1. Introduction

After the 1980s, mainly due to economic stagnation, inflation, and changes in demographic rates, pension systems became one of the largest public expenditures and accumulated deficits in many countries (Grech, 2018). Given population growth, the importance of Pension Funds has been increasing, since public revenues are less able to finance retirement promises (OECD, 2016). The pension system in many countries is undergoing a process of migration: from public to private (Orenstein, 2013; Naczyk and Domonkos, 2016).

Worldwide, pension funds manage nearly 60% of the wealth held by the one hundred largest asset owners (Muir, 2022). Brazil, which has a very robust supplementary pension system, representing 11.9% of Brazil's Gross Domestic Product (GDP), follows the same line (Abrapp, 2023). This leads to the possibility of growth in pension funds, whether due to the number of participants or the creation of new organizational units. From another perspective and considering the long-term nature of these entities, they highlight the need to emphasize fiduciary duty and the sustainability of investments. Equity holders have been demanding investments from pension funds that are responsible and sustainable. Investors have pressed entities for improvements in the adoption and disclosure of ESG (environmental, social, and governance) practices (Muir, 2022).

This position stems from the understanding that sustainable investment considers the interests of current and future participants, in addition to reducing systemic risk (environmental, social, climate effects, etc.) (Muir, 2022; Mitchell, Hammond, Maurer, 2023). It is precisely in this sense that the present study is established: in the consideration of the interests of the participants and the assumption of the existing risk given by the recognition of the asymmetry of information between the different agents. This refers to the relevance of studying financial sustainability indicators that mitigate the asymmetry of information between managers and participants and, therefore, reduce the possibility of conflicts of interest arising in Pension Funds.

The extent of asymmetry is affected by the actions of individuals and its recognition helps in understanding economic and social phenomena that affect organizations (Stiglitz, 2000). Therefore, the interest in providing information on the part of organizations must be like the interest of their stakeholders, enabling them to value the actions of their respective managers. In other words, the evidenced information that expresses the stakeholders' interests will enable the legitimacy of the managers' decisions and the sustainability of investments. In this sense, the disclosure of information must express the interests of the stakeholders, enabling less asymmetric contractual communication.

Understanding the information asymmetry of pension funds involves understanding who their priority stakeholders are. In these organizations, there are at least three categories: the sponsor, the beneficiaries (retired), and the active participants (Drew; Stanford, 2003; Clark, 2004; Rozanov, 2015), hereinafter called primary stakeholders. By contrast, there is the governing body (managers), called “agents”. And, considering the diversity of audiences, which are not directly involved with the management and, therefore, do not have access to the respective information, the informational asymmetry of this contractual relationship is configured. Contracts are not complete because there are imperfections in knowledge and information asymmetry (Stiglitz, 2000), given the gaps of legal, which offer limitations regarding the mandatory transparency of the decisions of the respective managers.

To reduce information asymmetry, disclosure is essential (Verrecchia, 1990). This would be related to the quality and level of disclosure, which depends on the information disclosed, usually analyzed through indicators representative of this information. In general, studies on disclosure do not analyze the perspective of priority stakeholders (Seibert; Macagnan, 2017). Thus, considering that economic sustainability is the base of the pyramid of responsibilities of any organization (Pink et al, 2006; Carroll, 2016; Regert et al, 2018), and just as it also represents the economic-financial sustainability of participants and retirees of pension funds, in the post-labor period, it is understood that is a factor that requires greater attention from stakeholders. Thus, this study aims to build a list of financial sustainability indicators, demanded by priority stakeholders of pension funds, namely: participants and retirees. This list will be able to measure a financial sustainability disclosure index of pension funds.

In addition to the perspective of priority stakeholders, the fact that there is no standard regarding sustainability indicators and the distinct characteristics of these organizations (such as the long-term nature and the fact that they do not trade shares on the stock exchange, according to Caamaño, 2007; Mitchell; Piggott; Kumru, 2008; Kowalewski, 2012 makes the most studies on disclosure do not explain the behavior of managers, justifying the present study.

For the construction of the list of indicators, the methodology considered some steps. The first list of indicators was originated from the individual and detailed examination of the Annual Information Reports (AIR) published by 215 Brazilian pension funds in 2016, referring to the base date 2015, representing 73% of the active pension funds that were part of the National Superintendency of Complementary Pension (PREVIC). Brazil has more than 7 million priority stakeholders (active participants, dependents, and beneficiaries) and occupies the 11th position in total assets in pension plans, in USD million, between 2001 and 2022. (ABRAPP, 2023; OECD, 2023). Understanding this reality can be a parameter to assess the levels of financial sustainability disclosure in other countries around the world.

Afterward, the specific legislation on pension fund disclosure was examined, identifying mandatory information, which made it possible to recognize which would be mandatory and voluntary information. Next, the indicators were evaluated and validated by specialists. In the 4th stage, the indicators were evaluated and validated with the priority stakeholders of the pension funds, participants, and retirees. Afterward, the list of indicators was evaluated using Principal Component Analysis. All these stages allowed the triangulation between information, giving rise, then, to the final list of indicators composed of economic-financial information from pension funds demanded by participants and retirees.

Nonetheless, the final list created in this research, comprising 48 sustainability indicators, allows priority stakeholders to monitor the management of resources held by pension funds, configuring itself as a control mechanism for the performance of managers. This enables regulatory bodies to adjust the rules on information disclosure to include those required by stakeholders and by good governance practices. It also allows pension funds to identify the indicators demanded by stakeholders and the consequent disclosure, albeit voluntarily. Such actions would reduce the asymmetry of information, mitigating the problem of moral hazard, which is characterized by the possibility of managers making decisions for their benefit, going against the interests of the stakeholders of the respective pension funds. In other words, the adoption of the list of indicators created would promote greater trust and legitimacy for pension fund managers.

2. Reference

2.1. Asymmetry of Information and Disclosure of Pension Funds

Pension funds are entities with their characteristics, with contractual relationships between managers, sponsors, retirees, and participants (Clark, 1998; Blake; Lehmann; Timmermann, 1999; Catalan, 2004; Hebb, 2006; Kowalewski, 2012; Rozanov, 2015; Tan; Cam, 2015). On the other hand, although they are not corporations, they have pulverized ownership (Catalan, 2004; Kowalewski, 2012). The trend is the greater the number of participants, the greater the equity. The dispersion of control can be an obstacle to ensuring benefits to participants (Caamaño, 2007) and can lead to the concentration of economic power, to the extent that these organizations become large institutional investors (Catalan, 2004; Mitchell; Piggott; Kumru, 2008; Eaton; Nofsinger; Varma, 2014; Andonov; Eichholtz; Kok, 2015; Rozanov, 2015). Another aspect, the dispersion of ownership promotes the separation between ownership and management, even if there is representation of the retirees and participants in the councils of these organizations (Catalan, 2004; Hebb, 2006; Kowalewski, 2012; Rozanov, 2015; Tan; Cam, 2015).

The separation between ownership and management enables the emergence of information asymmetry. A factor that generates inefficiencies, as the agent's behavior may not be fully monitored (Arrow, 1962; 1963; Akerlof, 1970; Jensen; Meckling, 1976; Stadler; Castrillo, 1994; Stiglitz, 2000; Arrow, 2012), generating uncertainties regarding the allocation of resources. On the other hand, to ensure that there are no economic consequences, there must be trust between the manager and the other stakeholders. This trust would be confirmed through the available resources and disclosed information by management. Economic-financial information must be provided on time (OCDE, 2003), as trust in the organization needs to be maintained (Clark, 1998; Vittas, 2002; Mitchell; Piggott; Kumru, 2008; Kanagaretnam et al., 2010; Bidabad; Amirostovar; Sherafati, 2017). This is because disclosure facilitates the monitoring of managers' actions (Lang Et Al., 2000; Leuz; Verrecchia, 2000; Dye, 2001; Kanagaretnam; Lobo; Whalen, 2007; Clark; Monk, 2011).

