Introduction

The tourism industry is one of the largest sectors of the global economy, with significant growth potential. In 2019, its contribution to global GDP was 10.3%, declining to 9.1% in 2023, but is projected to rise to 11.4% by 2034 (WTTC; Modi, 2024). Additionally, the industry plays a vital role in employment, accounting for one in every ten jobs worldwide.

The evolving nature of global tourism has intensified competition among destinations. This competitive environment is shaped by dynamic social, economic, and natural factors, as well as the emergence of new destinations in international markets. Consequently, competition conditions continue to evolve, diversifying the set of competing destinations.

In Georgia, tourism has traditionally been a key sector of the national economy and is considered a driver of sustainable development. The industry contributed 8.4% to GDP in 2019 and 7.1% in 2023 (GNTA). Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Georgia emerged as a recognized tourism destination in the international market, benefiting from increased openness and accessibility for foreign visitors. However, global awareness of the destination remains relatively low. As a result, further development of the industry is closely linked to its competitive performance and strategic positioning in the international tourism market.

The expansion of global tourism and the increasing complexity of its competitive landscape have prompted international organizations, national economies, and research institutions to develop standardized frameworks for statistical accounting, big data analysis, competitive indicators, indices, rankings, and reporting methodologies (WEF, WTTC, UNWTO, IATA, WB, EU, TRUSTYOU). Academic research on tourism competitiveness has evolved alongside studies on business competitiveness, with increasing attention paid to destination-specific competitive frameworks. As Hefny (2023) notes, “since the early 1990s, research has progressively shed light on the characteristics and framework of destination competitiveness” (for a detailed discussion, see the Literature Review section).

This study aims to develop a research model tailored to analyzing the competitive environment of a specific tourism destination and assessing its relative competitive position. The proposed research design is tested using Georgia as a case study.

The structure of the paper is as follows: First, the thematic literature on conceptual approaches and models is reviewed, exposing the relevance of the applied Segment-centric Geo-competitive Environment of a Tourism Destination (SGE-TD) framework. Next, the study identifies countries that constitute Georgia’s foreign tourism market and segments these tourism-generating countries based on their preferred travel destinations. Subsequently, competitive indicators are selected and analyzed to characterize Georgia’s tourism competitive environment. The study then examines the key features of this environment, including its principal components, driving forces, the competitive positions of leading destinations, and the destinations identified as close competitors to Georgia. Finally, the research findings are generalized and discussed.

From a practical perspective, this study provides insights into Georgia’s tourism competitive environment, highlighting its key components, driving indicators, leading destinations, and close competitors. These findings inform potential strategic approaches to enhancing Georgia’s competitive positioning in the global tourism market.

1. Literature Review

Interest in research on tourism destination competitiveness has grown alongside the global expansion of the tourism industry. Over the past three decades, more than 1,100 articles on tourism destination competitiveness have been published in reputable journals (Haiyang et al., 2024). These studies address various facets of the subject, including theoretical foundations, competitive environment modeling, destination market segmentation, the identification of competitive variables and indicators, and the determination of competitive environments for competing destinations.

The concept of competitive strategy was introduced by Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter in 1979 through his widely recognized Porter’s 5 Forces framework. This model highlights the key competitive forces that a company must consider to strengthen its market position (Porter, 1979). Later, Porter expanded on this idea with the Diamond Model (1990), which evaluates an industry’s international competitiveness. Rugman and D’Cruz (1993) extended the Diamond Model further with the Double Diamond Model (DDM), incorporating competitive strategy on global, regional, and national levels.

Dwyer and Kim (2002) developed a Tourist Destination Competitiveness Model designed to facilitate comparisons between countries and tourism sectors. Initially tested in Australia, this model emphasized key elements of competitiveness from the broader literature while addressing the unique issues associated with destination competitiveness. Their subsequent work refined the methodology, expanding the range of competitive indicators used in the analysis (Dwyer & Kim, 2010).

Ritchie and Crouch (2003) proposed the Tourism Destination Competitiveness (TDC) and Sustainability Model, which focuses on the macro and micro levels of the competitive environment. This model identifies seven key components that influence a destination’s competitiveness and sustainability, highlighting the synergy between comparative and competitive advantages (Ritchie & Crouch, 2003; 2010). This dual perspective of competitiveness is essential for understanding a destination’s market position (Gonzalez-Rodríguez, 2023). A special study was dedicated to systematizing and explaining the definitions popularized in connection with the development of these concepts and models (Mazanec et al., 2007).

Various studies have explored specific components of the TDC model, particularly those related to the supply side of tourism destinations of different levels such as countries, regions, or specific locations. Their competitive indicators include factors like natural and cultural attractions, infrastructure, and services (Smith, 1988; Marais et al., 2017; Stalmirska, 2021). On the demand side, segmentation researches have focused on demographic, behavioral, psychographic, firmographic, and technographic factors, as well as geographical segmentations based on factors such as population density and climate (Ioannides & Debbage, 1998; Gillian Partin, 2011, Kotler & Armstrong, 2018; Cibinskiene, Snieskine, 215, Lopes, Munoz, Alarcon-Urbistondo, 2018). Many destinations use country of origin as a segmentation criterion to tailor their marketing strategies to specific tourist profiles (Dolnicer, 2008; A. Nella & E. Christou, 2021). Research on diverse aspects of tourists as buyers and territorial classification by their origin and visiting places significantly depends on the specifics of destinations and tourism sectors (A. Nella, E. Christou, 2021).

The competitive environment of a destination is multi-dimensional, encompassing core resources and attractors, supporting factors, destination policy, planning, development, and management. Ritchie and Crouch (2003) categorized these factors into the global (macro) and competitive (micro) environments. The macro-environment includes economic, technological, ecological, political, sociocultural, and demographic factors, while the micro-environment refers to the immediate forces influencing tourism activities within the destination itself (Ritchie & Crouch, 2003).

Some studies have criticized previous research for focusing too narrowly on either comparative or competitive advantages. Gonzalez-Rodríguez et al. (2024) proposed a hybrid approach that integrates both dimensions, offering a more holistic view of destination competitiveness (Gonzalez-Rodríguez et al., 2023).

In terms of research methodologies, scholars have applied classical and innovative analytical tools to assess destination competitiveness. Cracolici et al. (2006) used the Crouch-Ritchie Model to analyze destination efficiency and competitiveness, while Lusticku and Bednarov (2018) explored factors of competitiveness using the Integrated Model of Destination Competitiveness. These approaches provide valuable insights into how competitiveness influences destination performance.

Vobek K. emphasizes that “There is a vast body of literature about competition, competitive advantage, and competitive identity in tourism. Also, there is a dearth of studies linking tourism competitiveness (TC) to tourism performance” (Hossein et al., 2021). Destinations could be compared by their ability to adapt and maintain competitive positions in the tourism market, as changes in tourism affect destination performance and success” (Vodeb K., 2012, pp. 273-278).

A popular methodology dedicated to the assessment of tourist destination competitiveness through Crouch-Ritchie’s model and the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index (TTCI) implies the methods of data envelopment and truncated regression with bootstrap (Gonzalez-Rodríguez et al., 2023). Benchmarking is another popular method used in competitiveness assessments. It involves identifying and comparing the strengths and weaknesses of a destination relative to its competitors (Zlatkovic, 2016).

A wide variety of analytical methods were adjusted to the variables and indicators presented in the aforementioned models of tourism destinations’ competitiveness. A special statistical tool was developed focused on the tourism decision process, which starts from the demand schedule for holidays and ends with the choice of a specific holiday destination, and was tested in the case of Italy as a tourism destination (Gardini, 2008). Studies have also employed Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) methods, such as ELECTRE I, to evaluate tourism destinations (Botti & Peypoch, 2013). The Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) model (Tontini, Silveria, 2007), as well as the Importance-Performance-Competitor Analysis (IPCA), has been used to compare destinations and highlight areas for strategic improvement (Albayarak et al., 2018).

Some scholars have further refined the categorization of competitive indicators. Ferreira and Perks (2020) identified three primary themes influencing destination competitiveness: core, facilitating, and supporting indicators. These themes provide a foundation for understanding the socioeconomic dynamics between developed and developing countries. Additionally, the 4 Cs Tourism Destination Competitiveness Matrix (Diamantino et al., 2020) identifies four key dimensions: Capacity, Competence, Communication, and Creativity. These dimensions are essential for evaluating the competitiveness of destinations, as they address aspects like infrastructure, human resources, marketing, and innovation.

The role of information technologies in tourism competitiveness has also garnered attention in recent studies. Researchers have explored how digital tools and innovations enhance competitiveness in European destinations (Petrovic et al., 2016; Irtyshcheva et al., 2022).

A growing body of literature evaluates the competitiveness of specific countries as tourism destinations. Comparative studies have been conducted on destinations such as Hong Kong (Enright & Newton, 2004), Italy (Goffi, 2013), Greece (Marios, 2015), and Portugal (Mira et al., 2016), Serbia (Milutinovic, Vasovic, 2017), India (Saqib, 2019), Japan (Takatoshi et al., 2022), China (Liu et al., 2022), Georgia (Okroshidze et al., 2024), etc.

Georgia, as a relatively emerging tourism destination, presents a special unique case.

The leading segments of Georgia represented by Armenia, Turkey, and Russia and composing more than 50% of the foreign visitors, make up less than 3% of the global travelers, while the global leading tourism generators —US, China, Germany, and the UK—making up more than 25% of the global tourism market, contribute just less than 2.8% to the Georgian market (DataBank-WB; GNTA.GE). This reality underlines the need for a tailored approach to understanding Georgia’s competitive environment, specifically through the Segment-centric Geo-competitive Environment of a Tourism Destination (SGE-TD) framework.

