Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search strategy

2.2. Study selection

2.5. Data extraction

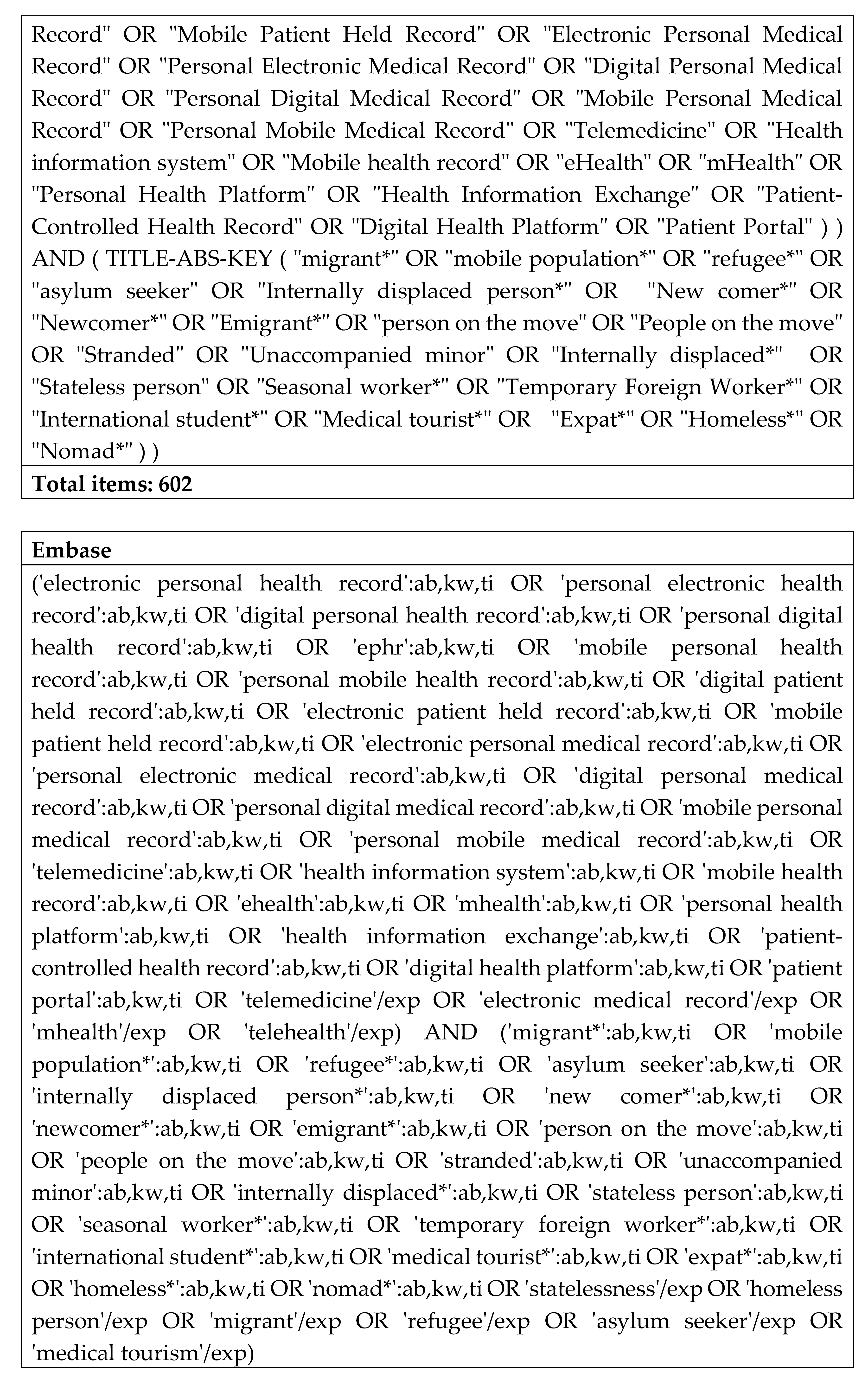

2.6. Grey literature

2.7. Synthesis of results

2.8. Ethical review statement

2.9. Patient and public involvement statement

