1. Introduction

Hip arthroplasty, one of the world’s most frequently performed orthopedic procedures, requires high intraoperative hemodynamic management for safe patient care and optimal outcomes. The anesthetic technique and pharmacologic interventions during the surgery are among the factors affecting the millions’ intraoperative stability. Hip arthroplasty frequently requires spinal anesthesia owing to its effectiveness in pain management and favorable safety profile and is accompanied by a well-documented risk of hypotension. Such counteracting of anesthesia-induced vasodilation and the requirement of adjunct vasopressor agents such as Ephedrine for adequate perfusion is a requisite of this challenge [

1].

Ephedrine is an important ingredient in the frontline treatment of intraoperative hypotension, a mixed α- and β-adrenergic agonist that increases cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance [

2]. Although widely used, the interaction between ephedrine efficacy and the use of specific spinal anesthetics has received little attention. In addition, patients undergoing hip arthroplasty are frequently already living with chronic disease, most notably hypertension. Vascular remodeling and alterations in autonomic reflexes may modify the responsiveness to vasopressor agents in chronic hypertension [

3]. Understanding this (nuanced) relationship between chronic hypertension and intraoperative ephedrine requirements is an area of increasing clinical interest as the insight into this interaction may further advance perioperative management with a goal of more definitive and effective management.

This context provides scrutiny to the role of spinal anesthesia combinations (local anesthetics and adjuvants such as opioids or vasoconstrictors). Such combinations affect the degree and duration of sympathetic blockades used during surgery and, as such, the hemodynamic profile during surgery. As an example, the long-acting local anesthetic bupivacaine is one of the most used drugs for spinal anesthesia for hip arthroplasty, combined with adjuvants such as fentanyl or morphine to lengthen the effect and enhance analgesia [

4]. Although such combinations may worsen hypotension, they may affect the hemodynamic response to vasopressors. The selection of anesthesia protocols that minimize complications and improve patient outcomes depends on understanding these dynamics.

Spinal anesthesia’s most important hemodynamic effects are caused by sympathetic blockades leading to vasodilation, reduced venous return, and hypotension [

5]. Because they are particularly pronounced in older adults and most patients undergoing hip arthroplasty, these effects have been studied extensively in older adults. The risk is also compounded by age-related changes such as diminished cardiovascular reserve and impaired baroreceptor sensitivity. The mere complication of hypotension during surgery should not be considered a manageable inconvenience; instead, it has been linked with increased risk for myocardial ischemia, renal injury, and cognitive dysfunction, especially in vulnerable populations [

6].

To mitigate these risks, clinicians use vasopressors like Ephedrine, phenylephrine, or norepinephrine. Due to its dual mechanism of action (direct adrenergic receptor activation and indirectly by release of endogenously released catecholamine), Ephedrine is a versatile option [

7]. Ephedrine is effective and safe, but the effectiveness and safety vary significantly from one patient to the next, often with preexisting conditions such as hypertension [

8].

Chronic hypertension is a common comorbidity among patients undergoing hip arthroplasty, and implications for intraoperative management are significant. Structural [

9] and functional [

11] cardiovascular system changes occur with the chronic elevation of blood pressure, including increased arterial stiffness, left ventricular hypertrophy, and downregulation of adrenergic receptors. These changes can decrease the efficacy of vasopressors like Ephedrine, leading to the need for higher doses or alternate approaches to stabilize hemodynamics. In addition, most of these patients also use other antihypertensive medications commonly, such as beta-blockers or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, which may interact with intraoperative drugs, making management even more complex [

10].

Of interest, chronic hypertension may also affect the baseline autonomic tone and sympathetic response to anesthesia. Hypertensive patients who undergo spinal anesthesia may experience more profound hypotension because of the blunted compensatory response [

11]. This phenomenon emphasizes the importance of individualized vasopressor therapy and the necessity of research on differential vasopressor effects in this population.

Further, intraoperative hemodynamics are critically determined by the choice of spinal anesthesia agents and their combinations beyond patient-specific factors like chronic hypertension. Like other local anesthetics such as bupivacaine, ropivacaine, and lidocaine, they differ in potency, duration of action, and cardiotoxicity profiles [

12]. The addition of adjuvants such as fentanyl or morphine may augment analgesia and impair sympathectomy, which may influence vasopressor needs [

13].

Opioid adjuvants such as fentanyl have opioid actions on spinal μ receptors to provide synergistic analgesia with little increase in motor blockade. Despite their predictable effects on central hemodynamics, particularly heart rate and blood pressure, their effects on systemic hemodynamics, such as changes in heart rate or blood pressure, are less predictable and depend on the dose and patient factors. The use of another commonly used opioid adjuvant, morphine, results in the same μ receptor mode of analgesia, yet with a greater risk of delayed respiratory depression and nausea. Morphine has mild hemodynamic effects and usually transient hypotension due to the release of histamine from higher doses. Spinal anesthesia needs to be optimized on an individual patient level [

14].

