Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

In Vietnam, the models for estimating above ground biomass (AGB) for converting to carbon stocks prediction mostly based on diameter at breast height (DBH), tree height (H), wood density (WD) meanwhile the remote sensing application has considered as suitable method since improving accuracy and reducing cost. With this context, this study was conducted with aim to develop correlation equations among total above ground carbon (TAGC) and indices of Sentinel 2 images to directly predict carbon stock for assessing carbon emission and removal. In this study, remote sensing indices great influencing TAGC were determined by principal component analysis (PCA) and forest inventory factors from 115 sample plot was used to calculate the TAGC. Regression models were established by Ordinary Least Squares and Maximum Likelihood methods and validated by Monte Carlo cross-validation method. The study found out that NDVI, SAVI, NIR and three variable combination (NAVI, ARVI), (SAVI, SIPI), (NIR, EVI) have strongly influenced on TAGC. Total 36 linear and non-linear with weight models basing on above selected variables were established, in which quadratic models used NIR and variable combination (NIR, EVI) with AIC of 756.924, 752.493, R2 value of 0.86, 0.87 and MPSE of 22,04%, 21,63% respectively, were found as optimal models. Therefore, the study these models have recommended for predicting carbon stocks for Evergreen Broadleaf Forests in South Central Coastal Ecoregion, Vietnam.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Plots and Estimation of Total Above Ground Carbon