3. The Research Design and Applied Methodology

The research design consists of the following steps:

Identifying competing tourist destinations for the destination under study (Georgia in this case);

Analyzing the identified competing travel destinations composing the competitive environment for the study destination;

Identifying the features of the studied competitive environment, focusing on the driving forces and the competitive position of the study destination

Step 1: Identifying Competing Tourist Destinations for the Destination Under Study

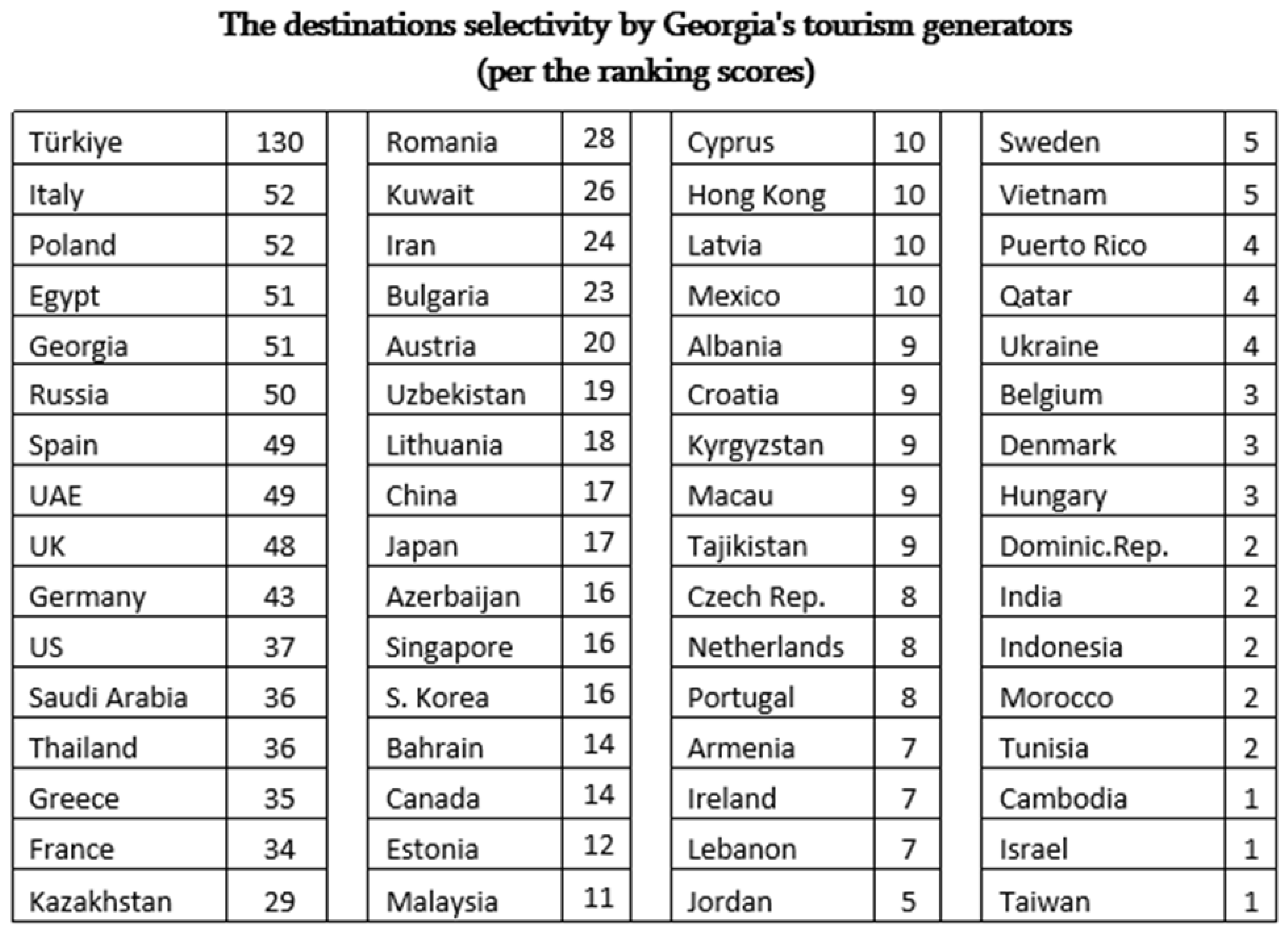

To determine the destinations that constitute Georgia’s competitive environment, we apply the Segment-centric Geo-competitive Environment of a Tourism Destination (SGE-TD) approach (Khelashvili, 2023). First, we identify Georgia’s leading tourism-generating countries, followed by identifying the primary travel destinations for tourists from each of these countries.