The emerging concept of personalized perioperative care combines individual patient characteristics like genetic information together with medical conditions along with immediate physiological data to optimize anesthetic treatments. Identifying the effects of chronic hypertension coupled with patient age and distinct spinal anesthesia combinations on hemodynamic stability enables providers to customize vasopressor therapy. The precision medicine approach involving pharmacogenomic profiling enables healthcare providers to predict how patients will respond to vasopressors such as ephedrine thus aiding protocol optimization. The research aims to advance personalized anesthesia by establishing important patient-related variables which impact both intraoperative hemodynamic stability and ephedrine responsiveness in hip arthroplasty patients.

2. Materials and Methods

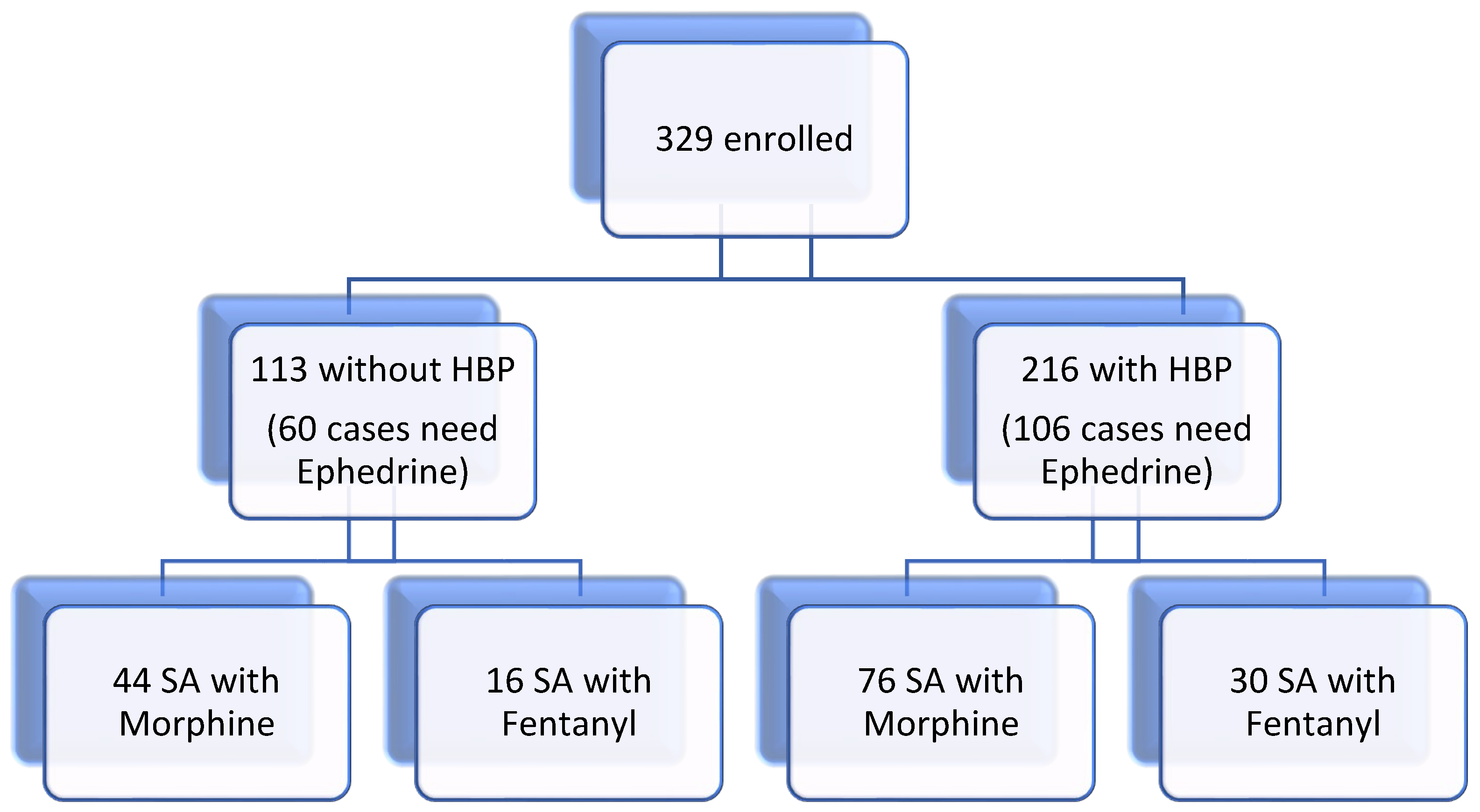

We conducted a study involving 329 patients over the age of 18 scheduled for orthopedic hip arthroplasty surgery under spinal anesthesia (SA). Each patient provided written informed consent as required by our hospital. This retrospective study was meticulously reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Pelican Hospital Oradea (approval number 2591/15.12.2021) and was performed in accordance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Exclusion criteria: any contraindications for SA, including age under 18, history of revision surgery, patients with special devices due to severe instability, hemodynamic instability, and refusing participation in this study.

