Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

26 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discutions

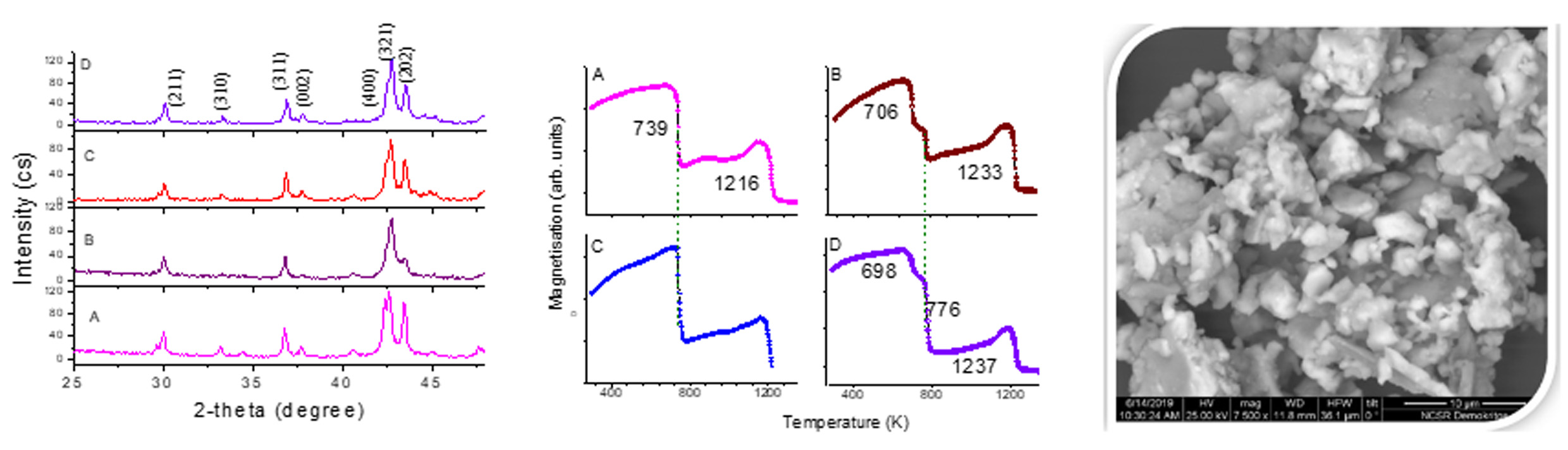

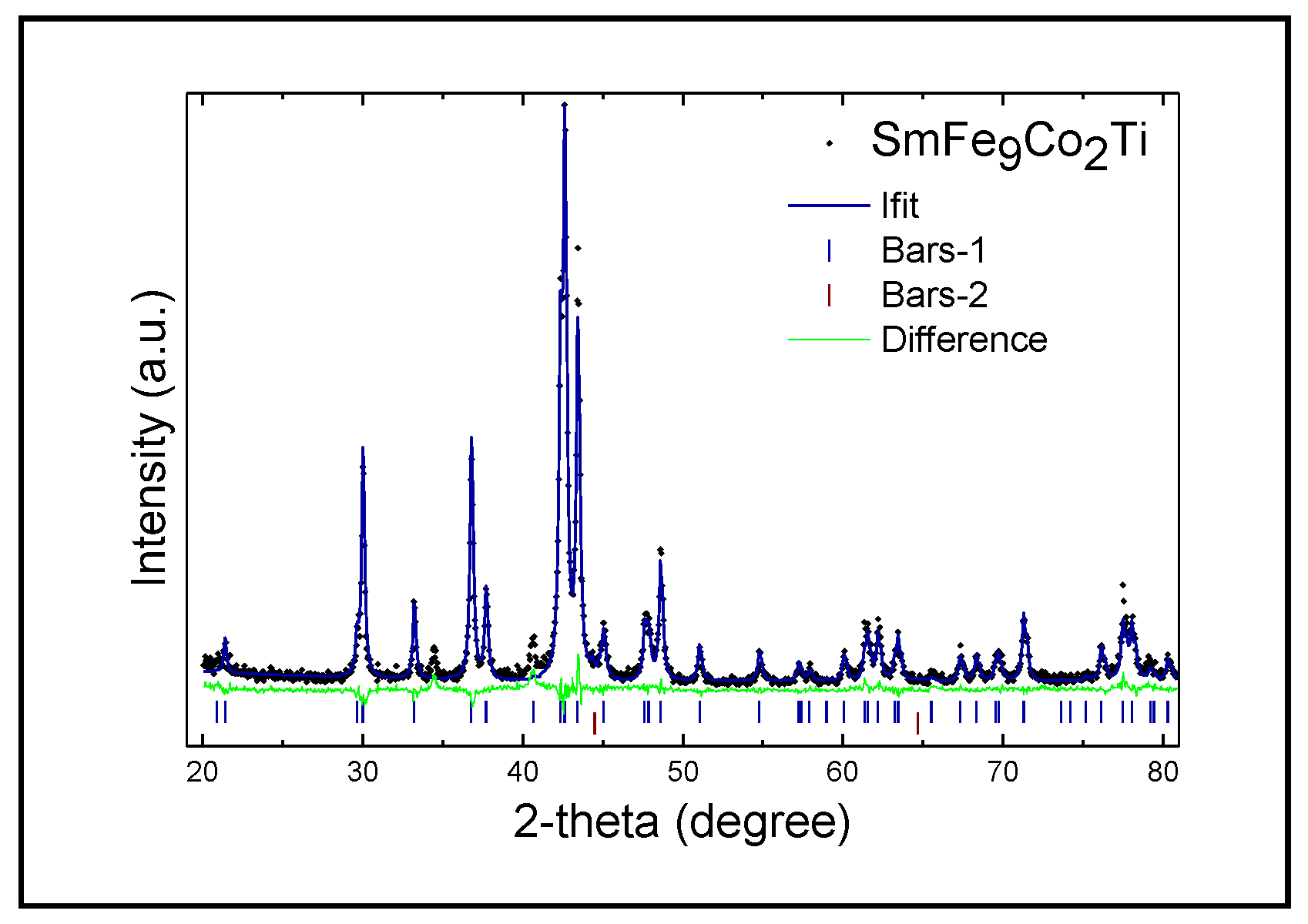

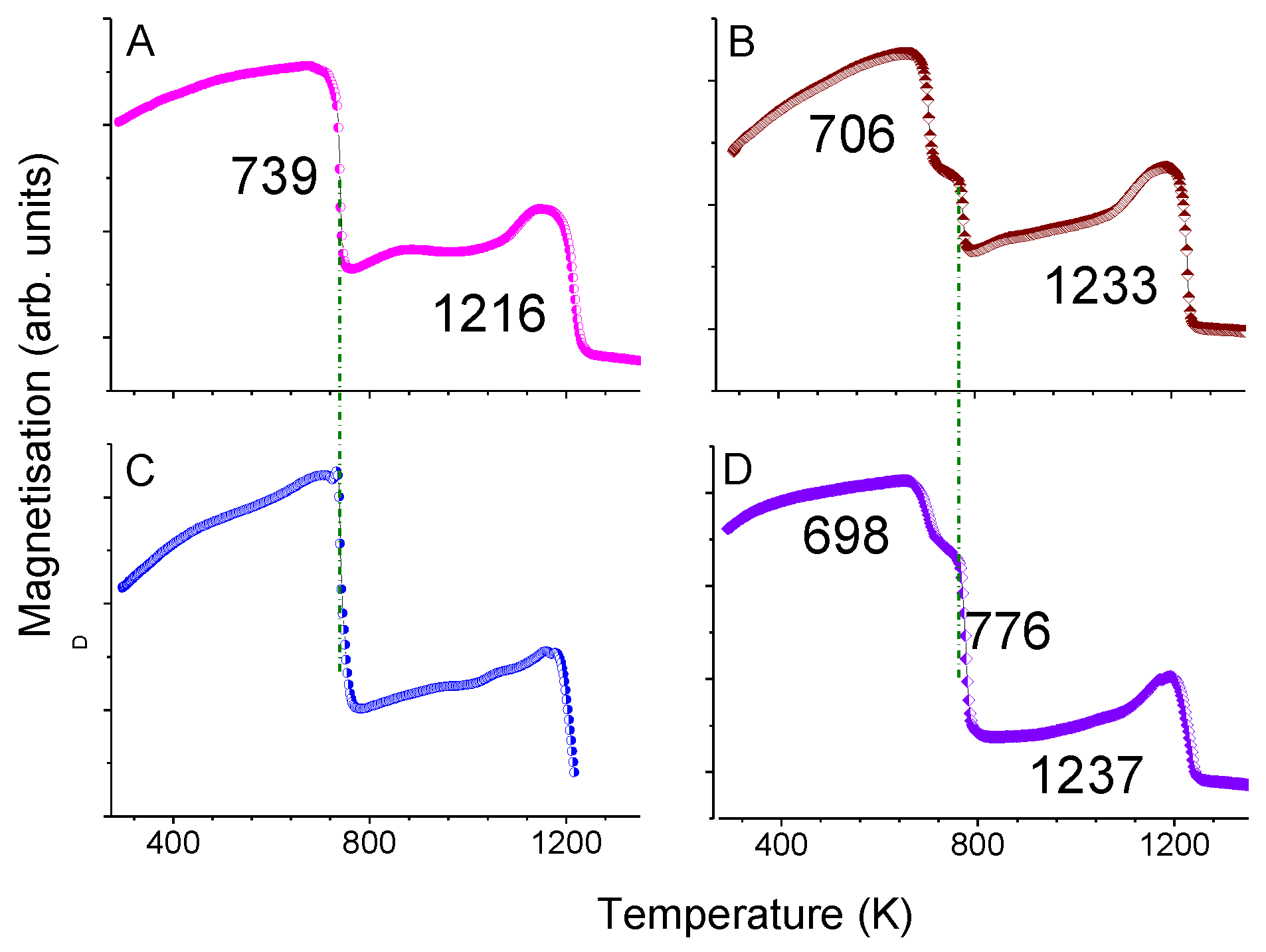

3.1. Structure of Arc-Melting Alloys

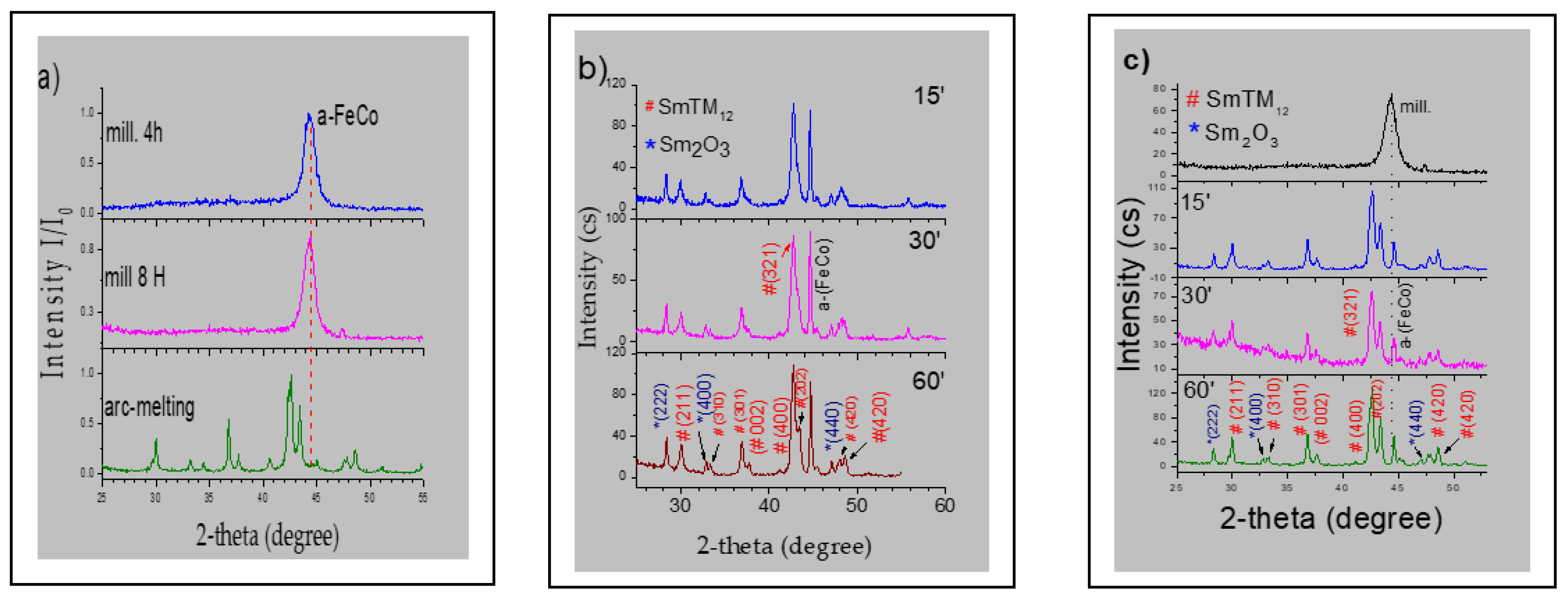

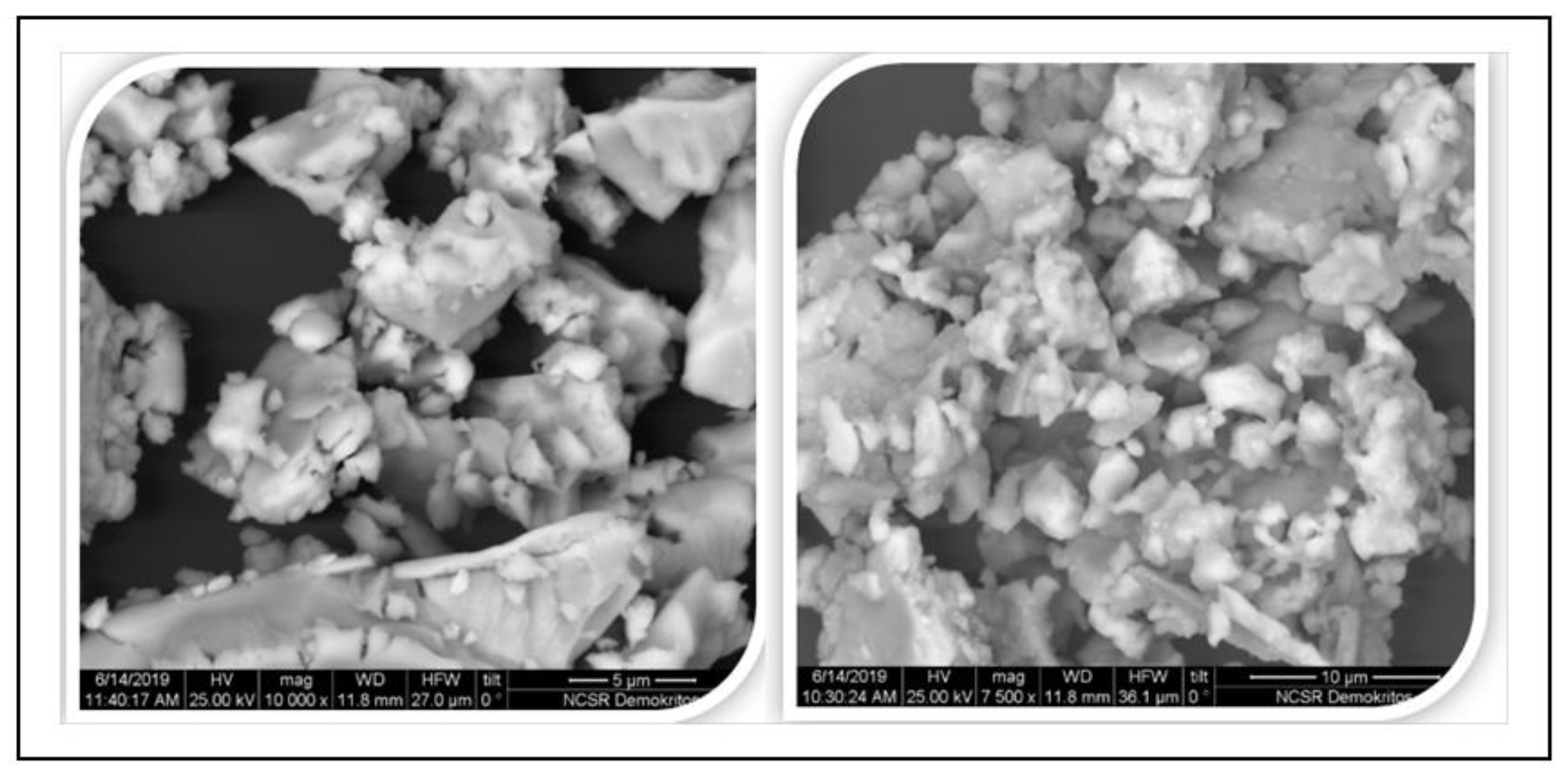

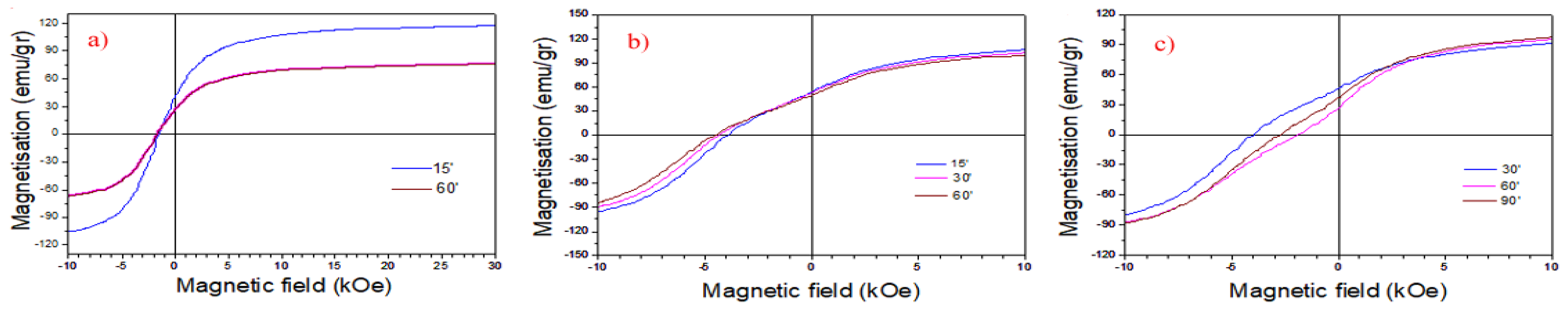

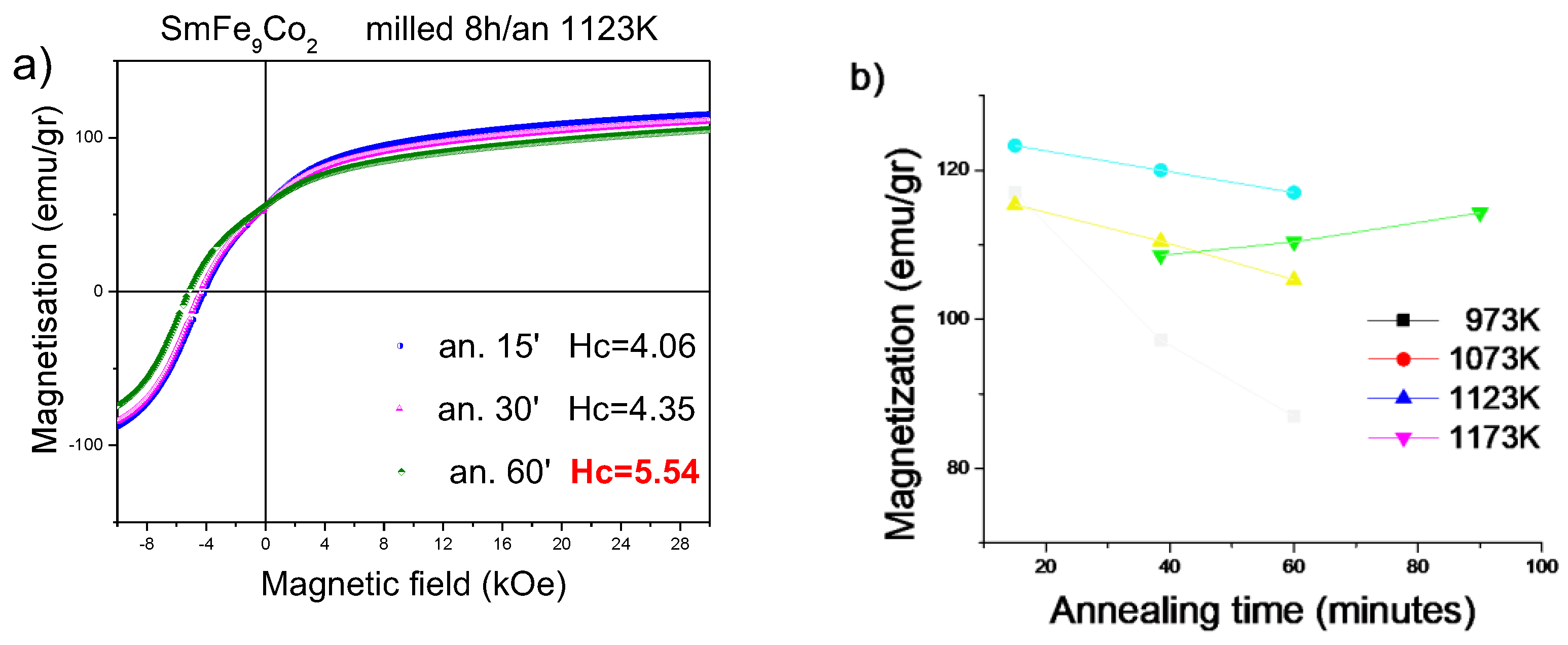

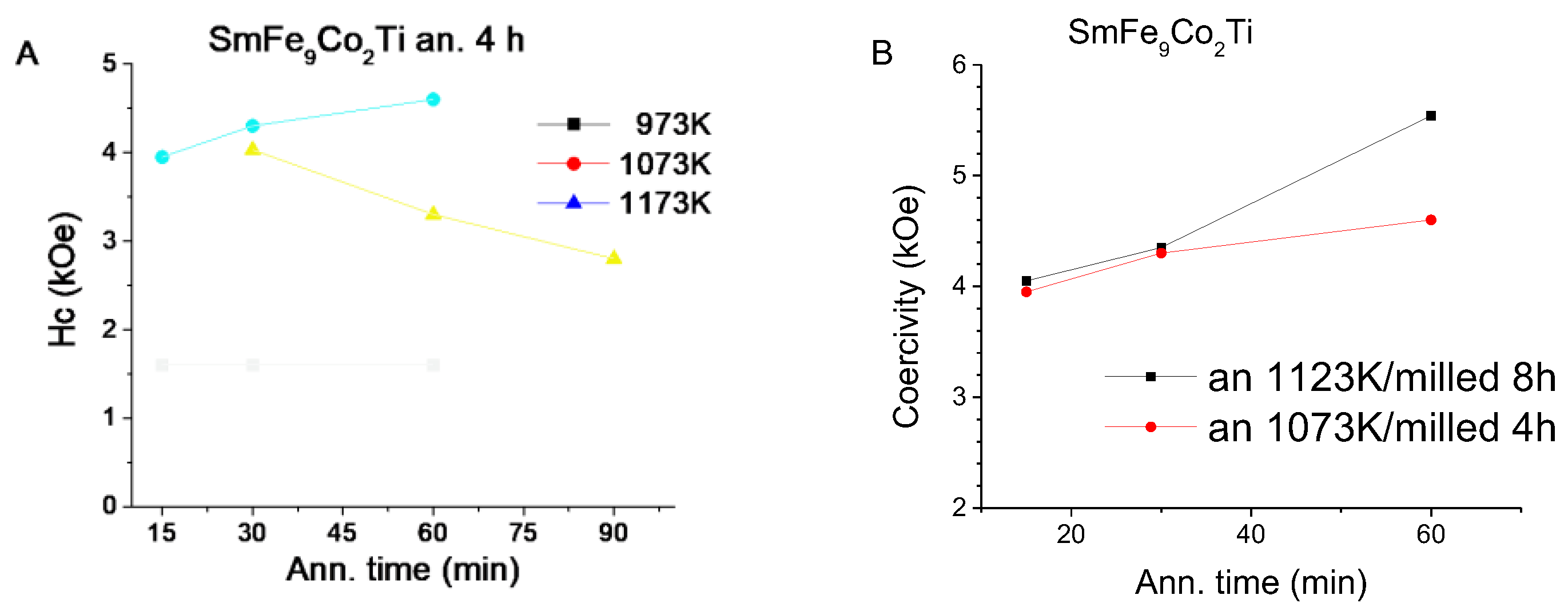

Structure and Magnetic Properties of High-Energy Ball Milling (HEBM)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Popa D. C., Szabó L. Securing Rare Earth Permanent Magnet Needs for Sustainable Energy Initiatives, Materials 2024, 17, 5442. [CrossRef]