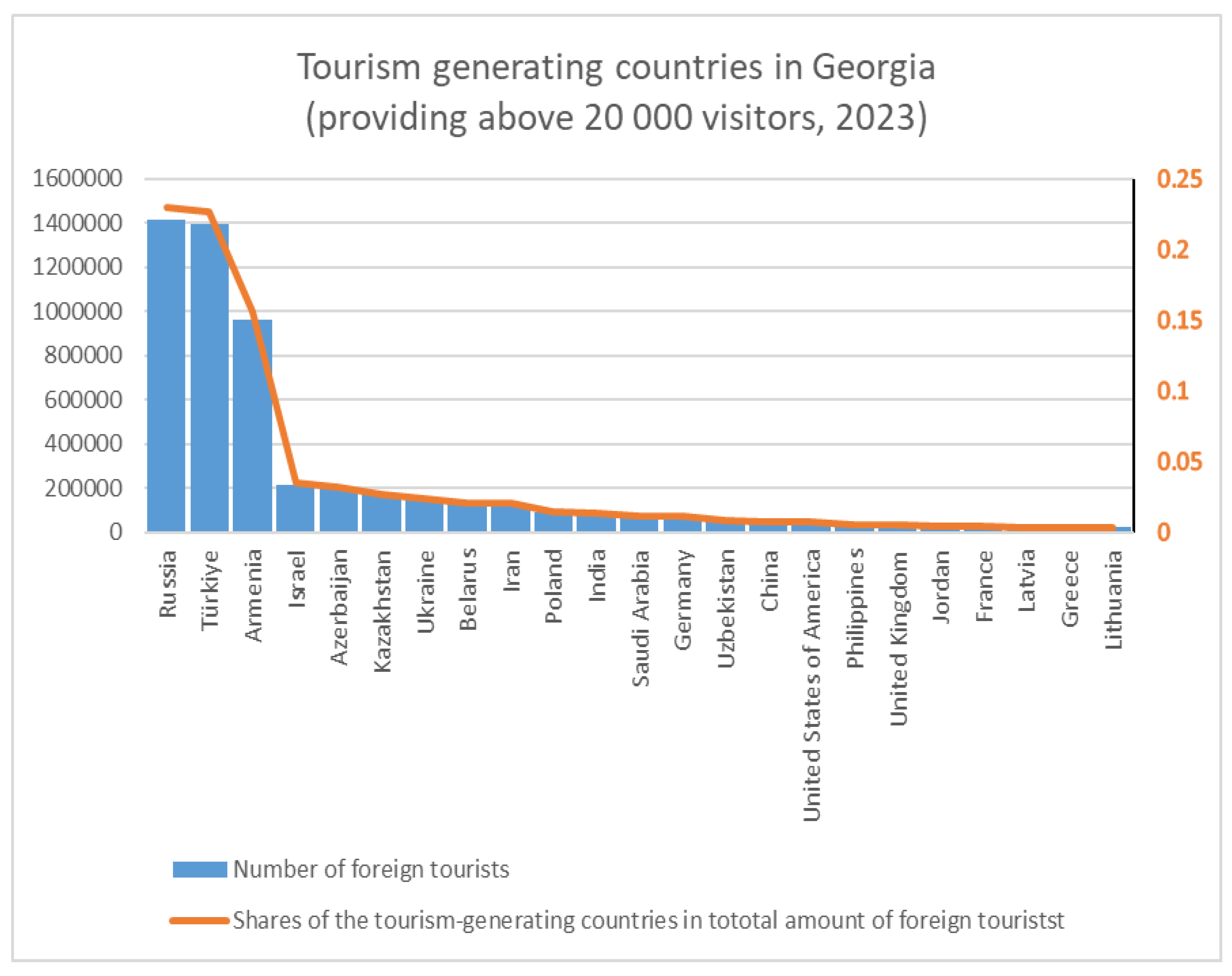

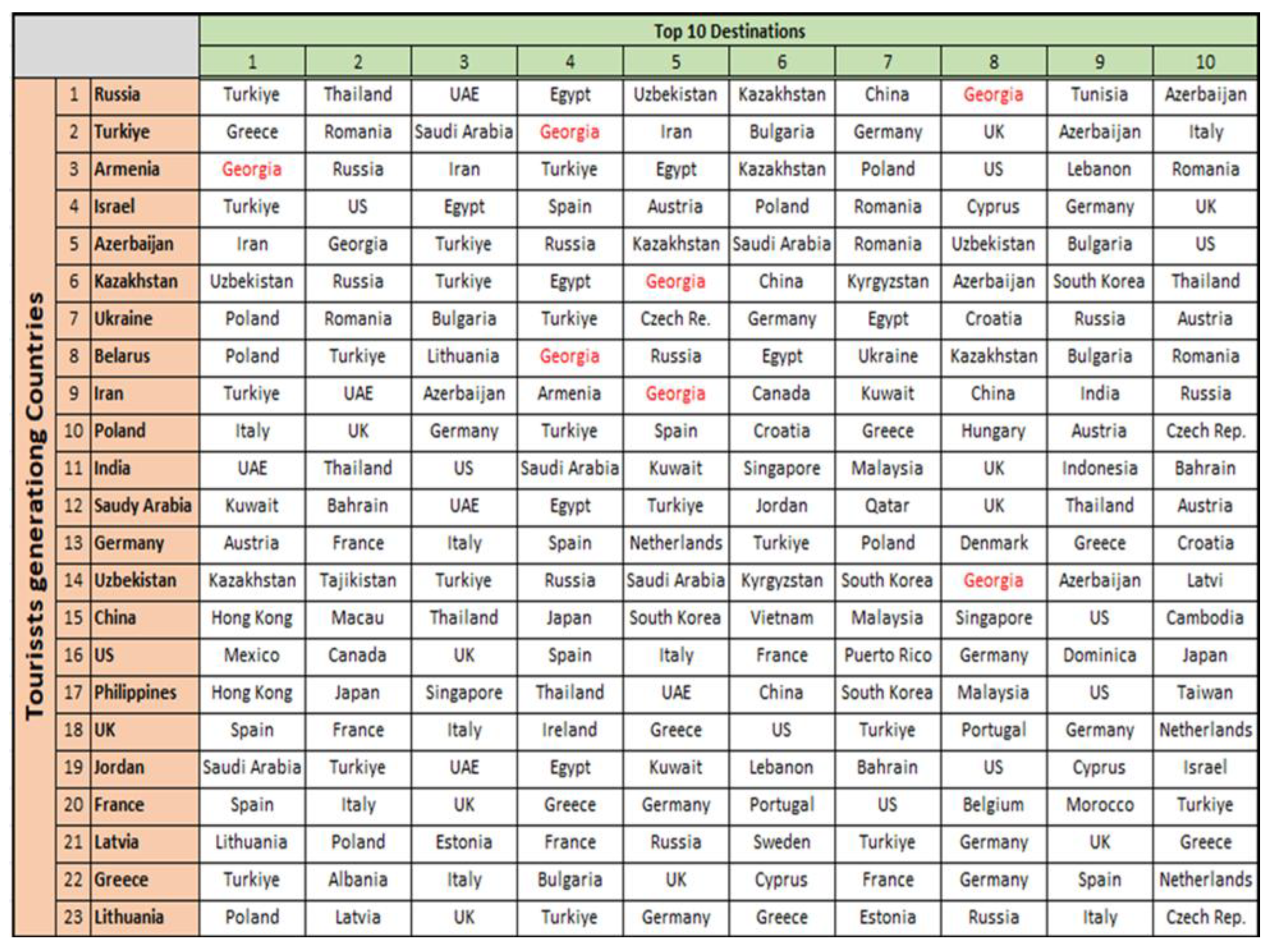

For the first task of this stage, it was assumed that tourists from these countries should collectively account for at least 80% of all foreign visitors to Georgia in order to ensure adequate representation. According to the latest statistics for 2023, the number of countries that annually send 20,000 or more tourists to Georgia is 23. The share of tourists from these countries accounts for 87.6% of all foreign tourists visiting Georgia (see Graphic 1), which justifies the use of these country-related data for further analysis.

The stark reality underscores the importance of market diversification, which is essential for strengthening Georgia’s competitive position in its foreign tourism market.

To achieve the objective of the second task of the same step, we determined the top 10 preferred tourism destinations (countries) from each of the 23 segments previously outlined. This analysis revealed 61 tourism destination countries, which collectively constitute Georgia’s geo-competitive environment, as defined by the SGE-TD concept (see

Table 1).

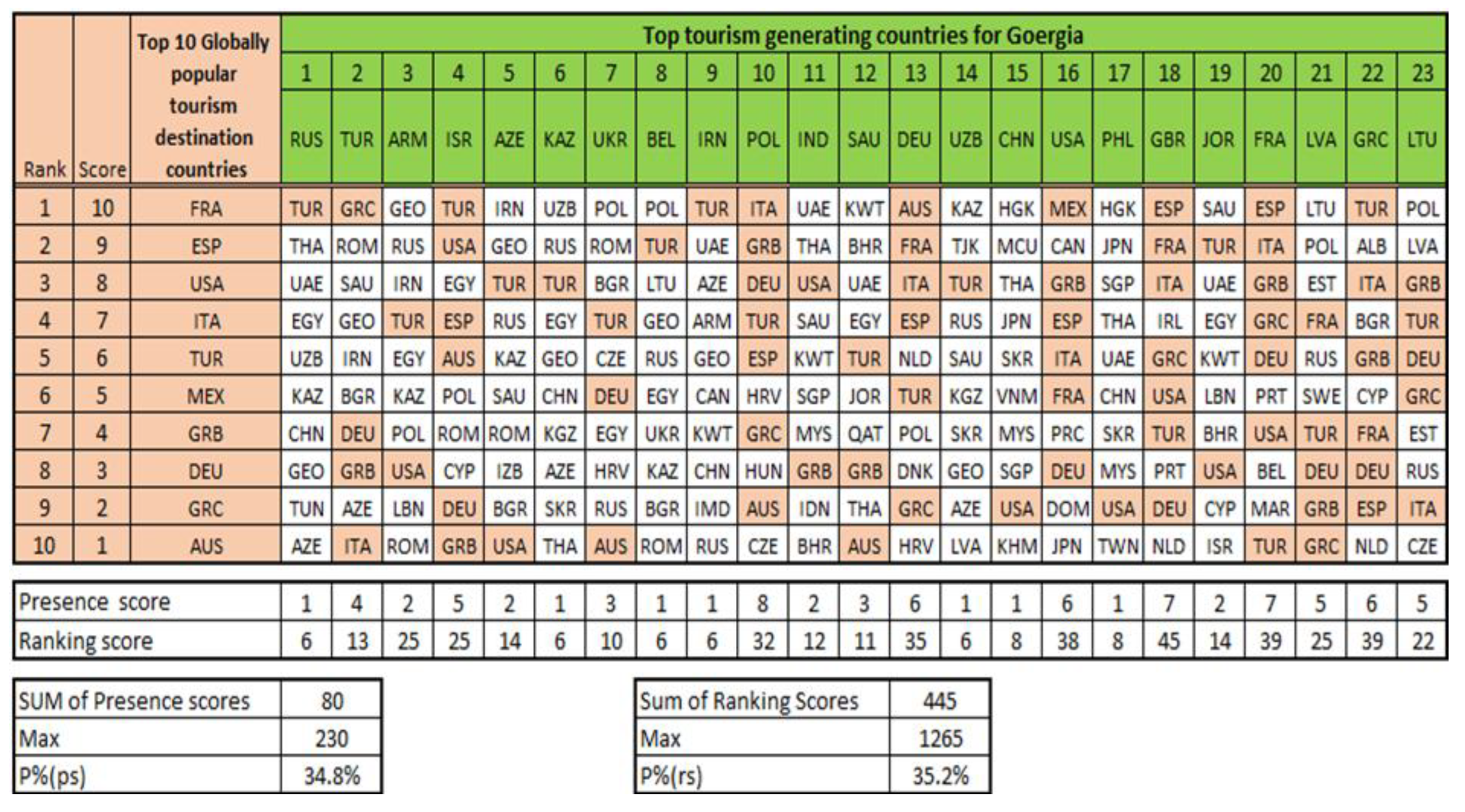

To assess the validity of considering Georgia’s international tourism competitive environment (SGE-TD of Georgia) separately from the global competitive tourism environment, a comparison was conducted using two alternative calculations.

The first calculation shows the presence of the top 10 most popular tourist destinations globally in within the list of the top 10 preferred destinations for countries generating foreign tourism to Georgia. The second calculation is similar but includes ranking scores for destination preferences, ranging from 10 for the most popular to 1 for the least popular destination

(a) P%(ps) = (SUM DS/SUM DG) 100% = (79/230) *100% = 34.3%;

(b) P(rs)% = [SUM DS(s)/SUM DG(s)] 100% = (453/1265) *100% = 35.8%

Where,

P% (ps) - Share of top preferred global destinations among the 10 preferred

destinations of the studied segments by presence scores;

DS (ps) - Number of the top preferred global destinations present among the

top 10 preferred destinations of the studied segments;

DG - Top 10 preferred tourism destinations in the global market.

The calculation in (b), which incorporates ranking scores for globally popular destinations present in the top 10 preferred destinations of the studied segments, yielded similar results. Both calculations indicate that the preferred travel destinations among Georgia’s tourism-generating countries do not align with those in the global tourism market. Approximately 35% of the preferred destinations overlap with around 75% being different.

These calculations validate the consideration of Georgia’s SGE-TD as distinct from the global tourism market.

