Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Search and Data Collection

Selection and Exclusion Criteria

3. Result

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

3.4. Results of Meta-Analysis

3.4.1. URTI Meta-Analysis

3.4.2. Meta-Analysis for OM Treatment

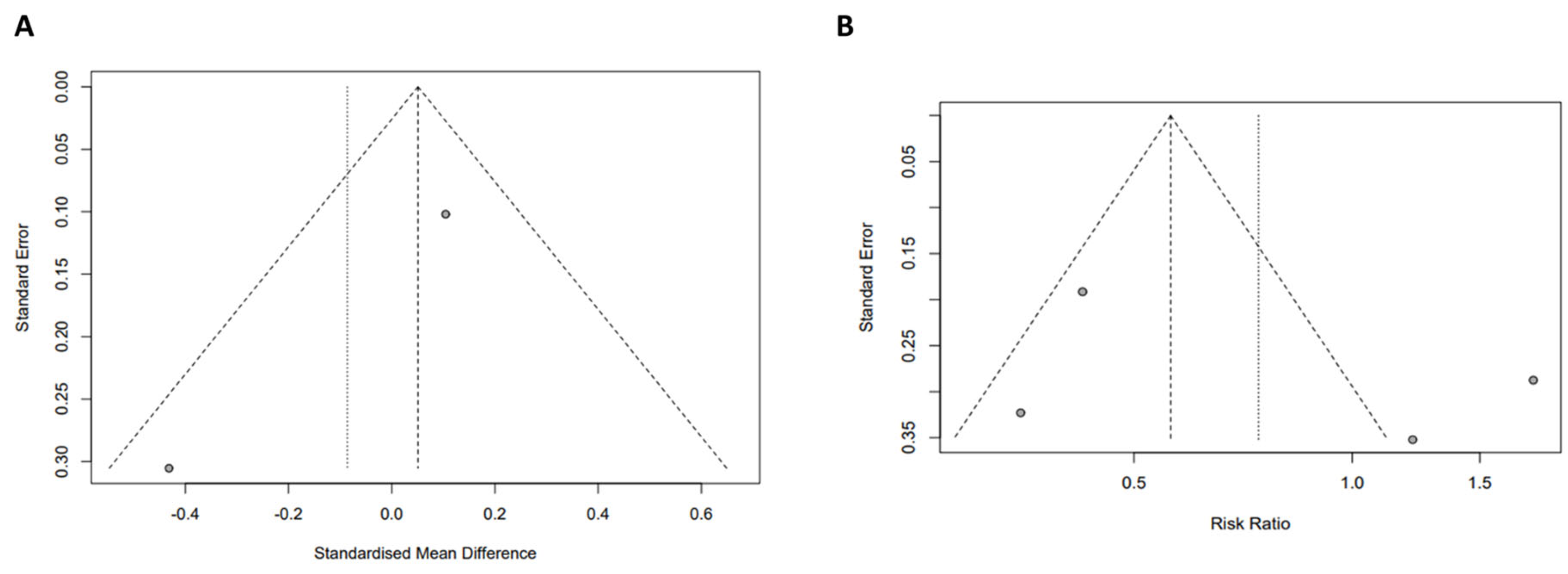

3.5. Quality Assessment of Meta-Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Findings

4.2. Significance of the Study

4.3. Differences from Previous Studies

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Crawford C, Brown LL, Costello RB, Deuster PA. Select Dietary Supplement Ingredients for Preserving and Protecting the Immune System in Healthy Individuals: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2022 Nov 1;14(21):4604. [CrossRef]

- Quynh, Thuy D, Khiem V, Thien N, Ha HA. Phytochemical Profiling of Echinacea Genus: A mini Review of Chemical Constituents of Selected Species. 2023.

- Sumer J, Keckeis K, Scanferla G, Frischknecht M, Notter J, Steffen A, et al. Novel Echinacea formulations for the treatment of acute respiratory tract infections in adults-A randomized blinded controlled trial. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:948787. [CrossRef]

- Burlou-Nagy C, Bănică F, Jurca T, Vicaș LG, Marian E, Muresan ME, et al. Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench: Biological and Pharmacological Properties. A Review. Plants (Basel). 2022 May 5;11(9):1244. [CrossRef]

- DeGeorge KC, Ring DJ, Dalrymple SN. Treatment of the Common Cold. Am Fam Physician. 2019 Sep 1;100(5):281–9.