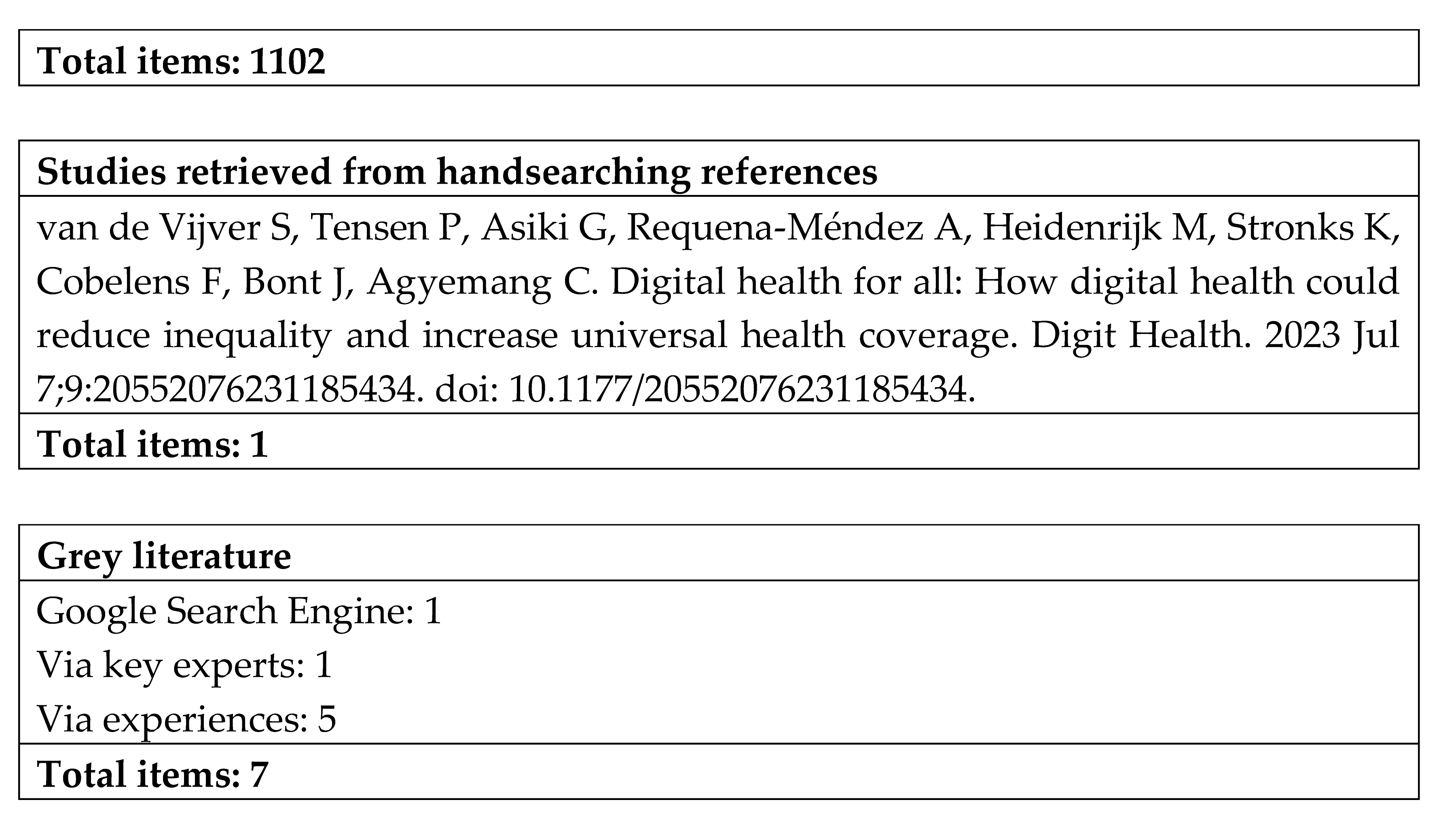

3. Results

3.1. Literature

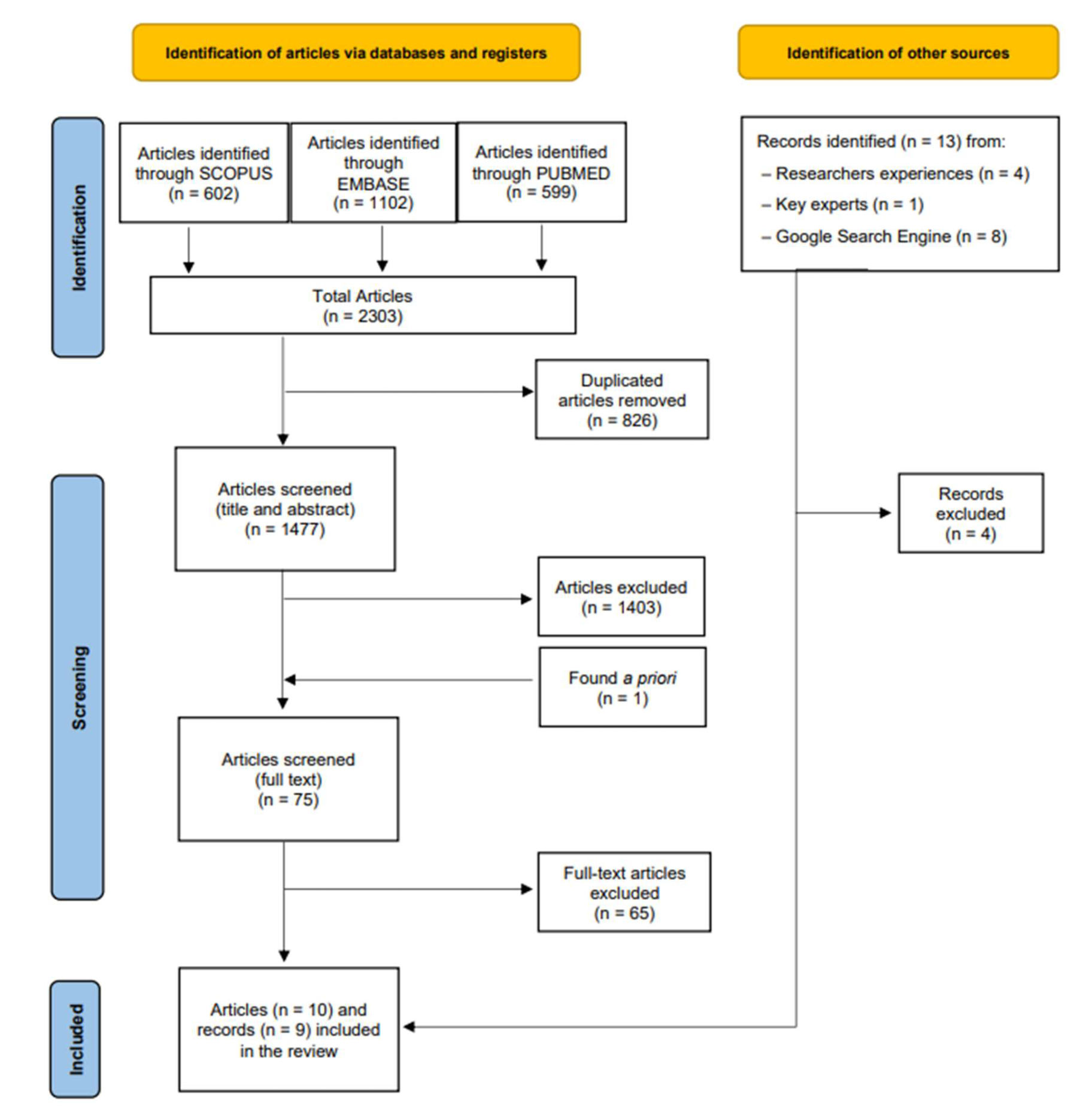

3.1.1. Eligible scientific publications

3.1.2. Grey literature

3.2. Initiatives

3.2.1. Main characteristics of the tools identified

3.2.2. Medical information and data management