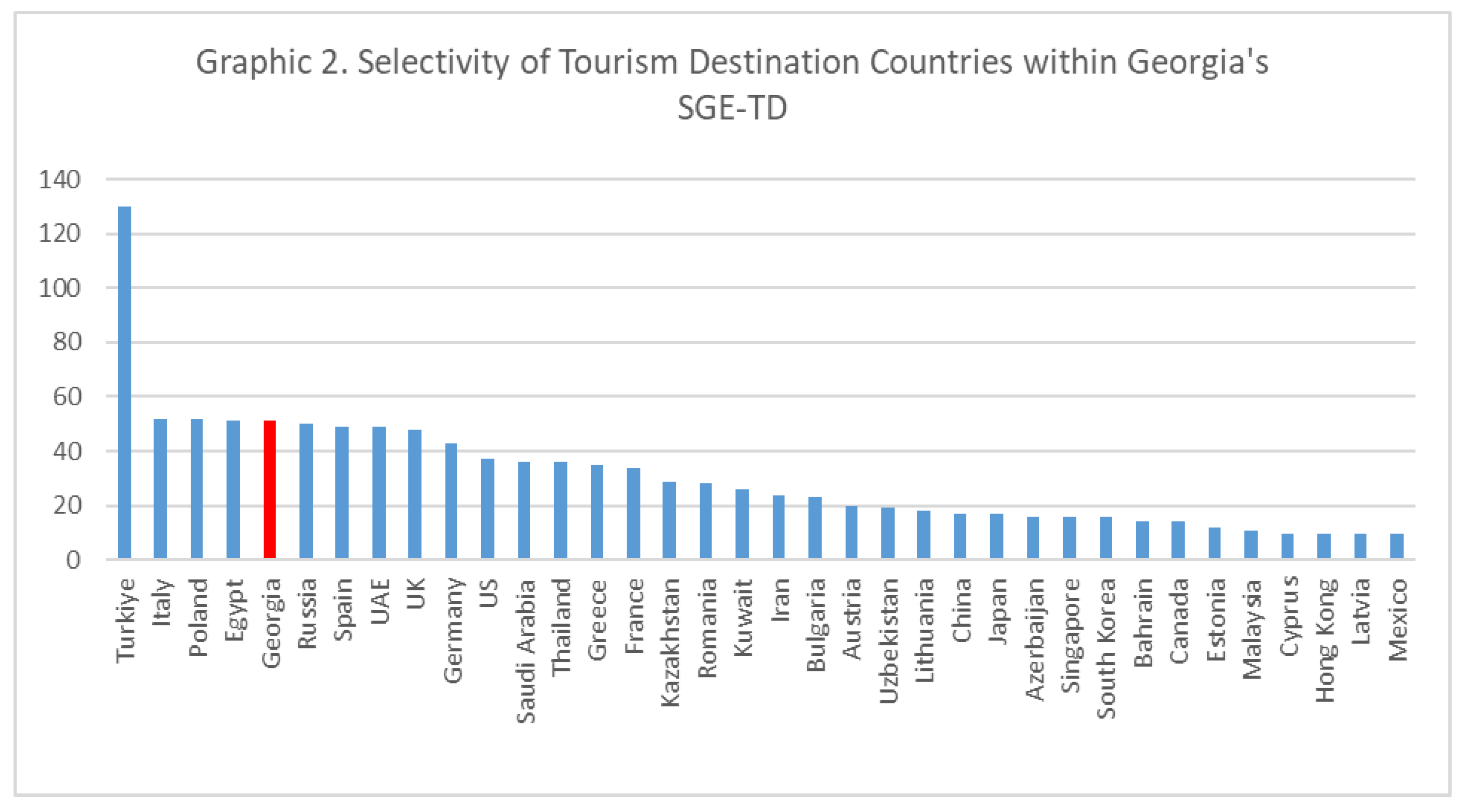

Regarding the selectivity of destinations within Georgia’s SGE-TD, it is important to highlight that despite the considerable differences among destinations, Turkey stands out as particularly popular. It is followed by 31 relatively popular destinations (with ranking scores of 5 and higher), including Georgia itself (see Graphic #2,

Appendix A).

Table 2.

Selectivity of the world’s top tourist destinations in Georgia’s tourism-generating countries.

Table 2.

Selectivity of the world’s top tourist destinations in Georgia’s tourism-generating countries.

Step 2: Analyzing the identified competing travel destinations composing the competitive environment for the study destination;

Following the identification of key components in the competitive environment, such as market segments and their preferred travel destinations, the next step involves:

(A) Determining relevant competitive indicators for the study;

(B) Analyzing the competitive environment composed of the identified competing

tourism destinations.

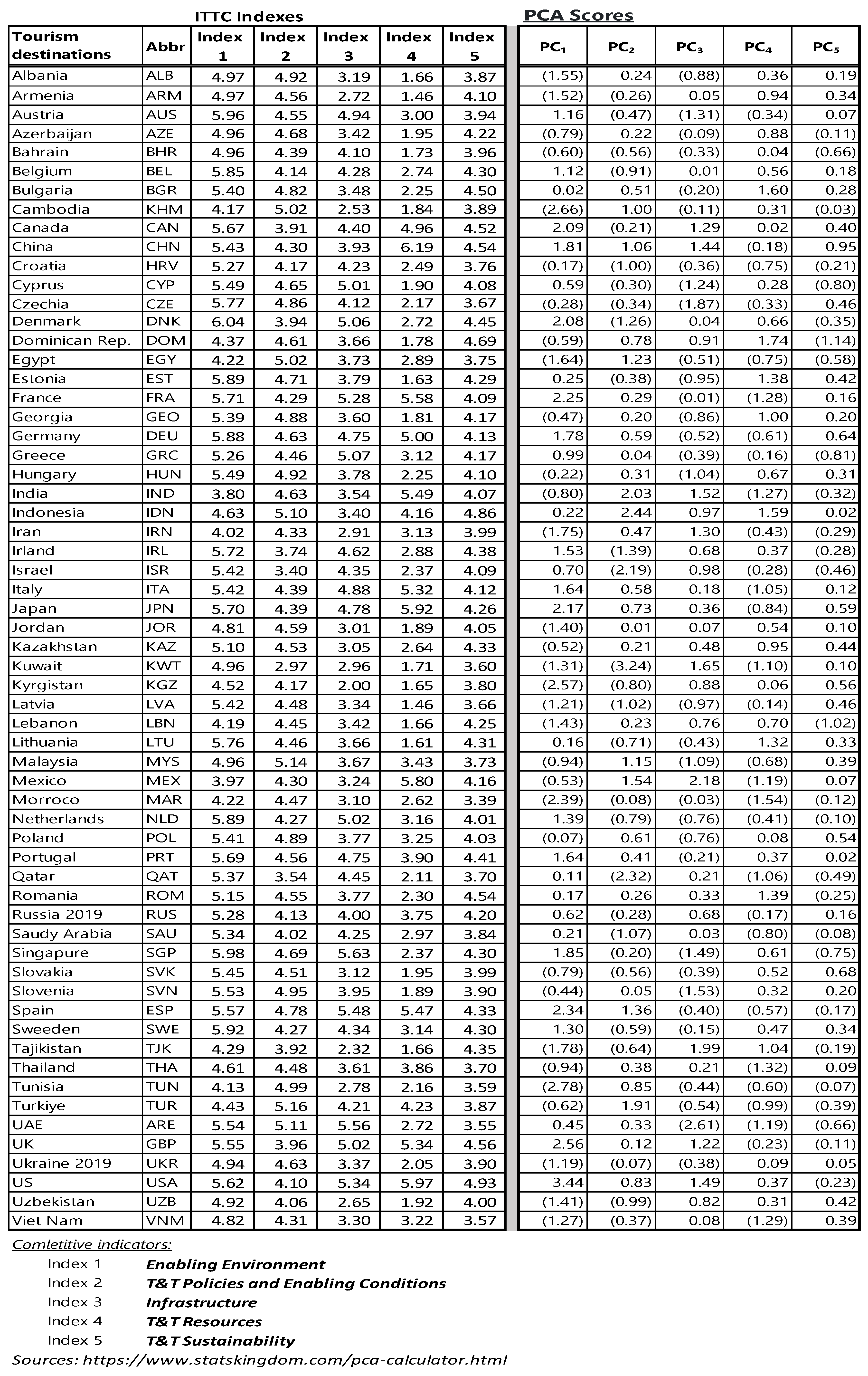

To address Objective A, relevant competitive characteristics, indicators, pillars, and indexes are considered. Given the methodology, scope, and content of these indicators—as well as data availability for the studied countries—this study utilizes data from the World Economic Forum’s Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index (WEF TTCI).