- Thomas M, Bomar PA. Upper Respiratory Tract Infection. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [cited 2024 Apr 28]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532961/.

- Abdel-Naby Awad OG. Echinacea can help with Azithromycin in prevention of recurrent tonsillitis in children. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41(4):102344.

- Khan EA, Raja MH, Chaudhry S, Zahra T, Naeem S, Anwar M. Outcome of upper respiratory tract infections in healthy children: Antibiotic stewardship in treatment of acute upper respiratory tract infections. Pak J Med Sci. 2020;36(4):642–6. [CrossRef]

- Korppi M, Heikkilä P, Palmu S, Huhtala H, Csonka P. Antibiotic prescribing for children with upper respiratory tract infection: a Finnish nationwide 7-year observational study. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181(8):2981–90. [CrossRef]

- Wahl RA, Aldous MB, Worden KA, Grant KL. Echinacea purpurea and osteopathic manipulative treatment in children with recurrent otitis: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2008 Oct 2;8(1):56. [CrossRef]

- David S, Cunningham R. Echinacea for the prevention and treatment of upper respiratory tract infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2019 Jun;44:18–26. [CrossRef]

- Vu TMH, Hoang TV, Nguyen TQH, Doan PMK, Nguyen TTD, Bui TTT, et al. Echinacea purpurea: An overview of mechanism, efficacy, and safety in pediatric upper respiratory infections and otitis media. International Journal of Plant Based Pharmaceuticals. 2024 Jun 16;4(2):90–100. [CrossRef]

- Maggini V, Bandeira Reidel RV, De Leo M, Mengoni A, Rosaria Gallo E, Miceli E, et al. Volatile profile of Echinacea purpurea plants after in vitro endophyte infection. Nat Prod Res. 2020 Aug;34(15):2232–7. [CrossRef]

- Petrova A, Ognyanov M, Petkova N, Denev P. Phytochemical Characterization of Purple Coneflower Roots (Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench.) and Their Extracts. Molecules. 2023 Jan;28(9):3956.

- Pham TPT, Hoang TV, Cao PTN, Le TTD, Ho VTN, Vu TMH, et al. Comparison of Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids bioavailability in fish oil and krill oil: Network Meta-analyses. Food Chemistry: X. 2024 Dec;24:101880. [CrossRef]

- Covidence [Internet]. [cited 2024 May 14]. Covidence - Better systematic review management. Available from: https://www.covidence.org/.

- Blobaum P. Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). J Med Libr Assoc. 2006 Oct;94(4):477–8.

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997 Sep 13;315(7109):629–34.

- Cohen HA, Varsano I, Kahan E, Sarrell EM, Uziel Y. Effectiveness of an herbal preparation containing echinacea, propolis, and vitamin C in preventing respiratory tract infections in children: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004 Mar;158(3):217–21.

- Taylor JA, Weber W, Standish L, Quinn H, Goesling J, McGann M, et al. Efficacy and safety of echinacea in treating upper respiratory tract infections in children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003 Dec 3;290(21):2824–30.

- Wustrow TPU, Otovowen Study Group. Alternative versus conventional treatment strategy in uncomplicated acute otitis media in children: a prospective, open, controlled parallel-group comparison. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004 Feb;42(2):110–9. [CrossRef]

- Ogal M, Johnston SL, Klein P, Schoop R. Echinacea reduces antibiotic usage in children through respiratory tract infection prevention: a randomized, blinded, controlled clinical trial. Eur J Med Res. 2021 Apr 8;26(1):33.

- Weishaupt R, Bächler A, Feldhaus S, Lang G, Klein P, Schoop R. Safety and Dose-Dependent Effects of Echinacea for the Treatment of Acute Cold Episodes in Children: A Multicenter, Randomized, Open-Label Clinical Trial. Children (Basel). 2020 Dec 15;7(12):292.

