1. INTRODUCTION

Sickel cell disease is a genetically inherited blood disorder that affects the hemoglobin part of blood cells. It is characterized by the polymerization of sickle hemoglobin to form abnormally shaped erythrocytes, which leads to episodic acute illness, chronic anemia and progressive multi-organ damage (Ware RE et al 2017, Onimoe G and Rotz 2020) . Sickle cell anemia is increasingly recognized as having a serious global health burden, with current estimates exceeding 3 million affected births worldwide each year (Piel FB et al 2013).

Hydroxyurea is regarded as a primary disease modifying therapy for sickle cell disease with decades of evidence demonstrating the laboratory and clinical effects (Charache S et al 1995, Wang WC et al 2011). Hydroxyurea induces fetal hemoglobin, which inhibits erythrocyte sickling, but the drug also has beneficial effects on leukocytes, reticulocytes, and the endothelium. Hydroxyurea improves labs, reduces complications at maximum tolerated dose escalation (Ware RE 2010, McGann PT and Ware RE 2015). European trials found hydroxyurea's 15-20 mg/kg/day effective, providing lab and clinical benefits with minimal toxicity (Wang WC et al 2001, Ferster A et al 2001, Gulbis B 2005). In the U.S., trials often escalate hydroxyurea to 25-30 mg/kg/day, yielding significant lab and clinical benefits but potential toxic effects (Zimmerman SA et al 2004, Zimmerman SA et al 2007, Thornburg CD 2009).

Among the total SCD cases in Nepal, 58.3% are in the Tharu population, who make up only 6.6% of Nepal's total population. The condition poses enormous stress and financial burden on the parents of children with the disease who are usually the primary caregivers in most instances. It could therefore be speculated that SCD has the tendency to greatly deplete the finances of households in developing countries where there is high level of poverty and inequitable distribution of wealth and resources. Health care in most developing countries is mostly funded through out-of-pocket spending (OOPS).

Sickle cell anemia is particularly prevalent in the Tharu community of Nepal, where it poses a substantial health challenge. The disease's impact on this population underscores the need for culturally tailored healthcare interventions and increased awareness. Effective management strategies are crucial to improving health outcomes for affected individuals. The combination of medical treatment, patient education, and community support can help mitigate the adverse effects of sickle cell anemia and enhance the overall quality of life for those living with the disease (Charache S et al 1995; Wang WC et al 2011).

Hydroxyurea significantly reduces the frequency of pain, hospitalizations,transfusions, serious medical complications, and may improve quality of life. Incomplete Understanding of Optimal Hydroxyurea Dosing, Limited Accessibility and Affordability of Hydroxyurea, the financial burden associated with the management of SCD includes not only the cost of hydroxyurea but also expenses related to hospitalizations, emergency room visits, and supportive care, lack of a standardized policies regarding treatment cost. Addressing these challenges requires interdisciplinary research to establish evidence-based guidelines for hydroxyurea dosing in SCD, develop strategies to alleviate the financial burden associated with the disease and strength of HU prescribe with solution preparation. In this present study we want to determine Hydroxyurea Dose Escalation and financial burden of sickle cell disease patients.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Place

We conducted a Concurrent Mixed method design (Retrospective followed by prospective) study at Bheri Hospital situated at Nepalgunj district. There is large population of tharu people in the Nepalgunj who are prone to this disease and this hospital has a dedicated department for sickle cell patients.

2.2. Sample Size

Sample size was calculated by the following formula,

Where,

z = 1.96 (standard normal distribution value at 95% confidence level)

p = 4.5% (Marchand M et al 2017)

d = 5% (margin of error)

Assuming 20 % as non- response rate,

Hence minimum of 81 patients were included in this study.

2.3. Participants

Sickel cell disease patient who visited the study site were considered as the study population if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) Patients prescribed Hydroxyurea on fixed and escalated dose for at least 18 months (2) Patients who provide the informed consent.

2.4. Data Collection Tools:

The Data Collection Tool designed by the researcher was used to collect information from patients' cards. The tool was divided into the following parts.

