1. Introduction

As socio-economic structures continue to evolve and cultural diversity deepens, the demands for interior space design have become increasingly intricate and multifaceted. Over the past several decades, research in interior space design has predominantly focused on functional layouts and spatial morphology, with relatively limited attention given to the interaction between individuals and the spatial environment, as well as the creation of spaces that provide profound experiential value[

1,

2]. Traditional spatial design has typically emphasized functionality and aesthetic value. However, with the growing recognition of the significance of sensory experiences, scholars have increasingly focused on how design can address multi-sensory needs to enhance the overall perceptual experience of space.

Research across various disciplines indicates that spatial perception is inherently closely linked to the body[

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The body possesses agency in the perceptual process; it is not merely a passive recipient of sensory stimuli, but an active participant that engages with the environment and constructs self-awareness[

8]. In this process, sensory perception regulates the relationship between the body, mind, cognition, and the environment[

9]. Human social interactions and self-perception are inseparable from the integration of multi-sensory information. Gibson et al. argue that social interaction is not solely dependent on verbal communication but is profoundly influenced by multi-sensory and bodily perceptions[

10]. This multi-sensory integration not only shapes interpersonal interactions but also directly influences an individual's perception and cognition of the environment. Sensory information received from the surrounding environment has a significant impact on our perceptions and behaviors[

11]. Visual perception serves as a fundamental sensory input for spatial perception[

1]; however, spatial experience transcends visual perception, encompassing a multi-dimensional and integrative process of perception. The comprehensive stimulation of auditory, tactile, and olfactory senses compensates for the limitations of visual perception, collectively shaping a profound multi-sensory experience that seamlessly integrates the individual with their environment[

12].

In recent years, scholars have delved deeper into the exploration of multi-sensory experiences within space, with particular emphasis on the creation of spatial ambiance. Atmosphere is the subjective reflection arising from the multi-sensory integration of various perceivable elements within a space[

13]. Dai et al. (2021) argue that multi-sensory spatial perception plays a crucial role in shaping the emotional ambiance of public spaces[

14]. Within the theoretical framework of multi-sensory anthropology, the senses are not merely manifestations of physiological function; they are deeply embedded in social norms, cultural expressions, and interpersonal interactions[

15]. Multi-sensory experiences not only enhance the depth of perception but also directly shape how individuals interact with others, perceive space, and even form their identity and cultural affiliation[

15]. Within this theoretical framework, space is regarded as a complex perceptual system, not merely a physical environment that accommodates objects and activities, but also a setting that stimulates emotional and cognitive responses. Numerous scholars have pointed out that sensory stimuli in spatial design, by modulating the perceptual process, not only shape emotional responses but also profoundly influence the formation and evolution of behavioral patterns[

16]. For example, Tony Hiss in

The Experience of Place emphasizes that the atmosphere, emotional responses, and behavioral reactions of a space are all the result of the interplay of multiple sensory influences[

17]. He notes that the combined effects of factors such as lighting, temperature, texture, and sound not only influence individuals' physiological states but also evoke emotional resonance. These studies demonstrate that atmosphere plays a critical role in shaping emotional responses; it not only influences how individuals perceive space but also directly determines their emotional experience within it[

18].

Consequently, the goal of modern interior spatial design has shifted from mere functionality to the comprehensive enhancement of sensory experiences. Designers harness the synergistic effect of multiple senses to improve spatial ambiance, thereby strengthening users' emotional connection and sense of belonging. Research indicates that in retail environments, the stimulation of the senses through atmospheric elements such as visual effects, sound management, material textures, and ambient scents can significantly enhance both the spatial appeal and the perceived comfort of the space[

19]. The interactivity and resonance of sensory stimuli enable design to transcend traditional aesthetic and functional requirements, deepening users' spatial experience through emotional transmission and psychological cues. The integration of sensory elements such as vision, hearing, and touch to create environments that are both emotionally profound and spatially captivating has become a central topic in contemporary interior spatial design and a key approach to enhancing the overall quality of spatial experiences.

This study aims to explore the optimization of sensory experiences within interior spaces through the analysis of multisensory design strategies rooted in spatial perception theory. Using a coffee roasting factory in Suzhou as a design case, a series of design methodologies are proposed that engage visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, and gustatory senses. The effectiveness of these strategies is then evaluated through their application in the actual design process. Specifically, the research objectives include:

Through case study analysis, this research explores the relevant concepts, characteristics, and the subject-object relationship of spatial perception;

Analyze how different sensory design elements (such as vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste) collaborate in spatial design to enhance the sensory experience of the space;

Propose a set of practical design methods and strategies for interior spatial perception, providing theoretical support and methodological guidance for future design practices.

The contribution of this paper lies in providing a new perspective on interior design through the application framework of multi-sensory design, and in validating the practicality of spatial perception theory through real-world case studies. By analyzing the sensory design strategies at different spatial nodes, this study provides empirical data for research in the field of interior design and contributes to the further development of spatial perception theory within interior design.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Concepts Related to Spatial Perception

Spatial perception serves as the core theoretical framework in interior spatial design, providing both scientific foundations and philosophical perspectives for understanding the relationship between individuals and space. As a fundamental concept in design, space encompasses functional, emotional, and socio-cultural significance, acting as a bridge between the material world and human experience. In

The Sense of Space, Morris argues that we perceive not only the spatial relationships between ourselves and others but also the presence and properties of objects within a given space[

20]. From the perspective of its intrinsic meaning, space is not merely a geometric domain but a multidimensional entity. The

Oxford English Dictionary defines space as the form of existence for material movement, consisting of length, width, and height, emphasizing its exploratory and infinite nature, and typically referring to a specific area or location[

21]. Laozi, in the

Tao Te Ching, states, "By hollowing out doors and windows, a room is formed; it is the emptiness that makes it useful," illustrating that the significance of space lies not only in defining what is present but also in the creative potential of what is absent[

22]. This perspective also offers valuable insights for interior space design, suggesting that the value of functional spaces lies not only in their physical composition but also in their ability to fulfill human activities and psychological needs.

The elements that constitute space include points, lines, planes, volumes, light, shadow, and materials. These elements work synergistically, collectively shaping the holistic multi-sensory experience of the space[

23]. Point is the most fundamental element of space, and through its varying size and density, it imparts a sense of dynamism to the space. Points with varying densities and arrangements can create visual focal points, evoke emotional responses, and infuse the space with vitality. In

Point and Line to Plane, Kandinsky highlights the dynamic and emotional qualities of lines, demonstrating how their arrangement and combinations in space can evoke varying visual effects[

24]. Planes and volumes define and occupy space, providing a multi-dimensional framework for interior design. Light and shadow play a crucial role in this, as the interaction between space and light shapes the overall experience[

25]. The interplay of natural and artificial light stimulates the visual elements within space, and the variation in light and its expression further influences emotional responses, thereby enhancing the space's mood and ambiance[

26]. At the same time, material, as one of the most immediate perceptual elements in space, profoundly influences the user’s experience through both tactile and visual interactions.

Perception, as a comprehensive activity involving both psychological and physiological processes, is at the core of spatial experience. It involves the cognition of an object’s spatial properties, such as size, shape, stability, and motion, as well as the distance and orientation between the object and the observer[

20]. We do not directly perceive space itself, but rather the spatial dimensions of the objects and individuals within it[

20]. George Berkeley proposed the concept of "Esse est percipi" (to be is to be perceived), emphasizing that perception is not merely the cognition of the objective world, but also a product of the interaction between the subjective self and the environment[

27]. Perception progresses from sensation to perception and ultimately to cognition. Sensation, as the starting point of perception, is the "fundamental process in the formation of complex experience[

28]." Sensation refers to an immediate, fundamental, and direct experience, which is the conscious perception of the characteristics or attributes of the natural environment[

29]. It is the initial reception of external information by humans through sensory modalities such as vision, hearing, and touch. Perception is the integration of these sensory inputs, which leads to a comprehensive understanding of objects[

29]. Merleau-Ponty argues that the body and perception are inseparable, with the body serving as the medium through which space is perceived[

8]. Perception is not only a physical cognition but also a subjective awareness of sensations, movement, and bodily position, representing a direct dialogue between the body and the environment[

8]. Sensation and perception are an integrated, inseparable process. Cognition is the advanced stage of perception, where information acquired through the senses is processed and transformed, ultimately leading to the formation of knowledge. Herbert A. Simon, often referred to as the "father of cognitive psychology," argues that this process is a synthesis of elements such as sensation, association, thought, memory, and language[

30], which elevates spatial experience into an understanding of culture and emotion.

2.2. Perceptual Phenomenology and Spatial Perception

Phenomenology offers a unique perspective on perception, focusing on the genuine experience of space by humans. As a key branch of Western philosophy, phenomenology emphasizes "returning to the things themselves"[

31], exploring the essential connection between perception and space, and revealing the reciprocal relationship between humans and their environment. The consciousness generated by perception interacts with the surrounding physical space, where space not only influences our perception and psychological state, but our thoughts and consciousness also shape our understanding of space, reflecting a dialectical relationship[

32]. Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology of perception particularly focuses on the role of the body in the perceptual process, asserting that space is formed through the integration of bodily movement and sensory perception into a holistic experience[

8]. Sensory experiences and perceptual memory are intricately intertwined, with different sensory stimuli not only altering our perception of space but also shaping its emotional ambiance through unconscious emotional responses[

33]. Juhani Pallasmaa further emphasizes that the senses and space are inseparable, and perception is an integrative process involving the collaboration of multiple senses[

34]. Through the perception of elements such as spatial scale, materials, and light and shadow, individuals can evoke emotional resonance within the physical space.

