Submitted:

23 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Labelled Random Finite Sets

2.1.1. Bernoulli RFS

2.1.2. Multi-Bernoulli RFS

2.1.3. Labelled Multi-Bernoulli RFS

2.2. Generalised Labelled Multi-Bernoulli RFS

2.3. Bayesian multi-target filtering

2.4. Measurement Likelihood Function

2.5. Delta-Generalized Labeled Multi-Bernoulli

2.6. N-Scan GM-PHD filter

3. Proposed Methods

3.1. Uncertainty Effects on -GLMB

3.2. N-Scan -GLMB

3.2.1. Initialization

3.2.2. Prediction

3.2.3. Update

3.2.4. Pruning and Extraction

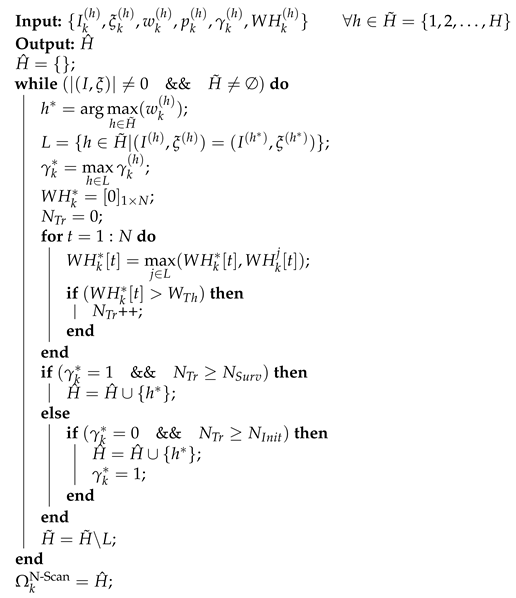

| Algorithm 1:Summary of N-Scan pruning algorithm. |

|

3.3. Enhanced Update phase

3.4. Enhanced Predict phase

3.5. Refined -GLMB

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

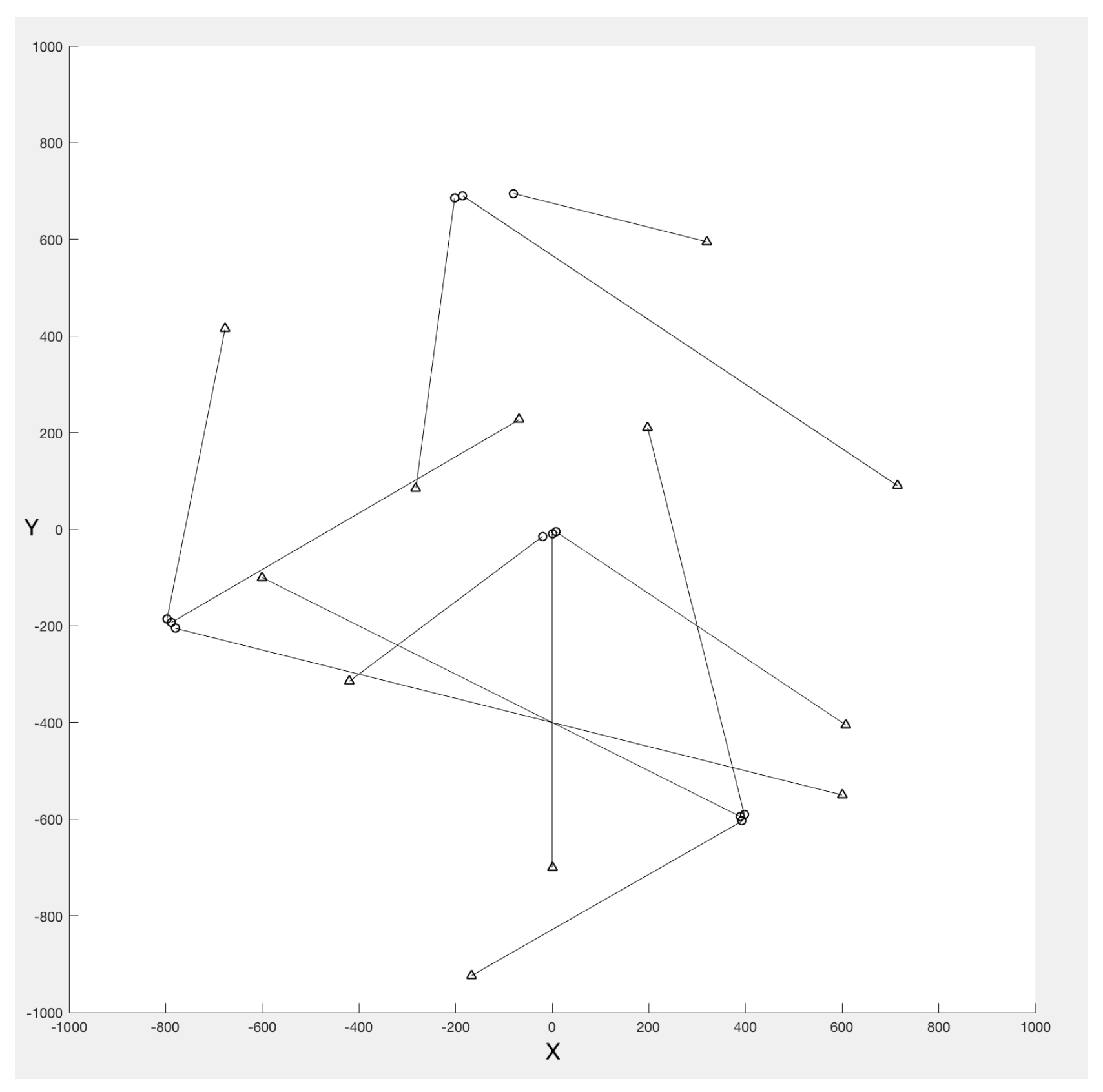

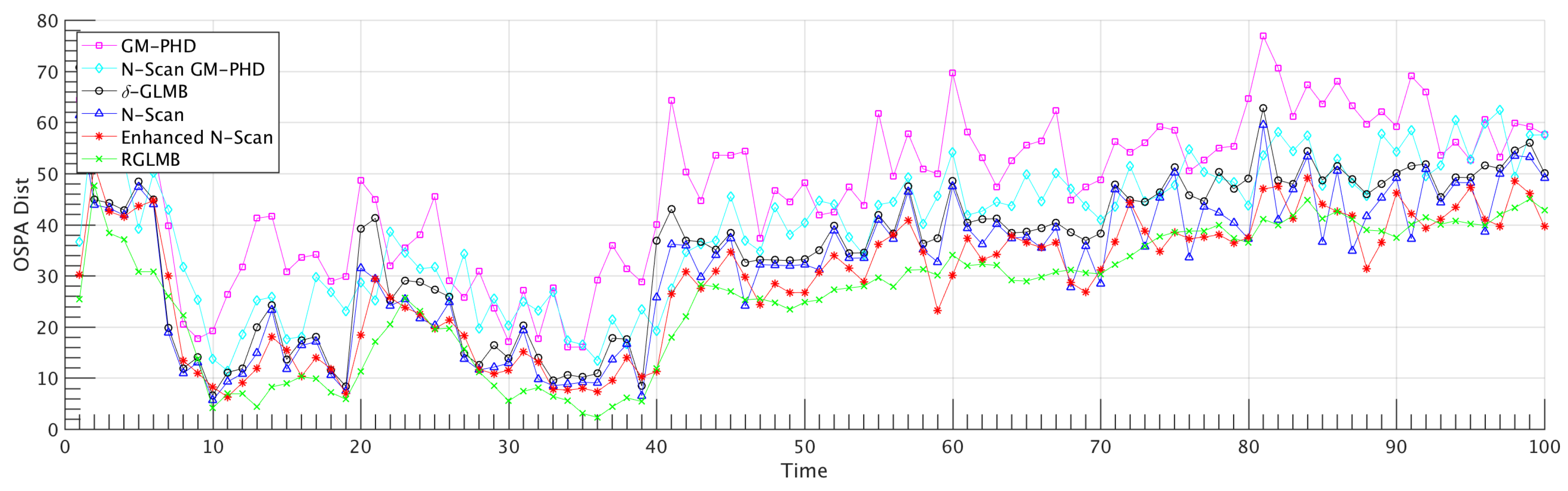

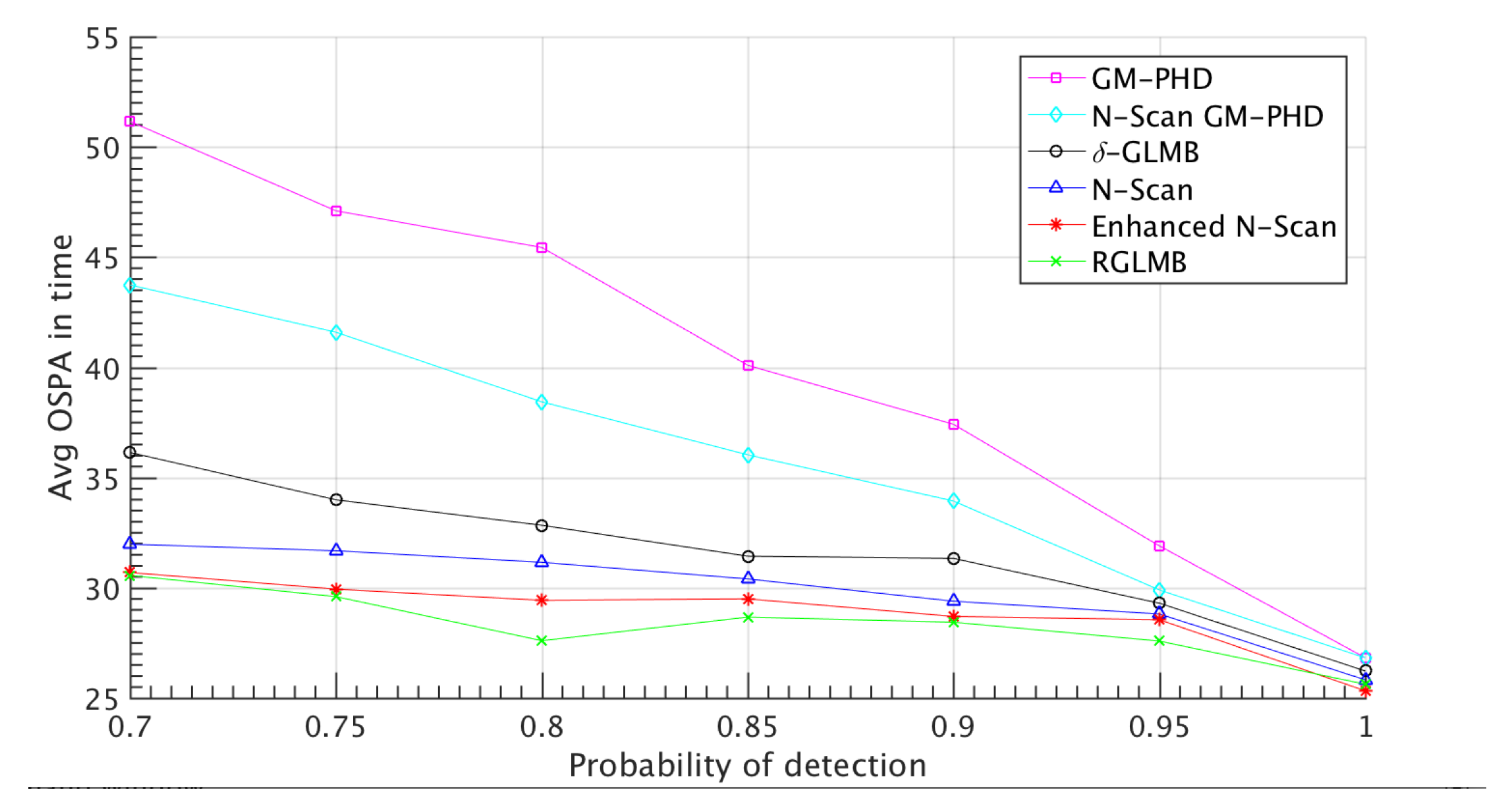

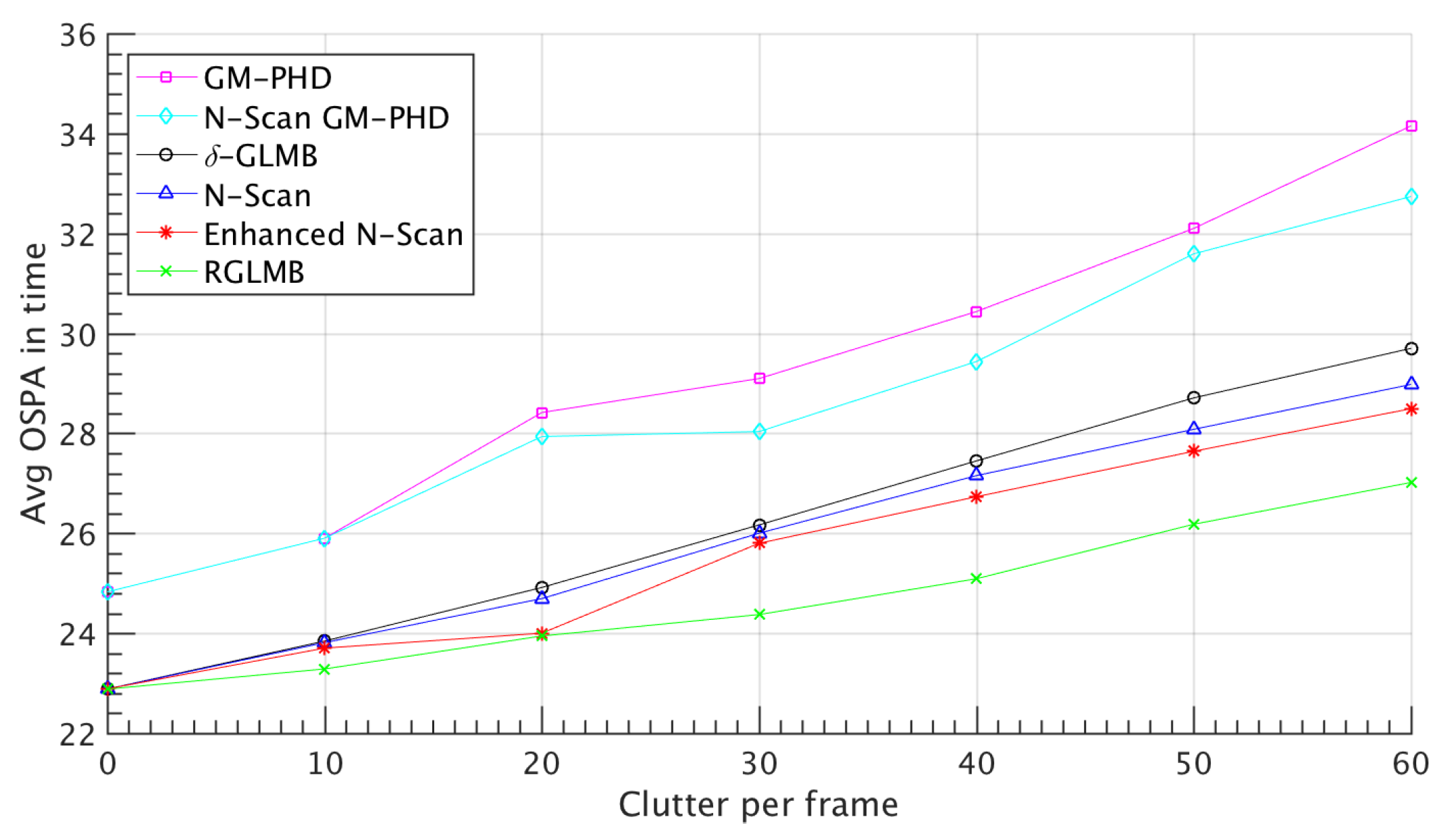