Section I: Socio demographic information

Section II: Characteristics of Population at enrollment

Section III: Clinical and Laboratory events according to treatment groups

Section IV: Naranjo’s Causality Assessment Scale

Section V: Clinical Complications of Sickel cell anemia

Section VI: Other Information

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The ethical approval was taken from the Institution Review Committee of Pokhara University with reference number 77/2080/81. Written informed consent were obtained from the patient prior to their enrollment in the study

2.6. Data Analysis:

The data were entered in MS Excel and analyzed using IBM-SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and quantitative variables as means and standard deviation. Inferential analysis was performed according to nature of data. p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the patient

Among the total of 84 patients included, the majority were of age group between 21-40. Among the patients, 43 were male and 41 were female. (

Table 1)

3.2. Classification of Treatment Group

There were two groups of treatment one was fixed dose group and other was dose escalated group. The details of the two treatment groups are presented in the (

Table 2).

3.3. Laboratory Values of the Patients

The median value of Hbs was found to be 69.200 with maximum 79 and minimum 49 in the patients of the sickle cell disease. The change in the laboratory values of the patients in different times is tabulated below. While observing the different variables it was observed that the hemoglobin and fetal hemoglobin is in increasing manner while reticulocyte count, neutrophil and platelets are slightly decreased over the period of 6 months. There was no defining change in the lab parameter of mean corpuscular volume.

Table 3.

Different Lab Value levels in the study participants.

Table 3.

Different Lab Value levels in the study participants.

| Variable |

0 Month |

3 Month |

6 Month |

| Hemoglobin level g/dl |

7.974±0.125 |

8.294±0.388 |

8.46±0.626 |

| Fetal hemoglobin level % |

21.27±1.593 |

22.19±4.406 |

23.21±7.404 |

| Mean corpuscular volume fl |

92.757±0.553 |

92.842±1.503 |

92.167±3.845 |

| Absolute reticulocyte count ×10−9/liter |

229.49±6.222 |

220.40±22.811 |

209.01±41.240 |

| Absolute neutrophil count ×10−9/liter |

4.276±0.138 |

4.255±0.507 |

4.132±0.990 |

| Platelets |

404.06±9.506 |

405.26±18.213 |

403.92±29.913 |

3.4. Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR)

