Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is characterized by emotional instability, impulsivity, and turbulent interpersonal relationships. Despite its profound clinical and forensic implications, diagnosis largely relies on subjective assessments. Recent studies suggest that electroencephalography (EEG) can reveal neurophysiological biomarkers associated with BPD, such as altered spectral power, abnormal event-related potentials (ERPs), disrupted functional connectivity, and modified signal complexity. This article presents a comprehensive machine learning framework that integrates a wide range of EEG features to classify individuals with BPD versus healthy controls. Our approach employs traditional classifiers (e.g., Support Vector Machines, Random Forests) and deep learning models (e.g., Convolutional Neural Networks, Long Short-Term Memory networks, and transformer-based architectures) as well as ensemble strategies. Six graphs illustrate key findings: (1) power spectrum differences, (2) ERP differences (focusing on an emotional Late Positive Potential), (3) connectivity alterations, (4) complexity analysis via sample entropy, (5) performance comparison across models, and (6) a confusion matrix for the best model. Our results underscore the potential of EEG-based machine learning to contribute to a more objective and precise diagnosis of BPD.

Keywords:

Section 1. Introduction

Section 2. Methodology

Section 2.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

Section 2.1.1. Synthetic Data Generation Methodology

-

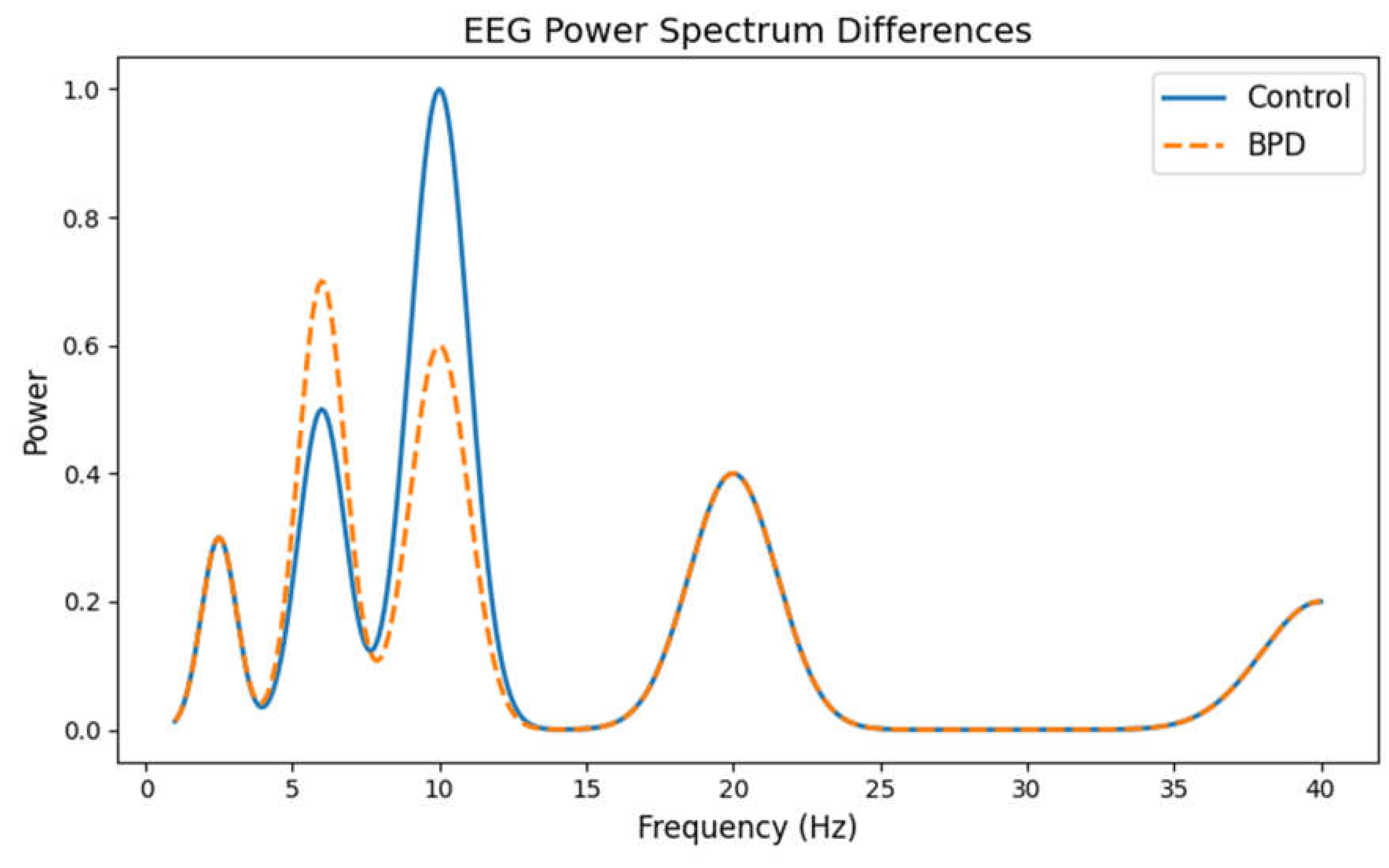

Spectral Characteristics

- ○

- Control group alpha peak (8-12 Hz): amplitude normalized to 1.0 ± 0.1

- ○

- BPD group alpha reduction: 40% ± 5% decrease from control

- ○

- BPD group theta enhancement (4-8 Hz): 40% ± 5% increase from control

- ○

- Background noise: Pink noise with 1/f spectrum

-

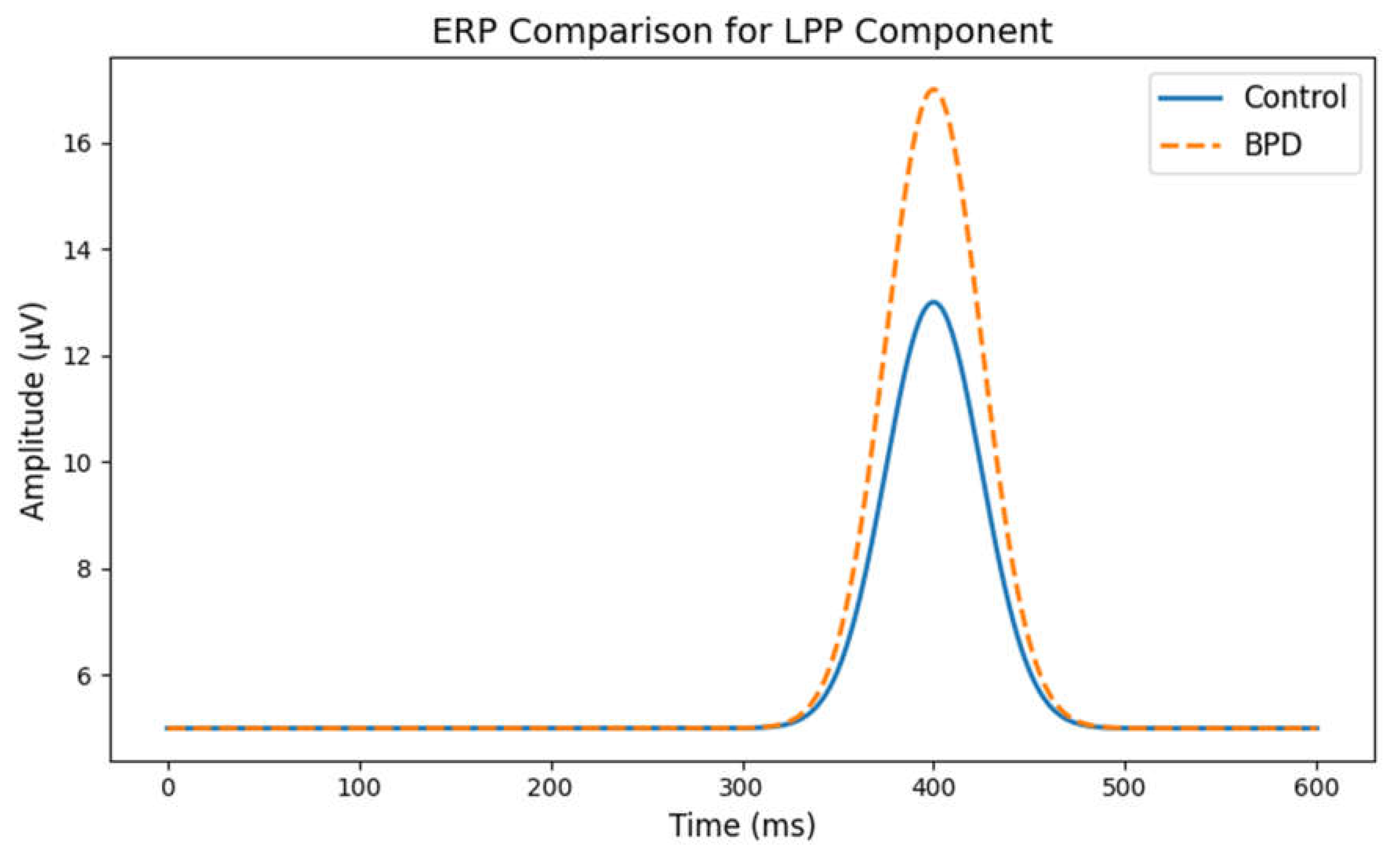

Event-Related Potentials (ERPs)