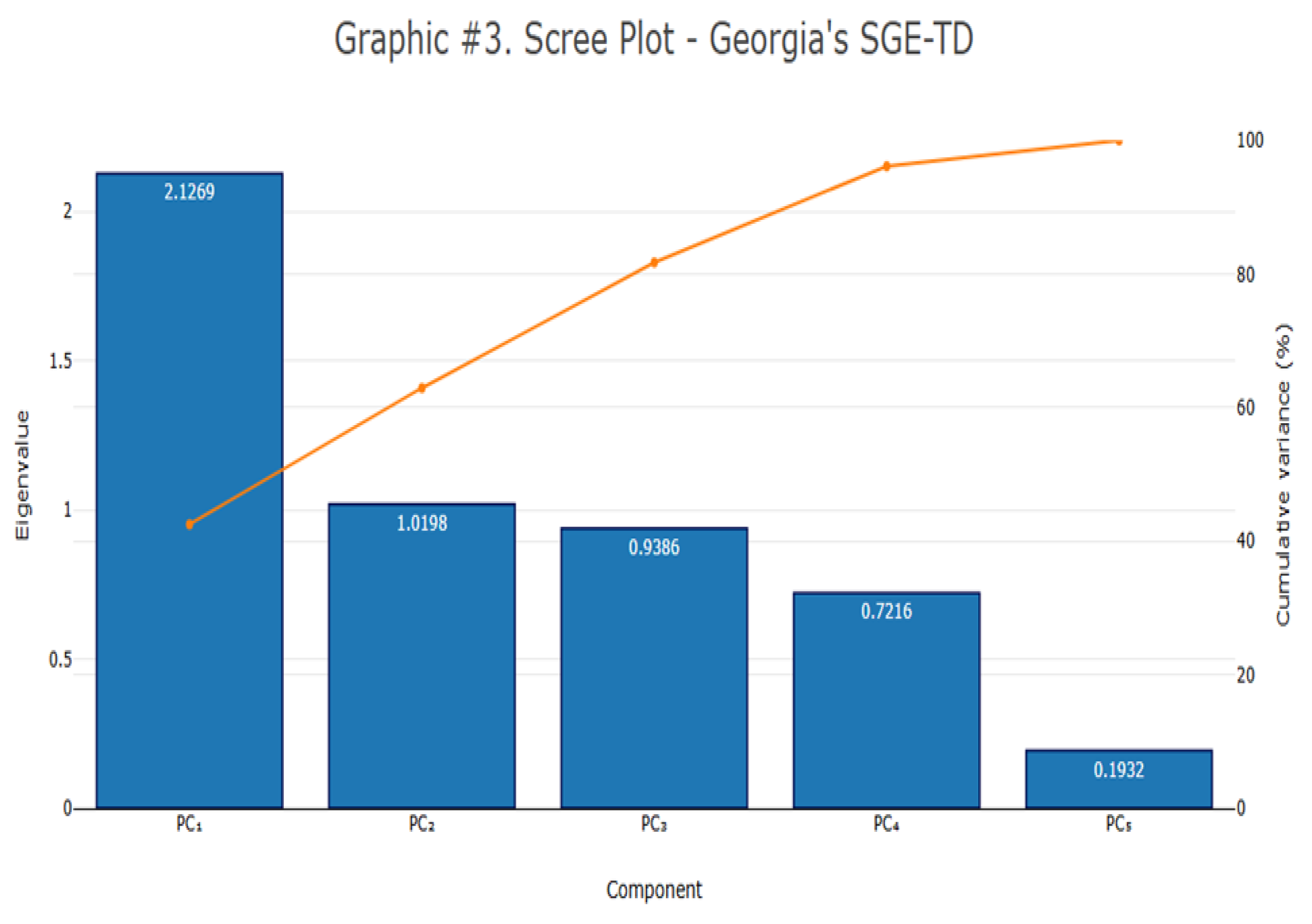

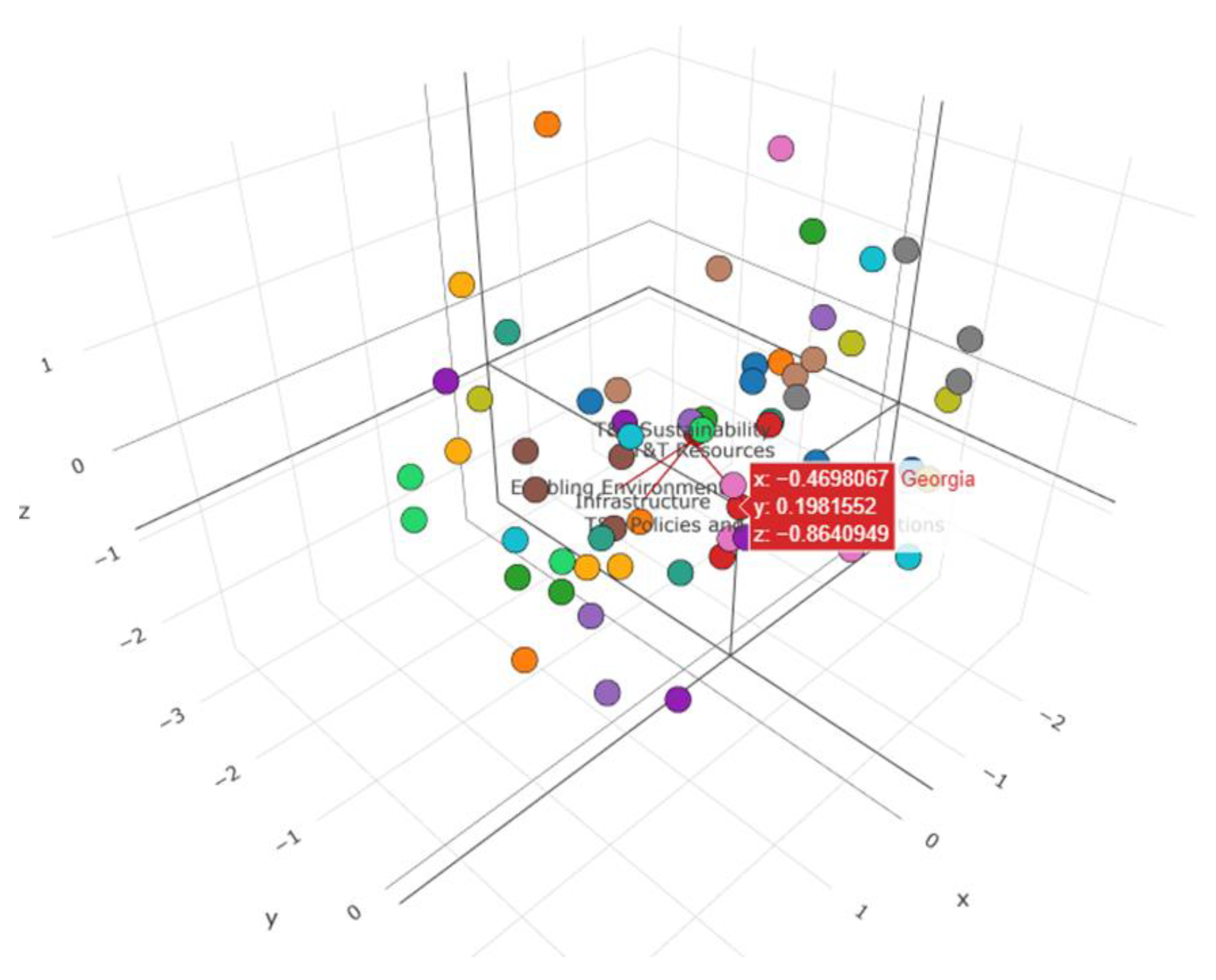

For Objective B, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to reduce the complexity of the dataset, which comprises five competitive indexes across 61 tourism destination countries. The PCA results revealed substantial data variation. To adequately capture this diversity, three principal components were selected for further analysis and interpretation based on their contribution to overall data variance:

• PC1 (42.5%)

• PC2 (20.4%)

• PC3 (18.9%)

Together, these components account for approximately 82% of the total variance (see Graphic 3 and

Table 3).

Table 3.

Eigenvalues.

| ParameterParameter |

PC₁ |

PC₂ |

PC₃ |

PC₄ |

PC₅ |

| Eigenvalue |

2.1269 |

1.0198 |

0.9386 |

0.7216 |

0.1932 |

| % of Variance |

42.538 |

20.396 |

18.771 |

14.431 |

3.8634 |

| Cumulative (%) |

42.538 |

62.934 |

81.705 |

96.137 |

100 |

This high variance coverage demonstrates that PCA effectively identifies the most critical underlying factors, reinforcing its robustness as an analytical tool for assessing competitive dynamics among tourism destinations.

The visualization of this diversity implies a 3D graphical expression (See graphic #4,

Table 4, and

Table 5)

Graphic 4. 3D PCA graphic of Georgia’s SGE-SD.

Table 4.

Eigenvectors.

| |

|

Vector2 |

Vector3 |

Vector4 |

Vector5 |

| Enabling Environment |

0.5217 |

-0.3757 |

-0.4386 |

0.1972 |

0.5962 |

| T&T Policies and Enabling Conditions |

-0.1618 |

0.7367 |

-0.6203 |

0.198 |

0.084 |

| Infrastructure |

0.5984 |

-0.002 |

-0.3309 |

-0.2493 |

-0.6858 |

| T&T Resources |

0.4255 |

0.5 |

0.3649 |

-0.5341 |

0.3879 |

| T&T Sustainability |

0.4032 |

0.257 |

0.4245 |

0.7579 |

-0.1293 |

Table 5.

The covariance matrix.

Table 5.

The covariance matrix.