2.3. Sentinel-2 Image and Identification of Key Indices

2.4. Development of Regression Models

2.5. Cross Validation

3. Results

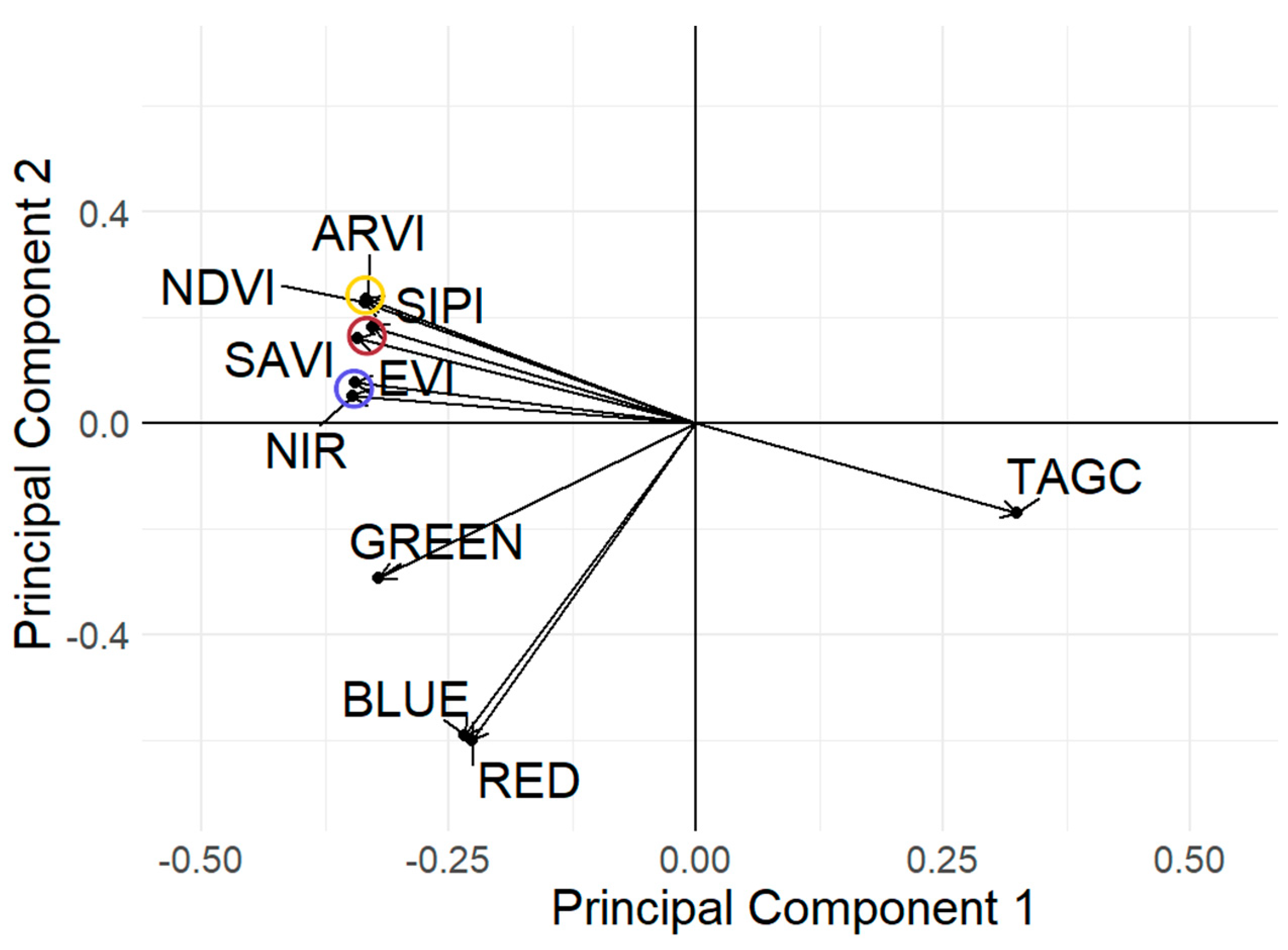

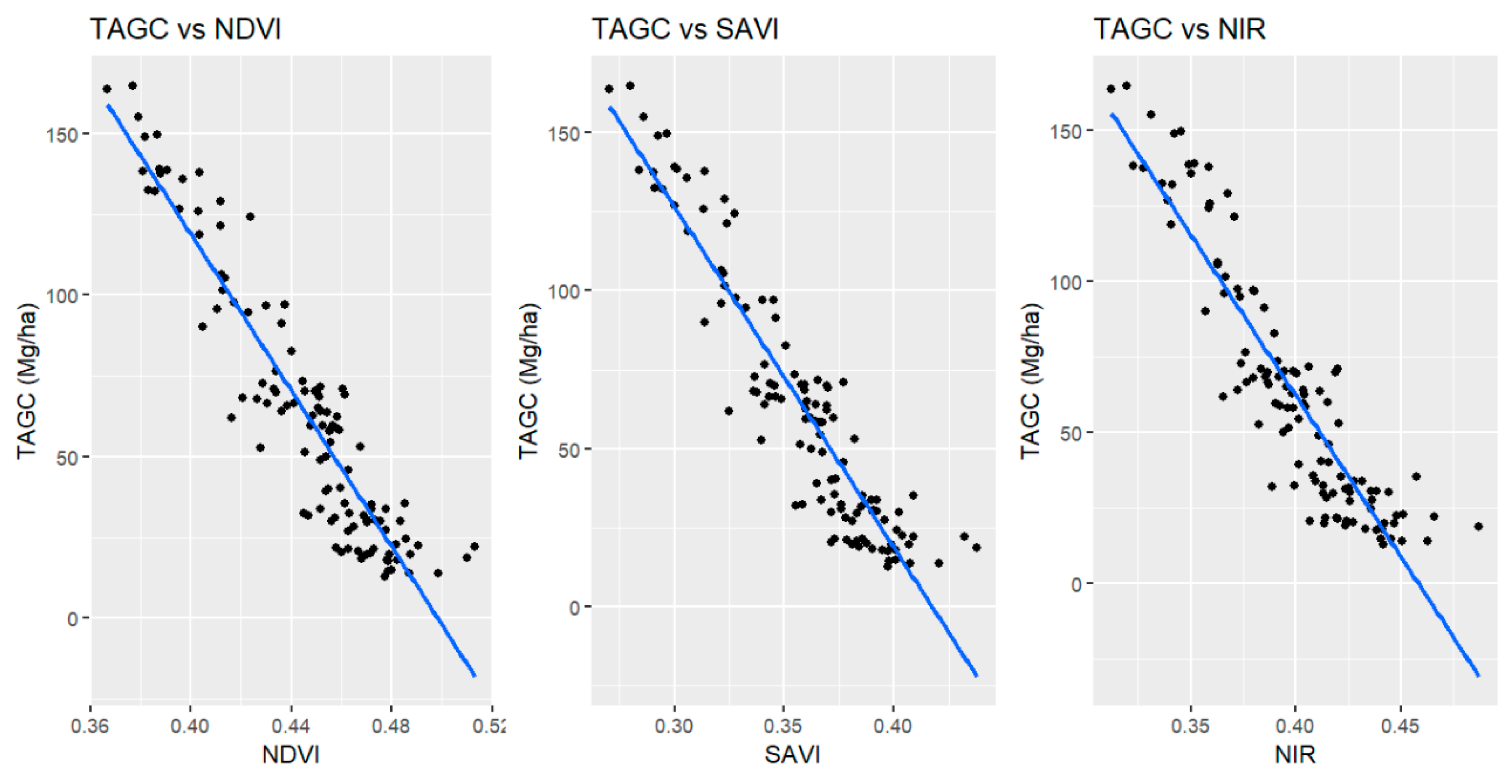

3.1. Vegetation Indices and Multispectral Bands Influencing on Above Ground Carbon

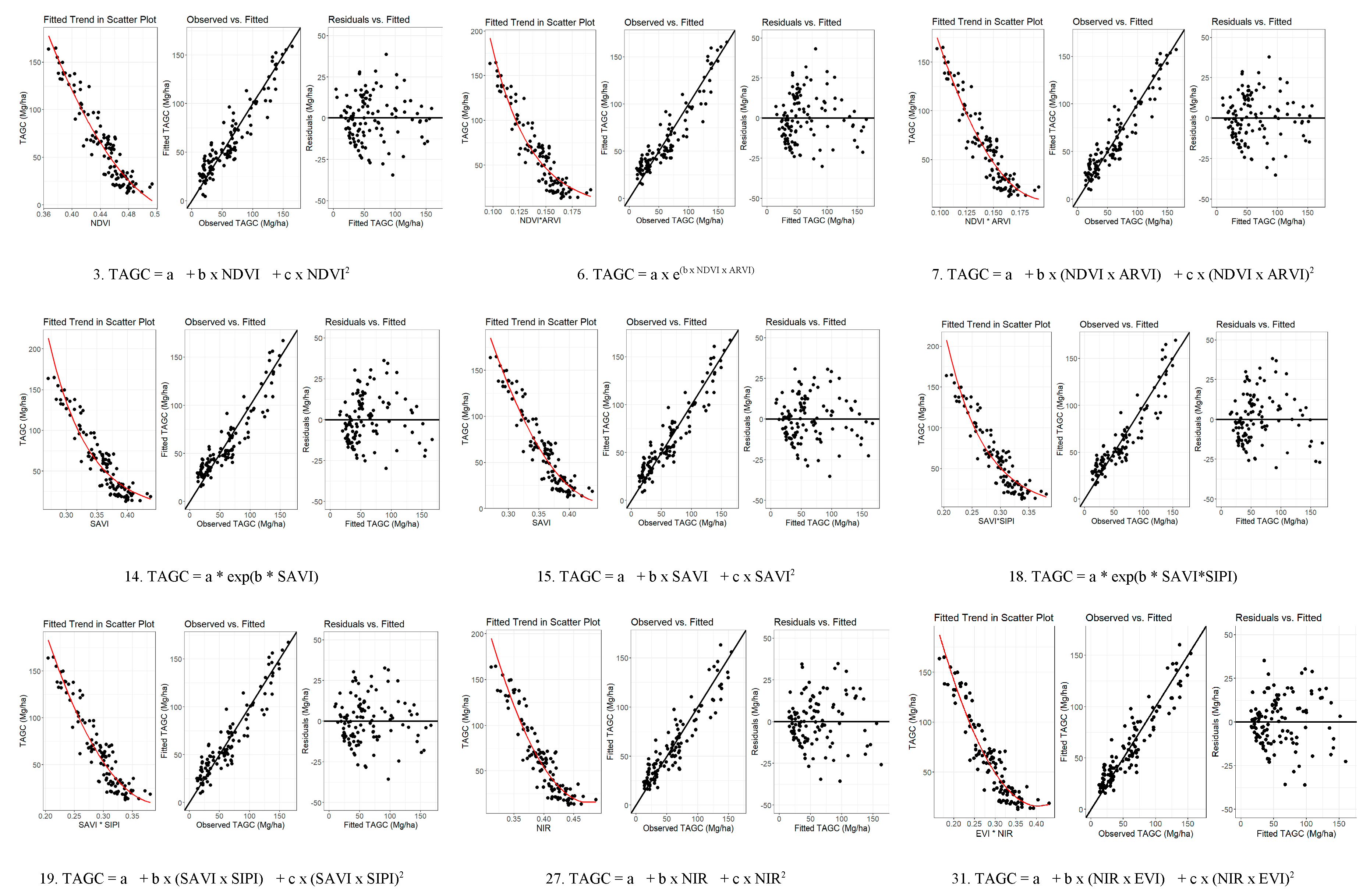

3.2. Establishment of Above Ground Carbon Estimation Models

3.3. Determination of Above Ground Carbon Estimation Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Determination of Indices of Sentinel 2 Imagery Influencing TAGC Prediction

4.2. Establishment and Validation of Models for Predicting TAGC

5. Conclusion

References

- Huete, A.R. A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sensing of Environment 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.; Merzlyak, M.N. Remote estimation of chlorophyll content in higher plant leaves. International Journal of Remote Sensing 1997, 18, 2691–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, B.; Reynolds, G.; Xie, J.; Liang, S.; O’Brien, M.J.; Hector, A. Monitoring tropical forest degradation and restoration with satellite remote sensing: A test using Sabah Biodiversity Experiment. In Advances in Ecological Research; Academic Press Inc., 2020; 62, pp. 117–146. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sensing of Environment 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccini, A.; Friedl, M.A.; Woodcock, C.E.; Warbington, R. Forest biomass estimation over regional scales using multisource data. Geophysical Research Letters 2004, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Vik, J.O.; Mysterud, A.; Gaillard, J.M.; Tucker, C.J.; Stenseth, N.C. Using the satellite-derived NDVI to assess ecological responses to environmental change. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2005, 20, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priatama, A.R.; Setiawan, Y.; Mansur, I.; Masyhuri, M. Regression Models for Estimating Aboveground Biomass and Stand Volume Using Landsat-Based Indices in Post-Mining Area. Jurnal Manajemen Hutan Tropika 2022, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.N.; Ba, D.D.; Trung, D.N.; Viet, H.N.H. A Novel Method for Estimating Biomass and Carbon Sequestration in Tropical Rainforest Areas Based on Remote Sensing Imagery: A Case Study in the Kon Ha Nung Plateau, Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Iqbal, J.; Ali, A.; Khan, S.N. Assessment of Sentinel-2-Derived Vegetation Indices for the Estimation of Above-Ground Biomass/Carbon Stock, Temporal Deforestation, and Carbon Emissions Estimation in the Moist Temperate Forests of Pakistan. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 2020, 18, 783–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, N.; Nuthammachot, N.; Phairuang, W.; Wicaksono, P.; Sayektiningsih, T. Estimating Aboveground Biomass on Private Forest Using Sentinel-2 Imagery. Journal of Sensors, 2018; 6745629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ashton, M.S.; Lee, X. Measuring Carbon in Forests. In Managing Forest Carbon in a Changing Climate; Ashton, M., Tyrrell, M., Spalding, D., Gentry, B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naesset, E.; Gobakken, T.; Solberg, S.; Gregoire, T.G.; Ståhl, G.; Lange, H.; Dick, O.; Gobakken, T.; Astrup, R. Mapping and estimating forest area and aboveground biomass in miombo woodlands in Tanzania using data from airborne laser scanning, TanDEM-X, RapidEye, and global forest maps: A comparison of estimated precision. Remote Sensing of Environment 2016, 175, 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRoberts, R.E.; Næsset, E.; Gobakken, T. Estimation for inaccessible and non-sampled forest areas using model-based inference and remotely sensed auxiliary information. Remote Sensing of Environment 2014, 154, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, J.R.E.; Montealegre, A.L.; Miranda, D.; Segura, A.S.; Ruiz, M.M. A model-based volume estimator that accounts for both land cover misclassification and model prediction uncertainty. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrych, M.; Zagajewski, B.; Marcinkowska-Ochtyra, A. Application of Sentinel-2 and EnMAP new satellite data to the mapping of environmental changes. Polish Cartographical Review 2017, 49, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, V.T.; Inoguchi, A.; Birigazzi, L.; Henry, M.; Sola, G. Introduction and Background of the Study. In Tree Allometric Equation Development for Estimation of Forest Above-Ground Biomass in Viet Nam (Part A); Inoguchi, A., Henry, M., Birigazzi, L., Sola, G., Eds.; UN-REDD Programme: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, F.; Darvishsefat, A.A.; Pourrahmati, M.R.; Deljouei, A.; Borz, S.A. Estimating Aboveground Biomass in Dense Hyrcanian Forests by the Use of Sentinel-2 Data. Forests 2022, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, B. Allometric Model and Remote Sensing-GIS to Estimate Carbon Removal of Evergreen Broadleaf Forests in the Central Highland Region; Publication House of Science and Technique: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Phuong, V.T.; Linh, N.T.M. Final Report on Forest Ecological Stratification in Vietnam; UN-REDD Programme: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sola, G.; Inoguchi, A.; Garcia-Perez, J.; Donegan, E.; Birigazzi, L.; Henry, M. Allometric Equations at National Scale for Tree Biomass Assessment in Viet Nam: Context, Methodology and Summary of the Results; UN-REDD Programme: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia. Da Nang City. Available online: https://vi.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C4%90%C3%A0_N%E1%BA%B5ng (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Da Nang Province People’s Committee. Decision 430/QD-UBND Dated 04/03/2024 on Approval of Forest Status and Land Use Planning for Forest Development in Da Nang City in 2023. 2024.

