Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

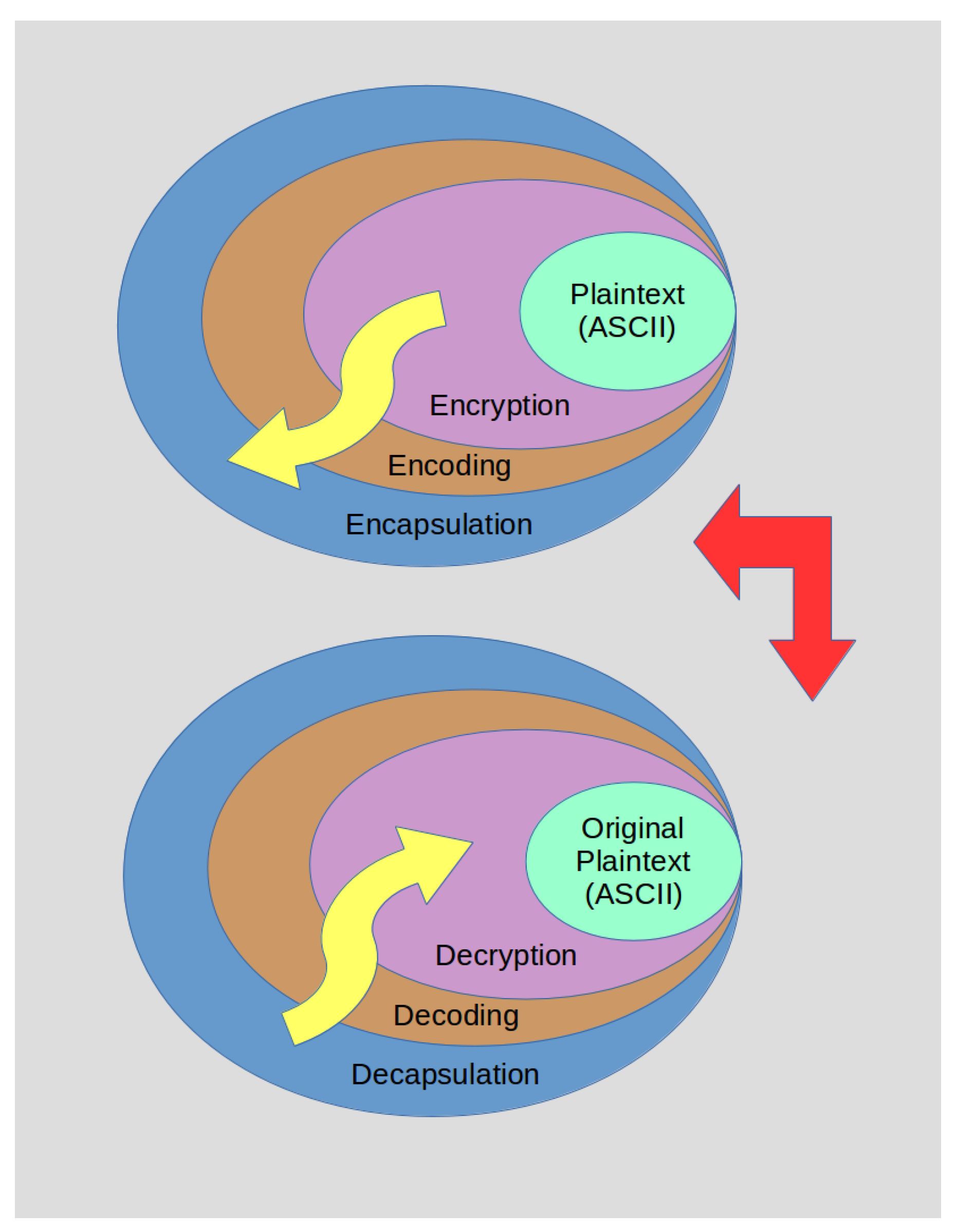

Virtual Reality (VR)/Metaverse is transforming into a ubiquitous technology by leveraging smart devices to provide highly immersive experiences at an affordable price. Cryptographically securing such augmented reality schemes is of paramount importance. Securely transferring the same secret key, i.e., obfuscated, between several parties is the main issue with symmetric cryptography, the workhorse of modern cryptography because of its ease of use and quick speed. Typically, asymmetric cryptography establishes a shared secret between parties, after which the switch to symmetric encryption can be made. However, several SoTA (State-of-The-Art) security research schemes lack flexibility and scalability for industrial Internet of Things (IoT)-sized applications. In this paper, we present the full architecture of the PRIVocular framework. PRIVocular (i.e., PRIV(acy)-ocular) is a VR-ready hardware-software integrated system that is capable of visually transmitting user data over three versatile modes of encapsulation, encrypted –without loss of generality– using an asymmetric-key cryptosystem. These operation modes can be Optical Characters-based or QR-tag-based. Encryption and decryption primarily depend on each mode’s success ratio of correct encoding-decoding. We investigate the most efficient means of ocular (encrypted) data transfer by considering several designs and contributing to each framework component. Our pre-prototyped framework can provide such privacy preservation (namely virtual proof of privacy (VPP)) and visually secure data transfer promptly (<1000 msec), as well as the physical distance of the smart glasses (∼50 cm).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1.

- We prototype PRIVocular, an open-source framework (that works for any type of asymmetric/symmetric key encryption scheme) that aims to operate as a virtual proof of privacy, for establishing strong cybersecurity constraints into industrial-level (IoT) vertical applications, that demand extremely low latency requirements.

- 2.

- We integrate PRIVocular inside a Metaverse-applicable immersive reality platform architecture.

- 3.