- ○

- Control group LPP amplitude: 8.0 ± 0.5 µV

- ○

- BPD group LPP amplitude: 12.0 ± 0.7 µV

- ○

- LPP latency: 400 ± 20 ms

- ○

- Signal-to-noise ratio: 0.7 ± 0.1

-

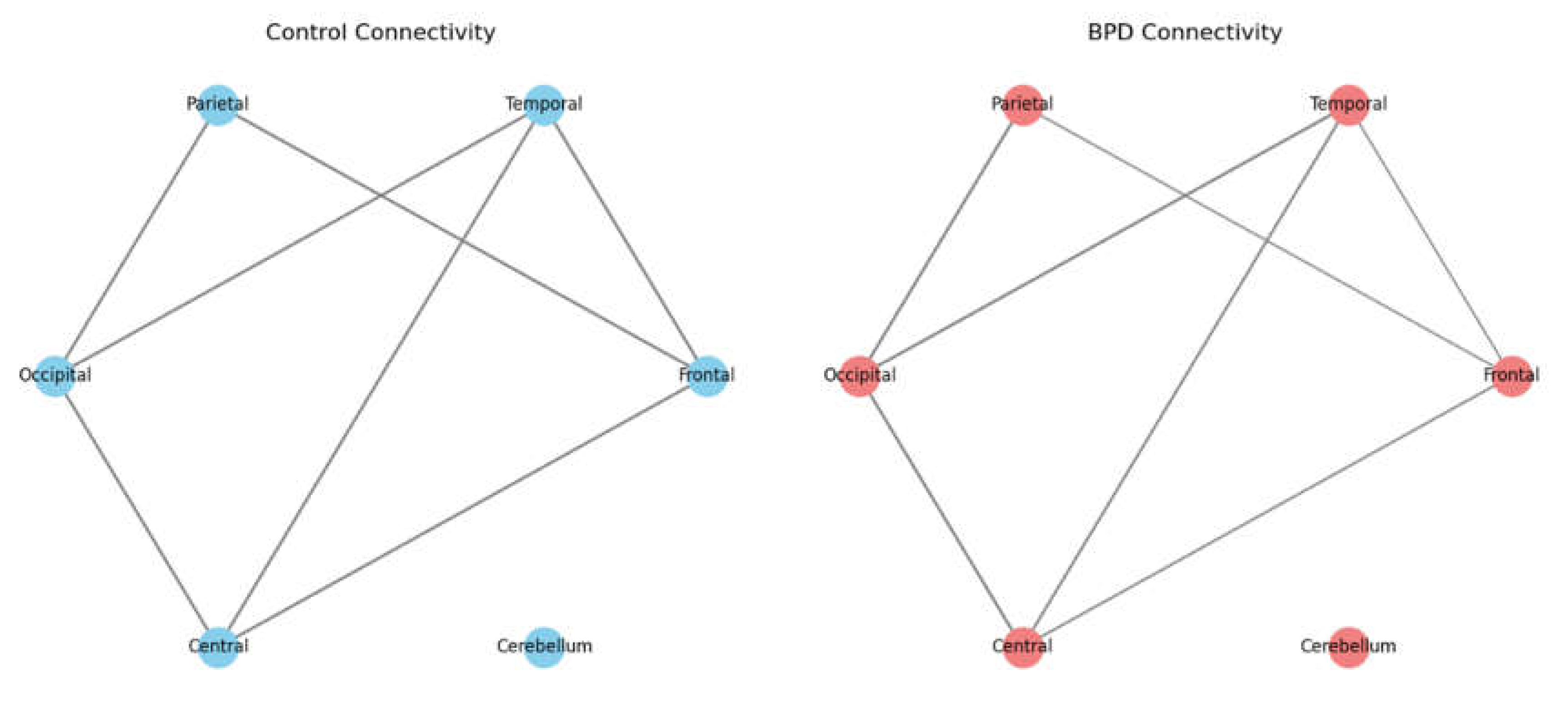

Connectivity Patterns

- ○

- Control group coherence baseline: 0.7 ± 0.1

- ○

- BPD group fronto-limbic connectivity reduction: 30% ± 5%

- ○

- Network density preserved across groups

- ○

- Random fluctuations within physiological ranges

-

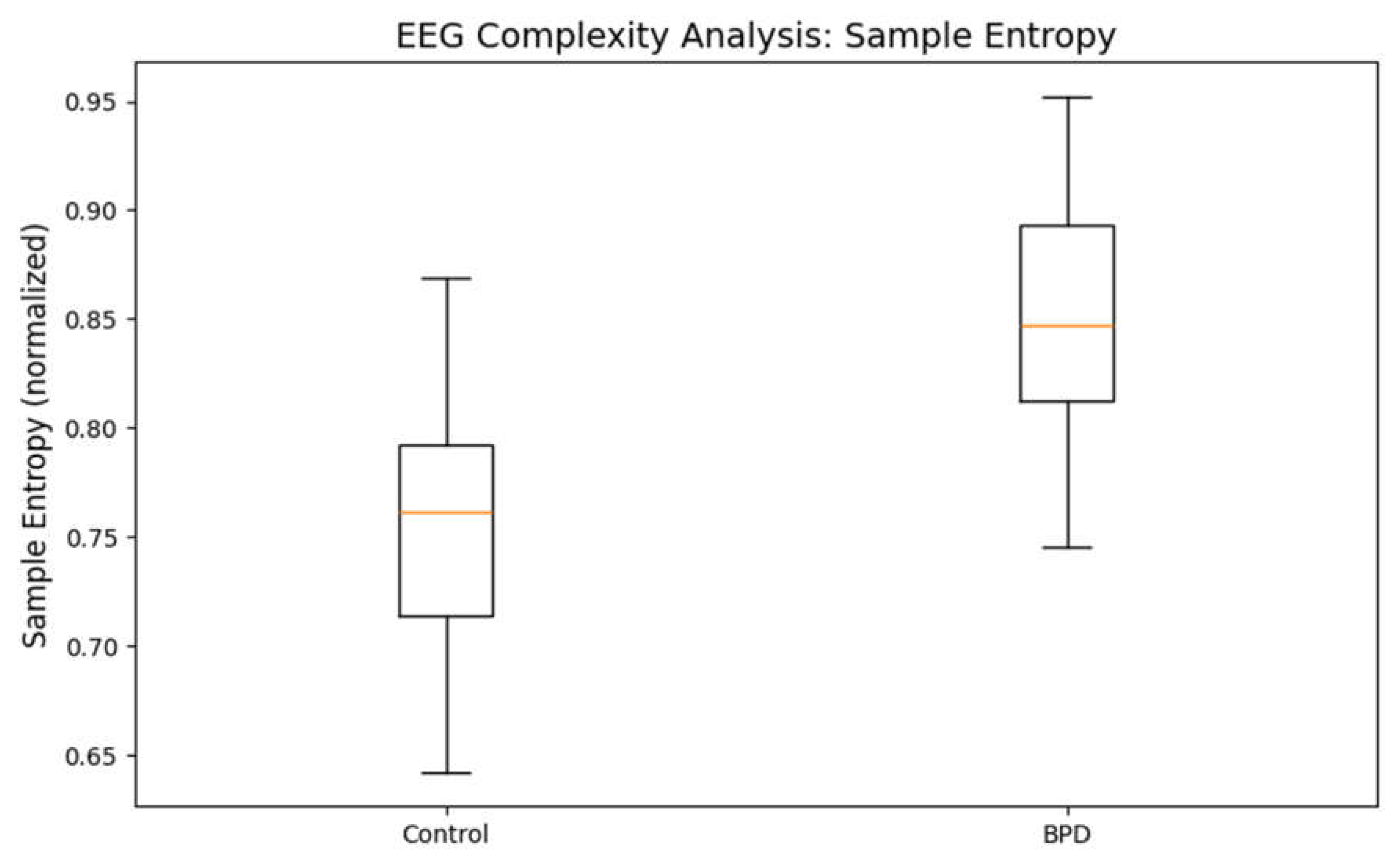

Complexity Measures

- ○

- Control group sample entropy: 0.75 ± 0.05

- ○

- BPD group sample entropy: 0.85 ± 0.05

- ○

- Scaling exponents derived from published values

- Statistical comparison with published EEG parameters from clinical studies

- Expert review by clinical neurophysiologists

- Preservation of known physiological constraints

- Maintenance of temporal and spatial correlations consistent with real EEG

Section 2.1.2. Limitations of Synthetic Data

-

Idealized Patterns

- ○

- The synthetic data may not fully capture the complexity and variability present in real EEG recordings