- Huy, B.; Poudel, K.P.; Temesgen, H. Aboveground biomass equations for evergreen broadleaf forests in South Central Coastal ecoregion of Viet Nam: Selection of eco-regional or pantropical models. Forest Ecology and Management 2016, 376, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Eggleston, H.S., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., Tanabe, K., Eds.; IGES: Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.; Su, B. Significant Remote Sensing Vegetation Indices: A Review of Developments and Applications. Journal of Sensors 2017, 2017, 1353691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Y.J.; Tanre, D. Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index (ARVI) for EOS-MODIS. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 1992, 30, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the Radiometric and Biophysical Performance of the MODIS Vegetation Indices. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2002; 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Filella, I.; Lloret, P.; Muñoz, F.; Vilajeliu, M. Reflectance Assessment of Mite Effects on Apple Trees. International Journal of Remote Sensing 1995, 16, 2727–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Greenacre, M.; Groenen, P.J.F.; Hastie, T.; et al. Principal Component Analysis. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2022, 2, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, B.; Nam, L.C.; Poudel, K.P.; Temesgen, H. Individual Tree Diameter Growth Modeling System for Dalat Pine (Pinus dalatensis Ferré) of the Upland Mixed Tropical Forests. Forest Ecology and Management 2021, 480, 118612: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, B.; Truong, N.Q.; Khiem, N.Q.; Poudel, K.P.; Temesgen, H. Stand Growth Modeling System for Planted Teak (Tectona grandis L.f.) in Tropical Highlands. Trees For People 2022, 9, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, N.; Saint-André, L.; Henry, M. Manual for Building Tree Volume and Biomass Allometric Equations: From Field Measurement to Prediction; FAO: Rome, Italy, Ed.; Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement: Montpellier, France, 2012; 215 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Huy, B.; Khiem, N.Q.; Truong, N.Q.; Poudel, K.P.; Temesgen, H. Additive Modeling Systems to Simultaneously Predict Aboveground Biomass and Carbon for Litsea glutinosa of Agroforestry Model in Tropical Highlands. Forest Systems 2023, 32, e006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. Information Theory and an Extension of the Maximum Likelihood Principle. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Information Theory; Akademiai Kiado: Budapest, Hungary, 1973; pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, W.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Cheng, Z.; Ma, K.; Li, Z. Construction of Compatible and Additive Individual-Tree Biomass Models for Pinus tabulaeformis in China. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2017, 47, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, S.; Tsuyuki, S.; Dube, T. Estimating Above-Ground Biomass in Sub-Tropical Buffer Zone Community Forests, Nepal, Using Sentinel-2 Data. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, A.; Shrestha, H.L.; Mahat, N.; Sharma, G.; Aryal, S.; Kalakheti, R.; Lamsal, B. Modeling and Mapping of Aboveground Biomass and Carbon Stock Using Sentinel-2 Imagery in Chure Region, Nepal. International Journal of Forestry Research 2023, 2023, 5553957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal Component Analysis: A Review and Recent Developments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, V.N.; Tateishi, R.; Kondoh, A.; Sharma, R.C.; Hoan, T.N.; Tu, T.T.; Minh, D.H.T. Mapping Tropical Forest Biomass by Combining ALOS-2, Landsat 8, and Field Plots Data. Land 2016, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| VIs | Definition | Sources (References) |