| Group\Group |

Enabling Environment |

T&T Policies and Enabling Conditions |

Infra-

structure

|

T&T Resources |

T&T Sustainability |

| Enabling Environment |

1 |

-0.1686 |

0.6865 |

0.099 |

0.2671 |

| T&T Policies and Enabling Conditions |

-0.1686 |

1 |

-0.06151 |

-0.0532 |

-0.0866 |

| Infrastructure |

0.6865 |

-0.06151 |

1 |

0.4719 |

0.2616 |

| T&T Resources |

0.099 |

-0.0532 |

0.4719 |

1 |

0.3395 |

| T&T Sustainability |

0.2671 |

-0.0866 |

0.2616 |

0.3395 |

1 |

Step 3. Identifying the features of the studied competitive environment

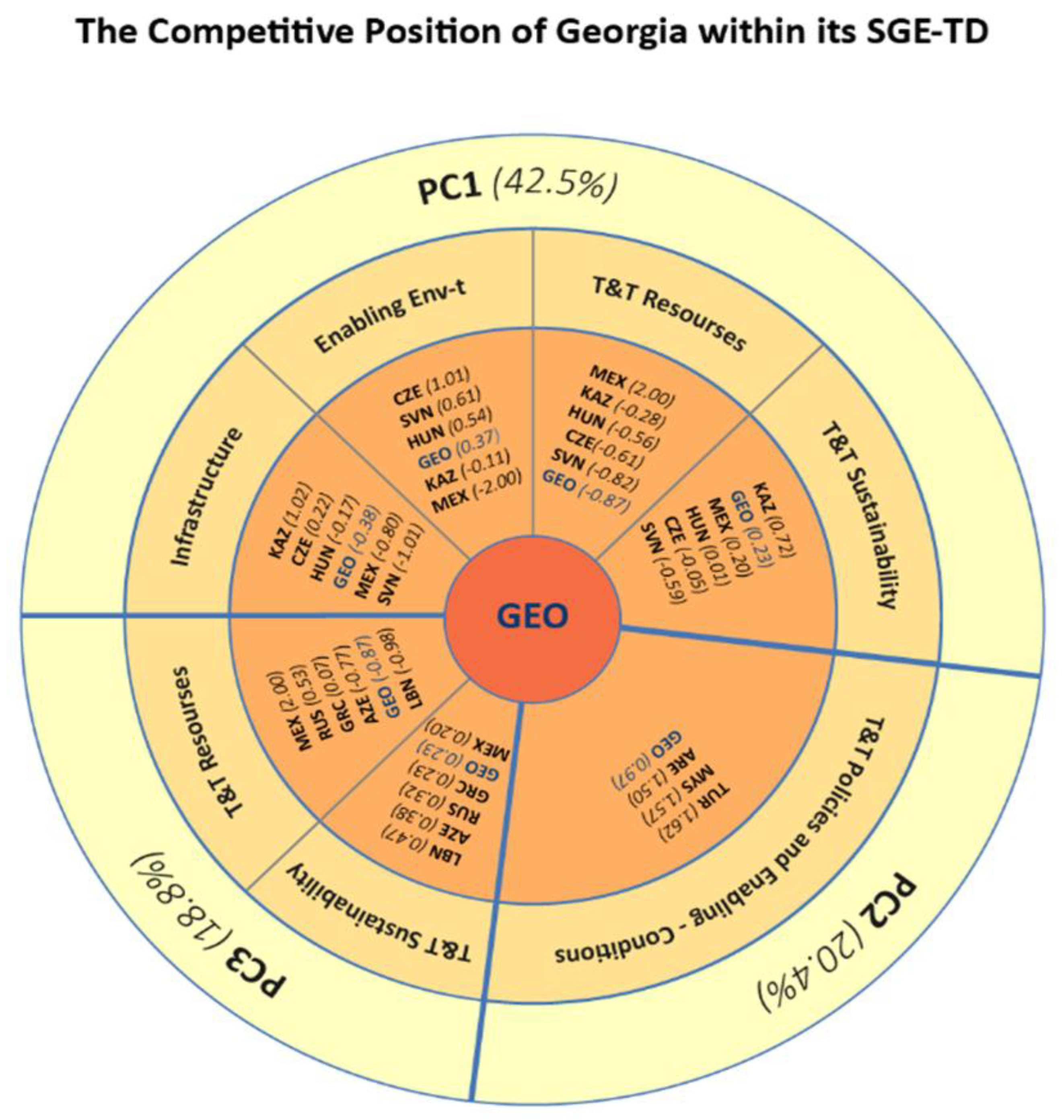

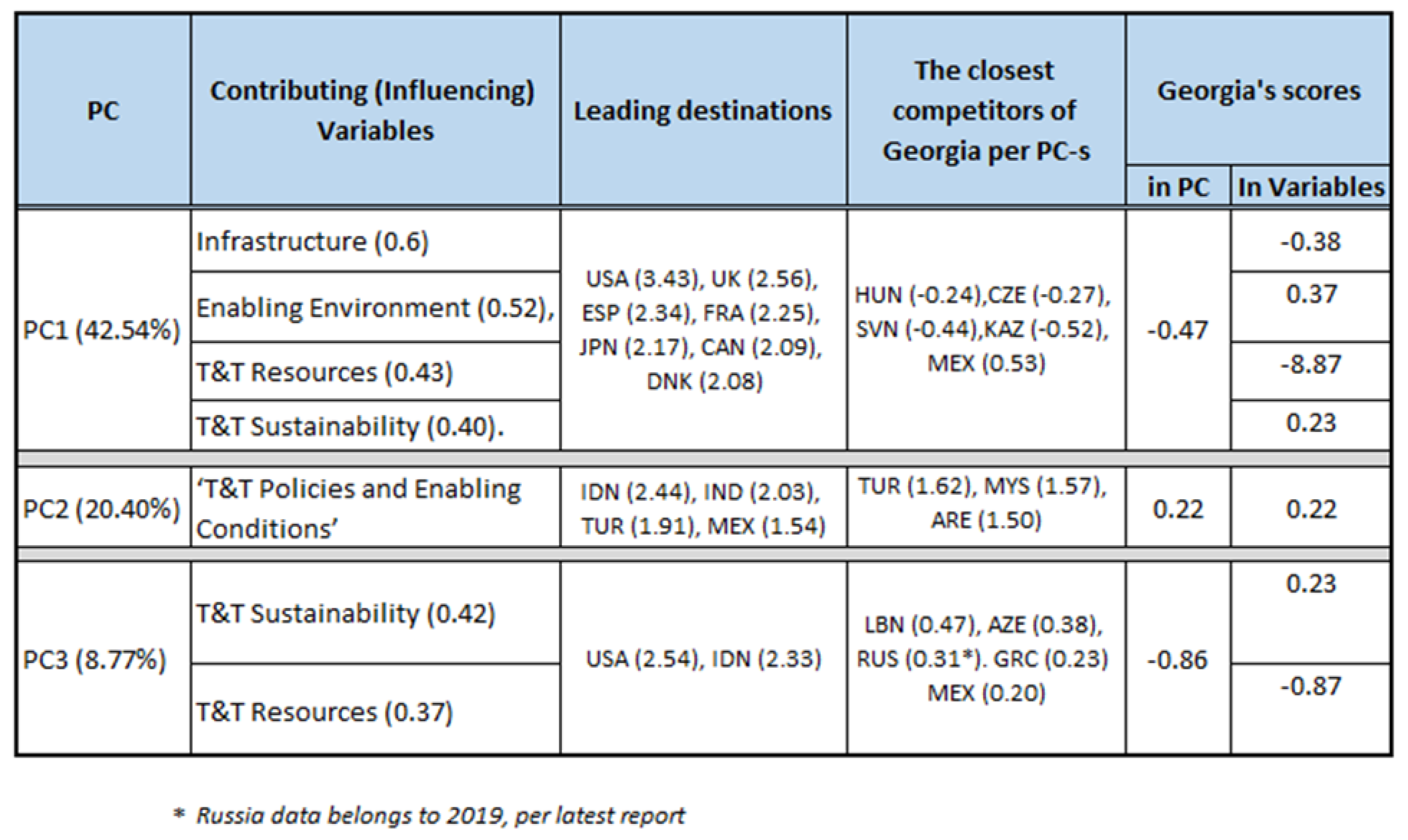

The principal components identified, along with the corresponding competitive variables and scores of tourist destinations, demonstrate both the general and specific features of the competitive environment studied, as well as Georgia’s competitive position within it.

PC1 (42.54% variance) emphasizes the significance of “Infrastructure” (0.60) and “Enabling Environment” (0.52), followed by “T&T Resources” (0.43) and “T&T Sustainability” (0.40). Leading destinations in these categories, with their different contributions in different variables, include the US, the UK, Spain, France, Japan, Canada, and Denmark (Score range between 2.0-3.5; refer to see Table in

Appendix B).

Georgia holds a moderate position in this principal component, with a slightly negative score of -0.47, ranking 35th among all destinations. This is due to a negative score in “Infrastructure” (-0.38), partly balanced by a positive score in the

“Enabling Environment

” (0.37). A Similar balance is seen in relation to the other variables in this vector; Georgia has a negative score in “T&T Resources” (-0.87) and a positive score in “Sustainability” (0.23) (refer to see

Appendix B, Score Tables).

Georgi

a’s primary competitors in PC1 are Slovenia, the Czech Republic, and Hungary, while Kazakhstan and Mexico closely follow. However, when considering this relationship across the most influential variables in PC1 individually, more competing destinations emerge. For instance, in terms of the “Infrastructure” variable, Georgia competes with Slovenia, China, Estonia, Hungary, Romania, Egypt, Malaysia, the Dominican Republic, Lithuania, and Thailand (with scores ranging from between 0.00 and -0.37) (refer to

Appendix B, Score Table). (Note: The two variables mentioned in PC1—T&T Resources (0.43) and T&T Sustainability (0.40)—will be further analyzed in the following PC3, where they play a leading role.)

PC2 (20.40% variance) increases the combined coverage of all variations up to 62.95% (see

Table 2 above). This component focuses on “T&T Policies and Enabling Conditions,” which shows the highest score in the list of all other variables (score 0.74). The top countries in this vector are Indonesia, India, Türkiye, and Mexico (scores between 1.54 and 2.44). Additionally, the variable driving this principal component - ‘T&T Policies and Enabling Conditions’ - is significantly influenced by Türkiye, Malaysia and the UAE (scores above 1.5) (see

Appendix B).

Georgia possesses a similarly moderate position in the PC2 component, although it holds a relatively high rank (29th) among all destinations. The gained score (0.22) is its only positive one across all three principal components (see

Appendix B). This position reflects its relative strength in the tourism policy indicator while leaving room for further improvement.

According to the applied calculation, Georgia’s closest foremost competitors in PC2 are Lebanon, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan (scores between 0.21 and 0.24). In the position along the PC2 driving variable, that is “T&T Policies and Enabling Conditions”, Georgia holds a more advanced position, ranked 12th in the whole considered market. In this dimension, the closest competitors are Hungary, Albania, and Poland (scores between 0.98 and 1.07).

PC3 (variance 18.77%) accrues the combined coverage of all variance up to 81.70%, emphasizing the role of “T&T Sustainability” (0.42) and T&T Resources” (0.37). The leading destinations in this line are the US and Indonesia (scores vary between 2.54 and 2.33, respectively) (see Score Table,

Appendix B).

