1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative condition characterized by significant cognitive decline, emotional disturbances, and impaired social interactions. As one of the leading causes of disability in older adults, AD presents substantial challenges for patients, caregivers, and healthcare systems worldwide [

1]. Early interventions that address behavioral symptoms and enhance quality of life are crucial for mitigating its impact.

For planning early interventions, it is crucial to identify the prodromal stages of Alzheimer's Disease (AD). Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), a condition associated with an elevated risk of progressing to AD, shows an estimated annual conversion rate of 10–15% in clinical settings, while community-based studies report lower rates, ranging from 3.8% to 6.3% annually. Long-term studies indicate that approximately 80% of individuals with MCI progress to AD over a six-year follow-up period [

2,

3]. MCI, often considered a prodromal stage of AD, is characterized by measurable deficits in cognitive functions—especially memory—that exceed normal aging expectations but do not significantly impair daily activities [

4]. However, MCI represents a critical therapeutic window for interventions aimed at slowing cognitive decline and enhancing psychosocial well-being. Recent progress in Alzheimer's Disease (AD) research has led to a paradigm shift, viewing the disease not as a series of distinct stages but as a continuous process of neurodegeneration. This continuum framework captures the progressive and multifaceted nature of AD, beginning with asymptomatic phases, progressing through Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), and culminating in full-blown dementia [

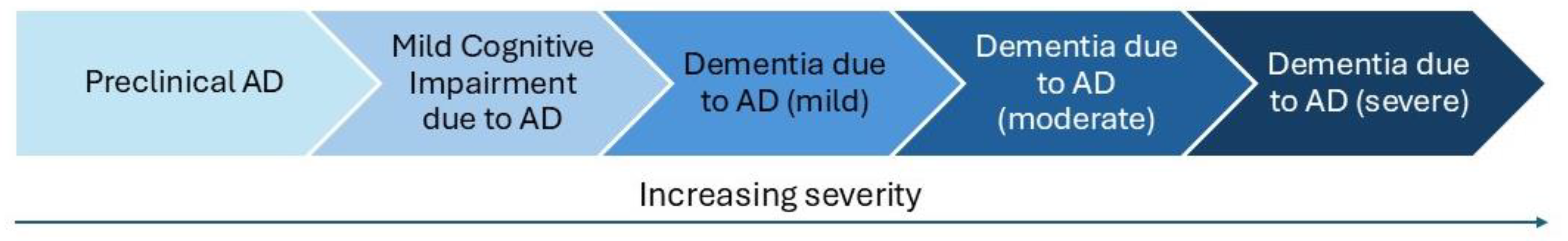

5].

Figure 1 illustrates the escalating severity associated with each stage of the AD continuum.

However, this approach poses challenges in precisely pinpointing an individual’s position within the continuum and assessing their specific risk factors for progression [

6,

7]. Accurate staging is critical for implementing early, targeted interventions that can delay or prevent irreversible neuronal damage and cognitive decline. This highlights the need for advanced diagnostic tools capable of identifying AD pathology in its earliest stages to maximize the potential benefits of therapeutic strategies.

Current therapeutic strategies for AD and MCI primarily involve pharmacological approaches, such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine) and NMDA receptor antagonists (memantine), which manage symptoms rather than halt disease progression [

8]. Recently, Lecanemab, a monoclonal antibody targeting amyloid-beta aggregates, received FDA approval in July 2023, marking a milestone as one of the first treatments to target Alzheimer’s pathology [

9]. Lecanemab binds to soluble amyloid-beta protofibrils, facilitating clearance and slowing cognitive decline in early AD. In the Clarity AD phase 3 trial, it significantly reduced clinical decline over 18 months, improving cognitive and functional measures [

10]. However, risks such as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) highlight the need for careful patient monitoring. While approved in the US, Lecanemab is not yet available in Italy, with EMA approval pending [

11].