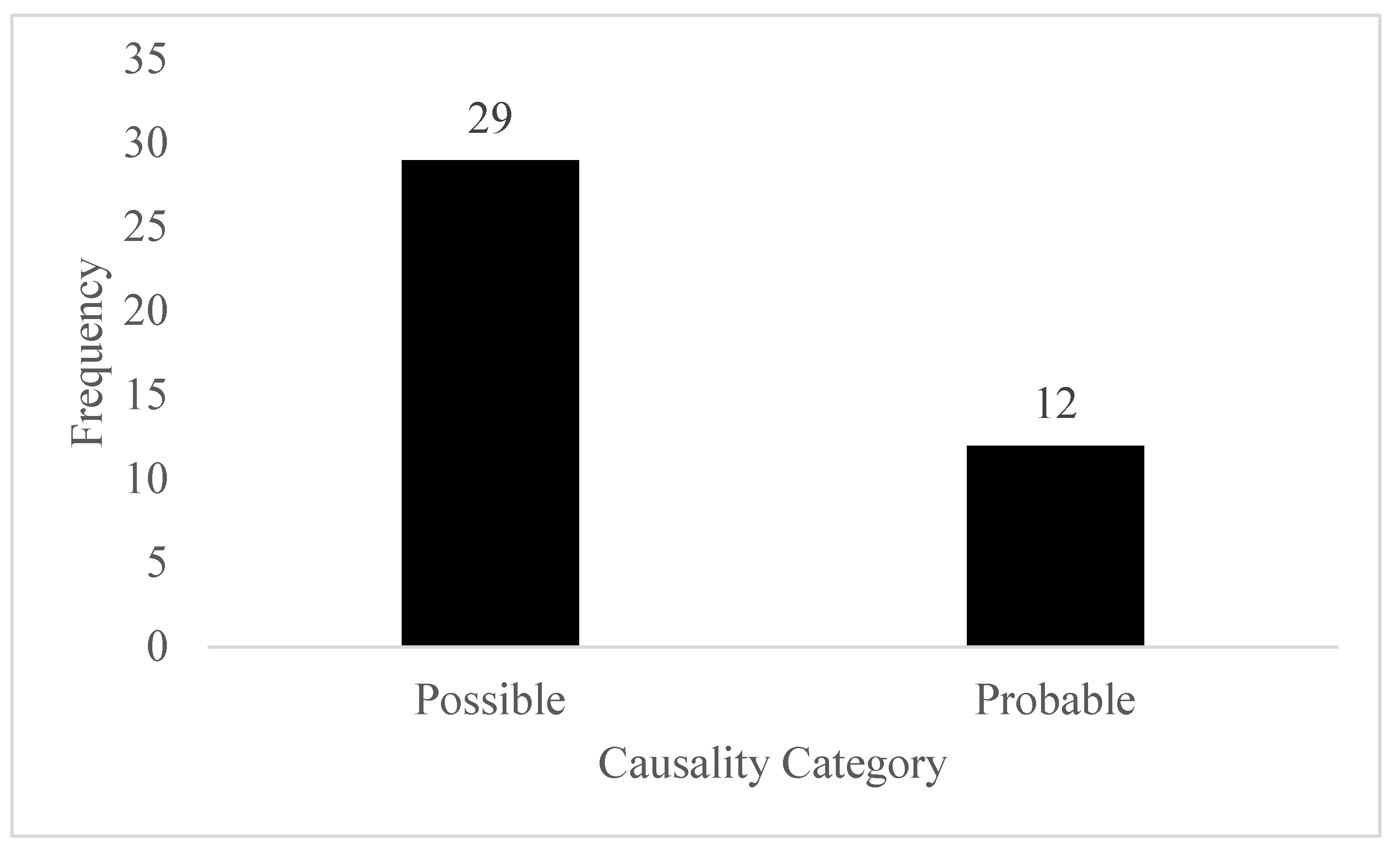

A total of 41 suspected ADRs were observed during the study period. Highest number of ADR was observed in the fixed dose group. Infection was observed in the total of 22 patients. Upon performing the causality assessment, 29 ADR falls under the possible category while remaining 12 falls under the probable category.

Table 4.

ADR and its description.

Table 4.

ADR and its description.

| Treatment Group |

Type of ADR |

Total |

| Anemia |

Infection |

Vitamin D deficiency |

| Fixed Dose |

4 |

14 |

9 |

27 |

| Escalated Dose |

2 |

8 |

4 |

14 |

| Total |

6 |

22 |

13 |

41 |

Figure 1.

Category of ADR.

Figure 1.

Category of ADR.

