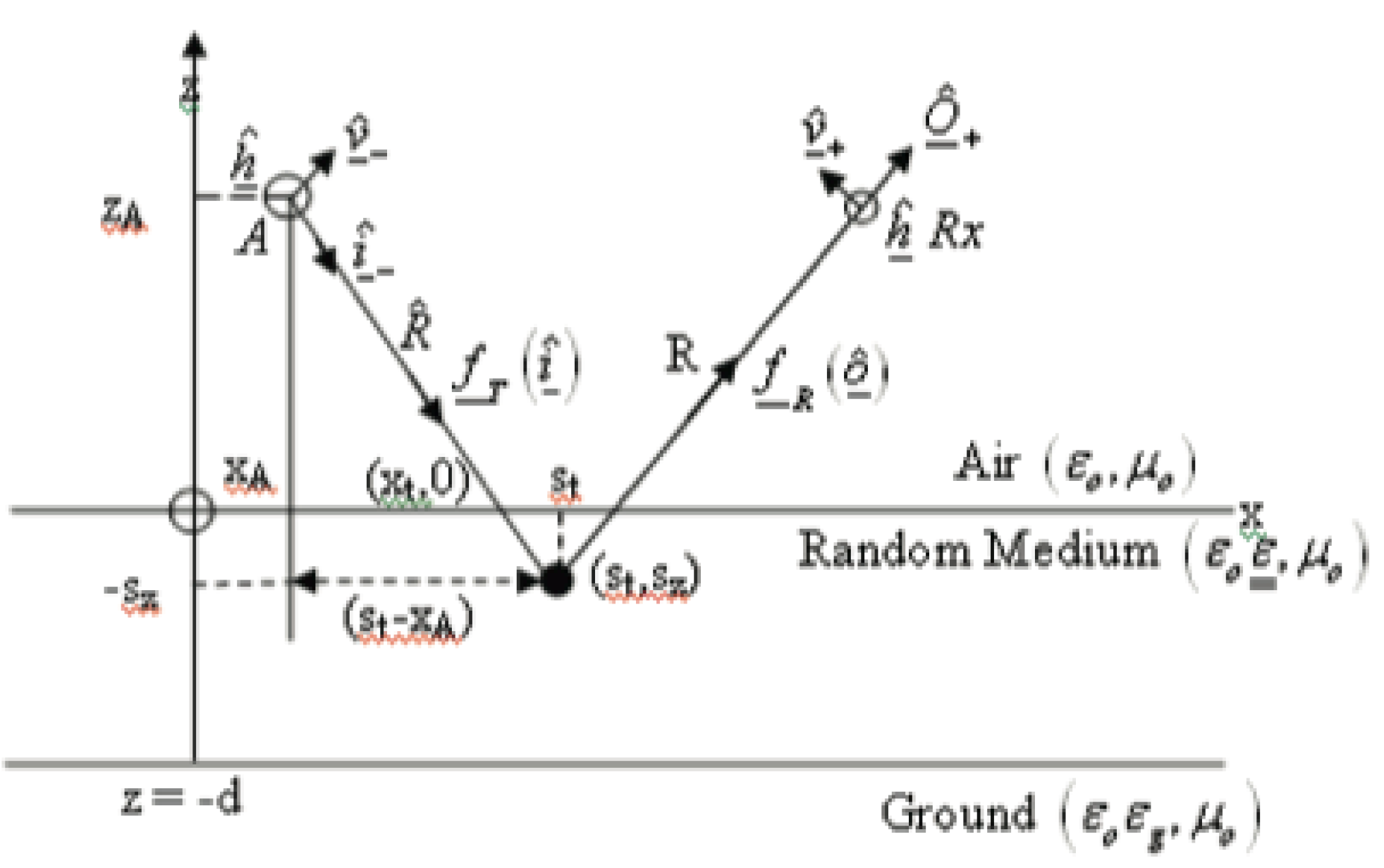

Let the far field from transmitter A, on the interface of the layer of random medium electric field is shown in

Figure 3.

where

is wave number,

is the antenna pattern of the transmitter, and R is the distance. [

11,

12] find the correlation of the fluctuating component of the scattering field as,

where ese (x,s) is the scattered field at x due to a scatterer at s and ρ(s) is the density of particles.