The disclosure of information could be mandatory, imposed by law, or voluntary, of the organizations own accord. The degree to which organizations comply with legal and regulatory requirements depends on the rigor of the government, professionals, and the performance of regulatory bodies (Marston; Shrives, 1991; Zaini et al.; 2017; Quagli; Lagazio; Ramassa, 2021), as well as the level of governance of the organizations themselves. Voluntary disclosure depends on the manager's discretion and interest in reducing information asymmetry between the organization and its stakeholders (Verrecchia, 1990). Stakeholders are any identifiable group or individual that may affect or be affected by the achievement of organizational objectives (Freeman; Reed, 1983; Freeman, 1984; Freeman; et al., 2010). However, it is up to the organization to identify priority stakeholders to meet their interests first (Mitchel; Agle; Wood, 1997; Clement, 2005; Harrison; Rouse; Viliers, 2012). The main stakeholders of pension funds are participants (Individuals who adhere to pension benefit plans), retirees (participants or its beneficiary receiving continued benefits, provided for in the benefit plan), beneficiaries (the person indicated by the participant to receive the benefit of continued provision); and sponsor (company or group of companies, the Union, the States, the Federal District, and the Municipalities, their autarchies, foundations, mixed-capital companies, and other public entities that establish, for their employees, a pension benefit plan, through intermediary of a closed entity) (Brasil 2001; 2006a).

Disclosure is an abstract concept that cannot be measured directly, as it does not have characteristics by which its intensity or quality can be determined (García Meca; Matínez Conesa, 2004; Macagnan, 2009; Seibert, 2017). Therefore, measuring it is a complex task. In this sense, most of the research carried out uses disclosure indices (García Meca; Martínez Conesa, 2004; Urquiza; Navarro; Trombetta, 2009) formed by sets of indicators that represent the information that is to be analyzed in terms of disclosure (Seibert et al., 2019). The first studies identified that used indicators to determine the level of disclosure date back to the 1970s, such as: Singhvi and Desai (1971); Choi (1973); Buzby (1975). More recently, there are: Cesar (2015); Forte et al. (2015); Herrera-Rodriguez; Macagnan, (2015); Afonso (2016); Searcy; Dixon; Neumann (2016); Almeida; Callado, (2017); Seibert (2017); Seibert; Macagnan (2019) and Seibert; Macagnan; Dixon (2021) made use of representative information indicators.

2.2. Sustainability Indicators in Pension Funds

An indicator is an informative representation, with qualitative, quantitative, or mixed characteristics, of a phenomenon, referring to the properties of what they represent (São Jose; Figueiredo, 2011). Indicators are often referred to as parameters, measures, measurement points or variables (Giannetti; Almeida, 2006; Heink; Kowarik, 2010), acting as a representative of reality (Minayo, 2009). Indicators bring with them a certain level of subjectivity (Minayo, 2009; São Jose; Figueiredo, 2011). To reduce such subjectivity, its construction process must be guided by some properties: the relevance of the indicator implies recognizing the descriptive capacity of what is being represented; the validity of content representation means that the indicator needs to represent the concept it intends to evaluate; reliability of the measure is linked to the robustness of the information, which legitimizes the indicator; the operational feasibility for obtaining the indicators is related to the availability of access to informational evidence; in addition, there must be methodological transparencies in the process of constructing indicators, periodic updating and the possibility of historical comparability (Jannuzzi, 2005; Macagnan, 2009; Liu et al., 2018).

Indicators must reflect the reality and expectations of benefit plans promptly (OECD, 2003). In pension funds, Investment practices can support sustainability efforts or undermine them. As one of the world’s largest capital pools, pension funds have a particularly important role to play in sustainable investing practices (Muir, 2022). Pensions require pension systems to be funded sustainably compared to companies subject to rapid aging. Pension adequacy and sustainability issues are thus inextricably linked (Ionescu, 2013).

Sustainable investing increases focus on stakeholder interests and improves data and analytics that help capture the outcomes (Mitchell, Hammond, Maurer, 2023). As, by definition, these entities exist to service long-term obligations to beneficiaries, trustees must observe issues of responsibility and sustainability in society and finance (Muir, 2022). Pension plans’ long horizons render them particularly vulnerable to many long-lived ESG risks. Potential consequences of being underfunded, especially in the case of defined-benefit pensions, leave the funds particularly vulnerable to ESG-related downside risks, like reputational risk, human capital-related risks, litigation risk, regulatory risk, and corruption risk (Geczy; Guerard Jr., 2023). Furthermore, attention by capital owners to sustainable investment practices should have positive spillover effects on the social responsibility of the organizations. Stakeholders can increasingly pressure entities to adopt and disseminate best practices in terms of sustainable investments, and experts have offered a variety of arguments to support a fiduciary obligation to consider ESG factors even if that consideration requires some compromise in financial returns (Muir, 2022).

One of these arguments is decreasing systemic risks and taking a longer-term view of investment interests, their approach would benefit society by decreasing the negative externalities created by plan investments. There is a potential direct effect on risk-adjusted investment returns and increased availability of responsible capital. Combining information from both expected return models and ESG criteria could enhance equity portfolio construction efforts. (Muir, 2022; Geczy; Guerard Jr., 2023). From this perspective, this study focuses on economic-financial sustainability indicators. For Carroll (2016) economic sustainability is the base of the pyramid of responsibilities of any organization. Without meeting this responsibility, the organization is unable to meet the others. Therefore, economic-financial information demonstrates the efficiency in resource management, as well as the value and risk of organizational activities (Bushman; Smith, 2003; Verdi, 2006; Gomariz; Ballesta, 2014). In addition, this information enables stakeholders to identify investment opportunities and discipline managers in the use of resources according to organizational objectives, avoiding conflicts of interest and reducing information asymmetry (Akerlof, 1970; Jensen; Meckling, 1976; Stiglitz, 2000; Bushman; Smith, 2001; 2003; Seibert; Macagnan, 2017).

It emerges that the reviewed studies used one or more of the four types of methodologies and none of them consider the perspective of stakeholders. In the first, the indicators have their origin in the literature review. This methodology is used by most of the reviewed studies (Cesar, 2015; Forte et al, 2015; Herrera-Rodríguez; Macagnan, 2015; Afonso, 2016; Searcy; Dixon; Neumann, 2016; Almeida; Callado, 2017; Seibert, 2017; Seibert; Macagnan, 2019; Macagnan; Seibert, 2021). In the second methodology, the indicators are constructed from the analysis of the annual information reports (AIRs) or websites of organizations (Attig; Cleary, 2015; Cooper; Slack, 2015; Khlif, Guidara; Souissi, 2015; Pesci, Costa; Soobaroyen, 2015; Pivac, Vuko; Cular, 2017; Gnanaweera; Kunori, 2018). The third methodology for constructing indicators consists of following the guidelines and recommendations of regulatory organizations (Burgwal; Vieira, 2014; Liesen et al., 2015; Welbeck et al., 2017), emerging the voice of the formal institutional matrix of society. Finally, the fourth methodology is established by indicators suggested by experts on the theme of information studied (Bachmann; Carneiro; Espejo, 2013). This review allows us to identify the gap in the construction of indicators, from the perspective of stakeholders. The next topic presents the methodological procedures used in the research.

