1. Introduction

Older adults frequently experience restricted mobility due to the aging process and the progression of medical conditions, leading to prolonged bed rest [

1]. Because extended periods spent out of bed are strongly associated with improved activities of daily living, wheelchairs are often used to assist with transfers from bed to a seated position [

1,

2]. In Japan, wheelchairs are provided as facility equipment in hospitals and eldercare institutions, and are also accessible at home through long-term care insurance services for assistive devices [

3,

4,

5].

Nevertheless, although wheelchairs facilitate transfers out of bed, musculoskeletal pain and discomfort arising from wheelchair use have been reported [

6,

7]. Moreover, many wheelchair seats and backrests are sling-type, consisting of fabric or belts, resulting in sagging and suboptimal seated posture [

8]. When users remain seated in a wheelchair for extended periods, the risk of developing pressure injuries in the seated area increases. Consequently, guidelines advise using wheelchair cushions with pressure redistribution capabilities to prevent pressure injuries [

9]. However, it has been noted that placing a cushion on a sling seat compromises the effectiveness of the cushion’s materials [

10]. Additionally, pressure injuries are induced not only by vertical pressure but also by friction and shear forces. Occupying a sagging seat encourages posterior or lateral pelvic tilt, thereby imposing uneven loads on the ischial tuberosities [

8]. This impairs postural stability and can alter pressure redistribution [

11,

12], while increasing shear [

13], ultimately elevating the risk of pressure injury formation.

Regarding sling seats and their associated sagging, Harms et al. [

14] demonstrated that both healthy individuals and those with disabilities exhibit lumbar kyphosis and posterior pelvic tilt when seated on a sling seat, thereby compromising posture. As a countermeasure, Kamegaya et al. [

15] placed a wooden insert panel on a sling seat to correct sagging, resulting in marked decreases in pelvic tilt and difficulty with forward reaching; however, the peak pressure over the ischial region tended to increase. Conversely, Shin et al. [

16] reported reduced pressure when using a urethane pad designed to offload the ischial area, and Yoshikawa et al. [

17] observed similar results. While a few studies have investigated how sling seats affect posture and seating pressure, the effect of seat sagging on shear forces has yet to be explored.

Thus, this study investigated how wheelchair seat sagging affects pressure, shear, and posture to inform pressure injury prevention strategies. Our overarching goal is to facilitate pressure injury prevention for older adults who depend on wheelchairs. However, controlling variables such as body size, posture, and physical conditions (e.g., contractures or deformities) in older populations is challenging. Therefore, we recruited healthy adults to ascertain how correcting seat sagging influences pressure, shear, and posture, and to clarify aspects of these underlying mechanisms.

2. Methods

1) Research Design

The research design was a crossover comparison study of healthy subjects.

2) Participants

This study included 24 healthy adults aged 18 years or older. Each participant’s height, weight, sitting hip width, buttock–popliteal length, sitting elbow height, sitting axillary height, and lower leg length were measured. To minimize discrepancies related to wheelchair fit, only individuals whose sitting hip width ranged from 34–40 cm and whose buttock–popliteal length ranged from 41–49 cm were included. Exclusion criteria encompassed a sitting hip width below 33 cm or above 41 cm, a buttock–popliteal length below 40 cm or above 50 cm, or any history of orthopedic disorders affecting the lumbar region or lower limbs. The sample size was determined based on a previous study [

18], which reported mean and standard deviation values for seat interface pressure (experimental group: 25.9 ± 4.7, control group: 23.4 ± 5.4), yielding an effect size of roughly 0.5. Using G*Power for a t-test with an effect size of 0.5, an alpha of 0.05, and a power of 0.8, we derived a sample size of 21. To accommodate potential attrition, 24 participants were ultimately recruited.

