1. Introduction

Though groundwater is an essential global natural resource, it is one of the most precarious resources, especially for the megacities of developing arid regions [

1,

2]. Many arid cities face uncontrolled urbanization, rising global temperatures, unpredictable climate change, and unrestricted groundwater abstraction [

2,

3,

4]. Moreover, short-term and rigid engineering-focused infrastructural solutions disconnecting land use from the hydrological logics have isolated spatial planning practices, urban space, landscape, and user experience [

5], resulting in vulnerability and degradation of arid regions. Layering the sectoral divide between policymakers, engineers, planners, and the community has further discouraged sustainable urban development [

6], crucial for protecting the natural environment, resources, and the well-being of people and society [

7,

8].

Various concepts related to water-sensitive urban development have been applied globally, and multiple studies have explored notable in situ and remote sensing techniques to estimate potential groundwater zones and recharge. Yet, the arid regions, with increasing population and limited resources, suffer significantly from the wicked urban water crisis, continuously degrading resources, especially groundwater, increased ecological footprint, and unmanaged and crippled quality of urban life [

6]. This is because of the lack of a radical approach and a framework with a holistic view of the urban landscape and spatial planning sensitivity toward recharging groundwater resources [

9,

10], especially in rapid urbanizing and limited resources in arid regions such as the global south [

11]. It requires demonstrating the groundwater recharge (GWR) by exploring its potential and values from a spatial perspective toward social-ecological inclusive, sustainable development.

GWR is an integrated phenomenon dependent upon Landscape features and processes. Besides acting as transfer media of GW, landscape simultaneously provides structure, ecological coherence, and variation and simultaneously offers flexible and multifunctional functions [

12]. Also, landscape as an approach is linked to urban sustainability and land use [

13]. Putting nature and landscape as urbanism’s leading drivers and shaping forces creates better, more liveable environments [

12]. Developing strategies to Safeguard the landscape also improves GWR conditions. Certain landscape types, such as grasslands, forest cover, and agroforestry, correlate positively with improved GWR [

14,

15].

In this study, we develop a landscape-based groundwater recharge approach using landscape system, hydrological principles, and social-ecological inclusive strategies to encourage groundwater recharge through spatial interventions, multiscale and systematic thinking, and collaboration between the local community and various stakeholders. From a broader perspective, this is valuable for long-term sustainable development and the preservation of groundwater resources in all megacities in arid regions due to relevant urban and water challenges.

Karachi City (Pakistan) serves as a case study in this paper to explore the operational methods of landscape-based groundwater recharge in terms of spatial planning and design, as it is an urban region at risk of various environmental challenges caused by human-nature interactions, especially the exhaustion of groundwater [

16]. Karachi also faces the challenge of data and documentation scarcity, like many other developing regions. Hence, this case study provides insights about navigating by using landscape systems and contextual opportunities and challenges as the baseline to resolve critical urban challenges and documentation. Also, this study explores the potential of the landscape approach guiding GWR in an unpredictable urban environment with limited resources to provide social-ecological inclusive GWR opportunities.

A study titled “Mapping potential groundwater accumulation zones for Karachi City by using GIS and AHP techniques” by Ahmad et al. (2023) highlighted the GWR potential zones in Karachi City [

17]. Our study further develops spatial implications of landscape-based GWR possibilities in Karachi City. First, we analyzed the urban evolution of Karachi and its impact on water management and Groundwater recharge (GWR). Second, we added a geomorphological map of Karachi in the analytical hierarchy process (AHP) to make the multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) more comprehensive since geomorphology is one of the most heavily weighted factors in GWR potential calculation [

18].

Additionally, we developed natural and urban GWR composite maps to understand the natural GWR potential and the role of urbanization in damaging the GWR potential of Karachi City. Also, the redeveloped landscape-based GWR map of Karachi showed the potential contributions of different landscape and spatial typologies in improving the GWR of Karachi (i.e., the role of vacant spaces in an urban tissue, the role of streets in dense urban areas, the role of agricultural lands, and role of the natural reserves).

The study subsequently elaborates on landscape-based GWR as a holistic solution to numerous contemporary urban challenges faced by megacities of arid regions. It translates the relationship between different systems/layers of the urban landscape and their individual and combined suitability for GWR as spatial development opportunities. Moreover, how GWR and urban landscapes can strengthen each other by simultaneously repairing urban green quality and groundwater levels is also presented in this study. Although this study also uses the conventional tools of multi-criteria analysis, weight assignment to various parameters, and AHP to develop a landscape-based GWR potential map, the focus is to reflect on the spatial opportunities of GWR from a holistic landscape perspective.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study of Karachi City

Karachi City, the financial powerhouse of Pakistan, is a multilingual and social hybrid megacity in South Asia. It is geographically located between 24°45′ N to 25°37′ N and 66°42′ E to 67°34′ E. According to the UNESCO Aridity Index, Karachi is an arid city with a minimal rainfall of 150–200 mm/year. This arid environment causes high surface water losses due to transpiration, seepage, and evaporation. The coastal megacity of Karachi is one of the fastest-growing megacities in the world, with an estimated population of 27.2 million in 2020 [

19]. This population growth at the fast rate of 158.2% from 1990-2020 has caused an increase of built-up area from 241.5 sq. km to 733.4 sq. km. [

19]. This transition has caused an increased abstraction of groundwater, surface runoff, soil erosion, and a decrease in infiltration and recharge opportunities [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

Like other South Asian megacities, Karachi’s water crisis also deepens daily. The city is facing its worst water crisis in history [

25]. Karachi has a bulk water supply of 2.5 million m³/day (676 MGD)—nearly half of the required supply—with 35% of this water being lost during conveyance [

25,

26]. The disparity between demand and supply has increased the demand for groundwater over the past two decades for industrial and domestic water needs [

17]. Research conducted by the DAP-NEDUET University Karachi shows that Groundwater is the second primary source of alternative water used by Karachi residents. This uncontrolled abstraction is causing a decline in GW level at a rate of 2-3 meters per year in many areas in Karachi [

28].

Figure 1.

(a)World map highlighting Pakistan (b) Pakistan map highlighting Karachi and Indus River (c) Karachi map with water features and infrastructure (Source: KMP, KWSB and Author).

Figure 1.

(a)World map highlighting Pakistan (b) Pakistan map highlighting Karachi and Indus River (c) Karachi map with water features and infrastructure (Source: KMP, KWSB and Author).

Karachi’s early “fishing village settlement” was located along the alluvial Lyari riverbed, with water-bearing strata available throughout the year [

29]. Supporting services for drinking water, agriculture activities, and fishing depended upon this river, with the landscape of native fruit gardens, wells, and ponds [

30]. Subsoil water was documented to be approximately 6 m in higher areas and 0.6 m in the lowest parts of the city [

29]. This cultural and functional integration of the hydrological context was later dominated by technocratic water management, which focused on pipelines and a sectoral approach during the late 1800s.

The city has extended to include two more rivers within its boundary, the Hub and Malir, two non-perennial rivers that run beside the Lyari River. Construction over the natural drainage system, encroachment along the rivers, the illegal abstraction of sand from riverbeds, and inefficient drainage and sewerage systems have increased the frequency of urban flooding in recent decades [

31]. The Lyari and Malir rivers, once the source of water supply, now act as open sewage canals in the city, threatening the riparian and coastal ecosystems [

32]. The Sprawl analysis of Karachi shows that the built-up is spreading rapidly in the north and east over agricultural lands. The overexploitation of aquifers has resulted in many abandoned agricultural developments, loss of biodiversity, and unemployment [

19]. The cultural gardening (native fruit gardens) activities associated with rural Karachi are also declining alarmingly.

Although the river valleys have rich alluvial soils and GWR potential, the abstraction of sand from the riverbeds, dense urbanization, and unchecked waste disposal into these rivers have altered their ecology. This has resulted in a paradoxical urban water crisis in Karachi in the form of water scarcity and unmanaged stormwater and wastewater, affecting the urban landscape conditions. Also, the city’s urban and natural open spaces are under constant pressure from land use encroachments and human activities [

33]. This has further deteriorated the ecology of the megacity.

The factors of inefficient management, social imbalance, sudden demographic changes due to partition, post-partition migrations, and having the largest slum settlement in South Asia make Karachi a unique urban social laboratory [

34]. Besides the mentioned urban green space challenges, unofficial estimates suggest more than 700 squatter settlements in Karachi [

35]. These issues underline the dire need for a holistic and contextual approach toward urban development in Karachi that also addresses its entwined urban water challenges.

Table 1.

A temporal analysis of urban and water-related issues of Karachi (Literature sources: Hassan, Lari, Irfan, Pithawala, Qureshi).

Table 1.

A temporal analysis of urban and water-related issues of Karachi (Literature sources: Hassan, Lari, Irfan, Pithawala, Qureshi).

| Water management structure evolution |

Before colonialism |

1887 |

1941 |

1958-1997 |

1982 |

1998 |

Present |

| Reliance on Groundwater |

Very High and culturally integrated |

High and technocratic, |

High |

High and undocumented |

High and undocumented |

High and undocumented |

High and undocumented |

| landscape evolution |

Gardens, Wells, ponds |

Dumlottee wells ( |

Haleji scheme |

GKBWS Scheme |

Hub |

K2 |

K4 |

| Capacity |

Undocumented |

68191.35 m3/day |

90921.8

m3/day |

1272905.2 m3/day |

454609 m3/day |

454609 m3/day |

454609 m3/day |

| GW level |

|

| Urban landscape issues |

Integrated |

Colonial and exotic |

Real estate focused |

Immense pressure from migration |

Increased Sprawl, slum developments, unplanned development |

Holistic spatial planning can address these contested urban-water challenges considering the unprecedented increase in urbanization challenges, climate change, and social demands [

31]. Implementing holistic landscape-based GWR can retrofit the existing urban landscape challenges and help develop the long-term urban planning strategy. Also, using a case study of Karachi, where we have financial, management, and data constraints, this approach can help to foster inter-disciplinary collaboration and result in low-tech and long-term adaptive strategies that can be applied to relevant contexts (i.e., megacities of arid regions).