The pre-anesthetic evaluation of the patients was scheduled two weeks before surgery.Patients were hospitalized the day before the hip arthroplasty. The only antihypertensive medication administered on the day of the surgery was the β-blockers. Alprazolam 0.5 mg was given one night before surgery for anxiety decreased. In the operating room, an 18G IV cannula was secured, and Ringer lactate solution (15 ml/kg) was infused. The premedication process was carried out with care, using appropriate medications such as 2 mg midazolam and 1g tranexamic acid. The patients were positioned in a sitting posture following skin disinfection and 1% lidocaine infiltration, and using the paramedian approach with a 26G Sprotte needle (PAJUNK, GmbH, Geisingen, Germany), we performed lumbar puncture at the L3–L4 interspace.

Our study involved the injection of hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% (doses between 15 mg and 17.5 mg) with a standard dose of 25 mg fentanyl or a standard dose of 150 μg morphine within 15 s. Subsequently, oxygen (5 L/min) was delivered with a face mask. Five minutes after intrathecal injection, a sensory blockade of spinal anesthesia was installed. The group was then divided into two based on the type of SA: bupivacaine with morphine (group M) and bupivacaine with fentanyl (group F). The sensory block from spinal anesthesia was evaluated five minutes later using ice cubes or pinpricks.

After placing the patient in the dorsal decubitus position, we recorded ECG, noninvasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry (SpO2), and respiratory rates throughout the surgery period.

The protocol for rescue treatment in the event of hemodynamic instability included:

1. Severe hypotension (decrease of systolic blood pressure for more than 30% from baseline, or systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg): additional ephedrine boluses of 5 mg repeated in 5 min with an additional infusion of Ringer solution.

2. Bradycardia (≤50 beats per minute): bolus of atropine 0.5 mg, repeated if needed in 1 min until heart rate frequency is more than 50 beats per minute or an overall amount of 2 mg atropine is reached.

Statistics

Statistical data were processed with IBM SPSS version 23. The chi-squared statistical test was applied to check the statistical significance of the association between the categorical variables (age and hypertension). We used Eta squared measures for the proportion of the total variance in a dependent variable (Ephedrine) associated with the membership of different groups (group M, group F).

3. Results

We studied 329 patients scheduled for orthopedic hip arthroplasty surgery under SA and the required intraoperative ephedrine dose for hemodynamic patient stabilization (

Table 1).

