1. Introduction

Infectious diseases, both emerging and recurring, continue to evolve and pose a global threat [

1]. Despite the significant reduction in mortality due to antibiotics, their effectiveness is diminishing because of rising microbial resistance. Prolonged antibiotic use promotes the development of drug-resistance pathogens, as bacteria have the genetic capability to pass on resistance traits. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified antibiotic resistance as a major threat to public health [

2,

3]. The emergence of multi-drug-resistant bacteria necessitates costly second- and third-line treatments, which exacerbate healthcare expenses and public health challenges. This has spurred interest in finding alternative treatments (2). Plants have long been a source of natural compounds with preventive and/or therapeutic properties. They have been used for medicinal purposes in both Eastern and Western cultures for centuries [

4]. Traditional medicine has depended on the diverse phytochemical profiles of plants for their therapeutic potential. Over the last two decades, plant-based research has led to the discovery of bioactive compounds with remarkable antimicrobial properties [

5,

6]. Therefore, screening plant extracts and their phytochemicals for antimicrobial activities is vital for discovering effective, less toxic alternative to combat multidrug-resistant infections.

Loropetalum chinense var. rubrum (L. chinense), or

Chinese fringe flower or

strap flower, is a colorful ornamental shrub from the Hamamelidaceous (witch-hazel) family, native to China, Japan, and Southeast Asia.

L. chinense, a variety of

Loropetalum chinense, is widely used in horticulture and has demonstrated medicinal potential through its phytochemical components, such as flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, and phenols [

6,

7]. Traditionally, its leaves, flowers, and roots have been used in Chinese medicine to treat conditions like cough, bruises, burns, diarrhea, and traumatic and uterine bleeding [

6,

8]. Studies have also indicated that its crude extract accelerates wound healing in rats, promoting cell regeneration and blood vessel formation [

9]. The medicinal value of

Loropetalum species is attributed to their phytochemical composition and broader biological properties.

L. chinense is rich in anthocyanins, flavonoids, and tannins, which possess potent antibacterial properties, making it a promising candidate for developing antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory drugs [

8,

10]. Despite its therapeutic potential, there is limited research on its antimicrobial effectiveness. Given its rich bioactive phytochemicals,

L. chinense could provide valuable antimicrobial alternative against resistant human pathogens. Establishing a scientific basis for the plant extract's biological properties and therapeutic application is essential. This study aims to identify the phytochemicals in

L. chinense extracts and evaluate their antibacterial activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative pathogenic bacteria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The materials for extract preparation include water, chloroform, methanol, cheesecloth, a Whatman filter, and a glass beaker. For phytochemical screening, reagents such as iodine, mercuric chloride, potassium iodide, 5% potassium hydroxide (KOH), benedict’s reagent, aqueous sodium hydroxide (aq. NaOH), glacial acetic acid, 5% ferric chloride, concentrated sulphuric acid (conc. H2SO4), concentrated hydrochloric acid (conc. HCL), millon’s reagent, ninhydrin, acetone, conc. nitric acid, 10% lead acetate solution, zinc dust, potassium dichromate solution, gelatin, 10% sodium chloride (10% NaCl), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), chloroform, acetic anhydride, 1% HCL, diluted hydrochloric acid (dil. HCL). Bacterial culturing was performed using Mueller-Hilton (MH) agar, petri dishes, and a Bunsen burner in a closed hood. Amikacin 30 μg was used as a positive control for gram-negative bacteria, and Vancomycin 5 μg was used for gram-positive bacteria as a positive control. 0.1% Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used as a negative control for gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. All the chemicals used were purchased from VWR.

