1. Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is marked by intrusive thoughts and repetitive behaviors that significantly impair daily functioning [

1,

2]. It remains one of psychiatry’s most complex challenges, with up to 50% of patients failing to achieve remission despite gold-standard interventions like exposure and response prevention (ERP) and serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [

3,

4]. Current barriers to care—including delayed diagnosis, heterogeneous symptom presentations, and trial-and-error treatment selection—demand innovative computational solutions and advances in precision psychiatry [

5]. Deep learning (DL), an innovative branch of artificial intelligence (AI), is uniquely positioned to address these gaps by decoding multidimensional data from neuroimaging, wearable sensors, and digital therapeutics [

6].

Within this context, our brief review offers a concise overview of DL architectures emphasizing clinical translation for OCD. We highlight applications such as advanced predictions, image-based analysis, real-time symptom monitoring, data generation, and dynamic therapeutic support. This manuscript aims to equip researchers and practitioners with basic knowledge for how some fundamental architectures work, clear applications for the field, and evidence-based frameworks for adopting DL tools while addressing ethical challenges in data privacy and algorithmic bias.

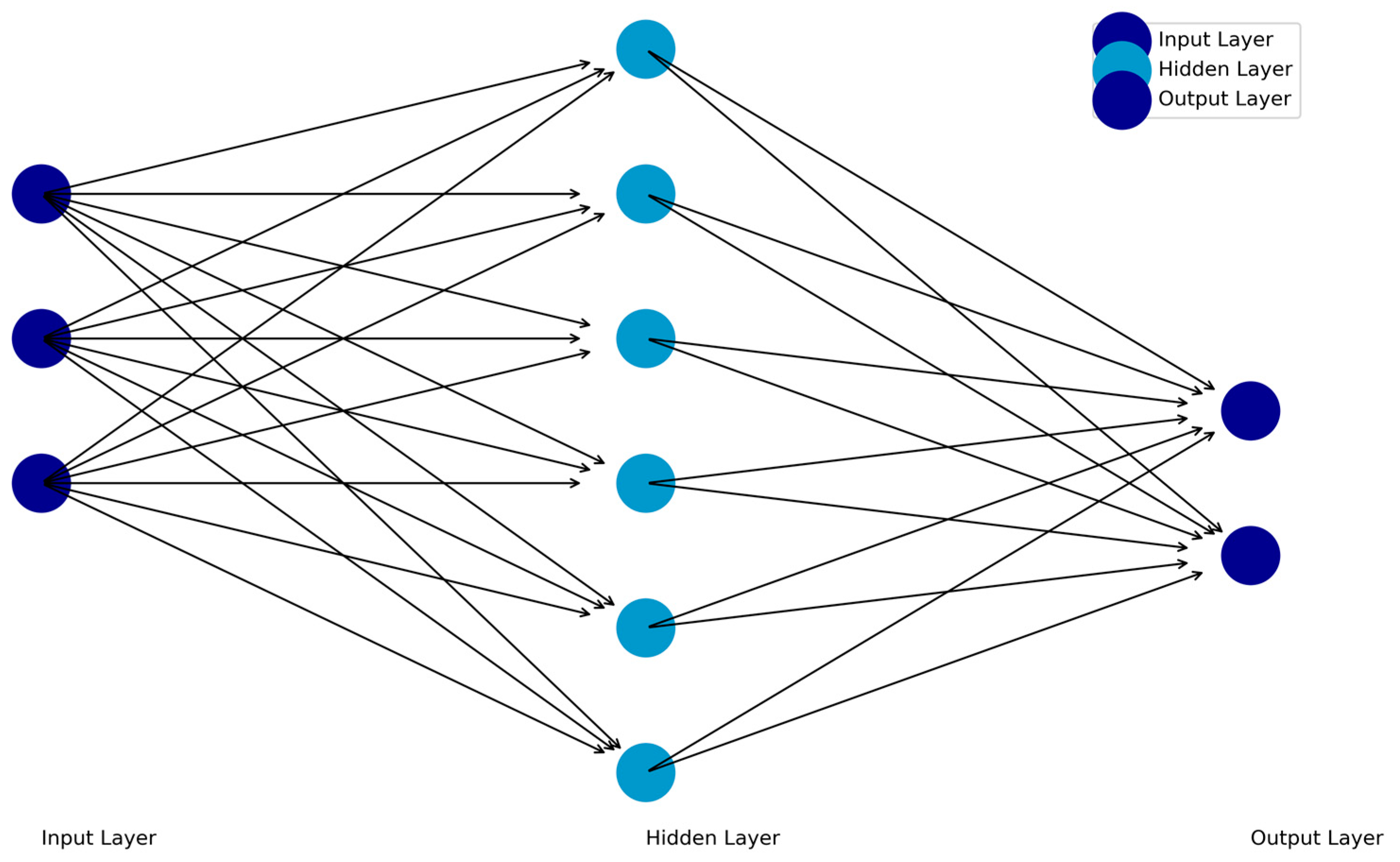

2. Predictive Modeling and Biomarker Identification with Feedforward Neural Networks

Feedforward Neural Networks (FFNNs) are the simplest deep learning architecture. In an FFNN, information flows unidirectionally from an input layer, then through one or more hidden layers, and finally to an output layer. Each neuron in a layer is connected to neurons in the subsequent layer through weights that determine the strength of their relationships. The input data are transferred to hidden layers, which process the data and transfer it to the output layer. The output layer then provides the results of the network’s computations (e.g., outputs based on the input data; Figure 1). The backpropagation algorithm, which adjusts weights to minimize error and optimize performance, then propagates prediction errors backward through the network to refine its weights. Nonlinear relationships can be included with functions included in the hidden layer or output layers of the architecture.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the Feedforward Neural Network (FFNN).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the Feedforward Neural Network (FFNN).