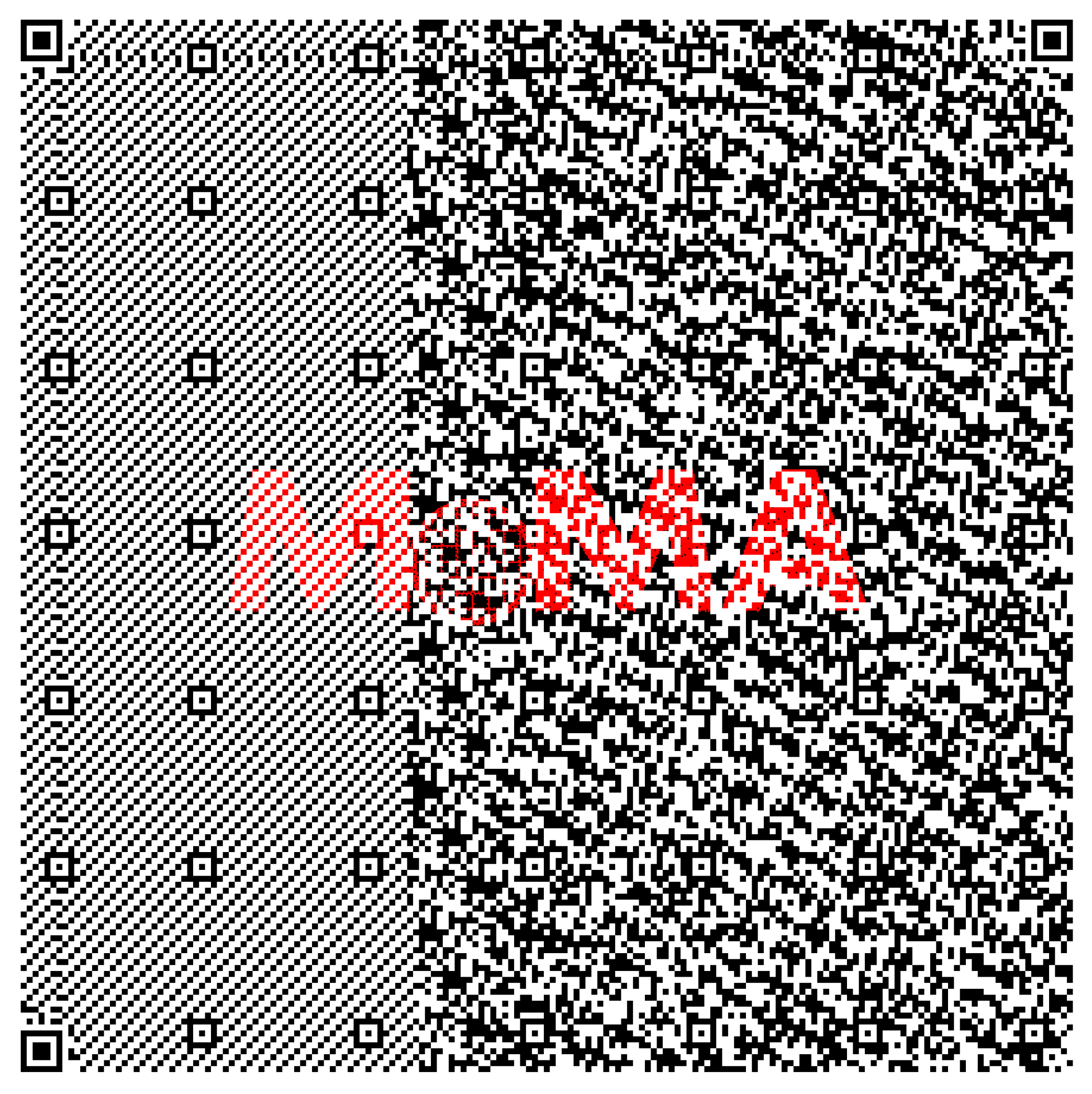

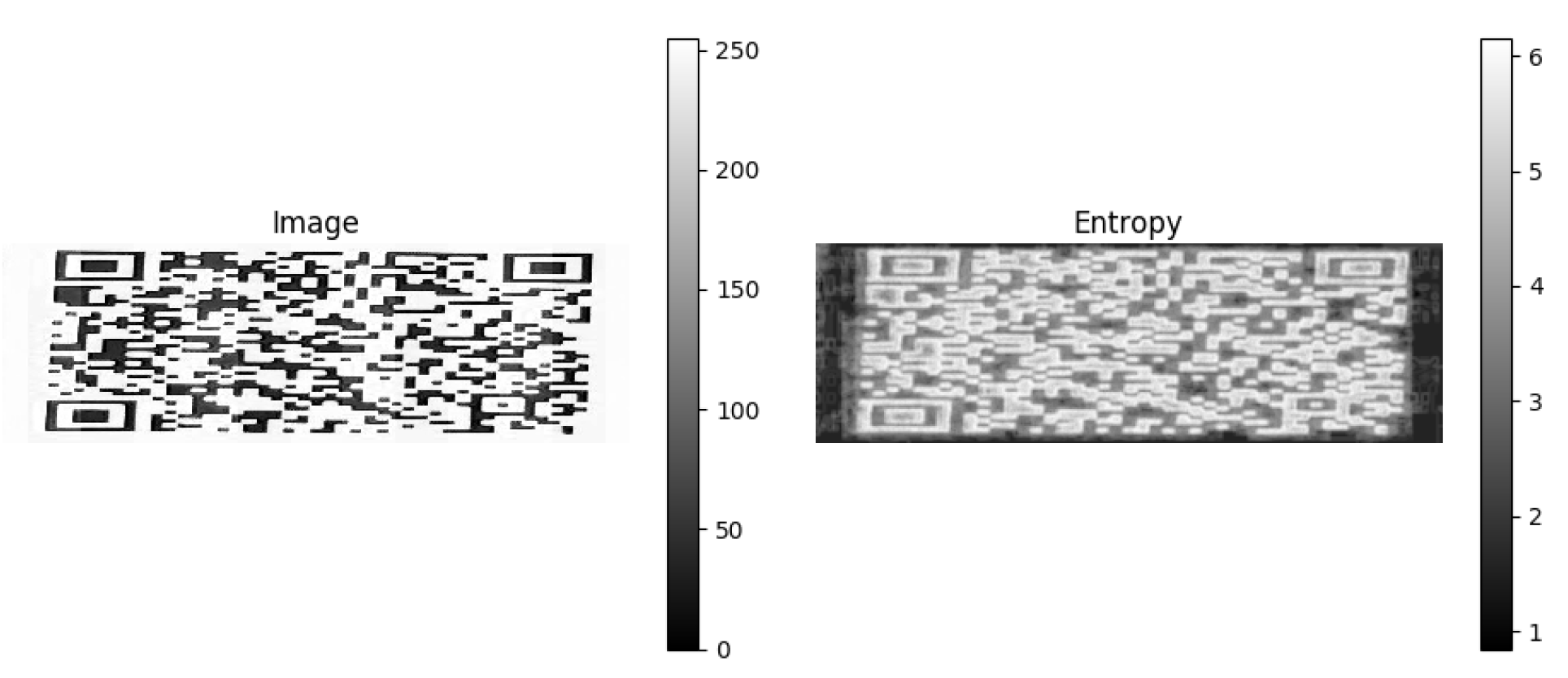

- We a priori design, implement, & incorporate MoMA tag inside our framework. The MoMA tag contains 61% more capacity than the QR tag (version 40).

