1. Introduction

The exponential growth in cloud service adoption has fundamentally transformed how user applications are deployed and accessed over the internet [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This transformation has led to an unprecedented increase in available online services [

5,

6,

7], creating both opportunities and challenges in service composition and management. Cloud services exist in two primary forms: single services offering basic functionality and composite services that combine multiple primitives to meet complex requirements. While single services serve specific needs, they often fall short in addressing sophisticated user requirements, driving the demand for composite services [

1,

5].

Efficient service composition in multi-cloud environments (MCEs) presents several critical challenges. Service providers must optimize multiple competing objectives simultaneously, including QoS, execution time, and resource usage. The complexity of selecting optimal service combinations from vast service pools, coupled with the challenge of minimizing inter-cloud communication overhead, makes this task particularly demanding. Additionally, maintaining reliability while reducing the number of combined clouds poses a significant technical challenge that current solutions have yet to fully address.

Current approaches to service composition, particularly those employing Nature-inspired Algorithms (NIAs), have demonstrated success in solving NP-hard optimization problems [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, significant limitations persist in existing solutions. Most current approaches focus on single-cloud environments [

5,

15], making them vulnerable to single points of failure. Multi-cloud approaches lack efficient mechanisms for simultaneously optimizing the number of combined clouds (NC) and quality of service (QoS). Furthermore, while previous studies [

15,

16,

18,

20,

21] address NC optimization, they fail to balance it effectively with other critical parameters.

To address these limitations, we propose a Chemistry-based Approach (CA) that draws inspiration from the organizational principles of the periodic table and electron shell theory. Our approach establishes a novel mapping between chemical concepts and cloud service composition. We organize services in hierarchical structures based on QoS levels, similar to how electrons organize themselves in shells based on energy levels. In addition, SFs (Service Files), which describe service tasks, are arranged in an SF table based on composition frequency and cloud distribution, mirroring the periodic table's organization of elements by atomic properties. The service composition and optimization methodology in our approach is analogously modeled on the periodic table's structure and the dynamic behavior of electrons transitioning between shells during chemical reactions.

Our approach uniquely structures SFs in a novel SF table that groups SFs according to their composition frequency and distribution across clouds. Within each SF, services are further arranged in four QoS levels (very high, high, medium, and low), mirroring electron shell organization in atoms. This organization significantly enhances the efficiency of service composition while maintaining high-quality standards.

The main contributions of this research are:

A novel Chemistry-based Approach (CA) that utilizes the principles of the periodic table and electron shell theory to systematically reduce the complexity associated with service composition;

An efficient optimization framework that simultaneously addresses multiple objectives in QoS, NC, NEC, NES, and execution time;

Empirical validation demonstrating significant improvements over existing approaches Genetic Algorithms (GA), Simulated Annealing SA, and Tabu Search (TS) across multiple performance metrics.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 discusses the state of art,

Section 3 explains the proposed CA methodology,

Section 4 outlines the experimental design,

Section 5 presents results and analysis, and

Section 6 concludes with future research directions.

2. Related Work

This section reviews existing studies by classifying service composition algorithms into traditional, nature-inspired, and hybrid service composition methods. The following subsections delve into the details of these algorithms.

2.1. Traditional Service Composition Algorithms

A variety of traditional algorithms have been developed to address service composition problems. Cassar et al. [

22] proposed a divide-and-conquer algorithm that breaks down composition requests into simpler sub-requests. This iterative process continues until each sub-request finds at least one service that satisfies its requirements, forming a composite service by combining the identified services. Some algorithms focus on meeting QoS requirements. For example, Shang et al. [

23] proposed an approach for service composition using a bipartite-directed graph. Ghobaei-Arani and Souri [

24] suggested an approach based on linear programming to select an efficient quality-oriented web service composition (QWSC) for every request in a cloud environment. Guidara et al. [

25] developed exact and approximate approaches for small and large selection problems, respectively, incorporating a pruning technique to minimize the search space and enhance efficiency.

In MCEs, research on minimizing NC for efficient service composition remains limited. Kurdi et al. [

18] proposed a combinatorial optimization algorithm-based method. By choosing the cloud with the highest SFs, their approach increased the delivery of composite services with the smallest NC in the shortest period of time. Mezni et al. [

26] presented a formal concept analysis-based service composition method for identifying and classifying cloud compositions while reducing NC and communication overhead. Nazari et al. [

27] introduced a tree-based similarity metric to select suitable clouds and composition plans to improve load balancing between multiple clouds. Yin and Hao [

20] devised an energy-aware multi-targets service composition method (EMTSC) to reduce energy usage, execution time, and NC by accounting for networks between users and clouds as well as network connections between clouds. Cloud service provider count is considered a crucial parameter during the service composition process. In cloud computing environments, it directly affects response time, energy usage, and overall cost. Souri et al. [

21] proposed a formal verification framework for ensuring service composition with high QoS in an MCE by reducing the number of cloud service providers. Employing a multi-label transition system and algebra methods based on Pi calculus, this approach allows for an examination of service composition while considering both functional and non-functional features, such as QoS standards. Heidari and Emadi [

5] developed a skyline service algorithm for modeling the relationship between cloud service providers and clouds by minimizing NC, the providers, and the communication between them.

2.2. Nature-Inspired Service Composition Algorithms

NIAs mimic biological, physical, or chemical phenomena in nature [

28] and are often employed to obtain optimized solutions for service composition problems [

10]. NIAs can be classified into three main groups: chemistry-based, physics-based, and bio-based approaches [

28]. The following subsections provide a detailed description of these algorithms.

2.2.1. Bio-Based Methods

Bio-based methods are divided into two categories: evolution-based methods and swarm-based methods.

Evolution-based methods are optimization algorithms that draw inspiration from biological evolution and natural selection processes. Genetic Algorithms (GA) represent one of their most prominent examples. GAs are widely used NIAs for optimizing service composition. Their execution involves four primary steps [

10,

29]. The first step is an initialization process, which involves randomly generating individual solutions in the initial population, where each chromosome represents a composite service. The second stage is a fitness evaluation, which involves assessing the quality of each solution to satisfy user needs. The third step, selection, involves choosing individual solutions to reproduce new solutions for the next generation. The fourth step entails evolving new solutions using crossover and mutation operations over the selected individual solutions. These four steps are iterated until a termination criterion is met, yielding an optimal solution.

Various enhancements for QoS optimization have been proposed, for instance, Tang et al. [

30] introduced a hybrid genetic process combining local optimization at the end of each generation and the initial population to improve the overall quality of solutions. Grati et al. [

31] proposed a penalty-based GA considering user QoS and resource constraints, achieving scalability compared to integer programming, especially with more web services and resources. Wang et al. [

32] designed a GA-based approach for identifying QoS-aware service composition solutions in a geographically distributed cloud environment. In addition, Jatoth et al. [

33] developed a fitness-aware service composition approach for cloud environments. They incorporated a GA based on adaptive genotype evolution, resolving connection constraints and optimizing quality-related metrics. Sadeghiram [

34] suggested a multi-objective distributed approach for web service composition (WSC) that employs a novel local search method using link dominance and a non-dominated sorting GA. Similarly, Wang et al. [

35] proposed a hybrid strategy to improve the Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm 2 (SPEA2) for multi-objective optimization problems. In another study, Wang et al. [

36], developed an adaptive mutation technique to enhance the performance of the SPEA2 algorithm in multi-objective WSC.

Other researchers employed clustering techniques for service composition problems. García et al. [

37] employed GAs for location-aware, scalable service composition, proposing various solutions, such as a local express approach, a GA utility solution, and a pure GA solution. These solutions evaluate services to select the top candidate, with approaches like U and express reducing population size. While utility-based approaches rely on clustering candidate providers to complete tasks, express techniques prioritize providers with the highest fitness for each service.

Sadeghiram et al. [

38] introduced a GA designed to improve end-to-end QoS by considering communication costs and delays. Their approach generates the initial population using a K-means clustering algorithm. Zhang et al. [

39] employed fuzzy multi-objective linear programming to develop a constraint satisfaction-based WSC method aimed at addressing vague QoS requirements.

Swarm-based methods are optimization algorithms inspired by collective behaviors in nature, particularly how groups of organisms work together. These methods have been widely applied to service composition problems, where the goal is to effectively combine individual web services to create more complex functionality. Among the main effective approaches include particle swarm optimization (PSO) [

40,

41,

42], ant colony optimization (ACO) [

15,

43,

44], the artificial bee colony approach (ABC) [

79,

80], the fruit fly optimization algorithm (FOA) [

47,

48], the shuffled frog leaping algorithm [

49], and the cuckoo search algorithm (CSA) [

9,

16,

50]. Due to space limitations, we provide details of only a few of the most efficient NIAs in the following subsections: PSO, ACO, and the CSA.

Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithms (PSO), introduced by Kennedy and Eberhart in 1995, are inspired by the food-seeking behavior of animals like birds and fish,. This method relies on the swarm’s intergroup teamwork to direct the search for an optimal solution. The first step is to randomly generate the initial population and velocity of particles. The velocity and location of each particle are then updated during each iteration by retaining information about the global highest position and local top position. This allows the population of particles to ultimately reach a better search area [

51,

52].

Amiri et al. [

40] proposed PSO for QWSC, where particles are modeled as vectors representing candidate WSCs. The particles are responsible for finding suitable candidates to fill the empty slots of the predefined workflow. The acceleration coefficients used to update the particle velocity are calculated using the method of Clerk and Kennedy [

53]. Furthermore, Balakrishnan et al. [

42] developed “the middleware for future Internet,” in conjunction with a composite service selection module, to assist in selecting optimal composite services based on solution quality and user experience. Fuzzy membership functions are used to model reputation, availability, and reliability. PSO is employed to select an ideal service from a set of paths inside a directed acyclic graph based on QoS. Nazif et al. [

54] also created a fuzzy-based PSO algorithm for the creation of cloud composite services. To enhance the optimization process, their technique employs fuzzy membership rules and functions. In a similar vein, Tabalvandani et al. [

55] proposed using a multi-objective PSO algorithm to create a cost-efficient and reliability-aware model for service composition in multi-cloud scenarios. Subsequently, Gao et al. [

41] implemented an improved PSO (IPSO) method to compose services in a dynamic hybrid network. Initially, each service is categorized according to user requirements through interface matching. Following this, the IPSO algorithm generates a composition plan. If the fitness value of a service falls below a predefined threshold, it is substituted using a greedy algorithm. Conversely, if the overall composition fitness is below the threshold, the IPSO algorithm is reapplied to refine the composition.

Ant Colony Optimization Algorithms (ACO) is a nature-inspired optimization technique that simulates the behavior of ants foraging toward the nearest food source. This mechanism is based on the pheromones deposited by ants, which guide others to follow the path, with a high pheromone intensity tied to the closest food source. Ants begin searching by randomly leaving their nest, and each ant lays pheromones on its track. The rate of evaporation and quality of paths are used to update the pheromone amounts. In subsequent iterations, the ants follow the path with the highest pheromone intensity, allowing them to converge toward a close-optimal solution [

15,

44,

56,

57].

Several researchers have developed algorithms to generate composite services in the shortest time. For instance, Yu et al. [

15] proposed ACO-WSC and greedy-WSC to perform WSC in an MCE. Greedy-WSC selects the cloud providing the greatest number of required services and continues this process until all requirements are met. In ACO-WSC, each ant selects a random node in the graph and then searches for the next node based on pheromone and heuristic information on the connected edges to obtain optimal cloud combinations.

Alayed et al. [

44] presented a novel ACO algorithm that increases convergence speed while avoiding premature convergence by utilizing the swap concept. To increase the chance for exploration, a multi-pheromone ACO was used, where each pheromone represents a single QoS value. Dahan [

43] suggested a multi-agent system (MAS) using an ACO algorithm to identify a suitable candidate service matching user requirements. The MAS utilizes different agents to perform a distributed search quickly.

Cuckoo Search Algorithm (CSA) is a novel evolutionary algorithm inspired by the parasitic behavior of cuckoo species, which lay their eggs in the nests of other birds. CSA involves searching for nests with eggs that resemble the cuckoo’s own. The cuckoo locates the ideal nest and lays its eggs there without being detected by the nest owner. If the nest owner or host bird identifies the cuckoo’s eggs, it will discard them [

58].

Wang et al. [

50] introduced a two-phase method to combine credible services based on QoS. In the first phase, service providers’ ability to provide the requested services is evaluated. In the subsequent phase, a modified CSA is applied to perform multi-objective service composition. Kurdi et al. [

16] introduced the problem-dependent MultiCuckoo algorithm, which maintains a list of previously combined services. To reduce computation time, this approach uses a similarity algorithm to compare user requests with the list, ensuring user demands are met without examining many clouds. Ghobaei-Arani et al. [

9] suggested a CSA that considers both service and network QoS for service composition in geo-distributed cloud systems.

2.2.2. Physics-Based Methods

SA is a physics-based approach for solving service composition problems that mimic the annealing process in metals [

59]. Liu et al. [

60] modeled a long-term quality-oriented service-based composition problem as an optimization problem, using meta-heuristic methods like GA, SA, and TS to find solutions. Deng et al. [

61] presented an SA algorithm that minimizes energy consumption and risks to achieve an optimal mobile service composition. This approach accounts for the mobility of both service providers and requesters to reduce the risk of failure. Niewiadomski et al. [

62] proposed two methods using generalized extreme optimization and SA techniques to solve the service composition problem. Each algorithm generates an initial population by exploiting a satisfiability modulo theory (SMT)-based procedure. To create an optimal composition service, the algorithms apply either SA or GEO to the initial population.

2.2.3. Chemistry-Based Methods

In recent years, several chemistry-inspired techniques have been introduced to enable distributed and efficient dynamic service composition. These methods, inspired by concepts such as chemical reactions, provide a flexible and adaptable means of combining services within a dynamic MCE [

63,

64]. Banatre et al. [

63,

64] proposed a framework for efficient service composition centered around chemistry-inspired techniques, including a chemical metaphor in which services combine and interact dynamically, akin to reactive chemical substances. Likewise, Di Napoli et al. [

65] developed a chemical reaction model to dynamically address workflow requirements.

