I. Introduction

Most of the practical engineering application problems, such as electrical and electronic engineering problem, civil engineering problem, are multiobjective optimization problems (MOPs) [

1]. MOPs not only contain multiple conflicting objectives simultaneously, but the objectives are usually time-varying and coupled with each other. The presence of multiple conflicting objectives can give rise to a set of trade-off solutions known as Pareto Front in the objective space and Pareto Set in the decision space, respectively [

2]. Since, it is practically different to obtain the entire Pareto Front solutions, an approximation non-dominated solutions can be obtained. The original multiobjective optimization approaches are usually based on transforming the MOP to several single objectives by the different weight method and then obtaining a set of non-dominated optimal solutions. Therefore, traditional optimization methods have many drawbacks, such as high computational complexity and long time, so they cannot meet the requirements of speed, convergence and diversity [

3].

Generally speaking, to obtain the accurate solution set when solving the complex MOPs, researchers draw lessons from the laws of nature and biology to design a class of multiobjective evolutionary algorithms (MOEAs) for improve the convergence accuracy. As an important field of artificial intelligence, MOEA has made many breakthroughs in algorithm theory and algorithm performance, because of its characteristics of intelligence and parallelism. It has played an important role in scientific research and production practice. During the last two decades, MOEA has widely become a new research direction, because it has better global search ability and does not rely on the specific mathematical model and characteristics of solving the problem when solving the multi-objective optimization problem [

4,

5]. The performance of MOEAs is mainly evaluated by a set of non-dominated solutions obtained by the performance metrics, including the convergence metric and diversity metric. In general, the typical MOEAs include the multiobjective genetic algorithm (MOGA) [

6], the multiobjective differential evolution (MODE) algorithm [

7], and so on [

8,

9,

10]. It is precisely this way that deepening the research of computational intelligence algorithm can promote the development of intelligent technology and promote innovation in many fields. Distinguishingly, the multiobjective particle swarm optimization (MOPSO) algorithm based on the bird population shows complex intelligent behavior through the cooperation of simple individual particles, and uses social sharing among the bird population to promote the evolutionary process of the algorithm. Therefore, MOPSO realizes the transcendence of the swarm intelligence that can exceed the outstanding individual particle intelligence [

11]. Meanwhile, due to the few key operation parameters, high convergence speed and ease of implementation, MOPSO can handle with many kinds of objective functions and constraints.

In MOPSO community, the key parameters can impact the exploitation ability and exploration ability in the searching process of particles [

12]. Meanwhile, different updating methods will guide the particles to search different area and then affect the performance of the whole population. With the increasing number of iterations, more and more non-dominated solutions will be generated [

13]. As the amount of calculation increase, the archive cannot accommodate the whole non-dominated solutions [

14]. The convergence and diversity of the non-dominated solutions in the archive will become important. In order to reach to good convergence and diversity of the non-dominated in the archive, the three main optimization stages which including the update of the archive, the selection of the global best and the key flight parameter adjustment will be concerned. Like all MOEAs, MOPSO is also need an explicit diversity mechanism to preserve the non-dominated solutions in the archive. In [

15], a selection procedure was proposed to prune the non-dominated solutions. In order to obtain have a good diversity of the archive, a novel reproduction operator based on the differential evolution was presented, which can to create potential solutions, and accelerate the convergence toward the Pareto set [

16]. The MOPSO emerged as a competitive and cooperative form of evolutionary computation in the last decade, one of the most special features of MOPSO is the updating of the global best (gBest) and personal best (pBest) [

17,

18]. Aiming at the selection of the gBest and pBest, a novel parallel cell coordinate system (PCCS) is proposed to accelerate the convergence of MOPSO by assessing the evolutionary environment [

19]. Another important feature is the parameter adjustment, for example, the inertia weight can achieve the balance of the exploration and exploitation. And the coefficients adjustment can also influence movement of the particle. In [

20], a time varying flight parameter mechanism was proposed for the MOPSO algorithms. At present, there are many performance metrics in multiobjective optimization to determine the convergence and diversity of MOPSO. The main performance metrics of MOPSO contain the determination of convergence and diversity. Meanwhile, different application environments of MOPSO will consider different performance metrics and impact the future development trend.

At present, especially in the complex science field, MOPSO has effectively solved the problem which is difficult to describe in many complex systems. It breaks through the limitations of the traditional multiobjective optimization algorithm, and has been used in many applications in various academic and industrial fields so far [

61]. MOPSO has made encouraging progress in many applications in various academic and industrial fields so far, which is including the automatic control system [

62], communication theory [

63], medical engineering [

64], electrical and electronic engineering [

65], communication theory [

66], fuel and energy [

67] and so on.

According to the analysis and studies on MOPSO, it has become a popular algorithm to solve the complex MOPs. The typical characteristics are summarized as follows.

1) Different from the cross mutation operation of other optimization algorithms, MOPSO is much more simple and straightforward to implement. As an MOEA based on birds group, MOPSO shows complex intelligent behavior through the cooperation of simple individual particles, and uses social sharing among groups to promote the evolutionary process of the algorithm. Therefore, realizing the breakthrough of the swarm intelligence on MOPSO that can exceed the excellent individual particle intelligence.

2) As indicated by the current studies on MOPSO, it has few key parameters. It can be seen from the updating formula of MOPSO algorithm that the position and speed of the particle are greatly influenced by the key parameters. The convergence of the algorithm is the fundamental guarantee of its application. The effect of the key parameters of the MOPSO algorithm on the convergence of the algorithm is analyzed in detail, and the flight direction of the particles is calculated by the state transfer matrix. The constraint condition [

97] that satisfies the parameters of particle trajectory is obtained.

3) Compared with other MOEAs, the fast convergence is a typical Characteristics of MOPSO. Since the flight direction of MOPSO can be obtained by the gBest and pBest of the population, the whole particle swarm is easy to gathering or dispersing. Therefore, the convergence rate of MOPSO will be relatively faster than other MOEAs.