This simple architecture holds substantial promise for advancing personalized approaches in OCD diagnosis and treatment. FFNNs have been instrumental in predicting treatment outcomes for patients undergoing ERP or SSRIs, with performance surpassing traditional models like logistic regression in accounting for complex interactions among clinical, epidemiological, and neuropsychological variables [

7]. For instance, using baseline quantitative electroencephalography (qEEG) data, researchers achieved 80% accuracy in predicting response to transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a neuromodulation technique gaining traction as a treatment for refractory OCD, thus highlighting FFNNs’ role in identifying neural biomarkers that guide treatment personalization [

8]. Such applications provide an opportunity to refine treatment protocols by matching patients to interventions likely to yield optimal outcomes.

FFNNs’ flexibility also makes them well-suited for capturing the heterogeneity of OCD presentations across different populations. In one study, an FFNN successfully predicted OCD severity based on personality traits, religiosity, and demographic factors, offering insights into culturally sensitive symptom presentations such as heightened religious obsessions in Catholic-majority groups [

9]. These findings illuminate how FFNNs can enhance clinical assessment by tailoring diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to patients’ cultural and individual contexts. Moreover, by integrating multimodal data sources, such as neuroimaging, clinical profiles, and ecological momentary assessments, FFNNs hold the potential to dynamically monitor symptoms and predict relapse risk in real-world settings, paving the way for more adaptive and context-aware interventions.

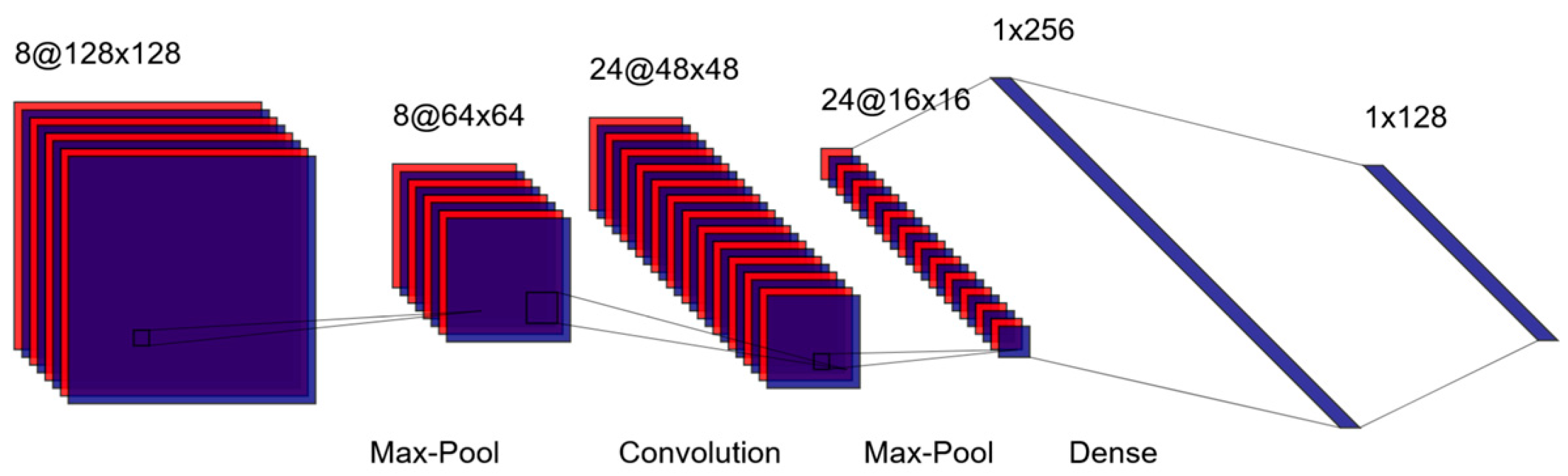

3. Image-Based Classification: Convolutional Neural Networks

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are among the most widely used deep learning architectures for analyzing unstructured data, which are commonly encountered in psychiatric research [

10]. Particularly, CNNs excel at extracting spatial hierarchies of features from image data, making them well-suited for neuroimaging tasks [

11]. A schematic of the LeNet architecture, one of the earliest CNNs, is shown in

Figure 2 [

12]. In CNNs, images are processed through layers of convolutional filters that detect patterns such as edges or textures. Pooling layers then reduce the spatial dimensions of these feature maps, simplifying the data while retaining critical information. Additional convolutional and pooling layers can be added to extract increasingly complex features, culminating in fully connected layers that produce predictions or classifications [

13].