3. Methodology

To determine the indicators, criteria were defined (respecting the following steps: examination of the Annual Information Reports (AIRs) published by pension funds; examination of the specific legislation on disclosure of pension funds; evaluation and validation of the indicators with specialists; evaluation and validation of the indicators with participants and retirees, priority stakeholders of pension funds, and Principal Component Analysis.

1st stage: individual and detailed examination of the AIRs, a list was obtained with the names and addresses of the electronic pages of Brazilian pension funds. In the list obtained from the National Superintendence of Complementary Pension (PREVIC), there were 317 pension funds. Of these, some had information restricted to participants, did not publish the consolidated AIRs, were in liquidation, and did not have Internet pages, therefore, they were excluded. Thus, the final sample consisted of 215 pension funds in 2016, referring to the base date 2015 (representing 73% of the active pension funds), two of which the AIRs were read.

2nd stage: examination of specific legislation on pension fund disclosure, a distinction was made between what is mandatory and recommended disclosure. Mandatory disclosure occurs by force of law or regulations issued by the Federal Government and regulatory bodies. The recommended disclosure comes from manuals published by the supervisory body: the National Superintendence of Complementary Pension (PREVIC) or other related organizations.

3rd stage: for the evaluation and validation of the indicators with specialists, a questionnaire was developed based on the list of indicators created in the previous stages. Respondents chose an alternative between 1 and 5, with 1 being strongly disagree and 5 being strongly agree, for the list of indicators presented. This process was carried out in two phases: the first consisted of sending and answering the questionnaire to 7 professors who were researchers on topics related to pension funds. Subsequently, the validation took place with accountants and auditors from the largest pension funds in Brazil, using the asset size criterion. Thus, questionnaires were sent to 40 auditors and accountants from these organizations, resulting in 5 responses. Totaling 12 questionnaires answered by experts.

4th stage: for the evaluation and validation of the indicators with the primary stakeholders (retirees and participants), we had the help of the National Association of Pension Fund Participants (ANAPAR). Response options are "sufficient information"; "insufficient information"; "unnecessary information"; and "does not provide the information". It is noteworthy that, in the questionnaires sent to specialists, participants and retirees, there was the possibility of including observations for each indication. There was also the option of including information considered relevant that was not included in the list presented for evaluation and validation. The questionnaire was built on the Google Forms platform. Correspondence with an explanation of the survey and a link to the response was forwarded by ANAPAR to its members – approximately 9,000 retirees and participants. In all, 168 valid responses were obtained from participants and retirees.

5th stage: at least, Principal Component Analysis was used, a multivariate statistical technique that consists of transforming a set of original variables into another set of variables of the same dimension called principal components. This technique allows you to select indicators that explain the greatest amount of variance from the smallest possible number of variables (Mendonça et al., 2016). The use of the principal component’s technique helps to reduce the degree of subjectivity in defining the indicators that make up the level of disclosure of Brazilian Pension Funds. The technique also allows a simultaneous analysis of the behavior of several indicators, making it possible to visualize the effect of one on the other (Varella, 2008; Silva, 2009).

To finalize the list of 48 indicators, an analysis of the indicators constructed from the AIRs was carried out, aiming to verify whether the respective pension funds evidenced economic-financial information demanded by the primary stakeholders, according to this research.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. 1st and 2nd Stage – Initial List of Economic and Financial Indicators

One of the presuppositions of pension funds is the duty of trust, that is, the responsibility of directors to the resources of participants and retirees established by legislation (CGPC Resolution nº. 13 of 2004, CGPC Resolution nº. 18 of 2006, CNPC Resolution nº. 15 of 2014). The disclosure of economic-financial information is precisely this way to ensure trust and reduce information asymmetry.

Along these lines, Rose (2015) points out that one of the important indicators is the disclosure of investment policies. Anantharaman (2017), in contrast, comments on the increasing complexity of estimates and, therefore, the role of specialist auditors and actuaries through their reports and opinions. In turn, Paula and Lima (2014) emphasize the importance of financial statements when performing a comparative analysis between the elements that make up the structures of the Statement of Changes in Net Assets (SOCNA), of the Statement of Net Assets (SONA) and the Statement of Actuarial Obligations of the Benefit Plan (SOAO), defined by the Brazilian standard, and the elements established by IAS 26 - Accounting and Reporting by Retirement Benefit Plans, which applies to the international financial statements of benefit plans. The Resolution of CGPC n. 23 (Brasil, 2006b) and CNPC n. 8 (Brasil, 2011), provide for the basic procedures to be observed in the disclosure of information and define the guidelines for the preparation and dissemination of AIRs.

The Previc Best Accounting Practices for Closed Complementary Pension Entities Guide, as voluntary disclosure, is intended to provide guidelines for the process of preparing the financial statements and explanatory notes of these organizations. It emphasizes that it is recommended that pension funds formalize an information disclosure policy as a practice of transparency. Therefore, the main communication documents related to accounting are the financial statements, the explanatory notes, and the annual report, the latter presenting greater flexibility in the topics addressed and, in the analyses, allowing the exposure of more detailed information (PREVIC, 2014). Voluntary disclosure of pension funds, in contrast, was classified as such as it is identified by the spontaneous disclosure of pension funds. From the initial list, no indicator was added, as all those identified in this phase were already contemplated. Only the indicator “Statement of Actuarial Obligations of the Benefits Plan (SOAO) was excluded, as it was replaced by the Statement of Technical Provisions (SOTP), according to CNPC Resolution n. 12 (Brasil, 2013), which was already on the list. Thus, the list consisted of 54 indicators: 15 mandatories, 17 recommended, and 22 voluntaries.

4.2. 3rd Stage – Evaluation and Validation of Indicators with Specialists

This stage resulted in 12 completed questionnaires, 7 from research professors and 5 from accountants and auditors. From the answers obtained, a qualitative analysis of the answers was carried out. From the list of 54 indicators contained in the questionnaire, 36 obtained responses between “agree” and “strongly agree” from more than 70% of the evaluators. In addition, specialists made comments such as: “The listing is quite complete”. If the information "is prepared, and reviewed appropriately by the administration before its release, to ensure consistency, it will be a great source of information and analysis."

Some indicators presented intermediate evaluations, as 50% of the evaluators deserved concepts between "agree" and "strongly agree" and for another 50%, the evaluations were between "strongly disagree" and "do not agree nor disagree". Noteworthy are the indicators "organization chart" of the pension fund, "Number of attendances" carried out by the funds, to their members, "Social Balance Sheet", "Terms of Office of the Executive Board", and "Minutes of the Ordinary Meetings of the Executive Board, Deliberative Council, and Fiscal Council”.

On the other hand, some indicators were evaluated as not relevant for the disclosure of economic-financial information of pension funds, as they computed more than 60% of opinions between “strongly disagree” and “do not agree, nor disagree”. Noteworthy are the indicators “Specific Report on Internal Controls”, “Internal Audit opinion”, “Certification of Directors”, “Mini Curriculum of the Executive Board”, “Financial Education”, “Number of Human Resources”, “Glossary” and “List of Service Contracts”. In the words of one of the evaluators, some of the information “is for internal use and it makes little sense to have disclosure”. Another expert mentions that “we must be careful when disclosing this type of information to lay people”, referring to the reports on internal controls and internal auditing. For this stage, no new indicators were excluded or inserted, the list remaining with 54 indicators. As for those indicated as “totally disagree”, we decided to keep them on the list until they were evaluated by participants and retirees.