Figure 2.

City Parks that can be taken as an opportunity to improve Groundwater recharge. (a) Aziz Bhatti Park (b) Bagh ibn-e-Qasim (c) Safari Park.

Figure 2.

City Parks that can be taken as an opportunity to improve Groundwater recharge. (a) Aziz Bhatti Park (b) Bagh ibn-e-Qasim (c) Safari Park.

Figure 3.

Conceptual diagram of Karachi urban development and its water management evolution: 1: Dependence on Lyari river and integral utilisation local landscape and GW resources Before Colonialism, 2:1887- Approaching Malir river and extraction of Dumlottee wells, Subsequent addition of bulk supply projects from Indus (3:1958, 4:1982), 5: Using Hub to mitigate the.

Figure 3.

Conceptual diagram of Karachi urban development and its water management evolution: 1: Dependence on Lyari river and integral utilisation local landscape and GW resources Before Colonialism, 2:1887- Approaching Malir river and extraction of Dumlottee wells, Subsequent addition of bulk supply projects from Indus (3:1958, 4:1982), 5: Using Hub to mitigate the.

2.2. Landscape-Based Groundwater Recharge

GWR is the downward flow of water reaching the water table, forming an addition to the groundwater reservoir that may be natural or managed and direct or resulting from the near-surface concentration of water without well-defined channels[

36,

37]. It also involves landscape modifications or infrastructure developments to enhance water infiltration into the ground during dry periods. A few services associated with GWR include decreased saltwater intrusion, increased biodiversity, reduced immense pressure on bulk water supply, and increased soil fertility [

38].

GWR is based on knowledge from geology, soil formation, physiography, and ground hydrological conditions. These aspects are also the fundamentals of any landscape, which carries many values and services and workable space for addressing interconnected global challenges [

12,

39]. Recognizing these valuable landscape services in design, planning, and decision-making and using natural structures and processes to carry out the function make up the basic principle of a landscape-based approach [

12]. Understanding the connection between various surface and sub-surface landscape layers allows us to understand the interrelationship of landscape systems and humans and to explore the potential suitability for different processes in different areas [

40].

These landscape approaches embrace a holistic philosophy and have been promoted as alternatives to conventional sectoral land use planning, policy, and management. These approaches allow interdisciplinary knowledge creation and sharing, advocate for making policy, planning, and management more sensitive to space and scale, and provide a holistic understanding of the relationship between humans and their surrounding landscape [

41]. This way, the landscape approach connects spatial planning and multiple stakeholders’ objectives. Different stakeholders’ involvement allows the opportunity to explore the issues from design to management through a local lens and regional endeavor (

systematic thinking) through co-creative design. Landscape designers can be key in translating interdisciplinary concepts into spatial solutions [

6].

It supports the idea of utilizing landscape to solve the complex urban-water challenges and encourage GWR. This nexus between GWR and spatial, social, and ecological processes also aligns with using landscape as a base for design and planning, emphasizing the interconnectedness of natural and human systems. Besides considering the geohydrological aspects, when cultural, ecological, and social interactions are also valued while applying GWR through strategies, this can result in a multiscale socially and inclusive spatial framework of GWR from the regional to local scales. In this manner, a landscape (physical and non-physical) can guide GWR strategies toward network formulation and long-term adaptive solutions for sustainable urban environments.

We propose that landscape-based GWR can significantly help improve the urban landscape and GWR by integrating hydrological processes spatially across the landscape. If the essential relationship between green (landscape) and blue (water) is restored through spatial strategies, it can further ensure ecological, social, and economic prosperity [

42]. This approach is a social-ecological inclusive approach. Its holistic value allows the improvement of biodiversity, quality of life, and urban greenery while solving the core urban issues related to water, pollution, food security, and urban infrastructure. This approach can allow the sustainable transformation of a region while addressing natural, ecological, and social interferences spatially. This approach also addresses landscape fragmentation, connecting urban development, hydraulic logic, and natural processes associated with cultural and social practices through input from various stakeholders, local community, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Figure 4.

Landscape as the base for social and economic development (source: Stockholm resiliency Centre).

Figure 4.

Landscape as the base for social and economic development (source: Stockholm resiliency Centre).