3) Equipment

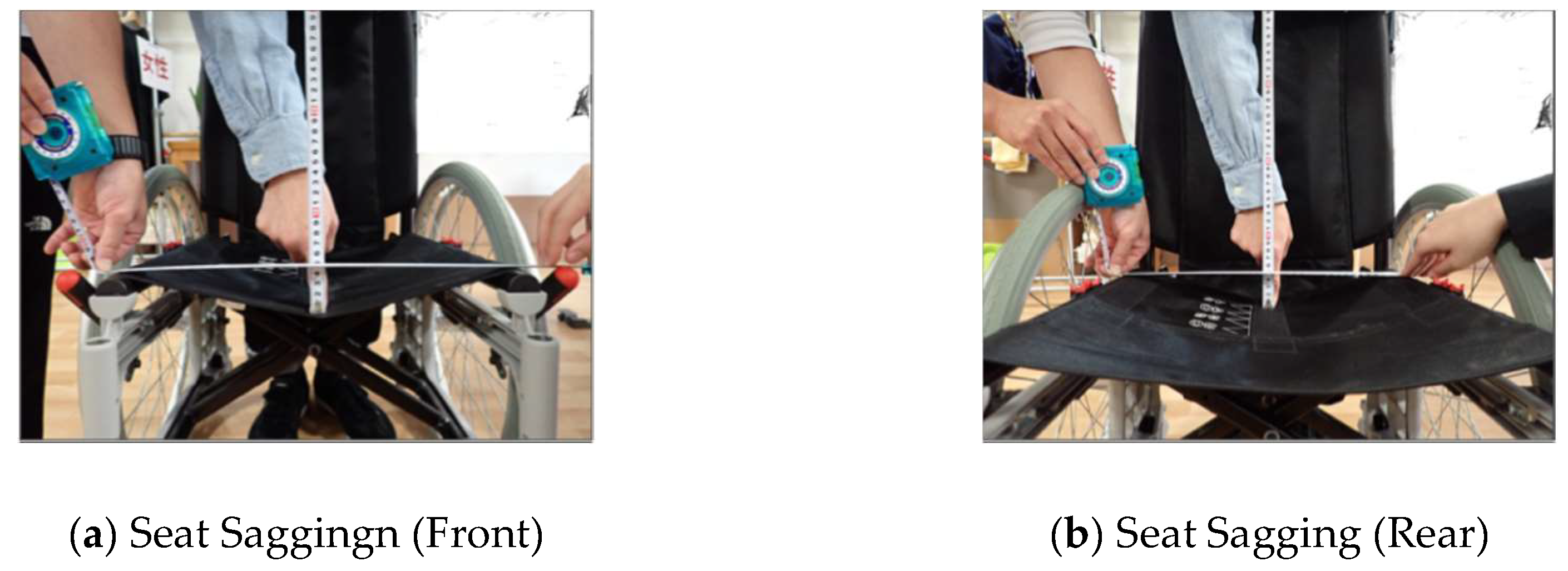

An adjustable “Revo” wheelchair (Rack Healthcare, Osaka, Japan) was used for data collection. The backrest height was 40 cm, seat depth was 40 cm, seat width was 40 cm, and the seat angle was 3.85°. Seat sagging was defined by stretching a straight reference line between the two seat supports, then measuring the vertical displacement (sag) occurring when the central areas of the sling seat at both the front and rear were pressed downward. In the wheelchair employed, a deflection of 5 cm was noted at both the front and rear (

Figure 1). A flat urethane Moderato cushion (Rack Healthcare, Osaka, Japan), measuring 40 × 40 × 6 cm, served as the wheelchair cushion.

A commercially available Kiso seat base (Tatsuno Cork Industry, Tatsuno, Japan), measuring 40 × 40 × 3.5 cm, was used to correct seat deflection.

Seat pressure was measured using CONFORMat (NITTA Inc., Osaka, Japan). The sensor sheet’s specifications included dimensions of 471 mm (length) × 471 mm (width), 1024 sensors (32 rows × 32 columns), a thickness of 1.8 mm, and a resolution of 14.7 mm.

Shear force was assessed using “iShear” (Vicair B.V., Wormer, the Netherlands), with dimensions of 27 × 690 × 615 mm and a load capacity of 45–120 kg.

Posture was evaluated using TSND151 accelerometers (ATR-Promotions, Kyoto, Japan) sampled at 5 Hz. The raw acceleration data were converted to tilt angles using Data Converter software (ATR-Promotions, Kyoto, Japan). A single examiner attached accelerometers to each participant’s forehead, sternum, and both iliac crests using hook-and-loop straps.