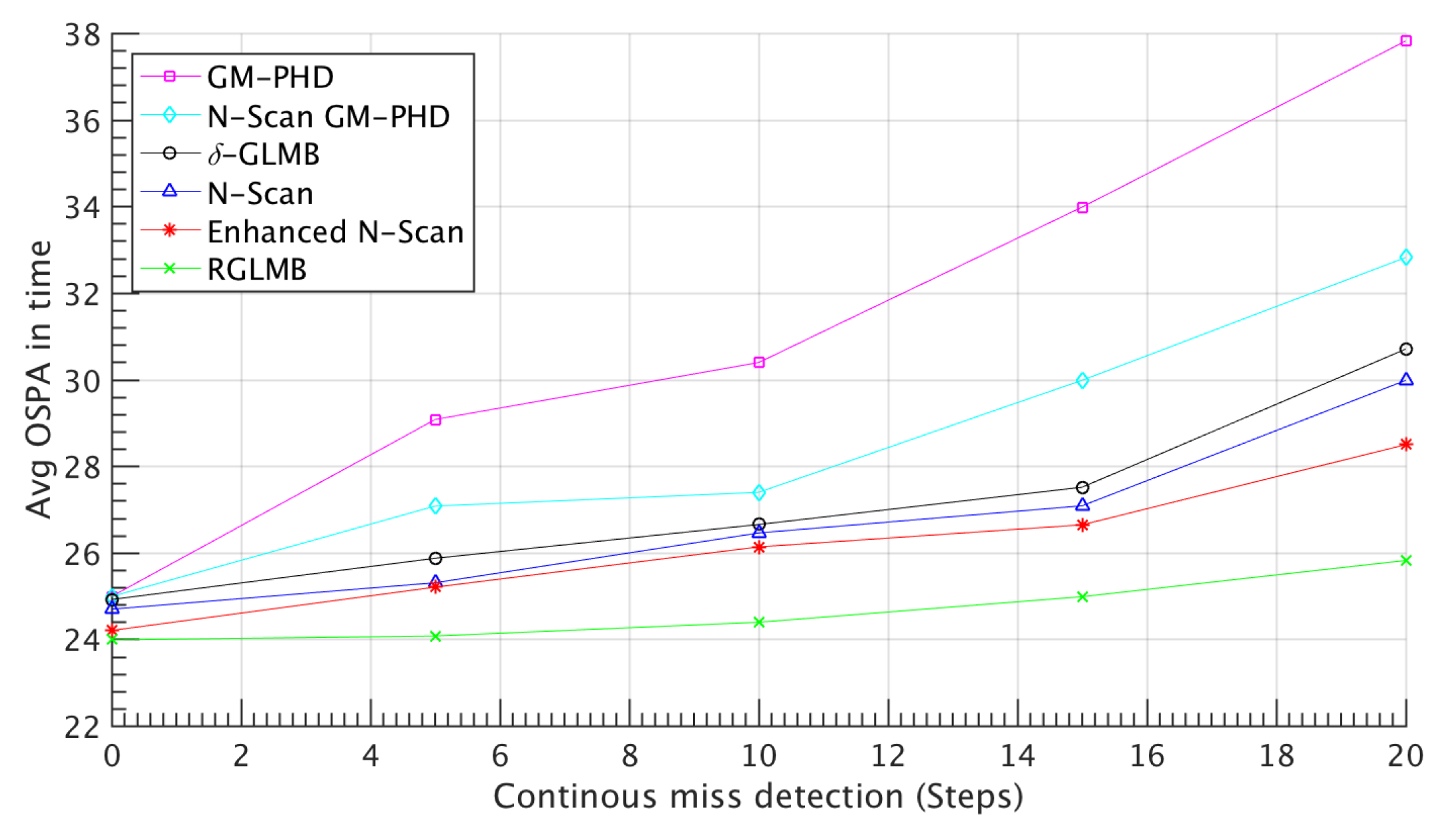

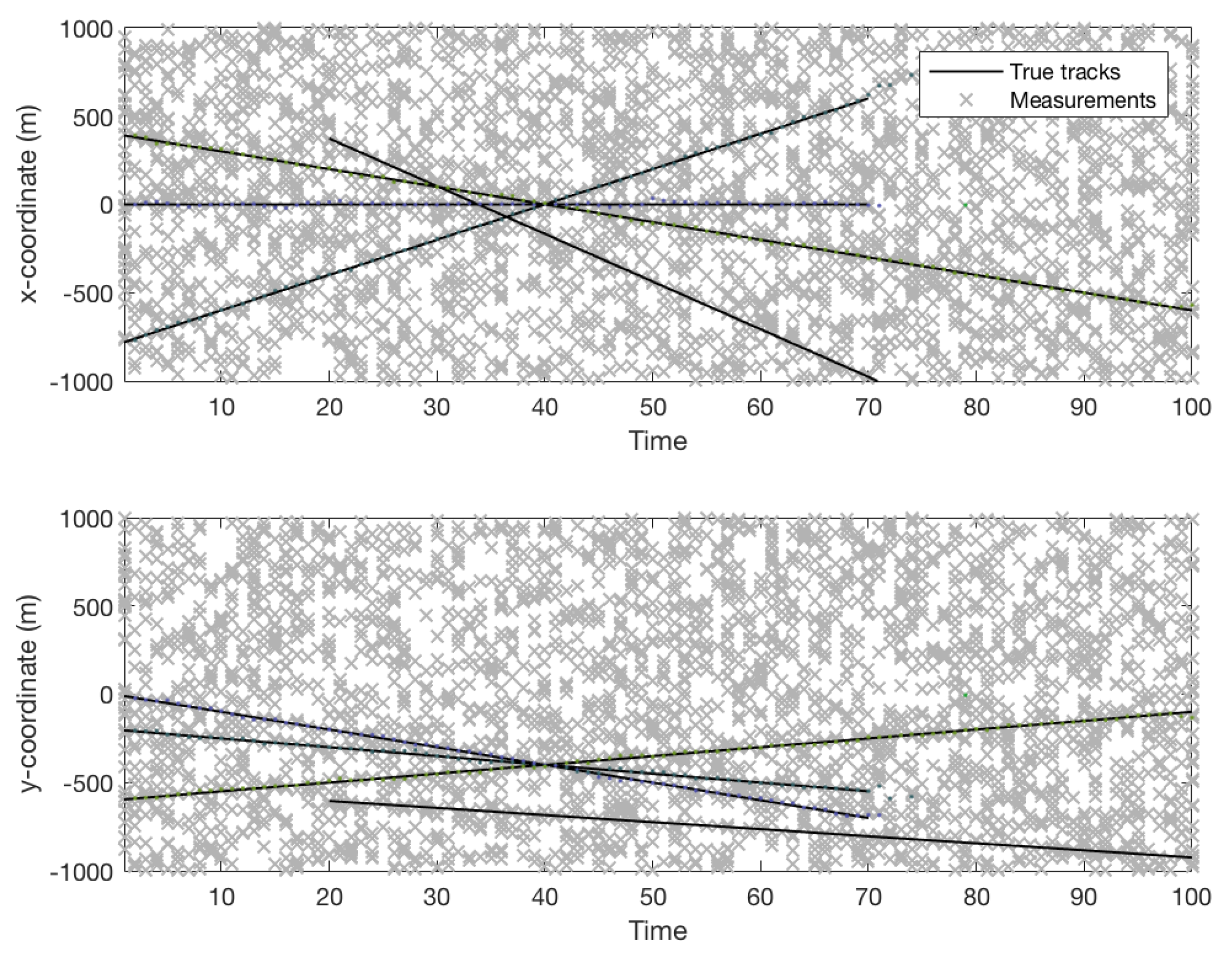

4.1. Simulated Dataset Results

| Method() | OSPA(AVG)(# of targets) |

|---|---|

| GM-PHD | 47.46(5.17) |

| N-Scan GM-PHD | 39.71(5.88) |

| -GLMB | 33.4375(6.13) |

| N-scan -GLMB | 31.1589(6.71) |

| Enhanced N-scan -GLMB | 29.4330(6.94) |

| Refined N-scan -GLMB | 27.0017(7.26) |

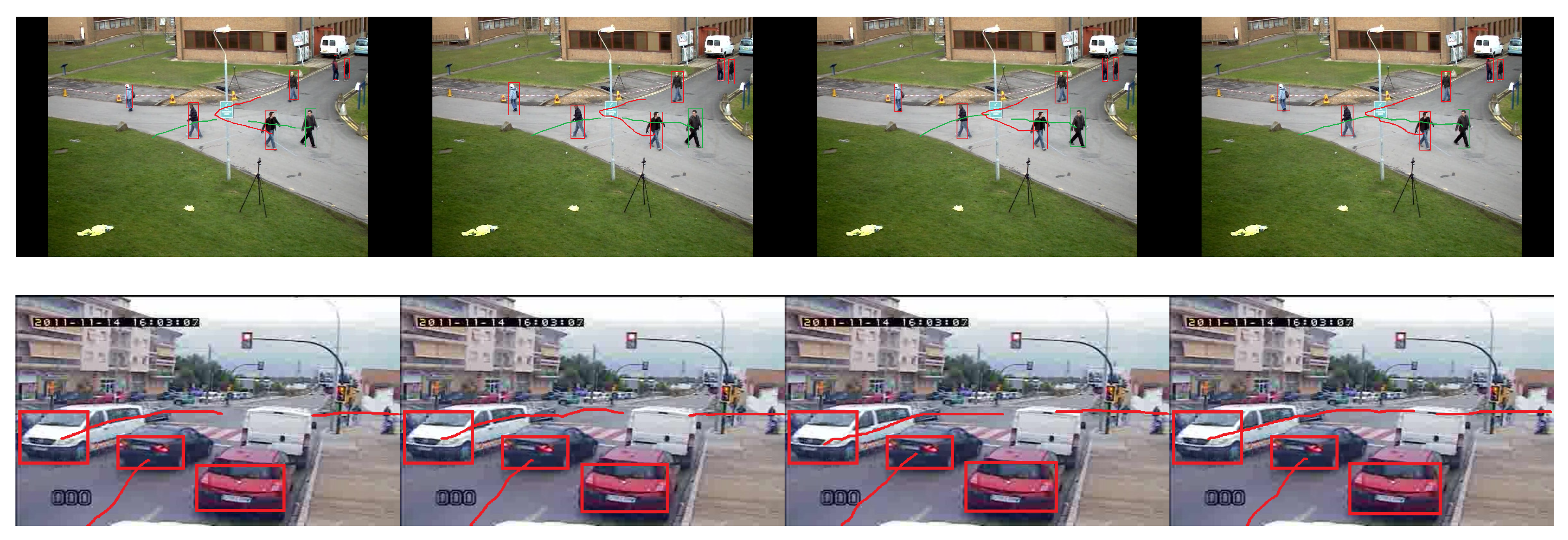

4.2. Visual Dataset Results