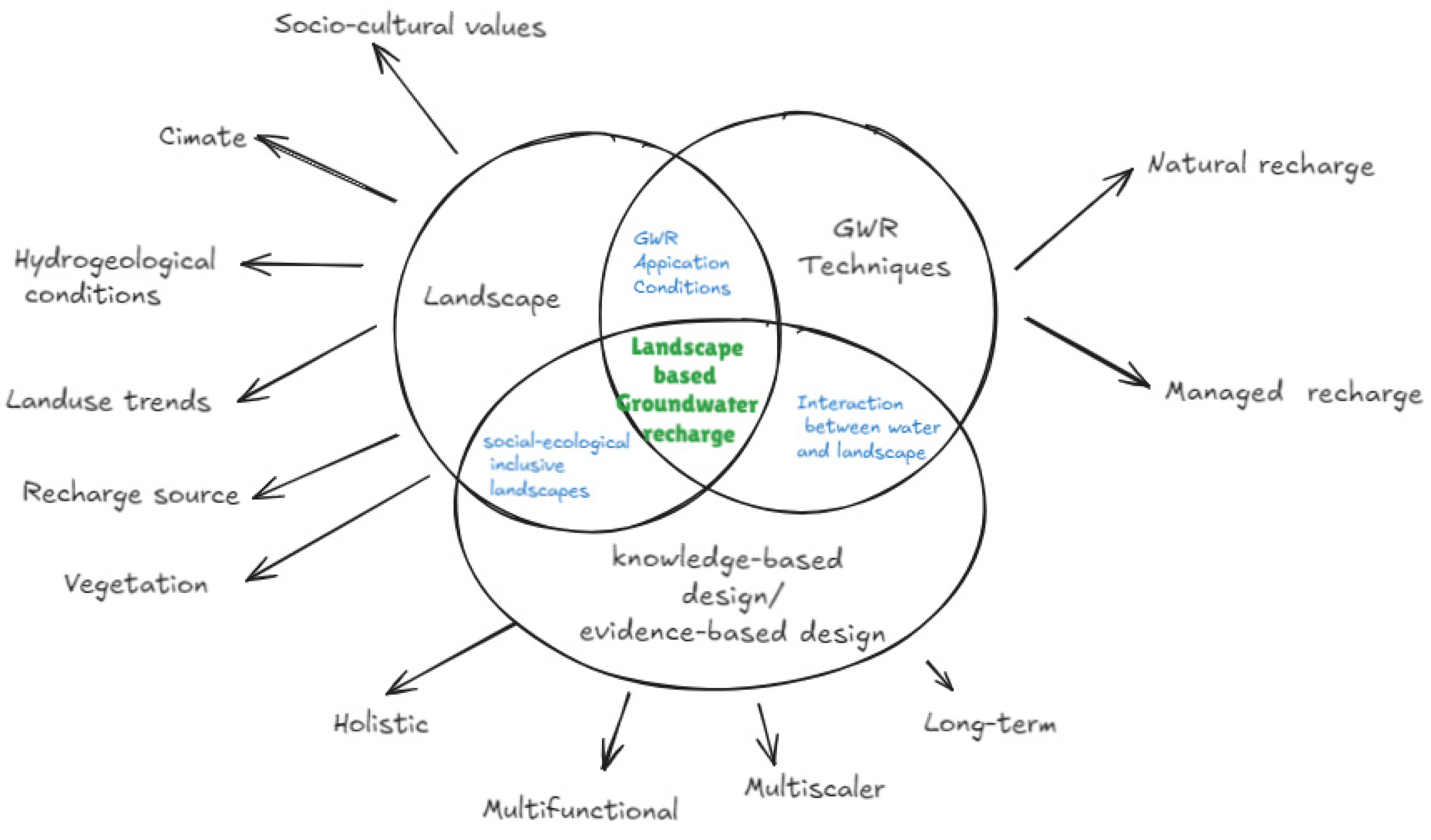

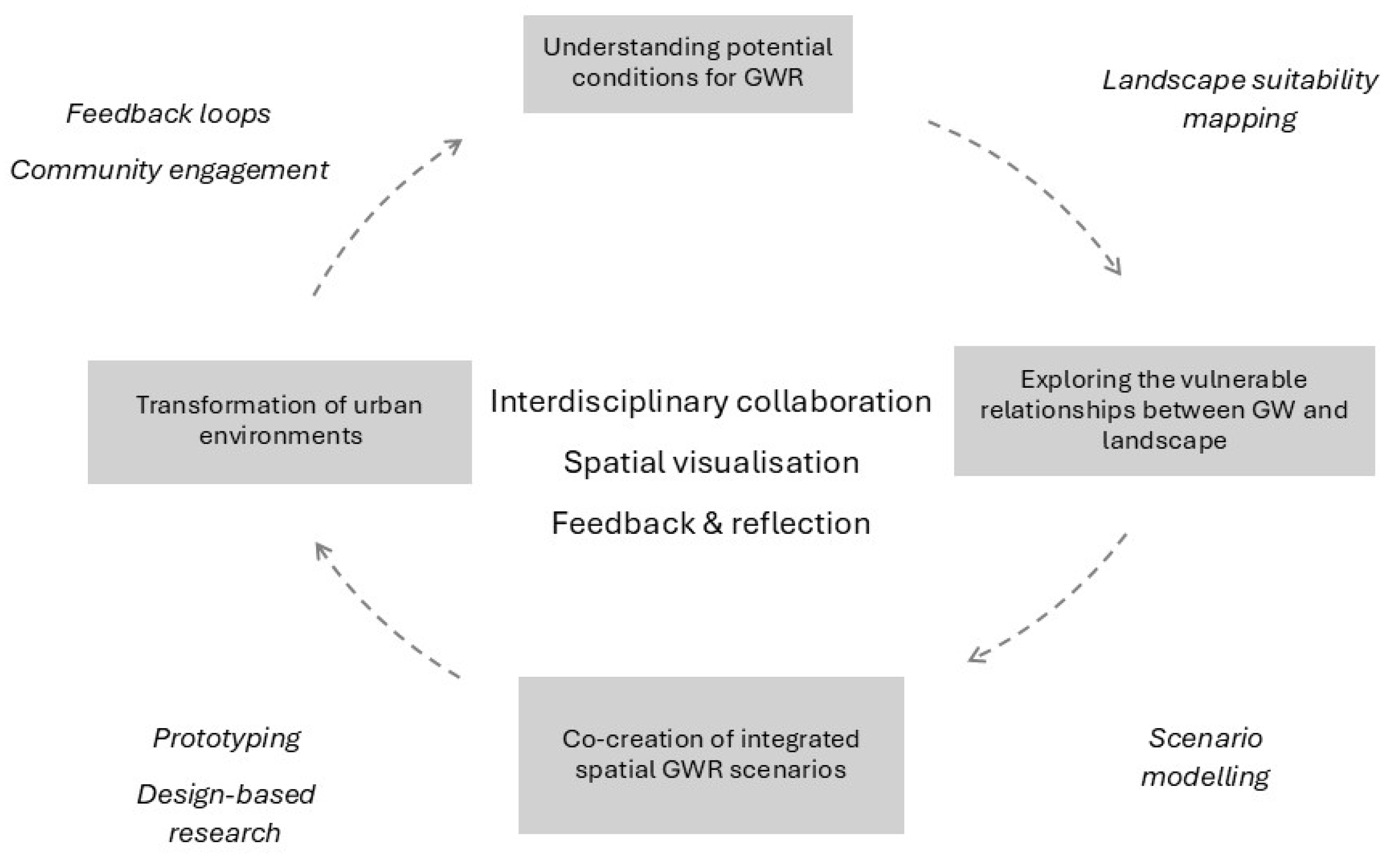

Hence, Landscape-based Groundwater Recharge has three core components to develop area-specific strategies by understanding the contextual landscape and related social-ecological processes as the basis of spatial development, i.e., groundwater recharge techniques, landscape, and knowledge-based/ evidence-based design. This can be achieved through 1) knowledge acquisition of mapping landscape system and its potential to accommodate GWR, 2) exploring spatial relationships between different landscape layers and synergies and conflicts under urban or climate change scenarios, 3) Developing strategies and principles through co-creative design explorations and spatial implementation of theoretical knowledge 4) transformation of urban environmental, enriching societal learning and reflection [

10]. By applying this iterative cycle, the fragmented knowledge of GWR can be combined holistically to suit the area’s specific strategies [

11].

Figure 5.

GWR, Landscape, and knowledge-based design as three units of landscape-based Groundwater recharge. Source (Author).

Figure 5.

GWR, Landscape, and knowledge-based design as three units of landscape-based Groundwater recharge. Source (Author).

Figure 6.

An iterative loop for landscape-based GWR for practical implementation (Source: Riaz).

Figure 6.

An iterative loop for landscape-based GWR for practical implementation (Source: Riaz).

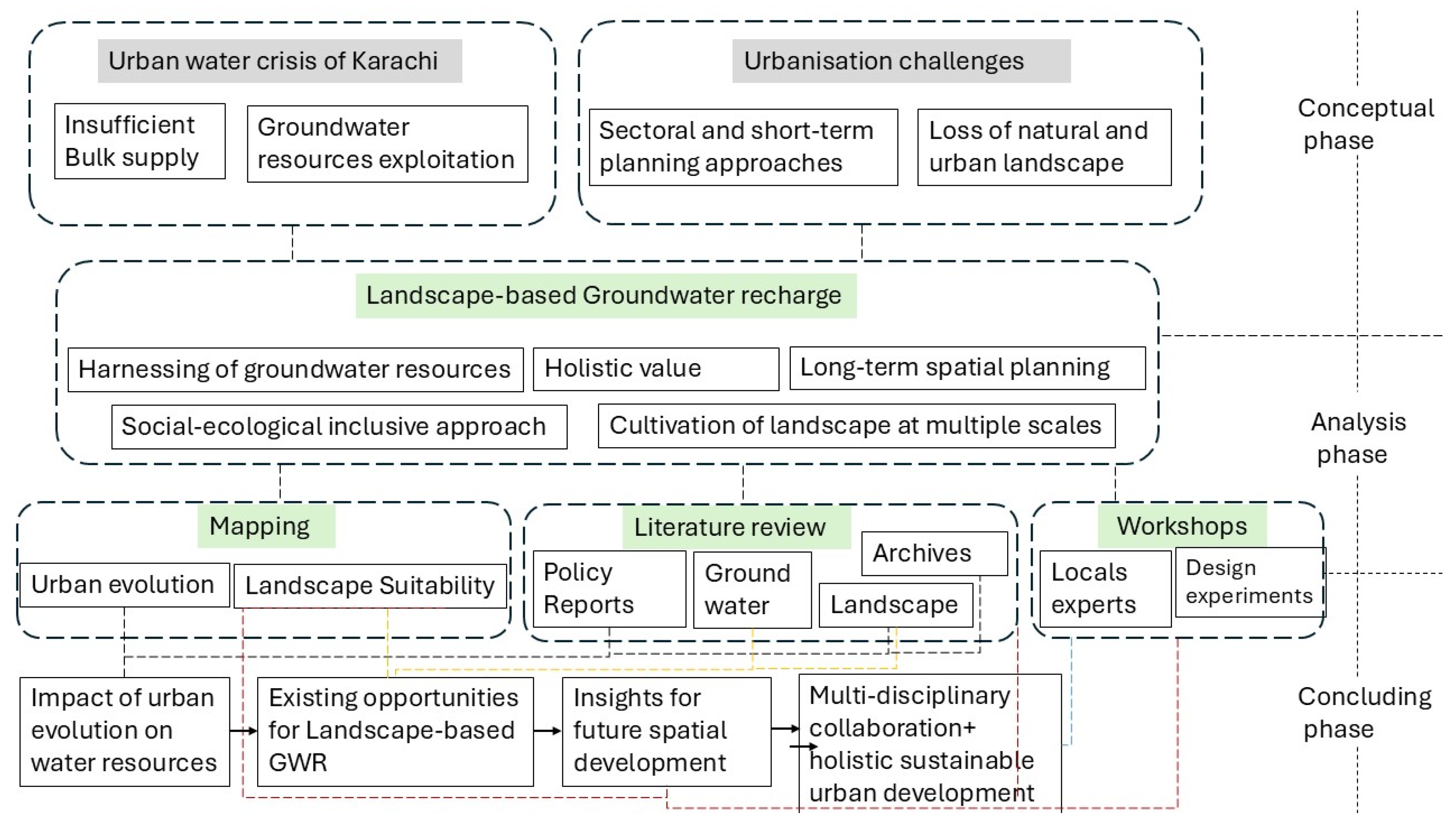

2.3. Methods- Mapping, Datasets, and Analysis

This study presents the concept of landscape-based groundwater recharge through an exploratory case study of Karachi City. A case study is an empirical inquiry to investigate phenomena in a real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomena within its context are not evident [

43]. We desk-studied three different types of literature, i.e., technical literature related to GWR, Arid regions water management issues, and contextual analysis of Karachi city, understanding the landscape as a system and its urban water crisis. Furthermore, we analyzed grey literature, government reports, historical archives, and maps. We conducted two interdisciplinary workshops in Karachi city (2023, 2024) where professionals, researchers, and academics from urban planning, architecture, social sciences, water board professionals, and geological and civil engineers participated. In this way, we could bridge some documentation gaps related to groundwater and understand urban landscape evolution, water management issues, and socio-cultural context from the local experts.

This study utilizes GWR potential mapping as one of the steps to present a holistic approach toward GWR. We redeveloped the thematic layers already used, except for the geomorphological layer, and validated them from the study [

16]. We developed a new geomorphological layer to modify Karachi’s groundwater recharge potential map (GWR). For this, we used a geological map of Sindh issued by the Geological Survey of Pakistan in 2012 and a geomorphological map of SW Karachi [

42]. We used the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP), with weights assigned to different layers based on their impact on GWR after the literature review. Thereafter, all the thematic layers were compared to each other in a pairwise matrix, and their subcategories were also assigned weights based on suitability. Each layer was assigned a ranking criterion. We used ArcGIS Pro to develop all the layers. Subcategories were classified by keeping a maximum of five classes.