3.2.3. User experiences of the tools identified (including health-related outcomes)

3.2.4. User engagement in tool development

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of key findings

4.2. Implications for research and practice

4.3. Strengths and limitations

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

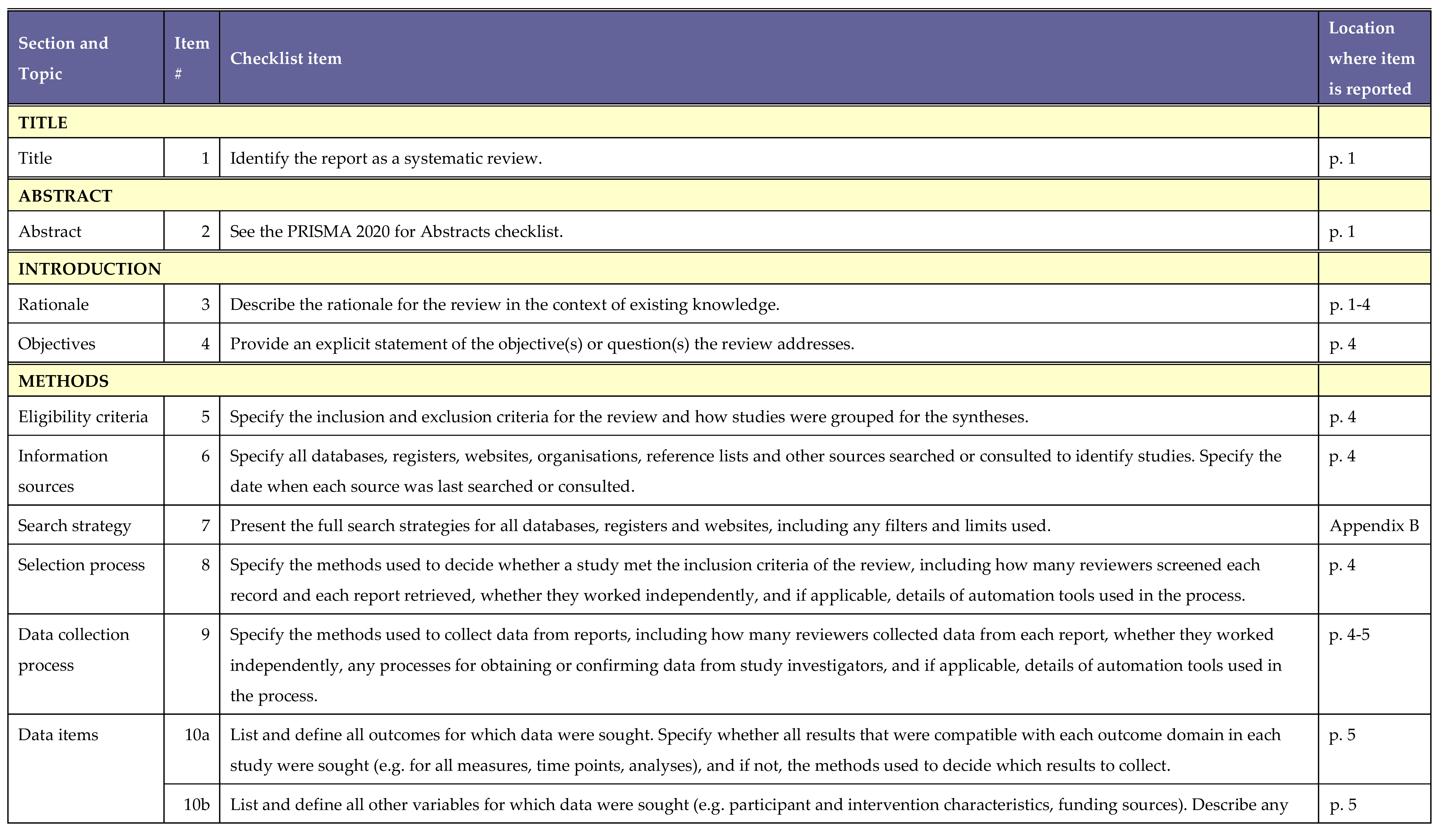

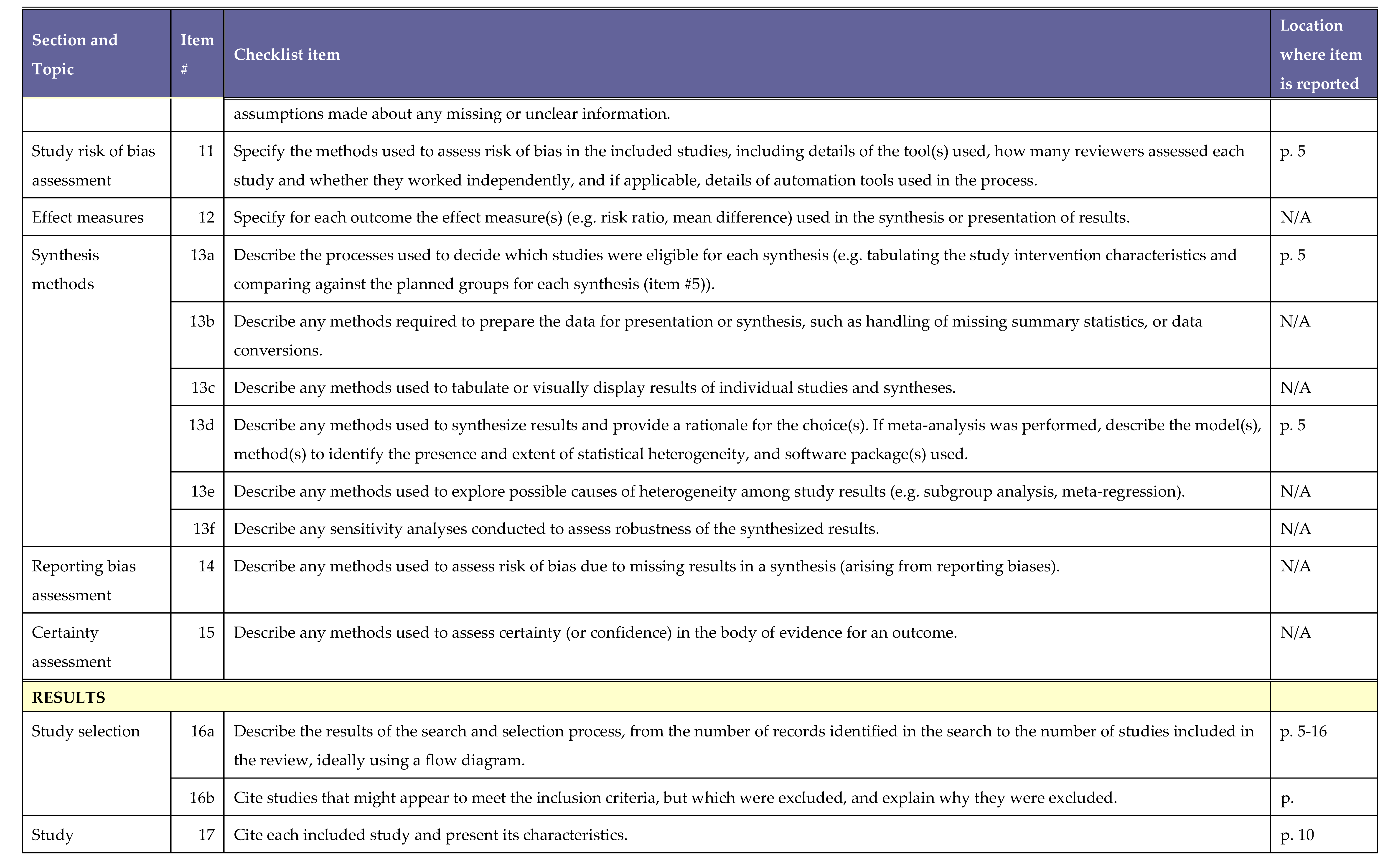

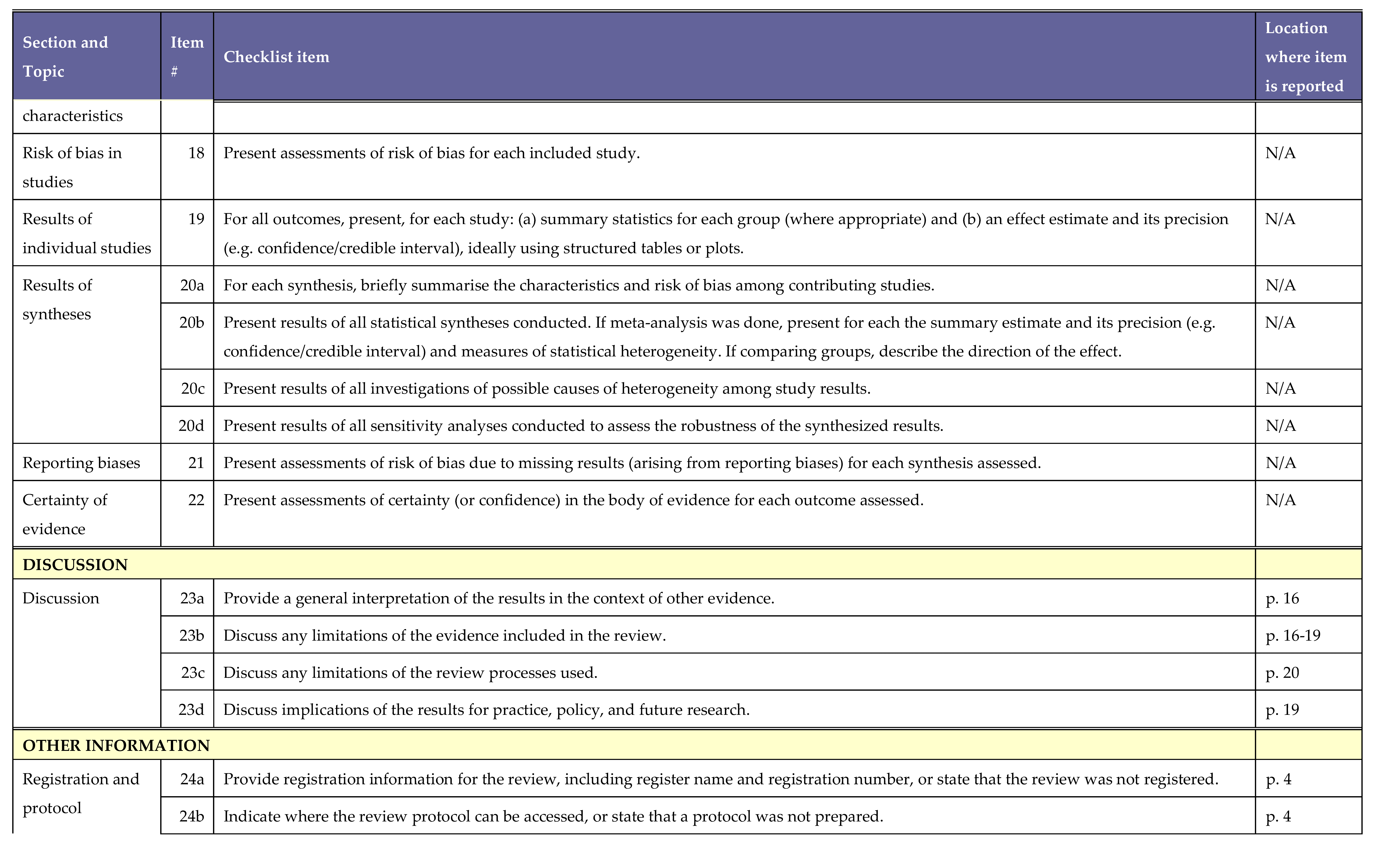

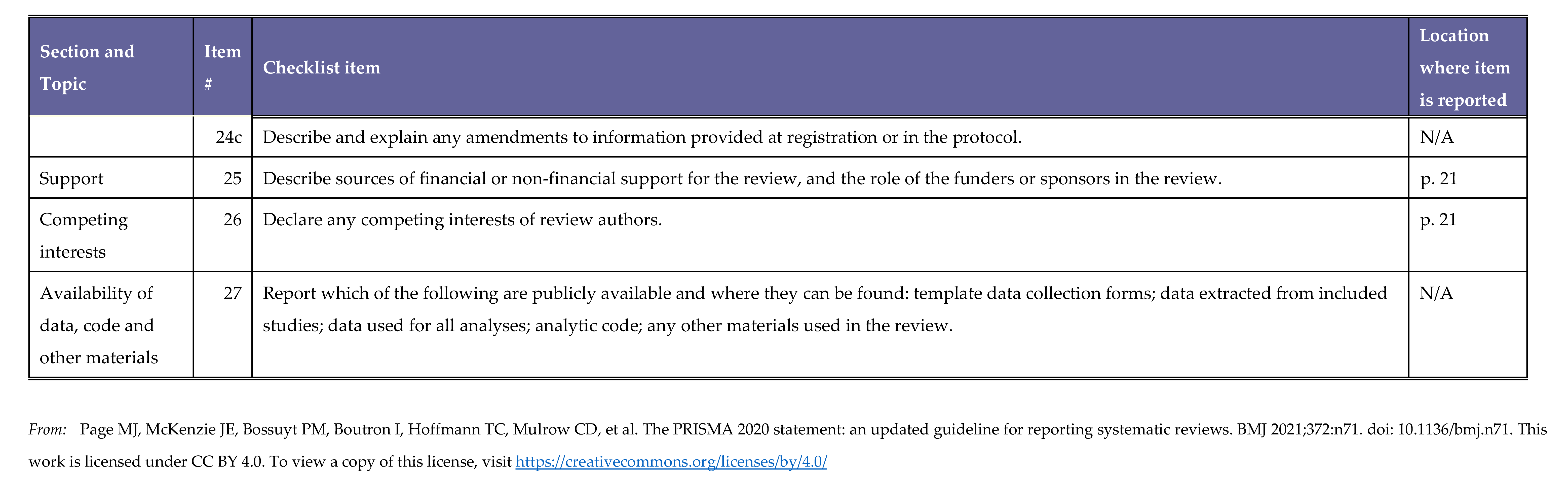

Appendix A: PRISMA checklist for systematic reviews.

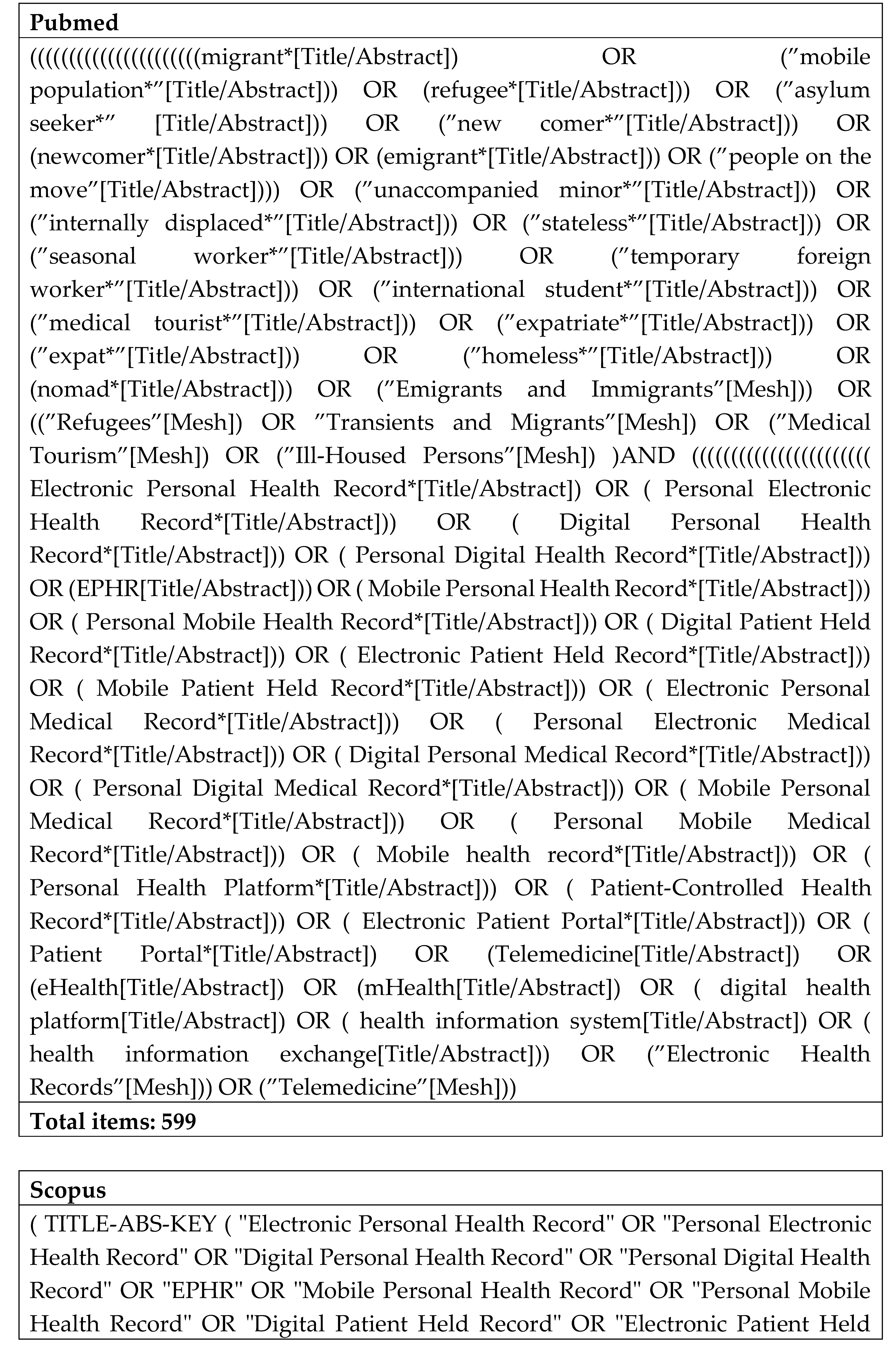

Appendix B: Search queries used for each database.

References

- Fundamentals of Migration. Available online: https://www.iom.int/fundamentals-migration (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- The International Organization for Migration World Migration Report 2024; 2024.

- UNHCR Global Trends Report 2023; 2024.