In this component, Georgia holds a relatively low position (score -0.86) and is ranked 50th among all destinations. Similar to the PC1 case, controversial scores appear in the driving variables of PC3. In part, Georgia shows a negative score in “T&T Resources” (-0.87) and a positive one in “Sustainability” (0.23). (see page Countries vs PC - Score table, Georgia). Georgia’s lower rank and negative positioning in this component underline areas where the country could enhance its resource base and sustainability efforts. The interpretation of this position is relevant as it identifies areas for strategic improvement.

The closest competitors of Georgia in this principal component are Lebanon, Azerbaijan, and Russia (score 0.31 per the latest 2019 data), as well as Greece with an equal score and Mexico (scores between 0.20 and 0.47). (see

Appendix B).

4. Generalized Outcomes

The obtained results and the compiled interpretations are summarized in graph #.5 (see Graphic 5,

Table 6). It displays the close competitors of the study tourist destination—in this case, Georgia—across each analyzed competitive variable, which in turn are allocated per identified main principal components of the studied SGE-TD of Georgia.

Graphic 5.

Table 6.

Competitive position of Georgia within its SGE-TD.

Table 6.

Competitive position of Georgia within its SGE-TD.

According to the studied tourism destination, Georgia possesses a moderate position in its SGC-TD per PC1 and PC2 and a relatively low follower position per PC3 (SEE Graphic 5,

Table 6). The positive score in PC2 near zero (0.22) suggests that Georgia’s “Tourism policies” and “Enabling Conditions” are comparable to the average of other tourism destinations; however, it leaves room for improvement. The negative scores in PC1 and especially in PC3 emphasize the importance of advancing the position, especially in raising the acknowledgment of the country’s rich and diversified T&T Resources, as well as in strengthening infrastructure to improve competitiveness. These recommendations align with the PCA results.

Georgia, within its tourism competitive environment, appears to be in tight competition with different destinations, depending on the competitive indicators. In relation to infrastructure and enabling environment, such competing destinations are Kazakhstan and Mexico, while with regard to T&T policies and enabling conditions—Türkiye, Malaysia, and the United Arab Emirates. The largest number of the closest competing destinations appears in terms of T&T Sustainability as well as T&T Resources.

In this study, we selected the ranking positions of destinations that are located in close proximity to Georgia. In particular, three positions above and two positions below Georgia, giving priority to the number of advanced destinations and to the country’s promotion in its competitive environment.

The revealed outcomes suggest options for strategies to advance the competitive position in the county’s tourism competitive environment, which can be prioritized based on the country’s general strategy for economic development and its priorities. The suggestion that these insights can contribute to Georgia’s broader economic development strategy also adds value, making the analysis more impactful.

The generalized methodological outcomes of the provided research imply the logic of sequential research stages, a set of conceptual approaches, and optional tools corresponding to each stage (see

Table 7).

The suggested methodology and the developed research design can be applied to other tourism destinations and their geo-competitive environments. In addition, the same research design can include more detailed variables of a tourism competitive environment depending on the research objectives and data availability.

References

- Albayarak Tahir - Importance Performance Competitor Analysis (IPCA): A study of hospitality companies. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2015, 48, 135-142;

- Albayrak Tahir, Meltem Caber, González-Rodríguez M. Rosario, Aksu Akın Analysis of destination competitiveness by IPA and IPCA methods: The case of Costa Brava, Spain against Antalya, Turkey. Tourism Management Perspectives. Volume 28, October 2018, Pages 53-61. Elesevier;

- Análisis Turístico. 2019. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/jta-05-2019-0019/full/html;

- Athina Nella, Evangelos Christou, Market segmentation for wine tourism: Identifying sub-groups of winery visitors. European Journal of tourism Research. 2021 DOI: . [CrossRef]

- Botti Laurent, Peypoch Nicolas - Multi-criteria ELECTRE method and destination competitiveness. Tourism Management Perspectives. ELSEVIER. (6) 2013, pp. 108-113;

- Cibinskiene Akvile, Snieskiene Gabriele. Evaluation of City Tourism Competitiveness. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. Volume 213, ELSEVIER. 1 December 2015, Pages 105-110. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042815057584;

- Crouch, G.I.,& Ritche, J.R.B. (1999). Tourism competitiveness, and social prosperity, Journal of Business Research, 44(3), 137-152. [CrossRef]

- Cvelbar Liubica Knazevic, Dwyer L, Mihalic Tanja et al., Drivers of Destination Competitiveness in Tourism: A Global Investigation. Volume 55, Issue 8, 2015; DatBank – WB. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/Series/ST.INT.DPRT#;. [CrossRef]

- Dolnicer Sara - Market Segmentation in Tourism. 2008. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/30387969_Market_Segmentation_in_Tourism;

- Dwyer L., Destination Competitiveness: A Model and Determinants. Published 2002. Business, Economics. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Destination-Competitiveness-%3A-A-Model-and-Dwyer/9cd31126d7634a74522e57b272b6a549cca79f0c;

- Dwyer L. Mellor R. Competitiveness of Australia as a Tourist Destination. Journal of Hospitality And Tourism Management. ResearchGate. January, 2003. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281392475_Competitiveness_of_Australia_as_a_Tourist_Destination;

- Dwyer Larry, Chulwon Kim. Destination Competitiveness: Determinants and Indicators. Current Indies in Tourism. Vol.6, issue 5., 2010, Destination Competitiveness: Determinants and Indicators: Current Issues in Tourism: Vol 6, No 5;

- Ekonomou George & Halkos George. Exploring the concept of tourism competitiveness across the OECD countries. Current Issues in Tourism. Taylor & Francis. Published online: 09 Aug 2024. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13683500.2024.2388803?src=Cite this article. [CrossRef]

- Enright Michael J., Newton Jams – Tourism destination competitiveness: a quantitative approach. Tourism Management. Vol 25, Issue 6, pp.777-788 2004. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0261517704001347;

- Fernández José Antonio Salinas, Paula Serdeira Azevedo, Martín José María Martín, Martín José Antonio Rodríguez. Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in the countries Most visited by international tourists: Proposal of a synthetic index. Tourism Management Perspectives. 33. ELSEVIER. (2019). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337465646_Determinants_of_tourism_destination_competitiveness_in_the_countries_most_visited_by_international_tourists_Proposal_of_a_synthetic_index;

- Fernández et al. (2020). Ekonomika Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in the countries most visited by international tourists: Proposal of a synthetic index. Pérez León et al. (2020). Tourism Management;

- Ferreira, D. & Perks, S. (2020). A Dimensional Framework of Tourism Indicators Influencing Destination Competitiveness. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 9(3): 1-22. DOI: . [CrossRef]

- Gardini Attilio - STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF TOURISM DESTINATION COMPETITIVENESS. STATISTICA, anno LXVIII, n. 2, 2008. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46553417_Statistical_Analysis_of_tourism_destination_competitiveness;

- Gillian Martin, 2011, p.16;

- Goffi Gianluca - A Model of Tourism Destination Competitiveness: The case of the Italian Destinations of Excellence. ResearchGate, 2013. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267331295_A_Model_of_Tourism_Destination_Competitiveness_The_case_of_the_Italian_Destinations_of_Excellence;

- Gonzalez-Rodríguez M.Rosario, Díaz-Fernandez M. Carmen, Pulido-Pavon Noemí Gonzalez-Rodriguez, Diaz-Fernandez, Pulido-Pavon - Tourist destination competitiveness: An International approach through the travel and tourism competitiveness index. Tourism Management. Perspectives. ELSEVIER. Vol. 47, June 2023.; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211973623000557.

- Hefny, …An overview of literature on destination competitiveness: A theoretical analysis of the travel and tourism competitiveness index. Lamiaa Hefny. PIJTH, Vol.2, issue. 2 (2023), 45-60);

- Hossein et al., 2021;

- Hossein Reza, Bazargani Zadeh, Kiliç Hasan. Tourism competitiveness and tourism sector performance: Empirical insights from new data Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. Volumem 46, March 2021, pp 73-82.; [CrossRef]

- Irtyshcheva Inna, Nadtochii Iryna , Popadynets Nazariy , Hryshyna Nataliya Sirenko Ihor. – EUROPEAN VECTOR OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF TOURIST DESTINATIONS’ COMPETITIVENESS IN DIGITAL ECONOMY. International Journal for Quality Research 16(4) 1211–1226 . ISSN 1800-6450 (2022); [CrossRef]

- Ioannides Dimitri, Debbage Keith G. The Economic Geography of the Tourist Industry. A supply-side analysis. Routledge. London and New York. 1998);

- Kotler & Armstrong, Principals of Marketing, 17th Global edition, 2018, on, p.213-218). + “using The Multiple Segmentation Bases- 217), 2018. https://opac.atmaluhur.ac.id/uploaded_files/temporary/DigitalCollection/ ODljY2E4ODIyODViZjFkODgzNDUxYWZlNWFhZmY2MGE5MDc0ZDVmYw ==.pdf;

- Kunst and Ivandić, (2021) International Journal of Tourism Research. The viability of the travel And tourism competitiveness index as a reliable measure of destination competitiveness: the case of the Mediterranean region; [CrossRef]

- Khelashvili Ioseb, Segment-Centric Geo-Competitive Environment of a Tourism Destination (A Case of Georgia). Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management Volume 11, Number 1, Jan.-Feb. 2023 (Serial Number 60); [CrossRef]

- Khelashvili I., Khartishvili L., Khokhobaia M. Clustering the Problems of Sustainable Tourism Development in a Destination: Tsaghveri Resort as A Case. Ankara Üniversitesi Çevrebilimleri Dergisi. 7(2), 83-97 (2019);