Phenomenology provides an effective framework for understanding the body's response to space, where the body is not only a medium of perception but also the subject of perception itself[

35]. The integration of bodily movement and sensory perception transforms spatial experience into a comprehensive process, blending dynamic and static elements[

36]. Phenomenology emphasizes experiencing space through continuous interaction with various elements[

37]. Sensory stimuli shape the perception of ambiance within a space by directly triggering emotional responses. Merleau-Ponty's theory, further expanded in Shusterman, R.'s research, posits that human perception results from the interaction between the body and objects, with tactile experiences shaping emotional cognition of space through bodily memory[

38]. Various sensory stimuli play a crucial role in spatial experience, profoundly influencing individuals' emotional and affective responses by modulating the perceptual process[

39].

Thus, within the framework of perceptual phenomenology, spatial experience is not merely a response of the body to external stimuli, but the outcome of the complex interaction between the individual and the space. Through the synergistic effect of multiple senses, the emotional ambiance and cultural significance of space are elevated, becoming a profound medium that reflects both individual and collective identity. Sensory experiences and perceptual memory are intricately intertwined, with different sensory stimuli not only altering our perception of space but also shaping its emotional ambiance through unconscious emotional responses[

40]. In this process, space exists not only as a physical entity but also as a vessel for emotion and culture.

2.3. Fundamental Characteristics of Spatial Perception

Spatial perception, as a product of human interaction with the environment, exhibits the following characteristics:

First, spatial perception has relative scale, emphasizing the relational dynamics between the human scale and the scale of the space. The human scale, closely related to ergonomics theory, optimizes the interaction between users and space, enhancing both human well-being and overall system performance[

41]. In the development of human society, "the human" is typically used as the reference scale for all things[

42]. Le Corbusier’s Modulor theory, using the 6-foot human figure as a reference, proposed a harmonious model of proportion between architecture and the human body, providing a universal framework for architecture and space[

43]. In practical design, variations in scale have a particularly significant impact on the spatial ambiance. For example, the Taicang Art Museum draws upon the spatial scale of traditional gardens to reconfigure the sense of depth in modern space. A narrow entrance before entering a large space creates emotional fluctuations through the difference in scale, which not only enhances the narrative quality of the space but also offers the viewer a richer psychological experience (

Figure 1).

A core characteristic of spatial perception is its ambiance, which is also a key element of the perceptual experience. Peter Zumthor argues that spatial ambiance is composed of various elements such as light, shadow, material, and color, forming a holistic perceptual experience[

44]. This sense of ambiance is not the result of a single element acting alone, but rather the outcome of the interaction between various elements. The perception of ambiance is not the result of a single element, but rather the interaction of various factors, relying not only on human subjective experience but also on non-human elements such as nature, objects, and physical components of the environment[

45]. For example, the Indian Brick Vault School Library uses the curved form of clay bricks, creating an organic integration with the surrounding natural environment. Sunlight filters through the windows, casting a subtle contrast with the interior material textures, creating a layered and tranquil spatial ambiance. Ambiance not only reflects the emotional qualities of a space but also directly influences the psychological state of the users.

Another key characteristic of spatial perception is its embodied nature, which reflects the interactive relationship between the body and the space. The body is not merely a passive receiver of sensory stimuli, but an active agent engaging with the environment[

46]. Through actual activities in architectural and urban spaces, individuals are able to develop a comprehensive bodily understanding of physical space[

14]. Space not only defines the trajectories of human actions but also presents varying perceptual effects as behaviors shift. The Brion family cemetery, through variations in path and spatial form, conveys distinct perceptions of life and death[

47]; whereas the Cherry Hill House redefines spatial attributes by blurring functional boundaries, integrating human behavior into the design logic. By gaining a profound understanding of spatial behavior, designers can more effectively integrate user experience into their design process.

2.4. Factors of Spatial Perception

2.4.1. The Subject of Spatial Perception: Senses

The experience of space is primarily realized through sensory perception, with the senses acting as the medium through which spatial information is conveyed. Merleau-Ponty refers to the holistic sensory experience as the "great world," while specific sensations are termed the "little world[

48]." The subject of spatial perception lies in human senses, namely the five senses—vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste—which serve as the primary means through which humans receive and process spatial information, collectively forming a comprehensive perceptual system.

Visual perception is the process through which humans observe and interpret spatial information via the eyes. Research indicates that approximately 80% of external information is derived from visual input[

49]. Gibson (2014), in his

Ecological Theory of Vision, argues that the "visual world" is composed of the familiar and commonplace scenes encountered in our daily lives[

50]. In the "visual field," what we perceive as a square is indeed a square, and what appears as a horizontal plane is perceived as such; these are directly apprehended through visual perception[

51]. In spatial design, the creation of visual perception is closely linked to the variations in shape, material, color, and light-shadow dynamics within the space; together, these elements shape the overall spatial experience[

52]. For instance, through the contrast of color and light-dark dynamics, designers can enhance the spatial depth and emotional expressiveness of the environment.

Sound is omnipresent within space, exerting direct and profound effects on individuals' psychological responses. Compared to vision, auditory perception elicits faster responses and possesses an all-encompassing nature, capable of creating ambiguous intentions within a space. The immediacy and multidimensionality of sound have been extensively studied[

53,

54]. For instance, Marks (1975) categorizes sounds in space according to different frequency colors, such as red, yellow, blue, and green, with each space possessing its own distinct auditory properties[

55]. Variations in sound can shape diverse spatial experiences, capable of both focusing attention and creating a sense of detachment within the space. Therefore, auditory perception within space must consider the diversity of sound, combining natural sounds with artificial ones to create distinct spatial atmospheres and enhance the poetic quality of the space[

56].

Touch is the earliest developed sense in humans and serves as the primary medium for interacting with the external world[

57]. Juhani Pallasmaa, in

The Seven Senses of Architecture, refers to touch as the "mother of the senses," asserting that it is the origin of all other senses and an extension of sensory faculties such as the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth[

58]. Touch enables us to perceive both the internal and external worlds of the body simultaneously[

59]. Based on the agency of tactile perception, touch can be categorized into active and passive tactile perception[

60]. Based on the agency of tactile perception, touch can be categorized into active and passive tactile perception. Passive tactile perception refers to the sensory experiences of the body in space, such as the perception of temperature, material textures, gentle breezes, and sunlight. Le Corbusier's use of the texture and tactile qualities of concrete in the Unité d'Habitation serves as a classic embodiment of tactile perception in architectural design[

61].

Olfaction and gustation are often overlooked in interior design; however, they play a distinctive role in shaping spatial experience. Studies on olfaction and gustation have shown that they can significantly influence human emotions and memory[

62]. For example, the sweet scent of candies in a candy store can evoke memories of carefree childhood moments. Although less prominent than vision and hearing, olfaction and gustation can leave a lasting impression on memory within a space. For example, in

The Poetics of Space, Bachelard illustrates how the scent of a single raisin in a space can evoke an entirely different atmosphere within the realm of human imagination[

63]. At times, visual elements can also be translated into gustatory experiences. For instance, C. Spence, in

The Perfect Meal: The Multisensory Science of Food and Dining, discusses a study where researchers served the same flavored foods (such as desserts) on plates of different shapes. The findings revealed that participants were more likely to perceive desserts on round plates as sweeter, while those served on plates with sharp edges were described as having a more "pungent" or "bitter" taste[

64]. Therefore, designers should recognize the subtle role of olfaction and gustation in spatial experience and make use of these senses to add greater depth and emotional dimension to the space.

2.4.2. The Object of Spatial Perception: Spatial Elements

An object is something that is perceived and observed. The object of spatial perception encompasses all material elements that influence spatial experience and atmosphere[

65], or the spatial environment formed by these elements, including nature, materials, light, shadow, and color. These elements collectively form the core of shaping the spatial ambiance. Natural elements such as light, wind, and water, along with material elements like wood, concrete, and stone, are commonly regarded as key factors influencing spatial ambiance[

66].

The use of natural elements in interior design is crucial for shaping the atmosphere. Light, water, and wind, as the most common natural elements, profoundly influence the emotional ambiance of a space through their physical properties[

67]. Light, particularly natural light, serves as a crucial tool for expressing the emotional tone of a space. Numerous studies on lighting in interior spaces have shown that factors such as light intensity, direction, and color temperature directly influence spatial perception, thereby affecting the emotions and behaviors of space users[

68,

69,

70]. The interplay between light and space breathes life into material forms, enabling the emotional hues of the space to unfold[

71]. Natural light is typically variable, whereas artificial light can be precisely controlled, aiding in the creation of the ideal spatial atmosphere[

72]. Water, as a natural element, plays an indispensable role in shaping the spatial atmosphere through its dynamic and static changes. The mirror-like reflection, fluidity, and integration with the environment of water add depth and layers to the space. In Zen-inspired spaces, water conveys a tranquil and solemn atmosphere[

73], while in commercial spaces, it evokes feelings of elegance and prestige. In addition, although wind is difficult to perceive directly, the sounds or changes in airflow it brings can profoundly affect spatial perception. Particularly, the interaction between wind and architectural structures can create unique spatial acoustic effects, which are well exemplified in traditional Jiangnan gardens[

74]. The "Wind Sound Cave" in the Ge Garden of Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province, China, serves as a typical example, where the interaction between wind and spatial structure creates a unique acoustic landscape with a distinct atmosphere.