2. Background

2.1. Tesseract OCR Engine

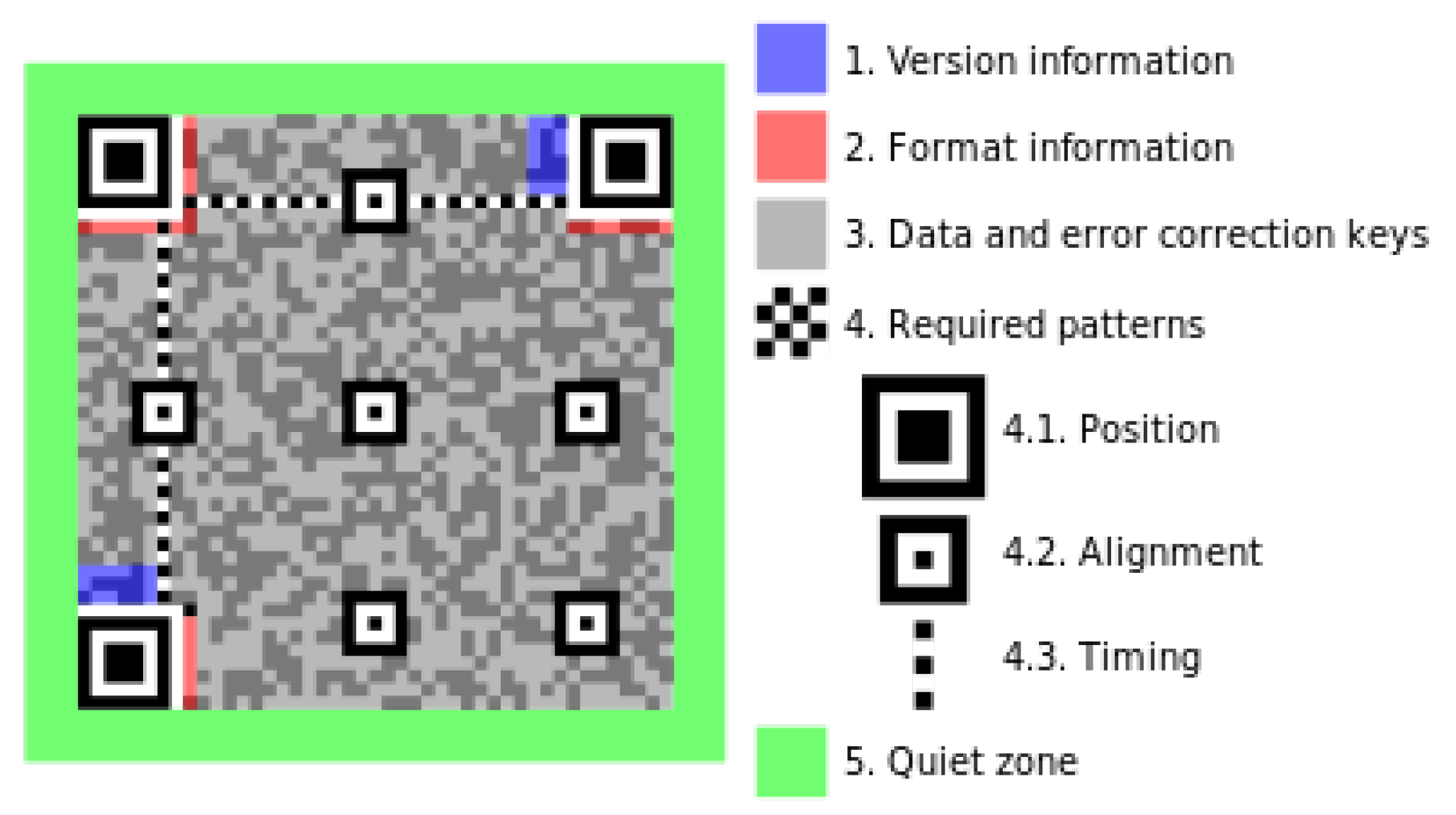

2.2. QR Code

| ECC Level | Amount of correctable data |

|---|---|

| Level L (Low) | 7% of codewords can be restored |

| Level M (Medium) | 15% of codewords can be restored |

| Level Q (Quartile) | 25% of codewords can be restored |

| Level H (High) | 30% of codewords can be restored |

2.3. Paillier Encryption Scheme

2.4. Related Work

3. The PRIVocular Framework

3.1. Contributions