|---|---|---|

| ARVI | (NIR - (2 x RED) + BLUE)/(NIR + (2 x RED) + BLUE) | [26] |

| EVI | 2.5 x (NIR - RED)/(NIR + 6 x RED - 7.5 x BLUE + 1) | [27] |

| NDVI | (NIR - RED)/(NIR + RED) | [2] |

| SAVI | 1.428 x (NIR - RED)/(NIR + RED + 0.428) | [1] |

| SIPI | (NIR - BLUE)/(NIR - RED) | [28] |

| Model | Correlation equation form | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Linear | TAGC = f(NDVI) | 1/NDVI-2 |

| TAGC = f(SAVI) | 1/SAVI-2 | |

| TAGC = f(NIR) | 1/NIR-2 | |

| TAGC = f(NDVI, ARVI) | 1/NDVI-2 | |

| TAGC = f(SAVI, SIPI) | 1/SAVI-2 | |

| TAGC = f(NIR, EVI) | 1/NIR-2 | |

| Non-linear (Power, Exponential, Quadratic) | TAGC = f(NDVI) | 1/NDVIδ |

| TAGC = f(SAVI) | 1/SAVIδ | |

| TAGC = f(NIR) | 1/NIRδ | |

| TAGC = f(NDVI, ARVI) | 1/NDVIδ | |

| TAGC = f(SAVI, SIPI) | 1/SAVIδ | |

| TAGC = f(NIR, EVI) | 1/NIRδ |

| ID | Equation form | AIC | R2 | ASE (%) | RMSE (Mg ha-1) |

MPSE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TAGC = a + b × NDVI | 762.452 | 0.87215 | 0.75 | 15.08 | 34.47 |

| 2 | TAGC = a x e(b x NDVI) | 769.343 | 0.85502 | -0.96 | 16.15 | 24.67 |

| 3 | TAGC = a + b x NDVI + c x NDVI2 | 754.401 | 0.88567 | 4.76 | 14.34 | 33.30 |

| 4 | TAGC = a x NDVIb | 776.901 | 0.83989 | -2.30 | 16.95 | 25.37 |

| 5 | TAGC = a + b x (NDVI x ARVI) | 773.041 | 0.85401 | -8.30 | 16.32 | 35.60 |

| 6 | TAGC = a x e(b x NDVI x ARVI) | 762.113 | 0.87105 | -3.02 | 15.28 | 23.96 |

| 7 | TAGC = a + b x (NDVI x ARVI) + c x (NDVI x ARVI)2 | 752.085 | 0.88764 | -59.26 | 14.36 | 90.02 |

| 8 | TAGC = a x (NDVI x ARVI)b | 774.778 | 0.84658 | -2.11 | 16.70 | 25.88 |

| 9 | TAGC = a + b x NDVI + c x ARVI | 762.164 | 0.87367 | -3.99 | 14.81 | 33.62 |

| 10 | TAGC = a x e(b x NDVI + c x ARVI) | 769.258 | 0.86312 | -2.83 | 15.89 | 25.34 |

| 11 | TAGC = a + b x NDVI + c x NDVI2 +d x ARVI + e x ARVI2 | 756.739 | 0.88757 | 1.76 | 14.19 | 32.49 |