The role of materials in space is crucial, as variations in texture and tactile qualities influence both the tactile and visual experiences of the space. The selection of materials directly influences the emotional expression of a space, thereby affecting people's perception and experience of the environment. Zumthor, in

Thinking Architecture, notes that materials themselves do not inherently possess poetry; it is only through the creativity and vision of the designer that the essence of materials can be revealed[

75]. For example, in Zumthor's design of the Saint Benedict Chapel, the interplay between the columns and the roof, along with the use of materials and spatial forms, conveys the concept of eternity in religion[

76], creating a spatial ambiance with profound symbolic significance. Through the harmonious design of nature and materials, space can convey emotional and cultural meanings that transcend the material realm. Spanish furniture designer Patricia Urquiola incorporates various fabric materials, such as wool, linen, suede, and synthetic textiles, into her designs. Through unique weaving techniques or stitching methods, she enhances both the tactile and visual qualities of these materials. The use of such materials often amplifies the design’s appeal and comfort.

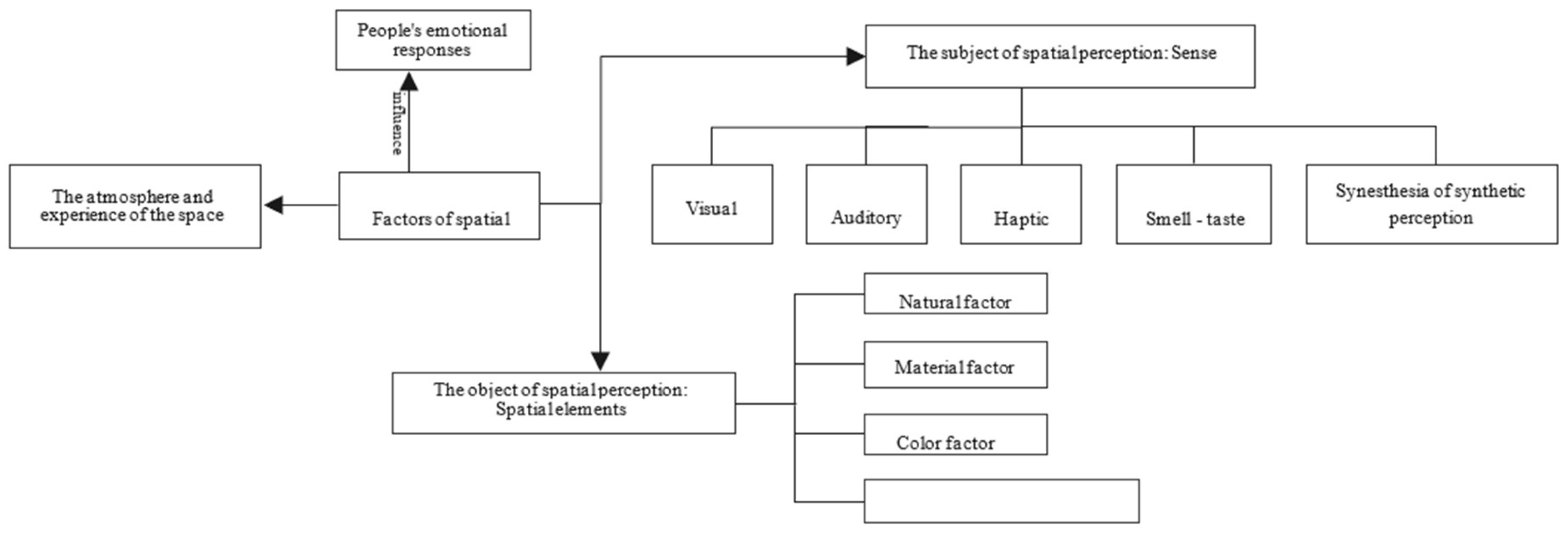

The following framework diagram illustrates the factors of spatial perception for the reader's ease of reference (

Table 1).

In summary, although research on spatial perception has garnered widespread attention in recent years, most studies focus on the phenomenological analysis of perception at the macro level, emphasizing the relationship between the body and space. Many studies remain at the level of abstract discussions of the senses, without delving into the specific impact of individual sensory elements on spatial experience and atmospheric perception. This limitation has resulted in a research gap concerning the methods, strategies, and practical applications of sensory integration in interior spaces, particularly in terms of how to effectively integrate different sensory elements in interior design, an issue that has not received adequate attention. More importantly, with the advancement of technology, the rise of virtual reality, augmented reality, and sensory interaction technologies has opened new opportunities for interior design. However, related research and practical applications remain insufficient. This study seeks to address this gap by proposing an interior design concept centered around spatial perception. It explores in-depth how the interaction between subjects and objects within a space can inform a series of multisensory design strategies and methods, which are then applied to the practical design of the Suzhou Coffee Factory renovation. In addition, this study explores the application of emerging technologies in multisensory design, aiming to provide users with an immersive, lifelike experience.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Construction of Visual Perception

Vision is one of the most fundamental senses in spatial experience, playing a decisive role in the initial perception and emotional response to space. Influenced by the theocratic connotations of the Renaissance, scholars have linked vision with fire and light[

77]. In

Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision by Levin, it is discussed that "humanity's domination by the visual paradigm dates back to ancient Greece, where all truth and reality begin with vision, centered around the visual[

78]." In interior spatial design, visual elements primarily include the combination of color, light, and spatial form, while also encompassing the careful construction of scale, layout, hierarchical structure, and their interrelationships. The thoughtful arrangement of visual elements has a profound impact on spatial perception, influencing not only the aesthetic presentation of the space but also playing a crucial role in shaping its emotional atmosphere and functional experience.

We can identify several different methods for creating visual space, while considering their role in spatial design:

Color as a means of conveying spatial emotion and scale differentiation;

Light and shadow as fundamental elements in creating spatial depth and a sense of mystery;

Enriching the spatial formal language to enhance the depth of visual perception.

3.1.1. Color as a Means of Conveying Spatial Emotion and Scale Differentiation

The role of color in space extends beyond decorative function; it serves as a core medium for emotional transmission[

71], influencing the creation of spatial ambiance and even affecting individual behavior and decision-making[

79]. Color is often associated with the concept of "temperature," referring to the warmth or coolness of colors—warm and cool hues, or spectral wavelengths. These light waves travel through the eyes to the brain, exerting significant effects on both our physiology and psychology. Thus, color, as a key element in spatial design, is particularly significant in its connection to emotion. In Wilson's (1966) study, participants were shown slides in an alternating sequence, each with an equal number of red and green slides[

80]. The findings revealed that red, a warm color, induced more excitement than green, a cool color[

80]. A similar effect can be observed in the use of color within spatial environments. Recent studies have shown, through data model analysis, that people's emotional responses to color are not only associated with hue or wavelength, but are primarily influenced by the color's saturation and brightness levels[

81,

82,

83]. For example, in leisure spaces such as cafés and libraries, light blue and beige are often used to create a relaxed and tranquil atmosphere. These two colors, characterized by high brightness and low saturation, make the space appear light and expansive, helping to alleviate stress and stimulate thinking.

Color plays a crucial role in shaping the emotional atmosphere of a space, and its unique visual illusion effects have a profound impact on the perception and experience of spatial scale. Research in perceptual psychology suggests that color is not merely a physical attribute of sensory stimuli; it can also induce visual illusions of an object's surface size[

84]. It is the varying properties of color, particularly changes in brightness and saturation, that influence individuals' perception of a space's physical scale at the sensory level. For example, people often choose to wear dark-colored clothing to appear taller, which is an effect produced by color-induced visual illusions. Light or cool colors, typically with higher light reflectance[