Viroli and Casadei [

66] developed a coordination model for chemical reaction-based self-organizing structures called biochemical tuple spaces. Furthermore, Fernández et al. [

67] created a chemistry-inspired workflow management system, emphasizing the decentralization of composite web service execution. Wang and Pazat [

68] created chemistry-inspired middleware to enable self-adapting service composition. Additionally, Angelis et al. [

69] applied a chemical-model approach to pervasive systems, using distributed data-sharing spaces for real-time, adaptive service compositions that respond dynamically to service addition and removal.

2.3. Hybrid Methods

Several researchers have attempted to address the limitations of individual algorithms by leveraging the advantages of other algorithmic features. Ko et al. [

70] proposed an efficient hybrid QWSC method integrating SA and TS for constructing and running service composition systems in mobile cloud environments. Their algorithm ensures constraint-compliant service composition plans while minimizing search times and fulfilling clients’ QoS requirements. Spezzano [

71] introduced a multi-objective PSO approach based on the crowding distance technique (MOPSO-CD) that selects a service while considering the dynamic characteristics of QoS during runtime. This approach solves the QoS-aware dynamic service selection problem using two different algorithms. MOPSO-CD is used to traverse the topology and find the best candidates for composite services, while the ant-based clustering technique is used to create and manage a service pool to lower the problem’s size by grouping services with equivalent functionality. This approach is highly scalable for large-scale problems.

Seghir and Khababa [

48] proposed a hybrid algorithm combining GA and FOA to solve QoS-aware service composition problems. GA employs an innovative roulette wheel for efficiency, while FOA provides local search capabilities, balancing exploration and exploitation. Khanam et al. [

72] introduced a hybrid approach combining ABC and PSO to prevent PSO from converging prematurely and to decrease the laborious updating of data in ABC to enable large-scale service composition. Similarly, Bhushan et al. [

51] suggested a hybrid PSO (HPSO) coupled with FOA to prevent PSO for QoS-based service composition in cloud environments from converging prematurely. This strategy employs Pareto optimal solutions to increase the HPSO method’s rate of convergence. The PSO searches globally for an optimum solution, while the FOA conducts local searches that reduce computing time and speed up convergence, respectively.

Other Significant contributions include hybrid approaches such as Sefati and Halunga’s [

73] method, which combines the GA and ABC algorithms to enhance QoS-based cloud service composition. Using this approach, GA initially selects services that are then further refined by the ABC algorithm to satisfy customer needs. Dahan and Alwabel [

74] integrated ABC and CSA algorithms for service composition. Their approach enhances the performance of weaker bees using cuckoo agents. While ABC is efficient, it suffers from premature convergence issues – a limitation that is mitigated by inclusion of CSA. Bei et al. [

75] employed a multi-pheromone technique with GA mutations to improve the ACO approach for QoS-aware multi-cloud service composition, minimizing the risk of local optima. Jayaudhaya et al. [

76] combined the GA and ACO algorithms to create a hybrid algorithm for efficient service composition in an MCE. They reported a significant improvement over traditional GA and ACO methods due to the use of adaptive parameter tuning, where GA dynamically adjusts ACO parameters to improve flexibility and responsiveness to meet QoS requirements. Arasteh et al. [

77] proposed a QoS-aware approach using an improved ant lion optimization algorithm to select optimal services from a pool of pre-existing services.

2.4. Discussions

The reviewed literature indicates that most existing methods focus on reducing NC [

5,

15,

16,

18,

26,

27] while often neglecting QoS features. Furthermore, the performance of many approaches, aside from Kurdi et al. [

16] and Mezni et al. [

26], has been validated using small datasets.

Table 1 provides a comparative analysis of service composition methods, in terms of minimum NC, minimum NES, and QoS features. To the best of our knowledge, no prior research has comprehensively addressed the dual objectives of QoS functionality and reduced NC. Therefore, there remains a critical need for algorithms that minimize the number of combined and examined clouds and services while maximizing solution quality. Although NIAs have shown promise for solving service composition problems, they suffer from limitations such as slow solution convergence and susceptibility to local optima. This underscores the need for novel approaches that provide faster service solutions and avoid local optima traps.

While chemistry-based algorithms have shown remarkable success in diverse optimization problems—from healthcare resource allocation [

79], to neural network training [

81], —their application in service composition remains largely unexplored [

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. These algorithms excel at handling complex, multi-constraint problems by mimicking chemical processes such as molecular interactions and electron shell transitions. Their proven effectiveness in solving related combinatorial challenges, particularly in association rule mining [

80] and quadratic assignment problems [124], suggests significant potential for addressing the unique challenges of service composition. However, existing approaches have not fully leveraged chemical principles for optimizing multi-cloud service composition, especially in minimizing combined clouds while maintaining QoS requirements. Our work bridges this gap by developing a novel chemistry-based algorithm that specifically targets the combinatorial complexity of service composition through the systematic organization and interaction patterns found in chemical systems.

3. System Design

This section introduces CA, which is inspired by the principles of electron movement and the periodic table.

Section 3.1 provides the chemical background underlying the CA method.

Section 3.2 outlines the design of the CA approach.

Section 3.3 explains the SF table, which arranges SFs based on their composition frequency and the total number of clouds.

Section 3.4 describes the service table, which ranks services based on their quality. Finally,

Section 3.5 details the process for searching the SF table to find a required SF.

3.1. Chemistry Inspiration

The CA approach draws inspiration from the periodic table and the movement of electrons, highlighting similarities between foundational chemistry principles and the design of the CA approach. The key innovation of our approach lies in its unique mapping between chemical concepts and cloud service composition. By organizing services in a periodic table-like structure based on composition frequency and establishing quality levels analogous to electron shells, we have created an original framework that significantly reduces the search space while maintaining solution quality. This represents a fundamental departure from traditional meta-heuristic approaches, introducing a new paradigm in cloud service composition.

3.1.1. Periodic Table

Since Mendeleev’s first periodic table in 1869, this organizational tool has driven the discovery and study of elements and materials [

82].

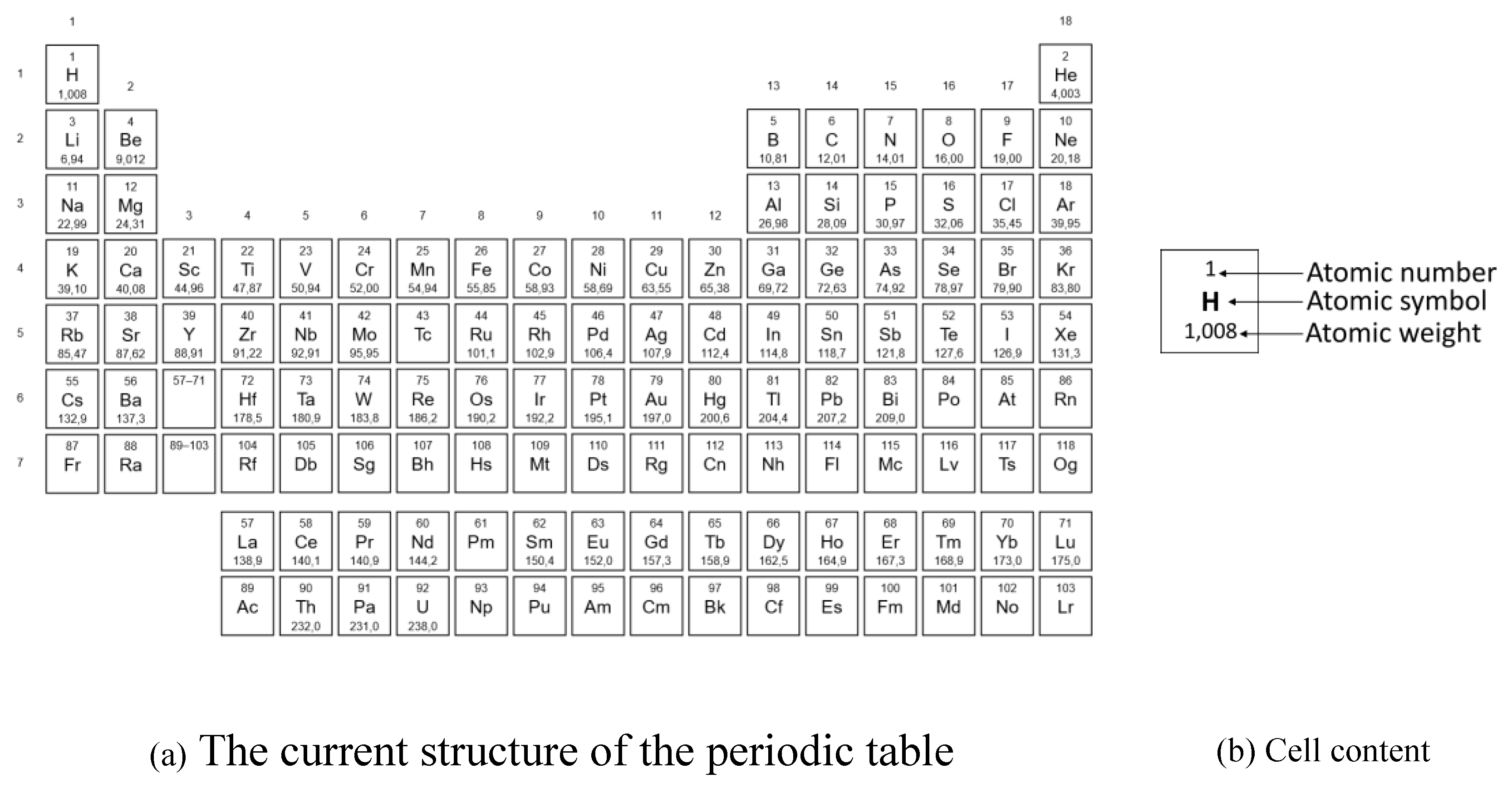

Figure 1.a depicts the current structure of the periodic table, which arranges and organizes chemical elements in order of increasing atomic numbers vertically and horizontally. As

Figure 1.b, each cell contains the following important information [

83,

84]:

Atomic number: the number of protons in an atom, which determines the element and its chemical behavior;

Atomic symbol: an abbreviation for an element (e.g., “C” for carbon);

Atomic weight: the average mass of an element.

Periodic table columns are commonly referred to as groups. The valence electrons, or electrons in the outermost shell of an element, are identical for every element in the same column. Hence, they react in the same ways physically and chemically. For example, Group 18 elements are all inert gases with eight valence electrons. Each row is called a period, and the period number refers to the number of electron shells. For example, hydrogen is in the first row and contains only one electron shell [

83].

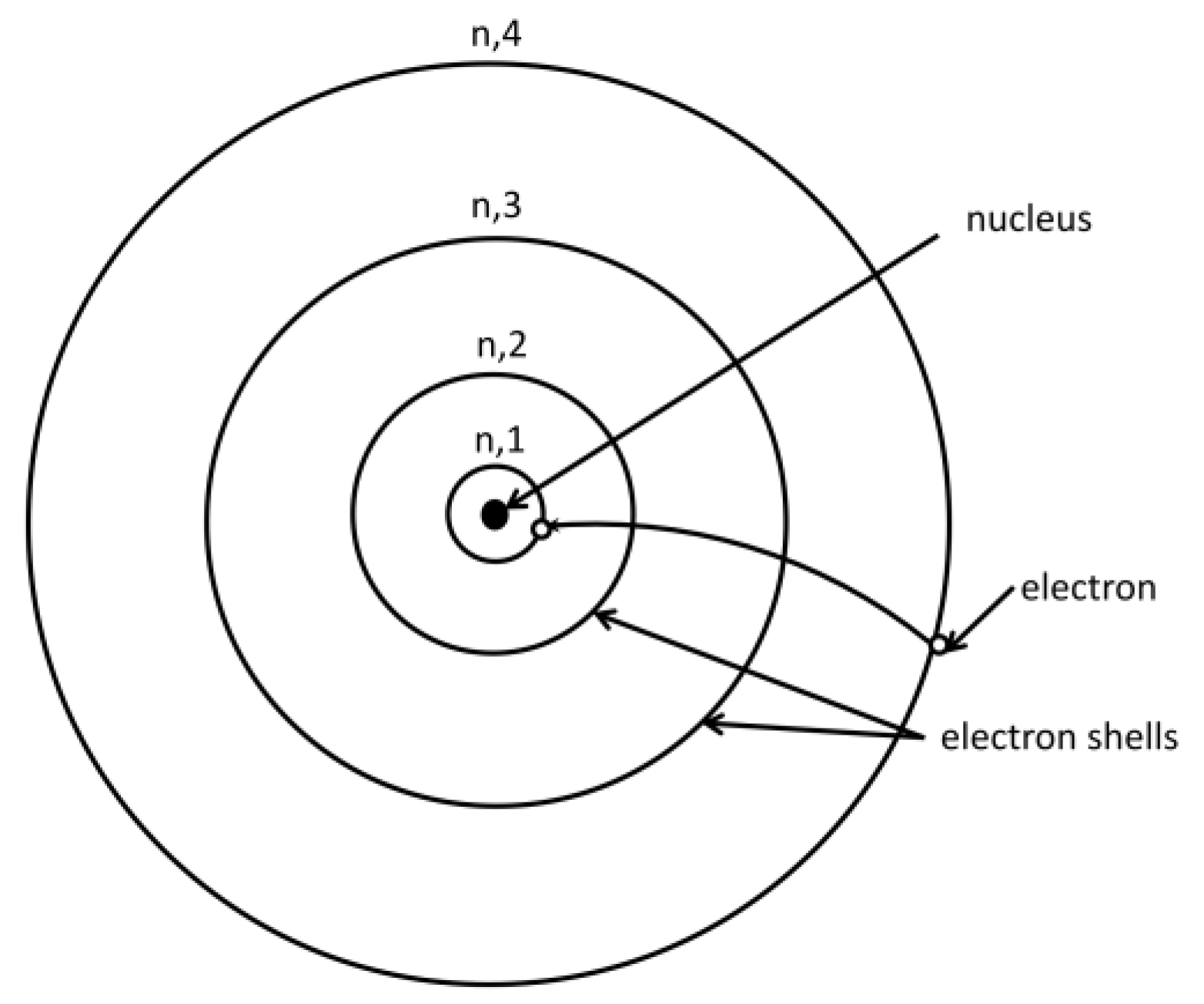

3.1.2. Electron Movements Among Shells

Every element is composed entirely of a single kind of atom. Atoms consist of a nucleus, including protons and neutrons, and an outer region where electrons move in shells around the nucleus. According to the Bohr model, electrons can only be located in allowed shells, each with a distinct energy level. Electrons closest to the nucleus have the lowest energy, while those further away have higher energy levels. Electrons can jump from one allowed shell to another by absorbing or emitting photons equal to the difference between the levels. An electron vanishes from the shell in which it is positioned and emerges again without ever being anywhere in between. Electrons absorb energy and jump to higher energy states [

83].