| 12 | TAGC = a x NDVIb x ARVIc | 775.078 | 0.85231 | -3.17 | 16.40 | 25.57 |

| 13 | TAGC = a + b × SAVI | 765.790 | 0.86697 | -5.12 | 15.38 | 36.42 |

| 14 | TAGC = a x e(b x SAVI) | 762.800 | 0.85757 | -2.84 | 16.35 | 23.62 |

| 15 | TAGC = a + b x SAVI + c x SAVI2 | 748.983 | 0.88897 | 1.27 | 14.14 | 42.69 |

| 16 | TAGC = a x SAVIb | 772.618 | 0.82260 | -1.70 | 17.68 | 24.74 |

| 17 | TAGC = a + b x (SAVI x SIPI) | 771.465 | 0.85792 | -10.79 | 15.83 | 46.47 |

| 18 | TAGC = a x e( b x SAVI x SIPI) | 765.410 | 0.85607 | -2.23 | 15.73 | 23.22 |

| 19 | TAGC = a + b x (SAVI x SIPI) + c x (SAVI x SIPI)2 | 753.226 | 0.88436 | 4.28 | 13.88 | 26.51 |

| 20 | TAGC = a x (SAVI x SIPI)^b | 777.733 | 0.82186 | -1.70 | 17.54 | 25.55 |

| 21 | TAGC = a + b x SAVI + c x SIPI | 766.979 | 0.86804 | 0.03 | 15.44 | 61.61 |

| 22 | TAGC = a x e(b x SAVI + c x SIPI) | 762.561 | 0.86136 | -2.72 | 15.74 | 23.62 |

| 23 | TAGC = a + b x SAVI + c x SAVI2 +d x SIPI + e x SIPI2 | 751.194 | 0.89076 | 3.02 | 14.39 | 29.86 |

| 24 | TAGC = a x SAVIb x SIPIc | 773.127 | 0.82525 | -1.30 | 17.58 | 24.99 |

| 25 | TAGC = a + b x NIR | 785.321 | 0.83064 | 24.52 | 17.03 | 95.31 |

| 26 | TAGC = a x e(b x NIR) | 768.493 | 0.82896 | -0.57 | 16.92 | 23.82 |

| 27 | TAGC = a + b x NIR + c x NIR2 | 756.924 | 0.86649 | 0.70 | 15.50 | 23.17 |

| 28 | TAGC = a x NIRb | 775.476 | 0.78901 | -0.84 | 18.75 | 24.77 |

| 29 | TAGC = a + b x (NIR x EVI) | 785.717 | 0.82968 | -9.43 | 17.54 | 41.36 |

| 30 | TAGC = a x e(b x NIRxEVI) | 761.065 | 0.84910 | -2.65 | 16.20 | 23.33 |

| 31 | TAGC = a + b x (NIR x EVI) + c x (NIR x EVI)2 | 752.493 | 0.87647 | -0.16 | 14.65 | 22.54 |

| 32 | TAGC = a x (NIR x EVI)b | 777.524 | 0.76316 | -0.18 | 20.00 | 24.77 |

| 33 | TAGC = a + b x NIR + c x EVI | 776.007 | 0.85124 | -7.96 | 15.90 | 51.13 |

| 34 | TAGC = a x e(b x NIR + c x EVI) | 768.716 | 0.82342 | -0.27 | 17.77 | 24.71 |

| 35 | TAGC = a + b x NIR + c x NIR2 +d x EVI + e x EVI2 | 756.972 | 0.87294 | 2.35 | 15.23 | 24.13 |

| 36 | TAGC = a x NIRb x EVIc | 775.920 | 0.78908 | -0.02 | 19.85 | 25.11 |

| ID | Equation form | Parameters | P-value | Std. Error | R2 | MPSE (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TAGC = a + b × NDVI | a | 590 | <0.001 | 20.8 | 0.87064 | 35.99 |

| b | -1181,4 | <0.001 | 46.1 | ||||

| 3 | TAGC = a + b x NDVI + c x NDVI2 | a | 1523,206 | <0.001 | 217.6896 | 0.88581 | 26.32 |

| b | -5441,707 | <0.001 | 989.7512 | ||||

| c | 4837,304 | <0.001 | 1121.616 | ||||

| 6 | TAGC = a x e(b x NDVI x ARVI) | a | 2617,904 | <0.001 | 356.5325 | 0.87025 | 23.62 |