Figure 1.

Measurement of Wheelchair Seat Sagging. (a) measures the Seat Sagging at the front of the seat, and (b) measures the Seat Sagging at the rear of the seat. The wheelchair seat exhibited 5 cm of Seat Sagging at both the front and the rear.

Figure 1.

Measurement of Wheelchair Seat Sagging. (a) measures the Seat Sagging at the front of the seat, and (b) measures the Seat Sagging at the rear of the seat. The wheelchair seat exhibited 5 cm of Seat Sagging at both the front and the rear.

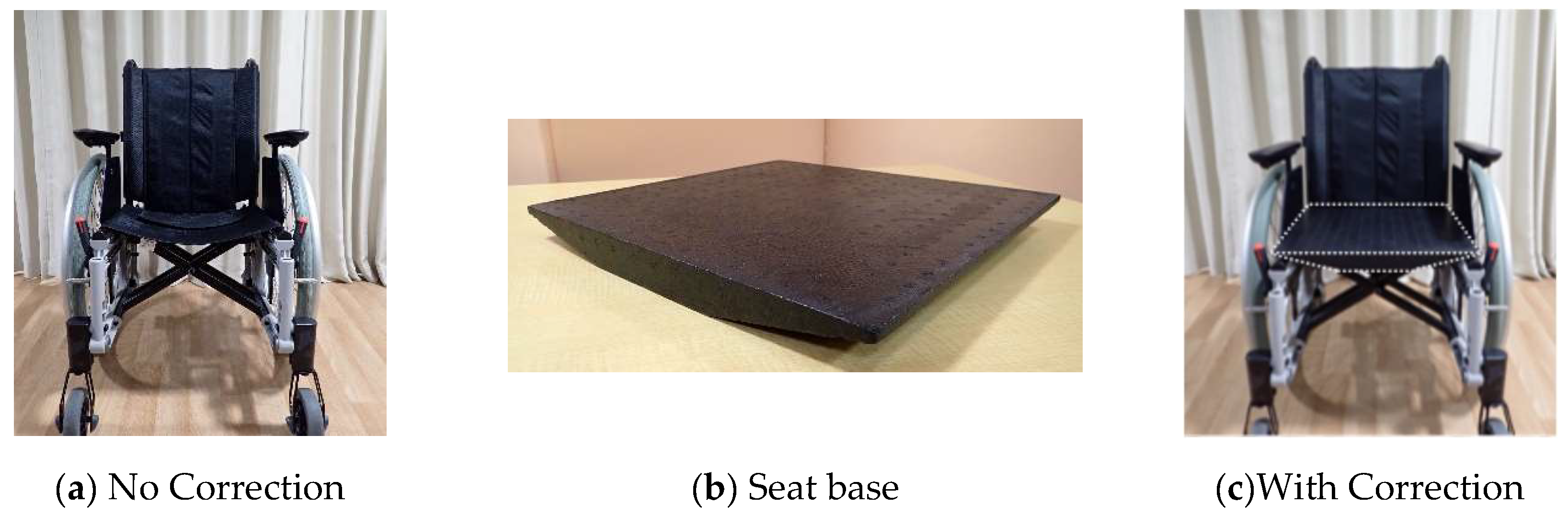

Figure 2.

When correcting sling seat sag using the seat base and not used. (a) is the state where the Seat Sagging of the seat is not corrected (No Correction), (b) is the seat base used to correct the Seat Sagging, and (c) is the state where the Seat Sagging is corrected using the seat base (With Correction).

Figure 2.

When correcting sling seat sag using the seat base and not used. (a) is the state where the Seat Sagging of the seat is not corrected (No Correction), (b) is the seat base used to correct the Seat Sagging, and (c) is the state where the Seat Sagging is corrected using the seat base (With Correction).

Figure 1.

Method for Measuring Slide. All photographs included markers at the wheelchair axle and the patella. Images were imported into ImageJ, and distances were adjusted according to the wheel’s inch size. For the analysis, the distance between the wheelchair axle and the patella was measured using ImageJ.

Figure 1.