85], can create a sense of spatial expansion and openness visually (

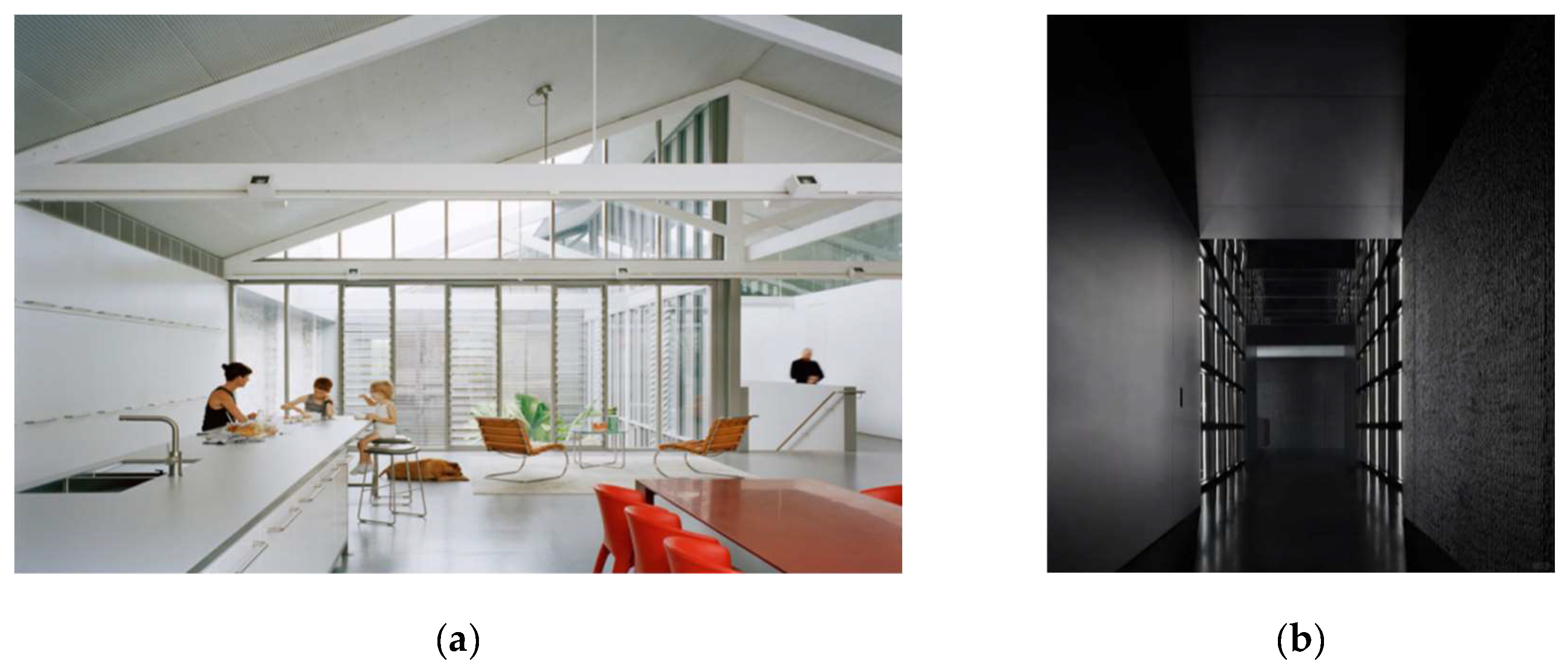

Figure 2, a). Darker and warmer tones, by increasing light absorption and reducing spatial brightness, create a sense of spatial compression and enclosure, making the space appear more cramped and narrow (

Figure 2, b)[

52]. The distribution and combination of different colors can alter the sense of scale, width, height, and proportion in a space, thus influencing the overall spatial experience.

Moreover, the choice and combination of colors are closely linked to the social and psychological characteristics of the users[

82]. In his study, Saito M used factor and cluster analysis to conclude that there is a general preference for the color white in Asia, a preference influenced by environmental and cultural factors[

86]. In addition, studies have shown that color preferences and emotional responses are also influenced by factors such as age, gender, and background[

87]. Children tend to prefer bold, vibrant colors such as pink, yellow, green, and blue[

87]; while young adults are more drawn to high-end hues with low brightness and low saturation, such as gray and muted tones like those found in the Morandi palette, which convey a sense of calm and sophistication. Middle-aged individuals often favor deep, grounded tones, like brown and dark green, which exude a sense of stability. Older adults are more inclined to choose colors with low brightness and low saturation, as these colors provide both visual and psychological comfort, promoting relaxation and enhancing overall well-being. In healthcare space design, color selection should prioritize warm, natural, and healing tones[

88], such as light yellow, beige, green, and blue, which can effectively alleviate patients' anxiety and stress. Therefore, the rational configuration of interior colors should not only align with the functional requirements of the space but also be precisely designed based on the physical and psychological characteristics of the user group, ensuring that the emotional communication of color meets the needs of different groups.

3.1.2. Light and Shadow as Fundamental Elements in Creating Spatial Depth and a Sense of Mystery

Light is fundamental to visual experience, as all visual information and image presentation depend on its presence for perception to occur[

89]. Light, from subtle to intense, regulates the observer's emotions and profoundly impacts the quality of architectural experience as well as human well-being[

26]. The use of light in space is typically divided into two main categories: natural light and artificial light.

Natural light, as a source derived from the sun, is not only the most basic and natural form of illumination but also plays a crucial role in spatial design. Louis Kahn once said, "The building only truly appears when sunlight strikes the wall, and it is only when the sun hits one side of the building that you realize how magnificent it is[

90]." This statement profoundly expresses the importance of natural light in space; it not only brings a sense of life to the architecture but also influences the ambiance and emotional experience of the space.

We have identified the following three functions of natural light in space:

Natural light as a key element in enhancing visual focal points within a space;

Natural light as an element that enriches spatial depth and visual experience;

Natural light as a means of creating spatial ambiance.

Below, I will present five case studies to illustrate the three methods outlined above (

Table 2). These include the Pantheon, the Church of the Suffering Virgin, the Li shui Office Headquarters in Zhejiang, the Church of Light, and the Central Presbyterian Church in Canada. These architectural works all exemplify the role of natural light in shaping spatial experiences.

Natural light is not only a crucial lighting element in space, but also influences the formation of spatial depth, ambiance, and visual focal points through its unique qualities. From ancient Roman architecture to modern interior design, natural light, as a core element of spatial design, brings rich emotional expression and visual effects to a space through its flow, refraction, and reflection. Therefore, the thoughtful integration of natural light in space not only enhances the visual quality of the space but also effectively shapes its emotional atmosphere, imbuing both architecture and interior spaces with greater vitality and expressiveness.

With the ongoing advancement of technology and the instability of natural light, the use of artificial lighting has become increasingly widespread in modern spatial design, commonly referred to as lighting design. Artificial lighting not only effectively supplements natural light but also imbues the space with a unique ambiance and visual experience[

26]. Lighting design—encompassing factors such as light intensity, light source positioning, color temperature, and lighting techniques—plays a crucial role in shaping the spatial ambiance[

91]. Based on varying light intensities, artificial lighting can be classified into two main categories: high-intensity lighting and low-intensity lighting. High-intensity lighting quickly captures attention and is commonly used in spaces such as theaters and exhibition areas where focus needs to be directed. For example, in

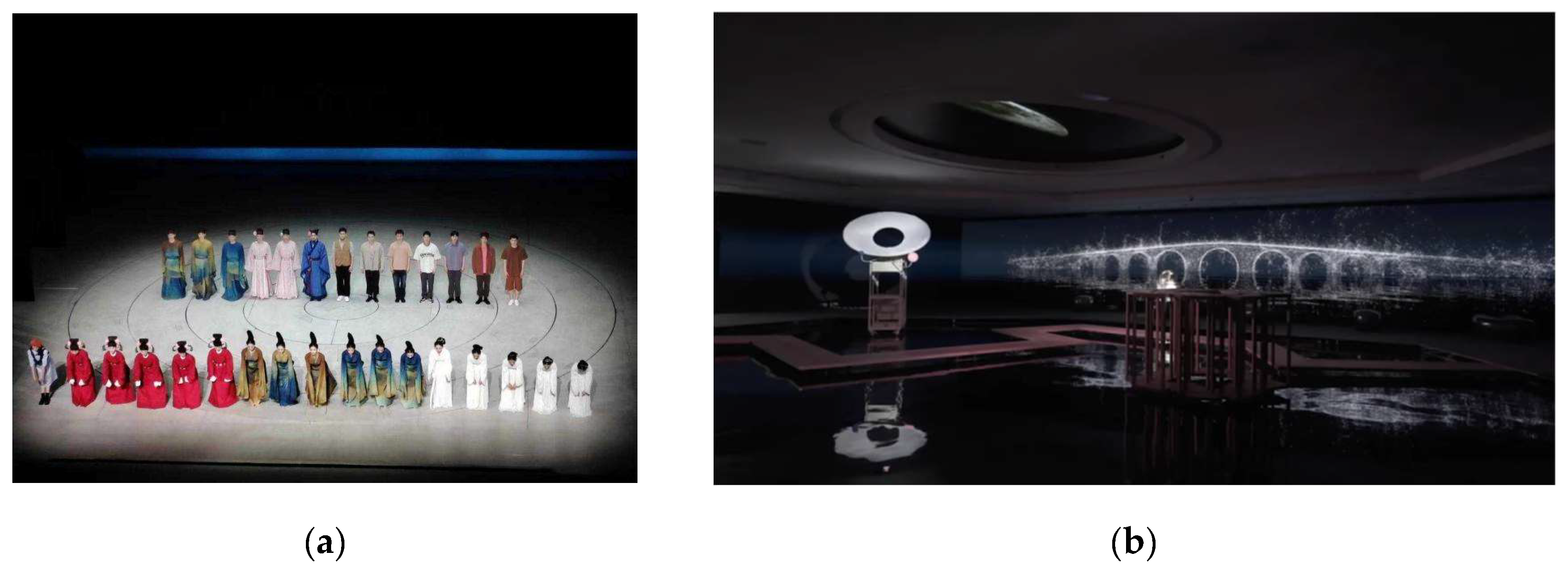

a still from Only Green, the intense spotlight in the center creates a stark contrast with the surrounding darkness, effectively directing the audience's attention to the performance (

Figure 3, a). Low-intensity lighting, on the other hand, offers a softer feel and is ideal for spaces such as homes and art galleries, where a warm and tranquil atmosphere is desired. The color temperature of light influences the emotional experience of a space[

92]. Cool light (low color temperature) often evokes a sense of calm and coolness, while warm light (high color temperature) creates feelings of warmth and relaxation. With the increasing demand for immersive spatial experiences, recent lighting design has integrated technology, giving rise to a series of interactive light and shadow immersive environments. These innovative spatial experiences go beyond static art displays, actively engaging the audience in the creative process of light and shadow interaction. For example, the "Suzhou Life and Color Museum" at the Suzhou Museum triggers various light and shadow effects through voice interaction, showcasing the beautiful landscapes of Suzhou and offering visitors an immersive experience (

Figure 3, b).

3.1.3. Enriching the Spatial Formal Language to Enhance the Depth of Visual Perception

The use of spatial formal language includes the treatment of individual spatial forms as well as the composition of multiple spatial forms. In real life, buildings composed of a single space are rare; most architectural spaces are typically made up of multiple interconnected spaces[

23]. Therefore, I will explore how the expression of spatial form in multi-space configurations can alter people's emotional experiences through its impact on visual perception. The design of contrast and variation, penetration and layering, as well as sequence and rhythm, all influence the emotional atmosphere of a space through the intentional use of spatial formal language.

