1. Introduction

Mitral annular disjunction (MAD) is defined as the spatial displacement of the left atrial wall-mitral leaflet junction from the left ventricular (LV) wall during systole [

1]. It is frequently detected in individuals with mitral valve prolapse (MVP), with an estimated prevalence ranging between 14.9% and 90%, depending on the imaging modality used for its identification and measurement [

2,

3]. Even if imaging studies have reported a more frequent location of MAD at level of P2 [

4] or P3 scallop [

5], pathological studies have described the MAD presence at any point around the mitral valve annulus (MVA) [

6]. Accordingly, it is more appropriate to consider MAD as a circumferential phenomenon involving the entire MVA circumference [

4,

5].

Several studies [

5,

7,

8,

9,

10] have demonstrated an association between MAD and the occurrence of premature ventricular complexes, ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) and, potentially, sudden cardiac death. It is hypothesized that MAD causes hypermobility of the mitral valve (MV) apparatus, leading to an increased traction on the papillary muscles and the basal inferolateral LV wall. The continuous abnormal tugging on the sub-mitral apparatus can result in myocardial fibrosis, thus creating possible foci for VAs origin [

11].

Multimodality imaging may play an important role in both the diagnosis and the prognostic risk stratification of MAD individuals. During the last two decades, a number of authors have evaluated MAD by using different imaging techniques, such as transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) [

7,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) [

14,

24], cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) [

3,

14,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29] and cardiac computed tomography angiography (CCTA) [

30]. The aforementioned imaging modalities have demonstrated a different diagnostic accuracy in assessing MAD presence and extent.

Herein, we present a clinical case of MAD female referred to our cardiology outpatient clinic because of resting palpitations and exercise-induced dyspnea, who underwent a multimodality imaging assessment comprehensive of TTE, TEE, CMR, CCTA and exercise stress echocardiography (ESE).

2. Clinical Case

A 62-year-old woman (BSA 1.69 m2, BMI 21.8 Kg/m2), affected by mild dyslipidemia in treatment with rosuvastatin 5 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg, without a previous history of cardiovascular disease and without any noncardiovascular comorbidity, was referred to our cardiology outpatient clinic to perform conventional TTE due to resting palpitations and exercise-induced dyspnea. A previous 24-hour ECG Holter monitoring showed constant sinus rhythm with normal atrio-ventricular and intra-ventricular conduction and sporadic isolated VAs (approximately 250/24-hours), occasionally perceived by the patient. She was prescribed with bisoprolol 1.25 mg once daily.

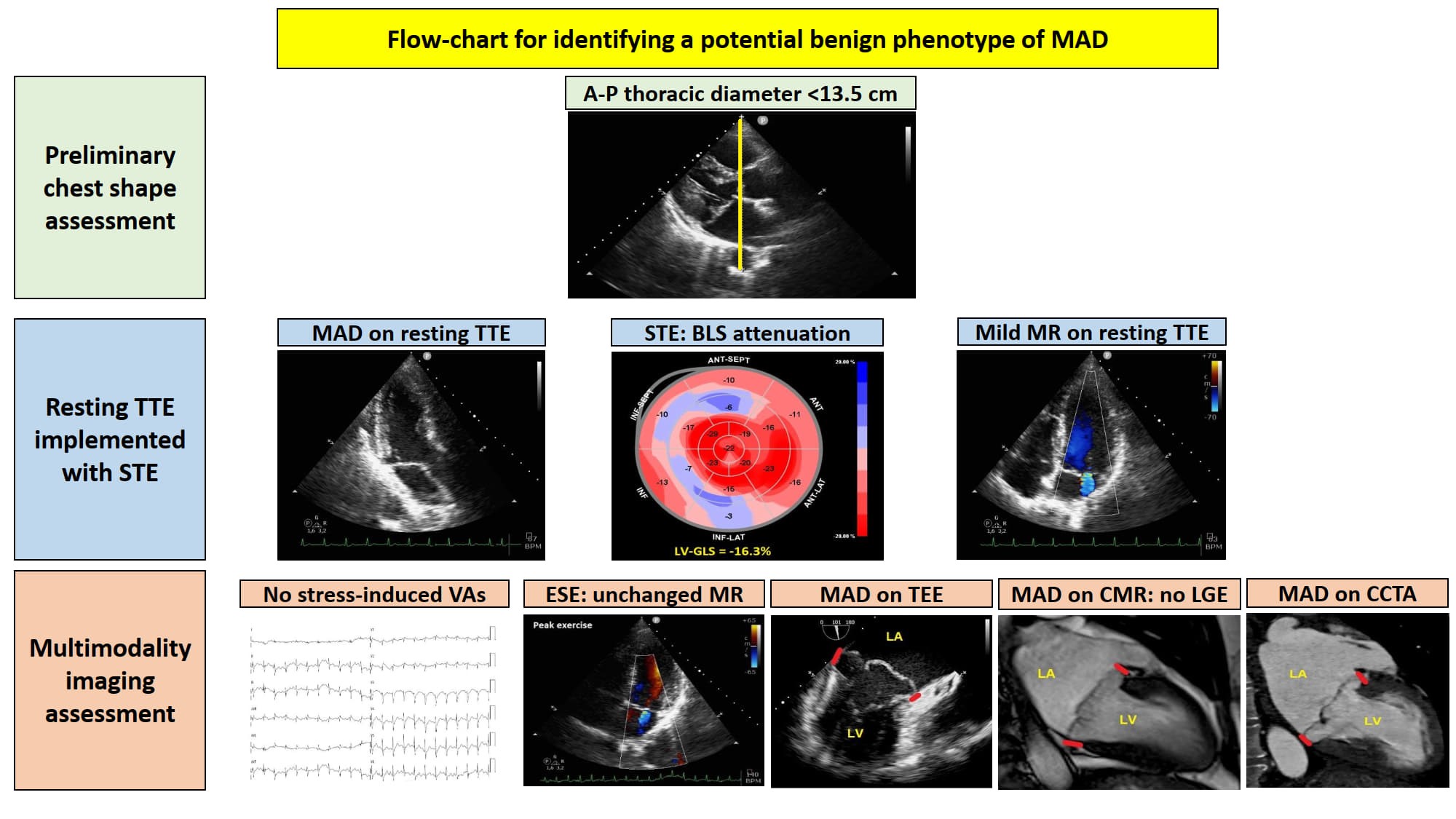

A preliminary chest shape assessment, as noninvasively assessed by the modified Haller index (MHI) [

31], obtained by dividing the latero-lateral (L-L) thoracic diameter by the antero-posterior (A-P) thoracic diameter, revealed a concave-shaped chest wall conformation (L-L thoracic diameter = 29 cm, A-P thoracic diameter = 11 cm, estimated MHI = 2.6) (

Figure 1).