Method for Measuring Slide. All photographs included markers at the wheelchair axle and the patella. Images were imported into ImageJ, and distances were adjusted according to the wheel’s inch size. For the analysis, the distance between the wheelchair axle and the patella was measured using ImageJ.

4) Measurement Procedure

For this study, the arm supports and foot supports were adjusted in accordance with each participant’s sitting axillary height and lower leg length under each measurement condition. During measurements, a plain urethane wheelchair cushion (without contour) was placed on the seat. When sling seat sag was corrected using the seat base, the condition was labeled “With Correction,” and when no seat base was used, it was labeled “No Correction.” Under these two conditions, seat pressure and shear force were recorded (

Figure 2). Additionally, to evaluate body displacement, photographs were captured from the sagittal plane at both the start and end of each measurement (

Figure 3). Moreover, to assess changes in posture, accelerometers were attached to the participant’s forehead, sternum, and both iliac crests.

The measurement order was randomized by an envelope method. Participants were instructed to relax as much as possible and to avoid intentional movement or repositioning during each 10-minute measurement session.

5) Data Measurement and Analysis

(1) Ischial Pressure: Measurement and Analysis

Interface pressure was assessed using CONFORMat (NITTA Inc., Osaka, Japan). After participants were seated in the wheelchair and their posture stabilized (approximately 1 minute), pressure recording began. Pressure was continuously monitored for 10 minutes. For analysis, the highest average value derived from the peak pressure cell and its adjacent three cells (four cells in total) at the 10-minute mark was selected as the peak pressure index (PPI) [

19,

20].

(2) Shear Force and slide: Measurement and Analysis

Shear force was recorded using iShear (Vicair B.V., Wormer, the Netherlands). First, participants sat in the wheelchair without the cushion to establish a baseline shear force value. The wheelchair cushion and seat base (if used) were then installed, and participants were reseated. After a 1-minute stabilization period, shear force was recorded for 10 minutes. The maximum shear force noted during this interval was normalized by dividing by the baseline value.

Slide was assessed from sagittal-plane photographs captured at the beginning and end of the measurement period. Each photograph included markers placed on the wheelchair axle and on the participant’s patella. The images were transferred to ImageJ, and distances were scaled according to the known diameter of the wheelchair wheel. The distance between the wheelchair axle and the participant’s patella was then measured in ImageJ (

Figure 3). Slide was computed by subtracting the initial distance measured at the start from the final distance measured at the end of the session.

(3) Posture: Measurement and Analysis

Wheelchair-seated posture was quantified using TSND151 accelerometers (ATR-Promotions, Kyoto, Japan). The same examiner located anatomical landmarks and secured the sensors with hook-and-loop straps at the center of the forehead, over the manubrium, and on both iliac crests. Tilt angles were defined relative to the participant’s initial posture, with forward tilt designated as positive and backward tilt as negative. The angle data used for analysis were the 1-second averages at 1 minute (start of posture measurement) and 10 minutes (end of posture measurement). Postural change was determined by subtracting the initial angle from the final angle.

6) Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using EZR [

21]. The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of PPI (ischial pressure), shear force, slide, and angle data. For normally distributed data, a paired t-test was used; otherwise, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied. Subgroup analyses were performed for participants who exhibited notably elevated shear force. For any variable demonstrating statistical significance, correlations with height, weight, and BMI were explored. The significance level was set at 5%.

7) Ethical Considerations

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Nara Gakuen University (approval number: 5-002). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All data were managed to preserve anonymity, and participant privacy was rigorously protected.

3. Results

Of the 24 participants, 2 were excluded because their sitting hip width was 33 cm or less, leaving a final total of 22 participants (11 men and 11 women). Their mean height was 162.3 ± 6.6 cm, mean weight was 59.3 ± 13 kg, and mean BMI was 22.3 ± 3.8 (

Table 1). With respect to body dimensions, the average sitting hip width was 35.7 ± 1.8 cm, buttock–popliteal length was 44.0 ± 2.8 cm, sitting lower leg length was 41.5 ± 2.3 cm, sitting elbow height was 22.9 ± 2.8 cm, and sitting axillary height was 41.7 ± 6.7 cm (

Table 1). The Shapiro-Wilk test revealed that the PPI, shear force, and slide data did not significantly deviate from normality (p ≧ 0.05), whereas tilt angle change data did (p < 0.05).