Spatial contrast and variation refer to the perceptible differences between adjacent spaces, which are typically reflected in variations in height, openness and enclosure, changes in spatial form, and spatial orientation. When an individual moves from one space to another, and the two spaces exhibit distinct differences—whether in size, volume, or openness—it evokes corresponding emotional changes. For instance, in the Hagia Sophia, a low, narrow vestibule precedes the lofty and spacious hall. The strong spatial contrast between the vestibule and the hall triggers a profound emotional shift as one moves through the threshold. This phenomenon is a direct reflection of how spatial contrast and variation influence emotional and psychological states.

Spatial permeability and depth refer to the intentional connection of different spaces without fully relying on physical walls for separation, thereby enhancing the sense of spatial layering. In his definition of interior rooms, Wright utilized multiple boundaries and blurred spatial layers, enabling the overlap and interpenetration of different spaces[

93]. Through this design strategy, the flow between spaces is encouraged, enhancing the perception of continuity and visual complexity. In works by Toyo Ito, such as the Shibaura office, the introduction of mezzanine spaces and variations in volume not only maximize the visual impact of the design but also imbue the space with dynamism and a sense of depth. Spatial permeability breaks down strict spatial boundaries, altering the perception of boundaries and scale, and allowing participants to discover and experience different layers within a continuously flowing space.

Spatial sequence and rhythm—the organization of spatial sequences plays a crucial role in guiding the flow of people. The design of spatial sequences typically depends on the arrangement of pedestrian circulation paths and should incorporate a sense of rhythm, including the alternation of highs and lows, emphasis and restraint, and moments of calm and climax. In a complete spatial sequence, the climax serves as the emotional high point of the spatial experience. By utilizing spatial contrast or the relationship between spatial contraction and expansion, the climax space can be emphasized. For example, in a carefully designed spatial sequence, a compressed or enclosed space is often followed by an open or expansive one. These variations in space ultimately lead to the "climax" of the spatial experience. This spatial organization is akin to a narrative structure, where the compression and expansion of space create emotional fluctuations through contrast.

3.2. Designing Auditory Perception (Carefully Crafted Soundscapes to Enhance Immersion)

We have outlined four methods of using sound in spatial design:

Soundscape design;

Temporal control of sound;

Contextual guidance through sound;

Immersive sound interaction experience.

3.2.1. Soundscape Design

Human conscious shaping of the surrounding environment must include the sonic environment, as the sonic environment shapes the individual[

94]. The construction of auditory perception within space is often achieved through the design of ambient sounds in the environment[

95]. Many studies have shown that sound can suggest the identity and function of a space[

96,

97]. Different sonic atmospheres not only shape the emotional ambiance of a space but also evoke emotional shifts in users, triggering relatively strong emotional reactions[

98], thereby deepening their perception and experience of the space. For example, in amusement parks, cheerful music conveys a sense of relaxation and joy; in bars, energetic music stimulates vitality and a lively atmosphere; while in commemorative museums, solemn background music enhances the dignified and reverent ambiance of the space. These soundscapes provide users with an emotional connection to the space, thereby influencing their spatial perception. The design of soundscapes can be divided into the creation of natural sounds and artificial sounds[

99], with each playing a unique role within the space.

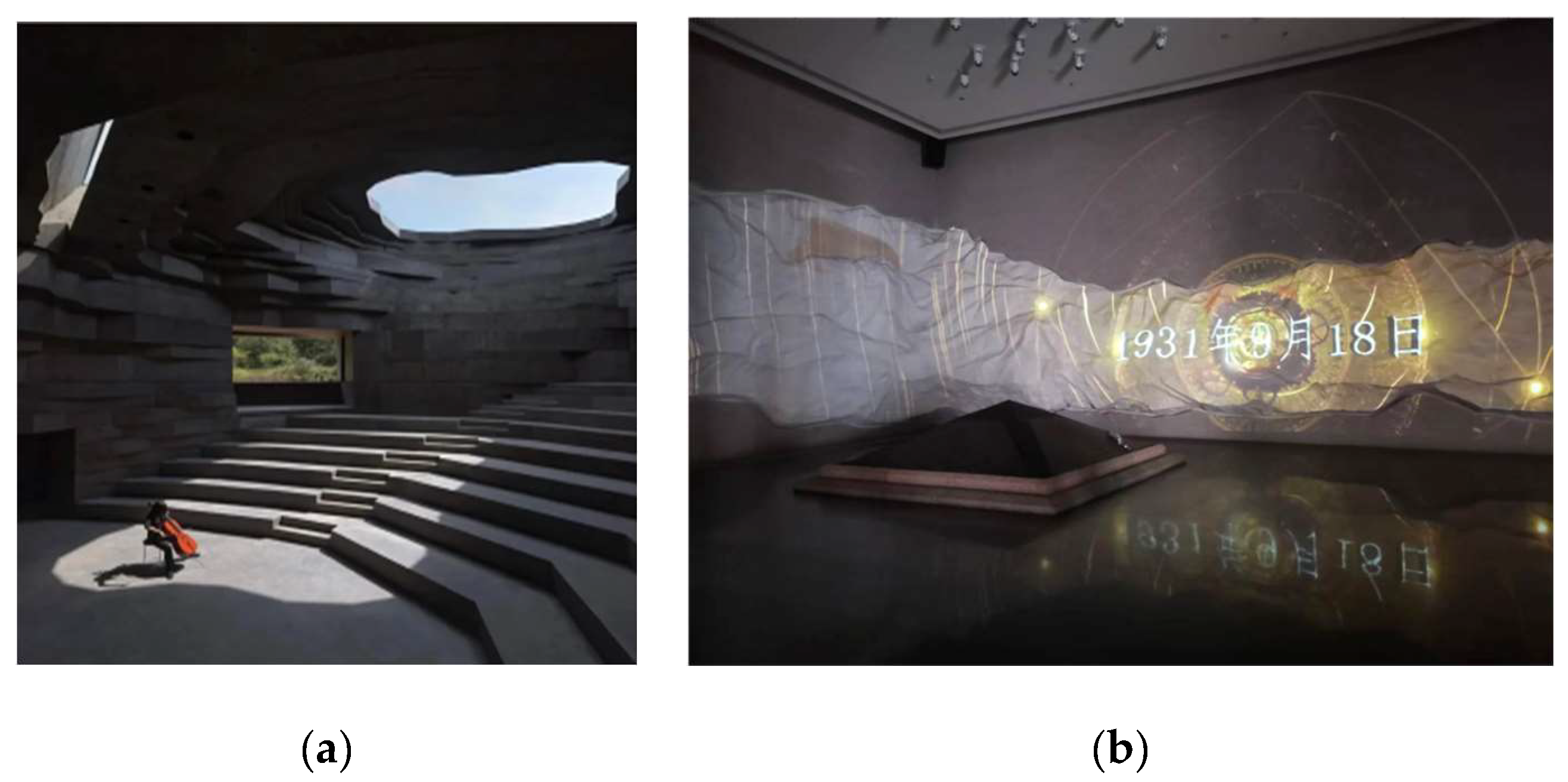

Creation of natural sounds: Natural sounds, through the interaction of acoustic phenomena or environmental sounds with the space, collaboratively create a unique sensory experience. For example, the Music Chapel near Chengde, Beijing, serves as a typical case. The building is situated in a valley, constructed entirely of concrete, with an interior space capable of hosting concerts. The rock-like form integrates seamlessly with the surrounding natural environment, creating exceptional acoustics. The sound of flowing water circulates within the space, adding a natural ambiance to the environment (

Figure 4, a). In addition, the Echo Wall at the Temple of Heaven in Beijing uses the principle of sound wave reflection to create an interaction between the space and the individual, allowing users to experience a unique auditory effect. Creation of artificial sounds: Artificial sounds, generated through sound equipment or digital technology, create specific spatial atmospheres and are particularly common in museums or exhibition spaces. For example, the vestibule of the September 18th Historical Museum plays intense sounds of war through its sound system, combined with surrounding digital projections, creating an immersive experience for the viewer (

Figure 4, b).

3.2.2. Temporal Control of Sound

Temporal control of sound plays a crucial role in spatial design, particularly in guiding the spatial ambiance and influencing users' emotional responses. The duration of sound, the timing of its onset and termination, and even its interruption, can have a profound impact on the perception of space[

100]. Designers should carefully plan the timing of sound based on the spatial layout, functional requirements, and the emotional context of the space. For example, in exhibition spaces, designers can select appropriate background music, aligning it with the content of the exhibits and the atmosphere of the display. By controlling pitch, rhythm, and volume, they can create a specific emotional ambiance. The rhythm of music can be coordinated with the undulations and layering of the space, harmonizing the sound with the spatial design. This creates a guided "sound flow" within the space. Through precise control of sound timing, the audience can subtly perceive the sequence of the visit and the climax of the space.

3.2.3. Contextual Guidance through Sound

Sound is not merely an accessory element of space; it also plays a powerful role in guiding the context. Different sounds can evoke visual associations and emotional responses in individuals[

98]. For example, when hearing the sound of burning, people naturally associate it with the image of flames, and their emotions become heightened; similarly, the sound of falling snowflakes often evokes images of winter, inducing a feeling of coldness. The contextual guiding effect of sound enhances the emotional experience of the space, complementing its visual effects.