2.2. Plant Identification and Collection

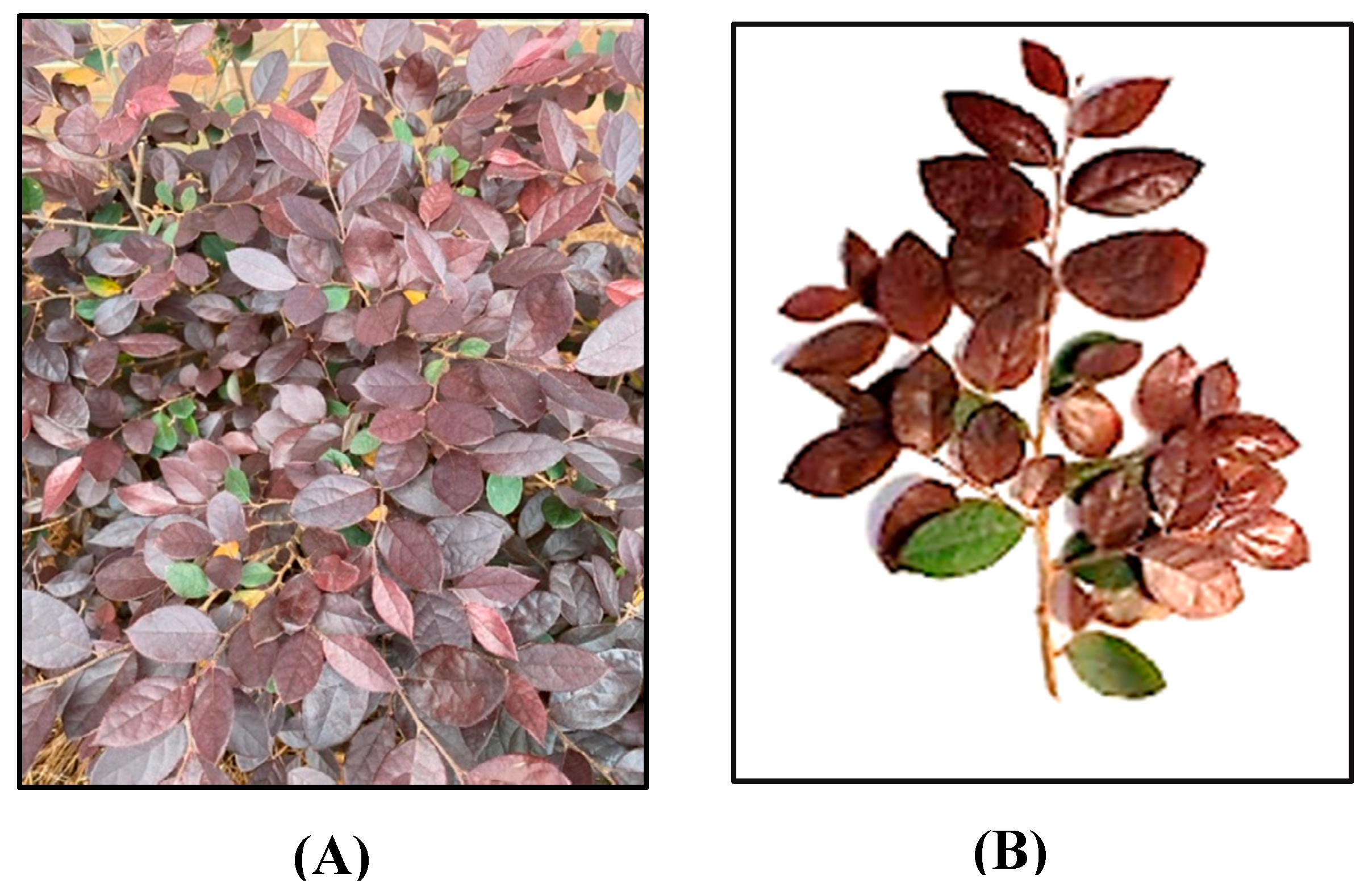

The branches and leaves of

Loropetalum chinense var. rubrum were collected on June 12, 2023, from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana (

Figure 1). The collection followed all national and international guidelines. The plant was identified and authenticated by Dr. Mary Beals, a plant biologist from Southern University and A&M College, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