In turn, non-pharmacological therapies, including cognitive stimulation, physical activity, and diet modifications, have shown potential in slowing cognitive decline and improving overall well-being [

12]. Complementary therapies, such as music therapy, art therapy, and mindfulness-based interventions, are gaining recognition for their ability to address behavioral symptoms, reduce anxiety, and enhance quality of life in both MCI and AD populations [

13]. For instance, a meta-analysis of 15 studies investigating the effects of music therapy on Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) patients reported significant improvements in cognitive abilities and daily living activities [

14]. Another systematic review and meta-analysis found that non-pharmacological therapies, including music therapy, positively impacted activities of daily living (ADL), behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), cognition, and quality of life (QoL) in individuals with moderate-to-severe dementia [

15]. Furthermore, music therapy alone was shown to significantly enhance cognitive function and quality of life in patients with AD, as highlighted in a separate meta-analysis [

16]. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating evidence-based non-pharmacological interventions, such as music therapy, into treatment plans. By integrating pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches, a multimodal strategy can optimize patient outcomes, addressing both cognitive and emotional challenges associated with AD.

Additionally, emerging technologies, such as Virtual Reality (VR), offer promising opportunities in the therapeutic management of both MCI and AD. VR provides immersive environments that can engage cognitive and emotional processes, potentially improving mood, reducing anxiety, and stimulating autobiographical memory recall [

17]. These attributes make VR particularly suitable for addressing the challenges associated with cognitive decline in both MCI and early AD populations [

18]. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide evidence supporting the efficacy of VR interventions in this context. For example, Kim et al. [

19] highlighted the positive impact of VR in MCI on cognitive function, daily living activities, and neuropsychiatric symptoms, underscoring its potential as a cognitive rehabilitation tool. Furthermore, Zhu et al. [

20] investigated in individuals with MCI the effects of dual-task interventions combining motor and VR-based cognitive training, reporting enhanced executive function and gait performance. In these interventions, VR was primarily used to recreate both artificial and natural landscapes, including tasks designed to simulate real-world environments and activities.

Very recently, Yang et al. [

21] conducted a meta-analysis of 18 randomized controlled trials conducted with VR interventions on MCI patients (722 participants were included), demonstrating significant improvements in cognitive functions among older adults with MCI compared to control groups. The effect sizes reported included a Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) of 0.20 (95% CI: 0.02–0.38) for memory, 0.25 (95% CI: 0.06–0.45) for attention and information processing speed, and 0.22 (95% CI: 0.02–0.42) for executive functions, indicating small to moderate improvements in these cognitive domains. Many of these scenarios included soundscapes, such as ambient environmental sounds like birdsong or flowing water, or music tailored to enhance relaxation and engagement. Additionally, VR has been used for dual-task exercises that combine cognitive challenges with motor activities, such as navigating virtual pathways or interacting with objects within the virtual space [

17,

19]. These findings emphasize the potential of VR as a therapeutic tool for mitigating cognitive decline and improving quality of life in individuals with MCI and early AD. At the same time, the scarcity of applications of VR for early AD compared to MCI, as well as the high costs of devices and the need for multiple sessions, highlight significant challenges to its accessibility and feasibility for long-term AD treatment. This underscores the need for implementing novel methodologies that are both cost- and time-effective, paving the way for more sustainable and widely applicable interventions.

Here, we build on previous studies with VR to evaluate the feasibility, accessibility and acceptability of a VR-based intervention with novel aesthetic and mnestic features for individuals with MCI and mild to moderate AD. By utilizing personalized, emotionally evocative and aesthetically appealing 360-degree videos and music, the intervention aims to improve mood, evoke autobiographical memories, and enhance overall well-being. The audio-video VR stimulation is rooted in research demonstrating the significant role of multi-sensory experiences in enhancing cognitive and emotional outcomes in aging populations [

22]. Positive aesthetic experiences, such as engaging with visually and aurally pleasing stimuli, have been shown to promote emotional well-being, reduce stress, and foster a sense of tranquility [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Music, in particular, has a unique ability to evoke autobiographical memories, even in individuals with significant cognitive impairments, by stimulating neural pathways associated with memory and emotion [

28,

29].

The rationale for this specific VR intervention builds upon previous music-neuroaesthetic findings, leveraging the synergistic effects of immersive environments and evocative music to stimulate cognitive processes and elicit positive emotional responses. By integrating familiar landscapes and culturally relevant music, the intervention seeks to evoke memories, enhance mood, and provide a calming and meaningful experience tailored to the needs of individuals with AD or MCI.