Designers can guide users' emotions through the integration of sound and spatial context. In recent years, numerous sound installation artworks have emerged, incorporating sound-triggering mechanisms within specific spaces. When the audience enters a designated area, sound is immediately activated, thereby enhancing participation and immersion. For example, Zimoun exhibited Mechanical Sound Sculpture at the NYU Art Gallery, Abu Dhabi, in 2019. The piece consists of suspended black rods connected to motors, generating periodic vibrations that trigger collisions or friction between objects, thus creating a unique soundscape. The artwork blurs the boundary between the audience and the piece itself, enhancing both immersion and interactivity.

3.2.4. Immersive Sound Interaction Experience

With the advancement of digital technology, immersive sound interaction experiences have become an innovative trend in contemporary spatial design, such as video-audio games within spaces[

101]. By combining sound with digital media technology, the audience can experience an immersive interactive effect, as if placed in a virtual world of sound and light. Immersive sound interaction not only makes the spatial experience more multisensory but also enhances the audience's sense of participation and interactivity[

102]. Immersive sound interaction can be categorized into two types: interaction between the individual and the space, and interaction between the individual and the installation. In this context, sound interaction can be initiated by the space or installation, or it can involve the audience responding with sound, which in turn triggers feedback from the space or installation. For example, Lin Junting's interactive video-sound installation

Echo is a typical application of this concept. This work uses digital media technology, combining a large-scale landscape painting with a sound installation. When the audience speaks into the microphone, it triggers interactive effects such as rain, ripples, and flying birds, accompanied by pleasant singing, creating an immersive experience (

Figure 5).

3.3. The Application of Tactile Perception

The application of tactile perception in spatial design is becoming increasingly important, serving as a crucial dimension in creating rich spatial experiences. In his book

The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses, J. Pallasmaa notes that humans perceive the texture, patterns, temperature, and form of objects through the skin[

34], thereby sensing the atmosphere and emotions of a space. In

Touch: The Feeling of Emotion and Technology, M. Paterson explores two aspects of tactile perception: the "direct" and the "metaphorical." Tactile perception is not limited to immediate physical touch; it also carries a metaphorical emotional meaning, capable of evoking psychological and emotional responses through indirect tactile design[

103].

We have outlined four methods of using sound in spatial design:

3.3.1 Creation of Direct Tactile Perception

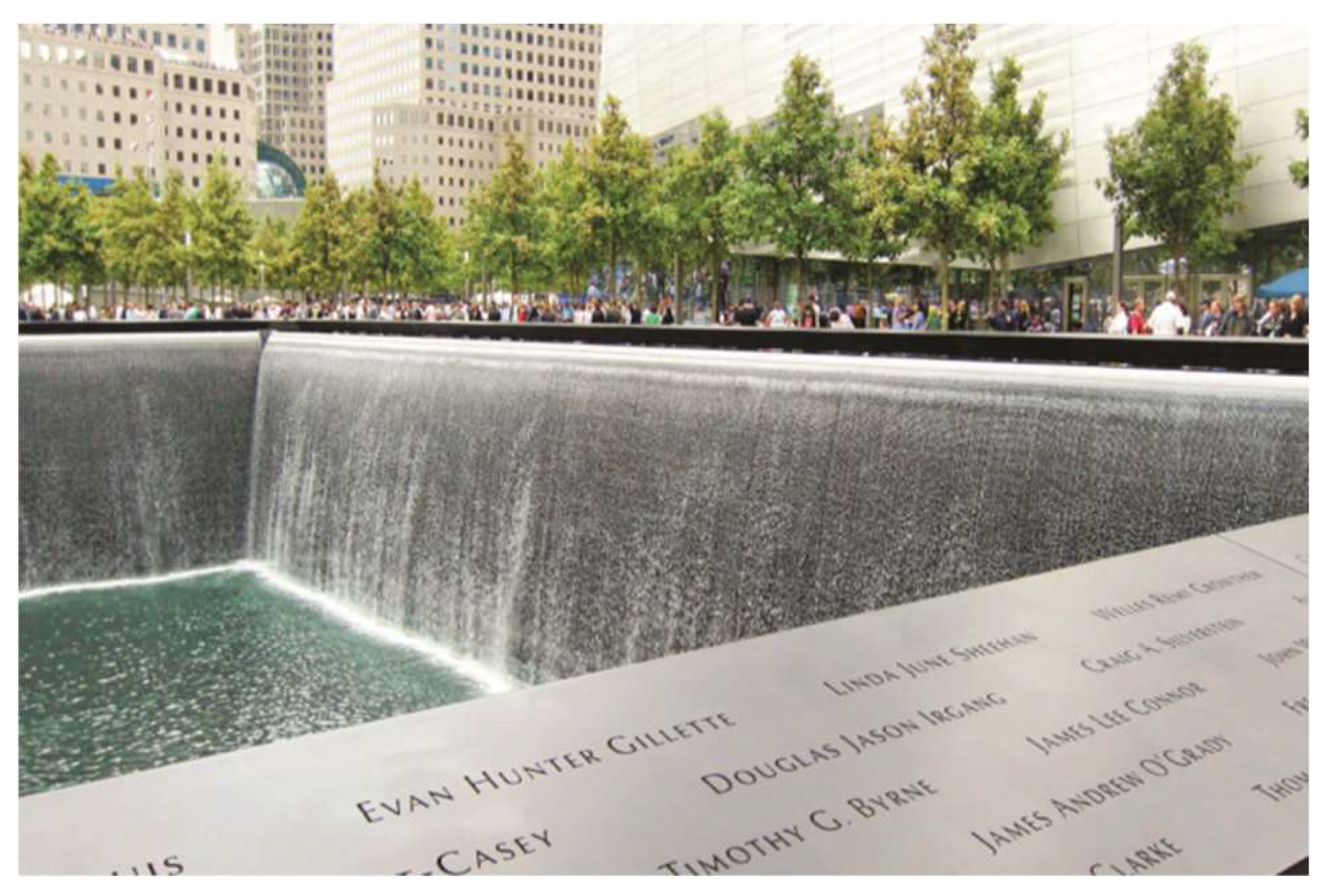

Direct tactile perception occurs through the skin's contact or the body's interaction with spatial elements, offering the most primal form of spatial awareness. It is a highly intuitive and immediate mode of perception, typically transmitting signals through tactile receptors in the skin, resulting in a direct response to objects. For example, on either side of the memorial pool at the National September 11 Memorial & Museum, the names of the 2,983 victims are engraved. Visitors can express their condolences by touching these names, thereby feeling the sorrow of the tragedy. This design demonstrates the emotional qualities of materials, evoking deep emotional resonance through touch (

Figure 6). In interior design, the selection of materials and surface textures are the core means of direct tactile perception. Natural materials such as wood and stone evoke a sense of rustic warmth, while artificial materials like metal and glass convey a modern aesthetic. Different materials and textures influence the spatial ambiance through tactile sensations, enriching and adding layers to the environment. Material expression: Natural materials such as wood, stone, and clay convey emotions of warmth and dignity, while artificial materials like metal and glass evoke a more modern sensibility. Designers should select appropriate materials based on the spatial requirements to convey a specific atmosphere. Material texture expression: Modern techniques, such as biomimetic additive manufacturing, have made material textures more diverse[

104]. Examples include concrete wall panels with bamboo-patterned arrangements, cement components with wood textures, and concrete panels with rammed earth-like textures (

Figure 7). Through innovative techniques, designers can provide traditional materials with new tactile experiences, enriching spatial perception.

3.3.2 Creation of Indirect Tactile Perception

Indirect tactile perception involves perceiving the properties of objects through other mediums or tools, influencing individuals' psychological responses. When viewers or occupants see a particular material in a space, even if they do not physically touch it, they may mentally imagine or simulate the sensation of reaching out to touch it. Peter Zumthor's Therme Vals is a classic example, where local stone is used in the design, and the variation in materials on the walls and floors conveys warmth and comfort (

Figure 8). Although visitors may not directly interact with all materials, the spatial layout and lighting allow them to perceive the temperature variations of different materials (such as the coldness of stone and the warmth of the thermal waters), enhancing the emotional experience and sense of memory within the space. This tactile perception in space is more rooted in the visual understanding of materials and the perception of light and shadow changes.

3.4. Integration of Olfactory and Gustatory Perception (Experiencing Space through Scent)

Olfaction and gustation play a crucial role in the experience of spatial ambiance. Both share a common perceptual mechanism, triggering the brain's perception and memory storage through scent. Many studies indicate that scent, beyond being a physical olfactory phenomenon, carries emotional and social significance, evoking emotional associations with specific people, places, or memories[

105], and can even trigger intense emotional responses unconsciously[

58]. Thus, the design of spatial scent is not only about aesthetics but also enhances the immersive experience by engaging people's senses and emotions. The following will focus on how the selection and design of scent can create emotionally rich and memorable spaces.

We have outlined two methods of using scent in spatial design:

3.4.1. The Selection of Scent and Emotional Creation

The choice of scent directly shapes the atmosphere of the space. Studies have shown that pleasant environmental scents can effectively enhance our mood and improve overall well-being[

106,

107]. For example, fresh and subtle scents often evoke feelings of comfort and pleasure, enhancing the overall comfort of the space. In office environments or commercial spaces, delicate fragrances help alleviate stress and enhance the experience of work or shopping. In stores of renowned brands, designers use strategic scent installations to create unique brand fragrances, allowing customers to form brand associations through their interaction with the space, thereby enhancing consumer experience and brand identity[

108]. The selection of scent in dining spaces is particularly important.