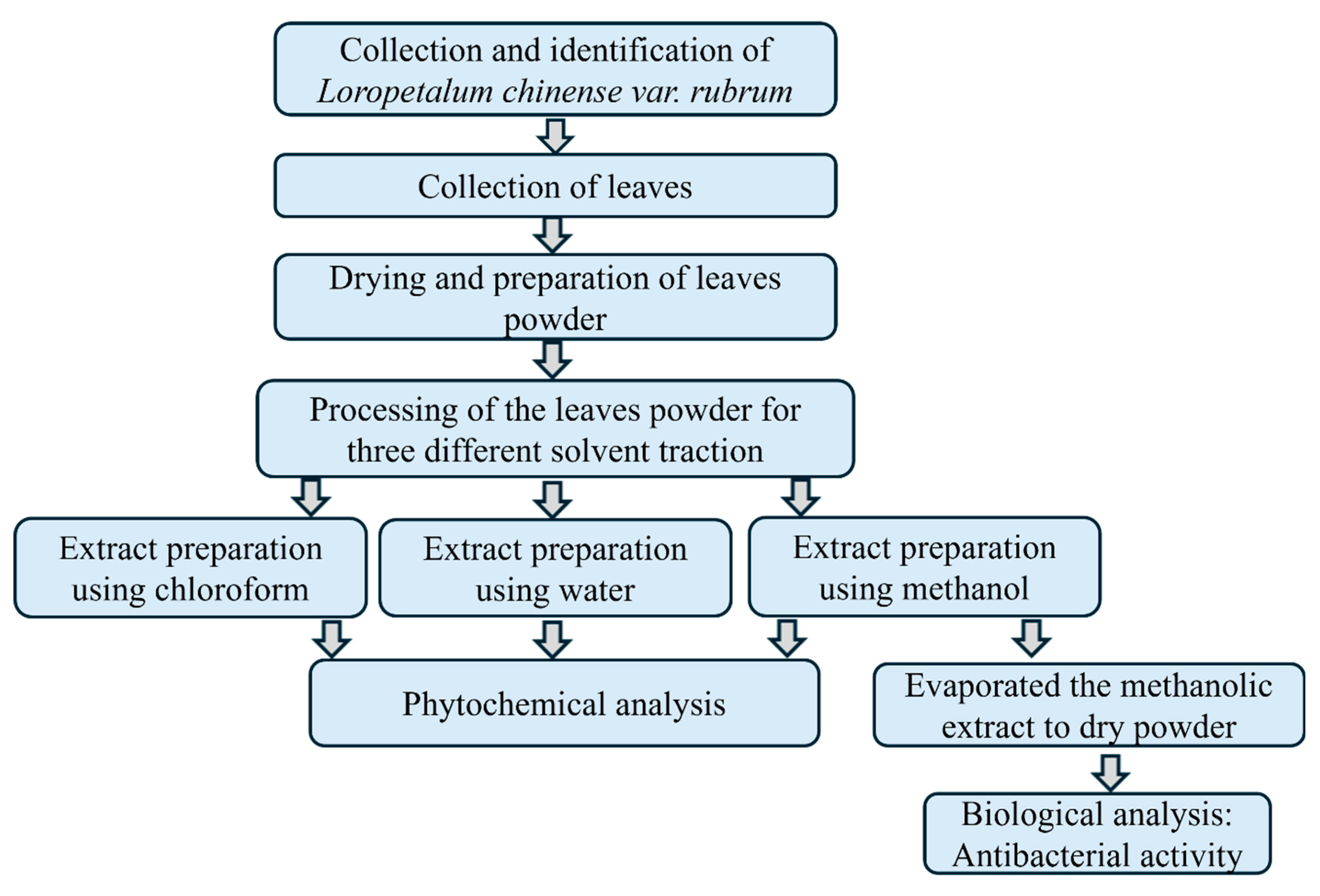

2.3. Processing and Extraction of Plant Material

The collected leaves of

L. chinense were washed thoroughly under running tap water and shade-dried for about 15-20 days. Once completely dry, the leaves were ground into powder using an electric blender. Ten (10) grams of powders were placed soaked into three clean separate conical flasks, each containing 100 ml of water, chloroform, or methanol for extraction. The flasks were sealed and rotary shaken for 24 hours. The mixtures were filtered through cheesecloth, by Whatman filter paper. The filtrates were then evaporated into a sticky mass on a hotplate at 30-40°C and concentrated to dryness in an incubator at 25°C for 24 hours. The dried powder was collected, weighed, and stored for further analysis (

Figure 2).

2.4. Phytochemical Analysis

The crude extracts from water, chloroform, and methanol as solvents, were tested for various phytoconstituents using standard methods.

2.4.1. Detection of Alkaloids and Carbohydrates

The iodine test and Mayer’s test were performed to detect alkaloids. For the iodine test, 3ml of plant extract was mixed with 5 drops of iodine solution, resulting in a blue color, which disappeared upon boiling and reappeared upon cooling, indicating a positive result [

11,

12]. In Mayer’s test, 1 ml of plant extract was combined with 2 ml of Mayer’s reagent (a mixture of mercuric chloride and potassium iodide in water). A creamy white or yellow precipitate formed, confirming the presence of alkaloids [

13,

14,

15]. For carbohydrate test, a the 5% KOH test was used, and performed by mixing 1 ml of plant extract and 5 ml of 5% KOH solution in a test tube, and where a canary-colored solution indicated a positive result [

16,

17].

2.4.2. Test for Reducing Sugars and Detection of Glycosides and Cardiac Glycosides

Benedict’s test was performed by adding 0.5 ml of Benedict’s reagent to 0.5 ml plant extract and boiling for 2 minutes. A green, yellow, or red precipitate indicated a positive result [

13].