Figure 2.

Schematic of the LeNet Convolutional Neural Network.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the LeNet Convolutional Neural Network.

CNNs have been successfully applied to classify OCD patients and predict treatment outcomes using neuroimaging data, facilitating personalized care strategies. For instance, Kalmady et al. (2022) applied resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to distinguish 188 OCD patients from 200 healthy controls with high accuracy (80%) and sensitivity (83%), demonstrating their potential to identify neural biomarkers associated with OCD. Such insights could guide treatment selection, including neuromodulation techniques like TMS. Beyond diagnosis, CNNs enable the development of AI-driven predictive tools that reduce reliance on manual feature selection, accelerating the analysis of complex neuroimaging datasets [

15]. These advances create opportunities to translate research findings into real-world clinical workflows, such as integrating neurobiological predictors into decision-making systems for treatment-resistant OCD.

Moreover, CNNs are being explored for transdiagnostic features relevant to OCD, opening new avenues for early intervention and risk assessment. For example, CNN-based models have been used to identify subtle physiological markers, such as facial cues correlated with suicidal ideation, achieving 95% accuracy [

16]. These models leverage explainable AI techniques to provide clinicians with interpretable outputs, detailing the neural or behavioral features driving predictions. The potential to combine CNN-derived biomarkers with patient history and symptom profiles not only enhances diagnostic precision but also equips clinicians with actionable data to inform therapeutic interventions.