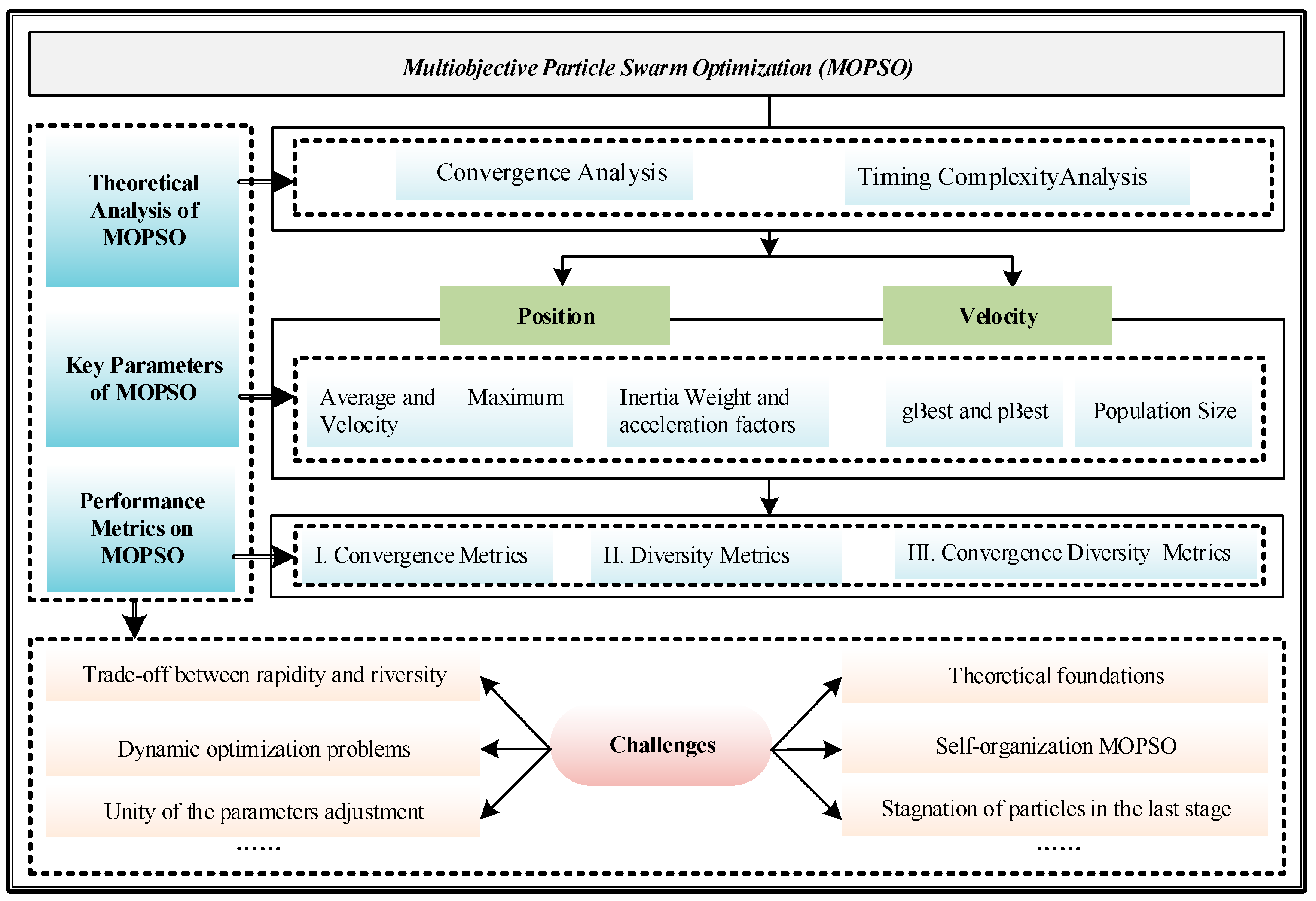

In order to make a summary of the work in the last two decades, we discussed the achievements and the direction of development, and wrote this review article. This paper attempts to provide a comprehensive survey of the MOPSO. The major scheme of this paper is shown in

Figure 1. Section II briefly describes the basic concepts and key parameters of MOPSO. In Sections III, the improved approaches of MOPSO by different performance metrics are presented, and the theoretical analysis of MOPSO have been presented. Then, Sections IV gives the potential future research challenges of MOPSO. Finally, the paper is concluded in section V.

II. Characteristics of Multiobjective Particle Swarm Optimization

Faced with the complex MOPs in practical application, the traditional optimization method has the problems of high computational complexity and long time, which cannot meet the requirements of in computing speed, convergence, diversity and so on. In order to solve the complex MOPs better, scientists draw lessons from the laws of nature and biology to design a computational intelligence algorithm for solving the problem. As an important field of artificial intelligence, computational intelligence algorithm has made many breakthroughs in algorithm theory and algorithm performance because of its characteristics of intelligence and parallelism. However, MOPSO algorithm is a typical computational intelligence algorithm with strong optimization ability. It has been able to solve the multi-objective optimization problem which is difficult to establish accurate models in many complex systems.

A. Basic Concept of MOPSO

MOPSO is a population-based optimization technique, in which the population is referred as a swarm. A particle has a position which is represented by a vector:

where

D is the dimension of the search space,

i=1, 2, …,

S,

S is the size of the swarm. And each particle has a velocity which is recorded as:

In the evolutionary process,

pi(

t) is the best previous position of the particle at the

tth iteration which is recorded as

pi(

t)=[

pi,1(

t),

pi,2(

t),…,

pi,D(

t)], and

gBest(

t) is the best position found by the swarm which is recorded as

gBest(

t)=[gBest

1(

t), gBest

2(

t),…, gBest

D(

t)]. A global best solution gBest can be found by the whole particle swarm. In each iteration, the velocity is updated by:

where

i=1, 2, …,

s,

t represents the

tth iteration in the evolutionary process;

d=1, 2, …,

D represents the

dth dimension in the searching space;

ɷ is the inertia weight, which is used to control the effect of the previous velocities on the current velocity;

c1 and

c2 are the acceleration constants,

r1 and

r2 are the random values uniformly distributed in [0, 1]. Then the new position is updated as:

And the pseudocode of the basic MOPSO algorithm is presented in

Table 1. MOPSO is a typical population-based MOEA, which includes these following characteristics:

Remark1: MOPSO is a population-based evolutionary algorithm which is inspired by the social behavior of the birds flocking motion, which has been steadily gaining attention from the research community because of its high convergence speed. The aggregate motion of the whole particles formed the searching movement of MOPSO algorithm. Like other evolutionary algorithm, MOPSO suffers from a notable bias: they tend to perform best when the optimum is located at or near the center of the initialization region, which is often the origin.