We developed a natural and an urban composite to assess the GWR potential in natural conditions and the impact of urban development on it. Furthermore, we analyzed a few areas in Karachi. We discussed how landscape-based GWR can holistically address the challenges faced by spatial strategies and can be an instrumental strategy for long-term sustainable regional development.

Figure 7.

Conceptual framework of the study.

Figure 7.

Conceptual framework of the study.

Table 2.

Thematic Analytical hierarchy table for natural and built landscape layers.

Table 2.

Thematic Analytical hierarchy table for natural and built landscape layers.

| Factor |

Weights |

Ranking criterion |

Subcategory |

Suitability rank |

Overall weight |

Geomorp

hology |

29.6% |

Composition

and topography/permeability optimization

Porosity and low gradient > coarse and high gradient |

Coastal zone |

4 |

118.4 |

| Pediment zone |

7 |

207.2 |

| Relief |

6 |

177.6 |

| Alluvial |

8 |

236.8 |

| Plateau |

5 |

148 |

| Rivers |

9 |

266.4 |

| LULC |

27% |

Disposal of water |

Urban fabric |

4 |

108 |

| Industrial/Commercial |

3 |

81 |

| Agriculture |

8 |

216 |

Construction sites

|

5 |

135 |

| Grassland/rangeland |

7 |

189 |

| Parks/artificial |

6 |

162 |

| Inland water |

9 |

243 |

| Geological formation |

18% |

Structure formation

Fragmented st. > consolidated st. |

Quaternary sedimentary rocks

|

7 |

126 |

| Neogene sedimentary rocks |

6 |

108 |

| Waterbody |

8 |

144 |

| Paleogene sedimentary rocks |

6 |

108 |

| L.D. |

4.7% |

Fractures and faults density

High > low |

0–0.15 |

2 |

9.4 |

| 0.15–0.32 |

3 |

14.1 |

| 0.32–0.53 |

5 |

23.5 |

| 0.53–0.78 |

6 |

28.2 |

| 0.78–1.01 |

7 |

32.9 |

| Slope |

9.5% |

Gradient

Low > high |

0–12 |

7 |

66.5 |

| 12–24 |

6 |

57 |

| 24–36 |

5 |

47.5 |

| 36–48 |

4 |

38 |

| 48–60 |

2 |

19 |

| Soil |

1.8% |

Degree of permeability

Permeable > coarse |

Lithosols (sandy clay loam)

|

5 |

9 |

| Calci Yermosols (sandy loam) |

6 |

10.8 |

| D.D. |

7% |

Flow velocity

Low > high

|

0.0–0.17 |

8 |

56 |

| 0.17–0.35 |

7 |

49 |

| 0.35–0.52 |

6 |

42 |

| 0.52–0.70 |

5 |

35 |

| 0.70–0.87 |

3 |

21 |

| Rainfall |

2.4% |

Frequency

High > low |

143.25–159.24 |

3 |

7.2 |

| 159.24–177.84 |

4 |

9.6 |

| 177.84–197.67 |

5 |

12 |

| 197.67–218.31 |

7 |

16.8 |

| 218.31–240.33 |

8 |

19.2 |

3. Results

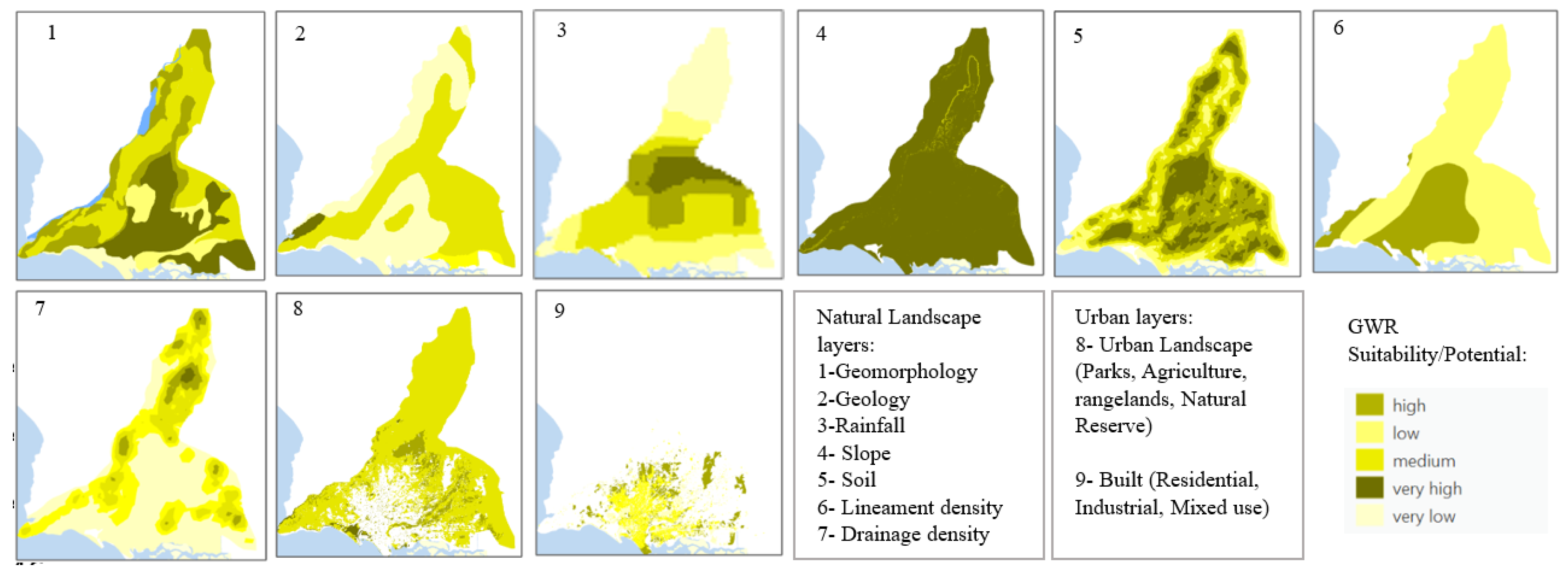

3.1. GWR Potential Mapping

This sub-section develops an independent and compound relationship of different landscape layers with GWR suitability. Decomposing the urban landscape into layers according to the dynamics of change is a proven method used to help understand urban landscape systems [

45]. Mapping these systems can help us understand spatial relationships and identify the suitability for GWR [

40]. Factors such as substratum conditions (geology, soil), geomorphology, climate variation (rainfall), geophysical conditions (drainage density, slope, lineament density), and urban tissue (infrastructure, land use, vegetation) provide anthropogenic influences information about the context. They can help to develop urban development strategies through landscape-based groundwater recharge.

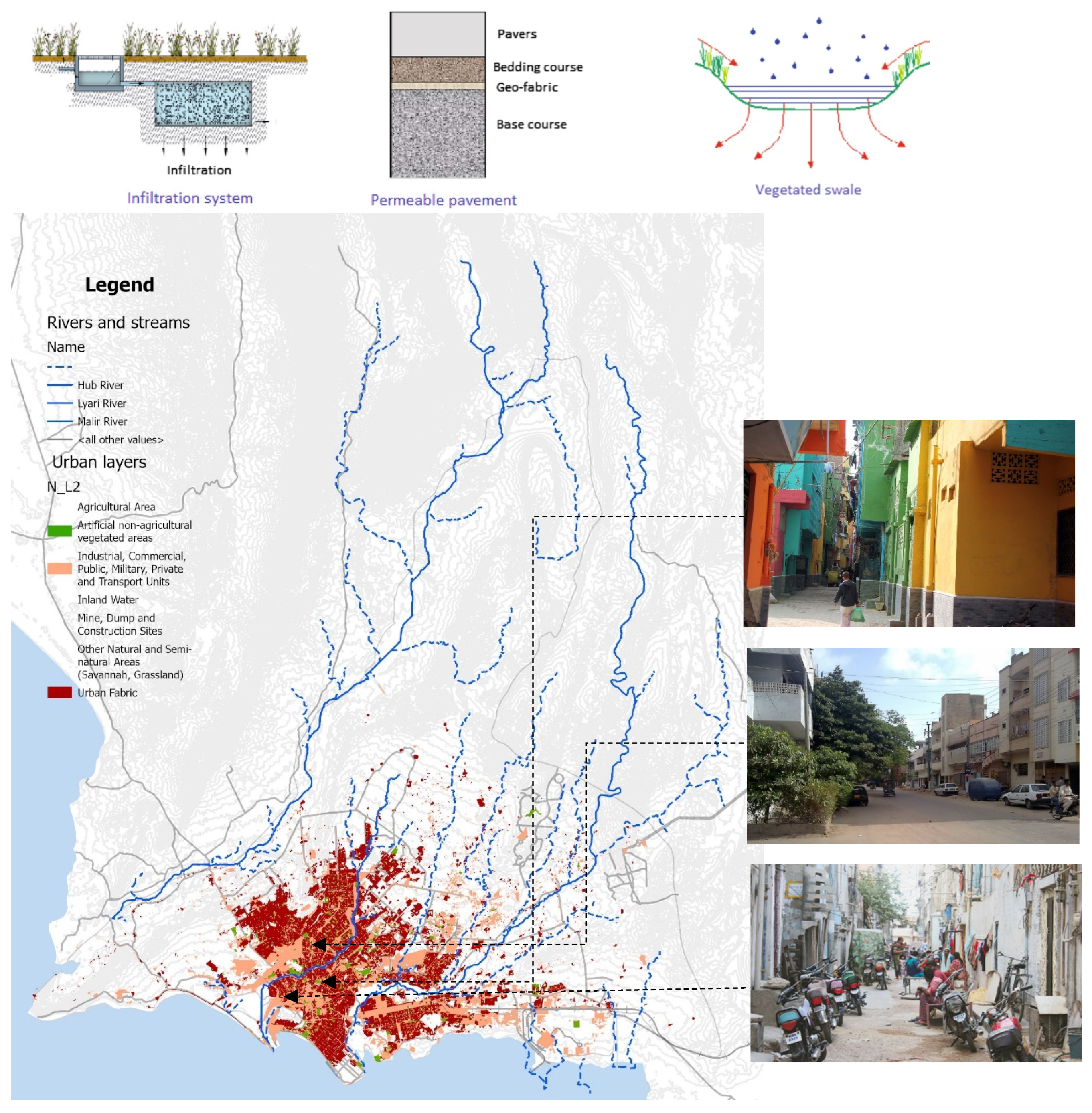

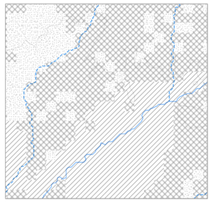

Figure 8.