- A European Green Deal. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on February 22nd, 2024).

- Podmiljšak B., Saje B., Jenuš P., Tomše T., Kobe S., Žužek K., Šturm S., The Future of Permanent-Magnet-Based Electric Motors: How Will Rare Earths Affect Electrification? Materials 2024, 17, 848. [CrossRef]

- Filippas A., Sempros G., Sarafidis C., Critical rare earths: The future of Nd & Dy and prospects of end-of-life product recycling, Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 37, 4058–4063. [CrossRef]

- Wang X., Yao M., Li J., Zhang K., Zhu H. Zheng M., China’s Rare Earths Production Forecasting and Sustainable Development Policy Implications, Sustainability 2017, 9, 1003. [CrossRef]

- Mooij, D.B. De, and K.H.J. Buschow. Some Novel Ternary ThMn12-Type Compounds. Journal of the Less Common Metals 1988, 136(2), 207–215.

- Hong-Shuo Li, and Coey J.M.D. Chapter 1 Magnetic Properties of Ternary Rare-Earth Transition-Metal Compounds. In Handbook of Magnetic Materials, Editor Buschow K.H.J. Publisher North Holland; 1991, Volume 6, pp 1-83.

- Ohashi, K., Y. Tawara, R. Osugi, and M. Shimao. Magnetic Properties of Fe-rich Rare-earth Intermetallic Compounds with a ThMn12 Structure. J. Appl. Phys. 1988. 