| b | -26,8626 | <0.001 | 1.0567 | ||||

| 7 | TAGC = a + b x (NDVI x ARVI) + c x (NDVI x ARVI)2 | a | 648,275 | <0.001 | 53.1819 | 0.88712 | 23.03 |

| b | -6450,795 | <0.001 | 743.7517 | ||||

| c | 16281,53 | <0.001 | 2576.696 | ||||

| 9 | TAGC = a + b x NDVI + c x ARVI | a | 607,43 | <0.001 | 22.71 | 0.87415 | 31.13 |

| b | -2406,51 | <0.001 | 674.97 | ||||

| c* | 1644,34 | 0.071 | 903.84 | ||||

| 11 | TAGC = a + b x NDVI + c x NDVI2 +d x ARVI + e x ARVI2 | a | 1348,19 | <0.001 | 256.874 | 0.88784 | 23.47 |

| b* | 10401,88 | 0.348 | 11037.17 | ||||

| c* | -12747,94 | 0.291 | 12032.41 | ||||

| d* | -20840,87 | 0.154 | 14536.67 | ||||

| e* | 31994,84 | 0.146 | 21860.44 | ||||

| 13 | TAGC = a + b × SAVI | a | 432,86 | <0.001 | 15.47 | 0.86581 | 48.71 |

| b | -1031,04 | <0.001 | 42.15 | ||||

| 14 | TAGC = a x e(b x SAVI) | a | 14563,32 | <0.001 | 3089.371 | 0.85639 | 23.38 |

| b | -15,606 | <0.001 | 0.6266 | ||||

| 15 | TAGC = a + b x SAVI + c x SAVI2 | a | 1070,272 | <0.001 | 109.0798 | 0.88933 | 22.62 |

| b | -4640,056 | <0.001 | 608.0028 | ||||

| c | 5060,527 | <0.001 | 843.6183 | ||||

| 18 | TAGC = a x e(b x SAVI x SIPI) | a | 4288,168 | <0.001 | 701.5295 | 0.85790 | 23.42 |

| b | -14,784 | <0.001 | 0.5977 | ||||

| 19 | TAGC = a + b x (SAVI x SIPI) + c x (SAVI x SIPI)2 | a | 754,192 | <0.001 | 67.7088 | 0.88606 | 22.85 |

| b | -3758,794 | <0.001 | 458.1902 | ||||

| c | 4737,115 | <0.001 | 769.794 | ||||

| 22 | TAGC = a x e(b x SAVI + c x SIPI) | a* | 387,9781 | 0.610 | 759.3648 | 0.86151 | 23.23 |

| b | -20,1558 | <0.001 | 2.5505 | ||||

| c* | 6,3853 | 0.065 | 3.4379 | ||||

| 23 | TAGC = a + b x SAVI + c x SAVI2 +d x SIPI + e x SIPI2 | a* | -762,477 | 0.795 | 2932.537 | 0.88978 | 22.24 |

| b | -5846,867 | <0.001 | 1706.388 | ||||

| c | 6568,468 | 0.004 | 2266.891 | ||||

| d* | 4858,904 | 0.532 | 7756.204 | ||||

| e* | -2845,5 | 0.543 | 4663.326 | ||||

| 27 | TAGC = a + b x NIR + c x NIR2 | a | 1537,576 | <0.001 | 143.5515 | 0.86646 | 22.04 |

| b | -6398,241 | <0.001 | 700.553 | ||||

| c | 6723,375 | <0.001 | 852.3433 | ||||

| 31 | TAGC = a + b x (NIR x EVI) + c x (NIR x EVI)2 | a | 505,7588 | <0.001 | 33.2636 | 0.87646 | 21.63 |

| b | -2411,523 | <0.001 | 214.8227 | ||||

| c | 2967,038 | <0.001 | 343.2117 | ||||

| 35 | TAGC = a + b x NIR + c x NIR2 +d x EVI + e x EVI2 | a | 1513,702 | <0.001 | 205.311 | 0.87259 | 21.76 |

| b | -7727,276 | 0.018 | 3225.838 | ||||

| c | 8721,605 | 0.022 | 3780.838 | ||||

| d* | 790,201 | 0.563 | 1364.302 | ||||

| e | -638,933 | 0.470 | 881.386 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).