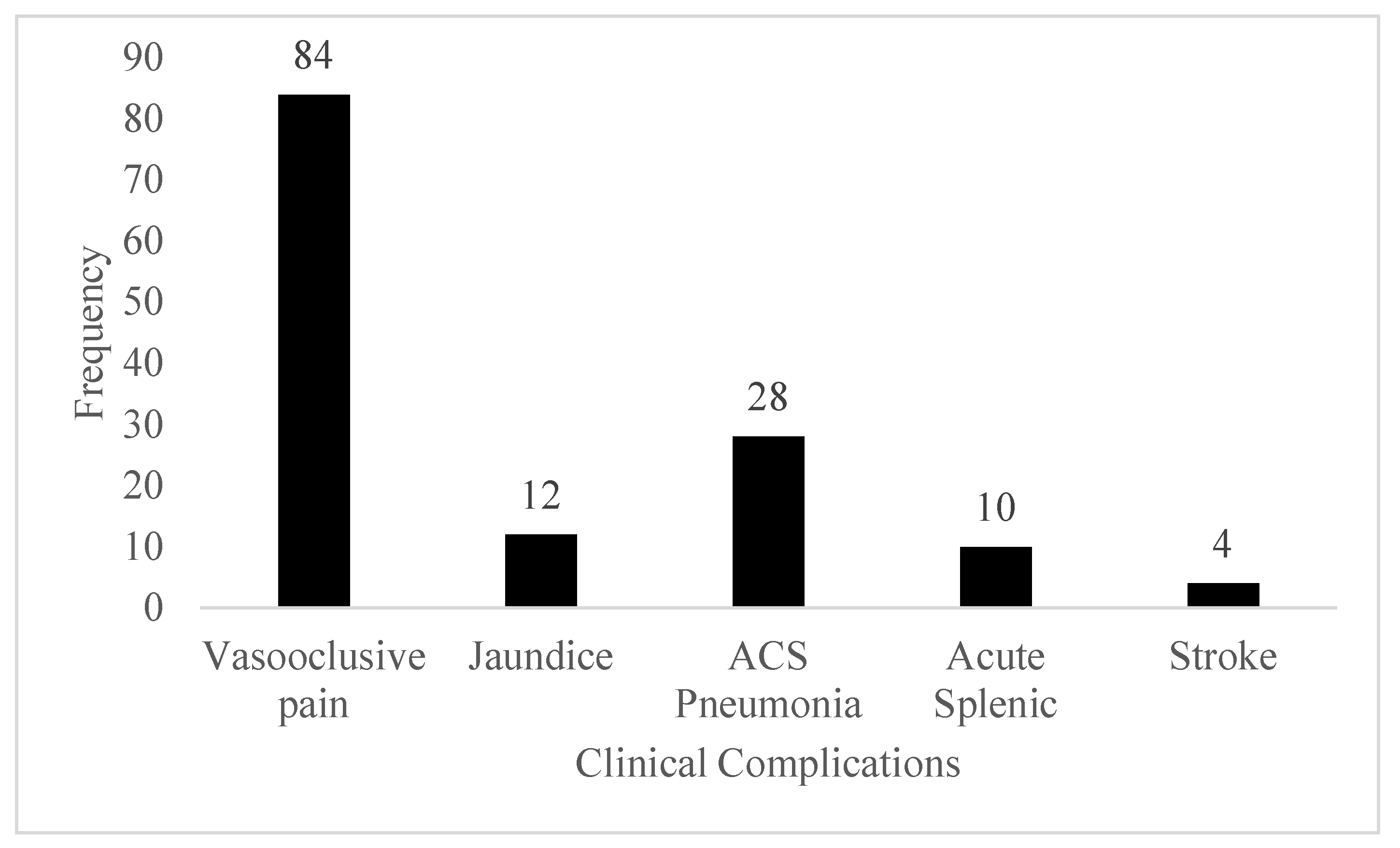

3.5. Clinical Complications

In this study, it was identified that all patients has vasooclusive pain. The lowest complications was found to be stroke.

Figure 2.

Clinical Complications of SCD.

Figure 2.

Clinical Complications of SCD.

3.6. Drugs Used in SCD

Besides the use of hydroxyurea in all patients the other medicines were also found to be used in the treatment procedure which are tabulated as shown below. Folic acid was used in higher number of patients while tapentadol was used in few patients.

Table 5.

Drugs Used in SCD.

Table 5.

Drugs Used in SCD.

| Drugs |

Frequency |

| Folic Acid |

70 |

| Iron + Folic acid |

14 |

| Paracetamol |

32 |

| Ketorolac |

59 |

| Tramadol + Paracetamol |

22 |

| Naproxen |

4 |

| Etoricoxib |

12 |

| Heparin |

11 |

| Deferasirox |

6 |

| Meningococal (for prophylaxis) |

15 |

| Influenza (for prophylaxis) |

21 |

| PCV (for prophylaxis) |

45 |

| Tapentadol |

2 |

| Morphine |

30 |

3.7. Laboratory Dose limit toxic Effects

While observing the laboratory values of the respondents we observe that there is occurrence of dose limitation toxic effects. The more toxic effects is observed in the escalated dose consisting of neutropenia as the major toxic effects. Anemia was observed as the highest toxic effects while observing in the both treatment groups

Table 6.

