Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

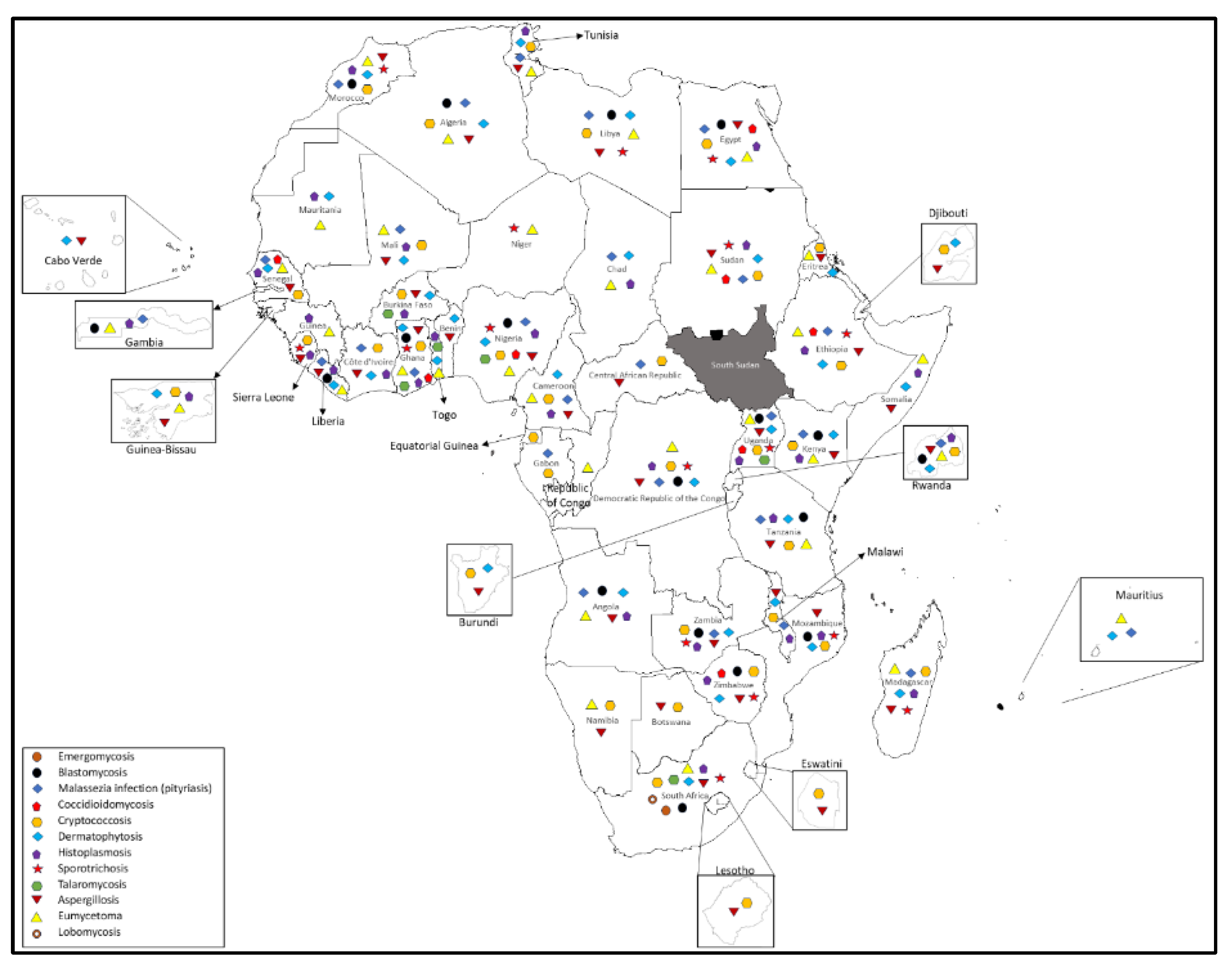

2. Medically Important Fungi with the Potential of Zoonotic Transmission to Humans in Africa:

2.1. Emergomycosis

2.2. Blastomycosis:

2.3. Coccidomycosis:

2.4. Cryptococosis

2.5. Dermatophytosis

2.6. Histoplasmosis

2.7. Sporotrichosis

2.8. Talaromycosis:

2.9. Lobomycosis

2.10. Paracoccidioidomycosis

2.11. Aspergillosis

2.12. Eumycetoma

2.13. Malassezia Infection (pityriasis)

3. Conclusions and Future Perspective:

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency virus |

Appendix A

Appendix A

References

- Rodrigues, M.L.; Nosanchuk, J.D. Fungal Diseases as Neglected Pathogens: A Wake-Up Call to Public Health Officials. In Advances in Clinical Immunology, Medical Microbiology, COVID-19, and Big Data; Jenny Stanford Publishing, 2021 ISBN 978-1-00-318043-2.

- Bongomin, F.; Gago, S.; Oladele, R.O.; Denning, D.W. Global and Multi-National Prevalence of Fungal Diseases—Estimate Precision. Journal of Fungi 2017, 3, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayens, E.; Norris, K.A. Prevalence and Healthcare Burden of Fungal Infections in the United States. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 2022; 9, ofab593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, C.-Y.; Rotstein, C. Emerging Fungal Infections in Immunocompromised Patients. F1000 Med Rep 2011, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, R.; Bansal, Y.; Singla, N. The Zoonotic Potential of Fungal Pathogens: Another Dimension of the One Health Approach. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.T.; Sobur, M.A.; Islam, M.S.; Ievy, S.; Hossain, M.J.; El Zowalaty, M.E.; Rahman, A.T.; Ashour, H.M. Zoonotic Diseases: Etiology, Impact, and Control. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One Health: Fungal Pathogens of Humans, Animals, and Plants: Report on an American Academy of Microbiology Colloquium Held in Washington, DC, on October 18, 2017; American Academy of Microbiology Colloquia Reports; American Society for Microbiology: Washington (DC), 2019.