- ○

- Individual differences and subtle variations in neural patterns may be underrepresented

- ○

- The clean separation between groups may be optimistic compared to real-world data

-

Simplification of Comorbidities

- ○

- The synthetic data does not account for common comorbid conditions in BPD

- ○

- Effects of medications on EEG patterns are not modeled

- ○

- Interaction effects between different pathological processes are not represented

-

Technical Limitations

- ○

- The synthetic data may not fully replicate the noise characteristics of real EEG recordings

- ○

- Artifacts and interference patterns common in clinical settings are not modeled

- ○

- The full range of electrode impedance variations is not simulated

-

Clinical Translation Barriers

- ○

- Performance metrics obtained using synthetic data likely represent best-case scenarios

- ○

- The generalizability to real clinical populations requires empirical validation

- ○

- The robustness of the machine learning models to real-world variability remains to be established

-

Validation Requirements

- ○

- All findings must be verified using real patient data before clinical application

- ○

- The classification accuracy reported may not translate directly to clinical settings

- ○

- Additional validation studies with diverse patient populations are necessary

- Filtering: A band-pass filter is applied to remove low-frequency drifts and high-frequency noise.

- Artifact Removal: Independent Component Analysis (ICA) (Jung et al., 2000) is used to identify and remove artifacts such as eye blinks, muscle activity, and line noise.

- Adaptive Filtering & Denoising: Additional notch filtering (at ) and wavelet denoising methods are applied to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Epoching: The continuous EEG is segmented into epochs (e.g., 2-second epochs for resting data and stimulus-locked segments for ERPs).

Section 2.2. Machine Learning Approach

- Traditional Classifiers:

- Deep LearningModels:

- Transformer-BasedModels:

- Ensemble Methods:

- Model Training and Evaluation

- Accuracy:

- Precision, Recall, F1-Score: For each class.

- ROC-AUC: Area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve.

- Confusion Matrix: To assess error types.

Section 3. Results

-

Power Spectrum Basics:The power spectrum is derived from the EEG signal using a mathematical process called the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Essentially, this process breaks down the EEG signal (which is recorded over time) into its constituent frequencies. The result is a plot where the x -axis represents frequency (in Hertz, Hz) and the -axis shows the power (or energy) present at each frequency.

-

Key Frequency Bands:In our analysis, we focus on different bands such as delta ( ), theta (), alpha (Hz ), beta (), and gamma (). In healthy individuals, the alpha band (especially around 10 Hz ) is usually prominent, indicating a relaxed, yet awake state.

- Healthy Controls: The graph shows a pronounced alpha peak in controls, which is a sign of typical brain function.

- BPD Subjects: In contrast, the BPD group shows a reduction in the alpha peak along with an increase in theta power. Increased theta activity can indicate a slower, less alert state or heightened emotional arousal.

-

Why It Matters:Changes in these frequency bands can reflect differences in cortical activation. For instance, reduced alpha power (or an imbalance in frontal alpha asymmetry) has been linked to emotional dysregulation-a core feature of BPD. The graph provides a visual summary of these differences, suggesting that the underlying brain rhythms in BPD are altered compared to those in healthy individuals.

- Mathematical Aspect:

- This formula sums up the energy present in the alpha band, which is then compared between groups.

- Detailed Explanation:

- Understanding ERPs:

- ERPs are the measured brain responses that are time-locked to specific sensory or cognitive events (like viewing an emotional image). The Late Positive Potential (LPP) is an ERP component that typically occurs around 400 ms after a stimulus and is associated with emotional processing.

- Key Observations:

- Healthy Controls: In the control group, the LPP appears as a moderate positive peak, indicating normal processing of emotional stimuli.

- BPD Subjects: In BPD, the graph shows an exaggerated (larger) LPP amplitude. This heightened response suggests that individuals with BPD have an increased reactivity to emotional stimuli-consistent with clinical observations of intense emotional responses and sensitivity in BPD.