In MOPSO, particles move through the search space using an information interaction between particles, and each particle is attracted by the personal and global best solutions to move to their potential leader. Particles can be connected to each other in any kind of neighborhood topology which containing the ring neighborhood topology, the fully connected neighborhood topology, the star network topology and tree network topology. For instance, due to the fully connected topology that all particles are connected to each other, each particle can receive the information of the best solution from the whole swarm at the same time. Thus, when using the fully connected topology, the swarm is inclined to converge more rapidly than when using other local best topologies [

43].

Remark2: In the searching process of a MOPSO algorithm, when the convergence is considered separately, it may lead to the local optimal trap. If the diversity is considered separately, the convergence speed and quality will be an unsolved problem. In the optimization process of MOPSO algorithm, many optimization patterns could exert an influence on the optimization results, in terms of leader selection, archive maintenance, the flight parameter adjustment, population size and perturbation. Therefore, these several important aspects will become the key means to improve the optimization effect. The leader selection affects the convergence capability and the distribution of non-dominated solutions along the Pareto Front.

B. Key Parameters of MOPSO

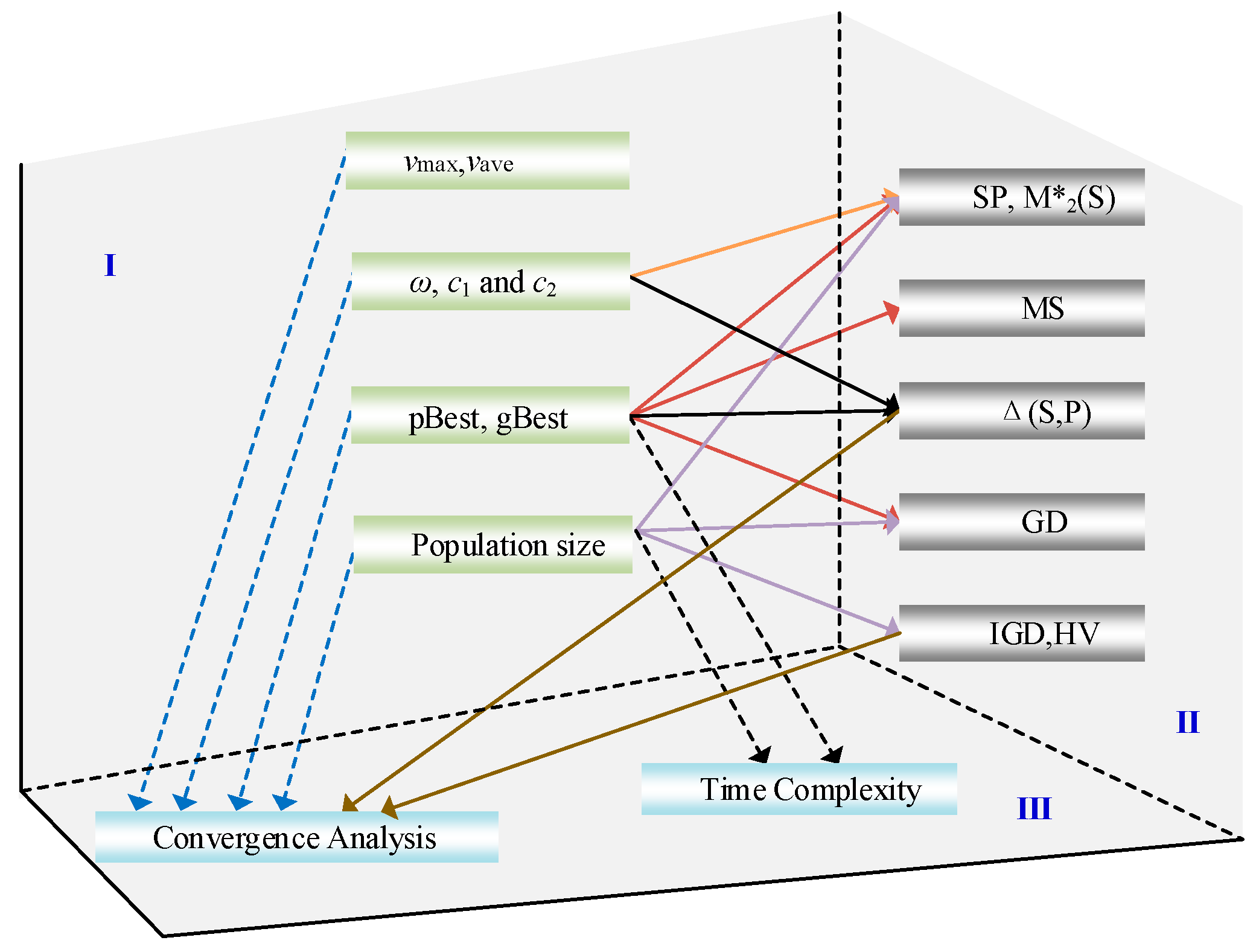

The relationship between the key parameters is depicted in

Figure 2.

(a) Average and maximum velocity

MOPSO algorithm makes full use of share learning factor to modify the velocity updating formulas, which aims to improve the global search ability [

41]. The optimal value of maximum velocity is problem specific. Further when maximum velocity was implemented the particle’s trajectory failed to converge. From the velocity updating formula of the particle, it can be seen that the velocity of the particle is subjected to the key parameters (

ω,

c1 and

c2) of the particles. The contribution rate of a particle’s previous velocity to its velocity at the current time step is determined by the key parameters [

42]. It is necessary to limit the maximum of the velocity. For example, if the velocity is very large, particles may fly out of the search space and decrease the searching quality of MOPSO algorithm. In contrast, if the velocity is very small, particles may trap into the local optimum. In order to hinder too quick movement of particles, their velocities are bounded to specified values [

51].