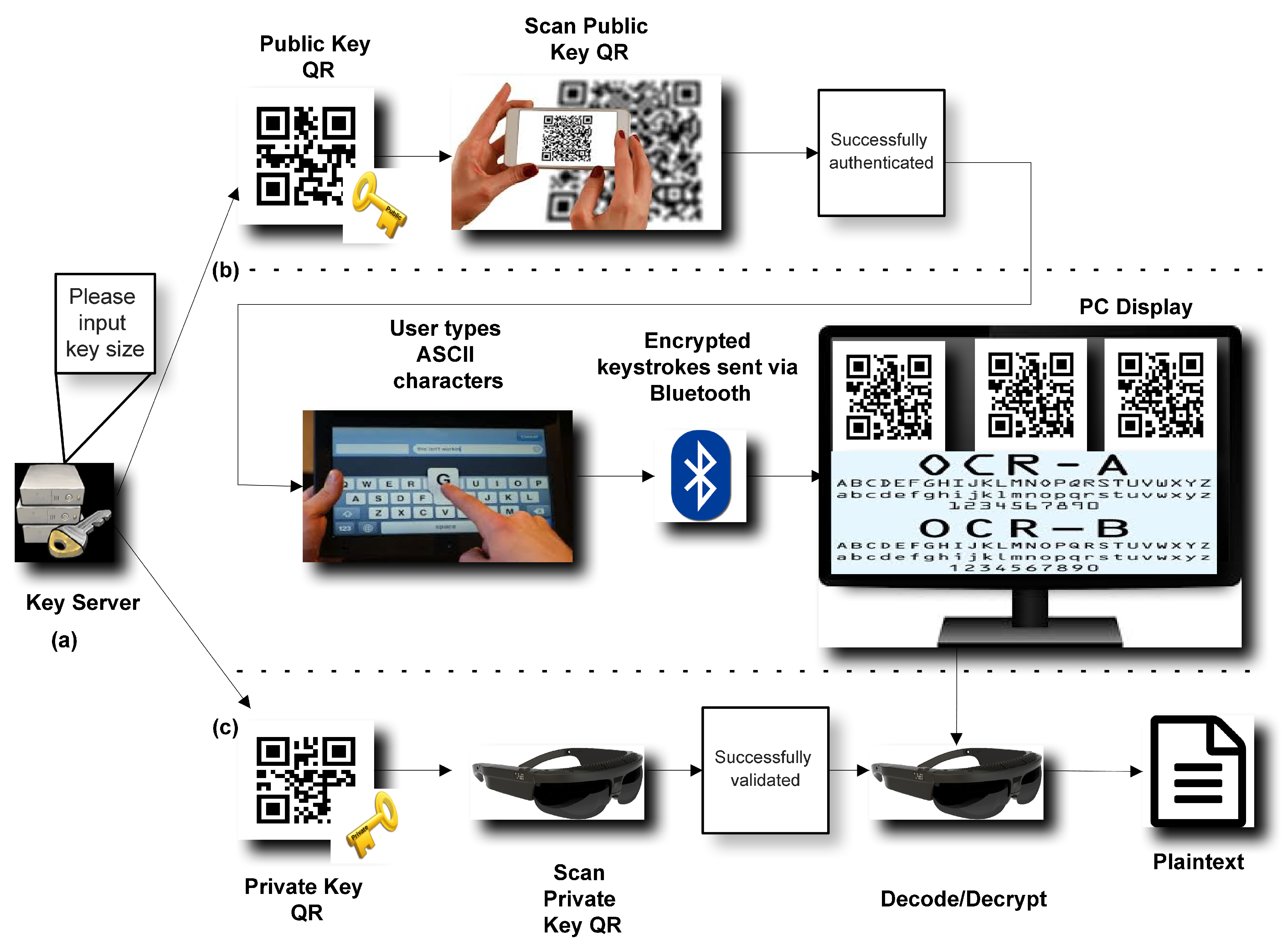

3.2. PRIVocular’s Architecture

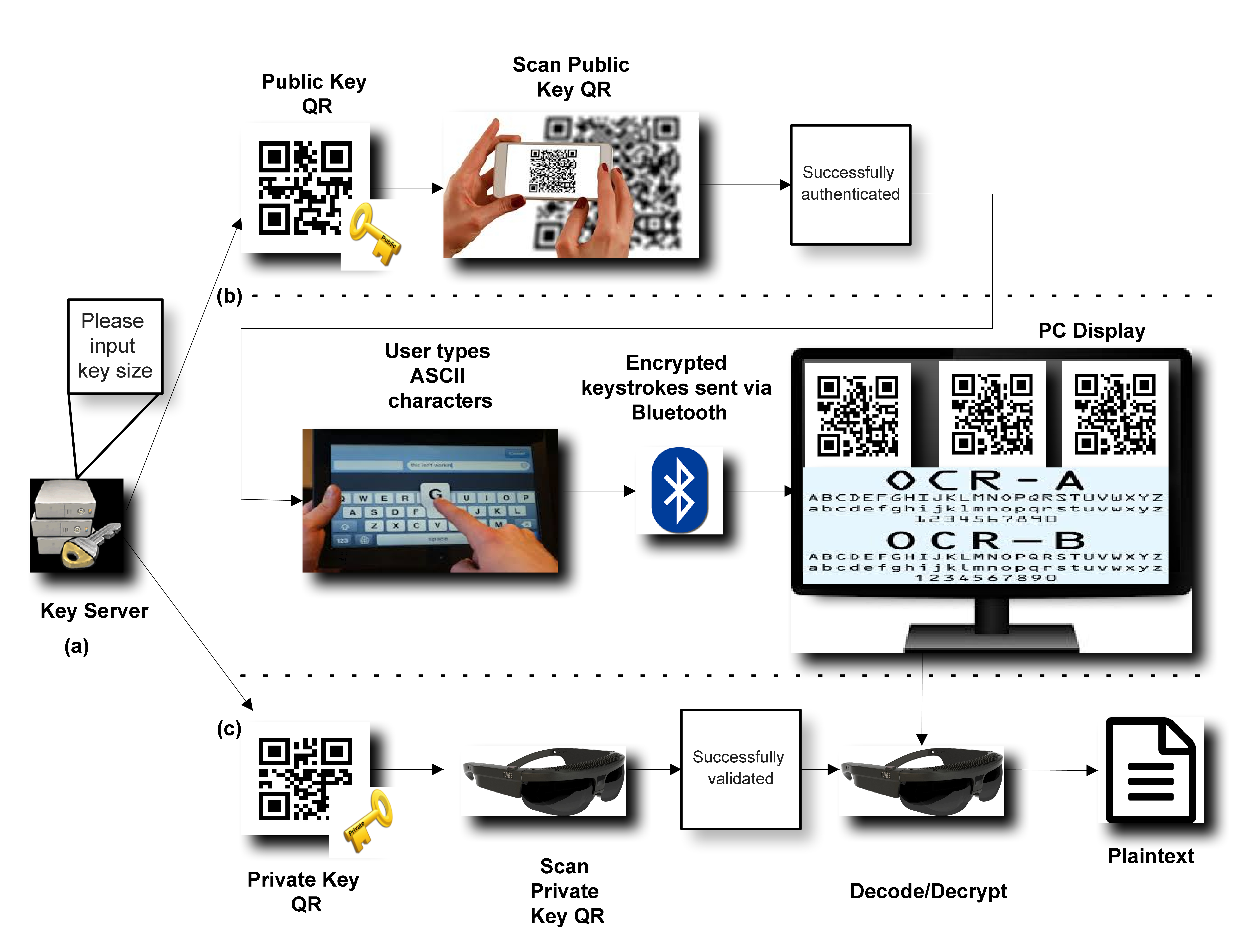

3.3. Use Case

- 1.

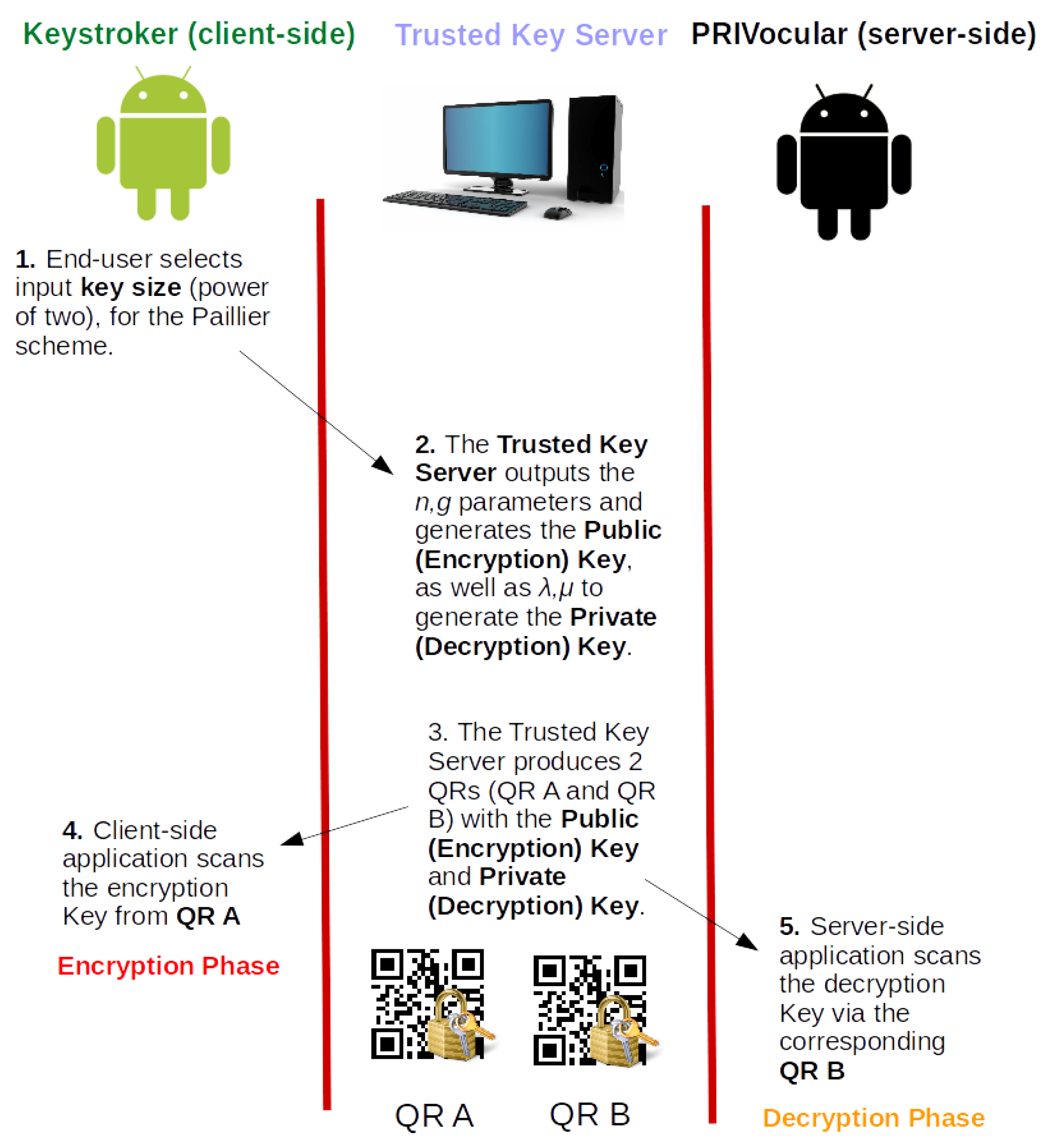

- The end-user inputs his/her desired key size in the (software-based) Key Server’s input prompt.

- 2.

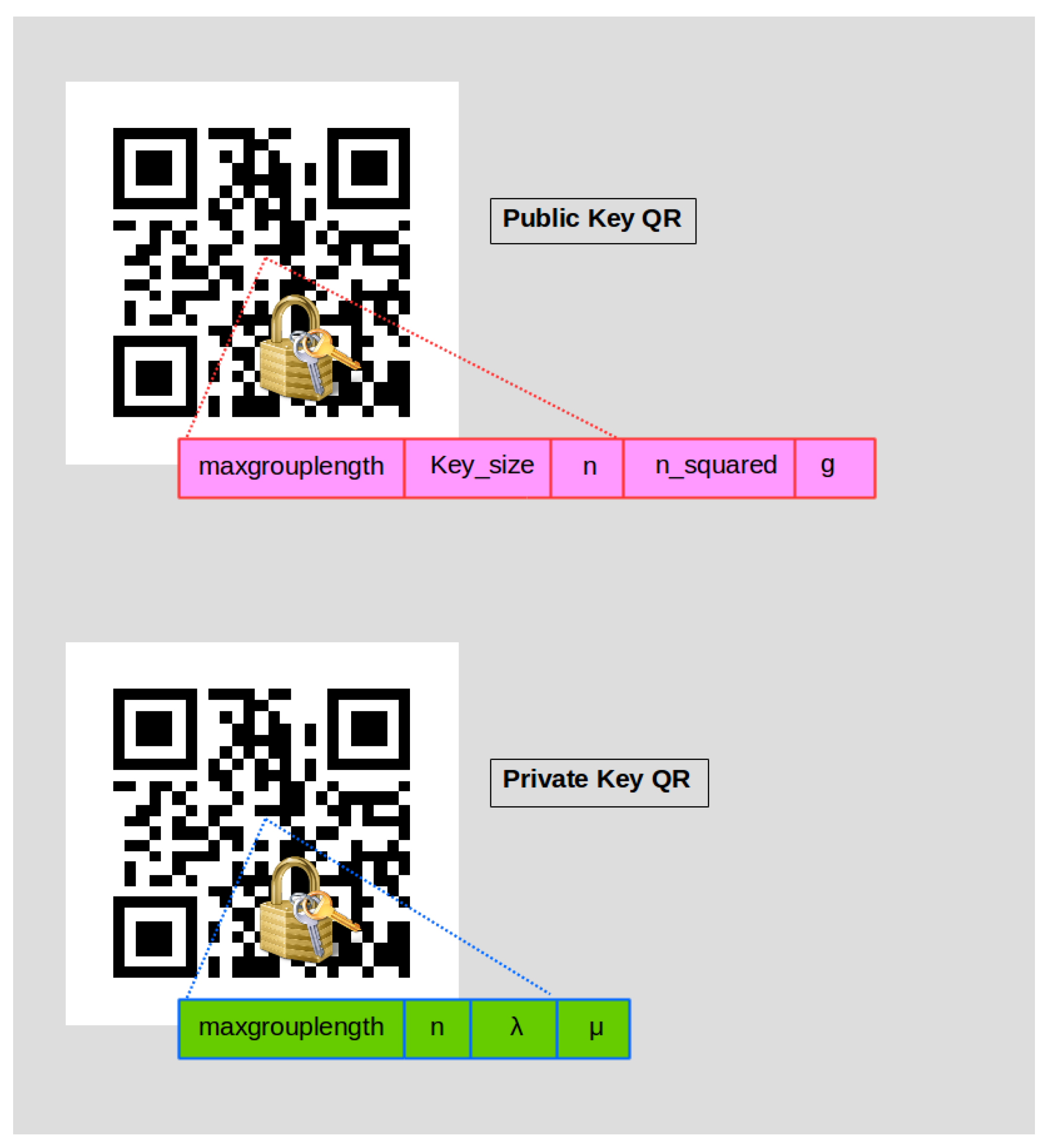

- The Key Server creates the Public (Encryption) Key QR in addition to the Private (Decryption) Key QR based on random prime numbers p and q, each time, for the Paillier cryptographic scheme.