Resting TTE measurements revealed: normal cardiac chambers cavity sizes (left ventricular end-diastolic diameter = 46 mm, right ventricular basal end-diastolic diameter = 33 mm, left atrial antero-posterior end-systolic diameter = 40 mm, right atrial longitudinal diameter 50 mm), grade 1 LV diastolic dysfunction and normal biventricular systolic function [left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) estimated with the biplane Simpson's method = 60%; tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) = 27 mm]; the aortic valve was tricuspid with normal function; a MVP with myxomatous degeneration of both leaflets and moderate mitral regurgitation (MR) was observed; a concomitant MAD was detected from the parasternal long-axis view (systolic infero-lateral MAD distance = 11 mm), from the apical four-chamber view (systolic antero-lateral MAD distance = 9 mm) and from the apical two-chamber view (systolic infero-medial MAD distance = 9 mm and systolic anterior MAD distance = 6 mm) (

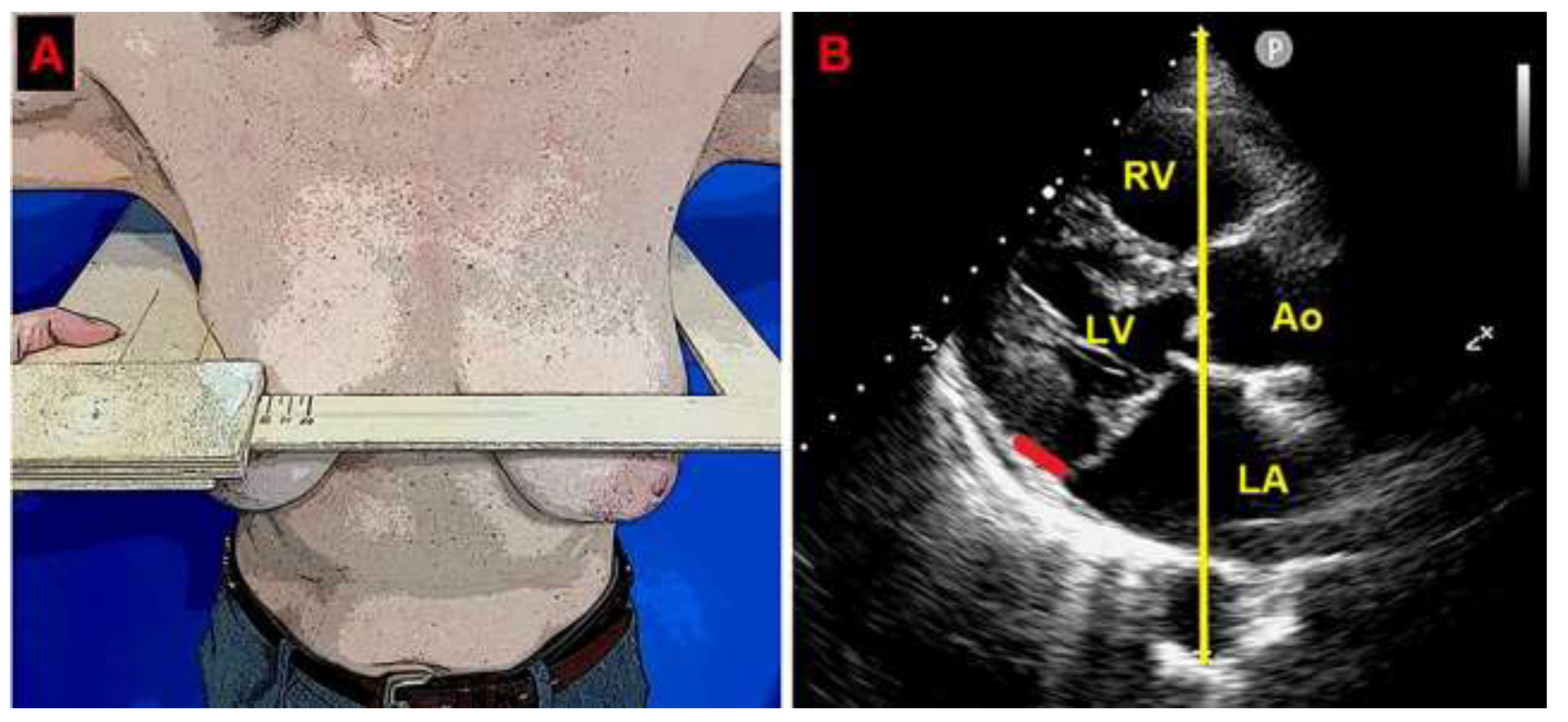

Figure 2); the estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) was 30 mmHg.

On TTE we observed that MAD presence was associated with a narrow A-P thoracic diameter (A-P magnitude = 11 cm), measured as the distance between the true apex of the sector and the posterior wall of the descending aorta. During conventional TTE examination, echocardiographic movies from each of the three apical views (four-chamber, two-chamber and three-chamber) were acquired for the subsequent offline analysis of left ventricular global longitudinal strain (LV-GLS) by speckle tracking echocardiography (STE). LV-GLS was moderately impaired in comparison to the accepted reference values [

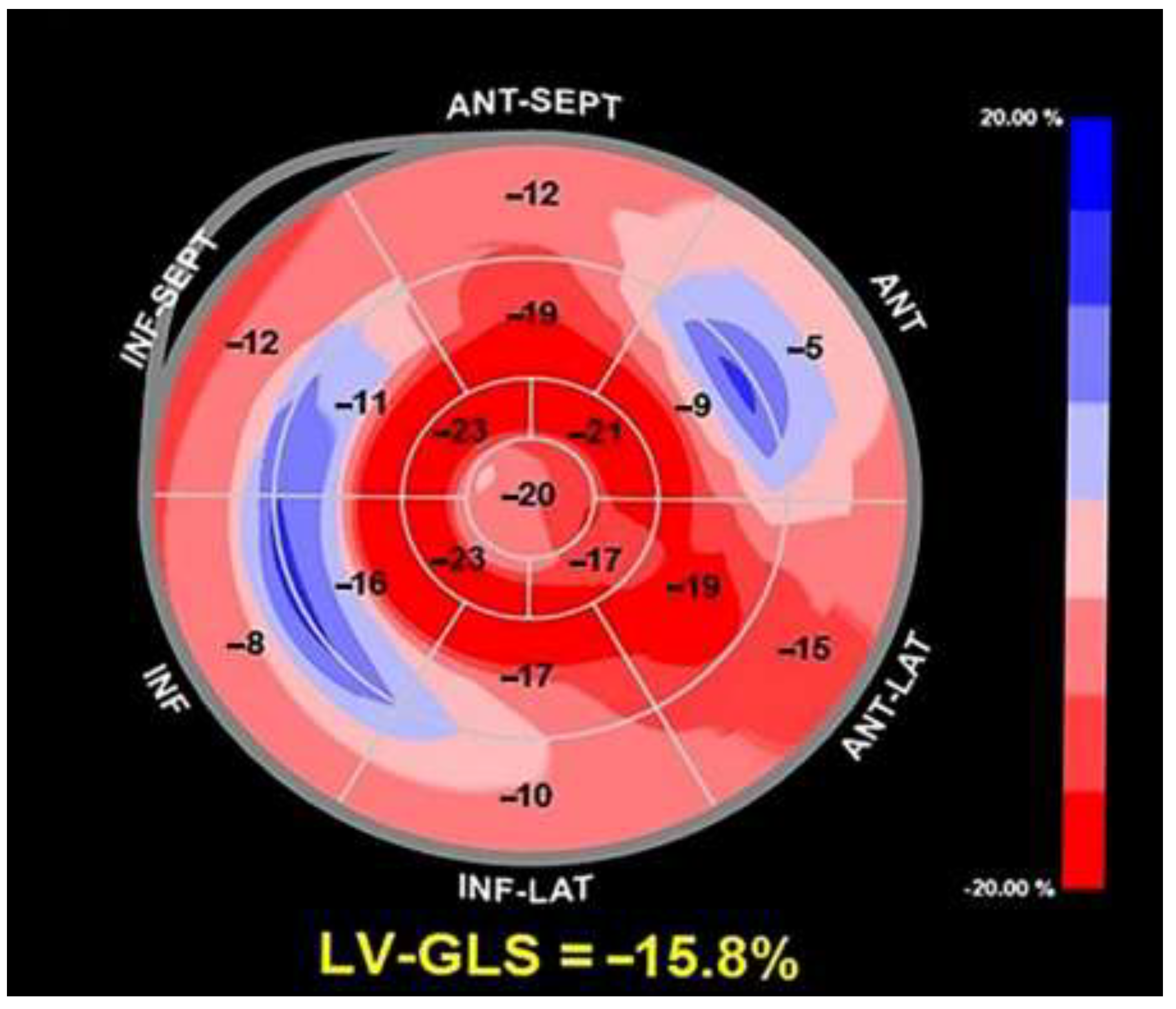

32]. Segmental analysis of LV longitudinal strain showed a significant attenuation of basal and mid longitudinal strain, particularly at level of the LV inferolateral segments, whereas the apical longitudinal strain was normal (apical sparing pattern) (

Figure 3).