64 (10), 5714–16. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Z., and G.C. Hadjipanayis. Magnetic Properties of Sm-Fe-Ti-V Alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1990, 87 (3), 375–78. [CrossRef]

- Wei J., Xu S., Xu C., Liu X., Pan Y., Wang W., Wu Y., Chen P., Liu J, Zhao L, Zhang X. Tuning Fe2Ti Distribution to Enhance Extrinsic Magnetic Properties of SmFe12-Based Magnets, Crystals 2024, 14, 572. [CrossRef]

- Gabay, A.M., and G.C. Hadjipanayis. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Magnetically Hard Anisotropic RFe10Si2 Powders with Representing Combinations of Sm, Ce and Zr. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.2017, 422, 43–48. [CrossRef]

- Saengdeejing, A., Chen, Y. Improving Thermodynamic Stability of SmFe12-Type Permanent Magnets from High Entropy Effect. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2021, 42, 592–605. [CrossRef]

- Okada, M., K. Yamagishi, and M. Homma. High Coercivity in Melt-Spun SmFe10(TiV)2 Ribbons. Materials Transactions, JIM 1989, 30 (5), 374–77. [CrossRef]

- Okada, M., A. Kojima, K. Yamagishi, and M. Homma. High Coercivity in Melt-Spun SmFe10(Ti,M)2 Ribbons (M=V/Cr/Mn/Mo). IEEE Trans. Magn. 1990, 26 (5), 1376–78. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Hadjipanayis G. C., Kim A., Liu N. C., and Sellmyer D. J. Magnetic and Structural Studies in Sm-Fe-Ti Magnets.” J. Appl. Phys. 1990, 67 (9), 4954–56. [CrossRef]

- Tozman, P., H. Sepehri-Amin, T. Ohkubo, and K. Hono. Intrinsic Magnetic Properties of (Sm,Gd)Fe12-Based Compounds with Minimized Addition of Ti. J. Alloy Compd. 2021, 855, 157491. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Bo-Ping, Hong-Shuo Li, J P Gavigan, and J M D Coey. Intrinsic Magnetic Properties of the Iron-Rich ThMn12-Structure Alloys R(Fe11Ti); R=Y, Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm and Lu. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1989, 1(4), 755–70. [CrossRef]