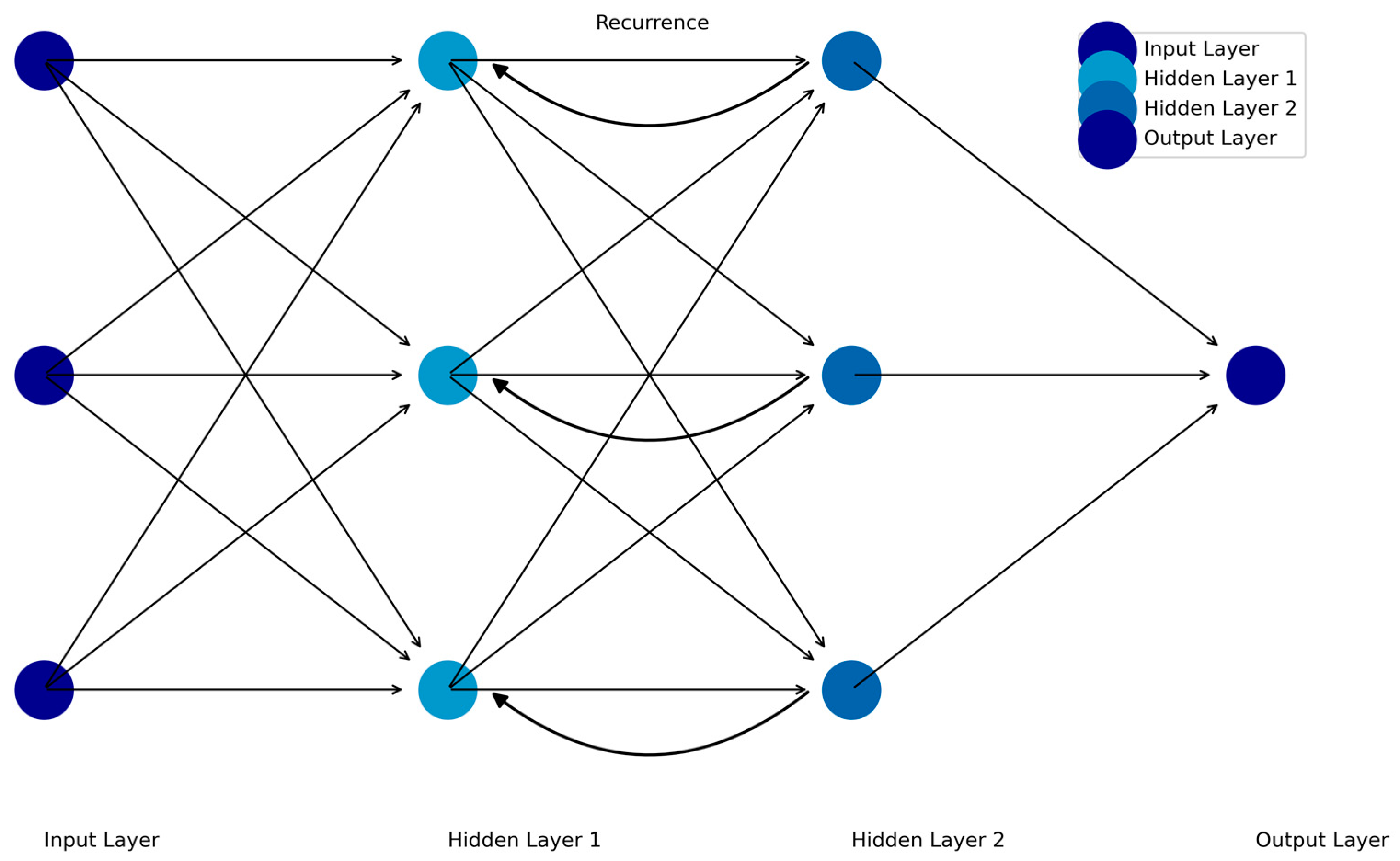

4. Temporal Tracking of Symptoms: Recurrent Neural Networks

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are designed to analyze sequential data by incorporating dependencies between time points, making them particularly suited for time-series data such as fMRI, EEG, and ecological momentary assessments (EMA). Unlike FFNNs or CNNs, RNNs "remember" prior inputs by using feedback loops that pass information from one time step to the next [

17]. This enables RNNs to model dynamic systems where the current state depends on previous states (see

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic of the Recurrent Feedforward Neural Network.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the Recurrent Feedforward Neural Network.

RNNs have demonstrated significant potential in OCD research, particularly for real-time symptom monitoring, predicting treatment responses, and optimizing dynamic therapeutic interventions. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, an advanced RNN variant, mitigate limitations such as vanishing gradients, enabling the modeling of long-term dependencies in sequential data. For instance, Mishra et al. (2025) utilized LSTMs to analyze EEG signals and classify emotional states (positive, negative, neutral) with 97% accuracy, providing a pathway for detecting anxiety-related patterns that frequently co-occur with OCD. In a novel application, Kirsten et al. (2021) developed an unobtrusive system to detect compulsive behaviors in OCD using wearable sensor data and personalized federated learning algorithms. The system achieved an area under the precision-recall curve of 0.954, enabling accurate identification of repetitive compulsions such as excessive handwashing. By combining these tools with dynamic assessment frameworks like EMA, clinicians could better differentiate between adaptive behaviors and symptomatic compulsions, identify early signs of symptom exacerbation, and intervene proactively with tailored therapeutic strategies.

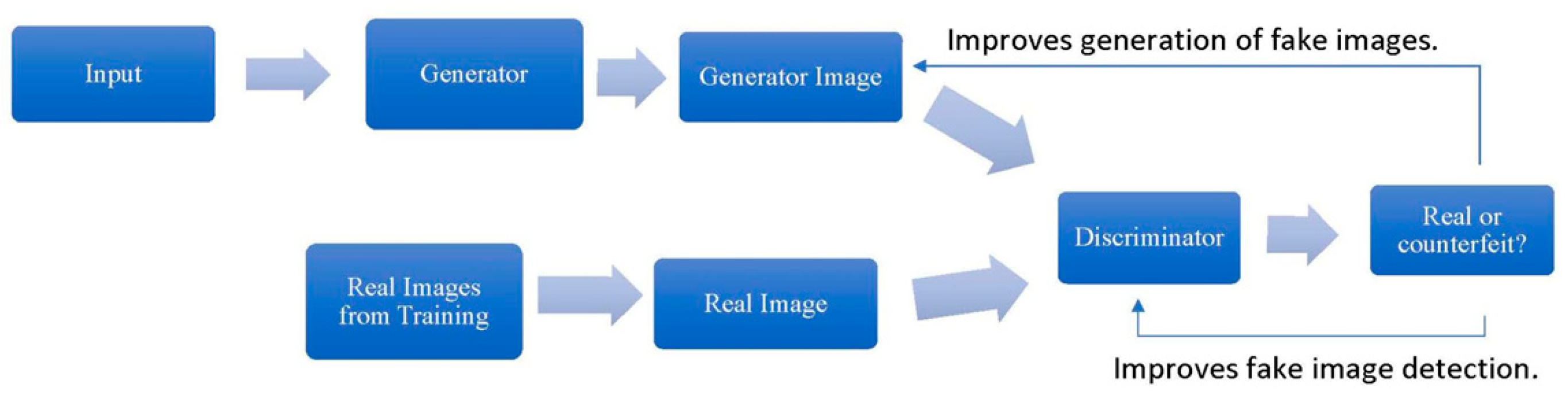

5. Data Generation and Augmentation: Generative Adversarial Networks

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) generate new data based on existing input, such as text, images, or sounds. GANs consist of two neural networks—the generator and the discriminator—that work in opposition to improve their respective tasks. The generator creates synthetic data resembling the training examples, while the discriminator evaluates whether the generated data are real or fake. Through iterative training, both networks refine their abilities until the generator produces realistic outputs indistinguishable from the original data (Goodfellow et al., 2014; see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

General Procedure for Training a Generator and Discriminator.

Figure 4.

General Procedure for Training a Generator and Discriminator.