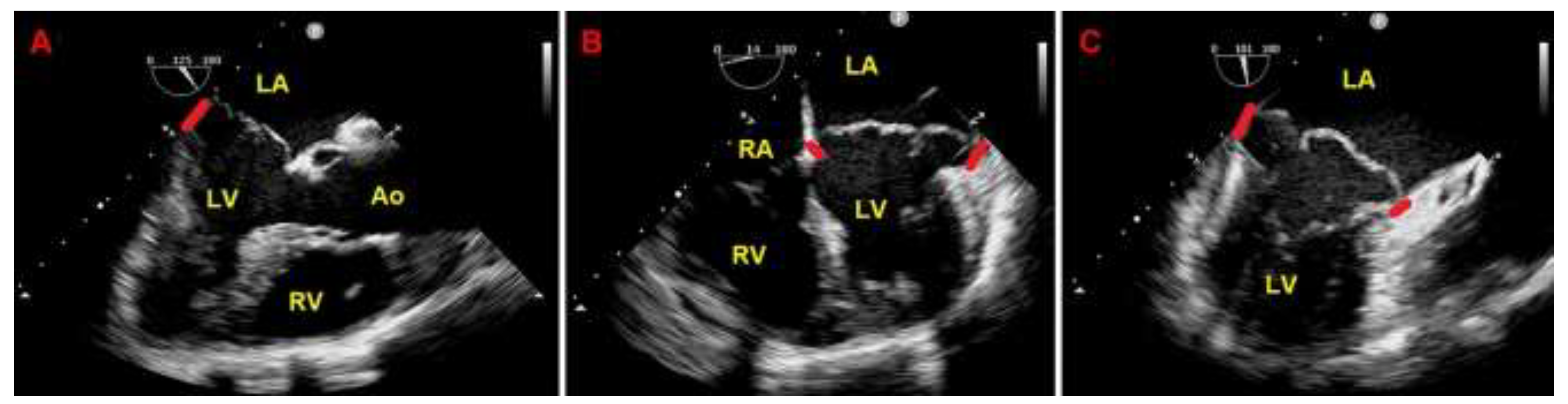

Due to the echocardiographic detection of wide MAD distance and MV floppy degeneration with moderate MR, the patient underwent a diagnostic study comprehensive of TEE, CMR and CCTA. Transesophageal examination (

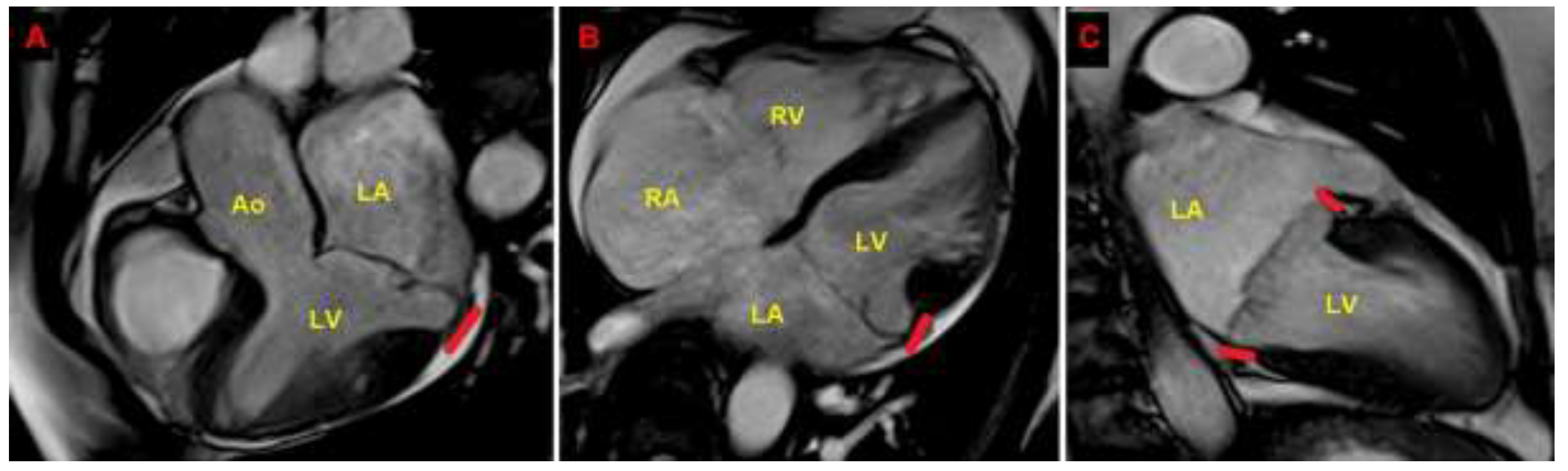

Figure 4), CMR (

Figure 5) and CCTA (

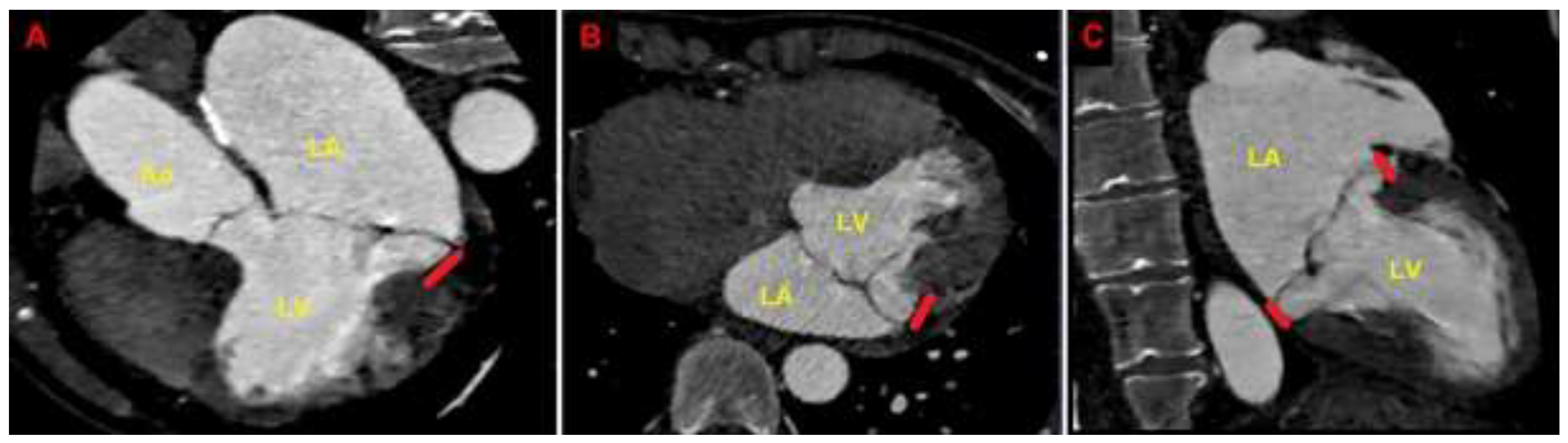

Figure 6) confirmed the bileaflet floppy MVP, the circumferential extension of MAD and the moderate degree of MR. All the imaging techniques were concordant on the MAD presence and its extent.

CMR excluded areas of focal late gadolinium enhancement (LGE). CCTA showed normal coronary arteries.