For glycosides detection,

the aqueous NaOH test was conducted by adding 1 ml of plant extract to 1 ml of aqueous NaOH, resulting in a yellow color, confirming the presence of glycosides [

18,

19]. For

cardiac glycosides detection, the Keller-Killani test was performed by adding 1.5 ml of glacial acetic acid and 1 drop of 5% ferric chloride to 1 ml of plant extract. 1-2 drops of concentrated H

2SO

4 were added along the side of the tube. A blue color in the acetic acid layer indicated a positive result [

14,

20].

2.4.3. Test for Proteins and Amino Acids

Millon’s test, Ninhydrin test, and Xanthoproteic test were performed. For Millon's test, a few drops of Millon’s reagent were added to 2 ml of plant extract in a test tube, which resulted in a white precipitate as a positive finding for proteins. For the Ninhydrin test, 2 drops of Ninhydrin solution were added to the 2 ml of plant extract, which gave a purple-colored solution. In the Xanthoproteic test, 1 ml of nitric acid was added to 3 ml of plant extract, which gave a colored solution a positive finding for the presence of proteins [

21,

22].

2.4.4. Detection of Flavonoids, Phenols, Tannins, Phlobatannins, Cholesterol, Terpenoids and Quinone.

The Alkaline reagent test and zinc-hydrochloride reduction test were performed to detect flavonoids. In the alkaline reagent test, 1 ml of plant extract was mixed with 2 ml of 2% NaOH solution, which turned yellow and became colorless after adding 2 drops of dilute HCL, indicating the presence of flavonoids [

14,

16,

23]. In the lead acetate test, 1 ml of plant extract was treated with 0.5 ml of lead acetate, resulting in a yellow precipitate, confirming flavonoids [

24]. The zinc-hydrochloride reduction test involved adding a pinch of zinc dust to 1 ml of plant extract and concentrated HCL, producing a magenta color as a positive result [

25,

26].

For the detection of phenol, the ferric chloride and iodine tests were performed. In the ferric chloride test, 2 ml of plant extract and 1 ml of 5% ferric chloride solution formed a dark green/bluish-black color, indicating the presence of phenols[

27]. In the iodine test, 1-2 drops of diluted iodine solution were added to 2-3 ml of plant extract, resulting in a transient red color as a positive finding for phenolic compounds [

14,

25].

For the detection of tannins, the gelatin and 10% NaOH tests were used. In the gelatin test, the plant extract was mixed with 1% gelatin solution containing sodium chloride, forming a white precipitate to confirm tannins [

28]. In the 10% NaOH test, 400 μL of plant extract was treated with 4 ml of 10% NaOH, forming an emulsion, indicating tannins [

14].

For the detection of phlobatannins

, the HCL test was used to detect the presence of phlobatannins. In this test, 2 ml of plant extract was treated with 2 ml of 1% HCl and boiled. The formation of a red precipitate confirmed the presence of phlobatannins [

29].

For cholesterol, the test involved adding 2 ml of plant extract, 2 ml of chloroform, 10 drops of acetic anhydride, and 2-3 drops of concentrated H

2SO

4 to a test tube. A red rose color indicated the presence of cholesterol [

18].

For terpenoids, a chloroform test was performed. The chloroform test for terpenoids involved mixing 5 ml of plant extract, evaporating on a water bath, and adding 3 ml of concentrated H

2SO

4. A grey-colored solution indicated the presence of terpenoids [

23].

For detection of quinones, the concentrated HCL test was performed. The appearance of green-colored solution confirmed the presence of quinones [

30].

2.5. Test Microorganisms

The microorganisms used in this experiment were standard reference strains obtained from the Department of Biological Sciences and Chemistry at Southern University and A&M College in Baton Rouge

, Louisiana, USA. The streak plate method was used to isolate colonies, and purity was confirmed through the Gram stain technique [

31] (

Table 1). The strains used were:

Bacillus subtilis ATCC™ 1174™,

Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus ATCC™ 33591™,

Escherichia coli ATCC™ 35218™,

Enterobacter aerogenes ATCC™ 13048™, and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC™ 27853™. Antibiotic and culture media were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fisher Scientific, USA).

2.6. Preparation of Test Samples for Antibacterial Activity

Test samples of the dried methanolic plant extract were dissolved in DMSO. Serial dilutions were performed, and concentrations of 6.25 mg/ml, 12.5 mg/ml, 25.0 mg/ml, and 50.0 mg/ml were prepared.