- 3.

- The client-side application of PRIVocular reads the Public Key QR to generate the encryption parameters.

- 4.

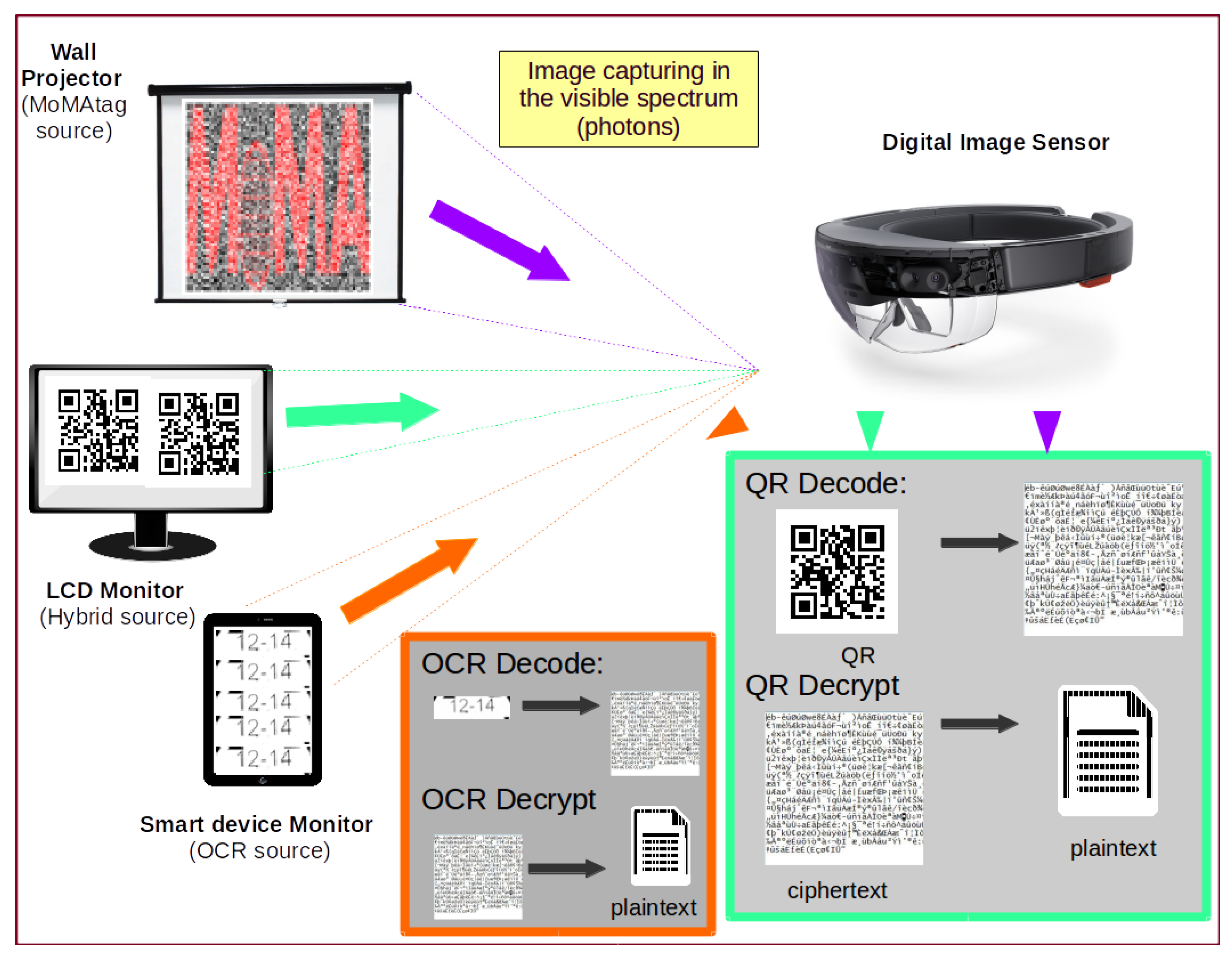

- The end-user then selects a visual encoding technique, or data representation method, among OCR, Hybrid, or MoMAtag from the software GUI.

- 5.

- The end-user can now start typing ASCII characters from the client application. Encryption is performed in stream mode (i.e., the ciphertext is produced per character typed on the on-the-fly).

- 6.

-

Through the Bluetooth communication interface, each character typed is sent to the prompting device screen via a Bluetooth (server) adapter. The previous implies that all PRIVocular devices should be paired via Bluetooth and become synchronized. Depending on the data encapsulation mode:

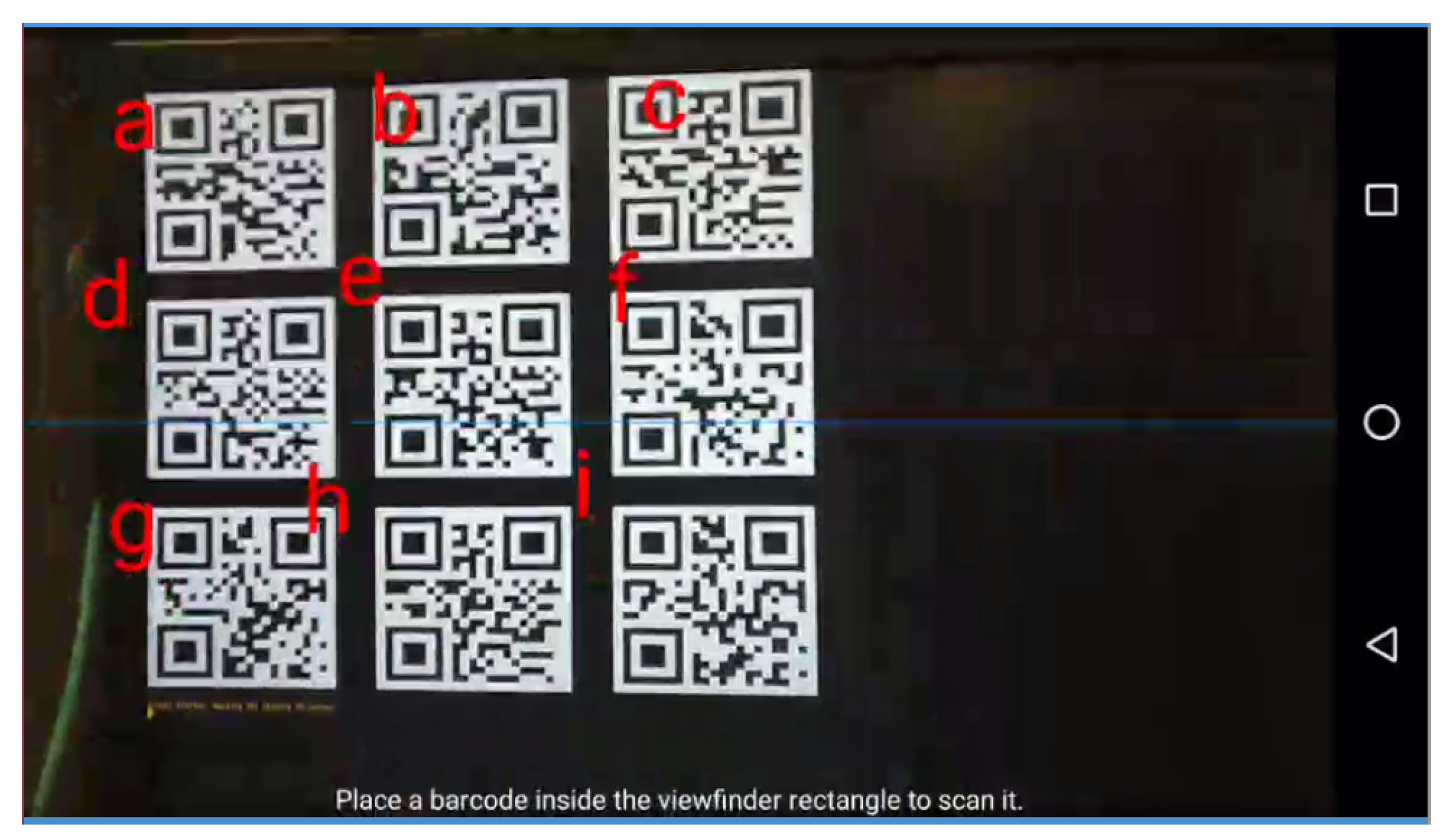

- Hybrid mode: Each time a character is typed, a QR code is shown on the prompting screen in a grid layout, with the corresponding ciphertext of the typed character as its content.

- MoMAtag mode: encryption is done in block mode, meaning after the user has typed an ASCII character, he/she will generate the MoMAtag with its ciphertext, a posteriori.

- 7.

- The server-side application of PRIVocular reads the Private Key QR by the same authenticated end-user to generate the decryption parameters.

- 8.

- The end-user will then select the applicable mode of operation, depending on his/her generated or encoded form of plaintext data.

- 9.

- The end-user, provided he/she has obtained the correct decryption key format, can now successfully decode and decrypt, thus reconstructing the original message on the smart device’s display.