2. Materials and Methods

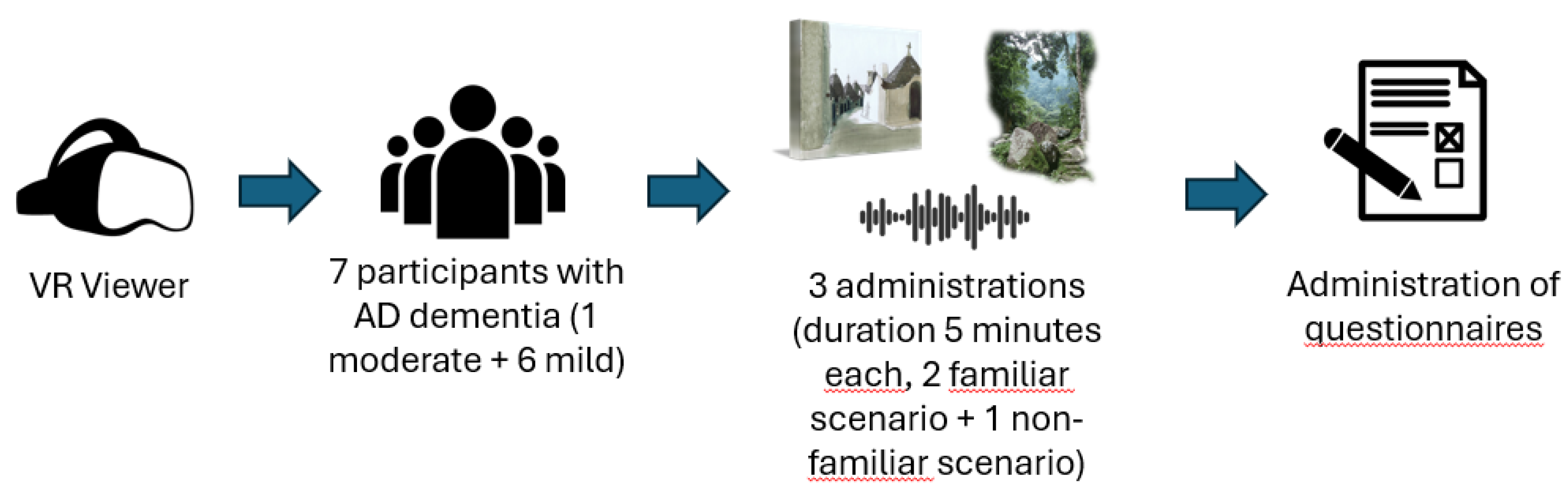

The study involved 7 elderly participants (2 males and 5 females) with a mean age of 70.44 ± 2.24 years (range: 68.5–75.25). All participants exhibited cognitive impairments compatible with an Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) profile, as assessed by their MoCA scores. Specifically, six participants presented with mild cognitive impairments (MoCA scores: 18–25), while one participant exhibited moderate cognitive impairment (MoCA score: 10–17) [

30]. These classifications align with the Alzheimer’s continuum framework, which describes a progression of cognitive decline consistent with AD-related pathology [

5]. The mean MoCA score was 21.57 ± 2.48 (range: 17–24). Cognitive reserve, assessed via the Cognitive Reserve Index Questionnaire (CRIq), averaged 88.29 ± 11.94 (range: 76–109). Male participants had higher cognitive reserve scores (mean: 104 ± 7.07) than females (mean: 82 ± 6.97), reflecting established gender-related differences in cognitive reserve. Individual clinical and neuropsychological profiles are detailed in

Table 1.

Participants were recruited through the Centro Servizi per le Famiglie “Libertà” di Bari. All participants or their caregivers provided informed consent after being briefed on the study’s purpose and procedures.

All experimental procedures complied with the Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research and were approved by the Ethics Committee at the For.Psi.Com Department of the University of Bari (ET-24-18-R1).

Self-assessments of mood are recorded before and after each video presentation through simple questions, and responses were noted each time. Following each video session, participants completed a custom-made questionnaire designed to assess their experience. The questionnaire included items from the Slater-Usoh-Steed (SUS) presence scale [

31], the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) [

32] for mood evaluation and additional semi-structured questions developed by the research team to explore specific aspects of satisfaction with the VR experience, transient mood state, and any memory recollection triggered by the videos.

Eligibility of the participants is determined using MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment), a brief cognitive screening tool with high sensitivity and specificity for detecting MCI [

33].

The Cognitive Research Index Questionnaire (CRIq)[

34] was administered to evaluate participants' cognitive reserve, accounting for their educational, occupational, and leisure activities throughout life.

Physiological and autonomic observations, like respiratory rate and heart rate variability, we measured using the BIOPAC system [

35]. These physiological data will be analyzed in a separate paper.