- Abubakar, I.; Aldridge, R.W.; Devakumar, D.; Orcutt, M.; Burns, R.; Barreto, M.L.; Dhavan, P.; Fouad, F.M.; Groce, N.; Guo, Y.; et al. The UCL–Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: The Health of a World on the Move. The Lancet 2018, 392, 2606–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binagwaho, A.; Mathewos, K. The Right to Health. Health Hum Rights 2023, 25, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chiesa, V.; Chiarenza, A.; Mosca, D.; Rechel, B. Health Records for Migrants and Refugees: A Systematic Review. Health Policy 2019, 123, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarenza, A.; Dauvrin, M.; Chiesa, V.; Baatout, S.; Verrept, H. Supporting Access to Healthcare for Refugees and Migrants in European Countries under Particular Migratory Pressure. BMC Health Services Research 2019, 19, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, M.; Rechel, B.; de Jong, L.; Pavlova, M. A Systematic Review on the Use of Healthcare Services by Undocumented Migrants in Europe. BMC Health Services Research 2018, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, V.; Santos, J.V.; Pinto, M.; Ferreira, J.; Lema, I.; Lopes, F.; Freitas, A. Health Records as the Basis of Clinical Coding: Is the Quality Adequate? A Qualitative Study of Medical Coders’ Perceptions. HIM J 2020, 49, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Kantamaturapoj, K.; Putthasri, W.; Prakongsai, P. Challenges in the Provision of Healthcare Services for Migrants: A Systematic Review through Providers’ Lens. BMC Health Services Research 2015, 15, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, G.; Kulshreshtha, N.; Greenfield, G.; Li, E.; Beaney, T.; Hayhoe, B.W.J.; Car, J.; Clavería, A.; Collins, C.; Espitia, S.M.; et al. Features and Frequency of Use of Electronic Health Records in Primary Care across 20 Countries: A Cross-Sectional Study. Public Health 2024, 233, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSMA Annual Report 2023; 2024.

- UNESCO The UNESCO Courier Stories of Migration; 2021.

- Unwin, T.; Ghimire, A.; Yeoh, S.-G.; Lorini, M.R.; Harindranath, G.H. Uses of Digital Technologies by Nepali Migrants and Their Families. 2021.

- Benson, J.; Brand, T.; Christianson, L.; Lakeberg, M. Localisation of Digital Health Tools Used by Displaced Populations in Low and Middle-Income Settings: A Scoping Review and Critical Analysis of the Participation Revolution. Conflict and Health 2023, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Vijver, S.; Tensen, P.; Asiki, G.; Requena-Méndez, A.; Heidenrijk, M.; Stronks, K.; Cobelens, F.; Bont, J.; Agyemang, C. Digital Health for All: How Digital Health Could Reduce Inequality and Increase Universal Health Coverage. DIGITAL HEALTH 2023, 9, 20552076231185434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, H.; Ebrahim, S.; Ebrahim, H.; Bhaiwala, Z.; Chilazi, M. A Free, Open-Source, Offline Digital Health System for Refugee Care. JMIR Medical Informatics 2022, 10, e33848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenner, D.; Méndez, A.R.; Schillinger, S.; Val, E.; Wickramage, K. Health and Illness in Migrants and Refugees Arriving in Europe: Analysis of the Electronic Personal Health Record System. Journal of Travel Medicine 2022, 29, taac035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markle Foundation Connecting Americans to Their Healthcare: Final Report - Working Group on Policies for Electronic Information Sharing Between Doctors and Patients; 2004.

- Essén, A.; Scandurra, I.; Gerrits, R.; Humphrey, G.; Johansen, M.A.; Kierkegaard, P.; Koskinen, J.; Liaw, S.-T.; Odeh, S.; Ross, P.; et al. Patient Access to Electronic Health Records: Differences across Ten Countries. Health Policy and Technology 2018, 7, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, O.; Werner-Felmayer, G.; Siipi, H.; Frischhut, M.; Zullo, S.; Barteczko, U.; Øystein Ursin, L.; Linn, S.; Felzmann, H.; Krajnović, D.; et al. European Electronic Personal Health Records Initiatives and Vulnerable Migrants: A Need for Greater Ethical, Legal and Social Safeguards. Developing World Bioethics 2020, 20, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damen, D.J.; Schoonman, G.G.; Maat, B.; Habibović, M.; Krahmer, E.; Pauws, S. Patients Managing Their Medical Data in Personal Electronic Health Records: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2022, 24, e37783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brands, M.R.; Gouw, S.C.; Beestrum, M.; Cronin, R.M.; Fijnvandraat, K.; Badawy, S.M. Patient-Centered Digital Health Records and Their Effects on Health Outcomes: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2022, 24, e43086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlin, S.A.; Hanefeld, J.; Corte-Real, A.; da Cunha, P.R.; de Gruchy, T.; Manji, K.N.; Netto, G.; Nunes, T.; Şanlıer, İ.; Takian, A.; et al. Digital Solutions for Migrant and Refugee Health: A Framework for Analysis and Action. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe 2025, 50, 101190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buford, A.; Ashworth, H.C.; Ezzeddine, F.L.; Dada, S.; Nguyen, E.; Ebrahim, S.; Zhang, A.; Lebovic, J.; Hamvas, L.; Prokop, L.J.; et al. Systematic Review of Electronic Health Records to Manage Chronic Conditions among Displaced Populations. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, L.; Lavis, A.; Greenfield, S.; Boban, D.; Humphries, C.; Jose, P.; Jeemon, P.; Manaseki-Holland, S. Systematic Review on the Use of Patient-Held Health Records in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballout, G.; Al-Shorbaji, N.; Abu-Kishk, N.; Turki, Y.; Zeidan, W.; Seita, A. UNRWA’s Innovative e-Health for 5 Million Palestine Refugees in the Near East. BMJ Innovations 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, S.; Arnaout, N.E.; Faulkner, J.R.; Sayegh, M.H. Sijilli: A Mobile Electronic Health Records System for Refugees in Low-Resource Settings. The Lancet Global Health 2019, 7, e1168–e1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narla, N.P.; Surmeli, A.; Kivlehan, S.M. Agile Application of Digital Health Interventions during the COVID-19 Refugee Response. Ann Glob Health 86, 135. [CrossRef]