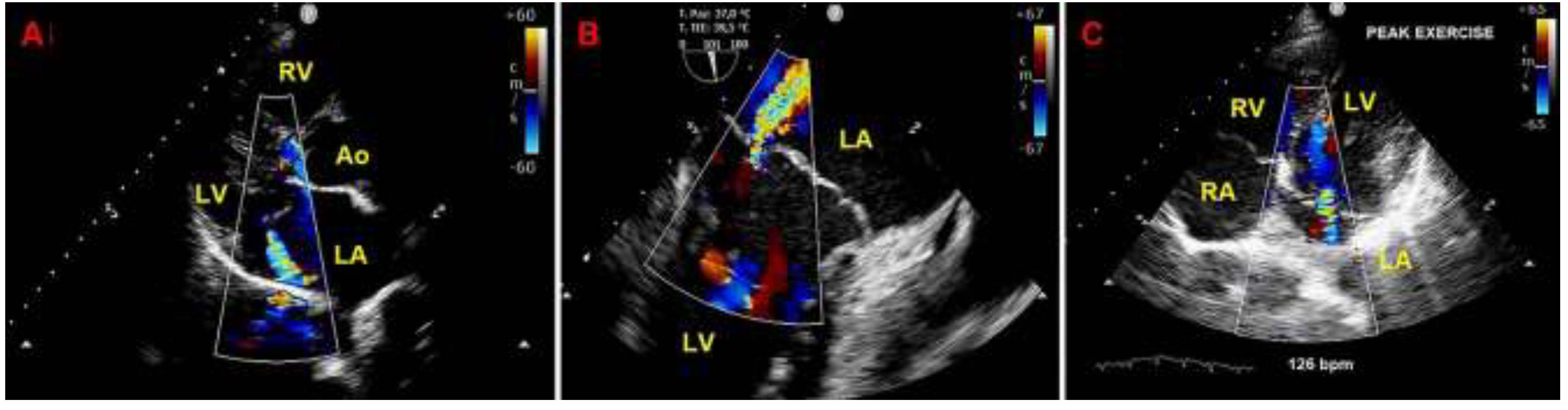

Given that the patient was symptomatic for exercise-induced dyspnea and that we detected a moderate MR due to MVP on both TTE and TEE, she underwent also ESE. On ESE, the patient performed a maximal physical exercise (by achieving 85% of maximal age predicted heart rate), the moderate MR did not show any significant modification in comparison to resting conditions (

Figure 7), the pulmonary hemodynamics was normal (estimated peak exercise sPAP = 45 mmHg), the patient showed a good exercise tolerance and did not manifest palpitations.

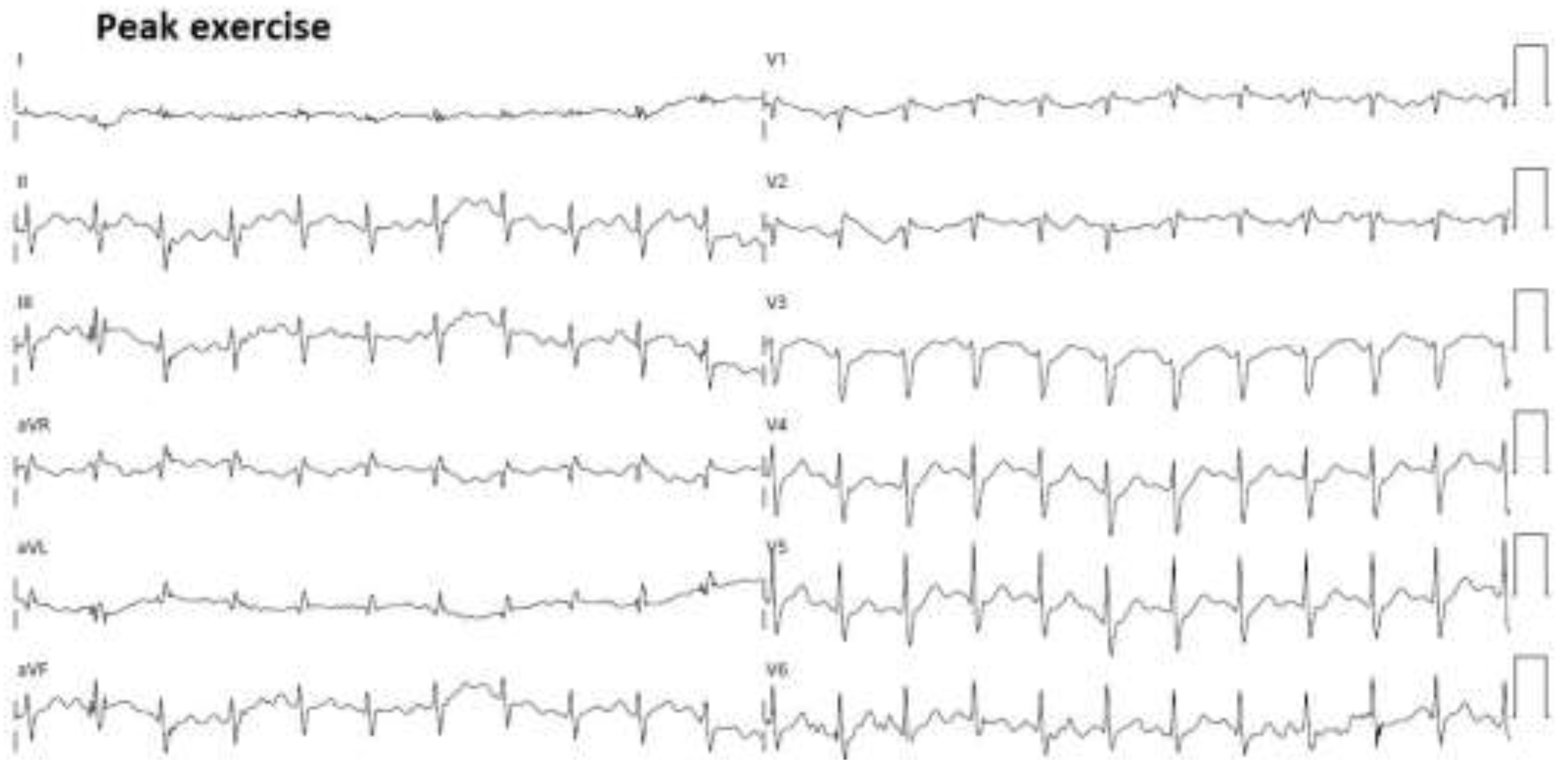

Moreover, the electrocardiographic monitoring during ESE excluded the occurrence of complex VAs or significant ST-T abnormalities (

Figure 8).

The aforementioned multi-instrumental evaluation allowed to detect a potential benign phenotype of MAD, associated with a concave-shaped chest wall conformation (MHI >2.5) and/or a narrow A-P thoracic diameter (<13.5 cm) [

31], with a moderate and non-hemodynamically significant MR and low arrhythmic profile.

3. Discussion

3.1. The role of CMR in MAD assessment

CMR is actually considered the reference imaging modality for detecting MAD [

3,

33]. Due to its high signal-to-noise ratio, excellent blood-myocardium contrast-to-noise ratio, and reproducibility, this imaging modality allows to accurately characterize the MAD presence and extent [

34]. CMR is more sensitive than TTE for detecting small MAD <4 mm and for evaluating the whole circumferential extent of MAD [

14]. Indeed, CMR has an incremental capacity to visualize the posterior MVA and its detachment from the LV wall, over traditional TTE [

35]. MAD causes a typical systolic curling motion of the basal inferolateral LV wall. Both MAD and systolic curling motion are associated with annular hypermobility and paradoxical systolic expansion, that can be appreciated on cine CMR images [

8]. Excessive mobility of the mitral apparatus related to MVP and MAD can induce an abnormal mechanical stress/stretch on the basal inferolateral LV wall and/or the papillary muscles, possibly leading to the development of hypertrophy and fibrosis in these regions [

8,

11,

36]. The greater the MAD extent, the higher the potential arrhythmic risk. With this regard, a MAD length >8.5 mm has been found to predict an increased risk of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia [

7]. LGE sequences allow to detect and precisely quantify these areas of myocardial fibrosis [

11,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Additionally, CMR T1 mapping allow the non-invasive quantification of the myocardial extracellular volume (ECV), a marker of diffuse interstitial myocardial fibrosis [

41,

42]. Despite its advantages in the visualization and characterization of MAD, CMR has a lower spatial and temporal resolution than TTE. For this reason, CMR is less accurate than TTE to assess leaflet thickness and calcifications. Moreover, CMR is less sensitive than TTE to visualize and quantify MR, may be less accurate in patients with arrhythmic disorders and finally is a time-consuming and not easily available and accessible technique [

34].