Toxic Effects of Treatment Groups.

Table 6.

Toxic Effects of Treatment Groups.

| Treatment Group |

Type of Toxic effects |

Total |

| Anemia |

Reticulocytopenia |

Neutropenia |

Thrombocytopenia |

| Fixed Dose |

12 |

8 |

0 |

6 |

26 |

| Escalated Dose |

9 |

10 |

16 |

9 |

44 |

| Total |

21 |

18 |

16 |

15 |

70 |

3.8. Cost Details

The cost was observed there is a high cost in the Drug usage of the patient. The low cost accounts for the surgery or transfusion process to the person.

Table 7.

Category of Cost.

Table 7.

Category of Cost.

| Items |

For SCD |

Comorbidity |

| Cost (in NRs.) |

Cost (in NRs.) |

| Direct Medical Cost |

|

| Laboratory Costs |

10479.762 ± 2382.100 |

2989.130 ± 983.244 |

| Drug Usage Cost |

27440.476 ± 7613.955 |

4647.92 ± 2423.29 |

| Admission Cost |

5742.373 ± 5923.309 |

2662.069 ± 684.217 |

| Consumables |

1828.571 ± 593.380 |

1333.33 ± 516.398 |

| Surgery plus Transfusion |

833.33 ± 1033.573 |

285.714 ± 1036.34 |

| Non-Medical Cost |

|

| Transportation |

6673.81 ± 2799.317 |

4. DISCUSSION

Our study revealed several key sociodemographic and clinical characteristics among Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) patients. Most patients reported an annual family income exceeding NRs. 100,000, indicating a moderate socioeconomic status compared to other regions where poverty often exacerbates SCD burden (Kauf et al., 2009). This socioeconomic profile might influence access to healthcare services and adherence to treatment regimens, impacting disease management outcomes (Grosse et al., 2011).

In our study, two treatment groups were evaluated: a fixed-dose group and a dose-escalated group for hydroxyurea administration in SCD patients. Initially, the most common dose in the escalated group was 500 mg once daily (OD), followed by 500 mg twice daily (BD). Upon further dose escalation, the common regimen shifted to 500 mg BD and, subsequently, 1000 mg OD. These findings reflect a tailored approach to hydroxyurea dosing, aiming to optimize therapeutic benefits while minimizing adverse effects. This strategy aligns with international recommendations advocating for dose escalation based on patient response and tolerance (Steinberg et al., 2010). However, our study’s dosing variations are somewhat distinct from those reported in high-income countries, where hydroxyurea is often initiated at a lower dose and escalated more cautiously (Wang et al., 2011). This discrepancy could be due to differences in baseline patient characteristics, genetic factors, and healthcare infrastructure. For example, in regions with better healthcare access, more frequent monitoring allows for more gradual dose adjustments to ensure safety and efficacy (Charache et al., 1995). The choice of dosing regimens also reflects the practical challenges in Nepal, where limited healthcare resources necessitate simpler and more feasible dosing strategies. The preference for 500 mg OD or BD may be influenced by factors such as patient adherence, ease of administration, and availability of drug formulations (Ware et al., 2017).