2.7. Disc Diffusion Assay

The plant extract's antibacterial activity was determined using the Kirby-Bauer agar diffusion assay. For the experiment, 10 sterile petri plates were made with trypticase soy gar under aseptic conditions. We inoculated the bacterial suspension, adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard, on the trypticase soy agar plates and spread it evenly with a sterile swab. The petri plates were divided into four sections, one for positive control, one for negative control, and two for the test samples, and labeled accordingly. The standard drugs AN30 and VA5 were used as a positive control for gram-negative and gram-positive strains, respectively, while 0.1 % DMSO was used as a negative control for all tested strains. The Whatman filter paper was cut into small round discs and autoclaved for 15 minutes to make them sterile. The sterile discs were placed on the agar surface of the plate and were impregnated with 10 μl/disc of positive control, negative control, and test samples of different concentrations. The plates were incubated at 37°C in an incubator for 24 hours and then examined for the diameter of the zone of bacterial growth inhibition using a ruler. The zone of bacterial growth inhibition was compared with the positive control, and the experiment was repeated three times for validation [

32,

33,

34].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD). Statistical analysis was conducted using Graph Pad Prism 10 to perform a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. This was used to compare the antibacterial activities of different extract concentrations against each test bacteriium and controls. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Phytochemical Analysis

L. chinense leaf extracts were screened for active constituents and secondary metabolites. We performed different phytochemical tests using the standard procedures that were designed. Our qualitative phytochemical analysis shows that methanolic extracts yield more phytoconstituents than aqueous and chloroform extracts. The results of the phytochemical screening test are shown in

Table 2.