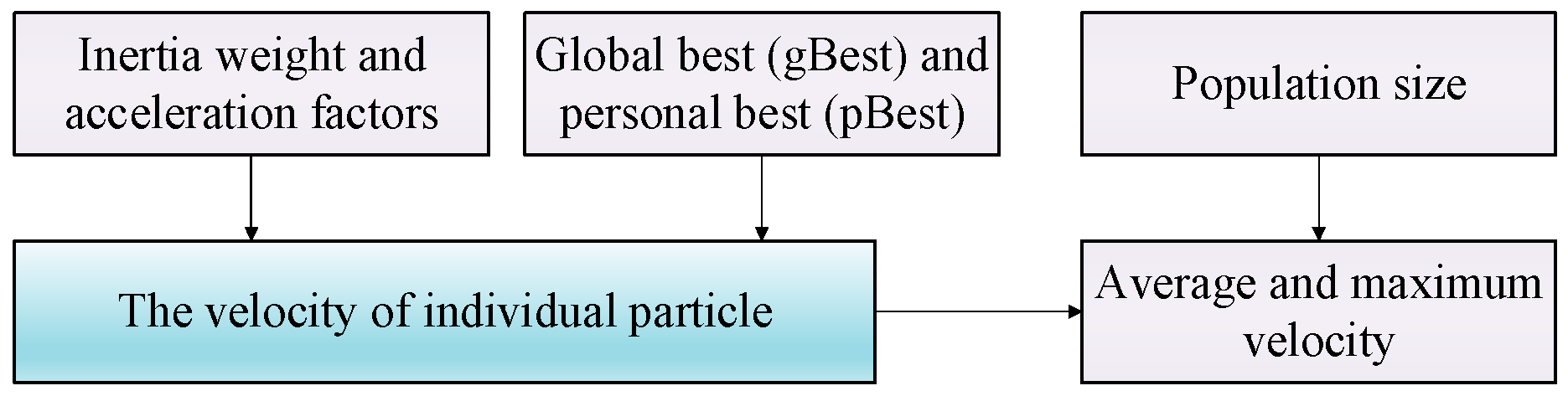

(b) Inertia weight and acceleration factors

From the flight equations, it is clearly shown that new position of each particle is affected by the inertia weight

ω and another two cognitive acceleration coefficient

c1 and

c2. The acceleration coefficient

c1 prompts the attraction of the particle towards its own pBest and the acceleration coefficient

c2 prompts the attraction of the particle towards the gBest. The parameter inertia weight

ω, helps the particles converge to personal and global best, rather than oscillating around it. The inertia weight controls the influence of previous velocities on the new velocity [

42].

Too high values of cognitive acceleration coefficient weakens exploration ability, while too high values of social acceleration coefficient leads to weak exploitation capability [

51]. Therefore, suitable cognitive acceleration coefficients is very important for the optimization process of a MOPSO algorithm. Most of the prior research have indicated that the inertia weight

ω controls the impact of the previous velocity on the current velocity, which is employed to trade-off between the global and local exploration abilities of the particles [

41]. Moreover, the purpose of designing the adaptive inertia weight is to balance the global and local search ability of the particles. Most previous works have demonstrate that a larger inertia weight

ω facilitates global exploration, while a small inertia weight tends to facilitate local exploration to guide to the current search area. Suitable selection of inertia weight

ω can provide balance between global and local exploration abilities and thus require less iteration on average to find the optimum. In the previous research, different inertia weight mechanisms have been designed to balance the global searching ability and the local searching ability, which the inertia weight was adjusted dynamically to adapt the optimization process.

(c) Global best (gBest) and personal best (pBest)

In MOPSO, each particle moves toward the most promising directions guided by the gBest and the pBest together, and the whole population follows the trajectory of gBest [

23]. The gBest and the pBest can guide the evolutionary direction of the whole population. In addition, the updating formula of the MOPSO algorithm have illustrated that the value of the gBest and the pBest can play an important role on the updating of the velocity and position. In the searching process, selecting the appropriate gBest and the pBest in MOPSO is a feasible way to control its convergence and promote its diversity. In recent years, the popular issue of gBest selection is keeping the balance of convergence and diversity. Some researchers have proposed adaptive selection mechanisms which selecting the gBest with convergence and diversity feature by the dynamic evolutionary environment.

(d) Population size

The population size of the MOPSO does indirectly contribute to the effectiveness and efficiency of the performance of an algorithm [

36]. One contribution of population size on these population-based evolutionary algorithms is the computational cost.

In the searching process, if an algorithm employs an overly large population size, it will enjoy a better chance of exploring the search space and discovering possible good solutions but inevitably suffer from an undesirable and high computational cost. In contrary, an MOPSO algorithm with an insufficient population size may trap into the premature convergence or may obtain the solution archive with a loss of diversity.

The external archive can store a certain number non-dominated solution which determine the convergence and diversity performance of MOPSO. Although there are many external archive strategies which have been proposed, several strategies can achieve a good balance between the diversity and convergence. In addition, the research on the external archive strategies is still necessary for improve the performance of MOPSO as a whole. On one hand, diversity is one of the most characteristics in the external archive of MOPSO, which reflects validity of the MOPs to be solved. On the other hand, convergence is another criterion to judge performance of MOPSO and approach to the true Pareto Front.

Remark3: The convergence and diversity are two principals for evaluating the performance of MOPSO. Meanwhile, the adjustments of the key parameters can affect the flight direction of particles and then obtain different optimization performance. However, the performance metrics have been designed with different standpoints to evaluate the performance of MOPSO. Three typical performance criteria have been considered in multiobjective optimization: 1) the number of the non-dominated solutions. 2) the convergence of non-dominated solutions to the Pareto Front. 3) the diversity of non-dominated solutions in the objective space. In particular, a set of optimal non-dominated solutions with best convergence and diversity which are approaching the true Pareto Front and scattering evenly are generally desirable.