During the study period, we observed a total of 41 suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) among SCD patients, with the highest number of ADRs occurring in the fixed-dose hydroxyurea group. Infections were the most common ADR, affecting 22 patients. Causality assessment categorized 29 ADRs as possible and 12 as probable. Our findings align with previous studies indicating that hydroxyurea is generally well-tolerated but can be associated with an increased risk of infections due to its myelosuppressive effects (Wang et al., 2011). The higher incidence of ADRs in the fixed-dose group may be due to suboptimal dosing, where patients might not receive the individualized titration needed to balance efficacy and safety (Steinberg et al., 2010). This is consistent with studies suggesting that fixed-dose regimens can lead to either underdosing or overdosing, thereby increasing the risk of ADRs (Charache et al., 1995). Contrastingly, the variable response to hydroxyurea and the higher ADR rates in our study could be influenced by genetic and environmental factors unique to the Nepalese population. Studies in African and Middle Eastern populations have also reported variability in ADR profiles, suggesting that genetic polymorphisms affecting drug metabolism and immune response could play a significant role (Pandey et al., 2016; Ware et al., 2017).

Our study found that vaso-occlusive pain was the most prevalent complication among SCD patients, followed by acute chest syndrome (ACS) and pneumonia, with stroke being the least common. These findings align with global patterns where vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) are the hallmark of SCD, leading to significant morbidity (Platt et al., 1991). However, the incidence of stroke was notably low, contrasting with studies in high-income countries where stroke is a more common complication due to better detection and monitoring systems (DeBaun & Kirkham, 2016). The addition of folic acid and tapentadol in some patients further underscores the comprehensive approach to managing SCD-related pain and preventing folate deficiency due to increased erythropoiesis (Ballas et al., 2012). The lower incidence of stroke in our study could be due to the shorter lifespan and limited healthcare access, leading to underdiagnosis and underreporting, unlike in high-resource settings where routine transcranial Doppler screenings help in early detection and prevention (Adams et al., 1998). Moreover, the reliance on hydroxyurea alone might not be sufficient to prevent all complications, indicating a need for more integrated care strategies and better healthcare infrastructure. While hydroxyurea remains the cornerstone of SCD management in Lumbini Province, addressing the variations in complication rates and improving diagnostic capabilities are essential for optimizing patient outcomes. This aligns with global recommendations for comprehensive care and monitoring to manage the multifaceted challenges of SCD effectively (Ware et al., 2017).

The median value of hemoglobin (Hb) in our study was 69.200 g/L, with a range of 49 to 79 g/L, reflecting the severe anemia characteristic of Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) patients in Lumbini Province. Over six months, Hb and fetal hemoglobin (HbF) levels showed a significant increase, while reticulocyte count, neutrophil count, and platelet count decreased slightly. These findings align with global studies demonstrating the efficacy of hydroxyurea in increasing Hb and HbF levels and reducing markers of hemolysis and inflammation (Wang et al., 2011; Charache et al., 1995). The lack of significant change in mean corpuscular volume (MCV) contrasts with studies in high-income settings, where MCV often increases markedly (Steinberg et al., 2010). This variation could be attributed to differences in baseline nutritional status, genetic factors, or adherence to hydroxyurea therapy. For instance, a study by Pandey et al. (2016) in India reported similar increases in Hb and HbF but also noted significant increases in MCV, suggesting regional differences in response to hydroxyurea. Overall, the observed improvements in hematologic parameters underscore the benefits of hydroxyurea in SCD management, even in resource-limited settings. However, the variability in MCV changes highlights the need for region-specific studies to understand fully the local factors influencing treatment outcomes (McGann et al., 2016).

The financial burden was found to be substantial, with direct medical costs averaging NRs. 58,300 and non-medical costs averaging NRs. 6,673 per patient. Drug usage constituted the highest portion of medical costs, amounting to NRs. 27,440.476 ± 7,613.955 (1USD =~130NRs.) This financial strain is exacerbated by the limited government support, which provides only NRs. 100,000 over a patient's lifetime for SCD management. These findings align with global research that highlights the significant economic burden of SCD on patients and their families. For instance, a study by Kauf et al. (2009) in the United States reported that annual direct medical costs for SCD patients can exceed $10,000, with medication costs being a major contributor. Similarly, in Nigeria, Ambrose et al. (2018) found that the high cost of medications and frequent hospitalizations placed a significant financial strain on families. The discrepancy between the financial support provided by the Nepalese government and the actual costs incurred by patients underscores the inadequacy of current healthcare funding policies. In high-income countries, comprehensive insurance coverage and government support significantly mitigate the financial burden on SCD patients. In low-resource settings like Nepal, limited healthcare funding and lack of insurance coverage leave many families struggling to afford essential treatments. The NRs. 100,000 lifetime support from the Nepalese government is insufficient when compared to the cumulative costs of managing SCD, which can far exceed this amount within a few years of treatment. Our findings highlight the urgent need for enhanced financial support and comprehensive healthcare policies to alleviate the economic burden on SCD patients in Nepal. Increasing government funding, expanding insurance coverage, and implementing cost-effective treatment protocols could significantly improve the quality of life for SCD patients. These measures are crucial for ensuring equitable access to essential healthcare services and reducing the financial hardship associated with chronic diseases like SCD (Ware et al., 2017).