Figure 2 depicts an electron jumping from shell n = 4 to shell n = 1, resulting in a photon perceived as red light.

3.1.3. Analogies Between Chemistry And Chemistry Algorithm

The fundamental principles of the periodic table and electron motion inspired this work. Similar to how the periodic table groups elements based on atomic numbers, the proposed research organizes SFs in a table in reverse sequence based on their composition frequency. The SFs are arranged in rows according to the number of clouds containing them, analogous to the periodic table’s row-based arrangement of elements based on the number of electron shells. Frequently combined SFs are grouped in the same column, akin to the periodic table’s vertical grouping of elements with similar characteristics.

Services within a specific cloud and SF are grouped in a service table according to their QoS levels (very high, high, medium, and low). This arrangement mirrors the distribution of electrons in accordance with their energy levels.

Table 2 provides a mapping between components of the CA approach and the principles of the periodic table and electron movement.

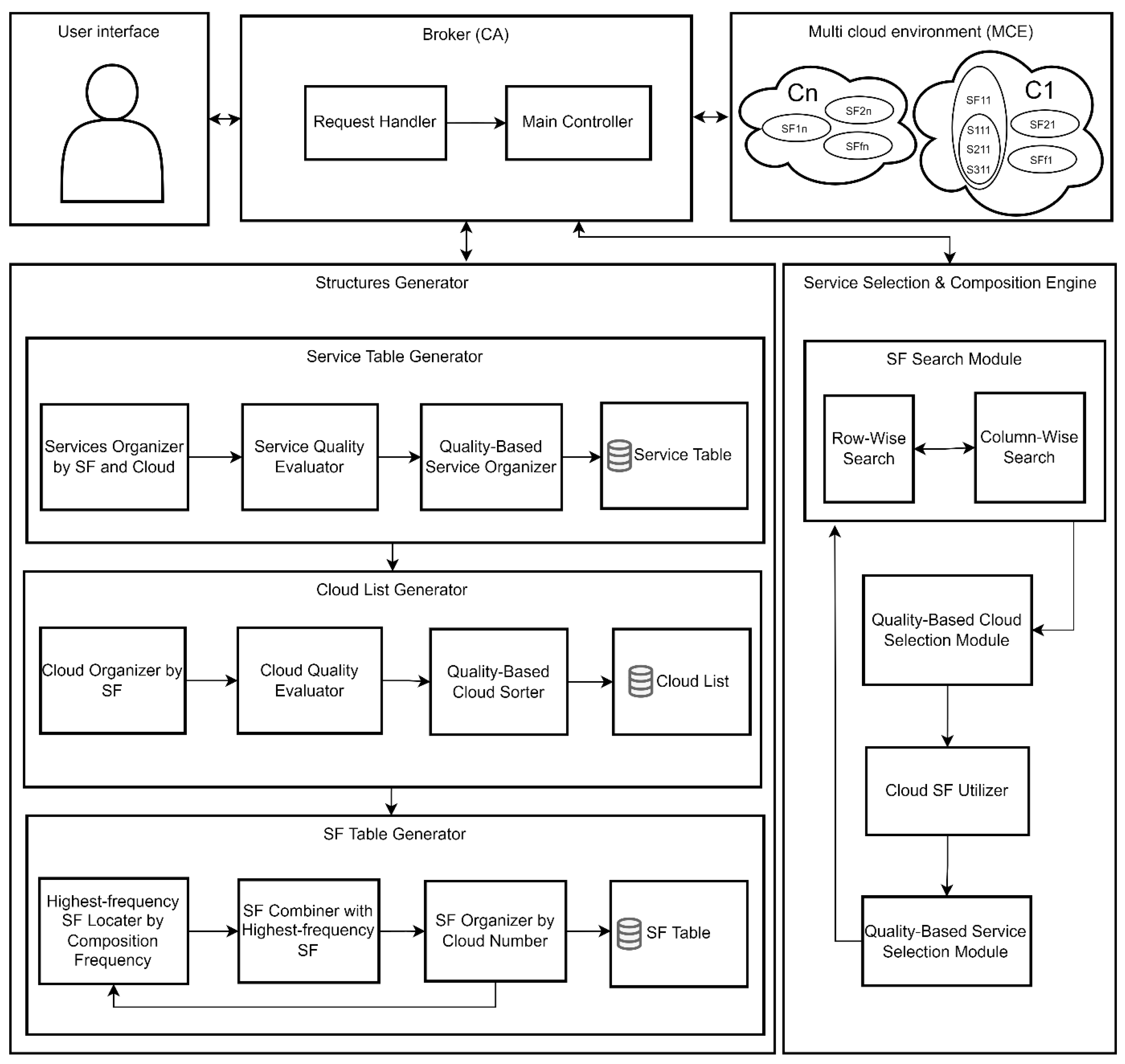

3.2. System Architecture

Figure 3 illustrates the system architecture which comprises the following key components:

Cloud services are arranged in an MCE [

18], consisting of multiple clouds (C), where C = {C1, C2, …, Cc}. Each cloud contains a collection of SFs, where SF = {SF1, SF2, …, SFf}. Each SF comprises a set of services (S), where S = {S1, S2, …, Ss};

The user interface facilitates the submission of user requests and the presentation of the resulting composite service. This functionality is managed by the Request Handler and the Main Controller. The Main Controller plays a pivotal role in coordinating the operations of the Structures Generator and the Service Selection and Composition Engine. Specifically, it is responsible for transmitting the outputs produced by the Structures Generator, such as the SF table, to the Composition Engine, while also ensuring the efficient processing of requests received from the Request Handler by the Composition Engine;

- 3.

The CA approach, particularly the Structures Generator, is responsible for generating an SF table and a service table in cases where these tables have not been previously established, as explained in

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4;

- 4.

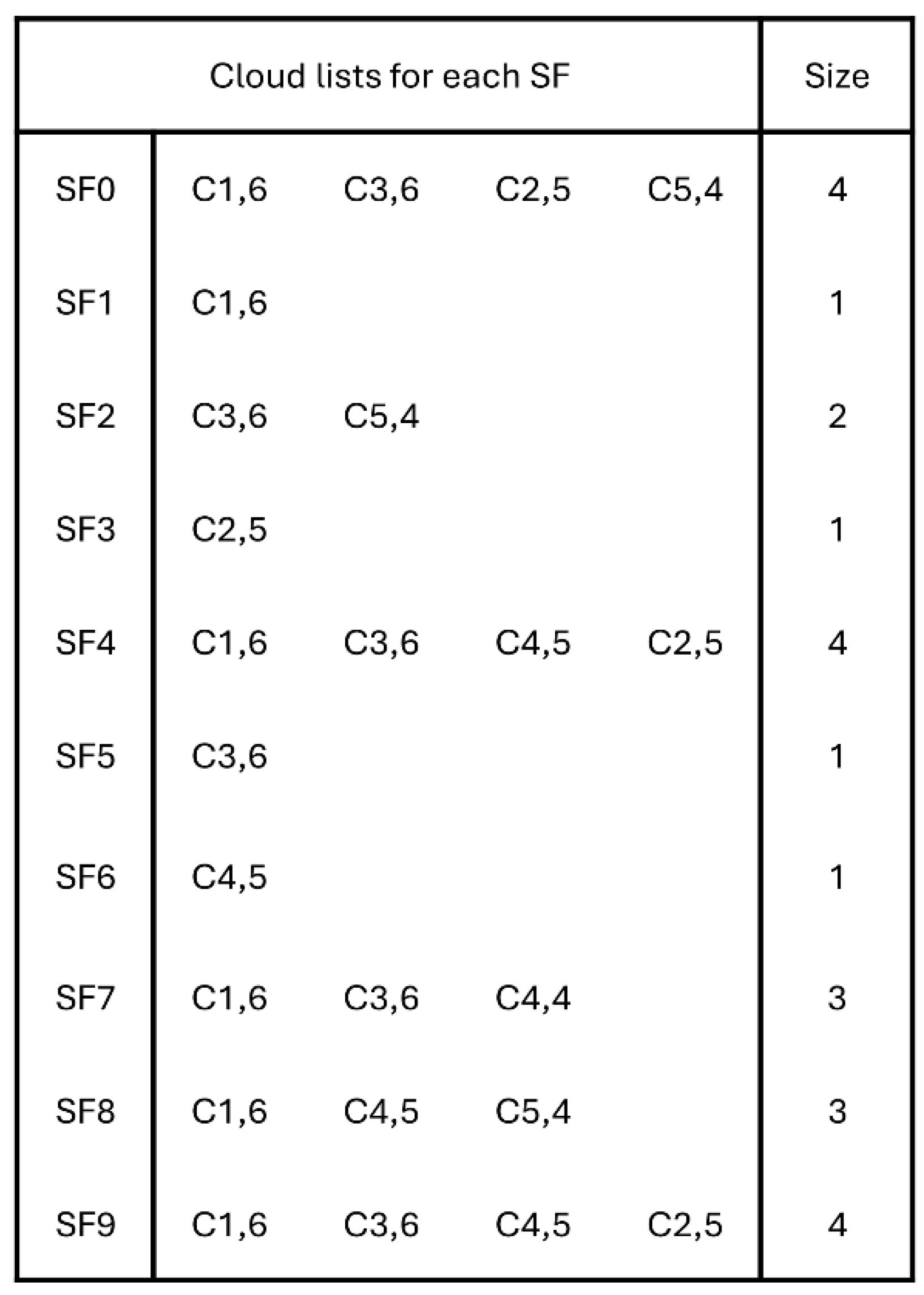

The Cloud List, a subcomponent of the Structures Generator, employs the Cloud Organizer to classify clouds based on SF, as illustrated in

Figure 4. Each SF maintains a systematically organized list of clouds in descending order of cloud quality. The sorting is performed by the Quality-Based Cloud Sorter, with cloud quality being assessed based on two factors: the number of SFs (Nb_SFs) associated with the cloud and the number of services present in the first three columns of the service table (QoS_1, QoS_2, and QoS_3), which correspond to very high, high, and medium quality levels, respectively. It is computed using Equation 1,

where weights assigned to the number of SFs and the number of services in each corresponding column are represented by the numerical values of the coefficients 0.3, 0.4, 0.2, and 0.1. Poor-quality services (QoS_4) are excluded. The computation process is entirely carried out by the Cloud Quality Evaluator.

- 5.

As explained in

Section 3.5, the CA approach searches the SF table for the requested SF using Service Selection and Composition Engine;

- 6.

Upon the selection of an SF, it is added to the composite list alongside the first cloud from its associated cloud list and the first service from the first column of the service table. If no service is available in the first column, the algorithm sequentially examines subsequent columns until a suitable service is identified. This selection process is governed by the Quality-Based Cloud Selection Module and the Quality-Based Service Selection Module, respectively. Once a service is integrated into a composite service, along with its associated cloud and SF, it is marked as unavailable for future compositions and subsequently removed from the service table. The removal of a service can influence the associated cloud’s quality or its availability within the SF's cloud list. Each removal prompts an update to the cloud’s quality, which may alter its ranking in the SF's cloud list. If the removed service is the last available entry in the service table for a particular cloud, the cloud may also be removed from the SF's cloud list as it can no longer provide the required SF. This, in turn, leads to an update in the SF table, where the row index of the affected SF is reduced by one, reflecting the cloud's inability to support the SF;

- 7.

Subsequently, the CA approach utilizes the selected cloud for other SFs. Following all the steps laid out in point 6, the entire process is carried out again to select a service after identifying the suitable SF. This iterative process continues until all requested SFs are sought within the selected cloud. This task is performed by the Cloud SF Utilizer;

- 8.

Steps 5, 6, and 7 are reiterated until all requested SFs are incorporated into the composite service.