The study included four 360-degree videos, each lasting up to 5 minutes, delivered through VR support. The VR experience was implemented using the Oculus Quest 2, a standalone virtual reality headset equipped with a high-resolution display (1832 x 1920 pixels per eye), a refresh rate of up to 120 Hz, and a wide field of view to enhance immersion. The device's lightweight design and built-in tracking system enabled participants to interact with the virtual environment comfortably, without requiring additional external sensors. The videos included two familiar scenarios and two non-familiar scenarios. The videos were selected by the team of authors to provide contrasting yet equally immersive and emotionally engaging experiences.

The familiar scenarios consisted of relaxing beach landscapes in Sardinia, created using footage from a YouTube video (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6yAHk_0sv0Q). These videos were looped to depict calm, uninterrupted seaside environments without external interferences or people, aiming to evoke memories of Southern Italian beaches.

These videos were paired with corresponding music: traditional Italian folk or melodic pop songs for the familiar scenarios, and non-familiar folk songs for the non-familiar scenario (

Figure 2).

The selection of the songs was guided by an evaluation process conducted by a group of 4 musicians with expertise in musicology. The evaluation was based on a pool of 30 songs categorized into three groups: Italian lyric songs, Italian folk songs, and foreign compositions. The evaluation process considered several key dimensions for each song. Familiarity was assessed using a 5-point scale, where 1 indicated very low familiarity (the participant did not know the song at all) and 5 indicated very high familiarity (the participant knew the song well or found it reminiscent of similar genres or melodies). Arousal was also rated on a 5-point scale, with 1 representing very low arousal (the song elicited calmness and relaxation) and 5 representing very high arousal (the song evoked energy and excitement). Additionally, pleasantness was measured on a 5-point scale, where 1 indicated very low pleasantness (the song was not enjoyable) and 5 indicated very high pleasantness (the song was highly enjoyable and evoked positive feelings). The songs that were rated as the most relaxing and least activating were selected for the study to ensure they aligned with the calming and immersive goals of the VR intervention. The selected songs included "Non ho l'età" sang by G. Cinquetti, "Il cielo in una stanza" sang by G. Paoli, “Sogna fiore mio” performed by Lucilla Galeazzi, Marco Beasley, L'Arpeggiata,Christina Pluhar and composed by Ambrogio Sparagna, and “Vulesse addeventare nu Brigante" sang by Carlo D'Angiò and produced by Musicanova for the familiar scenarios, and "Finnish Chant" and "Japanese Sonata" for the non-familiar scenarios. A full list of the evaluated songs is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Each participant was shown the two familiar scenarios and one of the two non-familiar scenarios paired with familiar or unfamiliar music (randomly assigned to the videos among the selected songs), with the order of presentation randomized as follows: one familiar scenario, followed by the other familiar scenario, and finally a non-familiar scenario.

3. Results

The following section provides a comprehensive overview of the results obtained from the SUS presence scale and the VAS.

All participants reported a high level of immersion in the virtual environment, with most perceiving the environment as realistic. According to the SUS and VAS questionnaire, half of the participants described the setting as resembling a documentary or an external space, while the other half felt as though they had personally visited the location. Notably, the participant with moderate cognitive decline perceived the environment as resembling a documentary and was aware of being in a virtual environment, contrasting with the responses of participants with mild cognitive decline, who were more likely to report a sense of personal immersion. Regarding mood changes, 3 out of 7 participants reported an improvement in mood following the experience, 3 maintained a positive mood throughout, and only 1 participant experienced a decline in mood, expressing feelings of sadness. This participant, who had moderate cognitive decline, attributed the sadness to the type of landscapes presented, describing them as isolated and reminiscent of once-lived spaces that now appeared abandoned. Tranquility was a prominent sensation, with 6 out of 7 participants reporting a sense of calmness, while one individual described feeling desolation.

In terms of side effects, 5 participants did not report any adverse effects. However, one participant experienced some anxiety related to aversive evoked memories associated with a scenario, as evaluated using the VAS. The VAS required participants to rate their mood on a scale from 0 (very happy) to 5 (extremely sad) before, during, and after the VR experience. The participant, the only one with moderate cognitive decline, exhibited a reduction in mood scores between the pre- and post-experience assessments. In the open-ended interview conducted afterward, this participant reported a state of anxiety triggered by certain scenarios. Another participant reported mental fatigue, attributed to the weight of the VR headset. These observations highlight potential limitations of an autobiographical approach, which should be considered in future studies and discussed further in the context of its applicability.