4.3. 4th Stage – Evaluation and Validation of Indicators by Retirees and Participants

For the questionnaires sent, 168 valid responses were obtained. Regarding the profile of respondents, 61% fall into the retiree category (retirees who receive the benefit), 36% are active participants, 2% are beneficiaries and another respondent identified himself as an active participant and a member of the supervisory board. Regarding the type of plan they have, 67% responded defined benefit (DB), 17% defined contribution (DC) and 19% variable contribution (VC). Seven answers (equivalent to 4%) chose the option “others”. Of these, six mentioned benefits already settled and one mentioned that they had DC and DB plans simultaneously. For each indicator specifically, respondents received four response options: “the fund does not provide this information”, “this information is unnecessary”, “this information is sufficient”, this information is insufficient”.

Of the indicators analyzed by respondents, 60% of the responses were "the fund does not provide this information" and "this information is insufficient" added together. The indicator "information on Remuneration of Directors" received some additional comments, such as "these values were vaguely revealed", "the fund simply does not disclose such information", or even, "there is the information, but we do not know if it is compatible with the market”. The need to disclose “minutes of the ordinary meetings of the Executive Board, Deliberative and Fiscal Council” was cited by several participants as: “in our fund, I see the failure to publish the minutes on the Institute's website as another major problem”. On the other hand, another respondent ponders the disclosure by mentioning that “there is confidential information that involves the market, you have to be careful”. For the indicator “Main administrative decisions of the fund” it was mentioned that “the information given is not reliable”. Another participant would like the fund's decisions to be taken with the approval of its participants and that they have full transparency. Likewise, another participant mentions that he would like the disclosure “about the fairness of the decisions taken by the managers”.

The alternative: “this information is unnecessary”, presented a very low index (between 1% and 2%) for all indicators presented. The indicators “number of assistances” carried out by the fund and “information that help the participant's financial education” showed slightly higher percentages in this regard, with 6 (4%) and 5 (3%) responses, respectively.

By contrast, the indicators that obtained the highest number of answers to the question “this information is sufficient” are: “composition of the councils and executive board” (68%); “number of participants” (68%); “information if the director is a sponsor or participant representative” (66%); “Contact Information/Communication Channels” (66%); “terms of office of the executive board and terms of office of the deliberative and fiscal council” (58%); “information on elections/nomination/selection - Executive Board” (57%) and “Total Equity” (55%). Thus, in addition to the indicators pointed out in the previous steps, the qualitative analysis of the responses of the retirees and participants determined the inclusion of the indicators: Taxation System of plans, Remuneration of Directors, and Financial Health of the Sponsor.

These indicators were included for presenting high indexes in the answers “does not provide” or “insufficient information”. In addition, regarding the plans' taxation system, participants commented on the complexity of the matter and the need for further clarification on the taxes levied on their respective plans. Regarding the remuneration of directors, it was mentioned that the information is not disclosed or disclosed insufficiently. The information about the financial health of the sponsor becomes relevant mainly for the participants of the DB plans, as they need to know if, in an eventual situation of losses in the DB plans, the sponsoring organizations will be able to make contributions to equalize the value of the intended benefits.

Also, some indicators were excluded considering that in the qualitative analysis of the responses of specialists and participants (stages 3 and 4), no relevant indicators were shown. These indicators were also not included in the mandatory lists or those recommended by the PREVIC guides (Step 2). They are Number of assistances; Social Balance sheet; Internal Audit Opinion; and Financial Education. At the end of this stage, the relationship is composed of 53 indicators.

4.4. 5th Stage – Principal Component Analysis

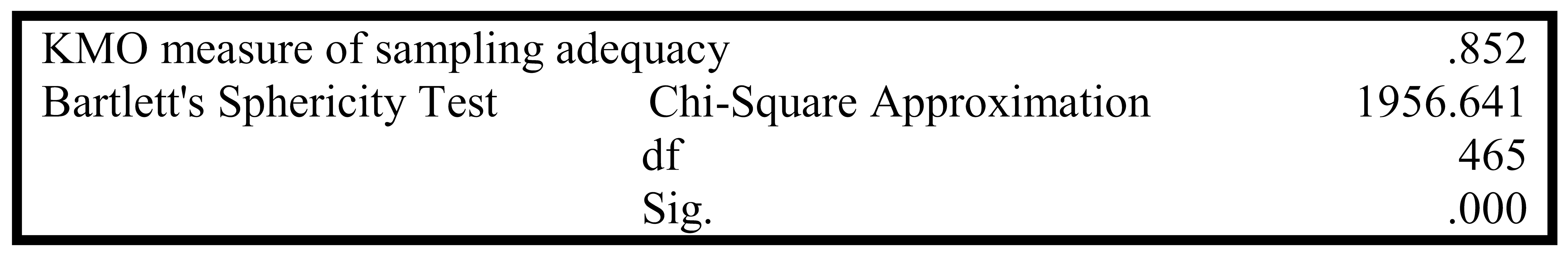

To identify the suitability of using Principal Component Analysis for the selection of indicators, the KMO tests and Bartlett's Sphericity Test were carried out. If the correlation between the variables tested by the KMO is small, that is, the KMO test is close to 0, the use of this analysis is inappropriate. On the other hand, if this value is close to 1, the analysis can be used. The Bartlett Sphericity Test indicates whether there is a sufficient relationship between the indicators to apply the analysis, that is, that the data correlation matrix is not the identity matrix. For this to be possible, a significance value of less than 0.05 is recommended (SILVA, 2009). Both tests demonstrated the suitability of this type of analysis.

Table 1.

KMO tests and Bartlett's Sphericity Test.

Table 1.

KMO tests and Bartlett's Sphericity Test.

To extract the main components, the correlation matrix was used based on the eigenvalue (greater than 1). The Varimax method was used to rotate the factors, with a rotated orthogonal display, to demonstrate the significant weights in the main components and that all others are close to zero. For the indicators presented, no commonalities lower than 0.500 were identified.

The Explained Total Variance Matrix was run for the indicators presented, contained in the questionnaire from the previous stage. The matrix presented the extraction of nine initial factors and a degree of explanation of 64.7% of the total variations. The anti-image matrix test was used to choose the final indicators. The anti-image matrix indicates the Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) for each of the variables (indicators), that is, it presents the explanatory power of the factors in each of the variables analyzed. The diagonal at the bottom of the table indicates the MAS for each of the variables analyzed. Values below 0.5 are considered too small for the analysis and indicate variables that can be removed from the analysis (Silva, 2009; Mendonça et al., 2016).

According to this criterion, eight indicators presented values below 0.500. Of these, three were not excluded. Two were mandatory information and the third, main administrative decisions, was identified as relevant in the previous stage, deserving additional comments from several participants. The excluded indicators were the current and future economic scenario of the Fund; Assets of your Fund; Profitability of the plan in which you participate; Legal demands that the Fund is involved in; and Services contracted by the fund.

The exclusion of these indicators is justified because they present somewhat redundant information, such as the economic scenario normally addressed in the board message indicator; equity and profitability are included in both the Balance Sheet and the Fund's Investment Statement, both of which are mandatory for disclosure. As for the others, this information is generally contained in the Explanatory Notes, as is the case with legal demands that have a specific explanatory note.

In summary, stage 1 was completed with 55 indicators, in stage 2 one was excluded (total 54) and in stage 3 the 54 indicators were maintained. In stage 4, four indicators were excluded and three were included, totaling 53 indicators. Finally, five indicators were excluded in stage 5. Thus, the final list consists of 48 indicators (

Table 2), 15 of which are mandatory, 15 recommended by Previc, and 18 voluntaries.