Natural and urban landscape layers with their respective suitability for GWR.

Figure 8.

Natural and urban landscape layers with their respective suitability for GWR.

3.1.1. Individual Landscape Layers

Individual suitability maps of different landscape/thematic layers allow us to understand the suitability of Karachi’s natural geophysical conditions for accommodating GWR. The urban landscape of Karachi can be divided into five broad geomorphological categories: high relief, pediment zone, alluvial valleys, plateau, and coastal area [

44]. Alluvial river valleys show high suitability to GWR (

Figure 8 (1)). Karachi combines Quaternary, Neogene, and Paleocene lithological formations from a geological perspective. Layers of Quaternary sediments mainly include alluvial deposits in the river valleys with high water holding capacity and recharge potential. Neogene sedimentary rocks have clay, sandstone, and limestone, while Paleogene rocks mostly have limestone, clay, and sandstone with minor sandy clay [

17]. Structurally, the region forms part of the Kirthar Fold Belt of the lower Indus basin and presents a series of plunging folds trending NE-SW [

44]. These folds and lineaments provide water infiltration opportunities and are favorable for GWR (

Figure 8 (2)).

From north to south, Karachi exhibits a decrease in slope. Most of the study area has very low slopes (0–12 degrees) and is suitable for GWR since this gives water more time to infiltrate. However, a high topographic gradient is present in the Northern Kirthar Natural Reserve Area and southern Kohistan hills (

Figure 8 (4)). Two types of loamy soils are present in Karachi: Lithosols and Calcic Yermosols. Since both soils favor water infiltration, slope differences can be used to assign suitable ranks (

Figure 8 (6)) [

17].

The Hub, Lyari, and Malir rivers and their surrounding river valleys have high drainage density when compared to the inland areas. High drainage density is associated with low GWR potential due to high flow velocity. Hence, there is a need to develop flow-delaying strategies along the river corridors (

Figure 8 (5)). The Malir and Lyari rivers recharge the coastal aquifers, and the hub river recharge aquifers of the Nari (Oligocene) and Gaj (Miocene) formations [

46]. Rainfall is one of the most important sources of natural GWR since it facilitates high infiltration. Being in an arid region, Karachi experiences scarce and uneven rainfall, with a maximum of 240 mm in the Gadap area (

Figure 8 (3)).

Various land covers have shown different affinities toward surface runoff and subsurface flows [

47]. From a land use point of view, the old metropolitan areas are the densest, with intermixed residential and commercial settings. Notably, these areas usually lack formal green spaces. However, planned developments have parks and open spaces. These parks are fragmented throughout the developed urban areas with primarily low-maintenance exotic vegetation. Other than parks, agriculture belts, mangrove swamps, and bare rangelands or sparse vegetation on the outskirts of metropolitan areas represent the major vegetation types. Contemporary real estate developments are starting on the outskirts of formal rural agricultural lands or rangelands. Green and open spaces in the city are under constant pressure from significant encroachments and human activities [

33]. This decreases the GWR potential of the open areas of Karachi (

Figure 8(8)).

An urban fabric with impervious surfaces causes more surface runoff and is least suitable for GWR [

48]. Hence, though the dense urban tissue of the historical Karachi city shows high suitability to GWR in geomorphology, soil typology, and lithology layers, the built urban layer shows low GWR suitability (

Figure 8 (9)).

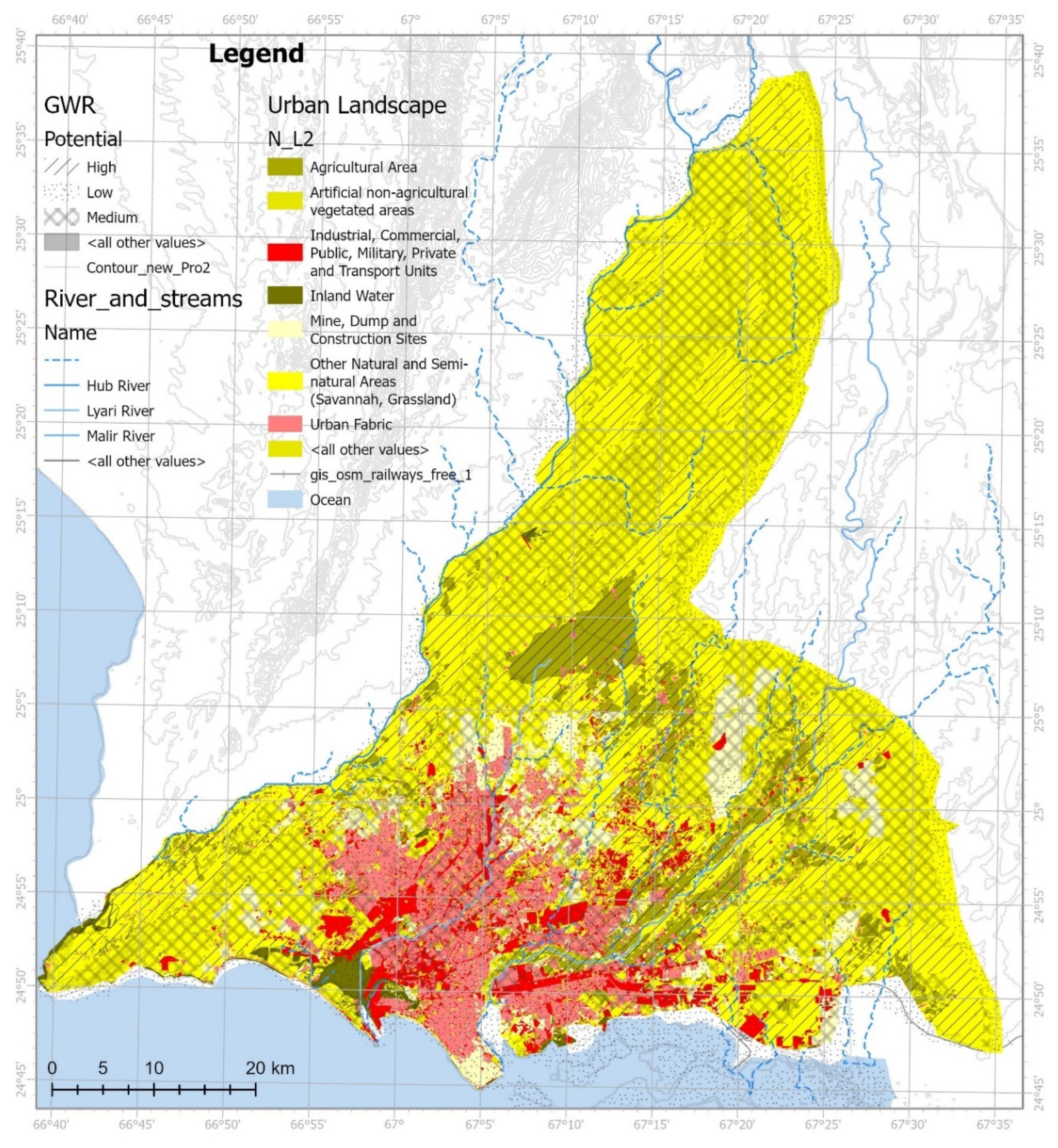

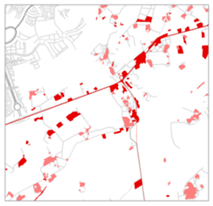

3.1.2. Landscape Composites

The comparison between the natural landscape GWR potential map and the urban composite GWR potential map helps to understand the natural potential and anthropogenic impact on the GWR potential. Results demonstrate that areas with high and medium GWR potential have decreased in their GWR potential because of urban development. Despite sub-surface geological conditions, GW levels have declined at alarming rates because of urbanization impacts [

31]. Thus, the current urban sprawl harms the GWR potential and calls for long-term sustainable planning goals that protect the groundwater and urban landscape.

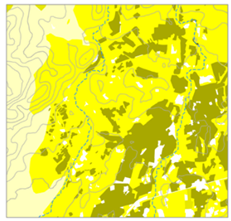

Figure 9.

GWR potential map with natural landscape layers (left); GWR potential map with natural and urban layers showing a decrease in the GWR potential of Karachi City (right) in the urban areas that highlights the important need for holistic spatial planning sensitive towards Groundwater recharge. Source: Riaz.