1) Ischial Pressure

The PPI on the ischial was 65.4 ± 39.9 mmHg in the No Correction condition and 68.1 ± 38.4 mmHg in the With Correction condition, with no statistically significant difference between them (

Table 2).

2) Shear Force and slide

In the No Correction condition, shear force was 22.6 ± 28.3 N/N, whereas it was 13.0 ± 16.7 N/N in the With Correction condition, indicating a significant reduction in shear force with seat base correction (p < 0.05,

Table 2). Slide in the No Correction condition (0.6 ± 0.3 cm) was also significantly greater than in the With Correction condition (0.3 ± 0.2 cm) (p < 0.05,

Table 2). An examination of shear force correlations with height, weight, and BMI showed no significant relationships in either condition (No Correction: r = 0.18, 0.06, 0.17; With Correction: r = 0.17, 0.02, 0.15) (

Table 3). A subgroup analysis was performed for participants who exhibited relatively high shear force (≥5 N, n = 12). In this subgroup, shear force in the No Correction condition was 39.6 ± 29.0 N/N, whereas it was 21.9 ± 17.7 N/N with correction, showing a significant decrease (p < 0.05,

Table 4). Correlations between shear force and height, weight, or BMI in this subgroup were also nonsignificant (No Correction: r = 0.25, 0.11, 0.06; With Correction: r = 0.18, 0.08, 0.05) (

Table 5).

3) Postural Changes

Changes in the angles of the head, chest, left iliac crest, and right iliac crest (expressed as median [interquartile range]) were assessed. The head angle changes were –0.145 [–3.82–9.61] in the No Correction condition and –1.075 [–5.37–7.96] in the With Correction condition. The chest angle changes were 0.19 [–4.25–8.13] under No Correction and –0.08 [–5.93–21.26] under With Correction. For the left iliac crest, the change was –0.16 [–1.37–1.18] in the No Correction condition and –0.74 [–5.52–5.52] in the With Correction condition. For the right iliac crest, the change was –0.24 [–1.36–0.81] under No Correction and –1.27 [–8.62–2.58] under With Correction. Although there were no significant differences between the two conditions, there was a tendency toward greater postural variation under With Correction (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

This study examined how correcting or not correcting wheelchair seat sagging influences ischial pressure, shear force/slide, and postural adjustments. The results revealed no significant differences in ischial pressure between the No Correction and With Correction conditions; however, shear force and slide were markedly reduced under the With Correction condition. Postural changes in head, thoracic, or pelvic angles did not differ significantly between the two conditions, although there was a tendency for smaller postural fluctuations under No Correction.

In wheelchair seating, tissue breakdown is generally believed to occur when high pressures are applied to the seat surface [

22], although no definitive cutoff value has been established [

11]. Brienza et al. [

22] examined seat interface pressure in individuals aged 65 and older who use wheelchairs in nursing care settings and have Braden scores of 18 or lower; their findings demonstrated that an ischial PPI of 70 ± 16 mmHg did not lead to pressure injury formation. In the present study, mean ischial pressure ranged from approximately 65 to 70 mmHg under both conditions, suggesting a typical value for the ischial region. Linder-Ganz et al. [

23] noted that skeletal muscle cell death ensues after at least two hours of exposure to pressures exceeding 68 mmHg, and clinical guidelines [

9] recommend performing weight shifts every 15 minutes to prevent pressure injuries in wheelchair users. Because the measurement period in this study lasted only 10 minutes, no weight shifting was required. Nevertheless, since pressures within this range can pose a risk over extended periods, regular weight shifts remain advisable, irrespective of the absolute interface pressure level.