III. Different Performance Metrics of MOPSO

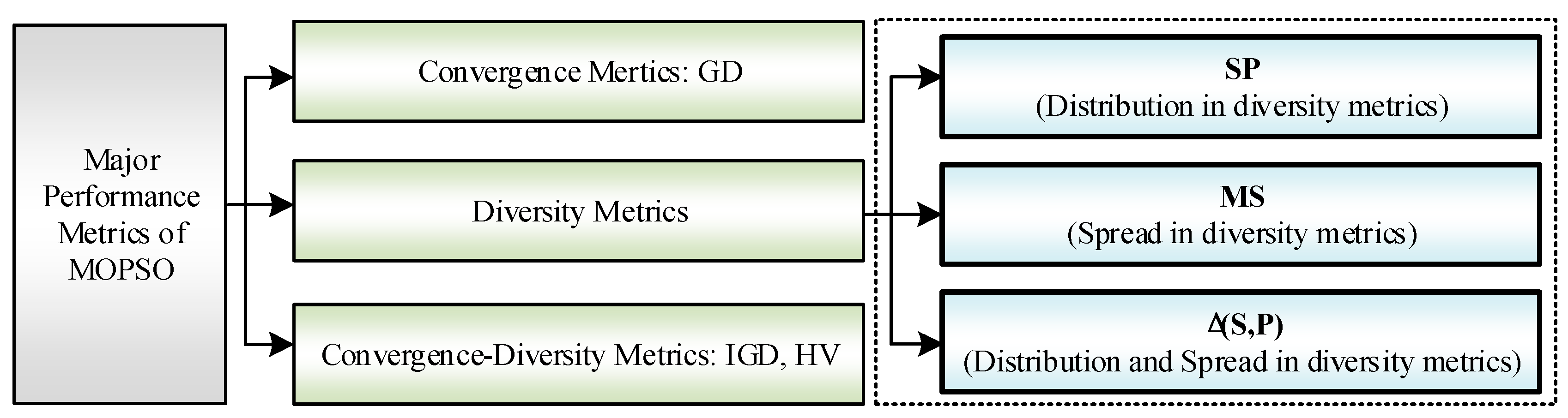

In the multiobjective optimization performance metrics, two major performance criteria, namely, convergence, and diversity, have typically been taken into considerations. Based on the convergence and diversity performance of MOPSO, the existing improved approaches categorized into three groups.

1) Diversity metrics: These metrics contain two aspects: a) Distribution measures whether evenly scattered are the optimal non-dominated solutions and b) spread demonstrates whether the optimal non-dominated solutions approach to the extrema of the Pareto Front.

2) Convergence metrics: These metrics can measure the degree of approximation between the optimal non-dominated solutions by the proposed MOPSO and the true Pareto Front.

3) Convergence-diversity metrics: These metrics can both indicate measure the convergence and diversity of the optimal non-dominated solutions.

According to above-mentioned analysis, the major performance metrics of MOPSO are shown in

Figure 3.

Figure 2.

The major performance metrics of MOPSO.

Figure 2.

The major performance metrics of MOPSO.

Figure 3.

The major relation of the key parameters, the performance metrics and the theoretical analysis of MOPSO.

Figure 3.

The major relation of the key parameters, the performance metrics and the theoretical analysis of MOPSO.

A. Diversity Metrics

Diversity metrics demonstrate the distribution and spread of the solutions in the archive.

(a) Distribution in Diversity Metrics

The distribution quality of the non-dominated solutions in the archive is an important aspect to reflect the diversity performance of MOPSO algorithm.

The spacing (SP) metric: The distribution is derived from the non-dominated solutions in the archive, which is defined as:

where

,

∈

S. di is minimum Euclidean distance between the solution

∈

S and the solutions

∈

S.

is the average Euclidean distance of all the

di. If the value of SP is larger, it will represent a poor distribution of the diversity. In contrary, the smaller SP can indicate the MOPSO algorithm with good distribution performance.

SP is used to measure the spread of vectors throughout the non-dominated vectors found so far. Since the “beginning” and “end” of the current Pareto front found are known, a suitably defined metric judges how well the solutions in such front are distributed. A value of zero for this metric indicates all members of the Pareto front currently available are equidistantly spaced. This metric addresses the second issue from the list previously provided.

The

metric in [

56] is equipped with a niche radius σ and takes the form of

where,

,

measures how many solutions

are located in its local vicinity

. σ is a niche radius. Note that a niche neighboring size to calculate the distribution of the non-dominated solution. The higher the value of

, the MOPSO algorithm can obtain good distribution of the non-dominated solutions.

-

a)

Increasing the diversity of the non-dominated solutions in the archive

Raquel

et al. presented an extended approach by incorporating the mechanism of crowding distance computation into the developed MOPSO algorithm to handle the MOPs, which the global best selection and the deletion method of the external archive have been used. The results show that the proposed MOPSO algorithm can generate a set of uniformly distributed non-dominated solutions closing to the Pareto Front [

38].

Coello

et al. proposed an external repository strategy to guide the flight direction of particles, which including the archive controller and an adaptive grid [

20]. The archive controller is designed to control the storage of non-dominated solutions in the external archive, and the adaptive grid is used to distribute in a uniform way to obtain the largest possible amount of hypercubes. The external repository strategy also incorporate a special mutation operator method which improves the exploratory capabilities of the particles and enriches the diversity of the MOPSO algorithm. Moreover, Moubayed

et al. developed a MOPSO by incorporating dominance with decomposition (D

2MOPSO), which employs a new archiving technique that facilitates attaining better diversity and coverage in both objective and solution spaces [

25].

Agrawal

et al. proposed a fuzzy clustering-based particle swarm optimization (FCPSO) algorithm to solve the highly constrained conflicting multiobjective problems. The results indicated that it generated a uniformly distributed Pareto front whose optimality has been proved greater than ε-constrainted method [

35].

A multiobjective particle swarm optimization is proposed in [

48], which uses a fitness function derived from the maximin strategy to determine Pareto-domination. The results show that the proposed MOPSO algorithm produces an almost perfect convergence and spread of solutions towards and along the Pareto Front.