| Method | MOTA | MOTP | ReR | FAR | MTR | MOR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM-PHD | 42.62 | 54.02 | 0.45 | 0.12 | 0.57 | 0.71 |

| N-Scan GM-PHD | 46.78 | 58.49 | 0.51 | 0.10 | 0.46 | 0.57 |

| -GLMB | 51.05 | 63.62 | 0.57 | 0.10 | 0.42 | 0.64 |

| N-scan -GLMB | 54.53 | 65.28 | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.42 |

| Enhanced N-scan -GLMB | 55.60 | 65.91 | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.35 |

| Refined N-scan -GLMB | 56.79 | 66.38 | 0.71 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| Method | MOTA | MOTP | ReR | FAR | MTR | MOR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM-PHD | 27.91 | 32.59 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.68 | 0.78 |

| N-Scan GM-PHD | 31.20 | 36.17 | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.56 | 0.66 |

| -GLMB | 30.83 | 37.55 | 0.48 | 0.14 | 0.53 | 0.64 |

| N-scan -GLMB | 35.41 | 40.06 | 0.58 | 0.07 | 0.46 | 0.56 |

| Enhanced N-scan -GLMB | 36.26 | 41.74 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.53 |

| Refined N-scan -GLMB | 39.32 | 43.45 | 0.68 | 0.04 | 0.34 | 0.43 |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Supplementary Background

Appendix B. The L 1 -Error of N-Scan Method and Traditional Method of Discarding

References

- Bar, S.Y.; Fortmann, T. Tracking and data association. PhD thesis, Academic Press Cambridge, 1988.