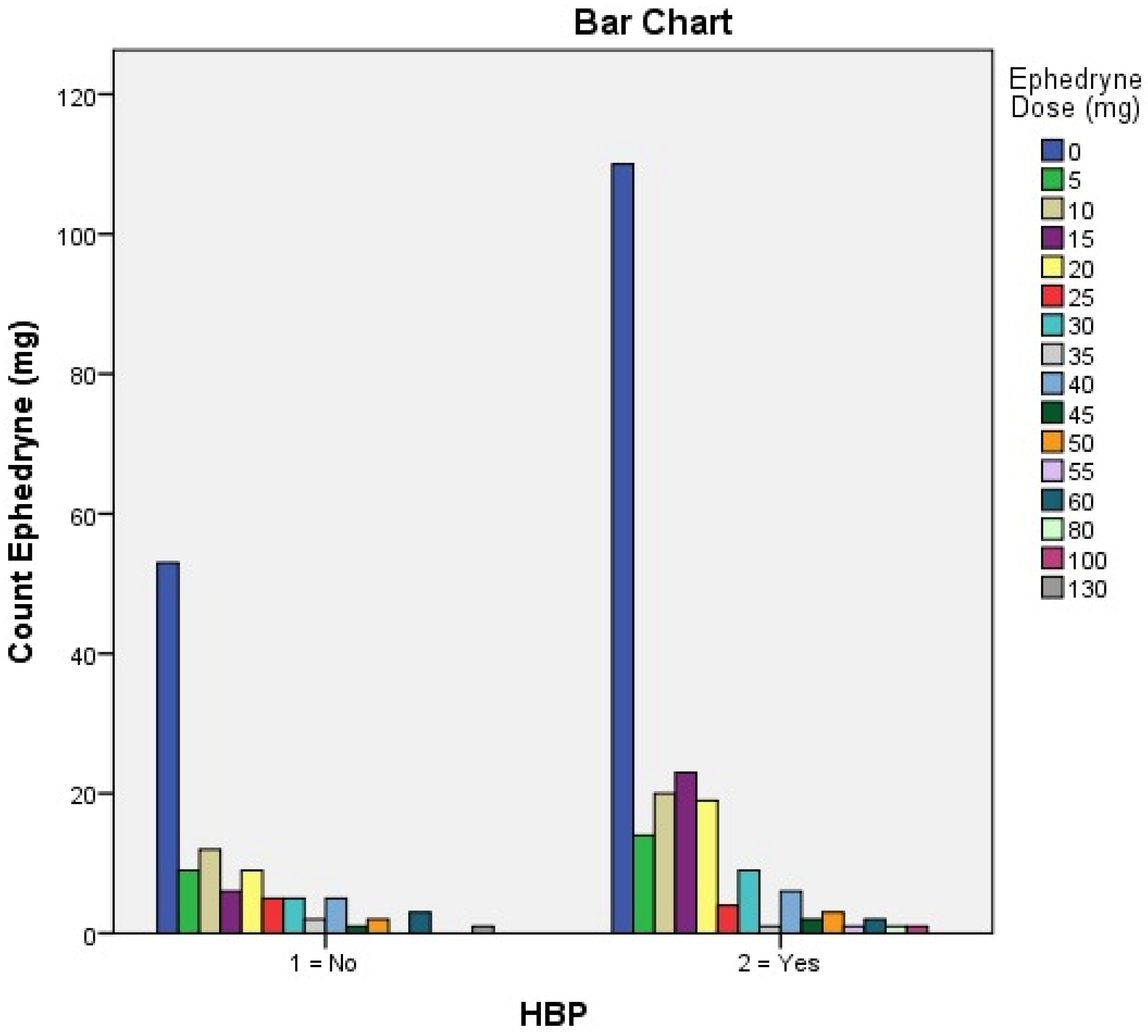

This table explains the percentage of ephedrine doses relative to the total number of patients enrolled in this study with or without blood hypertensive pathology. As shown in the table above, two groups of hypertensive versus non-hypertensive patients are distributed as in the flowchart (

Figure 1). The most used dose of Ephedrine for intraoperative hemodynamic balancing was 10 mg (12 cases of patients without HBP and 20 cases with HBP), respectively, and 15 mg of Ephedrine (6 cases without HBP and 23 cases with HBP).

As we can see in

Table 2, in the case of patients with normal blood pressure, the administration of Ephedrine was necessary in 60 cases (53,1%), and in the case of hypertensive patients, it was necessary in 106 cases (49,1%), a fact that demonstrates there is no statistically significant difference between the two groups.

Following the ETA analysis of the data, we observe that in 19 % of the cases, HBP is correlated with the amount of ephedrine dose, which is a value with practical significance.

Figure 2.

Number of patients with or without HBP correlated with ephedrine dose.

Figure 2.

Number of patients with or without HBP correlated with ephedrine dose.

Figure 2 shows that in 53 patients without HBP and 110 patients with HBP, the use of Ephedrine during the intervention was not necessary.