3.2. The Role Of Echocardiographic Techniques in MAD Assessment

The diagnostic accuracy of TTE and TEE in MAD identification is lower than that provided by CMR, particularly for MAD distance <4 mm, as recently demonstrated by Mantegazza V. et al. [

14]. The lower detection rate of MAD by the echocardiographic techniques may be related to high acoustic impedance, with suboptimal visualization of the posterior mitral valve annulus, or to the presence of posterior MVA calcification causing shadowing or reverberations. When compared to CMR, TTE and to a lesser extent TEE have a tendency to slightly overestimate the MAD distance [

14]. Main advantages of echocardiography are its widespread availability, portable usage, low costs and its excellent capacity to assess MV morphology and to evaluate the haemodynamic consequences of MR [

43,

44]. TEE may provide a better definition of MV anatomy and perivalvular structures. Given its semi-invasive nature, TEE is generally performed only in MAD patients with moderate-to-severe or severe MR before MV surgery [

45].

ESE allows a dynamic evaluation of MR degree associated with MVP and MAD [

45]. A hemodynamically significant exercise-induced increase in mitral regurgitant volume and pulmonary pressures may have a prognostic relevance [

46] and may aid in the decision making process, particularly in patients with discordance between symptoms and regurgitation grade at rest [

47,

48].

Recent evidence indicates that a preliminary chest shape assessment, as noninvasively assessed by the MHI [

31], might improve the prognostic risk stratification of symptomatic MVP patients with moderate MR. A MHI >2.5 or a narrow A-P thoracic diameter (<13.5 cm), due to various degrees of anterior chest wall deformity, are commonly associated with a small left atrial size [

49]. These individuals are commonly encountered in clinical practice and are frequently diagnosed by mild-to-moderate or moderate MR on conventional TTE. However, the severity of valvular heart disease may be overestimated in the presence of small cardiac chambers cavity sizes, particularly the left atrium as the receiving chamber. Indeed, both resting pulmonary hemodynamics and the peak-exercise sPAP are generally normal. Therefore, an apparently moderate MR disease may be more appropriately classified as mild-to-moderate or mild in those individuals with a narrow A-P thoracic diameter. Moreover, MVP patients with a concave-shaped chest wall conformations have a low prevalence of adverse cardiovascular events over a mid-term follow-up [

50].

3.3. The role of CT in MAD assessment

Due to its high spatial resolution, computed tomography (CT) may provide an accurate and highly reproducible evaluation of the mitral annulus and adjacent structures [

51]. Literature data concerning the role of CT scan in MAD assessment are scanty. Putnam AJ et al. [

30] assessed the MAD distance and circumferential extent in retrospectively ECG-gated cardiac CT with reconstruction of all phases throughout the R-R interval [

30], whereas Tsianaka T et al. [

52] performed a prospectively triggered high-pitch

CT angiography study acquired at end-systole, demonstrating the reliability of CT for MAD identification and quantification. CT has the advantages of easy availability, short acquisition time, and ability to view images in any desired plane using multiplanar reconstruction software. The risk of contrast-induced nephropathy and the radiation exposure are the principal limitations of CT.

3.4. The role of chest shape conformation in MVP individuals with MAD

Literature data indicate that MVP individuals are commonly found with various degrees of anterior chest wall deformity, ranging from mild concave-shaped chest wall conformation to severe forms of pectus excavatum [

53,

54]. The strong relationship between MVP and thoracic skeletal abnormalities (TSA) has been related to a defect in growth patterns at around the 5th to 6th week of gestation affecting both the MV and the bony thorax [

53,

55]. Additionally, MVP is genetically associated with systemic connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers Danlos syndrome [

56]. Accordingly, the association between MVP and TSA is likely related to developmental or genetic factors.

Considering the strong association between MVP and TSA and the increased prevalence of MAD among MVP individuals [

3,

7,

12,

19,

26,

27,

28,

29], our study group hypothesized that MAD presence might be more frequently detected among individuals with a narrow A-P thoracic diameter and/or concave-shaped chest wall conformation. We previously demonstrated that, compared to MAD- patients, MAD+ patients had significantly greater MHI, significantly shorter A-P thoracic diameter, significantly smaller cardiac chambers cavity sizes and significantly lower magnitude of both longitudinal and circumferential myocardial strain parameters, particularly at the level of basal myocardial segments, with apical sparing [

17]. The degree of strain impairment was strongly correlated to the degree of anterior chest wall deformity: the narrower the A-P thoracic diameter, the lower the myocardial strain magnitude in both longitudinal and circumferential direction, especially at basal level. These findings would indicate the important role exerted by the anterior chest wall deformity on inducing an extrinsic compression of cardiac chambers, on restricting LV kinetics of basal myocardial segments and causing intraventricular and/or interventricular dyssynergies. The attenuation of myocardial strain parameters was detected in the presence of preserved biventricular systolic function, as assessed by LVEF and TAPSE, thus excluding intrinsic myocardial dysfunction. The absence of intrinsic cardiomyopathy is further supported by the preservation of the typical “base-to-apex gradient” (lowest to highest) of LV strain in MAD+ patients, whose impairment is characteristic of pathological states [

57]. We also reported that MVP and MAD+ patients with MHI >2.5 or A-P thoracic diameter <13.5 cm had a low prevalence of complex VAs and a good outcome over a mid-term follow-up period [

58]. Based on these findings and as demonstrated in the illustrated clinical case, we have hypothesized the existence of a cluster of patients with a benign phenotype of MAD, represented by individuals with a narrow A-P thoracic diameter (<13.5 cm), without LGE on CMR, without detectable complex VAs, with mild-to-moderate and non-hemodynamically significant MR due to MVP, with normal biventricular systolic function and with reduced basal longitudinal strain with apical sparing. It could be then important to design high-powered multicentered prospective studies to evaluate the prognosis of MAD+ patients with a concave-shaped chest wall conformation over a mid-to-long term follow-up.

4. Conclusions

Not all MVP patients with MAD have an increased arrhythmogenic substrate.

MAD patients with a narrow A-P thoracic diameter may be found with non-hemodynamically significant MR, without LGE on CMR and without detectable complex VAs.

The assessment of chest shape conformation might improve the prognostic risk stratification of MAD+ patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., M.L and G.L.N..; methodology, A.S., G.L.N., G.E.U.M.S. and G.A.R.; software, A.S., G.E.U.M.S. and G.A.R.; validation, M.L.; formal analysis, A.S., G.L.N., M.L. and G.E.U.M.S.; investigation, A.S.; resources, P.M.; data curation, A.S. and G.E.U.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S., G.L.N. and G.E.U.M.S.; visualization, G.L.N., G.E.U.M.S. and M.L.; supervision, M.L. and P.M..; project administration, P.M.; funding acquisition, P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health, Ricerca Corrente IRCCS MultiMedica.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In accordance with the guidelines by the Comitato Etico Territoriale Lombardia 5, ethical review and approval were not required for this case report.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the individual included in the present case report.