Figure 9.

GWR potential map with natural landscape layers (left); GWR potential map with natural and urban layers showing a decrease in the GWR potential of Karachi City (right) in the urban areas that highlights the important need for holistic spatial planning sensitive towards Groundwater recharge. Source: Riaz.

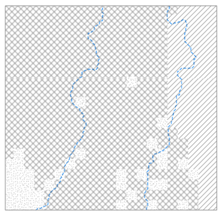

3.2. Landscape-Based GWR for Karachi-An Application Perspective

This subsection presents the potential opportunities for landscape-based GWR for Karachi (i.e., multiscale integration GWR through spatial planning). It develops an understanding of the synergy between urban hydrological cycles and aspects of urban development. While the natural recharge through rainfall and ineffective rainwater harvesting is minimal because of the region’s arid conditions, providing managed recharge strategies relevant to context can help in GWR. Hence, various spatial and landscape typologies are discussed to explore the landscape-based GWR for long-term sustainable development and safeguarding GW resources in Karachi.

Understanding GWR potential and the individual and compound landscape systems’ suitability of different natural and landscape layers for GWR allows for envisioning the existing urban landscape of Karachi as a spatial GWR opportunity. As a landscape-based approach, applying these spatial strategies to facilitate groundwater recharge in a social-ecological inclusive environment corresponding to the geological and hydrological technicalities can help achieve a multiscale vision from regional to local scale [

12].

It can reduce the pressure on the Indus supply at the regional level and improve biodiversity and ecosystem services. Future development can be planned at the urban level to preserve the high GWR potential areas and design accordingly. Zooming in from the urban to local scale opens participatory opportunities for various spatial strategies in different city areas based on the potential and suitability of GWR. Following are the few dimensions of employing Landscape-based GWR in Karachi.

Figure 10.

landscape-based GWR as a multi-scaler spatial framework (source: Author).

Figure 10.

landscape-based GWR as a multi-scaler spatial framework (source: Author).

River Valleys

Naturally, three rivers can be Karachi’s significant sources of GWR. They have suitable sub-surface geology for groundwater recharge [

31]. However, their potential has been compromised because of land use. Lyari River and its surroundings have been affected the most because of dense urban development, removal of green spaces, and encroachments on the drainage channels (

Figure 9). Contemporary studies show that the Malir River and its tributaries have great potential for rainwater harvesting and charging underground aquifers. Surrounded by rainfed agriculture, this area has a culture of small bunds that have been developed for 300 years, and dams have been built by the government to use rainwater and charge groundwater [

31].

Historically, The Malir River was identified as the largest underground water resource, with 4317 million m

3. Dumlottee Wells along the Malir Riverbed provided 36368–45461 m

3/day of water to the city, and the water quality was reported to be better than the Indus supply [

29]. This supply has now reduced to 5299 m

3/day during the rainy season; otherwise, the wells remain dry for the remainder of the year [

49]. If the groundwater in their vicinity is recharged, these wells may become operational again and revitalize the heritage of the Dumlottee Wells and GW.

Landscape-based GWR can help reactivate the drying riverscape of Karachi while improving the urban water supply conditions. Adding interventions on the alluvial riverbanks, like channel modification and induced bank filtration by engaging local stakeholders (farmers, local community), can add to their social, ecological, and recreational values while minimizing soil erosion. Harnessing the water in the upper river valleys of rivers through bunds and small dams and utilizing it later for cultivation and GWR can support the rainfed agriculture tradition of the Karachi region, empowering the local farmers while recharging the GW. Upper watershed management can also foster transboundary water management and a step towards sustainable regional development.

Figure 11.

(Top) GWR techniques are suitable for managed recharge (from left to right), channel modification, induced bank filtration, bunds, and barriers. (Bottom). River watersheds and sub-watershed areas map highlighting the transboundary watersheds of Hub and Malir rivers.

Figure 11.

(Top) GWR techniques are suitable for managed recharge (from left to right), channel modification, induced bank filtration, bunds, and barriers. (Bottom). River watersheds and sub-watershed areas map highlighting the transboundary watersheds of Hub and Malir rivers.

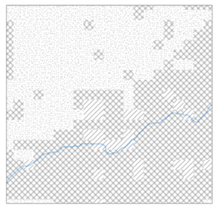

Rural Settlements

Agricultural activities of rural settlements of Karachi depend majorly on groundwater. Local fruits and vegetable gardens guava, mango, mulberry, papaya, and bananas) and vegetables (brinjal, tomatoes, spinach, pumpkin, okra, and agriculture fields were once major economic activities of these villages [

50]. Depletion of groundwater resources has become an existential threat to rural Karachi. Hence, rural Karachi and its cultural landscapes (orchards) are diminishing, increasing rural-urban migration [

50]. Increased economic pressure has forced the rural people to change their profession to sand and gravel excavation, migration to the city center, and working as laborers in city-center [

31].

The subsoil strata of the Gadap Plain (rural hinterland of Karachi), the Khadeji and Mol catchment areas, the Malir River Basin, and nearby village settlements (i.e., Kalu Khuhar, Jhimpir, Jhunshahi, Ran Pathani) is suitable for water retention [

51]. Now, there have been real estate developments encroaching the rural hinterland of Karachi and depleting the groundwater levels also. These villages (goths), located in empty lands between the natural reserve and the dense urban areas of Karachi can be developed to safeguard GWR areas with high potential (

Table 3, row 6). These landforms have rich alluvial soils, composite rocks, and productive agricultural activities. Restoring the cultural landscape of the rural areas can become a Landscape-based groundwater recharge model for new urban and rural developments for the megacities of arid regions that preserve high GWR potential zones, act as stormwater collection systems, and empower the local communities and economy.

Figure 12.

Rural areas of Karachi (orange coloured) developed along the agriculture belts showcase the opportunity of revitalizing cultural landscape (rural agriculture) by integration of landscape-based GWR.

Figure 12.

Rural areas of Karachi (orange coloured) developed along the agriculture belts showcase the opportunity of revitalizing cultural landscape (rural agriculture) by integration of landscape-based GWR.

The planned societies in the city have poorly maintained parks and less socially and ecologically inclusive [

33]. Existing unproductive green spaces can be changed into high-performance landscapes, i.e., family parks, multipurpose plazas for social gatherings, economic and playing activities, urban forests, and agroforests. This can make densely populated areas of Karachi a sponge by acupuncture points throughout the city that make a network of interventions to encourage landscape-based GWR possibilities.

Kirthar Park

In the north of Karachi, Kirthar Natural Reserve Park has a medium to high level of suitability for GWR (

Table 2, row4), with vegetation assemblages ranging from wetlands, sandy and plain riparian woodlands to cliffs, canyon vegetation, and irrigated fields [

54]. Plain habitats have traditional livestock grazing, cotton, onion, wheat, beans, lintels, dry fields, and wood harvesting. Mountain vegetation and cliffs show low human impact and high biodiversity. People and perennial woody vegetation are mainly dependent on groundwater resources. Baran Nadi (An Indus tributary) and Hub are the primary drainage resources [

54]

Figure 13.

(top) some possible GWR supporting interventions to improve streetscape. (bottom) map indicating different types of streets in the city.

Figure 13.

(top) some possible GWR supporting interventions to improve streetscape. (bottom) map indicating different types of streets in the city.

Figure 14.

Kirthar reserve Park (hatched in green) as an extension of landscape-based GWR strategies from urban to regional scale.

Figure 14.

Kirthar reserve Park (hatched in green) as an extension of landscape-based GWR strategies from urban to regional scale.

Adding contours and small bunds encourages infiltration, increases biodiversity, and implicitly helps discourage further human interventions. This can improve the ecological integrity of the Kirthar Reserve, increase ecosystem services, act as a significant regional underground water reserve, and contribute to the overall sustainability of the region. The transition of rangeland vegetation to cultivated crops can increase GWR [

55]. So, certain areas can be cultivated based on groundwater recharge potential mapping. Also, forest patches can be planted to increase biodiversity and decrease erosion [

36]. In this way, such landscape-based GWR strategies can help to strategize further development activities while conserving this pristine resource with the help of local communities.

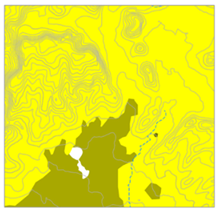

Figure 15.

Different categories of urban landscape, with hatching according to GWR potential. The map shows most agricultural areas lie in high GWR potential zones. Parks close to riverbanks also occur in high GWR zones while coastal zones and mangrove swamps show low GWR potential. Highlighted zones indicate areas zoomed in areas at the local scale (

Table 2). (Source:Riaz).

Figure 15.

Different categories of urban landscape, with hatching according to GWR potential. The map shows most agricultural areas lie in high GWR potential zones. Parks close to riverbanks also occur in high GWR zones while coastal zones and mangrove swamps show low GWR potential. Highlighted zones indicate areas zoomed in areas at the local scale (

Table 2). (Source:Riaz).

Table 3.

A zoom-in view of the relationship between GWR potential, landscape types, and built areas in Karahi City that further highlights the need of GWR friendly spatial planning.

Table 3.

A zoom-in view of the relationship between GWR potential, landscape types, and built areas in Karahi City that further highlights the need of GWR friendly spatial planning.