Concerning memory recall, 4 out of 7 participants experienced positive memories related to their childhood or adolescence, often tied to experiences with their parents or visits to places resembling those presented during the VR experience. The remaining 3 participants recalled recent positive experiences, also connected to similar environments depicted in the virtual scenarios. Notably, despite experiencing anxiety and sadness, the participant with moderate cognitive decline recalled a past episode during the viewing of the Tokyo-park scenario, where she and her mother used to play with her children.

In terms of feedback, 4 participants expressed a desire to explore more scenarios, 3 wished to move around or interact with the environment, and 3 (including the one with moderate cognitive decline) suggested improvements to make the VR headset lighter and more comfortable. One participant also expressed a preference for a greater variety of music.

4. Discussion

This study highlights the feasibility and potential benefits of employing Virtual Reality (VR) interventions for patients with mild to moderate cognitive decline compatible with MCI or dementia profile. The results demonstrate that immersive VR experiences, combined with emotionally evocative music, can elicit positive mood changes, evoke autobiographical memories, and provide a calming and engaging experience for most participants. Previous studies have highlighted the potential of VR therapies in MCI and early AD for improving cognitive and physical functions [

36]. Additionally, the integration of music therapy within virtual environments has shown promise in alleviating psychological and cognitive symptoms of AD [

37,

38].

Our findings expand on this by combining VR and music therapy, providing a multi-sensory therapeutic intervention. This unique approach demonstrates how multi-modal stimulation can enhance therapeutic outcomes, offering participants both cognitive and emotional benefits. Importantly, even a participant with a moderate cognitive decline, as evidenced by lower MoCA scores achieved meaningful results. For instance, despite experiencing some negative emotions such as anxiety and sadness, these individuals were able to recall significant autobiographical memories, highlighting the potential of VR to stimulate emotional and cognitive engagement even at more advanced stages of the disease [

39]. Personalized and culturally relevant stimuli played a central role in eliciting these responses, emphasizing the importance of tailoring interventions to individual needs. Moreover, the aesthetically pleasing design of the VR scenarios contributed significantly to the intervention’s overall appeal and effectiveness, enhancing user satisfaction and emotional resonance [

40]. While minor side effects such as mental fatigue or discomfort were noted, they underscore the necessity of optimizing device design and content customization to improve usability and participant experience.

These observations underline the importance of further research to advance VR-based interventions. Future studies should investigate how integrating culturally sensitive and individually tailored content can amplify the therapeutic benefits of VR. Additionally, exploring long-term impacts, scalability, and the integration of VR with other therapeutic modalities could pave the way for more robust applications in diverse clinical contexts.

The current study has several limitations. Firstly, the small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader AD population. Secondly, the short-term nature of the intervention precludes conclusions about its long-term effects on mood, cognition, or quality of life. Additionally, participants were recruited via a service center rather than a neurology department, which limited access to formal dementia diagnoses. This recruitment method may have influenced the representativeness of the sample and the scope of clinical information available.

Moreover, the lack of a control group makes it difficult to determine whether the observed effects can be attributed solely to the VR intervention. The variability in participants’ familiarity and comfort with technology may have also influenced the outcomes. Finally, the subjective nature of some measures, such as participant feedback, may introduce bias.

However, it is important to note that this is a feasibility study, and these limitations are more pertinent to intervention studies, which are beyond the scope of the current research. Instead, specific methodological limitations associated with feasibility studies should be considered. For example, this study lacks certain standardized measures, such as usability assessments like the SUS, which are often recommended in VR research to evaluate user experience and interface effectiveness [

41]. Additionally, the absence of objective physiological metrics to assess engagement and stress levels during VR exposure is often considered a limitation. However, in this study, we collected physiological data, including respiratory frequency and heart rate variability, alongside subjective assessments to provide a comprehensive understanding of VR's therapeutic potential. While the collection of these data alongside the VR immersion preliminary demonstrates the feasibility of the approach, these physiological measures have not been analyzed yet in order to first focus here on the overall illustration of the protocol, but will be explored in detail in a future paper. Such analyses will enhance methodological rigor and contribute to a more robust evaluation of the intervention's applicability [

42].