-

b)

The inertia weight adjustment mechanisms improved the global exploration ability

Daneshyari

et al. introduced a cultural framework to design a flight parameter mechanism for updating the personalized flight parameters of the mutated particles in [

28]. The results show that this flight parameter mechanism performs efficiently in exploring solutions close to the true Pareto front. In addition, a parameter control mechanism was developed to change the parameters for improving the robustness of MOPSO.

-

c)

Selecting the proper gBest and pBest with better diversity

Ali

et al. introduced an attributed MOPSO algorithm, which can update the velocity of each dimension by selecting the gBest solutions from the population [

29]. The experiments indicate that the attributed MOPSO algorithm can improve the search speed in the evolutionary process. In [

30], a multiobjective particle swarm optimization with preference- based sort (MOPSO-PS), in which the user’s preference was incorporated into the evolutionary process to determine the relative merits of non-dominated solutions, was developed to choose the suitable gBest and pBest. After each optimization, the most preferable particle can be chosen as the gBest by the selection of the highest global evaluation value.

Zheng

et al. introduced a new MOPSO algorithm, which can maintain the diversity of the swarm and improve the performance of the evolving particles significantly over some state-of-the-art MOPSO algorithms by using a comprehensive learning strategy [

24]. Torabi

et al. introduced an efficient MOPSO with a new fuzzy multi-objective programming model to solve an unrelated parallel machine scheduling problem. The proposed MOPSO exploits a new selection regimes for preserving global best solutions and obtains a set of non-dominated solutions with good diversity [

55].

-

d)

Dividing the particle population into multi groups

Zhang

et al. introduced an enhanced by problem-specific local search techniques (MO-PSO-L) to seek high-quality non-dominated solutions. The local search technique has been specifically designed for searching more potential non-dominated solutions in the vacant space. The computational experiments have verified that the proposed MO-PSO-L can deal with complex MOPs [

59].

The effective archive strategy can generate a group of uniformly distributed non dominant solutions and can accurately approach the Pareto frontiers. At the same time, the effective archive strategy can guide the direction of the particle flight. The external knowledge base strategy also contains a special mutation operator method, which can improve the searching ability of the particles. In order to balance the global exploration ability and the local exploitation ability of the particle, the time-varying flight parameter mechanism can update the flight parameters by iteration and adjust the value of the inertia weight. It can strengthen the global searching ability of the algorithm and obtain more optimal solutions. For multiple constrained multiobjective conflicting problem, the clustering method is used to divide the non dominant solution in the archive into multiple subgroups, which can enhance the local search performance of each subgroup. The dominating relationship is determined by calculating the fitness value of the target function, so that the non-dominanted solution in the archive can be distributed evenly.

(b) Spread in Diversity Metrics

The spread of diversity is another typical aspect to reflect the diversity performance of MOPSO algorithms.

The maximum spread (MS) metric: The spread quality of the non-dominated solutions in the archive can also represent the diversity, and MS is defined as:

where,

Fimax is the maximum value of the

ith objective in Pareto Front,

Fimin is the minimum value of the

ith objective in Pareto Front.

fimax is the maximum value of the

ith objective in the solution archive,

fimin is the minimum value of the

ith objective in the solution archive. Most of the previous work show that the larger MS, the better spread of the diversity will be obtained by the evolutionary algorithm in the archive.

The maximum spread is conceived to reveal how well obtained optimal solutions covers the true Pareto front. The larger the MS value is, the better the obtained optimal solutions covers the true Pareto front. The limiting value MS=1 means the obtained optimal solutions covers completely the true Pareto front.

-

a)

Selecting the proper gBest and pBest with better diversity

Shim

et al. proposed an estimation distribution algorithm to model the global distribution of the population for balancing the convergence and diversity of the MOPSO algorithms [

27]. The results indicate that this method can improve the convergent speed.

Multimodal multiobjective problems are usually posed as several single objective problems that sometimes including more than one local optimum or several global optimum. To handle the multimodal multiobjective problems effectively, Yue

et al. proposed a multi-objective particle swarm optimizer using an index-based ring topology to maintain a set of non-dominated solutions with good distribution in the decision and objective spaces [

22]. Further, the experimental results show that the proposed algorithm can obtain a larger MS value and have made great progress on solving the decision space distribution.

-

b)

Increasing the diversity of the non-dominated solutions in the archive

Huang et al. proposed a multiobjective comprehensive learning particle swarm optimizer (MOCLPSO) algorithm by integrating an external archive technique to handle MOPs. Simulation results show that the proposed MOCLPSO algorithm is able to find a much better spread of solutions and faster convergence to true Pareto Front [

39].

(c) Distribution and Spread in Diversity Metrics

The metric Δ is introduced in [

6], which consider to reflect the distribution and spread of the non-dominated solutions in the archive simultaneously. The formulation of Δ is derived as follows:

where,

di is the Euclidean distance between consecutive solutions,

is the average of all

di.

df and

dl are the minimum Euclidean distance between the extreme solutions in the true Pareto Front and the boundary solutions of the non-dominated solutions in the archive,

S is the capacity of the archive.

In order to increase the diversity for dealing with MOPs, Tsai

et al. proposed an improved multi-objective particle swarm optimizer based on proportional distribution and jump improved operation (PDJI-MOPSO). The proposed PDJI-MOPSO maintains diversity of new found non-dominated solutions via proportional distribution and obtains extensive exploitations of MOPSO algorithm in the archive with the jump improved operation to enhance the solution searching abilities of particles [

47].

-

a)

Increasing the diversity of the non-dominated solutions in the archive

Cheng

et al. proposed a hybrid MOPSO with local search strategy (LOPMOPSO), which consists of the quadratic approximation algorithm and the exterior penalty function method. The dynamic archive maintenance strategy is applied to improve the diversity of solutions, and the experimental results show that the proposed LOPMOPSO is highly competitive in convergence speed and generate a set of non-dominated solutions with good diversity [

53]. Ali

et al. proposed an attributed multiobjective comprehensive learning particle swarm optimizer (A-MOCLPSO), which optimize the total security cost and the residual damage. The experimental results show that the proposed A-MOCLPSO algorithm can provide diverse solutions for the problem and outperform the previous solutions obtained by other comparable algorithms [

54].