3.4. PRIVocular Key Components

3.4.1. Key Generation and Distribution Server

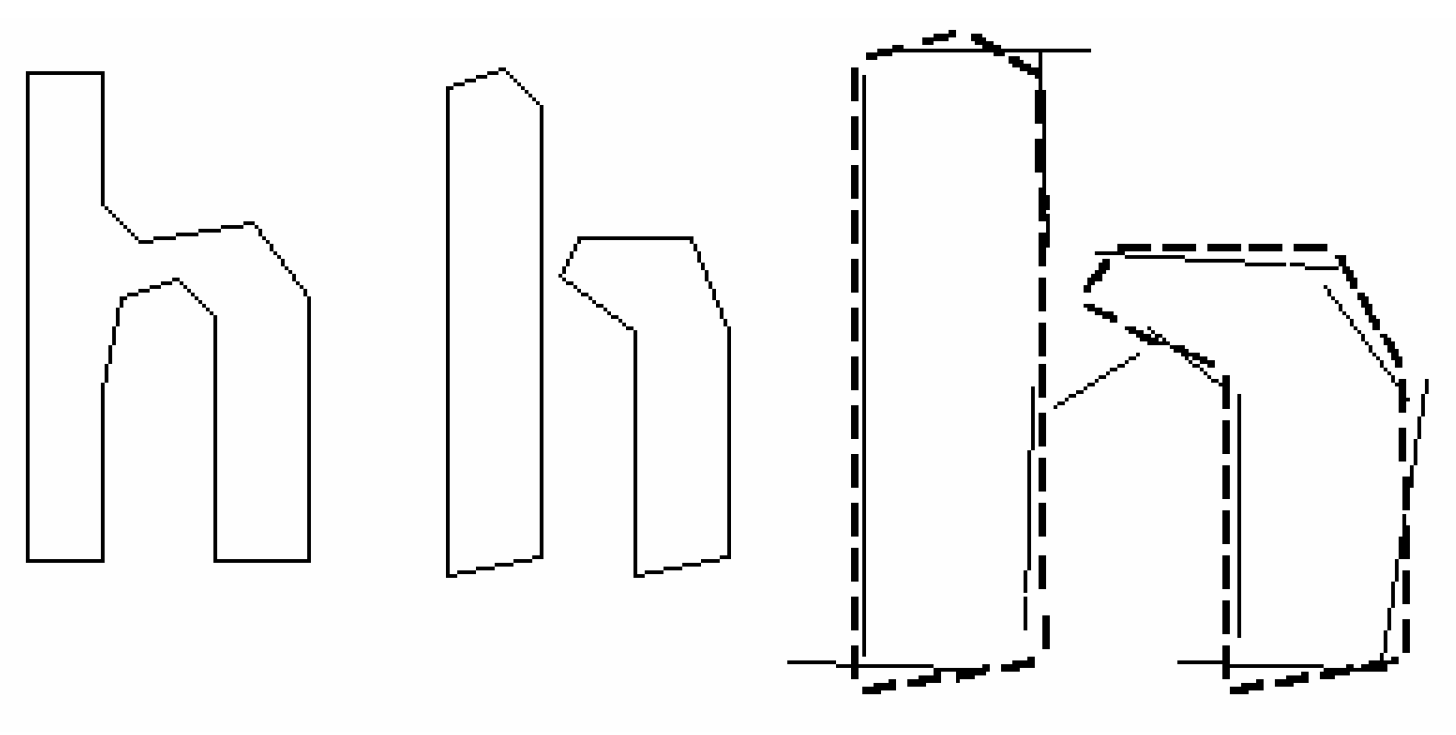

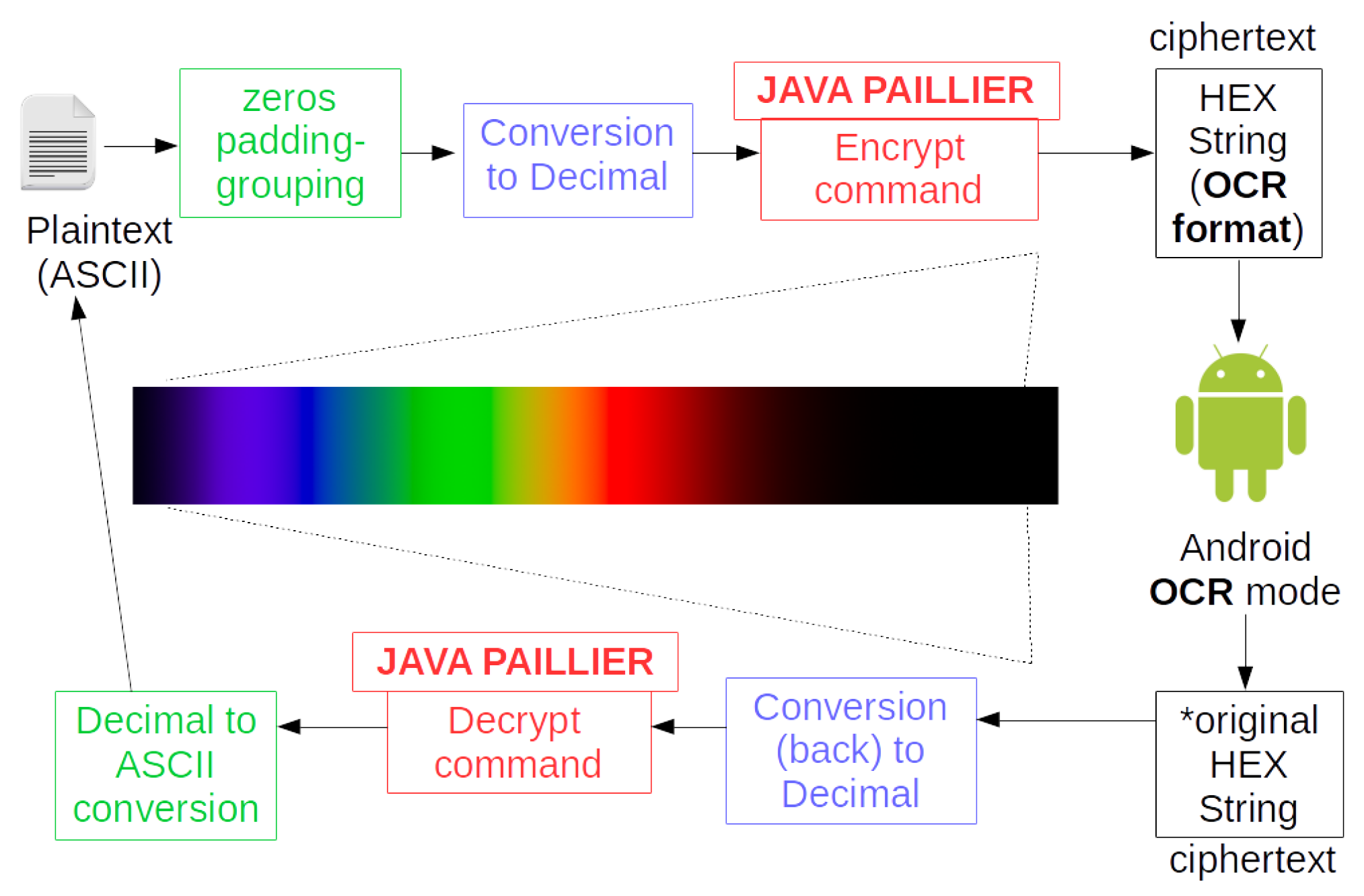

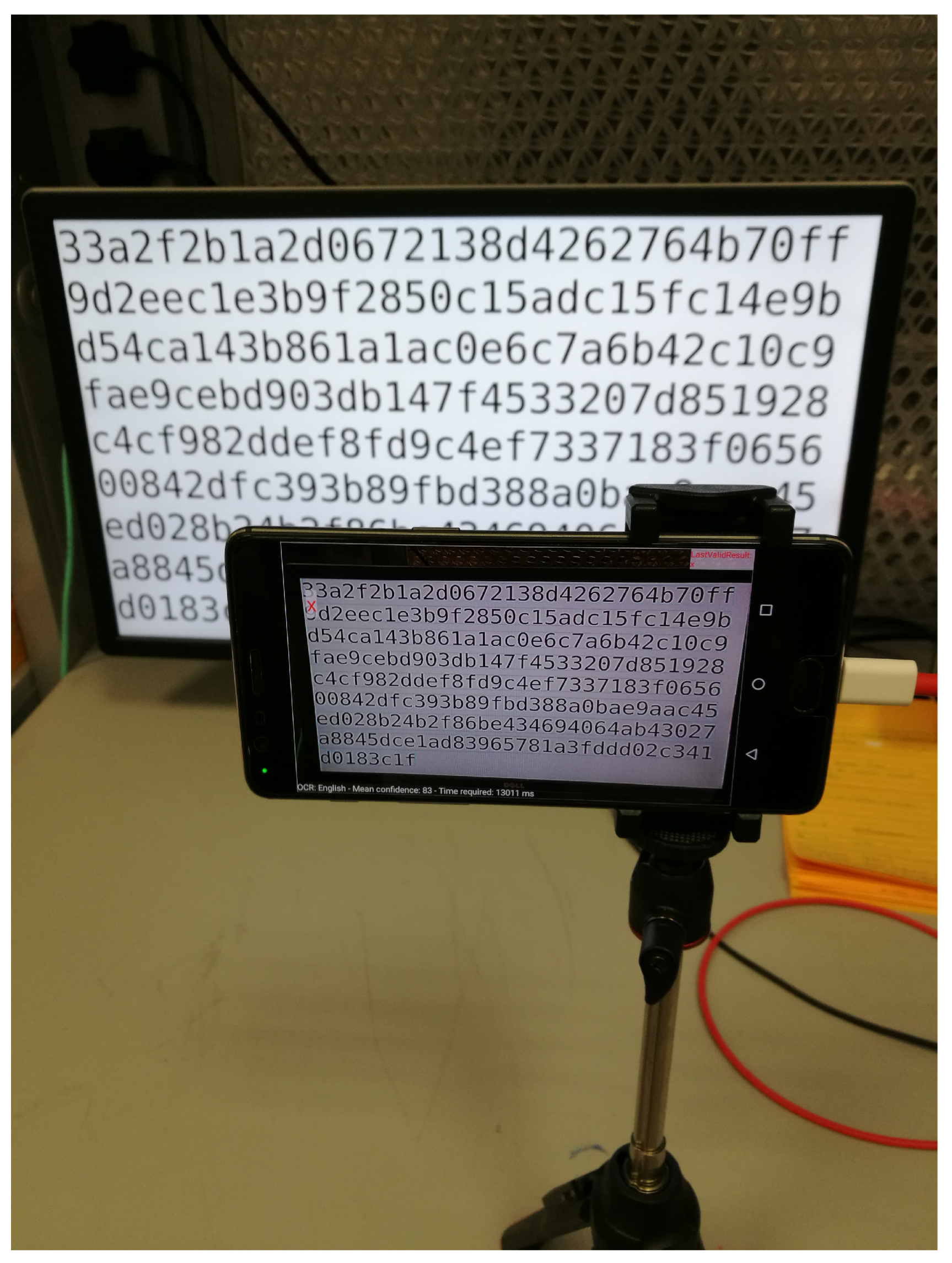

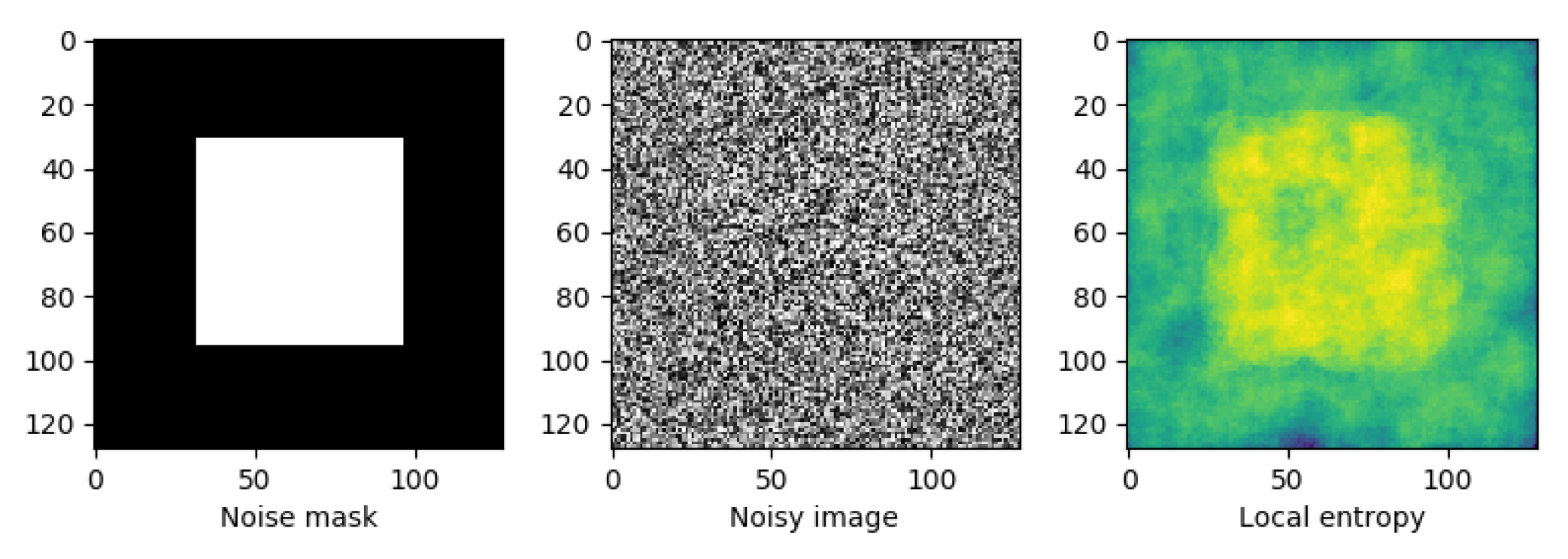

3.4.2. OCR

|

Algorithm 1: Encrypted OCR filter algorithm

|

|

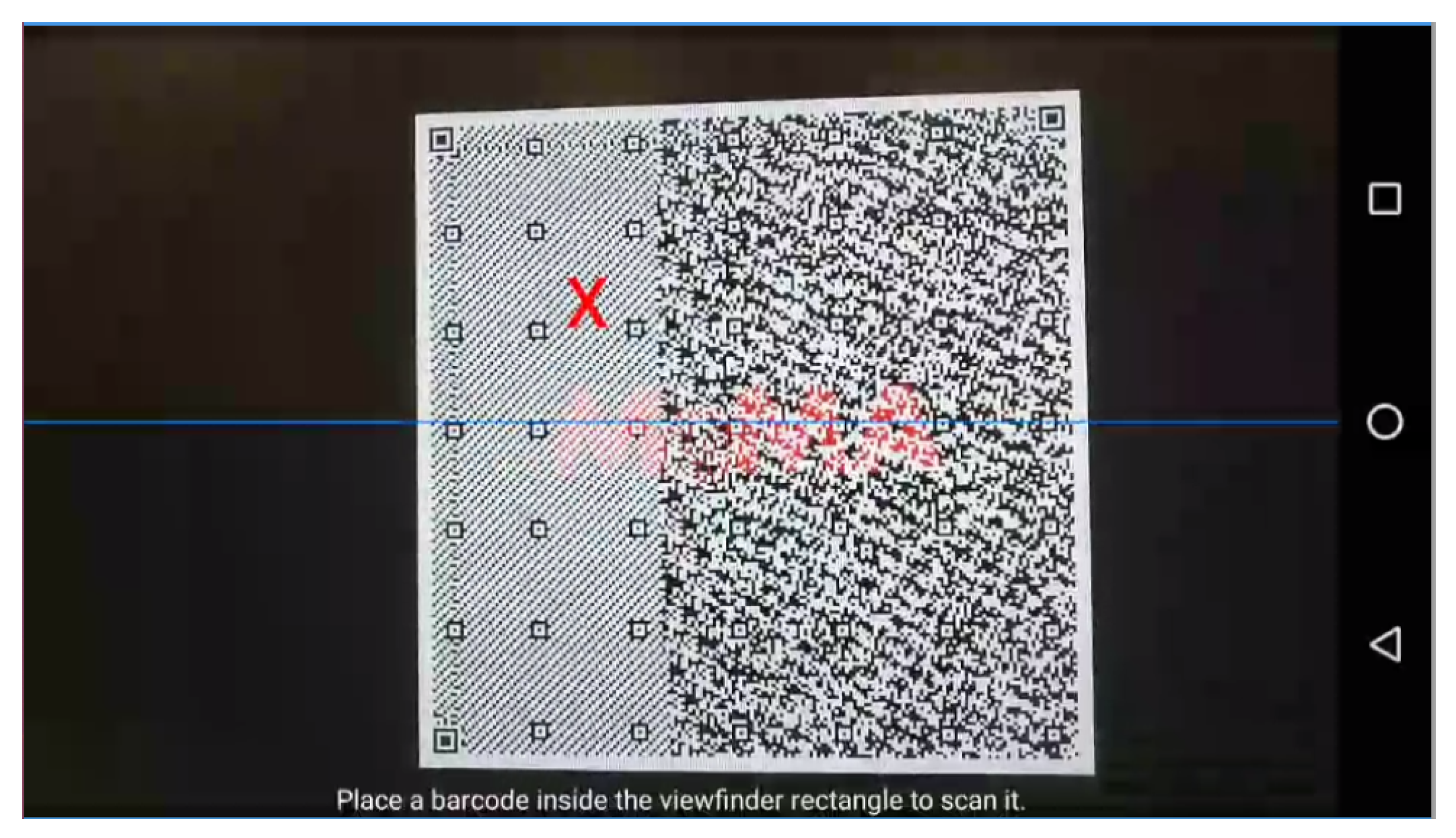

3.4.3. MoMAtag

3.4.4. Hybrid

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Analysis

- 1.

- QR Low. A low-resolution QR Tag (372x359 pixels)

- 2.

- Text/OCR. A medium resolution Text-on-Screen file (1084x584 pixels)