- Khelashvili, I. (Ed.) (2017): Problem Identification in Tourism using the Transdisciplinary Approach (Georgia as a case). The 2-nd International Conference – Challenges of Globalization in Economics and Business: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University;

- Lopes, A. P. F., Munoz, M. M., & Alarcón-Urbistondo, P. (2018). Regional tourism competitiveness using the PROMETHEE approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 73, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Lazarevic Sonja, Vasovic Neven M., - Competitive position of Serbia as a tourism destination on The international tourism market. Conference: 2nd International Scientific Conference Tourism in a function of development of the Republic of Serbia:Тourism product as a factor of Competitiveness of the Serbian economy and experiences of other countries At: Vrnjačka Banja, Serbia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327843594_Competitive_position_of_Serbia_as_ a_tourism _destination_on_the_international_tourism_market;

- Liu Haijun, Hasan Mihray, Cui Dong, Yan Junjie, Sun Guojun - Evaluation of tourism competitiveness and mechanisms of spatial differentiation in Xinjiang, China. Tenth International Congress on Peer Review and Scientific Publication. 2022. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0263229;, . [CrossRef]

- Luštický Martin, Bednářov Martina - Tourism Destination Competitiveness Assessment: Research & Planning Practice. GLOBAL BUSINESS & FINANCE REVIEW, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González et al., (2021). European Journal of Tourism Research;

- Maria Pafi, Wesley Flannery, Brendan Murtagh. Coastal tourism, market segmentation and Contested landscapes. Marine Policy. ELSEVIER, 2020. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308597X20300774;

- Marais Milandrie, Engelina Du Plessis, Saayman Melville. - A review on critical success factors in tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. Volume 31, June 2017, Pages 1-12. 2017;

- Mazanec Joseph A., Wober Karl, Zinc Andreas H. Journal of Travel Research, 2007. Travel and Tourism Association. SAGE. http://jtr.sagepub.com/content/46/1/86;

- Milutinovic Sonja, Vasovic Nevena, Competitive Position of Serbia as a Tourism Destination on the International Tourism Market. The Second International Scientific Conference, TOURISM IN FUNCTION OF DEVELOPMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA – Tourism product as a factor of competitiveness of the Serbian economy and experiences of other countries, Thematic Proceedings II Tourism International Scientific Conference Vrnjacka – TISC 2017 Vol 2 No 2. (2017): https://www.tisc.rs/proceedings/index.php/hitmc/article/view/124;

- Mira M.R., Moura A., Breda Z. - Destination competitiveness and competitiveness indicators: Illustration of the Portuguese reality. IPCA., Vol.14, Issue 2, July-December 2016. Pages 90-103.;, . [CrossRef]

- Modi Ravi Kant. Economic Contribution and Employment Opportunities of Tourism and Hospitality Sectors. The Emerald Handbook of Tourism Economics and Sustainable Development. ISBN: 978-1-83753-709-9, eISBN: 978-1-83753-708-2. Publication date: 18 September 2024. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/978-1-83753-708-220241015/full/html.;. [CrossRef]

- Murayama Takatoshi, Brown Graham, Hallak Rob, Matsuoka Kohsuke - Tourism Destination Competitiveness: Analysis and Strategy of the Miyagi Zaō Mountains Area, Japan. Journal of Sustainability. MDPI, Vol.14, Issue 5. 2022. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/15/9124; [CrossRef]

- Nella A. and E. Christou, 2021;

- Okroshidze Lali, Meyer Daniel F, Khelashvili Ioseb. An assessment of tourism competitiveness: a comparative analyses of Georgia and neighboring countries. Journal of Eastern European and Central Asian Research. Vol.11 No.2 (2024). https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=vxHHCngAAAAJ&citation_for_view=vxHHCngAAAAJ:qjMakFHDy7sC;

- Pérez León et al. (2020) Tourism Management Perspectives An approach to the travel and tourism competitiveness index in the Caribbean region;

- Petrovic Jelena, Milicevic Snezana, et al., - The information and Communication Technology as a factor of destination competitiveness in transition countries in Europe Tourism Economics, 2016. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1354816616653529;, . [CrossRef]

- Porter, Michael. “How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy.” Harvard Business Review. March-April 1979. pp. 137-145. https://hbr.org/1979/03/how-competitive-forces-shape-strategy; Harward Business Review. 2008. https://www.blueoceanstrategyaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/HBRs-10-Must-Reads-on-Strategy.pdf#page=26’.

- Porter Michael, The Competitive Advantage of Nations. Harcard Business Reviews, March-April, 1990. https://hbr.org/1990/03/the-competitive-advantage-of-nations;

- Ritchie Brent J.R. & Crouch Geoffrey I. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective. 2003, p 272). https://books.google.ge/books?hl=en&lr=&id=yvydAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=Ritchie+%26+Crouch,+2003&ots=lTJ-9ileWL&sig=UUvYz_QQeYxdTOAVW7YgGG3bUz4&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Ritchie%20%26%20Crouch%2C%202003&f=false.

- Ritchie, J.R. Brent, Crouch, Geoffrey I. A model of destination competitiveness/sustainability: Brazilian perspectives, 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262429837_A_model_of_destination_competitivenesssustainability_Brazilian_perspectives;

- Ribeiro Diamantino; Machado Luiz Pinto, Henriques Pedro. - The 4 C’s Tourism Destination Competitiveness Matrix Validation through the Content Validity Coefficient. - EPH – International Journal of Business & Management Science. Vo.^ Issue 7., July 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347061110_The_4_C%27s_Tourism_Destination_Competitiveness_Matrix_the_Construction_of_the_Matrix_Through_the_Delphi_Panel;

- Ritchie Brent J.R., Crouch Geoffrey I. - A model of destination competitiveness/sustainability: Brazilian perspectives. Revista de Administração Pública 44(5):1049-1066, ResearchGate. 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262429837_A_model_of_destination_competitivenesssustainability_Brazilian_perspectives#fullTextFileContent;

- Rugman Alan M. D’Criz Joseph R. The “Double Dimond” Model of International Competitiveness: The Canadian Experience. Management International Review, Vol. 33, Extensions of the Porter Diamond Framework (1993), pp. 17-39. Published by: Springer Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40228188;

- Smith Stephen L.J. Defining tourism a supply-side view. Annals of Tourism Research. Volume 15, Issue 2, 1988, Pages 179-190. ; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0160738388900813.

- Saqib Natasha - A positioning strategy for a tourist destination, based on analysis of customers’ perceptions and satisfactions: A case of Kashmir, India. Journal of Tourism Analysis: Revista de Serdeira Paula – Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in the countries most visited by international tourists: Proposal of a synthetic index | Paula Serdeira Azevedo – Academia; [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadis Marios and Varvaressos Stelios. - . A strategic analysis of Greek tourism: competitive position, issues and lessons. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure Vol. 4 (2) - (2015). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273309338_A_Strategic_Analysis_of_the_Greek_Leisure_Tourism_Competitive_Position_Issues_and_Challenges;

- Stalmirska Anna Maria. Local Food in Tourism Destination Development: The Supply-Side Perspectives. Tourism Planning & Development. Volume 21, 2021 - Issue 2. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351652647_Local_Food_in_Tourism_Destination_.

- Tontini G., Silveira A. Identification of satisfaction attributes using competitive analysis of the improvement gap. International Journal of Operations & Production Management · May 2007. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228644228_Identification_of_satisfaction_attributes_using_competitive_analysis_of_the_improvement_gap.

- TRUSTYOU. https://www.trustyou.com/blog/research/global-hospitality-statistics-2023/;

- Vodeb Ksenija. Competition in tourism in terms of changing environment. University of Primorska, Faculty of tourism studies – TURISTICA, Portorose, Slovenia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 44 ( 2012);

- World Economic Forum (WEC). Travel & Tourism Development Index 2024. https://www.weforum.org/publications/travel-tourism-development-index-2024/;

- Xia Haiyang, Muskat Birgit, Karl Marion, Li Gang, and Law Rob. Destination competitiveness research over the past three decades: a computational literature review using topic modelling. JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING2024, VOL. 41, NO. 5, 726–742. © 2024; [CrossRef]

- Xue Huaju, Fang Chengjiang. How to optimize tourism destination supply: A case in Shanghai from perspective of supplier and demand side perception. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2017;

- Zlatkovic Matea - Tourism Destination Benchmarking Analysis European Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies 1(1):283 April 2016. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318537572_Tourism_Destination_Benchmarking_Analysis.

- Georgian National Tourism Agency. GNTA https://gnta.ge/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/ENG.pdf;

- Statistica. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1099933/travel-and-tourism-share-of-gdp/;

- World Travel and Tourism Organization. https://wttc.org/.

Table 1.

Top tourism destinations for Georgia’s tourism generating countries.

Table 1.

Top tourism destinations for Georgia’s tourism generating countries.

Table 7.

The Generalized Research Structure.

Table 7.

The Generalized Research Structure.

| Research Design |

Research Methods |

| Initial step: Selecting the conceptual framework relevant to the study destination |

Segment-centric Geo-competitive Environment of a Study tourism Destination (SGE-TD) |

| Step 1. Identifying competing tourism destinations for the destination under study |

1.1 Selecting the leading tourism-generating countries in the study destination |

| 1.2 Determining the preferred tourism destinations in the selected tourism-generating countries. |

| Step 2. Analyzing the identified competing tourism destinations composing the competitive environment for the study destination |

2.1 Determining relevant competitive indicators for the study |

| 2.2. Analyzing the competitive environment composed of the identified competing tourism destinations |

| Step 3. Identifying the features of the studied competitive environment |

Identifying the principal components of the competitive environment and competitive position of the destination under study |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).