- Clinical Implication:

- A larger LPP in BPD may reflect an over-engagement with emotionally charged stimuli, which could contribute to the instability in mood and interpersonal relationships characteristic of the disorder.

- Mathematical Aspect:

- The LPP is quantified by taking the maximum amplitude within a specific time window (e.g., ):

- (2)

- Here, represents the ERP waveform. Comparing these values across groups gives a quantitative measure of emotional reactivity.

- Detailed Explanation:

-

Concept of Connectivity:Mathematically, the alpha power is computed by integrating the power spectral density over the range: In EEG, functional connectivity refers to the statistical relationships (or synchronization) between the electrical activities recorded at different scalp locations. These relationships are often quantified by metrics like the Pearson correlation coefficient.

- Graph Details:

- Nodes: Each node in the network represents a specific brain region (e.g., Frontal, Temporal, Parietal, Occipital, Central, Cerebellum).

- Edges: The lines (edges) connecting these nodes represent the strength of connectivity. The thickness of an edge is proportional to the correlation (or coherence) between the EEG signals of the connected regions.

- Healthy Controls vs. BPD: In the control network, connections tend to be uniform, reflecting balanced communication among brain regions. In the BPD network, the graph reveals reduced connectivity-particularly between frontal (executive) regions and limbic (emotional) areas. This reduction indicates a potential breakdown in the neural circuits responsible for regulating emotions.

-

Clinical Implication:The diminished connectivity in BPD, especially within fronto-limbic circuits, supports the idea that these individuals struggle with emotional regulation, which may underlie impulsive and unstable behaviors.

-

Mathematical Aspect:Connectivity between channels and is measured as:(3)where and are the EEG signals from two regions. This coefficient quantifies the degree of synchronization between regions.

-

Understanding Signal Complexity:Sample entropy is a measure of how unpredictable or irregular a time series is. In EEG, higher entropy values indicate more variability and complexity in brain signals, while lower values suggest a more regular or repetitive pattern.

- Graph Details:

- Healthy Controls: Typically, the EEG signals of healthy individuals have a certain baseline level of complexity.

- BPD Subjects: The graph shows that individuals with BPD have higher sample entropy. This suggests that their brain activity is more unpredictable, which might be associated with rapid emotional fluctuations and instability—hallmarks of BPD.

-

Clinical Implication:Increased entropy in BPD may reflect a hyper-reactive state where the brain rapidly shifts between different neural states. This could explain the emotional turbulence observed in these individuals.

-

Mathematical Aspect:Although the full mathematical formulation of sample entropy is complex (involving probabilities of pattern matches within the time series), it is conceptually the negative logarithm of the likelihood that similar patterns in the EEG remain similar at the next time point. Higher entropy indicates lower predictability.