- Barrett B. Efficacy and safety of echinacea in treating upper respiratory tract infections in children: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2004 Jul;145(1):135–6. [CrossRef]

- Weber W, Taylor JA, Stoep AV, Weiss NS, Standish LJ, Calabrese C. Echinacea purpurea for prevention of upper respiratory tract infections in children. J Altern Complement Med. 2005 Dec;11(6):1021–6. [CrossRef]

- Spasov AA, Ostrovskij OV, Chernikov MV, Wikman G. Comparative controlled study of Andrographis paniculata fixed combination, Kan Jang and an Echinacea preparation as adjuvant, in the treatment of uncomplicated respiratory disease in children. Phytother Res. 2004 Jan;18(1):47–53.

- Sayegh AS, Eppler M, Sholklapper T, Goldenberg MG, Perez LC, La Riva A, et al. Severity Grading Systems for Intraoperative Adverse Events. A Systematic Review of the Literature and Citation Analysis. Annals of Surgery [Internet]. 2023 Apr 27 [cited 2024 Nov 1]; Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/SLA.0000000000005883. [CrossRef]

- Schoop R, Klein P, Suter A, Johnston SL. Echinacea in the prevention of induced rhinovirus colds: A meta-analysis. Clinical Therapeutics. 2006 Feb 1;28(2):174–83. [CrossRef]

- Tyler S. Chapter 13: Physical Development in Early Childhood. 2020 May 26 [cited 2024 Jan 14]; Available from: https://uark.pressbooks.pub/hbse1/chapter/physical-development-in-early-childhood_ch_13/.

- Erceg D, Jakirović M, Prgomet L, Madunić M, Turkalj M. Conducting Drug Treatment Trials in Children: Opportunities and Challenges. Pharm Med [Internet]. 2024 May 10 [cited 2024 May 14]; Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Applequist W. Echinacea. The Genus Echinacea. ebot. 2005 Jan;59(1):98–98.

- Liu YC, Zeng JG, Chen B, Yao SZ. Investigation of Phenolic Constituents in Echinacea purpurea Grown in China. Planta Med. 2007 Dec;73(15):1600–5. [CrossRef]

- Bałan BJ, Różewski F, Zdanowski R, Skopińska-Różewska E. Review paper<br>Immunotropic activity of Echinacea. Part I. History and chemical structure. Cent Eur J Immunol. 2012;37(1):45–50.

- Liu Q, Qin C, Du M, Wang Y, Yan W, Liu M, et al. Incidence and Mortality Trends of Upper Respiratory Infections in China and Other Asian Countries from 1990 to 2019. Viruses. 2022 Nov 18;14(11):2550. [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Ren J, Li R, Gao Y, Zhang H, Li J, et al. Global burden of upper respiratory infections in 204 countries and territories, from 1990 to 2019. EClinicalMedicine. 2021 Jul;37:100986. [CrossRef]

- Karsch-Völk M, Barrett B, Kiefer D, Bauer R, Ardjomand-Woelkart K, Linde K. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Feb 20;2014(2):CD000530.

- Linde K, Barrett B, Wölkart K, Bauer R, Melchart D. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Jan 25;(1):CD000530.

- Shah SA, Sander S, White CM, Rinaldi M, Coleman CI. Evaluation of echinacea for the prevention and treatment of the common cold: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007 Jul;7(7):473–80. [CrossRef]

- Anheyer D, Cramer H, Lauche R, Saha FJ, Dobos G. Herbal Medicine in Children With Respiratory Tract Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(1):8–19. [CrossRef]

- Kenealy T, Arroll B. Antibiotics for the common cold and acute purulent rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jun 4;2013(6):CD000247.

- Sur DKC, Plesa ML. Antibiotic Use in Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections. Am Fam Physician. 2022 Dec;106(6):628–36.

- Abdel Rahman AN, Khalil AA, Abdallah HM, ElHady M. The effects of the dietary supplementation of Echinacea purpurea extract and/or vitamin C on the intestinal histomorphology, phagocytic activity, and gene expression of the Nile tilapia. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018 Nov;82:312–8. [CrossRef]

- Echinacea Extract - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics [Internet]. [cited 2024 May 16]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/echinacea-extract.