For example, an Italian restaurant might choose scents of freshly baked bread, herbs, and olive oil to create a Mediterranean atmosphere, complementing its menu and decor style. Scent design should align with the function and purpose of the space, ensuring that it works in harmony with other elements of the space, such as visual and auditory features, to achieve the optimal spatial experience. Scent not only influences the ambiance of a space but also regulates emotions and triggers deep emotional responses. For example, in the Klaus Brothers Chapel designed by Zumthor, the scent of pinewood, burned to release its fragrance, creates a tranquil and peaceful atmosphere, helping visitors meditate and feel as though they are conversing with the divine. In the "Moonlit Breeze Pavilion" at the Wangshi Garden in Suzhou, the blooming lotus flowers in spring emit a calming fragrance that enhances visitors' physical and mental well-being (

Figure 9a, b).

At the same time, scent design should also take into account the health and comfort of the users. Aromatic candles have become increasingly popular worldwide in recent years[

109], becoming an essential part of many people's daily lives. Studies have shown that common aromatherapy scents, such as lavender, significantly positively impact the human body, typically reducing stress, improving sleep quality, and even accelerating recovery from illness[

110]. However, some individuals may have allergic or adverse reactions to certain scents. Therefore, when selecting fragrances, it is important to avoid those that are overly stimulate or likely to trigger allergic reactions.

With the rapid development of digital technology, digital taste and olfactory technologies have been increasingly applied in augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) devices. Erika Kerruish's research explores two digital devices, Vocktail and Season Traveller, which integrate taste and olfaction, revealing how digital technology expands sensory experiences and reshapes traditional perceptual habits[

111]. The former enhances the sensory experience of drinking water and air by electrically stimulating taste buds and manipulating color and scent; the latter enhances the immersion in VR games through sensory elements such as wind, scent, and temperature[

111]. The study reexamines multisensory technologies from cultural and perceptual perspectives, proposing a reconstruction of sensory stimuli in the digital world.

3.4.2. Creating Memorable Scent Spaces

Scent is closely related to memory. The Proustian effect suggests that scent can evoke specific memories, instantly transporting individuals back to past moments[

112]. For example, a specific home fragrance may evoke a sense of familiarity and comfort when encountered in a similar scent elsewhere. Similarly, in situations of anxiety or joy, certain scents, when encountered again years later, can still trigger corresponding emotional responses.

Gustation is also closely related to olfaction. When we taste a particular food, its flavor often evokes memories of specific moments or situations. Therefore, designers can create emotionally rich and memorable spatial environments by selecting distinctive scents, fragrances that align with the functional requirements of the space, and appropriate scent experience installations. Such design helps individuals establish emotional connections within the space, leaving a lasting spatial memory.

4. Result: Practice Experience

4.1. Project Background

Suzhou Industrial Park is a significant collaborative project between the governments of China and Singapore[

113]. The Suzhou Coffee Roasting Factory, located in the Suzhou Industrial Park, is an integrated space that combines coffee roasting, exhibition, and consumer experience. The site is located at Building A, No. 61 Jiepu Road, Shengpu Sub-district, Suzhou Industrial Park. Within a 2-kilometer radius, there are numerous factories, including food processing plants, technology innovation parks, and equipment manufacturing enterprises, among other light industrial facilities (

Figure 10). The factory not only handles coffee production and supply but also aims to attract customers to engage in the coffee-making and tasting process by offering an immersive experience.

4.2. Theme and Design Strategy

The design concept of this project aims to enhance the sensory experience of customers through spatial perception, thereby strengthening their emotional connection with the brand and enriching the overall user experience (

Figure 11). The design direction of the project not only focuses on functionality, such as the layout of the coffee roasting production area, but also places a high emphasis on the customer experience. By integrating spatial perception theory, we utilize multisensory elements such as vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste to enhance the overall sensory experience of customers in the factory, while reinforcing the brand's uniqueness.

4.3. Spatial Structure and Circulation Organization

In the initial stages of the design, we referred to and analyzed the interior design characteristics of Adolf Loos' Müller House. The building's exterior is simple and unadorned, while the interior is divided through staggered levels and variations in ceiling height, breaking traditional floor relationships and enhancing interaction between spaces[

114]. This design concept inspired us to apply it to the spatial structure and organization of the coffee roasting factory, aiming to break the monotony and boundary perception typical of traditional factory spaces. It seeks to enhance spatial depth and dimensionality, creating a multi-layered and interactive coffee roasting factory experience.

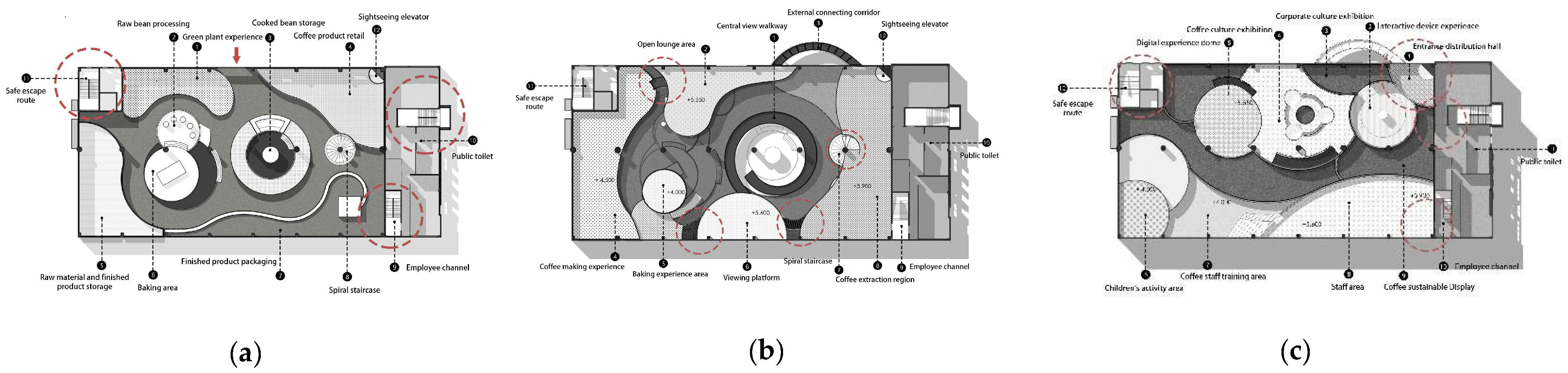

The coffee roasting factory is divided into three levels (

Figure 12a, b, c). The first level is primarily a visitor-accessible machine processing area, with functional zones including a plant experience area, green coffee bean processing area, roasting area, roasted bean storage area, finished product packaging area, raw and finished product storage area, and a coffee product retail section. The mezzanine area is primarily designed as an interactive experience zone for customers, with functional areas including a central scenic walkway, open lounge, connecting corridor, coffee-making experience zone, roasting experience area, viewing platform, and coffee extraction zone. The second level primarily consists of the coffee museum exhibition area and employee office spaces. Functional zones include an interactive installation experience area, corporate culture display area, coffee culture exhibition area, digital experience dome, children's activity zone, coffee employee training area, staff offices, and a coffee sustainability exhibition zone.

4.4. Application of Spatial Perception Design Strategies

In the following section, we will provide a detailed discussion of four key areas: the factory entrance, mezzanine coffee-making experience zone, second-floor interactive installation experience zone, and second-floor coffee culture exhibition area, to validate the spatial perception design strategies outlined in the "Materials and Methods" section.

4.4.1. Factory Entrance Area

The design of the factory entrance area offers an immersive spatial experience for customers through a multisensory engagement of vision, hearing, touch, and smell. In terms of visuals, we place special emphasis on color coordination and lighting design to create a space that is both warm and modern. The primary color scheme of the space features warm wood tones and neutral beige, creating a sense of warmth and comfort for customers. This color combination also complements the natural hues of coffee, enhancing the overall coherence of the space. The curved, rotating ramp at the entrance creates a striking visual contrast with the 5-meter-high roasted bean storage at the center, breaking the monotony of the surrounding minimalist space. In addition, the green plant experience area on the right creates a striking color contrast with the surrounding white and gray tones, with the greenery becoming the second visual focal point of the space. Through its growth form and color, the plants guide the customers' gaze (

Figure 13a, b), illustrating how color serves as a means of conveying spatial emotion and scale differentiation. In terms of sound, the light and pleasant music played at the entrance ushers customers into a relaxed and comfortable environment, reflecting the design of the soundscape. In terms of touch, a touchscreen display is positioned directly in front of the entrance in the roasted bean area, allowing customers to interact and explore the spatial layout of the entire factory. In addition, the digital screens in the plant experience area offer interactive experiences, further enhancing the sense of immersion in the space. In terms of scent, the roasting aroma within the coffee factory blends with the fresh air of the plant area, creating an atmosphere that feels as though one is entering the natural world of coffee.

4.4.2. Mezzanine Coffee-Making Experience Zone

The mezzanine coffee-making experience zone is an area where customers actively participate. The design focuses on spatial dynamism and the stimulation of multiple senses. Visually, the coffee bean experience installation in this area consists of a series of curved structures suspended from the ceiling, visually complementing the surrounding curved space and guiding the visitors' path. The curves and variations in height of the installation make the space more dynamic. The lighting at the central installation changes with the movement of customers, creating alternating light and dark, which enhances the dynamism of the space. The lighting on both sides uses soft warm lighting to create a relaxed and comfortable tasting atmosphere (

Figure 14).