5. Discussion

5.1. Landscape-Based GWR as a Tool of Awareness

Karachi city has appropriate surface and sub-surface landscape conditions for GWR, but a lack of futuristic and holistic vision hinders the systematic integration of GWR in the urban landscape [

31]. Various local studies have pointed out a high dependence on groundwater daily. A study done on the SITE sub-division showed that reliance on groundwater is almost 94%. Industrial site’s GW levels are depleting more alarmingly than residential ones [

3]. Despite the high reliance on groundwater, the bulk water supply for Karachi has been prioritized by policy-making institutions.

Negligence towards this valuable resource has deteriorated its quality and quantity. Groundwater resources are poorly maintained and contaminated by sewerage discharge, which flows parallel to drinking and household water. After analyzing 28 groundwater samples, 24 were found to have high concentrations of nitrates and other contaminants [

56]. We can make groundwater an integral part of the landscape system through landscape-based groundwater recharge. It can further empower local communities to safeguard and value this resource by promoting relevant gardening, agriculture, and livestock management activities.

5.2. Landscape-Based GWR as a Way Towards Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Currently, the major stakeholders in water management in Karachi include KWSB, universities, the Sindh government, community representatives, NGOs, and experts [

57]. As a participatory approach, Landscape-based GWR further expands to engage local communities, urban planning professionals, landscape designers, architects, and real estate professionals as stakeholders. This integration of stakeholders allows for both top-down (expert-driven) and bottom-up (community-driven) approaches, which are vital for resolving conflicts and improving sustainable groundwater management at different (local and regional) levels [

58]. A shared understanding of the importance of GWR for restoring the hydrological and ecological balance of the cities promotes interdisciplinary capacity building, exchange of ideas, and building of knowledge-sharing forums.

5.3. Landscape-Based GWR as a Holistic Spatial Approach for Sustainable Regional Development

Though a network of solutions is needed for megacities like Karachi to restore the hydraulic cycle (i.e., water conservation, stormwater management, infrastructure improvements, and GWR), landscape-based GWR is one of the integral solutions that can work long-term on different levels in a socially and ecologically inclusive way by improving the existing urban landscape and guiding toward future urban development at various scales by multiple stakeholders. The involvement of spatial expertise in maintaining groundwater resources provides an understanding of the operation of an area as a combination of different natural and urban systems working on multiple scales. Also, it helps to draw comprehensive insights from historical, social-cultural, and ecological structures and promotes a holistic approach towards sustainable development [

59].

Furthermore, the co-creative design process helps spatially visualize potential futures and bridges the gap between theory and practice across disciplines. By designing adaptable, multifunctional spatial strategies, planners can accommodate shifting priorities, whether due to climate change, urbanization, cultural norms, or policy changes [

10]. This way, landscape-based GWR integrates with broader ecological, aesthetic, and recreational goals [

12].

5.4. Learning from the Relevant Contexts and Developing Adaptable Strategies

Landscape-based GWR encourages learning from the relevant contexts and examples. In this way, it can help develop multi-scaler spatial integration of adaptable strategies. For example, The water cup initiative by Paani Foundation India [

60], the Wadi Hanifa Rehabilitation Project in KSA [

61], and the restoration of Loess Plateau, China [

62] are regional scale precedents that encouraged the involvement of local communities by creating awareness and incentives to develop community-based models that add social, ecological, and economic value to GWR.

Moreover, landscape-based groundwater recharge values local initiatives and provides an opportunity to develop a series of networks of systematic interventions. Projects like revitalization of streets in the historic core of Karachi (One Planet Network, 2022) and neighborhood-scale urban forests (SUGi, 2021), traditional fruit gardens, orchards, and local agriculture produce can be revitalized through landscape-based Groundwater recharge and act as an opportunity to increase filtration (causal relationship).

5.5. Documentation and Quantitative Support to Enrich Landscape-Based GWR

Landscape-based GWR supports the incremental approach to acquiring contextual knowledge about landscape systems that can be revised, adjusted, and implemented based on state-of-the-art documentation and in other relevant contexts. This way, landscape-based GWR develops adaptive strategies through systematic, logical observations, a holistic understanding of landscape, and spatial planning. However, we strongly recommend quantitative documentation and updated hydrological modeling to validate the results. This can bridge the communication gap between sectors and provide a knowledge base for future research.

6. Conclusion

This paper presents a practical implementation of landscape-based GWR as a way to achieve sustainable future urban development. It is done by reinterpreting the GWR suitability of different landscape layers/systems and their mutual relationship. This approach can make the cities less dependent on the bulk water supply, develop and maintain local groundwater resources, and utilize the contextual urban landscapes as socially and ecologically inclusive GWR-supporting spaces. Landscape-based GWR is based on an understanding of the urban landscape as a system and its role in reactivating the GWR potential of an area by using socially and ecologically inclusive spatial strategies through interdisciplinary collaboration on multiple scales. Recently, many studies have been conducted to map the GWR potential of various cities and regions. However, this study uniquely explores its holistic, practical implementation through spatial planning.

We took the megacity of Karachi as a case study to explore the implementation of landscape-based GWR. We modified the GWR potential map of Karachi by adding the geomorphological layer to understand the impact of different landforms on GWR. A comparison between GWR potential maps with and without the urban layer showed a sufficient decrease in GWR potential, especially in densely populated alluvial river valleys. This baseline mapping highlighted the need for a spatial planning perspective in realizing the GWR potential through the urban landscape system and vice versa.

The hypothesis is supported by practical examples of different city areas and proposing strategies according to their GWR potential and landscape suitability conditions. For example, improving river corridors and streetscapes in dense urban areas, improving ecosystem services of reserves in the Kirthar reserve, and safeguarding rural agriculture and orchards in the rural hinterland of Karachi city. Applying this approach in Karachi can also make the Indus water supply less stressed while improving the city’s urban quality of life and landscape. This study used government reports, surveys, maps, archives, workshops, and pre-partition literature as evidence to support landscape-based GWR development in Karachi. Interdisciplinary collaboration at multiple scales has been highlighted as an essential tool for formulating a contextual yet adaptive spatial framework for integrating landscape-based GWR in the sustainable urban development of Karachi City.

We strongly recommend bridging the existing documentation gap through extensive surveying and mapping the existing aquifer levels to more precisely measure the impacts of landscape-based GWR. Additionally, mapping different layers of the landscape can further enrich our understanding of—and relationship with—ground hydrological conditions and the urban landscape. Also, future research should include the development of adaptable spatial strategies or patterns of landscape-based GWR to apply to the relevant contexts.

Author Contributions

Amna Riaz: conceptualization, methodology, Software, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Visualization. Dr. Steffen Nijhuis: Supervision, Writing—Review& editing, Validation. Dr. Inge Bobbink: Supervision, Writing—Review & editing, Validation. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Punjab Educational Endowment Fund Pakistan funds this research.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are already included in the review. Further data inquiries can be directed to the primary author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. There is no role of the funding sponsors in the choice of research project, study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing the manuscript, or decision to publish the results.

References

- F. van den Brandeler, J. Gupta, and M. Hordijk, “Megacities and rivers: Scalar mismatches between urban water management and river basin management,” J Hydrol (Amst), vol. 573, pp. 1067–1074, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Braga, S. Serrao-Neumann, and C. de Oliveira Galvão, “Groundwater Management in Coastal Areas through Landscape Scale Planning: A Systematic Literature Review,” Environ Manage, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 321–333, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Sohail et al., “Groundwater budgeting of Nari and Gaj formations and groundwater mapping of Karachi, Pakistan,” Appl Water Sci, vol. 12, no. 12, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, Z. Li, Y. Fan, H. Wang, and H. Deng, “Progress and prospects of climate change impacts on hydrology in the arid region of northwest China,” Environ Res, vol. 139, pp. 11–19, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- Stokman, “Water Purificative Landscapes-Constructed Ecologies and Contemporary Urbanism,” Blauwdruk/ Techne Press, 2008.

- Backhaus, O. fryd, and T. Dam, “Research in landscape architecture_methods and methodology,” in Research in landscape architecture_methods and methodology, A. Van den Brink, D. Bruns, H. Tobi, and S. Bell, Eds., Routledge, 2017, pp. 285–304.

- X. Bai, I. Nath, A. Capon, N. Hasan, and D. Jaron, “Health and wellbeing in the changing urban environment: Complex challenges, scientific responses, and the way forward,” Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huan, S. Nijhuis, and N. Tillie, “Urban agriculture as a landscape approach for sustainable urban planning. An example of Songzhuang, Beijing,” Frontiers in Sustainability, vol. 5, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. N. Lerner and B. Harris, “The relationship between land use and groundwater resources and quality,” Land use policy, vol. 26, no. SUPPL. 1, Dec. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S. Nijhuis, and I. Bobbink, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands, “Role of spatial planning in landscape-based groundwater recharge: A systematic literature review,” Feb. 2025. (under review water-3508952).

- Kumar, C. Button, S. Gupta, and J. Amezaga, “Water Sensitive Planning for the Cities in the Global South,” Water (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 2, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Nijhuis, “Landscape-Based Urbanism: Cultivating Urban Landscapes Through Design,” in Contemporary Urban Design Thinking, vol. Part F7, Springer Nature, 2022, pp. 249–277. [CrossRef]

- R. Defries and C. Rosenzweig, “Toward a whole-landscape approach for sustainable land use in the tropics,” in PNAS, Nov. 2010, pp. 19627–19632. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Noriega-Puglisevich and K. I. Eckhardt, “Hydrological effects of the conversion of tropical montane forest to agricultural land in the central Andes of Peru,” Environmental Quality Management, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. W. Negash, F. K. Abagale, and B. N. Baatuuwie, “Impact of land-use and land-cover change on watershed hydrology: a case study of Mojo watershed, Ethiopia,” Environ Earth Sci, vol. 81, no. 23, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Ghazal, S. Zubair, and A. Zafar, “Urban Water Management Issues in Megacity of Karachi,” 2021.