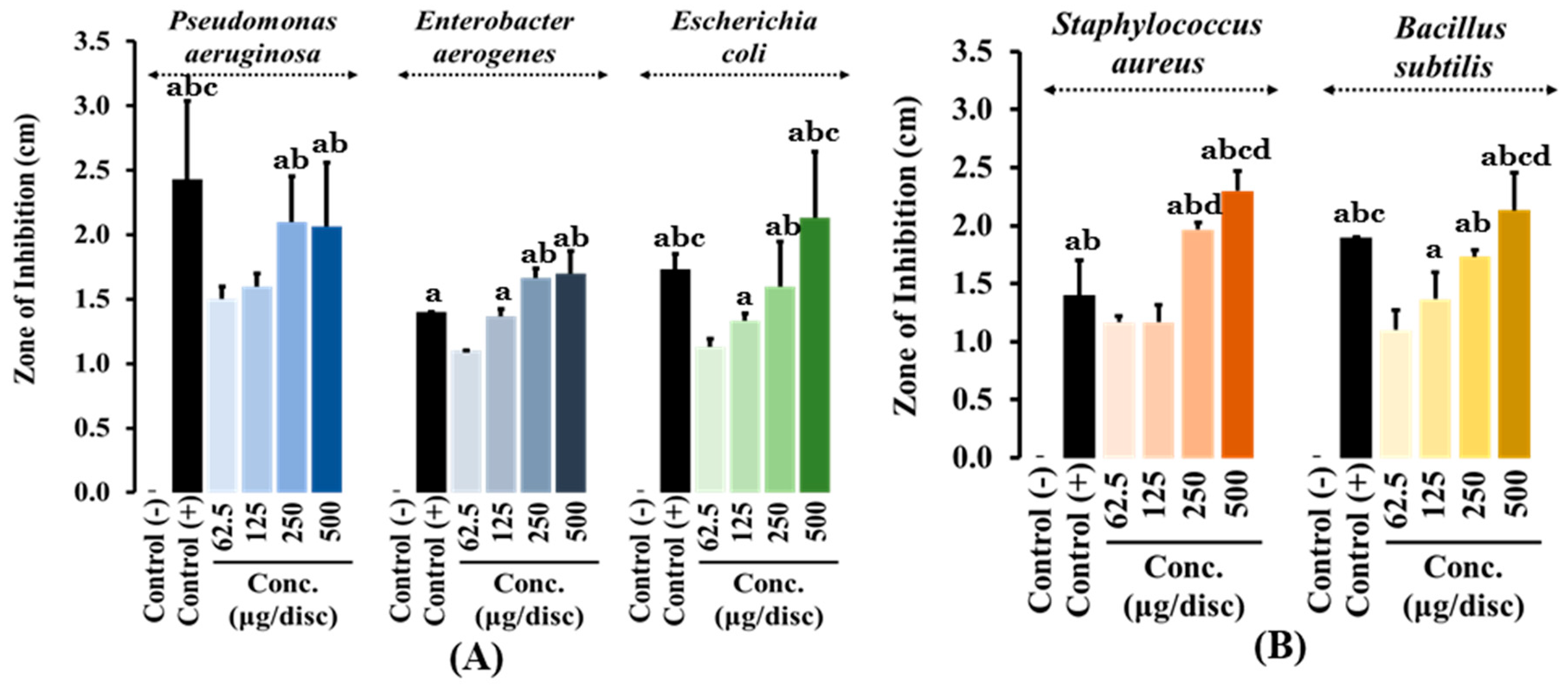

3.2. Disc Diffusion Assay

The antibacterial activity of crude methanolic extract of

L. chinense leaves was tested against different bacterial strains using the disc diffusion assay. Bacterial growth inhibition was observed among all the tested strains, even at low extract concentrations of 62.5 μg/disc. Among gram-negative bacteria,

Enterobacter aerogenes were the most susceptible to the methanolic extract at a concentration of 500 μg/disc, followed by

E. coli and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Similarly, for the gram-positive bacterium

S. aureus, the methanolic extract exhibited significantly effective antibacterial activity at a concentration of 500 μg/disc compared to the standard antibiotic used as a positive control, followed by

Bacillus subtilis (

Table 3 and

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

Multi-drug resistance continues to pose a significant challenge to healthcare and biomedical researchers globally. As bacteria become more resistant to overuse and misuse of existing antibiotics, routine bacterial infections may become life-threatening [

35]. Medicinal plants, with their rich array of bioactive compounds, have attracted increasing attention for their potential health benefits. These plants, offering a complex mixture of metabolites, have long been valued for their medicinal properties, often effectively combating microbial infections with minimal side effects [

11,

36]. This study evaluates the antibacterial activity of

L. chinense leaf extract against pathogenic bacteria. Known for its significance in Chinese folk medicine,

Loropetalum chinense contains several phytochemicals such as phytochemicals, flavonoids, anthocyanin, tannins, and other phenolic compounds with antimicrobial properties. However, the plant's chemical composition may vary depending on factors like species, plant parts, and environmental conditions [

6,

37].

In this study, qualitative phytochemical tests were performed on aqueous, chloroform, and methanolic extracts of L. chinense leaves. The results indicated that methanol is more effective than water and chloroform as a solvent for extracting bioactive compounds, as most of the phytoconstituents were found in the methanolic extracts. The phytochemical analysis identified alkaloids, carbohydrates, reducing sugars, glycosides, cardiac glycosides, proteins and amino acids, phenols, flavonoids, tannins, cholesterol, terpenoids and quinones, while phlobatannins were absent. The presence of these bioactive compounds may contribute to the antibacterial properties of L. chinense leaves.

The antibacterial activity of

L. chinense leaf crude methanolic extract was tested using the disc diffusion assay. The extract inhibited the growth of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria at concentration as low as of 62.5 μg/disc, as evidenced by the zone of inhibition. However, the methanolic extract showed stronger antibacterial activity against gram-positive bacteria compared to gram-negative bacteria. Notably, the extract was particularly effective against

S. aureus, with a stronger inhibition at 250 μg/disc than the standard antibiotic, Vancomycin. This suggests that S

. aureus is more susceptible to

L. chinense methanolic extract, indicating its potential as an antimicrobial agent for treating infections caused by this bacterium [

38]. Among gram-negative bacteria,

Enterobacter aerogenes was the most susceptible. This bacterium is an opportunistic multi-resistant pathogen often found in nosocomial infection [

39]. At 500 μg/disc, the extract exhibited greater antibacterial activity against

Enterobacter aerogenes than the standard antibiotic, Amikacin.

While the broad-spectrum antibacterial activity of

L. chinense leaf extracts suggests its potential as a source of novel antibacterial agents, there are some limitations. We did not determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) or minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of the crude methanolic extract. The MIC and MBC are crucial for understanding bacterial susceptibility and the drug's ability to kill microbes [

40]. Additionally, the study involved a limited sample size of commonly encountered gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Further studies should include a broader range of pathogens for a more comprehensive evaluation of the extract’s antibacterial efficacy. Further research is also needed to isolate and identify individual bioactive compounds for further 2D and 3D organoids as well as

in vivo testing and toxicity studies.