It is noteworthy that the higher the level of disclosure, the lower the asymmetry between the parties involved in a relationship (Leuz; Verrecchia, 2000; Kanagaretnam; Lobo; Whalen, 2007). Therefore, the practice of disclosure is a condition for reducing information asymmetry, allowing for a dialogue to adjust the interests between the parties involved in the relationship (Macagnan, 2009; Seibert, et al., 2019). The list of indicators created contains information that would help to reduce information asymmetry between the parties that constitute pension funds (Rozanov, 2015; Tan; Cam, 2015; Bradley; Pantzalis; Yuan, 2016), through its disclosure (Verrecchia, 2001).

It is understood that in this category of information demanded by stakeholders, some meet one or more of the following attributes, such as economic-financial sustainability, the power of the stakeholder to influence the organization; the stakeholder’s legitimacy in the relationship with the organization, and the urgency of stakeholder’s claims about the organization (Mitchell; Agle; Wood, 1997). In short, the adoption of a list of economic-financial indicators would contribute to increasing the trust of priority stakeholders in pension funds.

Thus, it would be up to pension funds to review their disclosure policies to meet the demands of their stakeholders. Such policies would reduce information asymmetry, minimizing the problem of moral hazard, which is characterized by the possibility of managers making decisions for their own benefit, to the detriment of the interests of the pension fund's stakeholders. Likewise, it indicates to regulatory bodies the need to improve the regulations on the AIR information that must be disclosed. These steps are essential when considering recommended future trends. The increase in the demand for private retirement, given the increase in people's life expectancy and the government's inability to meet retirements in the future (Brasil, 2009; OECD, 2016), indicates an increase in the resources available to pension fund managers, which need to be monitored more closely. Policymakers could boost transparency in these markets, helping generate better-informed policies, while providing beneficiaries with information relevant to their savings choices. It remains an open question as to whether beneficiary sustainability interests are truly being met and serviced (Fabian et al, 2023).

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to build a list of financial sustainability indicators, demanded by priority stakeholders of pension funds. Thus, unlike other studies in pension funds, dedicated to the study of disclosure based on literature or reports, and electronic pages or legislation and regulatory bodies, or even specialists, in which the normative prescription is evaluated or the perception is captured from the sender of the information and not from the recipient, the interested party, we sought to identify what information the retirees and participants demand as a way to reduce the information asymmetry existing between them and the fund managers.

It was identified that pension funds do not meet the expectations of their priority stakeholders, a lack of standardization between the AIRs presented by pension funds, and a low level of disclosure (45.6% on average), especially considering that these are the information demanded by the stakeholders. It is therefore up to pension fund managers to improve their disclosure policies to meet the interests of their legitimizing priority stakeholders.

It is also incumbent upon the regulatory bodies to establish greater rigor in the collection of mandatory disclosure and to review the guidelines for disclosure of information by these entities, aiming at standardizing disclosure. Standardization will contribute to reducing the asymmetry of information between the parties involved and, consequently, will minimize the possibility of moral hazard. Considering the tendency to increase the number of participants and resources made available to pension funds, arising from the lack of confidence in the government to guarantee public pensions, and the increase in expected life expectancy, the rigor in the control of these organizations should be greater than just a trend.

The study presented some limitations. It is noteworthy that the definition of indicators met the evaluation and validation stages defined by the researchers. Such steps may involve subjective designations, although multi-procedures have been performed, precisely to minimize this degree of subjectivity. In addition, validation with specialists and priority stakeholders involved the application of a questionnaire. It means that the analysis of these steps was based on the respondents' perception, not necessarily representing reality. The study did not address other interested parties, such as sponsors.

Therefore, considering the limitations, the analysis of the level of disclosure in the perception of sponsoring and instituting organizations is presented as a suggestion for future studies, as a way of aligning the disclosure carried out by pension funds in their respective AIRs. Also, the development of this research in other countries would be important. This research would provide the identification of similarities and differences in the interests of stakeholders in different positions in pension funds.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the construction and conclusion of this research: Medeiros, L. M.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation and Writing - original draft and review; Macagnan, C. B.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing; Seibert, R. M.: Supervision, Writing - original draft and review & editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review is not required for this study since human interaction is practically non-existent, and the data are confidential, analyzed in an aggregated manner.

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects involved expressed their consent to participate in the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

| ESG |

Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| AIR |

Annual Information Reports |

| PREVIC |

National Superintendency of Complementary Pension |

| ANAPAR |

National Association of Pension Fund Participants |

| SOCNA |

Statement of Changes in Net Assets |

| SONA |

Statement of Net Assets |

| SOAO |

Statement of Actuarial Obligations of the Benefit Plan |

| SOTP |

Statement of Technical Provisions |

| DB |

defined benefit |

| DC |

defined contribution |

| VC |

variable contribution |

| MSA |

Measure of Sampling Adequacy |

| BAL SH |

Balance Sheet |

| SOCSA |

Statement of Changes in Social Assets |

| SOAMP |

Statement of the Administrative Management Plan |

| AMP |

Administrative Management Plan |

References

- Abrapp (2023) Consolidado Estatístico Dezembro/2022. Available at: https://www.abrapp.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Consolidado-Estatistico_12.2022.pdf.

- Afonso, P. (2016) A relevância dos níveis de divulgação da informação das empresas cotadas portuguesas, Dissertação de Mestrado em Contabilidade, Fiscalidade e Finanças Empresariais, Lisbon School of Economics & Management, Universidade de Lisboa,.

- Akerlof, G. A. (1970) The market for “lemons”: quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Cambridge, v. 84, n. 3, p. 488- 500.

- Almeida, K. K. N.; Callado, A. L. C. (2017). Indicadores de desempenho ambiental e social de empresas do setor de energia elétrica brasileiro: uma análise realizada a partir da ótica da teoria institucional. Revista de Gestão, Finanças e Contabilidade, v. 7, n. 1, p. 222-239, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Anantharaman, D. (2017). The role of specialists in financial reporting: evidence from pension accounting. Review of Accounting Studies, v. 22, n. 3, p. 1261-1306, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Andonov, A.; Eichholtz, P.; Kok, N. (2015). Intermediated investment management in private markets: evidence from pension fund investments in real estate. Journal of Financial Markets, [s.l.], v. 22, p. 73-103, 2015.

- Arrow, K. J. (1962). Economic welfare and the allocation of resources for invention. In: The rate and direction of inventive activity: economic and social factors. [s.l.]: Princeton University Press, 1962. p. 609-626.

- Arrow, K. J. (1963). Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. The American Economic Review, [Baltimore], v. 53, n. 5, p. 941-973, 1963.

- Arrow, K. J. (2012). Economic theory and the financial crisis. Information Systems Frontiers, New York, v. 14, n. 5, p. 967-970, 2012.

- Attig, N.; Cleary, S. (2015). Managerial Practices and Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, n. 131, p. 121–136, 2015.

- Bachmann, R.; Carneiro, L.; Espejo, M. (2013). Evidenciação de informações ambientais: proposta de um indicador a partir da percepção de especialistas. Revista de Contabilidade e Organizações, n. 17, p. 36-47, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Bidabad, B.; Amirostovar, A.; Sherafati, M. (2017). Financial transparency, corporate governance and information disclosure of the entrepreneur’s corporation in Rastin banking. International Journal of Law and Management. v. 59, n. 5, p. 636-651, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Blake, d.; Lehmann, b.; Timmermann, A. (1999). Asset allocation dynamics and pension fund performance. Journal of Business, New York, v. 72, n. 4, p. 429-461, 1999. Available at: . Available at: URL (accessed 28 May 2016).

- Bradley, D.; Pantzalis, C.; Yuan, X. (2016). The influence of political bias in state pension funds. Journal of Financial Economics, v. 119, n. 1, p. 69-91, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Brasil (2001). Lei Complementar n. 109. Dispõe sobre o Regime de Previdência Complementar e dá outras providências. Brasília: DOU, 2001.