- Ahmad, H. Hasan, M. M. Jilani, and S. I. Ahmed, “Mapping potential groundwater accumulation zones for Karachi city using GIS and AHP techniques,” Environ Monit Assess, vol. 195, no. 3, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Minh, “Criteria Affecting Groundwater Potential: A Systematic Review of Literature,” in Environmental Science and Engineering, Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2023, pp. 85–110. [CrossRef]

- R. W. Aslam, H. Shu, and A. Yaseen, “Monitoring the population change and urban growth of four major Pakistan cities through spatial analysis of open source data,” Ann GIS, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 355–367, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Al-Kindi, A. F. Alqurashi, A. Al-Ghafri, and D. Power, “Assessing the Impact of Land Use and Land Cover Changes on Aflaj Systems over a 36-Year Period,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 15, no. 7, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Vaddiraju and R. T, “Urbanization implications on hydro-meteorological parameters of Saroor Nagar Watershed of Telangana,” Environmental Challenges, vol. 8, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. O. Randhir and O. Tsvetkova, “Spatiotemporal dynamics of landscape pattern and hydrologic process in watershed systems,” J Hydrol (Amst), vol. 404, no. 1–2, pp. 1–12, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Ramli, A. Achmad, A. Anhar, and A. Izzaty, “Landscape patterns changes and relation to water infiltration of Krueng Peusangan Watershed in Aceh,” Dec. 02, 2021, IOP Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- S. Bhaskar et al., “Will it rise or will it fall? Managing the complex effects of urbanization on base flow,” in Freshwater Science, University of Chicago Press, Mar. 2016, pp. 293–310. [CrossRef]

- M. Tayyab, “Management of Surface Water Resources to Mitigate the Water Stress in Karachi,” in International conference on hydrology and water resources, Lahore: University of ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY, LAHORE, Mar. 2021, pp. 196–204. [Online]. Available: www.cewre.edu.pk.

- City District Government Karachi, Engineering Consultants International (Pvt.) Limited, and PADCO-AECOM, “Karachi Strategic Development Plan 2020,” 2007. Accessed: Feb. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://urckarachi.org/2020/07/19/karachi-strategic-development-plan-2020/.

- M. Irfan, S. J. H. Kazmi, and M. H. Arsalan, “Sustainable harnessing of the surface water resources for Karachi: a geographic review,” Arabian Journal of Geosciences, vol. 11, no. 2, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. uddin Ahmed, (NED University, Karachi, Pakistan) “Groundwater Recharge within the City; Overlaps between Urban Issues, Opportunities, and Sustainability Requirements,” Oct. 2024. (Workshop presentation).

- M. Pithawala, P. Kaye, and D. Wadia, “Topography and Hydrography,” in Geology and Geography of Karachi and its Neighborhood, Karachi: Daily Gazette Press, 1946, pp. 14–17.

- Yasmeen. Lari and M. S. . Lari, The dual city : Karachi during the Raj. Heritage Foundation : Oxford University Press, 1996.

- M. Irfan, S. J. H. Kazmi, and M. H. Arsalan, “Sustainable harnessing of the surface water resources for Karachi: a geographic review,” Arabian Journal of Geosciences, vol. 11, no. 2, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Nergis, M. Sharif, A. F. Choudhry, A. Hussain, and J. A. Butt, “Impact of industrial and sewage effluents on Karachi coastal water and sediment quality,” Middle East J Sci Res, vol. 11, no. 10, pp. 1443–1454, 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. Qureshi, J. H. Breuste, and S. J. Lindley, “Green space functionality along an Urban gradient in Karachi, Pakistan: A socio-ecological study,” Hum Ecol, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 283–294, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, “Emerging urbanisation trends: The case of Karachi,” 2016.

- Hasan and M. Mohib, “The case of Karachi, Pakistan,” 2003.

- R. Scanlon, I. Jolly, M. Sophocleous, and L. Zhang, “Global impacts of conversions from natural to agricultural ecosystems on water resources: Quantity versus quality,” Water Resour Res, vol. 43, no. 3, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. de Vries and I. Simmers, “Groundwater recharge: An overview of process and challenges,” Hydrogeol J, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 5–17, Feb. 2002. [CrossRef]

- W. Alley, P. Dillon, and Y. Zheng, “Basic Concepts of Managed Aquifer Recharge,” in Managed Aquifer Recharge: Overview and Governance, 2022.

- M. Bürgi et al., “Integrated landscape approach: Closing the gap between theory and application,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 9, no. 8, p. 1371, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ian L. McHarg, Design with Nature. Philadelphia: Natural History Press, 1969. Accessed: Jan. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://archive.org/details/designwithnature00mcha/mode/2up.

- Arts, M. Buizer, L. Horlings, V. Ingram, C. Van Oosten, and P. Opdam, “Annual Review of Environment and Resources Landscape Approaches: A State-of-the-Art Review Keywords,” Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour, vol. 8, no. 8, pp. 439–63, 2017. [CrossRef]

- United Nations, “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.”.

- Groat and D. Wang, Architectural Research Methods. Wiley, 2013.

- G. Hamid, K. A. Mallick, M. Bilal, I. Azma, S. Zohaib Ishaq, and R. R. Zohra, “Geomorphology of Karachi with a brief note on its Vegetation,” INT. J. BIOL. BIOTECH, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 123–137, 2012.

- S. Nijhuis, L. Xiong, and D. Cannatella, “Towards a Landscape-based Regional Design Approach for Adaptive Transformation in Urbanizing Deltas,” Research in Urbanism Series, vol. 6, pp. 55–80, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Humza, M. Waris, and M. Haris, “Aggregate Properties Of Fluvial Deposits Of Malir, Lyari And Hub Rivers Of Karachi Embayment, Southern Indus Basin, Pakistan,” International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications (IJSRP), vol. 12, no. 7, pp. 42–57, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Arulbalaji, D. Padmalal, and K. Sreelash, “GIS and AHP Techniques Based Delineation of Groundwater Potential Zones: a case study from Southern Western Ghats, India,” Sci Rep, vol. 9, no. 1, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Li et al., “Effects of urbanization on the water cycle in the Shiyang River basin: based on a stable isotope method,” Hydrol Earth Syst Sci, vol. 27, no. 24, pp. 4437–4452, 2023. [CrossRef]

- WWF, “Situational Analysis of Water Resources of Karachi,” Karachi, 2019. Accessed: Feb. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://wwfasia.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/report___situational_analysis_of_water_resources_of_karachi.pdf.

- Ghazal, S. H. Jamil Kazmi, and S. Afsar, “Spatial Appraisal of the Impacts of Drought on Agricultural Patterns in Karachi,” Journal of Basic & Applied Sciences, no. 9, pp. 352–360, 2013.

- Karachi Development Authority and United Nations, “Karachi Development Plan 1974-1985,” Aug. 1974. Accessed: Mar. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://urckarachi.org/2020/07/19/karachi-development-plan-1974-1985/.

- F. Ahammed, “A review of water-sensitive urban design technologies and practices for sustainable stormwater management,” Sustain Water Resour Manag, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 269–282, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Sabbion, “Green streets to improve water management,” in Nature Based Strategies for Urban and Building Sustainability, Elsevier Inc., 2018, pp. 215–225. [CrossRef]

- J. Enright, B. P. Miller, and R. Akhter, “Desert vegetation and vegetation-environment relationships in Kirthar National Park, Sindh, Pakistan,” J Arid Environ, vol. 61, no. 3, pp. 397–418, 2005. [CrossRef]

- R. Malive and T. Missimer, “Factors Controlling the Rate of Infiltration and Recharge in Arid Regions,” in Arid Lands Water Evaluation and Management, Berlin: Springer, 2012, pp. 194–195. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Khan et al., “Statistical and Geospatial Assessment of Groundwater Quality in the Megacity of Karachi,” J Water Resour Prot, vol. 11, no. 03, pp. 311–332, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed and M. Sohail, “Stakeholders’ response to the private sector participation of water supply utility in Karachi, Pakistan,” Water Policy, vol. 6, pp. 229–247, 2004, [Online]. Available: http://iwaponline.com/wp/article-pdf/6/3/229/407007/229.pdf.

- H. Vejre, J. P. Vesterager, L. S. Kristensen, and J. Primdahl, “Stakeholder and expert-guided scenarios for agriculture and landscape development in a groundwater protection area,” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, vol. 54, no. 9, pp. 1169–1187, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Kmoch, A. Bou-Lahriss, and T. Plieninger, “Drought threatens agroforestry landscapes and dryland livelihoods in a North African hotspot of environmental change,” Landsc Urban Plan, vol. 245, 2024. [CrossRef]

- The Logical Indian, “Satyamev Jayate Water Cup_ This Is How The Paani Foundation Has Been Fighting Drought In Maharastra,” Feb. 01, 2019. Accessed: Mar. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://thelogicalindian.com/my-social-responsibility/water-cup-satyamev-jayate-maharashtra/.

- S. Moosavi, “Time, trial and thresholds: Unfolding the iterative nature of design in a dryland river rehabilitation,” Journal of Landscape Architecture, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 22–35, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yu, W. Zhao, J. F. Martinez-Murillo, and P. Pereira, “Loess Plateau: from degradation to restoration,” Oct. 10, 2020, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).