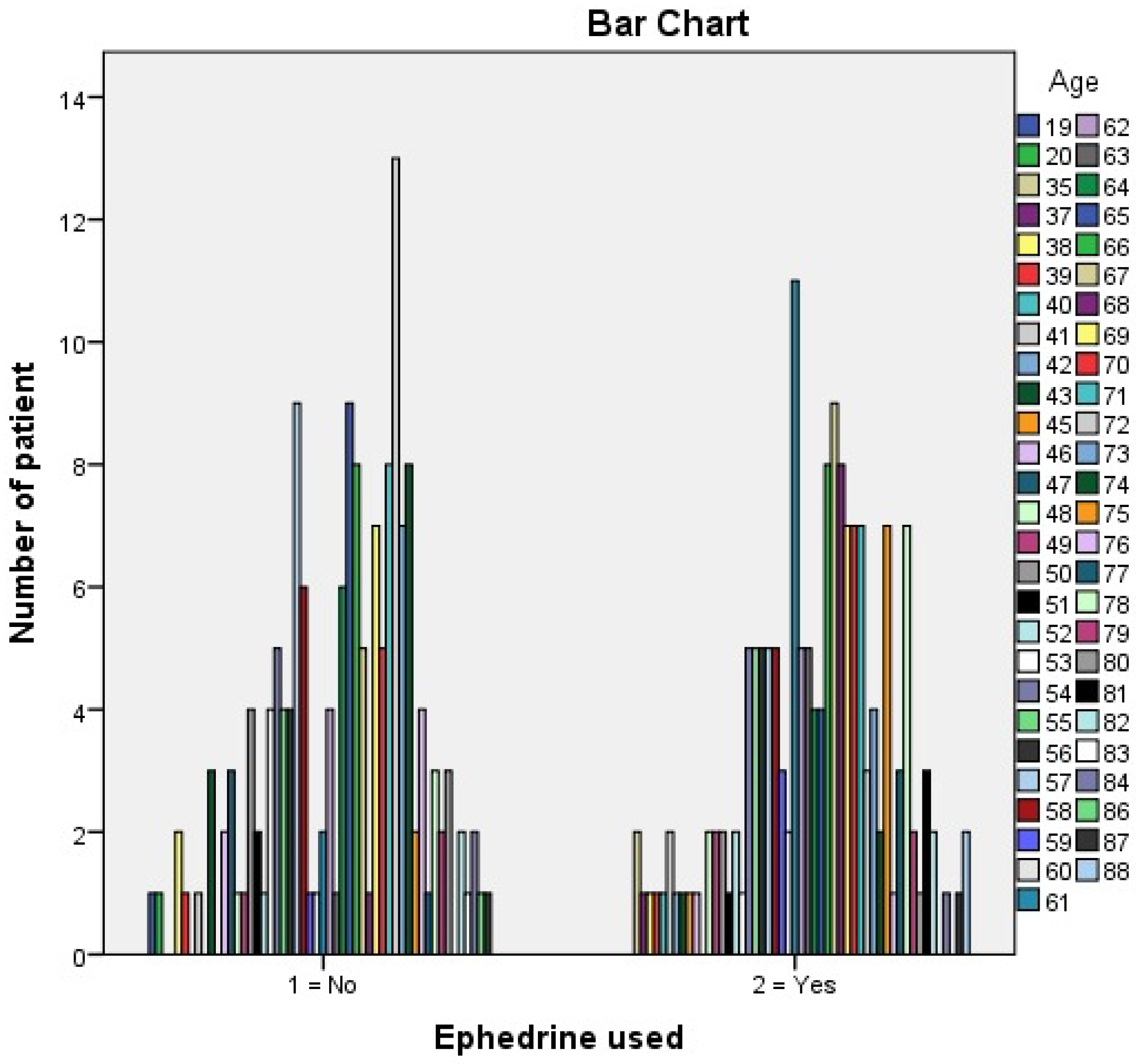

Following ETA data analysis, we conclude that age correlates with the dose of Ephedrine used.

Figure 3.

The age of patients correlated with the Ephedrine used.

Figure 3.

The age of patients correlated with the Ephedrine used.

As we observe, in 44.1% of cases, the use of Ephedrine is correlated with the age of the patient, which is a value with practical significance.

We studied 329 patients scheduled for orthopedic hip arthroplasty surgery under SA with morphine and bupivacaine versus SA with fentanyl and bupivacaine, and we compared the required intraoperative ephedrine use for hemodynamic patient stabilization (

Table 3).

As we can see in

Table 3, in the case of FSA, the administration of Ephedrine was necessary in 46 cases (50.5%), and in the case of MSA, it was necessary in 120 cases (50.4%), a fact that demonstrates there is no significant difference in percentage.

Table 4.

Chi-Square Tests for FSA and MSA compare to the use of Ephedrine.

Table 4.

Chi-Square Tests for FSA and MSA compare to the use of Ephedrine.

| Chi-Square Tests |

| |

Value |

df |

Asymptotic Significance (2-sided) |

Exact Sig. (2-sided) |

Exact Sig. (1-sided) |

| Pearson Chi-Square |

,000a

|

1 |

,983 |

|

|

| Continuity Correction |

,000 |

1 |

1,000 |

|

|

| Likelihood Ratio |

,000 |

1 |

,983 |

|

|

| Fisher’s Exact Test |

|

|

|

1,000 |

,541 |

| Linear-by-Linear Association |

,000 |

1 |

,983 |

|

|

| N of Valid Cases |

329 |

|

|

|

|

| a. 0 cells (.0%) have an expected count of less than 5. The minimum expected count is 45.09. |

| b. Computed only for a 2x2 table |

In the statistical study carried out using the Chi-Square Test, we wanted to see if there is a statistically significant difference between the need to use Ephedrine and the type of anesthesia. The values obtained demonstrate their independence (Pearson Chi-Square=0.983, Fisher’s Exact Test=1, Likelihood Ratio=0.983).

4. Discussion

Spinal anesthesia is a common technique as it is accessible, safe, and easy to perform. Before the surgery, every patient was informed regarding the details of the surgery approach and possible intraoperative hemodynamic variations induced by SA. For optimal surgical anesthesia, a local anesthetic agent can induce adequate relaxation of the lower leg muscles. By combining opioids with bupivacaine, a decrease in the local anesthetic dose is obtained with similar efficiency and even better hemodynamic stability [

15,

16,

17].

Hypotension induced by spinal anesthesia is frequently occurring in elderly patients. Many studies have been performed to decrease the incidence of SAIH, but no one has proved sufficiently compelling.

Proper sedation is now a key aspect of spinal anesthesia, vital for ensuring patient comfort and improving compliance with regional anesthesia techniques [

18].

Among spinal anesthesia side effects, cardiovascular complications are the most prominent, with hypotension being considered the most common, observed in up to 33% of patients [

19]. SA influences the sympathetic chain, causing reduced vasomotor tone, which leads to reduced preload (from vasodilation and decreased venous return), diminished afterload (due to lower systemic vascular resistance) [

20,

21], and, ultimately, reduced cardiac output, particularly in older adults [

21].

The leading cause of hypotension is the total dose of anesthetic administered. However, multiple other factors, such as the anesthetic type, its volume, accompanying adjuvant agents, and preoperative or intraoperative variables, also contribute to SA’s hemodynamic effects [

21,

22]. Our study compared FSA with MSA and the number of cases that needed Ephedrine for hemodynamic stability. There was no significant difference in percentage between the two groups.

For a long time, Ephedrine has been considered the standard vasoconstrictor for hypotension induced by SA [

23]. Ephedrine, a widely used adrenergic stimulant with both direct and indirect actions, has traditionally been favored for addressing the undesired hemodynamic changes caused by spinal anesthesia side [

24]. Administering Ephedrine using repeated intermittent IV boluses, however, is reactive rather than preventive, leading to fluctuating drug levels between peaks and troughs [

25]. Ephedrine is a sympathomimetic drug commonly used in perioperative settings, particularly during anesthesia, to manage hypotension that can occur after induction or during surgery.

