1. Introduction

Aural toilet using microsuction is a commonly performed procedure in ENT outpatient clinics [

1]. With the aid of microscope or otoendoscope, aural microsuction effectively and safely removes purulent discharge, foreign bodies, or ear wax [

2]. Despite its advantages, patients may experience discomfort, such as pain or tension, and various forms of dizziness, including rotatory vertigo or presyncope. Previous studies reported that vertigo is a frequent complaint during aural microsuction [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In some patients, microsuction-induced vertigo is so severe that the procedure cannot continue. Cooling of the middle ear cavity during microsuction has been suggested as the underlying cause of vertigo [

4,

8,

10].

While microsuction-induced vertigo has been reported since early 1900s and is frequently encountered in clinics, there have been no reports on the characteristics of nystagmus observed during these occurrences. This study investigates the characteristics of microsuction-induced nystagmus and the incidence of microsuction-induced vertigo or nystagmus based on the appearance of the tympanic membrane (TM).

2. Materials and Methods

The patients who underwent aural toilet using microsuction at our clinic between March 2022 and August 2024 were included in this study. Otoendoscopic examination was used to determine the need for microsuction, and nystagmus was observed using video Frenzel glasses. Patients required microsuction for various reasons, such as wet debris, purulent discharge, ear wax, or foreign body removal. A total of 85 patients (39 men and 46 women; mean age 58 ± 17 years) were enrolled. Patients were asked if they experienced rotatory vertigo during and after microsuction. Since the feeling of dizziness is a subjective symptom that can include various sensations such as lightheadedness, a sense of disorientation, imbalance or unsteadiness, and an illusory sensation of motion of either the self or the surroundings [

13], patients were carefully asked to distinguish whether their dizziness was vertigo or another form of nonspecific dizziness. Those with congenital nystagmus, medication affecting nystagmus or dizziness, or a history of vestibulopathy were excluded. Neurological examinations revealed no deficits, and spontaneous nystagmus before microsuction was another exclusion criterion.