Data Availability Statement

Data extracted from the present case report will be publicly available on Zenodo (

https://zenodo.org), pending the acceptance by the journal.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Monica Fumagalli for graphical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Van der Bijl, P.; Stassen, J.; Haugaa, K.H.; Essayagh, B.; Basso, C.; Thiene, G.; Faletra, F.F.; Edvardsen, T.; Enriquez-Sarano, M.; Nihoyannopoulos, P.; et al. Mitral Annular Disjunction in the Context of Mitral Valve Prolapse: Identifying the At-Risk Patient. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2024, 17, 1229-1245. [CrossRef]

- Cesmat, A.P.; Chaudry, A.M.; Gupta, S.; Sivaraj, K.; Weickert, T.T.; Simpson, R.J. Jr; Syed, F.F. Prevalence and predictors of mitral annular disjunction and ventricular ectopy in mitral valve prolapse. Heart Rhythm. 2024, 21, 1803-1810. [CrossRef]

- Figliozzi, S.; Stankowski, K.; Tondi, L.; Catapano, F.; Gitto, M.; Lisi, C.; Bombace, S.; Olivieri, M.; Cannata, F.; Fazzari, F.; et al. Mitral Annulus Disjunction in consecutive patients undergoing Cardiac Magnetic Resonance: where is the boundary between normality and disease? J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2024, 26, 101056. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.P.; Jin, C.N.; Fan, Y.; Wong, R.H.L.; Underwood, M.J.; Wan, S. Functional Implication of Mitral Annular Disjunction in Mitral Valve Prolapse: A Quantitative Dynamic 3D Echocardiographic Study. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2017, 10, 1424-1433. [CrossRef]

- Dejgaard, L.A.; Skjølsvik, E.T.; Lie, Ø.H.; Ribe, M.; Stokke, M.K.; Hegbom, F.; Scheirlynck, E.S.; Gjertsen, E.; Andresen, K.; Helle-Valle, T.M.; et al. The Mitral Annulus Disjunction Arrhythmic Syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 1600-1609. [CrossRef]

- Angelini, A.; Ho, S.Y.; Anderson, R.H.; Becker, A.E.; Davies, M.J. Disjunction of the mitral annulus in floppy mitral valve. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 318, 188-9. [CrossRef]

- Carmo, P.; Andrade, M.J.; Aguiar, C.; Rodrigues, R.; Gouveia, R.; Silva, J.A. Mitral annular disjunction in myxomatous mitral valve disease: a relevant abnormality recognizable by transthoracic echocardiography. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound. 2010, 8, 53. [CrossRef]

- Perazzolo Marra, M.; Basso, C.; De Lazzari, M.; Rizzo, S.; Cipriani, A.; Giorgi, B.; Lacognata, C.; Rigato, I.; Migliore, F.; Pilichou, K.; et al. Morphofunctional Abnormalities of Mitral Annulus and Arrhythmic Mitral Valve Prolapse. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2016, 9, e005030. [CrossRef]

- Han, H.C.; Ha, F.J.; The, A.W.; Calafiore, P.; Jones, E.F.; Johns, J.; Koshy, A.N.; O'Donnell, D.; Hare, D.L.; Farouque, O.; et al. Mitral Valve Prolapse and Sudden Cardiac Death: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e010584. [CrossRef]

- Essayagh, B.; Iacuzio, L.; Civaia, F.; Avierinos, J.F.; Tribouilloy, C.; Levy, F. Usefulness of 3-Tesla Cardiac Magnetic Resonance to Detect Mitral Annular Disjunction in Patients With Mitral Valve Prolapse. Am. J. Cardiol. 2019, 124, 1725-1730. [CrossRef]

- Basso, C.; Perazzolo Marra, M.; Rizzo, S.; De Lazzari, M.; Giorgi, B.; Cipriani, A.; Frigo, A.C.; Rigato, I.; Migliore, F.; Pilichou, K.; et al. Arrhythmic Mitral Valve Prolapse and Sudden Cardiac Death. Circulation. 2015, 132, 556-66. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.J.; Bitkover, C.Y.; Omran, A.S.; David, T.E.; Ivanov, J.; Ali, M.J.; Woo, A.; Siu, S.C.; Rakowski, H. Mitral annular disjunction in advanced myxomatous mitral valve disease: echocardiographic detection and surgical correction. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2005, 18, 1014-22. [CrossRef]

- Mantegazza, V.; Tamborini, G.; Muratori, M.; Gripari, P.; Fusini, L.; Italiano, G.; Volpato, V.; Sassi, V.; Pepi, M. Mitral Annular Disjunction in a Large Cohort of Patients With Mitral Valve Prolapse and Significant Regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2019, 12, 2278-2280. [CrossRef]

- Mantegazza, V.; Volpato, V.; Gripari, P.; Ghulam Ali, S.; Fusini, L.; Italiano, G.; Muratori, M.; Pontone, G.; Tamborini, G.; Pepi, M. Multimodality imaging assessment of mitral annular disjunction in mitral valve prolapse. Heart. 2021, 107, 25-32. [CrossRef]

- Essayagh, B.; Sabbag, A.; Antoine, C.; Benfari, G.; Batista, R.; Yang, L.T.; Maalouf, J.; Thapa, P.; Asirvatham, S.; Michelena, H.I.; et al. The Mitral Annular Disjunction of Mitral Valve Prolapse: Presentation and Outcome. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2021, 14, 2073-2087. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.; Tafuro, J.; Brumpton, M.; Bardolia, C.; Heatlie, G.; Duckett, S.; Ridley, P.; Nanjaiah, P.; Kwok, C.S. Echocardiographic description and outcomes in a heterogeneous cohort of patients undergoing mitral valve surgery with and without mitral annular disjunction: a health service evaluation. Echo Res. Pract. 2022, 9, 4. [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Rigamonti, E.; Lombardo, M. The influence of chest wall conformation on myocardial strain parameters in a cohort of mitral valve prolapse patients with and without mitral annular disjunction. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2023, 39, 61-76. [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Indraratna, P.; Cranney, G.; Lam, H.; Yu, J.; Mathur, G. Mitral annular disjunction in surgical mitral valve prolapse: prevalence; characteristics and outcomes. Echo Res. Pract. 2023, 10, 21. [CrossRef]

- Vaksmann, G.; Bouzguenda, I.; Guillaume, M.P.; Gras, P.; Silvestri, V.; Richard, A. Mitral annular disjunction and Pickelhaube sign in children with mitral valve prolapse: A prospective cohort study. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 116, 514-522. [CrossRef]

- Shechter, A.; Vaturi, M.; Hong, G.J.; Kaewkes, D.; Patel, V.; Seok, M.; Nagasaka, T.; Koren, O.; Koseki, K.; Skaf, S.; et al. Implications of Mitral Annular Disjunction in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Edge-to-Edge Repair for Degenerative Mitral Regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2023, 16, 2835-2849. [CrossRef]

- Özyıldırım, S.; Guven, B.; Yumuk, M.T.; Barman, H.A.; Dogan, O.; Topel, C.; Atici, A.; Donmez, A.; Kucukoglu, M.S.; Dogan, S.M. Evaluation of left ventricular function in patients with mitral annular disjunction using speckle tracking echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2024, 41, e15813. [CrossRef]

- Meucci, M.C.; Mantegazza, V.; Wu, H.W.; van Wijngaarden, A.L.; Garlaschè, A.; Tamborini, G.; Pepi, M.; Bax, J.J.; Ajmone Marsan, N. Structural and functional abnormalities of left-sided cardiac chambers in Barlow's disease without significant mitral regurgitation. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2024, 25, 1296-1305. [CrossRef]

- Cesmat, A.P.; Chaudry, A.M.; Gupta, S.; Sivaraj, K.; Weickert, T.T.; Simpson, R.J. Jr; Syed, F.F. Prevalence and predictors of mitral annular disjunction and ventricular ectopy in mitral valve prolapse. Heart Rhythm. 2024, 21, 1803-1810. [CrossRef]

- Biondi, R.; Ribeyrolles, S.; Diakov, C.; Amabile, N.; Ricciardi, G.; Khelil, N.; Berrebi, A.; Zannis, K. Mapping of the myxomatous mitral valve: The three-dimensional extension of mitral annular disjunction in surgically repaired mitral prolapse. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1036400. [CrossRef]