Another limitation concerns the practical aspects of the VR system itself. The weight of the Oculus Quest 2 device may have caused discomfort during prolonged sessions, particularly for older participants, potentially impacting their overall experience. Additionally, the relatively high cost of VR equipment may limit its accessibility and scalability in broader clinical applications.

5. Conclusions

The positive results of this feasibility study provide a solid foundation for the design and implementation of larger-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to validate the preliminary findings. Future RCTs should aim to assess the efficacy of VR interventions in improving cognitive and emotional outcomes in AD populations, with a particular focus on long-term effects. Building on the promising outcomes observed, further research could also explore the integration of VR with other non-pharmacological approaches, such as cognitive training or physical exercise, to potentially enhance its therapeutic impact. These next steps will contribute to establishing VR as an accessible and effective tool for cognitive rehabilitation in neurodegenerative conditions.

An important issue related to VR immersions using the Oculus device is its high cost and relatively bulky design, which may reduce its accessibility for widespread use. This limitation could be addressed in future studies by adopting VR visors compatible with mobile phones. These devices are not only more affordable but also portable and easier to use, making them more accessible for patients and their caregivers. As current VR technology allows the translation of Oculus-programmed scenarios to smartphone-compatible formats, this approach could facilitate the testing of this paradigm and other similar interventions in diverse settings, including home environments, thereby increasing its feasibility and practicality.

Lastly, developing tailored VR content that considers cultural and individual differences could optimize the intervention’s effectiveness and accessibility. For example, VR scenarios could be adapted to reflect familiar landscapes or cultural landmarks relevant to specific populations, such as local parks, iconic monuments, or traditional environments. Additionally, incorporating language customization and culturally specific auditory cues (e.g., traditional music or ambient sounds) could enhance the user experience. Personalizing content based on individual preferences, such as serene natural scenes for relaxation or interactive tasks for cognitive stimulation, might further improve engagement and therapeutic outcomes [

43].

In summary, while this study underscores the promise of VR as a complementary therapeutic tool for improving emotional well-being in AD patients, it is noteworthy that even participants with lower MoCA scores, indicative of moderate AD, demonstrated positive outcomes. Despite challenges such as anxiety and sadness, these participants recalled meaningful autobiographical memories, suggesting the potential of VR to evoke emotional and cognitive engagement even in more advanced stages of the disease. Furthermore, the aesthetic quality of the VR experience, characterized by its immersive and visually engaging content, contributed to its overall effectiveness and user satisfaction. These findings highlight the need for further research to refine and expand the clinical applications of VR, particularly in designing interventions that leverage the therapeutic benefits of aesthetic and emotionally evocative environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Selection of songs evaluated for the experiment. The table is available for downloading at:

https://osf.io/qk5x6/

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Elvira Brattico and Vitoantonio Bevilacqua; methodology, Elvira Brattico; software, Francesco Carlomagno, Vitoantonio Bevilacqua, Elena Sibilano and Antonio Brunetti; validation, Elvira Brattico; formal analysis, Francesco Carlomagno; investigation, Francesco Carlomagno and Mariangela Lippolis; resources, Francesco Carlomagno, Vitoantonio Bevilacqua, Elena Sibilano, Raffaele Diomede and Antonio Brunetti; data curation, Francesco Carlomagno, Raffaele Diomede and Mariangela Lippolis; writing—original draft preparation, Francesco Carlomagno; writing—review and editing, Mariangela Lippolis, Elena Sibilano, Marianna Delussi and Elvira Brattico; visualization, Francesco Carlomagno; supervision, Elvira Brattico; project administration, Elvira Brattico; funding acquisition, Vitoantonio Bevilacqua and Elvira Brattico. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was produced with the co-funding European Union - Next Generation EU, in the context of The National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Investment Partenariato Esteso PE8 "Conseguenze e sfide dell'invecchiamento", Project Age-It (Ageing Well in an Ageing Society), CUP: H33C22000680006; This research is also supported by funding from the scholarships awarded to talented and deserving students, even if lacking financial means as defined by Article 8 of Legislative Decree 68/2012, for the academic year 2021/2022, are supported by the PON “Research and Innovation” 2014-2020 - FSE REACT EU - OT 13 - Promoting the recovery from the effects of the crisis in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and its social consequences, while preparing for a green, digital, and resilient economic recovery – Axis IV - Action IV.4 Scholarships for deserving students in economic hardship. (Project Code: DOT1302484; CUP: H99J21010230001; Project Title: Alleviating social isolation and its consequent neurological damage in pathological aging through electrical and musical stimulation in virtual and augmented reality (VR+AR)); This research is also supported by funding from the PSICHE - Intelligent Software Platform for the Analysis and Evaluation of Cognitive Functional Characteristics in VR and AR Stimulation Experiments project, within the ECOSISTEMA DELL’INNOVAZIONE “TuscanyHealthEcosystem” (THE) framework (Project Code: ECS00000017, CUP: D53C24001870007).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Bari (ET-24-18-R1, 17-07-2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD |

Alzheimer’s Disease |

| MCI |

Mild Cognitive Impairment |

| VR |

Virtual Reality |

| MoCA |

Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| CRIq |

Cognitive Reserve Index Questionnaire |

| VAS |

Visual Analogue Scale |

| SUS |

Slater-Usoh-Steed Presence Scale |

| BPSD |

Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia |

| QoL |

Quality of Life |

| RCT |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

| ARIA |

Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities |

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2023, 19, 1–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C.; Smith, G.E.; Waring, S.C.; Ivnik, R.J.; Tangalos, E.G.; Kokmen, E. Mild Cognitive Impairment: Clinical Characterization and Outcome. Archives of Neurology 1999, 56, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; Liu, E. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia 2018, 14, 535–62. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, R.C.; Smith, G.E.; Waring, S.C.; Ivnik, R.J.; Tangalos, E.G.; Kokmen, E. Mild Cognitive Impairment: Clinical Characterization and Outcome. Archives of Neurology 1999, 56, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisen, P.S.; Cummings, J.; Jack, C.R.; Morris, J.C.; Sperling, R.; Frölich, L.; Jones, R.W.; Dowsett, S.A.; Matthews, B.R.; Raskin, J.; Scheltens, P.; Dubois, B. On the Path to 2025: Understanding the Alzheimer’s Disease Continuum. Alzheimer’s Research and Therapy 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnetti, L.; Chipi, E.; Salvadori, N.; D’Andrea, K.; Eusebi, P. Prevalence and Risk of Progression of Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease Stages: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 2019, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsteinsson, A.P.; Isaacson, R.S.; Knox, S.; Sabbagh, M.N.; Rubino, I. Diagnosis of Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Clinical Practice in 2021. The Journal Of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Lee, G.; Ritter, A.; Zhong, K. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2019. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2019, 5, 272–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F.D.A. FDA Converts Novel Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment to Traditional Approval, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-converts-novel-alzheimers-disease-treatment-traditional-approval.

- Van Dyck, C.H.; Swanson, C.J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; Group, L.S. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. The New England Journal of Medicine 2023, 388, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El País, E. Europa recula y recomienda aprobar el polémico lecanemab contra el alzhéimer, 2024. https://elpais.com/ciencia/2024-11-14/europa-recula-y-recomienda-aprobar-el-polemico-lecanemab-contra-el-alzheimer.html.

- Ngandu, T. A 2-Year Multidomain Intervention of Diet, Exercise, Cognitive Training, and Vascular Risk Monitoring versus Control to Prevent Cognitive Decline in at-Risk Elderly People (FINGER): A Randomised Controlled Trial. The Lancet 2015, 385, 2255–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.H.; Lee, S.; Kim, W.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, M.J.; Han, H.J. Effect of Integrated Cognitive Intervention Therapy in Patients with Mild to Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. Dementia and Neurocognitive Disorders 2020, 19, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, T.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, Y. The Effectiveness of Music Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2020, 13, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, G.; Kelly, L.; Lewis-Holmes, E.; Baio, G.; Morris, S.; Patel, N.; Omar, R.Z.; Katona, C.; Cooper, C. Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Agitation in Dementia: Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science 2014, 205, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleibel, M.; El Cheikh, A.; Sadier, N.S.; Abou-Abbas, L. The Effect of Music Therapy on Cognitive Functions in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Alzheimer’s research & therapy 2023, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manera, V.; Chapoulie, E.; Bourgeois, J.; Guerchouche, R.; David, R.; Ondrej, J. A Feasibility Study with Image-Based Rendered Virtual Reality in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 0151487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appel, L.; Appel, E.; Bogler, O.; Wiseman, M.; Cohen, L.; Ein, N.; Abrams, H.B.; Campos, J.L. Older Adults with Cognitive and/or Physical Impairments Can Benefit from Immersive Virtual Reality Experiences: A Feasibility Study. Frontiers in Medicine 2020, 6, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O.; Pang, Y.; Kim, J.H. The Effectiveness of Virtual Reality for People with Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Sui, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ali, N.; Guo, C.; Yang, J. Effects of Virtual Reality Intervention on Cognition and Motor Function in Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2021, 13, 586999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chang, F.; Yang, H.; Chen, B.; Liu, Z. Virtual Reality Interventions for Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2025, 27, 59195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dieuleveult, A.L.; Siemonsma, P.C.; Erp, J.B.; Brouwer, A.M. Effects of Aging in Multisensory Integration: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2017, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancatisano, O.; Baird, A.; Thompson, W.F. Why Is Music Therapeutic for Neurological Disorders? The Therapeutic Music Capacities Model. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2020, 112, 600–615. [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt, D.; Finn, S. What Is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, 2019.