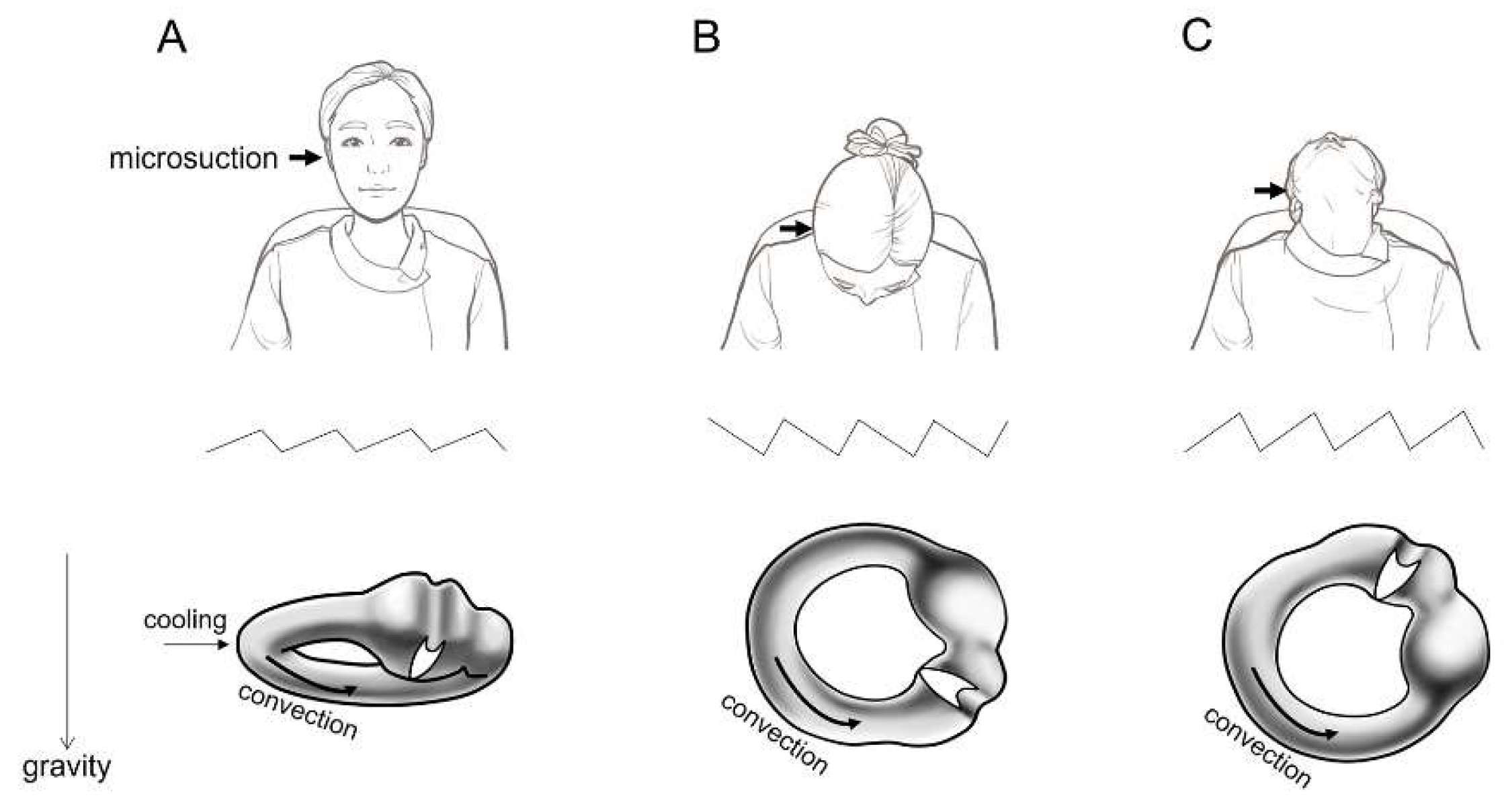

Under an operating microscope, an ear speculum was inserted into the external auditory canal (EAC), and microsuction was performed (Supplemental video 1). The procedure lasted between 20 and 40 seconds, depending on patient tolerance. Nystagmus was observed during and after microsuction in a seated position. Patients then underwent a bow and lean test, where they bent their heads forward to 90˚ and tilted backward to 60˚ (Supplemental video 1,

Figure 1).

Statistical comparison was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Data Editor (Ver. 29, Armonk, New York, USA). Categorical variables were compared using χ² test, and a p value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (approval number: 2024-10-022). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

3.1. Patients and TM appearance

Between March 2022 and August 2024, a total of 85 patients were included in this study. The patients were classified based on the appearance of the TM (

Table 1). Thirty-five patients exhibited a normal eardrum appearance without TM perforation (normal TM,

n = 35), seven had previously undergone canal wall up mastoidectomy with the TM appearing near-normal without re-perforation (normal postoperative TM after canal wall up mastoidectomy,

n = 7), and eight patients had otitis media with effusion without TM perforation (otitis media with effusion,

n = 8). There were 25 patients with TM perforation, of which 14 had chronic suppurative otitis media (chronic suppurative otitis media,

n = 14), five had cholesteatoma with or without labyrinthine fistula (middle ear cholesteatoma with/without labyrinthine fistula,

n = 5), and six had a ventilation tube inserted (ventilation tube in situ,

n = 6). Additionally, six patients had no TM perforation but a history of open cavity mastoidectomy (TM without perforation after open cavity mastoidectomy,

n = 6), and four had adhesive otitis media (adhesive otitis media,

n = 4) (

Table 1).

3.2. Microsuction-induced nystagmus and vertigo

We investigated the proportion of patients who exhibited nystagmus or complained of vertigo during aural microsuction based on TM appearance. Nystagmus was observed during and after aural microsuction while the patients were seated, and 95% (81 of 85) exhibited microsuction-induced nystagmus (

Table 1). The nystagmus was directed toward the contralateral ear (

Figure 1A; Supplemental video 1). To determine if the mechanism behind microsuction-induced nystagmus was related to the convection of cooled inner ear fluid, a bow and lean test was subsequently performed. In the bowing position, the direction of nystagmus changed toward the ipsilateral ear (

Figure 1B; Supplemental video 1). In the leaning position, the direction of nystagmus reversed and was directed toward the contralateral ear (

Figure 1C; Supplemental video 1). Despite the observation that 95% (81 of 85) of patients undergoing microsuction exhibited nystagmus, only 36% (31 of 85) reported experiencing rotatory vertigo (

Table 1). Among those who did not report vertigo, none complained of nonspecific dizziness.

Next, we explored whether the proportion of patients who exhibited microsuction-induced nystagmus or complained of vertigo differed according to TM appearance. The results are summarized in

Table 1. The TM appearance was classified into four groups. (1) No TM perforation group (

n = 50), including normal TM (

n = 35), normal postoperative TM after canal wall up mastoidectomy (

n = 7), and otitis media with effusion (

n = 8). (2) TM perforation group (

n = 25), including chronic suppurative otitis media (

n = 14), middle ear cholesteatoma with/without labyrinthine fistula (

n = 5), and ventilation tube in situ (

n = 6). (3) TM without perforation after open cavity mastoidectomy (

n = 6). (4) Adhesive otitis media (

n = 4). The proportion of patients showing nystagmus and reporting rotatory vertigo was 97% (34 of 35) and 9% (3 out of 35), respectively, in patients with normal TM; 100% (7 out of 7) and 29% (2 out of 7), respectively, in patients with normal postoperative TM after canal wall up mastoidectomy; and 63% (5 out of 8) and 0%, respectively, in patients with otitis media with effusion. Among patients with chronic suppurative otitis media, 100% (14 out of 14) showed nystagmus and 64% (9 out of 14) reported vertigo. Similarly, all patients with middle ear cholesteatoma with/without labyrinthine fistula (100%, 5 out of 5) showed both nystagmus and vertigo. For those with a ventilation tube in situ, 100% (6 out of 6) exhibited nystagmus, and 50% (3 out of 6) experienced vertigo.