- Blackman, S.; Popoli, R. Design and Analysis of Modern Tracking Systems (Artech House Radar Library). Artech house 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Alhadhrami, E.; Seghrouchni, A.E.F.; Barbaresco, F.; Zitar, R.A. Testing Different Multi-Target/Multi-Sensor Drone Tracking Methods Under Complex Environment. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Radar Symposium (IRS). IEEE; 2024; pp. 352–357. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Wang, T.; Han, Y.; Wei, T. Multi-Target Tracking for Satellite Videos Guided by Spatial-Temporal Proximity and Topological Relationships. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, D.; Wang, J.; Tong, D.; Zhao, R.; Ma, Z.; Li, J.; Song, B. Continuous multi-target tracking across disjoint camera views for field transport productivity analysis. Automation in Construction 2025, 171, 105984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S.; Vo, B.T.; Vo, B.N.; Dietmayer, K. The Labeled Multi-Bernoulli Filter. IEEE Trans. Signal Processing 2014, 62, 3246–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, S.S. Multiple hypothesis tracking for multiple target tracking. IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine 2004, 19, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yan, T.; Shen, J.; Sun, G.; Tian, Z.; Ju, W. Multi-Hypothesis Tracking Algorithm for Missile Group Targets. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS). IEEE; 2024; pp. 745–750. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Nie, H.; Liu, Y.; Bian, C. Robust Tracking Method for Small and Weak Multiple Targets Under Dynamic Interference Based on Q-IMM-MHT. Sensors 2025, 25, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortmann, T.; Bar-Shalom, Y.; Scheffe, M. Sonar tracking of multiple targets using joint probabilistic data association. IEEE journal of Oceanic Engineering 1983, 8, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, P.; Wei, H. An algorithm for multi-target tracking in low-signal-to-clutter-ratio underwater acoustic scenes. AIP Advances 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Cheng, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y. Robust Visual Localization System With HD Map Based on Joint Probabilistic Data Association. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, R. Random set theory for target tracking and identification, 2001.

- Daley, D.J.; Vere-Jones, D. An introduction to the theory of point processes: volume II: general theory and structure; Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- Forti, N.; Millefiori, L.M.; Braca, P.; Willett, P. Random finite set tracking for anomaly detection in the presence of clutter. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Radar Conference (RadarConf20). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.; Qi, B.; Wang, P.; Di, R.; Zhang, W. Novel Multi-Target Tracking Based on Poisson Multi-Bernoulli Mixture Filter for High-Clutter Maritime Communications. In Proceedings of the 2024 12th International Conference on Information Systems and Computing Technology (ISCTech). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Si, W.; Wang, L.; Qu, Z. Multi-target tracking using an improved Gaussian mixture CPHD Filter. Sensors 2016, 16, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Bao, Q.; Pan, J. Multi-target Tracking Method of Non-cooperative Bistatic Radar System Based on Improved PHD Filter. In Proceedings of the 2024 Photonics & Electromagnetics Research Symposium (PIERS). IEEE, 2024. 1–7.

- Hoseinnezhad, R.; Vo, B.N.; Vo, B.T. Visual tracking in background subtracted image sequences via multi-Bernoulli filtering. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2013, 61, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Sun, H.; Zheng, M.; Huang, W. Target Tracking with Random Finite Sets; Springer, 2023.

- Lee, C.S.; Clark, D.E.; Salvi, J. SLAM with dynamic targets via single-cluster PHD filtering. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 2013, 7, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Zeng, J.; Wang, Y.; Yan, S. Multi-target tracking in multi-static networks with autonomous underwater vehicles using a robust multi-sensor labeled multi-Bernoulli filter. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2023, 11, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xie, Z.; Dames, P. The semantic PHD filter for multi-class target tracking: From theory to practice. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2022, 149, 103947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, T. Particle PHD filter multiple target tracking in sonar image. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2007, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wei, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, X.; Lin, Y. Gaussian mixture probability hypothesis density filter for heterogeneous multi-sensor registration. Mathematics 2024, 12, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Zhang, B.; Qi, B. An augmented state Gaussian mixture probability hypothesis density filter for multitarget tracking of autonomous underwater vehicles. Ocean Engineering 2023, 287, 115727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.J.; Sparks, E.P.; Robertson, N.M. Contextual anomaly detection in crowded surveillance scenes. Pattern Recognition Letters 2014, 44, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, A.; Gostar, A.K.; Bab-Hadiashar, A.; Li, X.; Hoseinnezhad, R. Enhanced Multi-Target Tracking in Dynamic Environments: Distributed Control Methods Within the Random Finite Set Framework. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.14085. arXiv:2401.14085 2024.

- Meißner, D.A.; Reuter, S.; Strigel, E.; Dietmayer, K. Intersection-Based Road User Tracking Using a Classifying Multiple-Model PHD Filter. IEEE Intell. Transport. Syst. Mag. 2014, 6, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Shen, C.; Liu, H.; Huang, J.; Tian, K.; Tang, Z. Review of the field environmental sensing methods based on multi-sensor information fusion technology. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 2024, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruden, P.; White, P.R. Automated extraction of dolphin whistles—A sequential Monte Carlo probability hypothesis density approach. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2020, 148, 3014–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezatofighi, S.H.; Gould, S.; Vo, B.N.; Mele, K.; Hughes, W.E.; Hartley, R. A multiple model probability hypothesis density tracker for time-lapse cell microscopy sequences. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Processing in Medical Imaging. Springer. 2013; 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Haim, T.; Raviv, T.R. Graph neural network for cell tracking in microscopy videos. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer; 2022; pp. 610–626. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.Y. Multi-Bernoulli filtering for keypoint-based visual tracking. In Proceedings of the Control, Automation and Information Sciences (ICCAIS), 2016 International Conference on. IEEE. 2016; pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, L.; Ventura, J.; Langlotz, T.; Gul, S.; Mills, S.; Zollmann, S. Localization and tracking of stationary users for augmented reality. The Visual Computer 2024, 40, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, R.P. Advances in statistical multisource-multitarget information fusion; Artech House, 2014.