Based on prior research in psychiatry, GANs hold significant potential for advancing OCD research and treatment, particularly in generating clinical insights from complex datasets or addressing unmet needs in patient populations. While no studies have explicitly examined GAN applications in OCD, their success in related fields provides a roadmap for their future implementation. For example, GANs have been used to decompose neuroimaging data into components relevant and irrelevant to disease progression in Alzheimer’s research, enabling the identification of biomarkers tied to cognitive decline [

20]. Similarly, GANs have augmented training datasets by generating synthetic medical images, such as imputing missing PET data based on corresponding MRI scans, thereby improving diagnostic accuracy [

21]. Applying these techniques to OCD could include imputing missing data in longitudinal Y-BOCS scores or using neuroimaging modalities to predict illness trajectories and treatment response. By synthesizing datasets that integrate diverse imaging, behavioral, or neurophysiological data, GANs could accelerate the development of personalized interventions targeting unique OCD presentations.

GANs also offer promising solutions to challenges pervasive in OCD research, such as addressing demographic disparities and reducing the costs of large-scale data collection. Conditional GANs, for instance, have successfully generated virtual patient cohorts to model clinical biomarker distributions across underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, ensuring more inclusive and equitable datasets for diabetes research [

22]. In the context of OCD, GANs could simulate culturally and demographically diverse patient profiles, enabling the development of interventions tailored to specific populations and reducing biases in treatment recommendations. Moreover, by generating synthetic data to simulate the effects of new therapies, GANs could aid in preclinical testing and refine intervention strategies before costly clinical trials. These efforts not only improve the generalizability of research findings but also bridge the translational gap between experimental models and real-world applications.

6. Automated Screening and Dynamic Therapeutic Support: Transformers

Transformers revolutionized AI by replacing sequential processing with self-attention mechanisms, enabling models to analyze entire datasets simultaneously while identifying contextual relationships across data points [

23]. Unlike RNNs, which process data step-by-step, transformers weigh the importance of each input element (e.g., words in a sentence, pixels in an image) relative to others, allowing them to capture long-range dependencies and global patterns. A transformer consists of an encoder-decoder structure, where the encoder maps input data into a high-dimensional representation, and the decoder generates output based on that representation. The core innovation is the multi-head attention layer, which computes interactions between all input elements in parallel [

23]. This architecture underpins modern large language models (LLMs) like BERT and GPT, which excel at tasks ranging from text generation to multimodal data integration [

24,

25].

Transformers are beginning to demonstrate promising applications in OCD diagnosis and treatment personalization, particularly through the use of LLMs and multimodal data integration. In a diagnostic study, Kim et al., (2024) compared the performance of three LLMs (ChatGPT-4, Gemini Pro, and Llama 3) to medical and mental health professionals in identifying OCD across case vignettes. With ChatGPT-4 achieving perfect diagnostic performance (100%), these architectures surpassed human practitioners in accuracy, highlighting their potential as decision-support tools in psychiatric practice. Another study evaluated four AI models (ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, Claude, and Gemini) using client vignettes representing diverse OCD subtypes, demonstrating that LLMs consistently outperformed psychotherapists in recognizing OCD (90–100% vs. 47.3% accuracy) and recommending evidence-based treatments [

27]. These findings underscore the opportunities for transformers to augment clinical workflows by accurately identifying OCD presentations, minimizing diagnostic delays, and tailoring interventions to specific symptom subtypes. Furthermore, explainable AI tools integrated into these models help clinicians interpret predictions and understand differential recommendations for personalized treatment pathways.

7. AI Driven Personalization: Clinical Implementation

The integration of deep learning into OCD research and clinical care marks a paradigm shift from one-size-fits-all interventions to precision psychiatry. By leveraging deep learning architectures and multimodal data, AI enables dynamic, individualized treatment strategies that adapt to patient-specific symptoms, biomarkers, and environmental contexts. Below, we highlight key themes underlying this transformation.

7.1. Biomarker Identification

Advances in neuroimaging, EEG, and molecular biomarkers have enabled AI models to predict treatment responses in OCD with increasing precision. For example, EEG complexity metrics, such as approximate entropy in the beta frequency band, have been shown to differentiate treatment-resistant from treatment-responsive patients with 89.66% accuracy [

28]. Similarly, neuroimaging studies using fMRI have identified distinct patterns of cortical-striatal-thalamic-cortical (CSTC) circuitry activity that correlate with OCD symptom severity and treatment outcomes [

29]. These biomarkers are now being integrated into AI-driven models to predict responses to interventions like TMS. For example, one study achieved 80% accuracy in predicting treatment response by analyzing connectivity patterns in CSTC circuits using CNNs and machine learning algorithms [

14]. EEG theta-band power predicted TMS outcomes with 80% accuracy, enabling clinicians to prioritize neuromodulation for eligible patients [

8]. These methods vastly improve upon studies that primarily investigate clinical correlates (e.g., EEG) [

1]

Combining theory with the models and data sources discussed in this review, the first AI-created drug was developed—for OCD [

30]. Compound DSP-1181 [

31] progressed from initial screening to preclinical testing in under 12 months—a stark contrast to the industry average of 4–6 years [

32]. By leveraging AI's ability to analyze vast chemical libraries and optimize molecular structures, researchers aim to accelerate the identification of promising candidates while reducing costs and increasing efficiency. Of course, challenges remain, as only 10% of compounds entering Phase 1 trials typically achieve regulatory approval [

32]. Nevertheless, AI's capability to identify novel targets and optimize animal models for preclinical studies holds promise for enhancing success rates in OCD drug development [

21].