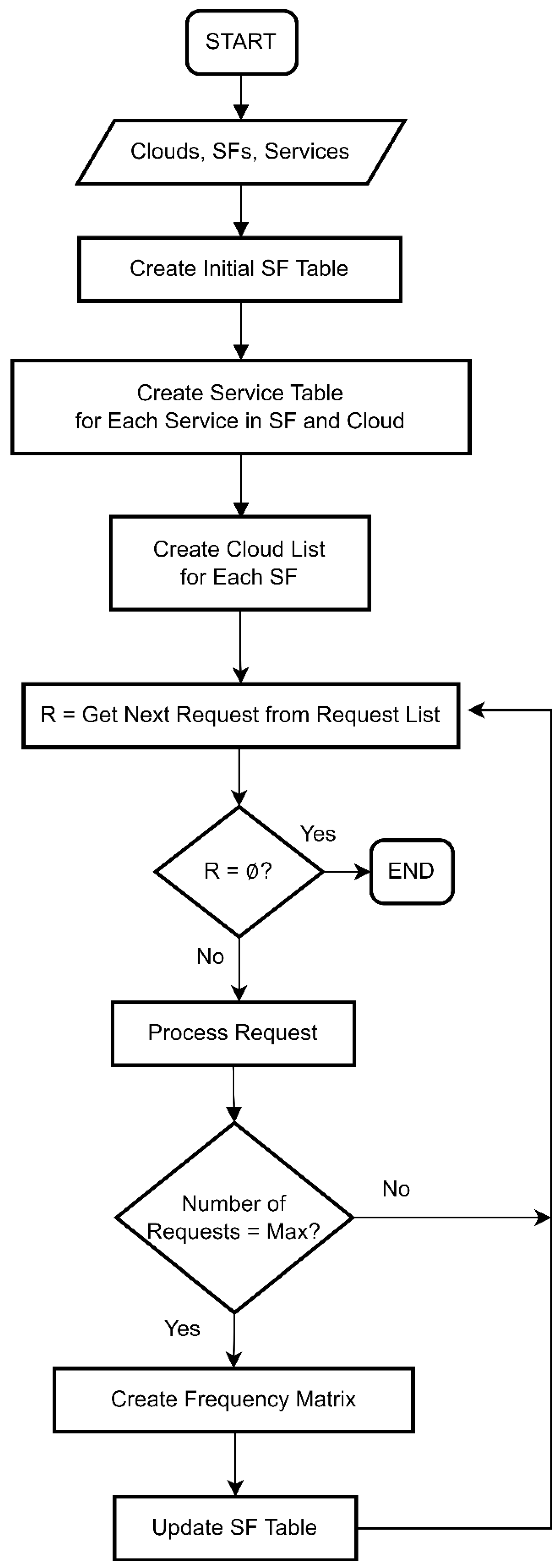

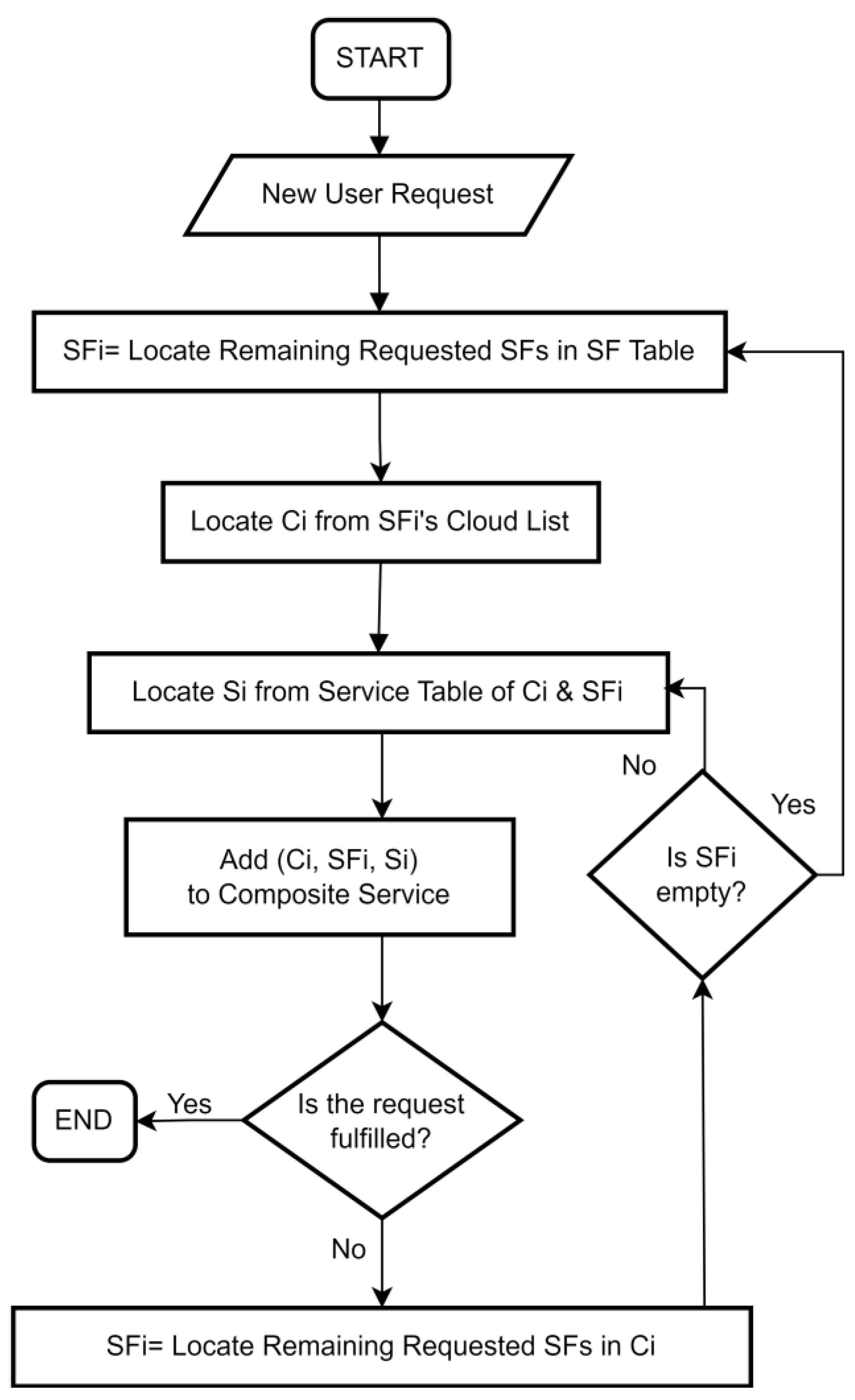

The main workflow of the system and the sequential stages involved in request processing are shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 respectively.

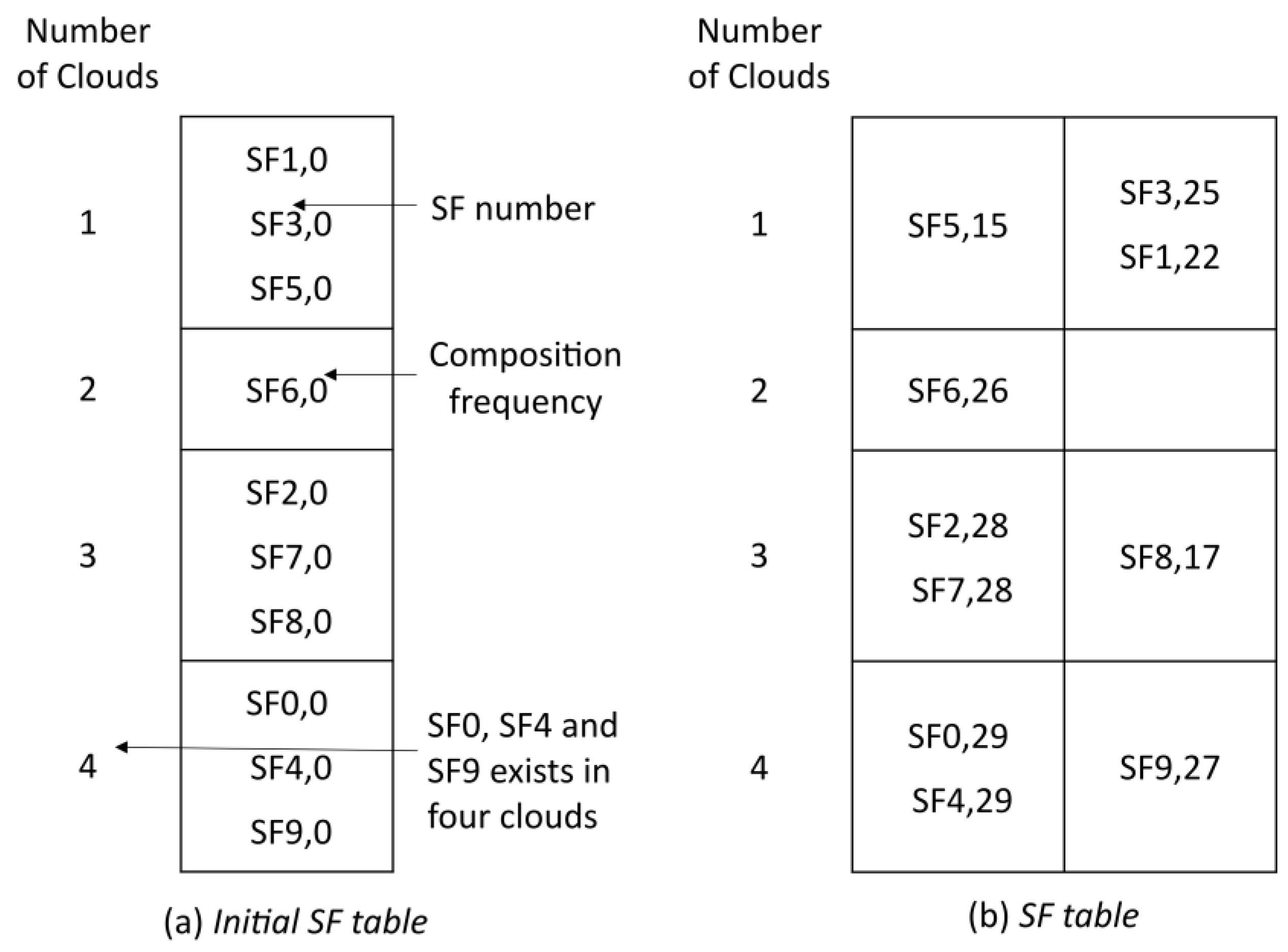

3.3. Generating The Service File Table

The SF table organizes SFs based on their composition frequency and the number of clouds, as depicted in

Figure 7. SFs in the SF table are denoted as SFf,y, where f denotes the SF number and y represents the composition frequency, that is, the number of times the SF is requested.

Each column in the SF table groups SFs that are frequently requested together, while rows represent SFs associated with a specific number of clouds. For example, the first row lists SFs available in a single cloud. Within each cell of the SF table, SFs are arranged in reverse order based on their composition frequency.

In this research, we suggest that the number of rows is determined by the maximum size of each SF cloud list. In contrast, the number of SFs (NSF) and a desired number of SFs per column (DSF) are used in Equation 2 to determine the number of columns in the SF table. For example, when NSF = 10 and DSF = 5, the table has two columns (10 / 5 = 2). We set the number of columns to one to generate the initial SF table, as depicted in

Figure 7.a. Each SF is placed in the correct row based on the number of clouds in which it exists. This task is performed by the SF Organizer. For example, SF1 and SF2 exist in one and three clouds, respectively, and so they are placed in rows 1 and 3. The number of columns required in the SF table is calculated using:

Once the CA approach generates a maximum number of composite services (assumed to be 30 in this example) using its initial SF table searching process, a frequency matrix is generated to create an updated SF table, as depicted in

Figure 7.b. This matrix indicates how often SFs are requested with other SFs (

Table 3). For example, SF1 is present in 22 out of 30 composite services, whereas it is only composed with SF0 14 times.

The CA approach initiates by identifying the SF with the highest frequency through the frequency matrix, utilizing the Highest-Frequency SF Locator. Subsequently, the SF table is updated to incorporate this SF along with additional SFs that collectively meet the specified frequency threshold, as determined by the SF Combiner. The new entries are placed in the first column of the SF table, distributed across rows based on the number of clouds. This process is repeated until all SFs are added to the SF table. Any SFs that do not fit into a column are compared against the highest-frequency SF in each column and assigned to the column where they have the greatest frequency. The frequency threshold is calculated using Equation 3, with a co-occurrence threshold of 70% assumed in this research, representing the percentage at which an SF co-occurs with the highest frequency SF.

For instance, the algorithm updates column 1 with SF0 (the highest-frequency SF) and other SFs from the same row that meet the threshold frequency of 21 of higher. It only considers the first highest-frequency SF. Thus, SF4 was not selected despite its value being the same as that of SF0. SF9, with the next highest frequency, is placed in the second column along with corresponding SFs. Remaining SFs, such as SF5 with a frequency of 15 (below the threshold), are compared to the highest-frequency SFs in existing columns and assigned accordingly. In this case, the proposed algorithm compares the frequency of SF5 with that of SF0 and SF9, resulting in its addition to column 1 due to its higher frequency.

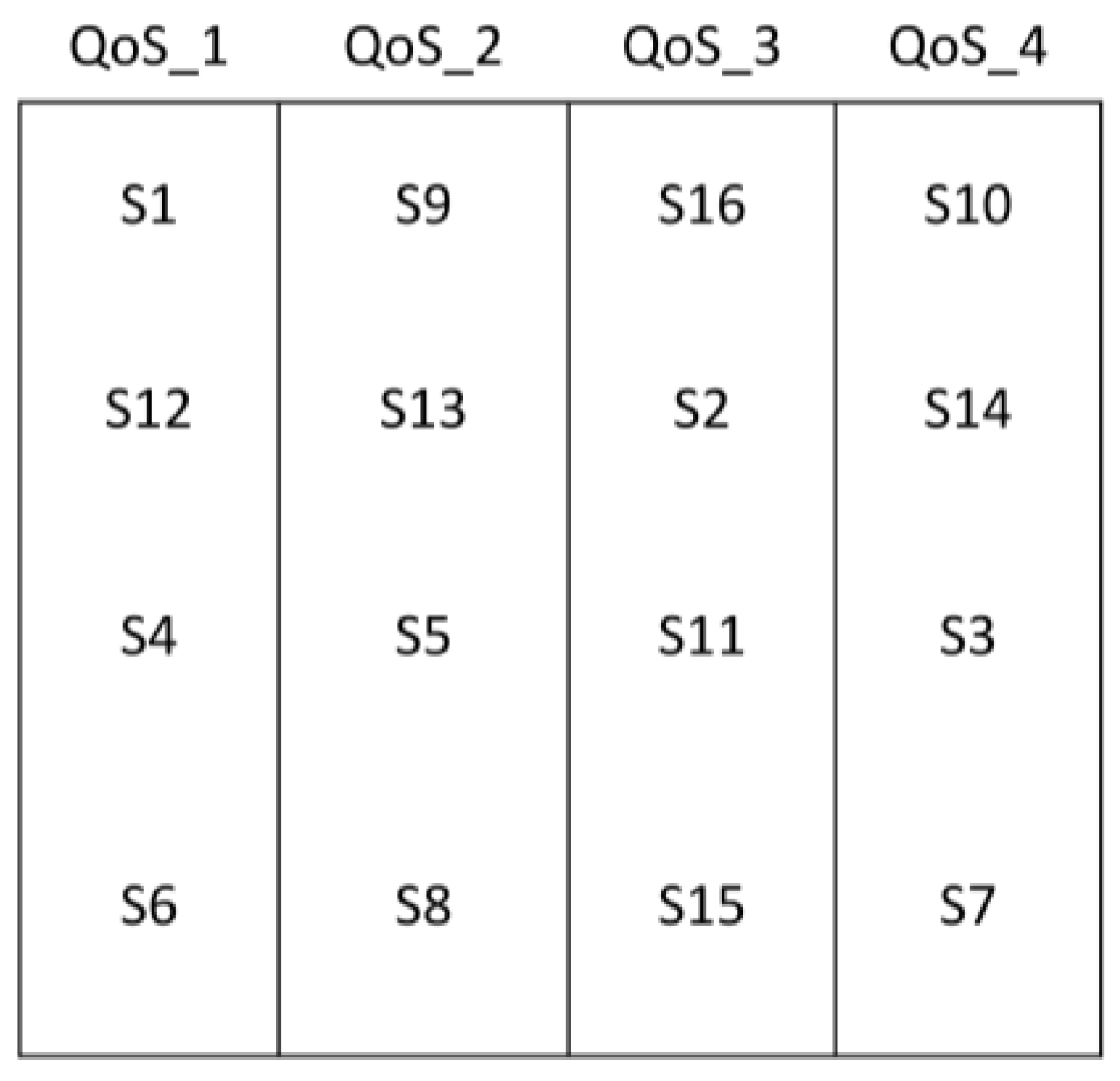

3.4. Generating The Service Table

A service table was created to display services and their QoS levels, as shown in

Table 4. We primarily focus here on the four most important QoS features: two positive QoS features (reliability and availability) and two negative QoS features (cost and response time). Higher values indicate decreasing quality, whereas lower values indicate greater quality for negative features. Conversely, for positive features, higher values indicate higher quality, while lower values indicate worse quality [

9,

32,

43].