- Essayagh, B.; Iacuzio, L.; Civaia, F.; Avierinos, J.F.; Tribouilloy, C.; Levy, F. Usefulness of 3-Tesla Cardiac Magnetic Resonance to Detect Mitral Annular Disjunction in Patients With Mitral Valve Prolapse. Am. J. Cardiol. 2019, 124, 1725-1730. [CrossRef]

- Figliozzi, S.; Georgiopoulos, G.; Lopes, P.M.; Bauer, K.B.; Moura-Ferreira, S.; Tondi, L.; Mushtaq, S.; Censi, S.; Pavon, A.G.; Bassi, I.; et al. Myocardial Fibrosis at Cardiac MRI Helps Predict Adverse Clinical Outcome in Patients with Mitral Valve Prolapse. Radiology. 2023, 306, 112-121. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Bhagia, G.; Doyle, M.; Rayarao, G.; Williams, R.B.; Biederman, R.W.W. Mitral annular disjunction; how accurate are we? A cardiovascular MRI study defining risk. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2023, 49, 101298. [CrossRef]

- Perazzolo Marra, M.; Cecere, A.; Cipriani, A.; Migliore, F.; Zorzi, A.; De Lazzari, M.; Lorenzoni, G.; Cecchetto, A.; Brunetti, G.; Graziano, F.; et al. Determinants of Ventricular Arrhythmias in Mitral Valve Prolapse. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2024, 10, 670-681. [CrossRef]

- Blondeel, M.; L'Hoyes, W.; Robyns, T.; Verbrugghe, P.; De Meester, P.; Dresselaers, T.; Masci, P.G.; Willems, R.; Bogaert, J.; Vandenberk, B. Serial Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients with Mitral Valve Prolapse-A Single-Center Retrospective Registry. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2669. [CrossRef]

- Putnam, A.J.; Kebed, K.; Mor-Avi, V.; Rashedi, N.; Sun, D.; Patel, B.; Balkhy, H.; Lang, R.M.; Patel, A.R. Prevalence of mitral annular disjunction in patients with mitral valve prolapse and severe regurgitation. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2020, 36, 1363-1370. [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Baravelli, M.; Vincenti, A.; Trevisan, R.; Zompatori, M.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Lombardo, M.; Anzà, C. A New modified anthropometric haller index obtained without radiological exposure. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2018, 34, 1505-1509. [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, M.; Cosyns, B.; Edvardsen, T.; Cardim, N.; Delgado, V.; Di Salvo, G.; Donal, E.; Sade, L.E.; Ernande, L.; Garbi, M.; et al. Standardization of adult transthoracic echocardiography reporting in agreement with recent chamber quantification, diastolic function, and heart valve disease recommendations: an expert consensus document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2017, 18, 1301-1310. [CrossRef]

- Haugaa, K. Improving the imaging diagnosis of mitral annular disjunction. Heart. 2021, 107, 4-5. [CrossRef]

- Vermes, E.; Altes, A.; Iacuzio, L.; Levy, F.; Bohbot, Y.; Renard, C.; Grigioni, F.; Maréchaux, S.; Tribouilloy, C. The evolving role of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the assessment of mitral valve prolapse. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1093060. [CrossRef]

- Faletra, F.F.; Leo, L.A.; Paiocchi, V.L.; Caretta, A.; Viani, G.M.; Schlossbauer, S.A.; Demertzis, S.; Ho, S.Y. Anatomy of mitral annulus insights from non-invasive imaging techniques. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2019, 20, 843-857. [CrossRef]

- Morningstar, J.E.; Gensemer, C.; Moore, R.; Fulmer, D.; Beck, T.C.; Wang, C.; Moore, K.; Guo, L.; Sieg, F.; Nagata, Y.; et al. Mitral Valve Prolapse Induces Regionalized Myocardial Fibrosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e022332. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Peters, D.C.; Salton, C.J.; Bzymek, D.; Nezafat, R.; Goddu, B.; Kissinger, K.V.; Zimetbaum, P.J.; Manning, W.J.; Yeon, S.B. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance characterization of mitral valve prolapse. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2008, 1, 294-303. [CrossRef]

- Romero Daza, A.; Chokshi, A.; Pardo, P.; Maneiro, N.; Guijarro Contreras, A.; Larrañaga-Moreira, J.M.; Ibañez, B.; Fuster, V.; Fernández Friera, L.; Solís, J.; et al. Mitral valve prolapse morphofunctional features by cardiovascular magnetic resonance: more than just a valvular disease. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2021, 23, 107. [CrossRef]

- Kitkungvan, D.; Nabi, F.; Kim, R.J.; Bonow, R.O.; Khan, M.A.; Xu, J.; Little, S.H.; Quinones, M.A.; Lawrie, G.M.; Zoghbi, W.A.; et al. Myocardial Fibrosis in Patients With Primary Mitral Regurgitation With and Without Prolapse. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 823-834. [CrossRef]

- Constant Dit Beaufils, A.L.; Huttin, O.; Jobbe-Duval, A.; Senage, T.; Filippetti, L.; Piriou, N.; Cueff, C.; Venner, C.; Mandry, D.; Sellal, J.M.; et al. Replacement Myocardial Fibrosis in Patients With Mitral Valve Prolapse: Relation to Mitral Regurgitation, Ventricular Remodeling, and Arrhythmia. Circulation. 2021, 143, 1763-1774. [CrossRef]

- de Meester de Ravenstein, C.; Bouzin, C.; Lazam, S.; Boulif, J.; Amzulescu, M.; Melchior, J.; Pasquet, A.; Vancraeynest, D.; Pouleur, A.C.; Vanoverschelde, J.L.; et al. Histological Validation of measurement of diffuse interstitial myocardial fibrosis by myocardial extravascular volume fraction from Modified Look-Locker imaging (MOLLI) T1 mapping at 3 T. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2015, 17, 48. [CrossRef]

- Fontana, M.; White, S.K.; Banypersad, S.M.; Sado, D.M.; Maestrini, V.; Flett, A.S.; Piechnik, S.K.; Neubauer, S.; Roberts, N.; Moon, J.C. Comparison of T1 mapping techniques for ECV quantification. Histological validation and reproducibility of ShMOLLI versus multibreath-hold T1 quantification equilibrium contrast CMR. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2012, 14, 88. [CrossRef]

- Pepi, M.; Tamborini, G.; Maltagliati, A.; Galli, C.A.; Sisillo, E.; Salvi, L.; Naliato, M.; Porqueddu, M.; Parolari, A.; Zanobini, M.; et al. Head-to-head comparison of two- and three-dimensional transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography in the localization of mitral valve prolapse. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 48, 2524-30. [CrossRef]

- Gripari, P.; Muratori, M.; Fusini, L.; Tamborini, G.; Pepi, M. Three-Dimensional Echocardiography: Advancements in Qualitative and Quantitative Analyses of Mitral Valve Morphology in Mitral Valve Prolapse. J. Cardiovasc. Echogr. 2014, 24, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Vahanian, A.; Beyersdorf, F.; Praz, F.; Milojevic, M.; Baldus, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Capodanno, D.; Conradi, L.; De Bonis, M.; De Paulis, R.; et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 561-632. [CrossRef]

- Picano, E.; Pibarot, P.; Lancellotti, P.; Monin, J.L.; Bonow, R.O. The emerging role of exercise testing and stress echocardiography in valvular heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 2251-60. [CrossRef]

- Bakkestrøm, R.; Banke, A.; Christensen, N.L.; Pecini, R.; Irmukhamedov, A.; Andersen, M.; Borlaug, B.A.; Møller, J.E. Hemodynamic Characteristics in Significant Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Primary Mitral Valve Regurgitation at Rest and During Exercise. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2018, 11, e007171. [CrossRef]