In order to effectively deal with the multimodal and complex MOPs, a group of non-dominated solutions with good distribution can be obtained by changing the information sharing mode between particles in the decision and objective space, and a great progress has been made in solving the distribution of decision space. In view of multimodal problem and MOPs in noisy environment, it is necessary to consider the extension of MOPSO algorithm and analyze the MS metric.

B. Convergence Metrics

Convergence metrics measure the degree of the proximity which the distance between the non-dominated solutions and the Pareto Front.

The generational distance (GD) metric: The essence of GD is to calculate the distance the non-dominated solution in the archive and the true Pareto Front, which is defined as:

where, a finite number of the non-dominated solutions that approximates the true Pareto Front is called as

P, the optimal non-dominated solution archive obtained by the evolutionary algorithms is termed as

S. |

S| is the number of the non-dominated solutions in the archive,

,

∈

S and

q=2,

di is the minimum Euclidean distance between the solution

∈

S and the solutions in

P. In essence, GD can reflect the convergence performance of MOPSO algorithm.

GD illustrates the convergence ability of the algorithm by measuring the closeness between the Pareto optimal front and the evolved Pareto front. Thus, a lower value of GD shows that the evolved Pareto front is closer to the Pareto optimal front. It should be clear that a value of indicates that all the elements generated are in the Pareto optimal set. Therefore, any other value will indicate how “far” we are from the global Pareto front of our problem. This metric addresses the first issue from the list previously provided.

(a) The Inertia Weight Adjustment Mechanisms Improved the Local Exploitation Ability

Tang

et al. introduced a self-adaptive PSO (SAPSO) based on a parameter selection principle to guarantee the convergence when handling the MOPs. To gain a well-distributed Pareto front, an external repository was designed to keep the non-dominated solutions with a good convergence. The statistical results of GD have illustrated the proposed SAPSO can obtain a set of non-dominated solutions closed to the Pareto Front [

58].

(b) Speeding up the Convergence by the External Archive

Zhu

et al. introduced a novel external archive-guided MOPSO (AgMOPSO) algorithm, where the leaders for velocity updating and position updating are selected from the external archive [

21]. In AgMOPSO, MOPs are transformed into a set of sub-problems and each particle is allocated to optimize a sub problem. Meanwhile, an immune-based evolutionary strategy of the external archive increased the convergence to the Pareto Front and accelerated the speed rate. Different from the existing algorithms, the proposed AgMOPSO algorithm is devoted to exploit the useful information fully from the external archive to enhance the convergence performance. In [

23], a novel parallel cell coordinate system (PCCS) is proposed to accelerate the convergence of MOPSO by assessing the evolutionary environment. The PCCS have transformed the multiobjective functions into two-dimensional space, which can accurately grasp the distribution of the non-dominated solutions in high-dimensional space. An additional experiment for density estimation in MOPSO illustrates that the performance of PCCS is superior to that of adaptive grid and crowding distance in terms of convergence and diversity.

Wang

et al. developed a multiobjective optimization algorithm with the preference order ranking of the non-dominated solutions in the archive [

44]. And the experimental results indicated that the proposed algorithm improves the exploratory ability of MOPSO and converges to the Pareto Front effectively.

(c) Selecting Proper gBest and pBest

Alvarez

et al. developed a MOPSO algorithm using exclusively on dominance for selecting guides from the solution archive to finding more feasible region and explore regions closed to the boundaries. The results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm can shrink the velocity of the particles and the particle can flight to the boundary of the true Pareto Front, which having a good GD value [

37].

Wang

et al. developed a new ranking scheme based on equilibrium strategy for MOPSO algorithm to select the gBest in the archive, and the preference ordering is used to decreases the selective pressure, especially when the number of objectives is very large. The experimental results indicate that the proposed MOPSO algorithm produces better convergence performance [

50].

(d) Adjusting the Population Size

A multiple-swarm MOPSO algorithm, named dynamic multiple swarms in MOPSO, is proposed in which the number of the swarms are dynamic in the searching process. Yen

et al. proposed a dynamic multiple swarms in MOPSO (DSMOPSO) algorithm to manage the communication within a swarm and among swarms and an objective space compression and an expansion strategy to progressively exploit the objective space during the search process [

34]. The proposed DSMOPSO algorithm occasionally exhibits slower search progression, which may render larger computational cost than other selected MOPSOs.

In order to solve the application problem with the increasing complexity and dimensionality, Goh

et al. developed a MOPSO algorithm with the competitive and cooperative co-evolutionary approach, which dividing the particle swarms into several sub-swarms [

46]. Simulation results demonstrated that proposed MOPSO algorithm can retain the fast convergence speed to the Pareto Front with a good GD value.

(e) Hybrid MOPSO Algorithms

In order to increase the convergence accuracy and the speed of MOPSO algorithm, MOSPO combined with other intelligent algorithm. In [

49], an efficient MOPSO algorithm based on the strength Pareto approach from EA was developed. The experimental results show that the proposed MOPSO algorithm can converge to the Pareto Front and have a slower convergence time than the SPEA2 and a competitive MOPSO algorithm. MOPSO can also combine with other global optimization algorithms. The evaluation of GD index is relatively simple, mainly considering the distance between all non-dominated solutions in the external archive and the frontier, but cannot provide diversity information.

The evaluation of GD metric is relatively simple, which mainly considers the distance between all non-dominated solutions and the Pareto front in the archive, but it can not provide the diversity. Because the calculation of the GD metric needs the real Pareto front, but the actual problem often has no real Pareto front, so its use will be limited. However, for the multiobjective optimization problem of the known front, it is suitable for MOPs with strict convergence when handling the actual problems.

C. Convergence-Diversity Metrics

The aim of optimizing MOPs is to obtain a set of uniformly distributed non-dominated solutions which is close to the true Pareto Front. In order to evaluate the optimal solutions in the archive, two performance metrics are applied to measure the MOPSO algorithm which can reflect both the convergence and diversity performance.