Each SF within a given cloud is associated with a service table, which is managed by the Service Organizer. Columns represent QoS level types – very high (QoS_1), high (QoS_2), medium QoS_3), and low (QoS_4) – spanning the value ranges 0.9–1, 0.8–0.79, 0.6–0.7, and 0–0.69, respectively, as depicted in

Figure 8. Services are organized in columns within the service table according to their quality, a process executed by the Quality-Based Service Organizer. For instance, the service with the highest quality is positioned in the first column, surpassing the other services in that column.

Service quality was assessed by summing the QoS metrics, as outlined in Equation 4. This computation is carried out by the Service Quality Evaluator. This approach differs from previous methods [

8,

86], which calculate service quality by dividing the total positive QoS aspects (e.g., reliability and availability) by the total of negative QoS aspects (e.g., cost and time). These approaches emphasize the importance of decreasing negative QoS values and increasing positive QoS values. Based on several experiments, the division approach sometimes misinterprets service quality, particularly when QoS values are close to extremes (e.g., either 1 or 0.1). The proposed modification provides more accurate results by maximizing service quality.

Here,

and

represent the assigned weights and normalized QoS values of A, R, T, and C. The sum of all weights typically equals 1. The QoS values are normalized to a uniform scale of values between 0 and 1. Negative and positive QoS parameters are computed using Equations 5 and 6, respectively.

Here, Q stands for the QoS parameter, while NQ- and NQ+ are the normalized values of the negative and positive QoS service parameters, respectively. Furthermore, as shown in Table

7, SQ- and SQ+ denote the highest and lowest values of the QoS parameters [

9]. Each QoS parameter is assigned a distinct weight value to emphasize its importance. Here,

are assigned the weights 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, and 0.25, respectively.

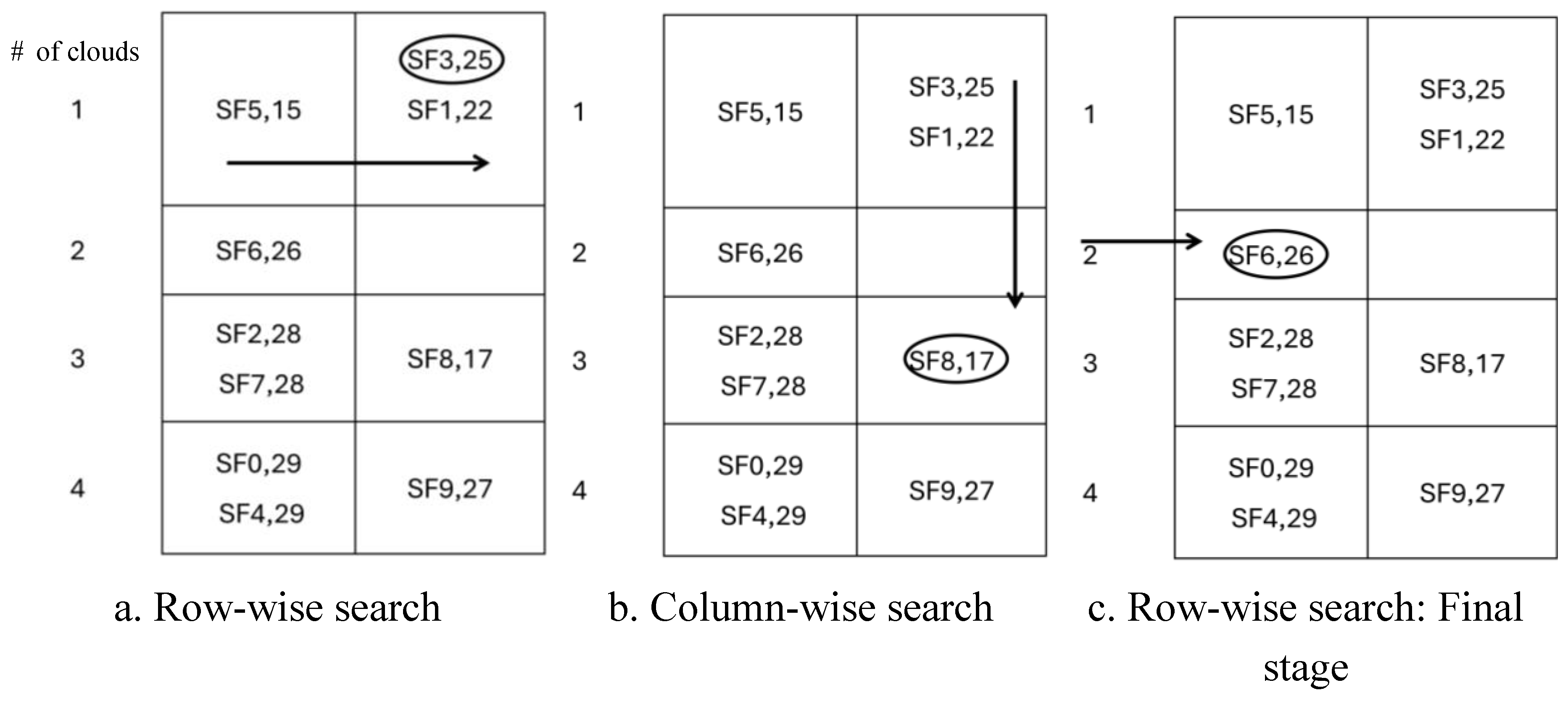

3.5. Searching For Service Files

Upon receiving a user request, the proposed CA algorithm initiates a search for the requested SFs in the SF table, examining each row sequentially starting from row 1. This process is managed by the Row-Wise Search module. Upon locating an SF, it is appended with a cloud and service as explained in section 3.2, particularly in step 6. As mentioned in section 3.2, specifically in step 7, the CA approach then searches for the remaining SFs within this SF's cloud. If the remaining SFs are not located within the current cloud, the algorithm proceeds to search for them within the current column, a process handled by the Column-Wise Search module. Once a column has been fully examined, it is added to the list of reviewed columns to prevent redundant searches. This process continues until all requested SFs are located, except for the last remaining one. The algorithm repeats step 6 for the last remaining SF, appending a cloud and service, as a result, the composite list becomes ready for delivery to the cloud user.

To illustrate the search process, consider the example shown in

Figure 9. In this scenario, the algorithm searches for SF8, SF3, SF0, SF2 and SF6. The search begins row-wise, identifying SF3 in the second cell of the first row (since no requested SF is found in the first cell). The first cloud in SF3's cloud list is C2 as illustrated in

Figure 10, where the proposed algorithm thoroughly searches for the remaining SFs and finds SF0. Continuing the search process for other SFs in the same column, the algorithm locates SF8 in C1, which is missing the remaining SFs (SF6 and SF2). After exhausting the search in the column without finding the remaining SFs, the algorithm resumes searching from its stopping point, that is, row 2. Once locating SF6 in C4 which doesn’t contain SF2. Once SF2 is the only remaining SF, the searching process in SF-table stops. The user receives the composite service following the successful execution of step 6 for SF2 to add C3 and the corresponding service.

4. Experimental Methodology

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation framework to validate the effectiveness of the proposed Chemistry-based Approach (CA) for multi-cloud service composition. The evaluation examines the algorithm's performance across multiple dimensions, including resource utilization efficiency, computational overhead, and quality of service optimization. Through controlled experiments, we demonstrate the algorithm's effectiveness in minimizing combined clouds while maintaining high QoS standards, its computational efficiency in examining clouds and services, and its scalability across different problem sizes.

4.1. Experimental Setup

Several controlled environment experiments were carried out to evaluate the effectiveness of the CA approach. The experiments were conducted on an Intel Core i7-10700K processor with 32GB RAM running Ubuntu 20.04 LTS, with the CA algorithm implemented in Python 3.8. The CA algorithm was tested in a simulated environment featuring varying numbers of clouds, SFs, and services.

Table 5 summarizes three experiment scenarios: small, moderate, and large setups, while the detailed descriptions of these experimental settings are presented in

Table 6.

Table 7 outlines the QoS value ranges used for each service. To evaluate the algorithm's scalability, experimental scenarios featured increasing numbers of clouds, SFs, and services, with the number of user requests ranging from 10 to 80.

The experimental datasets were generated using controlled random generation, with QoS parameters following normal distributions within realistic ranges as detailed in Table 7. To ensure comprehensive testing, each experiment was repeated 30 times, with results reporting means and standard deviations at a 95% confidence level.

4.2. Performance Metrics

For each scenario, we assessed five performance metrics: the total number of clouds utilized in the composite service (NC), the overall number of clouds examined throughout the service composition process (NEC), the total number of services examined to fulfill requests (NES), execution time, and fitness. The fitness metric calculated using Equation 4, evaluates the overall quality of the composite service by computing QoS metrics as shown in

Table 8.

4.3. Initial Configuration of the Considered Algorithms

To provide comprehensive comparative analysis, we evaluated the CA approaches against three state-of-the-art service composition algorithms: GA, SA, and TS. The GA implementation used a population size of 100 with crossover probability of 0.8 and mutation probability ranging from 0.2 to 0.9. The SA algorithm was configured with an initial temperature of 100,000 and a cooling schedule ranging from 0.15 to 0.9, while the TS implementation employed a tabu tenure of 20 to 100 steps. The CA and CA2 algorithms were configured with a fixed number of columns in the SF table, set to 1 and 2, respectively. The CA algorithm represents the initial configuration, utilizing a single column, while the CA2 algorithm reflects the state after processing the maximum number of requests, with two columns.

Table 9 presents the complete configuration details for all algorithms considered in this study.

Each algorithm was executed for 250 iterations per request to ensure fair comparison. To prevent loss of the best-found solution, elitism was implemented in all algorithms except CA and CA2. The experimental results and their analysis are presented in

Section 5, demonstrating the effectiveness of our approach across different operational scenarios and performance metrics.

5. Results And Discussion

The following section outlines the findings of the CA approach for service composition in an MCE, as detailed in

Section 5.1.

Section 5.2 provides a comprehensive analysis of these results, evaluating key findings to validate the algorithm's effectiveness across diverse scenarios. The analysis highlights the algorithm's efficiency and offers insights into its scalability, reliability, and applicability to various service composition problems, particularly in complex and large-scale environments.

5.1. Experimental Results

To evaluate service composition in a controlled setting, we carried out a series of experiments in an MCE, utilizing the CA approach and additional benchmark algorithms in three different experimental scenarios (shown in

Table 5). We evaluated the algorithm's performance in terms of execution time, fitness, NC, NEC, and NES. Three well-known service composition algorithms, SA, GA, and TS, were employed as benchmarks in our research.

The following subsections describe the performance metrics for each scenario.

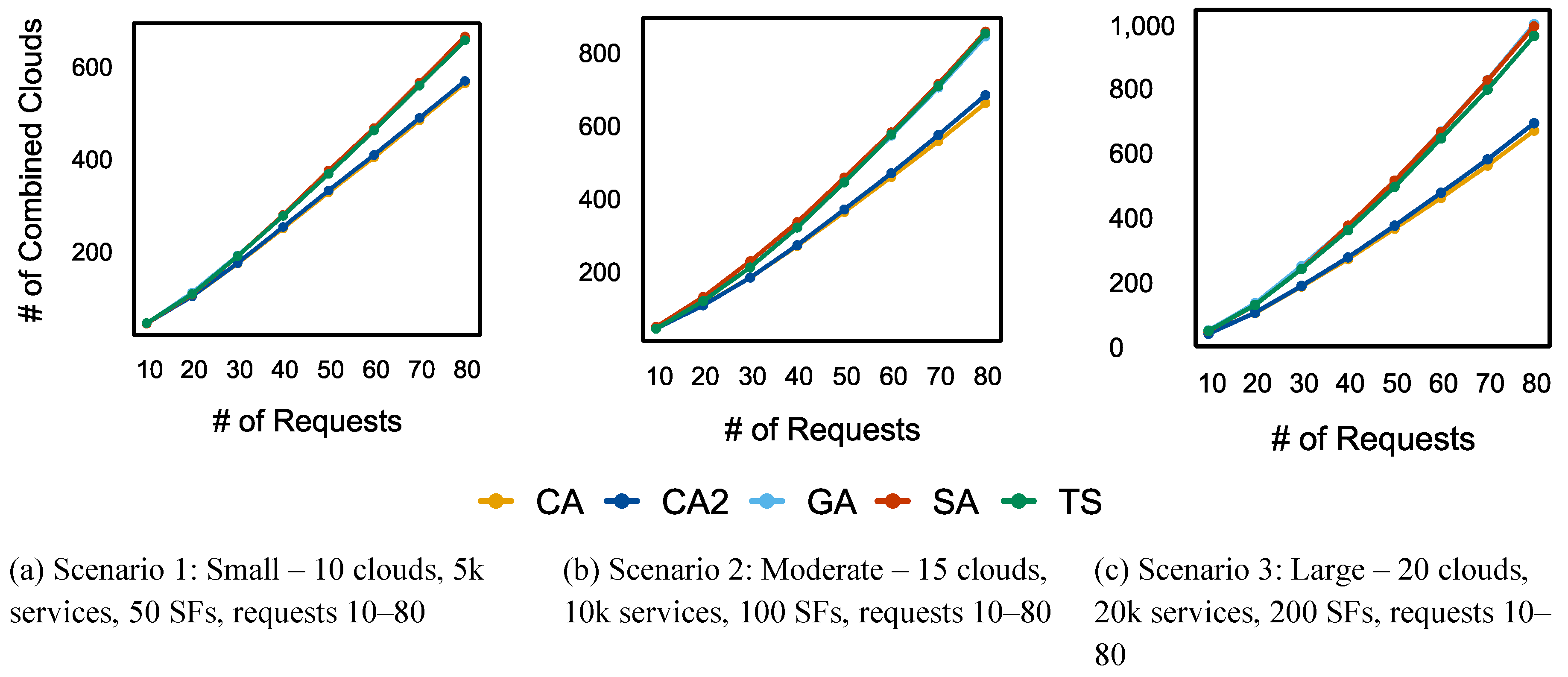

5.1.1. Number Of Combined Clouds

Figure 11 shows the algorithms' performance evaluation of the NC. The algorithms showed a consistent increase in NC as the number of requests rose. The CA and CA2 algorithms achieved the lowest NC values across all experimental scenarios, with CA slightly outperforming CA2, as the number of requests increased from 30 to 80. In contrast, GA, TS, and SA displayed similar results but examined more combined clouds than CA and CA2. Among these, TS algorithm exhibited a slightly lower NC value in all scenarios when compared to GA and SA.