- Wei FH, Xie WY, Zhao PS, Gao W, Gao F. Echinacea purpurea Polysaccharide Ameliorates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis by Restoring the Intestinal Microbiota and Inhibiting the TLR4-NF-κB Axis. Nutrients. 2024 Apr 26;16(9):1305. [CrossRef]

- Hafiz NM, El-Readi MZ, Esheba G, Althubiti M, Ayoub N, Alzahrani AR, et al. The use of the nutritional supplements during the covid-19 outbreak in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Complement Ther Med. 2023 Mar;72:102917. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Calderón AI. Rational and Safe Use of the Top Two Botanical Dietary Supplements to Enhance the Immune System. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2022;25(7):1129–30. [CrossRef]

- Choudhary S, Khan S, Rustagi S, Rajpal VR, Khan NS, Kumar N, et al. Immunomodulatory Effect of Phytoactive Compounds on Human Health: A Narrative Review Integrated with Bioinformatics Approach. Curr Top Med Chem. 2024 Mar 27. [CrossRef]

- Elvir Lazo OL, White PF, Lee C, Cruz Eng H, Matin JM, Lin C, et al. Use of herbal medication in the perioperative period: Potential adverse drug interactions. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2024 Aug;95:111473.

- Kakouri E, Talebi M, Tarantilis PA. Echinacea spp.: The cold-fighter herbal remedy? Pharmacological Research - Modern Chinese Medicine. 2024 Mar;10:100397.

- Adebimpe Ojo C, Dziadek K, Sadowska U, Skoczylas J, Kopeć A. Analytical Assessment of the Antioxidant Properties of the Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea L. Moench) Grown with Various Mulch Materials. Molecules. 2024 Feb 22;29(5):971.

- Abdel-Wahhab KG, Elqattan GM, El-Sahra DG, Hassan LK, Sayed RS, Mannaa FA. Immuno-antioxidative reno-modulatory effectiveness of Echinacea purpurea extract against bifenthrin-induced renal poisoning. Sci Rep. 2024 Mar 11;14(1):5892. [CrossRef]

- Dehn Lunn A. Reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in upper respiratory tract infection in a primary care setting in Kolkata, India. BMJ Open Qual. 2018 Nov;7(4):e000217.

- Djaoudene O, Romano A, Bradai YD, Zebiri F, Ouchene A, Yousfi Y, et al. A Global Overview of Dietary Supplements: Regulation, Market Trends, Usage during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and Health Effects. Nutrients. 2023 Jul 26;15(15):3320. [CrossRef]

- Brykman MC, Streusand Goldman V, Sarma N, Oketch-Rabah HA, Biswas D, Giancaspro GI. What Should Clinicians Know About Dietary Supplement Quality? AMA J Ethics. 2022 May 1;24(5):E382-389.

- Mathur MB, VanderWeele TJ. Sensitivity analysis for publication bias in meta-analyses. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series C, Applied Statistics. 2020 Aug 28;69(5):1091. [CrossRef]

| Study | Patient population |

Species, part | Dose | Dosage form, Manufac-turer | Patient number | Research group characteristics | Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treat-ment | Placebo | Treatment | Placebo | ||||||

| Barrett B., 2004 [24] | 2-11 years URTI |

E. purpurea aerial parts |

Not reported | -Solution -England |

337 | 370 | Not reported | Not reported | -Treatment time -Adverse event |

| Cohen H.A., 2004 [19] | 1-5 years -URTI and OM |

E. purpurea aerial parts, E. angustifolia root |

-1-3 years: 2x5 mL/day -4-5 years: 2x7,5mL/day |

-Solution -USA |

215 | 215 | Echinacea, propolis, vitamin C | Propolis, vitamin C | -Treatment time -Number of times having at least one episode |

| Ogal M., 2021 [22] | 4-12 years -URTI and OM |

-E. purpurea root, aerial parts |

-Echinacea: 3x400mg/day -Vitamin C: 3x50mg/day |

-Tablet Switzerland |

104 | 99 | Echinacea, ethanolic | Vitamin C (axit ascorbic and canxi ascorbate) | -Treatment time -Adverse event -Number of times having at least one episode -Rate of antibiotic use |

| Taylor J.A., 2003 [20] | 2-11 years URTI |

-E. purpurea, the above-ground herb harvested at flowering | -2-5 years: 7,5mL/day (2 x 3,75 mL/day) -6-11 years: 10mL/day (2x5mL/day) |