- R. Coehoorn. Electronic structure and magnetism of transition-metal-stabilized YFe12-xMx intermetallic compound. Phys. Rev. B, 1990, 41, 11790–11797. [CrossRef]

- Buschow, K.H.J. Permanent Magnet Materials Based on Tetragonal Rare Earth Compounds of the Type RFe12−xMx. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1991, 100 (1–3), 79–89. [CrossRef]

- Tozman, P., H. Sepehri-Amin, Y.K. Takahashi, S. Hirosawa, and K. Hono. Intrinsic Magnetic Properties of Sm(FeCo )11Ti and Zr-Substituted Sm1-yZr (Fe0.8Co0.2)11.5Ti0.5 Compounds with ThMn12 Structure toward the Development of Permanent Magnets.” Acta Materialia 2018, 153, 354–63. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.F., V.K. Sinha, Y. Xu, J.M. Elbicki, E.B. Boltich, W.E. Wallace, S.G. Sankar, and D.E. Laughlin. Magnetic and Structural Properties of SmTiFe11-xCox Alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1988, 75 (3), 330–38. [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, Y., Y.K. Takahashi, S. Hirosawa, and K. Hono. Intrinsic Hard Magnetic Properties of Sm(Fe1−xCox)12 Compound with the ThMn12 Structure. Scr. Mater. 2017, 138, 62–65. [CrossRef]

- L. Schultz, K. Schnitzke, J. Wecker. High coercivity in mechanically alloyed Sm-Fe-V magnets with a ThMn12 crystal structure, Appl. Phys. Lett. 1990, 56, 868–870. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. S., Tang, X., Sepehri-Amin, H., Srinithi, A. K., Ohkubo, T., & Hono, K. Origin of coercivity in an anisotropic Sm(Fe,Ti,V)12-based sintered magnet. Acta Materialia, 2021, 217, 117161. [CrossRef]

- Zhou T.H., Zhang B., Zheng X., Song Y., Si P., Choi C.J., Cho Y.R., Park J., Anisotropic SmFe10V2 Bulk Magnets with Enhanced Coercivity via Ball Milling Process, Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1329. [CrossRef]

- Xu C., Wen L., Pan A., Zhao L., Liu Y., Liao X., Pan Y., Zhang X., First-Principles Study of Ti-Doping Effects on Hard Magnetic Properties of RFe11Ti Magnets, Crystals 2024, 14, 507. [CrossRef]

- Dirba, I., H. Sepehri-Amin, Ik-Jin Choi, Jin-Hyeok Choi, Hyoun-Soo Uh, Tae-Hoon Kim, Soon-Jae Kwon, T. Ohkubo, and K. Hono. SmFe12-Based Hard Magnetic Alloys Prepared by Reduction-Diffusion Process. J. Alloy Compd. 2021, 861, 157993. [CrossRef]

- Tozman, P., Y.K. Takahashi, H. Sepehri-Amin, D. Ogawa, S. Hirosawa, and K. Hono. The Effect of Zr Substitution on Saturation Magnetization in (Sm1-XZrx)(Fe0.8Co0.2)12 Compound with the ThMn12 Structure.” Acta Materialia 2019, 178, 114–21. [CrossRef]

- Tozman, P., H. Sepehri-Amin, and K. Hono. Prospects for the Development of SmFe12-Based Permanent Magnets with a ThMn12-Type Phase. Scr. Mater. 2021, 194, 113686. [CrossRef]

- Lim, Jung Tae, Hui-Dong Qian, Jihoon Park, Chul-Jin Choi, and Chul Sung Kim. Crystal Structure and Magnetic Properties of Fe-Rich Sm(Fe0.8Co0.2)11Ti Permanent Magnetic Materials. Journal of the Korean Physical Society 2019, 74 (12): 1146–50. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.F., Hou Y.H., Li H.F., Chai W.X., Wu Z.J., Feng Q., Li W., Pang Z.S., Ma L., Yu H.B., Huang Y.L., Microstructure and Magnetic Properties of Exchange-Coupled Nanocomposite Sm0.75Zr0.25(Fe0.8Co0.2)11Ti Alloy. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2023, 571, 170578. [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara M., Sanada N., and Shinya Sakurada. Structural and Magnetic Properties of Rapidly Quenched (Sm,R)(Fe,Co)11.4Ti0.6 (R = Y, Zr) with ThMn12 Structure.” AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 035036. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K., Suzuki S., Kuno T., Urushibata K., Sakuma N., Yano M., Shouji T., Kato A., Manabe A.. The Stability of Newly Developed (R,Zr)(Fe,Co)12−xTix Alloys for Permanent Magnets. J. Alloy Compd. 2017, 694, 914–20. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Feng H., Zhao H., Xu S., Magnetic Properties and Microstructure of Ce and Zr Synergetic Stabilizing Ti-Lean SmFe12-Based Strip-Casting Flakes. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2024, 599, 172100. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M., Hawai T., Ono K, (Sm,Zr)xFe12−xMx (M=Zr,Ti,Co) for Permanent-Magnet Applications: Ab Initio Material Design Integrated with Experimental Characterization. Phys. Rev. App. 2020, 13 (6), 064028. [CrossRef]