From (8), the correlation of the field is found as:

where

is assumed.

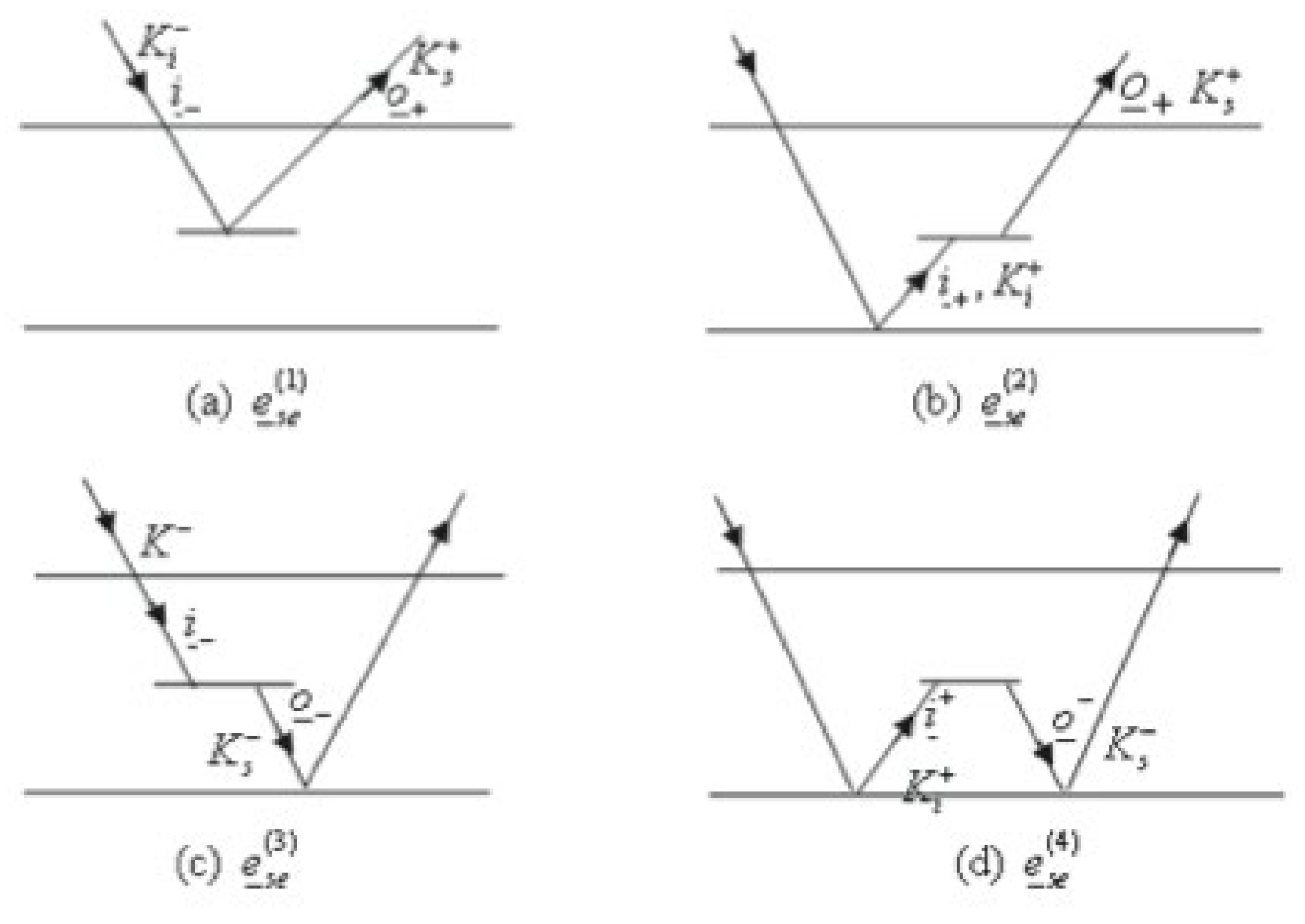

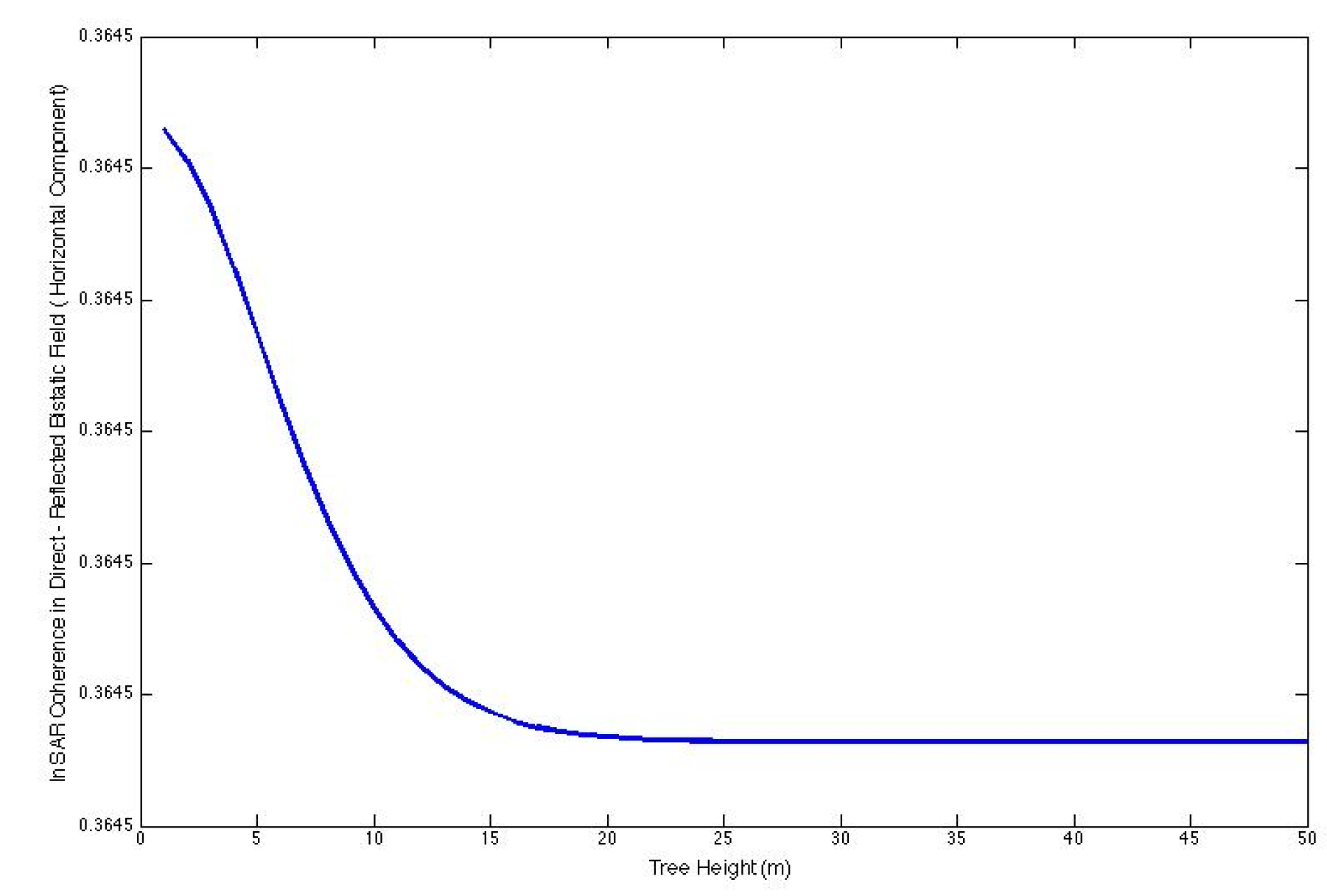

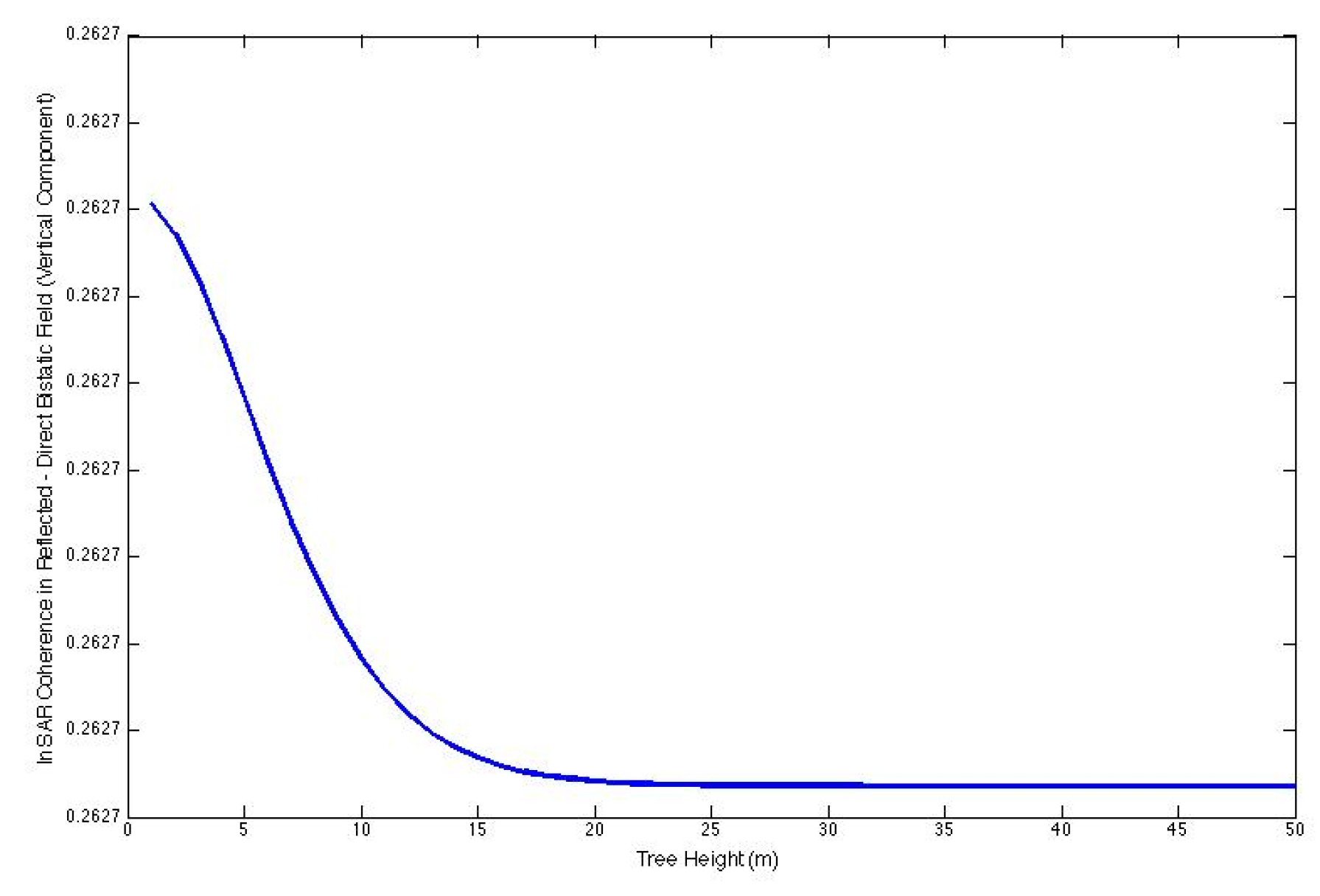

Figure 4 illustrates the four trajectories of the bi-static field. These four options manifest as reflection coefficients during the correlation of fields. The aforementioned equations and

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 yield the four routes of the bi-static field for a narrow-band signal.

where α=1 for the trunk, α=2 for the branch and α=3 for leaves.

Where

where A is the area and,

If we let θ

s = θ

i, then Im ▁f(0) = Im▁( f)(i) = Im ▁f hence

Thus (2.13) takes the form

An analysis of the terminology in Treuhaft’s Model and Seker & Lang’s Model revealed that both are identical. In Seker’s model, the parameters of the weight and range resolution functions are not displayed. Furthermore, the expression is designated as sz. The particle density is assumed to be constant in both equations. The symbols (r1-r2) and (R1-R2) in both equations appear identical, as do the notations ,

Without the arguments, correlation eq. can be given as:

Comparing both models, the only parameters needed to equate are the terms

and

Since it isknown that the scattering amplitude, is equal to

term. From here, the equivalence below can be obtained.