-Solution -USA |

337 | 370 | Echinacea non-alcohol | Syrup | -Treatment time -Adverse event -Number of times having at least one episode |

| Wahl R.A., 2008 [10] | 1-5 years URTI and OM |

-E. purpurea, the fresh roots and dried mature seeds |

3x0,5mL/day during first 3 day, then 3x0,25mL/day in the next 7 days | -Solution -USA |

44 |

46 | Echinacea, ethanol | Ethanol, filtered water, food coloring and thickeners | -Treatment time -Adverse events -Number of times having at least one episode |

| G. Wikman, 2004 [26] | 4-11 years URTI |

- E. purpurea (part not specified) |

-Echinacea: 10 drops (3 times/day) -Andrographis paniculata: 3x2 capsules/day |

-Nasal drops -Russia -Tablet - Sweden |

94 | 39 | Echinacea, ethanol, Andrographis paniculata (N.) | Warm drinks, throat gargles, antiseptic nose drops, and paracetamol at a dose of 500 mg 3 times a day in cases of fever and severe headache |

-Adverse event -Rate of antibiotic use |

| Weber W., 2006 [25] | 2-11 years URTI |

-E. purpurea, the above-ground plant parts harvested at flowering |

-2-5 years: 87,75mg ( 2 x ¾ teaspoon/ day) -6-11 years: 117mg (2x1 teaspoon/day) |

-Solution -Germany |

263 | 261 | Echinacea non-alcohol | Placebo liquid | -Treatment time -Adverse events -Number of times having at least one episode |

| Weishaupt R., 2020 [23] | 4-12 years URTI |

-E. purpurea root | -Low dose: 3 capsules/day -Hight dose: 5 capsules/day |

-Tablet - Switzerland |

79 | Echinacea, ethanolic | -Treatment time -Adverse events -Number of times having at least one episode -Rate of antibiotic use |

||

| Wustrow T.P.U., 2004 [21] | 1-10 years OM |

-E. purpurea (part not specified) |

Not reported | -Nasal drops -Germany |

194 | 196 | Alternative treatment with medicine Otovowen contain hightly concentrated liquid plant extracts of Echinacea and some other plant species |

Conventional treatment not treated with medicine Otovowen | -Treatment time -Rate of antibiotic use |

| PEDro criteria | Study | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrett 2004 [24] | Cohen 2004 [19] | Ogal 2021 [22] | Taylor 2003 [20] | Wahl 2008 [10] | Wikman 2004 [26] | Weber 2006 [25] | Weishaupt 2020 [23] | Wustrow 2004 [21] | |

| 1. Eligibility* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Randomization | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 3. Concealed allocation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4. Baseline comparability | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5. Blind subject | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 6. Blind therapist | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7. Blind assessor | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 8. Adequate follow-up | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 9. Intention-to-treat analysis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10. Between-group comparisons | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 11. Point estimate variability | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total score | 9/10 | 8/10 | 7/10 | 9/10 | 10/10 | 6/10 | 8/10 | 6/10 | 5/10 |

| Study quality | Excellent | Good | Good | Excellent | Excellent | Good | Good | Good | Moderate |

| Adverse reactions | Severity | Detailed description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allergic reactions | Mild | Mild urticaria; itchiness; rash; choking | [20,22,25,26] |

| Gastrointestinal Issues | Mild-Moderate | Vomiting; diarrhea; stomachache | [20,22,23] |

| Infections | Moderate | Stomatitis; conjunctivitis | (23) |

| Fever | Mild | Some users may experience mild fever, though this is uncommon; scarlet fever | [22,23] |

| Dizziness | Mild | Some individuals may feel mild dizziness after taking E. purpurea | (23) |

| Drowsiness or Insomnia | Mild-Moderate | Some users may feel drowsy, while others might experience insomnia | (20) |

| Headaches | Mild-Moderate | Mild to moderate headaches may occur, particularly with prolonged use of E. purpurea | [20,22] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).