7.2. Digital Therapeutics and Real-Time Interventions

Deep learning architectures represent a transformative leap in mental health research and clinical care. These technologies are poised to address long-standing challenges in psychiatry, such as the need for scalable, personalized interventions and nuanced understanding of complex mental health conditions like OCD. These models can synthesize patient-specific data, interpret unstructured inputs (e.g., therapy transcripts or self-reports), and provide actionable insights for diagnosis and treatment. Their ability to integrate multimodal datasets, including behavioral, physiological, and linguistic data, heralds a new era in precision psychiatry—offering the potential to optimize treatment strategies and improve accessibility to evidence-based care. In the context of OCD, these architectures are already becoming integrated into the psychotherapy delivery process. AI-powered mobile apps like Wysa and Woebot deliver personalized ERP to adjust task difficulty with FFNNs and RNNs based on real-time symptoms and physiological data (e.g., galvanic skin response). Although more research is needed on their long-term benefit—and optimization is required to improve the user experience—many of them provide effective mental health support and successfully meet a high need for services (Farzan et al., 2025).

Moreover, transformers like ChatGPT are reshaping therapeutic workflows. Not only are they proving themselves diagnostically [

26], they are being tailored to provide psychoeducation to each patient’s level of understanding, identify cognitive distortions in text, challenge automatic thoughts, create reflection prompts for homework assignments, and monitor CBT treatment fidelity [

34]. Another approach is the development of AI-guided exposure therapy for fear of heights with virtual reality environments and an AI therapist [

35]. In this study, the AI therapist, driven by GPT-4, interacted with patients, guiding them through exposure exercises while monitoring their emotional state and adjusting the intensity. The system's design incorporated ethical principles translated into technical requirements, including trust-building and bias detection. Preliminary evaluation showed that patients were satisfied with the virtual reality environment but noted that the AI therapist needed improvements in human-like interaction and empathy.

8. Challenges and Future Directions

8.1. Ethics and OCD Research

AI application in OCD grapples with significant ethical considerations, particularly concerning data privacy, security, and potential biases [

36,

37]. The collection and utilization of personal data, especially sensitive psychiatric information, necessitate stringent measures to ensure data protection and confidentiality. Researchers must carefully navigate data access protocols and implement robust security measures to prevent unauthorized disclosure or misuse [

35]. Furthermore, algorithmic bias poses a substantial challenge, as LLMs can inadvertently perpetuate harmful biases present in their training data, leading to inequitable or discriminatory outcomes. To mitigate these risks, researchers must prioritize cultural sensitivity, inclusivity, and fairness in AI system design and evaluation. This involves curating diverse and representative datasets, employing bias-detection techniques, and continuously monitoring AI performance across different demographic groups to prevent exacerbating health disparities. Moreover, transparency in AI development is essential for fostering trust and accountability. Researchers should provide clear and comprehensive information about the system's development team, ownership, funding sources, business model, training methodologies, and primary beneficiaries [

36].

Further, although vignettes have been promising in clinical prediction [

26,

27], they do not reflect the complex, multi-step data gathering and synthesizing required for real-world clinical decisions. For example, using a curated dataset with 2,400 real patients cases with common abdominal pathologies, LLMs gathered and synthesized additional information to reach a diagnosis and treatment plan. The study found that clinicians had a mean diagnostic accuracy of 88%, while the LLM’s mean accuracy ranged from 46% - 54%, failing to accurately diagnose patients across all pathologies, follow diagnostic or treatment guidelines, or correctly interpret lab results. Consequently, researchers interested in applying LLMs in OCD research should consider testing them on real-world data (e.g., intakes, therapy transcripts).

In addition, assessing AI's efficacy and potential harm in research settings raises complex ethical dilemmas. The rapid proliferation of digital platforms necessitates thorough and ongoing evaluation of their potential benefits and risks [

36]. Without such evaluation, timely responses to unforeseen adverse effects or unintended consequences become exceedingly difficult [

35]. To address this gap, there is a growing need for structured frameworks and ethical guidelines tailored to evaluate LLM tools in mental health research. These frameworks should encompass key ethical principles such as beneficence, non-maleficence, respect for autonomy, and justice [

36]. The inherent complexity of AI interactions underscores the importance of actively involving users in the development process and continuously monitoring AI performance to detect and address unintended consequences that may arise [

35].

8.2. Ethics and OCD Clinical Care

In the realm of clinical care, AI tools designed for OCD treatment, such as conversational agents and virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET), introduce concerns about the distortion of the therapeutic frame, the potential blurring of boundaries, and the compromise of the patient-therapist relationship [

35,

38]. While AI-driven interventions may simulate therapeutic conversations, they often lack the depth and nuance of genuine engagement with a human therapist, possibly endangering user autonomy and psychological integrity if not properly understood. Moreover, on-demand conversational access may undermine established therapeutic practices, hindering opportunities to cultivate realistic interpersonal relationships and support networks [

38]. There are also ethical considerations with the use of autonomous VRET, and ensuring minimum standards concerning autonomy, control, fairness, transparency, reliability, security, and data protection [

35].