- Landa A., Söderlind P., Moore E., Perron A., Thermodynamics and Magnetism of SmFe12 Compound Doped with Zr, Ce, Co and Ni: An Ab Initio Study, Metals 2024, 14, 59. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Cid, A., Salazar, D., Schönhöbel, A. M., Garitaonandia, J. S., Barandiaran, J. M., & Hadjipanayis, G. C. Magnetic properties and phase stability of tetragonal Ce1-xSmxFe9Co2Ti 1:12 phase for permanent magnets. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2018, 749, 640–644. [CrossRef]

- Li Y., Yu N., Wu Q., Pan M., Zhang S., Ge H., Role and optimization of thermal annealing in Sm0.74Zr0.26(Fe0.8Co0.2)11Ti alloys with ThMn12 structure. J. Magn. Magn. Mater., 2022, 549, 169065. [CrossRef]

- Gjoka M., Sarafidis C., Niarchos D. and Hadjipanayis G.C. Evolution of microstructure and magnetic properties in annealed high energy ball milled Sm(Fe, Co, Ti)12 compounds doped, with Zr. In Proceedings of the 64th of Annual Conference on Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, 4-8 November Las Vegas 2019, Abstract Book p. 603.

- R. S. Sundar& S. C. Deevi. Soft magnetic FeCo alloys: alloy development, processing, and properties, International Materials Reviews 2005, 50(3), 157-192. [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou C. N., Takeshita T. Hydrogenation and nitrogenation of SmFe2, Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 1993, 194(1), 31-40. [CrossRef]

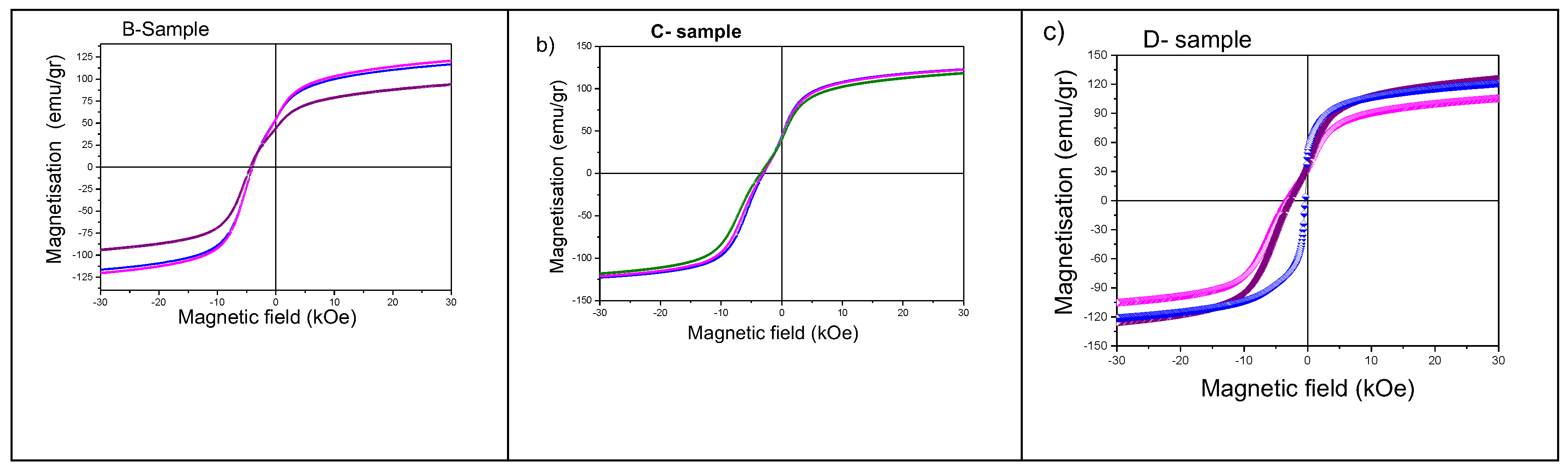

| Sample B ann. at 1123 K | Sample C ann. at 1098 K | Sample D ann. at 1123 K | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ann. time | Hc (kOe) | M3T (emu/gr) | Hc (kOe) | M3T (emu/gr) | Hc | M3T (emu/gr) |

| 15 m | 4.01 | 120.9 | 3.0 | 122.8 | 4.05 | 120.8 |

| 30 min | 4.05 | 120.7 | 3.1 | 122.1 | 3.29 | 105.5 |

| 60 min | 4.37 | 93.6 | 3.5 | 118.4 | 2.76 | 125.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).