Ephedrine, a mixed-action adrenergic agonist (targeting both alpha and beta receptors), increases cardiac output while mitigating heart rate reduction. It can achieve this by causing vasoconstriction that surpasses arteriolar constriction, improving venous return (preload), and boosting cardiac output, blood pressure, and heart rate [

26]. Various studies indicate that 13% of non-obstetrical patients develop bradycardia during SA [

27], and if corrective measures are taken, there are no significant consequences [

28].

Hypotension following spinal anesthesia is primarily due to sympathetic blockade, leading to vasodilation and a subsequent reduction in systemic vascular resistance (SVR). Additionally, venous pooling in the lower extremities and decreased cardiac preload contribute to reduced cardiac output. These effects necessitate prompt and effective management to maintain adequate perfusion, especially vital organs. Some studies describe that in SA, arterial vasodilatation reaches a maximum after about 7 minutes [

29,

30]. Age-related changes, such as alteration in systolic function and diastolic relaxation in the elderly, can aggravate the decrease in cardiac output [

31,

32,

33,

34].

Hypotension resulting from spinal anesthesia, primarily due to reduced stroke volume, can be managed with crystalloid or colloid solutions. Vasopressor agents, such as Ephedrine or phenylephrine, increase stroke volume and preload by increasing systemic vascular resistance without direct heart stimulation. Thus, vasopressors combined with crystalloid solutions effectively treat post-subarachnoid block hypotension in elderly patients.

Our study examined how the administration of Ephedrine prevents hypotension after SA and impacts hemodynamic changes in elderly patients. In 44.1% of our cases, the dose of Ephedrine is correlated with age, having a value of practical significance. Various studies have highlighted the critical role of avoiding even short episodes of hypotension in elderly patients to reduce risks of complications and mortality. Patient mortality and morbidity are influenced by intraoperative arterial hypotension [

35,

36]. It is a well-known fact that the incidence of hypotension induced by SA increases with age (about 36% of younger patients, increasing to 75% of patients over the age of 50) [

37]. Even with low doses of bupivacaine, hypotension induced by SA remains high in older patients [

32]. Mon et al. have shown that ephedrine administration was associated with reasonable systolic blood pressure control [

38]

Spinal anesthesia, a commonly used regional anesthesia technique, is widely employed for surgeries involving the lower abdomen, pelvis, and lower extremities. In orthopedic surgery, to minimize the hemodynamic consequences of SA, the patient’s position can be lateralized to the side to be operated on to obtain a predominantly unilateral sympathetic bloc [

39,

40]. This can be helpful in elderly patients who are at higher risk of SAIH.

In our study, we considered patients with HBP a high-risk factor for SAIH because we observed that in 19 % of the cases, HBP is correlated with the amount of ephedrine dose used, which is a statistical value with practical significance. The variability in ephedrine requirements among patients highlights the need for a more personalized approach to spinal anesthesia management. Patients experience variations in vasopressor response as a result of their baseline autonomic tone along with arterial stiffness in hypertension and cardiovascular system changes that occur during aging. Preoperative patient analysis through advanced machine learning algorithms could determine customized vasopressor doses from blood pressure variability and heart rate dynamics and pharmacokinetic data which would enhance operative safety and postoperative recovery. No major differences emerged from choosing bupivacaine-morphine or bupivacaine-fentanyl in this study group regarding ephedrine demand. Additional investigations should examine customized vasopressor dose frequencies to match each patient’s preoperative blood pressure dynamics for better clinical results.

5. Conclusions

Ephedrine remains a cornerstone in managing hypotension following spinal anesthesia. Its dual mechanism of action and proven efficacy make it a valuable tool in the anesthesiologist’s arsenal. However, individualized patient assessment and careful monitoring are essential to optimize its use and minimize potential side effects. Future research may further refine the role of Ephedrine and other vasopressors in this context, ensuring safer and more effective perioperative care.

This study emphasizes how individualized blood pressure management practices provide essential care for patients during spinal anesthesia procedures of hip arthroplasty. The efficacy of ephedrine administration for managing intraoperative hypotension depends on individual characteristics such as age, blood pressure status and natural state of autonomic management in patients. The findings demonstrate the crucial requirement for developing individual spinal anesthesia procedures which would integrate knowledge of patient comorbidities and drug reaction patterns.

Future investigations need to study how pharmacogenomics and real-time hemo-dynamic monitoring and AI-based predictive modeling can optimize perioperative vasopressor management. Anesthesiologists can customize their anesthesia protocols using precision medicine approaches to reduce intraoperative complications while ensuring patient safety throughout the recovery process. These advancements follow the patient-centered strategy of personalized medicine that uses individual genetic and physiological profiles to create anesthetic plans.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B.Sz., I.C.M.; methodology, M.O.B.; software, E.B.Sz.; validation, M.G.B., P.T.R., C.S., M.V.R., and A.G.O.; formal analysis, H.T.J., A.B.D.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T.J., A.B.D.; writing—review and editing, H.T.J., I.C.M.; visualization, C.S., M.V.R.; supervision E.B.Sz.; project administration, A.B.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of Oradea, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Pelican Hospital, Oradea (approval number 2591/15.12.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