5. Conclusion

Phytochemical analysis of aqueous, chloroform, and methanolic extracts of L. chinense leaves revealed the presence of various bioactive compounds. The methanolic extract exhibited significant antibacterial activity against all bacterial strains tested. Among the pathogens studied, Staphylococcus aureus was the most sensitive gram-positive bacterium, while Enterobacter aerogenes was the most sensitive gram-negative bacterium, as indicated by the zone of inhibition in the disc diffusion assay. Overall, L. chinense leaf extract demonstrates broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, supporting its potential as a source for new clinically effective and affordable plant-derived antibacterial drugs. Future research, including MIC and related studies, is recommended to further explore the antimicrobial properties of L. chinense.

Author Contributions

E.H. conceived, designed and supervised the research; K.C.T. performed experiments; K.C.T. and S.K. analyzed data; E.H. and K.C.T. interpreted the experimental results; E.H., K.C.T., and S.K. prepared figures; E.H., K.C.T., and S.K. drafted the manuscript; A.A., M.B., O.D., R.R., and E.H. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the NSF-HBCU-EiR Grant number: 2200607 to R.R.; E.H. laboratory is partially supported by a pilot research award from an NIH/NIGMS IDeA Louisiana Biomedical Research Network (LBRN) grant number P20GM103424, and a Southern University Research and Enhancement Development (RED) grant number REDG2122-RR. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Masomeh Fatemi for her technical assistance, and Drs. Bryan T. Rogers, and Jean Christopher Chamcheu for their assistance in critically editing this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fauci, A.S., Infectious diseases: considerations for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis, 2001. 32(5): p. 675-85. [CrossRef]

- Zaręba, P., et al., New cyclic arylguanidine scaffolds as a platform for development of antimicrobial and antiviral agents. Bioorg Chem, 2023. 139: p. 106730. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.L., Epidemiology of drug resistance: implications for a post-antimicrobial era. Science, 1992. 257(5073): p. 1050-5.

- Gossell-Williams, M., R. Simon, and M. West, The past and present use of plants for medicines. West Indian Med J, 2006. 55(4): p. 217-218. [CrossRef]

- Salmerón-Manzano, E., J.A. Garrido-Cardenas, and F. Manzano-Agugliaro, Worldwide research trends on medicinal plants. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2020. 17(10): p. 3376.

- Wu, W., et al., Review of Loropetalum chinense as an industrial, aesthetic, and genetic resource in China. HortScience, 2021. 56(10): p. 1148-1153. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., et al., Phytochemical and chemotaxonomic study on Loropetalum chinense (R. Br.) Oliv. Biochemical systematics and ecology, 2018. 81: p. 80-82. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., et al., Transcriptomic and metabolomic profiling provides insights into flavonoid biosynthesis and flower coloring in Loropetalum chinense and Loropetalum chinense var. rubrum. Agronomy, 2023. 13(5): p. 1296. [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.Q., et al., Preliminary study on the material basis of Loropetalum chinense in promoting skin wound healing in rats. China J. Chinese Materia Medica, 2013. 38(2): p. 3566-3570.

- Zhang, X., et al., Transcriptome Analysis and Metabolic Profiling of Anthocyanins Accumulation in Loropetalum Chinense var. Rubrum With Different Colors of Leaf. 2022, Research Square.

- Bhatt, S. and S. Dhyani, Preliminary phytochemical screening of Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. International Journal of Current Pharmaceutical Research, 2012. 4(1): p. 87-89.

- Shalaby, E.A., et al., Chemical constituents and biological activities of different extracts from ginger plant (Zingiber officinale). Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture, 2023. 10(1): p. 14.

- Raaman, N., Phytochemical techniques. 2006: New India Publishing.

- Singh, V. and R. Kumar, Study of phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Allium sativum of Bundelkhand region. International Journal of Life-Sciences Scientific Research, 2017. 3(6): p. 1451-1458. [CrossRef]

- Sukumar, B.S., T. Tripathy, and H. Shashirekha, Phyto physico-chemical profile of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera Dunal). Journal of Ayurveda and Integrated Medical Sciences, 2020. 5(06): p. 120-129.

- Audu, S.A., I. Mohammed, and H.A. Kaita, Phytochemical screening of the leaves of Lophira lanceolata (Ochanaceae). Life Science Journal, 2007. 4(4): p. 75-79.

- Kalita, M., et al., Ethnobotanical survey and preliminary phytochemical screening of Posa kumura: An uncharted ethnic food of Assam. Ethnobot. Res. Appl, 2023. 26: p. 19-141.

- Jagessar, R., Phytochemical screening and chromatographic profile of the ethanolic and aqueous extract of Passiflora edulis and Vicia faba L.(Fabaceae). Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 2017. 6(6): p. 1714-1721.