- Nasir, S.; Goto, R.; Kitamura, A.; Alafeef, S.; Ballout, G.; Hababeh, M.; Kiriya, J.; Seita, A.; Jimba, M. Dissemination and Implementation of the E-MCHHandbook, UNRWA’s Newly Released Maternal and Child Health Mobile Application: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, S.; El Arnaout, N.; Abdouni, L.; Jammoul, Z.; Hachach, N.; Dasgupta, A. Sijilli: A Scalable Model of Cloud-Based Electronic Health Records for Migrating Populations in Low-Resource Settings. J Med Internet Res 2020, 22, e18183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmeli, A.; Narla, N.P.; Shields, A.J.; Atun, R. Leveraging Mobile Applications in Humanitarian Crisis to Improve Health: A Case of Syrian Women and Children Refugees in Turkey. Journal of Global Health Reports 2020, 4, e2020099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.L.; Surmeli, A.; Hoeflin Hana, C.; Narla, N.P. Perceptions on a Mobile Health Intervention to Improve Maternal Child Health for Syrian Refugees in Turkey: Opportunities and Challenges for End-User Acceptability. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1025675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Alawa, J.; Ashworth, H.; Essar, M.Y. Innovation Is Needed in Creating Electronic Health Records for Humanitarian Crises and Displaced Populations. Front Digit Health 2022, 4, 939168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seita, A.; Ballout, G.; Albeik, S.; Salameh, Z.; Zeidan, W.; Shah, S.; Atallah, S.; Horino, M. Leveraging Digital Health Data to Transform the United Nations Systems for Palestine Refugees for the Post Pandemic Time. Health Systems & Reform 2024, 10, 2378505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HealthEmove Your Personal Health Record. Available online: https://healthemove.org (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- HERA Digital Health. Available online: https://heradigitalhealth.org/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- RedSafe, a Digital Humanitarian Platform. Available online: https://www.icrc.org/en/redsafe (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- 4th RedSafe Kiosk Opens. Available online: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/4th-redsafe-kiosk-opens-zimbabwe (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- JICA Jordan: UNRWA's electronic MCH Handbook application for Palestine refugees; 2017.

- My Personal Health Bank - Health Data Today Healthcare Tomorrow. Available online: https://www.mypersonalhealthbank.com (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- My Personal Health Bank Usage Statistics. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/my-personal-health-bank_patientempowerment-healthdata-mypersonalhealthbank-activity-6995336497310658560-tysJ/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Novel Measurements for Performance Improvement Challenge My Personal Health Bank. Available online: https://solve.mit.edu/solutions/63213 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- RedSafe – Apps no Google Play. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=org.icrc.dhp&hl=pt_PT (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Borsari, L.; Stancanelli, G.; Guarenti, L.; Grandi, T.; Leotta, S.; Barcellini, L.; Borella, P.; Benski, A.C. An Innovative Mobile Health System to Improve and Standardize Antenatal Care Among Underserved Communities: A Feasibility Study in an Italian Hosting Center for Asylum Seekers. J Immigrant Minority Health 2018, 20, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotherton, T.; Brotherton, S.; Ashworth, H.; Kadambi, A.; Ebrahim, H.; Ebrahim, S. Development of an Offline, Open-Source, Electronic Health Record System for Refugee Care. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossano, V.; Berni, T.R. and F. A HEALTHCARE SYSTEM TO SUPPORT WELL-BEING OF MIGRANTS: THE PROJECT PREVENZIONE 4.0.; 2020; pp. 355–358.

- Lyles, C.R.; Tieu, L.; Sarkar, U.; Kiyoi, S.; Sadasivaiah, S.; Hoskote, M.; Ratanawongsa, N.; Schillinger, D. A Randomized Trial to Train Vulnerable Primary Care Patients to Use a Patient Portal. J Am Board Fam Med 2019, 32, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, Y.S.; Laflamme, L.; Schmid, D.; El-Halabi, S.; Khdair, M.A.; Sengoelge, M.; Atkins, S.; Tahtamouni, M.; Derrough, T.; El-Khatib, Z. Children Immunization App (CImA) Among Syrian Refugees in Zaatari Camp, Jordan: Protocol for a Cluster Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial Intervention Study. JMIR Research Protocols 2019, 8, e13557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UCRAID (Ukrainian Citizen and Refugee Electronic Support in Respiratory Diseases, Allergy, Immunology and Dermatology) Action Plan - Bousquet - 2023 - Allergy - Wiley Online Library Available online:. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/all.15855 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Salah, A.; Alobid, S.; Jalalzai, S.; Junger, D.; Burgert, O. Univie: An App for Managing Digital Health Data of Refugees. In Digital Health and Informatics Innovations for Sustainable Health Care Systems; IOS Press, 2024; pp. 195–199.

- The Palestinian Ministry of Health, K. Overview of the MCHHB in Palestine; 2012.

- Tensen, P.; van Dormolen, S.; van de Vijver, S.J.M.; van de Pavert, M.L.; Agyemang, C.O. Healthcare Providers Intentions to Use an Electronic Personal Health Record for Undocumented Migrants: A Qualitative Exploration Study in The Netherlands. Global Public Health 2025, 20, 2445840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Building Health Systems That Are Inclusive for Refugees and Migrants. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/activities/building-health-systems-that-are-inclusive-for-refugees-and-migrants (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Bock, J.G.; Haque, Z.; McMahon, K.A. Displaced and Dismayed: How ICTs Are Helping Refugees and Migrants, and How We Can Do Better. Information Technology for Development 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, I.; Scheermesser, M.; Spiess, M.R.; Schulze, C.; Händler-Schuster, D.; Pehlke-Milde, J. Digital Health for Migrants, Ethnic and Cultural Minorities and the Role of Participatory Development: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 6962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.; Early, J.; Gordon-Dseagu, V.; Mata, T.; Nieto, C. Promoting Culturally Tailored mHealth: A Scoping Review of Mobile Health Interventions in Latinx Communities. J Immigrant Minority Health 2021, 23, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Yoon, J.; Park, N.S. Source of Health Information and Unmet Healthcare Needs in Asian Americans. Journal of Health Communication 2018, 23, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaihlanen, A.-M.; Virtanen, L.; Buchert, U.; Safarov, N.; Valkonen, P.; Hietapakka, L.; Hörhammer, I.; Kujala, S.; Kouvonen, A.; Heponiemi, T. Towards Digital Health Equity - a Qualitative Study of the Challenges Experienced by Vulnerable Groups in Using Digital Health Services in the COVID-19 Era. BMC Health Services Research 2022, 22, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, A.; Natari, R.B.; Jimmy; Hall, B. J. Digital Health Applications in Mental Health Care for Immigrants and Refugees: A Rapid Review. Telemedicine and e-Health 2021, 27, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, L.; Talevski, J.; Fatehi, F.; Beauchamp, A. Barriers to and Facilitators of Digital Health Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations: Qualitative Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2023, 25, e42719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, A. Technology Can Be Transformative for Refugees, but It Can Also Hold Them Back Available online:. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/digital-technology-refugees (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Taylor, D. Home Office Illegally Seized Phones of 2,000 Asylum Seekers, Court Rules. The Guardian 2022.