In terms of auditory, olfactory, and gustatory experiences, customers can use their sense of smell to experience the aromas of different coffee beans from the 14 hanging installations, allowing them to savor the unique flavors of each variety. Customers can also participate in selecting coffee beans, with the sound of the beans dropping, "tick-tick," accompanying the process. This auditory effect creates a rhythmic sensation similar to music, enhancing the spatial auditory experience and exemplifying the contextual guidance of sound. The design of this area encourages customers to engage in the coffee-making and tasting process. An open coffee-making station allows customers to closely observe the coffee preparation process while experiencing the aromas and warmth generated during the making of coffee. This design not only enhances the gustatory experience but also deepens customers' understanding and appreciation of the allure of coffee. This area provides a multisensory interactive experience by integrating visual, olfactory, and auditory elements.

4.4.3. Second-Floor Interactive Installation Experience Zone

The second floor is more enclosed compared to the first, and this area primarily showcases the use of digital technology and modern science to create an immersive sound and light interactive experience space, integrating visual, auditory, and tactile senses. A museum-style display approach is employed, with a focus on interactivity and a sense of temporal immersion. The tree-shaped interactive installation at the second-floor entrance uses flowing lighting to evoke a sense of time passing. When standing, a halo forms beneath the feet, creating a mesmerizing visual effect (

Figure 15). This design highlights the significant role of artificial lighting in shaping the spatial ambiance. The surrounding lights filter through the gaps, creating regular light spots that guide the visitors along their path.

Meanwhile, the electronic screen on the left displays the entire process of coffee production, from harvesting to preparation. Customers can interact with the touch console to explore different coffee-making processes. This design not only enhances customers' understanding of coffee culture but also enriches their visit experience through tactile interaction, strengthening the fusion of visual and auditory elements.

4.4.4. Second-Floor Coffee Culture Exhibition Area

The design of the second-floor coffee culture exhibition area creates a healing atmosphere by blending natural elements with coffee culture. At the center of the area, a light well houses coffee plants and other indoor greenery, with natural light filtering through the circular skylight above, creating a connection to nature and filling the space with vitality. This design utilizes natural light as a structural element, enhancing the visual comfort of the space. The walls are made of rough natural stone, allowing customers to touch the stone surface and feel the power of nature. The display cabinets are cleverly embedded within the stone wall, drawing customers' attention under the accentuation of lighting. Through the integration of tactile and visual elements, this area creates a space that merges coffee culture with nature, enabling customers to experience the healing effect of coffee in an immersive environment (

Figure 16).

Additionally, the mezzanine area features an AI experience installation where customers can input keywords to generate their ideal coffee experience space, followed by a 360° panoramic experience with VR devices (

Figure 17). This design integrates the comprehensive use of sensory synesthesia, allowing customers to experience the space through both visual and tactile senses, while also enhancing interactivity through artificial intelligence, thereby increasing the sense of immersion within the space.

4.5. Virtual Reality Technology and 3D Modeling in Spatial Design

The integration of Virtual Reality (VR) technology and 3D modeling in spatial design is increasingly becoming an innovative approach in the field of interior design. After completing the initial spatial design, the team used VR technology for an immersive experience to more intuitively perceive the design effects, spatial layout, and details of sensory experiences (

Figure 18, a). Through VR technology, designers can "enter" the virtual space, experiencing the atmosphere, proportions, light and shadow effects, and sensory interactions in a realistic way. This allows them to effectively identify potential issues in the design and make real-time adjustments. This highly interactive approach not only helps designers optimize the spatial layout but also allows clients to "experience" the space in advance and provide feedback for improvements.

Additionally, the team also brought the virtual design to life by printing 3D models (

Figure 18, b). With 3D printing technology, designers can quickly create physical models of the space, further validating design details, particularly in terms of material selection, spatial proportions, and structural integrity. This model allows both designers and clients to see the actual effect of the design more clearly, reducing errors and providing a more accurate reference for the final presentation of the space.

The integration of VR technology and 3D printing not only enhances the visualization and interactivity of spatial design but also significantly improves the efficiency and accuracy of the design process. Designers can conduct multiple tests and adjustments in the virtual space, optimize details on the physical model, and ultimately achieve the most ideal design outcome. In addition, clients and the project team can better understand the potential and sensory effects of the space through immersive experiences and 3D models, enhancing the accuracy and satisfaction of design decisions.

4.6. Conclusion

By integrating spatial perception theory with practical design, the design of the Suzhou Coffee Roasting Factory successfully achieves a dual optimization of functionality and sensory experience. Throughout the design process, we carefully considered the importance of multisensory experiences and flexibly applied sensory design strategies involving vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste, creating a multidimensional and intertwined space. By incorporating digital technology and natural ecological plants, a new spatial model has been created, allowing customers to immerse themselves closely in every step of the coffee roasting process. By carefully considering factors such as color, light and shadow, materials, spatial layout, contextual sound design, and interactive installations, the design maximizes the sensory experience within the space. It creates an environment that not only meets functional requirements for an efficient workspace but also evokes rich emotional resonance and sensory stimulation for each user, ensuring the space’s multifunctionality and immersive quality. We have created a promotional video This video showcases the promotional film produced for the Suzhou Coffee Roasting Factory, available in the

Supplementary Materials: Video S1.

However, despite the significant achievements in multisensory experience and spatial layout, there are still some shortcomings and limitations in the design. For example, the renovated space is relatively crowded, with overly complex design elements. The lack of attention to spatial negative space results in an unclear relationship between density and openness in the layout. Therefore, when optimizing this design project in the future, I will focus on addressing the issue of negative space. Through thoughtful spatial layout, I aim to create a more orderly relationship between density and openness, highlighting key design elements to enhance the overall flow and visual impact of the space.

5. Discussion

This study, based on spatial perception theory, explores how design methods can enhance the sensory experience of interior spaces. Through the analysis of the design case of the Suzhou Coffee Roasting Factory, a series of design strategies based on vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste were proposed, and their effectiveness in practical application was validated. The findings indicate that the thoughtful application of various dimensions of spatial perception not only optimizes the functionality of the space but also significantly enhances customers' experience and emotional connection. However, these findings also require further interpretation and reflection from the perspective of existing research to offer insights for the future development of the interior design field.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

The current study holds significant academic value by providing a novel theoretical framework through a comprehensive analysis of the multidimensional factors of spatial perception. It enriches existing research on spatial perception and multisensory design, offering new perspectives on how spatial design influences customers' emotional experiences and behaviors. The theoretical contribution of this research lies not only in the proposal of multisensory design strategies but also in its systematic analysis, engaging with existing literature and advancing the further development of the spatial perception field.

This study, grounded in phenomenological theory of perception, proposes a spatial perception design strategy centered around multisensory design. The theory of phenomenology of perception emphasizes the role of human sensory experiences in shaping an individual's perception of the world[

8]. In the context of architecture and interior design, while existing research has explored the sensory dimensions of spatial perception[

115], these studies often focus on the impact of a single sense. In contrast, this study proposes several key design strategies by considering multiple sensory elements, including light, color, form, sound, touch, and scent, to regulate the emotional ambiance of the space and enhance the customers' sensory experience. These strategies include: (1) Construction of visual perception: Regulating the emotional ambiance of space through color and light, enriching the spatial form language, and enhancing the depth of visual perception; (2) Auditory perception design: Soundscape design, temporal control of sound, contextual guidance of sound, and immersive sound interaction experience; (3) Application of tactile perception: Creation of direct and indirect tactile perception; (4) Integration of olfactory and gustatory perception: Selection of scent and emotional creation, and the creation of memorable scent spaces, etc. Existing research, such as Lee, Keunhye's study, has pointed out that the synergistic interaction of sensory elements significantly impacts emotional experience[

1]. Building on this, the current study further validates this idea, demonstrating how these sensory elements work together to create a spatial ambiance with emotional regulation capabilities. The combination of light, color, and form can regulate the visual effects of a space, while sound and scent enhance immersion and emotional connection, complementing the dimensions that visual perception alone cannot provide.

According to existing literature, spatial perception is not solely an experience of a single sense, but is achieved through the interaction of multiple senses[

116]. For example, Spence, C. suggests that multisensory elements such as vision, hearing, and touch in interior design can significantly enhance the user's spatial experience[

16]. In this study, we validated the above concepts through a specific case. In the design of the coffee factory, the combination of visual elements (such as lighting changes, material selection, color choices, and the curved design of the coffee bean installations), auditory experiences (such as the choice of music and the rhythmic sound of falling coffee beans), and tactile experiences (including material contrasts and immersive interactive touch installations) created an atmosphere with rhythm and dynamism. This further confirms the critical role of spatial layout and environmental elements in enhancing customers' emotional responses. This practice validates the influence and strategies of visual, auditory, and tactile perception on customers in commercial spaces, as proposed by Spence, C. (2014)[

117]. It demonstrates that the design of the spatial ambiance can effectively enhance customer experience and shopping behavior, guide emotional responses, and increase the sense of immersion in the space, thereby boosting purchasing intent.

In addition, this study also analyzes the importance of olfaction and gustation in interior spaces and proposes relevant design strategies, aligning with the findings of Hill and Smith (2021), who noted that scent and taste can effectively enhance the sensory appeal of a space, thereby influencing customer preferences and purchasing power[

118]. In the study, the use of coffee aromas and interactive coffee bean selection not only enhanced the olfactory experience of the space but also stimulated customers' gustatory needs, thereby increasing their brand loyalty and the memorability of the space. In addition, the study analyzes how the selection of scent directly affects people's emotions and memory. This is similar to the conclusion drawn by Ehrlichman et al. through their experiments, which suggests that when the emotions triggered by a scent align with the emotional content of a memory, the emotion can influence the content of the recalled memory[

119].