As the total number of requests reached 80, the NC gap between CA/CA2 and the other algorithms became noticeable, increasing by approximately 100 in scenario 1, 200 in scenario 2, and 300 in scenario 3.

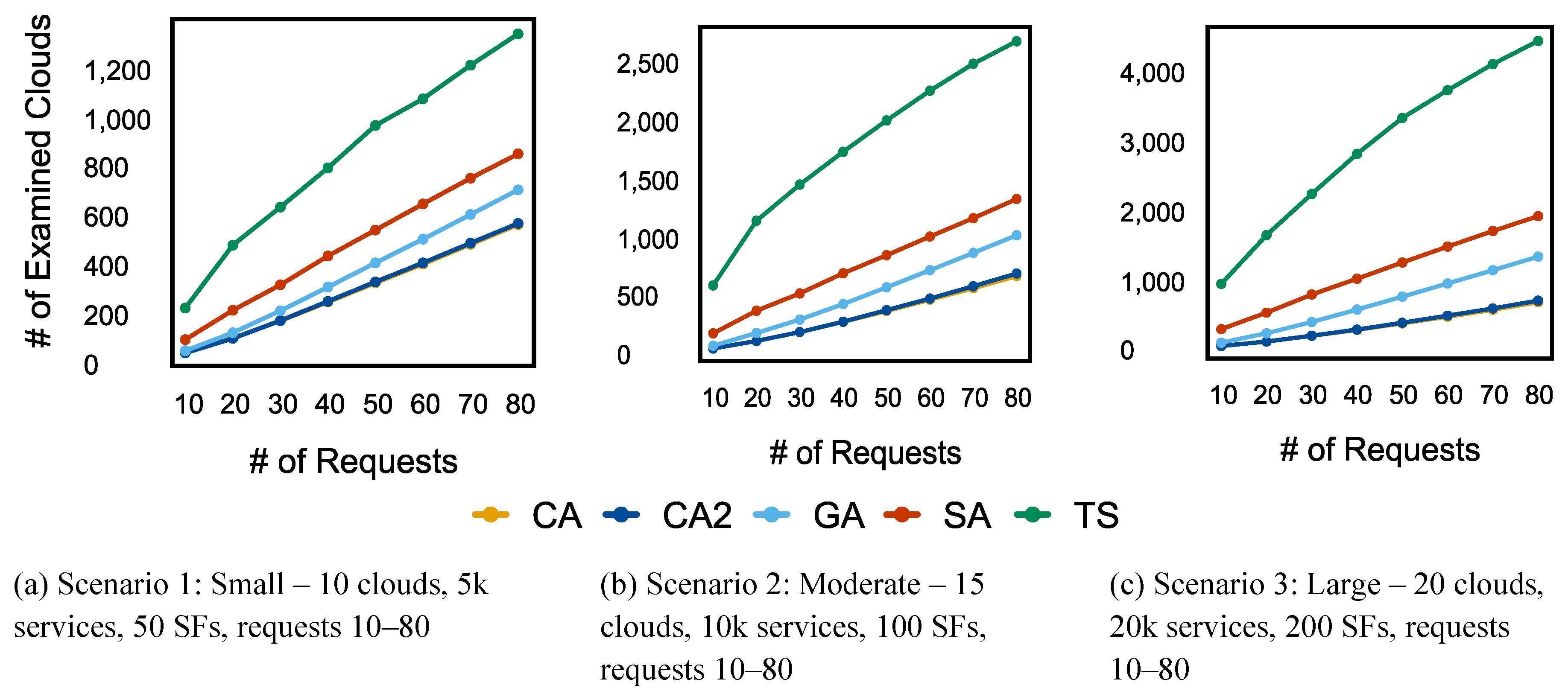

5.1.2. Number Of Examined Clouds

Figure 12 illustrates the NEC performance of the proposed CA approach and benchmark algorithms across various scenarios. As the number of requests increased, these algorithms showed significant increases in NEC. CA and CA2 consistently achieved the lowest NEC values, indicating superior computational efficiency. TS displayed poor performance, reflecting higher computational costs, while GA performed moderately compared to the other algorithms. Notably, SA examined more clouds than GA yet maintained good performance.

It is also worth noting that the NEC gap between CA/CA2 and TS widened significantly across various scenarios, reaching approximately 800, 2000, and 4000 for scenarios 1, 2, and 3, respectively, when processing 80 requests. This demonstrated the computational efficiency of CA compared to the other algorithms.

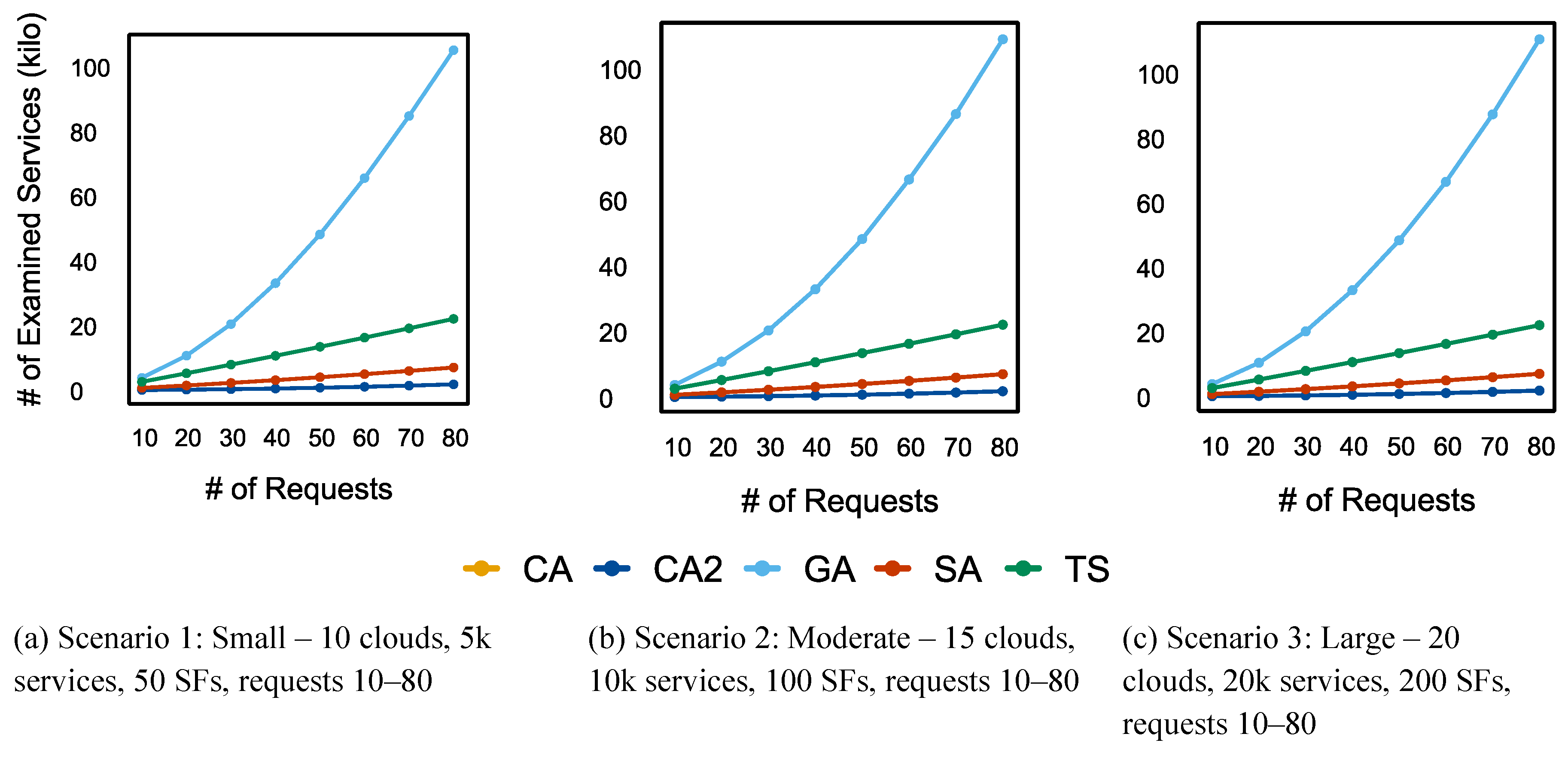

5.1.3. Number Of Examined Services

The NES performance evaluation of the suggested and benchmark algorithms is presented in

Figure 13. While all algorithms showed an increase in NES as the number of requests grew, CA and CA2 maintained the slowest rate of increase. Both algorithms consistently examined the fewest NES, even at higher request levels. Although not as effectively as CA/CA2, SA also performed well. TS exhibited moderate performance, examining fewer services than GA but more than SA and the CA algorithms. GA consistently examined the highest NES, with an exponential increase as the number of requests rose.

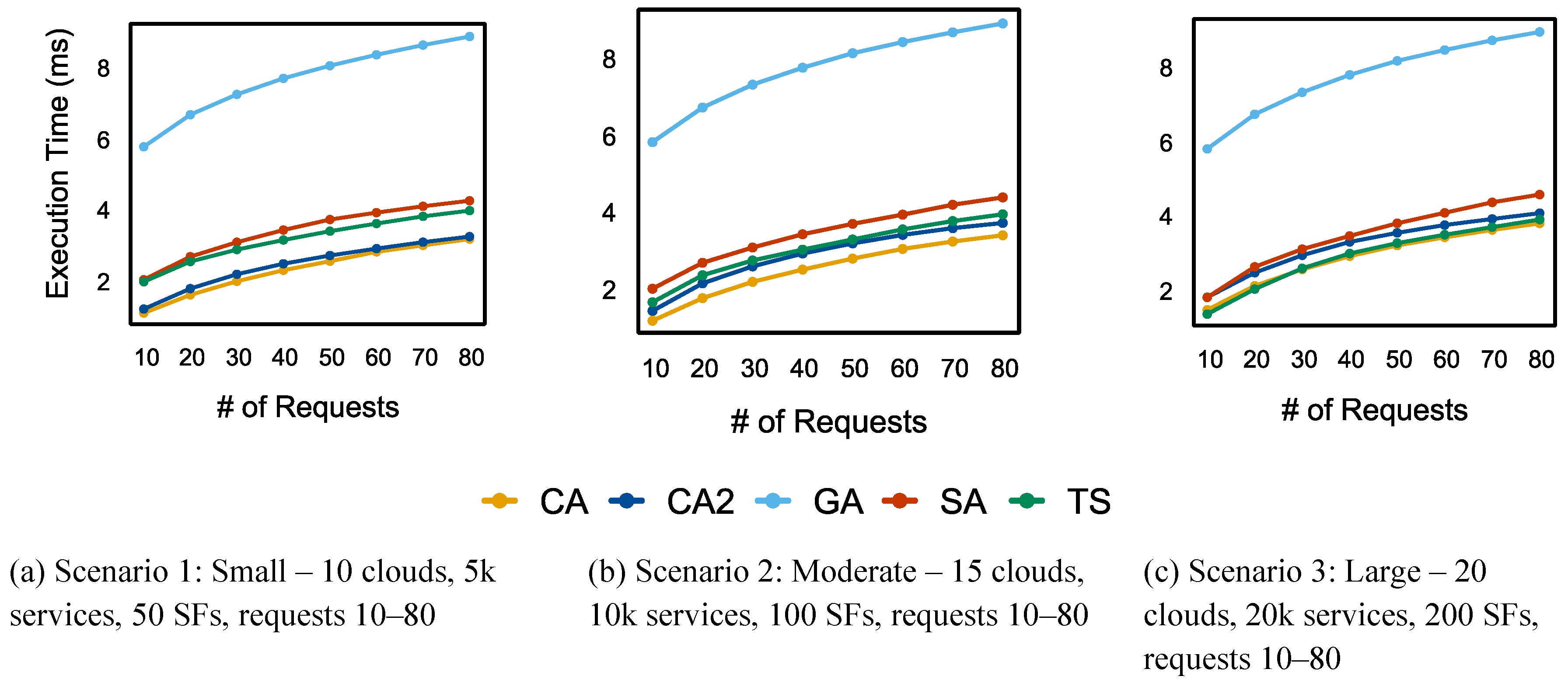

5.1.4. Execution Time

Figure 14 compares the execution times of the algorithms. Execution time increased for all algorithms as the number of requests rose. In both scenarios 1 and 2, CA had the shortest execution time, followed by CA2. The TS execution time increased by nearly 6 ms as the total number of requests increased. TS and SA displayed similar execution times, while GA consistently had the longest execution time.