- Ray, S., S. Chatterjee, and C.S. Chakrabarti, Antiprolifertive activity of allelochemicals present in aqueous extract of Synedrella nodiflora (L.) Gaertn. in apical meristems and Wistar rat bone marrow cells. IOSR Journal of Pharmacy, 2013. 3(2): p. 1-10.

- Bhatt, S. and S. Dhyani, Preliminary phytochemical screening of Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. Int J Curr Pharm Res, 2012. 4(1): p. 87-89.

- De Silva, G.O., A.T. Abeysundara, and M.M.W. Aponso, Extraction methods, qualitative and quantitative techniques for screening of phytochemicals from plants. American Journal of Essential Oils and Natural Products, 2017. 5(2): p. 29-32.

- Narasimhan, R. and A. Mohan, Phytochemical screening of Sesamum indicum seed extract. World journal of pharmacy and pharmaceutical sciences, 2012. 1(4): p. 1298-1308.

- Gul, R., et al., Preliminary phytochemical screening, quantitative analysis of alkaloids, and antioxidant activity of crude plant extracts from Ephedra intermedia indigenous to Balochistan. The Scientific World Journal, 2017. 2017.

- Shah, R., P. Sharma, and N. Modi, Preliminary phytochemical analysis and assessment of total phenol and total flavonoid content of Haworthiopsis limifolia Marloth. and its antioxidant potential. International Journal of Botany Studies, 2021. 6(3): p. 902-909.

- Vimalkumar, C., et al., Comparative preliminary phytochemical analysis of ethanolic extracts of leaves of Olea dioica Roxb., infected with the rust fungus Zaghouania oleae (EJ Butler) Cummins and non-infected plants. Journal of Pharmacognosy and phytochemistry, 2014. 3(4): p. 69-72.

- Joshi, B., D. Pandya, and A. Mankad, Comparative study of phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of Curcuma longa (L.) and Curcuma aromatica (Salib.). J. Med. Plants, 2018. 6: p. 145-148.

- Nanna, R.S., et al., Evaluation of phytochemicals and fluorescent analysis of seed and leaf extracts of Cajanus cajan L. International journal of pharmaceutical sciences Review and Research, 2013. 22(1): p. 11-18.

- Pandey, A. and S. Tripathi, Concept of standardization, extraction and pre phytochemical screening strategies for herbal drug. Journal of Pharmacognosy and phytochemistry, 2014. 2(5): p. 115-119.

- Shaikh, J.R. and M. Patil, Qualitative tests for preliminary phytochemical screening: An overview. International Journal of Chemical Studies, 2020. 8(2): p. 603-608. [CrossRef]

- Basumatary, A.R., Preliminary phytochemical screening of some compounds from plant stem bark extracts of Tabernaemontana divaricata Linn. used by Bodo Community at Kokrajhar District, Assam, India. Archives of Applied Science Research, 2016. 8(8): p. 47-52.

- Telles, C., et al., The antimicrobial property of the acetone extract of Cola acuminata. Open Access J Toxicol, 2019. 4(2): p. 555631.

- Favaretto, A., et al., Antimicrobial activity of leaf and root extracts of tough lovegrass. Comunicata Scientiae, 2016. 7(4): p. 420-427. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A., et al., Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. American journal of clinical pathology, 1966. 45(4_ts): p. 493-496.

- Hudzicki, J., Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion susceptibility test protocol. American society for microbiology, 2009. 15(1): p. 1-23.

- Stephens, L.J., et al., Antimicrobial innovation: a current update and perspective on the antibiotic drug development pipeline. Future Medicinal Chemistry, 2020. 12(22): p. 2035-2065.

- Khosravi, A.D. and A. Behzadi, Evaluation of the antibacterial activity of the seed hull of Quercus brantii on some gram negative bacteria. Pak J Med Sci, 2006. 22(4): p. 429-32.

- Zhang, Y., et al., Phenotypic, Physiological, and Molecular Response of Loropetalum chinense var. rubrum under Different Light Quality Treatments Based on Leaf Color Changes. Plants (Basel), 2023. 12(11).

- Wasihun, Y., H. Alekaw Habteweld, and K. Dires Ayenew, Antibacterial activity and phytochemical components of leaf extract of Calpurnia aurea. Scientific reports, 2023. 13(1): p. 9767.

- Davin-Regli, A. and J.-M. Pagès, Enterobacter aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae; versatile bacterial pathogens confronting antibiotic treatment. Frontiers in microbiology, 2015. 6: p. 392.

- Owuama, C.I., Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) using a novel dilution tube method. African journal of microbiology research, 2017. 11(23): p. 977-980.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).