Furthermore, ensuring patient safety and effectively managing crisis situations are paramount ethical considerations in AI-driven OCD care [

37]. For instance, AI systems must be equipped to detect signs of suicidality, recognize contraindications for specific interventions, and proactively manage symptom deterioration [

35]. Clear protocols and readily accessible resources for handling emergencies are essential, as well as seamless mechanisms for incorporating human therapists into the treatment process when necessary [

36]. Transparency and comprehensibility of AI algorithms are equally critical, empowering patients to understand how these tools function and preventing potential misuse [

35]. Addressing the digital divide and ensuring equitable access to AI-based interventions are also vital for responsible and ethical implementation in clinical settings, preventing further disparities.

9. Toward Precision OCD Care

The integration of AI into research and treatment represents a vital step toward precision psychiatry in OCD. By harnessing deep learning architectures, researchers are uncovering novel biomarkers, predicting treatment responses, and tailoring interventions to individuals. AI-driven tools are enabling the identification of neural predictors of treatment outcomes, the generation of personalized exposure stimuli, and the development of dynamic therapeutic platforms that adapt to real-time patient feedback. These innovations hold promise for addressing the heterogeneity of OCD and improving outcomes for patients who do not respond to standard treatments. However, achieving true precision care requires overcoming significant challenges, including ethical considerations surrounding data privacy, algorithmic bias, and equitable access to AI-driven interventions. As these technologies mature, a multidisciplinary approach that combines cutting-edge AI with rigorous clinical validation and ethical oversight will be essential to fully realize their potential in transforming OCD care.

Funding

This work is funded in part by a grant provided by the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (NARSAD, PI: BZ). For the past three years, BZ has consulted with Biohaven Pharmaceuticals and received royalties from Oxford University Press; these relationships are not related to the work described here.

Author Contributions

BZ and LB equally contributed to the literature review, writing, and editing of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OCD |

Obsessive-compulsive disorder |

| ERP |

Exposure and response prevention |

| SSRIs |

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| DL |

Deep learning |

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| FFNNs |

Feedforward neural networks |

| qEEG |

Quantitative electroencephalography |

| TMS |

Transcranial magnetic stimulation |

| CNNs |

Convolutional neural networks |

| fMRI |

Functional magnetic resonance imagine |

| RNNs |

Recurrent neural networks |

| EMA |

Ecological momentary assessment |

| LSTM |

Long short-term memory |

| GANs |

Generative adversarial networks |

| LLMs |

Large language models |

| CSTC |

Cortical-striatal-thalamic-cortical |

| VRET |

Virtual reality exposure therapy |

References

- Zaboski, B.A.; Gilbert, A.; Hamblin, R.; Andrews, J.; Ramos, A.; Nadeau, J.M.; Storch, E.A. Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: The Pediatric Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (PQ-LES-Q). Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 2019, 83, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinari, A.D.; Andrews, J.L.; Zaboski, B.A.; Kay, B.; Hamblin, R.; Gilbert, A.; Ramos, A.; Riemann, B.C.; Eken, S.; Nadeau, J.M. Quality of Life and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents in Residential Treatment Facilities. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth 2019, 36, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, K.; Jacobi, T.; Kunas, S.L.; Elsner, B.; Reuter, B.; Lueken, U.; Kathmann, N. Identifying CBT Non-Response among OCD Outpatients: A Machine-Learning Approach. Psychotherapy Research 2021, 31, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, C.; Boisseau, C.L. Exposure and Response Prevention in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Current Perspectives. PRBM 2019, Volume 12, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.S.; Williams, L.M.; Steiner, J.; Leboyer, M.; Carvalho, A.F.; Berk, M. The New Field of ‘Precision Psychiatry. ’ BMC Med 2017, 15, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppe, G.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Durstewitz, D. Deep Learning for Small and Big Data in Psychiatry. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 46, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomoni, G.; Grassi, M.; Mosini, P.; Riva, P.; Cavedini, P.; Bellodi, L. Artificial Neural Network Model for the Prediction of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Treatment Response. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2009, 29, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metin, S.Z.; Balli Altuglu, T.; Metin, B.; Erguzel, T.T.; Yigit, S.; Arıkan, M.K.; Tarhan, K.N. Use of EEG for Predicting Treatment Response to Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Clin EEG Neurosci 2020, 51, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaboski, B.A.; Wilens, A.; McNamara, J.P.; Muller, G.N. Predicting OCD Severity from Religiosity and Personality: A Machine Learning and Neural Network Approach. Journal of Mood & Anxiety Disorders 2024, 8, 100089. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A.; Lipton, Z.C.; Li, M.; Smola, A.J. Dive Into Deep Learning; 2022. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Durstewitz, D.; Koppe, G.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Deep Neural Networks in Psychiatry. Molecular psychiatry 2019, 24, 1583–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv, 2014; arXiv:1406.2661. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmady, S.V.; Paul, A.K.; Narayanaswamy, J.C.; Agrawal, R.; Shivakumar, V.; Greenshaw, A.J.; Dursun, S.M.; Greiner, R.; Venkatasubramanian, G.; Reddy, Y.C.J. Prediction of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Importance of Neurobiology-Aided Feature Design and Cross-Diagnosis Transfer Learning. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging 2022, 7, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krohn, J.; Beyleveld, G.; Bassens, A. Deep Learning Illustrated; Addison-Wesley Professional. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rashed, A.E.E.; Atwa, A.E.M.; Ahmed, A.; Badawy, M.; Elhosseini, M.A.; Bahgat, W.M. Facial Image Analysis for Automated Suicide Risk Detection with Deep Neural Networks. Artif Intell Rev 2024, 57, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C.C. Neural Networks and Deep Learning: A Textbook, Springer, 2018.