For patients who had undergone open cavity mastoidectomy, 100% (6 out of 6) showed nystagmus, and 83% (5 out of 6) reported vertigo. All patients with adhesive otitis media (100%, 4 out of 4) experienced both nystagmus and vertigo (

Table 1). The proportion of patients with microsuction-induced nystagmus was not significantly different between the no TM perforation group (92%, 46 out of 50) and the groups with TM perforation, open cavity mastoidectomy, or adhesive otitis media (100%, 35 of 35) (

P = 0.087, X

2 test;

Figure 2A). However, the proportion of patients reporting rotatory vertigo was significantly higher in the groups with TM perforation, open cavity mastoidectomy, or adhesive otitis media (74%, 26 of 35) compared to the no TM perforation group (10%, 5 of 50) (

P < 0.001, X

2 test;

Figure 2B).

4. Discussion

The present study described the characteristics of nystagmus and the incidence of vertigo in 85 patients who underwent aural microsuction. While microsuction-induced nystagmus was observed in most patients regardless of TM appearance, the proportion of patients reporting vertigo varied depending on the condition of the TM.

It has long been established that a change in temperature in the EAC can cause vertigo and nystagmus [

14]. Microsuction during aural toilet lowers the temperature of the EAC and middle ear cavity, which increases the density of the endolymph in the lateral semicircular canal. This change in endolymph density causes convection, leading to excitation or inhibition of the lateral semicircular canal. In 1928, Dundas-Grant reported that suction using Siegel’s speculum produced giddiness accompanied by nystagmus, though it was not always clear [

6]. Gray and Nicolaides demonstrated that temperature drops during microsuction, measured using a thermocouple wire, were pronounced in patients experiencing vertigo, especially when suction was applied to ‘wet’ cavities. They suggested that evaporative cooling was the cause. They studied microsuction-induced vertigo in patients with mastoid cavities communicating with the EAC, finding that 80% (16 out of 20) complained of rotatory vertigo with nystagmus, with the fast phase directed toward the opposite ear. Two patients (10%) reported nonspecific dizziness without nystagmus, and two others (10%) reported no dizziness at all [

8].

In our study, microsuction-induced nystagmus was observed in 95% (81 out of 85) of patients with various TM appearances. When comparing only patients with a history of open cavity mastoidectomy, the proportion of patients with microsuction-induced nystagmus was higher in our study (100%) compared to the previous study (80%) [

8]. This difference may be explained by the use of video Frenzel glasses in our study, as opposed to naked-eye observation in the previous study. Nystagmus can be suppressed by visual fixation, which would occur in naked-eye assessments. It is noteworthy that the proportion of patients with microsuction-induced nystagmus was not significantly different between the no TM perforation group (92%, 46 out of 50) and the groups including TM perforation, open cavity mastoidectomy, and adhesive otitis media (100%, 35 out of 35) in our study. Another interesting finding was that the direction of microsuction-induced nystagmus reversed between the bowing and leaning positions. Considering the anatomy of the lateral semicircular canal in these positions (

Figure 1B and C), this supports the hypothesis that microsuction-induced nystagmus is caused by convection of the lateral semicircular canal endolymph due to the cooling effect. We believe that the cooling effect might not be strong enough to induce nystagmus in some patients with otitis media with effusion (

Table 1).

While microsuction elicited nystagmus in most patients, only some reported vertigo. A previous study reported that vertigo was experienced by 80% of patients with prior open cavity mastoidectomy during microsuction.

11 In our study, 83% (5 out of 6) of such patients reported vertigo, which is comparable to previous findings [

8]. Notably, vertigo occurred in all patients with adhesive otitis media (4 out of 4) and middle ear cholesteatoma with/without labyrinthine fistula (5 out of 5), likely due to more effective transmission of the cooling effect to the lateral semicircular canal. In contrast, vertigo was reported by only 9% of the patients with normal TM, 29% of those with normal postoperative TM after canal wall up mastoidectomy, and none of the patients with otitis media with effusion. We believe that the cooling effect was less effectively transmitted in patients with adhesive otitis media or previous open cavity mastoidectomy. Additionally, since vertigo is a subjective symptom, the same vestibular stimulus may or may not cause a patient to report vertigo, depending on their sensitivity to symptoms or individual disposition. However, because we did not assess nystagmus intensity in this study, we cannot rule out the possibility that stronger nystagmus could have caused vertigo in some patients.