- Brasil (2004). Resolução do Conselho de Gestão da Previdência Complementar (CGPC), n. 13. Estabelece princípios, regras e práticas de governança, gestão e controles internos a serem observados pelas entidades fechadas de previdência complementar - EFPC. Brasília:DOU, 2004.

- Brasil (2006). Anuário estatístico da previdência social 2006. Brasília, DF: MPS, 2006a.

- Brasil (2006). Resolução MPS/CGPC n. 23. Dispõe sobre os procedimentos a serem observados pelas entidades fechadas de previdência complementar na divulgação de informações aos assistidos e participantes. Brasília, DF: MPS, 2006b.

- Brasil (2011). Resolução Conselho Nacional de Previdência Complementar (CNPC) n. 8. Dispõe sobre os procedimentos contábeis das entidades fechadas de previdência complementar, e dá outras providências. Brasília, 2011.

- Brasil (2013). Resolução Conselho Nacional de Previdência Complementar (CNPC) n. 12. Altera a Resolução nº 8, que dispõe sobre os procedimentos contábeis das entidades fechadas de previdência complementar. Brasília, 2013.

- Burgwal, D. V.; Vieira, R. J. (2014). Determinants of Environmental Disclosure in Dutch Public Companies. Revista de Contabilidade & Finanças, v. 25, n. 64, p. 60-78, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Bushman, R. M.; Smith, A. J. (2003). Transparency, financial accounting information, and corporate governance. FRBNY Economic Policy Review, v. 9, n. 1, p. 65-87, 2003.

- Buzby, S. L. (1975). Company size, listed versus unlisted stocks, and the extent of financial disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research, v. 13, n. 1, p. 16, 1975.

- Caamaño, P. C. (2007). Práticas de governança corporativa em Fundo de Pensão: estudo de um caso brasileiro. 2007. 134 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Sistemas de Gestão) - Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói, 2007.

- Carroll, A. (2016). Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, v. 1, n. 13, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Catalan, M. (2004). Pension funds and corporate governance in developing countries: what do we know and what do we need to know? Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, v. 3, n. 2, p. 197-232, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Cesar, A. M. R. V. C. (2015). Medidas de desempenho da área de recursos humanos e seu relacionamento com indicadores de desempenho econômico. Revista de Gestão, v. 22, n. 1, p. 97-114, 2015.

- Choi, F. D. S. (1973). Financial disclosure and entry to the european capital market. Journal of Accounting Research, v. 11, n. 2, p. 159-175, 1973.

- Clark, G. L. (1998). Pension fund capitalism: a casual analysis. Geografiska Annaler, New York, v. 80, n. 3, p. 139-157, 1998. Available at: . Acesso em: 19 jun. 2018.

- Clark, G. L. (2004). Pension fund governance expertise and organizational form. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, v. 3, n. 2, p. 233-253, 2004.

- Clark, G. L.; Monk, A. H. B. (2011). Partisan politics and bureaucratic encroachment: the principles and policies of pension reserve fund design and governance. SSRN Electronic Journal, May 2011. [CrossRef]

- Clement, R. W. (2005). The lessons from stakeholder theory for U.S. Business leaders. Business Horizons, n. 48, p. 255-264, 2005.

- Cooper, S.; Slack, R. (2015). Reporting practice, impression management and company performance: a longitudinal and comparative analysis of water leakage disclosure. Accounting and Business Research, v. 45, n. 6/7, p. 801-840, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Drew, M. E.; Stanford, J. D. (2003). Principal and agent problems in superannuation funds. The Australian Economic Review, [s.l.], v. 36, n. 1, p. 98-107, 2003.

- Dye, R. A. (2001). An evaluation of “essays on disclosure” and the disclosure literature in accounting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, v. 32, n. 2001, p. 181-235, Mar. 2001.

- Eaton, T. V.; Nofsinger, J. R.; Varma, A. (2014). Institutional investor ownership and corporate pension transparency. Financial Management, [s.l.], v. 43, n. 3, p. 603-630, 2014.

- Fabian, N.; Homanen, M.; Pedersen, N.; Slebos, M. (2023). Private Retirament System and Sustainability. In: Pension Funds and Sustainable Investment: challenges and opportunities. Hammod, P. B; Maurer, R.; and Mitchell, O. (eds). Oxford University Press, 2023.

- Forte, L. M. et al. (2015). Determinants of voluntary disclosure: a study in the Brazilian banking sector. Revista de Gestão, Finanças e Contabilidade, v. 5, n. 2, p. 23-37, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman, 1984.

- Freeman, R.; Harrison, J.; Wicks, A.; Parmar, B.; Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder Theory: The state of the art. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Freeman, R.; Reed, D. L. (1983). Stokeholders and Stakeholders: a new pespective on Corporate Governance. California Management Review, Los Angeles, v. 25, n. 3, p. 88-106, 1983.

- García Meca, E.; Martínez Conesa, I. (2004). Divulgación voluntaria de información empresarial: índices de revelación. Partida Doble: Revista de Contabilidad, Auditoría y Empresas, n. 157, p. 66-77, 2004.

- Geczy, C.; Guerard Jr., J. (2023). ESG and Expected Returns on Equities. In: Pension Funds and Sustainable Investment: challenges and opportunities. Hammod, P. B; Maurer, R.; and Mitchell, O. (eds). Oxford University Press, 2023.

- Giannetti, E.; Almeida, C. (2006). Ecologia Industrial - Conceitos, ferramentas e aplicações. São Paulo: Ed. Edgard Blücher, 2006.

- Gnanaweera, K.; Kunori, N. (2018). Corporate sustainability reporting: Linkage of corporate disclosure information and performance indicators. Cogent Business & Management, n. 5, p. 1-21, 2018.

- Gomariz, M. F. C.; Ballesta, J. P. S. (2014). Financial reporting quality, debt maturity and investment efficiency. Journal of Banking & Finance. V. 40, p. 494-506, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Grech, A. G. (2018). What Makes Pension Reforms Sustainable? Sustainability, n. 10, p.1-12, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Jannuzzi, P. D. M. Indicators for diagnosis, monitoring and evaluation of social programs in Brazil. Public Service Journal, Brasília, DF, v. 56, n. 2, p. 137-160, 2005.

-

Harrison, J. A.; Rouse, P; A Stakeholder perspective. The Business and Economics Research Journal, v. 5, n. 2: Villiers, C. J. (2012). Accountability and performance measurement; pp. 243–258.

- pension fund investors’ corporate transparency concerns. Journal of Business Ethics, Berlin, v. 63, n. 4: Hebb, T. (2006). The economic inefficiency of secrecy; pp. 385–405.

- Heink, U.; Kowarik, I. Heink, U.; Kowarik, I. (2010). What are indicators? On the definition of indicators in ecology and environmental planning. Ecological Indicators, v. 10, n. 3, p. 584-593, 2010.

-

Herrera-Rodríguez, E. E; //revistas.javeriana.edu.co/index: Macagnan, C. B. (2015). Bancos en Brasil y España: factores explicativos de revelación del capital relacional. Cuadernos de Contabilidad, Bogotá, v. 16, n. 40, p. 151-178, 2015. Available at: .

- Ionescu, O. C. (2013). The Evolution and Sustainability of Pension Systems the Role of the Private Pensions in Regard to Adequate and Sustainable Pensions. Journal of Knowledge Management, Economics and Information Technology. Special issue, Dec. 2013, p. 159-181.