In our study we found that healthcare facilities provided only 500 mg capsules of Hydroxyurea for the treatment of SCD. This limited availability necessitated patients or caregivers to prepare a 100 mg/ml solution at home by dissolving one capsule in 5 ml of water for escalated dosing needs. This practice reflects a common challenge in resource-constrained settings where healthcare infrastructure may not adequately meet the diverse dosing requirements of patients (McGann et al., 2016). Contrastingly, studies in high-income countries typically have a wider range of pharmaceutical formulations and dosing options readily available in healthcare settings, allowing for more precise and convenient administration of medications (Wang et al., 2011). This disparity underscores the importance of equitable access to healthcare resources and pharmaceutical products tailored to patient needs, particularly in managing chronic conditions like SCD (Ware et al., 2017). The variability in medication availability and preparation methods across different regions can influence treatment adherence, efficacy, and safety outcomes. Improving access to standardized pharmaceutical formulations and promoting regulatory measures for drug availability are crucial steps towards optimizing SCD management globally (Ballas et al., 2012).

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader SCD population in Nepal. The self-preparation of hydroxyurea solutions by patients or caregivers introduces variability that may affect treatment adherence and outcomes.

5. CONCLUSION

In summary it is revealed that Hydroxyurea dosing patterns highlighted the necessity for individualized treatment plans, while the study also underscored the considerable financial strain on patients, exacerbated by limited government support. Despite the effectiveness of hydroxyurea in improving hematologic parameters and managing complications, the limited availability of varied dosages posed significant challenges. The Nepalese government should increase financial aid for SCD patients beyond the current lifetime support of NRs. 100,000 to adequately cover the substantial medical costs. Government should implement protocols for personalized hydroxyurea dosing to optimize therapeutic outcomes and minimize adverse drug reactions. Establishing a comprehensive monitoring and pharmacovigilance systems to track patient responses and adverse reactions to hydroxyurea is a necessity.

References

- Charache, S.; Terrin, M. L.; Moore, R. D.; Dover, G. J.; Barton, F. B.; Eckert, S. V.; Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. New England Journal of Medicine 1995, 332, 1317–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferster, A.; Tahriri, P.; Vermylen, C.; Sturbois, G.; Corazza, F.; Fondu, P.; Godeau, B. Five years of experience with hydroxyurea in children and young adults with sickle cell disease. Blood 2001, 97, 3628–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosse, S. D.; Odame, I.; Atrash, H. K.; Amendah, D. D.; Piel, F. B.; Williams, T. N. Sickle cell disease in Africa: a neglected cause of early childhood mortality. American journal of preventive medicine 2011, 41, S398–S405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulbis, B. Hydroxyurea for sickle cell disease in children and for prevention of cerebrovascular events: the Belgian experience. Blood 2005, 105, 2685–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchand, M.; Gill, C.; Malhotra, A. K.; Bell, C.; Busto, E.; McKeown, M. D.; Cherukupalli, A.; Yeo, J.; Arnold, B.; Kapoor, V. The assessment and sustainable management of sickle cell disease in the indigenous Tharu population of Nepal. Hemoglobin 2017, 41(4-6), 278-282.