- Mahler, R.P. Multitarget Bayes filtering via first-order multitarget moments. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic systems 2003, 39, 1152–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, R. PHD filters of higher order in target number. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic systems 2007, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, B.N.; Vo, B.T.; Pham, N.T.; Suter, D. Joint detection and estimation of multiple objects from image observations. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2010, 58, 5129–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, B.N.; Vo, B.T.; Phung, D. Labeled random finite sets and the Bayes multi-target tracking filter. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2014, 62, 6554–6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, B.T.; Vo, B.N. Labeled random finite sets and multi-object conjugate priors. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2013, 61, 3460–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, D.; Yuan, J.; Chen, A.; Li, H.; Zhou, C.; Chen, W.; Liu, Q. GLMB Filter Based on Multiple Model Multiple Hypothesis Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2022 14th International Conference on Signal Processing Systems (ICSPS). IEEE. 2022; pp. 249–258. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdian-Dehkordi, M.; Azimifar, Z. Novel N-scan GM-PHD-based approach for multi-target tracking. IET Signal Processing 2016, 10, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, R.P. Statistical multisource-multitarget information fusion; Artech House, Inc., 2007.

- Vo, B.N.; Ma, W.K. The Gaussian mixture probability hypothesis density filter. IEEE Transactions on signal processing 2006, 54, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepanj, M.H.; Azimifar, Z. N-scan δ-generalized labeled multi-bernoulli-based approach for multi-target tracking. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Signal Processing Conference (AISP), 2017. IEEE. 2017; 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.L.; Stone, H.S.; Cox, I.J. Optimizing Murty’s ranked assignment method. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 1997, 33, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murty, K.G. Letter to the editor—An algorithm for ranking all the assignments in order of increasing cost. Operations research 1968, 16, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punchihewa, Y.G.; Vo, B.T.; Vo, B.N.; Kim, D.Y. Multiple Object Tracking in Unknown Backgrounds With Labeled Random Finite Sets. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2018, 66, 3040–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdian-Dehkordi, M.; Azimifar, Z. Refined GM-PHD tracker for tracking targets in possible subsequent missed detections. Signal Processing 2015, 116, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmacher, D.; Vo, B.T.; Vo, B.N. A consistent metric for performance evaluation of multi-object filters. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2008, 56, 3447–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Wang, P.; Zhao, P.; Zeng, H.; Chen, J. A novel multi-target TBD scheme for GNSS-based passive bistatic radar. IET Radar, Sonar & Navigation 2024, 18, 2497–2512. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, B.N.; Vo, B.T.; Hoang, H.G. An efficient implementation of the generalized labeled multi-Bernoulli filter. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2017, 65, 1975–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Gomez-Olmedo, R.; Lopez-Sastre, R.J.; Maldonado-Bascon, S.; Fernandez-Caballero, A. Vehicle Tracking by Simultaneous Detection and Viewpoint Estimation. In Proceedings of the IWINAC 2013, Part II, LNCS 7931, 2013, pp. 306–316.

- Bernardin, K.; Stiefelhagen, R. Evaluating multiple object tracking performance: the CLEAR MOT metrics. Journal on Image and Video Processing 2008, 2008, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, H.; Nuha, H.H.; Irsan, M.; Putrada, A.G.; Hisham, S.B.I. Object Tracking in Surveillance System Using Particle Filter and ACF Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA). IEEE. 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sepanj, H.; Fieguth, P. Context-Aware Augmentation for Contrastive Self-Supervised Representation Learning. Journal of Computational Vision and Imaging Systems 2023, 9, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sepanj, H.; Fieguth, P. Aligning Feature Distributions in VICReg Using Maximum Mean Discrepancy for Enhanced Manifold Awareness in Self-Supervised Representation Learning. Journal of Computational Vision and Imaging Systems 2024, 10, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sepanj, M.H.; Fiegth, P. SinSim: Sinkhorn-Regularized SimCLR. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.10478 2025.

- Sepanj, M.H.; Ghojogh, B.; Fieguth, P. Self-Supervised Learning Using Nonlinear Dependence. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.18875 2025.

| Method | OSPA(AVG) |

|---|---|

| GM-PHD | 39.03 |

| N-Scan GM-PHD | 34.51 |

| -GLMB | 32.28 |

| N-scan -GLMB | 28.67 |

| Enhanced N-scan -GLMB | 26.44 |

| Refined N-scan -GLMB | 24.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).