- Kanagaretnam, K.; Lobo, G. J.; Whalen, D. J. Kanagaretnam, K.; Lobo, G. J.; Whalen, D. J. (2007). Does good corporate governance reduce information asymmetry around quarterly earnings announcements? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, v. 26, n. 4, p. 497-522, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Kanagaretnam, K.; Mestelman, S.; Nainar, K.; Shehata, M. Kanagaretnam, K.; Mestelman, S.; Nainar, K.; Shehata, M. (2010). Trust and reciprocity with transparency and repeated interactions. Journal of Business Research, n. 63, p. 241-247, 2010.

-

Khlif, H.; Guidara, A; Evidence from South Africa and Morocco. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies. v. 5, n. 1: Souissi, M. (2015). Corporate social and environmental disclosure and corporate performance; pp. 51–69. [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, O. Kowalewski, O. (2012). Corporate governance and pension fund performance. Contemporary Economics, v. 6, n. 1, p. 14-44, 2012. [CrossRef]

-

Jensen, M. C; managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, Amsterdam, v. 3: Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm; pp. 305–360.

- Lang, M. H. (2000) Voluntary disclosure; Research, equity offerings: reducing information asymmetry or hyping the stock? Contemporary Accounting; oboken; 17, v; 4, n; 623-662, p; mar, 2000. Available at: <http://doi.wiley.com/10.1506/9N45-F0JX-AXVW-LBWJ>. Acesso em: 10; et al. 2017.

- Leuz, C.; Verrecchia, R. E. Leuz, C.; Verrecchia, R. E. (2000). The economic consequences of increased disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research, v. 38, n. 2000, p. 91-124, 2000.

- Liesen, A.; Hoepner, A.; Ppatten, D.; Figge, F. Liesen, A.; Hoepner, A.; Ppatten, D.; Figge, F. (2015). Does stakeholder pressure influence corporate GHG emissions reporting? Empirical evidence from Europe. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, v. 28, n. 7, p. 1047-1074, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, C.; Fu, Q.; Li, M.; Faiz, M.; Khan, M.; Cui, S. Liu, D.; Liu, C.; Fu, Q.; Li, M.; Faiz, M.; Khan, M.; Cui, S. (2018). Construction and application of a refined index for measuring the regional matching characteristics between water and land resources. Ecological Indicators, n. 91, p. 203-211, 2018. [CrossRef]

- fatores explicativos da extensão da informação sobre recursos intangíveis. Revista de Contabilidade e Finanças, n. 50: Macagnan, C. B. (2009). Evidenciação voluntária; pp. 46–61. [CrossRef]

- Macagnan, C. B.; Seibert, R. M. Macagnan, C. B.; Seibert, R. M. (2021). Sustainability Indicators: Information Asymmetry Mitigators between Cooperative Organizations and Their Primary Stakeholders. Sustainability, v. 13, n. 8217, p. 1-16, 2021. [CrossRef]

-

Marston, C. L; a review article. British Accounting Review, v. 23: Shrives, P. J. (1991). The use of disclosure indices in accounting research; pp. 195–210.

- USP: Mendonça, D. J. et al. (2016). Utilização da análise fatorial para identificação dos principais indicadores de avaliação de desempenho econômico-financeiro: uma aplicação em instituições financeiras bancárias. In: Congresso USP de Controladoria e Contabilidade, 16., 2016, São Paulo. Anais... São Paulo.

- Minayo, M. Minayo, M. (2009). Construção de indicadores qualitativos para avaliação de mudanças. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica, v. 33, n. 1, p. 83-91, 2009. [CrossRef]

-

Mitchell, O. S.; Piggott, J; best practices and new questions. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, v. 7, n. 3: Kumru, C. (2008). Managing public investment funds; pp. 321–356. [CrossRef]

-

Mitchell, R. K.; Agle, B. R; defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, v. 22, n. 4: Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience; pp. 853–886.

-

Mitchell, O. S.; Hammond, P. B; challenges and opportunities: Maurer, R. (2023). Sustainable Investment in Retirement Funds: introduction. In: Pension Funds and Sustainable Investment.

- The Need for Sustainable Regulation. American Business Law Journal, v. 59, n. 4: Muir, D. M. (2022). Sustainable Investing and Fiduciary Obligations in Pension Funds; pp. 621–677.

- Naczyk, M. Naczyk, M. Domonkos, S. (2016). The financial crisis and varieties of pension privatization reversals in Eastern Europe. Governance, 29(2), 167-184, 2016. [CrossRef]

- OECD: OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2003). OECD guidelines for the protection of rights of members and beneficiaries in occupational pension plans. Paris.

- OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation, Development (2016). OECD core principles of private pension regulation. [S.l.]: OECD; abr, 2016. Available at: <http://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/private-pensions/Core-Principles-Private-Pension-Regulation.pdf>. Acesso em: 10. 2017.

- OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development (2023). Pension Markets in Focus, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Evolution of a paradigm: Orenstein, M. A. (2013). Pension privatization. [CrossRef]

-

Paula, R. A; a comparative analysis in the light of IAS 26. Accounting Evidenciation & Finance Journal. v. 2, n. 2: Lima, D. V. (2014). Grip of Financial Statements of Pension Funds in Brazil to International Accounting Standards; pp. 69–81.

-

Pesci, C.; Costa, E; insights from Hume's notion of ‘impressions. Accounting and Business Research, v. 45, n. 6-7: Soobaroyen, T. (2015). The forms of repetition in social and environmental reports; pp. 765–800. [CrossRef]

- Pink, G. Pink, G. H; Holmes, G. M.; D’alpe, C.; Strunk, L. A.; Mcgee, P.; Slifkin, R. T. (2006). Financial Indicators for Critical Access Hospitals. National Rural Health Association. V. 22, n. 3, p. 229-236, 2006.

- Pivac, S.; Vuko, T.; Cular, M. Pivac, S.; Vuko, T.; Cular, M. (2017). Analysis of annual report disclosure quality for listed companies in transition countries. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, v. 30, n. 1, p. 721–731, 2017. [CrossRef]

-

Quagli, A.; Lagazio, C; a country-level composite indicator. Journal of Management and Governance, v. 25: Ramassa, P. (2021). From enforcement to financial reporting controls (FRCs); pp. 397–427. [CrossRef]

- Rose, P. Rose, P. A (2015). Disclosure Framework for Public Fund Investment Policies. Procedia Economics and Finance, v. 29, p. 5 – 16, 2015.

- best practice and international experience. Asian Economic Policy Review, v. 10, n. 2: Rozanov, A. (2015). Public pension fund management; pp. 275–295. [CrossRef]

- Sao Jose, A.; Figueiredo, M. Sao Jose, A.; Figueiredo, M. (2011). Modelo de proposição de indicadores globais para organização das informações de responsabilidade social. VII Congresso Nacional de Excelência em Gestão, p. 01-19, 2011.

- Searcy, C.; Dixon, S. M.; Neumann, P. W. Searcy, C.; Dixon, S. M.; Neumann, P. W. (2016). The use of work environment performance indicators in corporate social responsibility reporting. Journal of Cleaner Production, v. 112, p. 2907-2921, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Seibert, R. M. (2017). Determinants of disclosure of information representing social responsibility: a study in philanthropic higher education institutions. 208 f. Thesis (Doctorate in Accounting Sciences) - Postgraduate Program in Accounting Sciences, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos (UNISINOS), 2017. 2017. [Google Scholar]

-

Seibert, R. M; Novas Edições Acadêmicas: Macagnan, C. B. (2017). Social responsibility: The transparency of Philanthropic Higher Education Institutions. Beau Bassin, Maurítius.