- McGann, P. T.; Ware, R. E. Hydroxyurea therapy for sickle cell anemia. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety 2015, 14, 1749–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onimoe, G.; Rotz, S. Sickle cell disease: A primary care update. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2020, 87, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pande, R.; Ghimire, P. G.; Chand, P. B.; Gupta, S. Sickle cell disease in Western Nepal. Nepal Journal of Medical Sciences 2019, 4, 15–19 https://wwwnepjolinfo/indexphp/NJMS/article/view/24121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Shrestha, N. Sickle cell anaemia among Tharu population visiting the outpatient department of general medicine of a secondary care centre: A descriptive cross-sectional study. JNMA: Journal of the Nepal Medical Association 2022, 60, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piel, F. B.; Patil, A. P.; Howes, R. E.; Nyangiri, O. A.; Gething, P. W.; Dewi, M.; Hay, S. I. Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: a contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. The Lancet 2013, 381, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornburg, C. D.; Dixon, N.; Burgett, S.; Mortier, N. A.; Schultz, W. H.; Zimmerman, S. A.; et al. A pilot study of hydroxyurea to prevent chronic organ damage in young children with sickle cell anemia. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2009, 52, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang WC, Wynn LW, Rogers ZR, Scott JP, Lane PA, & Ware RE. A two-year pilot trial of hydroxyurea in very young children with sickle-cell anemia. Journal of Pediatrics 2001, 139, 790–796. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. C.; Ware, R. E.; Miller, S. T.; Iyer, R. V.; Casella, J. F.; Minniti, C. P.; Thompson, B. W. Hydroxycarbamide in very young children with sickle-cell anaemia: a multicentre, randomised, controlled trial (BABY HUG). The Lancet 2011, 377, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, R. E. How I use hydroxyurea to treat young patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood 2010, 115, 5300–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, R. E. Optimizing hydroxyurea therapy for sickle cell anemia. Hematology: American Society of Hematology Education Program 2015, 2015, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, R. E.; de Montalembert, M.; Tshilolo, L.; Abboud, M. R. Sickle cell disease. The Lancet 2017, 390, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, S. A.; Schultz, W. H.; Burgett, S.; Mortier, N. A.; Ware, R. E. (2007). Hydroxyurea therapy lowers transcranial Doppler flow velocities in children with sickle cell.

- Zimmerman, S. A.; Schultz, W. H.; Davis, J. S.; Pickens, C. V.; Mortier, N. A.; Howard, T. A.; Mentzer, R. C. Sustained long-term hematologic efficacy of hydroxyurea at maximum tolerated dose in children with sickle cell disease. Blood 2004, 103, 2039–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Respondents.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Respondents.

| Sociodemographic Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Sex |

| Male |

43 |

50.6 |

| Female |

41 |

50.6 |

| Age Group |

| Less than 20 |

35 |

41.2 |

| 21-40 |

43 |

50.6 |

| 41-60 |

6 |

7.1 |

| Income (Annual NRs.) (1 USD=~135 NRs.) |

| < 25000 |

20 |

23.5 |

| 25000-50000 |

16 |

18.8 |

| 50000-100000 |

15 |

17.6 |

| >100000 |

33 |

38.8 |

Table 2.

Treatment group of SCD.

Table 2.

Treatment group of SCD.

| Treatment group |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| Fixed Dose |

36 |

42.9 |

| Dose Escalated |

|

|

| 250 mg OD |

4 |

4.8 |

| 350 mg OD |

2 |

2.4 |

| 500 mg OD |

30 |

35.7 |

| 500 mg BD |

12 |

14.3 |

| Total |

84 |

100 |

| If the second dose was escalated then the following dose escalation parameters were observed |

| Dose Escalated |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| 500 mg OD |

4 |

4.8 |

| 500 mg BD |

24 |

28.6 |

| 750 mg BD |

5 |

6.0 |

| 1000 mg OD |

8 |

9.5 |

| 1000 mg BD |

7 |

8.3 |

| Total |

48 |

100 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).