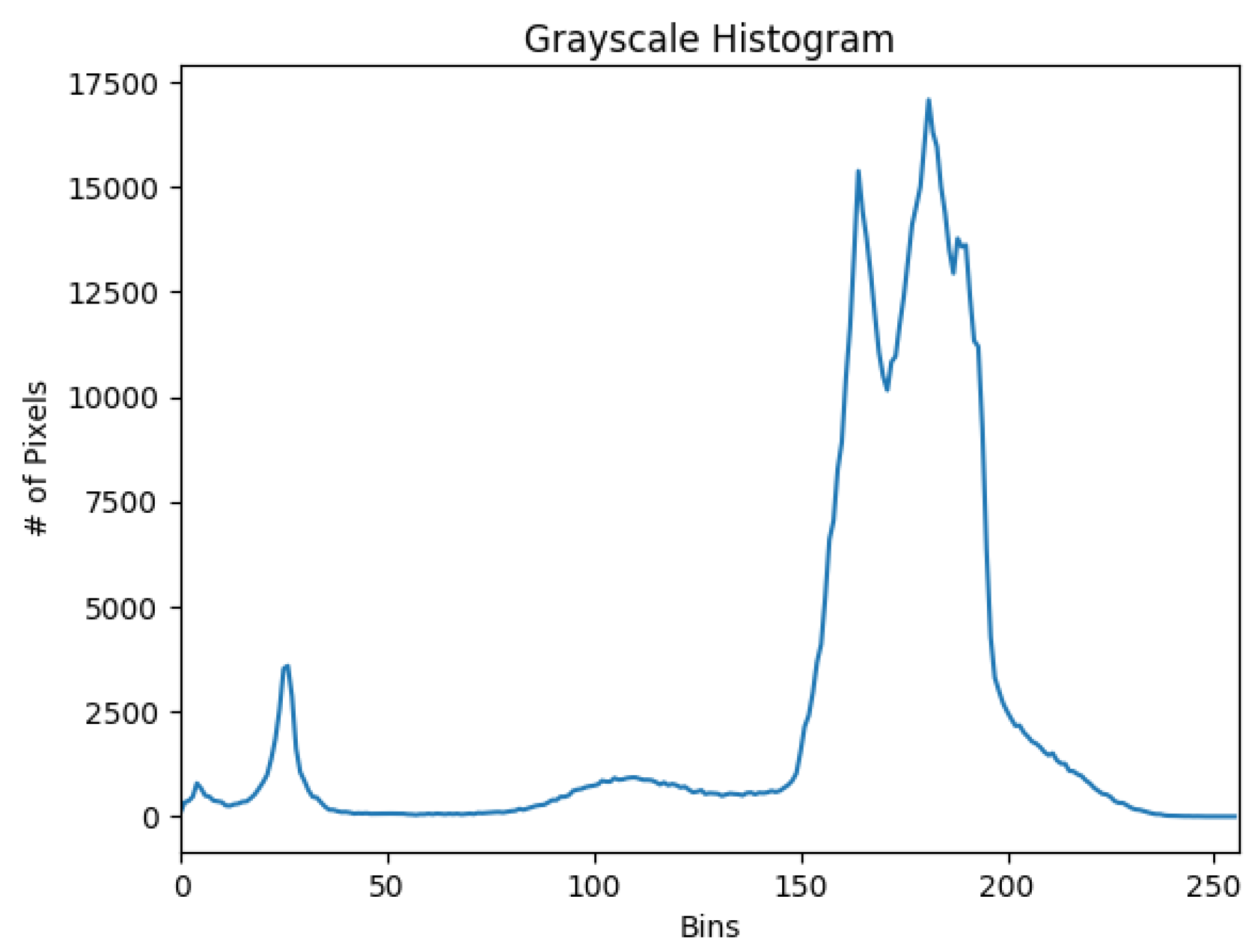

4.1.1. QR Low

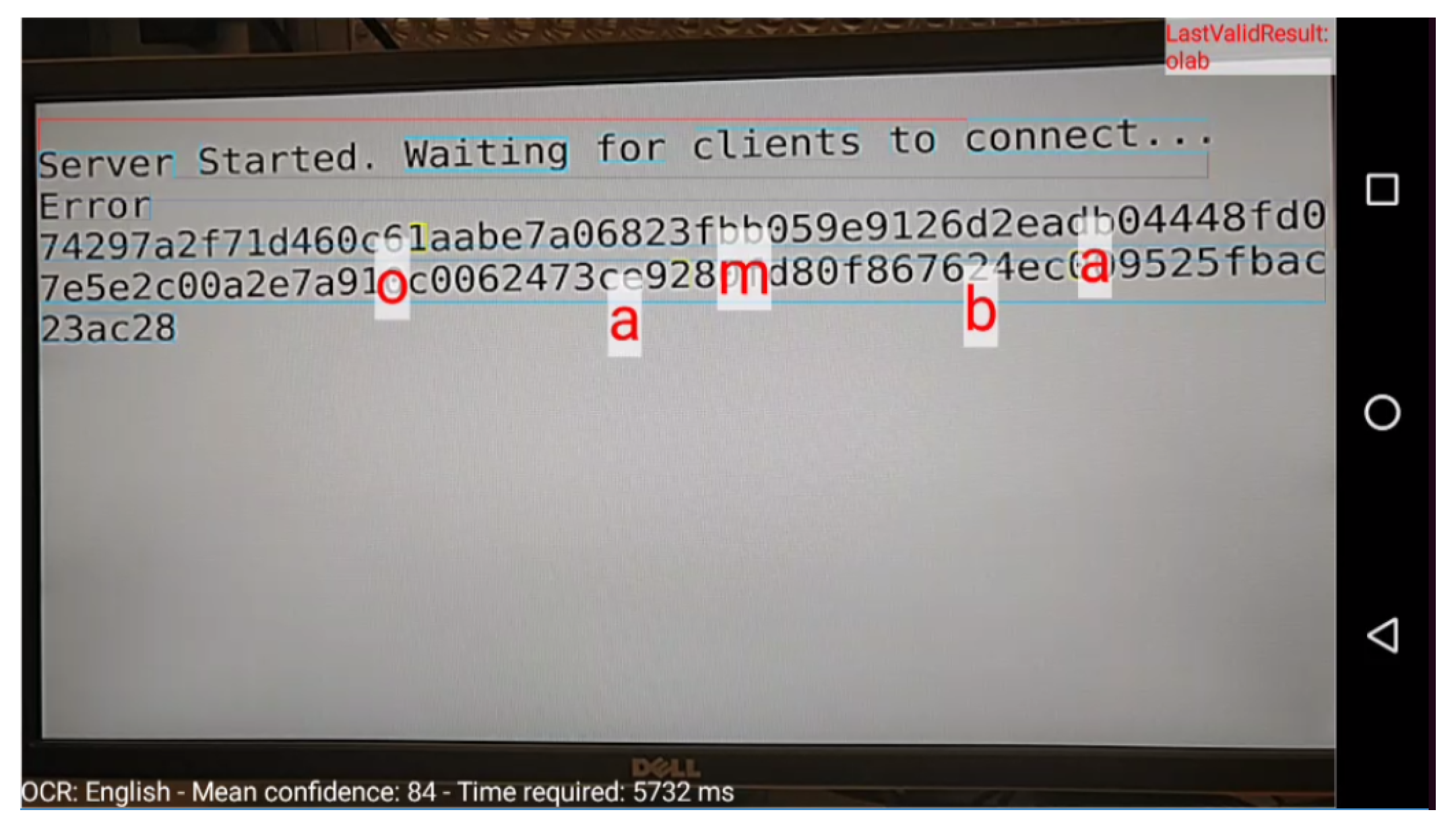

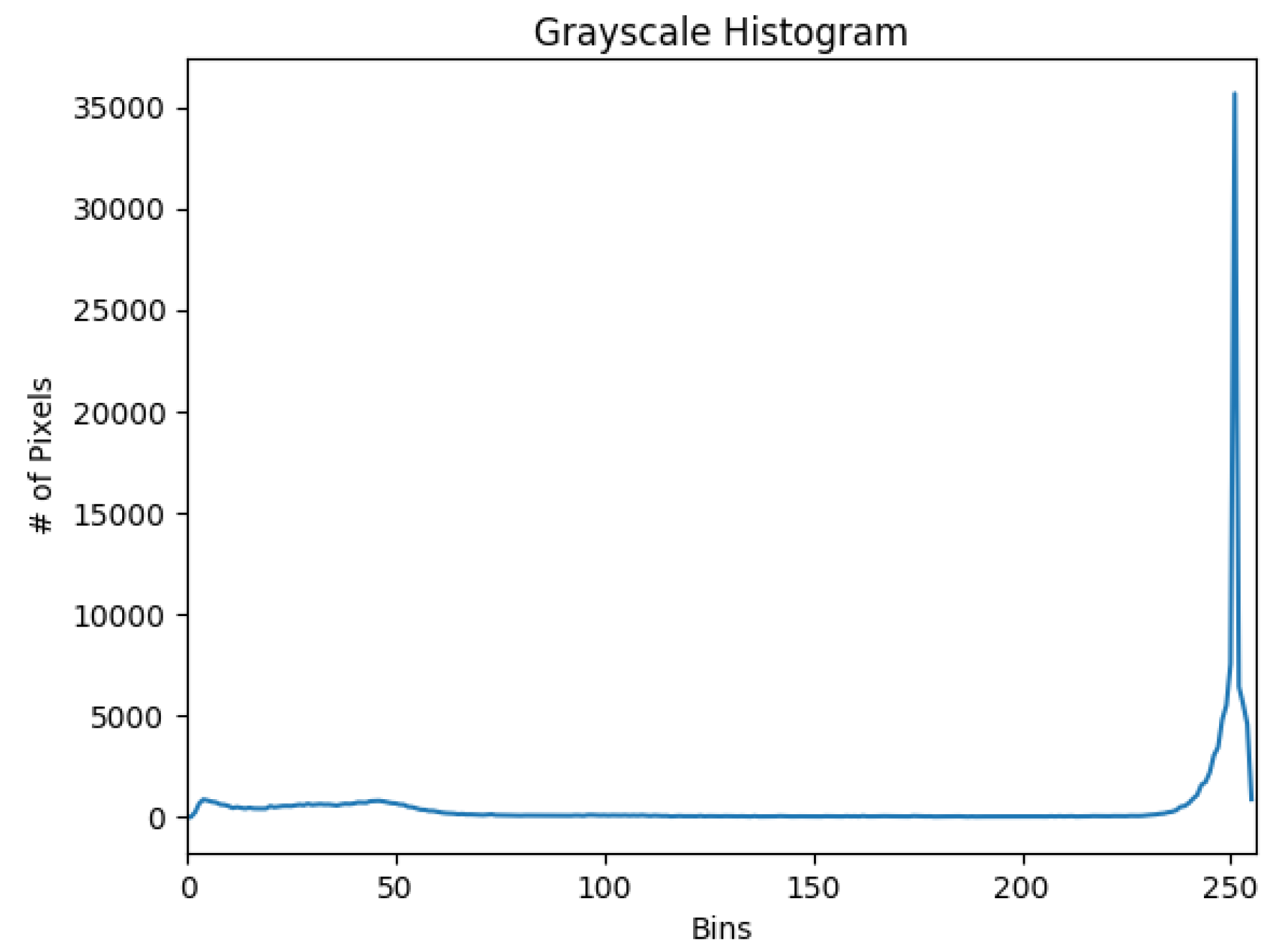

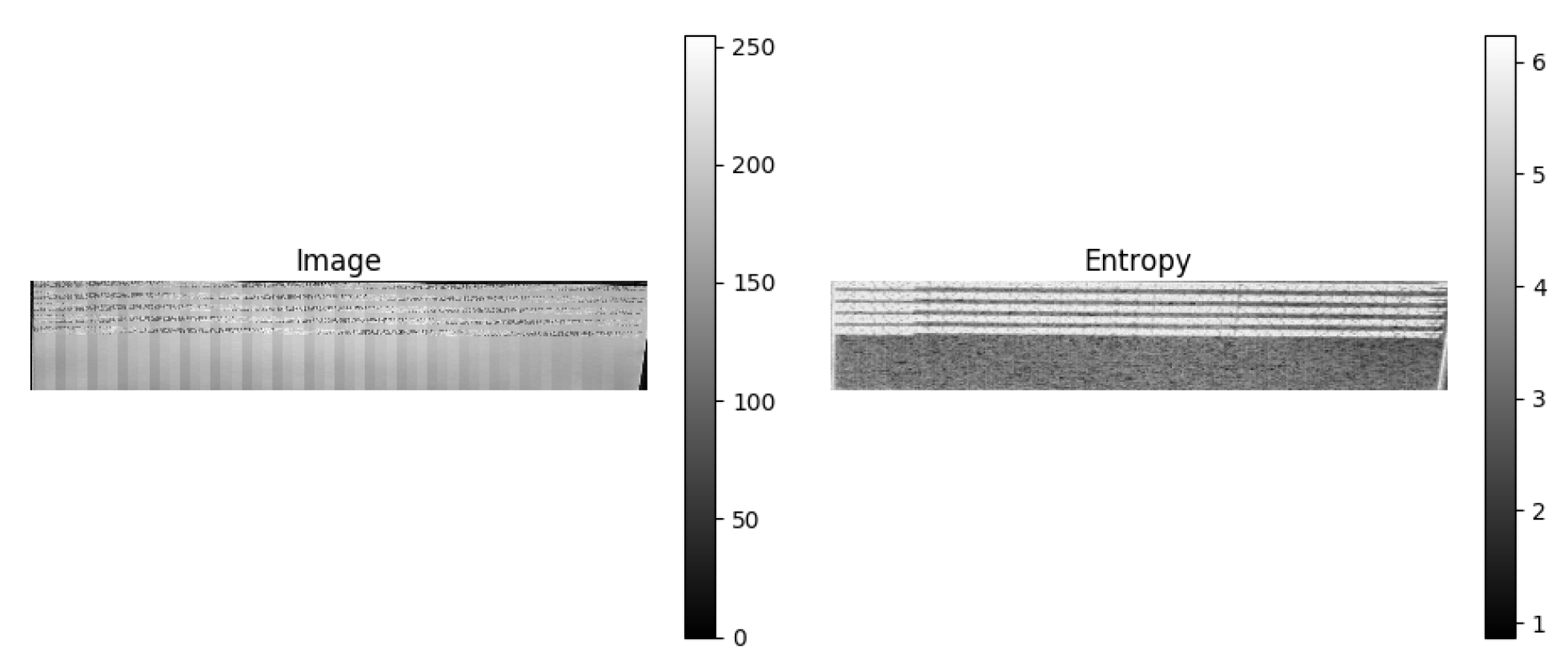

4.1.2. Text/OCR

4.2. Performance Evaluation of PRIVocular Framework

5. Conclusion and Future Work

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| OCR | Optical Character Recognition |

| QR | Quick Response Code |

| ECC | Error Correction Code |

References

- Simkin M., Schröder D., Bulling A., Fritz M. (2014) Ubic: Bridging the Gap between Digital Cryptography and the Physical World. In: Kutyłowski M., Vaidya J. (eds) Computer Security - ESORICS 2014. ESORICS 2014. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 8712. Springer, Cham.

- Reality 51 team managed by ukasz Rosiński, The Farm 51 Group S.A., Report on the current state of the VR market, 2015, http://thefarm51.com/ripress/VR_market_report_2015_The_Farm51.pdf.

- Paillier, Pascal, Public-Key Cryptosystems Based on Composite Degree Residuosity Classes, in EUROCRYPT 1999. Springer. pp. 223-238. [CrossRef]

- Holley, Rose, "How Good Can It Get? Analysing and Improving OCR Accuracy in Large Scale Historic Newspaper Digitisation Programs", in April 2009, D-Lib Magazine. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- From QR Code.com. Denso-Wave. Retrieved 23 May 2016, "QR Code Standardization", http://www.qrcode.com/en/about/standards.html.

- Guruswami, V.; Sudan, M. Guruswami, V.; Sudan, M., Improved decoding of Reed-Solomon codes and algebraic geometry codes, in IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 45 (6): 1757-1767. [CrossRef]

- R. Smith, An Overview of the Tesseract OCR Engine, in Ninth International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR 2007), Parana, 2007, pp. 629-633. [CrossRef]

- T. Mantoro, A. M. Sobri and W. Usino, Optical Character Recognition (OCR) Performance in Server-Based Mobile Environment, 2013 International Conference on Advanced Computer Science Applications and Technologies, Kuching, 2013, pp. 423-428. [CrossRef]

- Mande Shen and Hansheng Lei, Improving OCR performance with background image elimination, 2015 12th International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (FSKD), Zhangjiajie, 2015, pp. 1566-1570. [CrossRef]

- S. Ramiah, T. Y. Liong and M. Jayabalan, Detecting text based image with optical character recognition for English translation and speech using Android, 2015 IEEE Student Conference on Research and Development (SCOReD), Kuala Lumpur, 2015, pp. 272-277. [CrossRef]

- O. Mazonka, N. G. Tsoutsos and M. Maniatakos, Cryptoleq: A Heterogeneous Abstract Machine for Encrypted and Unencrypted Computation, in IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 11, no. 9, pp. 2123-2138, Sept. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Android Developers, https://developer.android.com/index.html.

- M. A. Sadikin and S. U. Sunaringtyas, Implementing digital signature for the secure electronic prescription using QR-code based on Android smartphone, in 2016 International Seminar on Application for Technology of Information and Communication (ISemantic), Semarang, 2016, pp. 306-311. [CrossRef]

- B. Rodrigues, A. Chaudhari and S. More, Two factor verification using QR-code: A unique authentication system for Android smartphone users, in 2nd International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I), Noida, 2016, pp. 457-462. [CrossRef]

- D. Jagodić, D. Vujiĉić and S. Ranđić, Android system for identification of objects based on QR code, in 2015 23rd Telecommunications Forum Telfor (TELFOR), Belgrade, 2015, pp. 922-925. [CrossRef]

- R. Divya and S. Muthukumarasamy, An impervious QR-based visual authentication protocols to prevent black-bag cryptanalysis, in 2015 IEEE 9th International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Control (ISCO), Coimbatore, 2015, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- D. Patil and S. K. Guru, Secured authentication using challenge-response and quick-response code for Android mobiles, in International Conference on Information Communication and Embedded Systems (ICICES2014), Chennai, 2014, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Bani-Hani, Y. A. Wahsheh and M. B. Al-Sarhan, Secure QR code system, in 2014 10th International Conference on Innovations in Information Technology (IIT), Al Ain, 2014, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- S. Dey, S. Agarwal and A. Nath, Confidential Encrypted Data Hiding and Retrieval Using QR Authentication System, in 2013 International Conference on Communication Systems and Network Technologies, Gwalior, 2013, pp. 512-517. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Massandy and I. R. Munir, Secured video streaming development on smartphones with Android platform, in 2012 7th International Conference on Telecommunication Systems, Services, and Applications (TSSA), Bali, 2012, pp. 339-344. [CrossRef]