- Tondo, L.; Hawkins, A. Croatian Police Accused of Burning Asylum Seekers’ Phones and Passports. The Guardian 2024.

- Europe Migrants: Austria to Seize Migrants’ Phones in Asylum Clampdown 2018.

- Mancini, T.; Sibilla, F.; Argiropoulos, D.; Rossi, M.; Everri, M. The Opportunities and Risks of Mobile Phones for Refugees’ Experience: A Scoping Review. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0225684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Directorate General for Parliamentary Research Services. Blockchain and the General Data Protection Regulation: Can Distributed Ledgers Be Squared with European Data Protection Law? Publications Office: LU, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Authorship (year) | Title | Publication | Methodology | EPHR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ballout, G. et al (2018) [27] | UNRWA’s innovative e-Health for 5 million Palestine refugees in the Near East | Original razmakarticle | razmakNA | e-MCH razmakHandbook |

| 2 | Saleh, S. et al (2019) [28] | razmakSijilli: a mobile electronic health records system for refugees in low-resource settings | Comment | NA | Sijilli |

| 3 | Narla, N. et al (2020) [29] | razmakAgile application of digital health interventions during the covid-19 refugee response | Viewpoint | Exploratory razmakevaluation | HERA |

| 4 | Nasir, S. et al (2020) [30] | razmakDissemination and implementation of the e-MCH Handbook, UNRWA's newly released maternal and child health mobile application: a cross-sectional study | Original razmakarticle | Cross-sectional study design | e-MCH razmakHandbook |

| 5 | Saleh, S. et al (2020) [31] | razmakSijilli: A Scalable Model of Cloud-Based Electronic Health Records for Migrating Populations in Low-Resource Settingsrazmak | Viewpoint | NA | Sijilli |

| 6 | Surmeli, A. et al (2020) [32] | razmakLeveraging mobile applications in humanitarian crisis to improve health: a case of Syrian women and children refugees in Turkey | Report | NA | HERA |

| 7 | Meyer, C. et al (2022) [33] | razmakPerceptions on a mobile health intervention to improve maternal child health for Syrian refugees in Turkey: Opportunities and challenges for end-user acceptability | Original razmakarticle | Qualitative study | HERA |

| 8 | Shrestha, A. et al (2022) [34] | Innovation is needed in creating electronic health records for humanitarian crises and displaced populations | Opinion paper | NA | Sijilli |

| 9 | Vijver, S. et al (2023) [16] | Digital health for all: How digital health could reduce inequality and increase universal health coverage | Viewpoint | NA | HealthEmove |

| 10 | Seita, A. et al (2024) [35] | Leveraging Digital Health Data to Transform the United Nations Systems for Palestine Refugees for the Post Pandemic Time | Original razmakarticle | Qualitative study | e-MCH razmakHandbook |

| No. | Authorship (month, year) | Title | Publication type | EPHR tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HealthEmove (n.d.) [36] | Your Personal Health Record | Official website HealthEmove | HealthEmove |

| 2 | Hera Digital Health (n.d.) [37] | HERA Digital Health | Official website HERA Digital Health | HERA |

| 3 | ICRC (n.d.) [38] | RedSafe, a Digital Humanitarian Platform | Official website ICRC | RedSafe |

| 4 | ICRC (February, 2022) [39] | 4th RedSafe kiosk opens in Zimbabwe | News release on the official website ICRC | RedSafe |

| 5 | JICA (August, 2017) [40] | Jordan: UNRWA’s electronic MCH Handbook application for Palestine Refugees (Issue 20) | Technical brief | e-MCH Handbook |

| 6 | My Personal Health Bank (n.d.) [41] | My Personal Health Bank | Official website of My Personal Health Bank | My Personal Health Bank |

| 7 | My Personal Health Bank (n.d.) [42] | Usage statistics | LinkedIn post | My Personal Health Bank |

| 8 | MIT-solve (August, 2022) [43] | Novel measurement for performance razmakimprovement challenge My Personal Health Bank | Application MIT-solve | My Personal Health Bank |

| 9 | Play Store (May, 2024) [44] | Play Store: RedSafe | App download | RedSafe |

| ToolrazmakName | Initiated/owned by | Mobile razmakpopulation | Current countries | Stage of razmakdevelopment | Number razmakof users (month, year) a | Languages | Tool description | Application type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tools from the scientific literature | ||||||||

| e-MCH razmakHandbook | UNRWA and JICA# | Palestine refugees# razmak | Jordan, Gaza, Lebanon, Westbank, Syria# | Application since 2017# | 254,586 registered users (July 2023) and 22,000 active users (June, 2023)# | Arabic# | mHealth application with PHR | Smartphone app# |

| HERA | HERA Digital Health& | Syrian refugees# | Turkey# | Application since 2018. razmakIn 2020 field tests were performed# | >3000 refugee families in Turkish pilot study (n.d.)& | Arabic, Turkish, English#, Pashto and Dari& | Humanitarian razmakplatform with razmak‘digital vault’ | Smartphone and web-app# |

| Sijilli | American University of Beirut and Epic Health Systems# | Syrian refugees# | Lebanon# | Launched 2018# | >10 000 users (2022)# | English and Arabic# | EHR with user-portal and USB-stick | N/A |

| HealthEmove | Initiative: Amsterdam Health & Technology Institute; software: Patients Know Best& | Refugees# and razmak People on the move& | Netherlands& | Application since 2023# | N/A | 22 languages& | EPHR | Web-app& |

| Tools from the grey literature | ||||||||

| My personal Health Bank | University of Southern Denmark, University of Dodoma and Muhimbili University& | People in developing countries and people on the move& | Tanzania& | Feasibility study from Jun 2022 until Feb 2023. | 4969 patients included (June, 2022) & (31). | English, Kiswahili& | EPHR | Web-app& |

| RedSafe | International Committee of the Red Cross& | People affected by conflict, migration and other humanitarian crisis& | Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Mexico, USA, Costa Rica, Panama, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, Eswatini, Lesotho, Switzerland, Zambia*& | Launched in May 2021& | 32000 downloads razmak(February, 2022)& | English, Spanish and Portuguese& | Humanitarian razmakplatform with razmak‘digital vault’ | Smartphone and web-app& |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).