- Mishra, S.; Seth, S.; Jain, S.; Pant, V.; Parikh, J.; Chugh, N.; Puri, Y. An Emotionally Intelligent Haptic System–An Efficient Solution for Anxiety Detection and Mitigation. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2025, 260, 108590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsten, K.; Pfitzner, B.; Löper, L.; Arnrich, B. Sensor-Based Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Detection With Personalised Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 20th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA); December 2021; pp. 333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J.; Lei, B.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Y. DecGAN: Decoupling Generative Adversarial Network Detecting Abnormal Neural Circuits for Alzheimer’s Disease 2021.

- Tripathi, S.; Augustin, A.I.; Dunlop, A.; Sukumaran, R.; Dheer, S.; Zavalny, A.; Haslam, O.; Austin, T.; Donchez, J.; Tripathi, P.K.; et al. Recent Advances and Application of Generative Adversarial Networks in Drug Discovery, Development, and Targeting. Artificial Intelligence in the Life Sciences 2022, 2, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.; Mohan, D.; Frank, S.; Setlur, S.; Govindaraju, V.; Ramanathan, M. Generative Adversarial Networks for Modeling Clinical Biomarker Profiles in Under-Represented Groups. Preprints, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A. Attention Is All You Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Dai, Y.; Yu, P.S.; Sun, L. A Comprehensive Survey of AI-Generated Content (AIGC): A History of Generative AI from GAN to ChatGPT 2023.

- Wu, T.; He, S.; Liu, J.; Sun, S.; Liu, K.; Han, Q.-L.; Tang, Y. A Brief Overview of ChatGPT: The History, Status Quo and Potential Future Development. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2023, 10, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Leonte, K.G.; Chen, M.L.; Torous, J.B.; Linos, E.; Pinto, A.; Rodriguez, C.I. Large Language Models Outperform Mental and Medical Health Care Professionals in Identifying Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkovich, I. Harnessing Large Language Models for Identification and Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder 2024.

- Altuğlu, T.B.; Metin, B.; Tülay, E.E.; Tan, O.; Sayar, G.H.; Taş, C.; Arikan, K.; Tarhan, N. Prediction of Treatment Resistance in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Patients Based on EEG Complexity as a Biomarker. Clinical Neurophysiology 2020, 131, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kang, Q.; Gu, H. A Comprehensive Review for Machine Learning on Neuroimaging in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BioPharm International First Drug Created via AI to Enter Clinical Trials, Signaling New Era for Pharma Available online:. Available online: https://www.biopharminternational.com/view/first-drug-created-ai-enter-clinical-trials-signaling-new-era-pharma (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd. Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma and Exscientia Joint Development New Drug Candidate Created Using Artificial Intelligence (AI) Begins Clinical Study Available online:. Available online: https://www.sumitomo-pharma.com/news/20200130.html (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Burki, T. A New Paradigm for Drug Development. The Lancet Digital Health 2020, 2, e226–e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzan, M.; Ebrahimi, H.; Pourali, M.; Sabeti, F. Artificial Intelligence-Powered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Chatbots, a Systematic Review. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry 2025, 20, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, F.; He, T.; Cheng, X.; Yang, B.X.; Ho, G.W.K.; Fu, G. A Generic Review of Integrating Artificial Intelligence in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy 2024.

- Obremski, D.; Wienrich, C. Autonomous VR Exposure Therapy for Anxiety Disorders Using Conversational AI—Ethical and Technical Implications and Preliminary Results. Journal of Computer and Communications 2024, 12, 111–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, A.; Aboujaoude, E. Describing the Framework for AI Tool Assessment in Mental Health and Applying It to a Generative AI Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Platform: Tutorial. JMIR Formative Research 2024, 8, e62963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Liu, F.; Yang, K.; Li, Z.; Na, H.; Sheu, Y.; Zhou, P.; Moran, L.V.; Ananiadou, S.; CliDon, D.A.; et al. Large Language Models in Mental Health Care.

- Vagwala, M.K.; Asher, R. Conversational Artificial Intelligence and Distortions of the Psychotherapeutic Frame: Issues of Boundaries, Responsibility, and Industry Interests. The American Journal of Bioethics 2023, 23, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).