The execution times of all algorithms in scenario 3 are shown in

Figure 14.c, with TS and CA having the shortest execution times, followed by CA2 and SA. GA exhibited consistent performance with the highest execution time.

The execution times do not account for the time required to generate the support utilized in CA/CA2 (e.g., SF table, service table, frequency matrix, cloud list). Even when including this preparation time in the overall execution time with 80 requests, CA and CA2 maintained the same performance pattern. In scenarios 1 and 2, CA had the fastest execution time, followed by CA2. Similarly, CA and TS achieved the shortest execution time in scenario 3. CA2 continued to rank third in terms of performance, following TS and CA.

Table 10 details the amount of time required to generate the structures for CA and CA2.

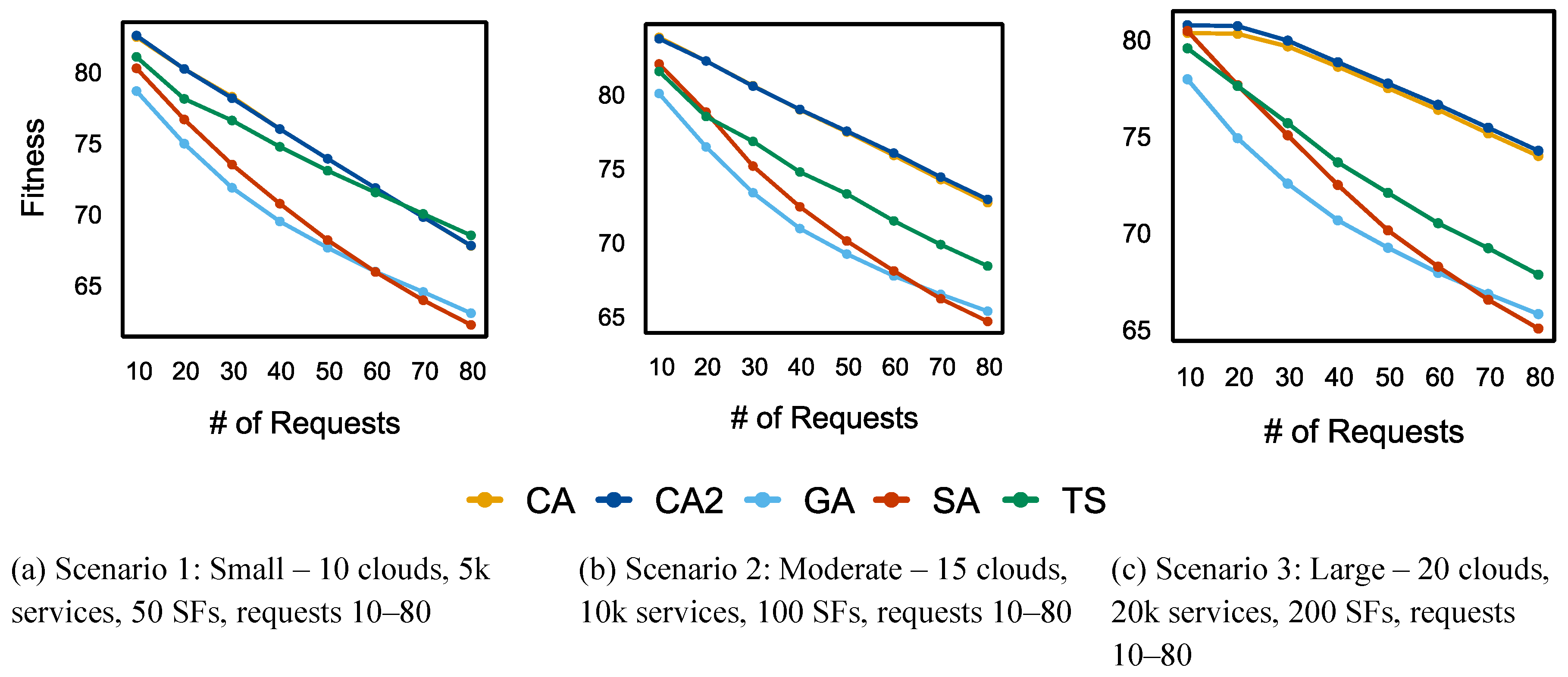

5.1.5. Fitness

Figure 15.a depicts the performance evaluation of the proposed and benchmark algorithms in scenario 1 based on fitness metrics. For a low number of requests, the CA and CA2 algorithms demonstrated high fitness values. However, as the number of requests increased, their fitness values decreased. After processing 70 requests, the fitness levels of CA and CA2 fell below that of TS. At the 70-request mark, TS performance was on par with that of the CA and CA2 algorithms. Beyond this point, the TS fitness values increased. SA initially showed greater fitness, but its performance declined once the number of requests reached 60 or more. GA, which initially had lower fitness, eventually outperformed SA after 60 requests.

Figure 15.b and

Figure 15.c present the fitness performance of the proposed and benchmark algorithms in scenarios 2 and 3. The fitness values of CA and CA2 consistently exceeded those of the other algorithms. While SA originally exhibited greater fitness than TS, its performance diminished after 30 requests and continued to decline beyond 70 requests, eventually falling below GA. In scenarios with a smaller number of requests, TS initially exhibited lower fitness levels compared to SA. However, SA surpassed TS after processing 30 or more requests. Ultimately, GA outperformed SA after processing 70 requests, despite having lower fitness values in the initial stages.

5.2. Discussions

The results of the comprehensive experiment revealed key insights into the performance of the CA compared to benchmarks across metrics such as NC, NEC, NES, fitness, and execution times in three different scenarios. The findings indicate that the CA and benchmarks performed differently in various scenarios with varying workload requests. Based on the results, the CA consistently maintained QoS solutions while outperforming benchmark methods, particularly in terms of lower computational costs across various scenarios and request counts. Despite the increasing complexity of the service composition problem, the CA achieved rapid execution times, low NC, NEC, and NES values, and high fitness across a range of experimental scenarios. In light of these findings, CA is the recommended algorithm for achieving high-quality results in resource-constrained environments.

As the number of requests increased, the performance advantage of the CA over other algorithms became increasingly evident, highlighting its scalability and flexibility in addressing complex service composition challenges. The algorithm exhibited a linear increase in execution time while consistently maintaining lower values for NC, NEC, and NES, alongside high solution quality. This demonstrates the CA's practicality and reliability for large-scale and real-time applications.

In contrast, GA’s ability to explore the solution space resulted in high NES and execution times. Although GA exhibited a moderate NEC and high NES, it still had trouble achieving optimal fitness values, particularly when the volume of requests increased. A key factor in GA’s reduced performance is premature convergence. GA starts with a randomly generated population, which may be lacking in diversity or high-quality initial solutions. This limitation can make it more difficult for the algorithm to effectively explore the solution space, which can lead to premature convergence to suboptimal solutions. Although the purpose of mutation and crossover processes is to ensure variety and improve solutions, their performance is impacted by the quality and variety of the initial population. As a result, GA’s extensive exploration led to longer execution times, making it less suitable for real-time or large-scale applications.

In our experiments, we found that the TS algorithm offers a well-rounded approach, striking an ideal balance between efficiency and exploration. Its NES values were moderate – generally higher than CA/CA2 but lower than GA – while its execution time was better than GA and comparable to CA/CA2. TS avoided local optima and achieved competitive fitness across a variety of experimental scenarios. However, its linear growth in both execution time and NES implies that while it scales well, it still requires more computational resources than CA and CA2. Furthermore, TS yielded the largest NEC values. Notably, after processing 70 requests, TS sometimes performed better than CA2, demonstrating its ability to preserve solution quality in high-request scenarios. This suggests that TS is a viable option when computational resources are adequate.

The SA algorithm provided a middle ground, outperforming GA in efficiency and achieving comparable fitness due to its moderate NEC, NES, and execution time. Nevertheless, it did not outperform CA/CA2 in all situations.

In summary, the experimental results confirm that CA and CA2 are the most reliable and scalable algorithms, particularly in complex, large-scale environments where both computational efficiency and solution quality are critical. In most scenarios, CA and CA2 achieved the highest fitness and the lowest values for NC, NES, NEC, and execution time. TS, on the other hand, proved to be a suitable choice for situations where high-quality solutions were a priority and computational resources were abundant, as it delivered competitive fitness at the expense of increased computational effort. GA, despite its extensive exploration, underperformed in terms of fitness and had long execution times, making it unsuitable for large-scale cloud service composition. The performance of SA was mediocre, combining efficiency and fitness, but it lagged behind both CA/CA2 and TS.

6. Conclusions

Service composition in multi-cloud environments presents a complex challenge due to its NP-hard nature. This research proposes a chemistry-based approach to address these complexities, utilizing principles from the periodic table and electron motion to simplify the service composition problem. The proposed CA method identifies appropriate service files and clouds, which are crucial for reducing both the number of combined and examined clouds. Additionally, it leverages electron movement patterns to efficiently discover services that meet the required quality, eliminating the need for exhaustive search processes.

The performance of the CA was assessed through comparisons with state-of-the-art service composition algorithms in a controlled experimental setting. Relative to the benchmark algorithms, the proposed method evaluated a smaller number of clouds, services, and combined clouds, while achieving competitive execution times and fitness levels. Extensive experiments across three distinct scenarios demonstrated the CA's robust performance in resource management and service composition. These promising results establish a strong foundation for the algorithm's application across a range of scenarios and diverse fields.

The algorithm's strong performance in static environments lays a solid foundation for its extension to dynamic environments. Its demonstrated capability to optimize resources offers promising opportunities for dynamic and real-time adaptations. Moreover, the algorithm's exceptional performance in multi-cloud computing environments highlights its applicability across diverse domains. This approach is particularly promising for fog computing applications due to its resource optimization and execution efficiency. Furthermore, the algorithm's modular design facilitates integration with complementary techniques, such as adaptive heuristics and reinforcement learning. In multi-cloud environments and related domains, such hybridization could further enhance the algorithm's overall efficiency.

The theoretical contributions of this work extend beyond service composition, establishing a new direction in algorithm design for complex optimization problems. Our innovative SF table structure and quality-based service organization introduce novel concepts that could revolutionize resource allocation and optimization in cloud computing. The algorithm's demonstrated ability to maintain superior performance across varying scales represents a significant advancement in scalable cloud service composition.

Author Contribution: Conceptualization, Mona Aldakheel and Heba Kurdi; Formal analysis, Mona Aldakheel; Funding acquisition, Heba Kurdi; Investigation, Heba Kurdi; Methodology, Mona Aldakheel and Heba Kurdi; Software, Mona Aldakheel; Supervision, Heba Kurdi; Validation, Mona Aldakheel and Heba Kurdi; Writing – original draft, Mona Aldakheel; Writing – review & editing, Mona Aldakheel and Heba Kurdi.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research project was supported by the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2025R204), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. M.A. acknowledge the use of ChatGPT to improve grammar and clarity. The final content has been reviewed and approved by the authors to ensure accuracy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Wu, Z.; Service computing: Concept; method; Press, A., 2014.

- Wiesner, K.; Vaculín, R.; Kollingbaum, M.; Sycara, K. Recovery mechanisms for semantic web services. in Lecture Notes in Computer Science Conference on Distributed Applications and Interoperable Systems IFIP International, 2008, pp. 100–105.

- Sheng, J.; et al. Learning to schedule multi-NUMA virtual machines via reinforcement learning. Pattern Recognit., 2022, 121, 108254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, M.; Zhou, X.; Long, L. Location-aware job scheduling for IoT systems using cloud and fog. Alex. Eng. J., 2025, 110, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, M.; Emadi, S. Services composition in multi-cloud environments using the skyline service algorithm. Int. J. Eng., 2021, 34, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingam, C.; Mohan, P. Addressing semantics standards for cloud portability and interoperability in multi cloud environment. Symmetry, 2021, 13, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Ding, Z. Application-oriented cloud workload prediction: A survey and new perspectives. Tsinghua Sci. Technol., 2024, 30, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ma, H.; Zhang, M. A genetic programming approach to distributed QoS-aware web service composition. in Proc. IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), New York: IEEE, 2014, pp. 1840–1846.

- Ghobaei-Arani, M.; Rahmanian, A.A.; Aslanpour, M.S.; Dashti, S.E. CSA-WSC: Cuckoo search algorithm for web service composition in cloud environments. Soft Comput., 2018, 22, 8353–8378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayyolalam, V.; Kazem, A.A.P. A systematic literature review on QoS-aware service composition and selection in cloud environment. J. Netw. Comput. Appl., 2018, 110, 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatoth, C.; Gangadharan, G.R.; Buyya, R. Computational intelligence based QoS-aware web service composition: A systematic literature review. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput., 2015, 10, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, K.; Kumar, G. Nature inspired techniques and applications in intrusion detection systems: Recent progress and updated perspective. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng., 2021, 28, 2897–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saji, Y.; Riffi, M.E. A comparative study of three nature-inspired algorithms using the Euclidean travelling salesman problem. in Proceedings of the Mediterranean Conference on Information & Communication Technologies 2015, Springer, 2016, pp. 327–335.

- Bejinariu, S.-I.; Rotaru, F.; Luca, R.; Niţă, C.D.; Costin, H. Black hole vs particle swarm optimization. in 10th International Conference on Electronics, Computers and Artificial Intelligence (ECAI), IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–6.