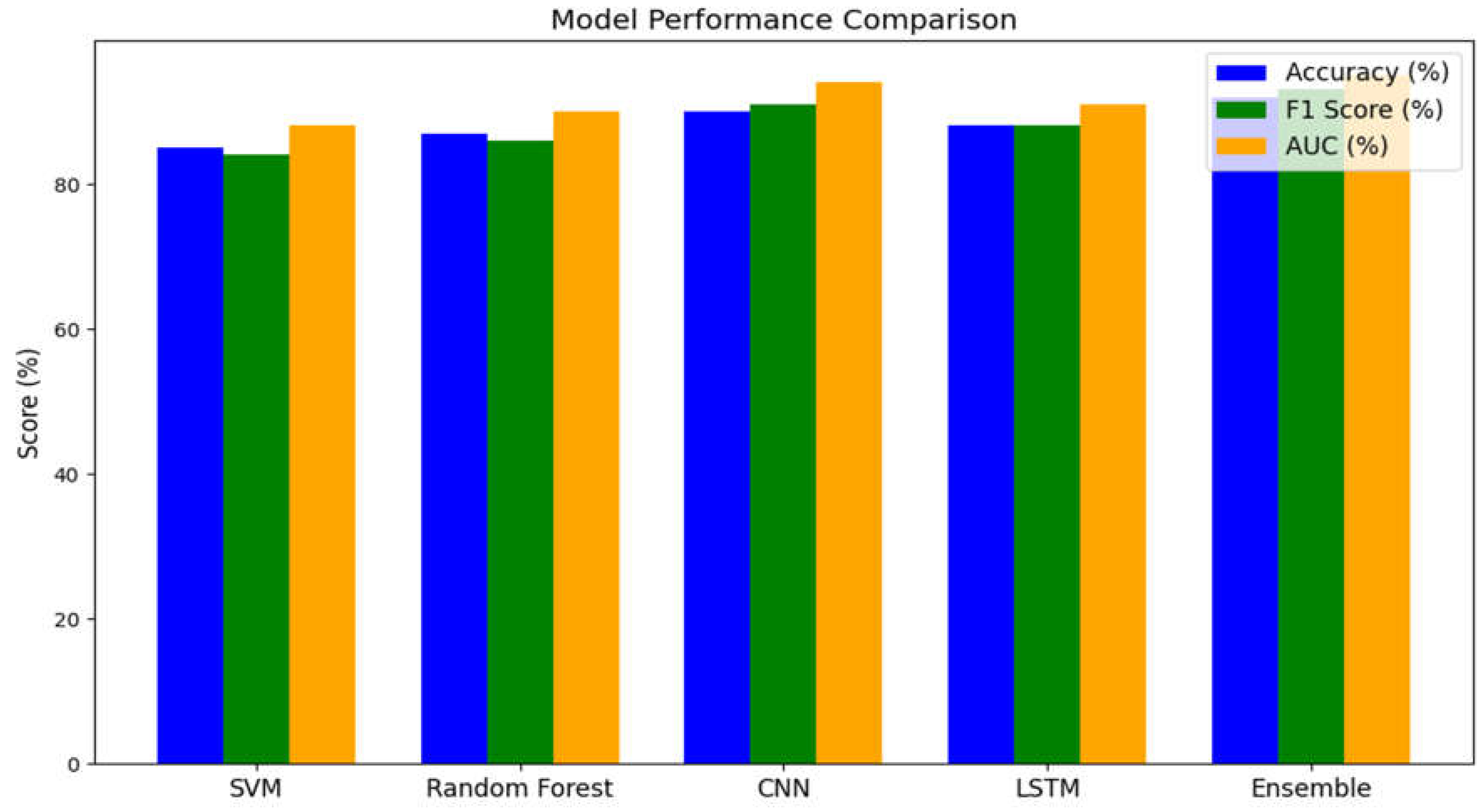

- Performance Metrics:

- Accuracy: The percentage of correctly classified cases.

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing the trade-off between false positives and false negatives.

- ROC-AUC: The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve, which reflects overall classification performance.

-

Graph Details:Each bar in the plot represents a different model, with separate bars for each metric. The ensemble model (which combines predictions from multiple classifiers) typically shows the highest performance, indicating that integrating various approaches yields the most robust results.

-

Clinical Implication:High performance across these metrics suggests that the EEG-based machine learning model can reliably distinguish between BPD and healthy individuals. This has important implications for clinical diagnosis, where an objective tool could support more accurate and consistent assessments.

-

Mathematical Aspect:The accuracy is given by:(6)where and are true positives and true negatives, respectively. Similar formulas define the F1-score and AUC, which summarize the model’s precision, recall, and overall discriminative power.