- Seibert, R. M.; Macagnan, C. B. Seibert, R. M.; Macagnan, C. B. (2019). Social responsibility disclosure determinants by philanthropic higher education institutions. Meditari Accountancy Research, v. 27, n. 2, p. 258-286, 2019. [CrossRef]

-

Seibert, R. M.; Macagnan, C. B.; Dixon, R; perspective of stakeholders in Brazil and in the UK. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, v. 16, n. 2-3: Simon, D. (2019). Social responsibility indicators; pp. 128–144. [CrossRef]

- Seibert, R. M.; Macagnan, C. B.; Dixon, R. Seibert, R. M.; Macagnan, C. B.; Dixon, R. (2021). Priority Stakeholders’ Perception: Social Responsibility Indicators. Sustainability, v. 13, n. 1034, p. 1-22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Singhvi, S. S.; Desai, H. B. Singhvi, S. S.; Desai, H. B. (1971). An empirical analysis of the quality of corporate financial disclosure. The Accounting Review, v. 46, n. 1, p. 129-138, 1971.

- Stiglitz, J. Stiglitz, J. (2000). The contributions of the economics of information to twentieth century economics. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, v. 115, n. 4, p. 1441-1478, 2000.

-

Stadler, I. M; Editorial Ariel: Castrillo, D. P. Introducción a la Economía de la Información. Barcelona.

- Previc: PREVIC - Superintendência Nacional de Previdência Complementar (2014). Guia PREVIC: melhores práticas contábeis para entidades fechadas de previdência complementar. Brasília, DF.

- Regert, R.; Borges Junior, G. M.; Bragagnolo, S. M.; Baade, J. H. Regert, R.; Borges Junior, G. M.; Bragagnolo, S. M.; Baade, J. H. A (2018). Importância dos Indicadores Econômicos, Financeiros e de Individamento como Gestão do Conhecimento na Tomada de Decisão em Tempos de Crise. Visão. V. 7, n. 2, p. 67-83, 2018.

- USP: Silva, V. F. (2009). Performance de indicadores financeiros de seguradoras no Brasil: uma análise de componentes principais. In: Congresso USP de Contabilidade e Controladoria, 9., 2009, São Paulo. Anais... São Paulo.

- Stiglitz, J. Stiglitz, J. (2000). The contributions of the economics of information to twentieth century economics. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Cambridge, v. 115, n. 4, p. 1441- 1478, 2000.

- Tan, M. G. S.; Cam, M. A. Tan, M. G. S.; Cam, M. A. (2015). Does governance structure influence pension fund fees and costs? An examination of Australian not-for-profit superannuation funds. Australian Journal of Management, v. 40, n. 1, p. 114-134, 2015. [CrossRef]

-

Urquiza, F. B.; Navarro, M. C. A; does it make a difference? Revista de Contabilidad, v. 12, n. 2: Trombetta, M. (2009). Disclosure indices design; pp. 253–277.

- Verdi, R. Verdi, R. (2006). Reporting Quality and Investment Efficiency. Electronic Journal, Sep 2006. [CrossRef]

- Varella, C. A. A. (2008). Multivariate analysis applied to Agricultural Sciences: principal component analysis. Seropédica: Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro; abr, 2008. Available at: <http://www.ufrrj.br/institutos/it/deng/varella/Downloads/multivariada aplicada as ciencias agrarias/Aulas/analise de componentes principais.pdf>. Acesso em: 10. 2017.

- Verrecchia, R. E. Verrecchia, R. E. (1990). Information quality and discretionary disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, Amsterdam, v. 12, n. 4, p. 365-380, 1990.

- Verrecchia, R. E. Verrecchia, R. E. (2001). Essays on disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, v. 32, n. 1-3, p. 97-180, 2001.

- The World Bank: Vittas, D. (2002). Policies to promote saving for retirement: a synthetic overview. Washington.

- Welbeck, E.; Owusu, G.; Bekoe, R.; Kusi, J. Welbeck, E.; Owusu, G.; Bekoe, R.; Kusi, J. (2017). Determinants of environmental disclosures of listed firms in Ghana. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, v. 2, n. 11, p. 01-12, 2017. [CrossRef]

-

Zaini, M. S; a literature review. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies. v. 8, n. 1: Et Al. (2017). Voluntary disclosure in emerging countries; pp. 29–65. [CrossRef]

Table 2.

Final ratio of indicators.

Table 2.

Final ratio of indicators.

| INDICATOR |

GUY |

| 1 |

TQSA - Technically Qualified Statutory Administrator |

voluntary / recommended |

| 2 |

Changes to the Board of Directors |

voluntary |

| 3 |

ARBP -Administrator Responsible for The Benefit Plan |

voluntary / recommended |

| 4 |

Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting of the Executive Board |

voluntary |

| 5 |

Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting of the Deliberative Council |

voluntary / recommended |

| 6 |

Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting of the Fiscal Council |

voluntary / recommended |

| 7 |

Balance Sheet (BAL SH) |

obligatory |

| 8 |

Certification of Directors |

voluntary / recommended |

| 9 |

Composition of the Council and Executive Board |

voluntary / recommended |

| 10 |

Administrative decisions |

voluntary |

| 11 |

Statement of Changes in Net Assets of Benefit Plan (SOCNA) |

obligatory |

| 12 |

Statement of Changes in Social Assets (SOCSA) - consolidated |

obligatory |

| 13 |

Statement of Technical Provisions of the Benefit Plan (SOTP) |

obligatory |

| 14 |

Statement of Net Assets of Benefit Plan (SONA) |

obligatory |

| 15 |

Cash Flow Statement |

voluntary |

| 16 |

Statement of the Administrative Management Plan (SOAMP) - consolidated |

obligatory |

| 17 |

Administrative Expenses |

obligatory |

| 18 |

Outsourced Management |

voluntary / recommended |

| 19 |

Glossary |

voluntary |

| 20 |

Information if the board member is a sponsor or participant representative |

voluntary |

| 21 |

Contact Information/Communication Channels |

voluntary / recommended |

| 22 |

Information on document changes (Statute/Regulation) |

voluntary / recommended |

| 23 |

Information about elections / nomination / selection - Deliberative and Fiscal Council |

voluntary / recommended |

| 24 |

Information about elections / nomination / selection - Executive Board |

voluntary / recommended |

| 25 |

List of Debts (Contracts and Debit Balance) of the Sponsors |

voluntary |

| 26 |

List of Sponsors/Institutors |

voluntary |

| 27 |

Manifestation/Opinion of the Deliberative Council |

obligatory |

| 28 |

Message from the Board of Directors |

voluntary |

| 29 |

Mini curriculum of the Executive Board |

voluntary / recommended |

| 30 |

Explanatory Notes |

obligatory |

| 31 |

Number of Participants |

voluntary |

| 32 |

Organization chart |

voluntary / recommended |

| 33 |

Actuarial Opinion Report |

obligatory |

| 34 |

Opinion of the Supervisory Board |

obligatory |

| 35 |

Prospects for next year |

voluntary |

| 36 |

Administrative Management Plan (AMP) |

obligatory |

| 37 |

Terms of Office of the Executive Board |

voluntary |

| 38 |

Term of Office of the Deliberative and Fiscal Council |

voluntary |

| 39 |

Number of Benefits Granted in the Year |

voluntary |

| 40 |

Number of Human Resources |

voluntary |

| 41 |

Report of the Independent Auditors |

obligatory |

| 42 |

Specific Report on Internal Controls |

voluntary / recommended |

| 43 |

Remuneration of Directors |

voluntary |

| 44 |

Summary of Investment Policy |

obligatory |

| 45 |

Summary of the Investment Statement |

obligatory |

| 46 |

Financial Health of the Sponsor |

voluntary |

| 47 |

Taxation System of plans |

voluntary |

| 48 |

Total Benefits Granted/Paid |

voluntary |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).