The inverted generational distance (IGD) metric: IGD is used to compare the disparity between the non-dominated solutions by the optimization algorithm and the true Front which is defined as:

where, a finite number of the non-dominated solutions that approximates the true Pareto Front is called as

P, the optimal non-dominated solution archive obtained by the evolutionary algorithms is termed as

S. |

P| is the number of the non-dominated solutions in the Pareto Front,

,

∈

P and

q=2,

di is the minimum Euclidean distance between the solution

∈

S and the solutions

∈

P. In particular, the smaller value of IGD means that the non-dominated in the archive is closer to the true Pareto Front.

IGD performs the near similar calculation as done by GD. The difference is that GD the distance of each solution in optimal solutions to Pareto Front, while IGD calculates the distance of each solution in Pareto Front to optimal solutions. In this indicator, both convergence and diversity are taken into consideration. A lower value of IGD implies that the algorithm has better performance.

The hypervolume (HV) metric: HV is another popular convergence –diversity metric to evaluate the volume of the non-dominated solutions in the archive with respect to the reference set.

where,

R is the reference set,

∈

S, a hypercube

vi is formed by the reference set and the solution

as the diagonal corners of the hypercube. When the non-dominated solutions in the archive is closer to the Pareto Front, a larger HV can demonstrate solutions in the archive are more uniformly distributed in the objective space.

In order to assess the performance among different compared algorithms, two performance measures, i.e., IGD and HV were adopted here. It is believed that these two performance indicators can not only account for convergence, but also the distribution of final solutions.

-

b)

Adjusting the population size

Leong

et al. presented a dynamic population multiple-swarm MOPSO algorithm to improve the diversity within each swarm, which including the integration of a dynamic population strategy and an adaptive local archives. The experimental results indicated that the proposed MOPSO algorithm shows competitive results with improved diversity and convergence and demands less computational cost [

36].

In actual industrial problems, there are various many-objective problems (MaOP) and optimization algorithms aimed at searching for a set of uniformly distributed solutions which are closely approximating the Pareto Front. In [

32], Carvalho

et al. proposed a many objective technique named control of dominance area of solutions (CDAS) which is used on three different many objective particle swarm optimization algorithms. Most previous studies only deal with rank-based algorithms, the proposed CDAS technique to MOPSO algorithm that are based on the cooperation of particles, instead of a competitive method. Wang

et al. proposed a hybrid evolutionary algorithm by the MOEA and MOPSO to balance the exploitation and exploration of the particles. The whole population is divided into several sub-populations to solve the scalar sub-problems from a MOP [

52]. The comprehensive experiments with respect to IGD metric and HV metric can indicate that the performance of the proposed method is better than other comparable MOEAs.

-

c)

Increasing the diversity of the non-dominated solutions in the archive

In general, MOPSO algorithm will be scale poorly when the number of the objectives more than three. To solve this problem, Britto

et al. proposed a novel archiving MOPSO algorithm to explore more regions of the Pareto Front which applying the reference point to update the archive [

33]. The empirical analysis of the proposed MOPSO algorithm that verified the distribution of the solutions and experimental results presented that the solutions generated by this algorithms could be very close to the reference point.

-

d)

The inertia weight adjustment mechanisms improved the global exploration ability

Sorkhabi

et al. presented an efficient approach to constraint handling in MOPSO, and the whole population is divided into two non-overlapping populations which including the infeasible particles and feasible particles. Meanwhile, the leader is selected from the feasible population. The experimental results demonstrated that the proposed algorithm is highly competitive in solving the MOPs. Meza

et al. proposed a multiobjective vortex particle swarm optimization (MOVPSO) based on the emulation of the particles. The qualitative results show that MOVPSO algorithm can have a better performance compared to traditional MOPSO algorithm [

56]. Zhang

et al. proposed a competitive MOPSO, where the particles are updated on the basis of the pairwise competitions performed in the current swarm at each generation. Experimental results demonstrate the promising performance of the proposed algorithm in terms of both optimization quality and convergence speed [

57]. Lin

et al. proposed a MOPSO with multiple search strategies (MMOPSO) to tackle complex MOPs, where decomposition approach is exploited for transforming the MOPs. Two search strategies are used to update the velocity and position of each particle [

60].

The factors that affect the IGD and HV metrics in MOPSO:

1) Changing the storage form of the non dominated solution in the knowledge base, 2) Adjusting the flight parameters of the particle, 3) Increasing the mutation of the particle;, 4) Adjusting the population size adaptively. In order to improve the diversity and convergence of MOPSO, a MOPSO with dynamic population size is used to improve the diversity of each group, including a dynamic population strategy and an integration of an adaptive local archive, which can improve the diversity and convergence.

VI. Conclusion

In conclusion, the MOPSO algorithm has emerged as a potent tool for handling complex multi-objective optimization problems within a competitive-cooperative framework. This review paper has provided a comprehensive survey of MOPSO, encompassing its basic principles, key parameters, advanced methods, theoretical analyses, and performance metrics. The analysis of parameters influencing convergence and diversity performance has offered insights into the searching behavior of particles in MOPSO. The discussion on advanced MOPSO methods has highlighted various strategies to enhance the algorithm's efficiency, such as selecting proper gBest and pBest solutions, employing hybrid approaches with other intelligent algorithms, and adjusting population sizes dynamically. The theoretical analysis section has delved into convergence and timing complexity of MOPSO, shedding light on its mathematical foundations and practical implications.

Despite the significant progress in MOPSO research over the last two decades, several potential future research directions have been identified. These include exploring the application of MOPSO in complex dynamic processes, addressing the many-objective large-scale optimization challenges, providing more theoretical guarantees, and overcoming stagnation issues in particle evolution. In particular, there is a need for unified parameter adjustment methods, self-organization capabilities, and real-world applications of MOPSO to further solidify its position as a leading algorithm in multi-objective optimization.

Overall, this review paper has aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of MOPSO's developments, achievements, and future directions, fostering further research and advancements in this promising field.