Raw data will be made available by the first author, without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Messina, A.; La Via, L.; Milani, A.; Savi, M.; Calabrò, L.; Sanfilippo, F.; Negri, K.; Castellani, G.; Cammarota, G.; Robba, C.; Morenghi, E.; Astuto, M.; Cecconi, M. Spinal anesthesia and hypotensive events in hip fracture surgical repair in elderly patients: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anesthesia, Analgesia and Critical Care 2022, 2. [CrossRef]

- Uemura, Y.; Kinoshita, M.; Sakai, Y.; Tanaka, K. Hemodynamic impact of ephedrine on hypotension during general anesthesia: A prospective cohort study on middle-aged and older patients. BMC Anesthesiology 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngan Kee, W. D.; Lau, T. K.; Khaw, K. S.; Lee, B. B. Comparison of metaraminol and ephedrine infusions for maintaining arterial pressure during spinal anesthesia for elective cesarean section. Anesthesiology 2001, 95, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-David, B.; Frankel, R.; Arzumonov, T.; Marchevsky, Y.; Volpin, G. Minidose bupivacaine–fentanyl spinal anesthesia for surgical repair of hip fracture in the aged. Anesthesiology 2000, 92, 6–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOHARE, S.; VATSALYA, T.; MEHROTRA, S. An observational study to compare spinal anesthesia-induced hemodynamic changes in normotensive and hypertensive patients on antihypertensive medications. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research 2024, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil Shrestha, S. S.; Amatya, R. Prevention of spinal anesthesia induced hypotension in elderly: Comparison of prophylactic atropine with ephedrine. Journal of Anesthesia & Clinical Research 2015, 06. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-S.; Choi, W.-J. Use of vasopressors to manage spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension during cesarean delivery. Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 2024, 19, 85–93 https://. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandr, A. M.; Ahmed, A. M.; Bahgat, N. M. Comparative study among ephedrine, norepinephrine and phenylephrine infusions to prevent spinal hypotension during cesarean section. A randomized controlled double-blind study. Egyptian Journal of Anaesthesia 2021, 37, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-L. Arterial stiffness and hypertension. Clinical Hypertension 2023, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, G.; Marchais, S.; Guerin, A.; Pannier, B. Arterial stiffness: Pathophysiology and clinical impact. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension 2004, 26, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanss, R.; Bein, B.; Ledowski, T.; Lehmkuhl, M.; Ohnesorge, H.; Scherkl, W.; Steinfath, M.; Scholz, J.; Tonner, P. H. Heart rate variability predicts severe hypotension after spinal anesthesia for elective cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology 2005, 102, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, G. S.; Abrishami, A.; Lermitte, J.; Chung, F. Systematic review of spinal anaesthesia using Bupivacaine for Ambulatory Knee Arthroscopy. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2009, 102, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton P, Hanumanthaiah D, O' Leary RA, Iohom G. Effects of fentanyl added to a mixture of intrathecal bupivacaine and morphine for spinal anaesthesia in elective caesearean section. Rom J Anaesth Intensive Care. 2015 Oct;22(2):97-102. PMID: 28913464; PMCID: PMC5505381.

- Swain, A.; Nag, D. S.; Sahu, S.; Samaddar, D. P. Adjuvants to local anesthetics: Current understanding and future trends. World Journal of Clinical Cases 2017, 5, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bontea, M.; Bimbo-Szuhai, E.; Macovei, I. C.; Maghiar, P. B.; Sandor, M.; Botea, M.; Romanescu, D.; Beiusanu, C.; Cacuci, A.; Sachelarie, L.; Huniadi, A. Anterior approach to hip arthroplasty with early mobilization key for reduced hospital length of stay. Medicina 2023, 59, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botea, M. O.; Lungeanu, D.; Petrica, A.; Sandor, M. I.; Huniadi, A. C.; Barsac, C.; Marza, A. M.; Moisa, R. C.; Maghiar, L.; Botea, R. M.; Macovei, C. I.; Bimbo-Szuhai, E. Perioperative analgesia and patients’ satisfaction in spinal anesthesia for cesarean section: Fentanyl versus morphine. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y. W., Seah, Y. S., Chung, K. T., & Liu, M. D. (1999). Postoperative pain relief in primigravida caesarean section patients--combination of intrathecal morphine and epinephrine. Acta anaesthesiologica Sinica, 37(3), 111–114. PMID: 10609343.

- De Andrés, J., Valía, J. C., Gil, A., & Bolinches, R. (1995). Predictors of patient satisfaction with regional anesthesia. Regional anesthesia, 20(6), 498–505.PMID: 8608068.

- Hartmann, B.; Junger, A.; Klasen, J.; Benson, M.; Jost, A.; Banzhaf, A.; Hempelmann, G. The incidence and risk factors for hypotension after spinal anesthesia induction: An analysis with automated data collection. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2002, 94, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller R.D., Eriksson L.I., Fleisher L.A.,Wiener-Kronish J.P.,Young W.L., Miller, s Aneshesia, 7th Edition vol.1, Elsevier Health Sciences ,2009, ISBN 044 306959X,9780443069598.