- Brattico, E.; Varankaitė, U. Aesthetic empowerment through music. Musicae Scientiae 2019, 23, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reybrouck, M.; Vuust, P.; Brattico, E. Neural Correlates of Music Listening: Does the Music Matter? Brain Sciences 2021, 11, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippolis, M.; Carlomagno, F.; Campo, F.F.; Brattico, E. The Use of Music and Brain Stimulation in Clinical Settings: Frontiers and Novel Approaches for Rehabilitation in Pathological Aging. In The Theory and Practice of Group Therapy. IntechOpen; 2023.

- Campo, F.F.; Brattico, E. Remembering Sounds in the Brain: From Locationist Findings to Dynamic Connectivity Research. RIVISTA DI PSICOLOGIA CLINICA 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matziorinis, A.M.; Koelsch, S. The Promise of Music Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2022, 1516, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertkow, H.; Nasreddine, Z.; Johns, E.; Phillips, N.; McHenry, C. P1-143: The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): Validation of Alternate Forms and New Recommendations for Education Corrections. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2011, 7, 157–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usoh, M.; Catena, E.; Arman, S.; Slater, M. Using Presence Questionnaires in Reality. Presence 2000, 9, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, G.Z.; Manuguerra, M.; Chow, R. How to Analyze the Visual Analogue Scale: Myths, Truths and Clinical Relevance. Scandinavian journal of pain 2016, 13, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005, 53, 695–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, M.; Mapelli, D.; Mondini, S. The Cognitive Reserve Questionnaire (CRIq): A New Instrument for Measuring the Cognitive Reserve. Aging clinical and experimental research 2012, 24, 218–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. I. O. P. A. C. S. Biopac Student Lab PRO Manual; BIOPAC Systems Inc: Goleta, CA, 2008.

- Yi, Y.; Hu, Y.; Cui, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, J. Effect of Virtual Reality Exercise on Interventions for Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in psychiatry 2022, 13, 1062162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrns, A.; Abdessalem, H.; Cuesta, M.; Bruneau, M.; Belleville, S.; Frasson, C. EEG Analysis of the Contribution of Music Therapy and Virtual Reality to the Improvement of Cognition in Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Biomedical Science and Engineering 2020, 13, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manera, V.; Petit, P.D.; Derreumaux, A.; Orvieto, I.; Romagnoli, M.; Lyttle, G.; David, R.; Robert, P.H. “Kitchen and Cooking,” a Serious Game for Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Pilot Study. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2015, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, A.; Lucidi, F.; Mallia, L.; D’Aiuto, M.; Giordano, A. Virtual Reality in Health System: Beyond Entertainment. A Mini-Review on the Efficacy of VR during Cancer Treatment. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2016, 231, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, A.; Vartanian, O. Neuroaesthetics. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2014, 18, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt-Antons, J.-N.; Kojić, T.; Ali, D.; Möller, S. Influence of Hand Tracking as a Way of Interaction in Virtual Reality on User Experience, 2020. https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.12642.

- Park, M.J.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, U.; Na, E.J.; Jeon, H.J. A Literature Overview of Virtual Reality (VR) in Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Recent Advances and Limitations. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2019, 10, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardini, S.; Gabrielli, S.; Dianti, M.; Novara, C.; Zucco, G.M.; Mich, O.; Forti, S. The Role of Personalization in the User Experience, Preferences and Engagement with Virtual Reality Environments for Relaxation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).