A is the distance for spherical waves,

.

is the center of range and azimuth resolutions at z

0. Both

and

are shown in

Figure 2. These comparisons can also be seen from

Table 1.

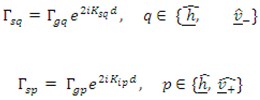

2.3. Reflection Coefficient Contribution

The contributions of reflection coefficients to correlation equations can be ascertained from the research in [

9]. Models for polarimetry and interferometry, including polarimetric interferometry, can be cohesively created by establishing a general complex cross-correlation. This study introduces three physical models that elucidate the intricate cross-correlation concerning vegetation parameters: (1) an oriented volume, (2) a randomly oriented volume with ground return, and (3) an orientated volume. The initial two models incorporate the following elements: vegetation height, extinction coefficient, underlying topography, and an extra component derived from the electrical properties and roughness of the terrain. The refractivity, extinction coefficients, and backscattering characteristics of waves traveling through the vegetative volume establish further parameters for the oriented volume. These models indicate a 1% probability for each meter of variation in vegetation height in the polarimetric {HHHH/VVVV} (H ̂ to V ̂, transmit and receive, polarimetric power ratio) and the interferometric cross-correlation amplitude. The study asserts that parameter estimation can be enhanced in realism and accuracy by the application of single-baseline and multi-baseline totally polarimetric interferometry.

The broadest cross-correlation, appropriate for both polarimetry and interferometry, is:

where

is the receive polarization at end 1 of the baseline, located at

, and

is the vector signal received at

, due to a wave transmitted at the polarization

.

is the receive polarization at end 2 of the baseline, while

is the transmit polarization, which induces the return received at end 2 of the baseline. The ensemble average angle brackets in (26) indicate the average overall statistical properties of the terrain which affect the signals.

In (26), the transmit and receive polarizations

,

and

can be arbitrary, linear, complex (e.g., for circular polarization) combinations of

. The polarization and baseline conventions describing “interferometry” (INSAR), “polarimetry” (POLSAR) and “polarimetric interferometry” (POLINSAR) are given in [

9].

2.4. Homogeneous Randomly Oriented Volume

The fundamental vegetation model, characterized by a homogeneous randomly oriented volume, serves as a valuable foundation for considering INSAR, POLSAR, and POLINSAR. Each model scenario presented in [

9] includes a summary of its parameters and observations. The decrease in specular amplitude caused by roughness is represented by the term Γ

rough.

where σH is the expected Gaussian-distributed ground heights are standardly derivable. Although it always multiplies the reflection coefficient, the ground roughness term is added for completeness, therefore by itself, σH will not appear as a parameter. The whole path length is included in the equal phases of the ground-volume and volume-ground components. The length of this path,

, is about equivalent to

. The cross-correlation by utilizing the equivalence of these path lengths are obtained. The discrete model demonstrates that the interferometric cross-correlation yields four fundamental terms, as elucidated in [

9]. The various combinations of ground-volume and volume-ground that are interrelated are illustrated by the four ground terms in the cross-correlation. Due to attenuation in the vegetation, components related to ground-volume-ground returns (two specular reflections) have been omitted as they are often negligible. In [

3], the propagation routes are modeled as depicted in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. The direct incidence of the bistatic field, which is directly scattered, corresponds to the direct-ground scattering process illustrated in

Figure 2. The reflected direct bistatic field depicted in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 corresponds to the specular ground volume illustrated in the figure. The direct-reflected field pertains to the specular volume-ground scattering. The comparisons are also included in

Table 2.

Besides these bistatic fields, [

3] addresses an alternative scattering mechanism, specifically the reflected-reflected bistatic field. This idea is not addressed in [

9]. Terms involving ground-volume-ground returns (two specular reflections) have been omitted due to their typically little impact resulting from attenuation in the vegetation.