- Messina, A., Frassanito, L., Colombo, D., Vergari, A., Draisci, G., Della Corte, F., & Antonelli, M. (2013). Hemodynamic changes associated with spinal and general anesthesia for hip fracture surgery in severe ASA III elderly population: a pilot trial. Minerva anestesiologica, 79(9), 1021–1029. PMID: 23635998.

- Hadzic A, Textbook of Regional Anesthesia and Acute Pain Management. Chapter 23McGraw-Hill Education - Europe. London, UK, 2017, ISBN 978-0-07-171759-5.

- Lee, A.; Ngan Kee, W. D.; Gin, T. A quantitative, systematic review of randomized controlled trials of ephedrine versus phenylephrine for the management of hypotension during spinal anesthesia for Cesarean Delivery. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2002, 94, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CRITCHLEY, L. A. H.; STUART, J. C.; CONWAY, F.; SHORT, T. G. Hypotension during subarachnoid anaesthesia: Haemodynamic effects of Ephedrine. British Journal of Anaesthesia 1995, 74, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertz, A. W.; H??bner, C.; Seefelder, C.; Seeling, W.; Lindner, K. H.; Rockemann, M. G.; Georgieff, M. The effect of ephedrine bolus administration on left ventricular loading and systolic performance during high thoracic epidural anesthesia combined with general anesthesia. Anesthesia & Analgesia 1994, 78. [CrossRef]

- Becker, D. E. Basic and clinical pharmacology of autonomic drugs. Anesthesia Progress 2012, 59, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, R. L.; Caplan, R. A.; Brown, D. L.; Stephenson, C.; Wu, R. Incidence and risk factors for side effects of spinal anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1992, 76, 906–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, R. A.; Ward, R. J.; Posner, K.; Cheney, F. W. Unexpected cardiac arrest during spinal anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1988, 68, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asehnoune, K.; Larousse, E.; Tadi??, J. M.; Minville, V.; Droupy, S.; Benhamou, D. Small-dose bupivacaine-sufentanil prevents cardiac output modifications after spinal anesthesia. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2005, 101, 1512–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyhoff, C. S.; Hesselbjerg, L.; Koscielniak-Nielsen, Z.; Rasmussen, L. S. Biphasic cardiac output changes during onset of spinal anaesthesia in elderly patients. European Journal of Anaesthesiology 2007, 24, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferré, F.; Marty, P.; Bruneteau, L.; Merlet, V.; Bataille, B.; Ferrier, A.; Gris, C.; Kurrek, M.; Fourcade, O.; Minville, V.; Sommet, A. Prophylactic phenylephrine infusion for the prevention of hypotension after spinal anesthesia in the elderly: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia 2016, 35, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lairez, O.; Ferré, F.; Portet, N.; Marty, P.; Delmas, C.; Cognet, T.; Kurrek, M.; Carrié, D.; Fourcade, O.; Minville, V. Cardiovascular effects of low-dose spinal anaesthesia as a function of age: An observational study using echocardiography. Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain Medicine 2015, 34, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofhuizen, C.; Lemson, J.; Snoeck, M.; Scheffer, G.-J. spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension is caused by a decrease in stroke volume in elderly patients. Local and Regional Anesthesia 2019, 12, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, F.; Delmas, C.; Carrié, D.; Cognet, T.; Lairez, O. Effects of spinal anaesthesia on left ventricular function: An observational study using two-dimensional strain echocardiography. Turkish Journal of Anesthesia and Reanimation 2018, 46, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHARLSON, M. E.; MACKENZIE, C. R.; GOLD, J. P.; ALES, K. L.; TOPKINS, M.; FAIRCLOUGH, G. P.; SHIRES, G. T. The preoperative and intraoperative hemodynamic predictors of postoperative myocardial infarction or ischemia in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Annals of Surgery 1989, 210, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, J. E.; Kurz, A.; Turan, A.; Mascha, E. J.; Sessler, D. I.; Saager, L. Development and validation of a risk quantification index for 30-day postoperative mortality and morbidity in noncardiac surgical patients. Anesthesiology 2011, 114, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, C. L., Underwood, P. S., Klein, R. L., & Kim, Y. I. (1968). Intravenous fluid administration as therapy for hypotension secondary to spinal anesthesia. Anesthesia and analgesia, 47(5), 548–556. PMID: 5691695.

- Mon, W.; Stewart, A.; Fernando, R.; Ashpole, K.; El-Wahab, N.; MacDonald, S.; Tamilselvan, P.; Columb, M.; Liu, Y. M. Cardiac output changes with phenylephrine and ephedrine infusions during spinal anesthesia for cesarean section: A randomized, double-blind trial. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia 2017, 37, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casati, A.; Moizo, E.; Marchetti, C.; Vinciguerra, F. A prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of unilateral spinal anesthesia with hyperbaric bupivacaine, Ropivacaine, or Levobupivacaine for inguinal herniorrhaphy. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2004, 1387–1392. [CrossRef]

- Casati, A. Restricting spinal block to the operative side: Why not? Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 2004, 29, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).