In this study, seat sagging was corrected by employing insert panels composed of polyethylene and polystyrene, which did not substantially alter ischial pressures relative to the no-correction condition. Yoshikawa et al. [

17] demonstrated that soft, contoured urethane inserts lowered ischial pressure when combined with an air cushion, also showing a tendency for reduced pressure with urethane or gel materials. Likewise, Shin et al. [

16] reported that a urethane pad specifically designed to offload the ischial region effectively reduced pressure. In contrast, Kamegaya et al. [

15] noted that a wooden insert panel heightened peak pressure. Collectively, these findings suggest that the impact of seat sagging correction on pressure may vary according to the material and contour of the insert panel, thereby warranting further investigation.

Additionally, it is acknowledged that the formation of pressure injuries is influenced not only by vertical pressure but also by friction and shear forces in the horizontal plane [

9]. When an individual sits on a sling seat, lumbar kyphosis and posterior pelvic tilt may arise, thereby augmenting the load on the backrest and amplifying the forward-sliding force on the buttocks [

8,

13,

14,

24]. In this study, we assessed how shear force and slide vary based on whether frontal-plane sag in the sling seat is corrected. Our findings revealed that both shear force and slide were substantially higher when the seat was not corrected. In a wheelchair-seated posture, the seat surface and backrest collectively support the user’s body weight; however, the buttocks bear the brunt of the load, resulting in concentrated pressure and stress within this soft tissue region [

25]. When frontal-plane sagging of the sling seat causes the pelvis to tilt to one side, the depressed portion of the sling also shifts in that direction, thereby increasing pelvic sway in the frontal plane [

8]. The instability arising from a lack of correction presumably promotes shear; in an effort to mitigate this, the user’s postural control system attempts to minimize sway by shifting the pelvis posteriorly. Consequently, the load on the backrest escalates, encouraging anterior sliding of the buttocks [

13,

24]. An increase in shear not only elevates the risk of deep tissue injury [

26], but the coexistence of pressure and shear has also been shown to constrict blood vessels, triggering ischemic conditions [

27,

28]. Although no significant difference in ischial pressure was identified in this study, the heightened shear force and slide under the no-correction condition suggest that ischemic states in soft tissues could be exacerbated, thereby increasing the likelihood of pressure injuries.

Nonetheless, despite the substantial difference in shear force and slide, no discernible differences were observed in the measured postural changes, irrespective of seat correction. Earlier studies have indicated that posterior pelvic tilt generates shear force [

13,

24] and that seat correction can influence lumbar alignment [

14]. Hence, we hypothesized that seat correction would lessen postural changes and diminish shear force production. In practice, although seat correction considerably lowered shear force, it did not significantly influence postural changes. Without correction, from the moment they sat on the sling seat, they leaned back against the back support as previously mentioned, and their posture transitioned to one characterized by lumbar lordosis and pelvic tilt [

14], and because it was fixed, it is believed that minimal postural change occurred. Although previous research has established that posterior pelvic tilt can engender shear force [

13,

24], our results indicate that elevated shear force at the seat does not necessarily present as a visible postural change. Moreover, in this study, even though the head and trunk posture were not considerably distorted, shear force and slide increased, suggesting that in cases where the wheelchair seat deflection is not corrected, shear stress is induced in the soft tissue surrounding the ischium, even without overt postural distortion. This observation is particularly alarming because it implies a heightened risk of developing deep tissue injury [

29]. Because the participants were healthy and tested for only 10 minutes, no such injuries ensued. Nevertheless, these findings underscore the necessity of vigilance in older adults who spend prolonged periods in wheelchairs and are unable to reposition themselves, as well as in individuals with diminished sensation in the buttocks.

A subgroup analysis examining the relationships between shear force and height, weight, and BMI revealed no significant correlations in any condition, indicating that these anthropometric characteristics are not the principal determinants of shear force. Instead, seat sagging in sling chairs likely fosters posterior pelvic tilt and exacerbates shear force.

One limitation of this study is the absence of standardized methodologies for accurately measuring interface pressure, shear force, and posture in a sagging sling seat. Additionally, all participants were healthy adults, whereas older adults frequently exhibit altered load-bearing patterns [

29], as well as differences in muscle mass and skin integrity. Future research should therefore focus on older individuals who rely on wheelchairs for daily mobility to corroborate these findings. Moreover, additional investigations are required to ascertain the most appropriate materials for insert panels used in correcting sling seat sagging.