- Carpouron, J.E.; de Hoog, S.; Gentekaki, E.; Hyde, K.D. Emerging Animal-Associated Fungal Diseases. Journal of Fungi 2022, 8, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.M.; Turku, S.; Lehrfield, L.; Shoman, A. The Impact of Human Activities on Zoonotic Infection Transmissions. Animals 2023, 13, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayagamoorthy, K.; Gangavaram, D.R.; Skiada, A.; Prakash, H. Emergomycosis, an Emerging Thermally Dimorphic Fungal Infection: A Systematic Review. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Quan, M.; Zhong, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; He, F.; Qu, J.; Zhou, T.; Lv, X.; Zong, Z. Emergomyces Orientalis Emergomycosis Diagnosed by Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing. Emerg Infect Dis 2021, 27, 2740–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, I.S.; Lerm, B.; Hoving, J.C.; Kenyon, C.; Horsnell, W.G.; Basson, W.J.; Otieno-Odhiambo, P.; Govender, N.P.; Colebunders, R.; Botha, A. Emergomyces Africanus in Soil, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 2018, 24, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaddar, A.; Sharma, A. Emergomycosis, an Emerging Systemic Mycosis in Immunocompromised Patients: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Front. Med. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, A.; Krishnamurthy, K. Blastomycosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, I.S.; Muñoz, J.F.; Kenyon, C.R.; Govender, N.P.; McTaggart, L.; Maphanga, T.G.; Richardson, S.; Becker, P.; Cuomo, C.A.; McEwen, J.G.; et al. Blastomycosis in Africa and the Middle East: A Comprehensive Review of Reported Cases and Reanalysis of Historical Isolates Based on Molecular Data. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021, 73, e1560–e1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, M.F.; Alpern, J.D.; Bahr, N.C. Blastomycosis—Some Progress but Still Much to Learn. Journal of Fungi 2022, 8, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, K.A.; Kauffman, C.A.; Miceli, M.H. Blastomycosis: A Review of Mycological and Clinical Aspects. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, S.M.; Koirala, J. Coccidioidomycosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland, T.N.; Fierer, J. Coccidioides Immitis and Posadasii; A Review of Their Biology, Genomics, Pathogenesis, and Host Immunity. Virulence 2018, 9, 1426–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, N.F. Coccidioidomycosis: A Contemporary Review. Infect Dis Ther 2022, 11, 713–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, V.; Chaturvedi, S. Cryptococcus Gattii: A Resurgent Fungal Pathogen. Trends in Microbiology 2011, 19, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescador Ruschel, M.A.; Thapa, B. Cryptococcal Meningitis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kruithoff, C.; Gamal, A.; McCormick, T.S.; Ghannoum, M.A. Dermatophyte Infections Worldwide: Increase in Incidence and Associated Antifungal Resistance. Life (Basel) 2023, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshwania, P.; Kaur, N.; Chauhan, J.; Sharma, G.; Afzal, O.; Alfawaz Altamimi, A.S.; Almalki, W.H. Superficial Dermatophytosis across the World’s Populations: Potential Benefits from Nanocarrier-Based Therapies and Rising Challenges. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 31575–31599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, E.; Elad, D. Human and Zoonotic Dermatophytoses: Epidemiological Aspects. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 713532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottferová, L.; Molnár, L.; Major, P.; Sesztáková, E.; Kuzyšinová, K.; Vrabec, V.; Kottferová, J. Hedgehog Dermatophytosis: Understanding Trichophyton Erinacei Infection in Pet Hedgehogs and Its Implications for Human Health. J Fungi (Basel) 2023, 9, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimoldina, A.; Smagulova, A.; Batpenova, G.; Konnikov, N.; Algazina, T.; Jetpisbayeva, Z.; Azanbayeva, D.; Amantayev, D.; Kiyan, V. Mycological Profile and Associated Factors Among Patients with Dermatophytosis in Astana, Kazakhstan. J Fungi (Basel) 2025, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Madhu, R. The Great Indian Epidemic of Superficial Dermatophytosis: An Appraisal. Indian J Dermatol 2017, 62, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhrlaß, S.; Verma, S.B.; Gräser, Y.; Rezaei-Matehkolaei, A.; Hatami, M.; Schaller, M.; Nenoff, P. Trichophyton Indotineae-An Emerging Pathogen Causing Recalcitrant Dermatophytoses in India and Worldwide-A Multidimensional Perspective. J Fungi (Basel) 2022, 8, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Wang, X.; Li, R. Dermatophyte Infection: From Fungal Pathogenicity to Host Immune Responses. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1285887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonego, B.; Corio, A.; Mazzoletti, V.; Zerbato, V.; Benini, A.; di Meo, N.; Zalaudek, I.; Stinco, G.; Errichetti, E.; Zelin, E. Trichophyton Indotineae, an Emerging Drug-Resistant Dermatophyte: A Review of the Treatment Options. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, S.M.; Koirala, J. Histoplasmosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ocansey, B.K.; Kosmidis, C.; Agyei, M.; Dorkenoo, A.M.; Ayanlowo, O.O.; Oladele, R.O.; Darre, T.; Denning, D.W. Histoplasmosis in Africa: Current Perspectives, Knowledge Gaps, and Research Priorities. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022, 16, e0010111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falci, D.R.; Monteiro, A.A.; Braz Caurio, C.F.; Magalhães, T.C.O.; Xavier, M.O.; Basso, R.P.; Melo, M.; Schwarzbold, A.V.; Ferreira, P.R.A.; Vidal, J.E.; et al. Histoplasmosis, An Underdiagnosed Disease Affecting People Living With HIV/AIDS in Brazil: Results of a Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study Using Both Classical Mycology Tests and Histoplasma Urine Antigen Detection. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019, 6, ofz073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, M.B. de L.; de Almeida Paes, R.; Schubach, A.O. Sporothrix Schenckii and Sporotrichosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011, 24, 633–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Herrera, E.; Arenas, R.; Hernández-Castro, R.; Frías-De-León, M.G.; Rodríguez-Cerdeira, C. Uncommon Clinical Presentations of Sporotrichosis: A Two-Case Report. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orofino-Costa, R.; Macedo, P.M. de; Rodrigues, A.M.; Bernardes-Engemann, A.R. Sporotrichosis: An Update on Epidemiology, Etiopathogenesis, Laboratory and Clinical Therapeutics. An Bras Dermatol 2017, 92, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Han, R.; Chen, S. An Overlooked and Underrated Endemic Mycosis-Talaromycosis and the Pathogenic Fungus Talaromyces Marneffei. Clin Microbiol Rev 2023, 36, e0005122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, M. Talaromyces Marneffei. Emerg Infect Dis 2021, 27, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruksaphon, K.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Ratanabanangkoon, K.; Youngchim, S. Talaromyces Marneffei Infection: Virulence, Intracellular Lifestyle and Host Defense Mechanisms. Journal of Fungi 2022, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesconi, V.A.; Klein, A.P.; Santos, A.P.B.G.; Ramasawmy, R.; Francesconi, F. Lobomycosis: Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, and Management Options. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2014, 10, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, L.A.; Torres, J. Paracoccidioidomycosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Brummer, E.; Castaneda, E.; Restrepo, A. Paracoccidioidomycosis: An Update. Clin Microbiol Rev 1993, 6, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, E. Paracoccidioidomycosis Protective Immunity. J Fungi (Basel) 2021, 7, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S.A.; Lastória, J.C.; Camargo, R.M.P. de; Marques, M.E.A. Paracoccidioidomycosis: Acute-Subacute Clinical Form, Juvenile Type. An Bras Dermatol 2016, 91, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongomin, F.; Kibone, W.; Okot, J.; Nsenga, L.; Olum, R.; Baluku, J.B. Fungal Diseases in Africa: Epidemiologic, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Advances. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2022, 9, 20499361221081441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongomin, F.; Ekeng, B.E.; Kibone, W.; Nsenga, L.; Olum, R.; Itam-Eyo, A.; Kuate, M.P.N.; Pebolo, F.P.; Davies, A.A.; Manga, M.; et al. Invasive Fungal Diseases in Africa: A Critical Literature Review. Journal of Fungi 2022, 8, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, B.; Hedayati, M.T.; Hedayati, N.; Ilkit, M.; Syedmousavi, S. Aspergillus Species in Indoor Environments and Their Possible Occupational and Public Health Hazards. Curr Med Mycol 2016, 2, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisodia, J.; Bajaj, T. Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Siddig, E.E.; Ahmed, A. The Urgent Need for Developing and Implementing a Multisectoral One Health Strategy for the Surveillance, Prevention, and Control of Eumycetoma. IJID One Health 2024, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitanis, G.; Magiatis, P.; Hantschke, M.; Bassukas, I.D.; Velegraki, A. The Malassezia Genus in Skin and Systemic Diseases. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2012, 25, 106–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobi, S.; Cafarchia, C.; Romano, V.; Barrs, V.R. Malassezia: Zoonotic Implications, Parallels and Differences in Colonization and Disease in Humans and Animals. Journal of Fungi 2022, 8, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badiane, A.S.; Ramarozatovo, L.S.; Doumbo, S.N.; Dorkenoo, A.M.; Mandengue, C.; Dunaisk, C.M.; Ball, M.; Dia, M.K.; Ngaya, G.S.L.; Mahamat, H.H.; et al. Diagnostic Capacity for Cutaneous Fungal Diseases in the African Continent. International Journal of Dermatology 2023, 62, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease | Causative agents | Animal hosts | Mode of transmission | Clinical manifestation in Animals | Clinical manifestation in human |