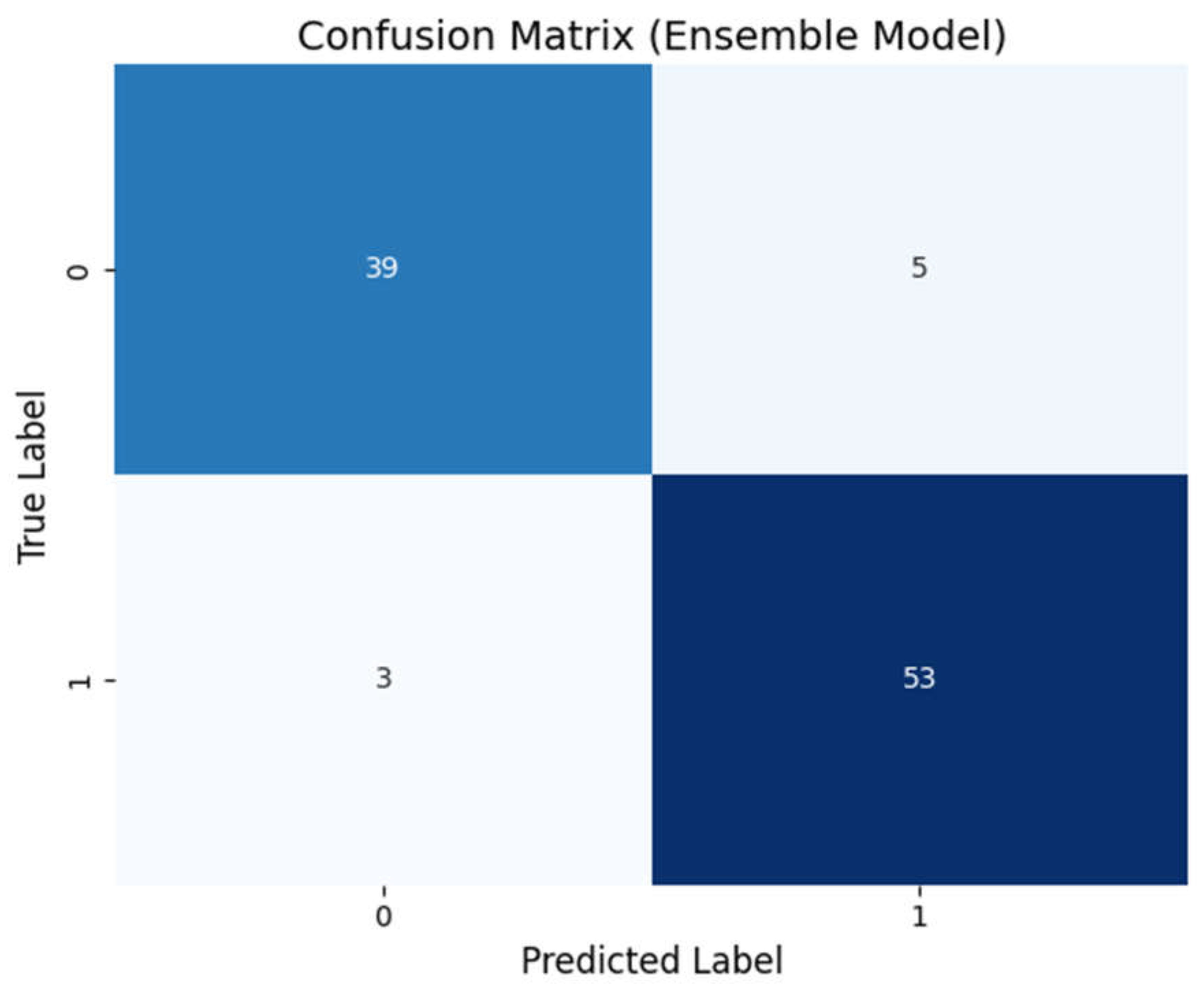

- Structure of a Confusion Matrix:

- Rows: Represent the true labels (e.g., whether the subject truly has BPD or not).

- Columns: Represent the predicted labels from the model.

- Key Observations:

- Diagonal Elements: These numbers indicate the correctly classified subjects (true positives for BPD and true negatives for controls).

-

Off-Diagonal Elements: These represent misclassifications (false positives and false negatives).In our example, a high count along the diagonal (e.g., 46 true positives and 47 true negatives) and very few off-diagonal entries suggest that the ensemble model is highly accurate.

-

Clinical Implication:A confusion matrix with minimal misclassifications means that the diagnostic tool would rarely miss a true case of BPD (low false negatives) and would rarely mistakenly label a healthy person as having BPD (low false positives). This balance is crucial in clinical settings to ensure both sensitivity and specificity.

-

Mathematical Aspect:The confusion matrix is a simple tabulation, but it underlies the computation of many key metrics such as precision and recall. For example, precision for the BPD class is calculated as:(7)

Section 4. Discussion

Section 4.1. Multidimensional Neural Signatures in BPD

Section 4.2. Advantages of the Machine Learning Approach

Section 4.3. Clinical and Translational Implications

Section 4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Section 4.5. Concluding Thoughts

Section 5. Conclusion

Section 6. Atachments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crowell, S.E.; Beauchaine, T.P.; Linehan, M.M. A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating the role of emotion dysregulation. Journal of Personality Disorders 2009, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Herpertz, S.C. The neurobiology of borderline personality disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 2007, 257, 192–199. [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsberg, H.W. Social cognition in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2002, 14, 106–117. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M.M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Montgomery, R.M. Augmenting Forensic Science Through AI: The Next Leap in Multidisciplinary Approaches. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, A.S.; Siever, L.J.; Li, S.C.; Koenigsberg, H.W. Neurobiology of borderline personality disorder: Implications for treatment. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 2008, 16, 174–182. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).