- Utsunomiya, H.; Hidaka, T.; Susawa, H.; Izumi, K.; Harada, Y.; Kinoshita, M.; Itakura, K.; Masada, K.; Kihara, Y. Exercise-Stress Echocardiography and Effort Intolerance in Asymptomatic/Minimally Symptomatic Patients With Degenerative Mitral Regurgitation Combined Invasive-Noninvasive Hemodynamic Monitoring. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2018, 11, e007282. [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Trevisan, R.; Lombardo, M.; Grasso, E.; Gensini, G.F.; Ambrosio, G. The influence of pectus excavatum on cardiac kinetics and function in otherwise healthy individuals: A systematic review. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 381, 135-144. [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Rigamonti, E.; Lombardo, M. Impact of Chest Wall Conformation on the Outcome of Primary Mitral Regurgitation due to Mitral Valve Prolapse. J. Cardiovasc. Echogr. 2022, 32, 29-37. [CrossRef]

- Blanke, P.; Dvir, D.; Cheung, A.; Ye, J.; Levine, R.A.; Precious, B.; Berger, A.; Stub, D.; Hague, C.; Murphy, D.; et al. A simplified D-shaped model of the mitral annulus to facilitate CT-based sizing before transcatheter mitral valve implantation. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2014, 8, 459-67. [CrossRef]

- Tsianaka, T.; Matziris, I.; Kobe, A.; Euler, A.; Kuzo, N.; Erhart, L.; Leschka, S.; Manka, R.; Kasel, A.M.; Tanner, F.C.; et al. Mitral annular disjunction in patients with severe aortic stenosis: Extent and reproducibility of measurements with computed tomography. Eur. J. Radiol. Open. 2021, 8, 100335. [CrossRef]

- Udoshi, M.B.; Shah, A.; Fisher, V.J.; Dolgin, M. Incidence of mitral valve prolapse in subjects with thoracic skeletal abnormalities--a prospective study. Am. Heart J. 1979, 97, 303-11. [CrossRef]

- Movahed, A.; Majdalany, D.; Gillinov, M.; Schiavone, W. Association Between Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease and Skeletal Back Abnormalities. J. Heart Valve Dis. 2017, 26, 564-568.

- Nomura, K.; Ajiro, Y.; Nakano, S.; Matsushima, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Hatakeyama, N.; Ohata, M.; Sakuma, M.; Nonaka, T.; Harii, M.; et al. Characteristics of mitral valve leaflet length in patients with pectus excavatum: A single center cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0212165. [CrossRef]

- Boudoulas, K.D.; Pitsis, A.A.; Mazzaferri, E.L.; Gumina, R.J.; Triposkiadis, F.; Boudoulas, H. Floppy mitral valve/mitral valve prolapse: A complex entity with multiple genotypes and phenotypes. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 308-326. [CrossRef]

- Bijnens, B.H.; Cikes, M.; Claus, P.; Sutherland, G.R. Velocity and deformation imaging for the assessment of myocardial dysfunction. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2009, 10, 216-26. [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Rigamonti, E.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Lombardo, M. Prognostic Value of Modified Haller Index in Patients with Suspected Coronary Artery Disease Referred for Exercise Stress Echocardiography. J. Cardiovasc. Echogr. 2021, 31, 85-95. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Modified Haller index, obtained by dividing the latero-lateral thoracic diameter (measured by a rigid ruler coupled to a level) by the antero-posterior thoracic diameter (measured from the echocardiographic parasternal long-axis view, as the distance between the true apex of the sector and the posterior wall of the descending aorta). The bold red line indicates the MAD distance. The bold yellow line indicates the antero-posterior thoracic diameter. Ao, aorta; LA; left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MAD, mitral annular disjunction; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 1.

Modified Haller index, obtained by dividing the latero-lateral thoracic diameter (measured by a rigid ruler coupled to a level) by the antero-posterior thoracic diameter (measured from the echocardiographic parasternal long-axis view, as the distance between the true apex of the sector and the posterior wall of the descending aorta). The bold red line indicates the MAD distance. The bold yellow line indicates the antero-posterior thoracic diameter. Ao, aorta; LA; left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MAD, mitral annular disjunction; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 2.

Transthoracic echocardiography. MAD assessment at end-systole from the parasternal long-axis view (A), from the apical four-chamber view (B) and from the apical two-chamber view (C). The bold red line indicates the MAD distance. Ao, aorta; LA; left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MAD, mitral annular disjunction; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 2.

Transthoracic echocardiography. MAD assessment at end-systole from the parasternal long-axis view (A), from the apical four-chamber view (B) and from the apical two-chamber view (C). The bold red line indicates the MAD distance. Ao, aorta; LA; left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MAD, mitral annular disjunction; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 3.

Bull's-eye plot illustrating the regional longitudinal strain at basal, mid and apical level along with LV-GLS magnitude. LV-GLS was moderately impaired, particularly at basal and mid level, with apical sparing. LV-GLS, left ventricular-global longitudinal strain.

Figure 3.

Bull's-eye plot illustrating the regional longitudinal strain at basal, mid and apical level along with LV-GLS magnitude. LV-GLS was moderately impaired, particularly at basal and mid level, with apical sparing. LV-GLS, left ventricular-global longitudinal strain.

Figure 4.

Transesophageal echocardiography. MAD assessment at end-systole from the mid-esophageal three-chamber view (A), four-chamber view (B) and two-chamber view (C). The bold red line indicates the MAD distance. Ao, aorta; LA; left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MAD, mitral annular disjunction; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle. (A) is reproduced from the paper 10.3390/jcm14051423.

Figure 4.

Transesophageal echocardiography. MAD assessment at end-systole from the mid-esophageal three-chamber view (A), four-chamber view (B) and two-chamber view (C). The bold red line indicates the MAD distance. Ao, aorta; LA; left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MAD, mitral annular disjunction; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle. (A) is reproduced from the paper 10.3390/jcm14051423.

Figure 5.

Cardiac magnetic resonance. MAD assessment at end-systole from the three-chamber view (A), four-chamber view (B) and two-chamber view (C). The bold red line indicates the MAD distance. Ao, aorta; LA; left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MAD, mitral annular disjunction; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle. (A) is reproduced from the paper 10.3390/jcm14051423.

Figure 5.

Cardiac magnetic resonance. MAD assessment at end-systole from the three-chamber view (A), four-chamber view (B) and two-chamber view (C). The bold red line indicates the MAD distance. Ao, aorta; LA; left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MAD, mitral annular disjunction; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle. (A) is reproduced from the paper 10.3390/jcm14051423.

Figure 6.

Cardiac computed tomography angiography. MAD assessment at end-systole from the multiplanar reconstructed three-chamber view (A), four-chamber view (B) and two-chamber view (C). The bold red line indicates the MAD distance. Ao, aorta; LA; left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MAD, mitral annular disjunction. (A) is reproduced from the paper 10.3390/jcm14051423.

Figure 6.

Cardiac computed tomography angiography. MAD assessment at end-systole from the multiplanar reconstructed three-chamber view (A), four-chamber view (B) and two-chamber view (C). The bold red line indicates the MAD distance. Ao, aorta; LA; left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MAD, mitral annular disjunction. (A) is reproduced from the paper 10.3390/jcm14051423.

Figure 7.

Moderate mitral regurgitation detected on resting transthoracic echocardiography from the parasternal long-axis view (A), on transesophageal echocardiography from the bicommissural view (B) and on exercise stress echocardiography from the apical four-chamber view recorded at peak exercise (C). Ao, aorta; LA; left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 7.

Moderate mitral regurgitation detected on resting transthoracic echocardiography from the parasternal long-axis view (A), on transesophageal echocardiography from the bicommissural view (B) and on exercise stress echocardiography from the apical four-chamber view recorded at peak exercise (C). Ao, aorta; LA; left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 8.

12-lead ECG obtained at peak exercise during exercise stress echocardiography. ECG, electrocardiogram.

Figure 8.

12-lead ECG obtained at peak exercise during exercise stress echocardiography. ECG, electrocardiogram.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).