| Emergomycosis | Emmonsia spp | Rodents | Inhalation of the fungus | Deep mycosis | Disseminated mycosis |

| Blastomycosis | Blastomyces dermatitidis | Cats, dogs, horses and marine mammals | Inhalation of airborne conidia | Cutaneous, pulmonary, disseminated infection | Cutaneous, pulmonary, disseminated infection |

| Coccidomycosis |

Coccidioides immitis; Coccidioides posadasii |

Cattles, Cats, dogs, horses, snakes, reptiles and marine mammals | Inhalation of conidia and skin trauma | Self-limiting to chronic. Dissemination | Cutaneous, pulmonary, disseminated infection |

| Cryptococosis |

Cryptococcus neoformans; Cryptococcus gattii |

Cattles, goats, Cats, dogs, horses and marine mammals | Inhalation of the fungus; implantation of the fungus into the skin | Respiratory tract, CNS, eyes, and skin. | Cutaneous, eye, respiratory and central nervous system infection |

| Dermatophytosis |

Microsporum spp.; Trichophyton spp |

Cats, dog, cattle, goats, horses, Camels, pigs, rodents, bats | Direct contact with the infected animals or material contaminated from the site of the infection | Ring lesion with central healing and crusts at the peripheral area, some degree of folliculitis |

Tinea |

| Histoplasmosis | Histoplasma capsulatum | Cattle, sheep, horses, dogs, cats, birds, bats, rats, skunks, and opossums | Inhalation of the fungus | Cutaneous, pulmonary, disseminated infection | Cutaneous, pulmonary, disseminated infection |

| Sporotrichosis |

Sporothrix schenckii; Sporothix brasiliensis |

dogs, cats, horses, cows, camels, dolphins, goats, mules, birds, pigs, rats, armadillos | direct inoculation of the organism into skin wounds via contact with plants, soil, or penetrating foreign bodies | lymphocutaneous, cutaneous, and disseminated | lymphocutaneous, cutaneous, and disseminated |

| Talaromycosis | Talaromyces marneffei | Bamboo rats, dogs and cats | Unknown; but it hypothesize that by inhalation of the fungus from the environment | Cutaneous, respiratory and disseminated disease | Cutaneous, respiratory and disseminated disease |

| Lobomycosis | Lacazia loboi | Dolphins | Traumatic inoculation | Cutaneous disease | Cutaneous disease |

| Paracoccidomycosis |

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis; Paracoccidioides lutzii |

Dogs, armadillos and monkeys | Inhalation of the fungus, Inoculation of the organism into the subcutaneous tissues | Cutaneous (skin ulcers), adenitis, and disseminated disease | Mucocutenous, respiratory and disseminated disease |

| Aspergillosis | Aspergillus spp. | Domestic animals (dogs, horse, cats, poultry), birds, and wildlife | Inhaling airborne spores | Pulmonary mainly; cutaneous; and disseminated | Pulmonary mainly; cutaneous; and disseminated |

| Eumycetoma | More than 70 fungal species most prevalent one including Madurella spp.,; Falciformispora spp.,; Fusarium spp., Medicopsis spp., | Cats, Dogs, Horses, Turtles, Fish, Cattle, Tiger | Inoculation of the causative agents into the subcutaneous tissue | Subcutaneous disease mainly, however disseminated infection can also occur | Subcutaneous disease if the disease affected the extremities; respiratory (Lung involvement); CNS |

| Malassezia infection (pityriasis) |

Mallasezia spp. | Dogs, cats, cows, sheep, pig, horse, wild animals |

Normal commensals of the skin | Dermatitis, alopecia, stenosis, otitis externa |

Chronic superficial disease of the skin (pityriasis versicolor), folliculitis, seborrhoeic dermatitis and dandruff, fungaemia |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).