The limitations of this study include: (1) It is likely that a consistent vestibular stimulus was not applied to each patient, as the position of the microsuction tip within the EAC and the duration of the procedure may have varied between patients. (2) We investigated the presence of nystagmus but not its intensity, so it remains unclear how the intensity of nystagmus is influenced by TM appearance and its correlation with vertigo symptoms.

5. Conclusions

Aural toilet using microsuction commonly induces nystagmus, caused by convection of the lateral semicircular canal endolymph due to cooling effect. Although microsuction-induced nystagmus was observed in most patients regardless of TM appearance, the percentage of patients reporting vertigo varied according to the condition of the TM. Since some patients may experience severe vertigo during microsuction, which could result in premature termination of the procedure, it is recommended that clinicians closely monitor patients for vertigo during the procedure. Further research is needed to explore methods for preventing microsuction-induced vertigo.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplemental video 1. Representative video Frenzel glasses examination. A microsuction was applied to the right ear and left-beating nystagmus was observed. Right-beating nystagmus was observed in a bowing position, and left-beating nystagmus was observed in a leaning position.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-H.K.; methodology, M.J., T.K., J.K., C.H., D.-H.L. and J.E.S.; software, M.J., T.K.; validation, J.K., C.H., D.-H.L. and C.-H.K.; formal analysis, C.H., D.-H.L.; investigation, C.-H.K., M.J., T.K., J.K., C.H., D.-H.L. and J.E.S.; resources, C.-H.K.; data curation, C.-H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-H.K.; writing—review and editing, C.-H.K.; visualization, M.J., T.K., J.K., C.H., D.-H.L. and J.E.S.; supervision, C.-H.K.; project administration, C.-H.K.; funding acquisition, C.-H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by Konkuk University in 2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Konkuk University Medical Center (No. 2024-10-022; date of approval, October 18, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because this study is a retrospective study and the study involves no more than minimal risk.

Data Availability Statement

Data in this study is available by request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by Konkuk University in 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TM |

Tympanic membrane |

| EAC |

External auditory canal |

References

- Clegg AJ, Loveman E, Gospodarevskaya E, Harris P, Bird A, Bryant J, et al. The safety and effectiveness of different methods of earwax removal: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(28):1-192. [CrossRef]

- Pothier DD, Hall C, Gillett S. A comparison of endoscopic and microscopic removal of wax: a randomised clinical trial. Clin Otolaryngol. 2006;31(5):375-80. [CrossRef]

- Addams-Williams J, Howarth A, Phillipps JJ. Microsuction aural toilet in ENT outpatients: a questionnaire to evaluate the patient experience. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267(12):1863-6. [CrossRef]

- Bende M. Warm air for prevention of vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1988;98(6 Pt 1):687. [CrossRef]

- Bhutta MF, Head K, Chong LY, Daw J, Schilder AG, Burton MJ, et al. Aural toilet (ear cleaning) for chronic suppurative otitis media. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;9(9):Cd013057.

- Dundas-Grant J. Case of Vertigo on Suction in a Patient with Adhesive Processes in the Middle Ear, following Scarlet Fever: Presumably Malleo-Incudal Ankylosis. Proc R Soc Med. 1928;21(12):1933. [CrossRef]

- Dundas-Grant J. Case of Vertigo on Suction in a Patient with absence of the Stapes. (Previously shown November 17, 1911). Proc R Soc Med. 1928;21(12):1933.

- Gray RF, Nicolaides AR. Vertigo following aural suction: can it be prevented? Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1988;13(4):285-8.

- McInerney NJ, O'Keeffe N, Mackle T. Aural microsuction: an analysis of post-procedure patient safety incidents. Ir J Med Sci. 2024;193(2):945-7.

- Nicolaides AR, Gray RF. Aural suction without vertigo. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1990;15(2):137-40.

- Prowse SJ, Mulla O. Aural microsuction for wax impaction: survey of efficacy and patient perception. J Laryngol Otol. 2014;128(7):621-5. [CrossRef]

- Sarode D, Asimakopoulos P, Sim DW, Syed MI. Aural microsuction. Bmj. 2017;357:j2908.

- Kim CH, Lee J, Choi B, Shin JE. Nystagmus in adult patients with acute otitis media or otitis media with effusion without dizziness. PLoS One. 2021;16(5):e0250357.

- Barany R. Physiologie und pathologie (funktions-prufung) des bogengang-apparates beim menschen: kliniche studien. F Deuticke. 1907.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).