- Z. Bálint, B. Kiss, B. Magyari and K. Simon, Augmented reality and image recognition based framework for treasure hunt games, in 2012 IEEE 10th Jubilee International Symposium on Intelligent Systems and Informatics, Subotica, 2012, pp. 147-152. [CrossRef]

- GitHub qrcode-terminal, https://github.com/gtanner/qrcode-terminal.

- J. Kanai, T. A. Nartker, S. Rice and G. Nagy, Performance metrics for document understanding systems, in Document Analysis and Recognition, 1993., Proceedings of the Second International Conference on, Tsukuba Science City, 1993, pp. 424-427. [CrossRef]

- Official ZXing ("Zebra Crossing") project home, https://github.com/zxing/zxing.

- Jana, S., Narayanan, A., Shmatikov, V.: A scanner darkly: Protecting user privacy from perceptual applications. In: IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, pp. 349-363. IEEE Computer Society (2013).

- Starnberger, G., Froihofer, L., Goeschka, K.M.: Qr-tan: Secure mobile transaction authentication. In: 2012 Seventh International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, pp. 578-583 (2009).

- Gao, Y. (2015). Secure Key Exchange Protocol based on Virtual Proof of Reality. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch., 2015, 524.

- Du, R. , Lee, E., & Varshney, A. (2019). Tracking-Tolerant Visual Cryptography. 2019 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), 902-903.

- Park, S., & Kim, Y. (2022). A Metaverse: Taxonomy, Components, Applications, and Open Challenges. IEEE Access, 10, 4209-4251.

- Canbay, Y. , Utku, A., & Canbay, P. (2022). Privacy Concerns and Measures in Metaverse: A Review. 2022 15th International Conference on Information Security and Cryptography (ISCTURKEY), 80-85.

- Ravi, R.V. , Dutta, P.K., & Roy, S. (2023). Color Image Cryptography Using Block and Pixel-Wise Permutations with 3D Chaotic Diffusion in Metaverse. International Conferences on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision.

- De Lorenzis, F. , Visconti, A., Marani, M., Prifti, E., Andiloro, C., Cannavo, A., & Lamberti, F. (2023). 3DK-Reate: Create Your Own 3D Key for Distributed Authentication in the Metaverse. 2023 IEEE Gaming, Entertainment, and Media Conference (GEM), 1-6.

| 1 | While the framework is built on the Paillier cryptosystem due to earlier work of the authors in [11], the framework can be used with any underlying cryptographic scheme. |

| QR | MoMAtag | |

|---|---|---|

| ECC Level: | Level H (High) | Level H (High) |

| Data encoding format: | binary/byte | binary/byte |

| bits/char: | 8 | 8 |

| max. characters: | 1,273 | 2,049 |

| EC Code Words Per Block: | 30 | 30 |

| Block 1 Count: | 20 | 1 |

| Block 1 Data Code Words: | 15 | 2334 |

| Block 2 Count: | 61 | 0 |

| Block 1 Data Code Words: | 16 | 0 |

| Input Mode | Num. of elements | Max. characters | Bits/char. | Encoding | Square Pixels Per Element | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCR | 1200 | 600 | 8 | HEX/byte | 1683 | 45cm |

| MoMAtag | 2048 | 1024 | 8 | Binary/byte | 1176120 | 60cm |

| Hybrid | 640 | 320 | 8 | Binary/byte | 49163 | 100cm |

| Key Size (bits) | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | 2048 | 4096 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Num. of recognized elements (ASCII) | 47 | 22 | 9 | 4 | 1 | NA | NA | NA |

| Max. characters (HEX) | 752 | 704 | 576 | 512 | 256 | NA | NA | NA |

| Square Pixels Per Element Character (pixels) | 2184 | 2184 | 2184 | 2184 | 5332 | NA | NA | NA |

| Physical Distance (cm) | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | NA | NA | NA |

| Mean confidence | 75 | 84 | 85 | 81 | 91 | NA | NA | NA |

| Time Required (msec) | 30730 | 30137 | 22450 | 20825 | 13954 | NA | NA | NA |

| Key Size (bits) | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | 2048 | 4096 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Num. of recognized elements (ASCII) | 24 | 18 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Max. characters (HEX) | 384 | 576 | 512 | 768 | 768 | 1024 | 2048 | 2048 |

| Square Pixels Per Element Character (pixels) | 54756 | 74529 | 125316 | 190096 | 351649 | 625681 | 447561 | 2190400 |

| Physical Distance (cm) | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 |

| Mean confidence | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Time Required (msec) | 2140 | 1040 | 720 | 870 | 800 | 860 | 940 | 3500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).