- Yu, Q.; Chen, L.; Li, B. Ant colony optimization applied to web service compositions in cloud computing. Comput. Electr. Eng., 2015, 41, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, H.; Ezzat, F.; Altoaimy, L.; Ahmed, S.H.; Youcef-Toumi, K. MultiCuckoo: Multi-cloud service composition using a cuckoo-inspired algorithm for the Internet of Things applications. IEEE Access, 2018, 6, 56737–56749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, M.H. Bi-objective web service composition problem in multi-cloud environment: A bi-objective time-varying particle swarm optimisation algorithm. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell., 2021, 33, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, H.; Al-Anazi, A.; Campbell, C.; Al Faries, A. A combinatorial optimization algorithm for multiple cloud service composition. Comput. Electr. Eng., 2015, 42, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedhli, A.; Mezni, H. A survey of service placement in cloud environments. J. Grid Comput., 2021, 19, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Hao, Y. An energy-aware multi-target service composition method in a multi-cloud environment. IEEE Access, 2020, 8, 196567–196577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souri, A.; Rahmani, A.M.; Navimipour, N.J.; Rezaei, R. A hybrid formal verification approach for QoS-aware multi-cloud service composition. Clust. Comput, 2020, 23, 2453–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, G.; Barnaghi, P.; Wang, W.; De, S.; Moessner, K. Composition of services in pervasive environments: A divide and conquer approach. in Proc. IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), IEEE, 2013, pp. 000226–000232.

- Shang, J.; Liu, L.; Wu, C. WSCN: Web service composition based on complex networks. in Proc. 2013 International Conference on Service Sciences (ICSS), IEEE, 2013, pp. 208–213.

- Ghobaei-Arani, M.; Souri, A. LP-WSC: a linear programming approach for web service composition in geographically distributed cloud environments. J. Supercomput., 2019, 75, 2603–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidara, I.; Guermouche, N.; Chaari, T.; Jmaiel, M. Time-aware selection approach for service composition based on pruning and improvement techniques. Softw. Qual. J., 2020, 28, 1245–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezni, H.; Sellami, M. Multi-cloud service composition using formal concept analysis. J. Syst. Softw., 2017, 134, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, Z.; Kamandi, A.; Shabankhah, M. An optimal service composition algorithm in multi-cloud environment. in Proc. 5th International Conference on Web Research (ICWR), IEEE, 2019, pp. 141–151.

- Rajakumar, R.; Dhavachelvan, P.; Vengattaraman, T. A survey on nature inspired meta-heuristic algorithms with its domain specifications. in Proc. International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–6.

- Wang, L.; Shen, J. A systematic review of bio-inspired service concretization. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput., 2015, 10, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Ai, L. A hybrid genetic algorithm for the optimal constrained web service selection problem in web service composition. in Proc. IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, IEEE, 2010, pp. 1–8.

- Grati, R.; Boukadi, K.; Ben-Abdallah, H. QoS based resource allocation and service selection in the cloud. in Proc. 11th International Conference on e-Business (ICE-B), IEEE, 2014, pp. 249–256.

- Wang, D.; Yang, Y.; Mi, Z. A genetic-based approach to web service composition in geo-distributed cloud environment. Comput. Electr. Eng., 2015, 43, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatoth, C.; Gangadharan, G.R.; Buyya, R. Optimal fitness aware cloud service composition using an adaptive genotypes evolution based genetic algorithm. Future Gener. Comput. Syst., 2019, 94, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghiram, S.; Ma, H.; Chen, G. Multi-objective distributed Web service composition-A link-dominance driven evolutionary approach. FUTURE Gener. Comput. Syst.- Int. J. ESCIENCE, 2023, 143, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Du, Y.; Chen, F. A hybrid strategy improved SPEA2 algorithm for multi-objective web service composition. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Du, Y. An Adaptive Mutation Strategy Improved SPEA2 Algorithm for Multi-objective Web Service Composition. in Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Symposium on Robotics, Artificial Intelligence and Information Engineering, 2024, pp. 15–20.

- Garcia, N.P.; Duran, F.; Berrocal, K.M.; Pimentel, E. Location-aware scalable service composition. Softw.-Pract. Exp., 2023, 53, 2408–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghiram, S.; Ma, H.; Chen, G. Cluster-guided genetic algorithm for distributed data-intensive web service composition. in Proc. IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–7.

- Zhang, W.; Guo, H.; Zeng, Z.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Y. Transportation cloud service composition based on fuzzy programming and genetic algorithm. Transp. Res. Rec., 2018, 2672, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.A.; Serajzadeh, H. Effective web service composition using particle swarm optimization algorithm. in Proc. 6th International Symposium on Telecommunications (IST), IEEE, 2012, pp. 1190–1194.

- Gao, H.; Zhang, K.; Yang, J.; Wu, F.; Liu, H. Applying improved particle swarm optimization for dynamic service composition focusing on quality of service evaluations under hybrid networks. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw., 2018, 14, 1550147718761583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, S.M.; Sangaiah, A.K. Integrated QoUE and QoS approach for optimal service composition selection in internet of services (IoS). Multimed. Tools Appl., 2017, 76, 22889–22916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, F. An effective multi-agent ant colony optimization algorithm for QoS-aware cloud service composition. IEEE Access, 2021, 9, 17196–17207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayed, H.; Dahan, F.; Alfakih, T.; Mathkour, H.; Arafah, M. Enhancement of ant colony optimization for QoS-aware web service selection. IEEE Access, 2019, 7, 97041–97051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sheng, Q.Z.; Wang, Z.; Yao, L.; et al. Novel artificial bee colony algorithms for QoS-aware service selection. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput., 2016, 12, 247–261. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, L.; Wang, Z. Service composition instantiation based on cross-modified artificial bee colony algorithm. China Commun., 2016, 13, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, G.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhao, S. An optimization algorithm for service composition based on an improved FOA. Tinshhua Sci Technol, 2015, 20, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghir, F.; Khababa, A. A hybrid approach using genetic and fruit fly optimization algorithms for QoS-aware cloud service composition. J. Intell. Manuf., 2018, 29, 1773–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, B.; Chen, W. Research on intelligence optimization of web service composition for QoS. in Proc. Communications in Computer and Information Science International Conference on Information Computing and Applications, Springer, 2012, pp. 227–235.

- Wang, H.; Yang, D.; Yu, Q.; Tao, Y. Integrating modified cuckoo algorithm and creditability evaluation for QoS-aware service composition. Knowl. Based Syst., 2018, 140, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.B.; Reddy, P.C.H. A hybrid meta-heuristic approach for QoS-aware cloud service composition. Int. J. Web Serv. Res. IJWSR, 2018, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Gao, H.; Chen, Y. Web service selection algorithm based on particle swarm optimization. in Eighth IEEE International Conference on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, IEEE, 2009, pp. 467–472.

- Clerc, M.; Kennedy, J. The particle swarm-explosion, stability, and convergence in a multidimensional complex space. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput., 2002, 6, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazif, H.; Nassr, M.; Al-Khafaji, H.M.R.; Navimipour, N.J.; Unal, M. A cloud service composition method using a fuzzy-based particle swarm optimization algorithm. Multimed. Tools Appl., 2024, 83, 56275–56302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabalvandani, M.A.N.; Shirvani, M.H.; Motameni, H. Reliability-aware web service composition with cost minimization perspective: a multi-objective particle swarm optimization model in multi-cloud scenarios. Soft Comput., 2024, 28, 5173–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Shen, J.; Krishna, A. Ant inspired scalable peer selection in ontology-based service composition. in Proc. World Conference on Services-II, IEEE, 2009, pp. 95–102.

- Dahan, F.; El Hindi, K.; Ghoneim, A. An adapted ant-inspired algorithm for enhancing web service composition. Int. J. Semantic Web Inf. Syst. IJSWIS, 2017, 13, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Liu, F.; Wang, J.; Song, Y. Cuckoo search-designated fractal interpolation functions with winner combination for estimating missing values in time series. Appl. Math. Model., 2016, 40, 9692–9718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.-Q.; Fang, X.-W.; Jiang, C.-J. Research on web service selection based on cooperative evolution. Expert Syst. Appl., 2011, 38, 9736–9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wei, Y.; Tang, K.; Qin, A.K.; Yao, X. QoS-aware long-term based service composition in cloud computing. in Proc. IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), IEEE, 2015, pp. 3362–3369.

- Deng, S.; et al. Toward risk reduction for mobile service composition. IEEE Trans. Cybern., 2016, 46, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomski, A.; Skaruz, J.; Switalski, P.; Penczek, W. Concrete planning in PlanICS framework by combining SMT with GEO and simulated annealing. Fundam. Informaticae, 2016, 147, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banâtre, J.-P.; Priol, T.; Radenac, Y. Service orchestration using the chemical metaphor. in Proc. IFIP International Workshop on Software Technolgies for Embedded and Ubiquitous Systems, Springer, 2008, pp. 79–89.

- Banâtre, J.-P.; Priol, T.; Radenac, Y. Chemical programming of future service-oriented architectures. J Softw, 2009, 4, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, C.; Giordano, M.; Németh, Z.; Tonellotto, N. Using chemical reactions to model service composition. in Proceedings of the second international workshop on Self-organizing architectures, 2010, pp. 43–50.

- Viroli, M.; Casadei, M. Chemical-inspired self-composition of competing services. in in Proc. Proceedings of the 2010 ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, 2010, pp. 2029–2036.

- Fernández, H.; Tedeschi, C.; Priol, T. A chemistry-inspired workflow management system for decentralizing workflow execution. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput., 2013, 9, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pazat, J.-L. A chemistry-inspired middleware for self-adaptive service orchestration and choreography. in Proc. 2013 13th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud, and Grid Computing, IEEE, 2013, pp. 426–433.

- De Angelis, F.L.; Fernandez-Marquez, J.L.; Di Marzo Serugendo, G. Self-composition of services in pervasive systems: A chemical-inspired approach. in Agent and Multi-Agent Systems: Technologies and Applications: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference KES-AMSTA 2014 Chania, Greece, June 2014, Springer, 2014, pp. 37–46.

- Ko, J.M.; Kim, C.O.; Kwon, I.-H. Quality-of-service oriented web service composition algorithm and planning architecture. J. Syst. Softw., 2008, 81, 2079–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spezzano, G. Using service clustering and self-adaptive MOPSO-CD for QoS-aware cloud service selection. Procedia Comput. Sci., 2016, 83, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Kumar, R.R.; Kumari, B. A novel approach for cloud service composition ensuring global QoS constraints optimization. in Proc. International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), IEEE, 2018, pp. 1695–1701.

- Sefati, S.S.; Halunga, S. A hybrid service selection and composition for cloud computing using the adaptive penalty function in genetic and artificial bee colony algorithm. SENSORS 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, F.; Alwabel, A. Artificial bee colony with cuckoo search for solving service composition. IN℡LIGENT Autom. SOFT Comput., 2023, 35, 3385–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, L.; Wenlin, L.; Xin, S.; Xibin, X. An improved ACO based service composition algorithm in multi-cloud networks. J. Cloud Comput., 2024, 13, 17–Jan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaudhaya, J.; Jayaraj, R.; Ramash, K.K. A new integrated approach for cloud service composition and sharing using a hybrid algorithm. Math. Probl. Eng. 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Arasteh, B.; Aghaei, B.; Bouyer, A.; Arasteh, K. A quality-of-service aware composition-method for cloud service using discretized ant lion optimization algorithm. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.B.; Isazadeh, A.; Rahmani, A.M. QoS-aware service composition in cloud computing using data mining techniques and genetic algorithm. J. Supercomput., 2017, 73, 1387–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taramasco, C.; Crawford, B.; Soto, R.; Cortés-Toro, E.M.; Olivares, R. A new metaheuristic based on vapor-liquid equilibrium for solving a new patient bed assignment problem. Expert Syst. Appl., 2020, 158, 113506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatas, B. ACROA: Artificial chemical reaction optimization algorithm for global optimization. Expert Syst. Appl., 2011, 38, 13170–13180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, A.Y.; Li, V.O. Chemical reaction optimization: A tutorial. Memetic Comput., 2012, 4, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, D.E. The periodic table of elements, an early example of ‘big data,’” TC Comput Sci Eng, pp. 4–7, 2016.

- Brown, T.L.; Chemistry: The central science; Education, P., 2012.

- Al-Ossmi, L.H.M.; Al-Asadi, A.K. A simplified method for estimating atomic number and neutrons numbers of elements based on period and group numbers in the periodic table. Orient. J. Chem., 2019, 35, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commons contributors, W. Simple periodic table with four-figure atomic weights.” [Online]. Available: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Simple_periodic_table_with_four-figure_atomic_weights.svg.

- Canfora, G.; Di Penta, M.; Esposito, R.; Villani, M.L. An approach for QoS-aware service composition based on genetic algorithms. in Proceedings of the 7th annual conference on Genetic and evolutionary computation, 2005, pp. 1069–1075.

Figure 1.

Periodic table [

85].

Figure 1.

Periodic table [

85].

Figure 2.

Bohr model [

63].

Figure 2.

Bohr model [

63].

Figure 3.

System architecture.

Figure 3.

System architecture.

Figure 5.

Main control algorithm.

Figure 5.

Main control algorithm.

Figure 6.

Request processing flow.

Figure 6.

Request processing flow.

Figure 9.

Search process.

Figure 9.

Search process.

Figure 11.

Number of combined clouds vs. number of requests: (a) scenario 1, (b) scenario 2, (c) scenario 3.

Figure 11.

Number of combined clouds vs. number of requests: (a) scenario 1, (b) scenario 2, (c) scenario 3.

Figure 12.

Number of examined clouds vs. number of requests: (a) scenario 1, (b) scenario 2, (c) scenario 3.

Figure 12.

Number of examined clouds vs. number of requests: (a) scenario 1, (b) scenario 2, (c) scenario 3.

Figure 13.

Number of examined services vs. number of requests: (a) scenario 1, (b) scenario 2, (c) scenario 3.

Figure 13.

Number of examined services vs. number of requests: (a) scenario 1, (b) scenario 2, (c) scenario 3.

Figure 14.

Execution Time vs. number of requests: (a) scenario 1, (b) scenario 2, (c) scenario 3.

Figure 14.

Execution Time vs. number of requests: (a) scenario 1, (b) scenario 2, (c) scenario 3.

Figure 15.

Fitness vs. number of requests: (a) scenario 1, (b) scenario 2, (c) scenario 3.

Figure 15.

Fitness vs. number of requests: (a) scenario 1, (b) scenario 2, (c) scenario 3.

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Service Composition Methods.

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Service Composition Methods.

| Reference |

Minimum NC |

Minimum NES |

QoS support |

| [18] |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

| [15,16,26,27] |

✓ |

✗ |